FALL 2011

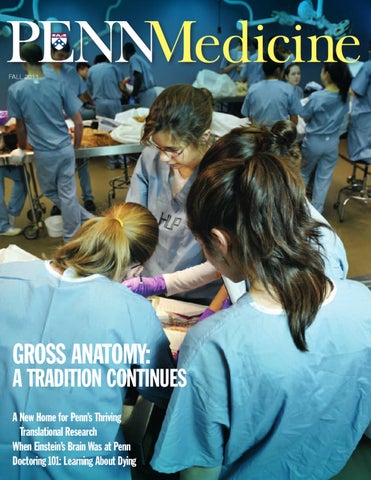

GROSS ANATOMY:

A TRADITION CONTINUES A New Home for Penn’s Thriving Translational Research When Einstein’s Brain Was at Penn Doctoring 101: Learning About Dying

FALL 2011

GROSS ANATOMY:

A TRADITION CONTINUES A New Home for Penn’s Thriving Translational Research When Einstein’s Brain Was at Penn Doctoring 101: Learning About Dying