Healthy School Environments, Healthy Hoosiers

A Whitepaper for Improving School Building Quality in Indiana

Version 1.0 2023

Acknowledgments

Authors:

Erika Eitland, Perkins&Will

Byron Ernest, Indiana Board of Education

Contributors:

Damon Hewlin, METICULOUS

Sara Ross, UndauntedK12

Bri Dazio, Perkins&Will

Rachael Dumas, Perkins&Will

Austin Drake, Perkins&Will

Melanie Jenkins, Columbia Mailman

School of Public Health

Sarosha Momin, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health

Nadia Itani, Columbia Mailman School of Public Health

Acknowledgments

NASBE serves as the only membership organization for state boards of education. A nonpartisan, nonprofit organization, NASBE elevates state board members’ voices in national and state policymaking, facilitates the exchange of informed ideas, and supports members in advancing equity and excellence in public education for students of all races, genders, and circumstances.

About the Authors

About the Human Experience (Hx) Lab at Perkins&Will

The impact of buildings and urban design on human health and performance has been documented through more than forty years of scientific research. The Hx Lab integrates this human experience research into the design process to improve environmental quality, respond to human health emergencies, and ensure occupants are functioning optimally. We explore design strategies for diverse spaces including clinical, academic, and workplace using bespoke surveys and tailored sensor applications. With collaborations and cutting-edge tools, we are demonstrating the value of human centered design. The role of our Hx Lab in this research project is to provide a public health lens to this research. The lab works to contextualize key shocks and stressors and provide a deeper understanding of the physiological, social, and environmental impacts on community members.

About Healthy School Facilities Network

The National Association of State Boards of Education (NASBE) created the Healthy School Facilities Network (HSFN) in 2022 to build and enhance the capacity of states to provide healthy school facilities. State boards of education were able to apply to receive a grant and tailored professional development to convene in-state stakeholder meetings, conduct research, and spur conversations around enhancing the state’s school facility improvement efforts. The Indiana State Board of Education received one of the HSFN grants and created an inter-agency team called the Healthy School Facilities Committee. The Committee was made up of individuals from multiple agencies including Indiana Finance Authority, Indiana Department of Environmental Management, Indiana Department of Health, Indiana Department of Education, State Board of Education, and two local superintendents. By leveraging this in-state expertise, the Committee established a goal to build state- and school-level leaders’ awareness of the science behind healthy school buildings and the impact of poor building quality on students’ learning outcomes. To accomplish this goal, the Committee hired Perkins&Will to produce a white paper summarizing the current health contexts of Indiana’s learners and educators and raise awareness of the impact of building design qualities that can improve students’ success.

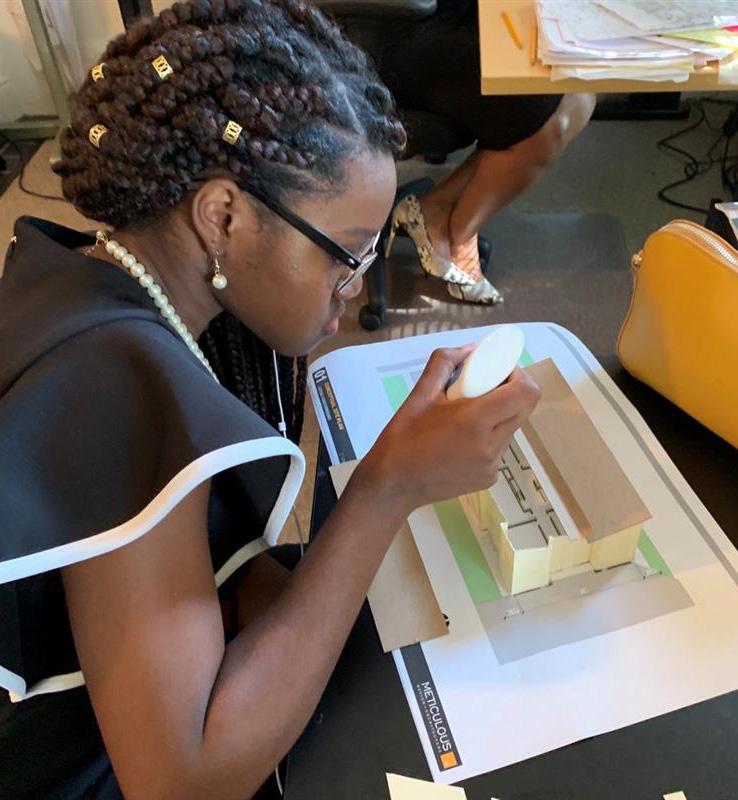

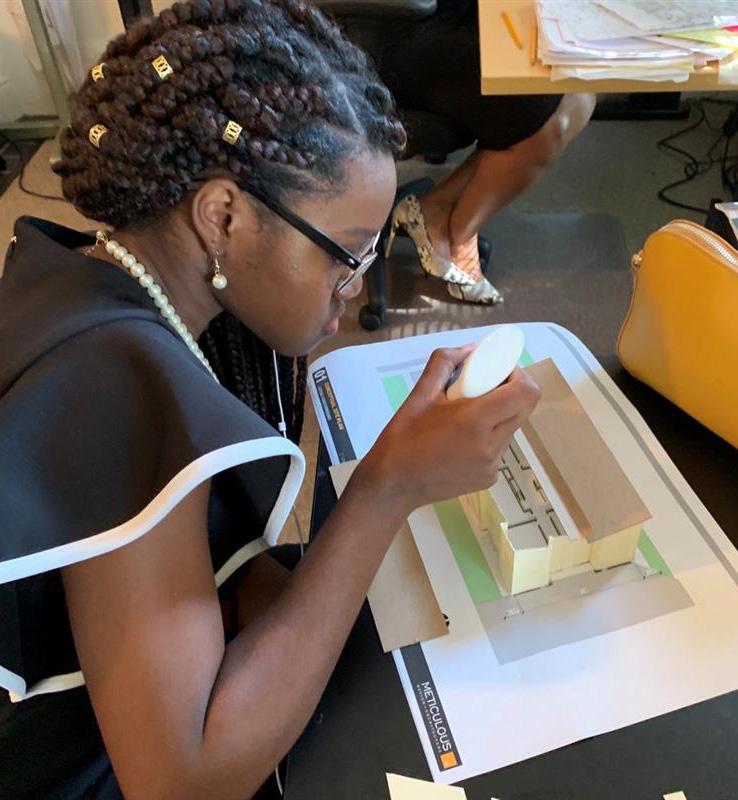

Photos courtesy of Meticulous Design + Architecture

The report consists of the following sections:

This is an interactive report. Throughout the report, titles that are bolded and underlined are linked to external resources.

Title Page 1 Authors & Context 2 Executive Summary 4 Who? Healthy School Environments for Healthy Students 8 Healthy School Environments for Healthy Educators 12 What? Holistically Healthy School Environments 16 How? An Economic Opportunity 20 Additional Resources 22 Conclusion 24 Overall Recommendations 25 References 26

Contents

1 Who? 2 What? 3 How?

Public Schools Students

1.2 million Public School Teachers

62,673 Public Schools

2,200 Students Chronically Absent

21% Students with Disability or Developmental Delay

15.5% Language or Speech Impairment

21% Breakfasts Served AY19-20

47 million Homeless Public School Children

18, 252

Executive Summary

K-12 schools stand as crucial pillars within our communities, serving as vital assets that not only educate and nourish our children but also serve as hubs for social interaction and employment, touching the lives of millions of Indiana residents daily. Astonishingly, Hoosier children spend approximately 15,000 hours of their formative years within the walls of K-12 schools, emphasizing the significant role these institutions play in shaping their physical and academic development. As key community anchors, educators deserve not only our gratitude but healthy workplace environments, recognizing its profound impact on performance, retention, healthcare costs, and absenteeism.

The condition and quality of educational facilities are paramount, and understanding the intersectionality of health and learning is crucial. A recent national report revealed that more than half of K-12 school districts require improving or updating one or more building system (United States Government Accountability Office, 2020). Currently, Indiana does not collect statewide data on building quality, age, or improvements, but qualitative accounts across the state highlight the need for critical upgrades to meet modern health and safety standards.

This is not new. In 2011, local Indianapolis news station 13 WTHR reported on indoor air quality concerns in Indiana schools, saying the state had an “invisible problem”. 66% of inspected schools had high levels of CO2, a sign of poor ventilation that contributes to poor student performance, cognitive function and asthma outcomes. 13 Investigates found that despite indoor air quality data, policies, and committees for K-12 schools, many districts were not able to adequately fix these conditions (Segall, 2016), and did not include the importance of investing in new heating, air conditioning or ventilation (HVAC) systems.

INDIANA PUBLIC SCHOOLS BY THE NUMBERS

Investing in K-12 school buildings is a once-ina-generation opportunity with far-reaching implications. Addressing these infrastructure gaps can improve indoor air, reduce background noise, ensure proper natural and electrical lighting, and reduce the cases of mold and moisture. Studies show a direct correlation between the physical condition of school buildings and student health outcomes, with inadequate maintenance and operations often linked to increased absenteeism and health-related issues (Eitland et al., 2017). Moreover, child health data highlights specific challenges faced by Hoosier students, ranging from respiratory issues due to mental health. A comprehensive approach to school building improvement must take into account these health considerations, ensuring that our educational spaces promote not only academic success but also the overall well-being of our youth. An investment in health-improving features of K-12 facilities has the potential to yield long-term economic advantages including reduced healthcare costs, enhanced educational outcomes, and a positive impact on quality of life for our communities.

This report aims to shed light on the unique health challenges facing Hoosier students and educators, the indispensable role that school buildings can play in fostering success, and potential recommendations for optimizing these educational facilities.

The authors hope this document serves as a catalyst to informed discussions and decision-making.

As we embark on this journey to enhance our commitment to healthy learning environments, let us collectively recognize that the quality of K-12 schools reverberates across our entire community, shaping the future workforce, healthcare professionals, educators, armed forces, and productive members of society.

GOALS OF THIS DOCUMENT

nj Inform K-12 stakeholders about healthy school facility features.

nj Provide evidence that healthy K-12 environments can support Indiana’s communities, children, and economy.

nj Identify strategies for K-12 schools to respond to Indiana’s pressing health challenges through school design and maintenance.

nj Support school facility decision-making that improves the quality of educational environments through adequate guidance and environmental measurement.

5

A “healthy school” promotes the physical and mental health of students and educators, while reducing harm, injury, and sickness. Healthy schools are thriving physical environments where all children can reach their full potential.

This document provides only one definition of a healthy school and can encompass many student and educator needs.

Health is foundational to student performance.

Childhood asthma is the leading cause of chronic absenteeism nationally and is exacerbated by poor indoor air quality, inadequate ventilation, and material selection (Hsu et al., 2016). Classroom conditions can prevent our students from learning and engaging. Even within the same school, varying conditions can impact certain spaces more than others.

Educational attainment is associated with economic gain. Students who finish high school make, on average, 25% more than students who do not finish high school by age 25 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). Faculty health is also an important determinant of student health. When educators experience greater well-being, their full potential is achieved, and capacities are greatly improved. Healthy schools can realize a range of benefits including better test performance, lower absenteeism, better graduation rates, and improved teacher retention.

Every community in Indiana deserves a healthy school. To achieve this ambitious goal will require increased awareness, local resources, and building upon statewide efforts and guidance.

“The physical, mental, and emotional health and wellbeing of children and adolescents is directly related to their academic success and their lifelong journey towards becoming healthy and productive adults. The School Health Team is dedicated to providing resources and technical assistance to schools, parents, and community partners in order to help Indiana students achieve optimal health.”

The following excerpt is taken from the Indiana Department of Health School Health Team:

7

Healthy School Environments for Healthy Students

Most buildings are designed based off standards for adult, ablebodied, office workers. However, schools are not little offices and children are not lit tle adults.

WHAT MAKES STUDENTS UNIQUE BUILDING OCCUPANTS?

CATEGORY RATIONALE

• Breathe 50% more air per pound of body weight

• Higher metabolic rates require more energy per unit of body weight

• More sensitive to daylight due to larger pupils

Physiology

• More consistent hormonal and body changes

• Have immature immune systems making them more susceptible to infections and pollutants

• Larger body surface area increasing their susceptibility to high temperatures

• Occupy unique places – the ground, indoor playgrounds, dense classrooms

• Spend more time outdoors

• Greater hand to mouth habits, which means they ingest more dust and chemicals found in our environment

Behavior

Exposure

• Developing personal hygiene

• Academically: learning language skills, reading, numeracy, literacy

• Socialization: developing social relationships

• Physically: lungs are still developing until the age of 18; generally double their height between ages 5 and 12.

• Cognitively: parts of the brain involved with sight and hearing will add millions of neurons between ages 5 and 6, only to shuck off a large percentage of their neurons as they approach age 12.

• Less able to communicate and/or control environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, window blinds)

• Limited by adult-child decision-making hierarchy

DAYS IN A SCHOOL YEAR YEARS OF EDUCATION (K-12) HOURS PER SCHOOL DAY 180 x 13 x ~6.5 = 15,210 HOURS

to indoor school environments by the time they graduate...

Growth Efficacy

9

Collaboration between architects, educators, healthcare professionals can embed a multi-pronged approach to addressing childhood obesity and asthma through school building design including:

•The cafeteria layout and design to support healthy food option choices and diverse seating arrangements for preferred levels of socialization (Frerichs et al., 2015).

•Well-maintained indoor and outdoor recreation facilities that support recess, sports, physical education, and after school programs (Fernandes & Sturm, 2010).

•Well-ventilated spaces with limited sources of indoor air pollutants that reduce the rates of asthma exacerbation and encourage active engagement and physical activity (Fisk, 2017).

•Using non-toxic, low-VOC paints, cleaners, and building materials can reduce asthma exacerbations. Using integrated pest management protocols reduce the need for harmful pesticides (U.S. EPA, 2023).

Health Considerations for Students

Investing in a healthy school environment may address long-term health challenges facing Hoosier students. Both childhood obesity and asthma can reduce physical activity, health, and academic performance.

Asthma & Respiratory Illness

As a state, Indiana ranks 46th for the “most polluted air” which makes respiratory illness in children a prominent health concern (United Health, 2023). Polluted air is one of many triggers for asthma. Luckily, investments in school mechanical ventilation systems with enhanced filtration can address sources of indoor and outdoor pollution and reduce the frequency and number of asthma attacks for Hoosier children and educators.

In 2019, there were over 25,000 recorded emergencydepartment visits related to asthma in Indiana, and 33.8% of these visits were for children (IDOH, 2023). The average annual cost of treating asthma per person is $3,266 (in 2015 USD) demonstrating that significant economic benefits could be realized by improving respiratory health among Hoosier students (Inserro, 2018). Additionally, the Indiana Department of Health estimated that 40.9% of current asthma cases were seen in Indiana residents who make less than $35,000, placing the greatest burden on low-income communities (IDOH, 2022). Improving air quality in K-12 schools can be an investment in community resilience and health.

In 2023, increasing the ventilation rate per student to healthy levels is less than the average cost of a movie theater ticket in Indiana (Fisk, 2017; Statista, 2023).

DESIGN INTERVENTIONS

Childhood Obesity

In 2018, among children ages 10-17, the prevalence of overweight or obese children is 30.1% (United Health, 2023). Furthermore, the annual per capita medical costs associated with overweight or obese children is $237.55 (Ling, et al., 2022). The chart below details the economic impact of reducing childhood obesity by 1%, 5%, and 10%. Even a mere 1% reduction in the number of obese or overweight children would generate over $500,000 in economic benefits--this is enough to fund salaries for 13 individuals in Indiana given an average hourly wage of $20.23 (IDWD, 2023). A 2022 estimate, suggests that there is a $9.3 billion reduction in the Indiana economy due to obesity and overweightrelated illnesses, unemployment, absenteeism, and healthcare costs (Global Data, 2023). During the COVID-19 pandemic, childhood obesity increased nationally, making early and holistic solutions increasingly important (Hauerslev et al, 2022).

Table 1 (below): Child population in 2021 provided by Annie E. Casey Foundation and the Indiana Youth Institute. United Health Foundation provided a prepandemic 2-year estimate of the percentage of children ages 10-17 who have overweight or obesity for their age based on reported height and weight. Data from National Survey of Children’s Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB), 20202021. Annual per Capita Cost is adopted from Ling et al., 2022 estimate for only annual total medical costs, and does not account for non-medical costs, suggesting this may underestimate the benefits of small reductions.

NUMBER OF CHILDREN AGES 10-17 IN INDIANA REDUCTION IN % OVERWEIGHT OR OBESE % OVERWEIGHT OR OBESE ANNUAL PER CAPITA COST OF BEING OVERWEIGHT OR OBESE TOTAL ANNUAL MEDICAL COSTS ECONOMIC BENEFIT REALIZED 796,753 0% 30.10% $237.55 $56,969,871.22 N/A 796,753 1% 29.80% $237.55 $56,400,172.51 $569,698.71 796,753 5% 28.60% $237.55 $51,415,308.78 $4,984,863.73 796,753 10% 27.09% $237.55 $46,145,595.69 $5,269,713.09 11

Healthy School Environments for Healthy Educators

According to the Indiana Education Employment Relations Board (IEERB) Collective Bargaining 2023 Statewide Summary Report, the total salary cost of all teachers was $3.68 billion with nearly $600 million spent on health insurance (Indiana Gateway, 2023).

By investing in their physical environment and workplaces, we can optimize educator performance, increase staff retention, reduce health-related absenteeis m and costs.

WHAT MAKES EDUCATORS UNIQUE BUILDING OCCUPANTS?

CATEGORY RATIONALE

• Increased incidence of somatic symptoms (such as headaches) and cardiovascular diseases

• Mental health may be affected by classroom conditions, as physical environment influences attitudes of educators

Health

Tenure

Ergonomics

Demographics

• IDOE job bank reports more than 1,500 teacher vacancies as of December 2022

• 78% of educators report feeling physically and emotionally exhausted at end of the day

• 10% of educators leave the profession after one year, and 17% leave after five years

• Thermal comfort and IAQ conditions linked to educator satisfaction

• More susceptible to work-related musculoskeletal pain due to repetitive movements and prolonged standing

• Frequent lifting for special education educators and staff, resulting in lower back, shoulder, and wrist pain

• Average age of an educator in Indiana is 42 years old

• 71.6% of Indiana school educators are female, corresponding with a majority of educators in Indiana at reproductive age (15-49 years old)

Average length of time spent in a school building by a Hoosier educator: Hours spent in a school building each year by Hoosier

HOURS EDUCATORS DAYS HOURS YEARS DAYS 7 x 180 x 13 = ~60,000 x 7 x 180 = 16,380 HOURS 75.6M HOURS

educators:

13

DESIGN INTERVENTIONS

Collaboration between architects, educators, healthcare professionals can embed a multi-pronged approach to addressing vocal strain, cancer, and mental health through school building design including:

•Limit sources of background noise (e.g. maintaining ventilation systems), add acoustic dampening materials to ceilings, and implement classroom augmentation systems to reduce vocal strain.

•Abate legacy pollutants (asbestos, polychlorinated bipheyls (PCBs)) that may have low levels but chronic exposures may lead to adverse health outcomes.

•Complete indoor air quality assessments to determine radon threat and indoor environmental monitoring to improve the indoor quality.

Health Considerations for Educators

Investing in a healthy school building may address long-term health challenges facing Hoosier educators. Vocal strain, mental health & wellbeing, and risk for cancer, and all impact teacher tenure.

Vocal Strain

In 2017-2018, 77% of public school teachers were female (NCES, 2023). Women have smaller larynxes, or voice boxes, and their vocal cords vibrate more quickly than their male counterparts (Long, 2016) increasing their risk to vocal strain. A 2014 study found that teachers are more than twice as likely to have a voice disorder than the general population (Martins, et al., 2014). The average direct cost of the most common voice disorders (chronic laryngitis, nonspecific causes of dysphonia, and benign vocal fold lesions) ranges between $577.18 and $953.21 per person (Cohen, et al., 2012). In a population of approximately 62,673 teachers, this means that the average annual cost of treating vocal strain is anywhere between $5,565,169.56 and $9,190,850.82.

Improving classroom acoustic conditions could save Indiana $5.5 – $9.1 million in educator vocal strain.

Mental Health & Wellbeing

The pandemic exacerbated mental health challenges, especially for educators. The American Federation of Teachers’ 2017 Educator Quality of Work Life Survey found that 58% of teachers attributed their poor mental health to stress (AFT, 2017). Teacher attrition due to chronic stress or other mental health conditions is problematic for faculty well-being. In fact, teacher retention in Indiana is currently hovering around 80% (Richard Fairbanks Foundation, 2023). On average, it costs a school district $25,000 for every teacher who leaves the district (Hillard, 2022). With low retention rates, these costs can quickly accumulate.

Cancer

Cancer is a highly prevalent chronic disease among Hoosier adults. In fact, every two in five people currently living in Indiana will develop cancer during their life (Indiana Cancer Facts, 2021). In Indiana, the burden of lung cancer is substantially higher than the US. For instance, the incidence rate of lung cancer in Indiana is 17.6% higher than the US average (Indiana Employment Outlook Projections, 2021). Even worse, the mortality rate attributable to lung cancer is 19.5% higher than the US average. After tobacco, exposure to radon, a naturally occurring radioactive gas, is the second leading cause of lung cancer in Indiana (Annie Casey Foundation, 2023). All residents, including Hoosier students and faculty, are moderately to severely at risk of radon exposure at any given time. Students with prolonged exposure to radon gas are at risk of long-term health outcomes (Saenz, 2019). When accurately detected, unhealthy levels of radon can be easily addressed with improved ventilation.8 Additionally, it is estimated that 1 in 10 Hoosier adults have asthma, so improving ventilation has both shortand long-term benefits for educators (IDOH, 2022).

ZONE 1 Highest potential

Average indoor radon levels may be greater than 4 pCi/L

ZONE 2 Moderate potential

Average indoor radon levels may be between 2 and 4 pCi/L

ZONE 3 Low potential

Average indoor radon levels may be less than 2 pCi/L

Figure 1 (right): Radon is measured in picocuries per liter. Throughout Indiana the radon potential exceeds 2pCi/L, the level the EPA recommends fixing residential environments, while the EPA action level for radon is 4 pCi/L. School-level interventions could reduce exposure for millions of Hoosiers.

15

Holistically Healthy School Environments

There is no one size fits all approach to implementing “healthy schools”. A healthy school must promote health and wellbeing without compromising students’ learning potential.

Perkins&Will released this holistic framework that highlighted Educational Adaptation, Health Promotion and Risk Mitigation.

Educational Adaptation

School building design and operations should support flexibility in behavior, logistics, and technology during shifting teaching needs. A 2020 report found that 68,649 to 80,118 Indiana school-age children lack internet access (Devaraj, et al., 2020). To increase broadband access, buildings may require improving or expanding electrical systems and existing WiFi networks to provide students with the necessary digital literacy skills to be better prepared for the modern workforce.

New building design or additions should consider classroom flexibility and adaptability. This creates a more inclusive future for different career technology offerings, engagement with individualized education programs or individuals with disabilities, as well as adjust for variable class sizes without incurring additional expenses or excessive demolition waste. Current projections demonstrate more than 27,000 job opportunities in the transportation and material moving occupation group in Indiana (Indiana Employment Outlook, 2023). As schools expand resources and classes on vocational training related to this industry, they need to create learning environments tailored to children’s unique physiological vulnerability. The individual facility may not need to take on this expense with partnerships with local businesses and industries providing students with real-world experiences and mentorship. Healthy schools support rigorous academic standards, employ effective teaching methods, and create opportunities for advanced learning. Compared to pre-pandemic levels, Indiana students’ math and reading scores have declined (Slaby., 2022). In fact, nearly all demographic groups had scores below proficiency benchmarks.

Health Promotion

For children and educators, their school building is the second most important building in their life. What happens outside of school can impact their performance and engagement including food insecurity, housing instability, chronic conditions, and other adverse childhood experiences. A healthy school must promote physical and mental health, social cohesion, and a sense of belonging and safety. The Indiana Healthy Schools Toolkit, 3rd edition from the Indiana Department of Health, Division of Nutrition & Physical Activity provides a robust guide to improved nutrition and physical education policies, but does not highlight how the physical school environment can support or deter student engagement (IDOH, 2022).

Other key health promotion opportunities includes supporting the estimated 30.7% of Hoosier students who have reported struggling with their mental health most of the time or always (Silverman, 2022). Building design features, such as the incorporation of nature and daylit views, can be a part of a holistic approach to improve student outcomes and reduce stress and fatigue (Kuo et al., 2019). Better maintained school facilities have been shown to have higher student satisfaction and reported self-worth because students feel valued and respected (Paulson, 2010).

Risk Mitigation

A healthy school must fundamentally reduce adverse environmental exposures that influence school occupant health and performance. The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Healthy Buildings Program published a white paper in 2017 entitled, Schools for Health: Foundations for Student Success (Eitland et al., 2017). With over 250 citations, the report makes a clear association between building quality and student health, thinking, and performance. The authors highlight the ideal circumstances for ventilation, indoor air quality, water quality, temperature, lighting, acoustics, dust, pests, mold, moisture and safety and security.

Health Promotion Educational Adaptation Risk Mitigation

17

Figure 2 (Left): The holistic approach with three buckets as defined by Perkins&Will.

Environmental Considerations

Healthy schools can have a positive impact on students. According to the EPA, high performance, healthy schools see many benefits, including:

• Higher test scores,

• Increased average daily attendance,

• Reduced operating costs, and

• Increased teacher satisfaction and retention. There are many environmental considerations that play a role in health and performance.

Indoor Air & Temperature

With childhood asthma and lung cancer among adults, improving indoor air quality is critical. Improved ventilation is associated with higher levels of attention, comprehension, student performance, teacher satisfaction as well as reductions in respiratory illness, headaches, and fatigue. Cold indoor temperatures have been shown to exacerbate poor blood pressure, asthma, and mental health conditions (WHO, 2018). Similarly, warm indoor temperatures have been linked to an increase in respiratory and cardiovascular related emergency department calls (Choi-Schagrin, 2022).

Acoustics

In Indianapolis Public Schools, there has been a 20% increase (6,000 children) in English as a new language program in the last 5 years (Beck, 2022). In 2022, IPS Bylaws and Policies proposed a policy aimed at language access and justice, stating language justice as the “practice of ensuring people can communicate effectively, understand information, and be understood using the language in which they feel most comfortable” (IPS, 2022). Poor classroom acoustics can cause issues in how a student “understands speech, reads and spells, behaves in the classroom, pays attention, and concentrates” (Classroom, 2023).

Lighting

Proper daylighting can ensure lower artificial light energy use and promote school occupant health. Research has shown that students in a classroom with more daylight had significantly better math and reading outcomes than students in classrooms without daylight (Heschong, 1999). Natural lighting strategies create a visually stimulating, well-lit, and productive environment (Lighting Design Awards, 2020). Children are more sensitive to daylight exposure than adults because they have larger pupils (University of Colorado, 2022). They also have significantly greater light-induced melatonin suppression (Akacem, et al., 2017). By introducing sunlight to classrooms, students and teachers can feel more energized and have greater psychological wellbeing.

Water Quality in Indiana Schools

Lead in drinking water is a major health concern for developing children, especially in school buildings built prior to 1991. Children are sensitive to negative health effects from lead because when ingested, the brain readily absorbs lead across the blood-brain barrier, which can impair neurodevelopment and cognitive function. This early exposure impacts mental and physical health outcomes over their lifetime (Jones et al., 2006).

Indiana requires testing and mitigation of lead in drinking water and offers financial assistance for mitigation (Pakenham & Olson, 2021). In 2019, the Indiana Finance Authority published a report which illustrated the water quality issue in Indiana schools. In fact, of 915 schools sampled, 62% had one or more fixture with lead levels above the “Action Level” specified by the U.S. EPA (Indiana Finance Authority, 2019). The report also highlighted that the average cost to replace the contaminated fixtures was a mere $550.12

To combat water quality challenges, schools should respond by testing water quality, rebuilding piping systems, and redirecting water sources, if needed, to avoid lead, dangerous bacteria and microbiomes, and other water-borne contaminants from faucets and drinking fountains. Extended school closures due to the outbreak of COVID-19 increased dangerous bacterial contaminants in vacant pipes, so water quality should be re-tested after such long periods of inactivity, including after summer breaks (Proctor et al., 2020). If replacing pipes is deemed necessary but challenging due to budget constraints, water bottle fillers can reduce exposure at the source and reduce the long term expense of providing bottled water to students and staff.

HEALTHY BUILDING DECISIONS TO ADDRESS:

•Windowless classrooms

•Asbestos

•Outdoor classrooms

•Air filtration or ventilation

•Walkability & Wayfinding

•School Siting

•Accessibility

•Furniture Selection

•Mitigating background noise

•Glare

•Temperature Control

•Daylighting

•Color Choice

•Technology

•Adjacency among spaces

•Flooring

•Landscaping

•Stain Repellent Fabric

•Biophilic Design

•Operable Windows

•Cleaning Products

19

ESSER III GRANT ACTIVITIES

Currently, ESSER III grant period goes until September 30, 2024 and allowable activities include:

• Improving indoor air quality, including if your HVAC system is failing or if you have documentation showing needed upgrades.

• Reducing viral transmission and other health hazards

• Addressing students who experienced learning loss

• Replacing asbestos flooring tiles

• Providing or improving mental health services on site

• Renovations or additions for after school programs

• Providing resources for students experiencing homelessness, children with disabilities, low-income children (e.g. additional showers, laundry facilities)

• Purchasing supplies for maintenance, cleaning, and sanitizing school facilities

Learn more about the ESSER II and ESSER III grants and your school district’s allocation at: in.gov/doe/grants/esser-ii-and-iii

An Economic Opportunity

Over the last three years, federal resources were made available for COVID-19 pandemic relief such as CARES Act, ESSER II and ESSER III funding through the Indiana Department of Education (IDOE, 2022).

Indiana received $2.8 Billion in ESSER funding, but as of September 2023 only 61.5% of the resources have been spent.

Across the United States, states and school districts received $189.5 billion (FutureEd, 2023). These funds are to improve four main categories:

1. Building Upgrades and Maintenance

2. Planning and Coordination Efforts

3. Student and Family Support Focused

4. School Staff and Leaders Support and Professional Development

The IDOE is prioritizing a formulaic distribution of the funds to the 353 school districts. Title I formulas dictate how much money the district receives. Once allocated, the district may support any schools, both Title I and non-Title I.

Given the sizable reimbursement options available, there are substantial cost savings to schools in capital and operating budgets. For example, in new school construction, ground-source heat pumps may now be the most affordable HVAC option to both install and operate through time. Pairing ground-source heat pumps with on-site solar ensures a low-cost, fixed cost source of electricity that can reduce budgetary uncertainty and provide substantial operating cost savings.

FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE VISIT UNDAUNTEDK12.ORG

The Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation (WIIN) Act

WIIN grants improve drinking water for schools and childcare facilities by voluntary testing for lead in drinking water, providing funding for infrastructure improvements such as lead service line replacement and filtration as well as technical assistance for communities dealing with water contaminants. The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law expanded the eligibility of WIIN funding to including testing AND remediating led in water. This expanded grant opportunity was announced over the summer and it was a big deal because states have been struggling to pay for remediating lead after it’s found.

Inflation Reduction Act

Signed into law in August 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) represents the largest federal investment in clean energy. Importantly, the IRA includes new provisions to provide non-taxable entities like schools with the ability to capture the value of clean energy tax credits through “Direct Pay”, or a cash reimbursement. All schools now have access to these noncompetitive, uncapped tax credits to defray the cost of installing clean energy machines that reduce operating costs and promote clean air. The following tax credits support clean energy machines put into service at schools starting on January 1, 2023:

For equipment put into service in calendar year 2023, schools must pre-file with the Internal Revenue Service in Fall 2023 and must complete Form 990-T by May 15, 2024. TAX CREDIT ELIGIBLE CLEAN ENERGY TECHNOLOGIES VALUE OF TAX CREDIT SUNSET Investment Tax Credit (Sec. 48) Solar Energy Storage Ground-source heat pumps Up to 70% of installed costs Up to 50% of installed costs Up to 50% of installed costs 12/31/2035 12/31/2035 1/1/2035 Commercial Clean Vehicle Credit (Sec. 45W) Electric school buses Up to $40,000 per vehicle Can be combined with the EPA’s Clean School Bus Program 12/31/2032 Alternative Fuel Refueling Property Credit (Sec. 30C) Electric vehicle charging equipment The lesser of 30% of project costs or $100,000 12/31/2032 21

Note:

Additional Resources

Our team compiled resources to provide an approach for creating healthier and more equitable school environments. When making selections, durability, cost, and availability are the main decision drivers. However, the immediate and long-term consequences of selection, require a more holistic decision-making

• Healthy School Environments

• Healthy Schools by Design by Perkins&Will: website offers compendium of strategies and resources that support safer, healthier, and more responsive learning ecosystems.

LEARN MORE AT HEALTHYK12.PERKINSWILL.COM

• Schools for Health: Foundations for Student Success by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health: report highlights school building influence on student’s health, thinking, and performance through findings from over 200 research studies and over 70 health outcomes.

LEARN MORE AT SCHOOLS.FORHEALTH.ORG

• Collaborative for High Performance Schools (CHPS): green building rating program designed specifically for K-12 schools. CHPS provides information and resources to schools, districts, and designers to create high performance schools.

LEARN MORE AT CHPS.NET

• Center for Green Schools by USGBC: organization advances green schools by providing resources to create sustainable, healthy, resilient, and equitable learning environments.

LEARN MORE AT CENTERFORGREENSCHOOLS.ORG

• Children’s Environmental Health Indicators by Children’s Environmental Health Network: report offers understanding of use and importance of health indicators as related to children’s environmental health. The report also highlights challenges and gaps that exist, as well as agencies leading the effort for change.

LEARN MORE AT CEHN.ORG

approach that accounts for costs associated with school occupant health and illness.

Note: Resources should not replace federal, state, or local guidance, but instead organize, understand, and implement steps for healthy school environments.

• Material Health

• Transparency Tool by Perkins&Will: database breaks down chemicals of concern by project type, product type, CSI specifications, and hazards. This offers a general overview of common products used in schools and how their chemistry can affect human health; the “nutrition facts” of design decisions.

LEARN MORE AT TRANSPARENCY.PERKINSWILL.COM

• Healthy Materials Lab Learning Hub by Parsons School of Design: website raises awareness about toxic chemicals in building products through resources for architects and designers.

LEARN MORE AT HEALTHYMATERIALSLAB.ORG

• HomeFree by Healthy Building Network: national initiative raises awareness of toxic building materials and associated health hazards. This website provides specific guidance on products (e.g., flooring, paint, insulation), case studies, educational materials, and other actional resources.

LEARN MORE AT HOMEFREE.HEALTHYBUILDING.NET

• Gensler Product Sustainability Standards by Gensler: standards focus on 12 high-impact product categories commonly used in architecture and interior projects. Standard serves as reference for both manufacturers and design teams.

LEARN MORE AT GENSLER.COM/

GENSLER-PRODUCT-SUSTAINABILITY-STANDARD

1 2 22

3

• Indoor Air Quality

• Indoor Air Quality Tools for Schools Action Kit by U.S. EPA: reference guide offers practical plan for schools to improve indoor air problems through best practices, industry guidelines, sample policies, and sample IAQ management plans.

LEARN MORE AT EPA.GOV/IAQ-SCHOOLS/ INDOOR-AIR-QUALITY-TOOLS-SCHOOLS-ACTION-KIT

• IAQ Fact Sheets by USGBC: resources offer easy way to understand indoor air quality in a school environment to make informed decisions.

LEARN MORE AT USGBC.ORG/RESOURCES/ SCHOOL-IAQ-FACT-SHEETS-ENTIRE-SERIES

Furniture should be part of the healthy materials conversation!

4

• Indiana-Specific Resources

• Indiana Department of Education: website includes resources for educators and school administrators, such as student learning resources, educator licensing information, school operations resources, and state as well as federal grants.

LEARN MORE AT IN.GOV/DOE

• Indiana Department of Health: Indoor Air Quality Program: best practices manuals to assist with schools meeting requirements for indoor air quality.

LEARN MORE AT IN.GOV/HEALTH/EPH/INDOOR-AIR-QUALITY

• Indiana School Health Network (ISHN): organization promotes, enhances, and advocates for comprehensive, coordinated school health programs and services.

LEARN MORE AT IN.GOV/DOE/STUDENTS/ SCHOOL-SAFETY-AND-WELLNESS/HEALTH

• Indiana State Teachers Association (ISTA): organization advocates locally and statewide to protect integrity and elevate the respect of educators.

LEARN MORE AT ISTA-IN.ORG

Poor posture in children is associated with discomfort (Breen, Pyper, Rusk, Dockrell, 2007) that may impact focus or attention. It has been shown that students with flexible seating options that allow them to wobble, rock, bounce, lean or stand can increase oxygen flow to the brain, while movement in the classroom has been associated with improvements of ontask behavior (Mahar, et al. 2006). However, flexible furniture may create challenges when completing individual tasks, social distancing, or finding replacement parts (Klein, 2020). A diversity of spaces and learning environments can create a welcoming, more inclusive space for all students while giving them selfefficacy to make decisions on where is best to learn for them.

This is an interactive report. Text that is bolded and underlined are linked to external resources. 23

Improving Indiana’s school buildings for health and performance will elevate Indiana’s 1.2 million students and 62,673 teachers. Prioritizing their health is both morally right and strategic, as it can lead to improved academic and professional performance, which is crucial for the state’s progress.

Conclusion

NEXT STEPS

Healthy students are more likely to excel academically, while healthy teachers can provide a higher quality of education. In addition to helping individuals, the state may also realize additional cost savings by reducing the financial load of medical expenses and freeing up funds for other initiatives. Given that educator salaries are state-funded, it is in Indiana’s best interest to prioritize the well-being of all faculty as a way to foster improvements in academic outcomes (which are correlated with economic benefits). Moreover, as schools serve as important community hubs, concentrating on health issues and diversity in the teaching staff can also promote a sense of community well-being. Communities can become healthier and happier by taking a more comprehensive approach to education that considers both the physical and cultural contexts.

This project comes at a perfect time due to the rapid changes in the educational landscape. The world is witnessing technological advances that are reshaping the way we teach and learn. Indiana can foster an atmosphere that supports these advances by making investments in the health and wellbeing of its students and staff. In turn, this can raise educational standards and potentially draw in a wider range of talent to Indiana’s institutions. As a result, putting a priority on health and diversity is not only morally and ethically right, but also a wise strategic choice that may help Indiana compete on a national scale. Now is the best time to act. An investment in a brighter future for the state, using the power of healthier, more diverse, and better-equipped educational institutions, will drive progress while positioning Indiana as a leader in the rapidly evolving educational landscape.

OVERALL RECOMMENDATIONS

There are many ways to improve school facilities to foster a healthier learning environment for students as well as the staff who ensure their safety, growth, and overall well-being. State, using the power of healthier, more diverse, and better-equipped educational institutions, will drive progress while positioning Indiana as a leader in the rapidly evolving educational landscape.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Through conversations with school stakeholders across Indiana, we have identified potential next steps to support healthy school buildings.

The state should hire an individual who can support school building design, maintenance, and operations. This individual can act as a liaison between the state and the school to ensure that any changes improve health outcomes. This individual should be accountable for tracking health and academic metrics as well as providing guidance to local school districts.

Measure existing school buildings to evaluate environmental conditions either quantitatively or qualitatively to understand the current physical and economic needs. Collect information on school facilities age, last renovation, age and type of HVAC, windows, roof, boilers. Health conditions measure air quality, acoustics, daylight.

Indiana should adopt a healthy school certification system such as Collaborative High Performance Schools (CHPS). This is a voluntary program in which schools use criteria outlined by CHPS to monitor and comply with metrics of high performing school facilities. Currently, Indiana does not use this designation system, but many other states have implemented it. The use of this system could help identify schools with the greatest need for facility improvements.

25

References

1. Beck, C. (2022) IPS board commits to providing more help to English language learners. Indianapolis Star. Published December 16, 2022. Accessed November 20, 2023. https://www.indystar.com/story/news/education/2022/12/16/indianapolis-schools-plan-to-offer-more-help-for-english-language-learners/69732880007/

2. Bellingrath S, Rohleder N, Kudielka BM. Healthy working school teachers with high effort-reward-imbalance and overcommitment show increased pro-inflammatory immune activity and a dampened innate immune defence. Brain Behav Immun. 2010 Nov;24(8):1332-9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2010.06.011. Epub 2010 Jul 3. PMID: 20599495.

3. Buchan DS, Donnelly S, McLellan G, Gibson AM, Arthur R. A feasibility study with process evaluation of a teacher led resource to improve measures of child health. PLoS One. 2019 Jul 2;14(7):e0218243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218243. PMID: 31265466; PMCID: PMC6605653.

4. Buckley, J, Schneider, M, Shang Y. The effects of school facility quality on teacher retention in urban school districts. NCES. 2004. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED539484.pdf

5. Cheng, HY.K., Wong, MT., Yu, YC. et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomic risk factors in special education teachers and teacher’s aides. BMC Public Health 16, 137 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2777-7

6. Choi-Schagrin W. New research shows how health risks to children mount as temperatures rise. New York Times. 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/19/climate/children-climate-change.html

7. CHPS certification. Collaborative High Performance Schools. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://chps.net/chps-designedschools.

8. Classroom acoustics. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://www.asha. org/public/hearing/Classroom-Acoustics/.

9. Cohen SM, Kim J, Roy N, Asche C, Courey M. Direct health care costs of laryngeal diseases and disorders. The Laryngoscope. 2012;122(7):1582-1588. doi:10.1002/lary.23189.

10. Daniel J. Madigan, Lisa E. Kim, Hanna L. Glandorf, Owen Kavanagh, Teacher burnout and physical health: A systematic review, International Journal of Educational Research, 2023; (119). doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102173.

11. Devaraj S, Faulk D, Hicks M, Zhang Y. How Many School-Age Children Lack Internet Access in Indiana? Ball State University; 2020. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://projects.cberdata.org/reports/Covid-InternetAccess-20201027.pdf

12. DOE. School health. Indiana Department of Education. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://www.in.gov/doe/students/ school-safety-and-wellness/health/.

13. Earthman, G.I. and Lemasters, L.K. (2009), “Teacher attitudes about classroom conditions”, Journal of Educational Administration, Vol. 47 No. 3, pp. 323-335. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230910955764

14. Education pays, 2022: Career Outlook. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2023. Accessed October 18, 2023. https:// www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2023/data-on-display/education-pays.htm#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20for%20example%2C%20workers,every%20level%20of%20education%20completed.

15. Eitland, E. Klingensmith, L., MacNaughton, P., Cedeno Laurent, J., Spengler, J., Bernstein, A., & Allen, J. (2017). Schools for Health. Foundations for Student Success. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. https://forhealth.org/Harvard. Schools_For_Health.Foundations_for_Student_Success.pdf

16. Fernandes, M., & Sturm, R. (2010). Facility provision in elementary schools: correlates with physical education, recess, and obesity. Preventive medicine, 50 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S30–S35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.022

17. Fisk WJ. (2017). The ventilation problem in schools: literature review. Indoor Air 2017;27:1039–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/ ina.12403

18. Frerichs, L., Brittin, J., Sorensen, D., Trowbridge, M. J., Yaroch, A. L., Siahpush, M., Tibbits, M., & Huang, T. T. (2015). Influence of school architecture and design on healthy eating: a review of the evidence. American journal of public health, 105(4), e46–e57.

https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302453

19. FutureEd. (2023). EXPLAINER: Progress in Spending Federal K-12 Covid Aid: State by State. https://www.future-ed.org/ progress-in-spending-federal-k-12-covid-aid-state-by-state/

26

20. Global Data. 2023. Obesity’s Impact on Indiana’s Economy and Labor Force. https://www.globaldata.com/health-economics/US/Indiana/Obesity-Impact-on-Indiana.pdf

21. Hauerslev, M., Narang, T., Gray, N., Samuels, T. A., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2022). Childhood obesity on the rise during COVID-19: A request for global leaders to change the trajectory. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 30(2), 288–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/ oby.23307

22. Heschong, Lisa. Daylighting in Schools: An Investigation into the Relationship Between Daylighting and Human Performance Condensed Report. 1999. 10.13140/RG.2.2.31498.31683.

23. Hillard, J. Losing our teachers: High turnover, shortages, burnout are a problem for our schools and children. NKyTribune. February 21, 2022. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://nkytribune.com/2022/02/losing-our-teachers-high-turnover-shortages-burnout-are-a-problem-for-our-schools-and-children/.

24. Hsu, J., Qin, X., Beavers, S. F., & Mirabelli, M. C. (2016). Asthma-Related School Absenteeism, Morbidity, and Modifiable Factors. American journal of preventive medicine, 51(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.12.012

25. IDOE. (2022) ESSER III: Frequently Asked Questions. Accessed November 17, 2023. https://www.in.gov/doe/files/ESSER-IIIFAQ-rev-12-9-2022.pdf.

26. Indiana Cancer Facts and Figures. 2021. Accessed October 12, 2023. https://indianacancer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ICC_FF_Intro_2021.pdf.

27. Indiana Department of Health. (2022). Asthma’s Impact in Indiana. https://www.in.gov/health/cdpc/files/2021_GeneralAsthma_FactSheet.pdf

28. Indiana Department of Health. (2022). Healthy Schools Toolkit. https://www.in.gov/health/dnpa/files/5.25.22-HealthySchools-Toolkit.pdf

29. Indiana Department of Health. (2022). Indoor Air Quality in Schools Best Practices Manual. Division of Environmental Health. https://www.in.gov/health/eph/files/Indoor-Air-Quality-in-Schools-Best-Practices-Manual.pdf

30. Indiana Department of Health. (May 2022). Asthma’s impact in Indiana. Accessed October 4, 2023. https://www.in.gov/ health/cdpc/files/2021_GeneralAsthma_FactSheet.pdf.

31. Indiana Department of Workforce Development. (n.d.). Job postings and openings by County. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://datavizpublic.in.gov/views/JobPostingsandOpeningsbyCounty/Page1?%3Aembed=y&%3AshowAppBanner=false&%3AshowShareOptions=true&%3Adisplay_count=no&%3AshowVizHome=no.

32. Indiana Employment Outlook Projections. Employment Outlook Projections: Hoosiers by The Numbers. Accessed October 16, 2023. https://www.hoosierdata.in.gov/FD/landing.aspx.

33. Indiana Finance Authority. Indiana Lead Sampling Programs for Public Schools. January 2019. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.in.gov/ifa/files/Indiana-School-Lead-Sampling-Program_FinalReport_IFA2019.pdf.

34. Indiana Gateway. 2023. IEERB Statewide Report - 2023 Statewide. Accessed November, 7, 2023. https://gateway.ifionline. org/report_builder/Default3a.aspx?rpttype=collBargain&rpt=ieerb_statewide_comparison&rptName=IEERB%20Collective%20Bargaining%20Statewide%20Summary

35. Indianapolis Public Schools (IPS). (2022). LANGUAGE ACCESS/LANGUAGE JUSTICE. BYLAWS AND POLICIES, Section: 2000 PROGRAM. Last Revised. December 12, 2022. https://go.boarddocs.com/in/indps/Board.nsf/files/CM4LS45758A5/$file/ Proposed%20BP%202173%20Language%20Justice%20%5Bclean%5D%20-%20December%202022.pdf

36. Inserro, A. CDC study puts economic burden of asthma at more than $80 billion per year. AJMC. January 12, 2018. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.ajmc.com/view/cdc-study-puts-economic-burden-of-asthma-at-more-than-80-billionper-year.

37. ISTA. Solving Indiana’s educator shortage crisis. ISTA. 2023. https://www.ista-in.org/uploads/2023-ISTA-Legislative-Priorities.pdf

38. Jones, S. E., Axelrad, R., & Wattigney, W. A. Healthy and Safe School Environment, part II, Physical School Environment: Results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. Journal of School Health, 2007;77(8), 544–556. https:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00234.

39. Kraemer K, Moreira MF, Guimarães B. Musculoskeletal pain and ergonomic risks in teachers of a federal institution. Rev Bras Med Trab. 2021 Feb 11;18(3):343-351. doi: 10.47626/1679-4435-2020-608. PMID: 33597985; PMCID: PMC7879465.

27

40. Kuo M, Barnes M, Jordan C. Do Experiences With Nature Promote Learning? Converging Evidence of a Cause-and-Effect Relationship. Front Psychol. 2019 Feb 19;10:305. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00305. PMID: 30873068; PMCID: PMC6401598.

41. Lever N, Mathis E, Mayworm A. School Mental Health Is Not Just for Students: Why Teacher and School Staff Wellness Matters. Rep Emot Behav Disord Youth. 2017 Winter;17(1):6-12. PMID: 30705611; PMCID: PMC6350815.

42. Lighting Design Awards. The benefits of natural light in Interior Design & Architecture. Lighting Design Awards. [Online] September 7, 2020. https://litawards.com/the-benefits-of-natural-light-in-interior-design.

43. Ling, J., Chen, S., Zahry, N. R., & Kao, T. A. Economic burden of childhood overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity reviews: an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 2023; 24(2), e13535. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.13535.

44. Long, C. 2016. Teacher Voice Problems Are an Occupational Hazard. Here’s How to Reduce the Risk. National Education Association. neaToday. https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/teacher-voice-problems-are-occupational-hazard-heres-how-reduce-risk#:~:text=Women%20have%20smaller%20larynxes%2C%20or,thinner%20than%20 male%20vocal%20chords.

45. Martins RH, Pereira ER, Hidalgo CB, Tavares EL. Voice disorders in teachers. A Review. Journal of Voice. 2014;28(6):716-724. doi:10.1016/j.jvoice.2014.02.008.

46. NCES. National teacher and principal survey. National Center for Education Statistics. 2018. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ ntps/tables/ntps1718_fltable02_t1s.asp

47. Pakenham, C. & Olson, B. (2021). How States Are Handling Lead in School Drinking Water. National Association of State Board of Education. Education Leaders Report. November 2021, Volume 7, no.1. https://nasbe.nyc3.digitaloceanspaces. com/2021/12/Pakenham-et-al_School-Lead-Testing-Report.pdf

48. Paulson J, Barnett C. Who’s in charge of children’s environmental health at school? New Solut. 2010;20(1):3-23. doi: 10.2190/ NS.20.1.b. PMID: 20359989.

49. Proctor, C. R., Rhoads, W. J., Keane, T., Salehi, M., Hamilton, K., Pieper, K. J., Cwiertny, D. M., Prévost, M., & Whelton, A. J. (2020). Considerations for large building water quality after extended stagnation. AWWA Water Science, 2(4). https://doi. org/10.1002/aws2.1186

50. Richard M. Fairbanks Foundation. Indianapolis Education Data Snapshot. Richard M. Fairbanks Foundation. September 21, 2023. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.rmff.org/community-data-snapshot/education/

51. Saenz E. Report: Indiana has sixth-highest rate of lung cancer among U.S. states. Indiana Environmental Reporter. December 2, 2019. Accessed October 11, 2023. https://www.indianaenvironmentalreporter.org/posts/report-finds-indiana-hassixth-highest-rate-of-lung-cancer-in-the-nation#:~:text=RADON%20RISK&text=An%20estimated%2020%2C000%20 deaths%20nationally,greater%20than%204.0%20pCi%2FL.

52. Segall, B. (2011). Fixing School Air. 13 WTHR. Updated April 14, 2016. Accessed November 17, 2023. https://www.wthr.com/ article/news/local/fixing-school-air/531-beef232d-107f-4a75-91a1-2876f5ec10d7

53. Silverman T. Uniting to Promote Youth Suicide Prevention. Indiana Youth Institute. September 22, 2022. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.iyi.org/mental-health/

54. Slaby M. Indiana’s NAEP scores show biggest decline in math as leaders Weigh Covid’s fallout. The Indianapolis Star. October 25, 2022. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.indystar.com/story/news/education/2022/10/25/indiana-naepscores-show-biggest-decline-in-math-compared-pre-covid-results/69587808007/.

55. Statista. 2023. Average ticket price at movie theaters in the United States from 2001 to 2021. Accessed November 7, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/187091/average-ticket-price-at-north-american-movie-theaters-since-2001/#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20the%20average%20price,from%208.65%20dollars%20in%202016.

56. Steiner, Elizabeth D., Sy Doan, Ashley Woo, Allyson D. Gittens, Rebecca Ann Lawrence, Lisa Berdie, Rebecca L. Wolfe, Lucas Greer, and Heather L. Schwartz, Restoring Teacher and Principal Well-Being Is an Essential Step for Rebuilding Schools: Findings from the State of the American Teacher and State of the American Principal Surveys. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-4.html.

57. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2023, April). Child population by age group. KIDS COUNT Data Center. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/4281-child-population-by-age-group#detailed/2/any/fal se/2048,574,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868/8211,4743,4744,4745,140/10958,11403.

28

58. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Teacher and Principal Survey (NTPS), “Public School Teacher Data File,” 2017–18. Accessed November 7, 2023. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/ntps/tables/ ntps1718_21011201_t1n.asp

59. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2023. Reference Guide for Indoor Air Quality in Schools. https://www.epa.gov/iaqschools/reference-guide-indoor-air-quality-schools

60. United Health Foundation. (n.d.). Explore overweight or obesity - youth in Indiana: AHR. America’s Health Rankings. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/youth_overweight/IN?edition-year=2018.

61. United Health Foundation. (n.d.-a). Explore air pollution in Indiana: AHR. America’s Health Rankings. Accessed October 6, 2023. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/air/IN.

62. University of Colorado at Boulder. Even dim light before bedtime may disrupt a preschooler’s sleep. Science Daily. [Online] January 27, 2022. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2022/01/220127104208.htm.

63. Voice disorders. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Accessed October 7, 2023. https://www.asha.org/ practice-portal/clinical-topics/voice-disorders/#collapse_1.

64. World Health Organization. Low indoor temperatures and insulation - WHO housing and health. NIH National Library of Medicine. 2018. Accessed October 15, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535294/.

65. 2017 Educator Quality of Work Life Survey - AFT. 2017. Accessed October 18, 2023. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/ media/2017/2017_eqwl_survey_web.pdf.\

29

Published 2023 (Version 1.0)

Reach out if you want to support healthy school environments for healthy Hoosiers:

HEALTHYK12HOOSIERS@GMAIL.COM