14 minute read

THE ART OF CONVERSATION

b e h a v i o r The Art of Conversation

Kathie Gregory examines the importance of listening to what our animals are telling us through their body language and vocalizations, as well as understanding when they are emotionally conflicted, ensuring that they too have a voice

Advertisement

© Can Stock Photo / Antonio_Diaz Our emotional state can change the pitch of our voice and animals also pick up on this Human emotions influence body language even when we try to hide how we feel, and this is usually very obvious to our animals

Following my recent series on the body language of horses, dogs and cats (see Resources), I hope you now have an even greater awareness of what your animal’s side of the conversation is. Everyone has a voice, but sometimes we don’t hear it until it gets louder and the person or animal starts shouting, so to speak.

The art of communication is not just about putting across your side of the conversation, but also about how you are perceived by the other party and whether you are really listening to them. If you are not, then you are going to continue with your side without understanding the animal’s perspective, or what he is actually saying/trying to say. This leads to an unequal conversation, where both of you can feel misunderstood and frustrated.

We’ve looked in depth at body language and vocalizations of horses and dogs, so now let’s take a look at ourselves.

Mixed Messages

What you say (or think you say) is not necessarily the same message that your horse, dog or other animal receives. Teaching animals to do something specific when they hear a particular word is how most people teach. So, in that respect yes, what you say is what the animal receives. But there is more to it. Your emotions influence your body

© Can Stock Photo / Dusan

language and tone of voice, so even if communication is limited to isolated words, those words can still be perceived in different ways. However, we are going to look further than simple conditioned responses to a particular word, and talk about our conversations when we have taught language to a higher level.

We will assume that the animal we are having a conversation with knows the names of things, or cues, and the use of those words in different phrases. So why is what you think you are saying not necessarily what you are actually saying? Well, there are a few reasons. The most obvious one is that unless you have taught your animal to understand the words and phrases in different contexts, he is not going understand what you mean. It is not always easy to apply something you already know to a completely different situation. This is the first piece of miscommunication. We assume that the animal has the ability to interpret our conversation in a different context. And animals are perfectly able to do this, but there are a couple of things that get in the way.

For example, if an animal has had a limited education and has not had the freedom to think for himself, he will find this difficult to do. When an animal’s education has been based on doing exactly what he is told to do, being involved in a conversation where he has to interpret and apply phrases in different ways is going to be very difficult and

What you say (or think you say) is not necessarily the same message that your horse, dog or other animal receives...Your emotions influence your body language and tone of voice, so even if communication is limited to isolated words, those words can still be perceived in different ways.

stressful. When we move over to a way of interacting that allows for the animal’s freedom of expression, it’s easy to forget that he may not know how to express himself. He can be wrongly labelled as not very clever when all he needs is teaching.

We know that young animals need to be taught, but may sometimes forget with an older animal. Some animals find the concept of choice easy to understand. Some find it more difficult. Some find making choices stressful and they will become anxious. This may be due their background and previous experiences, but not necessarily. Some just find choice worrying. Identifying this as a reason for your animal not understanding you means you really have to listen and understand that he is telling you he is unable to make a choice, or he doesn’t know what to do to apply the phrases he knows in a different context.

We also tend to talk casually when we are having a conversation. We are not usually as clear as we would be when we are instructing someone. I’m sure many of us have said something, received a reply, and thought, no that’s not what I meant! While you know what you mean when you say something, the words you choose and the way you say things may be interpreted in a different way by your animal. This means he may receive information differently to that which you intended, leading you to believe he is not listening to you or paying attention. But going back over what you said and how you said it then looking at how that may have been interpreted can help you understand why your animal did something other than what you expected.

Body Language and Habits

We also need to look at our body language and whether that supports what we are saying verbally. Again, this can be a case of not being clear, even though we think we are. We will often make gestures and certain facial expressions when we talk and unless we are concentrating on what we are doing, we may not even be aware of how our body is moving. Our body will move in a natural way for each of us, which also includes our habits and the preferred movements we all make. We don’t always notice them but others will say, yes, you do this when you are engaged, or that when you are not sure.

The thing is, our body language is not always in tune with what we are saying. For example, I have a habit of folding my arms across my chest, usually when I am in a higher emotional state than usual, so I may do this when something has happened and I’m not sure what to do. I have also realized I do this when I am happy to see someone. Now, on the surface it looks like I am closed and maybe not interested, or not wanting to engage with the person, but this is not true. It’s a default position. And we all have them.

My dog Remy also has one. He likes to stand between my legs when he is happy (and when really happy will keep walking through and around!), but he will also stand there on the odd occasion he is worried. I have not taught him this and it is not a trick we have trained. Remy has done this ever since he was a young puppy, and it turns out that his dad does it too. These are examples of how we all have posture habits, and preferred movements, regardless of if we are a person, horse, cat, or dog, and that they do not necessarily mean anything. But the person or animal on the receiving end may pick up on the fact that while we are saying one thing, our posture and movements don’t seem to match with that.

© Can Stock Photo / PavelShlykov One of the best things we can do for our animals is to master the art of conversation If we listen to our animal’s side of the conversation, we can see when body language and actions don’t add up, helping us identify when emotions are conflicted

Emotions and Feelings

Another reason we do not necessarily say what we think we are saying is our emotional state at the time. When looking at the nuances of body language and vocalization (see Contradictions and Subtleties, BARKS from the Guild, September 2021, pp.50‐53), there is conflict more often than not. And this is because there are usually several emotions and feelings in play at the same time. We see the expression of these emotions in different parts of communication, and in different intensities, which shows us that there is more going on than one simple response to a conversation.

Sometimes we have one strong emotion that hides others and things are straightforward, but this is not often the case. We can be excited but nervous at the same time. We may be anxious and look hesitant, but actually really do want to do something. We may feel anticipation of something good along with nervousness of it. We may feel anticipation of something we don’t want to do, but also feel sure we are going to do it. As you can imagine, these emotions are going to result in a few different signals being given that can cause confusion over what is actually meant. Animals are really good at reading signals and not just focusing on the words that are spoken, which is something we, as people, tend to do, so you can see how even though we think we are being clear, we might be some way from that.

© Can Stock Photo / remains

Another aspect of how our emotions influence our body language is when we are trying to hide how we feel. This is usually very obvious to our animals. How many times have we been slow, quiet, and encouraging because we want to shut a barn door or field gate when we need our horse to be in a certain place, perhaps for the vet? The moment we start, he knows something is up. We are not behaving naturally, and he can see it. From our perspective, we think we are being reassuring and this will help him stay where he is so we can get the door or gate closed before he decides to leave. We are also probably feeling anxious too, as we do need him to be in the right place. But from his perspective, we are behaving differently and this is not reassuring. Or, if we have done this before, he knows what we are trying to do and if he does not want to be shut in will leave the moment he sees us coming. If only we had walked into his area with our usual relaxed body language as if nothing was going on, we would be in a better position to get the job done. This situation also will have a knockon effect on the horse, as if we are not behaving normally, then maybe there is something to worry about.

Another situation where we try to hide our feelings is when we are angry or frustrated. We may try to carry on but there is no way we can hide those emotions and so, once again, our animal knows something is not right. This affects his actions and whether he is able to listen to our side of the conversation.

Looking for Something?

Currently holds over 4,050 articles, studies, podcasts, blogs and videos and is growing daily!

The

petprofessionalguild.com/Guild-Archives

CATEGORIES INCLUDE:

s canine s feline s equine s avian s animal behavior s piscine s pocket pets s training s business advice s trends s PPG news s book reviews s member profiles s opinion

We have the same issues with our tone of voice. Our emotional state can change the voice’s pitch and animals also pick up on this. So even if we are being careful with our body language to be calm and move in a relaxed manner, we can be tripped up by the fact that our voice does not match our movements. This makes animals wary and they are not likely to be listening to our words. Rather, they are assessing us as a whole and making the most sensible decision for themselves based on their interpretation.

Finally, we come to the other half of the conversation. Remember, it is not all about us; it is equally about our animals. We are actually at a disadvantage compared to our animal, by dint of the fact that we are trying to achieve something. This means our mind is on the goal and because of this we often stop listening. As humans, we also take more notice of the spoken word. We are not always very observant or aware of the rest of what someone is communicating, so unless our animal is vocal, we often don’t look for other signs of his side of the conversation. But everything we have discussed so far about ourselves and how we come across is the same for our animals. If we really listen to their side of the conversation, we can see when body language and actions don’t add up, and when tone of voice says one thing but the movement says another. We can see the conflict of emotions, and when a familiar movement or posture means one thing in one context and something else in another.

One of the best things we can do for our animals is to master the art of conversation. In doing so, we become aware of all of our side of the conversation, and listen to our animal so we are aware of all of his side of the conversation. This gives him a voice, a real voice that he knows we will listen to, take notice of and adjust for, so we are truly in partnership with each other. n

Resources

Gregory, K. (2021, September). Contradictions and Subtleties. BARKS from the Guild (50) 50-53 Gregory, K. (2021, July). Found in Translation. BARKS from the Guild (49) 46-49 Gregory, K. (2021, March). Understanding Animals. BARKS from the Guild (47) 50-51 Gregory, K. (2021, May). The Complete Picture. BARKS from the Guild (48) 48-51

Kathie Gregory is a qualified animal behavior consultant and author, specializing in advanced cognition and emotional intelligence. Passionate about raising standards and awareness in how we teach and work with animals, she has launched The Academy of Free Will Teaching, providing educational courses for professionals and those interested in learning more about dogs and horses. She has authored two books, A Tale of Two Horses: A Passion for Free Will Teaching, and A Puppy Called Wolfie: A Passion for Free Will Teaching.

S is for...

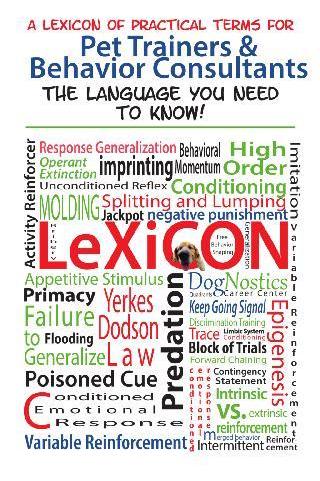

The A-Z of Training and Behavior Brought to you by

Salience: How noticeable or obvious a stimulus is. Discriminative Stimuli (cues) and Bridging Stimuli (behavior markers) need to be salient, standing out from other environmental stimuli. For example, a clicker is usually more salient than a verbal marker such as the word “yes.”

Satiation: When repeated presentations of a reinforcer weaken the response then satiation has occurred. Ex: This can occur when a biological need has been met.

Secondary Reinforcer: Conditioned reinforcers, referred to as secondary reinforcers, are dependent on an association with other reinforcers. They owe their effectiveness directly or indirectly to primary reinforcers. Secondary, conditioned reinforcers tend to be weaker than primary, unconditioned reinforcers but they are more durable, more easily available and less disruptive than primary reinforcements. They are susceptible to extinction though if you don’t follow them with unconditioned reinforcers.

Secondary Reinforcer: Conditioned reinforcers, referred to as secondary reinforcers, are dependent on an association with other reinforcers. They owe their effectiveness directly or indirectly to primary reinforcers. Secondary, conditioned reinforcers tend to be weaker than primary, unconditioned reinforcers but they are more durable, more easily available and less disruptive than primary reinforcements. They are susceptible to extinction though if you don’t follow them with unconditioned reinforcers. Setting Event: Setting events are general conditions that set the occasion for the behavior. Examples of setting events are medical problems, nutritional issues or lack of exercise. Setting events make the behavior in question more likely to occur. Setting events do not directly evoke the behavior but they provide a context in which the behavior is more likely to be evoked by the Stimulus. Stimulus: Anything a being can perceive that incites action. From: A Lexicon of Practical Terms for Pet Trainers & Behavior Consultants: The language you need to know! by DogNostics Career Center. Available from: dognosticseducation.com/p/store