Pictured on this page: Lauren Floris, former Pepperdine XC and Track runner and current XC and Track head coach, Christian Hosea, Men’s Water Polo fifth year attacker and the 2024 Women’s Indoor Volleyball team

Pictured on front cover: Brandon Llewellyn, , Terry Schroeder, Emerita Mashaire, Jonathan Winder, 2023 Women’s Soccer team, 2022 Women’s Swim and Dive team, Emma Martinez, Kayla Renner, Tyler Davis, Michael Beard, Grace Chillingworth, Trinity Stanger and Scott Wong

06

14

‘Setting the Standard’: The Mountain’s Athletic Arena to Improve Athletics, Campus

On the Clock: Speeding Up America’s Favorite Pastime

New Transfer Portal Rules Shift College Sports Landscape

10

Transforming the Game: The Impact of NIL on Athletics

17 22 25 30

Family Matters: Swim and Dive Wins as a Family

Mind Over Match: Women’s Indoor Volleyball Focuses on Mental Health

‘The Genesis of Greatness’: MLB Awards the Negro Leagues Major League Status

As a religious follower of baseball, there was one man who I never wanted to see making headlines — MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred. My issue with Manfred was how it seemed like every year, he wanted to change something about the game I loved.

Since becoming commissioner in 2015, Manfred has implemented a handful of rule changes, added a lottery system to the draft, expanded from 10 to 12 playoff teams and changed the Wild Card game to a threegame Wild Card series, according to Baseball Almanac.

During the first few years of Manfred’s tenure, I was annoyed with

star players wear different uniforms throughout their career, teams move locations, new rules are implemented and dynasties rise and fall.

On the collegiate level, there's been changes such as the creation of the transfer portal in 2018, athletes being able to earn money off their Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) and many schools realigning to different conferences, according to the NCAA.

Even Pepperdine Athletics is entering a new era with a new athletics director, new head coaches for both Basketball teams and Baseball and the construction of a new sports arena, as a part of The Mountain at Mullin Park.

It is this new and emerging era of Pepperdine Athletics that inspired this special edition of the Graphic, as we highlight some of the recent developments in Pepperdine, professional and collegiate sports.

Change can be scary, but it’s necessary, so rather than trying to prevent it — we should embrace it. Without at least attempting to do things differently, our favorite sports will never evolve.

the constant rule changes, as all I wanted to do was “keep baseball the way it is.”

The truth is, though, baseball and the MLB underwent many changes throughout their long history to get to the point it was at when I first started following the sport. The brand of baseball I would watch on a nightly basis was different from what previous generations had watched.

And 30 years from now, the baseball I’m watching will be different from what I’m watching now.

On the professional level,

After all, if everyone had the mindset of “keeping baseball the way it is,” then there would only be 16 teams in the MLB and there wouldn’t be a World Series, just as it was in 1901.

Without at least attempting change, we run the risk of letting the sports and leagues we’re passionate about grow stagnant. As you flip through this magazine and read the stories, my hope is you’ll understand the sports landscape is ever changing and it is a privilege to be able to know the history of sports, appreciate them in the moment and be a part of their evolution.

Sincerely and Go Red Sox,

written by Tony Gleason

photos courtesy of Pepperdine University

Firestone Fieldhouse has been the home arena for the Waves since it opened Nov. 30, 1972, with a Men’s Basketball game against UNLV. Though, after over 50 years, its time as the only arena is coming to an end, as the new arena is under development.

The Mountain at Mullin Park will contain a new athletic arena that members of Pepperdine Athletics said will not only allow athletes to maximize their potential, but will serve the Pepperdine community as a whole.

“My vision for The Mountain is a place where people come together, to enjoy community, to celebrate, to cheer on the Waves, to win a lot of games,” Athletics Director Tanner Gardner said. “And to do it together, in a way that elevates the brand of Pepperdine Athletics, elevates the brand of Pepperdine University and glorifies God.”

Since there is only one court on Pepperdine’s campus, both Men’s and Women’s Basketball, Men’s and Women’s Volleyball and recreational teams all have to share Firestone. This creates the biggest challenge, as the four teams often have to make extra sacrifices to find the time to practice, multiple coaches said.

During the summer, Men’s Basketball Head Coach Ed Schilling said the team often had to go off campus to practice.

“We went to Malibu High School,”

Schilling said. “We’ve gone to the LA Sports Academy. We’ve had to go other places just to get on the court, to do the time that we're allowed by the NCAA, not even to mention the extra time to improve.”

For Men’s Volleyball, Head Coach Jonathan Winder said the team has to hold their practices at 6:30 a.m., but if players want to get extra work in, then they have to arrive even earlier in the morning.

“The standard doesn't change in terms of what we're trying to achieve and the goals that we have — both volleyball and basketball or any other sport.” Winder said. “Everybody wants to win, and you just have to deal with the hand that you have.”

The NCAA allows teams who are in season to practice for 20 hours a week, a maximum of four hours per day. Teams out of season are allowed eight hours a week, with a maximum of two hours per day, according to the NCAA.

Only practice that is directed or supervised by members of the coaching staff count toward those hours, so student-athletes are able to practice on their own merit as much as they wish. Thus, sharing one gym between four teams further prohibits athletes from training on their own time, multiple sources said.

“We have to really focus on developing to make them [student-athletes] better,” Gardner said. “And, certainly for Ed, that's a calling card on what he's best at, and that's also a big part of Katie’s approach and so if you only have a couple hours of gym time a day, it’s really hard to develop your players.”

Along with development of talent, multiple sources said having one gym also creates challenges with recruitment of talent.

Men’s Basketball brought in 11 new players this year — three freshmen and eight transfers, according to Pepperdine Athletics. Schilling said his team brought in these 11 players with 14 total visits, but most of their success in recruiting had come from relationships and not because they were able to sell their facilities.

“To be completely honest, we’re among the worst in our conference, and so we’re going to go from among the worst to the best,” Schilling said.

Furthermore, Gardner said other schools would use Pepperdine’s lack of multiple courts and difficulties finding the time and space to practice to their advantage when recruiting.

“Schools used to negatively recruit against us,” Gardner said. “‘You don't want to go to Pepperdine. They only have one gym. You won't even have time to practice. You can't get baskets up outside of practice.’ They can't do that anymore.”

Gardner said it remains unknown what will come of Firestone once The Mountain is built, but many of the offices will remain in Firestone for the time being.

The Mountain is one of many recent changes Pepperdine Athletics has undergone within the past six months. Gardner was appointed as the new AD in March and began his tenure in June. Schilling and Women’s Basketball Head Coach Katie Faulkner began their Pepperdine coaching careers in April, and Baseball Head Coach Tyler LaTorre joined the Waves on June 14, according to previous Graphic reporting.

On the facilities side, Stotsenberg Track was upgraded and Firestone is

under construction to add a locker room and a practice area for Men’s and Women’s Golf, according to previous Graphic reporting.

“The Mountain, in and of itself, is transformational,” Gardner said. “It’s a piece of a bigger story about how we're really working to transform Pepperdine Athletics from what's already a really good program into a program that’s great and sustains that greatness.”

Among the WCC’s full time members, the most recent arena to be built is Gonzaga’s McCarthey Athletic Arena, which opened Nov. 19, 2004, according to Gonzaga Athletics. Including affiliate members, once Grand Canyon joins the WCC in the 2025-26 fiscal year, their arena — Global Credit Union Arena — will be the newest, as it opened Sept. 1, 2011, according to GCU Athletics.

The Mountain will include new locker rooms for the four teams using the court, a center-hung video board and a multi-activity court that will be used as a practice facility and recreational space, according to Pepperdine’s webpage on The Mountain. Additionally, it will include upgraded seating and views, LED boards, two suite spaces and a club space, Gardner said.

“You think about, a historic facility, a Firestone Fieldhouse that is just not that big, moving to what will be a state of the art facility, this difference cannot be more stark,” Gardner said. “Pepperdine sets the standard in many areas, and we will be setting the standard arenas once The Mountain opens.”

Construction of The Mountain began in January and is expected to be complete by late 2026, according to Pepperdine’s website. Gardner, Schilling and Faulkner all said the development of The Mountain played a large role in their decision to come to Pepperdine.

“It represents the support behind athletics here,” Faulkner said. “And so from the top down, Pepperdine University values athletics and values Women's Basketball and wants it to succeed.”

While much of The Mountain has already been designed, Gardner said

he has consulted with the four head coaches who will be using the arena on the design of certain interior spaces such as the locker rooms or other technical parts of the court. This is done to make sure the construction and facilities workers aren’t missing anything only a coach would notice.

“Ed pointed out that if you put the baskets 6 feet from the wall, then you can't have shooting at all six baskets,” Gardner said. “But if you put the baskets 2 feet from the wall, you can shoot free throws and three pointers at all six baskets.”

Another area The Mountain is looking to address is the retention of talent. Within the past few years, college athletics has seen an increase in the number of athletes using the transfer portal, as the number of Division I athletes who transferred rose from 9,806 transfers in 2021 to 13,025 in 2023, according to Western Front Online. Additionally, a recent rule change now allows athletes to transfer multiple times without having to sit out for a season, according to the NCAA.

Men’s and Women’s Basketball, in particular, have a high amount of transfers every year, as in 2022, 1,649 Men’s players and 1,276 Women’s players entered the portal, according to the NCAA. Pepperdine’s basketball programs have experienced these increased transfer rates, as eight members of the 2023-24 Women’s team came to Pepperdine via the portal and 11 Men’s players transferred out at the end of the 2023-24 season, according to Pepperdine Athletics.

“I don't want to have to use the portal, because I want our kids to stay,” Faulkner said. “That's why NIL is so important. That's why support and The Mountain and donors and community involvement is so important, because we do want our athletes to stay here, because Pepperdine is such an amazing place for them to grow and succeed.”

In terms of making money, Gardner said Pepperdine will be able to rent out the facilities in a way they can’t do with Firestone, and people have already been asking when the

facility will be complete.

“From a naming perspective, we’ll have an ability to host a lot of really neat events there, which, at many colleges, are great sources of revenue,” Gardner said. “Hosting concerts, hosting speakers, hosting conferences, these are all great sources of revenue and great sources of publicity for Pepperdine.”

Beyond providing better opportunities for student-athletes, multiple sources said The Mountain will enhance Pepperdine for every member of the student body. The Mountain is being built where the Rho Parking Lot used to be, so it will be surrounded by Seaside, Lovernich, Towers and three first-year dorms — thus a location that will help draw in crowds.

“It’s going to provide a place for our campus community to gather,” Gardner said. “It was very intentionally placed around residential housing so students can walk out of some of the dorms and be right there.”

In addition to the athletic arena, The Mountain will also include a new RISE building meant for student recreation, a parking garage with over

800 spots and a park known as the Mullin Green, according to Clark Construction.

The arena is estimated to be able to hold 3,600 students, which is still lower than most arenas within the conference, but the combination of its location and amenities for students is why multiple sources said they expect the crowds within The Mountain to be roaring.

“I can’t understate the impact a great crowd can have and, I would say, particularly the impact of students,” Gardner said. “I always said at Rice that every student was worth three non-student fans. Students bring the energy. Students Supporting their fellow students is super meaningful. When you're playing in a quiet arena without much energy, it's hard to gain energy.”

Before coaching here, Winder was a student-athlete at Pepperdine from 2005 to 2008, where he won a National Championship in 2005 and National Player of the Year in 2007, according to Pepperdine Athletics.

When Winder was still a student-athlete at Pepperdine, he said many areas where students often hang out now, such as the Starbucks attached to Payson, had yet to be

built, so he views The Mountain as another addition to Pepperdine to bring the community closer.

“People talk about the view and the quality of people that go here, and so that just continues to get fostered the more you spend time with your classmates, you’re face-to-face with them,” Winder said. “And it’s really important for Pepperdine to create spaces that allow students to do that and then to also create experiences here on campus.”

Going beyond the student body, Schilling said Pepperdine has a reputation to uphold, and to meet that reputation, every part of its campus has to live up to that expectation.

“[Pepperdine] is synonymous with excellence, and what The Mountain does, it says, ‘OK, hey, even their athletics, that’s excellent, too,’” Schilling said. “And we don't want to say, ‘Hey, we’re excellent in one area, but, boy, we’re way behind the times in athletics, in the basketball facility.’ Now, we can say, ‘Hey, we’re excellent academically, our campus is obviously excellent and guess what, our basketball facilities are excellent, too.

Journalism major from Danvers, Mass. His favorite sport is baseball, and he cheers for the Boston Red Sox. Gleason’s favorite professional athlete is Red Sox first baseman Triston Casas.

Gleason said his favorite sports memory is Andrew Benintendi’s game-saving catch in game 4 of the 2018 American League Championship Series. He said sports created an easy way for him to start conversations with people.

written by Justin Rodriguez photos by Colton Rubsamen & Millie Auchard

You only have 20 seconds. What could you do in those 20 seconds? Watch a TikTok? Send a text? Perhaps, tie your shoes? Some people can solve a Rubix Cube in this timeframe. But, what is most surprising is how collegiate and professional pitchers have 20 seconds, or less, to perform at their highest caliber, over and over and over again – and some pitchers do this every five days.

In 2022, Major League Baseball announced to its fans three rule changes for the 2023 season. Within these three rules lays the pitch clock, which requires pitchers to start their wind up before it expires, batters to be ready to hit at eight seconds and limits pick off attempts in order to quicken pace of play, according to the MLB.

“The benefit of it has not really saved the game, but helped save the game from people losing interest in it,” said Ned

Colletti, professor of Sport Admin-

istration and former general manager for the Los Angeles Dodgers (‘05-‘14).

“I don’t think it was the time of the game that people started to look at, it was the pace of the game. Especially in this era as life goes on, things get faster, life gets faster.”

New Era, New Changes: The Pitch Clock Overview

When initially introduced to the NCAA in 2011, a 20-second countdown applied only when no runners were on base, alongside a 90-second timer between innings. Batters were required to be ready to hit with five seconds remaining, or else, “no pitch will result and either a ball or strike is called depending on the violation and any ensuing play is nullified,” according to the NCAA.

Enforcement was inconsistent until the 2020 season, when the NCAA increased the between-innings clock to 120 seconds and directed umpires to enforce stricter adherence to the rules. By 2023, the pitch clock rules expanded to include runners on base and disengagements — how many times the pitcher can step off the rubber. Now, pitchers must step off, pick off or pitch in time to avoid penalties, with immediate consequences for infractions. Additionally, the NCAA introduced a visible on-field timer for Division I games starting Jan. 1, 2023.

To Colletti, he said Generation Z played dividends in the collegiate and professional levels’ interest in quickening the pace of the game, claiming both as the catalyst and key components to the updates.

“There’s so many different things to do, there’s so many different ways to spend your time,” Colletti said. “So, it was a bright move to kind of quicken the pace, and by doing that, you

also shorten the game.”

That pace sped up by a wide margin. Upon the first year of its implementation, the pitch clock chopped 24 minutes from total game time during the 2023 MLB season. The average game time during this season was two hours and 40 minutes, one of the lowest averages since 1985 with this being the first time the game has dipped below the three hour mark since 2015, according to NBC New York.

Collin Valentine, sophomore Pepperdine Baseball left-handed pitcher, said as a high school athlete coming into a Division I college, the hardest transition wasn’t the clock, but the skill ceiling of the other players.

“Going from high school to the Division I level, every hitter from top to bottom is much better than the average high school hitter, so you really have to be focused at all times,” Valentine said. “There were some times in high school where maybe you could loosen up a little bit and just sort of get the guy out without really having to lock in.”

One area that was impactful for his transition in both Division I play and the pitch clock was staying mentally focused. As a college pitcher, Valentine said he stresses the importance of having that strong mental approach and focus, however, too much time to focus can be a

double-edge sword.

“You can’t really take too much time between pitches and really think about it, so maybe that’s a good thing,” Valentine said. “You just have to sort of clear your mind and go.”

Valentine said he attended the University of Texas at Austin last year, but did not get innings on the field, so coming into Pepperdine for the 2024 season was his first taste at the clock. For him, the clock is something that doesn’t cross his mind often, but instead something he enjoys. He typically works pretty fast on the mound, and enjoys the clock because it does speed up the game.

As a way to adjust, Valentine said the coaching staff puts emphasis on pitch clock drills and practices to get everyone ready for the clock, but more specifically, for new incoming players who aren’t familiar with it.

This quickness only affected Valentine’s play minimally, with only areas like shaking off pitches being truly impacted by the clock. Valentine said sometimes, he would look over to his coach to shake off, but if his coach wasn’t looking back, the clock would force his hand.

“There are a few times where I would look to coach and shake, but he was maybe looking at the scouting report or something, and we weren’t able to communicate that,” Valentine said. “Due to the pitch clock and not having enough time, I would have to go with what he called and just sort of go with it.”

On the other hand, Valentine said the clock hasn’t affected him as much as other players because of his body type. Some pitchers are bulkier, heavier and overall bigger, and for them the transition can be much harder.

“It can also be a little more taxing on the body, just because some of those bigger guys — guys that weigh a little more — they like to use more time to recover in between pitches,” Valentine said. “With the pitch clock, they don’t have as much time anymore.”

Shane Telfer, former baseball left-handed pitcher (‘20-‘23) and current Arizona Diamondbacks minor league pitcher, said he echoes Valentine’s sentiments around the clock, all stemming from his already faster pace on the mound.

Telfer was at Pepperdine during the early life cycles of the clock, specifically the second version of rule updates that occurred prior to the ‘20 season. He said because of this, the clock wasn’t something viewed as entirely important and was an area coaches tended to disregard. Going from college to the minors, he can only recall situational moments being affected by the clock, like bases loaded and no outs, when he really wanted to take a breath but it’s a race against the clock.

“There are times I look up and see the clock winding down and I realize I can’t catch a breath,” Telfer said. “You just gotta get ready and throw.”

For both of these pitchers, the pitch clock hasn’t altered their pregame routines and warmup practices. Telfer said what really helped him transition was recalling a classic statement as old as the game: Practice like it’s the game.

“If I could give any advice, it would be to practice like it’s the real deal,” Telfer said. “Get used to the clock early, so when it’s time to buckle down, you’ll get the adjustment out of the way early.”

Both Telfer and Valentine said the

pitch clock has been almost an afterthought. They viewed the clock as mutually beneficial due to its nature of speeding up the game, and also said that communication between the catcher and coaches has been more fluid.

One area that is still gray are pitcher injuries, something Telfer, Valentine and Colletti said was already on the rise dating back before the clock. Colletti speculated that the timing was just a bit off considering the direction the game was headed.

Between 1974 and 1994, only 12 MLB players had to undergo Tommy John surgery — a surgery to repair a torn UCL in the elbow — but the next 5 years, from 1995 to 1999, that number jumped up to 22. Unfortunately for most pitchers, it would be a name they heard often throughout their careers as from 2000 to 2011, there were 194 surgeries performed at the MLB level, and another 275 in the MiLB, according to Samford University.

“Something else that has kind of gone in parallel to this is the push to have pitchers throw as hard as they can,” Colletti said. “Certainly you’re drawn to velocity, but I was always drawn to those who could pitch, and I was around a lot of great pitchers, a lot of Hall of Fame guys that by the end of their careers were throwing in the mid 80s. Today, they wouldn’t have a chance, but they knew how to pitch.”

This push for velocity has been something slowly encouraged within the sport over the last decade or so, as owners and GMs have pushed to not only draft pitchers who can reach the triple digit mark, but also spend the capital to trade for these prospects or major-league-ready arms each and every year, as detailed by the Washington Post.

Since the Statcast era (2015), the number of 100 mph pitches or faster thrown has grown almost every year, according to Baseball Savant. In ‘15, this count finished at 1389 pitches, and at the conclusion of the ‘23 season, this count ended at 3880 pitches.

However, Colletti said if you’re an

athlete competing, especially at the highest level, you always have to be able to adjust.

“You’re in a constant state of adjustment — the best ones [adjust] pitch to pitch, good ones at bat to at bat,” Colletti said. “But you always have to adjust whether it’s a rule, or whether it’s just a competition inside the game.”

If he could make any changes to the clock, Colletti said he’d add a few seconds to playoff games.

“I might add a little time in the month of October, a little bit, not a lot,” Colletti said. “I think when you get to October, people are a little bit less concerned with pace than they are with outcome.”

College baseball incorporated the clock for the fans, Major League Baseball incorporated the clock for the fans and the fans seemed to enjoy the change.

Gaming Today surveyed over 1,000 MLB fans across the United States during the 2023 season, the inaugural season of the clock, and one major thing was certain: fans of the game loved the faster-paced games – three out of every five fans, to be exact.

It is unclear what baseball has in store for its athletes and fans moving forward, but one thing that is clear is the clock is here to stay.

Justin Rodriguez is a senior Journalism major from Fontana, Calif. His favorite sport is baseball, and he is a fan of the Los Angeles Dodgers. His favorite professional athletes is Clayton Kershaw and Corey Seager.

Rodriguez’s favorite sports memory is attending game 2 of the 2017 World Series and said sports helped him create a strong relationship with his dad and created lasting memories, lessons and friendships.

written by Emma Martinez

Changing the rules of a sport ultimately changes the results of the game, match or race. Changing the rules of the NCAA Transfer Portal ultimately changes collegiate athletics.

On April 18, the NCAA Division I Council unanimously adopted a new package of rules, forever changing

the way student-athletes transfer from one school to another, according to the NCAA. The rule changes include a shortened time period to enter the portal, no limit to the amount of times an athlete can transfer and the ability to compete immediately after transferring, according to ESPN.

The rule changes come with pros and cons, but Amanda Kurtz, Pepperdine’s senior associate director of Athletics for Internal Operations, said she believes it has come with more good than bad for Pepperdine Athletics.

“Everyone has their own reasons for transferring,” Kurtz said. “The majority are for very valid reasons, and they should have every opportunity to do so.”

With every rule change to the transfer portal process, there was a reason behind it, Kurtz said. The window of time that is available for athletes to join the portal used to be up to 60 days, now it is in the 30 to 45 day range.

“The number of students entering the portal, kind of after 30 days, drops off dramatically,” Kurtz said.

Kurtz said this will not

take opportunities away from any athletes — it is just streamlining the process and helping coaches with their recruiting.

“Now coaches know who’s coming and going and how many roster spots they need to fill,” Kurtz said. “The coaches were really vocal about meeting those shortened windows.”

Men’s and Women’s Basketball are the two NCAA sports with the highest transfer rates, according to NBC Sports. In 2021, 31% of Men’s Basketball players transferred, while 22% of Women’s Basketball players transferred.

Before the rule change in the spring, all basketball players had to sit out an athletic season if they transferred, but there was a waiver process that allowed players to compete immediately and transfer more than once if approved, Kurtz said.

Waivers were accepted if there was an assertion of exigent circumstances or student-athlete injury, illness or mental illness, according to CCHA Collegiate Sport Law.

“There were so many waivers they [Division I Committee] were approving,” Kurtz said. “Then they would approve these waivers so they could play right away, so there were ways around it.”

Emerita Mashaire, Pepperdine Women’s Basketball senior guard, said she experienced the waiver process firsthand.

“I also had to request a waiver from the NCAA since it was my second time transferring,” Mashaire said.

“I didn’t find out if I was going to be allowed to play until our exhibition game.”

Mashaire said she felt the pressure while filling out the waiver to transfer to Pepperdine, because if it were not approved, she would have had to sit out a year of athletics.

“It was a pretty stressful process,” Mashaire said. “I wanted to find the right fit and have a good experience for my last two years, and I knew this was the last chance I had.”

While many individuals focus on the possible negative effects of the rule changes, Kurtz said the new rules relieve the stress of the waiver process for athletes who are transferring for valid reasons.

“I transferred due to mental health reasons,” Mashaire said. “I had individually a good season in my previous school, but the overall environment had a negative impact on me.”

Across all sports, Pepperdine brought in a large amount of student-athlete transfers, with 35 total and a couple of those being multiple time transfers, Kurtz wrote in a Sept. 9 email to the Graphic following her interview.

Pepperdine’s 2024-25 Men’s Basketball team is the prime example of a positive use of the transfer portal, said Ed Schilling, Pepperdine Men’s Basketball head coach. Following the end of the 2023-24 season and Lorenzo Romar, former Pepperdine Men’s Basketball head coach, leaving the university, Men’s Basketball saw an influx of players transferring, according to previous Graphic reporting.

“I got the job in April, and the cupboard was completely bare,” Schilling said. “We had to bring in basically 11 guys. We have two back from last year.”

Some of the transfers adding to the Waves’ experienced roster include Graduate forward Alonso Faure, redshirt Junior guard Zion Bethea and Junior guard Moe Odum. Half of the 2024-2025 roster has at least two

seasons of collegiate experience in the books, according to Pepperdine Athletics.

Shilling said the change of rules, allowing players to transfer without sitting out a season, has allowed him to recruit experienced players, which was nearly impossible in the past.

“Back in the day when there was no transfer portal, you’re trying to do

it all with freshmen or junior college [players],” Schilling said. “You don’t want to have a whole team of young kids.”

The streamlined transfer portal process and the unlimited number of players allowed Pepperdine to bring in quality upperclassmen players, Schilling said. One of those veteran players is Stefan Todorovic, Pepper-

Todorovic said he benefited from the new process because this is the third university he has played for, the first two being University of San Francisco and Southern Methodist University.

“Both of my transfers were because I was looking for better basketball opportunities,” Todorovic said.

With the recent rule changes, Todorovic is able to play this season with no punishment. He said this made the process an easy one.

“The transfer portal was pretty easy for me,” Todorovic said. “I already had clear ideas where I wanted to play.”

While there are great success stories from the rule changes, there have been drawbacks at Pepperdine, Kurtz said.

When athletes transfer to Pepperdine, they are allowed to bring 64 units, even if they completed far

more at their previous institution, Kurtz said. Students need 128 units to graduate, according to Pepperdine’s Seaver College website.

“It’s extremely challenging for sixth semester transfers to do and be eligible right away,” Kurtz said. “So we have a harder time getting kids that transfer multiple times.”

This University-wide rule has deterred recruits for the Men’s Basketball team, Schilling said.

“In several cases, we could have had a very high level player, but we couldn’t get them,” Schilling said.

While student-transfers have had to adjust their academic and athletic game-plan due to the new transfer portal process, coaches have also had to draw out new strategies, Schilling said. With it being easier than ever to transfer, there is a lot of pressure on NCAA coaching staff.

“It’s one of those things that makes it harder, to take a kid coming out of high school, because if he doesn’t play, and is not happy, he can leave before he pays his dues,” Schilling said. “Also, if a kid plays really, really well, then they can get up and go to someone that’s going to pay them a whole bunch of NIL money.”

Keeping players on the same team and building a culture where players want to stay is now difficult but possible if done properly, Schilling said.

“I think you have to have a system that players feel like they’re getting better,” Schilling said. “If they aren’t improving, they can just get up and leave.”

Schilling said just because a player enters the portal, does not mean another coach will pick them up. Of the 13% of Division I athletes who entered the portal in 2022, only 7% made the successful switch, according to the NCAA.

“The success stories are highlighted,” Schilling said. “But the tragic stories of guys that were on scholarship and getting to play, are finding themselves on the outside looking in.”

Schilling said the end result of the transfer portal does not always end up as well as it does for players like

Mashaire and Todorovic.

“There’s thousands of kids right now that went in the transfer portal thinking the grass was going to be greener,” Schilling said. “And now they find themselves without a scholarship.”

There are benefits and disadvantages to many rules throughout collegiate athletics, but Kurtz said the new set of rules provides those with high academic and athletic aspirations to accomplish their goals in a streamline and uniformed process.

“I think sometimes [high school] students maybe didn’t make the best decision for the school that works for them,” Kurtz said. “People grow and change or there’s a head coaching change, and it’s like, ‘That new coach is not my style, and we’re not going to work well together,’ so you need to go somewhere else.”

Emma Martinez is a sophomore Journalism major from Palmerton, Penn. Her favorite sport is Track & Field. Martinez said her favorite professional team is the Portland Thorns FC. Her favorite professional athlete is American middle-distance runner Hobbs Kessler.

Martinez said her favorite sports memory is when she watched Cole Hocker win the 1500m gold medal at the 2024 Olympics with her family. She said sports have helped her create lasting memories with her family and friends.

written by Shalom Montgomery

Nico Iamaleava introduced the world to the growing scene of NIL (Name, Image, Likeness) when he committed to the University of Tennessee, Knoxville in 2022. The Volunteers offered Iamaleava $8 million through Spyre Sports Group, a Tennessee collective. This made him one of the first athletes to sign one of the largest NIL deals in the early stages of the NIL era, according to The Sporting News.

NIL is the right for college athletes to be compensated for their personhood and talent when they are used for commercial purposes. Prior to the passing of the new NIL policy in July 2021, college athletes were strictly prohibited from profiting from themselves. All monetary compensations were directed to the NCAA, leaving players with virtually nothing.

“It's a different world,” said Alicia Jessop, associate professor of Sport Administration. “Why can't this group of people — when everyone else in America can benefit from this right, why not them?"

Athletes couldn’t sign sponsorship deals with companies like Nike, Adidas or local businesses. Athletes with large social media followings couldn’t monetize their accounts through advertisements or sponsored posts. If athletes had businesses, they couldn’t promote or profit from them using their status. Athletes weren’t allowed to accept

gifts, discounts or free items related to their status, even something as small as a free meal.

The Interim NIL Policy, passed July 1, 2021, allows collegiate athletes to legally earn money from anything attached to their name and talent. This completely shifted the collegiate landscape and led to the question of whether or not collegiate athletes should be considered as employees.

Addi Melone, Pepperdine Women’s Basketball senior point guard, is one of the most lucrative Pepperdine athletes regarding NIL deals. Melone said she has earned around $5,000 to $7,000 since beginning her NIL journey.

Melone started her athletic career at Lane Community College and then Eastern Arizona College. She joined the Waves for the 2023-24 season as a junior with two years of eligibility remaining and entered the NIL realm knowing very little about the logistics and branding, Melone said.

The disparity of knowledge and available resources about such a nuanced topic such as NIL is very wide between DI and Junior Colleges (JUCO), Melone said.

“We didn't have many resources [at JUCO], whether that be NIL or just basic school resources,” Melone said. “So once I achieved my goal of being DI, I really wanted to build myself up and I knew this space of NIL was available.”

Women’s basketball players are becoming some of the most lucrative NIL earners across collegiate sports.

The 2023 NCAA Women’s Basketball Tournament broke viewership records, with over 9 million viewers, leading to more opportunities for female athletes to gain recognition and secure endorsement deals, according to AP News.

“It’s great to see just women starting to be successful,” Melone said. “There’s tons of charts that you could compare NIL to how much people make and it’s really crazy to look at because some girls are making more than the men are because they are more advertisable.”

Track & Field is currently experiencing an increase in both viewership and NIL deals, according to NBC Sports. With buzz from the 2024 Summer Olympics, which saw a 41% increase in viewership, and the constant boom of social media, runners are steadily entering the NIL track, according to Run.

“I’ve noticed track is just now getting more NIL like basketball, which has way more exposure, so they’re able to get more NIL,” Women's Track sophomore sprinter Ava Maly said. "But I feel like recently running has been kind of a trendy thing right now."

This surge in audience attention is translating into more NIL opportunities, with brands eager to capitalize on the growing interest in Women’s Basketball. Among the rise of women’s March Madness, Adidas has signed UConn’s Aaliyah Edwards, Texas A&M’s Janiah Barker and LSU’s Hailey Van Lith, according to Boardroom.

“Ultimately, it’s bigger than just NIL and being a Division I athlete and getting these brand deals now,” Melone said. “It’s about building a portfolio for yourself after athletics is done and after college.”

While athletes like Melone benefit from the newfound freedom to capitalize on their NIL, the ripple effect of this policy change reaches far beyond individual players. Coaches across the nation now have to navigate this emerging world of NIL.

One emerging challenge coaches face is the constant movement and politics within the transfer portal. This year, the NCAA changed the transfer rules so that athletes could transfer without having to sit out for the following season. This reform opened a unique opportunity for collectives, which could now leverage NIL deals to attract athletes more easily, offering financial incentives to players as part of their recruitment, according to Greenspoon Marder LLP.

The line between financial enticement and genuine attraction for

a program has now been blurred.

“You either adjust to it or you're going to get left behind, and you're not going to be able to compete,” Men’s Basketball Head Coach Ed Schilling said.

Schilling joined the Waves family for the 2024-25 basketball season. Prior to Pepperdine, Schilling coached at GCU, UCLA, UMass, University of Memphis and Indiana. Years before his coaching career, he was a starting point guard for Miami University and led his team to two NCAA Tournament appearances, according to Pepperdine Athletics.

“I kind of grew up where I felt like getting a scholarship was great,” Schilling said. “Even though I was playing in the NCAA tournament, if

I could have reaped some of the rewards from that financially, it would have been great.”

Before the 2021 policy, many collegiate athletes faced harsh consequences for monetizing their NIL, such as Reggie Bush, who was stripped of his Heisman trophy for receiving financial support from agents and boosters during his time at USC.

On Jan. 11, the NCAA sanctioned Florida State University football for the first time. This was followed an investigation into Assistant Coach Alex Atkins driving a prospect to an NIL collective meeting, where the athlete was promised $15,000 if he signed with FSU, according to ESPN.

The biggest shift from NIL that coaches have noticed is the damage done to the recruitment and transfer process.

“It’s made the divide between those that have money and booster money and all that and those that don’t,” Schilling said. “The divide has become very, very wide.”

Many NIL deals that athletes receive are from the collective, which are alumni and donors that donate to a school's specific NIL marketplace. Texas’ “Clark Field Collective” secured an initial commitment of $10 million, making it one of the largest in the country, according to Burnt Orange Nation. Alabama’s “High Tide Traditions” has also built a strong presence in the NIL market by leveraging donations and partnerships with major brands to provide lucrative deals for their athletes, according to Sports Illustrated.

These collectives enable schools to offer athletes compelling packages, both monetary and gifts, significantly impacting recruiting, as players increasingly consider NIL opportunities when choosing schools. In contrast, mid-major schools, such as Pepperdine, don’t have the same deep-pocketed NIL collectives as powerhouses like Arkansas or Kansas, making it harder to compete in recruiting, Schilling said.

“It makes it really challenging to get that elite player, where years ago you were able to go and you might be able to get a player that’s a level or

two above,” Schilling said. “Now it makes it really hard, almost impossible to get a top 20 recruit.”

This hiccup in recruiting often leads to coaches being unique and recruiting different sets of players.

“What you can do is get a player that’s not that [top 20] level or maybe hasn’t been seen, and you help them get better,” Schilling said. “The kid may be a lot better than people think.”

Collectives have become a significant part of the NIL world, allowing schools to mobilize resources to attract and retain talent. They can provide athletes with immediate financial opportunities, sometimes even before they officially join a program. Bronny James, former USC Men’s Basketball guard and son of Lebron James, received an accumulation of over $7 million in NIL deals during his high school career, according to Yahoo Finance.

Similarly, Juju Watkins, USC Women’s Basketball sophomore guard, signed with Klutch Sports Group, a sports agency, as a high school junior, becoming the first woman to do so, according to Forbes.

“I think the main surprise that people in this space were met with as NIL moved from not being allowed for college athletes to legal and then into a real thing is the rise of collectives,” Jessop said.

This approach enables schools to enhance their recruiting efforts and compete with larger programs that traditionally have more resources. The NCAA has struggled to maintain control over these collectives, particularly due to ongoing lawsuits that challenge its regulations and governance. This has led to a gray area where collectives can operate with relative freedom, sometimes leading to allegations of recruiting inducements, Jessop said.

Another significant shift NIL has created is athlete marketability. Athlete marketability now lies on several factors, primarily star power, which is influenced by an athlete’s on-field

performance and the visibility of their sport. Sports with more significant media exposure tend to attract greater NIL interest compared to lesser-known sports, Jessop said.

“If I’m a college football or men’s basketball athlete, my sport is shown on TV more than, say, rowing is,” Jessop said. “And so I have greater visibility, which brands like.”

However, NIL also produces an avenue for athletes in less-viewed sports to profit from themselves. In the digital age, an athlete’s social media profile is crucial for their marketability. Brands are increasingly looking for engagement metrics rather than just follower counts, according to Sports Business Journal. Engagement metrics refer to measurable data of how one’s social media content is being interacted with across the web.

On the other side of the screen, fans, coaches, donors and more are often given suggestions through the social media algorithm of players that are most compatible with their brand or team. This shift has created a path for traditional low-viewership sports, such as women’s basketball, according to Jessop.

“Because of the democratization of media, meaning in traditional media on TV, I have to have a decision maker decide to put my game on the screen,” Jessop said. “With social media, Instagram, TikTok, the power is in my hands.”

Despite the trend of collectives primarily funding revenue-generating sports, there are exceptions. NiJaree Canady, Texas Tech Softball junior P/UTL and 2024 Softball Collegiate Player of the Year, transferred from Stanford due to a $1 million collective from Tech.

“There’s something available, frankly, not just for every athlete, but every human if they'’e able to build their own personal brand,” Jessop said.

However, the broader implications of NIL are much more complex. The NCAA is struggling with governance, facing lawsuits that challenge its authority and policies.

One particular suit that’s emerg-

ing is one against the University of Oregon. The plaintiffs are athletes on the women’s volleyball team and women’s club rowing, and they are suing Oregon for a violation of Title IX in regards to NIL opportunities, according to McLane Middleton.

They argue that Oregon, along with Division Street and Opendorse, two NIL collective agencies Oregon partners with, is providing substantially better NIL opportunities to male athletes rather than female athletes. This violation goes directly against Title IX, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex.

These lawsuits are all centered around whether they will allow collegiate athletes to be considered “employees.” This creates a precarious situation for the NCAA, as it navigates antitrust laws while attempting to maintain control over college athletics.

“If you [the NCAA] recognize their [athletes] employee status, you gain access to this legal theory that allows you to impose the restrictions that you want,” Jessop said. “Without that, it's hard to regulate the collectives.”

Shalom Montgomery is a sophomore double major in Journalism and Political Science from Atlanta. Her favorite sports are college basketball and lacrosse. Additionally, her favorite professional athlete is Anthony Edwards while her favorite team is the Phoenix Suns.

Montgomery said her favorite sports memory is beating her rival high school in lacrosse after an intense game. Sports have added a spark to her life ,whether it be common love/ hatred for a team and giving it her all on the field.

written by Gabrielle Salgado

photos by Mary Elisabeth

Champions. Record breakers. Friends. The Pepperdine Women’s Swim and Dive team has many titles, but for them, the most important one is family.

For Swim and Dive, success comes in the form of togetherness — something the team has seen an abundance of in the last four years. In 2022, the team won their first-ever conference title, followed by a second title in 2023, according to Pepperdine Athletics.

“That was never a set goal of mine in my first year, year-and-a-half to win championships,” Head Coach Ellie Monobe said. “My goal was to bring the team together, and then from there, things just fell into place.”

Monobe started coaching at Pepperdine in August of 2020, while the entire Swim and Dive program was undergoing major leadership changes, Monobe said. She noticed a missing link between leadership and the athletes when she first joined the team.

“There was a lot of strained relationships with leadership prior to when I got there, and some trust issues paired with lacking general cohesion with leadership,” Monobe said. “They just were looking for somebody to unify them.”

Jenna Sanchez, freestyler and breaststroker alumna (‘23), said the coaching changes leading up to

the hiring of Monobe created growing pains for the team. Sanchez had Coach Joe Spahn for two months before the team transitioned to Interim Coach Jana Vincent for the remainder of the 2019-20 season.

Although she appreciated her time swimming for Spahn and Vincent, she said she is thankful for what Monobe has brought to the team.

“I’ve really appreciated how Coach Ellie has focused on our team dynamic each year and making sure that we’re all on the same page with team values and goals for the year,” Sanchez said.

Not only did Monobe join the team in the midst of coaching changes, she also started her position at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, athletes were took time away from their sports to

protect their health, Sanchez said.

“As a swimmer, I've never taken longer than a three-week break in between seasons,” Sanchez said. “And we took eight months because of COVID.”

The extended time away from the pool meant a decrease in conditioning for the swimmers. Sanchez said returning to the pool post-COVID made Monobe’s workouts feel more challenging than workouts with previous coaches, but she still enjoyed Monobe’s coaching style and workouts.

Not only has Swim and Dive won

championship titles, they have also broken multiple school records. Out of Pepperdine’s top 10 times across all events, 63% have been between the years of 2020 and 2024, according to the 2023-24 record book. The team broke 13 school records since the beginning of the 2020 season. The 13 records are split between 8 athletes - four of the records are relay events that have been broken multiple times.

Senior freestyler and breaststroker Alexandra Browne is one of those record breakers. During her sophomore season, Browne set the school record in the 50 free, 100 IM and was part of the 200 free relay and medley relay that set records, according to Pepperdine Athletics. In her junior season, Browne once again set school records in the 50 free (22.93 seconds), 100 IM (57.32 seconds) and was part of the 200 free relay team that set a school record (1:33.09 minutes).

These records once belonged to Sanchez. She said she does not feel upset when her records are broken, because they are meant to be broken.

“I feel excited every time that they break more records, because I just want that team to continue to succeed and to continue to make a good name for themselves,” Sanchez said.

Leading up to competitions, Browne said she practices mindfulness to avoid becoming too wrapped up in her head.

“My biggest thing is just remembering the passion I have for the sport,” Browne said. “Not everything relies on the time.”

Browne said the day she broke the 50 free record, she was nervous and not in the best headspace. Her warmups were slower than usual and she was becoming worried. She reminded herself why she was competing and broke the record later that day.

Browne has witnessed all of the record breaking — joining the program during her freshman year and serving as a team captain since her junior year, according to the team's Instagram.

“Just seeing someone when they touch the wall and they look up at

the time and they're so excited, it's the most fun thing to watch because you've seen them work hard, you’ve seen their ups and downs, all the work they put in,” Browne said.

Monobe’s mission to unify the team and instill team values has contributed to their success. Browne said she sees her success and efforts as a contribution to the entire team.

“You’re not just doing this for yourself anymore,” Browne said. “You’re doing it for your whole team.”

Browne said the team spends

EDITION FALL 2024 | 23

time together outside the pool, many of them living together.

“We still choose to hang out with each other outside of the sport and outside of living together,” Browne said. “So we all get along really well. I feel like it’s one big family.”

Constantly calling each other family and spending as much time together as possible has allowed the team to create inside jokes and memories, Monobe said. These memories bring the team closer together and allow for more team bonding.

One team bonding activity the team has done in the past is Secret Swive — with Swive being a combination of the words swim and dive, Sanchez said. Secret Swive works similar to Secret Santa, each team member is given the name of one of their teammates and is tasked with supporting them throughout the season. Support can come in the form of words of affirmation, notes and gifts.

When choosing team values for every season, Sanchez said family comes up every year. The family aspect is also important when recruiting new members.

“That's why recruiting is so important, and recruit trips are so important, and why the current team is always so involved in creating the next team,” Sanchez said. “We want

a part of a family, not just being an athlete for themselves.”

Family goes beyond graduation for Waves Swim and Dive. Sanchez said alumni of the program remain close to each other and continue to support the team by cheering on current swimmers at their competitions.

Last season, Swim and Dive switched to the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation (MPSF) and placed seventh in their new conference, according to Pepperdine Athletics. Monobe said she hopes the team will make more of a name for themselves at this season’s championships.

The team placed seventh overall at the 2024 MPSF championships, according to the Pepperdine Athletics website.

“We’ve had such amazing past few seasons,” Browne said. “I hope we can continue that upward trend, and I know that everyone on the team is capable of doing that. I’m excited to see everyone work hard, and all that hard work to pay off.”

However, beyond titles and trophies, the team is looking forward to bringing back more alumni and

remaining grateful for their time on the team, Monobe and Browne said.

“I hope that everyone can remember why we do the sport, because we all have that one shared passion for it, and just that common love for the sport,” Browne said.

Gabrielle Salgado is a senior Journalism major from Corcoran, Calif. Her favorite sport is baseball and she roots for the Los Angeles Dodgers. Salgado’s favorite professional athlete is former Dodgers shortstop Corey Seager.

Salgado’s favorite sports memory is when she attended her first ever professional baseball game — a 13-inning Dodgers home game against the Giants. Salgado said sports helped her gain confidence in herself and taught her she can do anything she puts her mind to.

written by Nina Fife

Mary Elisabeth

In recent years, more and more professional athletes have begun to speak out about their battles with mental health. Some of the greatest in their respective sports, like Michael Phelps and Simone Biles, have used their platforms to advocate for mental health awareness.

The vulnerability professional athletes have shared has helped create a more open environment for discussing mental health. These testimonies opened the door for these

conversations to be had at every level of athletics.

“I think it’s been helpful to be able to normalize and destigmatize mental health and some of the problems that some of those athletes are enduring,” Athletics Counselor Dr. Jorge Ballesteros said.

No matter the athlete, no matter their age, no matter their comfortability with sharing their personal struggles, Ballesteros said it is important to acknowledge the strength of student-athletes.

“They are more than just the athlete, and they're not the superhuman individuals,” Ballesteros said. “They do superhuman things, which is amazing

and great, but let’s not get lost that their mental health is very important.”

College is by no means an easy feat for students. This next step of life can be a huge period of transition, independence and adjustments. For student-athletes, they must also account for performing at the next level and balancing that with their academics and personal life, as well.

All of these factors can add up to an amounting load of pressure for collegiate athletes. That is why some schools have taken extra measures to provide support for their student-athletes.

“Mental health advocacy is important because being a student-athlete or being an athlete at any level, there’s a uniqueness with it, and it’s important to highlight that,” Ballesteros said. “We are all people, and everyone’s mental health is very important.”

Pepperdine Women’s Indoor Volleyball is one of the teams who emphasizes the importance of their athletes’ mental health.

“The coaches and the staff and the people around us are always making sure that we feel good, not just on the court, but off the court,” said Chloe Pravednikov, freshman Women’s Indoor Volleyball outside hitter.

In an interview with the Graphic in the spring 2024 semester, Head Coach Scott Wong said he commits himself to the Women’s Indoor Volleyball program. One of his focuses as a coach is making sure that everyone on his team feels like they have a voice.

“We, as a program, value our players a ton,” Wong said. “We are 100% committed and invested in helping them grow and be their best version of themselves.”

One way both players said the Women’s Indoor Volleyball coaches helped them was through individual check-ins. This support from the coaching staff helped boost connections within the team.

“The coaching staff, like Scott [Wong], was very adamant that if

there was ever anything that any of us wanted to do or say about mental health, then we had the space to do it,” Ammerman said. “He was supportive, and so, that kind of just trickled down into our relationships.”

During college, Ammerman said she realized the value of those closest to her. She found it beneficial to confide in her family and friends to help her not struggle on her own. This community of support led her to wanting to create that same community for her team.

“I felt like I struggled for a while on my own, and I learned that family and really close friends and connections can help you through those times so you don’t have to struggle alone,” Ammerman said.

These connections helped Ammerman discover the importance of vulnerability, as well. Wong said he encourages his team to talk about their problems, because it is likely they are not struggling alone.

“It makes you feel more on the same level, and humanizes athletes that are professional,” Ammerman said. “It can also help you connect and find ways to get through tough times.”

The team built themselves as a family through moments of team bonding. Ammerman said the team would have bi-weekly meetings, without coaches, where the players were able to check in with each other.

There were also more structured bonding events, especially in the preseason. At a player’s house, the team would do an intense underwater training they called XPT. Although the exercise is known to be a challenge, Ammerman said she walked away from it feeling more connected to her teammates.

“We weren’t just a volleyball team, we were like a family of sisters that would do things together,” Ammerman said. “We leaned on each other in tough times that had nothing to do with volleyball, like we were there for each other.”

Women’s Indoor Volleyball also made sure to have some fun together. Ammerman said the players would do personality tests, Secret Santa and other things that helped make them closer.

“We really tried to incorporate things off the court that connected us, so that if things on the court weren't going well, we still respected each other, we still wanted to see each other off the court,” Ammerman said.

The team carves out time during practices to allow players to share anything they may want to, volleyball related or not, Wong said. While some may not relate entirely to another person’s struggles, giving players time to express themselves can benefit the team as a whole.

“I think the more we talk and re-

late, it helps us to have a little more empathy about where people are at,” Wong said.

As a freshman, Pravednikov said this open space helped her feel comfortable to share if she needed to. She appreciates knowing she can go to her teammates if she needs to talk with them or if she needs help with anything.

“It allows me to be open, and it takes my stress load off a little,” Pravednikov said. “Knowing I have all this help, I'm never overwhelmed.”

An especially important connection on the Women’s Indoor Volleyball team is between the seniors and the new players.

Pravednikov said the upperclassmen will check in with the freshmen often to make sure they are all doing OK.

Pravednikov has even started reaching out to fellow freshmen, making it known that the entire team is all there for each other.

Ammerman said incoming players may not prioritize their mental health as much as they should. This is why the Women’s Indoor Volleyball team takes the extra step to reach out to these younger players.

“We understand exactly what you’re going through, and it’s going to be hard, but, doesn’t matter what, we are here for you,” Ammerman said. “And if you don’t trust us enough, please go see these people.”

The people Ammerman is referring to would be Pepperdine’s sports psychiatrists and the coaching staff who players have said are very supportive of student-athletes. Ammerman said the University works hard to support their student-athletes by providing them with counselors such as Ballesteros.

“There was this need,” Ballesteros said. “So, they brought on somebody, like myself, to solely focus on student-athletes, student-athlete mental health, the well-being of them and being able to provide the services that we’re able to do.”

There has been an increase in suicide rates of collegiate athletes, which calls for the need of more professionals like Ballesteros. Suicide is now the second leading cause for U.S. college athletes, doubling from a rate of 7.6% to 15.3% over the past 20 years, according to CNN.

Ballesteros is not only an Athletics Counselor, but also a sports psychologist and the Coordinator of Athletic Counseling Services. He said the counseling team offers a vari-

ety of services to athletes, including one-on-one sessions, mental health awareness tables at games and injury support groups. Earlier this year, the counseling team went to each team to make them aware of these services and how to connect with anyone if desired.

“We’re really trying to support student-athletes, not just at the athlete level, but more importantly, at the personal level,” Ballesteros said. “We’re really trying to provide the best care for them.”

It is an NCAA requirement for all athletes to complete a mental health screener at the beginning of the year, Ballesteros said. The athletes meet with Ballesteros and his team to touch on mental health and hear about the services available for them.

“I’ve really enjoyed this shift into having mental health be a high value at the NCAA level and some of the initiatives that are continuing to happen,” Ballesteros said.

One of these initiatives is the NCAA Mental Health Best Practices. This guidebook outlines what each institution can be doing to help support their players by attempting to

“protect, support and enhance the mental and physical health of student-athletes.” Ballesteros said Pepperdine has multiple people working in this realm to support the Waves.

“Both the Athletic Department and Student Affairs have been very willing to be supportive of one another, but, most importantly, very willing in support of student-athletes and their well being,” Ballesteros said.

Collaborations like these can have major benefits for athletes in offering support. Another important collaboration Pepperdine fosters is between coaching staffs and the counseling team. Ballesteros said these connections allow the staff to exchange their observations as well as build trust.

“I think here in Athletics, the coaching staffs have been very open with us and have been wanting us to really jump on board and have been able to make us feel welcome,” Ballesteros said.

Pravednikov said all of the Athletics staff is very helpful, especially reaffirming players that it is difficult to balance being a student and Division I athlete.

The emphasis of mental health is important for all athletes. Ballesteros said mental health is a topic that should be discussed at all ages.

If not addressed, the pressures athletes feel that may have started at the youth level can carry on to high school, college and sometimes, the professional level, as well. Ballesteros said if these problems can be addressed at the younger ages, it can help student-athletes as they grow.

“The more you see something, the more regular it is, the less likely you are to feel ashamed when you’re struggling,” Ammerman said.

Some incoming collegiate players may not have had a space to talk about the importance of mental health before. However, college can highlight why it is necessary to maintain this open conversation.

“By the time I got to college, I really realized the significance that

your mental health off the court can have,” Ammerman said.

Pravednikov said athletes can struggle to manage their time between their sport, school and personal relationships. Adding in the time student-athletes take away from school to travel for their sport can add to this stress, multiple Pepperdine athletes said. This struggle to balance is why mental health is so important to talk about.

“It’s just a big topic, because the sport is a big part of an athlete’s life, but it’s also keeping up with relationships and being happy off the court,” Pravednikov said.

As the struggles on and off the court could influence each other, so could the unity. Ammerman said the strength her team gained from being vulnerable and connected trickled into their on-court performance.

“I think if you trust people off the

court, you’re gonna have more success on the court,” Ammerman said. “We did have that baseline of trust and respect, which I think, stems from that understanding that we all were there for each other through mental health.”

Despite graduating in December, Ammerman said Head Coach Scott Wong reached out to her this summer and asked her to write a speech for their kids’ volleyball camp.

“It was really cool to be given the opportunity again to speak on something that's really important to me, but also something that I think is so valuable to learn at a young age,” Ammerman said.

This is just another way the Women’s Indoor Volleyball coaching staff is reaching out to players and making it known that it is important to prioritize mental health.

The Women’s Indoor Volleyball

coaching staff makes counseling services very accessible, but there are still athletes who won’t seek out help if they need it. Ballesteros said he wants to have a presence on campus to help this.

“We hope to continue to be able to be visible and available to those people who may not want to come in, at least not yet,” Ballesteros said. “If we’re able to plant the seed, that person that was very hesitant to come in is maybe more open to it by this time next spring, or even by this time next year.”

Nina Fife is a sophomore double major in Journalism and English from Long Beach, Calif. Her favorite sports are baseball and soccer and her favorite team is the Los Angeles Dodgers. Fife’s favorite professional athlete is Alex Morgan.

Fife’s favorite sports memory is when she won her city’s All-City Championship for her middle school soccer team. Fife said sports have allowed her to find her passion in life and create lasting friendships.

written by Tony Gleason photos courtesy of Gary Ashwill & Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

Editor’s Note: While the MLB recognizes seven leagues from 1920-1948 as Major Leagues, there were other leagues operating before, during and after this time period. The “Negro Leagues” referred to in this reporting is referring only to the seven leagues considered to be Major Leagues. This designation was determined by criteria created by the MLB.

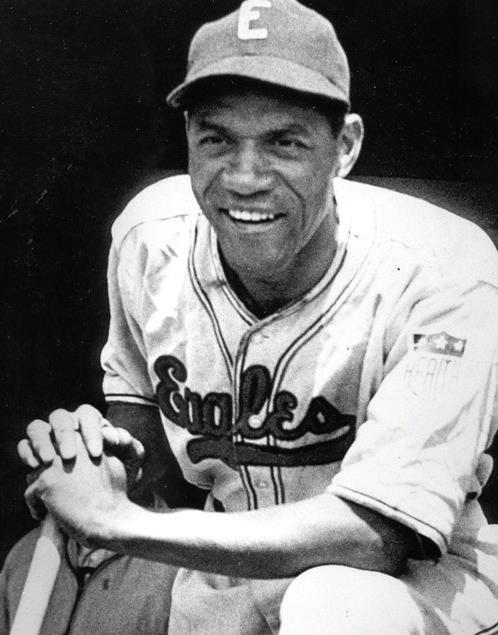

Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier for Major League Baseball in 1947. His actions were enshrined in baseball immortality, when his number 42 was retired by every MLB team and the MLB established a Jackie Robinson Day each April 15, according to the MLB. Before Robinson broke the color barrier, though, he was one of many players in the Negro Leagues.

After over half a century, MLB decided to acknowledge and remember these players and teams.

The MLB has integrated statistics from the Negro Leagues into the Major League Record Book, the MLB

announced May 29. As a result, the all-time leaderboards for the MLB changed and more people are starting to learn the story of Black baseball.

“It is anchored against the ugliness of American segregation, a horrible chapter in this country’s history,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo. “But the story here is what emerged out of segregation. This wonderful story of triumph and conquest, and it’s all based on one small, simple principle: you won’t let me play with you in the Major Leagues, then I’ll create a league of

my own.”

The reason why learning the stories of these few thousand Negro Leaguers is important is because it tells a more complete story of the history of baseball, introducing new names and players to help bring in a new audience, Negro Leagues Historian Leslie Heaphy said.

“If you're thinking about a tangible change — to be able to show up new characters, new role models, new so that you could potentially broaden your audience,” Heaphy said. “Of those who suddenly say, I see myself in the history of baseball, which I didn't see myself before.”

The MLB recognizes seven leagues between 1920 and 1948 as Major Leagues — the Negro National League (I) (1920-1931), Eastern Colored League (1923-1928), American Negro League (1929), East-West League (1932), Negro National League (II) (1933-1948) and Negro American League (1937-1948). Due to the instability of the Negro Leagues, the number of teams and length of time each league lasted varied.

Heaphy said 1948 is the cutoff because that’s when Negro Leaguers started to integrate into the MLB.

“It's the year following the reintegration of the Major Leagues with Jackie Robinson and the others that started that process that eventually brought about the decline of the eventual end of the Negro Leagues,” Heaphy said.

While these seven leagues between 1920 and 1948 are the only leagues to be given Major League status, the origins of Black baseball can be traced back to the late 1800s, and the Negro Leagues continued to exist after integration until the 1960s, Heaphy said.

Unlike the American and National League teams, Negro Leagues teams didn’t only play teams within their own leagues, nor did they have a set schedule. So, to make money, Negro Leagues teams often picked up games against minor league, semipro, independent and many other teams, multiple historians said. This

is referred to as barnstorming and was a key part of the Negro Leagues.

“There’s a lot of instability because of the fact that they were sort of operating on an economic knife,” said Gary Ashwill, creator of the Seamheads Negro League Database. “They were not making tons of money and so they always had to react to circumstances.”

As teams traveled throughout the country, Heaphy said they would pick up extra games between destinations to raise revenue. For example, if a team had a game in New York that ended Monday, with their next game scheduled for Friday in Chicago, they

would play games in cities along the way to make more money.

However, only a fraction of the games played by Negro Leagues teams are recognized as Major League games, so the amount of games played in the official record book is far fewer than how many teams actually played, multiple historians said.

“In a given season Josh Gibson and the Homestead Grays might play over a whole summer — from spring to fall — they might play 150 to 200 games,” Ashwill said. “But they might only have 60 or 70 league games, or even fewer.”

For determining which of these games would count in the updated record books, Heaphy said the MLB decided any game between two teams who were officially part of the seven leagues and counted toward each league’s respective standings would be an official game and included in the record book.

As for deciding which leagues would be given Major League status, Larry Lester, Negro Leagues historian and co-founder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, said these seven leagues were chosen because of their level of talent and how they acted similarly to American and National League teams.

“These leagues, based on existing data, showed that the teams were made up of quality ball players, they had a schedule, players had contracts,” Lester said. “They mirrored a white Major League Baseball in every aspect of the game, and therefore we deemed them to be a Major League quality.”

The creation of the Negro National League (I) — the first successful organized Black baseball league — is credited to Andrew “Rube” Foster who is referred to as the “father of Black baseball,” according to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Foster played in the pre-Negro Leagues as a pitcher from 1905 to 1917 before founding the Chicago American Giants in 1911; he then served as a player-manager for the team until 1917, according the Hall of Fame. As a manager, Kendrick said Foster was adamant about a fast, aggressive and daring style of play that would become a signature of the Negro Leagues.

“What I find so amazing is that it was that style of play that drew both Black and white fans who would oftentimes sit side by side watching what many would say was the best baseball being played in this country,” Kendrick said.

In February of 1920, after Foster made multiple efforts to create a league, he and the owners of seven other team owners held a meeting at the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, where he showed up with an official charter document, according to the MLB. The result was the creation of the Negro National League (I) — the first Black baseball league to mirror and operate parallel to the Major Leagues.

The original eight teams were the Chicago American Giants, Kansas City Monarchs, Detroit Stars, Indianapolis ABCs, Cuban Stars West, St. Louis Giants, Dayton Marcos

and Chicago Giants, according to Baseball Reference. Foster served as president and treasurer of the league while continuing as owner and manager of the American Giants until 1926, all the while, pursuing his vision was for Negro Leagues teams to merge with the MLB, Kendrick said.

“There were a number of legendary teams that were there in the Negro Leagues that would have given the best of the best in Major League Baseball a big fight for supremacy, if it had happened the way that Rube Foster had wanted it to happen,” Kendrick said. “Because Rube Foster thought he would create a league that was so dynamic that he would Force Major League Baseball's hand to expand.”

There are 35 players and 9 executives from the Negro Leagues who have been inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame, according to Hall of Fame. Of those 35 players, 24 played their entire career in the Negro Leagues.

The Homestead Grays of the Negro National League (II) had the most future Hall of Famers with 11, according to Baseball Reference.

“Larry Doby and Monte Irvin, Ernie Banks, Hank Aaron, Willie Mays — all played in the Negro Leagues

before going to Major League Baseball,” Lester said. “So this is the genesis of greatness, right there in the black leagues.”

Similar to the MLB, the Negro Leagues had a World Series of their own from 1924 to 1927 between the Negro National League (I) and Eastern Colored League and then from 1942 to 1948 between the Negro American League and Negro National League (II), according to Baseball Reference. The Crawfords had the most titles with three championships and five pennants.

One Negro Leagues World Series Kendrick said was notable was in 1942, which saw the Monarchs defeat the Crawfords with five Hall of Famers between the two teams.

“They [Monarchs] were a dynamite pitching staff that swept the

powerful Homestead Grays to win the 1942 Negro League World Series,” Kendrick said. “A World Series that was chock-filled with future Hall of Famers.”