The Sound of Healing: Exploring the Transformative Power of Sound Baths and Reiki Energy

‘We Are All Connected’: Loving One Another in Different Religions

Controversy 56

is Just a Click Away

The Sound of Healing: Exploring the Transformative Power of Sound Baths and Reiki Energy

‘We Are All Connected’: Loving One Another in Different Religions

Controversy 56

is Just a Click Away

are the words I used to pitch my idea for this magazine.

I applied to Pepperdine in 2019 with the goal of becoming editor-in-chief of Currents Magazine one day. Since then, I have filled nearly every position I could to prepare myself for this role — I have written, designed and edited for the past five editions.

Honored is an understatement for the feeling I have to be able to say this edition is finally mine — or should I say, ours. I have hand-picked and visualized each story according to what I thought you, the reader, would want to read.

The magazine is separated into sections to help guide you to the story best fit for you — Wellness, Religion, Entertainment, Culture and a For the Soul section to end on a positive note.

I have poured my heart, mind, countless hours and endless prayers into this magazine to make it something everyone can relate to. It is full of

authenticity, helpful tips, important topics and beautiful memories. Memories and the people who we make those memories with were my biggest inspiration for this magazine. Throughout it, you will find a theme of nostalgia — the bittersweet feeling of longing to relive a moment. Every story is composed of community members’ memories, experiences and views on diverse topics. I hope that out of the 20 stories inside, there is at least one that you can connect with.

This magazine has been a dream of mine and I am blessed to have some of my best friends alongside me to help it come to fruition. Every color, font, photo, drawing, headline and story has been carefully crafted to create what is before you. And so, I invite you, dear reader, to dive deep into these stories, admire the design, the photography and the art. This magazine is a gift to you from me and I thank you for allowing me to create it.

Almost every Pepperdine student has driven through Malibu Canyon with a car full of friends, windows down and music up. One day, that experience will be a memory and maybe even feel nostalgic. Featured on the cover is Chloe Jurdana and her iconic pink and blue jeep, along with Ariel Wilson, Aiden Clark and Andrew Beggs, to help you relive this euphoric memory.

From Curious George T-shirts to dad’s old sweatshirt, all staff and contributors are wearing something nostalgic to them — an item of clothing with a memory sewn deep into its stitching. Memories are what make us who we are. My parents are in some way a part of all my memories and to honor them, I am wearing my first pair of Tony Lama boots I bought with my dad and my mom’s custom Levi’s she had handmade in 2003.

“A

words by Anežka Lišková

photos by Lucian Himes

design by Abby Wilt

words by Anežka Lišková

photos by Lucian Himes

design by Abby Wilt

Sophomore Colleen Ballatore starts some of her days off with popping in her airpods, turning on her favorite podcast and going on a walk. She said it’s a way for her to get a light workout in while learning and gaining knowledge about topics she is interested in.

Many students said they engage in activites in nature for their mental health.

These can range from walking, to running, to surfing, to snowboarding. Spending time in nature can improve both mood and self-esteem, according to a 2013 National Library of Medicine article.

“Anytime I go outside for a run or walk, I feel like no matter what’s going on in my life, just getting out and getting some movement in really changes everything,” Ballatore said. “I could be having the worst day but just getting outside allows me to clear my head.”

Ballatore said she enjoys outdoor activities like running, tennis, hiking and walking. She started going on weekly walks when COVID-19 started so she could get out of the house during her online classes.

Sophomore Megan La Camera is on the cross country and track team at Pepperdine and has been running since her first year of high school. She said when she runs she feels happiness, peace and gratitude.

“[Running] definitely always improves my mood,” La Camera said. “I can’t think of one time where I felt worse after going for a run.”

La Camera said running outside is also a good way to explore a new area. She notices more new things about her surroundings while running because she can fully absorb nature.

“Being on a treadmill in the gym, there is so much going on and so many people are surrounding you,” Ballatore said. “But when you’re outside, I feel like it’s nice to just enjoy the surroundings.”

Ballatore said she enjoys running with her friends and teammates because they are always making jokes and laughing. She also enjoys running alone because she said sometimes it is nice to reflect on her life.

“The running community and runners are generally pretty disciplined and committed people, and I’ve noticed runners are great friends,” La Camera said.

First-year Logan Bole takes part in a number of different outside activities — hiking, skating, surfing and snowboarding — but he said his favorite is snowboarding.

Bole is from Louisville, Kentucky, and he first started snowboarding at the age of 14, and once he got his driver’s license, he said he had the freedom and opportunity to snowboard every weekend.

“No matter what happened, even if I rode bad that day or just didn’t have fun, maybe I fell a lot or I was just off, I still come out with a day just so happy that I was able to do that and had the opportunity to go snowboard or surf,” Bole said.

It wasn’t until Bole got to Pepperdine that he started surfing regularly.

Ballatore said getting out and doing an activity in nature always boosts her spirits.

“[Going on a walk] is so simple, and anyone can do it,” Ballatore said. “It also doesn’t matter how long or short you do it, but you’re always going to come from a walk with a better attitude and just a better mental state. I feel like you never regret a good walk.”

“I could be having the worst day but just getting outside allows me to clear my head.”

Colleen Ballatore sophomore ‘25

Life is full of ups and downs, but learning how to cope with these inevitable changes allows people to lead more mindful and peaceful lives.

Mindfulness is a person’s ability to be fully present in the moment and not let what is going on around them become overwhelming, according to Mindful.org.

Living in the moment, focusing on breathing and trying different meditations are all healthy ways to practice mindfulness, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Jason Wong, associate director of the Counseling Center, said he practices mindfulness and lowers his stress levels through cycling and running, eating healthy foods, spending time with friends and getting good quality sleep.

“When I’m feeling anxious, sometimes I feel like the thoughts could overwhelm me,” Wong said. “It’s doing things like this that allow me to redirect my focus onto something else while letting these other

thoughts flow through my mind and realign.”

Stress impacts many people on a daily basis and can inhibit them from being their best selves. Roughly three out of four people experience stress that impacts their physical and mental health, according to the American Institute of Stress.

Being mindful helps reduce activity in the part of the brain called the amygdala, according to Mindful.org. Because the amygdala helps control emotions, calming it can reduce a person’s overall level of stress.

Many people, including students and professors, said they find different ways to lower their stress levels, such as walking or listening to music.

Different aspects of health are connected, Wong said, and having a variety of coping mechanisms increases resilience.

“Effective stress management helps you break the hold stress has on your life, so you can be happier, healthier and more productive,” according to Help Guide, a nonprofit mental health site.

Great Books Professor Tuan Hoang said the main ways he focuses on being mindful are through dancing, breathing intentionally, watching shows, going for walks and taking naps.

“These ways help to minimize stress for me because they engage my body and give me something different to do from sitting, reading and grading,” Hoang said.

“Even just being outdoors in a different environment is good for my body because it gives me a break from sitting.”

Making sure his body doesn’t stay in one position for too long, Hoang said, helps to keep his body engaged and active.

“Having a routine that engages my body and mind helps me cope with the stress in my life,” Hoang said.

“Finding a variety of outlets to minimize stress is important in order to cope with stress in a healthy manner.”

Alyssa Hornback senior ‘23

Listening to music and getting a good amount of sleep are ways first-year Kaitlyn Gerrick said she handles her stress because they make her feel relaxed.

Gerrick said reducing stress allows people to put their best foot forward every day.

Senior Alyssa Hornback said exercise helps her physically destress, talking with friends allows her to receive validation and be open about what is on her mind, and spending time with God gives her peace and reorients her.

“Finding a variety of outlets to minimize stress is important in order to cope with stress in a healthy manner,” Hornback said.

If people do not find healthy ways to cope, Hornback said, they may pursue unhealthy practices.

“It’s important to find ways to manage stress because we’re complicated people and every aspect of health impacts one another,” Wong said. “They all act as a spiderweb; a single strand of a spiderweb is not that strong but when you create many strands it becomes stronger.”

While beauty and wellness play a different role in everyone’s lives, senior Ale Hurtado said she uses her podcast to inspire people to be the most authentic version of themselves.

“She Talks” is a podcast where Hurtado reflects on her life experiences and emotions while emphasizing the importance of mental well-being. Hurtado, a Public Relations major, said she lives a life of authenticity and encourages others to embrace whatever comes their way.

“The biggest thing that I want people to take away from my podcast is that they are loved, they are valued, their emotions and their feelings and who they are as an individual is so valid,” Hurtado said. “They need to just embrace their authentic selves because that truly is the most beautiful thing about them.”

Before she transferred to Pepperdine, a podcast assignment for an audio production class in her first year at Point Loma Nazarene University inspired Hurtado to begin this “passion project” of hers. Hurtado said the name, “She Talks,” came from coworkers at her old retail job who would say she talked too much.

“I take these themes essentially that I always talk about, but I’ll tie them into things I’m going through at my current point in time because

I also want people to know that I’m not perfect, no one’s perfect,” Hurtado said. “What we want to do in life is embrace our individuality and embrace those imperfections because that is what makes us beautiful human beings.”

Some of Hurtado’s biggest inspirations in the world of beauty and wellness include Glossier and Emma Chamberlain. Hurtado said she loves how Glossier creates makeup to enhance one’s natural beauty, and Chamberlain’s motto of being “unapologetically herself” motivated Hurtado to do the same.

“They both just allowed me to realize my inner beauty and my confidence and just embrace my authenticity,” Hurtado said. “Because that’s what I will always say ‘She Talks’ is about — authenticity and being genuine.”

Hurtado said she struggled with confidence in high school, but the podcast has allowed her to grow and be more honest in the way she lives her life. If she ever needs extra motivation, she will often listen to her past podcasts, journal or spend time with her friends and family.

From the moment sophomore Eden Mittelsdorf — Hurtado’s “little” in Delta Gamma — met her, she said Hurtado showed so much love, and her optimism is contagious.

“For her to share her wisdom, a podcast is definitely the best thing for her, just be-

cause she is so personable, and she can reach so many people and audiences,” Mittelsdorf said.

Mittelsdorf said one of her favorite messages from a podcast episode is about not basing happiness on others.

“Everyone who knows her loves her and knows that ‘She Talks’ podcast is a perfect representation of how she cares so much about other people and wants to share her knowledge of what she has experienced to the world,” Mittelsdorf said.

The podcast process, Hurtado said, can take anywhere from two hours to two weeks. She said she never knows when inspiration will strike her — sometimes it will happen in class and she will write down ideas and topics in the margin of a history notebook.

Hurtado’s editing process looks a little different compared to other podcasts’ — she doesn’t edit the episodes at all.

Hurtado said she will put a disclaimer in an episode in the rare case she edits it to explain why. She hopes her transparency allows her listeners to relate to her in some way and embrace their individuality.

“I’m just sitting there having a conversation with them [listeners] too,” Hurtado said. “And so that’s the true beauty and reason why I don’t edit them, so people know that they’re getting the complete unfiltered version of me.”

Ingredients:

1 cup rolled oats

1 ½ tablespoons chia seeds

16 ounces plain Greek yogurt

1 cup milk of choice

1 ½ tablespoons syrup

1 apple or in-season fruit

C a n Ehn

Instructions : Mix oats, chia seeds, plain Greek yogurt, milk and syrup in a large mixing bowl. Divide the mixture between two to three airtight containers. Keep refrigerated overnight. The next day, chop and add the in-season fruit as a topping. 1 2 3

words by Ali Levens photo by Lucian Himes design by Haley Hoidal

Instructions :

In a large nonstick skillet, heat olive oil over medium-high heat until it shimmers. Add coleslaw mix and stir until the cabbage softens and darkens. Mix in edamame and teriyaki sauce, continually stirring until the edamame is cooked through.

1 2 3

Ingredients:

1 tablespoon olive oil8 ounces coleslaw mix of cabbage and carrotsA 12to 16-ounce bag of shelled, thawed edamame¼ cup teriyaki sauce

Instructions : Prepare brown rice (or grain substitute) according to package instructions. Heat one tablespoon of olive oil in a medium skillet over medium-high heat until olive oil shimmers. Sauté the chickpeas for about two minutes. Mix in tomatoes, salt, pepper and parsley, stirring every minute or so until the mixture thickens. In a large skillet, heat two tablespoons of olive oil over medium-high heat until olive oil shimmers. Add broccoli and cook uncovered for one minute then season with salt, pepper and lemon juice before covering. Stir broccoli every two to three minutes until florets are tender and lightlycharred, or for about 10 minutes. Assemble bowls by adding a bed of rice, chickpeas and broccoli with a drizzle of creamy garlic sauce and parsley garnish.

1 2 3 4

Ingredients:

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, dividedA 15-ounce can chickpeas, rinsed and drained

1 cup canned crushed tomatoes

3 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley

5 cups small broccoli florets

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

¾ teaspoon salt, divided½ teaspoon black pepper, divided2 servings of cooked brown rice (can substitute for quinoa, farro or cauliflower rice)

Haley Hoidal

Haley Hoidal

eiki and sound baths restore the best version of myself. As I lay down on my meditation mat, my head faces the direction of the sound bowls — metal or crystal bowls practitioners swirl a mallet around to create sound vibrations

I close my eyes and feel my worries and thoughts settle down. I start to see colors. I feel my mind lightly rock from side to side as

This is when I set my intention for this meditation and try my best to center myself and let the sound bath take me on a relaxing journey. Toward the end of the meditation, my reiki practitioner comes to me and uses her hands to channel light force energy –– reiki –– into me. A feeling of warmth and light spreads

from my head to my heart to my toes. I awake and feel lighter, centered, calmer and more balanced.

“A sound bath is a meditative experience where those in attendance are ‘bathed’ in sound waves,” according to Verywellmind.

The meditation guide plays sounds in a specific sequence and frequency to create a harmonic resonance that can shift the brainwaves into a state of deep relaxation and meditation.

Reiki, which is sometimes partnered with a sound bath, is a Japanese healing technique that can help remove mental blockages and restore balance to the body’s energy centers, or chakras, according to The National Library of Medicine.

I often meditate and do sound baths and reiki with my friend, junior Vianita Corrêa.

While living in the Los Angeles area, Corrêa said she goes to The Mindry in Malibu after classes to meditate and Aziam in Santa Monica during the weekends.

After a sound bath, Corrêa said she feels more calm and stable.

“My thoughts get more clear, and I can make important decisions again without questioning myself,” Corrêa said.

Nicole Rutsch, reiki master teacher and sound healer at The Mindry, said she came to love sound baths and reiki in her healing journey. Rutsch specializes in reducing stress and anxiety and bringing people back into balance and harmony.

“In my experience, reiki has become a special ritual in my week,” Corrêa said. “After reiki I feel less anxious and more relaxed, I feel more connected to myself and my body.”

Rutsh said she specifically works with the Karuna reiki fire energy, which goes further into the body to heal deep-rooted trauma.

“Be curious and relax,” Rutsch said. “It’s all you have to do, it’s the most relaxing thing. You don’t have to do anything. Just allow space, allow the practitioner to hold space for you, experience it.”

Chrissy MJ Anderson, studio manager and meditation guide at The Mindry, said she has struggled with depression and anxiety

that stemmed from overworking herself.

“I woke up one morning and couldn’t get out of bed,” Anderson said. “Two years of depression where I didn’t work, and I wasn’t able to do much of anything.”

Anderson’s psychiatrist recommended a meditation center to Anderson called The Den about four years ago and told her to try natural healing. Anderson said the meditation helped her slowly stop abusing substances, inspired her to start pilates and helped her stop fighting with her boyfriend — all within a span of three weeks.

“I had the profound experience where I had this release and relief and thought, ‘This is how I get better,’” Anderson said.

One of Anderson’s meditation teachers at The Den also worked at The Mindry, which is how Anderson found out about it.

“The one-on-one connection with teachers and guides who support your healing journey is a one-of-a-kind experience, and then learning reiki allowed me to do this for others,” Anderson said.

Before her healing, Anderson said she used to laugh at people who did yoga and meditation.

“I realized they’re actually this [happy] because there is this beautiful experience on the other side,” Anderson said. “There’s this whole other world that many don’t access.”

Anderson urged those who are skeptical or want to try any form of meditation to do it.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re trying so hard to have this transformative spiritual experience, what matters is that you are exploring something new and learning these tools to come back to balance in any situation or feeling that you are in,” Anderson said.

Those who go to sound baths want to feel relaxed and nurtured, Anderson said. Those who practice reiki want to experience healing at that moment, and they start to realize what they need right then.

“I was never able to see the light at the end of the tunnel when I wasn’t well,” Anderson said. “I realized there was a light at the end of the tunnel, now I can see the light, and I walk with it now.”

“My thoughts get more clear, and I can make important decisions again without questioning myself.”

Vianita Corrêa junior ‘24

Sophomore Lily Vu said she has a set daily skin-care routine. The routine has multiple steps depending on the time of day.

“In the morning, I would say that I don’t wash my face with any cleanser because it’s good to leave natural oils on your face,” Vu said. “You don’t want to strip your face [of] natural oils because that can also cause acne.”

After rinsing her face with water, Vu moisturizes and uses her Super Goop sun screen. In the evening, Vu said she uses her CeraVe cleanser, Sonya Dakar serums and a tretinoin cream her dermatologist prescribed.

Vu said she usually gets her skin-care recommendations from social media, YouTube and her roommate, soph omore Colleen Ballatore.

She said she uses Sonya Dakar because she saw Maddie Ziegler use it on social media, and she ended up really liking it.

Junior Deslyn Williams said she uses TikTok for her skin-care inspirations. If she and an influencer have simi lar skin-care goals, she said she will listen to them and later look through reviews of the products to determine if it’s the right fit. One skin-care trend TikTok introduced her to is slugging. Williams said she now does this five to six times a week.

Slugging is applying a generous

amount of petroleum jelly on one’s skin as the last step of an evening skin-care routine, according to The Washington Post. It mois turizes, protects the skin barrier and helps dehydrated skin, according to Healthline.

For Williams, skin care isn’t just taking

care of her skin — she said it is a form of self care.

Senior Loren Eastman said she started using skin care in middle school when her mom gave her a Proactiv skin-care set. As she grew up, she learned skin-care tips from social media, and she said TikTok trends influenced her. She said she built her skin-care collection around products from The Ordinary brand.

“What we forget about a lot is that

your skin is an organ,” Eastman said. “It’s the outermost protective layer of your body, so it’s not only the thing that people see first, but it’s the thing that your body interacts with the environment first.”

Eastman said she started using The Ordinary because she liked the packaging, but she ended up liking the products too. Niacinamide, Zinc PCA and Sodium

Hyaluronate are used in their formulas, according to The Ordinary’s website.

“Those [ingredients] are pure extracts and compounds that are derived from vitamins that are the raw ingredients that your skin can really use,” Eastman said.

Love, and how people show and receive it, comes in many forms. These acts of love, or loving kindness, reverberate throughout people of different religious beliefs.

“We need to grant each other the dignity of difference, we also need to find those things that build bridges between our differences — and loving kindness does that,” said John Barton, professor of religion and philosophy and director for the Center of Faith and Learning.

A thread Barton said connects world religions is what is known in Christianity as the Golden Rule.

“‘Do unto others as you’d have them do unto you,’” Barton said. “Which Christians find in Matthew 7:12, but a version of that is found in Confucianism, Hinduism and Jainism. I mean, it’s everywhere — Sikhism, Bahai, I mean, it’s just everywhere.”

Barton said his primary research and teaching area is religious diversity and world religions. Barton published a book, “Better Religions,” on Oct. 1, about building peace between different religions. He points to the shared belief in the Golden Rule as one way forward.

Confucianism is a school of ideological thought focused on social and cultural eti-

the earliest versions of the Golden Rule, which we find in the teachings of Confucius, which is at least half a millennium before Jesus said it,” Barton said.

Confucius’ writings point toward orderliness in daily and social life, and values universal kindness.

“Confucius actually states it in the opposite way that Jesus does,” Barton said. “Jesus says, ‘Do unto others as you’d have them do unto you.’ Confucius says something like, ‘Don’t do to others what you don’t want them to do to you.’”

Daoism also has a version of the Golden Rule, Barton said — detailing living without resistance and in harmony with the flow of the cosmos.

From a nonreligious perspective, Barton said Utilitarianism is the most popular ethical theory today that has this ethuc.

“It says we should always act in such a way that brings about the greatest amount of happiness to the greatest number of people,” Barton said.

The motivation here, Barton said,

that I find isn’t an essential core, but it’s a useful overlap that we find in all religions,” Barton said. “It gives us a platform.”

Barton said because religions are so diverse, not every religion has an exact one-to-one translation of the word love.

“Love is very much a concept that is at home in the Abrahamic religions,” Barton said. “So Judaism, Christianity and Islam.”

Judaism uses ‘chesed’ to mean loving kindness, Barton said. Throughout the Hebrew Bible — especially in the Psalms — people respond to God’s loving kindness with praise.

In Christianity, there is the word ‘agape,’ which has a core concept of unconditional love, Barton said.

“I would say that the Greek concept that we find in the New Testament is a Greek derivation of chesed, the idea of God’s loving kindness that God is a God of loving kindness, unconditional loving kindness,”

“The thing that holds together all the world’s traditions, all the world’s religious traditions, is not as much concepts or ideas about God and the universe or doctrines, but it’s an ethic.”

peace and solace.

“This idea that the foundations of peace is this mutual compassion, mutual mercy, this mutual love that we extend to one another, and that’s what God calls people to,” Barton said.

Islam is very clear — this love should be extended to others, Barton said.

When speaking about the Indian religions — Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism — Barton said while there may not be a direct translation for the word love, there is an “ethic of loving kindness.”

The word ‘karuna’ is the Sanskrit word for compassion, Barton said. In Hinduism and Jainism, there is the concept of ‘ahimsa,’ meaning “non-harm” or nonviolence. These ideas, and the ethic of mercy and compassion, is very similar to the Abrahamic concept of love.

“The thing that holds together all the world’s traditions, all the world’s religious traditions, is not as much concepts or ideas about God and the universe or doctrines, but it’s an ethic,” Barton said.

Serah Hodson, senior and intern for Relationship IQ, said a huge meaning of the

Hodson said she was raised in a nondenominational Protestant church from birth and was “steeped in Christianity” her entire life before coming to Pepperdine.

As a child, Hodson said her faith was very legalistic — and it wasn’t until she was 12 that she learned what it meant for God to love her. Hodson said it is still easy for her to fall back into that legalistic lens.

However, when she believes God loves everyone unconditionally, Hodson said her experiences are more holistic.

“Then my interactions with other people are not dependent on what they do or the boxes they check or how good I think they are, but dependent on like, I believe that there is something worthy and good in the core of you,” Hodson said.

Love, Hodson said, prompts her to make the people around her better — she sees this in the context of her interactions with her younger sister and the advice she has given her.

“It’s really cool to see the ways that I’ve poured into her and tried to teach her —

to pour into other people, teach other people, because she loves them,” Hodson said.

Art Professor Yvette Gellis said her husband, Andrew, is Jewish, whereas she was raised Roman Catholic. In her “deep relationship” with Jesus Christ, Gellis said she learned to love without judgment.

“What does matter is the original message of Jesus Christ, which was one of love, and then you start to see that we’re all connected, everyone,” Gellis said. “That’s why in an interfaith marriage, it didn’t matter. Because we are all connected.”

After a month of dating, Gellis said her husband invited her to a Bar Mitzvah. This was her first time attending a Jewish service, and Gellis said her husband showed her how seriously he took his faith, which impressed her.

“I saw that he would be a wonderful father,” Gellis said. “I saw that he would be faithful to me. I saw that he was an honorable man, who had an enormous amount of integrity. And I fell in love. I knew in that moment, I could marry him.”

Another month went by and the two went on a camping trip up the face of Yosemite. On the way down, Gellis said Andrew asked her to marry him, to which she replied to him,“Really?”

She would say yes the third time he asked.

Junior Eddie Li said for him, love is being generous to people. Growing up in China, Li said he studied Confucianism, which impacted his life.

“[Confucius] definitely sees love similar to the way I do,” Li said. “He definitely doesn’t want to stop or delve into a romantic love. His love is a love between relations — families, friends, between people — even people we are not familiar with, with strangers. It is one of the most exceptional elements to his vision of an ideal society.”

A world that practiced love like Confucius would be more peaceful, Li said, because everyone would be content in their love.

Parents, for example, may not often express love to their child verbally, Li said, but rather express it through actions — such as cooking.

“Love is more continuous,” Li said. “Kindness can be shown from time to time, but love is pretty consistent. It happens on a regular basis, whereas kindness can be shown to anybody at any time.”

Love, Li said, is more of a choice, but people are inclined to love each other.

“Confucius will say that you have to love everybody,” Li said. “But he is demanding that for a sage and that is not something I can attain as a normal human being. But it is a path to work toward.”

The unity of a shared ethic of “loving kindness,” Barton said, provides a way to connect people who have vastly different lived experiences.

While the one-to-one translation of love may not exist in all religions, Barton said loving kindness does. These joint ethics help people navigate an increasingly globalized world.

“While it has been true for thousands of years that this Golden Rule ethic is a thread between and among different religions, that fact is more urgently important in the 21st century than it has ever been, because we’re living in each other’s backyards,” Barton said.

When preparing for marriage, Gellis said all the priests and rabbis wanted to know was how they would raise their children — which Gellis said they never really talked about.

The most important thing, Gellis said, is support for one another.

“I will say, it’s easier if you find someone in your own faith, without a doubt,” Gellis said. “But if you have that kind of love, you support each other — my husband never once didn’t support who I was as a person.”

Hodson said she uses her knowledge that God loves her as a guidepost when interacting with a faith community where there is a lot of judgment and tradition mixed with social positioning.

“Being aware of the image of God in other people allows me to, in a day-today kind of way, ignore divisions between people and more like, not ignore, but pick a better thing to focus on,” Hodson said.

“What does matter is the original message of Jesus Christ, which was one of love, and then you start to see that we’re all connected, everyone.”

Yvette Gellis art professor

words by Marley Penagos

photos by Lucian Himes design by Haley Hoidal

At Nepal-Tibet Imports in the small town of Fort Collins, Colorado, a miniature statue of the Virgin Mary sits high upon a shelf, right next to statues of Hindu deities Ganesha and Shiva.

The statue was a gift for the shop owner, Pradesh, from junior Ginger Jacobs, who visited the shop for a class project in her world religions class.

Religion Professor Dyron Daughrity assigned Jacobs to interview someone from an Eastern religion, and she chose the shop owner in her hometown. That interview and the remainder of her world religions class were transformative for her, Jacobs said.

“He [The shop owner] had the best analogy — he told me, ‘If you were trying to get to Denver from Fort Collins, you could take the I-25, you could take College, you could take 25 different roads to get to Denver, but they will all lead to the same place,’” Jacobs said. “You could go a million different ways, and you could get to the same place, and that’s kind of how I see religion.”

to sign their name and identify with one of them,” said Falon Barton, University Church of Christ campus minister.

Barton said ‘nones’ occasionally will identify with more than one descriptor on a form, but there are many people who believe none of the terms resonate with them and just want to write ‘none.’

A majority of these ‘nones’ are young, according to research by Byron Johnson, visiting professor of Religious Studies and the Common Good at the School of Public Policy. Barton said she has seen a similar trend.

“I have seen people younger than 30ish — emerging adults — as they are exposed to different things in the world, they are more open to the idea that the Spirit of God is in all things,” Barton said. “If they’re Christians, it’s like, ‘Yes, Jesus is Lord,’ and if Jesus is everywhere, then where is Jesus in these other faiths?”

The ‘nones’ Jacobs does not believe her religion can fit in a

She is amongly 29% percent of adults in the United-cording to Pew Research Center. Pew defines -

ists, who do not believe in God at all; agnostics, who are unsure what they believe about God; and ‘nothing in particular,’ which includes those who may believe in a higher power or hold spiritual beliefs but do not affiliate with -

dergraduate students identify as ‘religiously unaffiliated,’ with 95% of those students choosing ‘none’ or ‘undeclared,’ according to the -

“Religious nones are people who don’t really want to, or don’t stronglytor words on a form that they’re willing

As a child, Jacobs’ parents enrolled her in Roman Catholic school for elementary and middle school, where she said she realized she loved Catholic traditions.

“I loved going to church every Friday and Adoration every Wednesday, and I would get my parents to take me to church on Sunday,” Jacobs said.

Though she said she is still “technically Catholic” when prompted to check a box on a survey, Jacobs does not think that ‘Catholic’ truly defines her beliefs.

“At least now, I don’t ever see myself coming to a conclusion of what box to check, and I’m sure that will change,” Jacobs said. “That’s the beauty of it, because I’d say that your spiritual journey is never really static, and that is what makes it so important and beautiful in your life.”

Like Jacobs, junior Bob Emrich grew up in a religious community, with both of his parents working at Pepperdine. He attended Our Lady of Malibu for seventh and eighth grade, but unlike Jacobs, he said Catholic school pushed him away from religion. Emrich now identifies as agnostic.

“It doesn’t really help when it [the school] tries to make you one with the religion that they are trying to make you follow,” Emrich said. “It can be off-putting and overwhelming.”

Despite this negative experience, Emrich is open to the idea that his religion will change, and he could one day choose a different box to check.

“If I somehow come into a place where I have the belief that there is something definitive then that is what it is,” Emrich said. “It just hasn’t happened yet.”

In learning about the religions of the world, Jacobs said she adopted values from other religions that live in tandem with her Catholic beliefs.

Jacobs drew from the Jain tradition of ahimsa, which according to National Geographic is a strict code of nonviolence that means not killing or harming even the tiniest creatures. Some Jain monks carry a broom to gently sweep ants and small bugs out of the way of their feet.

“I can’t remember the last time that I willingly or intentionally killed a bug or an insect,” Jacobs said. “Jainism has played a big part in my life. Hinduism has played a big part in my life, and Daoism and Buddhism. I am just fascinated with learning about it too.”

First-year Julianna Thomas said she identifies as “Christian with a twinge.” She said this means following the teachings of Jesus Christ, but having beliefs about the entity of “God” that do not line up with Christian teachings.

“God is in every single person on the planet, and I think that we eventually all return to that source energy, which is God,” Thomas said. “So that’s where things get a little twisted in terms of like actually being totally Christian. I don’t think God is a

person. I think God is an energy.”

She said she believes in concepts and ideas that Christians traditionally do not believe in, like reincarnation or samsara, which according to Encyclopedia Britannica, are most prevalent in Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism.

Thomas said her childhood best friend, Sanvi, and her family are Hindu. She said she would attend all of their family parties and religious celebrations.

“That experience for me really made me start questioning my beliefs, because these people don’t believe in Jesus, or the same God that I necessarily believe in, but they can’t possibly be going to hell,” Thomas said.

Emrich’s main exposure to religion has been the Pepperdine community and his Catholic schooling, but he said he embraces the question mark of agnosticism and keeps the door open for a religion he can definitively believe in.

Emrich said humans use religion as a way to explain “our morality,” and he would also like to have an answer to what happens after death.

“A lot of different religions exist as a result of this, and I agree with them in that I would like to have some logical mortal explanation for what happens after we die,” Emrich said. “But I don’t really think

“At least now, I don’t ever see myself coming to a conclusion of what box to check, and I’m sure that will change. That’s the beauty of it, because I’d say that your spiritual journey is never really static, and that is what makes it so important and beautiful in your life.”

Ginger Jacobs

junior ‘24

we have a right to assume whatever that higher power is. It could be whatever you want it to be.”

Americans are becoming less religious and more spiritual, according to Pew Research Center.

Daughrity said the meanings of religion and spirituality are imprecise and often conflated — and quantitative survey-style research yields more ‘nonreligious’ results than qualitative interview-style research with the same population.

For example, Daughrity cited research by Abby Day, a sociology professor at Goldsmiths, University of London, where people who selected ‘none’ on a survey went on to describe how they pray, believe in God or gods and believe in the afterlife during a follow-up interview; things that are closely associated with religiosity.

“Abby Day gets these people and she says, ‘OK, you clicked the box that said none, so are you religious?’” Daughrity said. “And they say, ‘No, I don’t think I’m religious.’ And she says, ‘Are you spiritual?’ And they say, ‘Yeah, I think I’m spiritual.’ But there is no difference between religion and spirituality. Religiosity, spirituality, I mean tomato to-mah-to.”

Thomas disagrees. She said she would

identify as spiritual and not religious.

“The term spiritual has so many less boundaries, and I think the term ‘religious’ upholds a system that I do not align with,” Thomas said.

Being “spiritually curious,” Thomas said, means she does not have an institution defining her personal beliefs.

Barton said young people may cling more closely to the idea of spirituality because they believe organized religion has let them down, as churches both in the United States and abroad have taken some polarizing and divisive stances.

For instance, KingdomLife Church in Dallas, Texas, broke the law forbidding nonprofits from endorsing political candidates and endorsed candidates who advocated for expanded gun rights and abortion bans, according to the Texas Tribune.

Barton said 18 to 29-year-olds are extremely spiritual.

“They’re very interested in spirituality, they are very disillusioned by institutionalized religion in general, with a lot of good reasons,” she said.

Thomas said the churches’ stance on same-sex marriage is one reason she moved away from the church.

“The hate — the whole ‘Love the sinner, hate the sin,’ type of thing, it’s just not consistent — it’s an oxymoron,” Thomas

said. “I think that makes people feel as though their life is just totally invalidated in the eyes of God.”

Many churches, Thomas said, also have too many unattainable expectations that do not relate to Jesus’ teachings in the Bible and can cause members of those churches to constantly feel not good enough or experience self-hatred. She said she believes the more those boundaries are torn down, the more individuals will be able to grow together as a “spiritual collective.”

Barton said she does not think the growing population of ‘spiritual nones’ is necessarily a bad thing.

“Oftentimes people of faith, Christian and otherwise, who hear ‘nones,’ can hear it with a lot of anxiety, as a threat to not just their religion but to religion in general,” Barton said. “I don’t hear it that way, I hear it as a word very much of hope.”

Barton said she believes young people are asking the hard questions and care about important things, regardless of religious affiliation.

“They care about justice, they care about morality, they care about the way we treat people near and far — our immediate neighbors and our global neighbors,” Barton said. “And that is really comforting to me, so I am very grateful for that.”

words by Joe Heinemann photo courtesy of Merrill Moses design by Abby Wilt

he International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame (Yad Le’ish Hasport Hayehudi) inducted Pepperdine Water Polo Coach Merrill Moses on Jan. 15.

The Hall of Fame picked Merrill Moses, a 2008 Olympic silver medalist for the U.S. Water Polo team, due to his contributions in three Olympic games and his three gold medals in the Pan-American games.

Moses now coaches the Pepperdine

Moses’ induction into the hall of fame will give him a chance to visit Israel in 2025. Moses said he viewed this induction as both an honor and an opportunity to connect deeper with his background.

“It means a lot because it’s all that hard work paying off and being recognized, but also being recognized amongst the Jewish athletes and what we’ve done,” Moses said. “And so I think it’s a very special honor.”

Moses said he came across the sport that changed his life in high school.

“I started going around the school looking at different sports, heard the whistles and saw this offense [position] for water polo and asked the coach if I could try it out,” Moses said.

After high school, Moses sought to play water polo at Pepperdine. Because he wasn’t recruited, Moses said he got into

Pepperdine with his grades.

He said he achieved his goal of becoming one of the best players in his field. Moses believed he and his teammates could win a national championship, and they did in 1997.

Moses said he attributes much of his success during college to Pepperdine coaching.

“Coach Schroeder has had a big influence on my life,” Moses said. “He’s the one that gave me a chance to walk onto Pepperdine.”

Moses said he decided to pursue coaching at Pepperdine in 2013.

“I plan on being at Pepperdine for a very long time, and I would love nothing more than to finish my career [at Pepperdine],” Moses said.

Religion has played a role in Moses’ water polo journey, he said.

“No matter what religion you come from, I just think religion is great,” Moses said. “It instills great values into people.”

Moses explained the importance of religion in building the framework for how athletes should act both in and out of the pool.

“The biggest thing it’s made me aware of is you always can look back at the Torah or the Bible and get life lessons,” Moses said. “I learned the Bible going to Pepperdine, and I love the Bible as well. So I just think it [religion] has influenced me like it should influence everyone, which is to be a great person and also treat people how you want to be treated.”

“It [religion] instills great values into people.”

Merrill Moses water polo coach

The Struggles of Fatigue in Ministry

Christianity has been declining in the United States since the late 1970s, according to the Pew Research Center, and amid a shrinking flock, the ministers who shepherd it are experiencing record levels of fatigue.

The Barna Group did a study in March 2022 revealing that 42% of American pastors considered quitting full-time ministry over the course of the prior year, an increase from 29% the year before. This increase is an indicator of the exhaustion many ministers are experiencing.

“It’s exhausting in particular ways that just ‘going to work’ isn’t,” said Adam Mearse, Bible and Logic teacher at the Academy of Classical Christian Studies in Oklahoma City, and a former youth pastor of 20 years. “It’s based on pouring something of yourself out, which means at some point you can run out of stuff to pour.”

Barna found that the top three reasons pastors considered quitting were stress, loneliness and political division. The leading reason, “the immense stress of the job,” may be challenging to quantify, but for many in ministry, it can feel like a round-the-clock job.

“You start to be like, ‘I don’t know what it’s like to not feel like I’m ministering all the time,’” Mearse said.

Even when Mearse was off the clock, he said he would be with people from church, so it felt like he was still working. Danny Quintero, a youth minister at the Inland Valley Church of Christ in Ontario, agreed.

“You don’t know what the line is between your life and others’ lives,” Quintero said. “You need time for yourself, and people need your time as well.”

A minister’s place in the community is also a prominent one, leading to less privacy than most people enjoy, Mearse said.

“We might as well have the fishbowl-kind-of life,” Mearse said.

Mearse said occasionally the “fishbowl-kind-of life” included criticism of aspects of his private life that other occupations don’t experience.

Mearse also said those closest to a minister share some of the burden, especially spouses and children.

“Where I have experienced burnout has been for me in the pressure between family and ministry,” said Amy Bost-Henegar, chaplain at the Long Beach Memorial Medical Center and former associate minister at the Manhattan Church of Christ in New York.

For Bost-Henegar, someone caught in this “unique intersection” is her son, Aidan Henegar, a Pepperdine junior Religion and Economics major.

“Growing up in a church and having someone [from his family] on the ministry staff, it definitely made me always feel like I was a little bit more like, bound to that and a part of that,” Henegar said. “Which is sometimes good and sometimes bad.”

Bost-Henegar also said being female in a male-dominated field can compound fatigue.

“The church traditionally is pretty patriarchal, and so women are dealing with sexism and systemic bias,” Bost-Henegar said. “That can be really, really exhausting.”

“It’s [ministry’s] exhausting in particular ways that just going to work isn’t. It’s based on pouring something of yourself out, which means at some point you can run out of stuff to pour.”

Adam Mearse

Another challenging topic of conversation for ministers is finances.

“I remember one time I asked for a raise at a church that I was working at,” said Zac Luben, director of graduate school ministries at the Hub for Spiritual Life. “It felt almost like I had asked to sacrifice someone’s kid.”

Luben said he has felt the disparity in pay between himself and colleagues in other fields. The average annual salary of clergy in the United States is $57,230, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“People were like, ‘Oh, man you get to go camping. We’re sending you on vacation and we’re paying you for it, that’s great,’” Luben said. “I’m hanging out with 15 to 16-year-old guys, 24 hours a day, sleeping in really gross cabins. That’s not a vacation, and if it is then your definition of vacation probably needs to change.”

Other financial stressors arise when discussing church organization. Luben said many churches are organized like businesses even though pastoral care is challenging to quantify like a business.

“There’s an anxiety and I think that anxiety can drive us into business models,” Luben said. “But it seems problematic when, on one hand, we identify and recognize that spiritual growth isn’t super easy to assess, and then we’re forcing sort of these business-like assessments into a church setting.”

Finally, political division has led to frustration for many ministers, said Adam England, youth and family minister at Westside Church of Christ in Bakersfield.

“That’s a big part of the burn up that I experience, at least because there’s just so many sacred aspects now,” England said. “Almost anything and everything is going to tick someone off, and we’re so conflict averse that it just becomes regular confrontation.”

England specifically said he doesn’t experience burnout as much as “burn up,” which he said is when he knows why he’s doing what he does, but experiences detachment from it as a result of fatigue.

Eric Wilson, preaching minister at the University Church of Christ, said at one of the first churches he worked at, he saw up close what burnout looked like in his co-minister.

“I was close to watching somebody implode,” Wilson said. “I was like, ‘Hey, man, do you think you should probably take a break?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, sure,’ and he didn’t, he just kept on pushing through, and it was disastrous.”

This experience made a distinct impression on

Wilson, helping to form a philosophy he said he has carried throughout his whole career.

“That’s when I committed to myself: If I saw red flags, I would respond to red flags,” Wilson said.

Wilson rests when he feels it is necessary, he said, and that it is not just about reducing stress but recalibrating toward God.

“It’s a job that requires constant awareness of the presence of God in my life, in everybody else’s life and in the world, and to show up as a caretaker of all that,” Wilson said.

For Henegar, the moments of self care in Jesus’ own ministry give a frame for what is needed in ministry.

“Even Jesus at the start of his ministry was very aware of his own needs and conscious of and set on what he was meant to do,” Henegar said.

Having a network of people outside of the church is also an important way to eliminate some of the stresses of the job. Mearse, England and Bost-Henegar all said this strategy is helpful.

“What you start to learn over time is you need some confidants,” Mearse said. “Some people in your life that you can be really honest with and those people can’t really be in the same church that you’re in.”

Ultimately, the solution comes down to more awareness, communication and mindfulness of how churches are organized and how those in ministry feel about their workload, all of the ministers said.

“The leadership needs to know that you are not Jesus and you need to know that you are not Jesus,” Quintero said.

The first step in solving a problem is admitting you have one, England said.

“If the person who’s reading this article is sitting there wondering, ‘Do my people have a problem?’ They probably do, because they don’t know,” England said. “A good leader will read that and go, ‘I know where my person is struggling,’ or ‘We’ve worked through the struggles that they’ve been having.’”

The problem is not confined to the church alone, as Wilson said — the church is a “reflection of society,” so ministry burnout is indicative of a more widespread epidemic.

“Let’s also not pretend that all other sections of our country are just humming along, right?” Luben said. “That there’s only this particular area where burnout is being experienced. The minister really has a really significant role to play as they help other people live through burnout.”

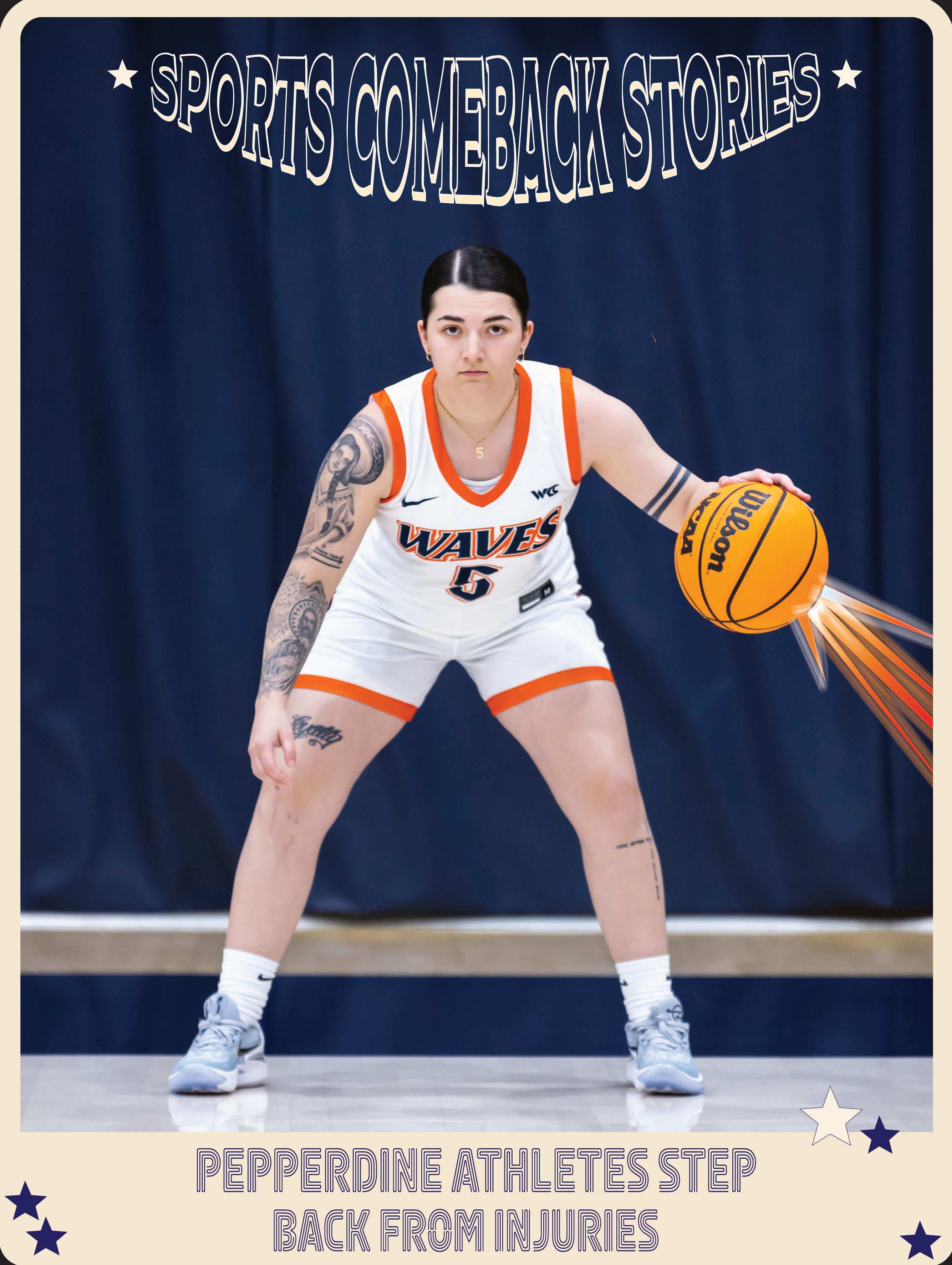

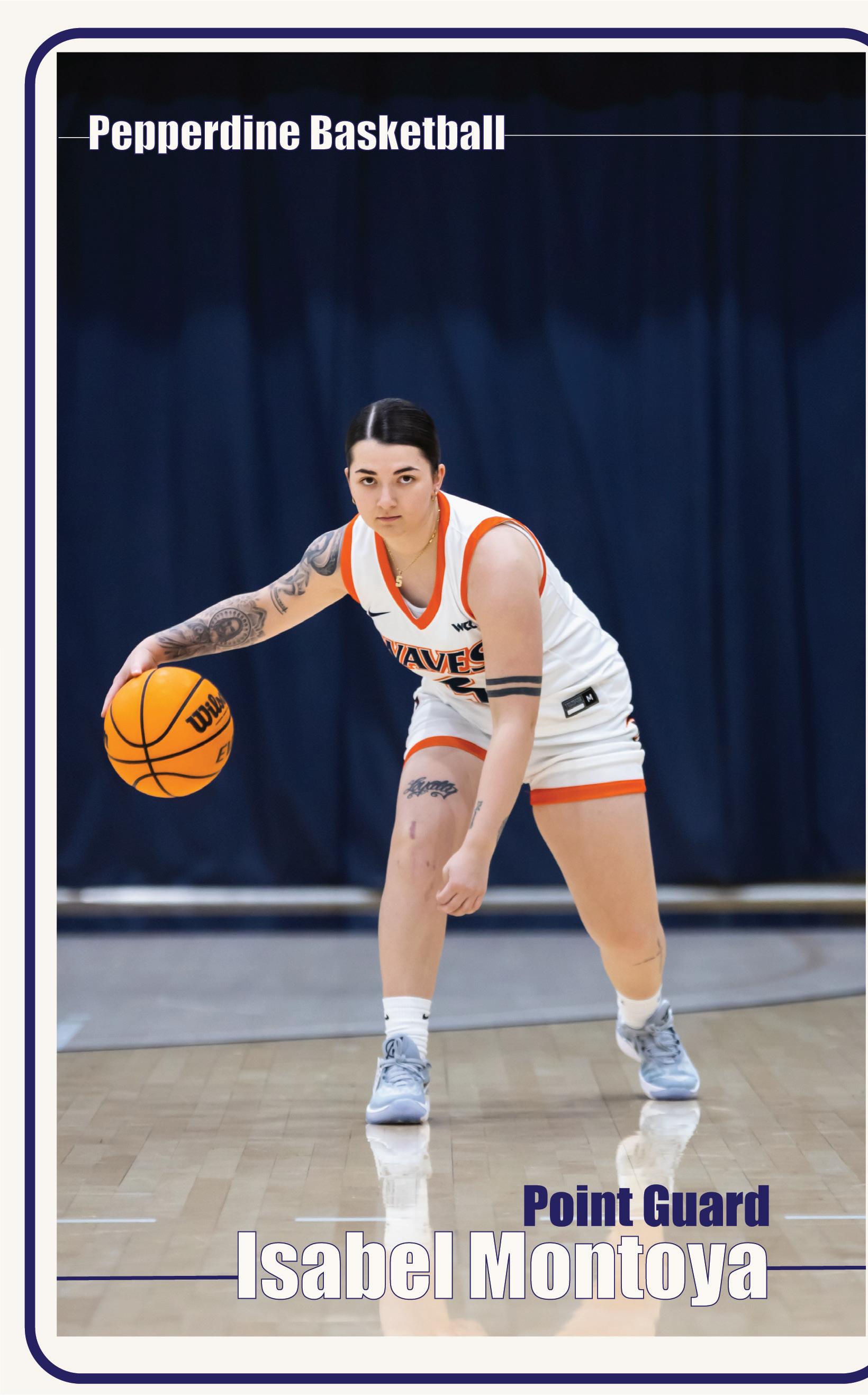

tear her sophomore year and discovered a hip injury last semester.

“It’s not my first rodeo, unfortunately,” Montoya said. “This recent one was a labral tear in my hip.”

After exploring treatment options, Montoya said she underwent her fifth injury-related surgery to treat the tear.

Krizan, athletics counselor for Pepperdine Athletics.

“There is maturity and resilience that is grown from having those experiences,” Krizan said. “On the flip side to that, it can be quite frustrating.”

Junior Isabel Montoya, women’s basketball point guard, said her first experience with basketball was playing pickup in elementary school.

“It was the first sport where I really had to prove something,” Montoya said. “I really fell in love with getting better and making friends out of it — and then I learned you can get full-ride scholarships.”

Montoya, however, has not seen the court since the 2020-21 season. She said she suffered an anterior cruciate ligament

Injuries like Montoya’s labral tear often have a lengthy recovery process, forcing athletes to miss playing time, said Dr. Grant Garrigues, a shoulder and elbow injury specialist and co-team physician for the Chicago White Sox, Chicago Bulls and DePaul University.

“The rotator cuff or the ulnar collateral ligament or hip labrum, they’re so full of stout, structural tissue,” Garrigues said. “There’s not a lot of robust blood supply and healing response, so they heal very slowly.”

How athletes recover from injuries is a complex and difficult process that can change the mindsets of athletes, said Dan

Krizan, a former athlete himself, was a member of George Washington University Swim and Dive from 2008 to 2012. He said his position at Pepperdine functions as a hybrid between the Counseling Center — such as being on call for the Counseling Center’s 24/7 crisis phone line — and supporting athletes, particularly with their mental well-being.

“One of the biggest things that [an injury] does is that it allows them a chance to explore more identities about themselves outside of their sport,” Krizan said.

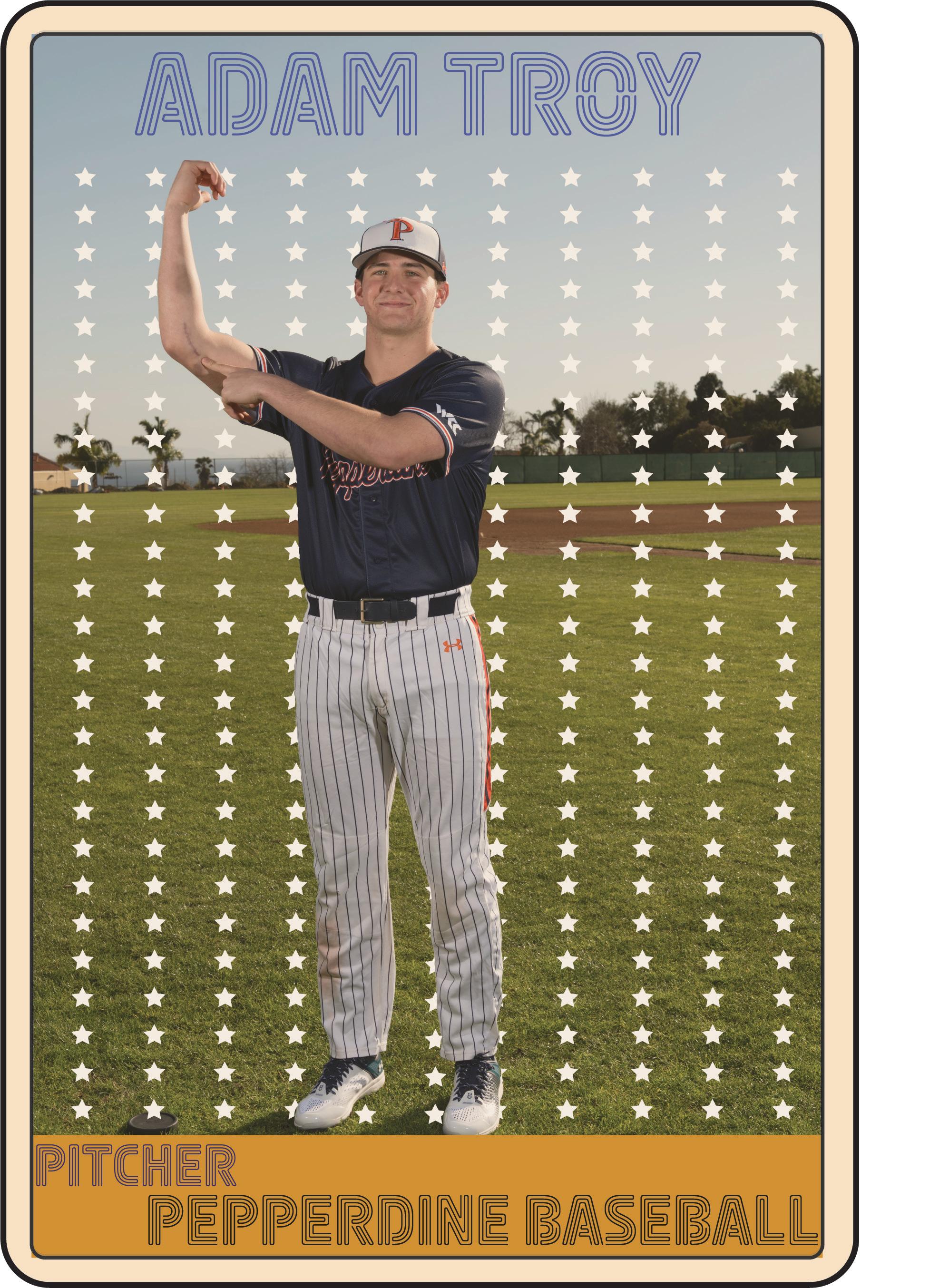

Baseball first-year pitcher Adam Troy, who is recovering from his first major sports-related injury, an ulnar collateral ligament tear in his elbow, said he has had an extensive recovery process.

Garrigues said UCL tears are exceedingly common among pitchers.

“Whenever a pro athlete throws, they’re throwing at the limit of what the body can take,” Garrigues said.

UCL reconstruction, more commonly known as Tommy John surgery — named after Hall of Fame pitcher Tommy John, the first pitcher to undergo the surgery — is the go-to treatment for UCL tears, Garrigues said.

It is a common misconception that players will actually improve in performance following Tommy John surgery, Garrigues said, however, 85% of patients can return to their initial physical performance following the procedure.

Troy underwent this surgery in June

and said he has been on a 14-month recovery plan since. He has approached his rehabilitation with discipline and drive, he said, but still feels the difficulties that come with recovery.

“There are still those days when you’re out there at baseball practice kind of watching from the sidelines, and you’re just not wanting to do your rehab,” Troy said. “And you feel like you’re wasting a little bit of time.”

Often, Garrigues said the athletes he encounters have a mindset that through mental fortitude and grit alone, they can expedite their recovery process.

“There are biological processes that take what they take,” Garrigues said. “And you have to have some patience for it.”

Repeated experience with these processes has brought patience, Montoya said.

“I’m having to really calm my mind and everything inside my body while on the wait and understanding, ‘OK, you have to heal,’” Montoya said. “Usually as an athlete, you don’t like being still at all.”

It is in discipline, along with a caring and supportive training staff, that Troy said he has found the patience to allow himself to heal.

“There are those days,” Troy said. “But having the discipline to be able to say, ‘If I want that, I need to do this today, now, and I need to do it as best I can.’”

For Troy, he said this means sticking to his throwing program — an eight-tonine-month plan that eases him back into throwing by incrementally increasing the distance and power that he throws.

“There are days when it feels like I never got surgery, and I feel brand new, and I feel like I can just throw at 100 miles an hour,” Troy said. “Even though you want to just go throw as hard as you can, just trust the process and stay at your 75-80% clip.”

Montoya said she can apply these lessons to the court, as she plans to play for the Waves in her senior year.

“As a point guard, it’s really important to be calm and still,” Montoya said. “You bring the ball up the court, and it’s chaotic. People are face guarding you, or one of your teammates is getting doubled [teamed] or you’re getting doubled [teamed], and everybody’s now tense, so let’s bring up the ball, remaining calm.”

Troy, who is only at the start of his athletic career, said he hopes to come into a more leadership-oriented position in the future. His primary goal, however, remains performance-based.

“Goal No. 1 of all baseball players is to be a starting pitcher in the rotation,” Troy said. “That’s my goal. I want that for myself.”

Much of her mindset surrounding failure, Montoya said, is a result of her overcoming her injuries.

“Do I want to manifest that? Absolutely not,” Montoya said. “But I’m not allergic to the sweat and the hard work that comes with failing.”

Troy said even prior to his injury, his favorite thing about baseball is that the sport is riddled with small challenges waiting for athletes to overcome them.

“Baseball is a game of failure,” Troy said. “If you get three hits out of 10 at bats, you go down as a Hall of Famer.”

words by Alec Matulka photos by Lucian Himes design by Haley Hoidal art by Whitney Powell

saw “Puss in Boots: The Last Wish” at a movie theater in my hometown Dec. 31. I watched my ferocious feline champion dance across rooftops, slash through steel and drink copious quantities of cream. As he pranced across his vibrantly animated landscape toward the coveted Wishing

Star, my heart pranced with him. For 100 minutes, I was animated

When I returned to Pepperdine for the spring semester, all I wanted to talk about was animated films. Fortunately, I found a few people, like Phillip Young, senior Integrated Marketing Communication major, who were equally animated.

“There’s a lot of beauty that can be found there that you can’t see in a normal [live-action] movie,” Young said.

Part of why “Puss in Boots: The Last Wish” garnered such acclaim from its viewers — 95% on Rotten Tomatoes, 7.9/10 on IMDb and 4.8/5 on Vudu — is its animation style, according to Vox. Since 2017’s non-photorealistic “Spiderman: Into the Spiderverse” became the highest-grossing movie in Sony Pictures Animation’s history,

according to Statista, audiences and studios have rethought their expectations for animation styles in feature films.

Junior Screen Arts major Dawson Storrs said for him, part of the appeal of animated films — and part of their timelessness — comes from their stylistic qualities.

“In live-action films, you have a lot of different decisions to make — lens choice, lighting, stuff like that,” Storrs said. “But what I like about animation is that all of that kind of goes out the window in favor of an actual art style.”

How animation began

Michael Stock, professor of Film and English, teaches Film 421: History of Animation Innovation. The class begins with the early 20th century and dances through the technological advances of the animation industry through the decades.

“In the beginning, cinema wasn’t about narrative,” Stock said. “It was really about spectacle and about special effects, and that’s kind of where animation comes in.”

The earliest uses of animation, Stock said, appeared in live-action films. Stock gave the example of framed narratives in live-action films, such as dream sequences, which directors would animate to indicate their difference from the overarching story.

Stock said his class traces the effects of innovation and studio commercialization on the animation industry.

“It’s a parallel history of film,” Stock said. “People who are doing animated films are not doing live-action films; they’re pretty separate.”

Animated television programming, Stock said, has played a vital role in the

“There’s a lot of beauty that can be found there that you can’t see in a normal [live-action] movie.”

hillip Young junior ‘24

industry’s development. Stock said shows like “The Simpsons,” a front-runner in the Contemporary Golden Age of American television, propelled the industry to new heights and illustrated an increasing desire for animated content among all demographics — not just children.

“We’ve come such a long way from, ‘Animation is for kids,’” Stock said.

Similar to how Disney is revisiting movies like “The Little Mermaid” in live action, Stock said Marvel could remake some of their most memorable characters in animation.

“It seems like money just waiting to be made, to me,” Stock said.

Stock’s love for animation, however, does stem from his childhood. Stock said

he grew up on a farm in Nebraska, which meant his televised entertainment options were relatively limited. Saturday morning cartoons — Warner Brother productions like Bugs Bunny and Wile E. Coyote — hold a special place in his heart.

“These wondrous windows of time with network programming, like Saturday mornings, meant so much to me,” Stock said.

In their 1981 book “The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation,” animators Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston codified 12 principles of animation, according to a Lesley University article. These principles — squash and stretch, anticipation, staging, straight-ahead action and pose-topose, follow through and overlapping action, slow in and slow out, arc, secondary action, timing, exaggeration, solid drawing, and appeal — serve as a guide for animators to this day.

Kate Parsons, professor of digital art, teaches a class on these very principles. Parsons said her course Art 420: Animation delves into the nuances of animated style, all the way back to its humble roots.

“We start with flipbooks, like we’re literally making physical flipbooks, and then we end with XR [Extended Reality],” Parsons said.

As an artist, Parsons said she often starts with style and lets the story flow from there. She recognizes, however, that many others need to begin with a story — either for creative or financial reasons. Many studios work with large budgets for animated films, which leads to them being relatively risk-averse in their stylistic pursuits, according to Vox.

Whether one begins with style or story, Parsons said the two facets need to intentionally and effectively intertwine.

“A lot of it comes down to timing and telling a story in a way that is able to bring in the right comedic notes or the right dramatic notes,” Parsons said. “The style should support that.”

Animation revolves around a scientific concept known as “persistence of vision,” Parsons said. Human eyes and brains can only hold on to an image for approximately 1/16 of a second, according to Studiobinder. When animators replace one still image with another within this time period, they create an illusion of continuity for the viewer.

The life and magic of animated films come from this illusion, Parsons said.

“It’s so fun to fool our brains,” Parsons

“It’s so fun to fool our brains. Film and animation and all this stuff physically rely on us being able to trick ourselves.”

ate Parsons digital art professor

said. “Film and animation and all this stuff physically rely on us being able to trick ourselves.”

Parsons said one of the first animated films she remembers watching was “The Last Unicorn,” a 1982 film based on a Peter S. Beagle novel of the same name. Parsons said she had the opportunity to meet Beagle at her first ever Comic-Con in her mid-20s. She brought a DVD of “The Last Unicorn” for him to sign.

“I started crying while he was signing it,” Parsons said. “I’m like this adult woman standing there crying at Comic-Con as he’s signing my favorite childhood film.”

Parsons, Stock, Young and Storrs all said animation has a certain timeless quality, although they disagreed somewhat on the extent of its timelessness. For instance, Young said even though he enjoys rewatching the animated films from his childhood, the animation occasionally makes him cringe compared to what he sees today.

“I’ve gone back and watched the original ‘Toy Story’ or the original ‘Monsters Inc.,’ and they’re still great movies, but they look bad comparatively,” Young said.

Even when technological innovations age out the shock-and-awe factor of older animation styles, Stock said he still sees value in these classics.

“I would like to think for people who grew up with that, seeing some of this old cel animation can be pretty astounding because no one in the U.S. is doing that now,” Stock said. “So, it can actually feel fresh and exciting.”

That’s not to say the love affair with animation is universal — people still attach a stigma to animation as a medium, according to The Artifice. People may assume, for instance, animation is just for children or that its focus on visuals masks an underdeveloped or lackluster narrative.

Storrs said he dislikes when viewers use animation as a scapegoat for poorly written material, echoing Parson’s sentiment that story often comes first.

“Whether you’re watching live action, whether you’re watching an animated series or anything, it’s not because it’s animated that it’s not good,” Storrs said. “It’s because it’s written poorly.”

From his personal experience, Storrs said he didn’t just grow up watching animated films — they grew up with him.

“The meaning of animated films changes from age to age in a way that live action never will,” Storrs said.

‘24

“The meaning of animated films changes from age to age in a way that live action never will.”

awson Storrs

junior

words by Jackie Lopez

words by Jackie Lopez

or senior Samantha Proctor, music naturally lives within her. Being a musician is what she said she feels

From age 5, Proctor said she has been singing, writing original songs and playing piano. With a music-oriented family, Proctor said they encouraged her to pursue music as much as she could.

“I’ve never felt more passionate about something in my entire life,” said Proctor, a Screen Arts major. “Something my mom always tells me is, ‘Sam, the thing that’s going to differentiate you is how much you want it.’ And I just know innately that I want it more than anyone else, which is a

Senior Anna Kearle, one of Proctor’s best friends and roommate, said she has known Proctor since the beginning of their first year at Pepperdine. As one of Proctor’s biggest supporters and fans, Kearle described Proctor as joyous, bright and magical.

“She’s like King Midas — anything she touches is gold,” Kearle said. “Anything you’re doing with her will just be golden, and so people need to remember her name because it’s gonna be huge one day.”

With inspirations such as Amy Winehouse, Nina Simone, Bil-

lie Holiday, Olivia Dean, Lorde and Miley Cyrus, Proctor described her style as contemporary jazz-pop. Like her idols, Proctor said she aspires to make songs that are relatable to a wide audience.

“It’s a very vulnerable process to sit down with yourself and accept how you’re feeling and put it on paper,” Proctor said. “And then it’s an even scarier thing to share that with the entire world. So the process is terrifying but very rewarding.”

When Proctor first came to Pepperdine in 2019, she said she struggled with her mental health, making it difficult to express herself through music. During virtual classes in spring 2020, Proctor said she took steps to manage her anxiety and felt renewed when she returned to Malibu for in-person instruction.

“I truly started to accept myself and grow in my confidence and stand in my competence more and in my artistry and who I am as a person,” Proctor said. “That was completely life-changing for me. And so when we came back junior year, I came back with this whole new perspective.”

With a newfound confidence in her music, Proctor released “Crime Spree” — a single encompassing the themes of empowerment and owning oneself — in December. The single is part of her Extended Play (EP), “Hotel June,” which she plans to release this summer.

“I really try to go for this nostalgic vintage feel, and that’s really what I want to capture in this as well,” Proctor said. “I’m planning on it being like four or five songs, not too long, but I want to just kind of solidify something that can lead the way toward something bigger.”

When Proctor performs at open mics and bars, Kearle said she has a powerful presence and shines onstage.

“I really get into it and own it and own my stage presence, which is really cool,” Proctor said. “Once you get over the

initial fear, you feel invincible, and then there’s no better feeling than stepping off and knowing that you owned your moment when you were up there.”

With a determined spirit, Kearle said Proctor puts her all into everything she does and creates. Behind it all, Proctor said her friends and family are the support system that encourages her in her music.

“I’m so lucky to be surrounded by peo ple who are so supportive and who don’t doubt me even when I’m doubting myself — I think that’s a super important thing,” Proctor said.

An aha moment is when one experiences a sudden realization, inspiration or insight.

My aha moment for writing this article goes like this.

I was sitting in my Art Fundamentals class at the beginning of last semester. My professor, Christina Mesiti, asked our class to pinpoint a moment in time in which our experience with art — fine art, music, dance, writing, etc. — changed the way we viewed art and our lives.

I thought to myself, “This would be an

interesting question to pose to the Pepperdine community.”

Flash forward a semester later, and my idea for this article is coming to fruition.

Art has always drawn Mesiti in. Studying art throughout high school and art school gave her the opportunity to explore her creativity across different mediums, she said.

As a sculptor, Mesiti said sculpting provides her a freedom she never felt from mediums like drawing and painting. In sculpting, the materials drive the content of her work — something that once sparked fear in her but she now treasures.

“The thing that scared me was having

to come up with my own problems,” Mesiti said. “That was why I thought fine art was really compelling because nobody was giving you the assignment to fulfill. It was like, ‘What do you want to make?’ It was sort of complete freedom.”

A moment in Mesiti’s life she said changed the way she approached her art making was when her father died in May 2021.

“The limited amount of time you have here — that changed what I cared about, what was meaningful,” Mesiti said. “Like, ‘How did I want to spend my time?’”

Through this, Mesiti said she realized she wanted to explore taking risks to create more meaningful art.

Mesiti said the unconfined and spontaneous nature of art is what drives her.

“The artwork that I see reminds me that I can make any decision I want to make and I can do whatever I want,” Mesiti said. “It’s constantly reenergizing of [my] agency and freedom.”

Senior Music major Michael Gullo said music’s ability to express emotion is his motivation to pursue a career in classical guitar.

Gullo said his father gifted him an acoustic guitar for Christmas when he was around 9 years old, sparking his musical journey.

“He said, ‘Once you learn classical, you can learn any style,’” Gullo said. “I ended up falling in love with the classical style even more and it eventually became my passion.”

Gullo said telling stories through his music allows him to connect with his audience.

“It’s [performing] entirely about the audience,” Gullo said. “It’s about them, not yourself.”

However, Gullo said there was one moment specifically that strengthened

this feeling for him. It was during his senior recital last spring when he performed “Cavatina” by Stanley Myers — a piece he dedicated to his late grandmother.

“Whenever I play it, I think of her,” Gullo said. “I knew the audience felt what I felt and that we were kind of one.”

Moments like this push Gullo to continue showcasing vulnerability — something he said he struggles with offstage.

“It really gives me that emotional release I can’t really do normally,” Gullo said. “It’s almost like a therapy.”

Holly Jackson, junior Theatre Arts and Screen Arts double major, said she has always loved the arts — whether it was singing, dancing or acting, she was doing it. Her passion for performing stems from her love for music; her love for music, she said, comes from her great, great-grandmother who was a piano teacher.

She said she didn’t truly understand what a musical was until her mom showed her “Mamma Mia!” — a jukebox musical set in Greece that tells the story of a bride in search of her biological father through an ABBA-filled soundtrack. Jackson said this was her aha moment.

“I saw Meryl Streep up there, and I said, ‘That, that’s what I want to do,’” Jackson said. “I knew that I wanted to perform.”

What stood out to her about “Mam-

“If you have a passion, follow it. Everybody has a calling for something, and if you have that feeling, please chase it.”

Michael Gullo senior ‘23pictured above cast of Pepperdine’s production of“Mamma Mia!” photo courtesy of Holly Jackson pictured Lorenzo Mars photo courtesy of Lorenzo Mars

ma Mia!” was it told a story of an unconventional family and the power of love through song and dance.

It was in Jackson’s sophomore year when she played Tanya — the rich best friend of the lead character, Donna Sheridan — in the University’s production of “Mamma Mia!”

“It was so amazing because not only am I doing a show that I love, but I know that I’m doing a show that they [the audience] love[s],” Jackson said.

It was after her performance in the musical that Jackson said she felt empowered by and confident in her capabilities as a performer. She said she loves that her craft challenges her and consistently pushes her boundaries.

Storytelling is a powerful tool for artists to express themselves through their craft.

Sophomore Screen Arts major Lorenzo Mars’ passion for storytelling is what led him to pursue a future career in screenwriting.

From creating stories to go along with his Lego sets, to acting as a Greek hero

while playing with toy swords, to now, writing scripts for short films, storytelling has remained one of Mars’ greatest loves.

But Mars said working in the film industry never used to be in the picture.

“I’d finished my junior year [of high school] and still had absolutely no clue what I was going to do,” Mars said.

It wasn’t until the world was on lockdown during COVID-19 that Mars said he had his aha moment.

With nothing to do during this era, Mars turned to reading books and watching movies. It was then that Mars said he thought to himself, “Wow, it would be really cool to work on movies.”

Throughout summer 2022, Mars said he challenged himself to write a few short scripts. After a month of summer and no progress in achieving his goal, Mars decided to sit down, put a pen to paper and write whatever came to his mind.

“[I] was in a flow state, where you sit there and you’re like, ‘Oh, wow. I’m doing this,’” Mars said. “I finished it and it wasn’t perfectly polished but I was like, ‘Wow, that felt so good.’”

Two hours later, Mars said he started working on another script. He said with

every script he wrote, the quality of his writing improved and his confidence grew.

To Mars, putting effort into creating a story and building a world around it felt good, and he said it was a feeling he wanted to chase.

“That was a big moment where I was like, ‘Writing is what I should do, what I want to do because it feels this good,’” Mars said. “If it feels this good, if I’m passionate about it, then that’s the most important part.”