THE BULL THE BULL

SUBCULTURE

FALLWINTER

FALLWINTER

Thank you for picking up The Bull magazine, a supplement to the Roundup newspaper. The stories within these 36 pages do not define any specific culture, but highlight a few of the diverse personalities that make up Los Angeles. Being an Angeleno is a culture in itself, so I chose the concept of Subculture to allow the chunky nuggets in the melting pot of this city to shine.

There is no longer a mainstream, and what you see is not necessarily what you get. Being an L.A. native for the past 22 years has allowed me to explore the city and absorb everything the area has to offer. The faces range from a 91-year-old Holocaust survivor, to a 28-year-old My Little Pony enthusiast, to a couple living on the streets as part of the city’s increasing homeless population.

It has been a pleasure to work with the writers and photographers enrolled in the Media Arts Department. The success of this magazine is due to the long hours and dedication provided by the staff.

Thanks to a special group of people that gave me the support I needed. The stories and photos would not have happened if it wasn’t for Lynn Levitt’s tireless efforts. For all computer related issues, Roundup EIC Raymond Garcia was on call. And Calvin Alagot’s design skills brought everything together.

Finally, to the retiring Julie Bailey, who kept the staff calm during times of crisis, the department will never forget you.

Stay weird, L.A.

STORIES OF STRENGTH HOMELESS IN L.A.

REACHING GREAT HEIGHTS

BUILDING BETTER BODIES SIGNS OF PRIDE

THE NATURAL CHOICE

MANGA MANIA

THE MAN BEHIND THE MACHINE

Story and photos by Lynn Levitt

Asilver haired 91-yearold gentleman enters the conference room at the Los Angeles Jewish Home in Reseda. He walks, bit by bit with a cane, not because of an injury, but because age is creeping up on him.

He acknowledges each person, his ice blue eyes devoid of emotion. The window to his soul hides a story.

“I am not a hero. I am just a Holocaust survivor,” Ernest Braunstein says. Braunstein wants to share his story for his daughter, Gilda Evans, and his three grandchildren.

“I want to know everything about my father,” Evans says. “It is important my family and I have a record of him and the part he played in history.”

At least 1.2 million children were massacred during the Jewish Holocaust, and 9 million adults, according to the Anti-Defamation League’s web archive. Braunstein was neither a child nor adult. He was 17.

After moving to Hungary with his family, Braunstein began his first year of college. Walking down the road, Hungarian and German soldiers accosted him.

“They pulled me by a door. I had to put my pants down. They were looking if I were a Jew or not,” Braunstein says. “When they find out I am a Jew, they put a Star of David on my front and back.”

He was then told he would get a letter to report to a labor camp. Not understanding what this meant, he ignored the letter. A month later, on the way to school, he was

captured by soldiers and taken to Bor Labor Camp in former Yugoslavia.

Braunstein takes a sip of water before continuing. There is little movement in his chair. He has limited use of his hands and arms when he speaks because of what he has gone through.

After Bor, the Russians began to overrun the first of the major concentration camps. By 1944, SS authorities did not want prisoners to fall into enemy hands alive to tell their stories to Allied and Soviet liberators.

The Nazis at Bor evacuated the prisoners for a five-month walk to Germany. Upon arrival, Braunstein and others were packed in trains like cattle and taken to the concentration camp Auschwitz. Of the 15,000 Jews who left Bor, only 2,000 arrived, according to the Holocaust Museum, Los Angeles.

Braunstein had survived a Death March. Fatigue, disease and hunger were minor compared to the Nazi abuse. If a few Jews were killed it meant nothing.

According to the Jewish Virtual Library, there were 59 different marches from Nazi concentration camps.

Braunstein recalls that some Jews would step to the side of the road and put their heads between their knees. This was a sign to the Nazis to shoot them.

“I never looked,” Braunstein says. “I just vowed I would never be one of those who asked to die, no matter what they forced me to do.“

Passing through villages, crowded together as if they were herds of animals, people put out food. No one dared reach

for it for fear of being shot.

“The people that could not keep up, fell to the back and got shot,” Braunstein says. Mastering seven languages, knowing when to volunteer his services, and pure luck, kept Braunstein alive, he says.

During the march Braunstein says the group stopped at a brick factory in what was formally known as Cservenka, Yugoslavia. They were told many volunteers were needed to dig a big ditch for the war effort. Braunstein was the first to volunteer. Any situation could be a change for the better or a means to escape.

“When it got dark, we were told the digging would continue, but I stayed inside,” Braunstein says. “ Then I heard machine gun fire. I climbed to where I could see. Hundreds and hundreds of my fellow prisoners were being slaughtered in the ditch I helped dig.”

Once he arrived at Auschwitz, event after event took place where Braunstein said he found himself barely escaping or coming up with a brazenness no one else could muster.

No one was aware of the atrocities going on around them. They were dealing with the basic instinct to survive. Food was scarce or non-existent. Clothing was not to be had and some wore nothing. There was a constant stench in the air, but the position of the buildings blocked any visual reference. It was the smell of death.

It was shower day. Braunstein says he and one other man were led to a large structure on the other side of the camp. Their job was to hand out soap and a towel

‘‘I am not a hero. I am just a Holocaust survivor.

Ernest Braunstein Survivor

to each entering the structure. Neither Braunstein nor the other man realized no one was exiting. They had been sending their fellow prisoners to death in a huge gas chamber.

“I hid out the next day and did not go back,” Braunstein says. “I survived again.”

Braunstein found he was to be transferred to the Birkenau concentration camp. There he was paid with cigarettes to work in an airplane factory. He traded these cigarettes for food with the guards to keep up his strength.

“After the war ended, I stayed on for a while at the former Bergen-Belsen concentration camp,” Braunstein says. “I was the police chief there and I would help the people to get back to their homes.”

Braunstein became a member of a group who would seek out and capture former Nazis and “eventually” turn them over to

local authorities after beating them severely.

“Only one man died from one kick too many,” he says. “But it was not my kick.”

Working his way across Germany, Romania and the Atlantic Ocean, Braunstein made it to Ellis Island.

“It was a Friday and the offices were already closed. I would have to be able to make due until Monday and I did not have any money to eat,” Braunstein says. “A man saw me standing, looking through the restaurant window, and gave me money for food.”

Little did Braunstein know he would run into the man 10 years later and be able to reciprocate by picking up the tab for the man’s meal at a local diner.

Lacking most of the documentation to enter The Untied States, Braunstein showed a picture of himself playing soccer as a young man and convinced authorities he

was a world class player.

“That seemed to be good enough for them,” he says. “I ended up in California.”

Sitting in a conference room at the Los Angles Jewish Home, Braunstein’s face shows fatigue. His daughter indicates he has had enough. Braunstein has one more thing to say.

“The memories can be deep and painful to recall, yet I believe we must not forget what happened. In passing these stories on to my daughter and grandchildren, what I wish them to learn and share is not the horror, but the pride they should take in their heritage and the lesson, we must never give up striving for what we believe in, no matter the odds.”

The dark wide open eyes of Braunstein’s youngest grandson Loren makes contact with his mother, and says matter-of-factly “He’s my role model.”

Story by Genna GoldWake up on the street, pack up all belongings, bathe in a public bathroom sink, attempt to find something to eat; for more than 50,000 homeless Los Angeles residents, these tasks make up a typical morning. For Ally and Eddie Posyananda, this morning routine is just one of the many reminders they are using as fuel to get them off the streets and back into a home. The couple has become part of what is considered “the homeless capital of the United States,” according to April Lindh, community relations coordinator at the San Fernando Valley Rescue Mission.

This is an all too common occurrence, with the amount of the city’s homeless population increasing 15 percent, from about 50,000 in 2011 to more than 58,000 in 2013, according to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (LAHSA).

‘‘ If you talk to anyone down here and they blame anybody else for their situation, they haven’t learned a thing.

Mike Adams Skid Row residentMike Adams, 54, a resident of Skid Row in Los Angeles, plans to leave within the month. Once a truck driver, he says he hit rock bottom, and has since re-earned his license with plans to get back on the road. Photo: Genna Gold Sitting with 93-year-old Bella Roos, Ernest Braunstein is considered to be quite the ladies’ man by the nurses at the Los Angeles Jewish Home in Reseda.

Ally and Eddie have been together for 20 years, despite dealing with illness, becoming homeless and various other hardships. Through it all, they say their loyalty to each other and positive outlook is what keeps them going.

How did you end up on the street?

Ally: We lost our apartment about two months ago because Eddie got laid off and my job was crap. I made hardly any money selling pharmaceuticals. We had a sister and mother who lived with us, which is the reason we’re on the street pretty much, because they wouldn’t help us. They were just sucking us dry. They moved in with somebody else in the South Bay. We can’t care. We just can’t help them anymore. We helped them until it helped us into the ground. We didn’t even live alone a year until his mother moved in with us. Did you ever have a job?

Eddie: I was a mailroom guy at a collection agency called Grant & Weber, but my position was dissolved. My duties were file management. I helped out with data processing and IT. I was also a machinist at one time, but I had to quit that because of my health. My lungs had partially collapsed because of the environment I had to work in. That’s when I got into office work.

Ally: I was a nanny for a long time, but there are very few nanny jobs out here. Most of them want you to drive and I can’t drive anymore because I lost my license because of a ticket.

How do you use the money from General Relief* you receive?

Ally: They gave us about $500 the first time, because that was two months worth. Right now we don’t have any money at all, so I’m kinda freaking out because we have no money for food and still have four days left until we receive anything. How are you going to deal with that?

Ally: We’re going to go steal.

Eddie: When it comes down to it, we do what we have to.

Ally: We have like two or three dollars left on our food stamp card, so we are going to go tomorrow and get something for a few bucks at the Dollar Tree, and steal the rest. What else can we do? We can’t starve. What did you do when you finally received the $500 from General Relief?

Ally: We have a storage unit we keep all of our stuff in, so we had to go pay that off because it was due, but then we just went and ate so much food. We went through that money quick. We bought some drugs and some tequila and got our drunk on. What are you doing to get off the streets?

Eddie: I’ve been applying for jobs, but no one has called me back because they’re looking for an address. When I give my mailing address, which is the social service office, they move on to the next application. Some day somebody will give me a job; I’m going to keep trying. Some people that I’ve seen don’t really try to do anything, and it’s easy to get stuck; but we’re not giving up.

It’s not like we don’t work; we’ve always worked.

Ally: He has never been out of work this long, ever in his life. We were always part of the normal working society, and we will be again, I know it. I’m not staying here forever, hell no. We just keep going everyday. Why don’t you stay in a shelter?

Ally: I called when I first found out we were going to be homeless, and they only had one bed. A lot of them will separate the men and the women, and we want to stay together. I’m not going to be separated from my husband, so forget it. It’s hard enough on the street, much less being separated. I would never go for that. He’s my rock.

Eddie: They think separating the men and the women will make it safer, but it’s not very safe there anyways. Has your relationship been effected by everything you’re going through?

Ally: It is stressful, and I tell him that I hate him at least once a day. I don’t mean it. I just tell him that. He’s really my rock.

Eddie: Whatever gets her by. I just take it. Anything to keep her from crying; sometimes she breaks down.

Ally: We have our ups and downs, but this is just another thing we are going to get through together.

Have you been treated differently since living on the street?

Ally: A lot of people just don’t care. We’re just people. There has been a couple of times over by the Salvation Army where someone

would come up to me, but they’re usually drunk and I just tell them to leave us alone. How long do you see yourself being homeless?

Ally: We are hopefully going to hook up with my friend Jessica to get off the streets. If not, then I don’t know.

Eddie: I’ll give it three months.

Ally: Three months?!

Eddie: Unfortunately, we’ve realized we can’t rely on other people, so we can’t be too sure.

Ally: I’m not going to be homeless forever. I just can’t and won’t. I want out of here. What do you miss most about having a place to stay?

Eddie: We are new to this, so everything is really bad. I really miss showers and having a place to go back to, an actual bed to sleep in. But my true motivation is to not have to push this damn cart around anymore. Constantly packing up and setting up is really tiring.

Ally: I’m just always so damn bored. If we were home we’d at least have the TV on. I really miss my show General Hospital I also miss being able to cook.

How has living on the streets affected you emotionally?

Ally: When we were first homeless, I was very angry. I didn’t want to be here. The first week I just cried and cried and cried. I don’t know how I got over it. I’m just too naturally up to remain down for too long.

Ally and Eddy Posyananda at Delano Park in Van Nuys. Ally and Eddy live in the park and refuse to stay at a shelter to protect each other. Photo: Lynn LevittThere is a societal expectation of what we are supposed to look like and what is “normal.” But what if, since before birth, a person’s appearance has been genetically set? Dwarfism is an inherited genetic deviation. This gene can cause a person to be of short stature with shorter limbs. One in every 10,000 births will be diagnosed with a type of dwarfism, according to Leslie Vanderpool, chapter 12 president for the Little People of America (LPA).

Emelyne Batugo is a 19-year-old Los Angeles Pierce College student who was born with a type of dwarfism called achondroplasia. She is 4 feet 3 inches tall.

Emelyne’s parents had no idea their

daughter would be born different. “What was crazy is that when my wife was pregnant we ate at a Chinese place and received a fortune cookie,” says Edwin Batugo, Emelyne’s father. “The fortune said: ‘A small person will soon enter your life.’ At first, we just thought it meant that it was because we were going to have a child, but then I remembered and looked back at the fortune when I found out my daughter was a little person.”

The first few years of Emelyne’s life

“It was a surprise,” Edwin says. ”The only difference was my daughter is a little person, and if I were to compare her with

my first child, Emmie started walking a little later. But the doctor said that in her condition Emmie was a fast baby and learned to walk sooner than other dwarfism babies.”

Batugo is working toward a degree in animal science, with hopes of becoming a veterinarian.

Batugo’s childhood was not easy. At the age of 4, she had already become aware of her short stature.

“At first I didn’t like it,” Emelyne says. “I used to hate myself and would cry sometimes, but that was because of the bullying. Then I started going to this thing called LPA. It’s like a convention where there are a lot of other little people, and they helped me get over it.”

Emelyne attended Little People of America from age 2 until she turned 10.

Little People of America is an organization created for the betterment of little people. It was started by actor Billy Barty in 1957. It is used as a support group for new families who have a child with a type of dwarfism.

“In the beginning I felt embarrassed to go and I was really shy,” recalls Emelyne, who says she experienced a lot of bullying in elementary school. “I wanted to go back, but in middle school and high school the people were so nice, so I changed my mind. I felt comfortable. I recently started going back to LPA in July because there was a convention in San Diego. That was pretty cool.”

As a chapter president, Vanderpool, 48, connects families going through the same situations.

Vanderpool gets parents involved with the organization and puts them in direct contact with other families going through the same thing. Vanderpool was born with a rare type of dwarfism called acromesomelic dysplasia.

“My type of short stature is recessive so both my parents had to have the same gene,” Vanderpool says.

Standing 3 feet 6 inches, Vanderpool says LPA has helped her through different

like being incognito and just being yourself without being on show or onstage all the time. Being a little person is like being famous, except without all the money.”

Batugo lives a fairly normal life, just from a different perspective. She is able to drive to school with her customized car, which has extension pedals.

“The only thing we added was a stool. We wanted to treat her normal and have her be independent and learn to do things on her own,’’ Edwin says.

“Whenever some things were too high even using a stool, instead of asking us for help, she would think of a way to bring down whatever she needed, whether it was climbing or using a stick or something long to bring it down.”

“I feel like I’m like anyone else,” Emelyne says. “ I always go by the quote, ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover,’ because you don’t really know a person unless to get to know them. I feel like people should get to know me. I’m just like you. I just look a little different, but I’m also a person. I am a human being.”

For Emelyne, her social life isn’t affected by her short stature. If anything, it gives her more motivation to achieve her aspirations.

periods in her life.

“LPA was a great thing for me,” Vanderpool says. “It gave me that social life that I didn’t have. When I was young and first getting into it, I didn’t want anything to do with LPA because I looked at them and thought that I didn’t look like that and that wasn’t me. Going through middle school and high school was tough, but in college at Seattle Pacific University, I had a great time. I got away from LPA because I was just so into my life and what I was doing.”

Vanderpool eventually returned to LPA, where she met her husband. They have two children, both with a type of dwarfism known as pseudoachondroplasia.

Vanderpool says, “It’s nice being around other little people at the events we host. It’s

“My goal is to prove everyone wrong. Just because I have a disability doesn’t mean I won’t be able to do certain things. I can do it,” Emelyne says. Some people discriminate by saying that because I am short I won’t be able to become a veterinarian. But being short doesn’t have anything to do with anything.”

Emelyne’s views on relationships and having children is about the same as any young person.

“I’m currently not dating anyone. I have dated and only dated regular height guys, who have actually been 6 feet or taller,” Emelyne says. “I have a thing for tall guys.”

Emelyne plans on having four or five children.

“I don’t care if my children are born small, average or both, just as long as they are healthy,” she says.

My goal is to prove everyone wrong. Just because I have a disability doesn’t mean I won’t be able to do certain things.

Emelyne Batugo Animal sciencemajor Emelyne Batugo, 19, said her parents never treated her differently because of her height. She is the only little person in her family, the result of a spontaneous mutation within her fourth chromosome.

The steady hum of treadmills fill the Los Angeles Pierce College weight room, broken up by the sharp metal clang of weights and the occasional grunts of those standing in front of the mirrors running along the walls from floor to ceiling. In the sea of machines and bodies, Sean Oliver is easy to spot. His well-defined physique shows under his olive green tank top, his arms bulging, his shoulders broad and strong. Some of the others in the room lifting weights approach him for advice.

“When people ask me how to get big I tell them it’s more discipline than how you work out,” he says. “Yeah, I train like crazy at the gym, but you have to be disciplined.”

Oliver, 28, is a Pierce student, personal trainer, model and bodybuilder. He is the current Mr. Fitness Southern California, but Oliver isn’t concerned only with himself.

Oliver is in his second semester and hopes to transfer and earn his master’s degree in exercise science. In addition to his work as a personal trainer, he runs a company called Size Up Supplements. He wants to be able to help people outside of the gym, so furthering his knowledge of nutrition brought him back to school.

“A lot of times when I go and do special promotions where you talk about nutrition you need to have the degrees and certifications,” Oliver says. “So I have my certifications, but I need my degrees.”

The practice of building muscle and strengthening the body is common in sports, which is initially how Oliver began working out. Once 315 pounds, Oliver went from offensive linemen to wide receiver on Hamilton High School’s football team.

“It was such a mental shift having to go from being slow to understanding your speed and how to get faster,” Oliver says. “It took years to understand how to switch body types, and that kind of pushed me into exercise science.”

William Norton, who teaches in the Pierce College Kinesiology Department and was a football coach, has been at the school for 25 years. Norton teaches weight lifting, which helps students develop a routine to suit them.

“Bodybuilders typically lift heavy, but they do more repetitions than power lifters. Somebody who is lifting to be a shot putter or an offensive or defensive linemen would lift sets of five with heavy weights,” Norton says. “Bodybuilders would lift more like sets of 12-to-15 with heavy weights.”

Bodybuilders work with heavy weights and constantly increase the weight to build muscle. But more than getting bigger, there is a sense of proportion and aesthetics to the training.

“I’d like to be able to talk to people about how to lose weight and utilize the aspects of bodybuilding, because it’s more of an art of how to train your body,” Oliver says. “There’s different ways people train, but everybody

wants to perfect their body, so there’s a lot that deals with body composition.”

Another bodybuilder, Omair Butt, 25, got involved through family connections. He has an uncle and cousins that are bodybuilders at the competitive level in his native Pakistan, and being around them when he was younger is what introduced Butt to bodybuilding. He has been working out since he was 15 years old, but began bodybuilding consistently six years ago. He says working out is the only thing that he looks forward to each day.

“It’s like a drug to me,” Butt says. “When I don’t go to the gym I feel depressed, so it’s like an addiction, or I don’t know what you’d call it. I don’t feel like my day is complete if I don’t work out.”

If for some reason he can’t make it to the gym, he feels uneasy, which is challenging because he is dealing with a few injuries.

“It puts me out of the gym. It takes my depression to a whole other level,” Butt says with a laugh. “I feel like I’m stuck at home and I don’t even feel like eating.”

While Oliver competes, he doesn’t feel driven by a competitive urge. After a knee injury took him off the football field, he began strength training during his recovery and saw another side to competitive sports.

“I love the training aspects of sports, but you have to have a certain kind of mindset when you play football, basketball or baseball,” Oliver says. “There has to be love in it, and if you don’t love it then there’s no

real place in there for you.”

Instead, Oliver focuses on helping others maximize their potential.

“I felt the pain while going through the injury and I just didn’t have a love for it,” he says. “I have more of a love for the art of sculpting the body, and so I just got more into understanding how the body works.”

In addition to his job, school and working out, Oliver will begin training for The Fit Expo in 2015. He’s also gearing up for a bodybuilding competition hosted by Iron Man Magazine and the Jr. National Bodybuilding Championships. He says discipline again will play a major role.

“It’s hard now with going back to school and trying to balance because there is so much discipline that is required to deal with the dieting and all that kind of stuff,” Oliver says. “If you see me in class I have a big container because I’m at school all day, so I have to package all my meals together. It’s trying to be as disciplined as possible.”

I love the training aspects of sports, but you have to have a certain kind of mindset. There has to be love in it, and if you don’t love it, then there’s no real place in there for you.

Sean Oliver BodybuilderSean Oliver, 28, whose physique has earned him titles such as Mr. Physique L.A. and Mr. Fitness Southern California, works out in Woodland Hills.

School for the Deaf, Fremont. She went to Gallaudet University in Washington D.C., the only deaf university in the world. Her parents wanted her to be a teacher, but she chose a different career path, studying communication arts.

After moving to Los Angeles, Hall worked as a teacher’s aid. The real teacher would take time off, so she took over and started teaching. Hall taught at an occupational center, where most of the students are foreign born, and she taught them ASL.

That is when she heard about an opening at Pierce. Hall was inspired to join the school’s faculty because she believed she could help deaf students on campus who need guidance.

Hall teaches ASL 40, Introduction to Deaf Culture and different levels of ASL. She also is responsible for running the Interpreter Education Program.

She faces the same struggles that all teachers do. Most of her daily life outside of school is similar to someone who can hear.

For example, Hall drives to work.

“Deaf people are better drivers than hearing people who are busy worrying what is on the radio,” she says.

The differences come when she needs to interact to people who can hear and don’t

Imagine yourself at a young age, enjoying life. You hear everyday things, from the Sunday morning cartoons to the melodic tunes coming from the radio during drives with your parents.

Then a strange fever makes you weak and sick. You go to the doctor to get shots, hoping for a cure. It gets even worse. Soon, all you hear is nothing.

Ahmed Elembaby is that person. Born in Egypt, 26-year-old Elembaby was a toddler when he lost his hearing.

It was a struggle for his parents because they did not know sign language. Elembaby does not recall the transition to becoming deaf because he was so young. His elementary school teachers taught him a few signs so he could communicate with his parents. The older he got, the more he and his parents learned to sign. Then, Elembaby heard about the cochlear implant. He discussed it with his family and finally decided against it. Instead, he made a choice to remain part of the deaf community.

“Surgeries to hear are being disrespectful

to the deaf culture,” Elembaby says. Now, Elembaby attends Los Angeles Pierce College, which has a renowned program in sign language.

Kristine Hall, who teaches American Sign Language at the school, is here for him and other students, helping them succeed.

Hall was born deaf, as were her parents, and she assumes it is a genetic trait.

She is proud to be deaf and says when her parents found she was born deaf, they were happy.

Hall’s parents worked for the California

know how to sign. She deals with that simply, by asking them to write messages.

At home, her family uses sign language.

Hall’s husband is deaf. Her two children are hearing, but they sign because that was the first language they learned.

When she first gave birth, she recalled

asking the doctor to test if her child could hear. The doctor replied, “Your baby is normal.” She responded, “Are you saying I’m not normal?”

Hall continues to fight the normal stereotype by educating students about the complexities and beauty of her language.

One of Hall’s students is Valentine Feldstedt, an 18-year-old student who can hear. She says she appreciates Hall and the other advisers because they are helpful, and they don’t judge what you know or do not know about the deaf society.

What inspired Feldstedt to take ASL classes was her sixth grade friend who was going to lose her hearing before turning 16. Feldstedt’s friend taught her the alphabet in sign language, and Feldstedt later bought a book to learn even more.

Feldstedt wonders how it feels to be deaf, in part, because she is a singer, but through her ASL studies she has grown to appreciate the richness of the language.

“It’s more like story telling. It’s so theatrical and beautiful,“ Feldstedt says.

Whether it’s Elembaby, who hasn’t heard since his youth, or Feldstedt who learned ASL to better communicate with her friend, Hall and her colleagues strive to enrich the campus through a better understanding of all aspects of the deaf culture.

In today’s society more and more people are adopting an organic lifestyle. Some people believe it is a healthier option and others think the practice helps the environment.

To be called organic, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) requires that the food meets strict standards. The USDA regulates how the food is grown, handled and processed.

“It takes 3-5 years for the land to be considered organic,” says Teal Rocco, coowner of Topanga Fresh Market.

Organic farmers are not allowed to use chemical fertilizers in the soil. They are also banned by the USDA from using genetically

engineered seeds.

“Pesticides can be harmful to humans and wildlife because they contaminate our air, food and water,” says Michelle Basche, an avid organic consumer.

Basche says that the company Monsanto is one of the major producers of genetically modified organisms, known as GMOs.

“They sell a hormone to dairy farmers that increases a cow’s capacity to produce milk. It has been found that cows milk could cause breast or prostate cancer in people who consume it.”

By choosing to go organic, people are helping to lower the amount of chemicals used in food production.

American comic book Saga , by Brian K. Vaughan.

For Nadreau—whose keen eye has earned her spots in numerous student art exhibits—the look of a manga is as important as the story.

“I won’t read or watch something that is not visually or aesthetically pleasing to me,” Nadreau says. Although they have never met, Stewart and Nadreau share the same need to keep improving their art. Both young women are accomplished illustrators, yet their styles stand in stark contrast of one another. Nadreau is known for her eye-catching pieces that blend fantasy and human anatomy. On the flipside, Stewart likes to think of her work as “randomized madness.” The struggle for Stewart is getting what is in her mind on the page. “On any given day I come up with 5-to-10 characters,” Stewart says. “Once I really like a character, then I start my research, and that can take forever.” To elude the stereotypes, Stewart visits local manga haunts, such as Anime Jungle and Kinokuniya, located in Downtown L.A. Spending hours at a time consuming comics, she takes a mental note of the characters she likes and those she doesn’t. These bi-monthly trips are only half of the research. Once a character’s personality and background has been plotted, Stewart creates mock-up sketches. “I spend close to 20-to-40 hours figuring out a character. Sometimes it takes a little longer or a little less,” Stewart says. “Or I’ll scrap a character completely and start from the beginning.”

he blaring cheers of female Japanese pop stars on screen blanket the constant humming chatter inside Anime Jungle. It has just struck noon when scores of fresh-faced youths pack the spacious Downtown Los Angeles shop. Among the ranks—hidden beneath a silken aquamarine wig styled into a

StoryTbob—is Dolores Stewart. Squatting in front of the section of manga comics labeled “A”, she thumbs through a copy of Attack on Titan , by Isayama Hajime. Stewart is dressed in an outfit resembling Vocaloid Hatsune Mikuo, the male variant of Hatsune Miku. Dressing like a fictional character is know as cosplay.

“I like the darker mangas because they show raw human emotion,” Stewart says, as her deep brown eyes scan the page.

“It makes the characters more interesting.” By the light of day, Stewart, 22, attends Los Angeles Pierce College, with aspirations of becoming a mortician. When the late night cram sessions end, Stewart directs her concentration to another obsession—manga.

“I prefer the softer lines and diversity manga offers,” Stewart says.

“American comics have harsher lines and physically exaggerated characters as the norm.”

Change has been slow to stir since manga and anime—Japanese comics and their animated counterpart—first appeared on the radar of American teens back in the 1980s. However, the recent boom in social media has prompted a massive expansion of the Japanese comic style.

Manga artist, on the protesters outside

Last year’s Anime Expo, or “AX”, 61,000 people attended the 2013 Los Angeles,” according to the Society of the Promotion of Japanese Animation. It was the largest North American conference of its kind, until 80,000 people came to the 2014 convention.

Stewart, who has been drawing and creating mangas since she was a pre-teen, learned her likes and dislikes young. She spent many Saturday mornings watching Cardcaptor’s Sakura

Digimon and Pokémon with her sister and three brothers. This early exposure helped Stewart craft her style. Yet, still she believes there is room for improvement. “It’s always me against the manga,” Stewart says. Nadreau would agree, even after her latest art success. “You’re never there . You will never be there, either,” Nadreau says. “That’s the thing about being an artist.”

Since February 2014, Stewart has completed two mangas. These will join the other completed volumes in her library. Though Stewart remains dedicated to her art, she has never sought out a publisher. For her, manga is just a hobby. “If I am published someday, great. If not, it isn’t the end of the world,” she says. “Being a mortician will be work and entertainment enough.”

Some groups see these increasing numbers as a threat. Stewart, who attends AX all four days every summer, has been confronted by members of religious protester groups stationed outside of the Los Angeles Convention Center. She has never had a good experience with them.

“I remember this one woman said, ‘You’re going to hell for what you’re doing,’” Stewart recalls. “She told me it was a sin.”

Regardless of the ridicule, Stewart does not let the critiques of others weigh her down.

“People just don’t understand the manga, anime and cosplay community, and if you don’t understand something you’re going to be afraid of it,” Stewart says.

Professor Robert Wonser of Pierce College would agree. Wonser, who has been teaching since 2008, is a Nintendo fan. In his course Sociology 86, Wonser examines what is the driving force behind a movement’s popularity. Or in the case of anime and manga, the forces working against it.

“People take things out of context. Those who get it, get it,” Wonser says. “However, the people who aren’t part of that group see it as scary and don’t understand it.”

Naomi Nadreau, 20, who studies art at CSUN, faced the same judgment from strangers while attending AX last summer.

“Protesters will just stand there and yell at you,” Nadreau says. “They’ll even shout at you while you’re in your car.”

Despite not being heavily involved in manga and anime communities, Nadreau enjoys reading various light novels and comics from her collection. Her favorites include Chobits , by Clamp, and Mars , by Fuyumi Soryo. The latest edition to her collection is the

“One woman said, ‘You’re going to hell for what you’re doing.”

Dorey Stewart

Anime Expoby Marielle J. Stober Photo by Lynn Levitt Illustrations by Dolores Stewart Aspiring mortician creates her animated alter-ego

There is no way you can miss him. You hear him first. He approaches the parking lot with a growing roar coming from a pristine 1994 Harley Davidson Low Rider. He is not simply a motorcycle driver. He is a biker.

With a fresh mohawk, a sleeve of tattoos, black jeans and boots, he walks around campus with an intimidating and unapproachable look. He puts a twist on his masculinity with earrings, feathers, bracelets and rings.

A symbol that appears to be a swastika, gnarly scars and a dark shade of RayBans that cover his eyes are enough to

make most people stay away, but it is also makes some people wonder who he is. His name is Jose Juan Vasquez, but most people call him Rufio. The 26-yearold former Marine came back from war and found himself inspired by freedom. After a few years of sweat and hard work, he was done with the military and ready to begin his civilian life. The Kansas-born biker, who was raised in Texas, followed his free spirit and thirst for self expression and landed in California.

“My pursuit every day is to enjoy life, because I had it almost taken away from me several times,” he says.

Jose “Rufio” Vasquez, 26, strikes his signature pose on top of his 1994 Harley Davidson Low rider “The War Horse” by one of his favorite views on the Art Hill at Pierce College in Woodland Hills.Used to a lifestyle of brotherhood, it is not surprising that Rufio found comfort in a biker community -a loyal crowd with a strong connection. His style is specific. Black pants hide dirt and oil stains. Combat boots are suited for oily floors and using heavy equipment. A vest with multiple pockets keep important items such as phone, wallet and keys easy to reach.

“The style of the vest, or the cut as we like to call it, really speaks to who you are. You can look at a man’s vest and see where he is coming from, what his personal beliefs are, what kind of attitude he has,” Rufio explains.

“Mine is inappropriate and humorous,” he says with a smile on his face.

Rufio brings attention to himself by wearing a symbol called the “Whirling Log,” which most people confuse as a swastika. Although most people associate the symbol with terror, for Navajo Native Americans and other cultures it is a sacred symbol that represents life, prosperity, success, healing, luck and eternity.

“I don’t see a symbol of hate,” he says. The Whirling Log symbol comes from a Navajo tale of a man who was an outcast from his tribe. Despite the dangers he would face, the man took a risky and long journey down the San Juan River. When he came back, he was seen as a brave man, but it was the knowledge he brought back to the tribe that helped them succeed as a group.

“I’m on this search for knowledge. I’m out into the world on my own river, except it’s asphalt instead of water,” Rufio says.

Rufio believes that looks can be deceiving. Despite his tough exterior, he says that he likes being approached rather than being judged by his appearance.

“I’m all about sharing knowledge and love,” he says. “Ask me some real questions. Get to know me. I’m free. I live in a country where I fought for my rights. I should be

able to dress and look how I want.”

He attributes his rough exterior to the tough love he received from his mother, Sylvia Vasquez.

“She wasn’t necessarily there to pick me up off the ground. She taught me how to pick myself up,” he says.

The Chicano mother of four raised her children to be independent. As a cancer patient, Sylvia wanted them to be self -sufficient if the disease took her life.

“We knew how to take care of ourselves,” says Rufio’s older brother, Rogelio Vasquez. Today, Rufio lives his life day by day. What brought him to Los Angeles is his dream of one day opening a motorcycle museum, which would show the history of motorcycles and bikers.

“There are stories being told over campfires in the middle of nowhere that you will never hear about. And those are the stories I want to bring to light,” Rufio says.” This is not something that I am interested in for the meanwhile. No. It is my life mission to preserve motorcycle history and culture.”

Rufio’s friend Larry “Wizzard” Cook, 56, agrees that a motorcycle museum is needed. He thinks that bikers are a significant part of American history.

“When you go to a motorcycle museum all you see is motorcycles. That’s not the whole thing,” he says. “I want to know who bought it, who rode it. I hope Rufio pulls this off.”

Vasquez plans to transfer to University of California, Berkeley or University of California, Los Angeles.

“I have a 4.0 I’m a hard working individual. I will do what it takes to get me where I want to go,”

Rufio says.

He hopes when people see him around campus they won’t be afraid to say hello.

Rufio says he is not a dangerous criminal like most people assume, and that despite his intimidating look he is an approachable guy full of dreams and goals.

Behind the black curtain of Bar One in the San Fernando Valley that keeps her hidden from the crowd, Lola Chan changes from conservative clothing she wore entering the club to her lacy and seductive costume that will be revealed to the waiting patrons. The sound of anticipation grows as the entertainment is about to begin. The lights dim and the master of ceremonies opens the show. A spotlight shines on her and the now raucous crowd begin their journey into

the seductive art.

Chan, who goes by the stage name of Bettie P’Asian, steps on to the small makeshift stage. She’s wearing a short cut, vivid red beer maiden dress in honor of Oktoberfest. Piece by piece, she removes parts of her costume as the song progresses. The first to go are her long, black satin gloves that stretch to her elbows, slowly rolling them off to the crowd’s joy, followed by nude colored lace stockings. Chan keeps the bar patrons allured by rhythmic gyrations, syncopated

by a mixture of slow and fast movements. Not long after, her main piece of clothing comes off, revealing a tight fitting sequined corset, which she keeps on, keeping everyone on the hook until her next act. There are many forms of burlesque, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as a “literary, dramatic or musical work intended to cause laughter by caricaturing the manner or spirit of serious works.” The early 1900s saw the birth of American Burlesque, which switched the focus toward a more sensual act. It

I’m free. I live in a country where I fought for my rights. I should be able to dress and look how I want.

Jose Juan “Rufio” Vasquez Marine/Biker

A dancer’s modern take on classic burlesqueStory and photos by Mohammad Djauhari

concentrates on the striptease performance by women in venues such as cabarets and speakeasy clubs. Fading in popularity after its 1920s heyday, the lost art of the burlesque striptease gained resurgence during the late ‘90s.

Chan came up with her stage name after being inspired by Bettie Page, the iconic American pin-up model of the 1950s.

“As a little girl, I used to look at her images and copy her poses while playing dress up,” Chan says. “I was so fascinated by her.”

Today, there are few places in the Los Angeles area that provide burlesque events, but Bar One organizes burlesque shows every month.

“I was first approached by the owners,” Chan says. “It was Bettie Page’s birthday, and they were having a Bettie Page pinup

contest, and I happened to be one of the winners.” The owners of the bar expressed interest in having another burlesque show. Chan told them that she was a performer. “That’s how it started, and they liked it, and they’re kind of extending it,” she says.

Bar One Beer and Wine Parlour, located in the Valley Glen area of North Hollywood, hosts the Bettie P’asian revue that showcases American Burlesque, which contrasts the classic version of the art form, along with the contemporary style.

“It was back in the mid ‘90s when burlesque first started to creep up on the scene,” says Arelene Roldan, president of Bar One. “I just fell in love with it and I think it’s a style and an art form that will never die. It’s sexy, it’s funny, it’s very entertaining,” Roldan says.

Chan wasn’t always a burlesque

performer. She earned her acting degree at the California Institute of the Arts.

“It wasn’t until college that I had my first opportunity to perform in a cabaret show, and from there I found that I really enjoyed it,” Chan says.

At the end of the 20th century, the art experienced a resurgence of interest due in large part to Dita Von Teese and other cabaret performers.

Cheers of jubilation erupt after the intermission portion of the Bettie P’Asian revue as Chan jumps from behind the curtain dressed as Chun Li, a character from the popular video game Street Fighter. Her persona strikes a chord inside the mostly male crowd that brings the nostalgic memory of being a young male, filled with thoughts of nude women, sex and playing video games. Every jump, kick

and punch performed by Chan brings whistles and raucous screams of “yeahs.”

“Burlesque is one of those art forms that relies on the audience,” Chan says. “It’s definitely a two-way street; you’re communicating with the audience; you’re playing with the audience, and that’s what I play toward, that kind of energy,” Chan says.

Another important element of any burlesque show that maintains the level of energy is the role of master of ceremonies, played by Tikku Sircar. No stranger to being in front of the crowd, Sircar, who has a background in theater and music, is responsible for adding the element of playful banter with the crowd by witty jokes and humor.

“There’s a couple of things as an MC that I try to do, and I try not to make any sexual references,” Sircar says. “These

performers aren’t sex workers; it’s not a strip club and comments like that have no place and it’s disrespectful.”

Chan holds a similar view.

“Burlesque is ultimately a striptease,” Chan says. “However there is a lot more art and creativity to it. I have a lot of respect for exotic dancers, but with burlesque there’s a lot more time and effort involved to create these elaborate costumes, dances and characters; there’s a preparation that the audience never realizes and sees, but because of that preparation there’s a magic to the show.”

Despite her history of performing on stage, Chan still gets nervous before every performance.

“I get anxious because I don’t want to let anyone down, but once I’m on stage, I completely forget about it and I’m having so much fun,” Chan says.

Chan’s last performance of the night ends as the final notes to the song slowly fade away. She exits the stage and gathers pieces of costume she took off for the crowd. She places them inside the luggage stroller before putting on a dark green sequined dress that allows her to shine and shimmer for the bar’s patrons like an emerald against the lighting.

“This is my first time having a monthly residency show anywhere and I’m really grateful,” Chan says. “Ideally, I would like to start touring the country and possibly the world with burlesque. I would love to travel to different places and meet other performers and perform at other venues, but I want to continue with the Bettie P’Asian revue and make it bigger because it’s a fun and great opportunity to create new material and new acts.”

It’s definitely a two way street; you’re communicating with the audience; you’re playing with the audience, and that’s what I play toward, that kind of energy.

Lola Chan Burlesque Dancer

Stairs lead up from the garage to the main living area of the split level apartment. The color palette in the room is fairly neutral, from the white walls to the beige couch. However, in one corner near the front entrance, colorful shoes sit on display. Red, purple and green sneakers pop among the grey and white. This is Francisco Flores’ home, and the shoes are part of his sneaker collection.

Flores is a sneakerhead, which is defined as a person who collects shoes as a hobby or for financial gain.

Forbes magazine’s contributing writer Matt Powell reported that sports shoe sales in 2013 totaled $22 billion, with the sneakerhead portion making up about 5 percent.

For most sneakerheads, it’s not about the money they can make reselling their shoes. For them, it’s about the passion and the fun they have collecting them.

Flores, a travel agent, is a burgeoning collector who started buying shoes recently, though the interest has been there for years.

“I wanted to become a sneakerhead since I was a little kid, but we couldn’t afford shoes growing up,” Flores says. “Within the last year and a half, I just boomed into a huge sneakerhead, and now it’s like I’ve got to have every single shoe that comes out.”

As a kid watching Michael Jordan, Flores wanted to emulate the sports icon.

“I wanted to fly like Mike,” he says.

Flores isn’t alone. According to Mental Floss magazine, in 1985, Jordan sparked the popularity of a new shoe called Air Jordan I, when he rebelled against then-NBA Commissioner David Stern’s rule of wearing non-regulation shoes on the court. This act inspired many people to copy their hero.

Ron Castro is the buyer for Primitive, an urban wear and shoe store where sneakerheads frequent for the latest “kicks.”

Castro believes the infamous red and black sneakers—along with Nike’s strong marketing campaign—was the beginning of basketball shoes fusing with the sneakerhead culture. Though Converse brand shoes had always been related to basketball, Nike, with Stern’s unwitting help, invigorated the culture surrounding sneakers.

“Jordans permeate cultures,” Castro says. “It turns into a fashion thing where certain people wear Jordans, and you equate that to fashion and to sneakers and not back to him playing basketball necessarily.”

Jordans are just one instance of how sneakerhead culture is an amalgamation of several other types of cultures. Castro says rappers such as Kanye West mix street wear with high fashion clothing.

“It’s this whole image that people are trying to build wearing these sneakers. So that hits that market, and also people who like sneakers in general. It hits different levels. You can’t really pigeonhole that consumer into one specific person,” Castro says.

John Dinh, who considers himself more of a collector rather than a sneakerhead, is representative of the type of person who didn’t get into sneakers because of basketball but still loves the shoes.

For Dinh, it’s always been about the design and functionality of sneakers.

“As a kid I always wanted to be the fastest runner, the highest jumper, so on and so forth. So athletes had a big impact on me buying sneakers originally,” he says. “And then there was one pair that just caught my eye, and since then I have been hooked.”

The shoes that started his love affair were the Air Max ‘90s Infrared, originally released in 1990. Dinh recalls seeing them for the first time and loving the aesthetic.

“It had a very neutral color scheme with this bright splash of vibrant red accents,” he says.

‘‘Over the last 15 years, Dinh has amassed a collection of more than 300 pairs of shoes. Similar to Flores, he’s not only drawn to the aesthetic of the shoes but to the performance as well.

Something he loved about the Air Max ‘90s shoes was a new technological advancement, introduction of an air bubble in the bottom of the shoe, which he says increased comfort and stability.

Castro says one of the major misconceptions about sneakerheads is that they’re needlessly spending money.

“There’s an image of being thuggish and that people are wasting their time, but that’s not true. There’s a huge return on investment,” he says.

Dinh, who works in the financial industry, believes that sneaker collecting isn’t valued in society because people who are not involved in the culture do not understand it.

Dinh compares high-end shoes to precious metals because both can rise in value over time.

Flores believes that if he sold his collection he could probably use the profit for a down payment on a house.

Flores has an 8-year-old son who is turning into a mini-sneakerhead. He says it is hard to justify paying the full retail price for elementary age kids knowing that they will be running around and beating them up. Flores handles his son’s desire to copy his father with patience—and taking it one pair at a time. For Castro, it is common to see multigenerational love for these shoes and he often sees parents bring their kids into the store. He urges people when it comes to collecting to be themselves, regardless of what others may think.

“I encourage them to be different, he says. ‘Like what you like; don’t do it because you think it’s cool. Do it because you genuinely like it.”

I wanted to become a sneakerhead since I was a little kid.Francisco Flores Sneakerhead The Jordan XIII, with its iconic logo on the sole, is one of Francisco Flores’ favorites from his extensive collection. Francisco Flores shows off a selection of his sneakers in his apartment in Woodland Hills.

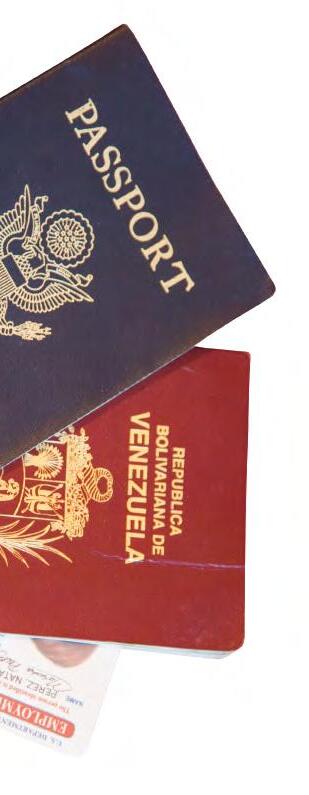

The story is all too frequent. Natasha Perez, Irma and their mother Yrma wanted to leave a country filled with political unrest, hoping to find serenity, the proverbial “gold paved streets” and the freedom of living the American Dream.

Like many of these stories, that path to U.S. citizenship has been filled with trials and tribulations.

Yrma is half-Italian and half-Venezuelan, born in the city of Caracas, Venezuela. When she was 19, she married an American citizen from Manhattan. They lived in New York for 10 years. At that time, American immigration law allowed for citizenship through marriage.

Away from her family and having no real friends, she began missing her home and returned to Venezuela. Her husband followed her and they had two daughters.

Decades later. 29-year-old Irma, the eldest daughter, saw an opportunity to move to America. Her childhood sweetheart planned a move to the United States for school. His parents were paying for a Miami apartment, so expenses would

be minimal. Settled in, Irma in 1994 sought an attorney to obtain U.S. citizenship.

That Christmas season, Natasha and Yrma visited Irma in Miami. Natasha came to the United States with a traveling tour visa. She was not expecting to stay.

When the visit came to an end, Natasha and her mother packed their suitcases, but there would be no flying back to Venezuela. Huge floods had destroyed the Caracas airport. Yrma and Natasha had to bide their time until a flight home was possible.

During the next two months, the sisters visited Irma’s immigration attorney and started the process of obtaining citizenship. As he requested, they provided him with their passports along with legal fees. The airport in Venezuela opened again, but only Yrma returned.

Although Yrma was naturalized by marriage, immigration agreements between the United States and Venezuela forced her to give up American citizenship when she left the country.

Irma and her boyfriend decided to move to California, and Natasha accompanied them.

“I’m interested in music and acting, so

I decided to check out L.A. because that’s where everything happens,” Natasha says. “In Venezuela, my aunt and uncle owned a theater. Like our relations, my sister and I were both bit by the acting bug and appeared in many plays. Our home was always a set. I was always exposed to the camera.”

While packing for California, they sought a progress report from the immigration attorney in Miami. Unable to reach him by phone, they went to his office, discovered it was closed and he was gone. The girls weren’t happy.

“The bastard took all our passports,” Irma says. “We reported them stolen to the police.”

Upon arriving in California, a friend referred the sisters to an immigration attorney named Eli Rich in the San Fernando Valley. Rich plodded through their paperwork and found that the Miami attorney did not file any paperwork. They were not here legally.

He advised them to have their mother write a lengthy letter explaining why she had to give up her American citizenship and detailing why she wanted to come back

to America as a citizen.

Irma was able to change her status from a tourist visa to a working visa. Natasha was not able to change her status, so she was in greater jeopardy of being deported.

Irma found a job as an advertising copywriter. She got a Social Security number and paid taxes. Natasha got a job as a TV weather host. She continued auditioning for acting roles and obtained a Social Security number and paid taxes like her sister.

The women decided to bring their mother back to the United States. Even though they were not sure if the process was going to be successful, they took the risk.

The letter Yrma wrote was submitted, but the fear and worry continued.

Waiting every day for that special phone call, saying, “You are legal” kept Yrma, Irma and Natasha on pins and needles.

“I was scared that they might say no,”

Irma says.

The call came.

The time period that Yrma spent in the United States in the 1970s meant that she could regain her citizenship, and, in turn, it automatically qualified the sisters to be here

legally.

With the journey completed, Yrma, Natasha and Irma started the next chapter of their lives in their new home—free from the strife they experienced in Venezuela. Yrma is single and lives by herself in Santa Monica.

Natasha lives in Brentwood. She plans to keep doing what she loves, acting.

“I grew up learning to love this country, and it only made sense that one day I would live here,” Natasha says. “It’s been a long road, but I’m really happy to be an American.”

Irma, married, now lives in Northern California with her husband and son.

“I’m so thankful that my son didn’t face any hardships like I did. He was born here, so he’s an American,” Irma says. “Being outside the system sucks. People take advantage of you and there’s nothing you can do about it. When I got my passport my friend sang the Star Spangled Banner for me and I cried. It was very emotional, even though I had heard it 1,000 before; this time I felt it inside. Becoming legal was like earning your rights to be a person again.”

Two sisters come to the United States from Venezuela for better opportunitiesIrma (left) and her son Luca Thomas-Fitzgerald (center) visit Auntie Natasha Perez (right). All are now U.S. citizens.

It takes a moment to adjust to Rita Nisan’s heavy accent and soft spoken voice. As an adjunct professor of photography, students quickly learn to understand her, but they don’t really know her.

That’s because she comes off as being shy and isn’t likely to discuss her personal work and accomplishments.

In 1993, Nisan and her husband Shamuel Italiaie fled Iran, after years of persecution for helping Muslims convert to Christianity. Nisan and Italiaie immigrated to the United States with their 9-year-old son, Chris and 2-year-old daughter Stephanie.

Coming to the United States, the family had to leave nearly all of their belongings in Iran. “We had nothing. We had only five

suitcases, but we were happy because we were going to a free country,” Nisan says.

The United States held the promise that the family would be free to worship whichever religion they chose, and their children would have a chance to grow up in a environment free of war and brutality.

Since the fall of the Assyrian Empire around the year 612 B.C., Assyria has not existed as a country of its own. Assyrians, and those living in Armenia, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, have seen a pattern of violence and bloodshed on their homelands. They hide their identities to avoid being singled out by extremists or a government that wants a pure Muslim country.

Nisan’s trouble began in Iran when she was 18 years old. Nisan says she received her diploma in math and physics and was the top

ranked student in high school. She believed in just one year she would be at a good university chasing her dream of becoming an engineer.

But in 1981, an Islamic Revolution occurred, and all universities and high education institutions were closed. According to Nisan, professors and materials that did not reflect the Muslim religion and ideology were removed, and those professors were asked to resign or to leave the country.

After two years, the Iranian universities reopened, and when Nisan took the assessment, she passed. The schools then conducted a religious background check on accepted students.

Nisan said the investigation included a visit to some of her neighbors who were asked if she was a good Muslim. They

revealed her as a Christian. She was refused entrance to the university system.

According to Father George Bet-Rasho, who is the parish priest and core bishop of the St. Mary’s Assyrian Church of the East, “Many times if you are competing for a job or school and you’re not Muslim, you will lose. You’re judged on who you are and what religion you practice, and, of course, in those countries they prefer Muslims.”

After being denied a chance to go to a college, Nisan went to fashion school. She spent several months learning how to make dresses. She then attended an occupational center to get certified as a seamstress.

The director of the fashion school, who was a devout Muslim, told Nisan to put her name down as a reference when re-applying to Tehran University. She was accepted for the photography program in 1985 when she was 22 years old.

“Some people want to be a physician, but they can’t get to that school, so they end up being dressmakers or mechanics instead,” she explains.

Once Nisan passed the second assessment, she started by photographing the Kurdish people in her community because she enjoyed their culture.

Nisan’s passion for Christianity continued to develop as she got involved with teaching Sunday school at her church in Iran. Italiaie helped her as a teacher’s aid, and on Nov. 17, 1988, they were married.

In 1989, after the Gulf War, Kurds were forced into refugee camps after the United States and United Kingdom conducted airstrikes in Iraq.

Nisan began documenting the refugee camps in 1991 to build a portfolio for her bachelor’s degree in photography. Nisan said she was working as a volunteer with The World Relief Organization, which was sending

airplanes with cargo to cities needing help. Many people died while journeying to the refugee camp locations due to rough weather and traveling conditions.

While attending Tehran University, Nisan also began working toward an online bachelor’s degree in theology and Bible study, which she received from Global University in Springfield, Missouri.

While working behind the scenes at the church, Nisan began translating copies of English language Bibles to Farsi, published them, and kept them at her church in limited circulation because they were not allowed by the government to sell the books to Muslims, Nisan says.

While Nisan and Italiaie continued to get involved with the church, they knew it could put their lives at risk.

“Those books change peoples ideas and thoughts,” Nisan says.

In 1993, Nisan gave birth to her son. Five months later, three of Nisan and Italiaie’s best friends, who were pastors from their church, were killed.

“We felt that this circle was getting closer and closer to us,” Nisan says.

Nisan’s fears got worse after she received word that some government officials were questioning church members about them. At that time, the family had no way of leaving the country without visas.

A few years later, in 1998, Nisan had her second child, Stephanie, but it wasn’t until 2001 that the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society helped them get the sponsors needed to leave the country.

They received visas, and they traveled to Vienna, Austria. Nisan and Italiaie stated their case to an officer of the American Embassy and became U.S. religious refugees.

In 2002, Nisan and Italiaie enrolled at Pierce as full-time students. Nisan took photography

courses, while Italiaie took courses in accounting and business. Italiaie also began working toward becoming a certified pastor for the Assemblies of God Churches in Chatsworth.

They ran a Bible study out of their apartment and gathered enough members to begin an Assyrian service to help unite local Assyrians and to keep alive their ancient language and religious beliefs.

Two years later, the service moved to Assemblies of God Churches. Italiaie leads the 2 p.m. Sunday gathering, which is conducted primarily in Aramaic.

As a photography student at Pierce, Nisan eventually joined the school’s Roundup newspaper, and a teacher set her on a new career path.

Rob O’Neil, a journalism professor, saw Nisan’s photography and was fascinated.

“I found out that she had an advanced degree in photography and I looked at her photographs and I thought she shouldn’t be a student here, she should be teaching here,” O’Neil says.

By the winter semester of 2005, Nisan was teaching her first beginning photography course, which was taught using film cameras. Nisan faced many difficulties with the language barrier while teaching a classroom of about 30 students, but she grew more comfortable with each passing semester.

Nisan and Italiaie are happy to be living freely in the United States where persecution for religion is less likely. They do not plan to visit Iran after facing such dark and horrifying persecution.

“Here there are more opportunities to grow,” Nisan says. “It’s not the same way that people in the small countries think about refugees or about immigrants. The way the culture here is different is that it is inviting and welcoming to the new people, especially here in California.”

We had nothing. We had only five suitcases, but we were happy because we were going to a free country.

Rita Nisan Photography ProfessorRita Nisan, an adjunct instructor for photography, is surrounded by images she captured in Iran in 1991 of Kurdish people. Rita Nisan and husband Shamuel Italiaie, display three photographs of Kurdish people. The couple met while working for a church in Iran. Italiaie is a pastor at Assemblies of God Churches in Chatsworth.

A family’s fight to openly express their faith

Photos by Kristen

AslanianIllustrations by Trinidad Gomez

Trinidad Gomez is adorned with a pink and purple wig, lavender wings, horns and low top classic black and white Converse shoes.

Gomez, a 28-year-old MexicanAmerican transgender who identifies as a female, credits her self-discovery and happiness to the freedom and acceptance she found in the Brony community.

“I recently came out as transgender,” Gomez says. “My friends have been very supportive during this whole thing. I can’t really do it alone.”

A Brony is defined as a male, usually in his 20s or college age; not the usual target audience of the television show My Little Pony. according to Patricia Arreola, a 21-year-old linguistics and philosophy major at Los Angeles Pierce College, and a self proclaimed Brony aficionado.

My Little Pony was a series of toys created by Hasbro in the early ‘80s that were turned into a television series targeted toward young girls.

Since then, several TV series reboots have been created. The latest of these reboots, generation four is entitled My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, and while the target audience is still young girls, a new

type of fan has evolved.

Arreola describes two types of individuals that become a Brony. The first is someone who likes the show to get a reaction from society. While others “legitimately believe in the ideas and the values taught in My Little Pony, which is friendship, magic and it gives them an optimistic and friend based view of the world.”

The term Brony was created on the website 4Chan following the release of the series My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, according to thedailybeast.com.

The worldwide My Little Pony phenomenon has led to fan conventions, such as BronyCon, which is a 3-day event in Baltimore.

Regardless of the gender, fans of the show are all considered Bronies, according to Gomez. She has become a well-known figure among the Southern California Bronies, whose Meetup.com web page has more than 1,700 members.

In school, Gomez was bullied and acknowledges that this is a common issue among the Brony community. After high school, she attended California State University, Los Angeles, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts and Letters in animation.

Gomez currently works for an animation

studio in Burbank as an independent artist. It was the animation and writing that first attracted her to the show.

“I watched the whole first season in a week and I just kept watching,” Gomez says.

“I drew my first picture, and I was like, yup, guess who’s a Brony now.”

Lauren Faust, the creator of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, is also known for her work on Foster’s Home for Imaginary Friends and The Powerpuff Girls, she has spoken out on her unexpected fans.

“Up until now, they’ve had to hide that or pretend that they don’t like it or shove it down inside themselves,” said Faust in a 2012 interview with Bitch, a quarterly magazine. “Now, because of the Brony community, they can express it.”

Friendship is a common theme in the community.

Jessica Crawford, 29, also credits the show and its fandom for her current friends. Growing up in Tennessee, she moved around the country and currently lives in Los Angeles

“I wish I would have known about My Little Pony before,” Crawford says.

“Basically it changed my life.”

When her roommate moved out, she became depressed and would only leave her

home to go to the store.

For Crawford, it was through Netflix that she first saw My Little Pony

After a few episodes she was hooked and watched all three seasons available at that time. She then started looking into events on the Internet, and found the Socal Bronies Meetup.com page.

She was hesitant about attending but became more comfortable among the members and soon began trading information about shows that they had found on the Internet.

It is more than just a cartoon for Crawford, who wants to share with others the different lessons that the show teaches, including communication among friends and how to work together to solve problems.

Since becoming part of the fandom, she’s no longer depressed and she hangs out with other Bronies.

“I actually found something that I enjoy and makes me feel better,” Crawford says.

One of many friends she has found is Gil Arzola, 56. He is secretive about the fandom and does not want to release where he currently works.

The only person that knows about his fandom is his mother.

“My brother has his suspicions. When

I’m going through the channels I skip over My Little Pony, Arzola says. He smiles as he proudly wears his shirt adorned with Queen Chrysalis, a character from the My Little Pony universe.

It’s common for Bronies to be secretive, but Gomez has the full support of her family including her mother Teresa.

“I try to listen to her when she tells me something,” Teresa says. While they do not watch the show together, she is aware of her daughter’s love of art. “They gifted her when she was in school, and I know she went into it because of her drawings.”

She is kept busy with her Youtube channel, Dysfunctional Equestria. The channel was created to entertain the Brony community, but also so fans would have a place to “heal and vent.”

“My primary passion is to entertain people,” Gomez says. However, there are still people who find the fandom strange.

“A lot of Bronies get mislabeled by society,” Gomez says. “It’s not really a good thing because people don’t really understand it. We’re normal people who just happen to like a TV show.

Trinidad Gomez displays My Little Pony inspired art work at home. Below: Gomez created a piece titled Best Pony, which is a term used to proclaim a Brony’s favorite character from the series My Little Pony: Friendship is MagicLover of the sun and sand, Genna Gold hopes to become a writer for National Geographic

Mohammad Djauhari, aka Q, is a film enthusiast who can be found on the dance floor, or photographing life. He proves chivalry is not dead.

The camera is an extension of Lynn Levitt’s arm; it never leaves her side. She is the mommy of the newsroom and enjoys Burning Man

Kristen Aslanian is a jazz hands connoisseur and talented photographer. Her great eye and passion drives her.

This Argentinian is a future backpack journalist. Giuliana Orlandoni is a gifted photographer and writer, as well as a soccer fanatic.

Raymond Chavez the fashionisto loves his clothes almost as much as getting a good interview and scooping the competition.

Monica Velasquez, although never on time, comes ready to report, and she always brings her A-game.

When it comes to style and attitude, Jeffrey Howard has it all. His youthful demeanor brightens up the newsroom in times of stress.

Robyn Pennington isn’t as intimidating as she looks. She’s a passionate writer who would “kill” for a story.

Diana Masaz is an aspiring news anchor. When she isn’t bumping to her tunes you can find her composing at a computer.

While she is not busy in mosh pits, Ana Sierra uses photography and journalism as way of self expression.

This Chicana is never without her gold chains and cowgirl boots. Sonia Gurrola adds a special swagger to the Bull team.

Richie Zamora makes everyone smile by using his storytelling skills to make his subjects jump off the page.

This opinionated fashion blogger adds color to the newsroom. Don’t talk to Marielle J. Stober until she is highly caffeinated.

A freshman fresh out of high school, Torry Hughes is a broadcast major who hopes to travel the world.