SOMEBODY HAS TO DO IT

CRIME SCENE AND TRAUMA CLEANERS HELP PICK UP THE PHYSICAL AND EMOTIONAL PIECES

CRIME SCENE AND TRAUMA CLEANERS HELP PICK UP THE PHYSICAL AND EMOTIONAL PIECES

BY DIEGO BARAJAS

BY LYNN ROSADO

BY ERICK CERON

BY DIEGO BARAJAS

BY LYNN ROSADO

BY ERICK CERON

BY RICHIE ZAMORA

BY RICHIE ZAMORA

Story by: Mariey Stober

Photos by: Nicolas Heredia

Story by: Mariey Stober

Photos by: Nicolas Heredia

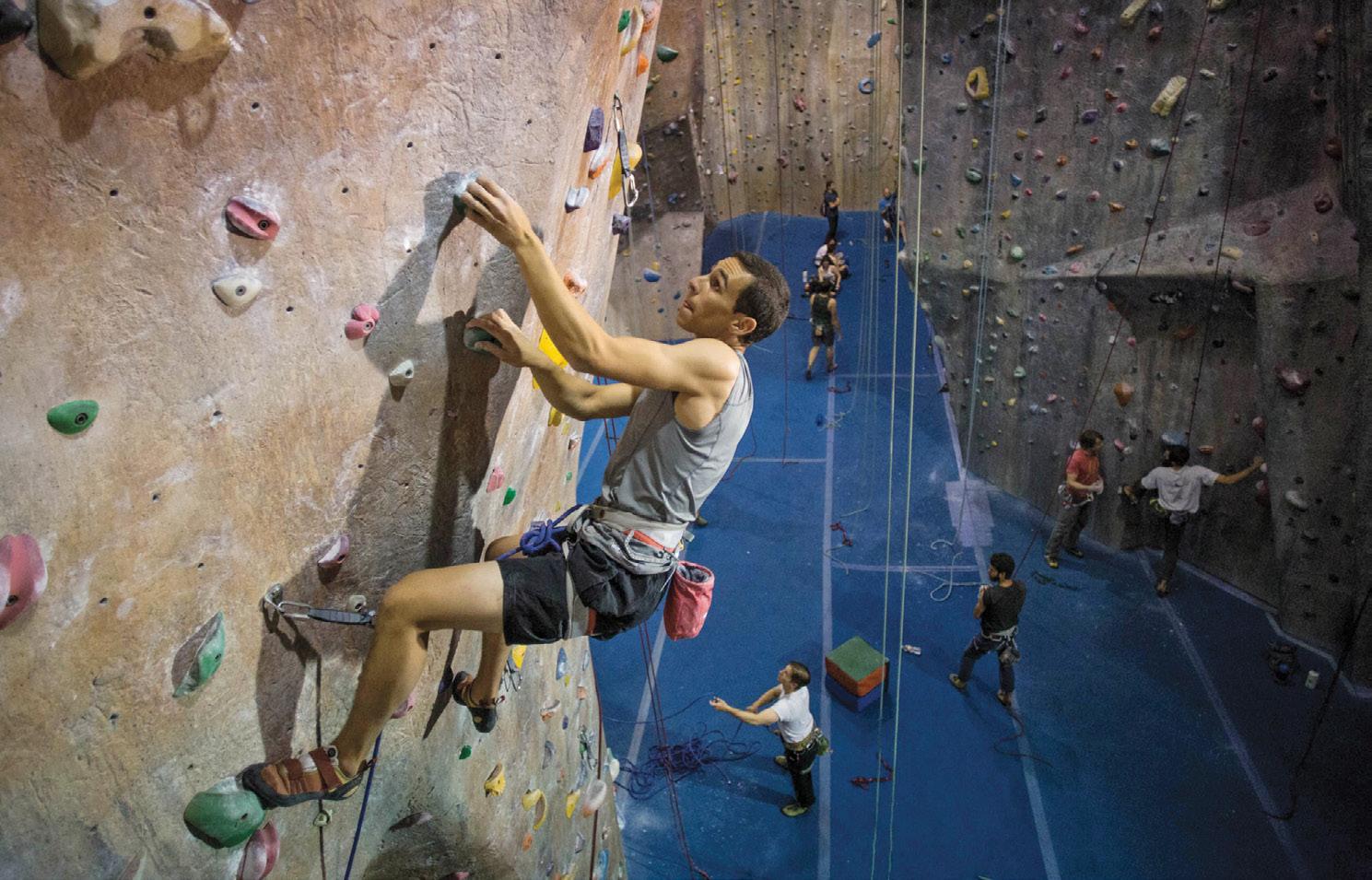

Pearls of sweat roll down the sun-drenched arms of Ryan Talbot, 19. The tense muscles of his tangled limbs quake under the weight of his toned frame. After a brief moment of hesitation, Talbot inhales sharply before launching himself upward. Scathing pain twists his calm expression as the rock’s jagged surface scores the skin of his calloused fingers.

This brief discomfort is worth the rush administered to his system while climbing.

Talbot’s love affair with rock climbing manifested during a trip to Joshua Tree with the Boy Scouts. He was 11 years old and terrified of heights. Talbot recalls the fear he felt while staring down the 134-foot descent.

“Getting over that first ledge was hard because I thought I’d slip and fall,” Talbot laughed. “But halfway down I turned and saw the view. After that I was hooked.”

Now an instructor at Boulderdash Climbing in Westlake Village, California Talbot shares his enthusiasm with colleagues and patrons. The highest difficulty grade he has climbed is a 5.11c.

Ryan Talbot scales a 50-foot. climb at Boulderdash Indoor Rock Climbing in Westlake Village, Calif.

Ryan Talbot scales a 50-foot. climb at Boulderdash Indoor Rock Climbing in Westlake Village, Calif.

On the Yosemite Decimal System, or “YDS,” a 5.11c would be intermediate. A higher climb grade means a greater fall. Knowing that, he approaches each ascent fully focused. But even with perfect body placement and a secure rope system, accidents happen.

“What we do is dangerous. You will fall, guaranteed. So it’s important to learn how to fall correctly,” Talbot said.

As an instructor, Talbot helps make sure the men and women in his charge are equipped with the knowledge they need.

Central to climbing is the belayer. That person is responsible for securing active ropes, and acts as the brakes in the event of a fall.

“The most dangerous thing you could do as the belay is let go of the rope,” Talbot said.

For added safety, each instructor is paired with another climber. Talbot was assigned his partner in mid-January 2015. Liesbeth Peace, 18, got a taste for climbing while visiting Germany three years earlier.

Waldhochseilgarten Jungfernheide Park near Berlin touts extensive rope and obstacle courses in the forest canopy.

“It was intense climbing across something so far up,” Peace recalled. Stateside, Peace takes her obsession to new heights. Tightening the laces of her roughed up La Sportiva Mythos shoes, she stands idle at the base of a 65-foot run. The green path labeled “That Ryan T. is so hot right now” is a 5.11 c. Breathing out slowly, Peace begins.

Below her, Talbot quickly reins in the slacked rope. Hopping upward he pulls the bottom length of rope with his right hand as his left swiftly feeds the top end into the belay device. A sudden jerk from above catches Talbot’s attention. Peace has stopped moving.

Caught at the 45-foot marker, Peace dangles from the artificial rock face. She relies on the sticky soles of her shoes to anchor her in place.

Coating both hands in a visible layer of fine white chalk powder, Peace breathes in steadily.

“We have to be really careful with the higher climbs because anything could go wrong,” Talbot said.

Exhaustion is a climber’s mortal enemy. The energy needed to move

along a wall is draining. Experts and amateurs alike are not immune to the prolonged strain on their bodies. With holds the size of dimes to hang on to, it’s not long before a climber’s limbs begin to shake.

Luneberg calls this having a “belayer’s eye.”

This heightened awareness is demonstrated by all Boulderdash employees. As Talbot works the belay for Peace, he briefly glances to either side.

“I always have my eyes peeled in the off chance that something happens,” Talbot said.

A sophomore studying medicine and neuroscience at Moorpark College, Talbot can administer first-aid care to injured climbers. Since he began working at Boulderdash, he has seen many accidents.

“It’s you versus you when you climb,” Christiaan Luneberg said. “Everything else is just secondary.” Luneberg, 47, began climbing after graduating high school. Before opening Boulderdash 10 years ago with business partner Paul Farkas, Luneberg worked a menagerie of jobs. Even so, his passion for the sport does not dissipate.

“I like the climbs that you fall on,” Luneberg said. “If you don’t fall you can’t learn.”

Mellow like the iconic surfers of the 1960’s, Luneberg welcomes patrons with a smile. Slipping away from the front desk, he explores the entire length of the climb zone.

“When I’m walking the gym I keep my eye out for safety hazards or risks,” Luneberg said.

“Most falls hit somewhere on the spine and the back of the head,” Talbot said. “Bouldering is worse because those are full-ground falls.”

The trick to staying on course is to focus. Luneberg, who scaled El Captains’ infamous Dawn Wall twice, veers away from danger by “keeping a clear head.”

“Climbing is all mental,” Luneberg said. “If you think you can’t make it up a climb then you won’t. The biggest issue we all face is psyching ourselves out.”

Despite Talbot’s relative newness, he has adapted to the role of a teacher. Briana Carter, 20, has been close friends with Talbot for six years. She has since noticed subtle differences.

“He was able to talk me up a waterfall and back down it,” Carter said. “That’s a huge accomplishment.”

“What we do is dangerous. You will fall, guranteed.

-Ryan TalbotTalbot takes on the 5.11c run called “That Ryan T. is so hot right now.”

If you thought cleaning rotten eggs sitting in your fridge was bad, think again. An aroma of urine and feces roams the underground city known as the sewers. Four hundred million gallons of raw sewage are being pumped into Hyperion Treatment Plant a day making it the city’s largest wastewater treatment plant. Located in southwest Los Angeles, the plant has been in operation since 1894.

However, like your fridge at home, someone has to

clean up the rotting mess that clogs up the sewers. That is where Kent Carlson comes onto the scene.

Carlson has always found a way to be around water. After graduating from San Pedro High School, Carlson joined the U.S. Navy where he was trained and worked as a military machinist, which manufactured parts out of metal in a submarine repair facility at Pearl Harbor.

Carlson’s wastewater adventure began after he got out of the Navy and found work in the San Pedro

shipyard, where he overheard the city was hiring a trained machinist.

He applied for the job and was hired at Hyperion Treatment Plant. Carlson heard that the city had another opening in the sewer department and he was hired to repair the pumping plants and to clean the sewers.

Carlson has worked with the city of Los Angeles for more than 25 years. Carlson’s current position is Sanitation Wastewater Manager at the Wastewater Collection Systems Division in Tarzana.

Carlson said there are many reasons why a sewer or drain line might become clogged. One of the most common is that tree roots grow into the sewer line. Also, random objects clog the line. It’s an ongoing problem because

only removing the tree, or rodding, can solve it. As the manager, Carlson must help all the crews and make sure they have the resources required to rod and unclog the sewers.

Once the sewer is clean, the used water runs underground to the Ventura Wastewater Treatment Plant. At this facility there is a three-step process where the wastewater is treated and then delivered to reclaimed water customers. Twentysix-year-old John Reeder is an employee at the Ventura Wastewater Treatment Plant.

Unlike Carlson, Reeder hasn’t always been around water. Before going into sewer business, Reeder wanted to be a history teacher.

He soon began taking

classes at Ventura College for wastewater treatment. Once Reeder had an understanding of the process, he searched for an internship.

A typical day at work for Reeder begins with meeting other plant operators to discuss current conditions, and to find out if there are any major problems. Reeder then works with an operator, or he performs other duties, such as maintaining the facility.

Reeder deals with the daily nauseating smells, such as the odor of dark brown raw sewage that eventually stacks into large piles. Bacteria could also infest his body if it’s not handled correctly.

“I knew going into this field that it’s a very dirty and smelly job. I often do get dirty and some days are smellier and dirtier than others, and you can get used to some of the smells, but others you never get used to. It is good practice to bring a second set of clothes to change into at the end of the day. It is possible to get splashed with or breathe in dangerous chemicals, though that is rare, and you always have to be aware of your surroundings,” Reeder said.

Unlike the dirt and grime, Reeder’s efforts are not devoted to going down the sewer, as he works toward his career goal.

“It’s worth working here for me to get started in the wastewater field and to get the knowledge and experience to advance my career. I enjoy the variety of the work, the teamwork and the problem solving aspect. You never know what each day is going to be like. I like being a part of process that

Right: Jose Mendwz and Elton Howardton work on un-clogging a maintenance hole by removing dislodged grease and debris near the Wastewater Collection Systems Division in Tarzana, Calif.

Bottom Right: Ernesto Corral feeds the rod into the manhole as Jeffrey Petillo guides the rod into the desired spot with a gap headed shovel in Reseda, Calif.

helps protect public health and the environment. I could not imagine people coming in from all over the world to enjoy California’s beaches if raw sewage was sent untreated into the environment,” Reeder said.

As important as this work is, Reeder doesn’t always get credit for his job outside the facility.

“I suspect like most infrastructure jobs, it is taken for granted by the majority of people. Part of the reason I believe is because the public does not often see wastewater treatment operators and know how the wastewater is treated. I get plenty of thanks from my team and I feel great that I get to help turn something as filthy as sewage into water that is not harmful to the environment,” Reeder said.

The next time you want to the clean the rotten eggs inside your fridge, just remember that someone out there has it 10 times worse.

“ I feel great that I get to help turn something as filthy as sewage into water.

-John ReederTop: A wide view of the primary clarifier inside of the Wastewater Treatment Plant.

Avariety of tattoos cover his arms. His salt and pepper hair is accompanied by honey brown aviator sunglasses. This 6’5” military veteran quietly sits underneath the bright sun, remembering a time when he never imagined he would become a professional bounty hunter. A raspy voice shares his experience working alongside his wife traveling the United States.

When someone fails to show up for a mandated court date, or doesn’t pay bail, compensation is given to whoever finds the fugitives and turns them in. Each state has different requirements, but bounty hunters are responsible for injuries and property damage. California grants bounty hunters the right to capture a fugitive at any time, break into homes, and pursue a felon into another state.

However, bounty hunters can spend up to life in prison for capturing the wrong person. Laurien and Luana DuTremble have worked together as professional bounty hunters for five years. In the past decade, bounty hunters have captured an estimated 25,000 fugitives in the United States with a return rate of 99 percent, according to Rob Dick, a bounty hunter for the past 29 years. Even with these statistics they often aren’t welcome in the law enforcement community.

“Either they hate us or they think we’re really cool and love us,” Laurien DuTremble said. “But I’d like to see coordination and cooperation between all law enforcement agencies so we can get those people off the streets.”

DuTremble’s wife and partner said that her prior profession as a receptionist wasn’t as exciting and flexible.

Photo Illustration by: Diego Barajas Story by: Kitty Rodriguez“This was just so cool. Being our own bosses and feeling like we were doing good,” Luana DuTremble said. “The motivation for me was helping these people that fronted money to these con’s that think they’re so hip and trick you with their smile and wit.”

Not knowing what kind of situation he could be entering, Laurien DuTremble has feared hurting someone innocent. It is important to know when to use lethal and nonlethal force. Required licenses and permits are necessary to be armed with tools such as tasers, pepper spray and a baton.

“I’ve tackled gang members off bicycles. I’ve pulled 6’8”, 300 pound guys out of trucks and to the ground in a split second without any hesitation or fear. But I have always had a fear of someone innocent getting hurt. I think one of the main reasons it never happened was because it was always and foremost on my mind.” Laurien DuTremble said.

Dick, met Laurien through training courses he offers for those who are interested in bounty hunting. With a background as a professional bodyguard for the Casey Anthony trial, his extensive skills and experience have given him a reputation.

Laurien and Dick became partners and traveled the United States at the beginning of his career.

“You go through a few [partners]

until you get a rhythm. It’s like almost being married,” Dick says. “You have to be able to not only get along with someone but think alike when you’re making an arrest. Laurien and I, we just knew what each other was thinking.”

At the age of 60, Laurien DuTremble stays in shape by training in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu two-to-three times a week. There have been circumstances where a suspect, under the influence of drugs, became twice as strong.

His trainer makes sure that Laurien is exhausted before entering a cage fight, reminding him how tired he will feel fighting for his life.

“He made sure that when I got into a fight I was already out of breath,” Laurien DuTremble said. “That’s what you’re doing when they’re going after your gun. You are going to be fighting for each breath and you are going to do anything and everything possible.”

Many laws have changed throughout the years, making it difficult to earn a fair wage.

“I didn’t do it for the money,” Laurien said with a serious glare. He said he’s fortunate to be alive and he believes he wouldn’t have been able to survive everything he has without faith.

“I have always been religious. Nothing could have allowed me to escape some of the things I have been through in my life without it being a miracle.”

It’s early in the morning at the Pierce College Farm. The sound of the wind whips the grass, the smell of soil and animal manure are the first to invade the senses. A ray of sun hits the field and the sweat rolls down one’s forehead signaling the beginning of a workday.

It’s time for animals to be fed, for corrals to be cleaned and pastures to be mown. While some college women might be putting on makeup and getting ready for school, Marcie Sakadjian is already starting a new day at the farm.

On any given day, Sakadjian can be seen walking around with an approachable smile on her face, wearing blue jeans, work boots, a t-shirt and a baseball cap.

Her petite figure might make people doubt her capacity to do the work she does at the farm. From operating a 5410 John Deere Tractor, to fencing the fields, she preps the pastures and makes

sure they are ready for the harvest season. Later, Sakadjian shovels layers of dirt out of the sheep’s paddock and pulls it in a skip loader tractor. “I really love working with the big equipment, the tractors. I like the field, and I love cows. Cows are my favorite,” Sakadjian said.

Originally a nursing major, Sakadjian spent her first two years at Pierce trying to get into the medical field. It wasn’t until she changed her major to Registered Veterinary Technology, and took Animal Science 501, that she found her passion for animals, agriculture and farms.

“At the pace she’s going, I wouldn’t be surprised that in 10 years, she’s running a 5,000 head cattle ranch” said Greg Murk, the senior agriculture technician at Pierce College.

Sakadjian manages school and a full-time position at the farm by taking classes that don’t interfere with her

work schedule.

“I tried to pick up classes that work around my schedule, and I don’t sleep very much,” Sakadjian said.

She has worked as a senior agriculture assistant at the farm for the past year-and-a-half, but she has been employed there for the last five years.

“That girl is going to run a farm at one point in her life,” said Stacie Carpio, Sakadjian’s friend of four years, who’s also a student worker at the farm. Sakadjian also assists pre vet and agriculture students.

Regarded as an extraordinary worker by many of her peers, Sakadjian’s fearless passion to work among farm animals and operate heavy machinery is impressive. For her, the hardships and sacrifices that come with the work she does are all worth it.

“Farming is more like a lifestyle. I just love it,” Sakadjian said.

The All Aspects “eyes” logo can be spotted around the Los Angeles area.

The All Aspects “eyes” logo can be spotted around the Los Angeles area.

Half of the crew slinks to the site with their tools while the other half keeps eyes on the surrounding area. If any security or police show up they’ll have to make a quick getaway. The location has been scouted ahead of time, the preparations have been made and the time has come to execute the plan.

Be it art or vandalism, All Aspects Apparel takes daring and controversial approaches with their “eyes” logo to promote their brand and ideals.

“The eyes are something mysterious,” said Jeremy Lieber about the company’s logo. “You don’t know if it represents something bad or good.”

Provoking thought has been the prominent focus of the San Fernando Valley clothing company since its inception in 2010.

“The posters aren’t there to sell t-shirts,” Lieber said. “It’s there to make you question what am I doing and why am I doing it and what am I looking at and why am I looking at it?”

The tight knit group met in the Valley at Granada High School, and started printing shirts for fun.

The idea of All Aspects, however, first flourished when the group decided to

make senior class sweaters and t-shirts.

“The school did make their own sweaters, but we made ours and far more people wore ours,” said Lieber, who has been dubbed the mastermind behind the label.

Today, All Aspects ships regularly across the country and recently began to expand into the international market, according to Liber. As the company grows, popularity doesn’t seem to be the immediate goal.

According to the group, catering to creative thinkers and obtaining followers toward their movement is what they’re really after. The street art that accompanies their brand helps attract those thoughtful enough to seek it.

Using a simple yet enticing logo, All Aspects has made their mark on the streets of Los Angeles and has even stretched the coast of California, the biggest of which is a large poster seen off the 5 Freeway close to Downtown.

“That one is up next to Obey’s. The cool thing is their recent catalog has a picture of their poster with our eyes still up there,” said Sam Fischer, another member of All Aspects.

The process is a lot more organized then one might think. It all starts with

reconnaissance, followed by rough measurements, printing and execution. During the installation, a small group works on the piece while others keep watch in a car.

The crew maintains constant communication in case of any trouble. And there are most definitely close calls.

“Cops don’t care what your intentions are,” said Fischer. “They just want to arrest you for graffiti or vandalism.”

Whether it’s wrong or not, the All Aspects crew think of what they do as art first and foremost.

Street art goes back to the cavemen, according to David Blumenkrantz, a photographer and visual communications professor at CSUN and Pierce. Paintings have been found dating back 40,800 years where man has made his mark with handprints and drawings of animals on cave walls.

“What you’ve seen in more recent years is commercialization of it a little bit,” said Blumenkrantz. “These guys are straddling the line between being rebellious guerrilla artists and also marketing their image.”

It’s a risky venture, but seems to be working. With their subliminal advertising, the reward outweighs the risk.

Clockwise from Top: Sydney Brushwood spins in place with the fire staff. Brushwood’swirls her fans around her body. Brushwood dances with her metal fans, tracing her arms.

Ahot light swirls around a young woman, feeling not the cold grasp of the night but the warm embrace of the flames. Faint roars of the hot element are heard as it paints the night with its orange light. The young lady, with hair auburn as the element that she controls, is focused on the glowing heat tipped at five points of two metal fans. She spins her body and creates a cocoon of fire. With a quick whip, she extinguishes the flames and smiles. This young lady is Sydney Brushwood, a 22-year-old psychology major at Pierce College.

Brushwood recalls her first time fire

spinning in the Culver City Fire Club at the age of 19. “I tried out the fire sword. It’s a beginners tool. I have caught on fire a handful of times, but they were tiny and I wasn’t in any danger.”

“I was really worried,” recalled Josh Badger, Brushwood’s boyfriend, about the first time going to the fire club. “[I would think] she’ll go up in flames. It was a lot of fire.”

Brushwood said that she wears cotton-based clothing such as leggings and a tank top. She would sometimes wear jeans instead of the cotton leggings. Long nomex gloves are worn with her outfit to protect her hands from the heat.

After becoming comfortable handling the fire, she moved on to using a staff, a pole with flammable tips at both ends. She then graduated to metal fans and a juggling item called a diabolo, a tool of two attached cups spun on a string connecting two sticks that the user handles.

“She did baton twirling in high school I think, and she’s got a natural grace with staff as a result,” said Scott McCoy, who runs the fire club in Culver City.

“I do want to perform professionally,” said Brushwood. “But my real interest is psychology. I want to be a psychology teacher, to be a real influence.”

Story

Story

From hitting the books to hitting the bag

Story and Photos by: Diego Barajas

Story and Photos by: Diego Barajas

Whether in a classroom wearing jeans and a t-shirt or in the gym with his royal blue Muay Thai shorts, covered in yellow accents with red trimming, his intensity is always the same.

Focusing on Muay Thai for the past two years, Omar Suarez first gained interest in martial arts at the age of 10, following his enrollment at World Tae Kwon Do, a studio in Winnetka, California.

Suarez has earned his second degree black belt in Tae Kwon Do, also earning a second Dan Kukkiwon certificate, which is recognized worldwide

“I’ve been doing [Tae Kwon Do] since I was 10,” Suarez said. “My dad just kind of enrolled me into a regular class to try it out and I’ve been doing it ever since.”

Suarez has continued to practice Tae Kwon Do, eventually changing gyms to Kings Combat Sports, were he would pursue Muay Thai and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

Simultaneously, Suarez balances being a full time student at Pierce College, taking 18 units, as well tutoring in sociology.

An economics major, Suarez said, “I want to get published, I want to do my own research and do articles.”

Training for the past two years, he has shifted his focus to Muay Thai, a combat sport consisting of standup striking with 8 points of contact, hands, feet, elbows and knees.

Suarez has utilized his skills to become a semi-professional fighter, making his debut March of 2015, in a losing effort.

Despite his early career in which he has developed his skills, Suarez sometimes struggles with finding a reason to continue and “keeping at it.”

Omar Suarez strikes the heavy bag with a Muay Thai roundhouse kick at Kings Combat Sports in Chatsworth, Calif.“Sometimes I just feel like man f*** it,” Suarez said. “I’m just going to drop everything. I really don’t need to fight. I have enough self defense to go against anybody in the street. Keeping at it is the hardest part.”

A fellow Muay Thai classmate, Benito Mendez said, Suarez is “Always willing to compete. He has fighting spirit and is always down to roll.”A fighters diet must be monitored carefully, as maintaining weight is a priority in the sport. Prior to his last fight, Suarez was nine pounds over the designated weight class.

He was forced to use a sauna and shadowboxing in the sun to dehydrate his body to make weight.“Cutting weight is the worst part,“ Suarez said. “I’m addicted to food.”

In preparation for his fights, Suarez also uses sensory deprivation tanks, a light and sound free environment of water and dissolved Epsom salt heated at body temperature, deigned to help mediate and relax.

Prior to a match, Suarez focuses solely on the task at hand, eliminating distractions during the week, to “make sure nothing gets in the way.”

“I relax and do a lot meditation,

vizualizing and imagining what I’m going to do in the fight,” Suarez said.

“The only thing in my training that changes before a fight is I do a lot more pad work with my trainer. It’s basically to get me as technically sharp as possible.”

Luis Reyes, Suarez’s Muay Thai instructor, is a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Black Belt and 2004 U.S. National Tae Kwon Do Champion. Suarez said, “It takes about 8-15 years to receive that level of achievement.”

“First you have to put yourself out there. You have to get noticed by the promoters. It’s just like MMA,” Reyes said.

Aware that his martial arts lifestyle depends on the wear and tear his body can endure, he understands it is nothing to be taken for granted. A personal goal of Suarez’s is to fight professionally, and he would, “be satisfied with a few wins in the UFC.”

“I want to become a professional fighter. I have been doing martial arts for over half my life and it would satisfy me so much to know that I am able to go at it with the very best of fighters,” Suarez said. “I want to be able to do martial arts for as long as I live.”

It’s hard to move through the cramped room. Statues, porcelain tea cups, and trinkets of all kinds cover every surface. The place looks like an antique shop that hasn’t been open in months. Sometime in the fall, the resident of this San Diego home died alone of natural causes. The body was not discovered until March. In a home filled with the result of years of amassing objects of all kinds, the job of cleaning up this scene falls on crime and trauma scene decontamination crews.

In the field, crews go into an area after there has been an incident that could render a place bio hazardous, not only to professionally clean the area, but to decontaminate it and return it to its previous state. Professional Crime Scene Cleaners are qualified to handle a level of dirty that most people will never have to encounter.

Ethan Phearson, 30, is president and coowner of Cendecon, a crime scene clean up

Story by: Richie Zamora Photos by: Nicolas Herediacompany that has been in service for eight years, serving Los Angeles and beyond.

“We specialize in crime scene cleanups, hording clean outs, gross filth decontamination,” Phearson said. “Pretty much anything nobody wants to do.”

Respiratory and other health problems can come from a hazardous environment, but when a violent death or suicide occurs, blood and other bodily fluids pose the greatest threat to these crews because of the potential for communicable disease.

“We’re dealing with biohazardous material, so of course there’s always a safety concern, but we have PPE, personal protective equipment,” Phearson said. “We have full body suits, respirators and masks, gloves, goggles, the whole nine.”

These kinds of suits are standard practice for those working with possible biohazardous or chemical substances, according to Beth

Benne, director of the Student Health Centerat Pierce College.

“The PPE has really come into its own. Hospitals now have them,” Benne said. “But it’s something that has to be taught, how to properly put the equipment on and take it off in the appropriate manner so that we don’t accidently contaminate ourselves after a decontaminating event.”

Benne said that after the job is done the potential danger for the crew to contaminate themselves is greater when they remove the equipment. Improper protocol of removing PPE was responsible for the Ebola contamination of two nurses treating a patient in Texas in October of 2014.

“This is where the breakdown occurred in Texas. The training of the users was not adequate. They were not appropriately trained on how to disrobe,” Benne said. “Communicable diseases are fascinating because there are so many different types. It really makes an impact. It effects everything. Everything comes to a screeching halt.”

Brandon Beban, 22, is an employee of Cendecon. Beban admittted the job is tough and could be risky depending on the particular assignment, but while

the work may throw others off, he was prepared from the start.

“I knew what I was walking into,” Beban said. “My first job was a hoarder’s house. That took three days to clean out and there was lots of heavy lifting, but it was basically what I expected.”

Phearson and his crew will take jobs as they come and will travel anywhere from Fresno to San Diego, but mostly they service Bakersfield and Los Angeles County. Phearson said that similar jobs usally come grouped together within a short time of each other.

“Interestingly enough, types of jobs come in blocks. It’s really odd,” Phearson said. “One time we’ll get like two or three suicides within a week or two, and then we’ll get a couple hoarding jobs and then we’ll get a couple decomps.”

A decomp is when there is an unattended death and decomposition of the body has begun. These kinds of assingments are the most difficult as there is a greater risk to come in contact with bodily fluids.

There is a delicate nature to the work to ensure that a scene is a sanitary environment after the work is done, but another part of the job for Phearson and his crew that doesn’t require powerful cleaning agents or protective equipment can be just as delicate and tough to navigate.

After eight years of working in the CTS decon field, Phearson has gotten

used to the sights and smells, but something that doesn’t get easier with time that is the part of his job where he is dealing with the families of the victims.

“The police departments and the sheriff’s departments are not legally allowed to refer a specific company, so usually it’s the family that contacts us or a friend or neighbor,” Phearson said. “It’s all usually a pretty sad situation. Whether it’s a hoarder or a death, it’s sad no matter how you look at it.”

“It really depends on how the person is handling it,” Phearson said.

“Everybody handles grief differently. Some people are making jokes about the person who died. Sometimes they’re very quiet and they just point us in the right direction. We just react depending on what their mood is.”

As of the early 2000’s there weren’t many established CTS decon companies, so the burden of cleaning up after a violent or unexpected death was the responsibility of the family.

Nancy, who asked her last name not be published, came to California from Buffalo, New York, to help settle her brother-in-law’s arrangements. She felt overwhelmed and relied on Phearson’s comforting attitude and experience to get through what was new situation fo rher and her family.

“It’s not just the tangible, physical things that need to be done, but the emotional. I called Ethan and he answered right away and answered my questions and really gave us some piece of mind,” she said. “I see him here working, and he’s on the phone a lot and I think, that was me calling him all the time when he was on a job. They were so reassuring.”

These situations can leave more than just a physical stain. They can leave an emotional one on friends and family. Having to deal with grief is hard enough, but being able to trust that your home is safe and clean can go a long way to help move on.

“It’s not just the tangible, physical things that need to be done, but the emotional.

-Nancy (last name withheld)

She wears her team’s uniform with pride as she skates around the flat track with her navy blue jammer helmet that has lime green stars indicating her position.

Dressed ready to compete, 37-yearold Staci Park sports tattoos on her arms and legs, with several of them an ode to the Japanese character Hello Kitty.

Park founded the San Fernando Valley Roller Derby league in 2012, making it the Valley’s first and only flat track league.

Park played for the L.A. Derby Dolls, but the commute from the Valley and her three daughters’ interest in roller derby led her to create a junior league, which eventually led to the adult league.

“I always thought roller derby in the Valley would be such a good thing because there’s such a market here,” Park said. “There’s a lot of women here. Not everyone wants to travel over the hill to play roller derby or commit that much to roller derby as a hobby. I just wanted to make it more accessible to women.”

In roller derby, everyone, including the referees, have what they call a “derby name.” Park’s derby name is Killo Kitty.

“I chose Killo Kitty because I love Hello Kitty so much,” Park said. “I have a bunch of Hello Kitty tattoos and I like to kill things, and it’s super aggressive.”

In a double header against the Angel City Derby Girls in April, fans showed up to the Lot in Sylmar, California, with posters, and paid to get their faces painted SFV Roller Derby navy and green.

“I’m actually shocked that people care and want to pay to come and watch me skate around,” Park said.

“I skate around everyday and it’s nothing special. I feel honored that those people do, and it’s an amazing feeling. I really appreciate it.”

Park is the captain and coach, and

to hear her tell it, driven to win.

“I am the most competitive person you’ll ever meet, and I’m going to say that because I’m competitive,” Park said. “I love it when we’re down by 10 points and the adrenaline has to kick in and your mind has to focus, and everyone has to come together as a team in order to win. That’s my favorite part about any kind of sport, the competitive aspect of trying to win something. That’s what it’s all aboutwinning s***.”

Melinda “Legacy” Lesley, a SFV derby player, received her certificate from the ASL interpreter program at Pierce College in 2005. Lesley has been best friends with Park since they met in 2007.

Lesley started playing roller derby in 2005 but was sidelined for a year-and-a-half after breaking her leg in her second practice, initially choosing Broken Legacy as her derby name.

“When I first got back to the track, I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing, and she really taught me to get out there and put it all on the track to give it your all,” Lesley said.

Before roller derby, Park played tournament paintball for five years. Due to a lack of women in the sport, she wanted to play something that was more encouraging.

“I love the fact that roller derby is so women empowering, a ‘you go girl’ kind of deal,” Park said. “No matter what body type you have, you can play roller derby. There’s a spot

for everyone.”

The team consists of only women, but any gender is welcome as a referee.

Richard San Agustin is the head referee for SFV and has known Park for about three years.

Agustin recognizes the physical aspect of roller derby.

“Roller derby started a really long time ago and was really big in the ‘70’s. It’s definitely gaining a lot more popularity. It’s one of the most

underappreciated sports. It’s very physical,” he said.

Agustin said that to become a referee you have to know how to skate and to do 10 laps in under a minute-and-a-half.

“Just to become a ref you have to learn to skate,” Agustin said. “There are skating assessments. That’s just a series of learning how to maneuver yourself while on skates, being able to get out the way of hits and being able to fall properly, skate forward,

backward and sideways.”

Park doesn’t think there’s anything bigger that she wants to do with her team and believes she has accomplished so much already.

“I want to compete here for the next couple years,” Park said. “Usually the shelf life of a derby girl is five years and I’m going on almost nine, so I’m probably only good for another couple years. I just want us to have fun. The ultimate goal is to have fun and kick ass.”

Above: Stacy Park, aka Killo Kitty, pushes aside an Angel City Derby Girl during a double header in Sylmar, Calif. Below: Park is the founder of the SFV Roller Derby team.From racing motorcycles to performing stunts in the entertainment industry, the passion remains consistent.

Whether he is dressed as a pirate, wearing a brown tricornered hat, brown coat and sporting a beard, or plunging off a bridge into a river, he is always prepared.

A stuntman for more than 30 years, Mark Donaldson knew he would never work a nine-to-five job. He credits his perseverance with helping fulfill his dream of moving from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to Los Angeles to make it happen.

Raised in Louisiana, Donaldson developed an interest in motorcycles at an early age. He began riding by 12, racing competitively in motocross by 14 and he became a professional by 17.

Friends for more than 40 years, Freddie Rapuana and Donaldson lived near each other and attended the same school. Initially closer with Donaldson’s brother, the two eventually became friends.

“We were probably a little bit more on the same page as far as the things that we were interested in as teenagers. That’s kind of how we began our friendship,” Rapuana said. “A lot of it revolved around our love of motorcycles, which is something that’s a huge part of his life.”

As he continued to race professionally, Donaldson realized within his first year that he wouldn’t be able to make it to the top of the ranks, and he investigated other career opportunities. Donaldson began to look into the stunt industry.

“I loved being outside, I loved playing,” Donaldson said. “When I found out that there was a job that you can actually play all of your career, wow that’s the perfect job.”

Realizing the stunt industry was for him, Donaldson planned the move to California for two years before leaving home.

He worked numerous jobs where he began to save money, allowing him time while living in

Los Angeles to learn the ropes of his new profession.

A Los Angeles resident at 22, Donaldson began visiting the Stuntmen’s Association of Motion Pictures, a fraternal organization, asking questions about the necessary requirements to become a stuntman, while also taking gymnastics classes.

He was directed to Los Angeles Valley College, where Donaldson had the opportunity to meet young people who wanted to pursue the same goals, helping him make connections and get pointers.

“The first thing they will teach you is how to do a studio fight, because for years that was your bread and butter. You did more studio fights than anything,” Donaldson said. “From there, you were given chances to maybe do a motorcycle stunt or be in a car chase scene but maybe you were one of the cars in the very back of the line.”

Donaldson would use his skill set to acquire future work, such as “National Treasure“ and the “Pirates of the Caribbean” franchise. As most stuntmen do not have agents, work comes from word of mouth, friends hiring friends and recommendations from former colleagues.

Learning from experience, Donaldson always plans the outcome three ways. There’s what he thinks will happen, what

might happen and then what if it goes terribly wrong.

“The thing you learn as you gain experience is, you’re so focused on the big ones they almost become easy,” Donaldson said. “A lot of times when stunt guys get hurt it’s on the smaller stunts because maybe your focus isn’t as it should be.”

of Motion Pictures but serves as it’s president, currently on his third term and final year. Formed in 1961, the association is one of four stuntmen’s associations in Los Angeles and the oldest of its kind.

“I probably enjoy it more, looking forward to going to work, because with experience comes confidence,” Donaldson said.

Fellow Stuntmen’s Association member Grant Jewett has known Donaldson for five years, not only as a colleague but he described Donaldson as a fantastic yet “introverted” individual.

“He’s always thinking. He’s somebody that I can call, especially with matters regarding the Stuntmen’s Association,” Jewett said. “We have similar mindsets on not just the business but the way our brains process information.

Due to his work ethic and preparedness, Donaldson has never been seriously injured, only breaking small bones in his hands and feet.

At 58, Donaldson has decided against taking certain jobs and stunts he used to do at a younger age.

He no longer has the desire to travel to certain destinations or participate in a car hit, unless he is the one that’s doing the hitting.

These days, Donaldson is not only a member of the Stuntmen‘s Association

A stuntman for more than 30 years, Donaldson is grateful for the opportunities that have presented themselves during his career, and is proud of what he has been able to accomplish so far.

“My career has revolved around living in a fantasy world, the things we get to do, the places we get to go, the things we get to see,” Donaldson said, “I’ve been blessed with an incredibly good career. I’ve been fortunate enough to work a lot, on a lot of big movies.”

“

I probably enjoy it more, looking forward to going to work, because with experience comes confidence.

-Mark Donaldson

It’s seven in the morning at Willow Spring International Raceway, in Big Willow, California. The sun starts to heat up and the sound of roaring engines stupefies one’s hearing. Crowds of spectators as well as drivers wearing colorful racing suits gradually fill up the place.

Dane Remo steps out of his little red Mazda Miata with a casual demeanor, wearing jeans, Vans and a t-shirt. He checks the air pressure on his tires before the mandatory early driver’s meeting. After a little chit chat with friends about the conditions of the track, the voice of the announcer requests the Miata class to get ready for the first round.

Remo prepares for his first race session of about 20 minutes

against 15 other Miatas. After the showdown, he gets out of his car and goes straight to the time lap scoring sheet, but his day is not over yet. In an hour he’ll be racing again, looking to beat his previous record.

From the moment you meet him, his charismatic, cool personality shows the kind of laidback dude that Remo is.

His friendliness automatically makes people around him comfortable. That is the same way he approaches driving, whether it’s in the racing tracks, or the Little Tujunga canyons in Sylmar, California, where Remo loves to drive his Miata. His audacious, yet responsible way of driving makes him stay away from any type of racing outside the tracks. Instead, if he is itching to go for a spin,

he’ll go to the canyons, where the spirit to go fast comes naturally.

Remo handles the race track and canyons with ease, despite his car being more than 20 years old.

The tranquility in which he takes the wheel is a clear sign of his talent as a racer. The 22-year-old communications student at CSUN has an uncompromised, yet humble charm that makes him likable among his peers.

The San Fernando Valley native got into racing cars three years ago through some friends.

“I started driving in canyons and mounting roads.” he said, driving a Mazda 3.

Remo gradually gained the respect of other drivers who have more experience on the tracks.

“He’s a pretty good driver, really smooth. He is progressing a lot faster than other drivers,” said Michael Hillow, one of Remo’s best friends, who is also a driver.

The two car enthusiasts met three years ago in the car scene, and from there they became close friends.

Remo’s eagerness to become the best in his circuit has also impressed other drivers.

“He’s a pretty cool guy. Very fast,” definitely very fast.” said Dominic Guo, who started racing about the same time as Remo did.

Even though he is in the amateur, or enthusiast, class, and his car has few

alterations in the engine, Remo is considered one of the fastest in his category.

The Miata racing community has grown immensely in Southern California. It has gone from only about 10 drivers to approximatly 40 today, according to Touda Bentatou, organizer of the “Extreme Speed Roadster Cup,” a Miata only series.

“Right now, we are only in Southern California. We’re trying to get up north and we’re working with one of our sponsors to potentially do something in British Columbia,” said Bentatou, who’s been working with Extreme Speed Track Events for the past three years.

The company’s objective is to create a friendly, yet competitive atmosphere among car enthusiasts.

Drivers are required to register at a cost of about $120 per race.

It’s his uncompromising, and relaxed approach to racing that makes Remo so good.

“I mean I wouldn’t say I practice but a lot of times, like every couple of tracks, I make sure my maintenance is good, like oil changes and stuff,” Remo said.

Remo’s driving skills are natural because he doesn’t train much.

“I don’t really practice for a race because the race is kind of practice for driving,” he said.

In the past two race events he’s had. Remo has made the

podium, once winning and the most recent taking third place. It’s the fun and excitement for racing cars, that keeps this young driver competing.

For Remo, racing in a more professional level is uncertain.

“Who knows? It’s a lot of fun right now. I feel like once I get older, or get a better job [I’ll stop],” Remo said.

Until he’s forced to make the choice between burning rubber and the responsilibities that will come with adulthood, Remo said he will continue to spend his days behind the wheel.

For now he’s just having fun enjoying the thrill of the

race and giving everyone a good run for their money.

“ I don’t really practice for a race, because the race is kind of practice for driving.

-Dane Remo

The lifter starts almost sitting down; knees bent, hands on the dumbbell in a wide grip.There is an explosion upward as the lifter brings the full weight above his head in one motion. He stands there with his arms extended, balanced. This isn’t lifting to look good. This is utility over aesthetics. The lift is called the snatch, and when you see it done you see the name is fitting. The sudden and almost violent motion moves the weight from the floor to directly over the lifter’s head in less than a second.

This kind of lifting is designed to do one thing, push the human body to lift as much as it can. In Olympic weight lifting, the top lifters end up competing globally for the gold, but that is an extremely difficult ladder to climb.

The dedication and sacrifice these athletes are putting in the weight room places them in a high risk reward situation. The sustainability of this as a career is limited even at the peak. Why put themselves through this?

Paul Aya, 24, is a personal trainer at Powerhouse Gym in Chatsworth. Aya got into weightlifting by being offered a job training high school students in Calabasas.

“I knew how to lift weights, just not the right way, so through working with the trainers and kids I got to learn about cleans,” Aya said. “The clean is one of the Olympic movements, and I’ve been in love with them ever since.”

The clean is similar to the snatch, only broken down into two motions. First, the lifter bolts up and brings the bar above his chest and under the chin. The jerk comes from the arms raising the weight above the head for a brief moment.

The clean and jerk and the snatch are the only for which that Aya trains. Aya started training in a friend’s garage before moving into bigger gyms. Eventually Aya decided to bring the gym home and sold his BMW to pay for his set up where he now trains.

“It’s nothing like your typical gym s***,” Aya said. “It’s the two movements and then auxiliary movements from the two and strength work. Squatting, pulls, snatches, and clean and jerks from the blocks.”

Lifters prepare for local competitions

that are designated as official USA Weight Lifting meets. Numbers are recorded and lifters move up to competitions on a larger scale. Getting on the national stage is a precursor for an Olympic appearance. Each weight category has goals lifters must hit, and they get three attempts for each lift. For Aya’s next meet he’ll have to put up 293 kg or 645.9 pounds.

James Furedi assists Aya with his workout program. The workout is intense to build up to the day of competition, followed by rest before training begins for the next meet.

“It’s very calculated because you have to plan your attempts,” Furedi said. “Common overuse injuries that you can find in weightlifting are the back and the

knees. You’re squatting and lifting from the floor a lot more than a typical person.”

Furedi said that a careful program, along with things like stretching and keeping joints mobile, limits injuries.

“A lot of weight lifters take great care in their recovery. Massages, hot baths, things to keep muscles from stiffening up,” Furedi said.

Coaching others in the sport is something Furedi looks forward to, but he said that his friend Sean Rigsby began training with him, and Aya dedicated himself. Rigsby, 26, is a national bronze medalist and a professional weightlifter with team MDUSA, Muscle Driver USA, the reigning national champions in weightlifting.

Over time, intensive training can wear parts of the body, such as the back and the knees, which can be pushed to their limit. All the time spent with the weights compounds the stress on the joints and muscles.

“Weightlifting actually has the second lowest incidents of injury per 10,000 hours. Soccer has the highest,” Rigsby said. “It’s usually a lot of little minor things. Most of the injuries in weightlifting are chronic, like tendonitis.”

Aya decided to begin work in construction and has only in the past few weeks been able to continue training.

“I want to make it to nationals, but since I got this new job I’ve taking it easy with the weights,” Aya said. “I’ve

already qualified for regional competition in St. Louis. It’s another step closer to nationals.”

In our pursuit of our passions, we may find ourselves at odds with the world around us. Aya is trying to balance his new job, and his drive to go further in the sport just as he strives to balance the hundreds of pounds he holds over his head with each lift.

Aya estimates he’s about a year away from getting to nationals. “I want to be recognized for something, and Olympic weightlifting demonstrates your overall athletic abilities in every other single strength sport,” Aya said. “If I wasn’t working manual labor you better believe I’d be on top.”

Iwant to start by thanking my staff for being incredibly supportive this semester and for sticking with me until the end.

Thank you for getting “Dirty and Dangerous” while pushing yourselves out of your comfort zones and trying something new.

I hope you all are able to walk away with something life-changing from this experience.

But most of all I would like to thank my professors Jill Connelly and Jeff Favre for continuously fighting for our Media Arts Department to continue to allow students, myself included, the opportunity to create a piece of history at Pierce College.

If a year ago, someone had told this unsure, frightened girl that she would eventually become the features editor for the Roundup newspaper and the editor-in-chief for The Bull Magazine, I never would have believed it.

I am happy to say that I have grown in many ways as a writer,

Sincerely,

Kitty Rodriguez

Kitty Rodriguez

a journalist and as a student in the Pierce journalism program. Thanks to my parents for teaching me that you can never work hard enough and that you should never take no for an answer.

I want to share a little bit about how we came up with the theme “Dirty and Dangerous Jobs and Hobbies.”

A show on the Discovery Channel called “Dirty Jobs,” hosted by Mike Rowe, fascinated me.

Nicolas Heredia came up with the dangerous aspect, and before we knew it, there it was.

Magazines are a wonderful marriage of words and images. I wanted to make sure that the photos you see in these pages are not only eye catching, but that they they can tell the story as much as the text.

This magazine is dedicated to all of my professors who taught me to think outside of the box. I hope this makes them proud.