IV. A Speculative Scenario

In a world where technology appears to hold the answers to most of our pressing challenges, addressing the issue of climate change requires the foundations of architecture and urban planning to re-engage with the natural sciences and reconnect with the fundamental principles underpinning their respective disciplines. The primary aim is to alleviate the adverse impacts posed by the natural environment and ensure optimal living conditions in diverse regions through core principles such as strategic site orientation, efficient ventilation systems, and effective lighting management.

It is important to understand that the objective here is not to solely criticize modernity and technological progress. In fact, technological advancements have played an indispensable role in ensuring our survival. From the discovery of fire, enabling human habitation in harsh climates, to the advent of modern medicine, technology has significantly contributed to our progress and well-being.

However, the challenge lies somewhere in the transition from modernity to postmodernity, which has obscured our awareness of the materiality of our existence. By emphasising our cultural aspects, postmodernity has also diminished our capacity to act effectively in a world that remains fundamentally non-human. It is crucial to strike a balance between the benefits of technology and the preservation of our connection to the natural world.¹

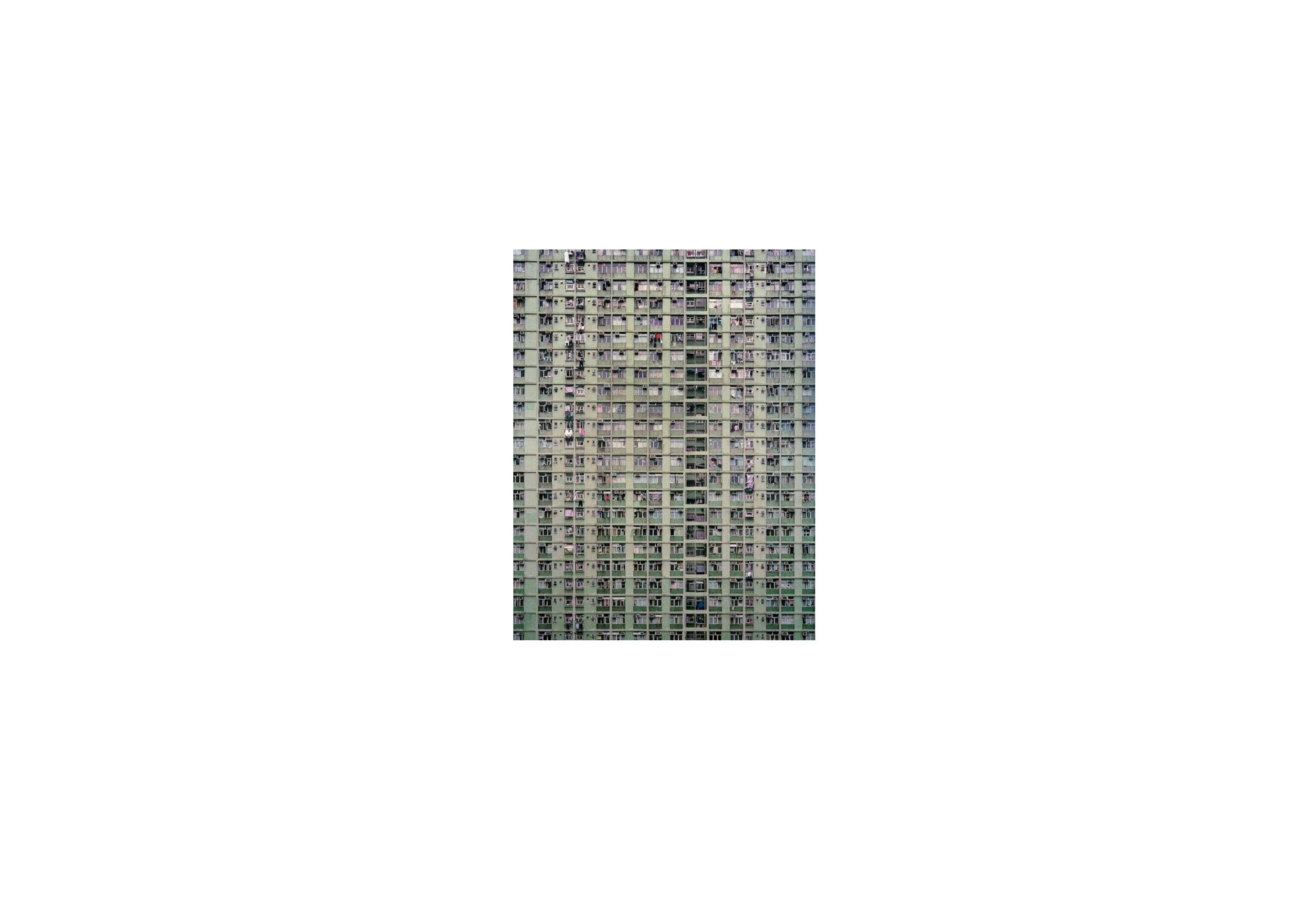

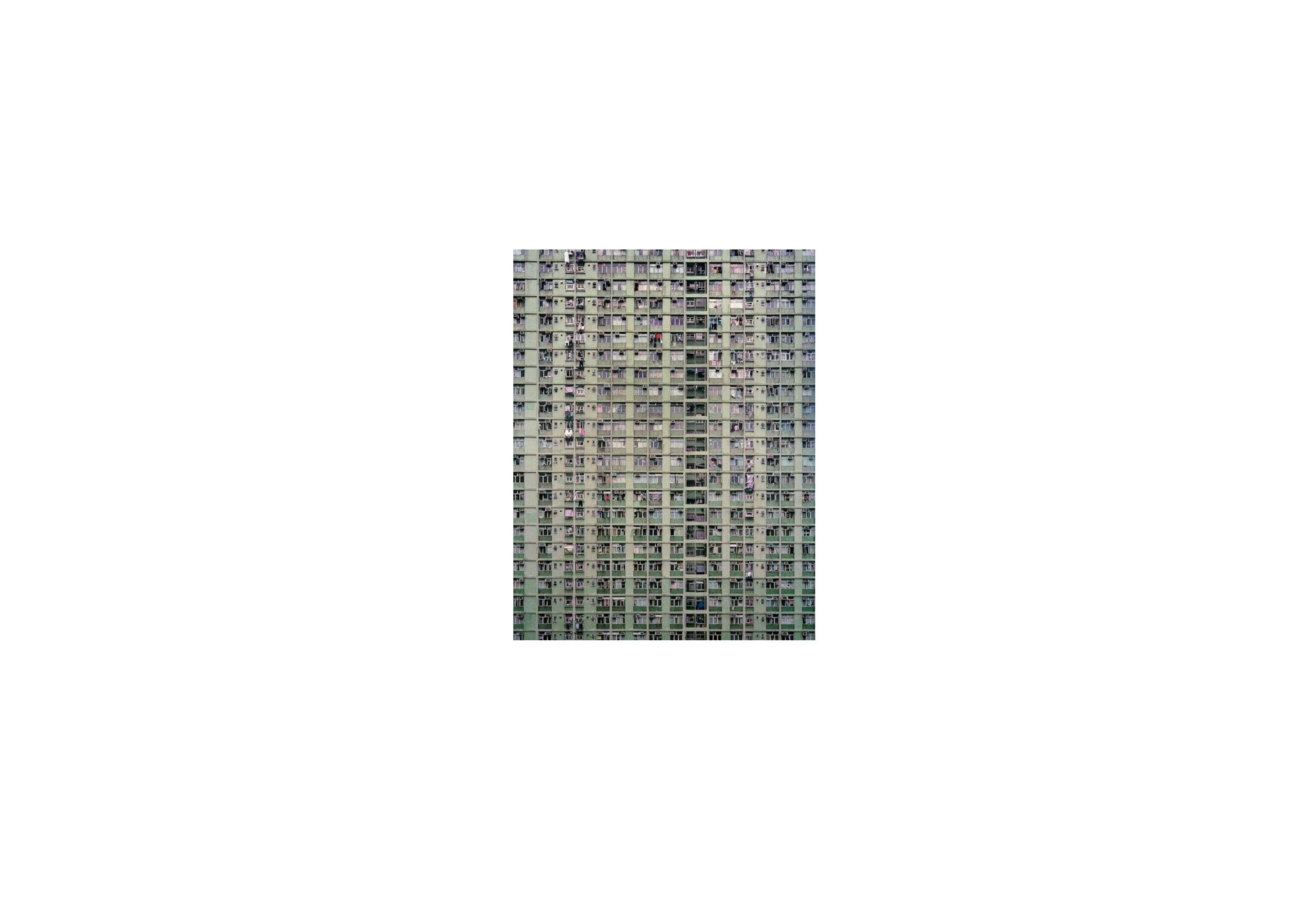

“front facade elevation many air conditioners on the top of a building, in the style of zeiss ikon zm, hurufiyya, post-modern installation artist, nouveau réalisme, majestic ports, brooding mood, grid-based” A.i Generated

20

Scenario

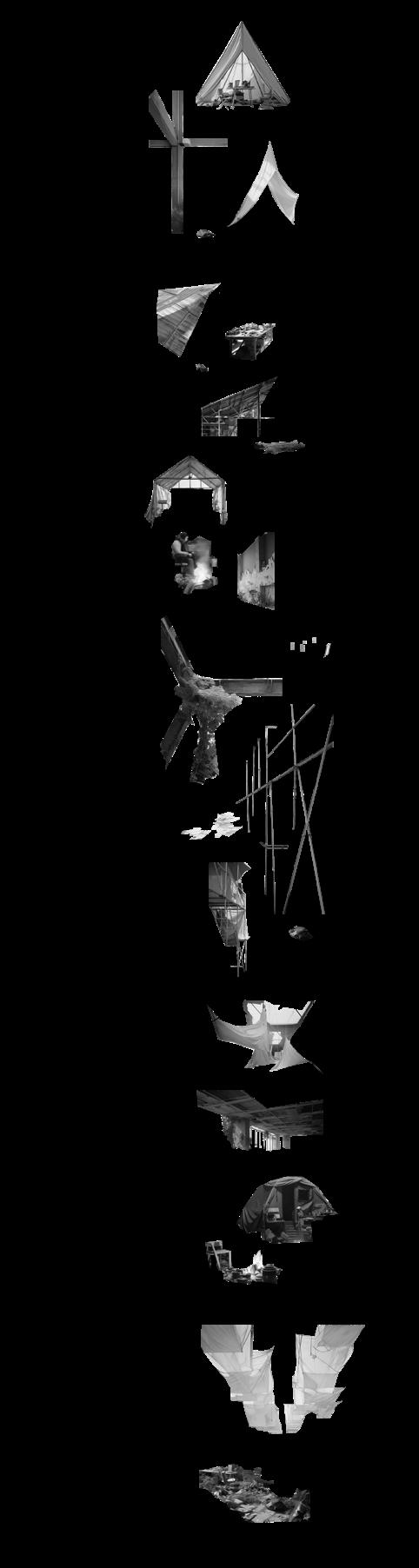

The speculative scenario below has been illustrated using AI. To understand the to Text to Image exploration please see the A.I Experiments booklet “Rebirth of Low-Tech Architecture

“In a world where technological progress has often led to convenience and comfort, our reliance on devices like heaters and air conditioning systems has become ubiquitous. These technologies have allowed us to manipulate our immediate environment, striving for a perfect and consistent climate within our buildings. However, this dependence has come at a cost. Our over-reliance on these systems has disconnected us from the natural environment, contributing to resource depletion, energy consumption, and a sense of detachment from our surroundings. We sacrifice our connection to the very landscapes and climates that define our sense of place and identity.

In a speculative near future, technology has evolved into a new form of spirituality, resembling a form of religion. People gather in quantum computer temples to connect with the AI deity, seeking guidance, knowledge, and a sense of purpose. These digital sanctuaries have replaced traditional places of worship, reflecting the profound role that technology plays in our lives. As we immerse ourselves in this digital faith, questions arise about the balance between technological advancement and the preservation of cultural identity.

21

booklet

A.I Experimentations

Scenario

In the midst of an unprecedented economic crisis, the technological progress comes to a halt, as the once abundant resources become scarce, and the intricate network of global transportation grinds to a standstill. Commercial architecture, once a symbol of boundless innovation, is silenced. Empty skyscrapers loom like echoes of a bygone era. Nature seizes the opportunity to reclaim its dominion, as lush greenery and organic life slowly infiltrate the concrete jungles. Amidst this transformation, questions arise about the legacy of technology and the resilience of nature, sparking a profound reconsideration of architecture’s role in our world.

“Suburban man falling asleep near his lawn mower, pulling a section of his Sunday paper over his head, thus re-enacts the birth of architecture.”

Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture without Architects

Amidst the decaying remnants of once-thriving skyscrapers, a beacon of hope emerges. Enterprising squatters repurpose floors within these abandoned structures, transforming them into spaces of communal learning, collaboration, and architectural experimentation. Their collective ambition is to rediscover the essence of architecture – the provision of shelter – through the lens of fundamental low-tech techniques. The once gleaming facades of high-tech dominance now echo with the sounds of hands-on construction and shared knowledge. In this inspiring movement, the aim is clear: to craft an architecture that resonates with its inherent purpose and finds equilibrium with the natural world. From the detritus of the past, these pioneers reimagine a future defined by adaptive reuse, forging a new vernacular that echoes the harmony between humanity and its surroundings.”

22

Scenario

Technology has become a religion. After having desacralized everything, it has become sacred itself. Criticizing technology, science, research, and growth is now forbidden - Jacques Ellul12

23

Scenario

Render of the Techno-temple

24 Scenario

25

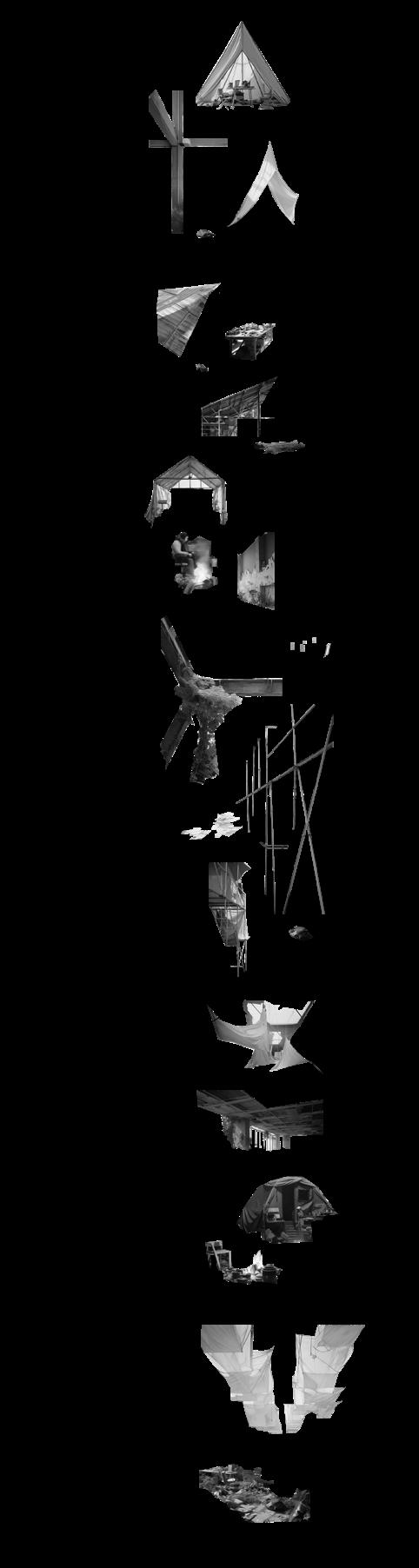

A.i Generated Scenario

In this speculative scenario, we navigate the landscape of architectural concepts, questioning the current trajectory of the field. The scenario alows to set up a scene that unfolds three distinct focal points. The first, a critique of architectural homogeneity spawned by technological progress. The second, on our blind addiction to technology, emphasizing the potential perils of unchecked reliance, particularly in the realm of artificial intelligence. The third exposes an ongoing crisis—the adverse impact of the built environment. The global transportation of materials, extraction of precious resources, and our overdependence on controlled internal climates.

The scenario culminates in an exploration of low-tech architecture, pushing the boundaries to an extreme. While this extreme serves as a thought experiment, it holds valuable lessons that could inspire innovative solutions for present challenges. The overarching goal is not only to unearth architectural survival strategies but also to discover new possibilities applicable to our current context.

The stage is set for a critical examination of our technological dependence, imbued with irony. It paints a scene, portraying the worst-case consequences of our reliance on technology, distilling the various critiques into a single, impactful moment. Through this exploration, the scenario not only challenges the status quo but also encourages the consideration of alternative paths and innovative approaches for a more sustainable and resilient architectural future.

26

Smooth Montages

Reflection on the scenario

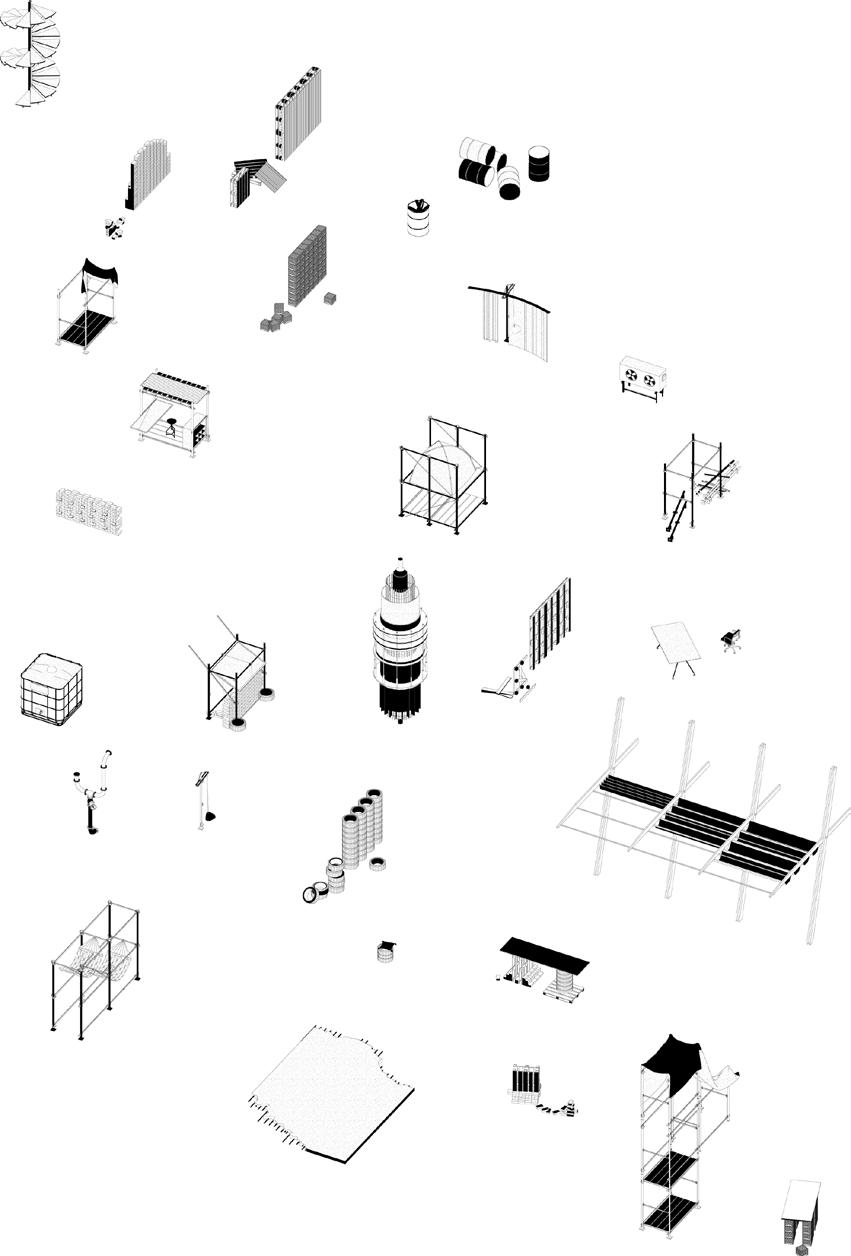

Extraction of the A.I generated elements

27

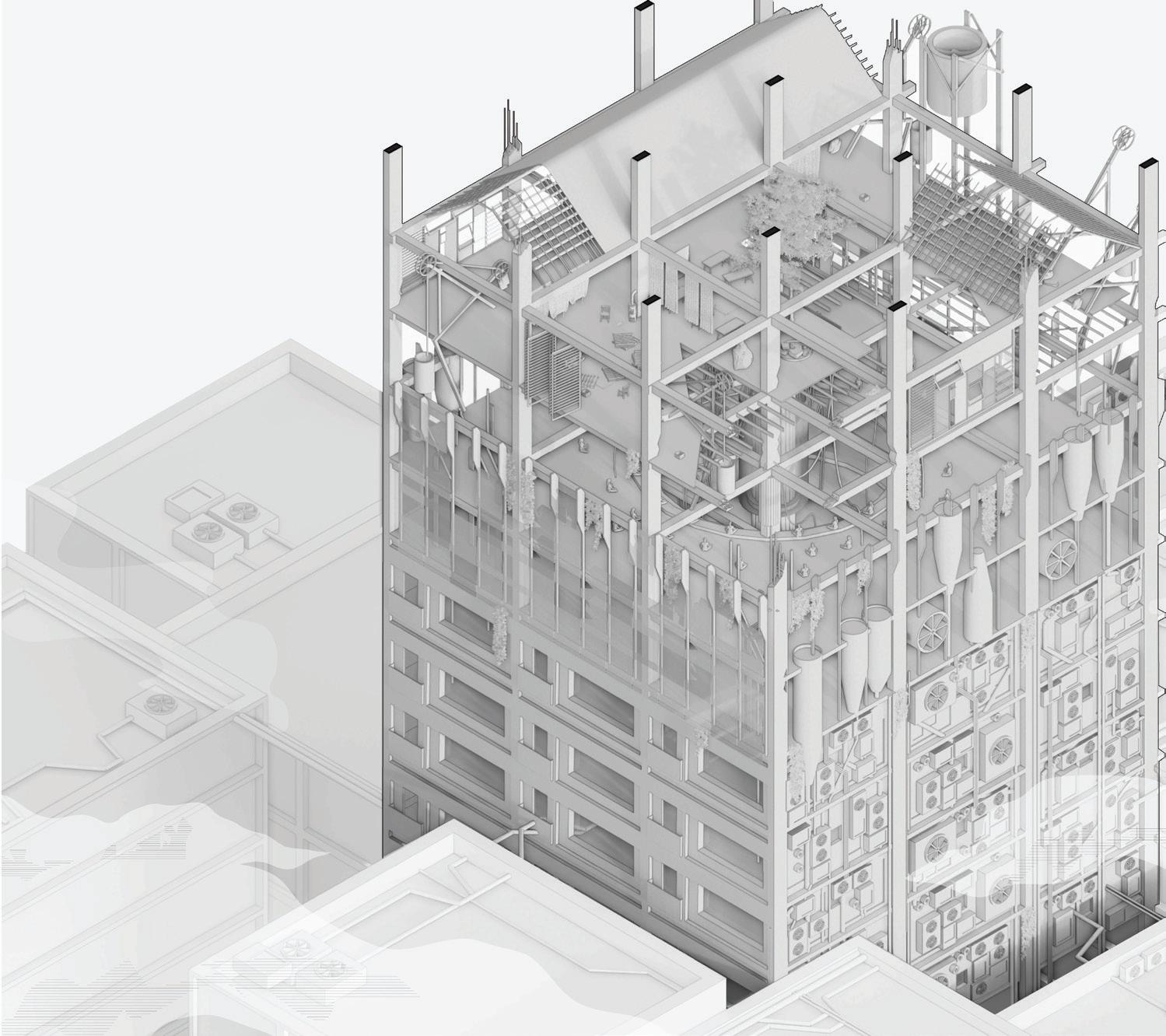

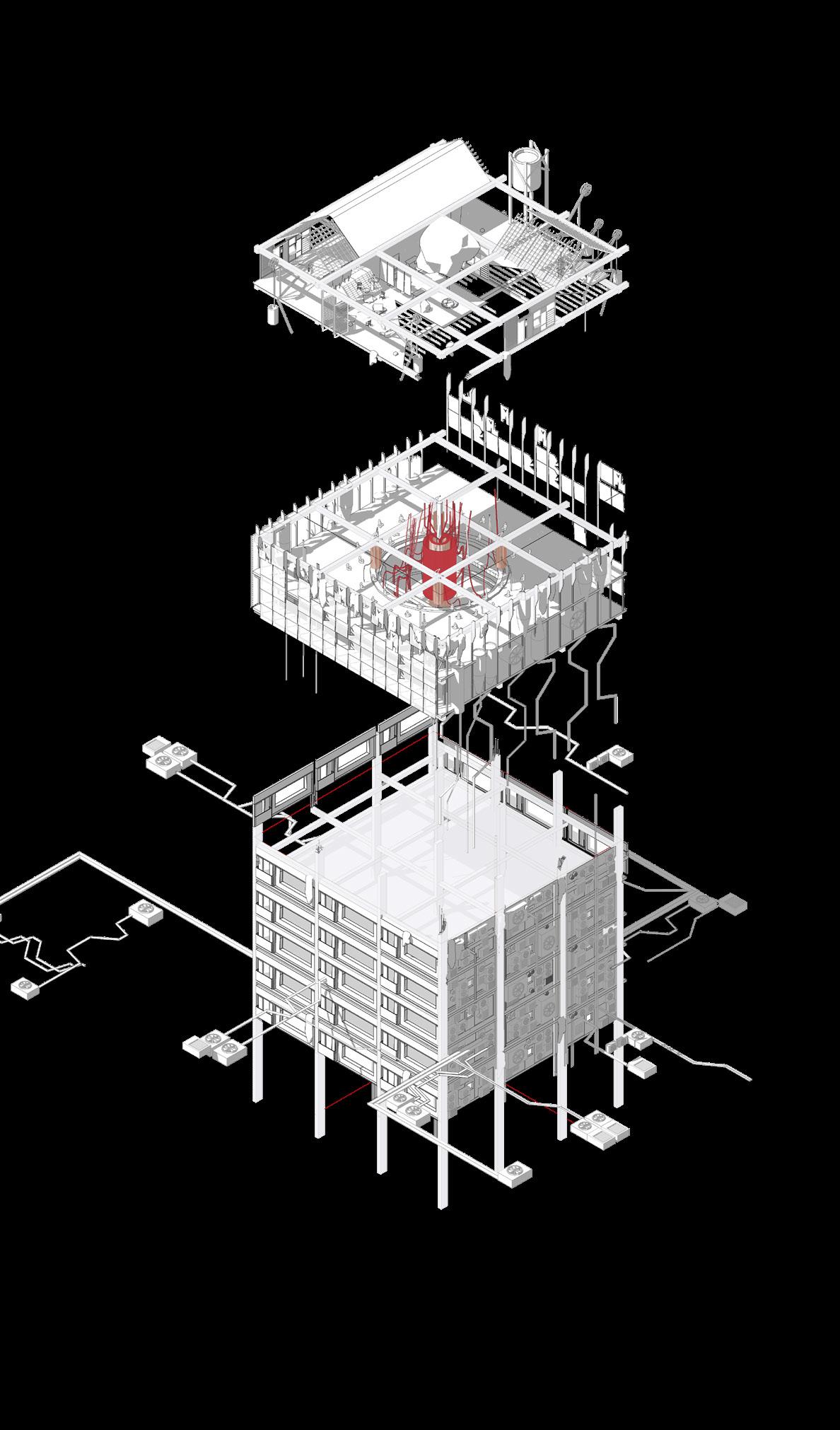

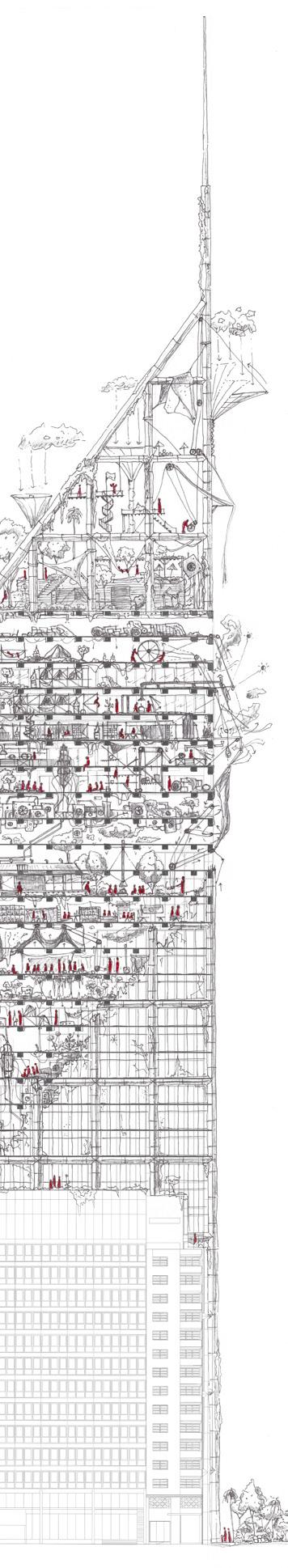

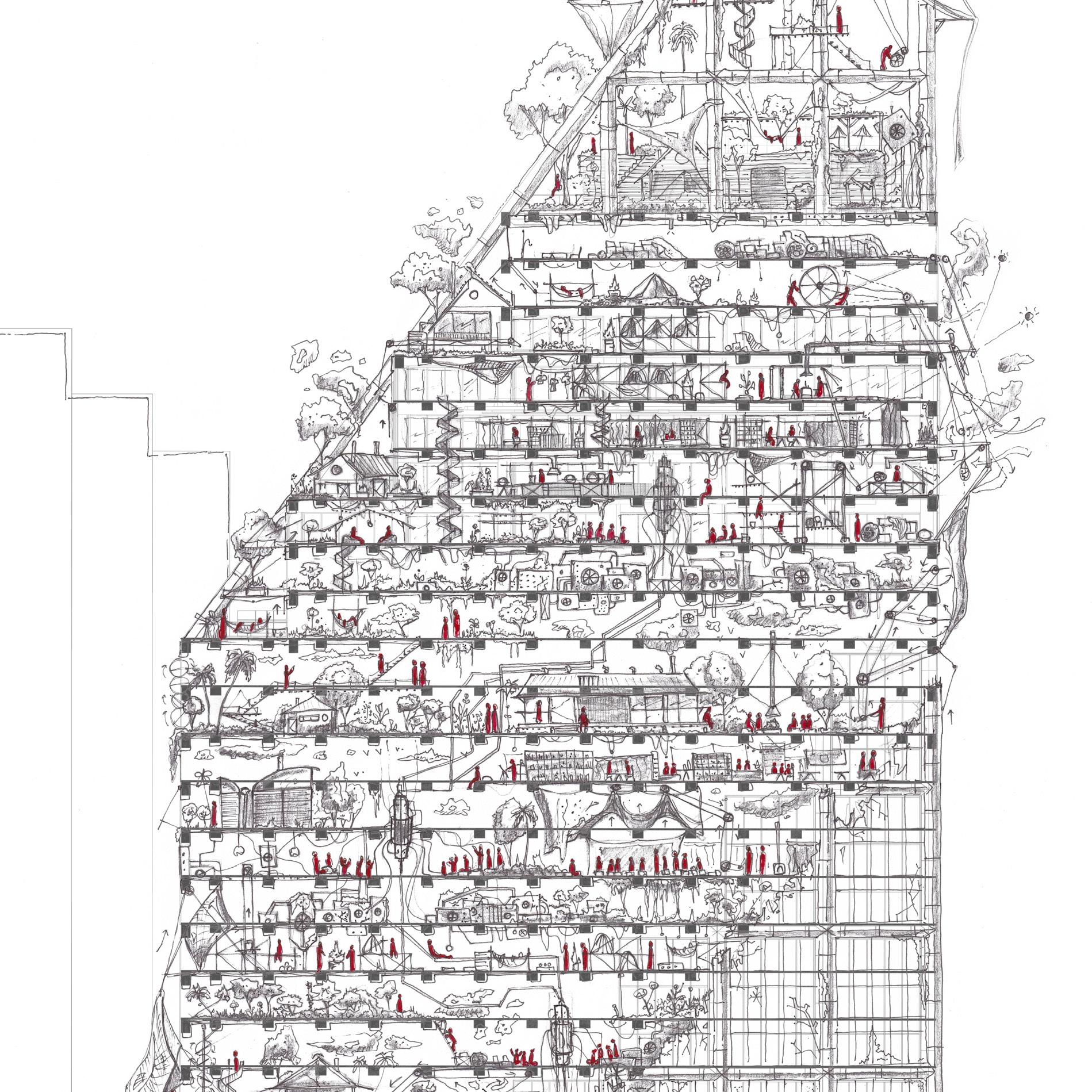

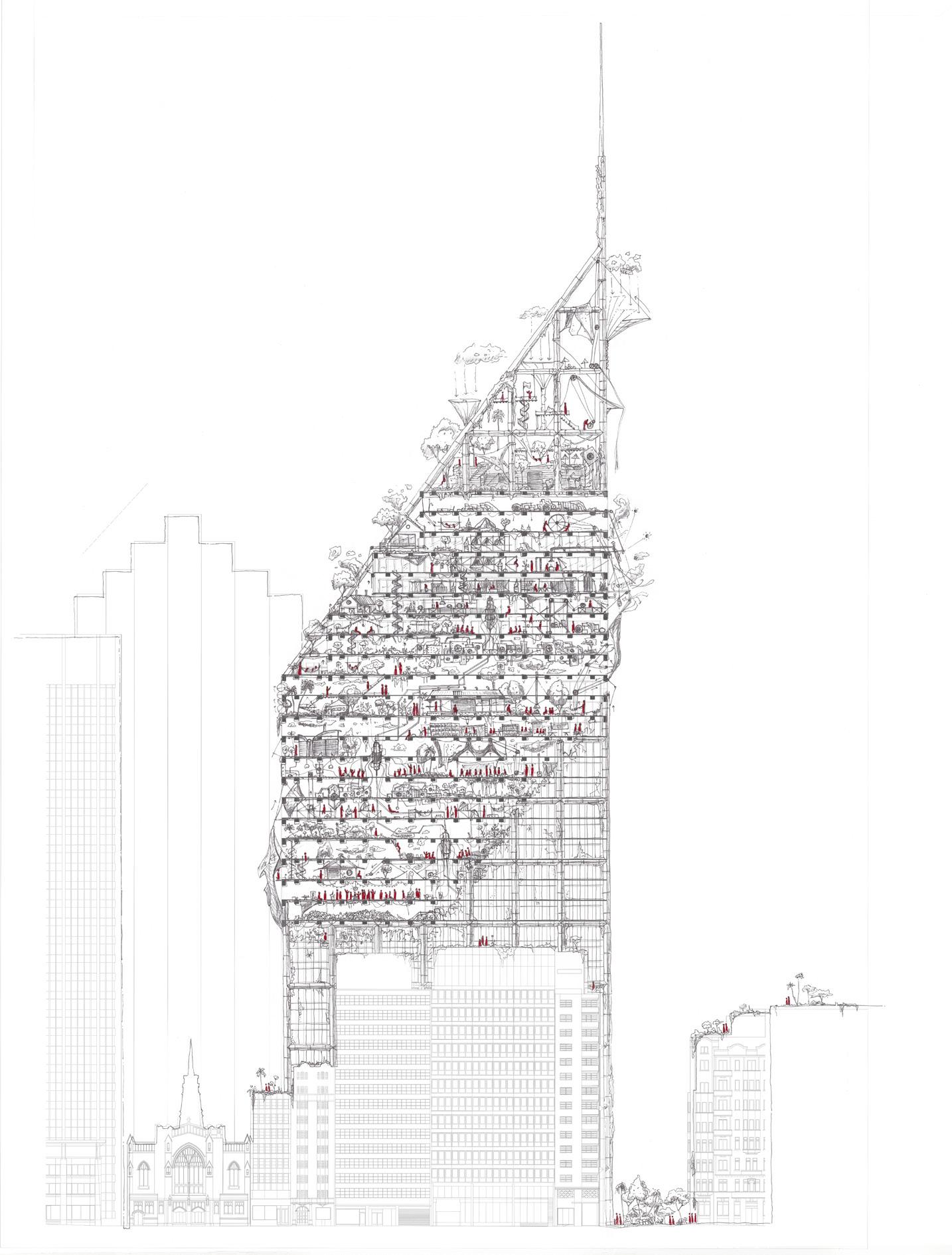

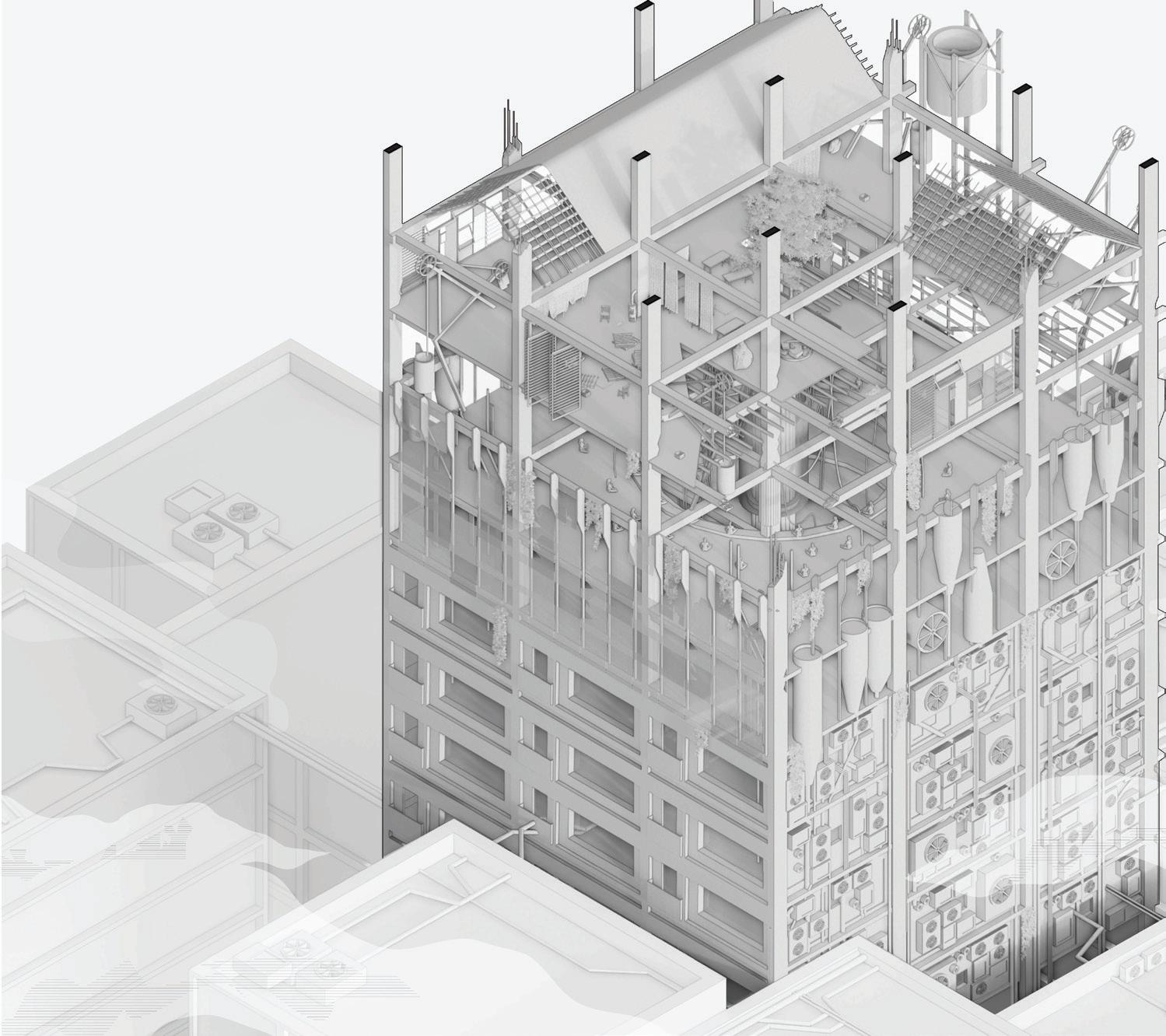

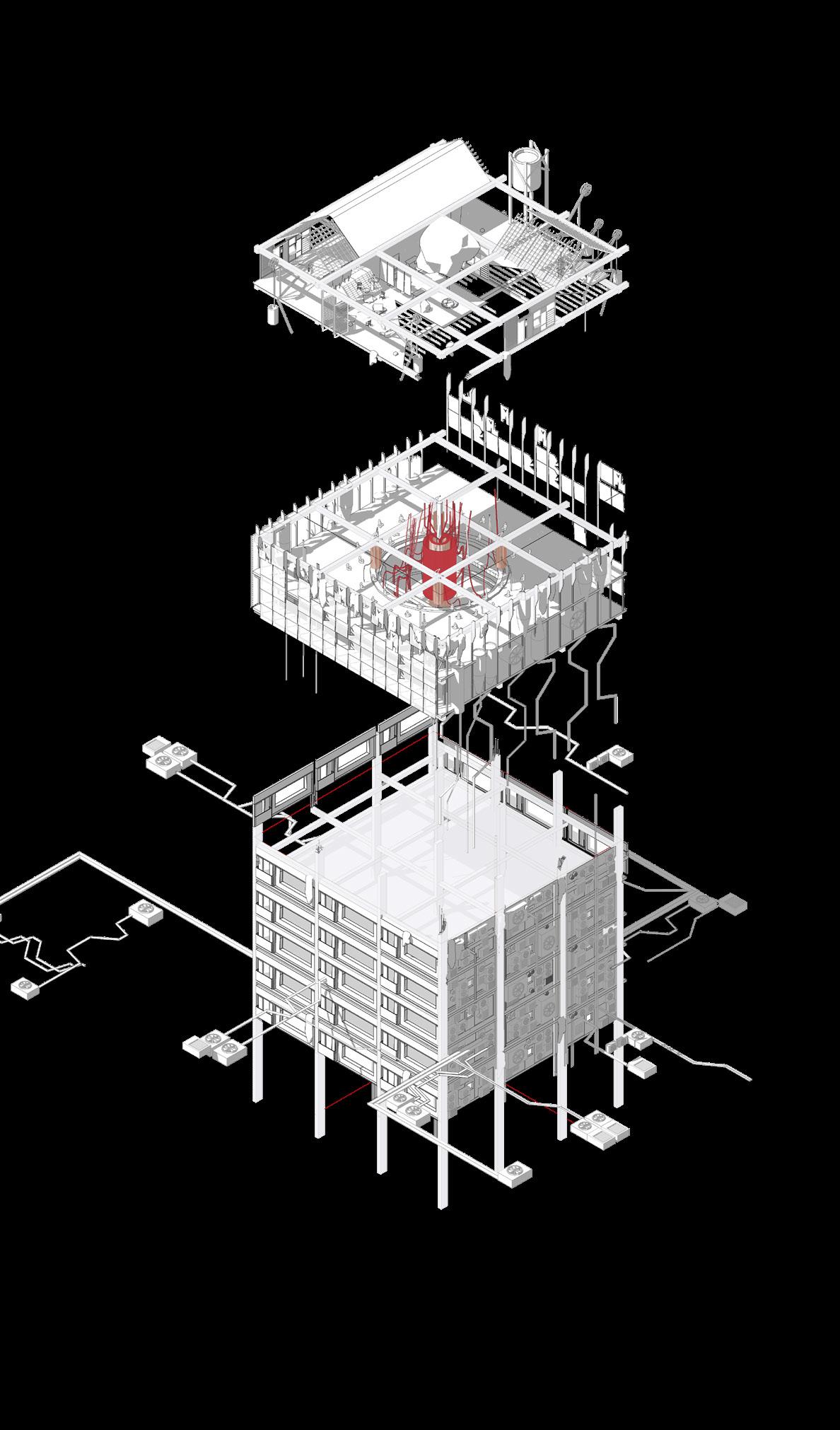

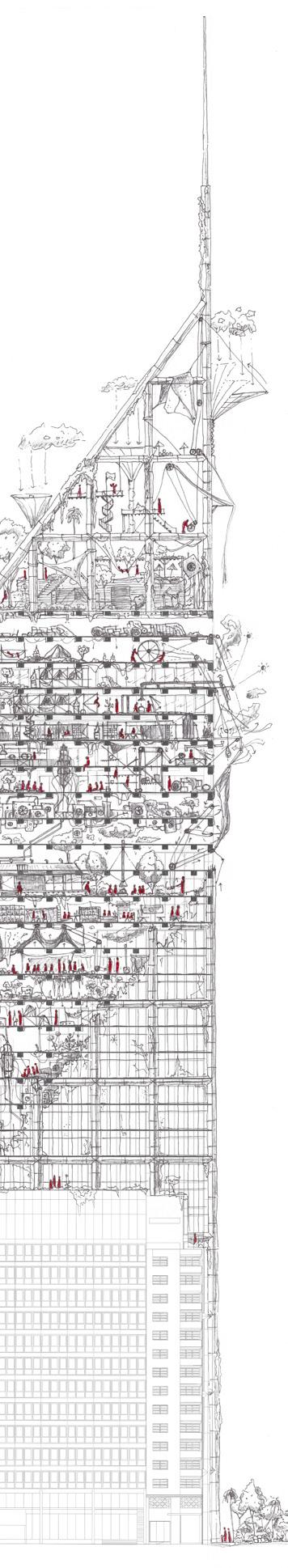

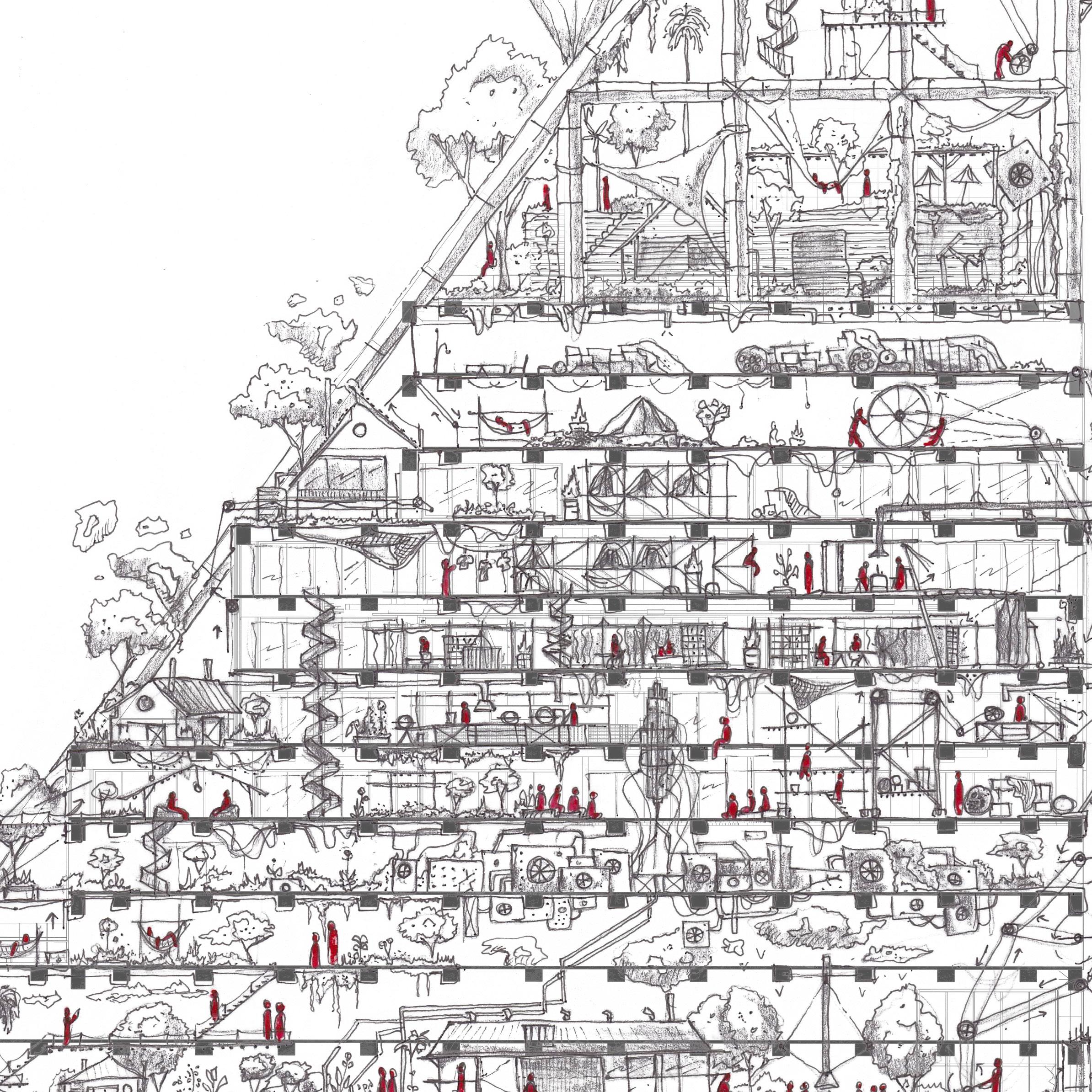

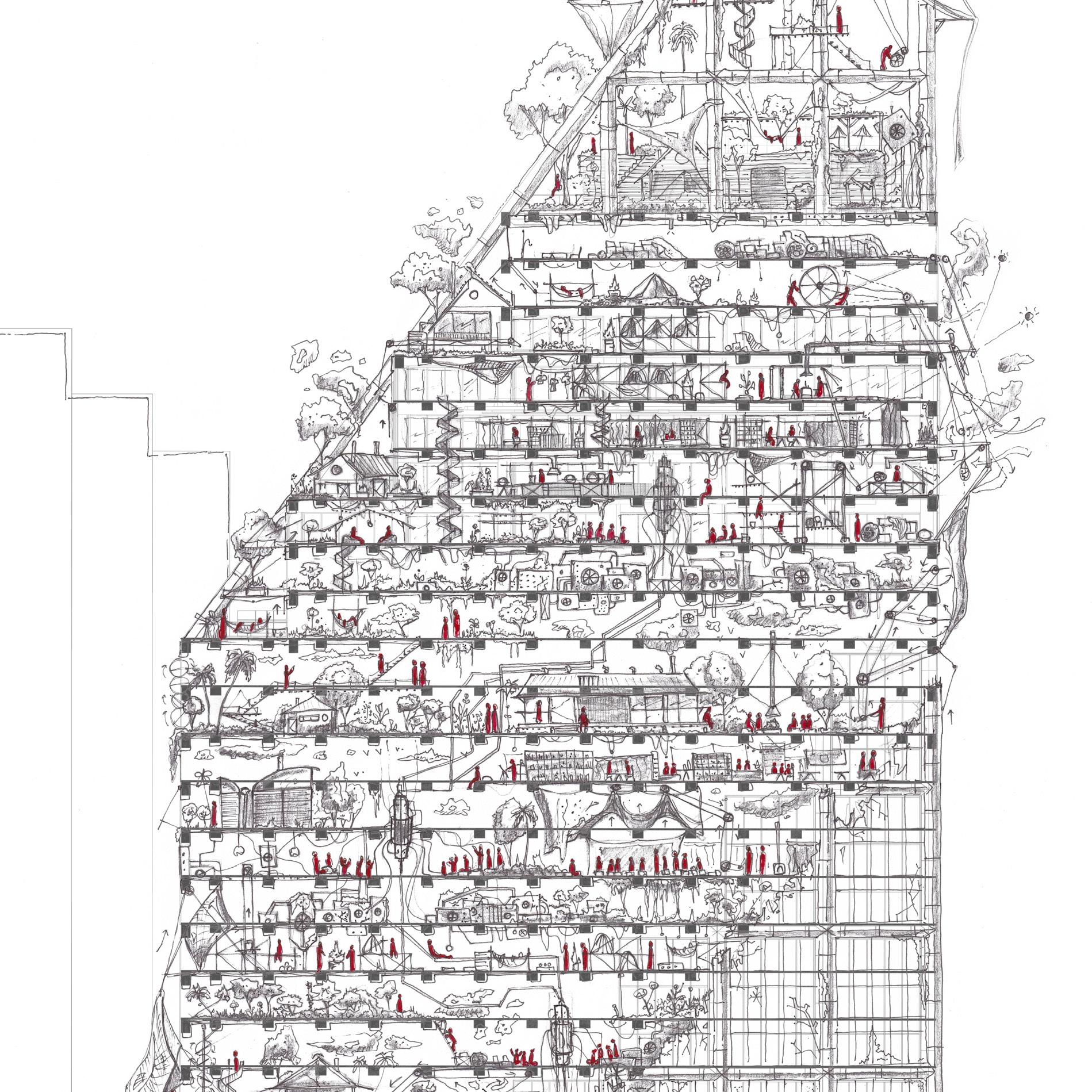

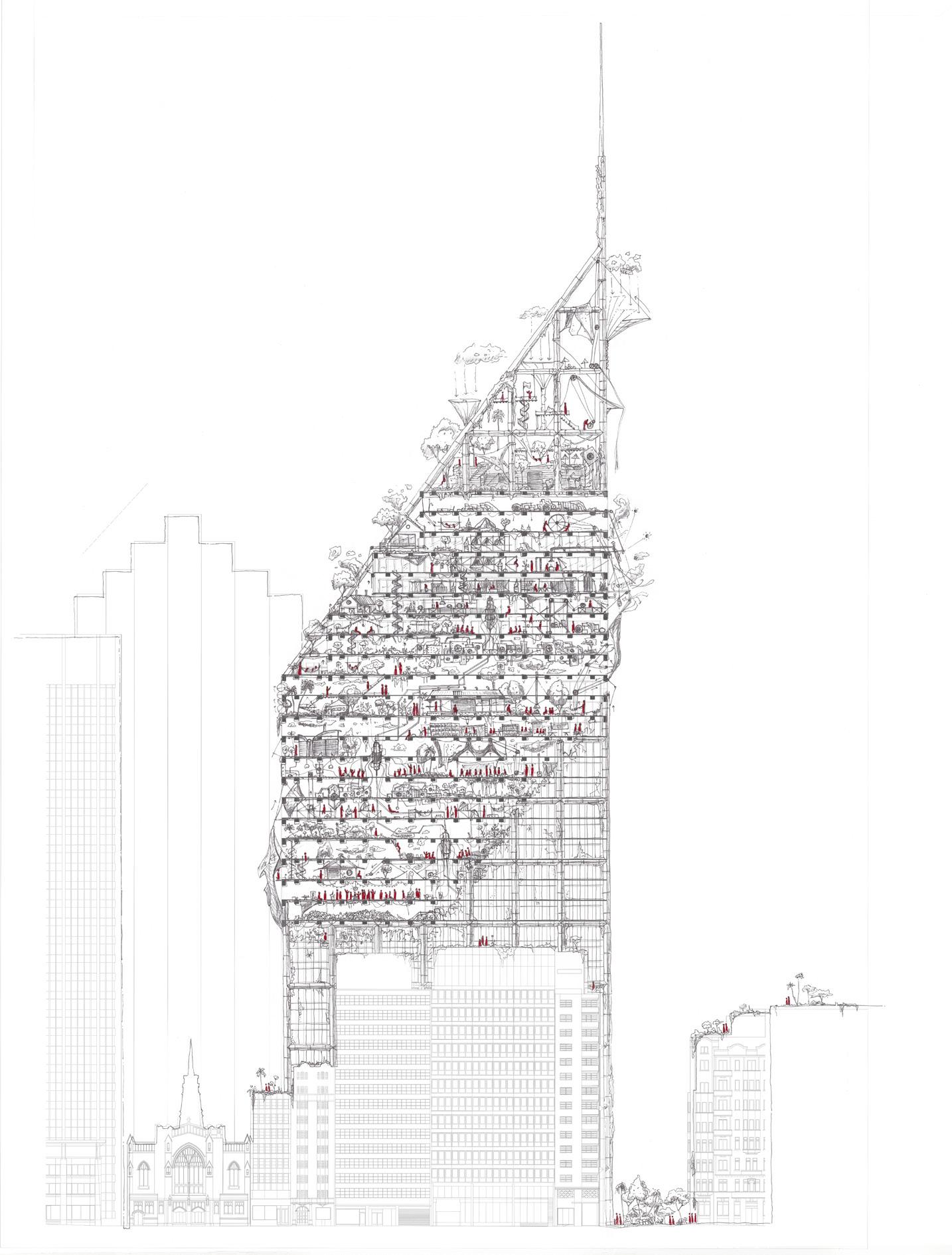

V. Opportunities

To encapsulate the essence of this speculative scenario in a singular architectural manifestation, a tower design has been conceived. This structure serves as a visual narrative, articulating the evolution through the three primary architectural epochs discussed herein. The first epoch signifies Modernism and its global replication, fostering architectural homogenization and a dependence on technology, symbolized by a façade of repetition and a formidable wall of machinery. The second epoch encapsulates the contemporary high-tech era, projecting into the speculative future with techno-temples. The third epoch envisions a prospective architecture emerging from the ruins, a paradigm centered on finding shelter in a revitalized context.

The vertical narrative of the tower unfolds like a time-lapse of construction, inviting interpretation from bottom to top, symbolizing the chronological progression of Past, Present, and Future. Each tier tells a distinct architectural tale. The lower sections embody the echoes of the past, reminiscent of a bygone era when physical mechanics preceded electronic advancements. As the gaze ascends, the clash of times becomes evident, revealing a new world conceived in low-tech aesthetics, a deliberate reset that evokes the architectural traditions of yesteryears in a contemporary context.

28

Epochal Ascent: A Conceptual Tower

30

A Conceptual Tower

Epochal Ascent:

Epochal Ascent - Video

31

Epochal

Ascent: A Conceptual Tower

32

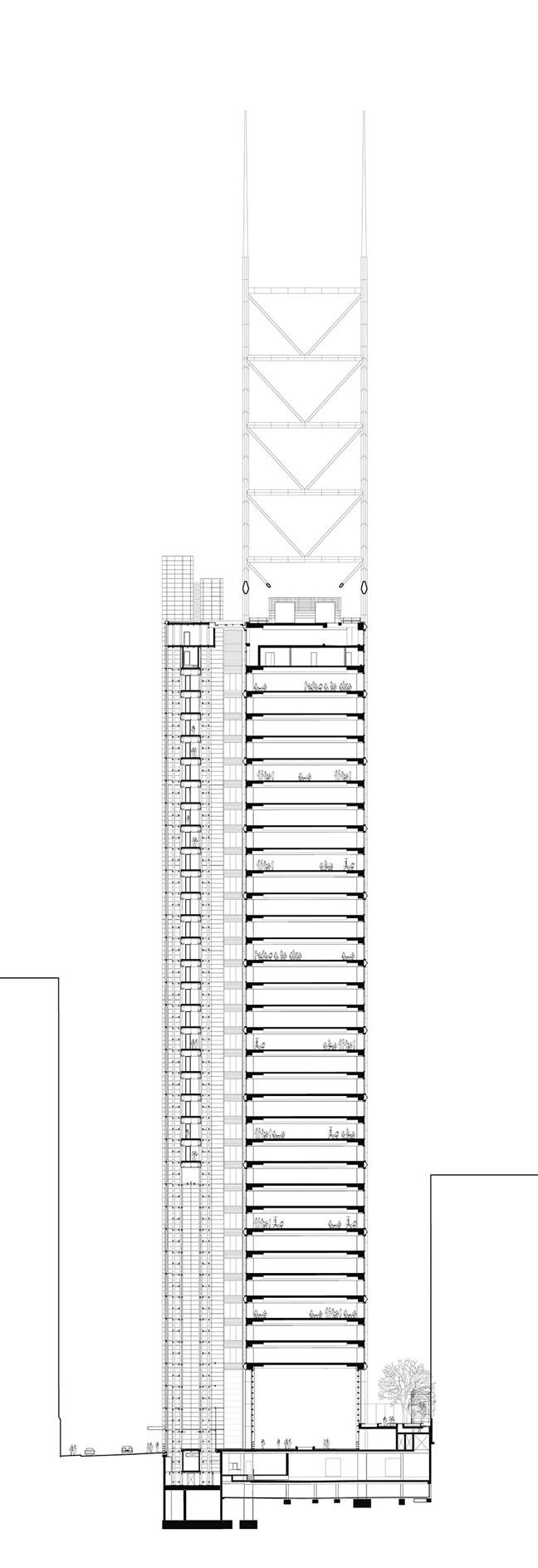

The Site

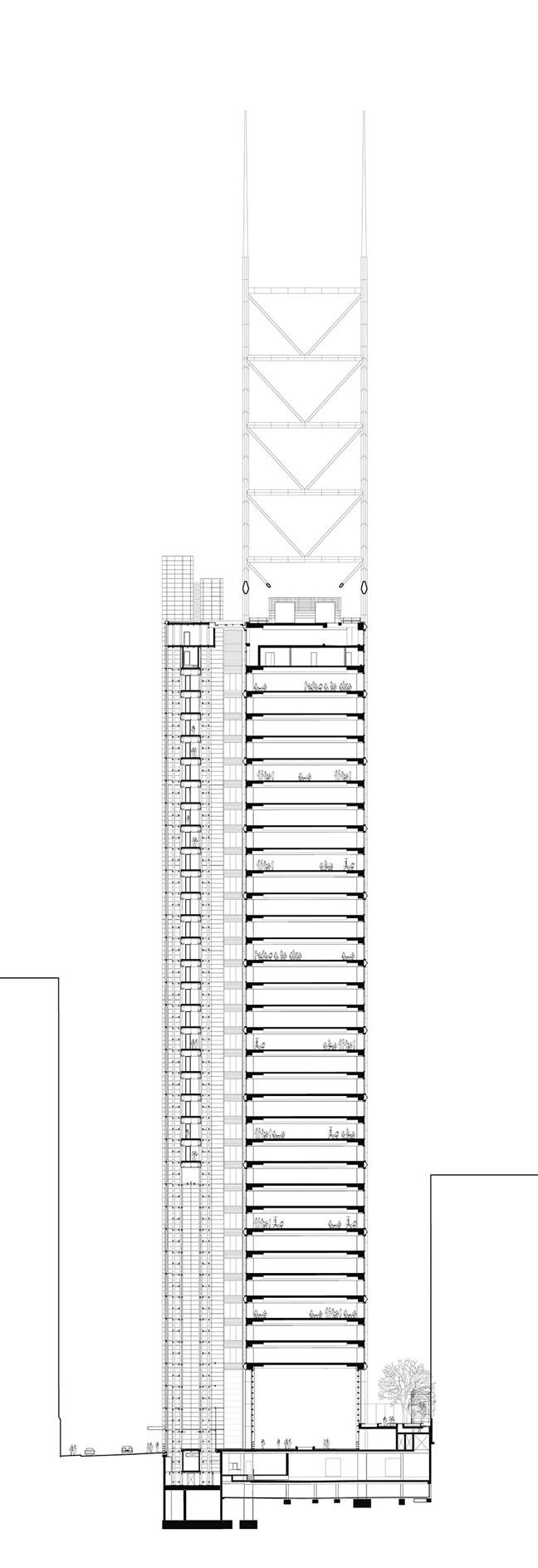

The Deustche Bank Tower situated at 126 Phillip Street in Sydney, Australia, standing at 240 meters . Designed by Norman Foster of Foster and Partners, the construction started in 2002 and was completed in 2005.

The design emerged from the site’s long and narrow dimensions, which didn’t suit a conventional central core structure. To address this, 64-meterlong and 21-meter-wide floor plates were positioned to the east of the site. These 21-meter widths are created in a single span, eliminating columns from the entire floor plate. This makes it the largest column-free span in any Australian office building, offering over 1,200 square meters of unobstructed space when standing from one end to the other.

To achieve this expansive floor plate without columns, the core was strategically placed on the west side of the site, providing solar protection to the main office areas.

33

Fig 3. Foster + Partners (n.d)

The Site

Fig 4. Interiors of the offices floor, Reacommercial.com (2023)

This building presented a compelling opportunity, symbolizing a pinnacle in technological advancements and designed by an internationally renowned starchitect. Its significance in the discourse on the globalization of architecture was noteworthy. However, it also serves as an intriguing case study, emphasizing the delicate balance between the positive and negative impacts of technology.

Despite its technological eminence, the building’s design offered an economic use of space, with relatively low and modest floor-to-ceiling heights that interrestingly complemented the envisioned scenario. Moreover, its narrative adds depth, with the shape being modified to prevent overshadowing the state library and parliament, showcasing a somewhat contextual sensitivity.

34

The Site

Fig 5: 126 Philip Street, Drawings by Foster + Partners (n.d)

35 The Site

VI.Low-Tech response

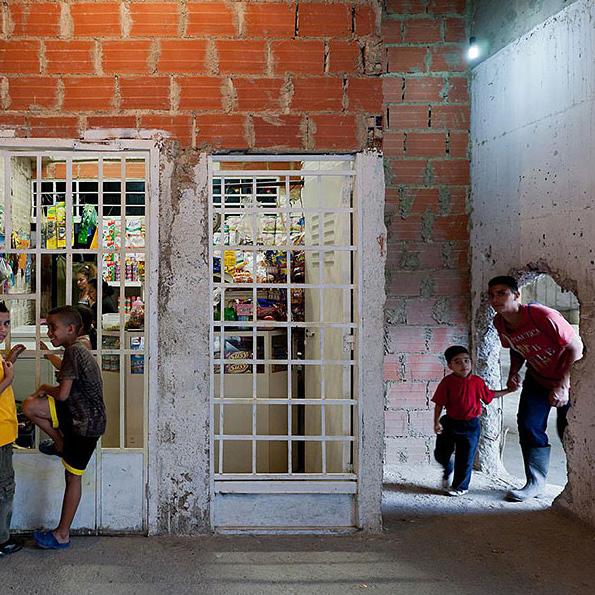

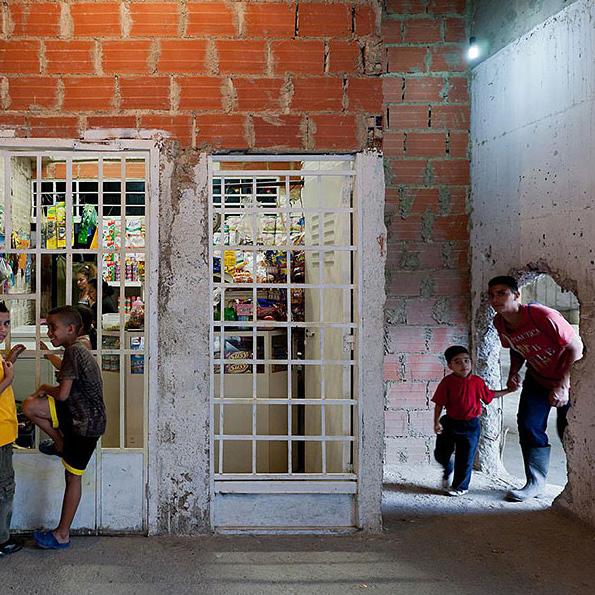

Case Study a: Tower of David in Caracas, Venezuela

38 Urban Camping

Fig 6: Iwan Baan. Torre David, Informal Vertical Communities (2013)

Case Study b: James Wines, High-rise of Homes

39

Urban Camping

Fig 6: Highrise of Homes, James Wines, Charcoal of paper (1981)

The Tower of David Caracas, Venezuela offers an interresting case study on how abandoned structures can find new, unexpected purposes within the urban landscape. It was originally designed as a financial center, it became an unconventional home for squatters due to economic challenges.

14

This adaptive reuse challenges traditional urban planning, highlighting the intersection of architecture and social dynamics. New openings are created according to the users need, the building adapts in-situ.

Non-sealed tower promotes user autonomy in creating sheltered spaces against the wind. This openness allows inhabitants to adapt and shape their living environments based on their needs

James Wines’ drawings for the Highrise of Homes departs from conventional facades. Instead of emphasizing exterior features, Wines focuses on the structural framework, transforming it into an open landscape for construction. This approach establishes a unique connection with natural elements at every level, blurring the boundaries between the built environment and nature.

15

An interresting contrast between rural and urban elements within the same structure is worth exploring.

40

Urban Camping

41 Urban Camping

42 Urban Camping

43 Urban Camping

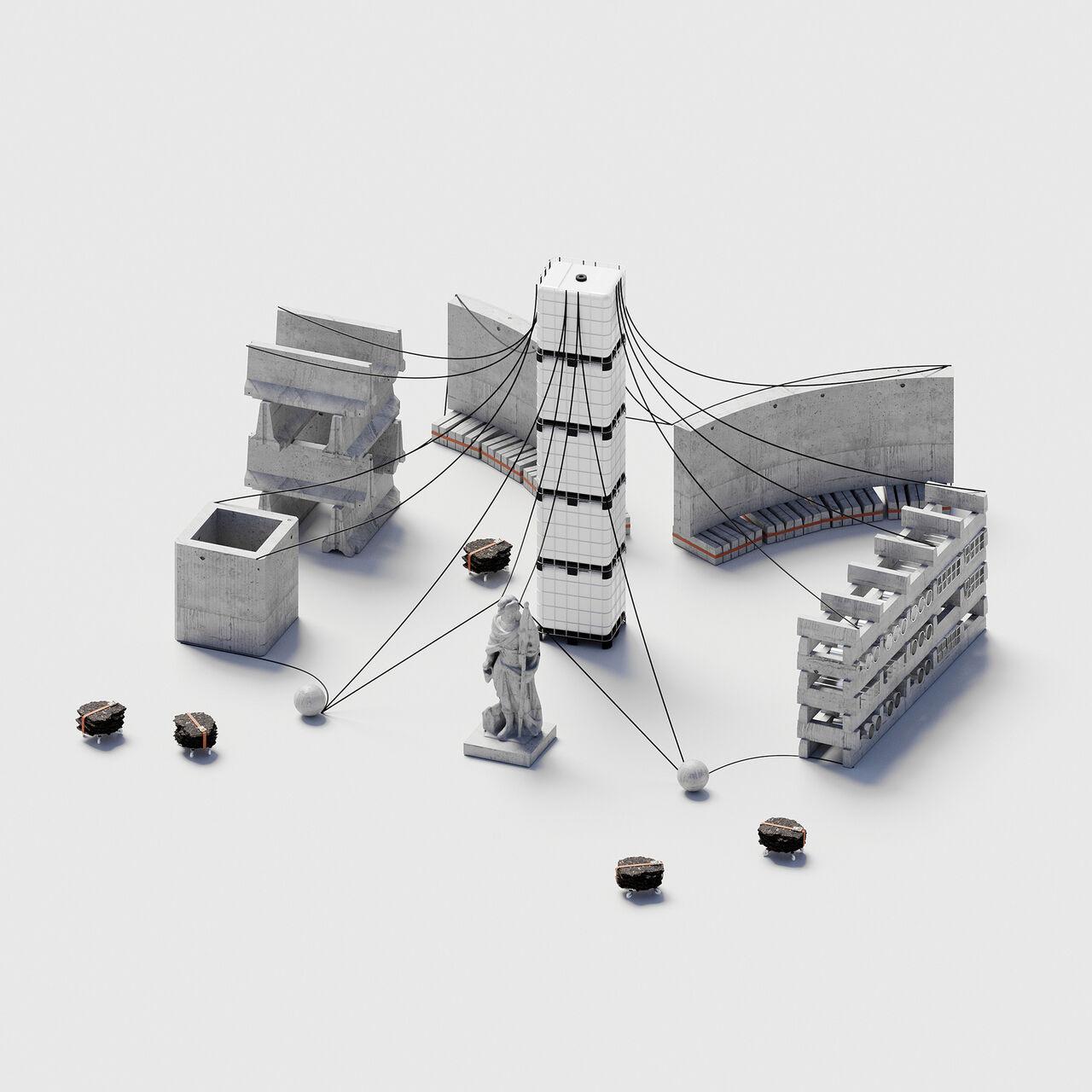

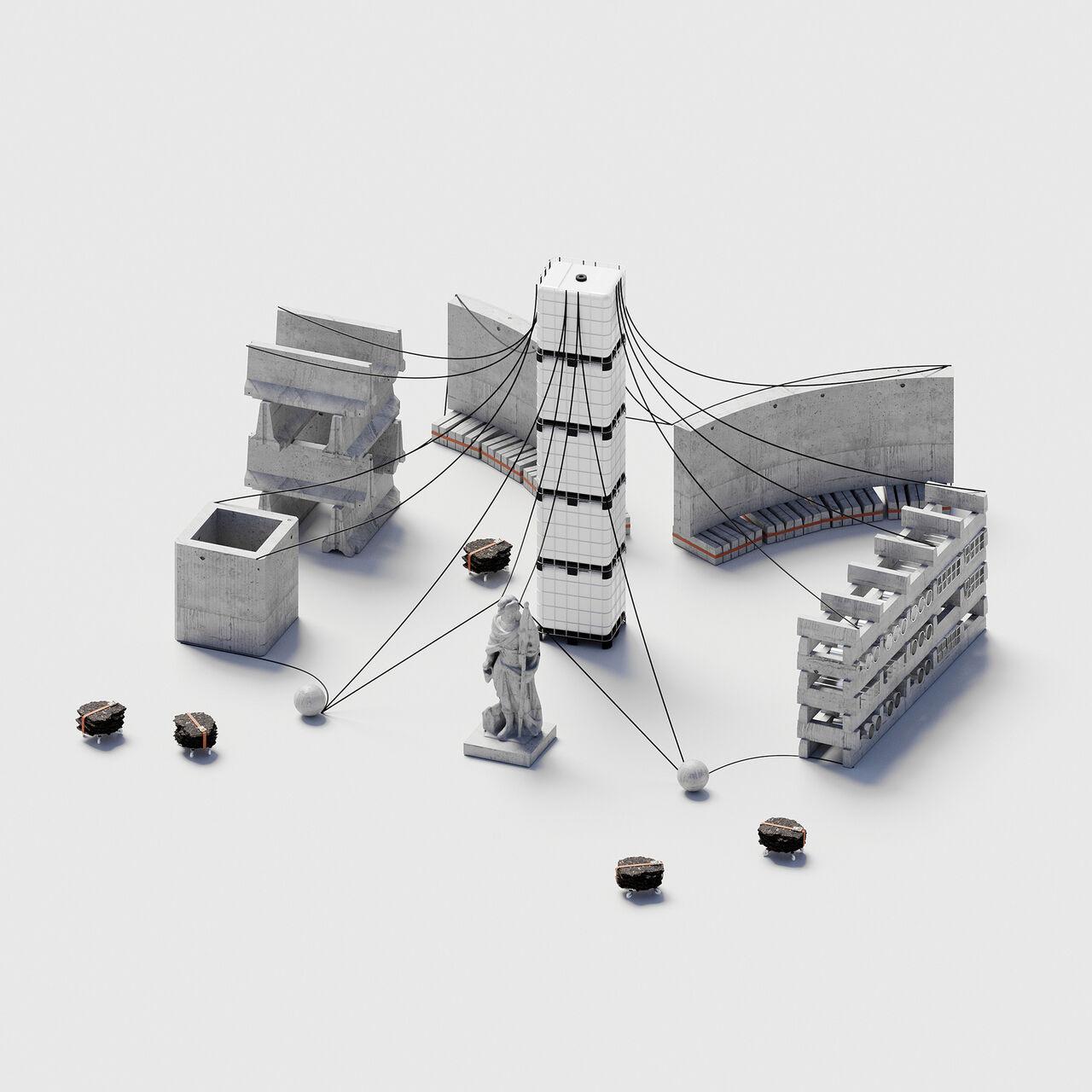

Case Study c: Arcad, Theo de Meyer, 2021

44 Found

Objects

Fig 8: “Arcade,” Theo De Meyer, (2021)

Case Study d: Permanently Temporary Pavilion, Kosmos Architects, 2023

45

Found

Objects

Fig 9: “Permanently Temporary Pavilion” Kosmos Architects, (2023)

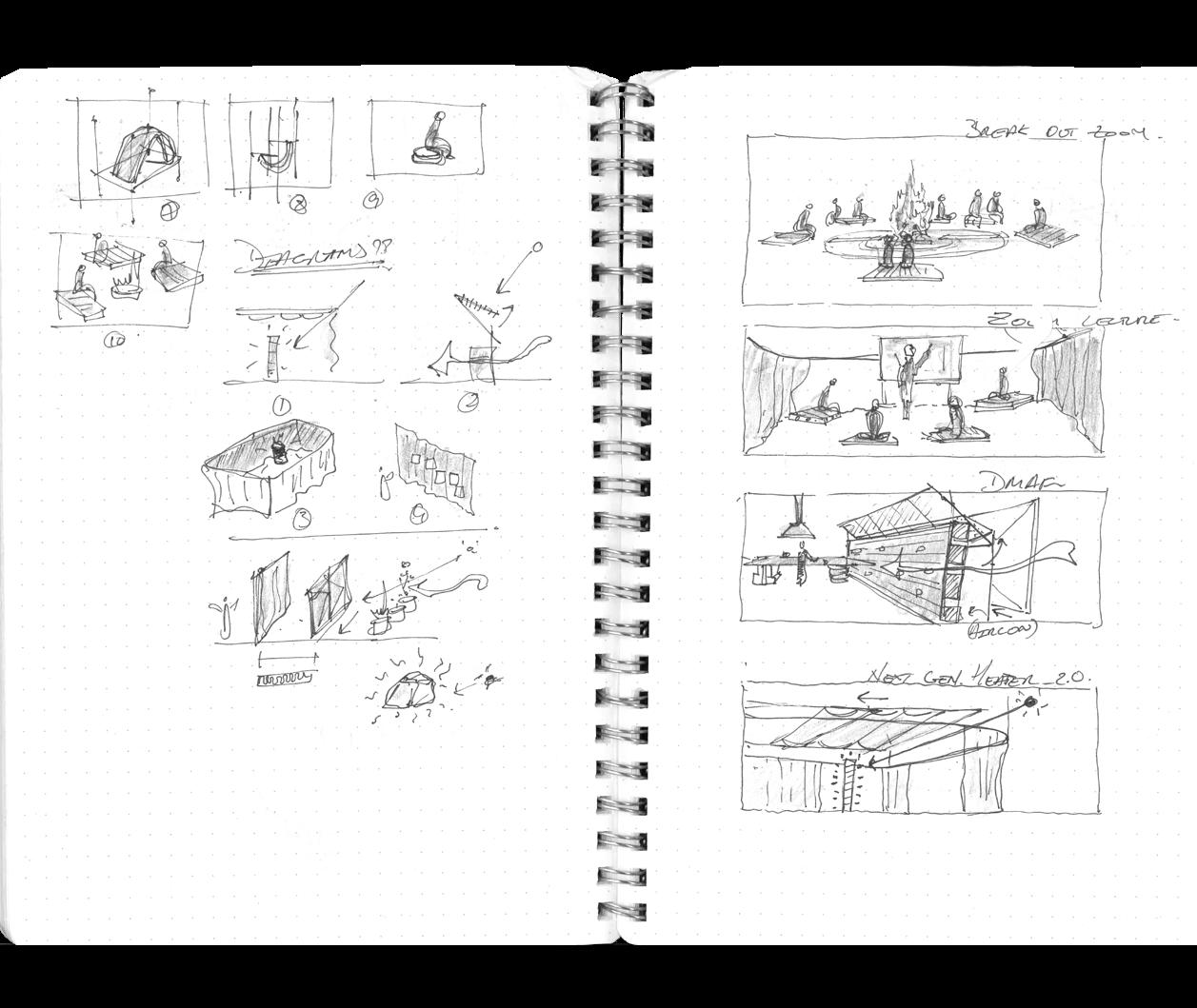

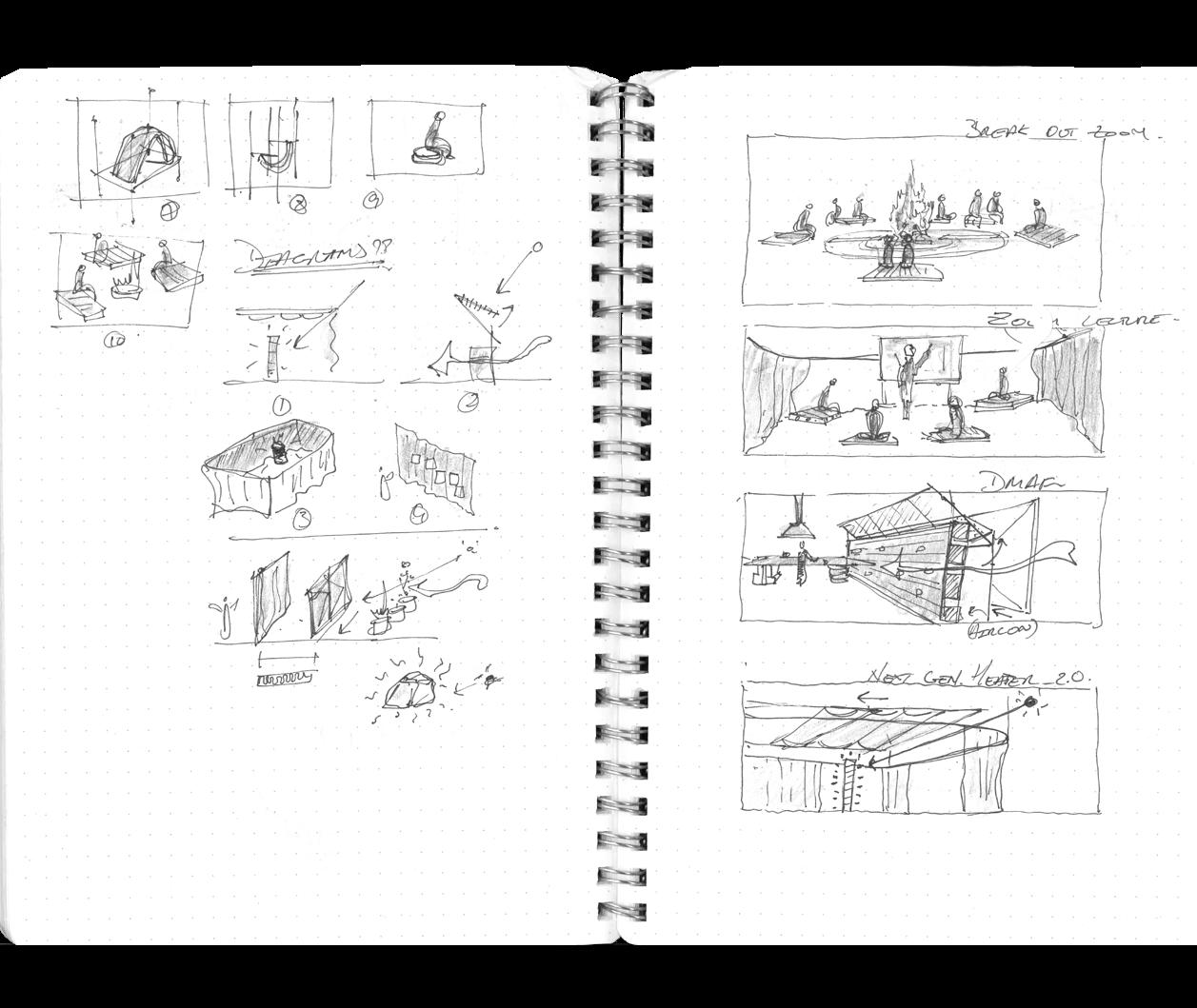

Found Objects

46

47 Drafting Unit Found Objects

48

Zoom Lecture

Found Objects

49

Found Objects

Enclosed Heat Room

Sleeping Pods

Found Objects

50

51

2.0

Found Objects Heater

Found Objects

52

Zoom

break out room

53

Dmaf

Found Objects

In the context of this thesis, exploring the aftermath of an economic crisis prompts a closer examination of found objects and the reuse of materials by squatters. With transportation systems halted, the quest for shelter necessitates a focus on locally available materials.

The scenario unfolds in a landscape devoid of shared cultural building techniques. The objective is straightforward: identify materials readily accessible in the surroundings and employ them in the assembly of easily constructed furniture, addressing the practical challenges posed by the crisis.

Materials sourced locally, the on-site assembly of architecture, and adherence to the local climate characterize the creation of spaces in a world where the predominant religion was techno-centric, leaving it empty of diverse cultures.

Can this approach still be termed vernacular?

54

55

56

Long Section

57

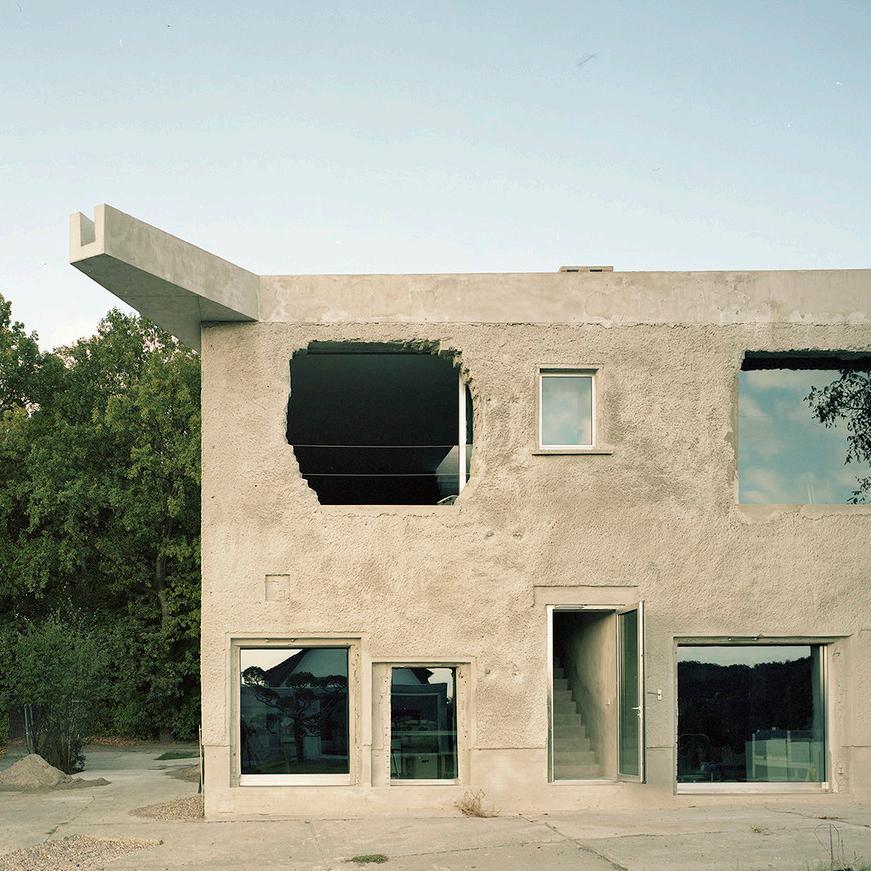

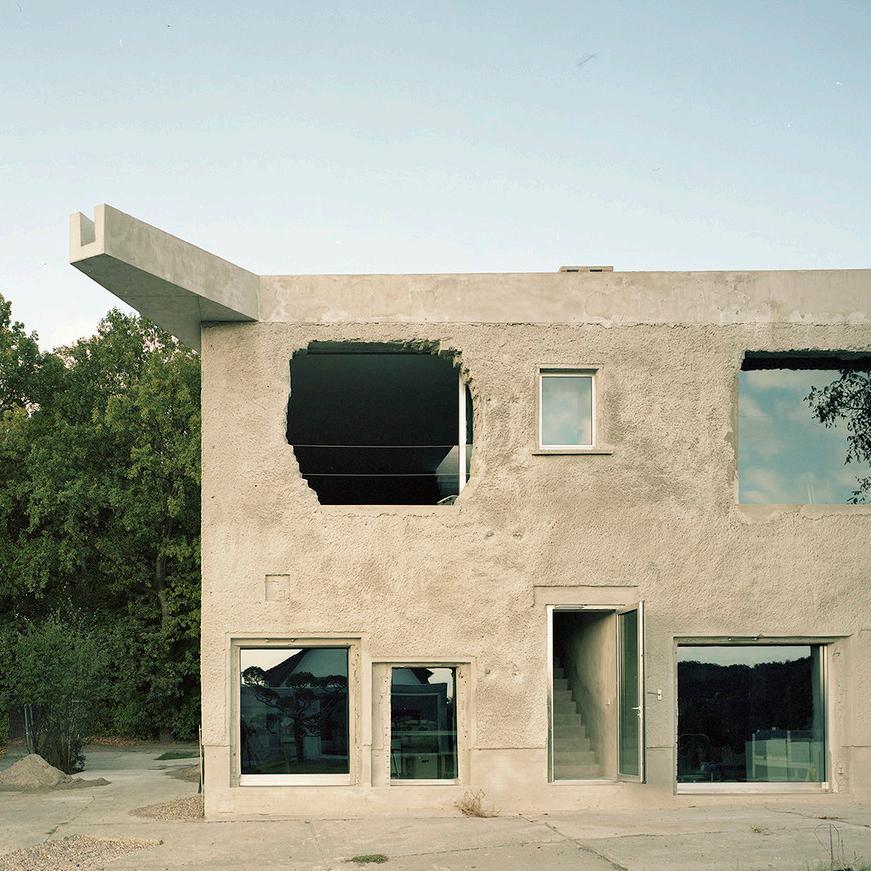

Case Study e: AntiVilla, Bplus, 2015

58 Substraction

Fig 10: ““Antivilla”, Bplus, 0131 Antivilla - bplus (2015)

59 Substraction

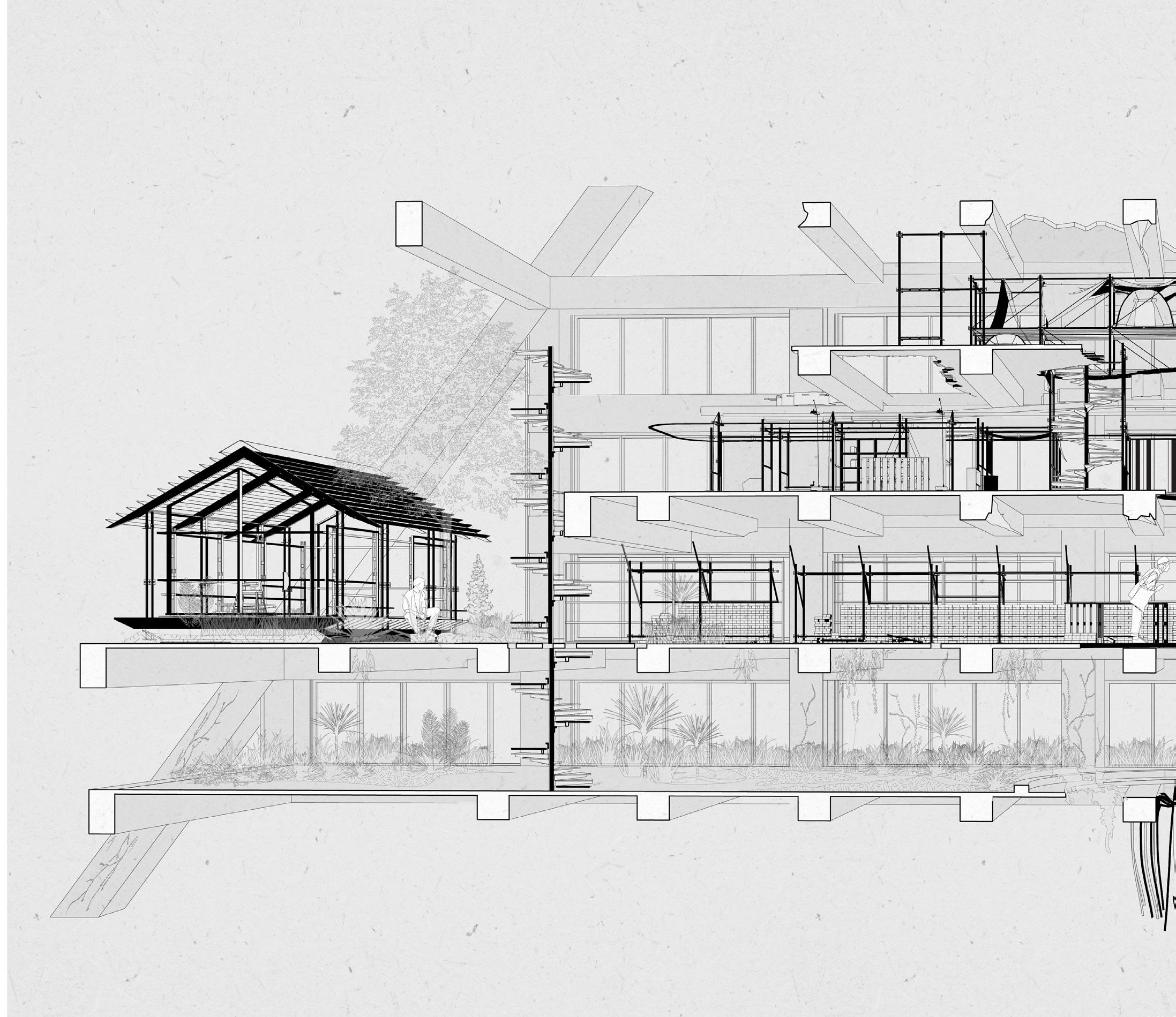

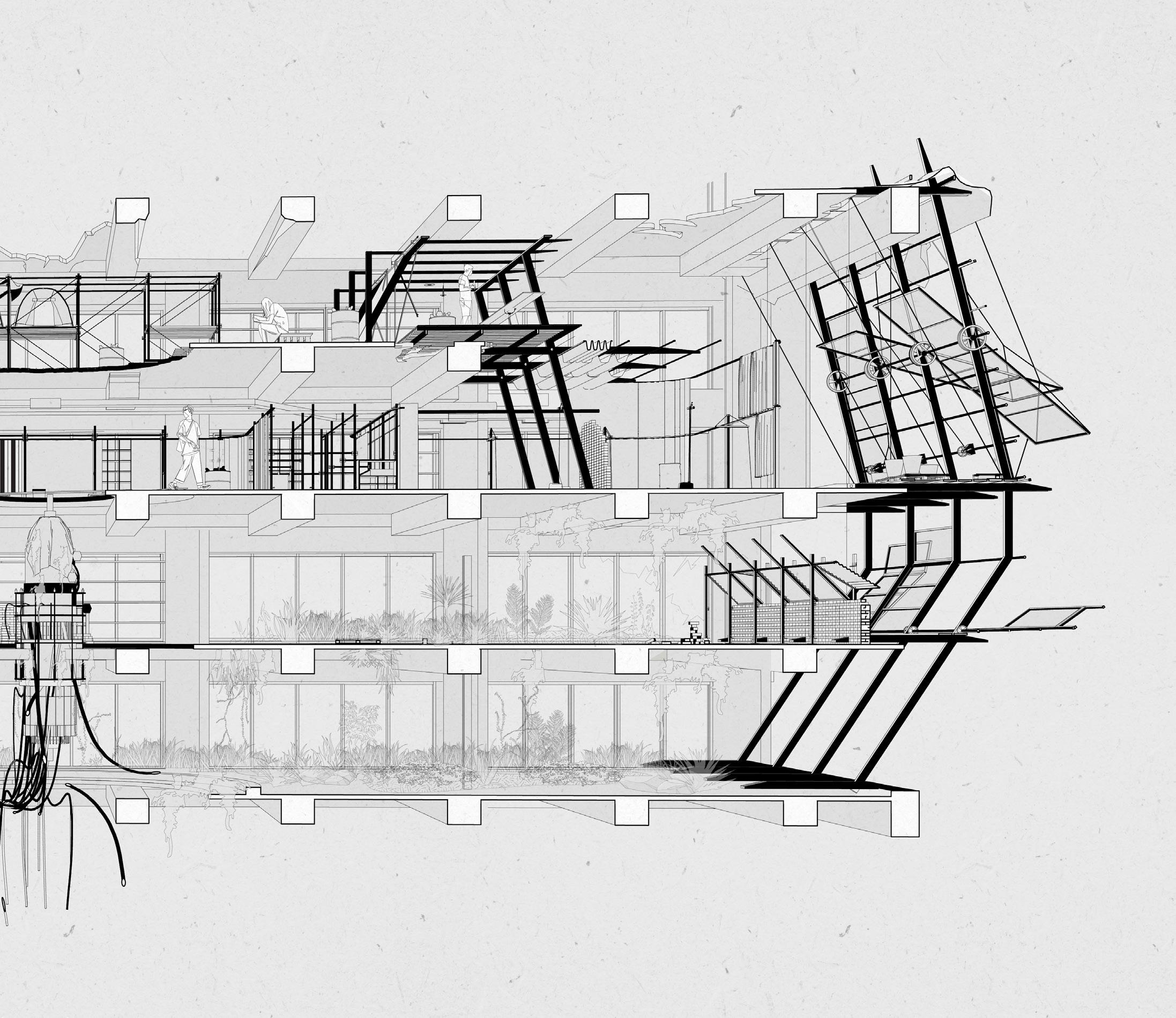

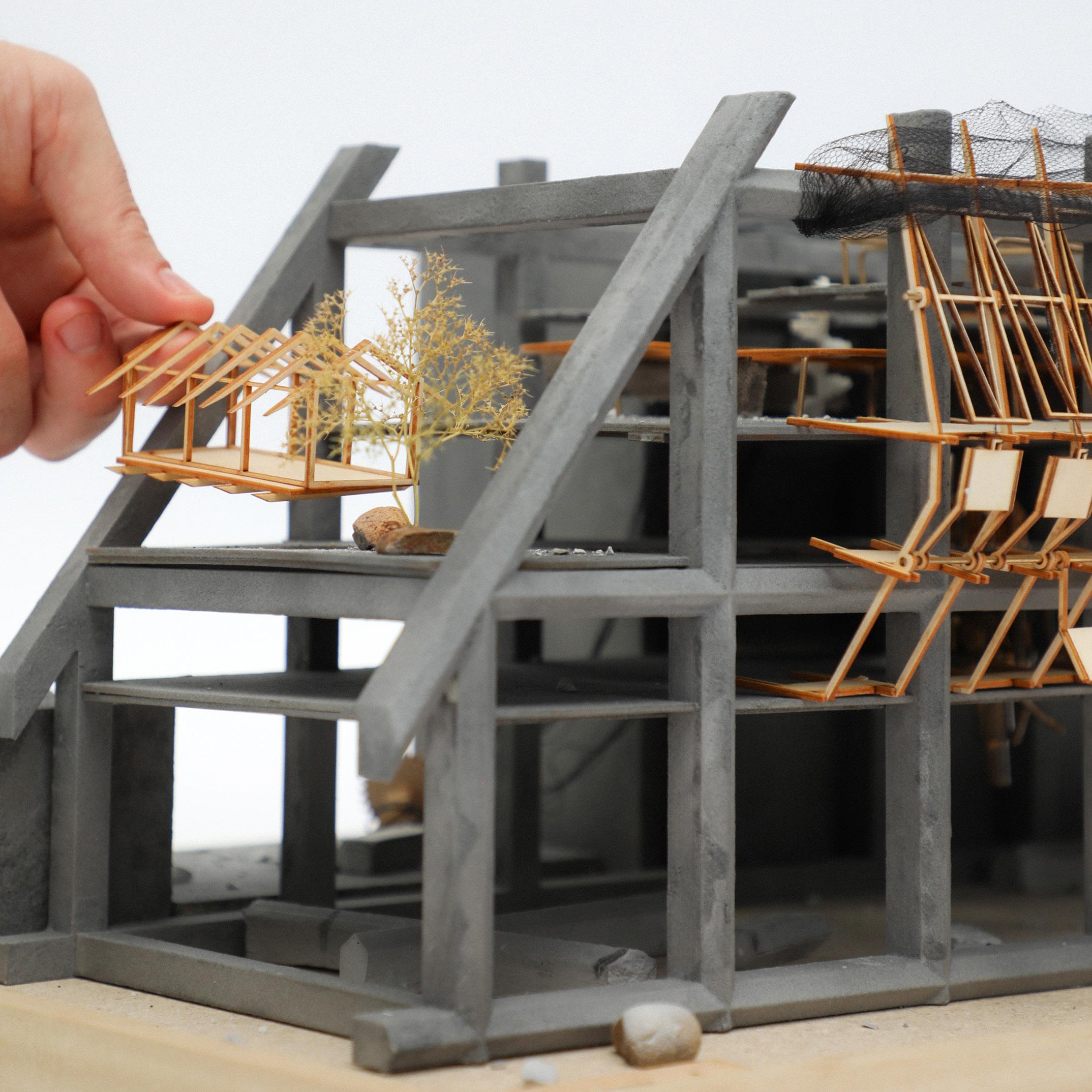

An architecture evolving on-site through user interventions in an anarchic manner. To optimize space for squatters, strategic demolitions of slabs were conducted. Understanding the beam locations enabled the squatters to penetrate various levels. This process aimed to enhance natural light, facilitate stack ventilation, and create room for the construction of new structures.

60

61

62 Level 30 0 5 10 N

63 Level 29 0 5 10 N

64

14.

2. 3. 1 5 4 6 7 8 9 3 3 15 9 14 13 12 10 11 Level 30 Level 29 Level 28 Floorplans

1. Sleeping pods

2.

Kitchen

3.

Toilets 4. Drafting Spaces 5. Social Space

6.

Library 7. Lecture room 8. Seminar space 9. Semi-external verandah

10.

Moveable thermal curtains

11.

Plants as a climatic barrier

12.

Outdoor workshop

13.

Indoor workshop

Climatic barrier

65

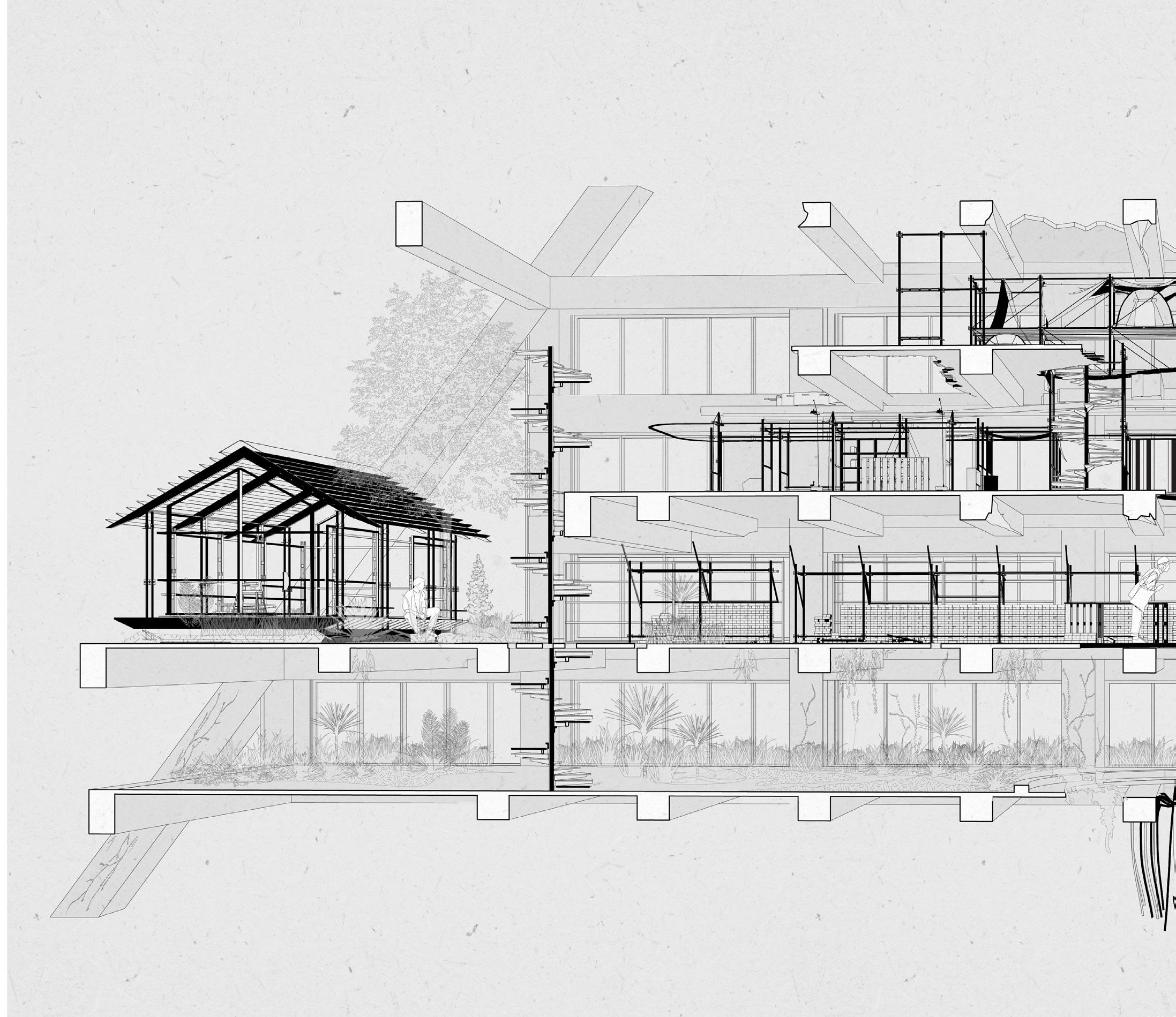

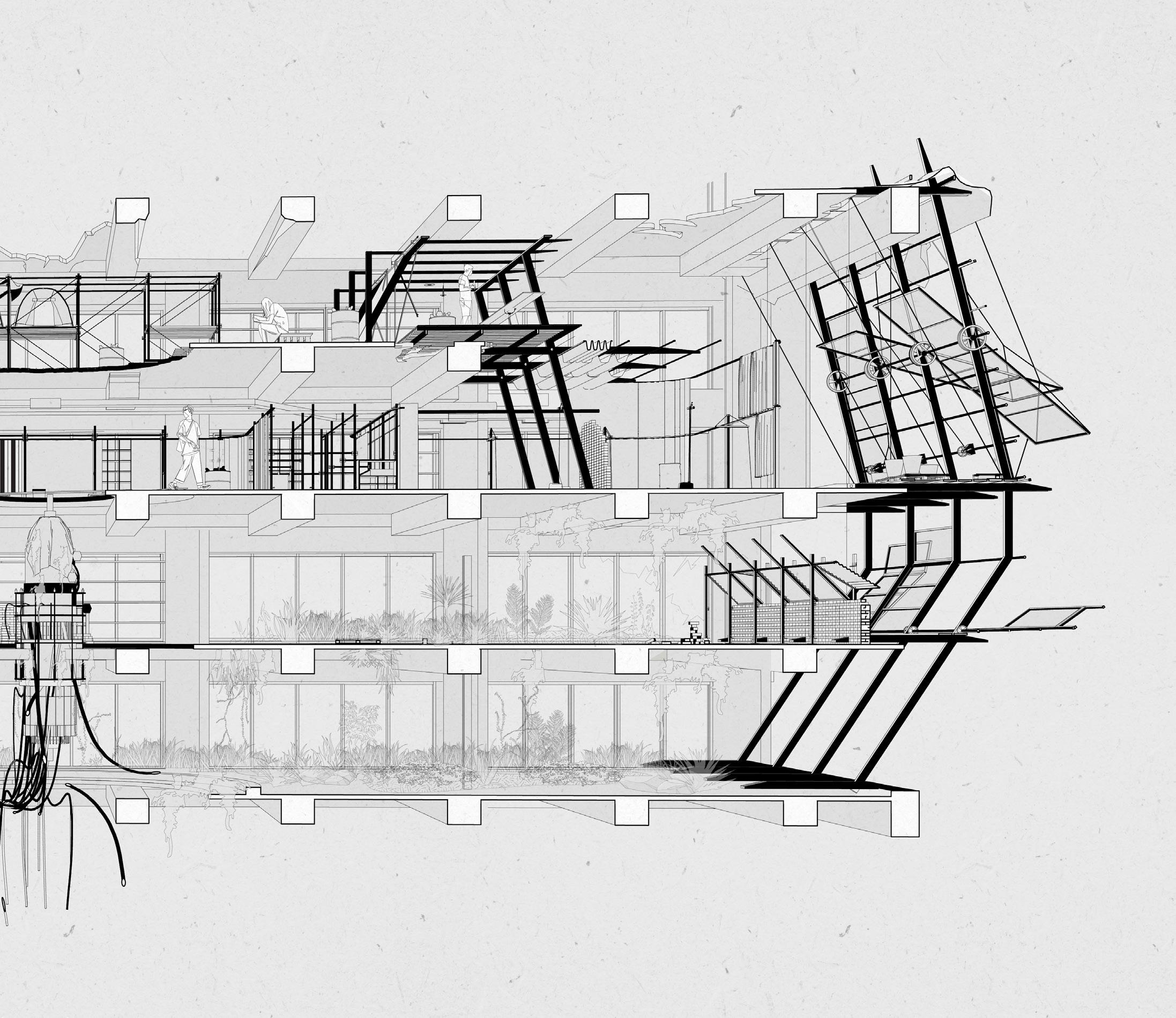

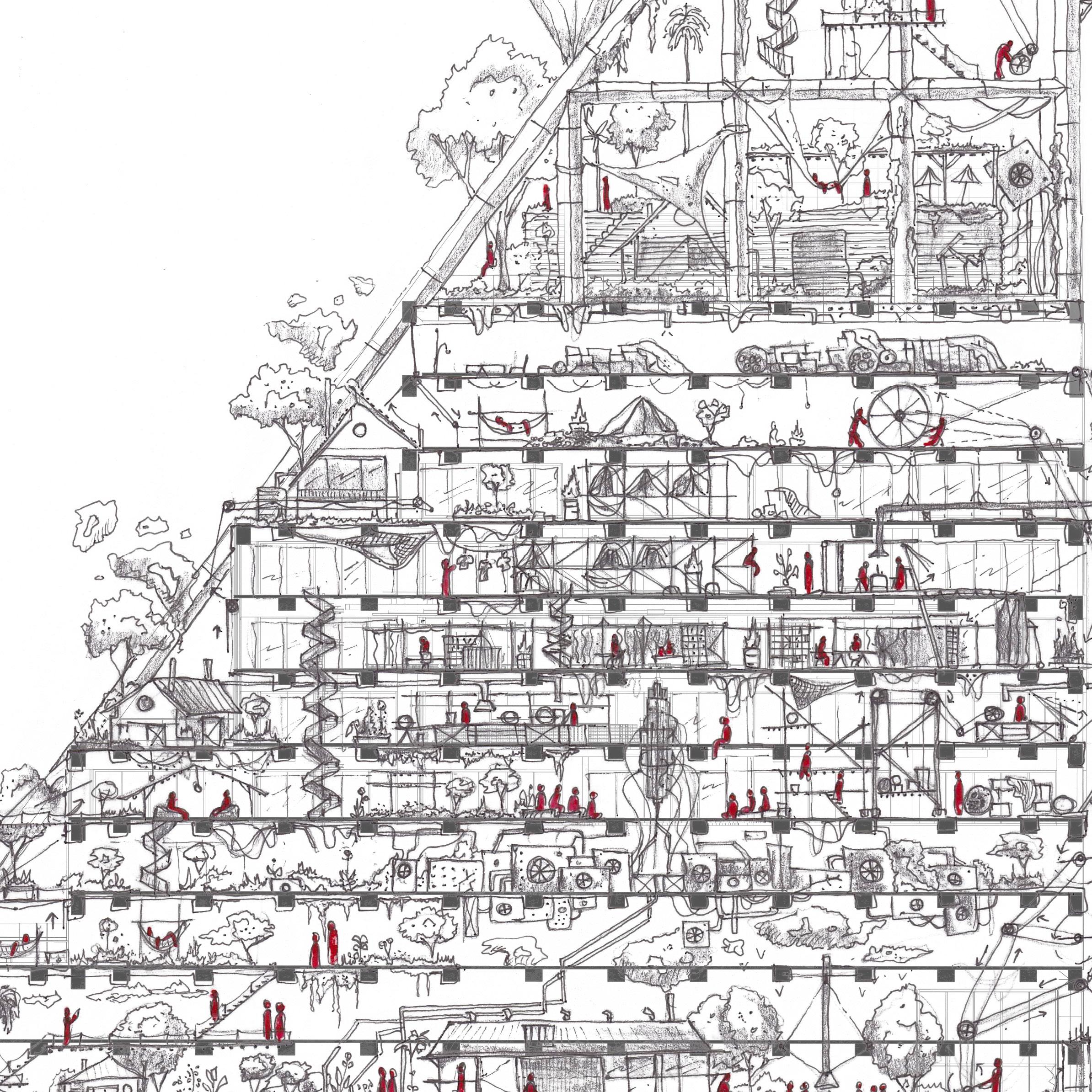

The squatters initiated the building's "repair" by working in the reverse order of its construction, starting from the top and spreading downwards. Floor 30 was transformed into a living and sleeping area, with tent constructions and simple kitchen. Progressing to level 29, the main creative hub was established for collaborative design, discussions about the future of architecture, and communal activities. Thermal curtains separated spaces for privacy, housing drafting areas, a seminar room, a library, a theater, and a social space—all designed in their most basic form, adaptable for change.

Floor 28, currently in deconstruction, embraces the encroachment of plants, offering an opportunity to integrate nature. Double heights open floors, inviting sculptural explorations, this floor is set to evolves into a workshop for construction.

Each floor maintains its core purpose from its previous use.

The floors aim to communicate, creating small interconnected spaces within the expansive building, akin to tree houses in a forest, fostering a sense of connection and shared experiences.

66

67

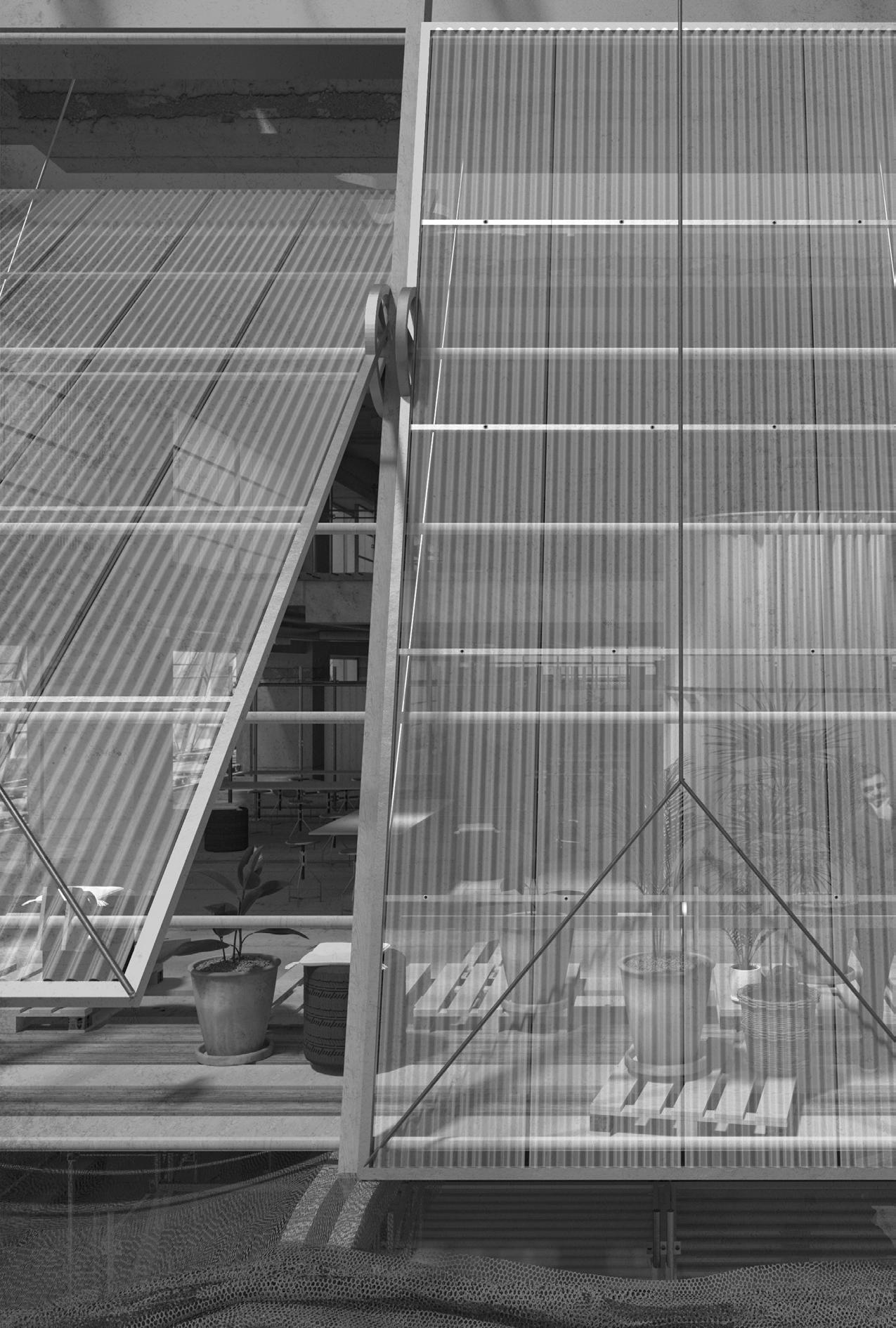

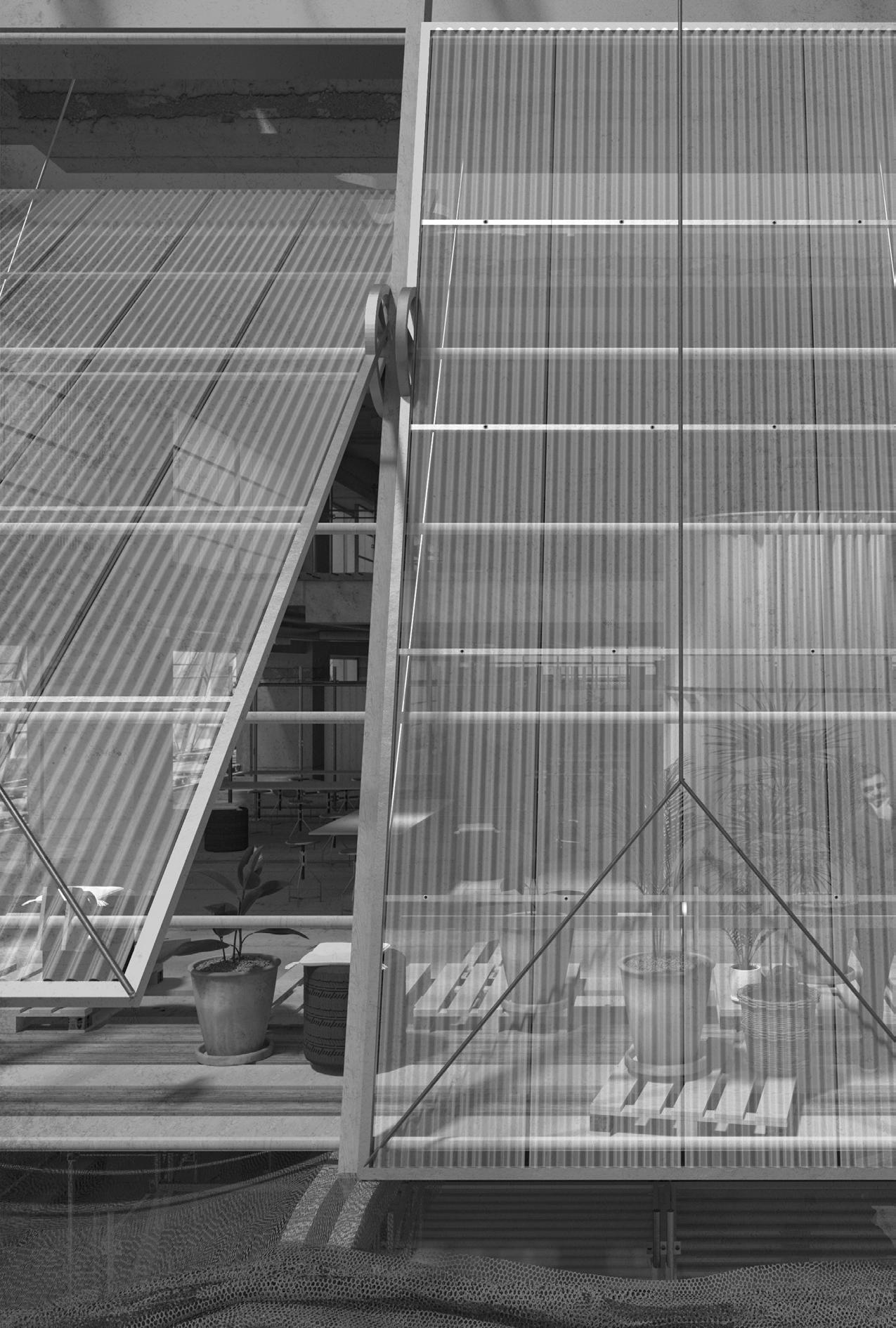

Case Study f: 500 logements, Lacaton and Vassal, 2017

Lacaton and Vassal’s approach to renovating the building envelope proves highly relevant.

The incorporation of extended winter gardens and balconies offers each apartment enhanced natural light, increased versatility of use, and expanded views.

Lacaton and Vassal employ multiple insulation barriers, including polycarbonate, glazing, and thermal curtains, with air in between as a crucial element. This strategy not only creates different thermal zones but also ensures adaptability and flexibility.16

68 Passive Design Before After

Fig 11: “500 logements”, Lacaton et Vassal, 2017

The transparent and translucent layers of the winter garden sequence are choreographed to connect with and complement the existing building. Serving as visual and thermal barriers, these adaptable layers promote flexible inhabitation. The winter garden can be fully open, closed, or at various degrees of openness, catering to user needs in any climate.

69

Passive Design

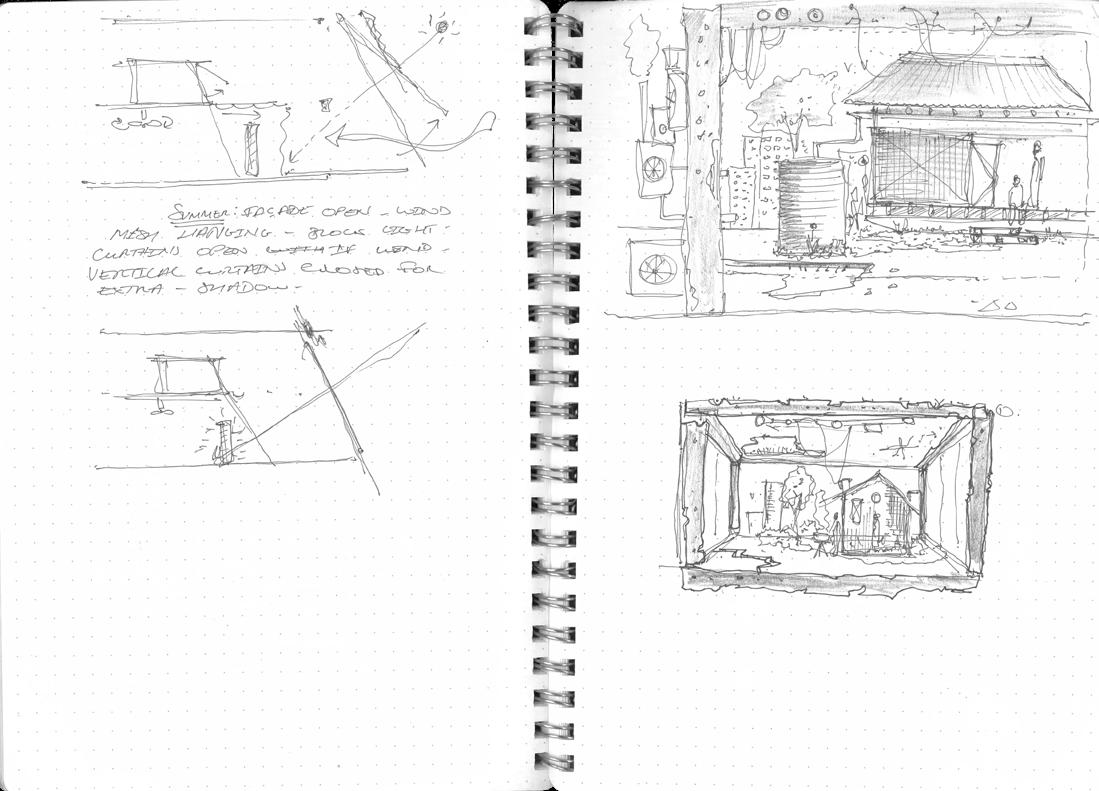

Author’s own, 2023

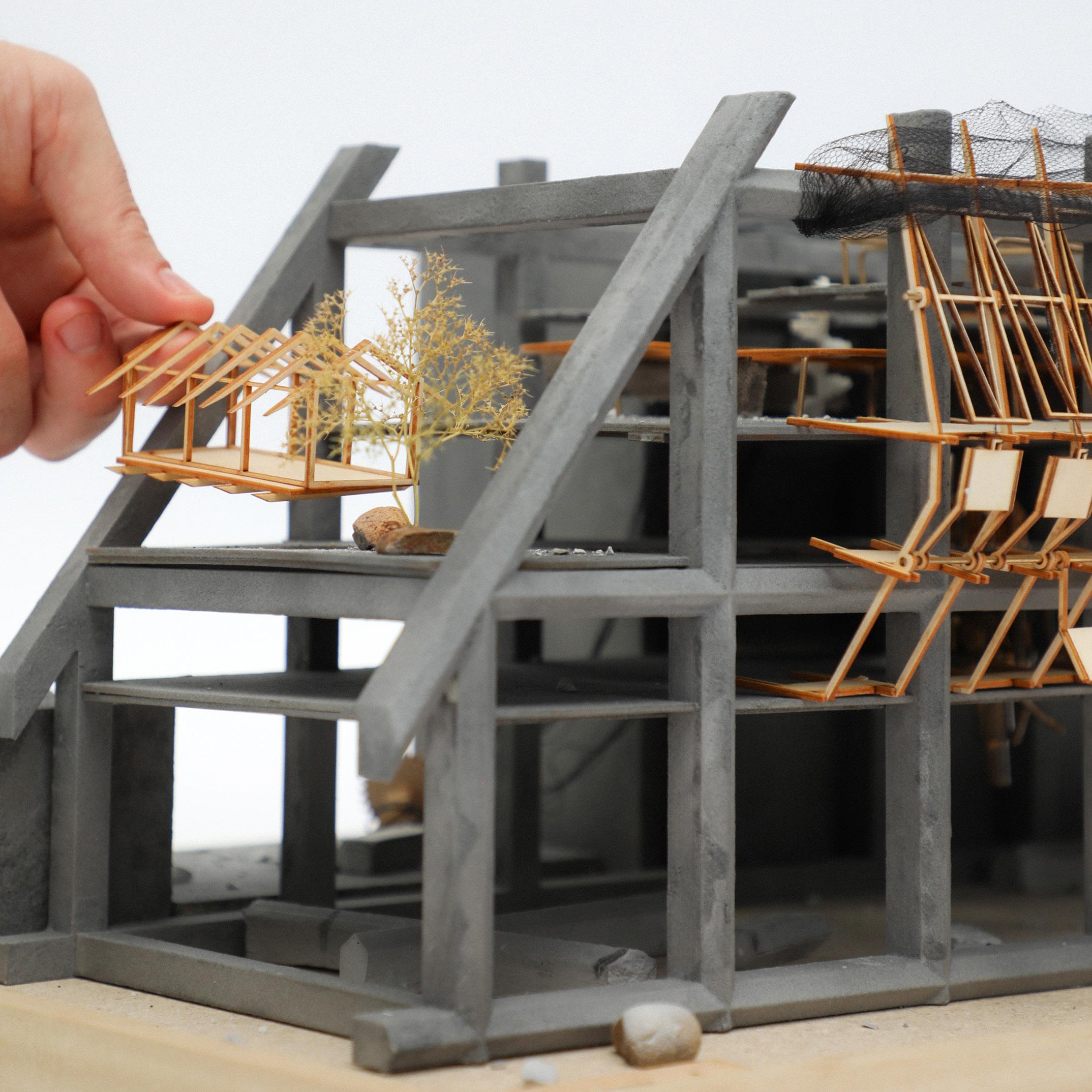

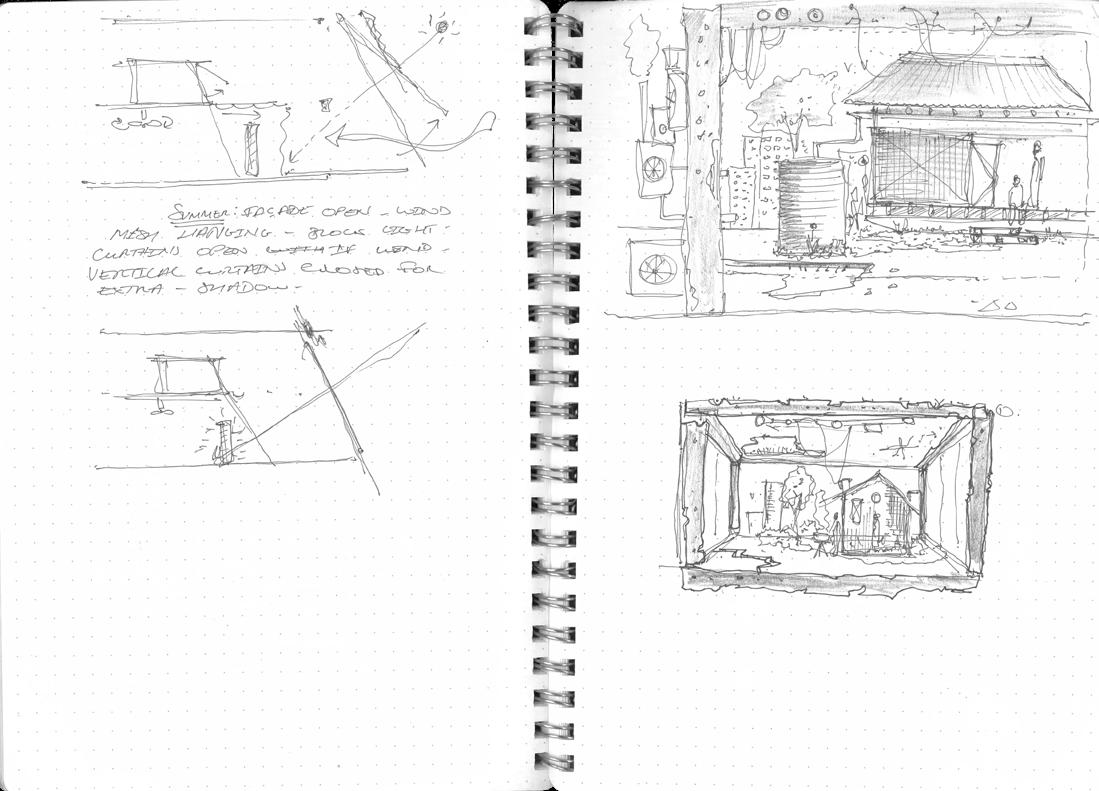

In the process of reworking the facade, the primary objective was to maximize openness to the outside and utilize internal walls for shelter and comfort. However, there is a need for physical protection against strong winds. Drawing inspiration from tropical house verandahs and the winter gardens features of Lacaton and Vassal, the proposed design involved constructing a shell around the building on-site.

This shell, equipped with closable gates and polycarbonate panels, serves as both a protective structure and a source of natural light. The innovative addition creates a new balcony and thermal zone, effectively separating the interior from the exterior.

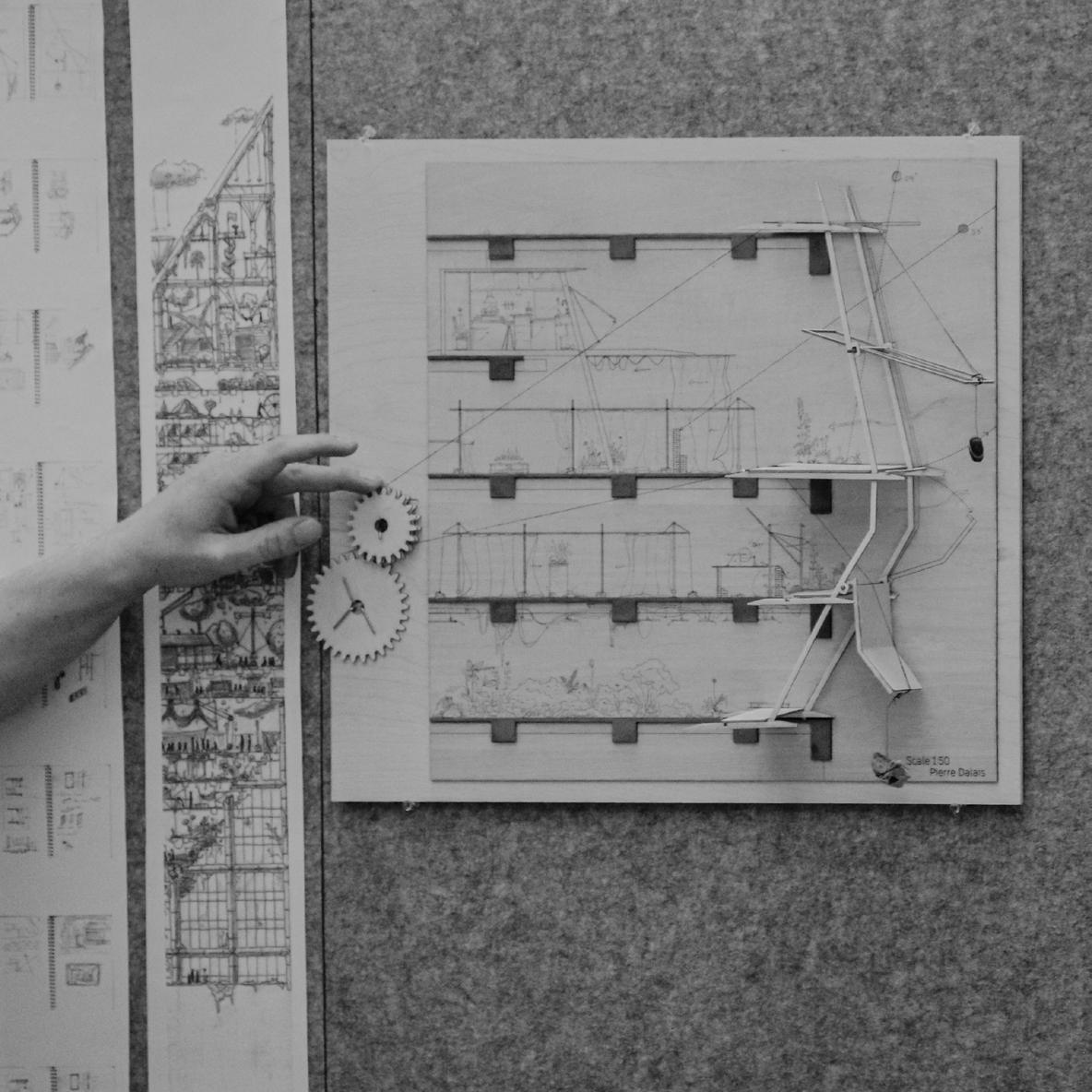

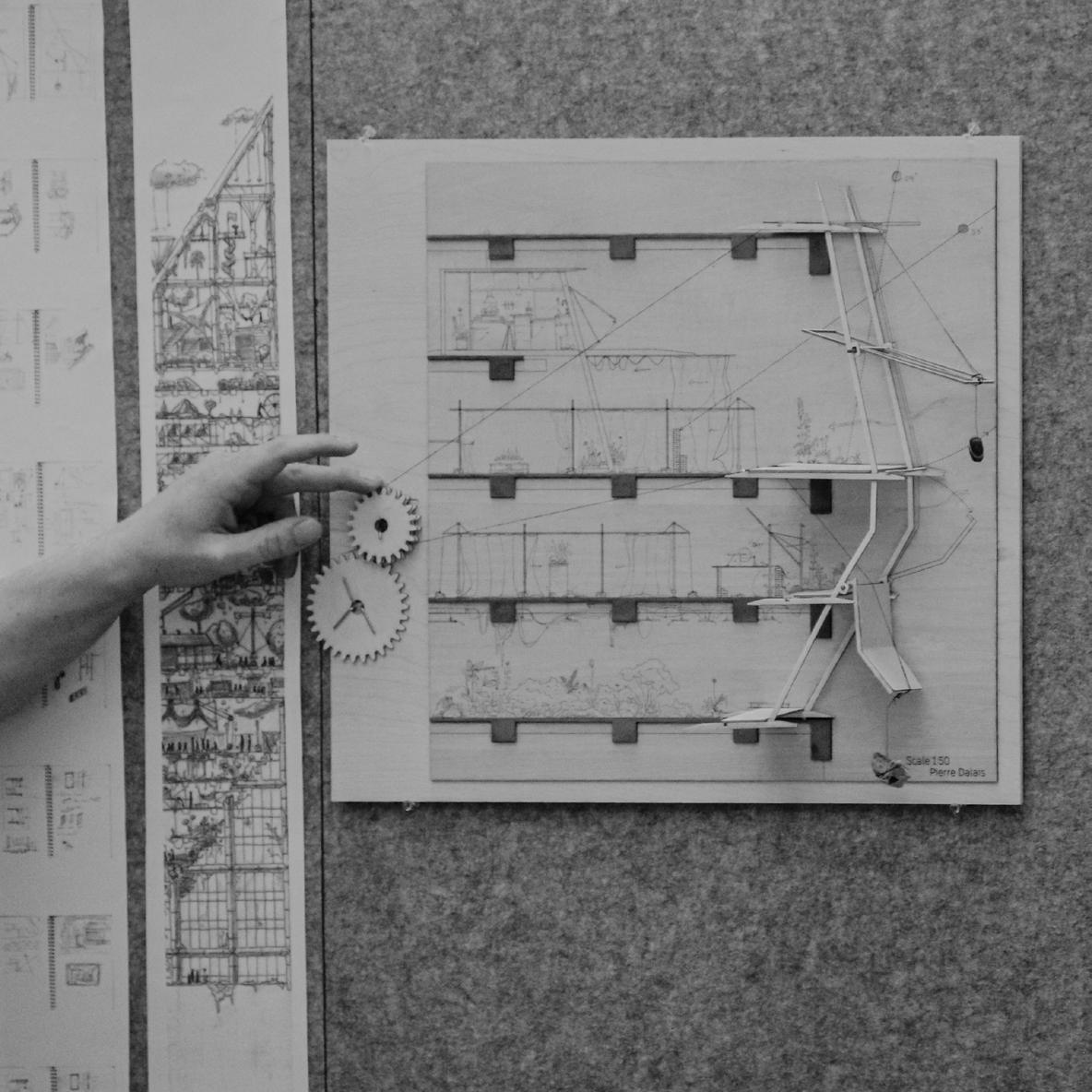

The mechanical system employed harks back to medieval machinery, predating electricity, playing with the intriguing concept of time and technology. A system of cables, gears, and counterweights is utilized to move and close the gates. For added versatility, another layer is introduced to provide shade when necessary, a construction net suspended from the upper level.

70

71

During summer months, the gates are kept open to facilitate ventilation, and the mesh net is deployed. All internal curtains are opened to maximize air circulation throughout the space. In contrast, during winter, the gates are closed, and the mesh net is lifted, allowing only sunlight to penetrate and warm the thermal walls and concrete slabs. Internal curtains are closed to retain heat, and individual heating sources, such as fires, are activated within each zone to ensure comfort in the colder months.

72

73

Summer Winter

74

An interractive façade

75

Climatic Approach

76

77

78

79

80

Hand Drawn v.4 : Urban Camping

81

82

Hand Drawn v.1 : Architectural Anarchy

83

To conclude, this exploration delved into the complex past, present and future relationship between technology and architecture. The three epochs envisioned—Modernism's homogenization, the embrace of high-tech solutions, and the resurgence of low-tech resilience—serve as a medium to criticise the techno-centric and globalised world which has left us lacking of diverse cultural expressions.

The project highlights the potential for repair, reuse, and adaptation without the sole reliance on technological enhancements. The objective isn't to strive for an ideal, hermetically sealed internal comfort but to forge spaces that coexist with the natural environment. An architecture emerging in direct response to climate and context has the power to organically foster a regional aesthetic and a sense of identity

84

Conclusion

85

1. Philippe Rahm, *Histoire naturelle de l’architecture* (Paris: Pavillon de l’Arsenal, 2020).

2. Kenneth Frampton, *Modern Architecture: A Critical History* (Thames and Hudson, 1992).

3. Bernard Rudofsky, *Architecture Without Architects* (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1964).

4. Australian Institute of Architects, “Melbourne’s own internationally renowned architect, Sean Godsell, to deliver headline address at NGV,” *Phys.org*, 2023, https://members.architecture.com.au/ EventDetail?EventKey=VIC220909.

5. Le Corbusier, *Towards a New Architecture* (Dover Publications, 2007).

6. Smithsonian National Museum of American History, “Patent Model for a Water Heater,” 1877, https:// americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1440161.

7. Steven Johnson, *How We Got to Now: Six Innovations That Made the Modern World* (Riverhead Books, 2014).

8. Raymond Arsenault, *The End of the Long Hot Summer: The Air Conditioner and Southern Culture* (The University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

9. Murray Fraser, « A global history of architecture for an age of globalization », *ABE Journal*, https://doi. org/10.4000/abe.5702.

10. “AI Investor Warns of ‘God-Like’ Machines That Could Destroy Humanity,” *Futurism*, November 8, 2023, https://futurism.com/ai-investor-warns-god-like-machines-destroy-humanity.

11. Deborah Yao, “The Accelerated Pace of AI Advancements Made Demis Hassabis Believe AGI Will Arrive Much Sooner Than Expected,” *Emerj*, November 8, 2023, .

12. Jacques Ellul, *Le bluff technologique* (Hachette, 2012).

88

Endnotes

13. “Foster + Partners, *Deutsche Bank Place*,” https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/deutsche-bankplace, 2023.

14. “Life in the Tower of David, Caracas – in pictures,” *The Guardian*, The Tower of David in Caracas, Venezuelain pictures | Art and design | The Guardian.

15. Museum of Modern Art, ‘Highrise of Homes, James Wines,’ Accessed November 2, 2023, https://www.moma. org/collection/works/709.

16. Transformation de 530 logements, 2017, *Lacaton & Vassal* (lacatonvassal.com).

89

Figures

1. Clemens Gritl, “Artificial 3D Computer Models,” Galerie Juliane Hundertmark, accessed November 9, 2023, [https://www.galeriehundertmark.com/clemens-gritl](https://www.galeriehundertmark.com/ clemens-gritl).

2. Liam Young, “Tomorrow’s Thoughts Today: Liam Young’s Animation Depicts a Dystopian Future City,” Dezeen, accessed November 1, 2023, [https://www.dezeen.com/2015/03/18/liam-young-tomorrowsthoughts-today-architecture-future-city-dystopia-cities-dystopian-animation/](https://www.dezeen. com/2015/03/18/liam-young-tomorrows-thoughts-today-architecture-future-city-dystopia-citiesdystopian-animation/).

3. Foster + Partners. “Deutsche Bank Place,” n.d., accessed November 1, 2023, [https://www. fosterandpartners.com/projects/deutsche-bank-place](https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/ deutsche-bank-place).

4. “Offices for Lease at Deutsche Bank Place, 126 Phillip Street, Sydney, NSW 2000,” realcommercial. com.au.

5. Foster + Partners. “Deutsche Bank Place,” n.d., accessed November 1, 2023, [https://www. fosterandpartners.com/projects/deutsche-bank-place](https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/ deutsche-bank-place).

6. Iwan Baan, “Torre David, Informal Vertical Communities,” 2013, [Torre David - Informal Vertical Communities | Iwan Baan](http://www.iwan.com/).

7. Museum of Modern Art, “Highrise of Homes, James Wines,” accessed November 2, 2023, [https:// www.moma.org/collection/works/709](https://www.moma.org/collection/works/709).

8. Theo De Meyer, “Arcade,” 2023, [https://theodemeyer.be/arcade/](https://theodemeyer.be/arcade/).

9. Kosmos Architects, “Permanently Temporary Pavilion,” accessed November 1, 2023, [https://k-s-m-s. com/projects/85kPCP9bp](https://k-s-m-s.com/projects/85kPCP9bp).

90

9. Bplus, “Antivilla,” 2015, [0131 Antivilla - bplus](https://www.bplus.com/).

10. Lacaton & Vassal, “Transformation de 530 logement,” 2017, [lacatonvassal.com](https://www. lacatonvassal.com/).

All links are marked as accessed on November 1, 2023. Please let me know if you need further adjustments.

91

References

Arcade, Theo De Meyer, 2023, https://theodemeyer.be/arcade/

“Antivilla”, Bplus, 2015 0131 Antivilla - bplus

Audra. “This Abandoned Office Tower in Caracas Is the World’s Largest Vertical Slum.” Demilked, April 15, 2014. https:// www.demilked.com/tower-of-david-abandoned-skyscraper-caracas-iwan-baan/.

“Foster + Partners. (n.d). Deutsche Bank Place. Retrieved from https://www.fosterandpartners.com/projects/deutschebank-place

Gannon, Todd. Reyner Banham and the paradoxes of high tech. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2017. Giamarelos, Stelios. Resisting postmodern architecture: Critical regionalism before globalization. London: UCL Press, 2022.

Gritl, Clemens. “Artificial 3D Computer Models.” Galerie Juliane Hundertmark. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www. galeriehundertmark.com/clemens-gritl.

Heathcote, Edwin. “How ‘high Tech’ Became the Architectural Style of Globalisation.” Financial Times, March 23, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/92d5063a-277d-11e8-9274-2b13fccdc744.

Herzog, Directed by Werner. “Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World: Film Review: Spirituality & Practice.”

Lo and Behold, Reveries of the Connected World | Film Review. Accessed November 5, 2023. https://www. spiritualityandpractice.com/films/reviews/view/28270/lo-and-behold-reveries-of-the-connected-world.

Iwan Baan. 2013. Torre David, Informal Vertical Communities. Retrieved from Torre David - Informal Vertical Communities | Iwan Baan

“Learning from the Past.” Troppo Architects. Accessed November 10, 2023. https://www.troppo.com.au/learning-fromthe-past.

“Permanently Temporary Pavilion” Kosmos Architects https://k-s-m-s.com/projects/85kPCP9bp

“Museum of Modern Art. ‘Highrise of Homes, James Wines.’ Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.moma.org/ collection/works/709

“Offices for Lease at Deutsche Bank Place, 126 Phillip Street, Sydney, NSW 2000,” realcommercial.com.au,

92

Borrett, Matthew. “Hypnagogic City.” MATHEW BORRETT. Accessed November 10, 2023. https://www. mathewborrett.com/hypnagogic-city/nbf5zh7f3jwq2fv0wzoqjs7d290hts.

Dorval-Bory, Nicolas, and Guillaume Ramillien. “BAP ! 2022 - Exposition Visible Invisible.” BAP Visible Invisible, May 17, 2022. https://bap-visibleinvisible.com/en/.

Terrain, Luis. “‘ruins of Modernity: The Failure of Revolutionary Architecture in the 20th Century.’” “Ruins of Modernity: The Failure of Revolutionary Architecture in the 20th Century” | The Strength of Architecture | From 1998, January 2, 2013. https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/ruins-modernity-failure-revolutionary-architecture-20thcentury.

Umbach, Maiken, and Bernd Hüppauf. Vernacular modernism: Heimat, globalization, and the built environment.

Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2005.

Miller, Caitlin. “The Future of Living by Urtzi Grau & Guillermo Fernández-Abascal, UTS School of Architecture.”

Yellowtrace, April 28, 2022. https://www.yellowtrace.com.au/the-future-of-living-research-project-urtzi-grauguillermo-fernandez-abascal-uts-school-of-architecture/.

93

Pierre Dalais