ALMANAC

Almanac is a literary magazine from Playwrights Horizons. Established in 2020, at a time of pandemic and protest, Almanac is a new kind of publication — one in which a theater and the artists who comprise it come together to take stock of contemporary politics, culture, and playwriting. Through plays, essays, interviews, poems, and visual art, Almanac charts the coordinates of the present day, as measured by thinkers and makers whose work lives both on and beyond the stage.

EDITORIAL BOARD

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Natasha Sinha

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

Adam Greenfield

EDITOR

Libby Carr

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Lizzie Stern

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING Teresa Bayer

EDITOR Fiona Selmi

CREATIVE DIRECTOR Jordan Best

DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Alison Koch

EDITOR May Treuhaft-Ali

ALMANAC PL AYWRIGHTS HORIZONS 416 W 42ND ST, NEW YORK, NY 10036

Copyright © 2023 Playwrights Horizons, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed by Michael Harrison of WestprintNY. Almanac has received generous support from The Liman Foundation.

Shayok

Contributors

DAVID ADJMI’s plays have been produced at theaters around the world. He holds commissions from Playwrights Horizons, Yale Rep, Berkeley Rep, and the Royal Court (UK). His critically acclaimed memoir Lot Six was published by HarperCollins in 2020, and his collected plays are published by TCG. Upcoming at Playwrights Horizons: Stereophonic.

CÉSAR ALVAREZ (they/them) is a composer, lyricist, playwright, and performance maker. They create big experimental gatherings disguised as musicals in the key of inter-dimensionality, socio-political transformation, kinship and coexistence. César was a Princeton Arts Fellow, a recipient of The Jonathan Larson Award, The Guggenheim Fellowship and the Kleban Prize. César teaches at Dartmouth College. www.cesaralvarez.net

VIVIAN J.O BARNES is a writer from Virginia. Her short plays have been produced at Ensemble Studio Theatre, Steppenwolf Theatre, and Actors Theatre of Louisville. Her play The Sensational Sea Mink-ettes will have its world premiere at Woolly Mammoth Theatre in 2024. She’s a proud member of the Writers Guild of America.

SIVAN BATTAT (she/they) is a theatre director & community organizer, and the Director of New Work Development at Noor Theatre. Sivan seeks to bridge justice work and cultural work, bringing the power of performance to our movements, and the vision of movement work to our theaters. sivanbattat.com

TERESA BAYER is the Director of Marketing at Playwrights Horizons. When she is not selling and celebrating the incredible mission and programming at Playwrights, she is chasing her toddler around Astoria, Queens with her husband and Husky-Akita, arranging flowers as head designer for Raving Flamingo Flowers, and teaching yoga.

JORDAN BEST is the Graphic Design Manager and artwork designer for Playwrights Horizons.

AGNES BORINSKY is a writer, performer, and convener of people. Her most recent play, The Trees, premiered in 2023 at Playwrights Horizons, in a co-production with Page 73. She lives in Los Angeles.

ISAAC BUTLER is the author of The Method: How the 20th Century Learned to Act and the co-author, with Dan Kois, of The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels in America. He also co-hosts Working, a podcast about the creative process, for Slate.

LIBBY CARR is the Marketing Assistant at Playwrights Horizons. As a playwright, their work as been developed at Playwrights Horizons’ New Works Lab, the Kennedy Center, the Workshop Theater, the University of Texas at Austin, MOtiVE Brooklyn, and Austin’s Ground Floor Theater.

JOHN J. CASWELL, JR. is a playwright originally from Phoenix and the author of Wet Brain (Playwrights Horizons, MCC), Scene Partners (Vineyard Theatre), Man Cave (Page 73), and God Hates This Show (HERE). Education: Juilliard School, Hunter College, Arizona State University.

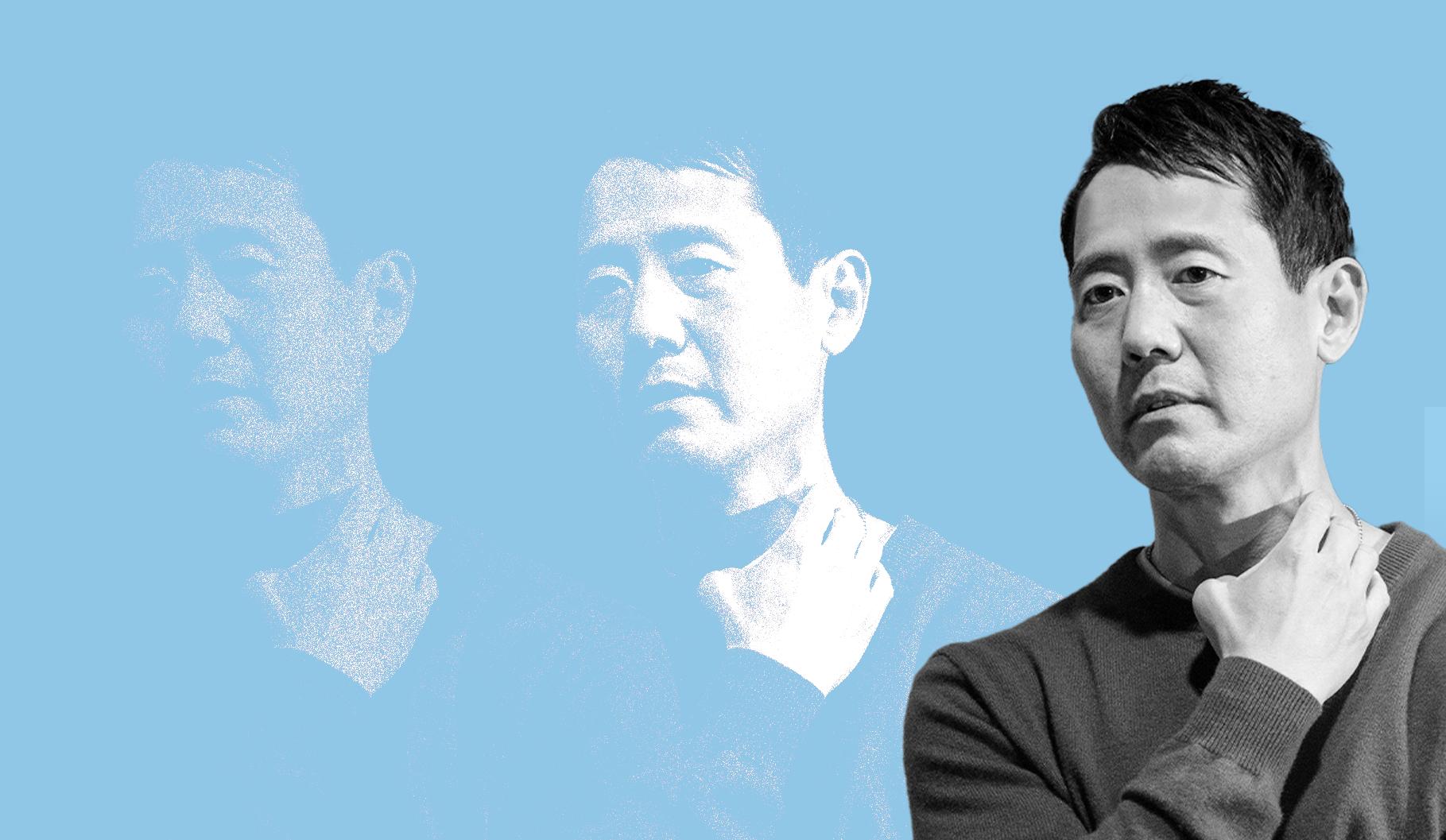

SHAYOK MISHA CHOWDHURY is a Relentless Award, Mark O’Donnell Prize, Jonathan Larson Grant, and Princess Grace Award-winning writer and director. He recently directed the Soho Rep and NAATCO production of his play Public Obscenities “with a swooning hypnotism reminiscent of the best works of neorealism” (New York Times, Critic’s Pick).

MIA CHUNG received a 2023 Whiting Award for Drama and a 2022 MAP grant for a music-theatre work. Her play Catch As Catch Can premiered at Playwrights Horizons in Fall 2022 (World Premiere, Page 73, 2018). Additional: Ball In The Air, This Exquisite Corpse, You For Me For You.

DEBORAH S. CRAIG (actor, singer, writer) is best known for creating the role of Marcy Park in The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. Based on her own overachieving childhood, she received a Drama Desk Award and the distinction of creating the first Korean American character on Broadway. She can currently be streamed in these movies: “Meet Cute” on Peacock and “Me Time” on Netflix and in lots of TV shows. Miss Craig was the first writer/actor to be accepted into the Ma-Yi Writers Lab. She is a transracial, transnational adoptee from South Korea and a self-taught Asian. IG: @thedeborahscraig

EISA DAVIS likes to write, make music, and act, in any order, or all at once. She’s from the Bay Area and lives in Brooklyn. Some works: Bulrusher, Angela’s Mixtape, Mushroom, Ramp, The History of Light, The Essentialisn’t, Afrofemononomy, songs for Devil In A Blue Dress, justice, joy.

LARISSA FASTHORSE (Sicangu Lakota) is an award winning writer and 2020-2025 MacArthur Fellow. Her satirical comedy, The Thanksgiving Play, made her the first known female Native American playwright on Broadway under the direction of Rachel Chavkin. She has many new productions coming up including the national tour of Peter Pan.

ADAM GREENFIELD is Artistic Director of Playwrights Horizons. He has a husband called Jordan and a dog called Trapper, and they all live in Brooklyn.

DAVE HARRIS is a poet, playwright, and screenwriter from West Philly. When he isn’t writing or pretending to write, he is cooking for the people he loves and dancing closely with strangers.

Contributors

DOMINIQUE FAWN HILL is a Tony Award-nominated and Obie Award-winning costume designer for Broadway and Film. Broadway: Fat Ham (Tony Award nomination); Off-Broadway: Tambo & Bones (Playwrights Horizons –Lucille Lortel nomination); Fat Ham (Obie Award); Where the Mountain Meets the Sea (Manhattan Theatre Club); The Dark Girl Chronicles (The Shed); 125th & FREEdom (National Black Theatre). Dominique earned her M.F.A., University of California San Diego and you can find her work at www. dominiquefhill.com

SAMUEL D. HUNTER’s plays include The Whale, A Bright New Boise, Pocatello, The Few, The Harvest, Lewiston/Clarkston, Greater Clements, and A Case for the Existence of God, among others. Originally from northern Idaho, he lives in NYC with his husband, daughter, and terrier mutt.

DAVID HENRY HWANG’s works include M. Butterfly, Yellow Face, Soft Power, Aida, Chinglish, and Flower Drum Song (revival), as well as thirteen opera libretti. He has been honored with Tony, Grammy, and three Obie Awards, and is a three-time Finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Drama.

JULIA IZUMI’s (she/her) works include Regretfully, So the Birds Are (Playwrights Horizons/WP Theater), miku, and the gods. (ArtsWest), and others. Her work has been developed at MTC, Clubbed Thumb, New Georges, Berkeley Rep, and more. Honors for her work include the OPC Dr. Kerry English Artist Award, O’Neill Finalist, and KCACTF’s Darrell Ayers Playwriting Award. Current New Dramatists Resident, LMCC Workspace Resident, and Civilians R&D Group Member. Current commissions: True Love Productions, MTC/Sloan, Playwrights Horizons, Seattle Rep 20x30. MFA: Brown University.

ABIGAIL JEAN-BAPTISTE (any/all pronouns) is a theater maker, director, and writer born & based in New York with familial roots in Haiti and the American South. Guided by questions around blackness, femininity and kinship, her work uses fragmented language, repeatable gestures, and tactile objects in search of unconventional and nonsensical ways of being.

EMILY JOHNSON is an artist who makes body-based work. She is of the Yup’ik Nation, is a land and water protector and an organizer for justice, sovereignty and well-being. Emily has lived on the Lower East Side of Mannahatta in Lenapehoking for the last seven years.

JENNY KOONS. The Whitney Album (Soho Rep), Regretfully, So the Birds Are (Playwrights Horizons), Head Over Heels (Pasadena Playhouse w/Sam Pinkleton), Hurricane Diane (Huntington), Men on Boats (Baltimore Center Stage), Speechless (Blue Man Group North American Tour), A Midsummer Night’s Dream (The Public Theater Mobile Unit), Burn All Night (American Repertory Theatre), A Sucker Emcee (National Black Theatre, LAByrinth), The Odyssey Project.

HARUNA LEE is an Obie Award-winning Taiwanese/ Japanese/American theater maker, screenwriter, educator and community steward whose work is rooted in a liberation-based healing practice. For Playwrights Horizons’ Soundstage, they performed in His Chest Is Only Skeleton by Julia Izumi. They are a co-director of the Brooklyn College MFA Playwriting Program. harunalee.com

L MORGAN LEE (she/her) is a Tony Award® nominated actress and storyteller with over twenty years in the business. Her work has included Broadway, Off-Broadway, International/National concerts, tours, and studio recordings. L Morgan is dedicated to championing stories centering women’s voices on both stage and screen. For more: lmorganlee.com

RJ MACCANI is a parent and the Director of Training for Common Justice, the first alternative-to-incarceration and victim-service program in the United States that focuses on violent felonies in the adult courts. RJ is an LMSW and his vocational experience reflects three complementary passions: transformative justice, somatic coaching, and the creative arts.

MONA MANSOUR is thrilled to be part of this year’s Almanac. Her play The Vagrant Trilogy made its NYC debut last year at the Public Theater. She is currently working on a musical about Zelda Fitzgerald with singer-composer Hannah Corneau and director Michael Greif, as well as a joint-stock play exploring quantum entanglement with her theater company SOCIETY. Proud member of WGA, SAG and the Dramatists Guild.

QUI NGUYEN is a Los Angeles-based playwright, filmmaker, and co-founder of Vampire Cowboys Theatre Company. Notable works include Vietgone, She Kills Monsters, and the Disney films Raya and the Last Dragon and Strange World. He’s a proud of member of the WGA.

BRUCE NORRIS is the author of Clybourne Park, which received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama (2011) as well as the Olivier, Evening Standard, and Tony Awards. Other plays include Downstate, The Low Road, The Qualms, Domesticated, A Parallelogram, The Unmentionables, The Pain and the Itch, and Purple Heart

DEIRDRE O’CONNELL has appeared at Playwrights Horizons in Corsicana, Circle Mirror Transformation, Manic Flight Reaction, Spatter Pattern, and Moe’s Lucky Seven. She won a Tony for Best Performance for her appearance in Dana H. in 2022. She has an Obie for Sustained Excellence and a New York Drama Critics Circle Special Citation. She has had four shows of her paintings at Susan Eley Fine Art Galleries. You can find the work at susaneleyfineart.com.

Contributors

SARAH SCHULMAN is a novelist, playwright and AIDS historian and is the author of the plays Carson McCullers (dir Marion McClinton, Playwrights Horizons/The Women’s Project), Manic Flight Reaction (w/ Deirdre O’Connell, dir Trip Cullman, Playwrights Horizons), Enemies, A Love Story (adapted from IB Singer, w/ Morgan Spector, The Wilma Theater), The Burning Deck (w/ Diane Venora, La Jolla Playhouse) and The Lady Hamlet (w/ Jennifer Van Dyck, dir David Drake, Provincetown Theater – BroadwayWorld Boston’s Best New Play). She is a Guggenheim fellow in Playwrighting. Her musical SHIMMER, with composer Anthony Davis and lyricist Michael Korie, will be presented at Yale University’s Innovation Summit on June 1.

FIONA SELMI is a Brooklyn-based dramaturg and writer. She was the Artistic Fellow at Playwrights Horizons for the 2022/23 season, and currently works at United Talent Agency as the assistant to a theatrical literary agent. She holds a BA from Williams College in Theater and Political Science.

JEN SILVERMAN’s plays include Spain, Collective Rage, The Moors, The Roommate, and Highway Patrol. Books include the novel We Play Ourselves, story collection The Island Dwellers, and forthcoming novel There’s Going to be Trouble (Random House, 2024). Jen also writes for TV and film. Honors include fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim.

NATASHA SINHA (she/her) is Associate Artistic Director of Playwrights Horizons, and co-founder of Beehive Dramaturgy Studio and Amplifying Activists Together.

JENANI SRIJEYANTHAN (they/she/them) is an anti-violence advocate residing in Brooklyn, NY. Their abolitionist and transformative work to end gender violence is housed within Just Beginnings Collaborative and the devi co-op. jenani’s work centers young survivors and survivors who experience incarceration and/or system-involvement, namely from queer communities.

VERA STARBARD, T’set Kwei, is a Tlingit and Dena’ina playwright, magazine editor, and Emmy-nominated TV writer. She was Playwright-in-Residence at Perseverance Theatre through the Andrew W. Mellon National Playwright Residency Program, and longtime newspaper and magazine editor for various publications, including First Alaskans Magazine. She is a writer for the PBS Kids children’s program “Molly of Denali,” which won a Peabody Award in 2020 and was nominated for two Children and Family Emmys in 2022. She recently was staffed on the ABC show “Alaska Daily.”

LIZZIE STERN is the Literary Director at Playwrights Horizons. She is also a freelance writer and editor.

MARIA STRIAR is a founder of and the Producing Artistic Director of Clubbed Thumb, which commissions, develops and produces funny, strange and provocative new plays by living American writers. Writers who made their professional debut with them include Will Arbery, Jaclyn Backhaus, Clare Barron, Gina Gionfriddo, Angela Hanks, and many more.

AMITA SWADHIN (they/them) is the Founding Co-Director of Mirror Memoirs, a national organization uplifting the narratives, healing, and leadership of Black, Indigenous and of color LGBTQI+ child sexual abuse survivors. Amita’s life experiences as a queer, nonbinary South Asian, US-born survivor has guided their work as an organizer, storyteller and educator for over two decades.

LAYLA TREUHAFT-ALI has taught middle-school English and History in Chicago Public Schools since 2019. Last year, she and her students won a $1.5 million city grant to build a student-designed playground in West Englewood. She helped craft the Literacy and Justice for All Act (currently headed to the Illinois governor’s desk!).

MAY TREUHAFT-ALI is the Literary and Community Engagement Assistant at Playwrights Horizons. Her past Almanac contributions include “The Center of the World: Playwrights Horizons and 42nd Street” in Issue 1. As a playwright, her work has been developed at Ars Nova, Rattlestick, Clubbed Thumb, The Playwrights Realm, The Movement Theatre Company, and MCC Theater.

JENNY ZHANG is the author of the story collection Sour Heart and the poetry collection My Baby First Birthday. She also writes for TV and film.

Letter from the Editors

Natasha Sinha and Lizzie Stern

DEAR READER,

Welcome to Playwrights Horizons’ third edition of our literary magazine, Almanac, a home for discourse about the theatrical art form and industry during a time of ongoing transformation.

As we are writing this, the 2022/23 season has just ended, with a flurry of think pieces about a bleak future for the American theater, happening in lockstep with late-stage capitalism. And yes, this is a tough time for the kinds of American theater practices and forms to which we’ve become accustomed. But we wonder: if it’s true, as it’s been said, that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism – then maybe it’s also easier to imagine the end of theater than the end of our current model for it. And yet, imagining is what our favorite artists do best.

When we commissioned artists to contribute to this volume, we offered them the loose and optional thematic prompt of “liberated imagining” – i.e., proposals of futures that transcend despair and futility, and articulate new wishes or blueprints for a better world. How can we move past dystopian thoughts and recursive conversations about what’s broken – and move toward constructive visions of the future?

What emerged is a thought-provoking and delightful collection of essays, paintings, interviews, short plays, dialectic explorations, and poetic meditations from some of our favorite artists, including Jen Silverman, Shayok Misha Chowdhury, Vivian J.O. Barnes, Deirdre O’Connell, Vera Starbard, and L Morgan Lee, among others.

Alongside these pieces, you will also find probing and perceptive reflections on our five 2022/23 season productions from extraordinary thinkers in our community, including Jenny Zhang, Sarah Schulman, Haruna Lee, Sam Hunter, and David Adjmi.

…and, we have a special treat for you! Throughout last year’s edition, you could find a series called “Plays as Shapes,” in which playwrights drew the shape of one of their plays. This year, in a similar sweet experiment, we asked playwrights like Eisa Davis, David Henry Hwang, and Qui Nguyen to visually render their “artistic family tree.” This series is a unique look at how each bundle of inspirations nourished these theatermakers’ identities, and it articulates a sense of creative lineage for each of them. (Make sure to check out our very own Adam Greenfield’s tree, at the center of the magazine!)

So, while riding out the ripple effects of the pandemic, and coping with enormous financial hardship industry-wide, it certainly has not been an easy time to work in theater. But it has been – and continues to be – a deeply rewarding one. In our 2023/24 season, we will continue to offer productions and other programming which, we hope, will stick with you long after you’ve left our building on 42nd Street. We’d love for you to join in on this – and stay in the always-expanding conversation with us.

Sincerely,

Natasha and Lizzie

From the Artistic Director

Adam Greenfield

FAMILY: A VORTEX OF CONTRADICTIONS. A source of both security and danger. A safe haven and a war zone. It’s a collective body, but one which perpetually exists at odds with the individuality of its constituents. It’s an abstract idea, but acutely present and inescapable. And even in absentia, family keeps its grip.

Western drama has long fed on the torment of family life, but perhaps never so hungrily as in the theater of twentieth century America. The American family play, as a genre, has been so dominant on our stages that the family home has become a default setting. Lights up on a living room. At center, the sofa. Possibly an armchair. Upstage, a kitchen. Front door on one side, on the other a hallway leading to the rest of the house. Stairs leading to a second floor. A house, with one wall missing downstage: the petri dish of realism, where American life is scrutinized.

When setting out to program a season of plays, I never think of or aim for any unifying theme; I gravitate to each play for its distinct and idiosyncratic merits, and then do my best to fit it on a calendar. Often, though, in hindsight, over the course of producing that season, a common theme starts to emerge and surprise me. And so, sometime in the middle of our 2022/23 season, I came to realize that these five very singular plays work together as a contemplation of the idea of “home.”

At rise in Daniel Aukin’s production of Catch As Catch Can – the delicate, audacious play by Mia Chung which opened our season last October – the lights reveal an ordinary American home which, as the play progresses, deconstructs to become a psychological labyrinth. Tim Phelan has returned home to New England, a tremulous mess, exhausted, and hoping to find his footing. But his arrival only reveals the porous boundary between parent and child, as multiple characters begin to inhabit a single body (in a feat of genius dramaturgy), and as the physical space itself – home, previously a symbol of safety – becomes a crowded, claustrophobic maze of detritus and memory.

In Bruce Norris’s Downstate, a thin-walled halfway house in southern Illinois becomes an inescapable prison for four post-incarceration sex offenders. They live in exile; home is their haven, but a temporary one that allows no privacy and is under constant attack. At the end of the play’s first act, Dee, in a staggering performance from K. Todd Freeman, dances to Diana Ross (“it’s my house, and I live here”), looming behind him a window that’s been

smashed by hostile neighbors. Home promises the safety these men need, but it’s unattainable in a culture which blurs notions of justice and retribution.

In her epic origin story, The Trees, Agnes Borinsky rejects consensus definitions of home and offers a new one. The play opens on siblings David and Sheila, stumbling home from a mediocre party, and deciding – poignantly – not to return to Dad’s house that night, but instead to sleep outside in a public park, where – magically? – they take root. Over the course of the next seven years, home and family are redefined, as a new community forms and begins to promise a kind of utopia. But can a utopia stay both flexible and strong enough to live within hard-line reality?

Meanwhile in a half-scorched house somewhere in New Jersey, Julia Izumi’s Regretfully, So the Birds Are follows three adopted Asian-American siblings whose wacky, sociopathic parents have denied them any knowledge of where they come from. Izumi’s play is an absurd, explosive vision of home through the lens of an identity quest, which launches the siblings on a journey all over the world – to Cambodia, Nebraska, and high into the sky – on their search for home — or at least, for something to fill its absence. Director Jenny Koons’s staging featured

three fractured views of the family home: a physical reflection of their yearning for cohesion and completeness.

Finally, in a dilapidated house in Arizona – in a room saturated with memories and ghosts — John J. Caswell, Jr.’s Wet Brain flutters in the continuum of the American family play. Three siblings are chronically in battle, haunted by their parents’ self-annihilation, trapped in it. But in defiance of traditional, boozy, claustrophobic American realism, the walls of this house become permeable, weak against the family’s need to heal. Caswell’s play draws them up, and farther up, away from the living room, the kitchen, the armchair. It’s breathtaking, this break into freedom. As though the play itself is helping them there, and by extension, us.

I haven’t any brilliant take on what this inadvertent motif means, but it has got me thinking about our relationship with home in the year 2023, in the aftermath of the Covid Era when, for a time, home was our entire world. How are we changed, or changing? What do we need home to be now? What do we want home to be now? And what about its dominating presence on our stages; what does that say about us? I’ve heard it suggested that domestic plays are a tyranny over American theater, and I wonder if

the electricity I felt in this year’s season was that of writers pushing against our theatrical past, straining to break free from – or to find more space within – the domestic drama. Or a deepening of its continued pursuit to understand what makes us.

I think of a note from Arthur Miller, from a 1956 essay published in The Atlantic: “Now I should like to make the bald statement that all plays we call great, let alone those we call serious,” he wrote, “are ultimately involved with some aspect of a single problem. It is this: How may [one] make of the outside world a home? How and in what ways must [one] struggle, what must [one] strive to change and overcome within [oneself] and outside [oneself] if [one] is to find the safety, the surroundings of love, the ease of soul, the sense of identity and honor which, evidently, all [people] have connected in their memories with the idea of family?”

Mostly, though, I look back at the season grateful for the chance to have shared these five plays with our city, and with the extraordinary artists, practitioners, and audiences who came together to participate in these writers’ visions, and to ask the questions. A

CATCH AS CATCH CAN

Written by Mia Chung

Directed by Daniel Aukin

October – November 2022

What do we do when we don’t recognize someone we also know very well? When reality resists easy resolution — or a comfortable one—do we turn away? Find a new narrative? Widen our perceptions? How do we resolve the uncertainty and discomfort of the unresolvable? When grappling with experiences that resist language, how do we express them?

Mia Chung

Playwright’s Perspective: Catch as Catch Can

The Compulsion to Perform: Parents, Children, and Whiteness in Catch as Catch Can May Treuhaft-Ali

LON. The past’s the past, Rob. ROBBIE. Not really, Pop, not really.

It is true, in every play, that the bodies onstage change the story being told. An audience infers power dynamics from the relationships between characters based on their differences in age, race, and gender. The cadence of any playwright’s words changes depending on the voice that delivers them, which might be shaped by the actor’s ethnicity, geographic origins, or socioeconomic background. Even if these layers of meaning aren’t written into the script, they become inseparable from the audience’s perception of the characters.

This is the principle that Mia Chung points to when she writes, in the introductory notes to the script of Catch as Catch Can, “The theatrical doubling of character is core to

the play’s meaning.” Each actor plays two characters of different ages and genders, and so, no matter who is cast in each role, they must inhabit a character whose actual body would look different from their own. By dissociating each character’s gender and age from that of the actor playing them, the play posits that these attributes have little to do with physical appearance, and much more to do with the performance of identity. Through intergenerational theatrical doubling, in which each actor plays both a parent and their grown child, Mia invites us to consider the ways that familial legacy – including inherited values and assumptions around race and gender – dictate what “roles” we feel compelled to play in our everyday lives. This proposition was interrogated with rigorous artistry in the play’s world premiere in 2018 at Page 73, directed by Ken Rus Schmoll and featuring Jeff Biehl, Michael

Esper, and Jeanine Serralles. Our production explores it from a new angle by populating this story with an entirely Asian-American cast. In her script notes, Mia specifies that “the play can be performed by an all-white cast or a cast that is all of East Asian descent,” but that either way, “the actors perform white, working class, Irish-American, and Italian-American characters in New England.” When Asian-American actors embody these characters, they are not just playing across age and gender, but race as well. This casting conceit, therefore, highlights whiteness as an identity that the characters perform – and, ultimately, reveals the toll that this performance takes on them.

The concept that identity is a performance, rather than a fixed or inherent quality rooted in biology, was popularized by Judith Butler in her seminal book, Gender Trouble, published in 1990. Butler, a feminist scholar, theorizes that one’s gender is the cumulative effect of one’s actions, each of which might affirm or defy the gender norms associated with one’s physical features. These actions are sometimes conscious decisions, but more often are unconscious reiterations of culturally ingrained gender roles. Sociologist Nadine Ehlers builds upon Butler’s notions of performativity in her 2012 book Racial Imperatives, arguing that race is not a corporeal fact. Rather, Ehlers asserts that “racial discipline is sustained through the performative compulsions of race, and that all subjects are produced and produce themselves through a kind of labor (discipline) that can be seen as (performative) racial passing.” In other words, racial categories are precarious and mutable, and are only maintained when people’s actions conform to them. Again, those actions are socially learned and are rarely an expression of individual agency.

The Phelans and the Lavecchias, the two families we meet in Catch as Catch Can, are deeply connected to their respective Irish-American and Italian-American heritages. Both demographics have a historically complex relationship to whiteness: they were considered a separate (and inferior) race by white(r) Americans when they first immigrated to the United States, and they “earned” their whiteness through a series of strategic political alignments that can be seen as a collective form of performative racial passing.

When they arrived in the U.S. in the 1820s, Irish immigrants were relegated to ill-paying, dangerous jobs and poor living conditions. They were also subject to vitriolic stereotypes and physical attacks. This dynamic began to change in the 1850s, when Northern white workers became politically advantageous to the pro-slavery Democratic Party. In order to win national elections, they needed more voters in Northern states, and, since most middleand upper-class voters would not vote for a pro-slavery party, Southern plantation-owners made special appeals to Northern immigrant laborers for their support. Since the plantation-owners and immigrant laborers had few political interests in common, they formed a coalition over their shared sense of whiteness. In doing so, the Democratic Party worked to redefine whiteness as a matter of skin color, and not national origin. By relaxing one racial boundary, they were able to reinforce another: as historian Noel Ignatiev wrote in his 1995 book How the Irish Became White, “the assimilation of the Irish into the white race made it possible to maintain slavery.”

If adopting pro-slavery politics was one strategy for gaining acceptance from those in power, another was to

“

When Asian-American actors embody these characters, they are not just playing across age and gender, but race as well.

weave oneself into America’s origin story. The first large wave of Italian immigrants came to the U.S. in 1870, many of whom were from impoverished regions of southern Italy and Sicily. Similarly to the Irish, they were met with racist rhetoric that undermined their safety and barred them from jobs and adequate housing. In 1891, eleven Italian men were murdered by an angry mob in New Orleans, prompting Italy to break off diplomatic relations with the United States. In order to placate the Italian government, President James Harrison introduced Columbus Day as a one-time holiday. Brent Staples explains in his 2019 New York Times op-ed, “How Italians Became ‘White’,” that through the advocacy of Italian-American immigrants, Columbus Day became the annual institution we know today. They positioned Columbus as America’s first immigrant – a narrative that is clearly inaccurate on multiple accounts and obscures the violence he inflicted upon countless Indigenous Americans – in order to secure a higher status in American society and protect themselves from discrimination.

In a play about intergenerational legacies, these histories provide useful context for the Phelans’ and Lavecchias’ worldviews. They are deeply concerned with protecting their whiteness, namely by discouraging interracial marriages that might detract from its purity. Roberta Lavecchia, an Italian-American seamstress in her late 60s, feels a sense of relief that her son’s marriage ended before he could have children with his Korean ex-wife, even though she and her husband are willing to accept their relatives’ white Jewish and Polish-American romantic partners. The parents’ anxiety around accepting Asian-Americans into the family – an anxiety which the children internalize – is emblematic of the precarity of their white identity and their need to continually reify it through racist statements and exclusionary actions. Underlying this need is the inherited fear that, because whiteness is earned through performative racial passing, whiteness can be revoked if one fails to perform. The constant pressure to “produce” oneself “through a kind of labor,” in Ehlers’ words, is exhausting. Catch as Catch Can illuminates the cumulative effect of this exhaustion on parents and children alike.

Examining these characters in relation to the long American histories that have shaped them strengthens the play’s proposition that multiple generations live in each of our bodies, and that we perform race and gender the way we do because of the way our families live in us. With this play, Mia invites us to reflect on the histories we carry, the identities we enact, and the ancestors we bring to life through our actions. A

Caught Isaac Butler

0. Catch as Catch Can is a play in 15 scenes. On the surface, it could not be more simple. There are two families: the Italian-American Lavecchias and the Irish-American Phelans. They are working class and live in New England. The families are deeply intertwined, the children grew up together. Tim Phelan, the prodigal son who has been in California for over a decade, returns for mysterious reasons and announces he has a Korean-American fiancée, Minjung. Three actors play both the aging parents and their adult children. Yet the play is anything but straightforward. The three actors are not Irish-American or Italian-American but rather AsianAmerican. The first half is largely comic, at times quite broad, building to a riotous climax of a holiday dinner in which the three actors switch back and forth between their characters on a dime, sometimes seeming to play both at once. The second half is an increasingly dark and despairing drama in which ties between the characters come undone. The connections between these two halves are mysterious, and difficult to put into language. This is not a play where narrative moves along a line of clearly visible causality. It is hunting after a deeper, more mysterious, game.

1. This semester, I am teaching Shakespeare for the first time in many years. As a way of organizing the class and narrowing down which plays of his we are going to tackle, I decided to focus on Shakespeare and identity. College students love talking about identity, and I figured this would be an easy way into his work. We read some of the cross-dressing ones, and the three plays that significantly feature Moors, and of course The Tempest, because how could you not. Somewhat at the last minute, I decided to toss Hamlet onto the pile. I wanted to ask what does it mean to be a human being? I also wanted to know what does this play, which has been so central to our conception of the human subject, have to tell us about whiteness and maleness? After all, for so much of our history, when we ask what it is to be a human being we really meant what it is to be a white man. Whiteness and maleness were our assumed neutral, the mean from which everything else deviated.

2. ROBBIE: I mean, the goal’s to, like, to change yourself, to be different.

TIM: Right. But then: how will you know it’s the right self?

ROBBIE: …

Getting a little weird for me, Tim. – Catch as Catch Can, Scene 15

3. Being the neutral has all sorts of benefits, but it can leave you rather at sea over what your identity actually is. If you’re told over and over again that you are capable of being anything, it is also the case that you might be, well, nothing. A blank canvas isn’t all that interesting, except in terms of its limitless possibilities.

4. One running motif in Catch as Catch Can is the older generation’s attachment to certain pieces of Asian culture that appear to have washed onto the shore of their consciousness like treasures on a beach. Roberta visits a psychic with the name Glorisha who does the I Ching. Lon venerates Yamaha pianos.

5. Acting holds out the promise of self-transcendence. In the place where the actor and character meet, both are changed, both become more than they were before. This, at least, is what Konstantin Stanislavski taught. He believed that through a combination of rigorous research, physical training, textual analysis, imagination, and their own experiences as human beings, actors could reach beyond themselves and touch the peculiar individuals that they were playing. It was only this meeting of character and actor, which he called perezhivanie or experiencing that would allow for the most truthful, the most powerful, the most alive performances. This was a very different model from the mainstream of his time, which was more focused on types, and in actors working within whatever type suited them for the bulk of their careers.

6. As a Jew, I am both neutral and not. I am both white and not. I have a whiteness that can be revoked if it becomes inconvenient to the project of white supremacy. For some Jews, this creates an endless anxiety, a drive to reinforce their whiteness at the cost of people of color. For others, it fuels a desire to dismantle white supremacy. I like to think of myself as the latter kind of Jew, but I fear at times I may be the former without even realizing it. If whiteness is the neutral, it’s also the default, the reflex. To give one example of this: there are Black Jews—including my nephews— and the above paragraph completely ignores them.

7. We live at a time when identities are in flux. Or, to be more accurate, we live at a time when we have a heightened awareness of how in flux identities can be. Identities are always in flux, their boundaries are always renegotiated, always being policed and resisted and transgressed. Does an identity have intrinsic meaning or value? If so, what is it? What do categories like “Asian–American” or “Jewish” or “Italian-American” contain, exactly?

8. One reason we come to the theater is to see actors transcend themselves. It is a powerful thing to witness. We often feel trapped within the self, and, by transforming into the character, the actor helps us to feel on a deep level that perhaps some transformation of our own self is possible. The odd paradox is that the characters that the actors play are almost always trapped within themselves. So the act of performance gives us hope even as the content of that performance dashes it on the rocks. Thus the comic delights of Catch as Catch Can’s first half and the crushing bleakness of its second.

9. While we’re talking Stanislavski and transcendence and becoming other people and so on, I should probably mention that Stanislavski was a little fixated on Othello. He played Othello (and Shylock!) early in his career, and based his performance on an Arab merchant he met in Paris once. He wrote about Othello often. The prologue of An Actor Prepares is about Othello. In it, the young Stanislavski (who is named Tortsov) is trying to figure out how to play the Moor of Venice. Eventually he smears his face with chocolate frosting so that he can see how the whites of his teeth and eyes catch the light. He feels within this moment that he has discovered something. We have discovered something too, but not the thing that Stanislavski intended.

10. Does neutral exist? And what happens if something other than whiteness — and maleness — is treated as neutral? Catch as Catch Can playfully provokes both of these questions by having actors of East Asian descent portray white people. The opening of the play is a riot of stereotypes. In playing Roberta and Theresa, Jon Norman Schneider and Rob Yang wear whiteness like a mask. We know before the characters say more than a few lines that they are white women, that they are from New England, that they are in late middle age, that they do not come from money. It’s remarkable how much information about Roberta and Theresa can be derived from ten seconds of exposure to their accents, facial expressions, and gestures. But there is a second deployment of stereotypes—the exoticization of Asian women voiced by Roberta as she discusses Tim’s impending marriage to Minjung. It turns out her son Robbie’s ex-wife is also Korean. Asian women, she claims, are tighter than white women. They stay wet longer. Their vaginas are also horizontal instead of vertical. Five feet away, the actor Cindy Cheung, who plays Roberta’s husband Lon and daughter Daniela, sits, silently in place, dimly lit. In a few minutes, the lights will crossfade sharply and she will begin scene two as Lon. Watching her not respond to Roberta’s claims about Asian women — words that are written by an Asian woman to be voiced by a white woman played by an Asian man — we cannot help but have a heightened sense of… well, everything. Who is actually speaking? And who is listening? And who are we, to witness this? Every line begins to exist in multiple realities and contexts at once. The play, as comic as it is at this moment, is also a vertiginous, dizzying experience.

11. When I speak to acting teachers about their lives and jobs, the thing they often say they are worried about is the increasing constraints on who can play what. Yes, yes, they’ll say, practices like blackface are abhorrent. But must gay characters be played by gay actors? What about characters with disabilities? What about Jews? Or fat people? If transcendence is one of the goals of acting, one of its most powerful purposes, are we losing something if we insist too strenuously on a one-to-one correlation between actor and character when it comes to identity? I find these questions provocative and do not know a good answer to them. All I can usually say is that these are norms that are constantly being renegotiated, and that

the ongoing conversation about who can play what is a healthy one for us all to be having, regardless of the results. This is both true and feels like a cop-out, but the honest answer is I don’t know. I was furious when Ruth Bader Ginsberg was played by a British shiksa in On the Basis of Sex, but don’t really care about Louis in the most recent Angels in America revival being played by a straight Scottsman. I have no defined coherent ideology here, and I doubt most other people do either. What we have is deep-rooted, mysterious feelings, responses we cannot really control that we try to rationalize into something coherent. But we are incoherent, on this issue as in so many other things.

12. DANIELA: Sure, it’s easy to say I’ll be different, I see that hole and I’m not fallin’ in.

– Catch as Catch Can, Scene 3

13. The characters in Catch as Catch Can are burdened by whiteness, but they cannot see it. Whiteness is the air they breathe. Instead, they experience deep pain that comes from seemingly nowhere. They walk as if carrying great weight. They look tired all the time. The younger generation all yearn for some kind of escape, but everything feels like a trap, whether it’s a new job, or marriage, or parenthood. Their parents all yearn for the opposite: a stasis that never ends, a way of keeping their children and the world from changing. Neither is a real solution to the problem of being alive.

14. Stella Adler, the only American acting teacher to have studied directly with Stanislavski, often talked about what she called “modern drama.” These are plays, beginning with the naturalists of the late 19th century, where the characters are mysterious to themselves, ones in which unknowing is highlighted, rather than the kind of certainties the enlightenment ushered in. The problems in these plays cannot be solved, even when the plots resolve, because the problem is actually modernity itself. What these plays offer us is not a solution to the problem of living, but rather an experience of the problem of living, a new point of view on that problem. To paraphrase James Baldwin, they expose the questions that the answers have covered up.

15. One answer we cling to often is that identity is coherent, and that it offers us a home that we can carry with us, one that shelters us from the storm of the world. In Catch as Catch Can, Tim refers to Daniela as his home in the pivotal scene in which the play shifts from comedy to drama. The play reveals, first as farce, then as tragedy, that the various homes the characters live in — their physical homes, their families, their identities — don’t shelter them from anything. Instead, they leave the characters more trapped, more unable to navigate the world. In the second half of the play, the borders between characters break down, eventually even language breaks down. Daniela, in trying to express her pain, can only say “Ihh, Ihhca cah qwiy… Ahauhhughuh. Aoww uwwndu-uhuhuh. Mmm.” There is no language that can capture the terra incognita that the play has taken us all into. The answers have all imploded. Now we must find new questions to ask. A

Breaking the Curse Jenny Zhang

THE FIRST TIME someone showed me my astrological birth chart, I burst into tears. I didn’t know what the little symbols meant. (Later, I learned astrologers referred to them as “glyphs.”) It had to be explained to me that the cluster of blue curlicue script, of what looked like a capital M with a little upward arrow at the end, meant I had a “stellium” in the fixed water sign of Scorpio. Scorpio ruled really intense subjects like death and rebirth, as well as really disgusting subjects like bowels and toilets… and it was in my house of family and lineage. Another cluster of little diagonal red arrows with a horizontal line across was for the mutable fire sign of Sagittarius, that optimistic, (over) zealous, wandering centaur. Not knowing any of that at the time—what the glyphs were, or what the planets signified, or the meaning of the twelve houses that ancient astrologers had sectioned off the sky into, each “house” ruling over a variety of topics ranging from the self to others, romantic partners to open enemies, children, creativity, romance, pets, short and long-distance journeys, neighbors, spirituality, siblings, debts, inheritances, hidden sorrows, daily

routines, servitude, career, friendships, associations, insane asylums, prisons, labor, and finances—still, I was convinced what I was looking at was tragic.

The panoply of human experience—not just from life till death, but even events and occurrences that transpired before the moment of my existence and would continue after my death—all of it was contained in this document. Before me was a diagram of a circle with all kinds of lines, squiggles, numbers, colors and symbols that was meant to represent a snapshot of the sky at the moment my body was ejected out of my mother’s womb and into the world. I had no entry into deciphering what I was being shown, but I did know one thing: I was cursed.

Finally, I had what I was looking for. This was visual proof of my rotten fate. It was written in the stars, wasn’t it? That I was destined to be forever lonely. That I would die buried in regret. That love was unachievable for me. That no matter how hard I tried, I would continue to suffer endlessly. That it was too late for forgiveness, sanity, and acceptance… to say absolutely nothing about happiness,

stability, or fulfillment. I had gone looking for proof—it was the not knowing, the bouncing between wild hope and crushing disappointment that was unbearable. I just wanted to know. I just wanted someone to say: It’s not you, it’s your fate. There was something comforting about not being responsible for my own misery. If it had been decided for me by forces unfathomably larger than me, if it had all been determined before I even developed consciousness, then at least I wasn’t completely to blame.

Astrology makes a small but memorable cameo at the end of Mia Chung’s Catch as Catch Can. Two childhood friends Tim Phelan and Robbie Lavecchia study Tim’s birth chart. Robbie knows a little more than Tim about what the symbols and lines and numbers mean, but not much more. Tim finds his birth chart immensely interesting. Robbie thinks Tim is putting too much stock into it. I watched with recognition at how eagerly Tim wants someone to interpret his fate, to tell him exactly what he was working with. After a harrowing series of scenes where we find out that something is very, very wrong with Tim, that, in fact, something is very, very wrong with everyone, this moment stuck out to me. Maybe it meant nothing and maybe it meant absolutely everything, but I remember thinking this about my own birth chart: that analyzing and interpreting the zigzagging aspects between planets and the planetary movements was a fun reprieve from analyzing and interpreting the endless zigzagging that goes on in my own brain.

In Catch as Catch Can, three Asian American actors play Irish and Italian Americans, inhabiting both the role of the parent and the grown-up child. The actor who plays Tim Phelan also plays his mother Theresa. The actor who plays Robbie also plays his mother Roberta. The actor who plays Roberta’s husband Lon also plays his daughter Daniela. We are treated to a kaleidoscope of identities. Children become their parents, and parents become their children, sometimes in the same breath as the actors switch from son to mother, daughter to father, glib to serious, drunk to sober, cheerful to morbid, racist to curious, energetic to muted. What the audience gets is everything. At one point, as the Lavecchia family is getting ready for a major pre-Christmas holiday dinner celebration, things get tense, ancient family conflicts are stirred up, and Theresa Phelan, obliviously, or maybe not so obliviously, cuts through the tension by blithely dropping in a nugget about herself that no one asked for: “I love Swedish fish, but I have to be in the mood.” I laughed in deep recognition. Too often the realest thing anyone is willing to say among people they’ve known for years is a frivolous comment about candy preferences. Another reason why something like astrology can come as such a relief. It provides a structure that permits and even encourages questions like: “Do you struggle with love?” or “As a child, did you have to parent yourself?”

Like Tim, who confesses to Robbie, “Something broke, Rob. A long time ago. And it’s not getting fixed,” I had also confessed to a cherished friend about how broken I was, how there was no hope for me. Was it a confession or a challenge? I’m not sure anymore. My friend responded something to the effect of: If only real life were so simple. It would be nice if that was actually the whole story. Wow, I thought. She was right. It would be so much simpler if I were actually cursed.

There was a version of me that understood that and there was a version of me that refused and clung onto the

All these versions of me also contained echoes of my mother and my father and all the mothers and fathers before them… refracted and reflected and overlapping and subsuming and voided and crowding for space.

belief that I was, in fact, broken, and there was a version of me that stood on the shoulders of my ancestors and the people who raised me, and there was a version of me six feet under the ground, dragged down by everyone who came before me, and there was a version of me that wanted to be part of the world, and there was a version of me that was too weary to try, and there was a version of me that had so much still to live for, and there was a version of me that couldn’t do it again, and there was a version of me that believed in generational curses and who the fuck was I to think, that of all people, I would be the first to do things differently, to finally placate the ghosts and heal what my ancestors could not? There was a version of me that could go on and be a functioning member of society and a version of me that could not, and there was a version of me that clung to my ego and could not admit to what I did not know, good or bad, and there was a version of me that was humbled by the universe and could accept small and large kindnesses, that did not live in fear of the future nor in pain from the past. All these versions of me also contained echoes of my mother and my father and all the mothers and fathers before them… it was all in me, refracted and reflected and overlapping and subsuming and voided and crowding for space. And it’s the same for everyone. Which version will it be at any given moment? It’s hard to predict. But I know I have to be in the mood. A

Behind-the-scenes photos of the cast of Catch as Catch Can by Chelcie Parry. Production photography by Joan Marcus.

On Dystopias Jen Silverman

WHEN I WAS A TEENAGER, my martial arts teacher always told us that the gaze was everything. “Your fist goes where your eyes are looking,” he would say, meaning: don’t look away at the last second. And it was true – if we blinked or glanced away, the strike went off-course.

I think about this often in my adult life. It applies to so much else. Our bodies turn toward where we place our gaze. Even if we tell ourselves we’re thinking about something else, we drift closer. We can’t help it.

I wrote a Dystopian Play once, in grad school. A visiting playwright was in town, and one of their duties was to sit down with all of us one by one and discuss our work. By the time the playwright got to me, they were reasonably exhausted – by us as well as by the burdens of adult life in the theater. “Look,” they said (in my recollection). “I mean, just… Why?? Are you writing a dystopian play? What is the point? Aren’t there enough?” At the time, I was startled by their bluntness. But now, I have a real appreciation – both for their candor but also for the level of cultural exhaustion that makes an artist say, in their real voice and not their interior-monologue-voice: What is the point? Aren’t there enough?

It’s not that I’m against dystopian fictions. There is something to be said for processing our collective fears and traumas in narrative form. Numerous plays and films that I love have come out of these narratives.

But this is my question, for myself as well as you: in funneling our despair and frustration into dystopian world-building, are we also reinforcing our own worst ideas about ourselves and our potential for destruction? Do we create a sense of inevitability to the idea that things can only ever end in catastrophe? As we think about what is ahead, is there not power in placing our eyes on what we want to move toward? I don’t mean an optimistic take on the world we’re in; I mean: imagining a world that’s better than the one we’re in.

What happens if we imagine for ourselves abilities and capacities we don’t currently have? What if we imagine structures and communities our societies don’t yet hold? What if we place our narrative gaze there? Do we start to move toward it?

*

Theater makes alternate approaches to reality tangible and manifest. If theater is a place of concentrated communal witnessing, is that not an especially powerful space into which to place a vision?

We dream ourselves into physical spaces and then invite people to join us there. The experience of witnessing the world presented to us by a play is not wholly intellectual; it’s an embodied reality that lives in our breath, our heartbeat, the blood and meat of our bodies reacting. What feels real is, to our bodies, real. And thus we might physically experience life inside a world that, beforehand, we couldn’t bring ourselves to imagine existing.

Maybe the opposite of dystopia is the process by which we imagine what we most need to thrive, and then invite other people to join us there.

*

When Taylor Mac did A 24-Decade History Of Popular Music at St. Ann’s Warehouse in 2016, there was a moment in which I looked around the packed theater and I saw so many kinds of queer bodies. Bodies that had brought themselves into being. I could see the labor on them: a labor of self-dreaming and self-knowing made manifest in scalp and ink, sequin or denim, clothing as armor or bare skin as clothing, gender blurred or brought into striking focus. A language of self-declaration that so many of us first learned to speak at a whisper, or in code. In that vibrating room, every body was out loud. Taylor Mac was singing songs from the past, and we were gathered in the present, but in that moment of gazing around me, I saw the future. A kind of future. One possible future.

*

Something I love: the defiant, expansive, restless imagination that I see in queer artists, in queers who are not artists, in people who have survived and built a means of thriving inside a culture that was not made for their safety or happiness.

There is a thing that happens to you – slowly, grindingly, over time - when you live in a country where your existence is subject to public debate. More than that: where your identity is something so dangerous that it must

be regulated or disbelieved – or regulated by disbelief. We could talk of the most obvious violences, but let me describe a different and subtler one: an exhaustion that always lives under the bones. The tendency to question yourself before someone else even gets around to questioning you: Am I really what I think I am? Am I sure? What are the consequences? Is it worth it? You might argue yourself into nonexistence before someone else can even get there.

But here is something else that happens. You learn – in equally bone-deep ways – that you cannot trust society’s reflection back to you of what you are and what is possible for you. You can’t trust it, nor do you require it. It just doesn’t apply. It’s a story in a language that does not describe you. And when you realize that, a kind of constraint goes away, and suddenly you are in a space in which your imagination is larger than the cultural imagination that surrounds you.

There is a freedom in that, I think. Many of us are destroyed by it, or are destroyed before we get to it. But those who aren’t seem able to access a singular vision and reach. I see how they fling open doors for the rest of us and say: Come see what it looks like over here.

There is a depth of imagination tied to survival: physical, spiritual and cultural. As humans, our imagination becomes more profound and muscular when it is also our means of salvation.

When I first read Andrea Lawlor’s astonishing Paul Takes The Form of A Mortal Girl, I thought: Somebody is speaking to me. I have waited my whole life for somebody to speak to me in this way.

Paul Takes the Form is set in the mid-90s, but it opens up a window on the future. The titular Paul is a shapeshifter, a polymath who radiates curiosity and desire… and who shifts between genders. Paul is also Polly. Polly/Paul is witty and bold and sometimes arrogant and often vulnerable. Paul is not a different person when Polly, Paul just has access to a whole other side of human experience, in large part because he is seen and treated differently by others.

Paul is not a pretender except for the ways in which all humans who want to be loved are pretenders. Paul is not sad except for the ways in which all humans get sad. Paul is not punished for the audacity to be fluid and multiplicitous; though Paul gets a bit heartbroken in the way that all of us do, he also gets wiser, more joyful. Paul is a story about queerness that is also the story of somebody who has a thrilling and truthful future, in part because he wouldn’t settle for anything less.

In a book that combines casual fisting with philosophy, what seems to me most subversive of all is that Lawlor uses the pronoun “he” for Paul/Polly throughout. And what this does, instead of driving home the idea that Paul is “really” a boy, is that it takes the pronoun and renders it meaningless. “He” becomes repurposed and stretched and shifted until all of a sudden it means a million things

and nothing at all. I was talking with someone about this book the other day, and they said: “The thing about Paul is that he… she… they… fuck it! – are so joyful.”

And I thought: that “fuck it” is my utopian future.

I thought: I want to live in a world where I get to be Paul.

Monica Byrne’s 2021 novel, The Actual Star, is set in a future where the population is made up of nomadic climate refugees whose highest religion is one of mutual aid. This is a world that has eradicated power differentials in terms of how different bodies are perceived or acted upon by systems of governance. Though there are many bodies who have inabilities, all have access to supportive technologies that make up for what they lack, creating unfettered and equal access to community. In this way, characters have inability without disability, and this is part of a larger framework in which bodies are not seen as sites of virtue or failure, strength or weakness. They’re just bodies –supplemented as needed, each in a different way.

This vision stayed with me long after I finished the book: a future where there is no loaded meaning afforded to any one kind of body. A future in which all bodies have become sites of transformation, possibility, and play. *

What am I looking for?

Stories that dream. Stories that conjure. Is this what I mean?

Stories in which reality flickers and there is a new thought on the other side, a truly new thought.

*

If you’re driving down a highway and you look to the side, eventually you’ll swerve. You won’t be able to help it. Like my teacher said all those years ago: you can’t move forward if you’re looking somewhere else.

These days, I’m trying to figure out what it means to look straight ahead, at a horizon-line I can’t make out. I’m trying to understand what it takes to get there – what are the vehicles by which one travels? How do we ensure that it’s not all rubble when we get there?

What theater offers us is the act of boundless dreaming made concrete: the door left open, the seats awaiting those who wish to dream with us.

I used to joke with my non-arts friends that they were doctors and teachers and scientists and my calling was “make believe.” That’s still true, but to my own surprise, I’ve come to have an abiding respect for the make believe: the labor in the verb Make, the vital difficulty in the word Believe

How can we move forward without believing that something better is ahead? What better future can we believe in, so that it can be made? A

Revisiting A Memory

L

Morgan Lee

It’s late. The middle of the night. You’re six years old.

Laying in bed, looking up at a somewhat plain, off-white ceiling, In a somewhat plain, tan and brown room. Alone.

A faint glow from the moon peeks through the blinds, casting light on a colorful “He-Man: Masters of the Universe” comforter set and a stream of sparkling tears running down your face and onto the pillow.

“If only I could wake up and be a girl things would all be easier.”

This isn’t the first night you’ve cried. But it IS the first time you’ve said these words out loud. I know…

You’re a good kid.

You’re kind. You smile. You get good grades. People like you.

You don’t want to make a fuss.

“If only I could wake up and be a girl things would all be easier.”

Six years old. First grade. It’s not about your body or that you are miserable in it. You’re not. It’s all you know. But something… Some thing Something is off.

You get lost in fantasies of waking up... Putting on the dress mom bought you at the department store that weekend, Doing your hair – pigtails with bright colored barrettes. (But not too many like cousin Sherri.)

You grab your book bag with the pink Trapper Keeper inside –Or maybe it’s purple, you like purple.

You walk into the classroom. Your teacher smiles.

No one stares or laughs.

No one whispers to their friends about you. No one says your voice is too high or tells you to act like a boy. It’s easy. Finally.

Everything would make sense.

You would make sense. But that’s not possible.

It goes against everything you’ve been taught. When you were born, the doctor told your parents what you are. Doctors are right. They are the smartest. They know everything. Why are you even questioning? It’s not possible. Again, People like you. Don’t make a fuss.

So…

Rather than tell anyone about these feelings, You simply whisper it to your ceiling. Alone. in the middle of the night. Knowing not a soul will hear you.

“If only I could wake up and be a girl things would all be easier.”

Guess what kiddo…

One day you do.

It takes a while A long while (Maybe too long)

But there comes a day when you’ll say it out loud – Where others can hear. Where others also share similar feelings and live out loud and you don’t feel alone. (Well, at least not for that.)

I won’t go into the details of your life and the journey to she Because I believe you need nights like this to get there. But kind and gentle youngster… I will share this with you:

There is joy.

You know those dreams you have where you’re able to fly? There are moments that feel that way in real life. I started this letter sitting in a hotel in London. Yes, that London. England. I’m an actress. Now some people prefer a non-gendered use of the word (actor) but this is MY letter to you, and being called an “actress” makes me feel pretty swell. I live in New York City. I get to do what you see people on the floor model TV doing. Like The Wizard of Oz… or Fame or Meet me in St. Louis or Grease 2 (but mostly like Fame.)

(Yes, it’s an actual job. They got paid.)

Much like that night in bed, The glow from my laptop screen is shining into my face, tears streaming as I type. But I don’t cry because things feel off. I cry because one day you figured it out.

It might seem impossible to believe this… But I’m you.

Many years later.

(Don’t ask how many.)

Yes.

You.

I remember that night. I remember… Wondering. Dreaming. Dozing off. Back to sleep. Thoughts tucked away.

Mom loves you. The family loves you. Some of them will never truly understand. But the things you are afraid of won’t happen. (They don’t abandon you.)

Many girls like us don’t get that. Girls like us.

Us.

“If only I could wake up and be a girl things would all be easier.”

We live in a “man’s world”. So in many ways, they’re more challenging Girls. Women. particularly Black girls. Black women and the things that harm us Things we want to bring up in conversation Seem to (more often than not) fall on deaf ears. People’s eyes glaze over as they don’t hear what they expected to hear (assumed they’d hear) as they realize my thoughts might ask them to stretch to consider things that don’t center what they already know (that don’t center them) or that don’t align with what society has told them my experience is supposed to be. I am inconvenient.

“If only I could wake up and be a girl things would all be easier.”

There are people who will use you. Who will use your identity for checkmarks and trophies Who exploit our pain, our lives, our wins, our voices for points in the campaign for the world to know how great they are. How evolved How they’ve done “the work”. They will never ask. They will never ask… and yet claim they know They will make moves to sweep hurt under the rug

To make questions disappear. Some call themselves “allies”. Look out for them.

There are also people who care. Who will take time to get to know you

To hear you, To love you, To ask you…

For whom that will not be “work”

Look out for them.

Treasure them.

“If only I could wake up and be a girl things would all be easier.”

You will meet an artist.

A Lady.

She is a songwriter. She is a moment.

Her music will crawl into your soul and shine light. It will heal people.

Years later you’ll realize why singing her music touched you so deeply.

She is transgender.

You are transgender.

(It’s a word you don’t know now.)

I wish you did. It’s beautiful.

We are beautiful.

The reason you feel different than everyone else is because the world teaches us about cis people (another word you don’t know yet…)

(People think it’s obnoxious.)

(People are obnoxious.)

Anyway, Cis people.

We are socialized to center them

They are incredible (they’ve had centuries in the light) but there is more… YOU are more.

The world doesn’t celebrate the nuance of being us. (yet.)

That doesn’t mean we can’t.

Six years old.

Your whole life ahead of you…

So many new chapters to come. Stay kind. Keep studying. Keep dreaming. Don’t skip ballet.

Yes, one day you’ll take ballet class.

(Yes, tights and all. I told you…like Fame.)

One day, you’re gonna be tempted to pluck your own eyebrows. Don’t. Surprised is NOT “the look.”

Oh, one last thing Hug Dad extra tight the next time you see him.

Remember his hugs.

He loves you so much. You know that.

But love on him more anyway.

(For me.)

“If only I could wake up and be a girl…”

The day will come when you realize You always were. A

ARTISTIC FAMILY TREES

As a theater fueled by visionary playwrights, we’re constantly curious about how they became the theatermakers we so deeply admire. Who are their heroes, mentors, touchstones - from theater and beyond? What cultural movements or ideologies have impacted their perspectives? A traditional family tree offers a visual sense of familial lineage, which made us wonder about what an “artistic family tree” might look like. So, we asked some of our favorite playwrights... check out their visual responses throughout this volume of Almanac! – Natasha and Lizzie

CÉSAR ALVAREZ

I like that the game Candy Land requires absolutely no skill. Its primary function is to teach toddlers how to take turns, all while hypnotized by psychedelic pictures of candy. At no point in the game do you make any choice or implement any strategy, which ensures that toddlers can beat the big kids. It’s tempting to think of my own artistic journey as a series of colorful and bizarre inevitabilities. Sure, I made decisions, but there is a sublime serendipity to finding this long string of nerdy musical activities. When I line them all up they look like a treasure map to mutant musicals. My artistic family tree is a beanstalk. My leaves are the artists that fed me sunlight. My path was a rainbow road of band geekery. The fruit may be tricky to put on stage, but at least it’s psychedelic.

Eisa Davis

I am born of music and lyric, nature and strong kindness. I have always felt redwood trees to be my relatives, but drawing one is above my pay grade. Instead this is a nice afro oak rooted in nurturing home soil, filled with the people, practices, groups, and sounds that grew me. There isn’t space to put every single teacher, relationship or artwork, so let them be the unseen leaves. The top of the tree is waiting for more branches yet to grow.

DOWNSTATE

Written by Bruce Norris

Directed by Pam MacKinnon

October 2022 – January 2023

“

When we sit in the dark and watch the lives of other people in front of us, things can get complicated. And, if you ask me, the complicated questions – the ones we don’t have easy answers for – are exactly the ones we need to be asking ourselves right now.

Bruce Norris

The playwright on Downstate

American Tragedy Lizzie Stern

THERE ARE SOME PROBLEMS IN LIFE that go unresolved. Far more challenging, though, are the ones that go unrecognized. We suffer and don’t know why; we try to feel better and have hope for the future, but have no idea where to begin. So we reach for greater understanding of ourselves, one another, and the systems in which we operate. This is why we go to the theater.

In the 5th century BCE, Agamemnon by Aeschylus premiered in Athens. It was the first tragedy in a trilogy, the Oresteia, the plot of which is – strap in – as follows: Agamemnon sentences his daughter to death so that the Greeks can win the war. Then, his wife, Clytemnestra, murders him for having murdered their daughter. Next, their son, Orestes – who has grown up tortured by the fact that his mother killed his father – kills his mother. And, finally, the Furies – three goddesses who represent justice – pursue Orestes for killing his mother, but (in a twist of yet more divine intervention) they do not kill him. There is mercy. And this mercy ends the violent cycle of retribution.

The Oresteia is not a soapy revenge drama. It is Tragedy. With a capital T.

Tragedy is an inquiry into the human condition: our blind spots and fatal flaws, our agony, grief, and despair, our struggle to navigate conflicts when life feels incoherent and reconciliation is impossible. It is an examination of the tortured relationship between forgiveness and vengeance, and between mercy and injustice. It is, in other words, a confrontation with the greatest impasses in ourselves and in society.

Downstate by Bruce Norris is Tragedy.

The play unfolds over the course of 24 hours inside a halfway house where four sex offenders live south of Chicago. The story begins when Andy, an adult survivor, confronts his childhood abuser, Fred. Andy tells Fred, haltingly, why he is – or, more importantly, is not – there:

ANDY: [Y]ou will never be deserving of sympathy, or forgiveness . . . That is not something … I can give you. But I must remember to forgive myself, and remember that I was only a child, and to treat myself with the same respect and loving kindness that any child deserves.

For Andy, there is no amount of apology or reformation that could undo the lifetime of, as Andy puts it, “guilt and shame” which directly resulted from Fred’s abuse. The damage is done. Forgiveness is unavailable, irrelevant, neither Andy’s objective nor the play’s action.

And how cruelly true this is about life, that the conditions which make forgiveness most transformative are the very same which make forgiveness impossible. We suffer at the impasse of irresolution, trapped in the prison of the past, desperate for a countervailing force that can compensate for our personal sense of powerlessness in the face of abuse, and interrupt cycles of hurt. What can answer this calling?

The law, at its best, might. Lawyer and social justice activist Bryan Stevenson offers a framework which allows the law to remain separate and apart from the realm of forgiveness, without sacrificing our humanity – even and especially in situations of extraordinary wrong. That framework is what he calls “just mercy.” In his 2014 book of the same title, Stevenson defines the term as a kind of compassionate understanding – which can, sometimes, manifest in policy – which uniquely “belongs to the undeserving.” The purpose

behind it, Stevenson argues, is that when we find mercy for people when it seems least warranted or expected, we have the power to “break the cycle of victimization and victimhood, retribution and suffering” which plague society.

If we follow Stevenson’s argument, then mercy for sex offenders – some of the most “undeserving” – would not preclude reparation for survivors or accountability for perpetrators. It could, in fact, facilitate resolution on the collective level when it is unavailable on the individual level.

But this is not how America operates.

In a 2019 episode of the podcast, “You’re Wrong About,” hosts Sarah Marshall and Michael Hobbes analyze America’s treatment of sex offenders. The episode builds on an article Hobbes had just written, for The Huffington Post, called “Sex Offender Registries Don’t Keep Kids Safe, But Politicians Keep Expanding Them Anyway,” exposing how the punishment meted out to them is biased, draconian, and ineffectual. I’ll share a few points from Hobbes’s research.

State registries, across the country, restrict sex offenders from living in 99% of homes because they are within 1,000 feet of a school, church, or other place where children spend time. But, of course, this restriction does not actually keep children safe; 1,000 feet is about a five-minute walk, and the law can only regulate where sex offenders live, not where they go. In fact, by increasing the likelihood of homelessness and unemployment, these restrictions make it more probable that sex offenders will end up camping out in restricted areas. And the enforcement of these policies is full of hypocrisy and racism. State registries are disproportionately black and poor, but, when dealing with white billionaire pedophiles like Jeffrey Epstein, local prosecutors and judges tend to impose fewer and less severe restrictions.

In study after study, it is clear that this area of public policy is rippling with weaponized dysfunction. It fails to prevent abuse, and, by financially prioritizing its current tactics over resources for survivors, it fails to repair and restore. As Marshall observes: “This idea that we are going to solve the problem by removing the contagion, this is not a contagion-based problem. This is something in the human that we need to figure out how to manage.”

The system, as it is, may seem to satisfy a basic human need to externalize and extinguish the most irredeemable parts of our society, so as to preserve a sense of order in our world and in ourselves. But this shadow-self projection is a fallacy that only serves to amplify the personal sense of failure we feel in the face of abuse as we try to resolve what is unresolvable, to find somewhere to put it all – and realize there is nowhere.

This is not justice. This is the stuff of Tragedy.

In 2015, when we produced The Christians by Lucas Hnath, Adam Greenfield wrote an essay about Tragedy and helplessness. Here is 2015-Adam: “Tragedy arises when we become aware of a fissure in the world, a crack or conflict that can never be reconciled. . . we witness a character who employs his/her complete self to engage in that conflict, only to recognize that it’s the human condition in a universe which will always be beyond our comprehension.”

Downstate is an appeal not for reconciliation, but recognition. It is an autopsy of our broken shared humanity. A plea to witness problems that cannot be solved and people who cannot be redeemed and yet – still, always – can be more fully understood.

Maybe that is a kind of mercy. A