ALMANAC

ALMANAC

Almanac is a literary magazine from Playwrights Horizons. Established in 2020, at a time of pandemic and protest, Almanac is a new kind of publication — one in which a theater and the artists who comprise it come together to take stock of contemporary politics, culture, and playwriting. Through plays, essays, interviews, poems, and visual art, Almanac charts the coordinates of the present day, as measured by thinkers and makers whose work lives both on and beyond the stage.

EDITORIAL BOARD

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Natasha Sinha

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

Adam Greenfield

EDITOR

Billy McEntee

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Lizzie Stern

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING

Teresa Bayer

EDITOR Fiona Selmi

GRAPHIC DESIGNER Jordan Best

DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Alison Koch

EDITOR May Treuhaft-Ali

ALMANAC PLAYWRIGHTS HORIZONS 416 W 42ND ST, NEW YORK, NY 10036

Copyright © 2022 Playwrights Horizons, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed by Michael Harrison of WestprintNY. Almanac has received generous support from The Liman Foundation.

Contributors

WILL ARBERY is a playwright and screenwriter. Playwrights Horizons: Heroes of the Fourth Turning (Pulitzer finalist, Obie, Lortel, NY Drama Critics Circle Award), Corsicana (NY Times Critic’s Pick). Other plays include Plano (Clubbed Thumb), Evanston Salt Costs Climbing (The New Group), and Wheelchair (3 Hole Press). He’s currently a writer on “Succession” (HBO).

JORDAN BEST is the Graphic Design Manager and artwork designer for Playwrights Horizons.

AGNES BORINSKY is a writer living in Los Angeles.

CHRISTOPHER CHEN is a San Francisco native whose plays include The Headlands (LCT3/Lincoln Center Theater), Passage (The Wilma, Soho Rep), The Late Wedding (Crowded Fire) and Caught (InterAct, The Play Company), which won an OBIE Award for Playwriting. Chris currently has an overall deal at Amazon TV.

MIA CHUNG’s Catch as Catch Can premiered at Playwrights Horizons Fall 2022; Page 73 world premiere. Ball in the Air (NAATCO/Public Theater 2022). Double Take (Almanac 2021). This Exquisite Corpse (multiple awards). You For Me For You (Royal Court, National Theatre Company of Korea, Woolly Mammoth, multiple regionals. Published: Bloomsbury Methuen.)

JORGE IGNACIO CORTIÑAS’s plays include Recent Alien Abductions (Humana Festival, Tripwire Harlot Press), Bird in the Hand (Fulcrum, NY Times Critics Pick) and Blind Mouth Singing (NAATCO, NY Times Critics Pick). His many awards include fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, United States Artists, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

MEXTLY COUZIN (she/ella) is a Lighting Designer. Credits, Broadway: Roundabout. Off-Broadway: Second Stage, Bushwick Starr, MCC, Playwrights Horizons, Clubbed Thumb. Regional: Opera Parallèle, Center Theater Group, The Old Globe, Repertory Theatre St. Louis, Oregon Shakespeare Festival, La Jolla Playhouse, San Diego Symphony, Malashock Dance Company. MFA, University of California, San Diego 2020. mextlycouzin.com

ADAM COY is a Tejano director, curator of vibes, and actor. Adam serves on The Fled’s leadership circle and is the Associate Artistic Director of Egg & Spoon Theatre Collective. The Playwrights Horizons Directing Fellow, a TCG Rising Leader of Color, a member of Theater Producers of Color.

ANAÏS DUPLAN is a trans* poet, curator, and artist. He is the author of I NEED MUSIC (Action Books, 2021), and a book of essays, Blackspace: On the Poetics of an Afrofuture (Black Ocean, 2020). Duplan is the founding curator of the Center for Afrofuturist Studies, an artist residency program for artists of color.

ADAM GREENFIELD is Artistic Director of Playwrights Horizons and a dork about crosswords.

DEEPALI GUPTA is a performance artist and theater practitioner. Her work circulates ideas around madness relating to the colonized and feminized body. She works in (dis)order to upheave and unravel. Her work has been supported by the Brooklyn Arts Council, NYSCA, and the NYC Women’s Fund.

RYAN J. HADDAD is an actor and playwright. His play Hi, Are You Single? recently completed a run at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, and his new play Dark Disabled Stories will debut in the 2022-23 season at The Public Theater, produced by The Bushwick Starr. His TV credits include “The Politician” and the upcoming FX miniseries “Retreat.”

ALESHEA HARRIS’s plays include Is God Is, What to Send Up When it Goes Down, and On Sugarland

DAVE HARRIS is a poet and playwright from West Philly. Selected plays include Tambo & Bones (Playwrights Horizons, Center Theatre Group, 2022), Exception To The Rule (Roundabout Theatre Company, 2022), and Everybody Black (Humana Festival 2019).

JORDAN HARRISON’s Playwrights Horizons productions include Doris to Darlene, Maple and Vine, Log Cabin, and Marjorie Prime (Pulitzer Prize finalist). TV credits include “Orange is the New Black,” “GLOW,” and “Dispatches from Elsewhere.” In 7th grade, he won a blue ribbon in the drawing competition at the Martha’s Vineyard Agricultural Fair, and received a check for four dollars and twelve cents.

SYLVIA KHOURY’s plays include Selling Kabul (Playwrights Horizons, Williamstown Theater Festival), Power Strip (LCT3), and Against the Hillside (Ensemble Studio Theater). Awards include Pulitzer Prize Finalist (Selling Kabul) and Whiting Award for Drama. Education: M.D. (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai), M.F.A. (New School for Drama), B.A. (Columbia University).

ABE KOOGLER’s produced plays include Fulfillment Center (Manhattan Theatre Club), Kill Floor (LCT3), Lisa, My Friend (Kitchen Dog), Blue Skies Process (Goodman Theatre’s New Stages), and Advance Man (UTNT). Awards: Obie Award for Playwriting, Weissberger Award, DG’s Lanford Wilson Award. MFA: UT-Austin, Juilliard. He also works as a political speechwriter.

Contributors

MARTYNA MAJOK was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for her play, Cost of Living, which debuted on Broadway fall of 2022. Other plays include Sanctuary City, Queens, and Ironbound. Martyna is currently writing a musical adaptation of The Great Gatsby, with music by Florence Welch and Thomas Bartlett, and developing projects for TV and film.

DEB MARGOLIN is a playwright, actor, and professor of theater. She lives in New Jersey, which she denies. Obie Award for Sustained Excellence of Performance; Kesselring Prize for her play Three Seconds in the Key.

MARA NELSON-GREENBERG’s work has been developed at Playwrights Horizons, Clubbed Thumb and Ensemble Studio Theatre, among others. Her play Do You Feel Anger? was produced at the Vineyard Theatre in 2019.

MEL NG (she/her) is a queer artist, costume designer and poet who splits her time between New York and Honolulu. Outside of the theater, you can find her swimming, giving tarot readings, writing poetry and practicing reiki. She believes in the transformative and healing power of ritual, and that sensitivity nourishes her work in creative spaces. melissaavang.com

HEATHER RAFFO is a singular and outstanding voice in the American Theater whose work has been championed by The New Yorker as “an example of how art can remake the world”. An Iraqi with American roots, she is a multiaward-winning playwright and actress whose work has taken her from the Kennedy Center to the U.S. Islamic World Forum, and from London’s House of Lords to stages nationally and internationally. Her newly released anthology, Heather Raffo’s Iraq Plays: The Things That Can’t Be Said, brings together Raffo’s groundbreaking contribution not only to the American Theater but gives voice to nearly two decades of reshaped cultural and national identity for both Americans and Iraqis since the events of 9/11.

SARAH RUHL is a playwright, essayist and poet. She’s written 12 plays that have been done on and off Broadway and internationally. She has been a two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist and a Tony award nominee. Recently, she published Smile, a memoir, which Time magazine listed as a mustread book of 2021. Her most recent book is Love Poems in Quarantine. Awards: Steinberg award, the Sam French award, the Susan Smith Blackburn award, the Whiting award, the Lilly Award, a PEN award for mid-career playwrights, and the MacArthur award.

HEIDI SCHRECK is a writer / performer living in Brooklyn with her partner Kip Fagan and their awesome twin daughters. Her latest play What the Constitution Means to Me was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and played an extended run on Broadway before touring the country.

AYDAN SHAHD (they/he) is a dramaturg of classical and new work, a former Playwrights Horizons Artistic Fellow, and a current PhD student at the University of Chicago.

NATASHA SINHA is Associate Artistic Director of Playwrights Horizons, and co-founder of Beehive Dramaturgy Studio and Amplifying Activists Together.

LIZZIE STERN is the Literary Director at Playwrights Horizons.

ARI TEPLITZ, CFP®, ChFC®Managing Member, Teplitz Financial Group. Ari is an award-winning financial planner who works with artists on becoming better financial consumers. A graduate of the Yale School of Drama, Ari is a passionate advocate for personal financial wellness. Ari takes a two-pronged approach to achieving financial freedom—helping clients eliminate current financial stress while also creating good long-term financial habits.

JIA TOLENTINO is a staff writer at The New Yorker and the author of the essay collection Trick Mirror.

SANAZ TOOSSI is an Iranian-American playwright, whose plays include the award-winning English (co-production Atlantic Theater /Roundabout) and Wish You Were Here (Playwrights Horizons, Williamstown/Audible). TV credits include “A League of Their Own” (Amazon). Sanaz was the 2019 P73 Playwriting Fellow, a recipient of the 2020 Steinberg Playwright Award, and the 2022 recipient of The Horton Foote Award. MFA: NYU Tisch.

ANNE WASHBURN’s plays include 10 out of 12, Antlia Pneumatica, Apparition, The Communist Dracula Pageant, A Devil At Noon, I Have Loved Strangers, The Internationalist, The Ladies, Little Bunny Foo Foo, Mr. Burns, Shipwreck, The Small, and transadaptations of Euripides’ Orestes & Iphigenia in Aulis.

DAVID ZHENG is a playwright and visual artist from The Bronx. His work has been developed at The Public Theater, New York Theatre Workshop, Eugene O’Neill Theater Center, MCC Theater, The Lark, and many others. He enjoys snowboarding, ordering too much food for the table and, most recently, been obsessed with Pickleball. David is currently developing an original pilot with Tristar at Sony Pictures.

Letter from the Editors

Natasha Sinha and Lizzie Stern

WELCOME TO THE SECOND EDITION of Playwrights Horizons’ Almanac, a celebration of artistic discourse from our 2021-2022 season. In these pages, you’ll find a trove of artists’ sage articulations and witty insights during this extraordinary era of returning to the theater. We are writing this while in the swing of our second season since the pandemic began, reflecting on how we first pushed open the gates of isolation and lockdown, and forged forward onto a path both gratifyingly familiar and deeply unknown.

Back when we were all still at home, and our building on 42nd Street was dark and vacant, Almanac first emerged as an album of reflections on the profound challenges of that moment – and all that we imagined on the other side. Immersing ourselves in the observations and visions of artists became, for us, the most meaningful way we could keep going while staying off the stage.

Now, we’re back! But, the pandemic changed us, in many ways. Restarting our producing engines called for a recommitment to the art; we experienced a reignition of passion for theater-making, alongside a loss of stamina. A delight in spending our days with artists, alongside frustration at confusing COVID guidance. A relief at planning new gatherings and celebrations, alongside leaner budgets. We weren’t so naive as to expect pure joy upon reopening our doors – but the terrain of the 2021-2022 season was even more full of challenge and mystery than we expected.

This complexity is something we honor in Almanac, which now – finally – can exist in relationship with not only the brilliant thinkers who create our new work, but the new work itself: the plays on our two stages, the developmental workshops in our rehearsal studios, and the engagement with our audiences.

So, in this edition, beautifully designed by Graphic Design Manager Jordan Best, you will again discover a selection of original pieces by great thinkers: personal essays, collages, poems, short plays and – arguably our personal favorite – full-length plays rendered in a way you’ve never seen before. When we commissioned these artists to contribute, we offered them a simple and optional prompt: change. The transformation of the artist. The shift in institutional values and priorities. The regeneration of theater, community, and New York City.

And we wanted to try something new: we invited members of our community to write personal responses to productions in our season. In doing so, we hope to foster a unique form of theatrical journalism: one rooted not in judgment or efficient distillation, but in impressionability and self-expansion. In the pages that follow, you’ll find a letter from Heidi Schreck, a poem by Anaïs Duplan, and an essay by Jia Tolentino, among many others. These writers capture what is infinite and ineffable, from an array of perspectives, about going to the theater: the air that surrounds a play – and all the complex, self-contradicting insights and emotions it elicits. There is rigor and courage in their explorations: it is, we believe, a greater challenge to observe art – as well as life – from a place of vulnerability rather than authority. Altogether, these pieces offer a new critical landscape that is rich with multiplicity, and reflect the scope of our previous season not through a lens but, rather, through a prism.

So much, indeed, has changed in the last few years. Thousands of people have left the theater, and thousands have joined. Institutions have faced the largest deficits since the great recession – forcing all of us to reprioritize and rethink vast and ingrained producing models.

But the theater, even and especially during its most challenging moments, retains its power of collective rejuvenation: we come together, reflect deeply, shift perspective, and release ourselves from routine rhythms – exiting the space not quite the same as when we entered it.

Almanac is a sampling – or, perhaps, a distillation – of the self-reflective and dynamic conversation that can happen around any theater anytime anyone sees a play. An innovative artist imagines infinite possibilities, and then renders a clear vision that inspires and sustains the rest of us. This is the horizon line that gives us our name. And it is our great hope that, in the pages that follow, we can bring us all a little closer to it. A

Welcome Letter Adam Greenfield

FOR 18 MONTHS, live theater was unthinkable. An art form reliant on the shared experience of a crowd, theater was specifically ill-advised. But it was clear — at least, to me — that what made our work unsafe is precisely what makes it all the more mystifying and awesome: people gathered, breathing the same air. So after a long period of screens and isolation, let my first act as Playwrights Horizons’ new Artistic Director be to say, at long last, Welcome.

Seriously, welcome.

Share this space with me, and with each other.

For these 18 months we also wondered what live theater might look like when it returns. What do we want theater to be? What do we need it to be? What is theater here to do? Each time I wrestled with this question, my thoughts returned to Aleshea Harris’s play, which in her words is “a ritual to celebrate the inherent value of Black people, affirm those navigating anti-blackness and honor those who have lost their lives.” Created with staggering skill and a dagger-sharp pencil, it makes full use of what live theater, our medium of choice, can offer: ceremony, poetry, community, rage, song, laughter, paradox, transformation. I’m honored to re-open Playwrights with Aleshea’s writing, and with this extraordinary cast and creative team, and by the chance to say, again,

Welcome.

Thanks for bringing theater back to New York. A

WHAT TO SEND UP WHEN IT GOES DOWN

Written by Aleshea Harris

Directed by Whitney White

September – October 2021

Photo by Marc J. Franklin.

Ugo Chukwu and Rachel Christopher. Photo by Marc J. Franklin.

A good friend once told me that we each have a different job where challenging racism is concerned. She spoke to the ways she could use her privilege as a white woman to dismantle the white supremacist ideology that contributes to the deaths of so many people.

As a Black woman and writer, I am uniquely positioned to create a piece of theatre focused on making space for Black people. This is one way I can contribute. This is my offering.

I’d like to end this ritual by challenging you to consider what you are uniquely positioned to offer. As a non-Black person, what is a tangible way you can disrupt the idea responsible for all of these lives needlessly taken?

My hope is that you will consider this deeply.

My further hope is that your consideration will turn to action.

Aleshea Harris

Communal Rituals Aleshea Harris

Aleshea Harris’ What to Send Up When it Goes

Down was written in direct response to anti-Black violence, past and present, and honors loved ones lost. What follows are words that Aleshea wrote to encourage us to continue sending up love, strength, resilience and joy as many times.

Also, please feel free to visit www.bagofbeans.net/wtsu-resources.

This page is a virtual extension of What to Send Up...’s purpose, a space where people can honor those lost to anti-Black violence, send love letters of hope and affirmation to Black people and access additional resources related to communal healing and social justice.

What to Send Up on Your Own

The ritual doesn’t have to end just because the performers are gone.

You may find it necessary to carry out your own ritual response when another tragedy occurs.

Here are a few things you/your community can do to send it up, some of which were modeled in the piece:

1. Speak the Names

In What to Send Up..., we speak the name of the deceased once for each year that they lived. You can do the same or find your own way of acknowledging the tragedy of their death while keeping their name alive.

2. Group Yell

Gather in an appropriate place and yell together. Be sure to support each other’s need for catharsis by way of this expulsing. Make sure the space feels and is safe for this kind of expression.

3. Group Call and Response

In a circle, one person can say any number of affirming, lovely things about Black people. Here’s a format:

“You ____________people!” and then the others in the circle and respond with, “Yeah!”

Examples from What to Send Up...:

LEADER: You beautiful people!

ALL: Yeah!

LEADER: You creative people!

ALL: Yeah!

You could build a list of adjectives beforehand and create a script to do call/response with or encourage participants to call out the adjectives as they think of them in a circle.

4. Break bread

Gathering together to eat good food can be a tremendous way of nourishing aching spirits.

5. Love Letters

You and your loved ones or community members can write love letters to Black people and share them however you see fit. Perhaps each person reads theirs aloud. Perhaps they’re passed around randomly, tucked into pockets to be enjoyed when needed.

These are just a very few examples you are welcome to use. I encourage you to think about what’s most useful to your community.

Be creative. Be loving. Be strong together.

Javon Q. Minter

Photo by Marc J. Franklin.

Plays as Shapes

At Playwrights Horizons, we are in awe of the variety of shapes that plays can take. While some works of theater beautifully conform to an Aristotelian structure - rising action that reaches a climax before resolving, like a big arc - others accumulate in different and innovative forms. To get a visual sense of a true range of artistic expression, we asked some of our favorite playwrights to draw the “shape” of one of their plays. Check out the full series throughout this magazine!

Aleshea Harris:

(for What to Send Up When It Goes Down)

1. The piece began before them, in fact. Way, way back. What we see of it gets more and more tightly coiled until…

2. The People must exit the spiral together to medicine themselves by way of turning inward, gathering, honoring, holding each other, speaking the names.

3. The People exit the piece altogether, in a new direction, no longer caught in the shape and structure of the ritual.

SELLING KABUL

Written by Sylvia Khoury

Directed by Tyne Rafaeli

November – December 2021

Marjan Neshat

Photo by Joan Marcus.

In times of war, of military campaigns, of unrest — the amorphous state must suddenly become flesh and blood. The arms, legs, and minds of individuals cease to be their own and instead are pieced together to give the state a bodily form. It requires hands to hold weapons, lungs to breathe gas, and mouths to translate. And in those moments of peril and patriotism, every part unquestioningly belongs to the state.

But the moment the campaign is ended, the need fulfilled, the body disbanded — what then?

Sylvia Khoury

Playwright’s Perspective: Selling Kabul

Marjan Neshat and Dario Ladani Sanchez. Photo by Chelcie Parry.

The War in Us: A Reflection on Selling Kabul

Heather Raffo

I REMEMBER WATCHING Walter Cronkite announce Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. I was a nine-yearold kid in Michigan, doing the evening dishes. It was my first memory of “war,” and it was indelible. I didn’t know it was possible to take another country, like we did on board games. I naively thought the remaking of borders was, simply put, history.

The following year, the Iran–Iraq war started, and my Iraqi cousins were called to serve. Thus began a daily negotiation between my American privilege and my Iraqi precarity. What followed that war, almost without pause, were nearly three decades of conflict between my two nations. Yet, in the U.S., people just went on with life. Very little stopped. The bars were open, the mall was open, and the theater was open.

After a pandemic year of closed gatherings and collective loss, I wonder — will Americans arrive to Sylvia Khoury’s breathtaking play, Selling Kabul, differently? Will they recognize in themselves the harrowing bargains we make for survival? Have we become more intimate with our own history? Because, in this searing play, we meet people we might know: the mothers, the lovers, those working jobs they don’t believe in, those working jobs they do believe in. Each character suffers a loss: of person, of potential, of pride. We know these people, we could be these people. Together they’ve lost their belonging — and, as the play’s title suggests, their nation was sold out for individual survival. Afghans have been living with the cost of war for decades. I’d like to remind Americans: so have we.

The brilliant playwright, doctor, and human, Sylvia Khoury, asks us to intimately reflect on how our value-systems cost this one Afghan family so much, and in doing so, how our value-systems have come to define who we are. As I write, my news feed tells me of a school shooting in Michigan, a supreme court on the verge of overturning Roe vs. Wade, and another coronavirus variant billed as “cause for concern” or “midterm hype” depending on which news you watch. There’s a war here too, and perhaps, like Jawid, we’ve sold off parts of our country for the comfort of our TV.

“A school shooting in Michigan, a supreme court on the verge of overturning Roe vs. Wade, and another coronavirus variant billed as ‘cause for concern’ or ‘midterm hype’ depending on which news you watch. There’s a war here too.

It is possible that Sylvia’s play comes at a time we are poised to grapple with our place in a shared story. Multiple homeless and hungry people passed me on my way to the theater. When I sat in my seat, I looked at the masked audience, knowing someone here, too, lost their husband, their child, their potential, their job. I watched four profound actors on stage. I know these precious actors well, I know the stakes in their lives - how they carried this play for 19 months during the pandemic, how they faced industry-wide unemployment. I know that when they fight for family on stage, they’ve had to leave family behind in other states, or fly grandparents in to look after their young children — all just to tell this story for you. While none of that compares to the reality of their Afghan counterparts, I am reminded of the life investment it takes to even tell a story, to make a difference.

I left Sylvia’s play with an overwhelming feeling that I’ve been fundamentally changed over the last decades of war, in ways I can never fully unpack. I saw in her characters ordinary people, in impossible situations, becoming unrecognizable to themselves. When I look deep enough, the nine-year-old me doing dishes in front of the evening news would admit — there are unrecognizable parts of me now too.

What has the last 20 years cost you?

If, like Afiya and Jawid, you could collect what you’ve saved over the last two decades and invest it in someone else’s life…would you?

Sylvia’s play is a battle cry for us to do just that, to, at all costs, simply invest in each other.

A

Mattico David Photo by Chelcie Parry.

On Silence Deb Margolin

for Agnes Borinsky

All’s Well that Ends Well

The woman is in the bathroom with her two children, Matt and Julia. All three in one smelly bathroom, the pink ‘50s tile, the tattered bath mat, the sink splattered with toothpaste droppings, the toilet exhausted from its sad receipts, the towels drooping like eyelids, oblique and damp. Two kids and a Mother in a bathroom. Enough for a painting.

The girl is six, and she’s beautiful in that drowsy, preconscious way. Her lips are puffy, full of deep pink flesh, her eyes tight in her head as if in taut collusion with her mind and thoughts, her little feet exuberant with the floor.

The boy is eight and a half; his beauty is more obvious and easier to ignore, his hair is too long, his eyelashes are endless and curl up towards his forehead like those of a torch singer in an evening gown. He is very much the poet, out of step with the practical universe, richly attuned to invisible things. His sister torments him much of the time with the practicalities which elude him. She understands how to hurt anybody. She understands that people are hurt by different things.

The little girl has just realized that she’s going to die someday. Just realized this fully, for some reason, some unknowable reason. There’s always just a moment in a young life when this dawns fully on a person, a person for whom death is generally very far away, but it dawns fully, like the a soldier waking for his first day, a gun on his back, in a foreign country where he’s been sent to fight a war. She’s just realized she’s going to die someday, here in this bathroom.

Everything is quiet for a few moments. Then she starts crying. She’s yelling; this isn’t a peaceful sorrow, not even a sorrow of any kind, really. It’s an outrage, an insult. Like being called a dirty Jew. She’s outraged. Her brother picks at a piece of soap stuck on the side of the tub. Mother is peeing.

I am not going to! she says.

Mother’s pee sounds musical, jaunty, as it falls. They talk over this tinkling fountain.

I’m sorry, Julia, you are, her brother says. The piece of soap comes off under his fingernail. He tries to flick it into the sink. His sorrow rises with his eyelashes up over his head.

I’m not! I’m not going to die! And my brother’s not going to die EITHER! she shrieks.

The Mother looks at them. She’s wiping herself, getting ready to stand up and flush. She tries an academic approach:

Everything dies, and when things die, they ready the earth for more life. It’s a cycle, like in The Lion King, the great circle of life, remember?

My brother isn’t going to die! I’m not going to do it! There isn’t any circle! I’m not going to die, why do I have to do that! You can’t make me do that, and I’m not going to!

Mother flushes the toilet.

Okay, Mother says, okay, that’s fine. You don’t have to do it.

What happens when you die, Mom, the boy asks, returning to his soap piece on the edge of the tub. Do you just see darkness, and lie there very still?

No, the Mother says. You don’t see darkness.

What then, he asks.

Well, you just don’t see. It’s another way of being.

The girl has stopped crying and her eyes are ablaze. She’s seen a piece of candy on the floor that she dropped there earlier, when she snuck into the bathroom to eat it secretly. Defiantly, looking her mother directly in the eye, she pops it into her mouth.

Mmmmmmm, she says, This candy is duh-LICIOUS!

She swallows the candy, and then her eyes fill with tears again.

I can’t do it, Mom, I won’t.

Fine, the Mother says, don’t ever do it.

There’s a silence.

Mother opens the bathroom door, and sound from the house flows in like dammed water loosed.

Ma! Ma! The little girl says. Can you talk when you’re dead?

No. You can’t talk! says the brother, sadly.

The Mother turns to the little girl, lifts her.

I don’t know, the Mother says.

But can you talk, can you talk? Is there any talking?

We can’t hear the dead people talking, but that doesn’t mean they don’t talk, the Mother says.

The girl struggles down the Mother’s body, stands on her own. Says:

Well that means there’s talking, and I’ll just talk. If I can be dead and still talk I don’t care that I’m dead. I’ll talk and talk and talk and be dead and talk.

The girl bursts out of the bathroom, relieved. Goes into her bedroom, pulls the head off one of her Barbie dolls. She throws it up in the air. It hits the ceiling, falls down dully, rolls an instant and stops, nose down. The little girl puts the headless Barbie fully upright and says:

I’m dead, and now I’d like to tell you a story! Are you listening, boys and girls? Are you listening? Listen, you stupid, stupid children! You have to listen!

I’ll Be Seeing You

I’ll be seeing you: “… this colloquial formula does not necessarily imply a future meeting.”

—American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms

There were two occasions on which I said goodbye to myself in the mirror.

The first time, I had just taken a shower after learning that I was pregnant with Matt. I came out of the shower, dried my body, stepped out of the bathroom and stood naked before a full-length mirror on the closet door. I saw my shapely body and loved it savagely, tenderly and newly. I wished it bon voyage. I entered into a contract with myself. I had no idea if I would ever see myself in that body again, and I felt an unfettered and joyful fear.

The second time occurred in front of a dressing room mirror in Toronto, Canada. I had just finished performing and come offstage. It is that delirious moment between moments, right after performance; a private moment between public moments; a delicate transition, when one is halfway between a character and a self, like being on a train between towns, having no idea what town is just outside, there are trees and birds, and beautiful as they may be, no train stops near them; they are part of passage, they are like dreams.

I stood in front of the mirror. It was four days before I was due to start a grueling regimen of chemotherapy.

I had been told I would lose most of my hair. I had been told they might have to cut into my neck to put in a system for delivery of these chemicals. I had been told I’d be nauseous, constipated, and pale. I had been told one chemical scars the lungs, the other can damage the heart. I had been told all these things, and I stood in antecedence of them, looking flushed and beautiful, much as I’d looked four weeks into a pregnancy. I stood in joy for a long time. Then, out loud, I said to that beautiful girl:

I’ll be seeing you.

Keep Body and Soul Together

My beloved friend L and I got sick around the same time. Rather, she started it; standing at the Xerox machine with galleys of a book of my work which she’d edited and muscled into publication, she was told on the phone that she had a small breast tumor, operable, with radiation to follow. She continued xeroxing, and called me while doing so to tell me this news.

L was a brilliant scholar of Theater and Gender Theory, a full professor at an Ivy League university, who spoke softly with a southern drawl, and had luminous ideas which, even when seen in the stillness of print, seemed impulsive and passionate, as if they were physically moving through the mind in a terpsichorean parade. We met when, as a theater scholar, she was writing about my feminist theater company; our friendship branched off from this academic context and into something undefinable and very, very deep. L was a melancholic, a philosopher, a sexual sadomasochist, a poet and a Buddhist. She associated ideas and bodies in ways that were at once wildly radical and profoundly humanist. She described herself as “Southern white trash” and made me laugh unmercifully with her stories about her mother, broke and insane, who made her and her brother participate in “luaus” in their broken-down driveway, where they would feign roasting a pig while loud hula music played and her brother was forced to dress up in a white sheet and pretend he was Moses.

Masses were discovered in my nasopharynx and neck, and my long tangle with lymphoma began.

L, a devout Buddhist, wanted me to go to death and dying workshops (Buddhist thought is about rehearsing various kinds of impermanence, I think), but I demurred, telling her I wanted to go to life and living workshops.

I remember her coming with me to a doctor’s appointment during which I was told about several lesions (the word lesion being a horrifying new term for me, and one which still fills me with terror) and L trying to get me to lift my head, to eat a bowl of soup.

All our friends were going through midlife crises, but L and I, fighting for our lives, found this funny. Other women, worried about cellulite, made us grateful our cellulitic legs could even get us up the stairs! During this period our friendship deepened even further. We called ourselves The Cancer Girls. We discussed sex and philosophy; we discussed love and money; we discussed mortality and its relationship to language. As both L and I were in love with language, we discussed alternatives to it, should disease or aphasia rob either of us of our ability to use it in service of our great love for each other. I told her that, should she be unable to speak, she should send me an envelope with confetti in it, and when I opened the envelope and the confetti showered down, I would understand, and would come to her and rescue her from solitude with tools of hyperarticulate silence.

Right before her ambulatory breast surgery, I was allowed to sit with L in the holding room, where she, dressed in a blue hospital gown with paper slippers and a blue hair cover, gave me the information that she told me would obviate absolutely and forever my need to go to graduate school in Performance Studies. She told me all I needed to know was that Jacques Lacan, the famous philosopher of language cum psychologist had said two immutable, critically important things:

1) The signifier is always literal in the unconscious (i.e., whatever you say, you really mean, even if you’re using an idiom or a figure of speech); and secondly, and most critical, most ineffable, most profound, most tragic:

2) To speak is to suffer.

This last, with all its layers of meaning, has informed my entire life and work.

It turned out that my beloved had a rare and deadly new form of breast cancer, which literally spreads the way fire does, grabbing and converting everything it touches into part of itself. The effortless metastasis of this disease reminded me of the celerity and beauty of L’s mind and intellect. She began coughing uncontrollably as the disease melted through her chest wall and into her lungs. She cried a lot, and during that period, everything I did annoyed her. I would leave her apartment, sad but undaunted, and try another approach the next day.

She shaved her head. Her baldness clarified both her beauty and her suffering. It was Springtime then, and L told me she couldn’t go out into the lovely afternoon sunlight, because it made her so sad and angry to be enchanted by a beauty she was soon to be torn from.

Once as we were going to her doctor in those late days, we were walking down the street and L was hurrying and hurrying and gasping for breath. I said to her:

Sweet one, slow down. We are in no rush. Walk more slowly, dear, please!

And I looked at her, her body, her materiality, how frail and skinny yet tangible and visible she was; when she responded verbally, I suddenly saw clearly that her speech and her body were not of the same mettle; that her voice and ideas came from a place that was different from her material body; that her speech was a cartography of her immortal soul, and her body something of a one night stand God had with the world; she was beautiful; I saw that she was dying, and I saw how ridiculous, how incomprehensible, that was. In that instant.

Friends gathered at the hospital; she’d been admitted, and the doctors finally had a terminal patient on whom they were free to try everything. Many of us gathered in the room at once, and L, high from painkillers, grinned from ear to ear and told us how beautiful we all were.

When I got her alone, I asked her to hold on for a month. I told her I had an important play opening that I needed her to see. I think I deluded myself into thinking that she could be distracted from dying, the way I’d distracted my children from things they wanted in the supermarket, things they had fixated on and might have a tantrum over. She said, in her velvet Southern drawl:

Honey, I don’t think I’m gonna make it; honey, bring me the script, I don’t think I’m gonna make it that long.

The next day, when I came with the script, she told me she couldn’t see. She told me she’d dreamt there were seven things on the floor, and she was to pick them up, and when the last thing was picked up, she would die. I joked: Oh well! Just leave them! Don’t bother cleaning up, just leave everything as it is! No cleaning up in here!

The next day, when I went in to her, she asked me again about language. She said:

Honey, if I can’t speak, will you still be with me? Will you still understand me?

And I said, Yes, yes, yes, of course, let it go! You can let speech go! Anytime, you can stop when you’re ready, and I’m still with you, I’m right here.

I brought Matt and Julia to see her. They both loved her very much, sensing since they were babies both the power of her gentleness and the hilarity of her rage. Her process of dying had so many things in common with their processes of learning to live. L had always made them laugh, even when she said very little. They both kissed her face many times. We had a flat tire going home.

On the very last day I heard her speak, she returned her voice to that of the teacher. She told me:

Honey, I have just eaten oatmeal. I loved my oatmeal. It tasted so good. They served it just the way I asked. It had in it brown sugar, and butter, and every bite was Heaven to me. Here I am, honey, here, so small on time, and I loved, loved, my oatmeal. You can do that. You can do that too.

The next time I saw her, she did not speak anymore, but lay still, breathing heavily and sporadically. Her partner brought her home.

On New Year’s Day, I was called by phone and told that she had passed away at the stroke of midnight as the year 2000, after anguish in labor, gave birth to 2001.

When I got to her apartment, there were 10 people outside the door. They told me: Go in and see her. She looks so peaceful.

I entered the apartment and approached the bed, and my beautiful friend was laid out there, bereft of her soul, just her body, and her face, which was contorted into a mask of homicidal rage. I have no idea what those people saw when they looked at her.

I told the children that L had died, as gently as I could, as neutrally and tenderly as I could. Matt cried for a little while, and then moved on, but Julia started laughing, and she lifted one of her dolls and began to fly it around her room.

It’s wonderful, she said. Before, she was just in one place, one single only place, and I had to go far away to see her, but now She’s Just Everywhere!

Silence

I imagine the silence around a just fertilized human ovum. The most obnoxious sperm, the one that swam the fastest and spared no other any mercy, brutalizes his way into the egg, and the egg lets out a little cry; then the doors of the egg slam shut. A boundary forms around this astonishing new consortium of sperm and egg; they know themselves to be up to the most atavistic and sacred devilment. This barrier forms the way an invisible bulwark forms around two people who fell in love while you were watching; you saw it happen. And this barrier – called the zona pellucida – is designed to keep out all other sperm; to keep out any other genetic information; to keep out the sounds such things make, the other percussions of the body; and there’s a holy silence, I just know it; a silence worthy of what it precedes: the perilous trip down Fallopia, the arrival at the pelvic pear, blood-lined and sweating; the violent implantation; the waiting. I know that silence.

The silence of a book. So noisy! Images, people, carriages and cars; sex, murder, text messages and letters; secrets and crimes; loucheness and lyricism! I can hear that silence looking at a book sitting quietly on a table. I have to cover my ears! The din!

The silence of an onion. It’s hard to believe an onion doesn’t cost thousands of dollars: so complete, its brittle skin falling off like a woman’s nightgown, the moist, translucent layers beneath, its pungence, its obliterating sweetness. I do not feel I should be able to afford an onion.

The silence of the drug addict who stole my purse while I was performing onstage. I didn’t know she had stolen my purse; I didn’t know that everything I had brought with me was gone, but I did know. Her silence told me that. In the bathroom, three scenes until my next appearance onstage. Playing a miserable character whom none of the other characters liked. Had to pee desperately: woman in there, young woman, staring at me, silent; a nasty, incalescent panic in her eyes. I knew she had robbed me before I knew I’d been robbed. Everyone hated my character in that play, and thus though they loved me, they hated me also. People fled when they heard I’d been robbed, as if I could infest them with bad fortune. I was glad; something about being robbed while working for nothing seemed humiliating. I smiled when I was finally alone in the theater, with no one near me, no keys, no money, no way to get home, nothing.

Walked out into the rain, so far west in midtown Manhattan that it’s not even Manhattan anymore, it’s an anonymous dark alley near a river, where rats take freedoms they have nowhere else and you could be anywhere, it’s dark there even when it’s light. And there, on the scalloped metalwork around what was trying to be a tree, was a $20 bill, draped like a Dali clock, wet with rain, filthy. I picked it up and took a taxi home. I was laughing because that silent woman in the bathroom with the hot, deliquescent eyes: I know her.

Most sublime is the silent body onstage. This silence is like no other. The still, silent body in the light is an outrage, a radical act, a protest, a come-on, a flirtation, a denial, a consummation. When the lights come up and I’m standing onstage, before you, humbled and emboldened by your presence, I am elevated to an apotropaic level: nothing can hurt me, nothing can hurt you, the zona pellucida is around us, we are beginning! I am unstoppable, I belong to you completely. I’m in love with you. I’m being physical with you, I’m letting you hold me, you’re having your way with me, I could die at any moment, we are laughing together, you and I; we are ageless, and I am standing there in silence.

Are You With Me?

Mel Ng

“Rituals are the doorways of the psyche, between the sacred and the profane, between purity and dirt, beauty and ugliness, and an opening out of the ordinary into the extraordinary.”

– Jay Griffiths

I go to the theater to experience the sublime, to have catharsis, to be in community, to learn, to participate, to work things out … these are images I came up with to chase down those feelings.

are you with me?

Sarah Ruhl:

This sketch is the structure of my play Late: a cowboy song. It’s the structure of Mary trying to leave a toxic relationship; it describes a parabola that keeps closing in on her as she repeatedly attempts to leave, but comes back. She leaves and comes back, leaves and comes back with a circle tightening around her, until she finally leaps out into the unknown at the end.

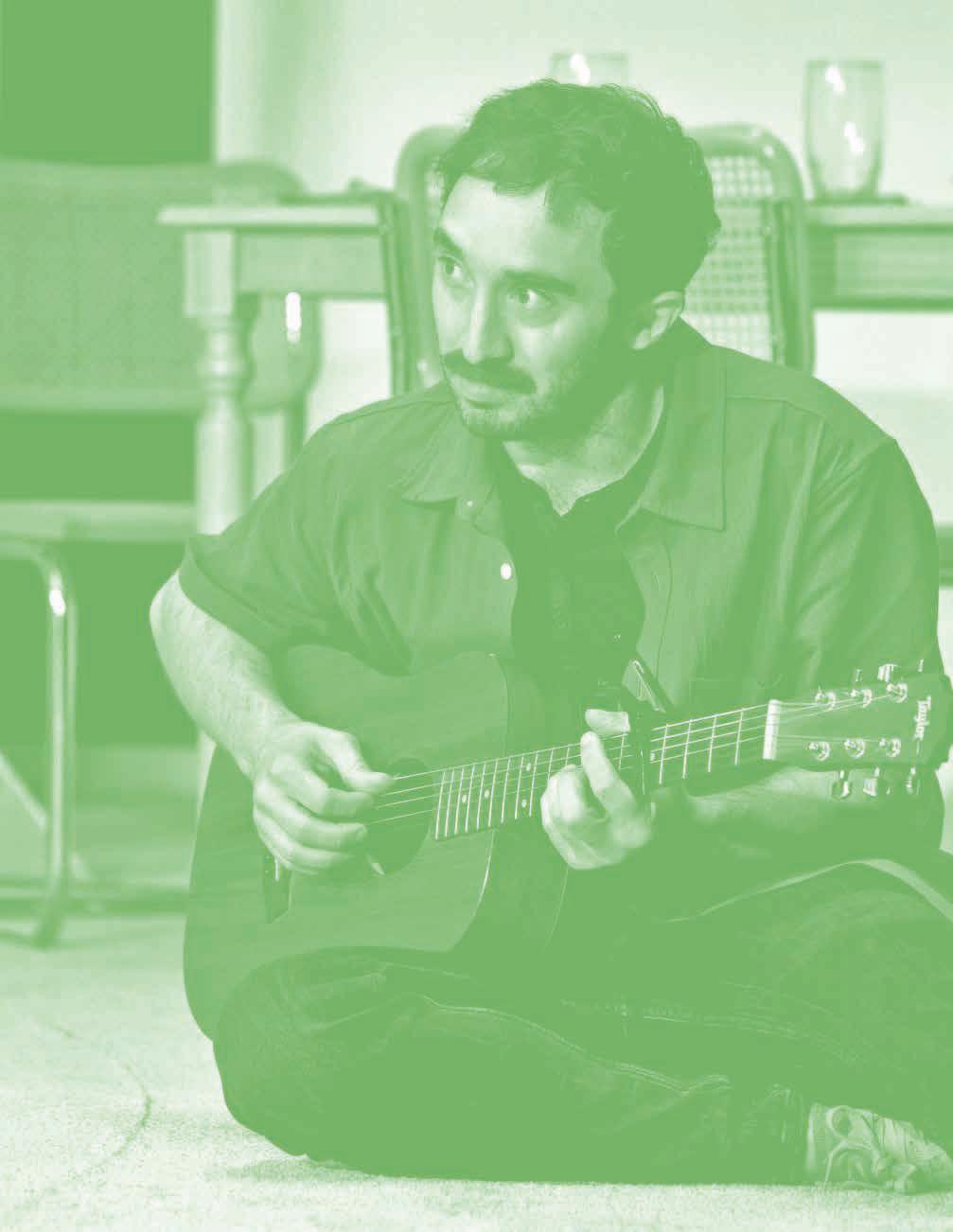

TAMBO & BONES

Written by Dave Harris

Directed by Taylor Reynolds

January – February 2022

Tyler Fauntleroy and W. Tré Davis. Photo by Marc J. Franklin

Tyler Fauntleroy and W. Tré Davis. Photo by Marc J. Franklin

“

The most fun part about writing is that every writer I know is a fucking liar. Some think this is radical political work. Some think writing is to channel the ancestors and the woowoos to put voice to page. But all of this is just tactic. This was the realization that made me stop doing poetry slams and start to focus on theater. I wasn’t growing as an artist; I was growing as someone who could perform identity. Spoken word capitalizes on an idea of the authentic identity. The real person. But here, in this theater, all of us know that every second of this experience is fake. And there is infinite possibility in that reality. And the pleasure is in the possibility.

Dave Harris Playwright’s Perspective: Tambo & Bones

When the Sleepers Awaken Anne

Washburn

WEREWOLF IS A GAME (you may also know it, if you know it, as Mafia) best played in a roomful of people who don’t know each other well, and are experiencing a social impulse, and it’s after dinner, and dark, and maybe there’s drinks or whatever. It’s endemic to writers’ colonies.

You sit in a circle by the fire, or around a table, and the game is led by The Narrator, who starts by passing out cards at random to establish the identity of every player. You cup the card in your palm to glance at it, and you are Townsfolk or The Doctor or The Seer or… The Werewolf.

There is, The Narrator informs everyone, a Monster loose in this small community; it selects its victims at night. Night has fallen. Everyone droops their heads, closes their eyes.

“And now,” says The Narrator, “Let The Werewolf awaken” (or, you know, to that effect) and in the circle of ‘sleepers’ — and remember that it’s night, and ideally the lights are low — one person opens their eyes — and there is a curious intimacy in that moment, between the Narrator and The Werewolf, two sets of live eyes in a circle of closed faces; a secret, and a threat — and The Werewolf silently, subtly, indicates a victim.

“It is done,” The Narrator might say, or “got it” or, perhaps more menacingly: nothing.

The Werewolf closes their eyes, and sinks back into the small sea of sleeping Townsfolk.

I like to think the impulse behind theater is that it strokes the set of nerve endings we acquired in our origins as humans sitting around campfires in the dark studying each other carefully: who here is dangerous, who here is sexy, who is capable, who is lying, what will happen next. We have a lot of instincts around watchfulness, around grappling with unpredictability, and it’s pleasurable to thrum them in safety.

There is also a Doctor who is awakened and, looking around the circle of suspended players, can make a guess and select one person to ‘cure’ — it can be themselves; there is a Seer who is awakened next and points to one person about whom they have a question; The Narrator gives them a thumbs up, or a thumbs down — and The Seer closes their eyes again, knowing more than they did before.

And then the sun rises, The Narrator announces, and (unless The Doctor has guessed correctly, in the dark reaches of the lonely night, and has healed the intended victim) there has been a death in this small hamlet. The name of the victim is announced (that person, maybe relieved, maybe disappointed, possibly slightly stung — because it’s never quite pleasant to be killed, even in proxy—pushes their chair back a bit, grabs their drink, and prepares to watch the rest of it all play out) and now — and this is the heart of the game — the townsfolk have to deal

A play doesn’t have to push any sort of boundary to be very great and very satisfying, but surprise is a fundamental pleasure because on some deep level we’re always tensed for it.

W. Tré Davis. Photo by Marc J. Franklin.

with a secret werewolf: accusations are leveled, sometimes at near random; the accused hotly defend themselves and generally turn to accuse another; expressions are closely scrutinized, protestations of innocence evaluated. In the end the town casts a vote on who must die.

It’s a simple and complex game in which people who don’t know each other well try to game each other out: some people are good at performing innocence, some innocents are bad at performing innocence, some people are good at guessing but bad at persuading everyone else and the reverse, some people are taking the game seriously and others are looking to mix it up.

Generally the werewolf survives to kill, and to kill again. It’s like a play, in which the audience isn’t safe.

One thing I learned, when I was a member of the 2018 Working Farm cohort at SPACE on Ryder Farm (a beautiful and only slightly haunted artist and activism residency on an old farmstead in Putnam, NY) for various weeks over the course of the summer, is that you don’t want to be on the wrong side of Dave Harris in a game of Werewolf because he knows. Be you ever so cunning, he knows if you’re The Werewolf, he knows if you’re The Seer; he’s one jump ahead of everyone else. It isn’t just that he can tell when you’re lying, it’s that knowledge of what the hell is going on seems to flicker to life within him — be it psychical powers, preternaturalism, or a heightened degree of watchfulness/observation I don’t know; just don’t try to game out Dave Harris.

“Writing has a cost — and people will love you for paying it…So in this search for newness, in all this language and fear, what’s the cost that I’m paying in the work of each of my plays? And how will I contend with the reward?” Dave Harris says in an interview…

[This is an amazing question. I teach playwriting sometimes and when I teach will at some point ask the writers if they have Questions and this is a question I am always waiting for, which no one ever asks -- not, necessarily, because they aren’t wondering; they probably don’t think I have the Answer, I don’t have the Answer, I don’t know the costs I only know they’re there, always, matter doesn’t coalesce from nothing, and, rewards can be deadly. What, Dave Harris asks, are the particular costs paid by American Black writers speaking to a white audience; is there an American white appetite for American Black pain and when it comes to that question and that cost I’m just a consumer, wondering about that thirst and what is it, exactly, a dark rich mix of impulses, some of them very old and very deep, not all of them unwholesome; I can’t know the costs of supplying that nourishment, feeding that particular thirst; I can wonder about that hunger, and the consequences of that hunger, can wonder about what it means to give quarters for what satisfaction…]

We forget that theater is a form of near-infinite possibility and that we are living in a small corner of it. By “it” I mean the culture of theater as we understand it currently in, let’s say, the United States, and I include in this both the most familiar comfortable plays and the most insane experiments, but it’s worth remembering: just as Science is, properly speaking, not so much a set of conclusions (although it includes some pretty durable conclusions) as it is a mode of inquiry and rigorous curiosity, Theater is not the art of making a play, Theater (as a Western art, at least) is the form we use to grapple with the fact that we’re an inevitably social species which is positively larded

with anti-social impulses, and there are a million ways to approach this. A play doesn’t have to push any sort of boundary to be very great and very satisfying, but surprise is a fundamental pleasure because on some deep level we’re always tensed for it.

I saw the first 10/15 minutes of Tambo & Bones at Ryder Farm, at the end of the season presentation of work from the summer. I liked it fine. I thought: oh, I know what this is.

Playwrights sent me a copy of this play and I began reading it, thought: yes I know what this is. And then realized I didn’t quite. And then that I really didn’t; I don’t remember the happy moment at which I realized I couldn’t figure out what would happen next or how; I couldn’t game out this play. This is in part because it’s a play in which pretty much anything could happen, because Dave Harris is taking us on a cruise through not exactly all but most of the possibilities, the thoughts and counter-thoughts, the feelings and counter-feelings, none of which cancels the other out but which accrue remorselessly. A play which is furious, cool, humane, diabolical, truthful, calculating, funny, stirring, featherlight, ultra dark, heavy, bright. A play which lands…beautifully…and what a pleasure it is when plays land beautifully…but which lands in such a way that you suspect if you stuck around after the end, when the audience has filed out, and the aisles are swept, the big red curtain will woosh back open and it will all take off again, going to the million other places it is capable of visiting.

Dave Harris is The Seer – the one who sees, sometimes all, and sometimes just more – he’s The Doctor – sometimes healing or trying to heal, sometimes rationing that power to protect himself – he’s The Werewolf: a killer –or maybe just hungry; he’s a Townsfolk, trying to figure out what is going on, trying to figure out what is the best way forward, trying to convince those around him of the truth both subtle and obvious through rational argument, through emotion, persuasion; he’s making and fielding false accusations, sometimes just mixing it up, one of an angry confused mob. And all along, of course, he’s The Narrator, pacing the perimeter of the circle, the one who sets it all into motion but cannot control the outcome, cannot intervene, cannot save anyone, powerful and powerless at the same time.

And he’s in the audience with us, both figuratively and actually, included and therefore unsafe.

[and here it might be worth flagging the very obvious; my gaze, multiplicitous in many ways, is also a very white one]

What have we bought for our quarters? 90 minutes inside the head of Dave Harris.

If you spend 90 minutes inside of Dave Harris’s incandescent head, will that give you the power to detect Werewolves or, if you are a Werewolf to thwart Townsfolk and Seers? Will it give you, earnest Townsperson that you are, the power to bring the people to your side? No.

Your personal powers have not increased but you’ve just spent some time with real Science, with a mindset which knows we have to offset our desire to see the world through the lens of what we understand and expect and hope and fear — the assumptions we’re most comfortable with — if we want to figure out what’s really going on.

Also: this isn’t Science, which is to say: it isn’t sentimental — doesn’t by temperament expect a rational outcome is possible — this is Theater and Theater, at its core, knows there’s no way to figure out what’s really going on; you can’t game out life. A

Dave Harris.

Photo by Zack DeZon.

The American Voice: Dave Harris Natasha Sinha

ANTICIPATION for Dave Harris’ major New York City playwriting debut has long been building amongst those of us who read hundreds of new plays annually — and now, at long last, here in December 2021, the exhilarating world premiere of Tambo & Bones is upon us. It’s staggering to realize that we are only at the beginning of Dave’s theatrical life at this scale. The beginning of his virtuosic plays bursting with sharp insight and laugh-out-loud humor. The beginning of his wild romps through satire and surprise. The beginning of storytelling built with a piercing awareness of not only who is watching, but what the exchange during performance does to both artists and audiences. Like Adrienne Kennedy, Dave has a creative restlessness that fuels his formally inventive plays. Like Anne Washburn, he interrogates history, rebuilding, and storytelling itself. Like Young Jean Lee, he follows what scares him. And Dave’s unique voice rings out clear and confident as it calculates the exact angle at which to approach Blackness, performance, violence, white nonsense, capitalism, the lens of storytelling, and so much more. And he delivers all of this with vibrant energy and an existential wit!

Dave’s oeuvre makes clear that he is truly an artistprovocateur above all. Mesmerized by craft and the ability to manipulate, he wields skills borne of both instinct and practice, in order to push the envelope and subvert expectations. Spend time with the honest ruminations on masculinity in Patricide, as he examines how we observe the world around us when we are reading poetry alone. Look out for his upcoming film and TV projects, intentionally created for the screen. Experience the immediacy of his spoken word performance, where he mischievously plays with the assumption of an authentic self. Check out his Literary Ancestry Essay Series about the Black theater canon, via Roundabout Theatre Company. Read his Playwright’s Perspective! (Please, please do!) Go back and watch his hilarious Inanimate Object Battle League series with Issa Rae’s media company, which organically sprouted early in the pandemic.

Whatever the medium of expression, Dave distinctly anticipates what the audience is expecting, and formally turns the piece on its head — not for shock value, but to advance the storytelling. He effortlessly creates striking prompts across art forms. So we are lucky that his OffBroadway debut is happening alongside Off-Broadway’s “post”-pandemic return to theater and efforts toward deeper thoughtfulness... Dave is a visionary and there are no passive choices in his work. If his story appears as a play, there’s an electric yet carefully considered reason for being placed in a theater. It insists on specifically existing as theater.

The pandemic triggered a long-overdue reckoning about race, while theaters largely remained closed, so we’ve been unable to work through those conversations via what we primarily do (ie: produce plays). This fall, shielded by vaccines and masks, productions are beginning amidst this charged cultural zeitgeist. Conversations about representation and authenticity often slide into an assumption that we need a sacred and unassailable truth — as if that would effectively squash injustice. After a year and a half of relentless instability and accumulating anxiety, grasping for certainty has become fashionable in many circles. But what is fully truthful? Can we trust it? Truth from what perspective? Truth for whom? Is that what we need right now? The concept of objective truth can understandably prove comforting in a time of fear. But is it an illusion? With simple theatrical gesture, Tambo & Bones scrutinizes the idea of truth as objective (versus subjective), starting in the first few minutes of the play — what makes a chair a chair? what makes a tree a tree? — and it ultimately leads us to loaded questions about personhood itself.

Instead of pouring cement onto any single final answer, Dave’s work unleashes a prismatic range of realities that gives our imaginations a full workout. Instead of continuing broad yet admittedly noble arguments, Dave prompts our imaginations to go to unpredictable and savage and beautiful and dangerous places. (Imagination is an escape, but also…can we escape what we imagine?) Instead of positing the existence of clean and irreproachable truth, Dave offers surprise.

Surprise lives in the gut of all of Dave’s plays. White History introduces someone from the KKK at a dinner party, while tonally trafficking in the realm of comedy. Exception to the Rule (which will premiere with Roundabout Theater Company this spring) is in conversation with No Exit and Waiting for Godot, as it shapeshifts into exploring abject results of education for Black teenagers just trying to survive. Incendiary begins with a sort of video game dramaturgy, to navigate us through the journey of a Black single mother planning to break her son out of prison. Everybody Black is a project of defining the Black American experience à la The Colored Museum…or is it? Surprise shakes us loose, and feeds our own inquiry about the structures and realities of our day-to-day lives. Are these conversations about race indeed an escalation? Or is time the only thing that is actually changing — amidst a cycle of endless iterations, without material change? (For more on this, stay tuned for Dave’s upcoming Soundstage audio play, exploring discussions about Black freedom. Is there a growing edge in the discussion of Black freedom in this country? What are we hoping to break the cycle toward?)

Working from his own personal curiosity (and against the concept of a monolithic Black perspective), Dave

Or is time the only thing that is actually changing — amidst a cycle of endless iterations, without material change? “

Are these conversations about race indeed an escalation?

chases his own desire for understanding, consciously leaning into what feels surprising along the way. It is an individual pursuit honed by his unique perspective, then fully realized with lively collaborators, and forever marinating in the questions raised. Who needs to be in power in order to bring about meaningful change in our country? Is the very existence of traditional power keeping us from change? What world order would be most just? Is discourse around race and class finally accumulating? Is it stuck in a never-ending loop? What is fake? What is real? What is useful? What do we get swept up into? How should we behave? What would bring sustained selfactualization, tangible freedom, and peace to Black folks in the U.S.? Eschewing oversimplification, Tambo & Bones mines the complexities of these questions in relation to perspective. Dave’s plays are built on the understanding that storytelling doesn’t exist without charged lenses: the perspective of the writer fabricating the story, and the perspectives of the audience.

This play wrestles with two men’s approaches to addressing the source of their troubles, while exploring the creation of a self that is fabricated based on who is watching — for example, selling Black “trauma porn” to elicit interest from (what is perpetually) a predominantly white audience; or, being the buffoonish entertainment for a white audience via minstrelsy (in which U.S. theater has its roots). We watch their success within the frame of capitalism, until we are made to question the very definition of success. We experience the “successful” performance of Black pain in exchange for money, for applause, for laughs, for empathy. We observe empathy operating as a commodified product of performance and as a means toward profit. And then, the fact that the play is an act of sheer manipulation by the playwright is brilliant! It’s karma! It’s Machiavellian! It’s delicious in its desire, its wickedness, its dreaminess, its relatability. Dave chooses to insert himself in this artifice, to perpetuate and popularize these depictions to land his point.

As Tambo & Bones leads us through a surprising, playful, and unapologetic odyssey, we constantly question ourselves. We are gifted an opportunity to practice curiosity about ourselves, our world, our desires, our reactions, our assumptions, our choices. We may not have all the answers at the end, but we can own the consequences of our own choices: do we decide to imagine another space or do we decide to participate in this one? It’s a story built on the necessity of a present physical audience, on the tropes of storytelling within minstrelsy and music and beyond. Dave imbues every choice with intention and virtuosity — including the fact that this play is incomplete without your presence and individual imagination. A

Anaïs Duplan

For Dave Harris

Freedoms by Giving Concerts

We were encamped on a bank high, high enough to where we saw the full thickness of the ground, sewn-up, cleared out

of its large canes. Our escape we planned to some lampooning darkness. Our buffoonery, mysticism, happiness, and luck: the pleasures of the grotesque, of abandonment. A kind of romance exaggerated into Black life, a cheerful, enslaved readiness, a dance pleasing to master-minstrels, a romance carrying on between mothers and a son thought dead in Alabama.

We all earned our freedoms by giving concerts, by acting spontaneously, naturally, all seized up by our willingness to be as darky as he be at home,

as darky as he be in life, in the cornfield and the canebrake’s rivers and floodplains, its valleys lapping along the wet edges

of the waters that early settlers crossed over into indigenous attack, on boats built like floating fires, with heavily-barred windows,

small sliding shutters, walls pierced through with gloryholes. There were guns fired and performers stained in character up off the stage, dressed up in slaveness, that perpetual smiling of Jim Crows and Gumbo Chaffs, fighting, boasting

characteristically animal, bleeding like wolves, having drunk ourselves full of ink to where we got sickened and had to restore the color. We were inherently musical for frolicking through night without no need for sleeping,

ignorant of pain, poorly spoken for, having been shot up like balloons, waiting on the world below to turn.

The musics we hear jangle our nerves. Musics of those believed Black. Propererous musics, respected, polished-up romantic tunes

with recognizable attitudes. Our vigorous teeth-slapping footworks. I’m reeling from these songs.

First called plantation men, then Ethiopian serenaders. Ineffable Blackness gives way to jealousy, as one who is himself

living religion, is the beauty of his own person, is darkly himself, googly-eyed with pink red white teeths.

Goodness gracious, the gentlemen: the brothers named Tambo and Bones, in each other’s joking arms

floating on a skiff in old Virginny, working from day-to-day, raking oyster beds. To them, it’s just playfulness, but now

they grown old, can’t work no more. Carry them back to shore? They’d choose another life this time.

They’d save their coin this time, buy a farm somewhere. But now it hits them tight in their limbs, grown sore. Carry them back

after they jumps from their skiff, down into the river, catching in their mouths as many catfish as ever a nigger has seen. A circus of catfish. Acrobatic fish, bareback lovers in dripping garb.

Plays as

Mia Chung

Abe Koogler

Mara Nelson-Greenberg

1) Open your phone, find his name

Reminder that the last time you called him you changed his name in your phone afterwards so it will now appear as First Name: If you // Last Name: Call this number you are entering a world of pain (so under C)

Another reminder as you even just LOOK at his name and imagine dialing:

You are calling him to leave a message about jury duty. YOU ARE NOT CALLING TO TALK TO HIM ON THE PHONE.

You have called him 98 times and he has never answered before. You are in control of what can and cannot disappoint you based on YOUR EXPECTATIONS.

Side-note about number of calls: Feels somehow okay to call 99 times. 100 not okay. This is your last chance to leave a GOOD, STRONG VOICEMAIL.

DEFINITION OF GOOD, STRONG VOICEMAIL

List generated with your next door neighbor’s eight year old daughter Rosie when you were babysitting for her this weekend (so list half yours/half hers):

A voicemail that makes it clear a notice for jury duty has come for him in the mail

A voicemail that does not deteriorate into a long monologue about how you are lonely, how you are sorry, how you are still not sure why you do the things you do but you’re finally ready to figure it out and you just wish that he would be willing to go on that journey with you

A voicemail that makes it clear you are OVER things like arts and crafts for KIDS and you LOVE COMPUTERS

A voicemail that embraces the fact that you are independent from him, his opinion does not matter, you are not leaving this voicemail in the hopes he will give you anything in return

A voicemail that shows you do NOT need your parents but especially your MOM to tell you when certain things in a movie might be about to be scary, because you know it’s just a movie and you DON’T GET NIGHTMARES from things that aren’t real now that you’re 8

Remember what else Rosie said:

ROSIE: The best part of being alive is that you can just smile and play and have fun with your friends

YOU: But what if you have no friends

ROSIE: No one has no friends

YOU: I have no friends

ROSIE: Maybe you have one?

YOU: I recently called Justine, who was the only person left in my life who I considered a friend, and she told me that the last time we spoke she was just trying to be there for me and I called her a hag and a shrew

ROSIE: So say sorry

YOU: I did but now she has other friends who have never done anything like that to her before

ROSIE: Then you can still smile and play and have fun alone, like, you CAN do that even if you don’t want to. You actually only can’t do that if you are dead like my rabbit

YOU: That’s nice, thanks

ROSIE: And my dog

YOU: Right

ROSIE: And the boy who lives under my bed

YOU: Can we talk about something else now

2) Dial his number (touch “If you Call this” etc on phone)

It will be a thrill to touch it, it will be dizzying, like an orgasm or like when you got three answers right in a row as you were watching Jeopardy with his parents and you felt like they finally saw you as a smart person and maybe he did too

Don’t bask in the thrill, don’t dwell in it, it’s going to go away soon and this phone call will let you down (similar to when the next question on Jeopardy was “The bride and groom do this together, often with a decorated silver knife” and you shouted at the screen, very loud and proud, “What is ritualized murder, Alex?”)

You will make the mistake of dwelling in the orgasm feeling because you always do

When you return to reality after the orgasm, it is going to feel bad. Know that and expect it. It will feel like reality hitting you in the face

Around now, something unnameable lodges itself in the very back of your throat

3) Wait for the first ring

What to expect when you hear it (based on previous experiences):

Every time: your stomach drops and your body freezes up

Sometimes: you think about how badly you need a hug

One time (unfortunately): you crapped

4) Let the phone ring five more times

Priority now is to relax

That means you must BREATHE

Reminder: Breathe does NOT mean hold your breath until you pass out and when the ambulance comes say, “Just throw me out of the back of this thing, I’m done with life”— reminder that they do not think that kind of thing is funny

Some things you should think about while you are breathing:

— You are doing well, in that you are eating and you are functioning and you are alive

You are TALENTED at something (just need to find what it is)

That kid at the grocery store was laughing at someone else

Some things you should NOT think about while you are breathing:

Maybe this time he will answer

Maybe he will want to get back together with you

Your cousin looked hot in his most recent Instagram post

(Note on last point about cousin: always good to take a beat and remember that you need to STOP thinking about that, and stop trying to figure out if he is single, think rationally, he is your cousin, you are related, he is thirty-five years older than you because of big age gap between your parents (not the most damning part but still good to keep in mind), and he is a criminal as in he once killed a man and when he was done confessing to it he said “that was fun, I want to try that again sometime down the line, but next time with a woman or a relative or both”)

Now you are thinking about family

5) Disassociate

That unnameable feeling that formed in the very back of your throat is now probably working its way down to your chest

You can try to pretend it’s something casual, but once it gets down to chest area it feels ugly and even worse, it feels familiar, and it’s not casual at all

A question will rip through your brain, which is: How can people just go away?

You picture ex-husband And now uh oh it’s happening You picture your dad

You will start to panic. But! There is a solution (remember what Rosie said: “There is always a solution even if it means you have to kill the troll with your best sword” (she was talking about the game on her phone but still useful))

Solution is: Look away! Not everything needs to be examined all the time!

Instead, zoom out. Float above yourself. Remember that you are bigger than this moment, this phone call, this person you are calling. Go really big with it. As in…..

Remember that you only have one life to live. For a moment you will feel angry about that but that is not the exercise. The exercise is to be grateful for everything that is yours:

Be grateful for your apartment

Be grateful for your car

Even though it pays terribly and the hours are bad and your boss is a creep and your co-workers are unfriendly and you are actually not very excited about what it means that you’re selling growth supplements to little children (5 or below) for a living, be grateful for your job

6) Listen to his outgoing message

What to expect:

His voice will make you miss him

The way he clears his throat at the end will also make you miss him

The beep comes really fast (last time it came, you screamed)

The outgoing message will say: Hi, you’ve reached Jackson, leave a message. [Then a computer will tell you how to do that]

This is it

Breathe in, breathe out

The unnameable feeling has now settled in the pit of your stomach. Why can’t you stop thinking about death ever since he left?

Try to avoid doing that. Instead, think about:

— Rosie saying she trusts you even though you were mean to Justine

Your dad’s enormous laugh and how it sounded like a sneeze

Your dad tucking you into bed at night when you were little and saying to no one, “Hello sergeant, signing in for duty to keep my daughter safe tonight” and then doing a salute

The fact that just because people aren’t here anymore doesn’t mean the amount they loved you doesn’t count — you are still loved the amount they loved you

The fact that in the past, people have been notokay, and then time has passed, and they have become okay. It happens all the time. It happens all the time. It can happen to you.

7) Leave the message

SCRIPT: Hi. You got a notice for jury duty, so I’ll forward it to your new address. Hope you’re doing well. Bye. A

The Great Sondheim Pop Quiz Crossword Puzzle

Adam Greenfield

When I was twelve, I saw Into the Woods on Broadway at the Martin Beck Theater, and it blew my mind. That night, unbelievably, I found Stephen Sondheim’s address in the White Pages and wrote him a fan letter on hotel stationery. More unbelievably, he wrote me back two weeks later. I would share photo images of our sporadic correspondence, which transpired over the next six years, but (tragically) these letters disappeared when the family moved out of my childhood home in Southern California.

I remember, though, Sondheim writing, “Your friends must think you’re crazy;” and my thinking, “Stephen Sondheim is the only one who gets me.” And I remember him telling me the key to becoming a theater artist is to just keep making theater, stubbornly, without giving up. I remember him politely declining my invitation to speak at my high school graduation because “I am due to attend the opening of Sweeney Todd on the West End.” And I remember that once, when I came across a stack of Stephen Sondheim’s Collected New York Times Crossword Puzzles at a local used bookshop, he asked me to buy them all and send them to him, which I did. …Except, I kept one for myself. Every once in a while I’d try to complete one, and fail, and in time I became a crossword fanatic.

As I became ensconced as a grown-up at Playwrights Horizons, I was chronically too shy to see if he remembered me. It would have been too devastating if he didn’t. I wish I could have thanked him for the plays that shaped my upbringing, and for giving me that first scrap of encouragement that I could have a life making work myself. But here, I wrote a crossword instead. He would not like this crossword, I imagine, but I hope he would read it as my way of saying, Thanks, Mr. Sondheim.

The Great Sondheim Pop Quiz

1. Thick slice of a thing

5. Three letters on the4 button

8. Good (slang)

11. The final, final, final word

15. Popular spot for a run?

16. Color of the grass, part one. (“Sunday in the Park With George”)

18. Attention-grabbers