27 minute read

President

P

PRESIDENT

Mark Carroll

Abandon the model, not the APY Lands

The proposed SAPOL APY Lands model is a lose-lose for police and the remote indigenous communities with which they have worked hard to build significant relationships.

The model relies on State Tactical Response Group members flying in and out to police communities on the lands.

It is a proposal which not only disadvantages the indigenous communities on the lands but will also become an industrial issue for Police Association members.

It situates these Adelaide-based members away from their homes and families for around 60 per cent of their total shifts.

By occupying permanent positions on the lands, police have always been able to gain critical knowledge of local communities, such as their family structures and the welfare issues indigenous people face in the area.

It is a system which has worked for many years and is critical for gaining trust with the local community members.

It is folly to underestimate the relationships police form with local communities. They provide the necessary trust for victims of crime to come forward and make reports.

The proposed FIFO model simply facilitates the abandonment of longestablished customs of community policing.

In fact, the Australian Law Reform Commission Inquiry into Indigenous Incarceration Rates highlighted that:

“… poor relations influence how often Aboriginal and Torres Straight Island people interact with police… poor police relations can contribute to disproportionate arrest, police custody and incarceration rates. ”

The association is firm in its position that SAPOL should: • Maintain permanent officers on the

APY Lands. • Undertake meaningful discussions with the association regarding any difficulties with the current model. • Actively work to fill long-standing vacant community constable positions. • Create permanent relief positions and train appropriate voluntary discrete personnel to relieve permanent members when absent from the

APY Lands.

SAPOL should not proceed with its new model. I have written to Commissioner Grant Stevens and informed the government of our position. Hindley Street

The SAPOL district policing model has not only abandoned Hindley St police officers but also put the community at risk.

The area has a colourful history and a reputation for trouble. But one thing partygoers in the precinct could count on was permanent foot patrols in Hindley St, Rundle St, Rundle Mall and the surrounding areas.

That kept these highly charged areas safe, especially during the peak periods on Friday and Saturday nights.

And the sight of uniformed officers on foot patrol provided a strong deterrent for those who sought to create trouble.

But under the district policing model, this staple of Adelaide policing is now a thing of the past.

Eastern District members, who service the area, tell me that at times there is not a single officer on foot patrol in Hindley St or the surrounding areas.

Under the current model, Hindley St members can actually be called to jobs anywhere in the district. That means they might have to respond to jobs as far away as Unley or Parkside.

It’s hard to believe that SAPOL could implement a policing model devoid of permanent foot patrols in Hindley St.

The result is that the area and its surrounds are now an unsafe, out-of-control haven for anti-social behaviour, criminal activity and alcohol-fuelled violence.

SAPOL must take responsibility, and be held accountable, for the abject failure of its model insofar as it relates to the entertainment precinct.

It must: • Review the DPM model as it pertains to the Eastern District. • Provide permanent foot patrols in these high-risk city areas — across the full spectrum of shifts. • Increase the size of response patrol teams in the Eastern District and return them to the staffing levels that existed before the Stage 2 DPM rollout in

March 2020.

The public will simply not continue to accept the extreme Hindley St violence we see on our nightly news bulletins. SAPOL must act in the interests of frontline police and the public they serve.

Enterprise Agreeement

Police Association members recently voted to accept the new enterprise agreement.

It was an overwhelming endorsement — a 94 per cent “yes” vote — which confirmed my view that this was a strong agreement for our members.

We obviously negotiated the agreement in an extremely challenging economic climate. Despite this, we have emerged with a package that benefits our members financially and provides them with improved working conditions.

Particularly important is that we have not sold off any of our existing conditions and entitlements to achieve the outcome. This is actually a very significant — and often overlooked — aspect of enterprise bargaining.

Amid the difficult economic circumstances, the government also negotiated in good faith and offered a package that provides greater flexibility arrangements for members.

I acknowledge the significant contributions of association delegates and the committee of management in achieving this outcome.

And, during the entire enterprise bargaining process, the efforts of Police Association assistant secretary Steve Whetton were outstanding.

EDITOR’S NOTE: At press time, SAPOL informed Police Association president Mark Carroll that it intends to provide a “permanent foot patrol presence” in Hindley and Rundle streets, Rundle Mall and “surrounding environs”.

1

Finally, we meet

He was the 24-year-old cop, and she was the two-year-old whose life he saved. But, after the rescue, he would never see her again – until nearly three decades later.

By Brett Williams

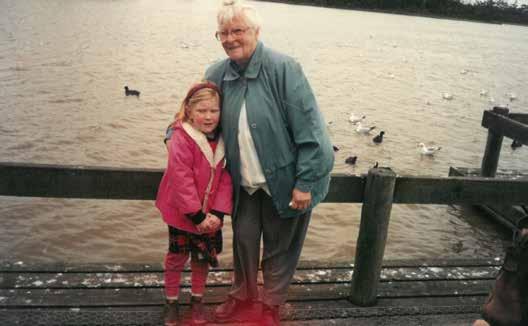

1. Clair, not quite two years old, at the Prospect house. 2. Cole receives the Star of Courage medal for bravery from the now late Dame Roma Mitchell at Government House in May 1994.

Finally, we meet

2

SHE WAS THE WOMAN HE HAD NOT SEEN FOR 27 YEARS. Not since she was two years old. But she had always remained firmly and affectionately in his thoughts. His connection to her was, after all, a life-and-death police incident, and it was too indelible in his memory ever to fade.

A raging Prospect house fire had threatened to kill her and another child back in 1993. Thenconstable Michael “Coley” Cole ran to the back of the house, kicked open one locked door and then another, and charged straight in to black, suffocating smoke.

His vision extended only about as far as the length of his arm, but he could see bright orange flames to one side of the house. He knew the two children were somewhere inside and could hear the cries of at least one of them.

Coley simply followed the sound until he found little Clair Anderson sitting on the living room floor, just a few metres from the flames. He scooped her up into his arms and rushed back outside with her to safety.

Indeed, he had saved her from a certain, horrific death and would ultimately receive the Star of Courage medal for his bravery.

And now came a chance for him to meet the grown-up version of the little girl he had not seen since the night of that fire. He had come to think of her as the daughter he had never known and longed to find out what she had made of her life.

Coley had discovered nothing about her over the years, and Clair was too young to have any memory of the fire, let alone the cop who rescued her. Bits of information she had picked up as she got older were sketchy.

“All I knew was that a police officer had kicked down the door and saved my life,” she says. “I didn’t know anything else about him. Nothing at all. ”

The pair’s reunion was to begin not face to face but rather with a phone call in February last year. And it would be the first time Coley, then 51, would ever hear Clair speak.

The sound of her crying, which led him to her in the fire all those years ago, was the only sound he had ever heard her make.

Today, still a little overwhelmed, he struggles to describe the moment he first heard her speaking voice, and the two-and-ahalf-hour phone conversation that followed.

“I was just so happy that I could finally speak to her,” he says, “and just hear that life (for her) was okay.

“She was telling me how she had a couple of kids, a partner, a business and was going on quite well. So, it was just really nice to hear. ”

Clair, who had never even known her rescuer’s name, thinks of those hours on the phone with Coley as “just so wonderful”.

“As soon as I talked to him, that first time he called me, it felt like I knew him already,” she recalls. “It was very strange.

“Straight away we just felt a connection; and he said: ‘I’ve always wondered about you and wondered how you turned out. ’

“I was just in tears. I was just crying and crying and crying. It meant so much to me that someone who had impacted my life felt the same about me, that I’d made an impact on his life.

“And then, because of the coronavirus, it was actually a little while before we got to meet face to face. ”

It was easy for Clair to make the decision to meet Coley in person. She found out he wanted to meet her when a SAPOL victim contact officer called her early last year.

Coley had sought the okay of his supervisor to initiate the contact, to find out if Clair was amenable to a meeting or totally against it.

He had sought consent once before, 15 years earlier, when Clair was 14. Her mother, however, would not allow her daughter to meet Coley and never told Clair of his approach.

“So,” Coleys says, “it sat with me for years that I really wanted to meet this girl. ”

Now it was up to Clair, and when the VCO put the question to her of meeting Coley, she felt “quite emotional”.

“But I was really, really interested in doing it,” she says. “She (the VCO) actually said: ‘Can I give Michael your phone number?’ And I said: ‘Yeah, absolutely!’ ”

Later that same February day, Coley rang Clair and the two revelled in their two-and-a-half-hour conversation.

Says Clair: “When we first spoke on the phone, Michael actually said: ‘You know, I feel like you’re the daughter I’ve never met.’ And that was really nice for me because my father passed away about six months after I was in the fire. So, I’ve grown up without a father. ”

Although Coley and Clair wanted to meet each other in person, the curse of the COVID-19 pandemic was to make them wait three months.

But, in that time, they kept up their contact through text messages and more phone calls. Then, finally, in May, came the day when each would see the face of the other after 27 years. And neither had the slightest idea what the other looked like.

“All I remembered was this little baby with blonde, gleaming hair,” Coley says. “And I remembered that (not from rescuing her but) from the Channel 7 news footage of the fire. ”

Coley drove up into the Adelaide Hills where Clair and her partner live with their two children and run their business. When the two came face to face, Clair found the moment “just overwhelming”.

“All these emotions come rushing over you,” she says. “As soon as I saw him all I wanted to do was just hug him. I just felt quite safe around him and quite comfortable.

“It’s very strange that you can have such a full-on connection with someone when you haven’t had anything to do with them before. But I literally do owe him my life. ”

And her life, of course, was just one of many topics she and Coley talked about that afternoon. He met, and had lunch with, the whole family but, outside on the deck, he and Clair talked privately for more than three hours.

Clair remembers “lots of tears and lots of laughs” as they discussed “anything and everything”. That included their families, and deeply personal details of their respective journeys through life in the nearly three decades since the fire.

“She’s a talker,” Coley says with a smile, “so there was no lull in the conversation. ”

But there did come a stretch of silence when Clair took to reading articles and documents Coley had brought with him about the fire.

He warned her that what those writings covered – like the death of the other child – had the potential to distress her. But, undeterred, Clair said simply: “I’d like to know. ”

No detailed account of the fire and the police response had ever been at hand for Clair. The briefest retelling of the story by her mother was all she had ever known. She had never even seen the news footage.

But now, after meeting Coley, she knew the cop who rescued her, the circumstances of the fire, and how close she had come to death.

3

3. Clair and her sons, Iggnatius and Archer, and partner, Gus, with Cole on a visit to his home last year. 4. Cole and Clair reunited after 27 years.

The joyous day of her reunion with Coley eventually came to an end but a special relationship between the two had only just begun. Like a father and daughter, they have remained close and frequently in contact.

Clair has visited the Cole home, dined with her rescuer and his family, and got to know the copper she calls “my hero”.

“I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Michael,” she says. “I just feel very at ease around him, very comfortable. We’re a bit the same, a bit antisocial, a bit quirky. I feel like he gets me. ”

Clair has also appreciated the presence of “a strong male influence” in her life.

“He’s just always there if I need him,” she says. “I feel very blessed that it’s someone like him that I’m able to have a relationship with. He’s an amazing person. ”

Coley stresses that finding Clair was never about him replacing, or even trying to replace, her father. His aim was simply to know that she was all right and to offer help, or just himself as a sounding board if ever she needed one.

“I just feel she’s family in a sense now,” he says. “She’s a character, she’s fun to be around and she’s good to talk to.

“She’s got a busy life, but I send her a message every couple of weeks and we try to have lunch together as often as we can. I’m pretty sure that we’ll be in touch now for the rest of our lives. ”

Clair, too, sees a lasting relationship for her and Coley.

“It made me feel really sad when I heard that he’d reached out (when I was 14) and I hadn’t got to meet him,” she says. “So, it’s been really nice that I got that second opportunity.

“I don’t see him not being in my life. He’ll be there forever now. That’s the way I see it. ”

THE FIRE

It was around 1 o’clock on a Saturday morning in March 1993 when Constable Michael Cole responded to a Prospect house fire. A motorist had stopped him just moments earlier on Prospect Road to alert him to the blaze on Braund Road.

As he approached 96 Braund Road in his patrol car, he could see thick plumes of black smoke billowing into the air. And then, as he pulled up, he noticed a dozen-odd screaming, panicked people gathered on the road out front.

He could also see smoke and flames burning furiously at a window on the northern side of the house. Bystanders were trying to put that fire out with a garden hose, as others made the same attempt on the southern side of the house.

Then someone among those gathered out front yelled out to Coley that two children were inside the house. Coley moved instantly to draw more information from those people, who believed that one child was in the room with flames pouring out of its window.

And as best those bystanders knew, the other child, Clair, was in a room toward the back of the house.

With that information, Coley sprinted around to the back of the house, kicked down those two locked doors and charged into the inferno. Although the smoke limited his vision to the length of his arm, he could see the bright orange flames burning in that northern room.

At the same time, he could hear little Clair crying and followed that sound until he found her sitting on the floor of the living room. As he picked her up and carried her out of the house the smoke grew thicker and he began struggling to breathe.

“I certainly remember her crying,” he says. “I just scooped her up and I’m yelling at her: ‘Where’s the boy? Where’s the boy?’ Like a two-year-old’s going to be able to tell me that.

“In hindsight you think: ‘Oh, God, what’d I do that for? Poor kid. All she’ll remember is a copper yelling at her.’ ”

Once outside with Clair, Coley handed her to a bystander, whom he told to give the child to her mother. He then grabbed a piece of child’s clothing, soaked it in water, wrapped it around his face, and charged back into the house.

Although he now had almost zero visibility, he made his way to that northern room in which the fire had indeed trapped the three-year-old boy. The room was so full of raging flames that Coley could not even distinguish items such as furniture.

“You just couldn’t get in there,” he remembers.

In the intense heat and with thick, stifling smoke filling the house, Coley simply could not breathe and had to retreat. But he still refused to abandon the little boy and made four more courageous entries into the house to find and rescue him.

On his last entry, he could see the light of a torch in a passageway and hear the voices of two of his colleagues.

Kevin Brown and Ian Rowe had arrived on the scene and were now in the house, crawling on their hands and knees in search of the boy. The then-constables would both earn the Australian Bravery Medal for their actions.

One of them shouted a warning to Coley that the roof was on fire and might at any moment collapse.

Coley reluctantly accepted that he could do no more and made his final exit from the house. He had never had any real chance of saving the boy, but the death left him shattered.

5. Cole receives the SAPOL Police Bravery Medal from now late former commissioner David Hunt during a graduation ceremony at Fort Largs in December 1993. 5

6 6

7

8

Later, after he had been to hospital for suspected smoke inhalation, Coley returned to the house, where he spoke with fire techs analysing the scene.

“They talked me through it,” he says. “They said: ‘Look, the fire was well and truly going before you even got here. That child wouldn’t have made it. Nothing you could’ve done, Coley, would’ve saved him. ’

“It would’ve been hard to live with not knowing if I could’ve got him out but talking to the fire techs eased my mind. I couldn’t have done anything else.

“So, I’m just really happy that Clair’s here and enjoying her life. And I’m glad I played a part in her having that life. ”

Clair has not lived with any memories of the fire or her rescue. But she has, throughout her life, felt particularly uneasy around fire.

Whenever it came to sitting near a campfire, or her mother simply lighting the oven, Clair would “freak out”. She even became stressed when she visited friends’ homes in which open fires were burning.

“I’d sit there,” she says, “and I’d start to feel too hot. And then I’d start to feel like I couldn’t breathe. So, I couldn’t be around fire at all.

“I actually had to go through a lot of hypnotherapy to be able to even deal with it. ”

Police found, in their investigation of the fire, that the children had lived with their mothers in the rented threebedroom house since January 1993. The cause of the fire appeared to be two lit candles left in the children’s bedroom.

Clair was not in the bedroom that night because she had fallen asleep in the living area. PJ

6. Clair, at the age of 4, seated at a drum kit in the home of a family friend. 7. At age 6 with her maternal great grandmother in Victoria. 8. Clair aged 5 with the daughter of a family friend.

Farewell, vice-president

Outgoing Police Association vice-president Allan Cannon has such high regard for cops that, even in retirement, he intends to keep his watchful eye on them. He swears that if he ever spots, say, a solo traffic cop in trouble, he will “jump back in” as back-up for the officer. And, if his devotion to working cops does indeed continue, it will add to the 20-odd years he has already served them as a Police Association official. Back when the Taser became the law-and-order issue of the day, Cannon provided one of the best examples of his never-give-up approach. “I was always respectful but quite forceful about it,” he explains. “I brought to the association board table the possibility of our members being issued with Tasers. The benefits of a non-lethal option for police were obvious. “It got to the stage where, at every meeting,

I’d come to the table with the issue and it was almost a continuous agenda item for me. “I would bring in examples of what had happened at Elizabeth LSA and how the police would’ve been best served to have Tasers. ” And with Tasers now commonplace in SA policing, few could argue that Cannon was wrong to take such a dogged approach to the issue. The outcome was a win for Police Association members, who now take to the road with that life-saving tool of their trade. Cannon, 61, has started to reflect on many other wins, too, as he steps down from the vicepresidency and brings his association service to a close. He is also leaving police work behind as he moves into retirement this month.

vice-president

Cannon thinks of the Protect our Cops campaign of 2015 as the greatest association victory during his time as a committee member.

Its crescendo was a march on Parliament House. Association members rallied there in protest after the Weatherill Labor government had stripped away their work-injury entitlements under the Return to Work Act.

“That act was an abysmal piece of legislation,” Cannon says. “So, our president, Mark Carroll, and his staff had to come up with strategies, and our own version of what the legislation should provide.

“Mark had the right argument against it and the ability to lobby politicians. And I was in Parliament House when different MPs read statements about it.

“Robert Brokenshire, with a Police Journal in hand, made his impassioned plea to the House to recognize the role of police as unique. It was a pleasure to be there for that.

“Mark led the march, we held our nerve, and in the end, the outcome was truly magnificent. ”

Outcomes the association has achieved in enterprise bargaining are others in which Cannon takes great pride. He attributes them to the mastery of Mark Carroll and former president Peter Alexander as negotiators.

“The results are in black and white for everyone to see,” he says. “Our working conditions and our pay are exceptional.

“Peter steered us through some very difficult times. And Mark has taken us through most of the EB era with outstanding results. We still have never ever lost any conditions.

“Mark’s leadership has been first-rate. Our results prove that. He knows how to interact with not only government but also the community. ”

Cannon has always had great respect for the luminaries of the Australian police labour movement, particularly those he has sat with at the association board table.

He still remembers, and admits that it was daunting, when in 2005 he took his seat at his first committee meeting. Up until then, he had served as a workplace delegate for four-and-ahalf years, first at Port Pirie (1998-2002) and then Elizabeth (2004-2005).

“I was in awe of some of the committee members at that time,” he says. “I looked around the table and just thought: ‘Wow! I’m honoured.’ And that honour will last with me forever. ”

Cannon had first come to involve himself with the association after he was, in his judgement, unfairly denied promotions.

He became so committed to the union that he ran for and won his seat on the committee of management in 2005 and the vice-presidency in 2011. And, like his fellow committee members, he has had to study reams of legislation and be thoroughly across police industrial issues.

Soaking up that knowledge has been critical to his capacity, and that of others, for boardroom decisions on behalf of almost 5,000 cops.

And just as critical was always his knowledge of the front line, where Cannon worked for all but the last seven of his 38-and-a-half years in policing.

Still strong in his memory, after 30-plus years, are fatal crashes he responded to in Port Augusta – two of them in just two weeks.

Three elderly women died in one crash involving a semi-trailer on Highway 1. The other crash, a head-on between two cars on the Port Augusta to Quorn Road, left one child and two adults dead.

And, for Cannon, certain SIDS cases brought an extra layer of emotion. He had to deal with three of them when he and his wife, Lesley, were expecting the first of their three daughters.

“They were the jobs I didn’t tell her about,” he says. “But we’ve shared a lot, and she’s always been my sounding board. ”

Cannon would never have stepped away from his front-line job as a Gawler patrol sergeant had he not suffered two serious injuries. The first, a shoulder separation, came about as he was restraining a young man suffering mental ill health.

Soon after that incident came his second injury, a hip fracture, which was the result of slipping over out back of the Gawler police station. That mishap necessitated a hip replacement and, ultimately, a role in a non-operational field.

In 2013, Cannon took on the job of course mentor to cadets at the police academy, from where he is now ending his career.

“I’ve done seven years at the academy and run eight courses,” he says. “And, apart from that, I’ve had at least something to with 1,000odd cadets. It’s been fabulous to provide context for them from what I’ve learnt. ”

On the day his time is up as union vicepresident, and as a police officer, association life member Cannon expects to feel “melancholy”. But that feeling might well subside if he gets to see more rank-and-file interest in official association roles.

“That would be nice,” he says. “The more people concerned about their workplace the better. And I think we’re missing out on some exceptional people who could well play significant roles on the executive committee.” PJ

Senior Sergeant 1C Lloyd “Colonel” Sanderson (ret) leads riders out of the Taperoo police academy to start the 2020 Wall to Wall Ride for Remembrance.

Ride supporting Police Legacy – and rural SA

By Nicholas Damiani

SO MANY POLICE OFFICERS

KNOW THE OVERWHELMING PAIN OF LOSING A COLLEAGUE IN THE LINE

OF DUTY. For them, and their families, it is one of the darkest realities of police work, and it factors into every shift on the front line.

The Wall to Wall Ride for Remembrance commemorates the great sacrifice of the fallen, as well as the enduring service of Australian police officers. It also raises muchneeded funds in support of police charitable organizations.

For more than a decade, the event has culminated in riders from all the nation’s police jurisdictions making the trip to the National Police Memorial in Canberra.

1 2

6 3 4

7 5

But, last September, with COVID-19 restrictions in place, each jurisdiction had to take responsibility for organizing a ride within its own state borders.

So, SA members organized an epic five-day ride through some of the state’s most rugged terrain, with around 100 participants covering over 2,200km.

The ride began at the police academy and progressed to a series of locations and police stations, including Nuriootpa, Kapunda, Clare, Wallaroo, Kadina, Quorn, Port Augusta, Barmera, Berri and Robe.

Ride organizer and Police Association member Senior Constable First Class Mick Klose said a couple of the ride’s most treasured highlights were the visits to Booleroo Centre in the southern Flinders Ranges and Riverland Special School in Berri.

“We brought smiles to the students of the Booleroo Centre school and elderly residents of the Booleroo Health Centre,” he said.

“And a few riders made the effort to ride by the Riverland Special School students, which brought much joy and excitement to the children with intellectual disabilities. ”

And SA’s rural economy enjoyed a surprise economic boost from the ride, according to SC1C Klose, with riders making a particular effort to support local businesses.

“Cafés, bakeries, pubs, diners, and fuel stops – they all benefited from our ride,” he said. “It was a bit of a cash injection to the SA regional economy. ”

And, proving that cops never lose their sense of humour, SC1C Klose highlighted that a new “fine” system had been set up this year to raise even more funds.

“It was for indiscretions, be it a bike falling over, a rider falling off, or leaving something behind, or showing a behind,” he laughed.

“Didn't matter the reason. The members were generous in the offending and in the giving. ”

Ordinarily, a rider from each jurisdiction has the task of carrying a special baton with a hollow centre reserved for the names of fallen members.

This year, however, restrictions prompted an agile reshuffle of the carriage of the batons.

“(Former senior sergeant) Adrian Burnett and friends rode to the WA border and collected the WA baton, Bully (David Reynolds) and friends rode to Darwin and collected the NT baton,” SC1C Klose explained.

“Bob Stewart collected the three batons at Orroroo and rode to Canberra to represent the three states (SA, WA and NT) at the national service. ”

Among those remembered in 2020 were four police officers killed when a truck crashed into them in the emergency lane of the Eastern Freeway in Melbourne last April.

They were Constable Josh Prestney, Leading Senior Constable Lynette Taylor, Senior Constable Kevin King and Constable Glen Humphris.

SC1C Klose explained that all funds raised from the ride go toward SA Police Legacy.

“SA Wall to Wall will also top it up to $13,000 for 2020, and a grand total of $90,000 over the 10 years of the ride,” he said.

“Our goal is to reach $100,000 for 2021.” PJ

1. New Wall to Wall group member Ken Field at Booleroo Centre with a photo of his father who was a SAPOL motorcycle officer. 2. Constable Joshua Prestney. 3. Leading Senior Constable Lynette Taylor. 4. Senior Constable Kevin King. 5. Constable Glen Humphris. 6. Police Association president Mark Carroll and Senior Constable Mick Klose (left) present Police Legacy president Senior Sergeant Mark Willing with a cheque for $7,786.40. 7. Riders gathered together at Kadina on day two of the ride.