Atelier De Raffaello Sanzio dit Raphael

(Urbino 1483 -1520 Rome)

La Sainte Famille avec l’enfant Saint Jean-Baptiste

The Holy Family with the infant Saint John the Baptist

Plume et encre brune, lavis brun, sur pierre noire Porte une inscription en bas à gauche : « del Sarto »

19.2 x 27.5 cm

Provenance :

• Collection particulière, France.

Pen and brown ink, brown wash, over black chalk Bears an inscription lower left: « del Sarto »

19.2 x 27.5cm

Provenance:

• Private collection, France.

12 02 |

Œuvre en rapport :

Tondo Cava dei Tirreni, d’après les dessins de Raphael et probablement exécuté par Gian Francesco Penni, élève de Raphaël.

Related work:

Tondo Cava dei Tirreni, after drawings by Raphael and probably executed by Gian Francesco Penni, pupil of Raphael.

La technique et le style de cette feuille, dessinée à la plume et partiellement ombrée au lavis brun, sont caractéristiques du graphisme d’artistes oeuvrant dans l’atelier de Raphaël. Elle témoigne de l’importance du travail de dessin dans l’atelier du Maître mais aussi de la constitution de répertoires de motifs utilisés dans des oeuvres peintes et de la continuelle référence en peinture à une forme précédemment élaborée par le dessin. Elle illustre comment l’usage de la plume et l’encre brune, qui permettait d’allier souplesse et précision, conduisit à la recherche d’un certain réalisme dans la représentation de la figure humaine sous les drapés. La régularité des contours à la plume, l’application économe du lavis posé avec délicatesse, sont typiques de la manière graphique de l’entourage proche de Raphaël.

Notre dessin est un précieux témoin du processus créatif de l’atelier du Maître d’Urbino puisqu’il est exécuté d’après une création de Raphaël à travers le prisme de Penni. L’un des premiers élèves de Raphaël fut Gianfrancesco Penni, dont le rôle dans l’atelier très actif du Maître était principalement celui d’exécuteur des dessins du maître, à la fois des fresques et des peintures sur panneaux. Il entra dans l’atelier en 1511 et reçut le surnom Il Fattore . Vasari rapporte que la spécialité de Penni consistait en la production de dessins finis d’après les créations de Raphaël, ne facilitant pas la reconstitution de son oeuvre qui demeure hypothétique. Toutefois un groupe de dessins produits dans l’atelier du Maître présente suffisamment de points communs permettant de les assigner à sa main et de définir les caractéristiques de son graphisme. Ils nous renseignent également sur son rôle au sein de l’atelier, comme de son degré d’assimilation des préceptes graphiques de Raphaël.

14

15

La situation est encore compliquée par l’existence de ce que l’on pourrait appeler des modelli rétrospectifs. Notre feuille en est un exemple, puisqu’elle est à mettre en rapport avec le dessin conservé à l’Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (inv. no.WA1940.68; voir RCIN 851309, reproduit ci- contre) généralement attribué à G. F. Penni et considéré comme une étude préliminaire pour un tondo qui lui est traditionnellement attribué et conservée au Museo della Badia di Cava dei Tirreni, Salerne.

Une autre copie du dessin se trouve au Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Florence (inv. no. 10899F; voir RCIN 851311). Une version peinte verticale de cette composition, généralement attribuée à l’école de Raphaël (Gianfrancesco Penni ou Perino del Vaga ?), se trouve à la Galleria Borghese, Rome (inv. no.464).

Un dessin représentant le groupe principal mais avec une variation dans la pose de Saint Joseph et l’ajout de nombreuses figures de chaque côté a été répertorié par Ruland (1876) comme étant alors en la possession de feu le major Kühlen, Rome, peut-être celui qui est apparu sur le marché en 1991 (Lempertz, Köln; 12 décembre 1991, lot 483) - (Voir RCIN 851308, Royal Collection Trust, Windsor).

Les différences, à la fois évidentes et subtiles, entre le modello et la peinture pourraient être considérées comme la preuve que Raphaël ne peut pas avoir préparé de dessins, mais seulement des études. Les figures de premier plan sont travaillées dans le dessin à la plume et à l’encre sur des croquis initiaux à la pierre noire. Notre feuille se distingue cependant par la façon dont les contours doux, les contraposti mouvants et les gestes interactifs des personnages lient à la fois les individus et la disposition en frise de la Sainte Famille. Le thème de la mère et de l’enfant prend une tonalité terrestre sous l’influence de Raffaello. L’artiste d’atelier a capturé un moment de tendresse. L’aisance et la grâce de la Vierge évoquent l’esprit de Raphaël, bien qu’elle soit moins robuste que la plupart de ses figures féminines ; les interprétations de Penni affirment invariablement les formes de son maître. L’influence de Raphael et celle de Penni s’accentue ici et insuffle un équilibre toujours plus prononcé.

Sans être une copie servile, la pose de nos personnages s’inspire des modèles de Raffaelo. Le thème de la composition elle-même est de la même lignée. La même pureté stylistique et les mêmes types physiques de la Vierge, de Saint Joseph, de l’Enfant et de Saint Jean-Baptiste apparaissent ici.

16

The technique and style of this sheet, drawn in pen and partially shaded in brown wash, are characteristic of the draftsmanship of artists working in Raphaël’s studio. It testifies to the importance of drawing work in the studio of the Master, but also to the constitution of repertoires of motifs used in painted works and to the continual reference in painting to a form previously elaborated by drawing. It illustrates how the use of pen and brown ink, which allowed to combine flexibility and precision, led to seek a certain realism in the representation of the human figure under drapery. The regularity of the pen outlines, the sparing application of the wash applied with delicacy, are typical of the graphic style in the circle of Raphaël.

Our drawing is a precious witness to the creative process in the workshop of the Master of Urbino: it is executed after a design by Raphaël through Penni’s prism. One of Raphael’s first pupils was Gianfrancesco Penni, whose role in the industrious workshop was primarily that of executant of the master’s designs, both frescoes and panel paintings. He entered the workshop in 1511 and received the nickname Il Fattore. His nickname suggests an administrative role in Raphael’s workshop. Vasari reports that Penni’s specialty consisted in the production of finished drawings after Raphael’s creations, not facilitating the reconstruction of his work which remains hypothetical. However, a group of drawings produced in the Master’s workshop has enough common points to attribute them to his hand and define the characteristics of his draughtsmanship. They also tell us about his role within the studio, as well as his degree of assimilation of the graphic precepts of Raphaël.

The situation is further complicated by the existence of what might be called retrospective modelli . Our sheet is an example of this, since it is related to the drawing in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (inv. no.WA1940.68; see RCIN 851309, reproduced opposite) generally attributed to Gian Francesco Penni and considered as a preliminary study for a tondo traditionally attributed to him, in the Museo della Badia di Cava dei Tirreni, Salerno.

Another copy of the drawing is in the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Florence (inv. no. 10899F; see RCIN 851311). A vertical painted version of this composition, generally attributed to the school of Raphael (Gianfrancesco Penni or Perino del Vaga?), is in the Galleria Borghese, Rome (inv. no.464).

A drawing representing the main group but with a variation in the pose of Saint Joseph and the addition of numerous figures on either side was listed by Ruland (1876) as being then in the possession of the late Major Kühlen, Rome, possibly be the one that appeared on the market in 1991 (Lempertz, Köln; December 12, 1991, lot 483) - (See RCIN 851308, Royal Collection Trust, Windsor).

Differences, both obvious and subtle, between the modello and the painting might be taken as evidence that Raphael cannot have prepared drawings, but only studies. Foreground figures are worked up in the drawing in pen and ink over initial black chalk sketches. What distinguishes our sheet, however, is the way in which the soft outlines, shifting contraposti and interactive gestures of the figures bind both the individuals and the frieze arrangement of the Holy Family. The theme of mother and child takes on an earthly tone under the influence of Raffaello. The artist captured a moment of tenderness. The ease and grace of the Virgin evoke the spirit of Raphael, although she is less robust than most of his female figures; Penni’s interpretations invariably affirm his master’s forms. The influence of Raphael and Penni, which had always been strong, became even more pronounced here and infused a more marked balance.

Without being a servile copy, the pose of our characters is inspired by Raffaelo’s models. The theme of the composition itself is of the same line. The same stylistic purity and the same physical types of the Virgin, Saint Joseph, the Child and Saint John the Baptist appear here.

17

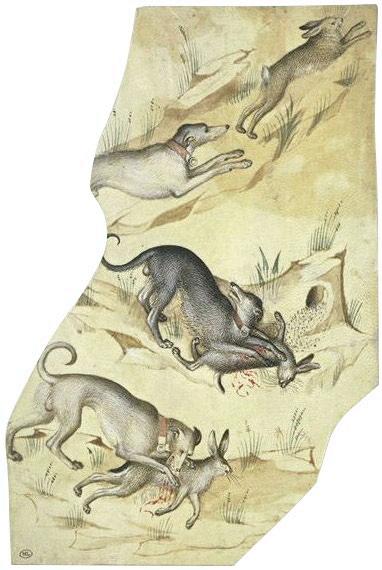

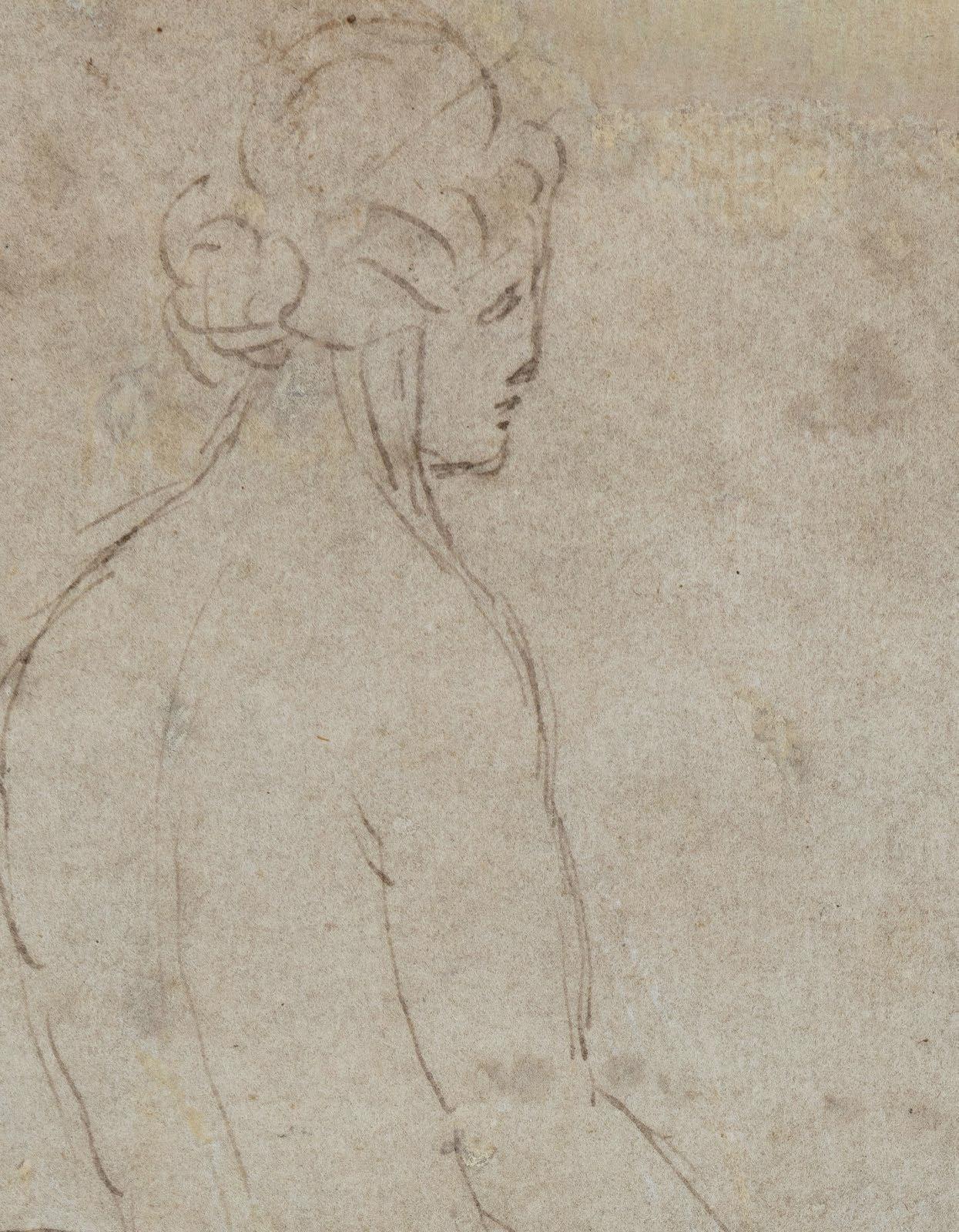

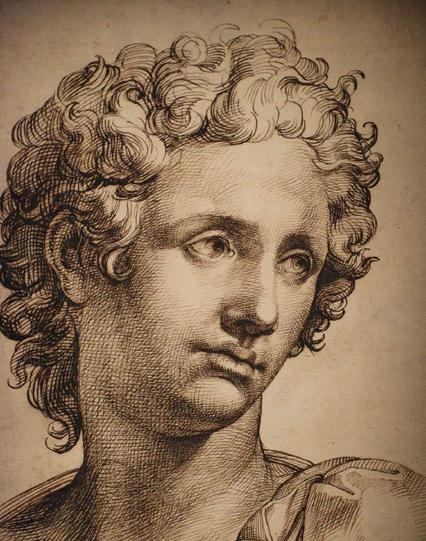

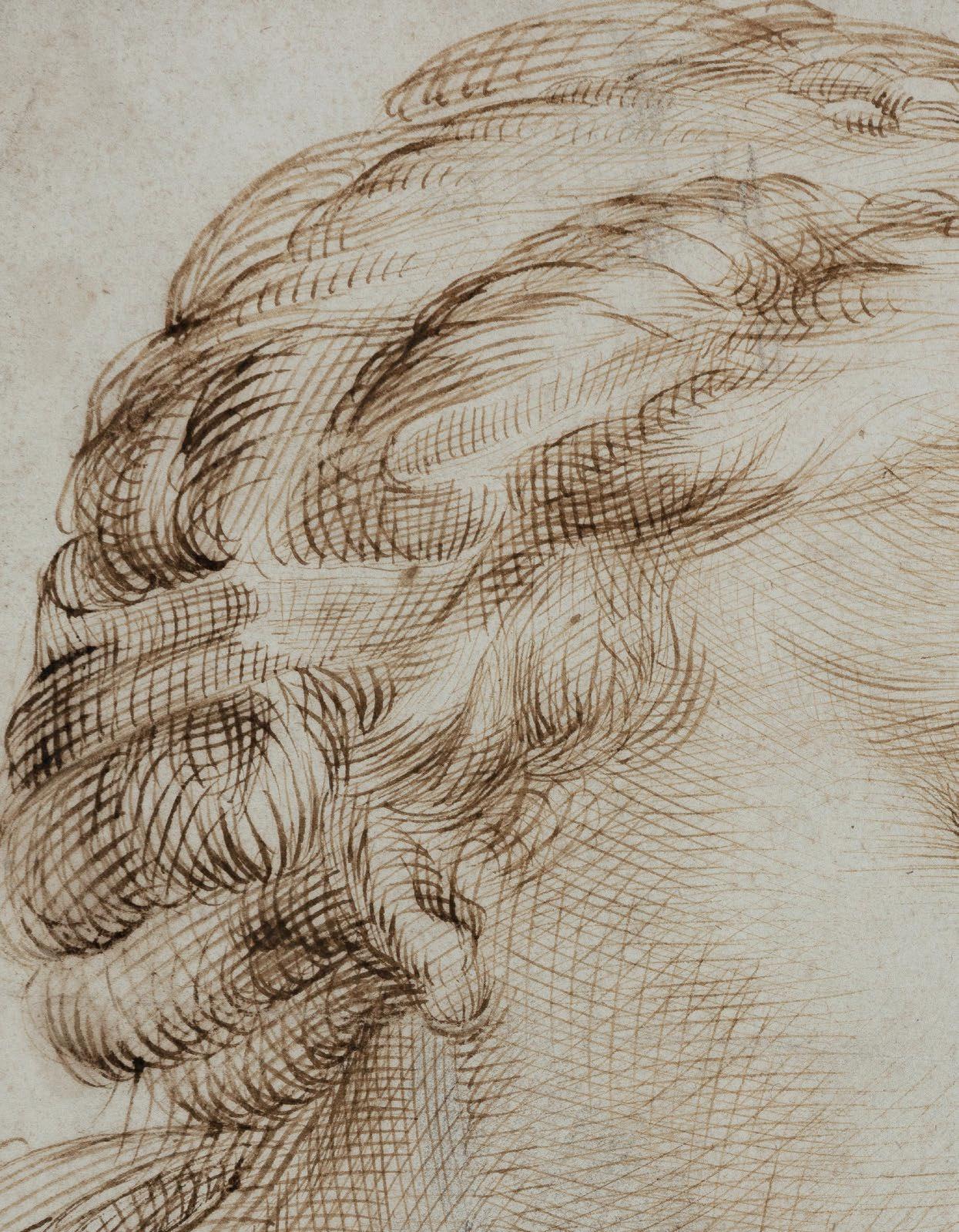

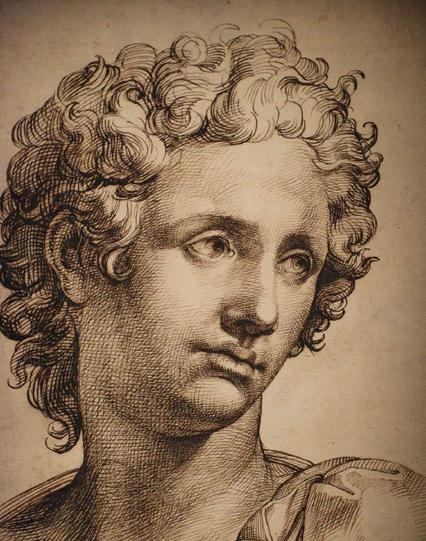

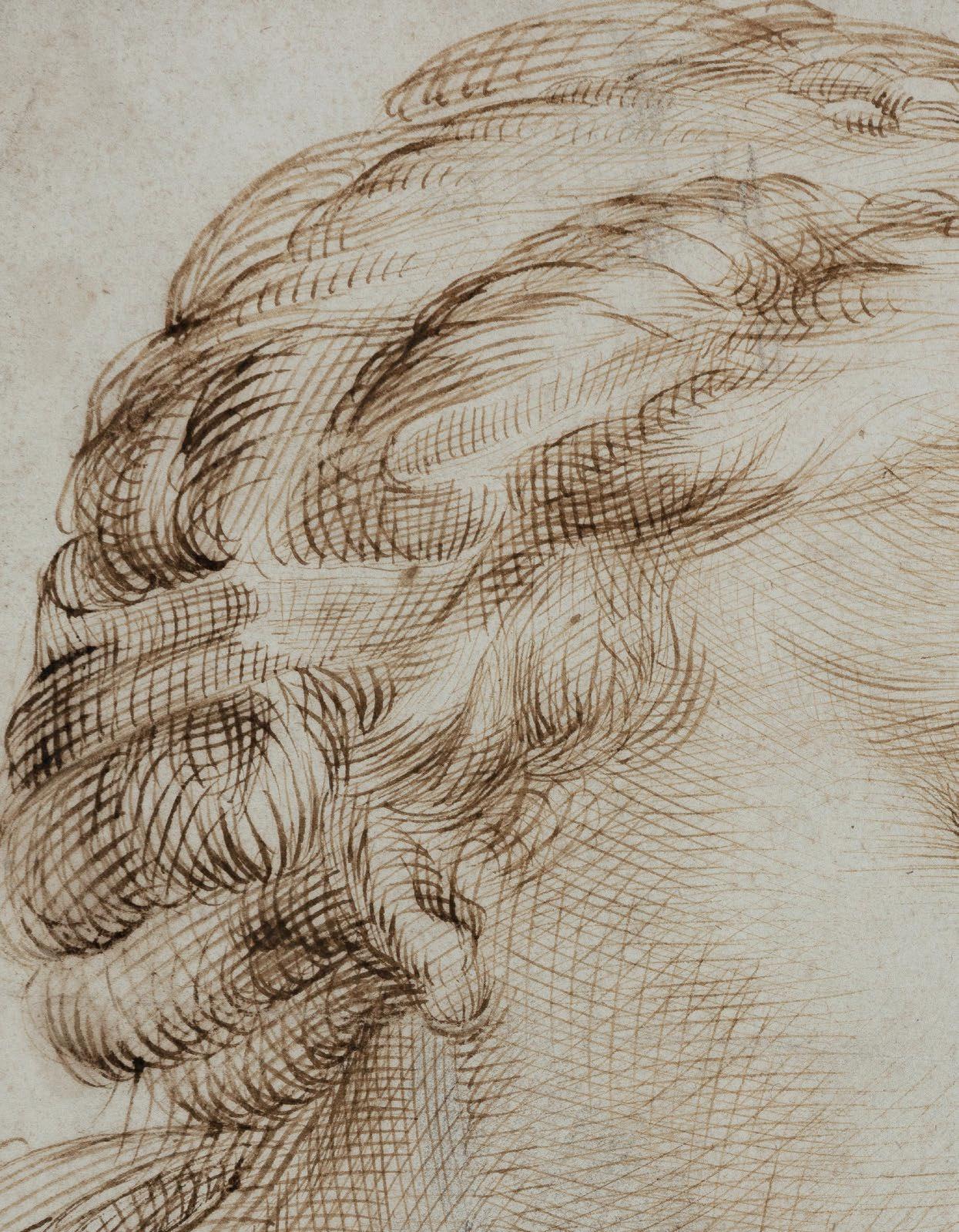

Timoteo Viti

ou Timoteo Della Vite

(Urbino 1469-1523)

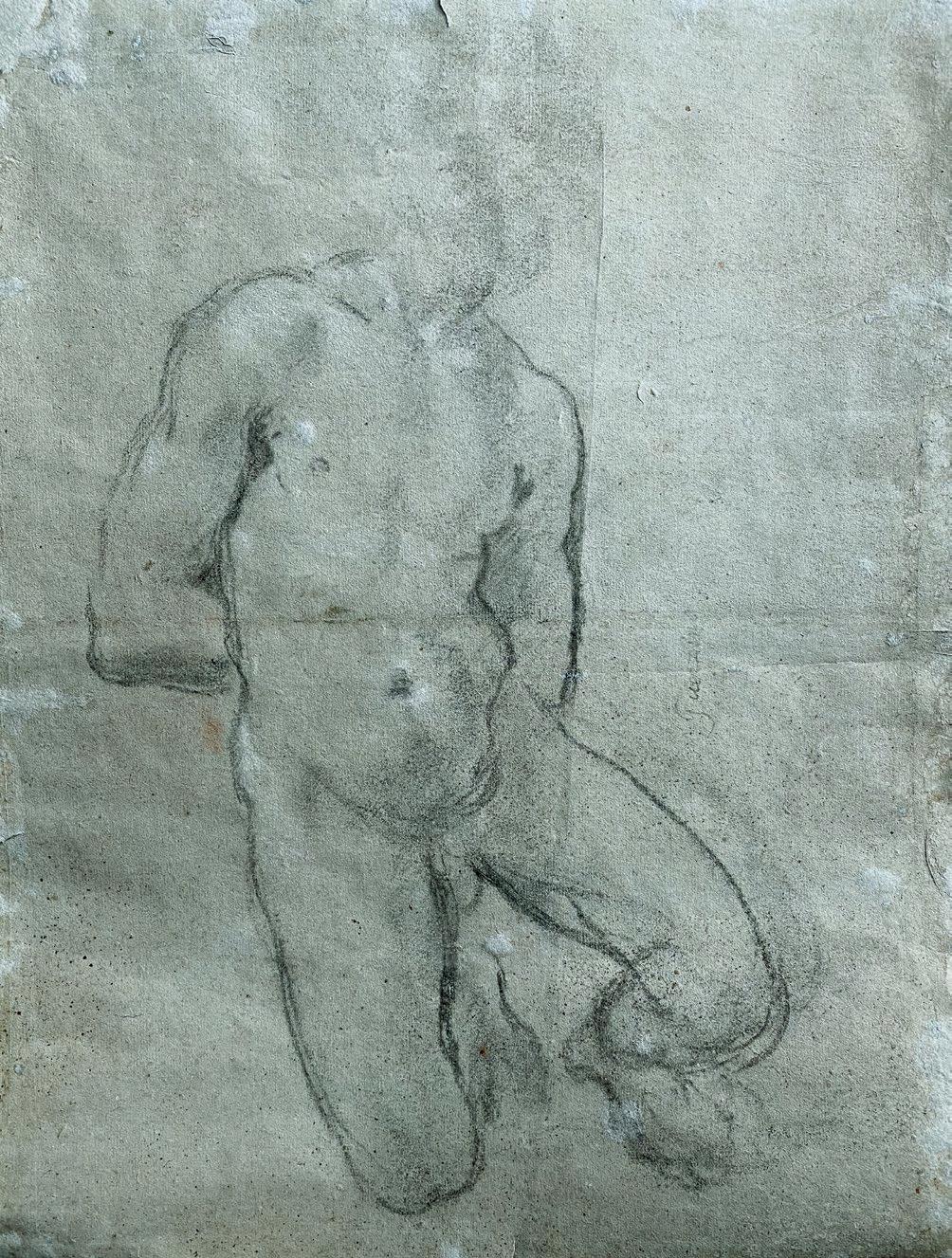

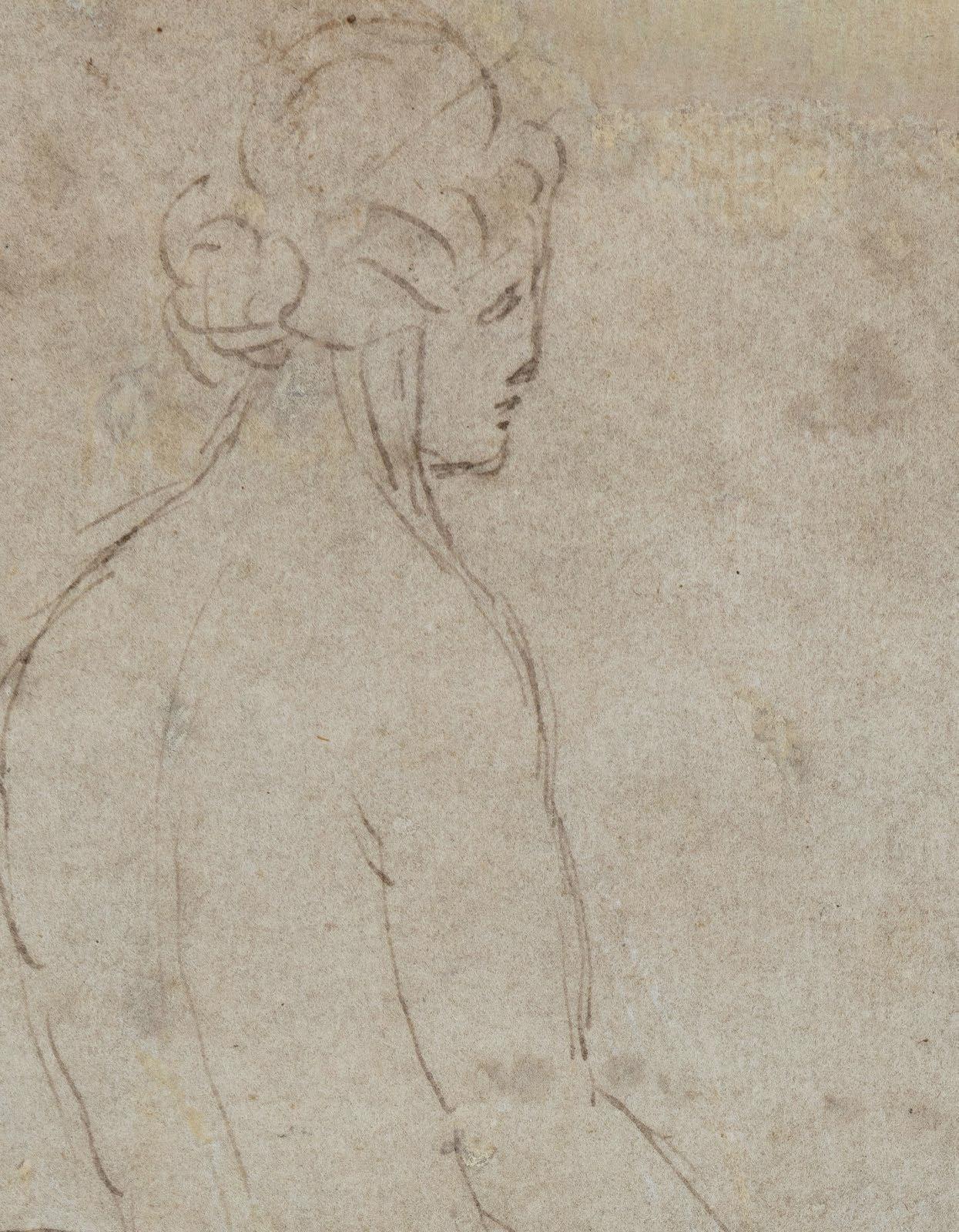

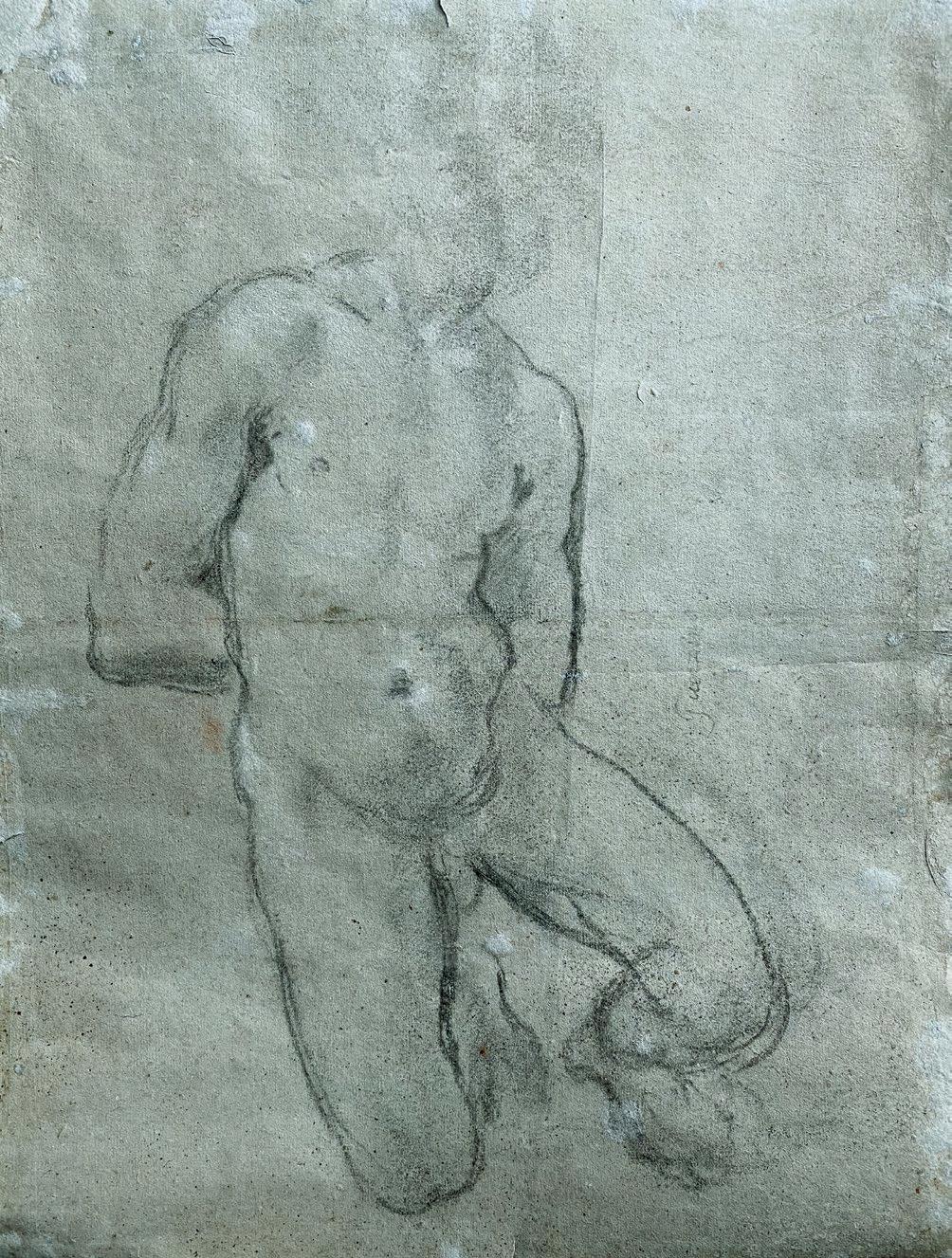

Étude de femme nue, vue de dos, tournée vers la droite Study of a female nude, seen from behind, facing right

Plume et encre brune

28,2 x 12 cm

Provenance :

• Timoteo Viti (1469-1523), puis par descendance à la famille Antaldi, Urbino (L. 2246), inscription à l’encre au recto en bas à gauche ‘.R.V.’, puis par descendance à Marchese Antaldi, Pesaro;

• Vente Christie’s London, 6 Juillet 2004, lot 5 (comme attribué à);

• Collection particulière, France.

Pen and brown ink

28.2 x 12cm

Provenance:

• Timoteo Viti (1469-1523), then by descent to the Antaldi family, Urbino (L. 2246), ink inscription on the front lower left ‘.R.V.’, then by descent to Marchese Antaldi, Pesaro;

• Sale Christie’s London, July 6, 2004, lot 5 (as attributed to);

• Private collection, France.

18 03

|

Nous remercions Monsieur Paul Joannides d’avoir confirmé l’attribution à Timoteo Viti après examen de l’oeuvre, précisant que notre dessin montre l’influence de Raphaël et qu’il fut probablement exécuté en 1511-12 lorsque l’artiste travaillait avec le Maître et était devenu familier de ses études de nus de femme. Notre étude fut certainement conçue pour prendre place dans une scène narrative.

Cette charmante feuille semble ainsi être étroitement liée à la tradition ombrienne vers 1510 vue par le prisme Raphaélesque. Selon Vasari, Timoteo Viti a d’abord suivi une formation d’orfèvre. Il part ensuite étudier à Bologne, où son intérêt se tourne vers la peinture, puis revient à Urbino, y connaissant un succès considérable après la mort du père de Raphaël, Giovanni Santi.

Exécutée à la plume et à l’encre, la feuille est ici présentée comme une œuvre de Timoteo della Vite en raison d’étroites similitudes avec ses dessins datant de la fin du XVe siècle, alors que le nom de Raphaël, à qui le dessin a été donné dans le passé, tel qu’il fut inventorié par la famille Antaldi, apparaît dans l’inscription en bas à gauche (“ R.[aphael] V[rbinas] ”). Les comparaisons incluent l’esquisse de Viti du Miracle de la vache démoniaque , plume et encre brune, 26,5 x 40,9 cm, inv. N.1458, Albertina, Vienne ; dans laquelle le nu masculin à gauche de la composition fait indéniablement écho à notre étude de femme ; ainsi que l’Etude pour une Crucifixion, vers 1504-1509, plume et encre brune, 31,9 x 21,1 cm, Inv. MTC 5051, provenance: Comte Etienne- Marie de Saint Genys (1856-1915); legs Saint-Genys à la Ville d’Angers, Février 1917, Musée d’Angers (ci-contre). C’est à Viti que Philip Pouncey a rendu en 1977-1978 cette saisissante variation autour du thème de la Crucifixion qui daterait de la période où l’artiste collabore avec Genga. Le style de notre croquis est proche de celui des nus masculins affairés au pied de la croix du Larron de gauche, dans lesquels on retrouve l’usage systématique de petites hachures parallèles pour suggérer les ombres. D’autres analogies avec la manière de l’artiste se retrouvent également dans deux études de nus conservées à l’Ecole des Beaux Arts de Paris: Nu masculin debout, pierre noire, 34,3 x 14,2 cm, N° 433 et Etude de femme nue, debout, vue de dos, et étude d’homme vu de profil, pierre noire, 32,4 x 19 cm, N° 432.

Raphael (Lugt L.2246), GGV pour Girolamo Genga et TVV pour Timoteo Viti, le dernier V désignant Urbino d’où sont originaires les trois artistes. Les marquis Antaldi descendaient du peintre Timoteo della Vite, le maître, l’ami, et plus tard l’imitateur de Raphaël (L.2463). Timoteo della Vite a obtenu ou hérité du groupe le plus important des dessins d’atelier de Raphaël, peut-être le plus bel ensemble qui fût jamais réunie dans une collection particulière. Il les obtint probablement à la mort du maître. Ces dessins, ou au moins la plus grande partie, restèrent longtemps en possession des héritiers de Timoteo Viti, la famille des Antaldi à Urbino. La collection était déjà morcelée au XVIe siècle lorsque le fils de Timoteo vendit quelques dessins à Vasari, mais la plupart des dessins furent dispersés en 1714, lorsque Crozat acheta une partie de la collection, et en 1828 lorsque le reste fut vendu à Samuel Woodburn. La collection Viti contenait un certain nombre de dessins de Viti copiant des dessins de Raphaël. Les initiales de Raphaël, reproduites ci-contre, furent ainsi apposées sur les dessins longtemps après Timoteo, probablement au XVIIe siècle, par un membre de la famille Antaldi, qui n’était certainement pas un connaisseur sévère, car la marque fut trop libéralement employée et mise sur nombre de dessins d’élèves, d’imitateurs et de copistes tels que Timoteo lui-même. Ce cachet ne donne donc pas la garantie d’authenticité qu’on lui a souvent voulu reconnaître, il est un témoignage d’ancienneté et une indication de provenance. Les dessins ont souvent été disputés entre les deux artistes dans le passé.

Formé à la fin des années 1490 dans l’atelier bolonais de Francesco Francia, Viti a été très influencé par la manière ornementale stylisée de Giovanni Santi, le principal peintre d’Urbino pendant sa jeunesse. Viti et Raphaël, fils de Giovanni Santi travaillèrent ensemble en 1508-10 sur la décoration à fresque de la chapelle Chigi à S. Maria della Pace, Rome. Il a été suggéré qu’il est représenté (comme le peintre grec ancien Protogène) dans L’École d’Athènes , l’œuvre la plus célèbre de Raphaël, debout à côté de l’autoportrait de Raphaël, bien que Vasari ne mentionne pas cette identification. Le style mature de Raphaël l’a influencé longtemps par la suite, comme on peut le voir dans le grand retable représentant Noli me Tangere et dans notre étude.

Ce dessin appartenait à Timoteo Viti, qui a travaillé avec Raphaël, et lui a survécu trois ans. Probablement après la mort de l’artiste, Viti a rassemblé un grand nombre de dessins de Raphaël. Ces dessins ont été marqués au XVIIe siècle par un descendant de Viti, souvent de façon imprécise, avec les initiales des artistes, R.V. pour

Il a occupé une place dominante sur la scène artistique d’Urbino pendant près de trois décennies. Dessinateur et peintre habile, Viti a joué un rôle essentiel dans la diffusion du vocabulaire artistique de la manière de Perugin et Francia dans les régions du centre de l’Italie.

20

21

We are grateful to Paul Joannides for having confirmed the attribution to Timoteo Viti after examining the work. He noticed that our drawing shows the influence of Raphael and that it was probably executed in 1511-12 when the artist was working with the Master and had become familiar with his studies of female nudes. Our study was certainly designed to take place in a narrative scene.

This charming sheet thus seems to be closely linked to the Umbrian tradition around 1510 seen through the Raphaelesque prism. According to Vasari, Timoteo Viti first trained as a goldsmith. He then left to study in Bologna, where his interest turned to painting, then returned to Urbino, enjoying considerable success there after the death of Raphael’s father, Giovanni Santi.

Executed in pen and ink, the sheet is presented here as a work by Timoteo della Vite because of close similarities with his drawings dating from the end of the 15th century, while the name of Raphael, to whom the drawing was donated in the past, as it was inventoried by the Antaldi family, appears in the lower left inscription (“R.[aphael] V[rbinas]”). Comparisons include Viti’s sketch of the Miracle of the Demonic Cow, pen and brown ink, 26.5 x 40.9 cm, inv. n.1458, Albertina, Vienna; in which the male nude on the left of the composition undeniably echoes our study of women; as well as the Study for a Crucifixion , circa 1504-1509, pen and brown ink, 31.9 x 21.1 cm, Inv. MTC 5051, provenance: Comte Etienne-Marie de Saint Genys (1856-1915); Saint-Genys bequest to the City of Angers, February 1917, Angers Museum (opposite). It was to Viti that Philip Pouncey rendered this striking variation on the theme of the Crucifixion in 1977-1978, which dates from the period when the artist collaborated with Genga. The style of our sketch is close to the male nudes at the foot of the Thief’s cross on the left, in which we find the systematic use of small parallel hatching to suggest shadows. Other analogies with the artist’s style can also be found in two studies of nudes located at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, Paris: Standing male nude, black chalk, 34,3 x 14,2 cm, N° 433 and Study of a female nude, standing, seen from behind, and Study of a man seen in profile, black chalk, 32,4 x 19 cm, N° 432.

of the artists, R.V. for Raphael (Lugt L.2246), GGV for Girolamo Genga and TVV for Timoteo Viti, the last V standing for Urbino where from the three artists originated. The Viti collection countained a number of drawings by Viti copying drawings by Raphael. The Marquis Antaldi descended from the painter Timoteo della Vite, Raphael’s master, friend, and later imitator. Timoteo della Vite thus obtained or inherited the most important group of Raphael’s studio drawings, perhaps the finest ever brought together in a private collection. He probably got them when the master died. These drawings, or at least most of them, remained for a long time in the possession of the heirs of Timoteo Viti, the Antaldi family in Urbino. The collection was already fragmented in the 16th Century when Timoteo’s son sold some drawings to Vasari, but most of the drawings were dispersed in 1714, when Crozat bought a portion of the collection, and in 1828 when the rest was sold to Samuel Woodburn. The Viti collection contained a number of drawings by Viti copying drawings by Raphael. The initials of Raphael were stamped to the drawings long after Timoteo, probably in the 17th century, by a member of the Antaldi family, who was certainly not a great connoisseur, for the mark was too liberally used and relies on a number of drawings by students, imitators and copyists such as Timoteo himself. This stamp does not therefore give the guarantee of authenticity of the said attributions that we have often wanted to recognize, it is a testimony of age and an indication of provenance. Drawings have often been disputed between the two artists in the past.

Trained in the late 1490s in the Bolognese workshop of Francesco Francia, Viti was greatly influenced by the stylized ornamental manner of Giovanni Santi, Urbino’s leading painter during his youth. Viti and Raphael, son of Giovanni Santi, worked together in 1508-10 on the fresco decoration of the Chigi Chapel in S. Maria della Pace, Rome. It has been suggested that he is depicted (like the ancient Greek painter Protogenes) in The School of Athens, Raphael’s most famous work, standing next to Raphael’s self-portrait, although Vasari does not mention this identification. Raphael’s mature style influenced him for a time afterwards, as can be seen in the large altarpiece depicting Noli me Tangere and in our study as well.

This drawing was owned by Timoteo Viti, who worked with Raphael, and survived him by three years. Probably after the death of the artist Viti assembled a large number of drawings by Raphael. These drawings were marked in the 17th Century by a descendent of Viti, often inacurately, with the initials

He played a dominant role in the Urbino art scene for nearly three decades. A skillful draughtsman and painter, Viti was a vector in the diffusion of the artistic vocabulary of the manner of Perugino and Francia in the regions of central Italy.

23

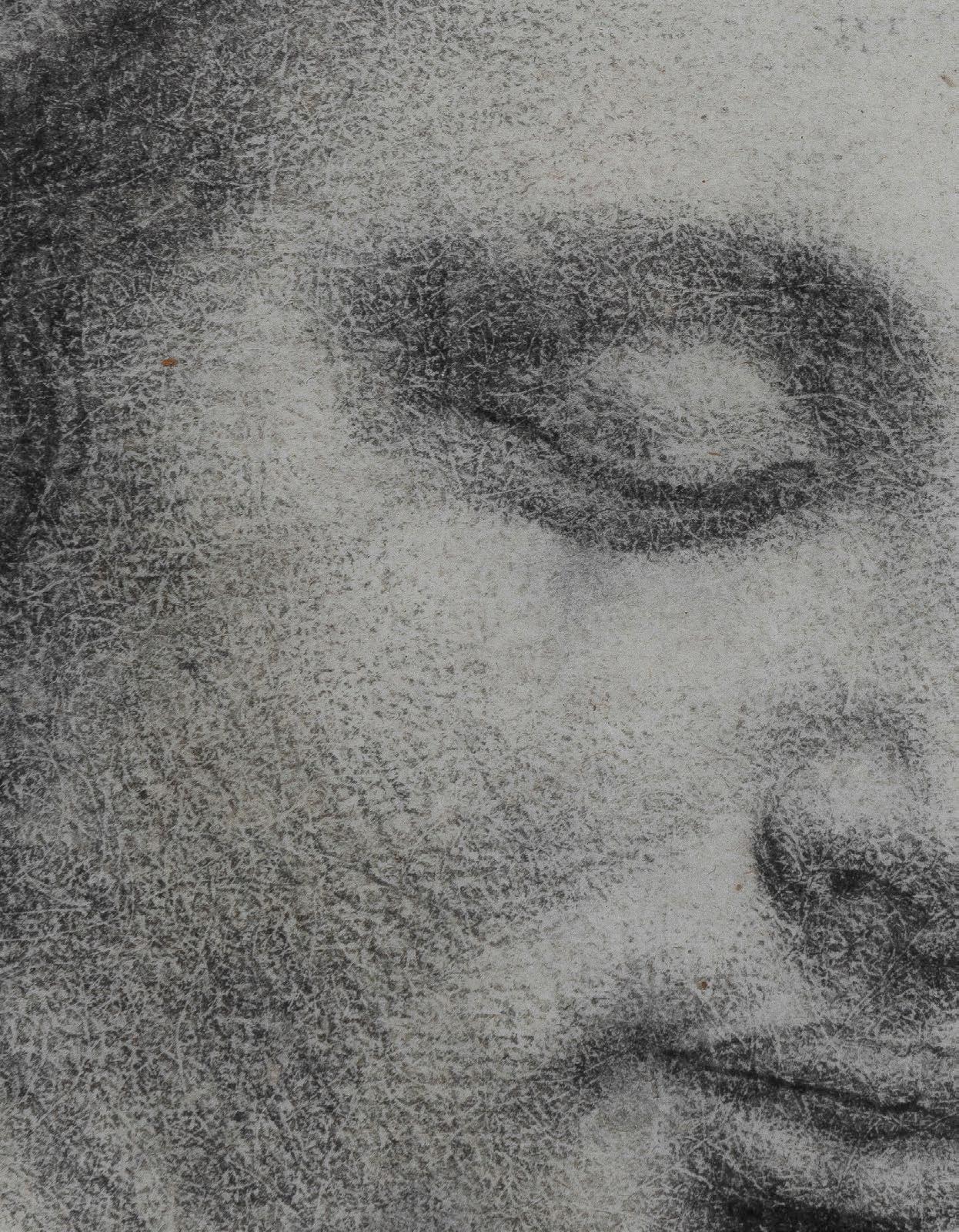

Attribué à Giuliano di Piero di Simone Bugiardini

(Florence 1475 - 1554)

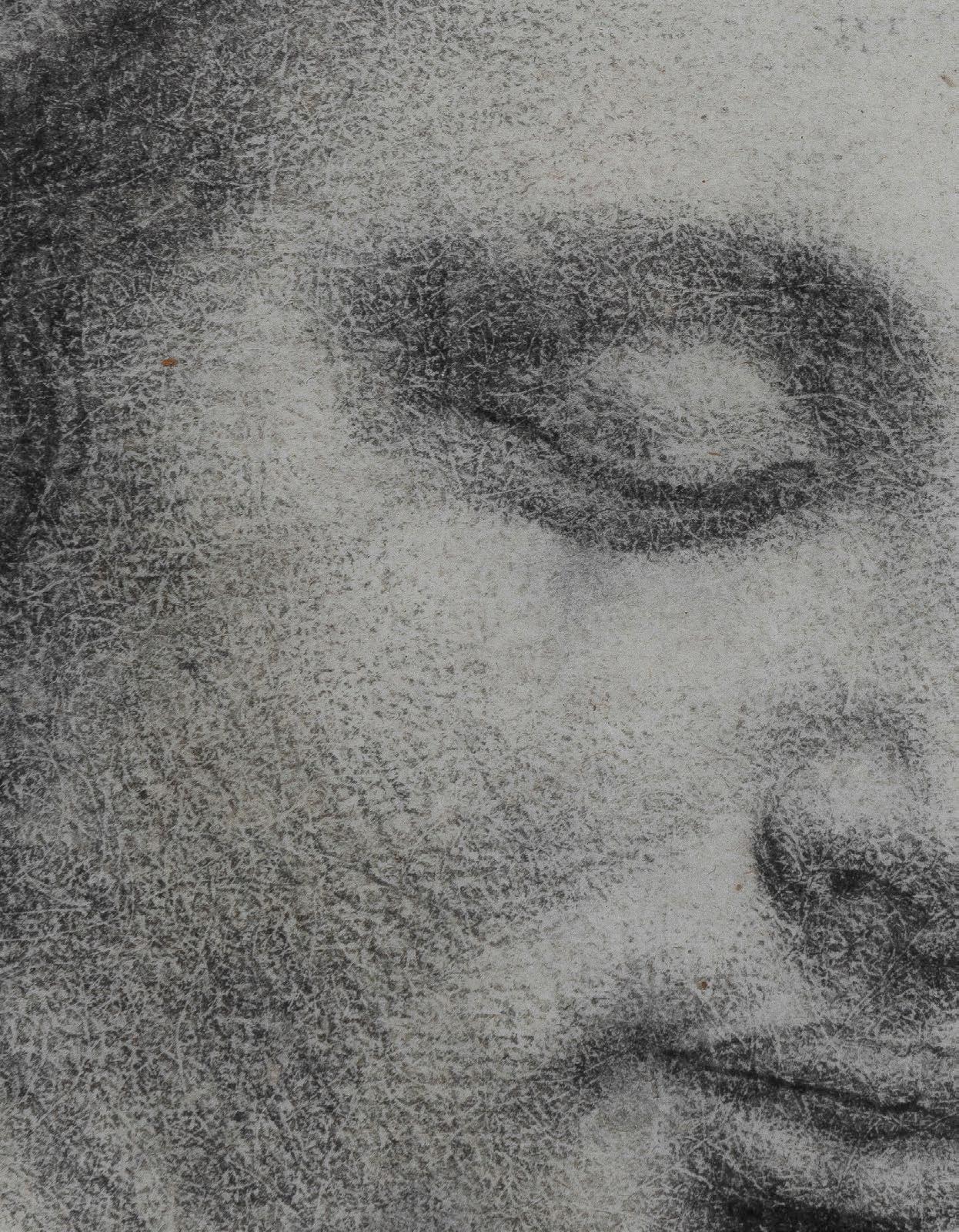

Étude de tête de femme, légèrement tournée et penchée vers la droite, les yeux baissés Study of a woman’s head, slightly turned and leaning to the right, eyes lowered

Pierre noire 12 x 13,5 cm

Provenance :

• Collection particulière, France.

black chalk 12 x 13.5cm

Provenance:

• Private collection, France.

24 04 |

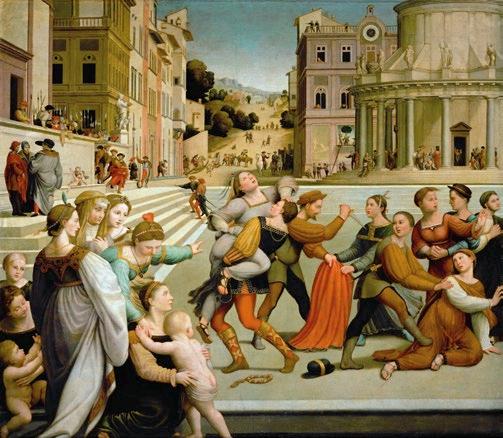

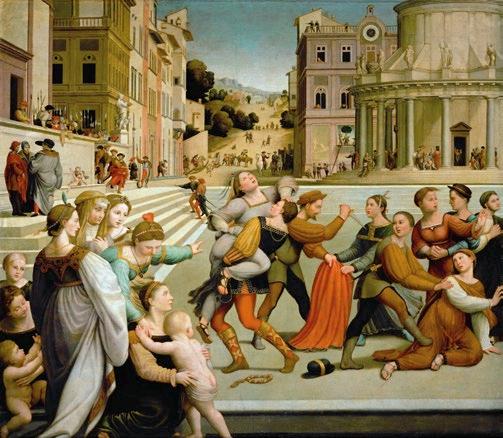

Œuvre en rapport :

Probablement, Giulio Bugiardini, Le Viol de Dinah, vers 1535, huile sur toile, 159,5 x 183 cm,

INV. NR. Gemäldegalerie 1554, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie.

Related work:

Probably, Giulio Bugiardini, The Rape of Dinah, around 1535, oil on canvas, 159,5 x 183 cm,

INV. NR. Gemäldegalerie 1554, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Gemäldegalerie.

Cette feuille semble se rattacher à une oeuvre de Bugiardini conservée au Kunsthistorisches Museum de Vienne, Le Viol de Dinah , et semble être une esquisse préparatoire à la figure à l’extrême gauche du tableau. Cette dernière a la tête légèrement tournée et penchée vers la droite, et porte une simple coiffe comme notre modèle. Seuls diffèrent les yeux qui ne sont plus baissés.

De même le style ainsi que la pureté des formes et des lignes sont tout à fait caractéristiques de sa personnalité artistique. Notre tête de femme est une réminiscence de celles de Fra Bartolommeo, dont la manière a fortement influencé l’œuvre de Bugiardini, tout comme celles d’Andrea del Sarto. Probablement dessinée d’après nature et caractérisée par une utilisation plus vive et moins contrôlée de la pierre noire, notre étude peut être comparée aux portraits peints par l’artiste.

26

27

La sensualité de la bouche charnue comme les joues pleines évoque en effet ses portraits. Le canon physique du modèle correspond exactement à ce que l’on relève à de multiples reprises dans le catalogue du peintre, Giuliano Bugiardi , de Laura Pagnotta : citons le Portrait de femme, huile sur toile, 57,8 x 49,6 cm, Inv. 1939.1.31, Washington, National Gallery of Art. Notre étude à la pierre noire est typique dans sa morphologie du visage « à la Burgiardini ». Les deux figures qu’il a exécutées dans la même technique de pierre noire, seuls dessins admis par Laura Pagnotta et reproduits au catalogue, révèlent, comme notre étude de tête, des contours fermes, soulignés par un trait marqué et repassé : Vierge à l’Enfant , pierre noire sur papier préparé rose foncé, 31,8 x 22,7 cm, Florence, aux Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, n. 14562F ; et Vierge à l’Enfant, pierre noire rehaussée de blanc sur papier teinté, 22,2 x 15,6 cm, Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, n. 5549. Les visages de Bugiardini sont moins idéalisés que ceux des œuvres de ses contemporains florentins et s’apparentent davantage à des figures de la vie quotidienne qu’à des sujets sacrés. Cette tête de femme est typique de son style, avec ses contours au menton et les hachures dans les cheveux. Le modelé et le traitement du volume est très fort ainsi que la force de l’expression.

Les dessins de Bugiardini sont d’une grande rareté ; la majorité des dessins qui lui était autrefois attribuée, a été récemment remise en question. Son corpus est particulièrement restreint.

Originaire de Florence, Bugiardini s’est formé dans l’atelier de Domenico Ghirlandaio, bien que très tôt les travaux de Fra Bartolommeo et de Mariotto Albertinelli l’ont également influencé de manière significative. Selon Vasari, Bugiardini faisait partie des artistes qui accompagnèrent Michel-Ange à Rome en 1508 pour l’assister dans la peinture de la Chapelle Sixtine (en plus de travailler ensemble sous Ghirlandaio, les deux semblent également avoir étudié ensemble la sculpture antique dans le Jardin Médicis) . Plusieurs compositions de Bugiardini révèlent sa profonde appréciation du sens de l’harmonie et de la spiritualité rationnelle de Raphaël.

En 1525 il se rendit à Bologne, où il exécuta quelques-unes de ses œuvres majeures, comme Le Mariage mystique de sainte Catherine pour la chapelle Albergati à Saint-François (Pinacothèque nationale (Bologne).

À Florence, dans les années 1530, il termina après une longue élaboration Le Martyre de sainte Catherine , commandé par Palla Rucellai pour Santa Maria Novella. Admis à la célèbre Accademia dei Giardini Medicei de San Marco à Florence, il devient ami et disciple de Michel-Ange, dont il peignit le portrait en 1523-1525 pour Ottaviano de Médicis.

28

This sheet seems to relate to a work by Bugiardini in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, The Rape of Dinah, and seems to be a preparatory sketch for the figure on the far left of the painting. The latter has her head slightly turned and tilted to the right, and wears a simple headdress like our model. Only the eyes differ, which are no longer lowered.

Similarly, the style and the purity of forms and lines are entirely characteristic of his artistic personality. Our female head is reminiscent of those of Fra Bartolommeo, whose style strongly influenced Bugiardini’s work, as well as those of Andrea del Sarto. Probably drawn from life and characterized by a more lively and less controlled use of black chalk, our study can be compared to the portraits painted by the artist.

The sensuality of the fleshy mouth like the full cheeks indeed evokes his portraits. The physical canon of the sitter corresponds exactly to what is noted on many occasions in the catalog of the painter, Giuliano Bugiardi, by Laura Pagnotta: for instance the Portrait of a woman, oil on canvas, 57,8 x 49,6 cm, Inv. 1939.1.31, Washington, National Gallery of Art. Our black chalk study is typical in its “Burgiardini” facial morphology. The two figures in black chalk, the only drawings admitted by Laura Pagnotta and reproduced in the catalogue, reveal, like our study of the head, firm outlines, underlined by an ironed line: Virgin with the Child, black chalk on dark pink prepared paper, 31,8 x 22,7 cm, Florence, at the Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, n. 14562F; and Virgin and Child, black chalk heightened with white on tinted paper, 22,2 x 15,6 cm, Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, n. 5549. The Bugiardini faces are less idealized than those of the works of his Florentine contemporaries and are more akin to figures of everyday life than to sacred subjects. This head of woman is typical of his style, with its outlines at the chin and the hatching in the hair. The modeling and treatment of volume is very strong as well as the force of the expression. Bugiardini’s drawings are extremely rare; the majority of drawings once attributed to him have recently been questioned. Its corpus is particularly limited.

A native of Florence, Bugiardini trained in the studio of Domenico Ghirlandaio, although early on the work of Fra Bartolommeo and Mariotto Albertinelli also influenced him significantly. According to Vasari, Bugiardini was among the artists who accompanied Michelangelo to Rome in 1508 to assist him in painting the Sistine Chapel (in addition to working together under Ghirlandaio, the two also appear to have studied ancient sculpture together in the Garden Medici). Several of Bugiardini’s compositions reveal his deep appreciation of Raphael’s sense of harmony and rational spirituality.

In 1525 he went to Bologna, where he executed some of his major works, such as The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine for the Albergati Chapel in Saint Francis (National Art Gallery (Bologna).

In Florence, in the 1530s, he finished The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, commissioned by Palla Rucellai for Santa Maria Novella: according to Vasari, Michelangelo designed most of the figures in this large Martyrdom. He joined the famous Accademia dei Giardini Medicei of San Marco in Florence, and became a friend and disciple of Michelangelo, whose portrait he painted in 1523-1525 for Ottaviano de Medici.

29

05 |

Bartolomeo Passarotti

ou Passerotti

(Bologne 1529 – 1592)

Étude de tête de femme Study of woman head

Plume et encre brune, pierre noire sur papier

32 x 22,5 cm

Provenance :

• Collection particulière.

Pen and brown ink, black chalk on paper

32 x 22,5 cm

Provenance:

• Private collection.

30

Récente redécouverte, notre feuille est stylistiquement caractéristique de la manière de Passerotti, dont la paternité a été confirmée par le Dr Corinna Höper, conservatrice à la Staatsgalerie Stuttgart et spécialiste de Bartolomeo Passarotti, sur la base de photographies (Communication en date du 21 Décembre 2022). Elle précise que les hachures croisées sont parfaitement convaincantes ; alors que le visage et les yeux de notre étude de tête sont typiques de l’artiste.

Auteur du catalogue raisonné des œuvres de Bartolomeo Passarotti (1529-1592), le Dr Corinna Höper fait référence à la Tête de jeune homme , plume et encre brune, pierre noire sur papier, vers 1583/1584, 42,4 x 27,4 cm, Collections : Jabach, Everhard - Cabinet du Roi, INV 8487, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

Passarotti utilisait principalement la plume et l’encre brune, celles-ci apparaissant comme sa technique de prédilection. Obtenant le volume et le modelé à l’aide de fines et soigneuses hachures parallèles ou croisées, l’artiste fait montre d’une rare maîtrise. Dans notre étude, la délicatesse du traitement des lèvres et du nez, l’application subtile des contours et des hachures pour un modelé raffiné en font l’un des exemples les plus touchants parmi ces études de têtes.

Il se montrait réaliste dans la représentation de ses modèles, obtenant un effet sculptural par de savants jeux de hachures. Réputé comme portraitiste, il était très demandé par la noblesse, friande de portraits afin d’orner les murs de ses palais dans la seconde moitié du XVIe siècle.

Son biographe Malvasia a insisté sur la maîtrise de Passarotti à la fois en tant que dessinateur et graveur, tout en soulignant la renommée et l’admiration qu’il a acquises auprès des collectionneurs, renommée qui doit être basée dans une large mesure sur des œuvres telles que notre élégant dessin, certainement réalisé comme une œuvre d’art indépendante à part entière.

Notre dessin, charmant et vigoureux, très probablement réalisé d’après nature, pourrait bien avoir été exécuté entre le milieu et la fin des années 1550, pendant la deuxième période romaine de l’artiste, lorsqu’il travaillait avec Taddeo Zuccari. Une influence romaine, plus particulièrement celle de Raphaël, est perceptible dans l’élégance et la solennité de cette étude de tête de femme.

Passarotti avait d’abord travaillé à Rome en 1550-1555, s’alliant avec le célèbre architecte Jacopo Vignola (1507-1573). À la mort du pape Jules III, cependant, il retourna à Bologne et, en 1560, il y avait établi sa propre bottega, mais il semble être retourné travailler à Rome à divers moments au cours des années 1550 et par la suite. Il y a cependant peu de documents sur ses mouvements ou ses œuvres qui peuvent être solidement liées aux expériences romaines de l’artiste, ce qui rend très difficile d’évaluer l’impact réel de la Ville éternelle sur son style. Néanmoins, il semble que son travail de graveur - qui a joué un rôle important dans sa vie artistique - trouve son origine dans son séjour à Rome à la fin des années 1550. La subtilité et la monumentalité de notre feuille témoignent de ces expériences et influences romaines, qui ont abouti à un ductus légèrement plus libre que dans certaines œuvres antérieures.

Nous sommes reconnaissants au Dr. Corinna Höper pour les informations qu’elle nous a aimablement communiquées et qui ont aidé à l’élaboration de cette notice.

32

33

The present sheet is stylistically typical of Passerotti and a very recent discovery, and its authorship has been confirmed by Dr. Corinna Höper, curator at the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart and expert on Bartolomeo Passarotti’s works, on basis of photographs (Communication of Dr. Corinna Höper dated 21 December 2022). She noticed that especially the cross hatching is convincing (compare p.e. the « Head of a youth » in the Louvre, Inv. 8487) and that the type of the face and the eyes are also typical Passarotti.

Author of the catalogue raisonné on Bartolomeo Passarotti (1529-1592) (Corinna Höper, Bartolomeo Passarotti (1529-1592 ), 2 vol., Worms, 1987), Dr. Corinna Höper refers to the Head of a youth , pen and brown ink, black chalk on paper, circa 1583/1584, 42,4 x 27,4 cm, Collections : Jabach, EverhardCabinet du Roi, INV 8487, Louvre Museum, Paris. Traditionally given to Bartolomeo Passerotti, this drawing has been linked by C. Höper (1987) with the young figure in the lower right foreground of the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, painted by the artist between 1583 and 1584 for the chapel of the Antica Dogana, Bologna (now in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, inv. 481; reprinted in A. Ghirardi, 1990, pl. XXVI).

This characteristically charming and vigorous drawing by Passarotti, very likely made from life, may well have been executed in the mid to late 1550s, during the artist’s second Roman period, when he was working together with Taddeo Zuccari. A Roman influence is certainly detectable in the elegance and solemnity of this study of woman head, which may have been drawn from life.

Passarotti principally uses pen and brown ink and he is being realistic in his representation of people, achieving a sculptural effect. The technique is typical for the artist in its use of sharply defined crosshatching, clear and undulating outlining, and a selective us of thicker lines for emphasis at certain points along the outlines and in a few interior passages. Passerotti was well- known as a portrait painter and his work was much in demand, as portraits were a characteristic type of decoration of aristocratic palaces in the second half of the sixteenth century.

The early biographer Malvasia insisted on Passarotti’s skill both as a draughtsman and as an engraver, and highlighted the fame and admiration he achieved with collectors, fame that must have been based to a considerable extent on works such as the present elegant drawing, surely made as an independent work of art in its own right.

Passarotti had first worked in Rome in 1550-1555, allying himself with the famous architect Jacopo Vignola (1507-1573). On the death of Pope Julius III, however, he returned to Bologna and by 1560 he had established his own bottega there, but he seems to have returned to work in Rome at various times during the 1550s and thereafter. There is, however, little documentation of his movements or works that can be firmly linked to the artist’s Roman experiences, making it very difficult to assess the actual impact of the Eternal City on his style. Nevertheless, it seems that his work as an engraver - which played an important role in his artistic lifehad its origins in his stay in Rome at the end of the 1550s. The subtlety and monumentality of our sheet testify to these experiences and influences. Romans, which resulted in a slightly freer ductus than in some earlier works.

Outstanding example of Bartolomeo Passarotti’s draughtsmanship, this large drawing demonstrates the artist’s characteristic use of strong contours and hatching.

We are grateful to Dr. Corinna Höper for the information she kindly shared with us that helped in the production of this entry.

35

Benedetto Caliari

(Vérone 1538 - 1598 Venise)

Portrait de femme

Portrait of woman

Plume et encre brune, lavis d’encres brunes et rehauts de gouache blanche, sur papier préparé brun 22,4 x 30 cm

Provenance :

• Collection particulière, France.

Pen and brown ink, brown wash heightened with white on brown-prepared paper 22,4 x 30 cm

Provenance:

• Private collection, France.

36 06 |

Les feuilles en chiaroscuro (en clair-obscur ou en grisaille) occupent une place prépondérante dans l’oeuvre dessiné de Benedetto Caliari, frère cadet de Paolo Caliari dit Véronèse. Ce délicieux portrait de femme en chiaroscuro, inédit jusqu’à présent, fait l’objet d’un traitement particulièrement précis et soigné.

Benedetto a repris la manière des chiaroscuro à son frère ainé : l’image est construite au moyen de valeurs claires (le plus souvent des rehauts de blanc), qui se détachent sur un fond préparé dans une tonalité sombre. Véronèse n’en est certes pas l’inventeur, d’autres artistes, tant italiens que nordiques en ont exploré les qualités picturales - mais les quelques trente feuilles de sa main réalisées dans cette technique ont de tout temps éveillé l’admiration des amateurs, notamment en raison de leur aspect délicat et fini. Ce sont les seuls mentionnés par son premier biographe Ridolfi en 1648. L’enthousiasme de Ridolfi est compréhensible, car ils ont été conçus comme des œuvres indépendantes. Véronèse s’est ici tourné vers une tradition plus ancienne du dessin vénitien avec un sens de l’invention dans des sujets conventionnels, à la fois religieux et allégoriques et dans des variations inhabituelles sur des thèmes bien établis.

Plusieurs questions restent cependant ouvertes à propos de leur fonction par le maître : David Rosand (Véronèse, Citadelles 2012) estime qu’il s’agit le plus souvent de modelli , ultime étape de la préparation d’une oeuvre peinte, pouvant être utilisés comme dessins de présentation à un commanditaire potentiel, ou encore de ricordi, à savoir des feuilles destinées à conserver la mémoire d’une invention. Richard Cocke, auteur de Veronese’s drawings, a catalogue raisonné, Sotheby Publications, rejetant l’idée de modelli, qu’ils soient de présentation ou qu’ils correspondent à un stade final d’élaboration d’une composition, penche pour des œuvres indépendantes. La datation des chiaroscuri de Véronèse n’est pas non plus sans poser

problème : pour W.R. Rearick (The Art of Paolo Veronese 1528-1588, Cambridge University Press, 1988) dès le milieu des années 1540 et jusqu’à la fin de sa carrière, ou au contraire pour Cocke, dans une période restreinte entre 1550 et 1560. Au delà des discordes de datations, Benedetto fit sienne cette technique. De la série d’allégories féminines que Paolo Veronese dessina a chiaoscuro, il reste six feuilles à Francfort (Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Inv. 457), Vienne (Albertina, Inv. 1636 et 1640), Paris (Louvre, RF 600), Norfolk (Holkham Hall, coll. Leicester; Cocke, 1984, n°17, 22-23, 39-40) et à Zurich (coll. DenckerWinckler (Cocke, 1988, pl. 19 ; Rearick, 1988, n° 30). Une septième, au Louvre (Inv. 4682) doit sans doute être considérée comme une copie d’un dessin perdu.

Benedetto réalisa d’ailleurs trois copies sur papier bleu conservées au Louvre de la Fortuna de Paolo : L’Allégorie de la Richesse, Inv. RF 41299, plume et encre brune, lavis brun, rehauts de blanc sur papier bleu, 30 x 20 cm ; La Fortune Maritime, Inv. RF 41300, plume et encre brune, lavis brun, rehauts de blanc sur papier bleu, 30 x 21 cm, annoté en bas à gauche, à la plume : « da Paolo » ; La Fortune Terrestre, Inv. RF 41301, plume et encre brune, lavis brun, rehauts de blanc sur papier bleu, 30 x 20 cm, annoté en bas à gauche, à la plume : « da Paolo ».Tracées à l’encre brune, ces figures monumentales de Fortuna sont largement reprises de petits traits serrés de gauche blanche, des rehauts qui contrastent avec les éléments d’architecture esquissés dans le fond pour produire l’effet chromatique caractéristique des chiaroscuri. L’annotation ancienne « da Paolo » portée sur deux feuilles signifie justement qu’il s’agit de dessins d’après Paolo. Elles renvoient stylistiquement et techniquement à notre portrait.

38

39

La qualité de notre feuille et la technique particulière, de stricte obédience véronésienne, révèlent qu’il s’agit de l’œuvre d’un artiste proche de Véronèse, son propre frère cadet et collaborateur Benedetto Caliari. Elle est exécutée avec un éclat et une fluidité dans les rehauts de blanc. Le sens du volume et les spécificités physiques telles que la dysmorphie des mains, qui contraste avec le petit visage, sont propres à Benedetto. L’utilisation méticuleuse des rehauts de gouache blanche permet à l’artiste de définir les soieries et perles comme de suggérer avec délicatesse la lumière qui illumine le visage du modèle. Ce dernier appartient aux personnages courtois représentés dans des vêtements et des bijoux luxueux et contemporains caractéristiques de Véronèse.

Sa comparaison avec deux dessins conservés au Musée de Grenoble, à la plume et encre brune, lavis brun, rehauts de blanc sur papier brun, provenant du legs de M. Léonce Mesnard en 1890, entré au musée en 1902, apporte un argument supplémentaire à son attribution à Benedetto Caliari : Tête de Femme 10 x 7 cm ; et Tête de Jeune Fille , 9,9 x 6,9 cm. Leurs coiffures et leurs caractéristiques faciales ressemblent à celles de notre modèle ; de même l’exécution est comparable.

Dernier élément de comparaison est l’oeuvre peint de Benedetto du même style que notre feuille. Citons pour exemple, La découverte de Moïse de Benedetto Caliari, inscrit avec le numéro d’inventaire en bas à gauche : « 59 » , huile sur toile, 148 x 239,5 cm, provenance: collection particulière, Allemagne, vers 1830-1840, ayant été acquise en Europe du Sud ou en Allemagne ; puis par descendance jusqu’à la vente anonyme (« Property of a Nobleman »), Londres, Christie’s, 7 juillet 2017, lot 115, où acquis ; Londres, Sotheby’s 28 Avril 202, lot 316.

Benedetto Caliari était le frère cadet de Paolo Caliari, plus connu sous le nom de Paolo Veronese. En 1556, à l’âge de 18 ans, Benedetto a été enregistré comme travaillant déjà dans l’atelier de son frère aîné, et il semble y être resté la majeure partie de sa carrière, reprenant la direction de l’atelier après la mort de Véronèse en 1588, en collaboration avec ses neveux Carlo et Gabriele, qui ont souvent signé des œuvres en collaboration sous le nom de « Haeredes Pauli » (« les héritiers de Paolo »).

41

The chiaroscuro drawings (in chiaroscuro or in grisaille) take a preponderant place in the drawn work of Benedetto Caliari, younger brother of Paolo Caliari known as Veronese. This charming portrait of a woman in chiaroscuro, unpublished until now, is careful rendering by the artist and displays an exacting finesse in the modeling of the face and details.

Benedetto took over the manner of chiaroscuro from his older brother: the image is composed using light values (most often white highlights), which stand out against a background prepared in a dark tone. Veronese is certainly not its inventor, other artists, both Italian and Nordic, have explored its pictorial qualities - but the thirty or so sheets by his hand produced in this technique have always aroused the admiration of amateurs, especially because of their delicate and finished appearance. They are the only ones mentioned by his first biographer Ridolfi in 1648. Ridolfi’s enthusiasm is understandable, for they were planned as independent works and executed with a brilliance and fluidity in the white heightening that was copied but never equalled. Veronese here turned to an older tradition of Venetian drawing with a sense of invention in conventional subjects, both religious and allegorical and in unusual variations on well-established themes.

However, several questions remain open about their function by the master: David Rosand ( Véronèse , Citadelles 2012) believes that it is most often a question of modelli , the final stage in the preparation of a painted work, which can be used as presentation drawings to a potential patron, or even ricordi , namely sheets intended to preserve the memory of an invention. Richard Cocke, author of Veronese’s drawings, a catalog raisonné , Sotheby Publications, rejecting the idea of modelli , whether they are of presentation or that they correspond to a final stage of elaboration of a composition, leans for independent works . The dating of Veronese’s chiaroscuri is not without its problems either: for W.R. Rearick (The Art of Paolo Veronese 1528-1588, Cambridge University Press, 1988) from the mid-1540s until the end of his career, or on the contrary for Cocke, in a restricted period between 1550 and 1560. Beyond the disagreements of dating,

Benedetto made this technique his own. Of the series of female allegories that Paolo Veronese drew a chiaoscuro, six sheets remain in Frankfurt (Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Inv. 457), Vienna (Albertina, Inv. 1636 and 1640), Paris (Louvre, RF 600), Norfolk Holkham Hall, coll. Leicester; Cocke, 1984, n°17, 22-23, 39-40) and in Zurich (Dencker-Winckler collection (Cocke, 1988, pl. 19; Rearick, 1988, n° 30). A seventh, at the Louvre (Inv . 4682) should probably be considered a copy of a lost drawing.

42

Benedetto also made three copies on blue paper of La Fortuna by Paolo, nowadays in the collection of the Louvre : The Allegory of Wealth, Inv. RF 41299, pen and brown ink, brown wash, white highlights on blue paper, 30 x 20 cm; La Fortune Maritime, Inv. RF 41300, pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white on blue paper, 30 x 21 cm, annotated lower left, in pen: “ da Paolo ”; La Fortune Terrestre , Inv. RF 41301, pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white on blue paper, 30 x 20 cm, annotated lower left, in pen: “da Paolo”. Drawn in brown ink, these monumental figures of Fortuna are largely taken up with small tight lines of white left, highlights that contrast with the architectural elements sketched in the background to produce the characteristic chromatic effect of chiaroscuri. The old annotation “da Paolo” on two sheets means that these are drawings after Paolo. They refer stylistically and technically to our portrait.

The quality of our sheet and the particular technique, of strict Veronese obedience, reveal that it is the work of an artist close to Veronese, his own younger brother and collaborator Benedetto Caliari. It is executed with brilliance and fluidity in the white highlights. The sense of volume and the physical specificities such as the dysmorphism of the hands, which contrasts with the small face, are specific to Benedetto. The meticulous use of white gouache highlights allows the artist to define the silks and pearls as well as to delicately suggest the light that illuminates the face of the model. The latter belongs to the courtly figures depicted in luxurious and contemporary clothing and jewelry characteristic of Veronese.

Additional supporting evidence in favor of Benedetto Cagliari’s authorship of this portrait is found in comparison with two drawings of the Museum of Grenoble, pen and brown ink, brown wash, heightened with white on brown paper, from the bequest of Mr. Léonce Mesnard in 1890, which entered the museum in 1902: Head of a Woman 10 x 7 cm; and Head of a Young Girl, 9,9 x 6,9 cm. Their hairstyles and facial features resemble those of our sitter; likewise the execution is comparable.

Last additional relevant comparison is the painted work of Benedetto in the same style as our sheet. For example, The Finding of Moses by Benedetto Caliari, inscribed with the inventory number at the bottom left: “59”, oil on canvas, 148 x 239,5 cm, provenance: private collection, Germany, circa 1830-1840, purchased in Southern Europe or Germany; then by descent to anonymous sale (“ Property of a Nobleman”), London, Christie’s, July 7, 2017, lot 115, where purchased; London, Sotheby’s April 28, 202, lot 316.

Benedetto Caliari was the younger brother of Paolo Caliari, better known as Paolo Veronese. In 1556, at the age of 18, Benedetto was recorded as already working in his elder brother’s workshop, and he seems to have remained there most of his career, taking over management of the workshop after Veronese’s death in 1588, together with his nephews Carlo and Gabriele, who often signed collaborative works under the name “Haeredes Pauli” ( “the heirs of Paolo »).

43

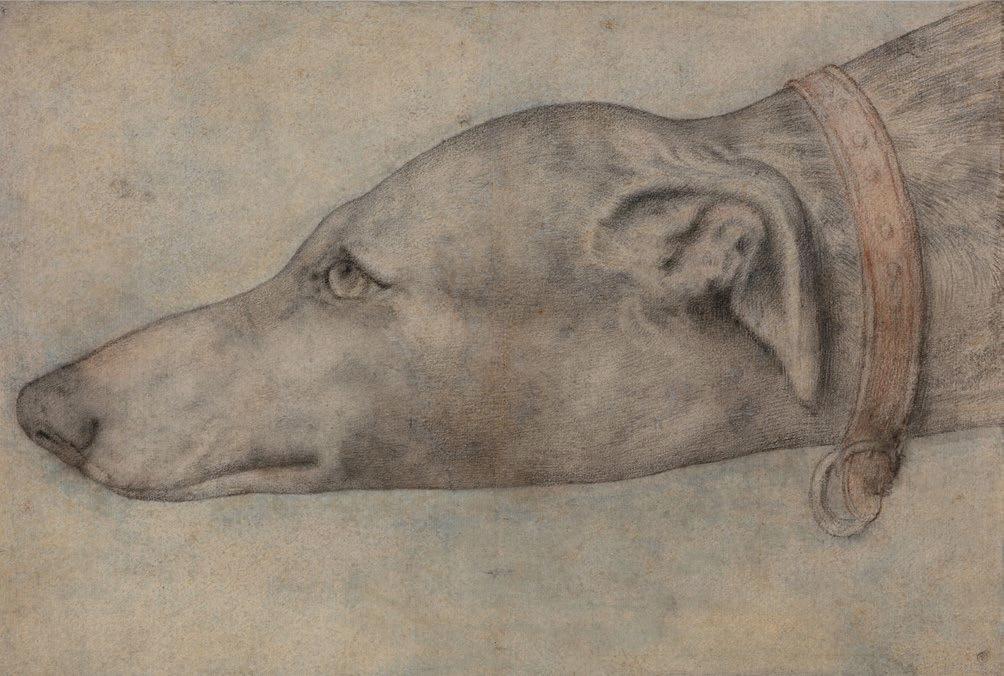

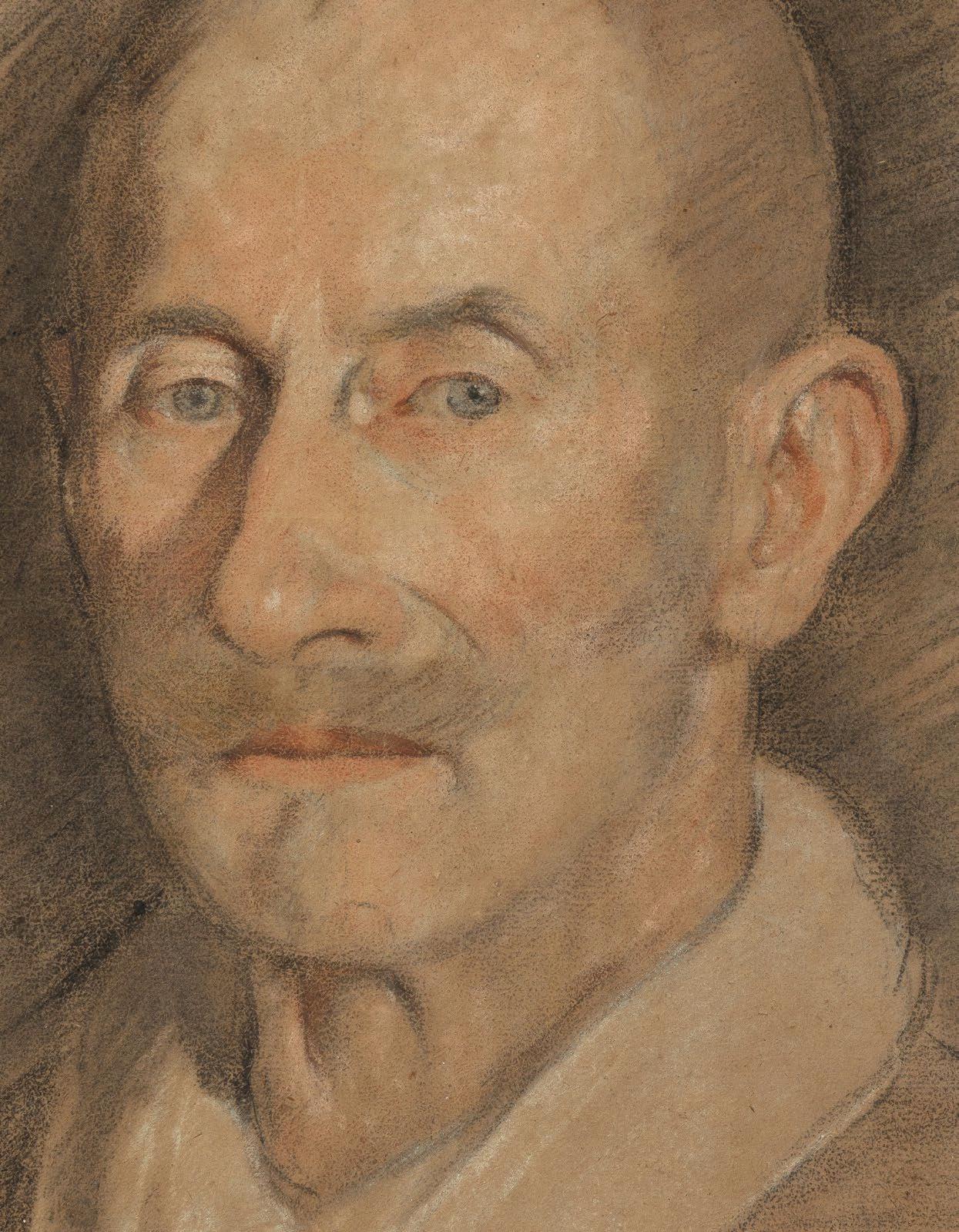

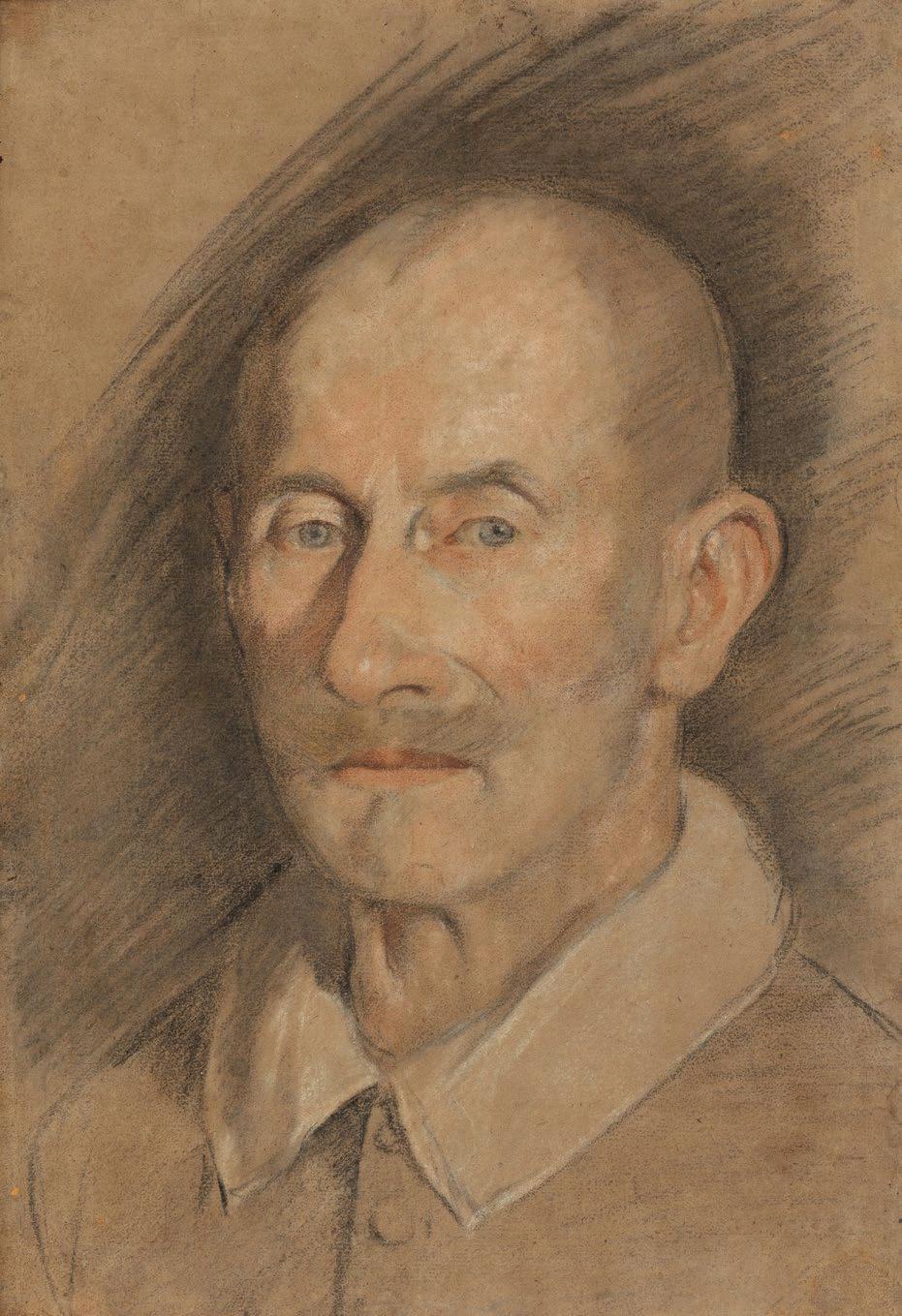

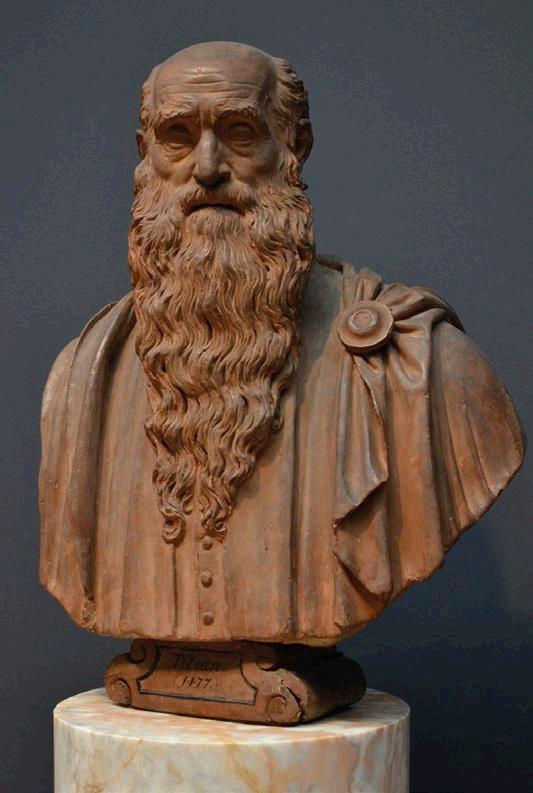

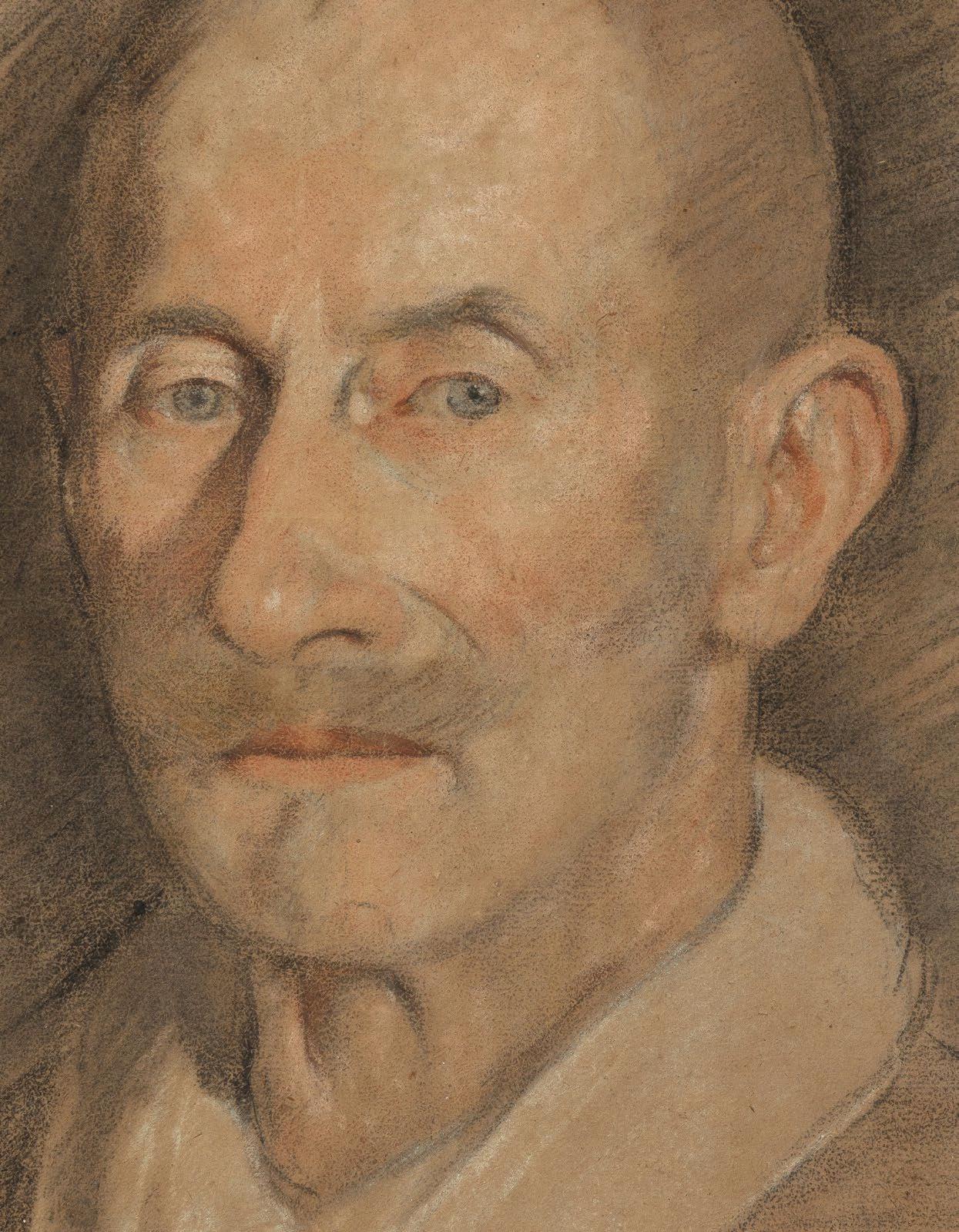

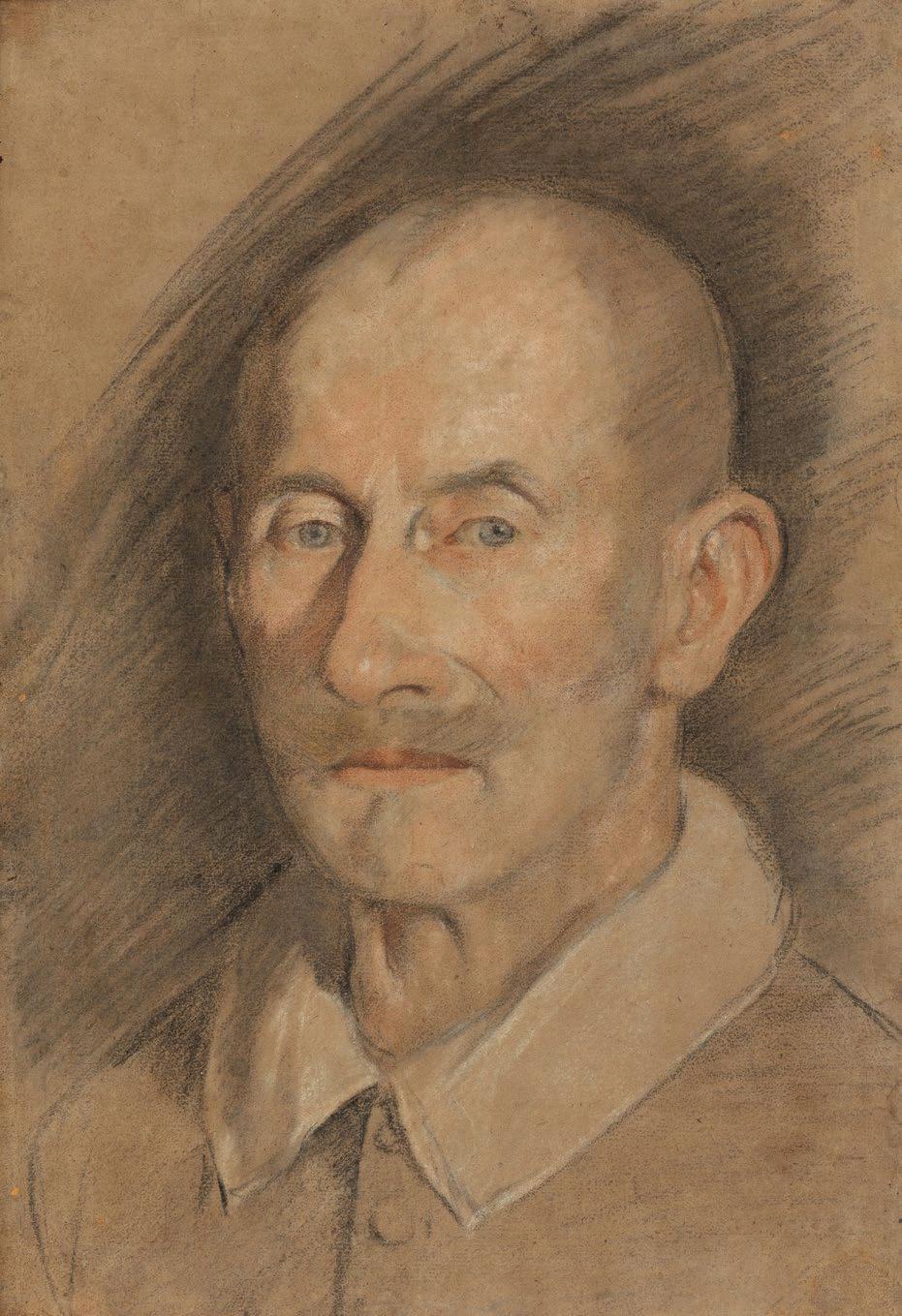

Federico Barocci

(Urbino

1526-35 - 1612)

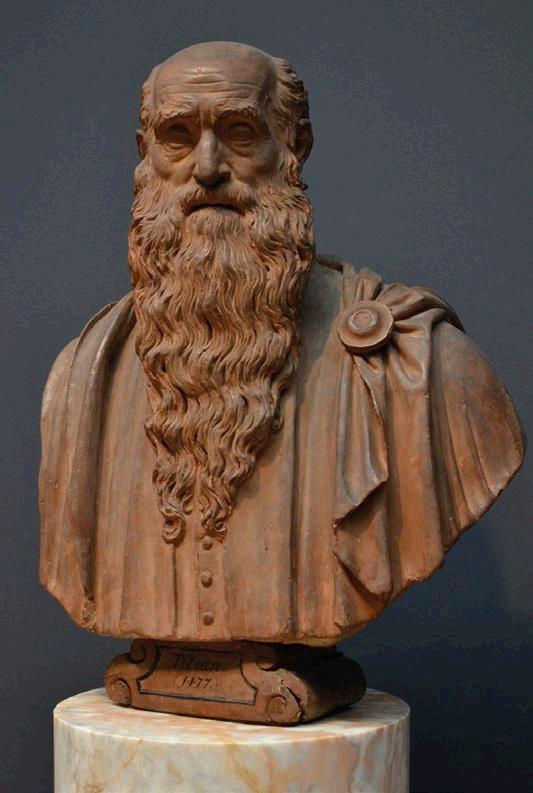

Étude d’homme barbu Study of bearded man

Pierre noire et sanguine, estompe, pastel rehaussé de blanc sur papier brun 39 x 27,5 cm

Porte une inscription à la plume et encre brune sur le montage « Federico Barocci »

Provenance :

• Collection particulière, France.

Bibliographie :

• Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800, J.127.203

Black and red chalk, stumping, pastel heightened with white on brown-prepared paper 39 x 27,5 cm

Bears an inscription in pen and brown ink « Federico Barocci »

Provenance:

• Private collection, France

Bibliography:

• Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800, J.127.203

44 07

|

Peintre célébré et recherché de son vivant, Federico Barocci fut également un dessinateur prolifique et admiré, notamment pour son emploi de la couleur, rarement utilisée par ses contemporains.

Selon Babette Bohn, environ mille cinq cents dessins sont aujourd’hui attribuables à Barocci (« Drawing as artistic invention : Federico Barocci and the Art of Design », Federico Barocci Renaissance Master of Color and Line, cat. expo. Saint Louis Art Museum, 2012, p. 33), tandis que Nicholas Turner en compte environ deux mille ( Federico Barocci, Paris, 2000, p. 150), ce qui en fait l’un des artistes les plus prolifiques de la Renaissance italienne : un nombre exceptionnel en matière de préservation de l’oeuvre graphique d’un artiste du XVIe siècle. Son processus créatif, très lent, était notoire ; il produisait de nombreux dessins qui lui servaient à préparer chacune des figures peuplant ses peintures, ainsi que des modelli plus finis.

Ne se limitant pas à l’utilisation d’une seule technique, Barocci associe souvent la pierre aux différents crayons de couleurs et pastels, en commençant toujours par esquisser à la pierre noire, comme dans notre dessin.

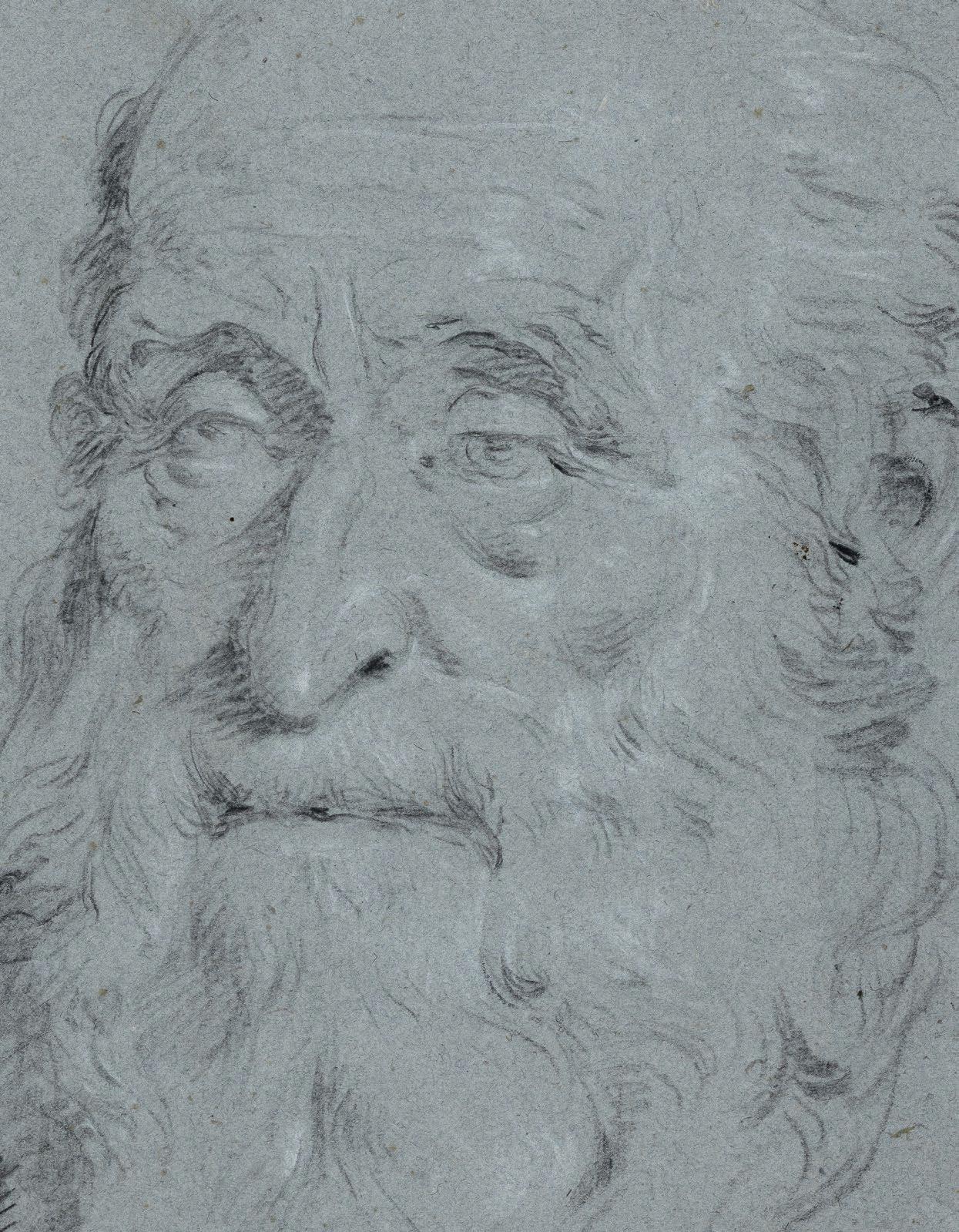

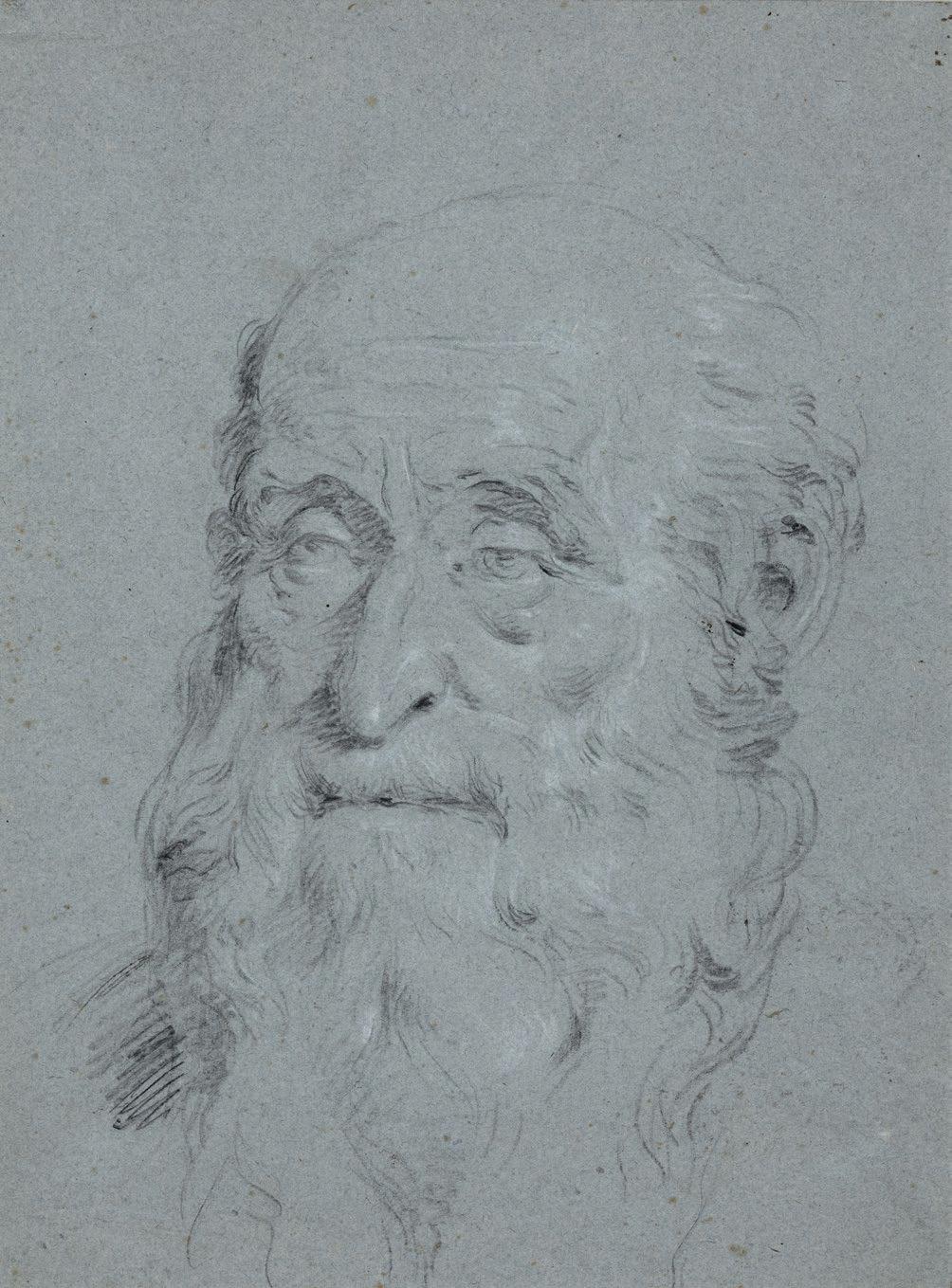

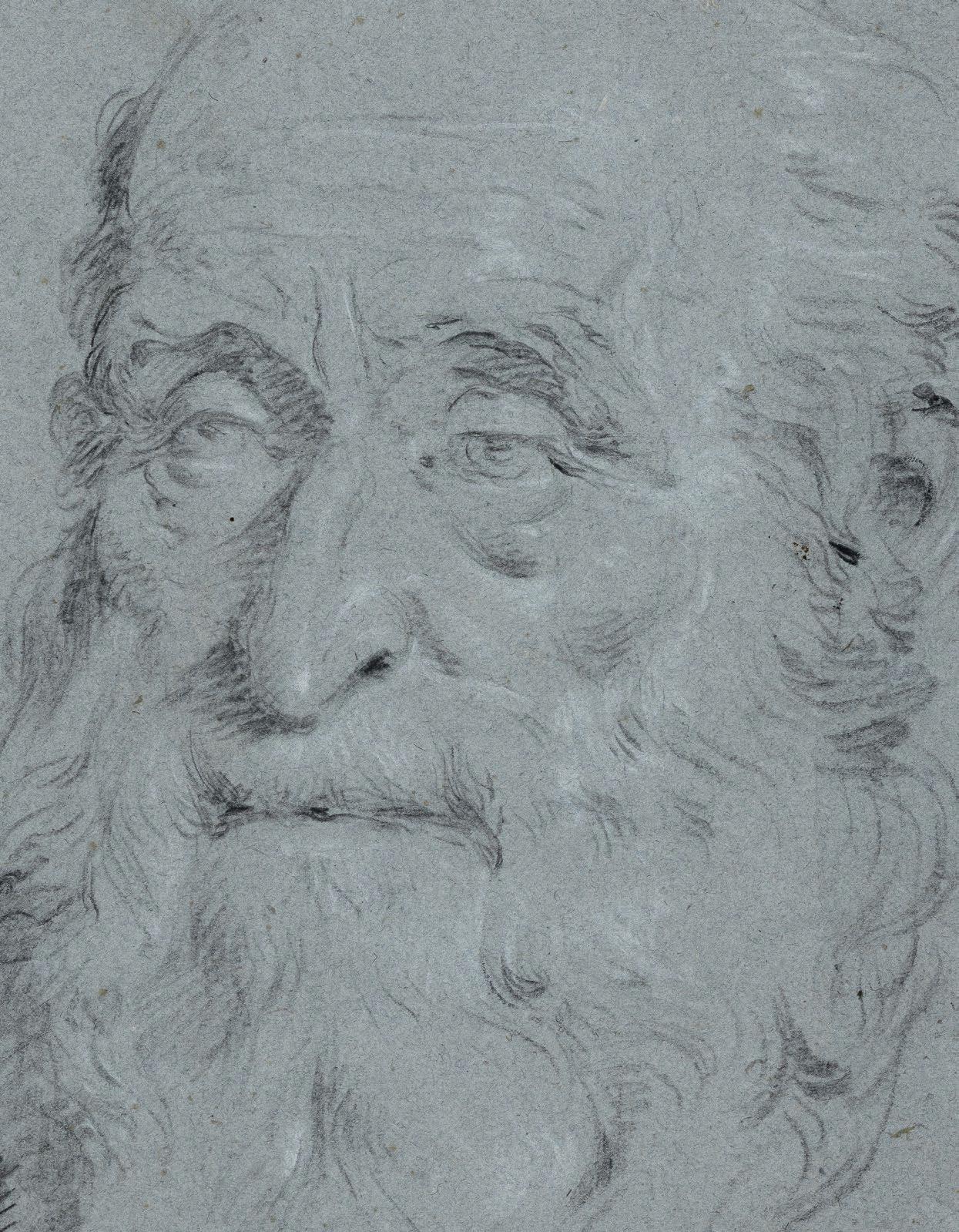

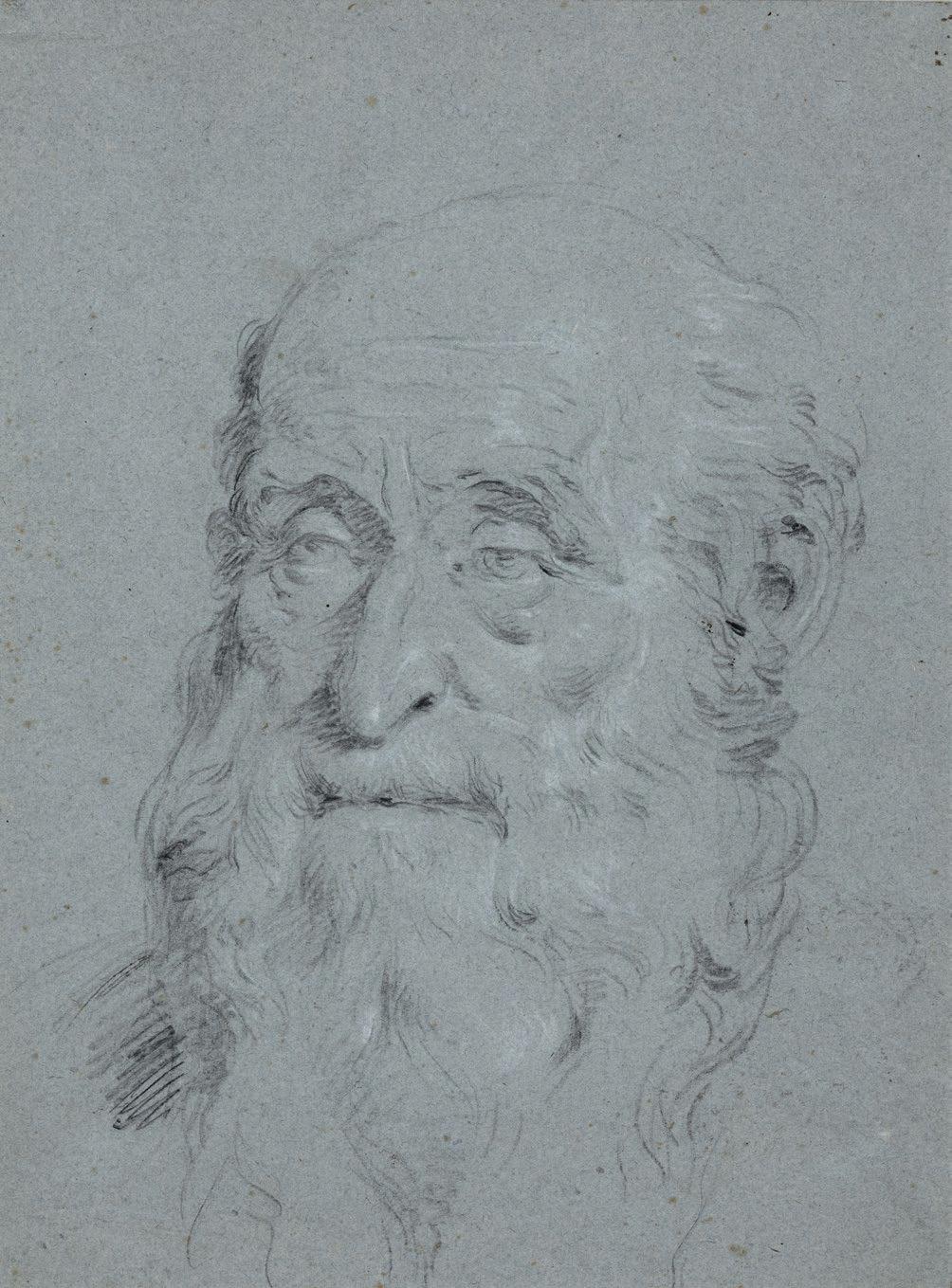

Notre feuille compte parmi ses études de figures qui font preuve d’un réalisme stupéfiant avec une esthétique mélancolique si caractéristique de l’artiste. Celle-ci ne semble pas correspondre toutefois à un tableau en particulier. La mise en page de notre étude rappelle également d’innombrables études de têtes de Barocci. Le visage occupe tout l’espace de la feuille, se détachant d’un fond rapidement esquissé à la pierre noire par de grandes hachures parallèles en oblique, comme dans un dessin conservé au musée du Louvre, représentant un Jeune homme nu penché en avant pour prendre un vase, pierre noire et sanguine rehaussées de blanc, pastel sur papier gris-vert, mis au carreau, 38,3 x 24,2 cm, collections : Saint-Morys, INV 2860.

Ce dessin concentre l’écriture graphique et les traits symptomatiques de la manière de Barocci : les yeux en amande au contour tracé à la pierre noire rehaussée de sanguine, des ombres obtenues par estompe ou de fines hachures de pierre noire. De même l’artiste fait souvent usage de sanguine estompée au niveau des paupières cernées de rouge, des oreilles et des lèvres, qui sont autant de nimbes rosés traitées en subtil sfumato comme la barbe et la moustache du modèle. Cette technique permet à Barocci de se concentrer sur les yeux. En pleine maîtrise ici de son art, Federico parvient à modeler avec raffinement le visage par des rehauts de craies blanches. Le Musée du Louvre conserve dans ses collections un parfait exemple : Tête de femme, de trois quarts et penchée vers la droite, les yeux baissés, pierre noire, sanguine, craie blanche et pastel, sur papier brun, 23,7 x 21,2 cm, collections : Conti, prince de - Mariette, Pierre-Jean - Crozat, Pierre (1665-1740)

- Desmarets - Saint-Morys, Charles-Paul-J.-B. de Bourgevin Vialart de (1743-1795) - Paillet, Alexandre Joseph (1743-1814) - Ménageot, Augustin, INV 2866. Enfin le traitement de la chevelure de notre étude renvoie à celle de la Tête de jeune garçon, aux cheveux rasés, de profil vers la droite, pierre noire et sanguine, pastel rehaussé de blanc sur papier gris, 33 x 24,7 cm, Collections : Cabinet du Roi, INV 2871, également conservé au Louvre. Ainsi dans les deux cas, l’artiste utilise le pastel en aplat ensuite estompé puis rehaussé de quelques fines hachures rapidement esquissées à la pierre noire, le crâne cerné d’un trait de contour.

Comme dans de nombreuses œuvres de l’artiste, notre dessin témoigne de son habilité à étudier et rendre la psychologie des personnages. Il capture ici le regard de cet homme perdu dans ses pensées avec une grande finesse psychologique. La théâtralité est soulignée par les couleurs et les effets de clair-obscur.

Federico Fiori naît comme le peintre Raphaël, à Urbino, dans une famille d’origine lombarde qui avait déjà produit plusieurs artistes distingués. Il se forme d’abord en étudiant les tableaux du génie de sa Ville ainsi que du Titien, puis prend plus tard, Daniele da Volterra, les Vénitiens et Corrège pour modèles. Sa manière vise à susciter la dévotion, à capter l’émotion du spectateur, ce qui était résolument nouveau. Appelé à Rome par Pie IV, il exécute pour ce pape plusieurs grands ouvrages de peinture au Casino du Belvédère (Histoire de Moïse, 1563).

46

47

Pendant son séjour à Rome, quelques peintres jaloux de ses succès tentent de l’empoisonner, alors qu’il n’a que 32 ans. Les soins qu’il reçoit aussitôt l’arrachent à la mort, mais sa santé en sera profondément altérée pour le reste de ses jours. Il vécut cependant encore longtemps et put produire d’autres chefs-d’œuvre. Il meurt à Urbino en 1612, à 84 ans.

Dans la région des Marches, sa lecture personnelle du maniérisme eut un succès immédiat. Dans les autres régions, en revanche, son art connut une diffusion plus lente. Ce sont des artistes plus jeunes d’une ou deux générations qui ont compris l’importance de la peinture du Baroche. Certains, comme Carrache et les peintres bolonais (Guido Reni notamment) en firent un pilier sur lequel ils élaborèrent leurs propres innovations.

Nous remercions Andrea Emiliani et Nicholas Turner d’avoir confirmé l’attribution à Barocci.

A well admired and highly sought-after and artist, Federico Barocci was a prolific draughtsman, especially for his use of colour, rarely used by his contemporaries.

According to Babette Bohn, approximately fifteen hundred drawings are now attributable to Barocci («Drawing as artistic invention: Federico Barocci and the Art of Design» , Federico Barocci Renaissance Master of Color and Line, exhibition catalog Saint Louis Art Museum, 2012, p. 33), while Nicholas Turner has about two thousand ( Federico Barocci, Paris, 2000, p. 150), making him one of the most prolific artists of the Italian Renaissance: an exceptional number in term of preservation of the graphic work of a 16th century artist. His very slow creative process was notorious; he produced numerous drawings which he used to prepare each of the figures for his paintings, as well as more finished modelli

Not limiting himself to the use of a single medium, Barocci often associates chalks with different colored pencils and pastels, always starting in sketching with black chalk, as in our drawing. There is no doubt that Barocci took a major step in the development of the medium, not just employing colours that were not hitherto available in natural chalk but also using the materials that were sold enough to colour areas rather than draw lines. Only Jacopo Bassano working in Venice at the same time, offers any real parallel with these developments.

48

Our sheet is one of his studies of figures that display stunning realism with a melancholic aesthetic so characteristic of the artist. However, this does not seem to correspond to a specific painting. The composition of our study is also reminiscent of countless Barocci studies of head. The face takes up almost the entire sheet, standing out from a background quickly sketched in black chalk with large parallel oblique hatchings, as in a drawing located in the Louvre Museum, depicting a Young naked man leaning forward to take a vase , black and red chalk heightened with white, pastel on grey-green paper, squared, 38,3 x 24,2 cm, collections: Saint-Morys, INV 2860.

This drawing concentrates the graphic writing and the symptomatic features of Barocci’s style: the almond-shaped eyes with an outline traced in black chalk heightened with red chalk, shadows indicated by stumping or fine hatching in black chalk. Similarly, the artist often makes use of faded red chalk at the level of the eyelids outlined in red, the ears and the lips, which are all pink nimbus treated in subtle sfumato like the beard and mustache of the model. This technique allows Barocci to focus on the eyes. In full mastery of his art here, Federico manages to model the face with refinement with highlights of white chalk. In the collection of the Louvre Museum, a perfect example: Head of a woman, three-quarters and leaning to the right, eyes lowered, black chalk, red chalk, white chalk and pastel, on brown paper, 23,7 x 21,2 cm, collections: Conti, prince de - Mariette, Pierre-Jean - Crozat, Pierre (1665-1740) - Desmarets - Saint-Morys, Charles-Paul-J.-B. by Bourgevin Vialart de (1743-1795) - Paillet, Alexandre Joseph (1743-1814) - Ménageot, Augustin, INV 2866. Finally, the handling of the hair in our study refers to that of the Head of a young boy, with shaved hair, in profile to the right , black and red chalk, pastel heightened with white on gray paper, 33 x 24,7 cm, Collections: Cabinet du Roi, INV 2871, also in the Louvre. Thus in both cases, the artist uses pastel in a flat tint then faded then heightened with a few fine hatchings quickly sketched in black chalk, the skull surrounded by a contour line.

As in many of the artist’s works, our drawing testifies to his ability in studying and rendering the psychology of the characters. Here he captures the gaze of this man lost in thought with great psychological finesse. The theatricality is underlined by the colors and the effects of chiaroscuro.

Federico Fiori He was born at Urbino, Duchy of Urbino, and received his earliest apprenticeship with his father, Ambrogio Barocci, a sculptor of some local eminence. He was then apprenticed with the painter Battista Franco in Urbino and studied the paintings of the genius of his city, Raphael, as well as Titian, then later took Daniele da Volterra, the Venetians and Correggio as models. He accompanied his uncle, Bartolomeo Genga to Pesaro, then in 1548 to Rome, where he was worked in the pre-eminent studio of the day, that of the Mannerist painters, Taddeo and Federico Zuccari. After passing four years at Rome, he returned to his native city, where his first work of art was a St. Margaret executed for the Confraternity of the Holy Sacrament. He was invited back to Rome by Pope Pius IV to assist in the decoration of the Vatican Belvedere Palace at Rome, where he painted the Virgin Mary and infant, with several Saints and a ceiling in fresco, representing the Annunciation. During this second sojourn, while completing the decorations for the Vatican, Barocci fell ill with intestinal complaints. He suspected that a salad which he had eaten had been poisoned by jealous rivals. Fearing his illness was terminal, he left Rome in 1563.

While Barocci was removed from Rome, the fulcrum of artistic fame and influence, he continued to innovate in his style. At some point he may have seen colored chalk-pastel drawings by Correggio, but Barocci’s remarkable pastel studies are the earliest examples of the technique to survive. In pastels and in oil sketches (another technique he pioneered) Barocci’s soft, opalescent renderings evoke the ethereal. Such studies were part of a complex process Barocci used to complete his altarpieces. He died in Urbino in 1612, aged 84.

The artist biographer Giovanni Bellori, the Baroque equivalent of Giorgio Vasari, considered Barocci to be among the finest painters of his time. In the Marche area, his personal interpretation of Mannerism had immediate success. In the other areas, on the other hand, his art knew a slower diffusion. Younger artists understood his importance: influenced by Barocci, Carracci and the Bolognese painters (Guido Reni in particular) developed their own innovations.

We are grateful to Andrea Emiliani and Nicholas Turner for confirming the attribution to Barocci.

49

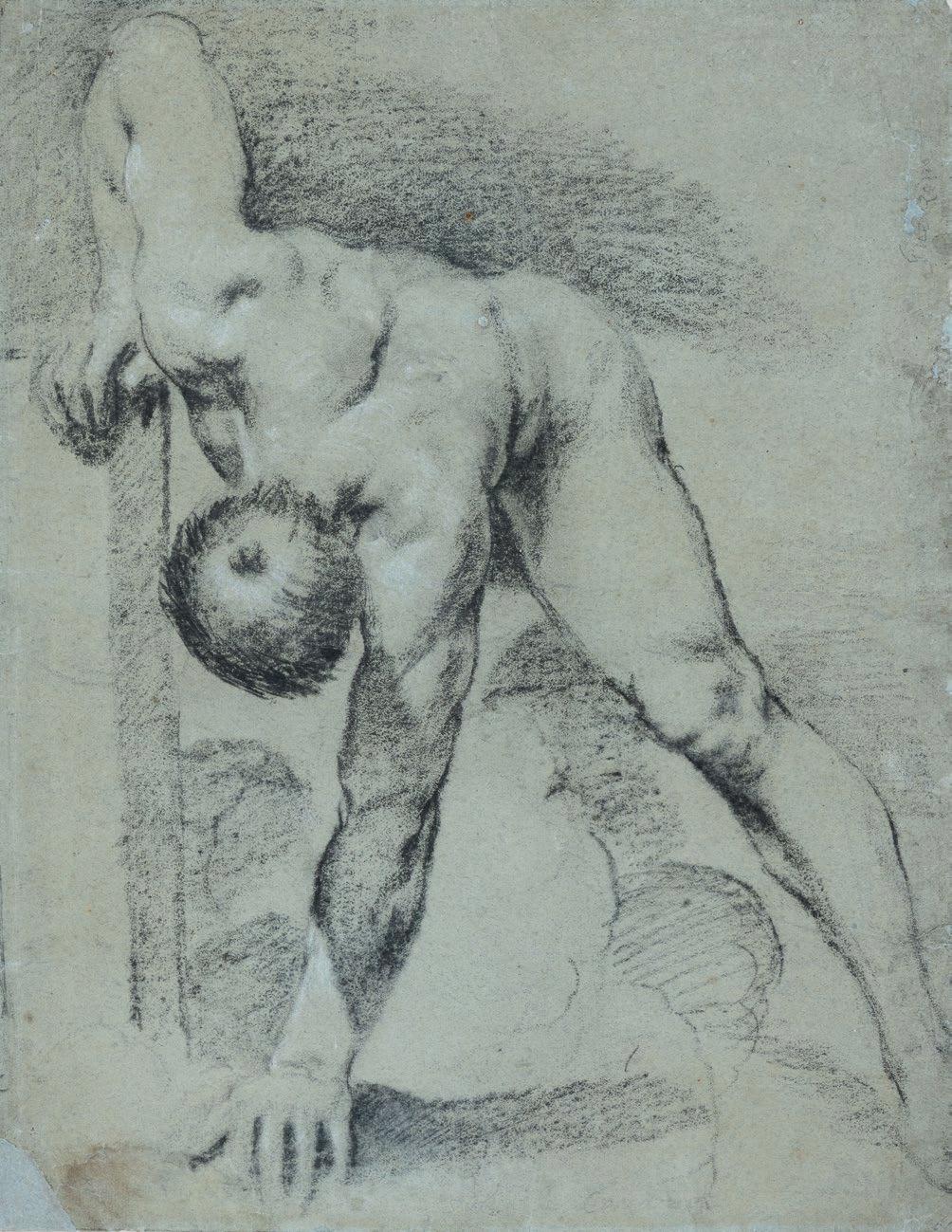

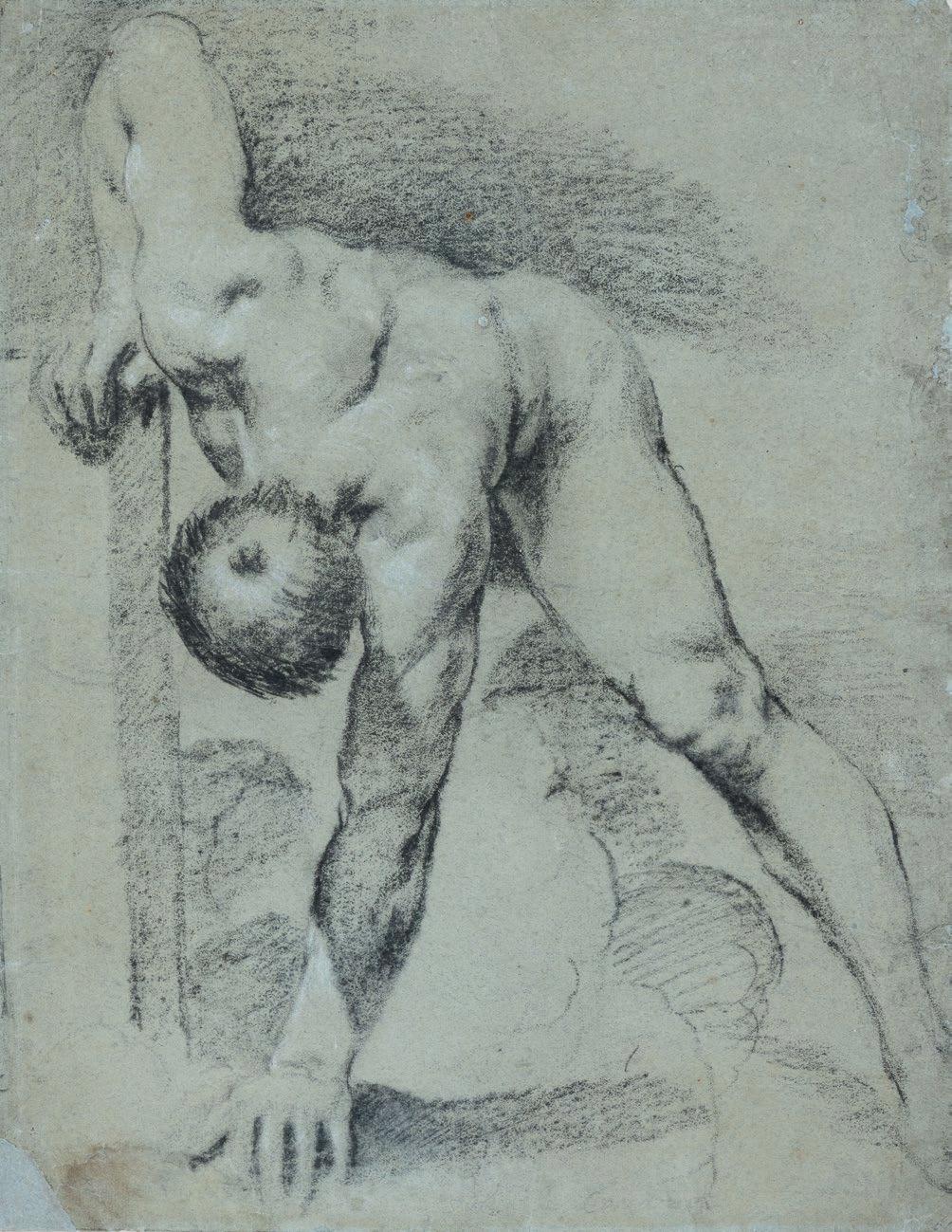

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, dit Guercino

(1591-1666)

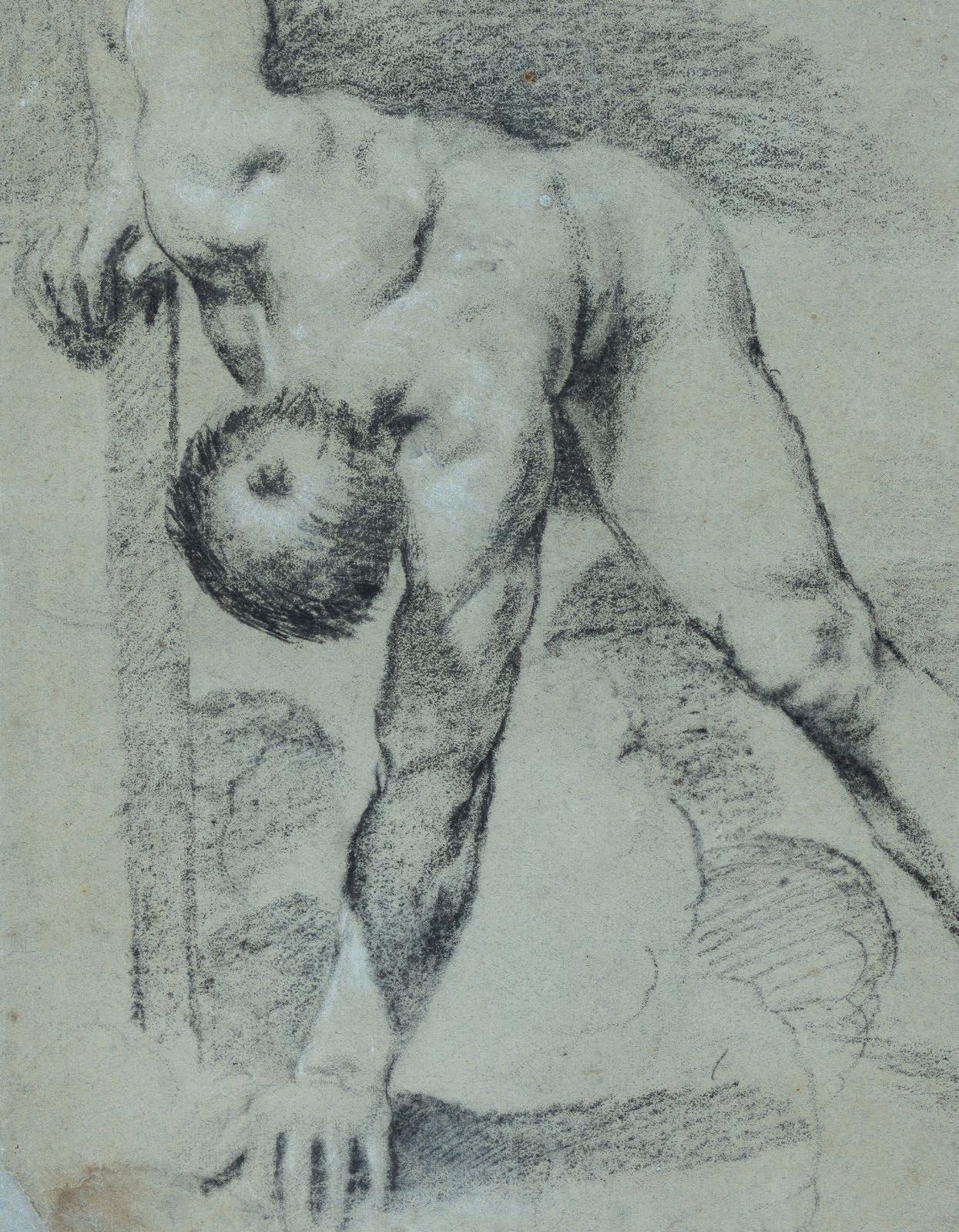

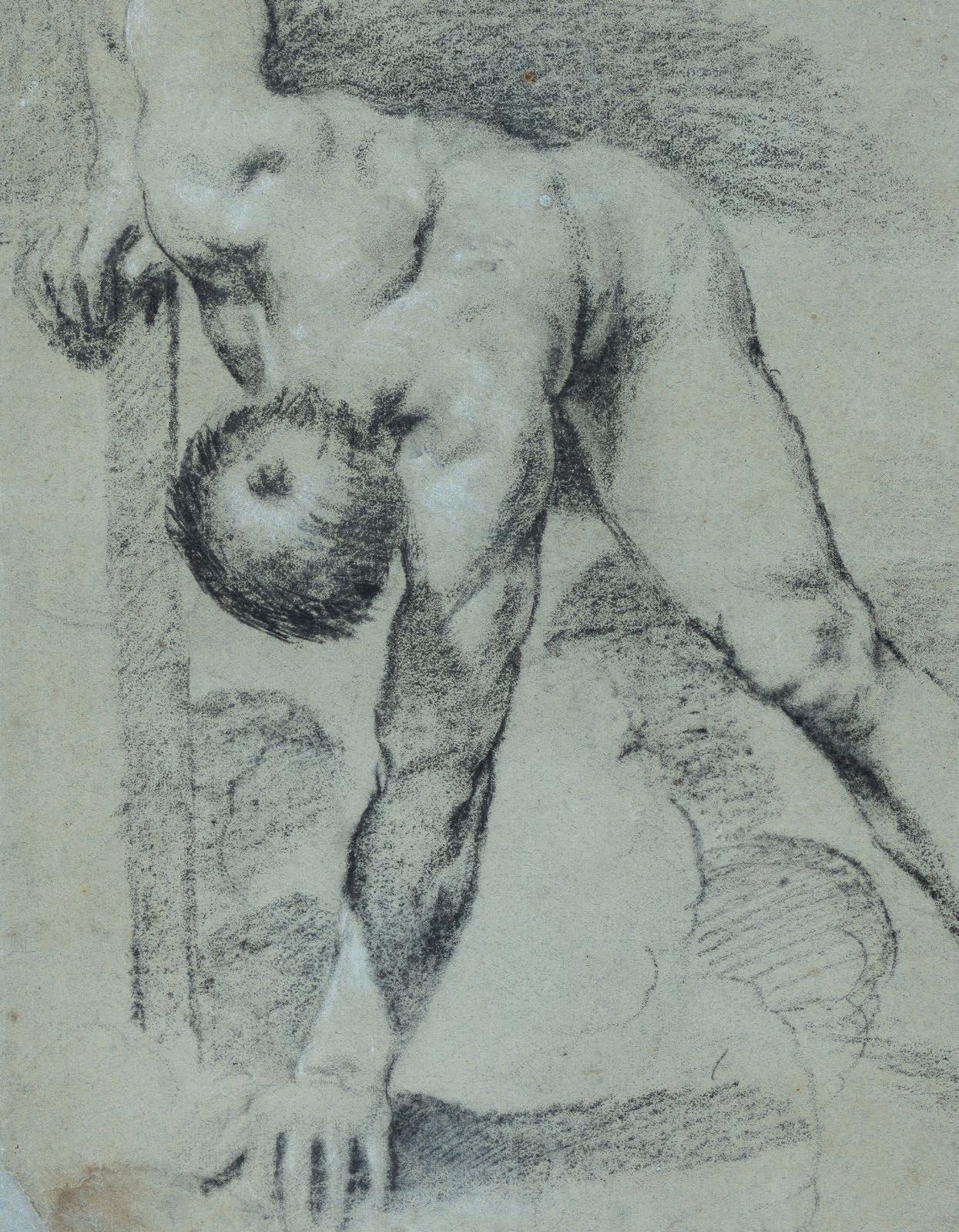

Homme nu penché (recto) ;

Homme agenouillé, les mains liées derrière le dos (verso)

Leaning Nude Man (recto);

Kneeling Man, Hands Tied Behind His Back (verso)

Pierre noire rehaussée de blanc sur papier bleu-gris clair

46 x 35,5 cm

Provenance :

• Collection particulière, France.

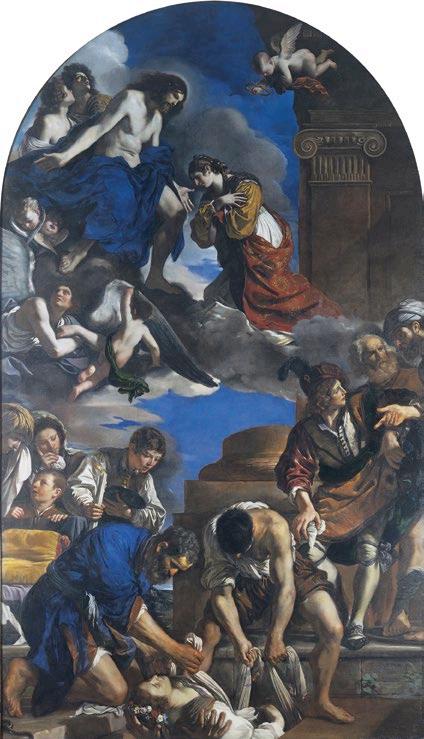

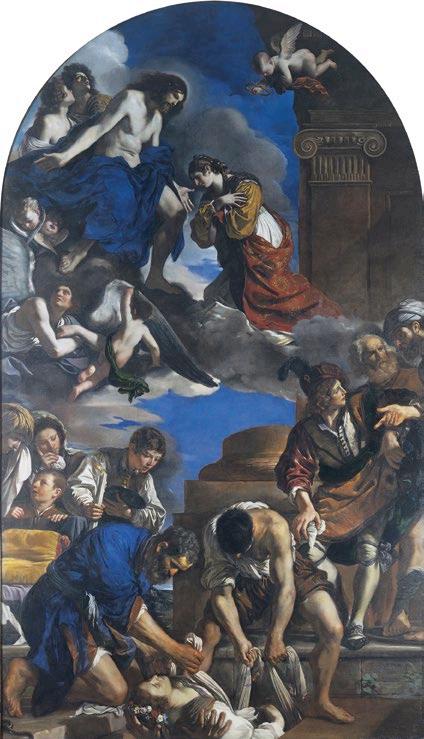

Oeuvres en rapport :

• Recto avec l’Enterrement et l’Assomption de Sainte Pétronille de Guercino, peint en 1623 pour Saint-Pierre et aujourd’hui conservé à la Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome ;

• Verso avec le Martyre de Saint Jacques le Majeur de Guercino, peint en 1627 pour la Cappella Prini dans SS. Pietro e Prospero, Reggio Emilia ; disparu mais connu par la gravure de Giovanni Battista Pasqualini, Bologne, Pinacoteca Nazionale.

Black chalk heightened with white on light blue-grey paper 46 x 35.5cm

Provenance:

• Private collection, France.

Related works:

• Recto with the Burial and Assumption of Saint Petronilla by Guercino, painted in 1623 for Saint Peter and now at the Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome;

• Verso with the Martyrdom of Saint James the Greater by Guercino, painted in 1627 for the Cappella Prini in SS. Pietro and Prospero, Reggio Emilia; lost but known from the engraving by Giovanni Battista Pasqualini, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale.

50 08 |

51

Cette fascinante feuille recto-verso a récemment été reconnue comme l’une des premières œuvres de Guercino par Nicholas Turner.

Notre dessin appartient ainsi à la première phase de Guercino ; de fortes concordances de style le rapprochent des académies généralement attribuées à la première période avant que Guerchin ne visite Rome en 1621 ou juste après. Le type physique mis en place au recto de notre feuille se retrouve dans le Nu allongé vu de dos, fusain sur papier beige, 35,2 x 46,8 cm, annoté à l’encre en bas à droite R:C.A R.SM.C , filigrane SESTO , Bologne, Pinacoteca Nazionale ; ou encore le Nu masculin assis, torse vu de dos , sanguine et rehauts de blanc sur papier beige, 33,7 x 27,2 cm, inscription au crayon au verso « Coreggio », Inv. 2536, Institut Néerlandais, Fondation Custodia, collection Fritz Lugt, Paris.

Par sa vivacité, le recto rappelle deux études de Guercino conservées à Windsor Castle. Ces dessins de la Collection Royale, d’une graphie comparable, font preuve de ce même esprit « pris sur le vif »: Nu assis sur le sol (recto) et à droite, une étude du bas du dos et des fesses d’une femme, et en bas à gauche une poire (verso), circa 1616-20, fusain et pierre noire sur papier chamois-grisâtre, 30,0 x 26,3 cm, RCIN 902415 ; et Un homme nu gisant, circa 1618-19, fusain huilé, avec quelques rehauts de blanc, sur papier chamois, 38,5 x 57,6 cm, RCIN 991227.

Deux observations principales concernant le recto de notre dessin peuvent être faites : premièrement, il s’agit d’une feuille d’académie, et deuxièmement, il révèle l’influence évidente de Faccini (on peut le considérer comme la référence stylistique la plus importante cette période). L’étude du modèle vivant était une préoccupation majeure à l’académie Carracci de Bologne, et donc aussi pour Guercino, qui a ensuite adopté cette approche dans sa création d’une Accademia del Nudo à la Casa Fabri. Nicholas Turner précise que la soi-disant « réforme de la peinture » réalisée par les Carracci à Bologne est née de leur pratique consistant à fonder la peinture figurative sur l’observation précise de la figure humaine à travers le dessin, à la fois dans son mouvement et son expression. L’un des disciples des Carracci, Pietro Faccini (v. 1562-1602), à qui ce dessin était autrefois attribué, aimait particulièrement réaliser de grandes académies à partir du nu masculin, à la pierre noire, comme ici, plutôt qu’à la sanguine, généralement préférée par les Carracci eux-mêmes. Il aimait aussi indiquer les zones sombres dans les marques fortement accentuées, indiquant les tons moyens dans des zones d’ombrage plus uniformément traitées, ce qui se retrouve dans la manière de notre feuille.

Malvasia fait référence à l’intérêt particulier de Guercino pour les dessins de Faccini, qui lui ont été montrés par le Padre Antonio Mirandola, le premier mécène à découvrir le jeune artiste. Le dessin au fusain ou à la pierre noire de la période pré-romaine de Guerchin montre en effet l’influence directe de la technique et du style de Faccini, en particulier dans leurs forts contrastes d’ombre et de lumière. Cette technique du fusain huilé sur papier teinté était en effet favorisée par le contemporain et rival des Carracci, dont les dessins étaient admirés par Guercino. Le caractère collant du fusain interdisait les détails fins et conduisait à une largeur de forme et à des ombres lourdes, parfaitement adaptées au riche style figuratif précoce de Guercino.

L’utilisation de craie noire, plutôt charbonneuse, associée à de légères touches de craie blanche est également caractéristique de certaines premières études de Guerchin. La pierre noire grasse et moelleuse du recto permet à Guercino de travailler en dessin le clair-obscur et de donner à son académie d’homme sa vie et son expressivité. L’artiste fait preuve d’une aptitude à pourvoir aux besoins spécifiques d’une iconographie religieuse grâce à l’observation d’après nature en utilisant ses académies. S’il est difficile de donner des dates précises pour les études de nus de la période pré-romaine puisque pour la plupart elles n’étaient pas destinées à être préliminaires à une œuvre d’art finie, elles révèlent souvent l’artiste expérimentant des poses qu’il utilisa plus tard dans ses peintures.

Ainsi, la pose de notre feuille au recto est presque consciemment difficile, mais néanmoins élégante, suggérant qu’elle a peut-être été faite pour elle-même. Elle aurait en effet pu être conçue comme un exercice plutôt qu’en relation avec l’une des figures de la composition du retable de la chapelle Prini. Comme Nicholas Turner le souligne, Guercino avait l’habitude de faire des dessins d’après nature à part entière dans sa première période, qui servaient d’exemples à ses élèves. Ces dessins étaient généralement réalisés à la craie noire ou au fusain huilé, parfois combinant les deux, et parfois rehaussés de blanc. Ils étaient invariablement dessinés sur du papier teinté, gris-bleu (le type de papier utilisé ici), ou chamois. Ils étaient généralement soigneusement finis, avec une grande attention portée à la musculature du modèle et à la représentation de la lumière sur le corps.

52

53

L’homme nu de l’étude au recto appuie son corps sur un bâton, tout en touchant le sol de sa main gauche. Sa pose et la façon dont l’arrière de sa tête est tournée vers le spectateur rappellent la pose du jeune fossoyeur au premier plan central du grand retable de Guerchin de l’ Enterrement et de l’Assomption de Sainte Pétronille , peint en 1623 pour Saint-Pierre et maintenant à la Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome. Dans le présent dessin, Guerchin recyclait probablement la pose de ce personnage, avec des modifications, afin d’explorer, pour le bénéfice de ses élèves, le raccourci difficile que présentait cette position audacieuse pour le modèle.

Pietro e Prospero, Reggio Emilia. L’artiste a commencé le retable alors qu’il travaillait encore sur ses fresques dans la coupole de la cathédrale de Plaisance. Ce retable perdu survit, à l’envers, dans une gravure de Giovanni Battista Pasqualini, datée de 1628, dans laquelle le compagnon du saint, barbu et vêtu d’un pagne, apparaît à gauche, regardant vers la droite. Guercino repris d’ailleurs cette pose agenouillée dans un autre dessin à la pierre noire plus abouti sur papier chamois de la Pinacothèque nationale de Bologne, mais cette fois à partir d’un modèle nu imberbe prenant une pose beaucoup plus proche de son équivalent peint final (inv. no. 3679 ; 42 x 27 cm. Le traitement délicat de la lumière et de l’ombre du dessin de Bologne constitue une bonne comparaison avec le traitement du nu étudié au recto de notre feuille.

De même, Nicholas Turner souligne que la figure du compagnon du Saint apparaît encore dans de nombreuses variantes de pose : celles de la Bibliothèque royale du château de Windsor (D. Mahon et N. Turner, The Drawings of Guercino in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, Cambridge, 1989, pp. 24-25, nos 46 et 47); le Teylers Museum, Haarlem (C. van Tuyll van Serooskerken, Guercino (1591-1666) : Drawings from Dutch Collections , catalogue d’exposition,

pp. 66-67, n° 19) ; l’Instituto Nazionale della Grafica, Rome (D. Mahon, Guercino, Disegni , catalogue d’exposition, Bologne, 1968, n° 112) ; et le Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginie (E. M. Zafran, One Hundred Drawings in the Chrysler Museum at Norfolk, catalogue d’exposition, Mars à Mai 1979, p. 14, n° 16).

La virtuosité technique de l’artiste et sa capacité à obtenir des effets extraordinaires de force et de luminosité sont frappantes dans cette feuille recto-verso, qui témoigne de son esprit créatif et expérimental.

L’attribution au Guerchin de ce dessin rectoverso est confirmée par l’étude au verso d’un homme agenouillé, les mains liées derrière le dos, qui est une représentation précoce de cette pose, probablement d’après le modèle vivant, pour le compagnon de Saint Jacques figurant sur le retable perdu du Guerchin du Martyre de Saint Jacques le Majeur, peint en 1627 pour la Cappella Prini dans SS.

Nous remercions Monsieur Nicholas Turner, co-auteur avec Carol Plazzota de Drawings by Guercino from British Collections , d’avoir confirmé l’attribution de notre dessin et d’avoir rédigé une expertise (en date du 23 Juillet 2010).

55

This fascinating double-sided sheet was recently identified as one of Guercino’s earliest works by Nicholas Turner.

Our drawing thus belongs to the first phase of Guercino’s activity; strong concordances in style bring it closer to the academies generally attributed to the first period before Guercino visited Rome in 1621 or just after. The physical type set up on the recto of our sheet is found in the Reclining Nude seen from behind , charcoal on beige paper, 35.2 x 46.8 cm, annotated in ink lower right R:C.A R.SM .C, watermark SESTO, Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale; or the Seated male nude, torso seen from behind, red chalk heightened with white on beige paper, 33.7 x 27.2 cm, inscription in pencil on the back « Coreggio », Inv. 2536, Dutch Institute, Custodia Foundation, Fritz Lugt collection, Paris.

The liveliness of the recto is reminiscent of two studies by Guercino in Windsor Castle. These drawings from the Royal Collection, with a comparable draughtsmanship, show the same handling

« taken from life »: Nude seated on the ground (recto) and on the right, a study of the lower back and buttocks of a woman , and l ower left a pear (verso), circa 1616-20, charcoal and black chalk on greyishbuff paper, 30.0 x 26.3 cm, RCIN 902415; and a Reclining male Nude , circa 1618-19, oiled charcoal, heightened with white, on buff paper, 38.5 x 57.6 cm, RCIN 991227.

Two principal observations regarding the recto of our drawing may be made: first, it is an academy sheet, and secondly, it reveals the obvious influence of Faccini (it can be considered the most important stylistic reference of this period). Study of the live model was a primary concern in the Carracci Academy in Bologna, and therefore also for Guercino, who later embraced this approach in his establishment of an Accademia del Nudo in the Casa Fabr i. Nicholas Turner clarifies that the so-called « reform of painting » achieved by the Carracci in Bologna came about from their practice of basing figurative painting on the accurate observation of the human figure through drawing, both in its movement and its expression. One of Carracci’s followers, Pietro Faccini (c. 1562-1602), to whom this drawing was formerly attributed, was especially fond of making large-scale nude studies from the male nude, in black chalk, as here, rather than in red chalk, the medium generally preferred by the Carracci themselves. He was also fond of indicating dark areas in heavily accented marks, indicating the mid-tones in more evenly handled patches of shading, which is also paralleled in the handling of our sheet.

Malvasia refers to Guercino’s particular interest in Faccini’s drawings, which were shown to him by Padre Antonio Mirandola, the first patron to discover the young artist. Guercino’s pre-Roman period charcoal or black chalk drawing indeed shows the direct influence of Faccini’s technique and style, particularly in their strong contrasts of light and shadow. This technique of oiled charcoal on tinted paper was indeed favored by the contemporary and rival of the Carracci, whose drawings were admired by Guercino. The stickiness of the charcoal forbade fine detail and led to a breadth of form and heavy shading, perfectly suited to Guercino’s rich early figurative style.

56

The use of black chalk, rather charcoal, associated with light touches of white chalk is also characteristic of certain early studies by Guercino. The oily and soft black chalk of the recto allows Guercino to drawn in chiaroscuro in drawing and to render his academy of man with life and expressiveness. The artist demonstrates an ability to provide for the specific needs of religious iconography through observation from life using his academies. This ability to meet the specific needs of religious iconography through observation of reality produced compositions really understandable to those who contemplated his paintings in churches. While it is difficult to give precise dates for nude studies from the pre-Roman period since for the most part they were not intended to be preliminary to a finished work of art, they often reveal the artist experimenting with poses that he later used in his paintings.

The pose of the recto is almost consciously difficult, but elegant nonetheless, suggesting that it may have been made for itself. It could indeed have been conceived as an exercise rather than in relation to one of the figures of the composition of the altarpiece of the Prini chapel. As Nicholas Turner points out, Guercino used to make full-fledged life drawings in his early period, which served as examples for his students. These drawings were usually done in black chalk or oiled charcoal, sometimes combining the two, and sometimes heightened with white. They were invariably drawn on tinted paper, gray-blue (the type of paper used here), or buff. They were usually carefully finished, with great attention paid to the figure’s musculature and the fall of light across the body.

The male nude in the recto study supports his body on a staff, while touching the ground with his left hand. Both his pose and the way the back of his head is turned towards the viewer recalls the pose of the young gravedigger in the central foreground of Guercino’s large altarpiece of the Burial and Assumption of Saint Petronilla , painted in 1623 for Saint -Peter and now in the Pinacoteca Capitolina, Rome. In the present drawing, Guerchin probably recycled the pose of this figure, with modifications, in order to explore, for the benefit of his students, the difficult foreshortening presenting by this daring position for the model.

The attribution to Guercino of this double-sided drawing is confirmed by the study on the verso of a kneeling man, his hands tied behind his back, which is an early representation of this pose, probably from life, for the companion of Saint James in Guercino’s lost altarpiece of the Martyrdom of Saint James the Greater , painted in 1627 for the Cappella Prini in SS. Pietro and Prospero, Reggio Emilia. The artist began the altarpiece while he was still working on his frescoes for the dome of the Cathedral of Plaisance. This lost altarpiece survives, in reverse, in an engraving by Giovanni Battista Pasqualini, dated 1628, in which the saint’s companion, bearded and wearing a loin cloth, appears on the left, looking to the right. Guercino also struck this kneeling pose in another more accomplished black chalk drawing on buff paper from the National Pinacoteca in Bologna, but this time from a beardless nude model striking a pose much closer to her final painted equivalent . (inv. no. 3679; 42 x 27 cm. The delicate treatment of light and shade in the Bologna drawing is a good comparison with the treatment of the nude studied on the recto of our sheet.

Likewise, Nicholas Turner points out that the figure of the Saint’s companion crops up in many variant poses: those in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle (D. Mahon and N.Turner,The Drawings of Guercino in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, Cambridge, 1989, pp. 24-25, nos. 46 and 47); the Teylers Museum, Haarlem (C. van Tuyll van Serooskerken, Guercino (1591-1666): Drawings from Dutch Collections, exhibition catalogue, pp. 66-67, n° 19); the Instituto Nazionale della Grafica, Rome (D. Mahon, Guercino, Disegni, exhibition catalogue, Bologna, 1968, no. 112); and the Chrysler Museum, Norfolk, Virginia (E. M. Zafran, One Hundred Drawings in the Chrysler Museum at Norfolk, exhibition catalogue, March to May 1979, p. 14, no. 16).

The artist’s technical virtuosity and his ability to achieve extraordinary effects of strength and luminosity are striking in this double-sided sheet, which testifies to his creative and experimental draughtsmanship.

We are grateful to Mr Nicholas Turner, co-author with Carol Plazzota of Drawings by Guercino from British Collections, for confirming the attribution of our drawing and for writing an expert report (dated 23 July 2010).

57

09 |

Bernardo Strozzi il Cappuccino

(Gênes 1581-1644 Venise)

Les Trois Parques The Three Fates

Plume et encre brune, lavis gris rehaussé de blanc sur papier préparé

20,5 x 23,3 cm

Provenance :

• Dorotheum Vienne, 18 Avril 2014, lot 111 (comme « atelier de Bernardo Strozzi ») ;

• Collection particulière, France.

Pen and brown ink, gray wash heightened with white on prepared paper

20,5 x 23,3cm.

Provenance: