01

REFLECTIONS ON DESIGN

This is the second issue of Anima. We set out last year to make a magazine that filled a gap in the design conversation. In a world in which information is instantly available, design needs a place for a more reflective view: somewhere to get to the heart of things and a chance to consider what is relevant. This edition finds out about a new generation of architects and discovers how they train. It looks at the language of typography and at life on the Moon. Nathalie du Pasquier and Dieter Rams share their inspirations and Samuel Ross predicts what is next. Welcome back.

02

Nathalie du Pasquier

Mami Wata

Otl Aicher

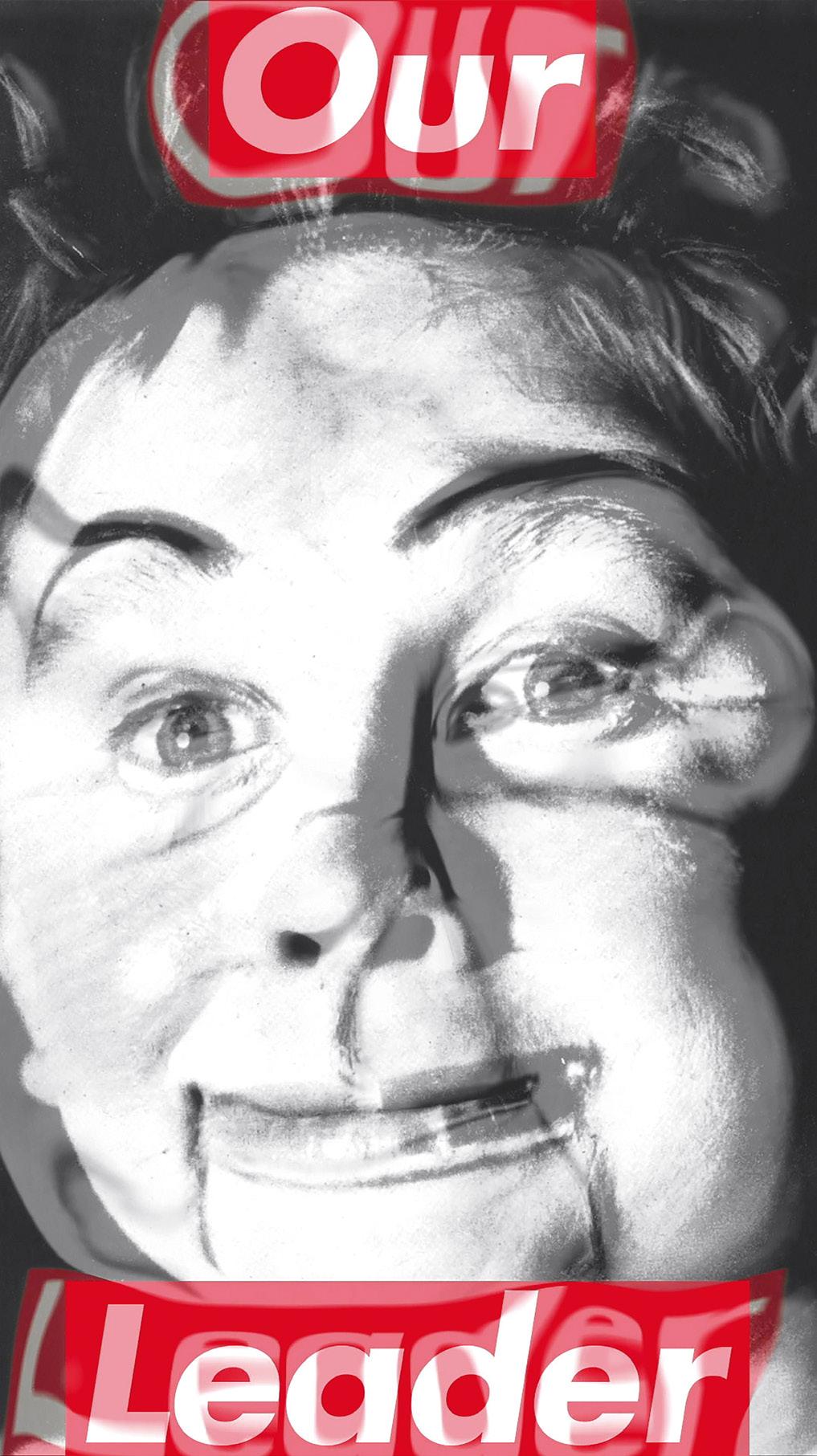

Barbara Kruger

Samuel Ross

Alessandro Mendini

Dieter Rams

Ferran Adrià

03

016 042 136 202 216 176 118 022 Issue Two 978 17394387 5 3

04 DEFINING THE NEW AND THE NEXT DAVÓNE TINES SINGER & CREATOR KANTEMIR BALAGOV FILMMAKER DALTON PAULA VISUAL ARTIST & EDUCATOR OONA DOHERTY CHOREOGRAPHER TOLIA ASTAKHISHVILI VISUAL ARTIST MOOR MOTHER POET & MUSICIAN SAM ENG GAME DEVELOPER ANNA THORVALDSDOTTIR COMPOSER HO TZU NYEN VISUAL ARTIST FOX MAXY FILMMAKER & VISUAL ARTIST

CHOREOGRAPHER

OONA DOHERTY

Dambo sofa collection, design Piero Lissoni. bebitalia.com

Milan London Paris Munich New York Washington DC Dallas Miami Boston

Designed by Italian Architect Antonio Citterio, Personal Line makes your home training experience truly unique with hundreds of video workouts on the integrated display and through Technogym App. Download the Technogym app Call +39 0547 650111 or visit technogym.com

HOME WELLNESS

DESIGN IS INNOVATION WITH A TWIST.

CAMELOT SOFA. DESIGN ANTONIO CITTERIO

MILAN DESIGN WEEK 16–21 APRIL 2024

SALONE DEL MOBILE. MILANO RHO FIERA HALL 9 | BOOTH E05 – F02 / E11 – F08

FLEXFORM MILANO VIA DELLA MOSCOVA 33

Nathalie du Pasquier is inspired, photographs by Alice Fiorilli

Afrosport celebrates cultural values

Pictograms: a language without words

Nuclear sublime, text by Richard Brook, photographs by Michael Collins

Galerie kreo, photographs by Emma Le Doyen

Living on the moon:

Hassell Architects have a plan

London School of Architecture, photographs by Henry Gorse

The political uses of typography, artwork by Alfie Allen

Technogym, photographs by Carlo Valsecchi

Samuel Ross, a conversation with a polymath

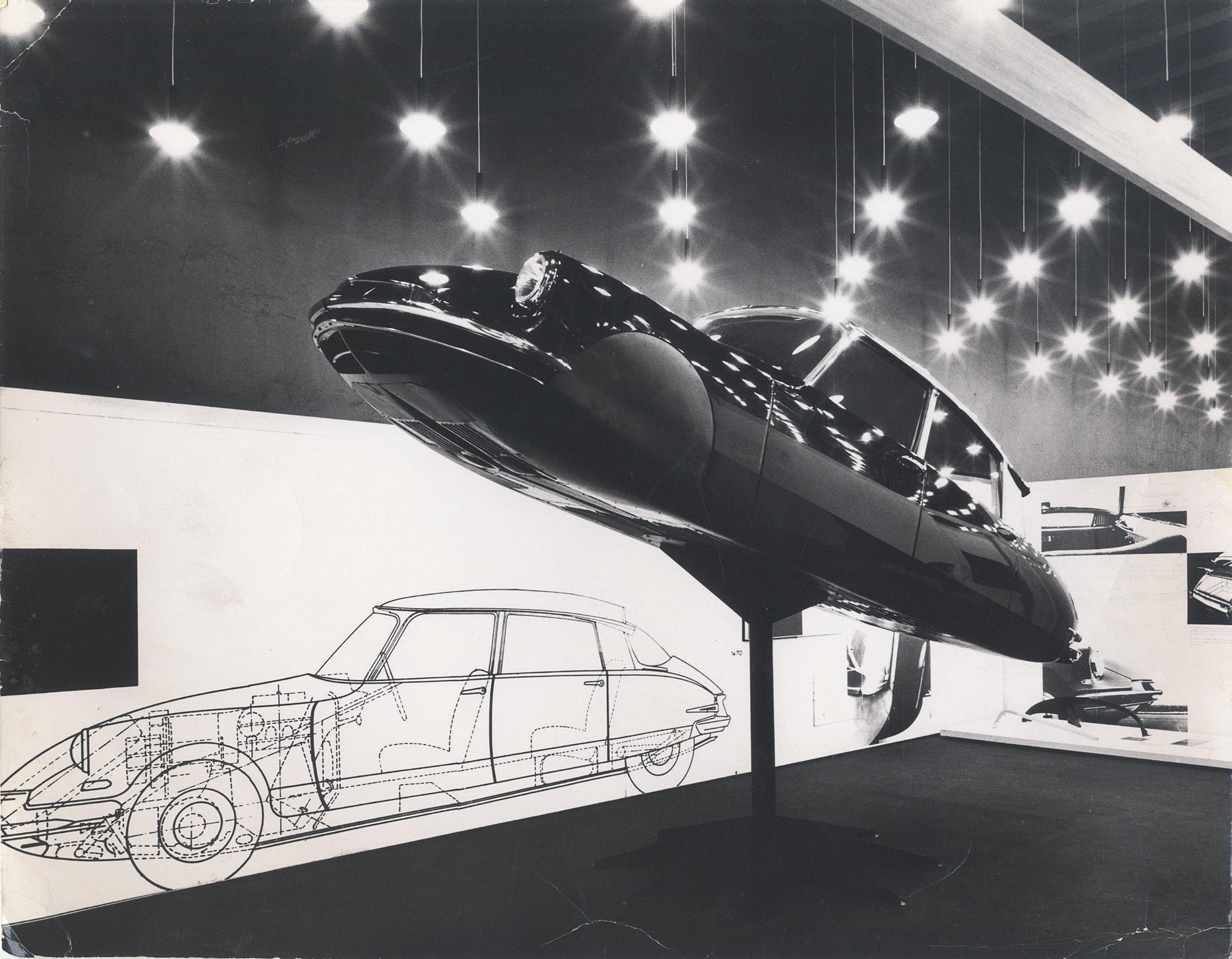

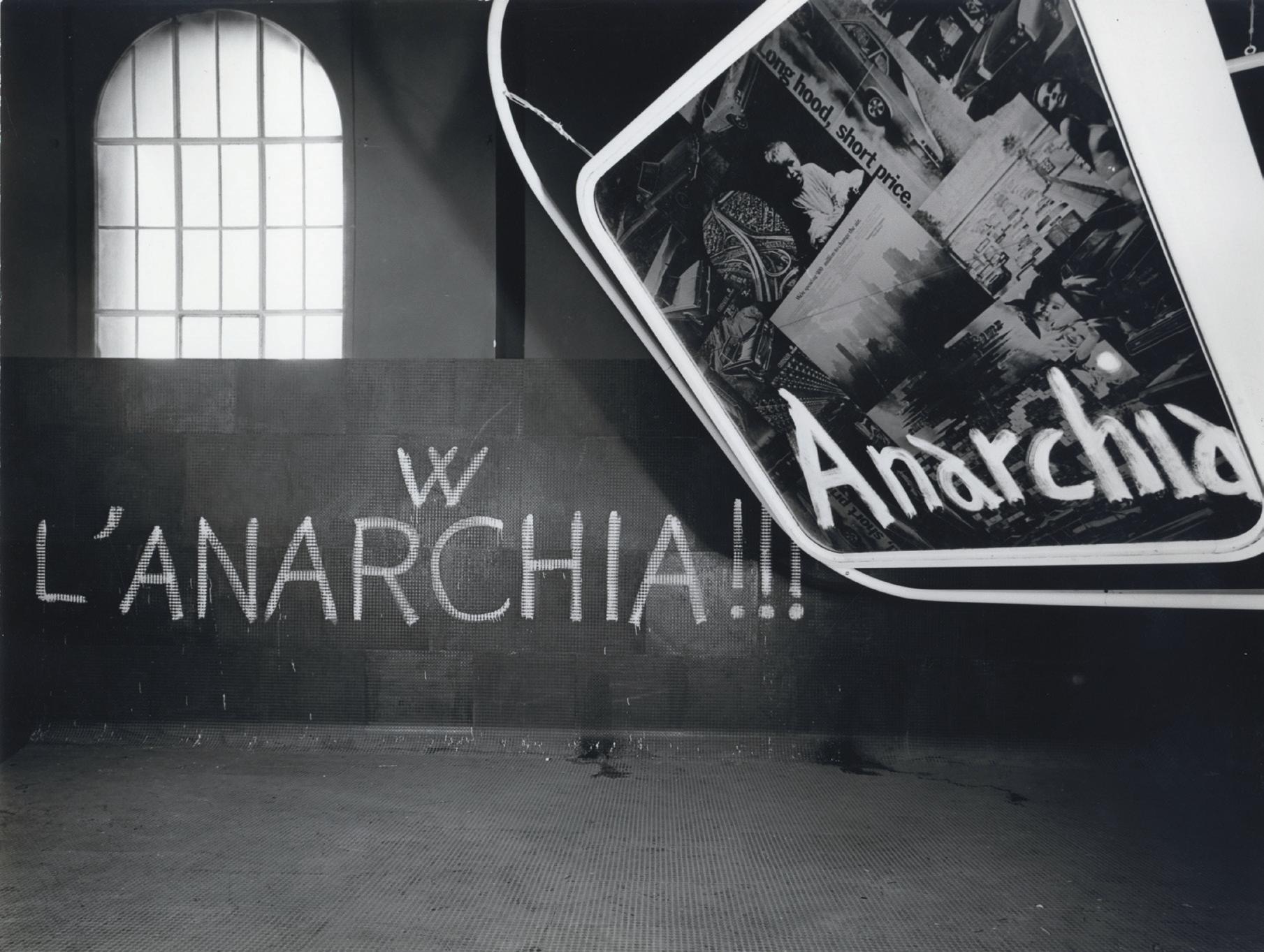

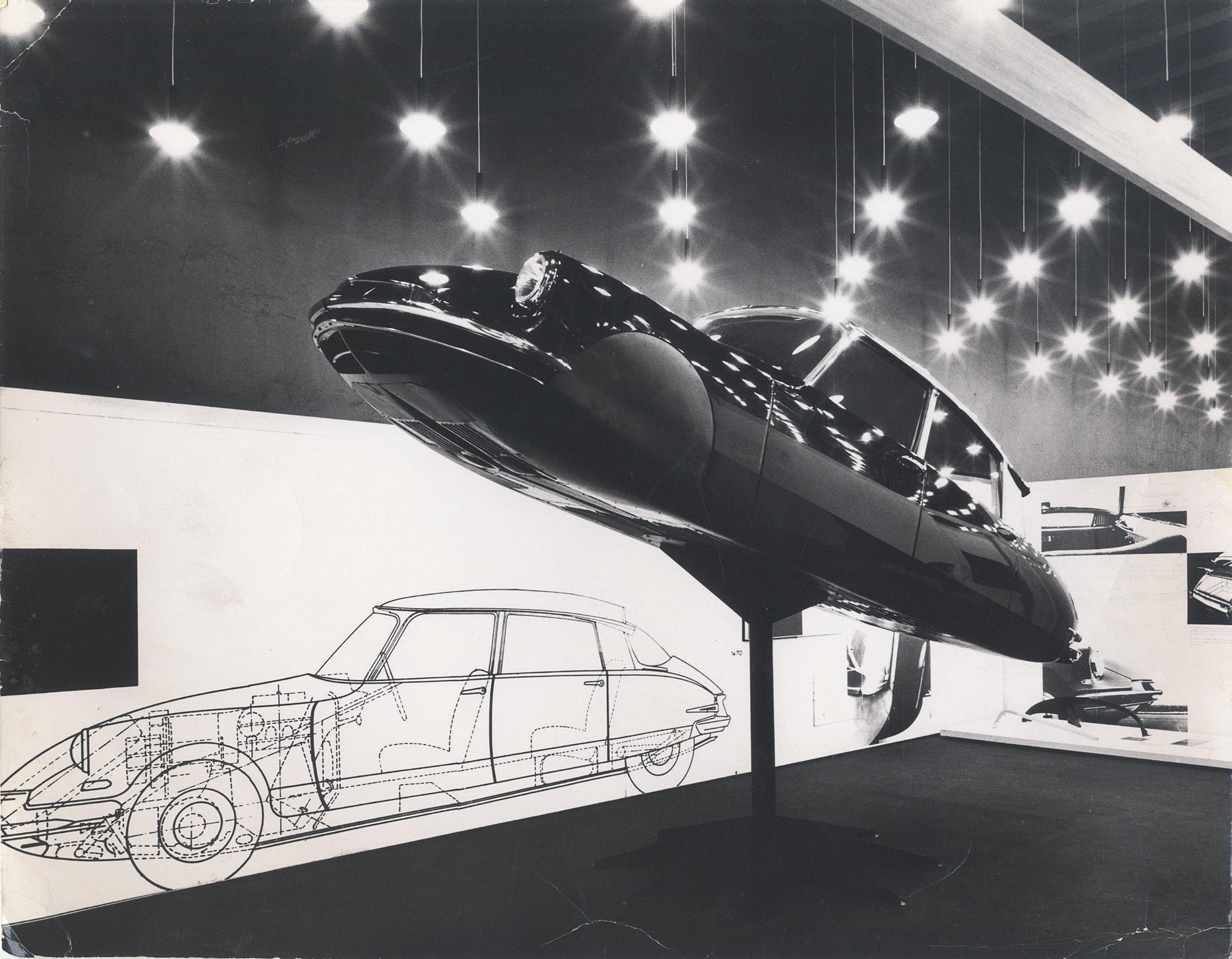

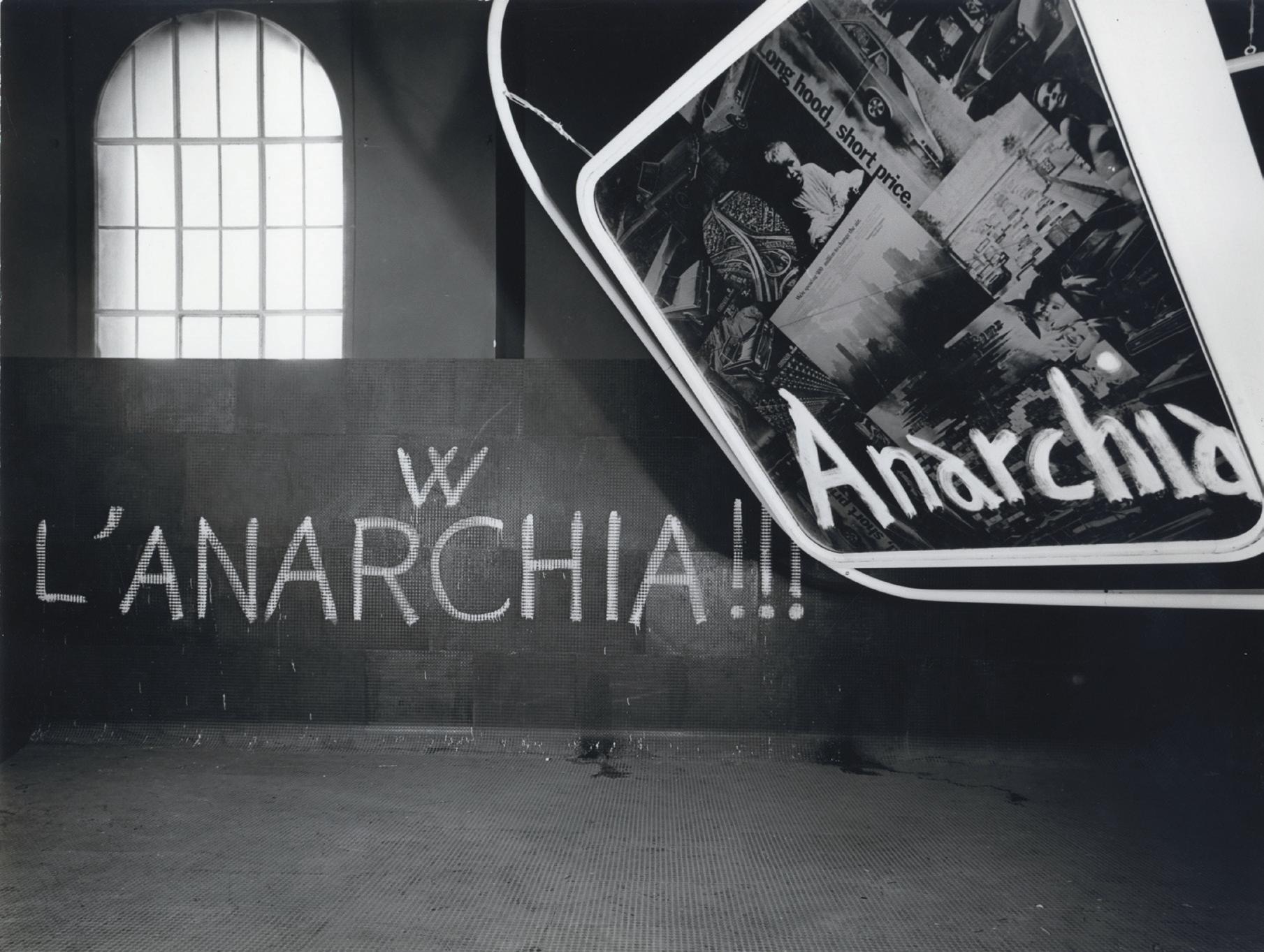

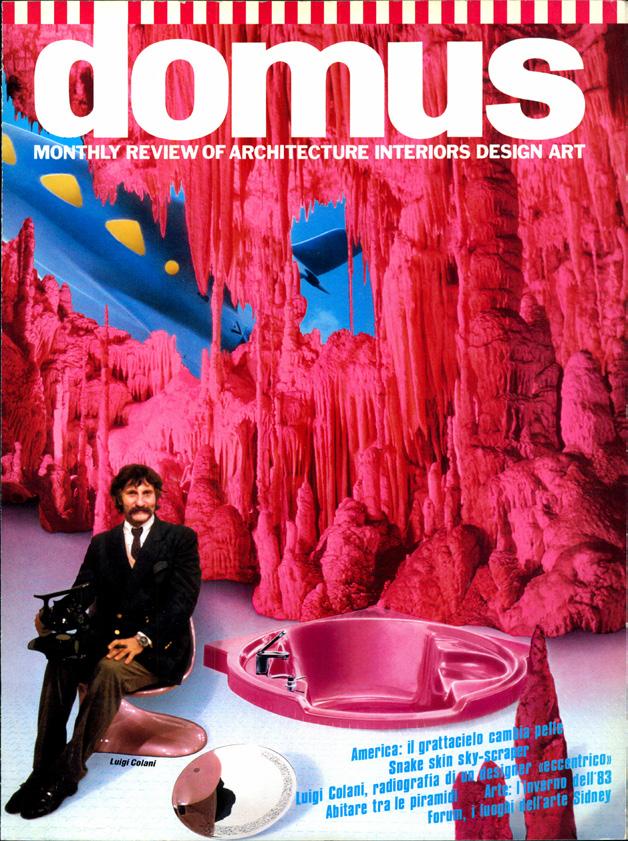

How the Milan Triennale changed design history

A portrait of the designer as an editor Alessandro Mendini

Milan in a van, photographs by Paolo Zerbini

Dieter Rams

looks back at Braun and forward to Vitsœ

Future recipes, artworks by Sharp & Sour, Leyu Li and Studio H

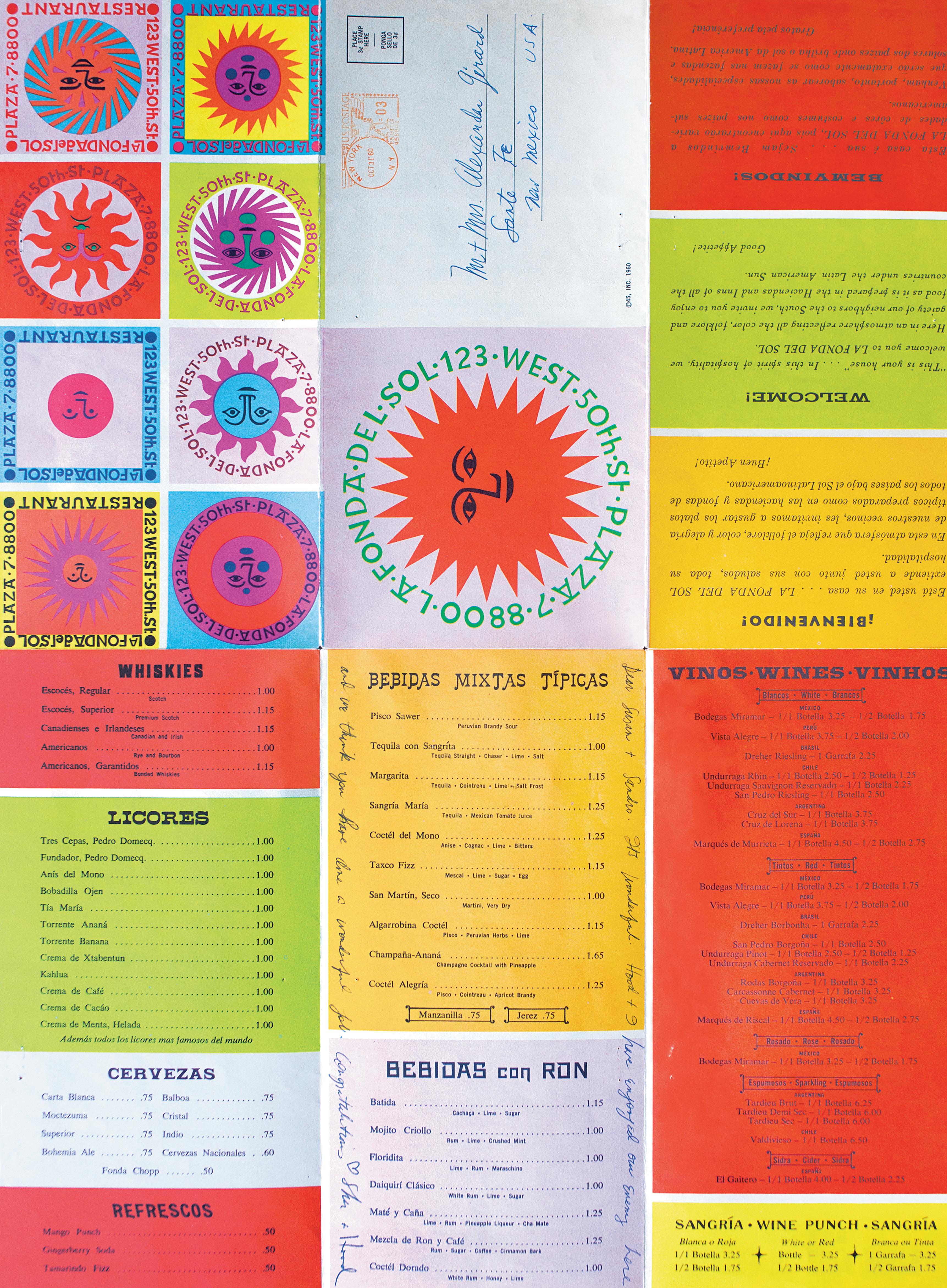

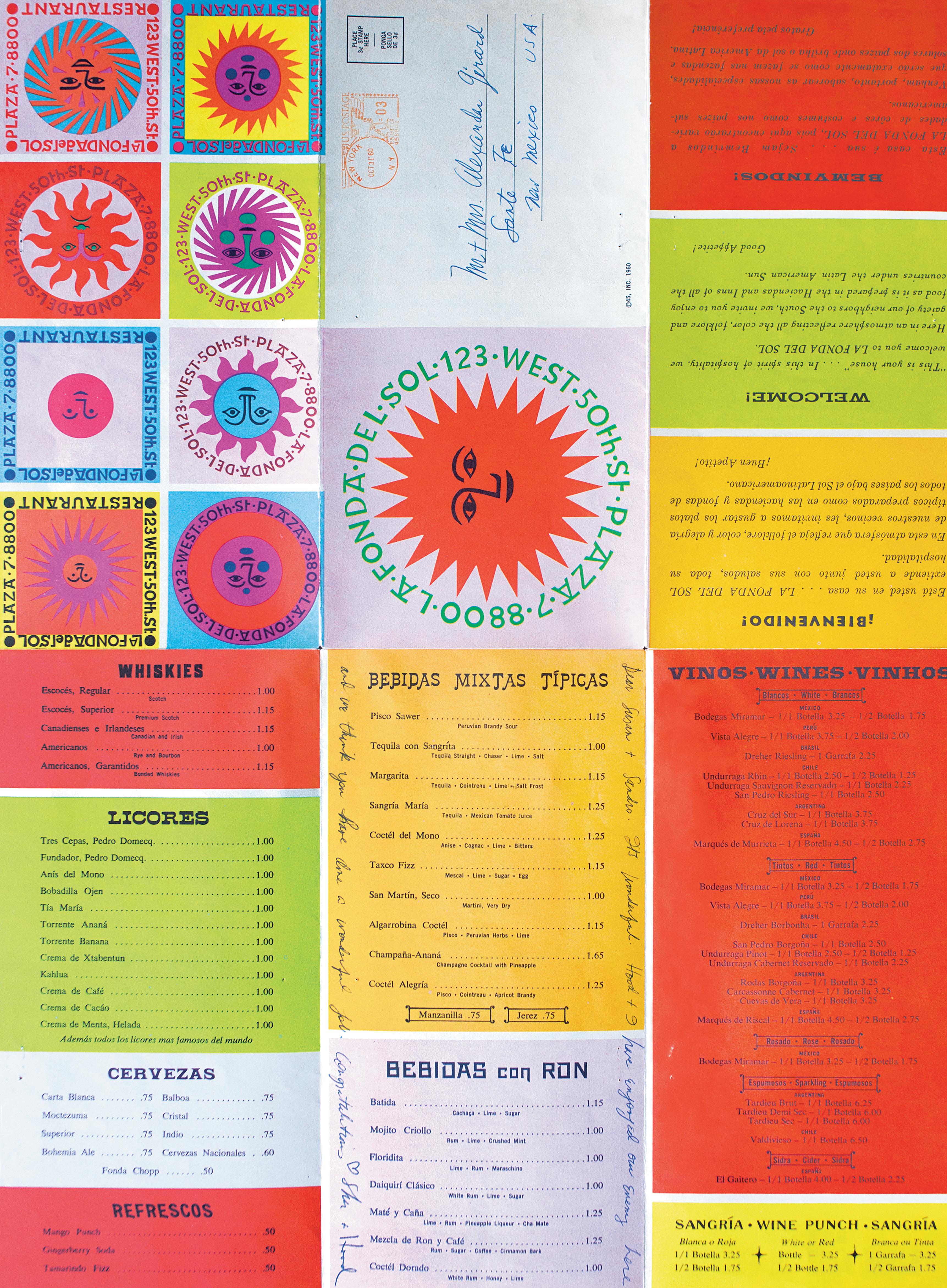

Design is on the menu: from Alexander Girard to Terence Conran

Alternatives to charcoal, text by Adriana Gallo

016 022 042 062 082 100 106 118 130 136 156 176 188 202 208 216 228

CONTENTS

Two of the designers we feature in this issue belong to the same generation. Dieter Rams and Alessandro Mendini were born within a year of each other, but it is hard to imagine two more different approaches, even if both had a certain distaste for the cruder aspects of commerce. Rams, throughout his career, has held to the belief that a designer is able to make a difference. That there is in absolute terms such a thing as good design, in both the performance and aesthetic sense, as well as the moral one. Mendini has always taken a much more nuanced view.

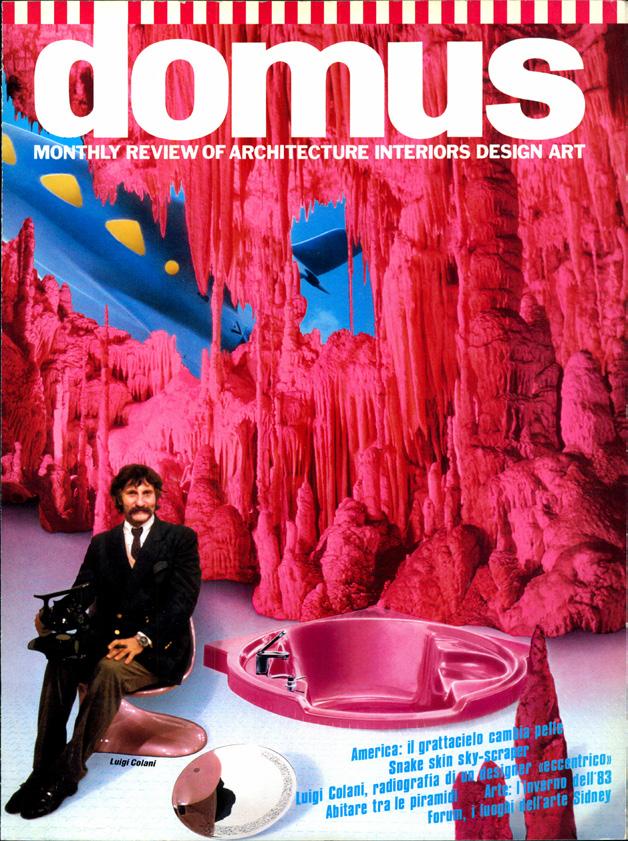

Rams did his best to purify the language of design to the extent that it could erase time and fashion. But the speed of technological change has rendered so much of his work for Braun obsolete, if beautiful. Mendini’s work has embraced the stronger flavours, and some of it now seems rooted in a particular moment in time. When Mendini was the editor of Domus, he put Rams on the cover of the magazine back in 1984 and interviewed him, one of the more historically unlikely encounters. Mendini asked Rams, who was clearly upset by one of his questions, “You were the prophet of the mythic period of Braun design. I have always thought of asking you this question: was your utopia functionalist or was it poetic and purist?” To which he replied: “I was not the ‘prophet’ of Braun design; if anything, I was a fairly important collaborator and companion in arms. Especially during the second period of Braun design. The first Braun period was marked by the Ulm school, through Hans Gugelot, in the sphere of product design and Otl Aicher in that of graphic design. My own work and that of my group would have been unthinkable without the way paved by them.”

The parameters of the world of design that their two positions established continue to shape the environment in which another generation operates. For this issue of Anima, we talked to Samuel Ross, who is fortunate to be able to learn from both, to take from them what he needs, and to form his own direction. Ross is emerging as a true polymath, involved with mass-produced objects, as well as art and design, driven by a sense of conviction that his work has a cultural purpose. We also photographed the students of the London School of Architecture, a much needed experiment in education, rooted in a practice that reflects the priorities of a new generation. We went to Milan to explore a newly invigorated Triennale and its archives, looked back on places to eat, and forward to the menus of the future.

In an age of short attention spans, and instant news, Anima gets below the surface to the heart of things to look at what makes design relevant.

– Deyan Sudjic

013

WHAT ANIMA IS THINKING

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Deyan Sudjic

MANAGING EDITOR Ayla Angelos

ART DIRECTION AND DESIGN Hondo Studio (Fran Méndez and Maria Vioque Nguyen)

PHOTO EDITOR Max Barnett

PHOTO EDITOR-AT-LARGE Holly Hay

SUB-EDITORS Sarah Kathryn Cleaver and Gus Wray

CONTRIBUTORS

Alfie Allen, Richard Brook , Quentin Buttin, Elena Campese, Emma Le Doyen, Antea Ferrari, Alice Fiorilli, Adriana Gallo, Henry Gorse, Steve Harries

Victoria Hely-Hutchinson, Leyu Li, Toby Marshall Nathalie du Pasquier, Studio H, Sharp & Sour, Paolo Zerbini

PUBLISHER AND EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Dan Crowe

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono andrew@port-magazine.com

ACCOUNTS Charlie Carne & Co.

CIRCULATION CONSULTANT Logical Connections James Laffar jlaffar@thelogicalchoice.com

SYNDICATION syndication@port-magazine.com

CONTACT Ayla Angelos ayla@anima-magazine.com

ANIMA ONLINE anima-magazine.com

TYPEFACE

At Aero and At Haüss Mono designed by Pedro Arilla, available at Arillatype.Studio®

Bradford designed by Laurenz Brunner, available at Lineto

Foundry Gridnik™ designed by Wim Crouwel, available at Linotype

Futura designed by Paul Renner available at Bauer Types

Anima is published by Port Publishing Limited Somerset House, Strand London, WC2R 1LA port-magazine.com

Anima is printed by Park Communications

Registered in England no. 7328345

All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited. All prices are correct at time of going to press but are subject to change. All paper used in the production of this magazine comes, as you would expect, from sustainable sources.

www.anima-magazine.com

014

MASTHEAD

Nathalie du Pasquier

WORDS

The artist Nathalie du Pasquier talks about the things that inspire her is inspired

016

Nathalie du Pasquier PHOTOGRAPHY Alice Fiorilli

(Right) Mesopotamian sculptures from the first half of the third millennium BC

018 Visiting a friend’s studio is always stimulating and inspiring. Pino Guidolotti is a photographer I have known for many years. Now he lives in a small town in the south of Italy and does not make many photos anymore. But he is not only a photographer, he has also always been an incredible artist, building strange sculptures, crazy toys, making beautiful drawings and other things. When I go to the south in the summer and visit him, going to his studio is always a surprise. He takes photos of people, places and things out of his drawers, installing them on the walls, and it is always different. There are his drawings in black and white, the objects he recently made from painted wood, feathers and materials he finds around. The stories that emerge from these juxtapositions are reminiscent of past times but also very exotic. His studio, full of books as well, is like a magic room.

I am a painter; I live in Italy. Italian Renaissance paintings are what I first looked at when I started painting. There are many painters I love from that period, but I chose this painting by Fra Angelico because it is so peaceful and, in this moment, I need to be reminded of peaceful things, the Tuscan light falling from the sky, the small flowers on the ground. This painting is not big, it is one panel of a predella under the story of San Nicola. I think what strikes me here is the architecture, like a series of big objects or theatre props that are enough to place the actors in their situations. It is very simple; nothing is useless, and it is also very descriptive and clear. The two rooms opening on the right and on the left of the painting are illuminated enough to see what happens inside. It is a bit like a theatre, and I think that is what I find inspiring.

The studio of Pino Guidolotti

(2) A painting by Fra Angelico

(1)

(2)

(1)

The studio of Pino Guidolotti

(2) A painting by Fra Angelico

(1)

(2)

(1)

(3)

I don’t remember when I first encountered these two figures, maybe in 1988 when I was reading the Epic of Gilgamesh. I find them amazing, these big eyes probably staring at very far away stars, deeply concentrated and at the same time lost. Their tiny hands holding I don’t know what. I think they are a man and a woman. In the book where I found this picture, they say they are two gods, but for me they are very human and seriously curious about the unknown. I think I feel like them when I forget about where I live.

(4) Hand-made books

I like books, I like making books. Before the invention of print, books were hand made. Also, after Gutenberg some precious books were still made and illustrated by hand. There are some beautiful medieval books which are very much in my heart, but here I have chosen two pages from a Persian book. There are no images, only framed calligraphy. I do not understand the meaning of what is written but these abstract pages remind me how the art of inscribing messages on a page is important and in fact can be enough.

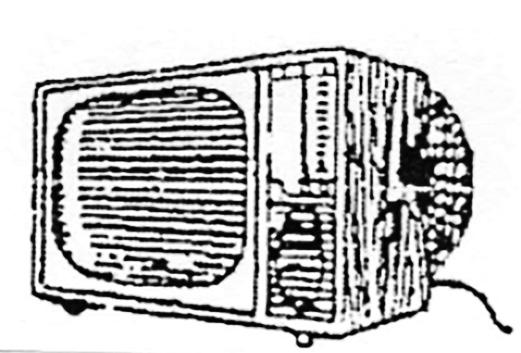

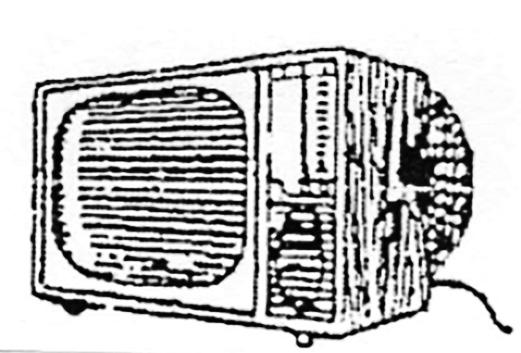

(5) The future

This is a photo in an old children’s sci-fi book. I like the big computer with all the buttons, the nylon pink hair of the girl operating the machine, which is so different from what we use now. But still, that is the future. The future inspires me. In my work there is always the future, not the past, the future made of all the past digested but we don’t know for what purpose.

019

Mesopotamian sculptures from the first half of the third millennium BC

NATHALIE DU PASQUIER

(3)

(5)

(4)

(6)

These types of paintings are named Chaekgeori and Chaekgado, I think they had a kind of influence on me. I saw the first ones before I became a painter in 1986, in bad black and white photocopies and I was immediately interested by these compositions made only of objects. Chaekgado are paintings representing pieces of furniture, like big shelves in which heteroclite objects are installed. At the time, in 1986 I was still working as a designer and I liked the way the elements were represented in axonometry. I liked the exotic aspect of the precious objects displayed with piles of books, all very regular. In the Chaekgeori paintings the objects and furniture are combined on one stand, they are like a pile of objects making one big object. I think at this point in my life they inspire me, or at least I remember them when I build my “constructions”, putting together elements from different periods of my work and new paintings.

(7)

This book was given to me for Christmas this winter by a good friend. It is a book of Mediterranean recipes and it is organised by ingredients. I cook mostly vegetarian. It is enough to open the book and find an unusual way of preparing things I am used to cooking in more or less the same way every time. It is a very thick book, and recipes are illustrated with small photos where food is displayed on nice plates. It also tells you how long to spend on the preparation – many do not require much time which is also very inspiring!

(7)

020

(6)

Korean painting

A big cookbook

AFROSPORT, a new publication from Mami Wata, spotlights Africa’s history and global influence through sport and design

022

WORDS Ayla Angelos

023

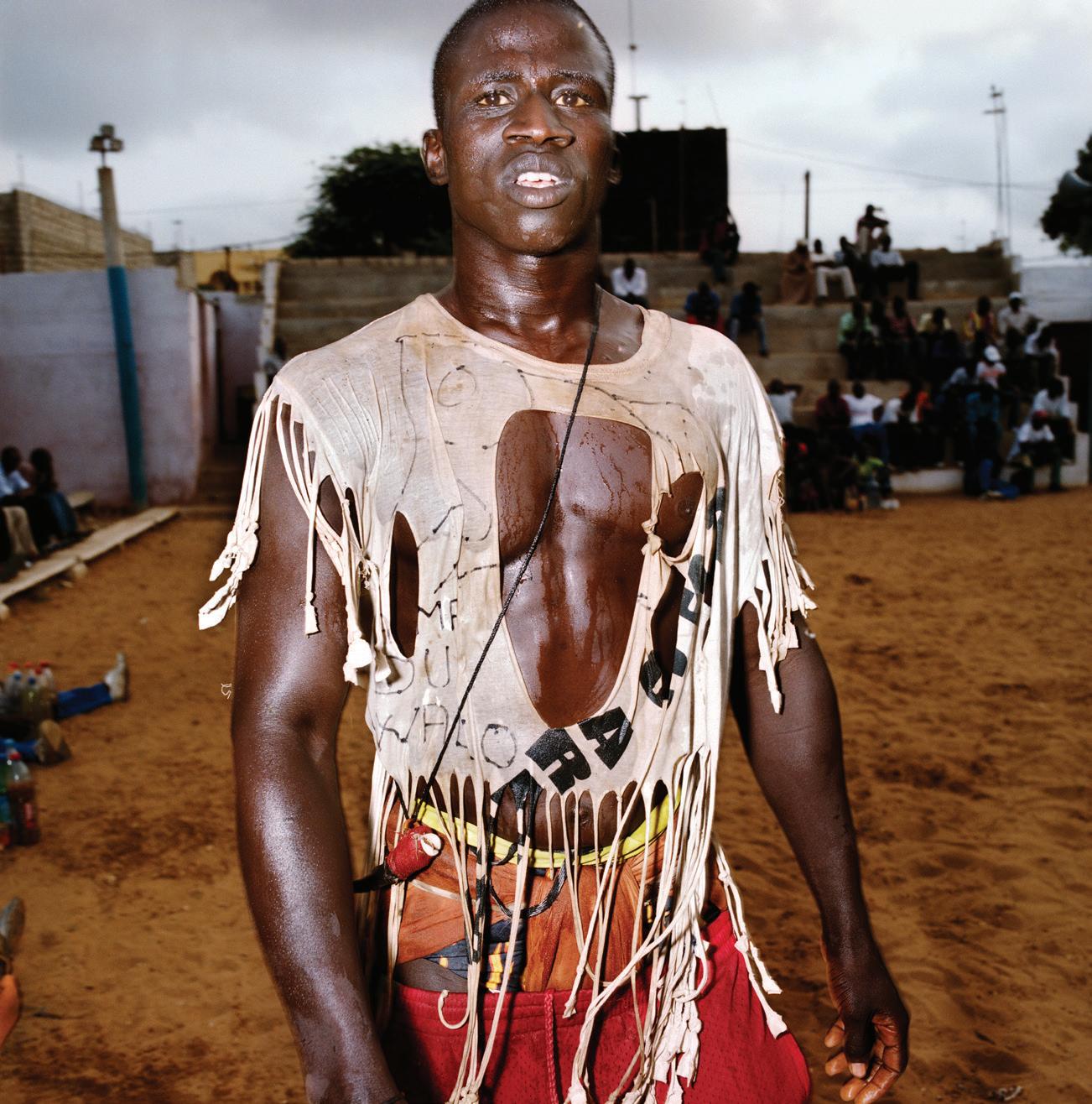

(Above) Photography Eric Lafforgue

024

(Right) (Below) New Year’s Eve Gusheshe spinning in Botshabelo, Free State, South Africa, Dec 31 2011. Photography Jo Voets Photography Christian Bobst

(Below right) AFROSPORT book cover. An athlete is photographed playing donga, a stick fighting sport from Ethiopia

Launched in Cape Town in 2017, Mami Wata is a clothing brand that combines a powerful graphic aesthetic with a commitment to investing in local production and communities. The name – West African pidgin for water spirit – reflects Mami Wata’s roots in Cape Town’s surf culture, which is not a western import, but a sport that can be traced back to at least 1640 in what is now Ghana and is better understood as the revival of an ancient practice. Mami Wata aims to use African-grown cotton, and its products range from an R800 rand T shirt – about £32 – to a £500 medium-length surfboard. The brand describes the simple graphic design that decorates the board as inspired by the patterns found on walls built in Ndebele communities, which relate to tribal identity. According to its site, “many consider these designs to be modernist but in actual fact they predate modernism by many thousands of years”.

Mami Wata was started by Andy Davis, Nick Dutton and Peet Pienaar, who recruited Selema Masekela, the American-born son of the famous South African jazz musician Hugh Masekela, as an investor and collaborator. Selema Masekela is a filmmaker, sports reporter and producer who encouraged Mami

Wata to publish its first book, AFROSURF, which celebrated the energy and optimism of African surfing. It has been followed by a second book, AFROSPORT, which takes a wider view. Through the lens of sport, the new book presents a powerful celebration of Africa’s distinctive contribution to design and culture. “The world in general knows very little about Africa and why certain things look the way they do,” says Mami Wata’s creative director Peet Pienaar. “Western designers think that everything that happens in Africa is vernacular and that African designers are behind in some way. Western design isn’t the default.”

As a discipline, African design is rooted in centuries-old traditions and a style that encompasses a broad range of techniques, reflecting the cultural, historical and socio-economic contexts of its diverse regions. From ornate cave paintings in South Africa’s Cederberg Mountains to masks produced by cultures across the continent, its histories are as varied as its communities. For centuries, fractals have been used in Africa as a design tool across sculpture, architecture and pattern making, even in the creation of sports jerseys and uniforms. In 2018, South African researchers confidently dated the

criss-cross patterns they found on a fragment of rock in the Blombos Cave as having been carved an unimaginable 77,000 years ago. They interpreted them as representing the earliest-known example of abstraction used as a form of graphic communication. Despite these ground-breaking innovations, African design has been marginalised within the global discourse. AFROSPORT isn’t going to change all that on its own, but it makes a strong case.

“A lot of design schools are pushing African designers to become western designers because that’s the default,” Pienaar says. “When African designers start including cultural elements into their designs, it’s immediately seen as vernacular. All of us who are culturally ethnic are excluded.” Without knowledge and awareness of its history, this perpetuates the stereotype that African design is only synonymous with animal prints and Sahara aesthetics. Whereas, in reality, it is a dynamic and playful discipline that’s rooted in connectivity and a shared post-colonial mindset. AFROSPORT is more than just a celebration of African design and sports culture – it's a call to action by placing Africa at the centre. “The world is going to be influenced by Africa,” says Pienaar. “It's very important that people start being more aware of what's happening. It's time that we read more about Africa.”

With its deliciously iridescent coruscating graphic cover, fuelled by reflective pinks and almost-lilac blues, the book takes a seductive rather than a didactic approach. A thick, boxy border directs the eye to a striking photograph taken 14 years ago by Eric Lafforgue. In perfect central alignment, the subject’s head is protected by a helmet of woven knots, his lips pursed as his eyes fire off into the distance. He’s in the midst of a game of donga, a stick fighting sport hailing from Ethiopia. Inside the book, Robert Wangila, a professional boxer from Kenya, raises his fists as he poses triumphantly for the camera (the photographer remains unknown). Wangila won a gold medal at the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul. His pendant hangs proudly around his neck, decorated by Giuseppe Cassioli’s portrayal of Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. She holds a winner’s crown and palm in her hands, while the Colosseum is depicted in the background – the top right corner is where the name of the host city and Games numeral sits.

do”

026

(Right) (Above)

Image of Robert Wangila, who won a gold medal at the 1988 summer Olympics in Seoul. Photographer unknown

Photography Laurent Gaudin

“The general world knows very little about Africa and why certain things look the way they

AFROSPORT

028

(Above) Photography Laurent Gaudin

029

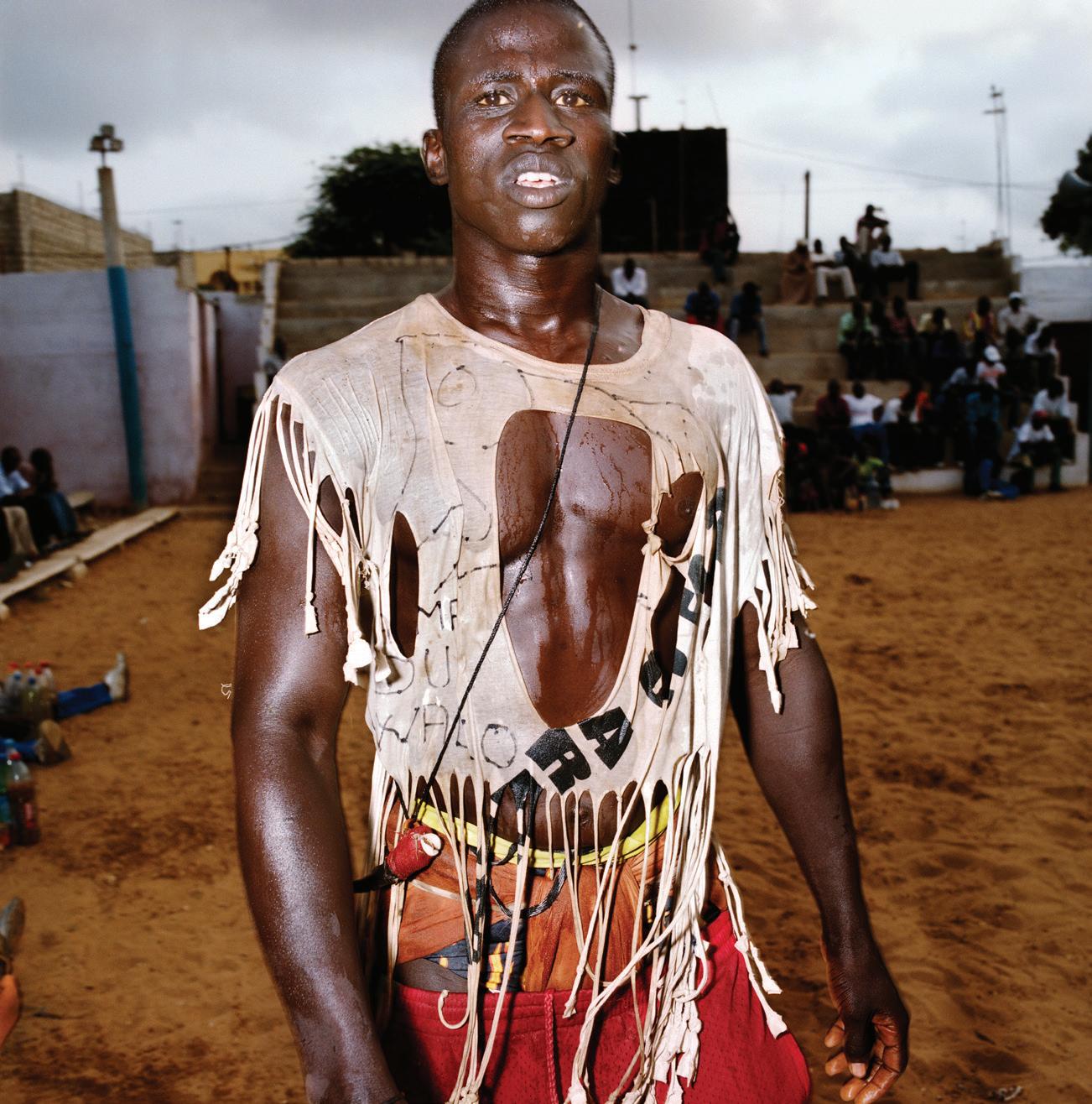

(Above) Serer wrestler before his fight at the Adrien Senghor arenas. Photography

AFROSPORT

Laurent Gaudin

The relationship between sport and design has long been dynamic and mutually reinforcing, driving culture, economy and social development. Its role is highlighted through AFROSPORT’s 150 photographs from image-makers such as Pieter Hugo, Nana Yaw Oduro and Kyle Weeks. It documents significant events including the Rugby World Cup Trophy Tour in Cape Town last year, and the moment that the Senegalese football team won the Africa Cup of Nations for the first time in 2022. In a bustling, smoky image, the team are portrayed raising their trophy in a gesture of victory in the crowded streets of Dakar. The book highlights sports from boxing to motorbike racing, as well as some that are more traditional or less well known. This includes dambe fighting, a martial art from the Hausa people of Nigeria, and laamb wrestling, a Senegalese fusion of traditional wrestling styles that has overtaken football in popularity. Contributions from writers, artists, skate brands, filmmakers and sports figures including Joakim Noah, Didier Drogba and Gerard Akindes each offer their perspective on how sport and design has played an influential role in their lives, and the development of Africa.

“There’s a strong new language in Africa that's happening now and it’s completely mixed up with western culture”

Casting a wide net from the past to the present day, AFROSPORT portrays Africa’s identity amidst a shifting societal landscape. Driven by the continent’s rapid growth in population, the so-called youthquake that has given Africa the largest percentage of people under the age of 25 in the world, a new visual language is emerging. Demographic change is both a challenge in its effect on unemployment rates, access to education and healthcare, and an opportunity. A youthful Africa offers a vast pool of creativity and innovation. If effectively tapped into, it has the potential to drive economic growth, placing the younger generation at the front of visual culture.

At the same time, globalisation and the instant communication of social media has sparked a new kind of interaction between the West and the Global South. Football is inescapable. In Cape Town and Johannesburg, people wear Chelsea jerseys embellished with the symbols of western consumerism, which have been co-opted into everyday clothing. Traditional sports, such as donga, are attracting more attention and sporting talents no longer need to leave their homes to start a career. African culture has

AFROSPORT

(Left) (Below) The Gris-gris Wrestlers of Senegal. Photography Christian Bobst

A wrestling tournament held on a basketball court at the Olympique de Ngor stadium, Senegal. Photography Christian Bobst

(Above)

032

(Right) Orlando Pirates Photography @kgotmotso_neto

034

(Above)

(Right) Fans attending an Orlando Pirates football match, wearing the team's signature skull and crossbones. Photography Rogan Ward

The Orlando Pirates is a football team based in Orlando, Soweto

assimilated western influences, and the line between the two has eroded. The colonial powers had originally introduced European sports as part of their supposed civilising mission and saw them appropriated by their unwilling subjects. Something similar is happening now. “There's a strong new language in Africa that's happening now, and it’s completely mixed up with western culture,” says Pienaar. “A lot of people think that African designers use symbols as appropriation or as aspiration. But the Nike logo, for example, holds a completely different meaning, since it isn't available in most African countries. People start seeing the symbol appear on jerseys and at football matches, but they don’t associate it with the product. There’s a new language developing.”

“There’s an incredible playfulness in African design, especially in sport”

Okoh, a Ghanaian teacher, artist and hockey player, designed Ghana’s national flag in 1957 with three colours – green, yellow and red – plus a black star. The latter is identified as a symbol for the emancipation of Africa, adopted first from the flag of Black Star Line, a shipping line established by Marcus Garvey which ran from 1919 to 1922. When other former colonies became independent, they opted for the same colour palette in solidarity.

It could also be said that Africa’s unique visual language – one that exudes a sense of boldness, storytelling and shared values – matured once the continent became independent in the 60s. Theodosia Salome

The design ethos of AFROSPORT embodies this spirit, characterised by bold colour palettes and a non-linear approach to layout and composition. It avoids formal grid layouts in favour of organic, free-flowing aesthetics, nodding to the lively nature of the design language. This becomes evident throughout the graphics, designed by Pienaar and the Mami Wata team, and in the stories that unfold throughout the pages. One such example is that of The Orlando Pirates, a football team based in Soweto,

035

AFROSPORT

(Left) (Above) South African football culture, photography @kgotmotso_neto

Kaizer Chiefs Football Club are a South African professional football club based in Naturena, Johannesburg

(Left) (Above) South African football culture, photography @kgotmotso_neto

Kaizer Chiefs Football Club are a South African professional football club based in Naturena, Johannesburg

AFROSPORT

(Above) Timeline of African history, courtesy of AFROSPORT

Orlando. Formerly known as the Orlando Boys Club, the teenagers who originally formed the club in 1984 eventually broke away to join Andries ‘Pele Pele’ Mkhwanazi, a boxing instructor who encouraged the genesis of a new football club in 1987, dubbing them ‘amapirate’, which means ‘pirates’ in isiZulu. The team took a name that had been intended as an insult, and created a logo and identity that resonated with their defiance – a monochromatic skull and crossbones. It refers back to the buccaneering days of Caribbean piracy, but also to the iconography of contemporary American football. Pienaar finishes, “there’s an incredible playfulness in African design, especially in sport.”

(Above) Ghana BMX, courtesy of AFROSPORT

(Above) Ghana BMX, courtesy of AFROSPORT

041 AFROSPORT

(Above)

(Left) Photography Rogers Ouma

Tour D'Afrique, the original transcontinental journey and flagship bicycle expedition. Photography Chris Keulen

A △○−☺⤓♡↘■↖ language ♡↘■↖ ☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■↖ △○ ↘■↖ without ⤓♡↘■↖ ☐△○−☺⤓ words

☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■↖ ☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■⤓ From ancient hieroglyphs to the Olympic Games and architectural signs for the deaf community, pictograms have become a powerful tool for shaping our daily experiences, fostering kinshipy and speaking volumes without uttering a single word

WORDS Ayla Angelos 042

You’ve been awake since dawn and you step into the airport, a passport clutched in one hand and a coffee cup in the other. The atmosphere is buzzing with fellow bleary-eyed travellers, and the frenetic pace feels dizzying, as if you’re working your way through an obstacle course. Your gate number is called, and each hurdle becomes harder and more challenging – you leap over an abandoned suitcase, swerve a puddle of cola and squeeze through the duty-free minefield. And finally, you spot an arrow-bearing icon guiding you through the maze. A simple silhouette of an aeroplane signals the way to check-in counters, while a suitcase icon beckons towards baggage claim.

You’ve made it to the gate, and you couldn’t have done it without the humble airport pictograms. The visual cues have become a universal language, embedded so deep into society that most may not even notice their impact. They melt into walls, signage and doors as if they were part of the furniture, soaking up as much information as possible to forge their own ecosystem of graphics and illustrations. As travellers, we become unwitting participants in this non-verbal dialogue, each arrow and icon guiding us through the labyrinth of terminals, replacing the chaos of the airport – and many other places of civilisation – with an experience that prioritises a straightforward journey above anything else.

“More than ever before, we read and understand the world around us in images”

Pictograms have long served as a powerful and versatile means of communication. The earliest instances trace back to ancient civilisations, engraved or painted on cave walls. The Egyptians used hieroglyphics, a form of pictogram writing, to convey a wide range of concepts and ideas, while the Sumerians employed pictograms on clay tablets for record keeping. In ancient China, oracle bone script featured pictographic characters inscribed on bones and shells, which were used as a method of pyromantic divination, the practice of using fire or flames to seek knowledge of the future. In the modern era, pictograms have become standardised and widespread, particularly in public spaces and transportation systems. Road signs, for instance, employ a suite of symbols to convey warnings, prohibitions and directions. They do, however, have national variations; Margaret Calvert and Jock Kinneir gave Britain a particularly impressive set as part of their work on a new road signage system. And some signs have turned into graphic fossils – railways are still being represented by long-vanished steam locomotives, and digital speed cameras by traditional-looking analogue cameras. The rise of the emoji is a new form of communication that conveys emotions and expression through a singular icon, albeit one that tends to offer a literal interpretation.

043

(1) Fencing, copyright ©1976 by ERCO, www.otl-aicher-pictograms.com

(1)

Pictograms have played a significant role in global events, notably the Olympics, which has used them as part of its branding. Since their inception at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics – the first time a graphic visual system was used to communicate the games without words –pictograms have served as a way to convey information, transcend language barriers and allow athletes, officials and spectators from various linguistic backgrounds to easily identify and understand the different sporting disciplines. Kamekura Yusaku developed a modernist emblem and a set of 39 informational icons appearing stencil-like and bold, a cohesive identity wrapping the games tightly together.

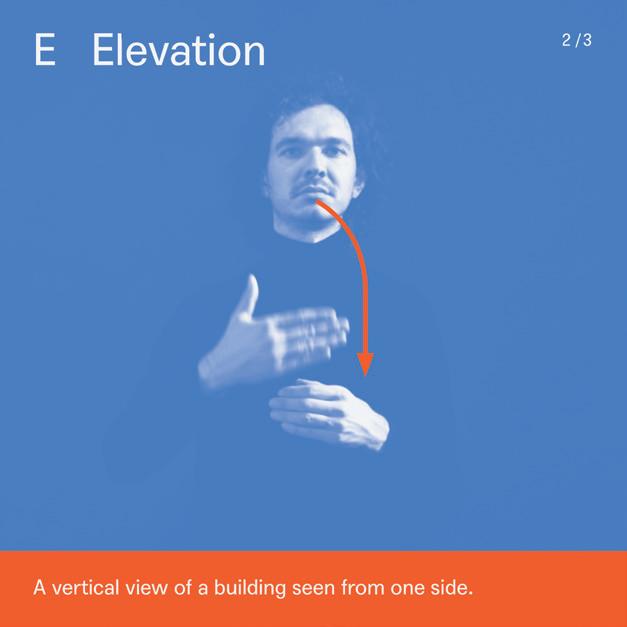

Yusaku’s pictograms were a turning point. In subsequent games each Olympic host city has tried to put its own creative stamp on the design of pictograms with greater or lesser degrees of success. The most authoritative example is Otl Aicher’s work for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich.

(Image) Water polo, copyright ©1976 by ERCO, www.otl-aicher-pictograms.com

A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS 045

Aicher attempted to continue the modernist tradition of Bauhaus-era functionalism in post-war Germany. His wife’s sister had been one of the White Rose group, whose resistance to Hitler led to their murders. As a memorial to her, and as an institution dedicated to developing a humanistic approach to design that would reinforce a democratic society, they established the Ulm School of Design in 1953. It helped to create the refined language used by Braun consumer electronics. Aicher himself designed a font that he named Rotis, and an identity for Lufthansa. His most enduring legacy is his work for the Olympics. He created a comprehensive visual identity system that included pictograms, colourful graphics and typography. The identity showcased Aicher’s belief that design could foster communication across cultural and linguistic barriers; it reflected simplicity, clarity and functionality, and rejected the ornamental excesses associated with Nazi propaganda, embracing a more rational and democratic approach to design. As such, the pictograms displayed geometric shapes and a minimalist approach, all the while conveying the dynamic movements inherent in each sport. Whether it was the arc of a diver, stride of a runner or swing of a tennis racket, each pictogram captures the essence of the sport it represented with fluid, energetic lines that remained consistent and accessible throughout. “The copyright-protected system is characterised by a strict grid and consistent simplification,” says Kai Gehrmann, who’s responsible for the global licensing and further development of the Otl Aicher pictograms. “Each symbol follows standardised design rules, comparable to the grammar rules of verbal language.”

While devising the system, Aicher turned to the iconography of the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, seeking to devise a suite that was less pictorial and more consistent. He ensured that the essence of each pictogram was captured in a straightforward and comprehensible manner. This system, which became known for its clarity and recognisability, went on to define a whole design epoch; it continued to expand since the 70s and now includes more than 750 pictograms that go far beyond sport. “More than ever before, we read and

understand the world around us in images,” says Gehrmann. “Today, pictograms are an integral part of the design of digital interfaces, for example, which should be understandable globally regardless of language. In this respect, the fields of application are even more diverse today than they were during Aicher's lifetime.”

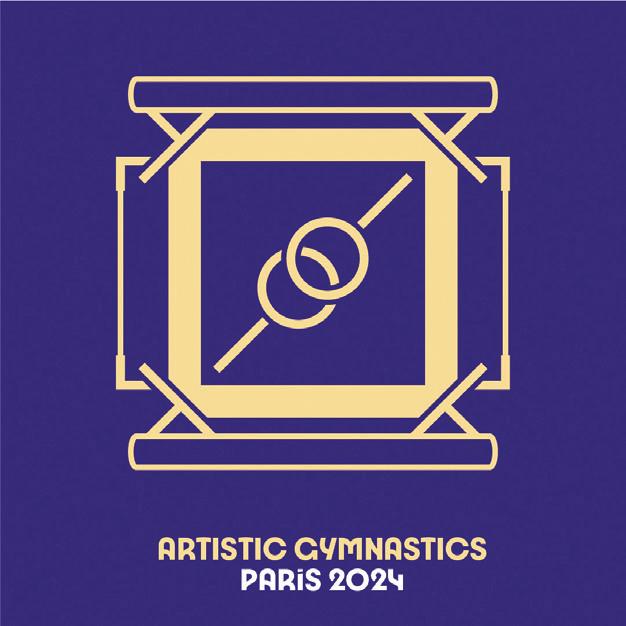

And while many continued to embrace this ethos, others have sought to challenge it. For the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games, this new set of icons marks a departure from previous styles, showcasing a wilful break from tradition (or from Aicher).

Led by Joachim Roncin, head of design for Paris 2024, and in collaboration with agency W, the suite of 62 pictograms are unconventionally dynamic and expressive, capturing the action and excitement of each sport, and the buzzing atmosphere of the Games. Bendy moves of a gymnast and the powerful strokes of a rower are forged into athletic, almost liquid lines and valiant forms, cradled in vibrant colour palettes with a heavy use of purple. Each icon is composed of three graphic elements designed around an axis; eight of which are shared between the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

While Aicher’s pictograms were rooted in standardisation and clear communication, the Paris 2024 iconography bears a more idiosyncratic approach that is sometimes hard to interpret. President Tony Estanguet referred to the pictograms as “badges of honour” that symbolise the wearer’s belonging to the chosen sport family, embodying a sense of belonging and community. “A pictogram is also a symbol that is collectable,” said Estanguet at a pictogram launch event. “When you’re an athlete, you're proud about showing off the pictogram of your sport – pins, T shirts… I remember collecting those things.”

The Olympics – and sports in general – wasn’t the first nor only industry to combine pictograms in a systematic approach.

046

(3) (2) (1) (4)

Fencing, copyright ©1976 by ERCO, www.otl-aicher-pictograms.com

(5) (6)

047

(Images) For the Munich Olympics in 1972, Otl Aicher devised a comprehensive system to define each sport with a maximum economy of means, including torch race (1) bobs (2) powerlifting (3) mountain biking (4) hurdling (5) and aerial skiing (6)

A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS

(Images) Pair-skating (1) and triathlon (2) Water polo, copyright

(1) 048

©1976 by ERCO, www.otl-aicher-pictograms.com

A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS (2) 049

“A

050

pictogram is also a symbol that is collectable”

(Images) Paris 2024 Summer Olympics, credit Paris 2024

051 A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS

052

(Images) India State Election Symbols, copyright ©2018, Official Website of State Election Commission, Government of Puducherry, India

In India, when millions of eligible voters go to the polling booths for the elections, their vote is cast with a symbol: a ceiling fan, bungalow, umbrella, bottle, coconut or a mango to name just a few. Most of the symbols were drawn by hand in pencil by the late draughtsman M S Sethi, who retired in 1992, giving the identity of the icons a sketchy and minimalist aesthetic. The symbols appear on electronic voting machines in India, representing the 2,300-odd political parties; they’re published on banners, plastered across rallies, printed on pamphlets and election manifestos. The icons have been part of the process since 1952, the year India held its first election after the country gained independence from British colonial rule. Because 80 per cent of the population was illiterate, they decided on a foolproof and easy way for voters to be able to identify their chosen parties.

Just like the parties, which ebb and flow with society and popularity, the list of symbols is a work in progress. By 2004, there were fewer than 10 symbols for candidates to choose from – including the ceiling fan, telephone, air conditioner and dish antenna. Now, the Election Commission of India (ECI) maintains thousands, representing everyday life in India. A large portion of these are items of clothing or grooming utensils, many are household items, a couple are transport vehicles and there are just two animals, the elephant and the lion. These are the last remaining on the list due to complaints around ill-treated live animals being used in the rallies. The Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party (Goa), the Hill State People’s Democratic Party (Meghalaya) and the All India Forward Bloc (West Bengal) have chosen the lion, yet, of course, won’t be able to rally with their real-life mascot. In 1991, the election commission ruled out using fauna as a symbol, too, due to concerns from activists who feared people might attack a creature if it embodied the symbol of an opposition.

Many of the symbols may seem curiously abstract, the nail clippers for example, but they don’t just represent a political party. They elicit the transformation of India from more rural depictions like a plough, cow and cart, to symbols like a tractor, truck and electric pole, then a laptop, computer mouse and USB stick. The symbols are made to be neutral, yet equally bear weight with emotional appeal and their ability to be relatable. And once they’re chosen, or ‘reserved’ by a party, they cannot be used by another again. Despite their rough and pixelated appearance, the Indian election symbols are a powerful and striking example of the part that pictograms can play in national life.

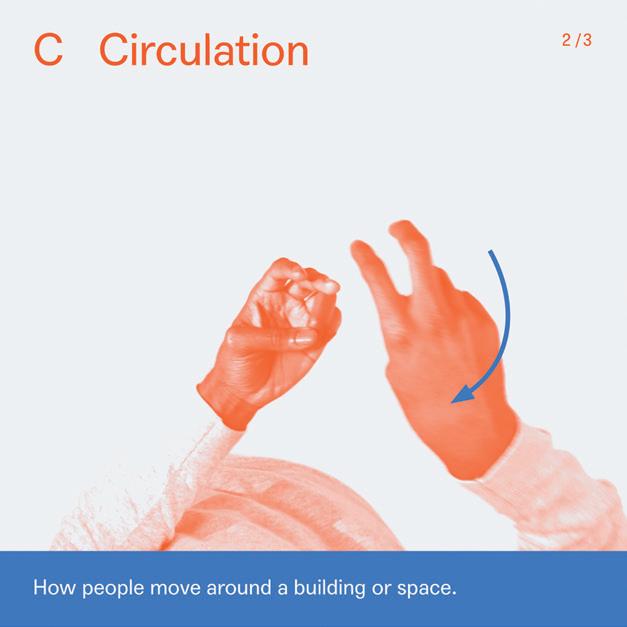

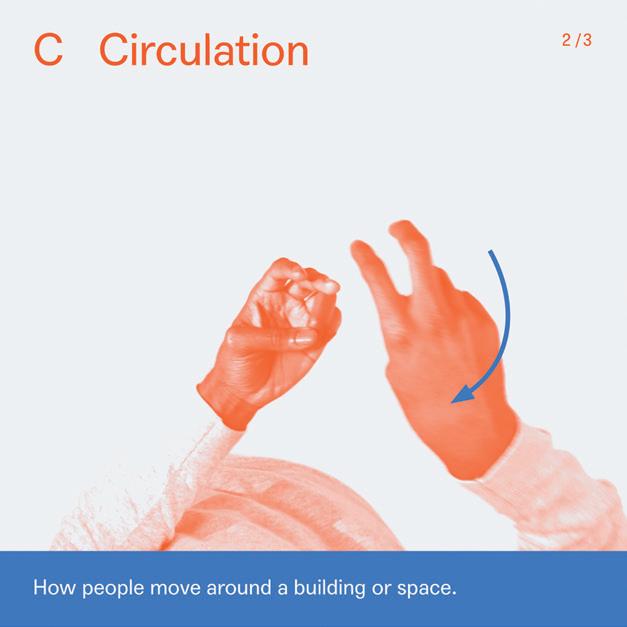

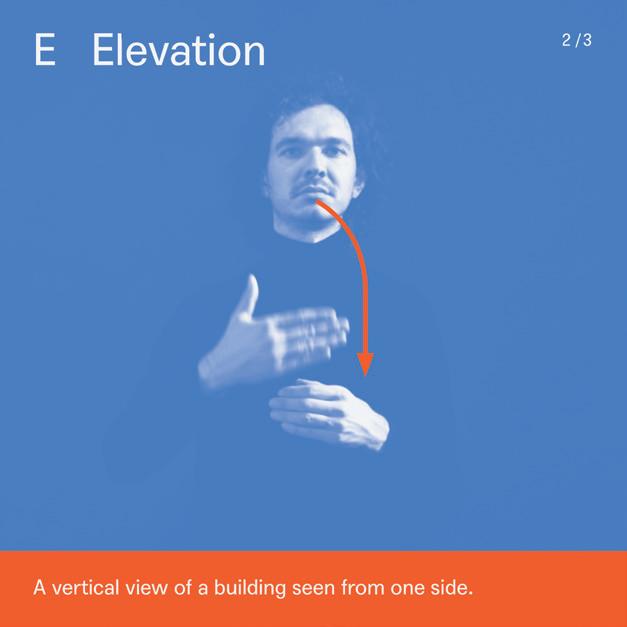

Sign language might be understood as another form of pictogram. Chris Laing, the founder of Deaf Architecture Front (DAF) and Signstrokes, is making

053 A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS

054

(Images) India State Election Symbols, copyright ©2018, Official Website of State Election Commission, Government of Puducherry, India

055 A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS

significant strides in promoting inclusivity and accessibility by developing signs within the field of architecture. In his research, he found that fewer than 15 deaf people are currently training to become architects in the UK. DAF aims to address the challenges that they face by sourcing interpreters, obtaining learning support and translating specialist terminology into British Sign Language (BSL). Laing also launched Signstrokes to convey architectural concepts.

“Pictograms are used as learning tools in education settings, both for young deaf children aspiring to become architects, to students at university and those who want to gain an understanding of the language used in architecture”

Laing, an architectural designer who is deaf himself, established both companies in response to the barriers he faced throughout his career. “I had to create and use ad hoc signs with every interpreter that I worked with, as there was no corpus of terms for architecture that was readily accessible,” he says. “Facing challenges like this can be very isolating.” After meeting a fellow student who was facing a similar experience, they both aligned on a standardised set of terms and initiated the launch of Signstrokes. With support from Kate Rowley, a researcher in linguistics at Deafness Cognition and Language Research Centre (DCAL), and funding from the architectural practice Haworth Tompkins and the Knowledge Exchange at University of the Arts London, they set up a public workshop to translate the terms into BSL. They followed three strategies – the C handshape, visibility and two signs becoming one – to develop the terms and turn them into a graphic system as part of the Signstrokes archive. “Pictograms are used as learning tools in education settings, both for young deaf children aspiring to become architects, to students at university and those

who want to gain an understanding of the language used in architecture,” Laing says. “It’s a valuable resource for both deaf architects and their hearing colleagues, so as to share knowledge and better communication in a studio setting.”

In some ways, Laing’s visual language can be likened to Aicher’s. It’s visually clear, accessible and universally understood. The graphics have captions and show the content step by step, opening up the language to the deaf community. “Pictograms will play an important role in the future as they represent BSL and other languages in a way that is accessible and inclusive,” he says.

“Aicher was convinced that the clarity and recognisability of pictograms are directly related to the limitation of form and structure to the essentials. Pictograms have a task to fulfil: They enable orientation and understanding. This applies then, now, and in the future”

Growing recognition of the importance of inclusive design practices gives Aicher’s philosophy of a language without words more relevance than ever. “Aicher was convinced that the clarity and recognisability of pictograms are directly related to the limitation of form and structure to the essentials. Pictograms have a task to fulfil: They enable orientation and understanding. This applies then, now, and in the future,” says Gehrmann. “I do not see inclusion/representation and design/aesthetics as contradictory. The right thing that fulfils the intended task is always also beautiful. It is like mathematics. For a mathematician, a functioning formula will always have an aesthetic quality.”

056

057

A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS

(Images) Signstrokes, Chris Laing

A LANGUAGE WITHOUT WORDS

(Images) Signstrokes, Chris Laing

☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■

☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■ ☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■

△○−☺⤓♡↘■

☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■

☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■

☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■ ☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■

☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■

☐△○−☺⤓♡↘■

060

“Pictograms

will play an important role in the future as they represent BSL and other languages in a way that is accessible and inclusive”

061

The nuclear

062

WORDS Richard Brook PHOTOGRAPHY Michael Collins

sublime

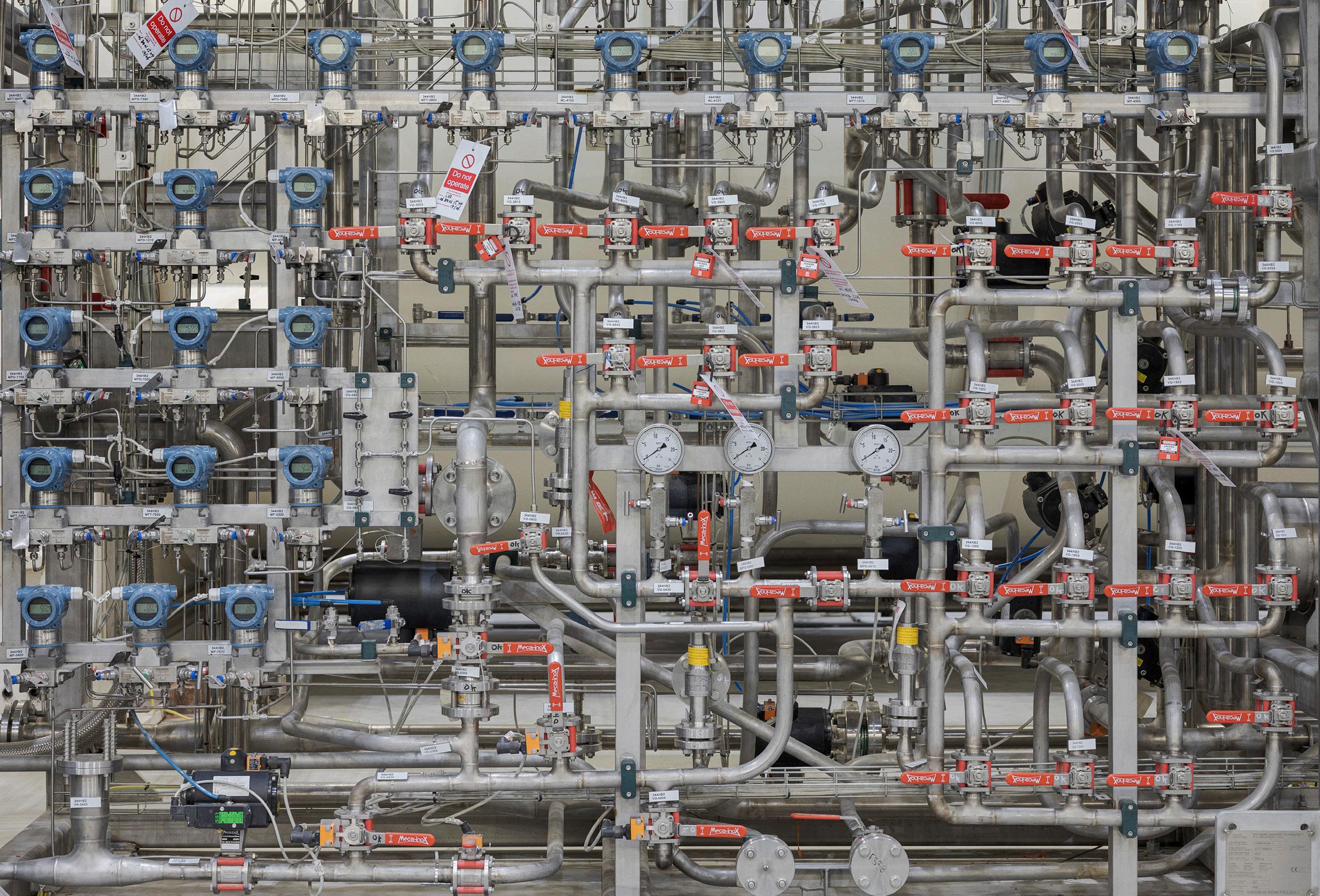

Intermediate Level Waste Store, concrete overpack, No 2, Trawsfynydd, 2021

063

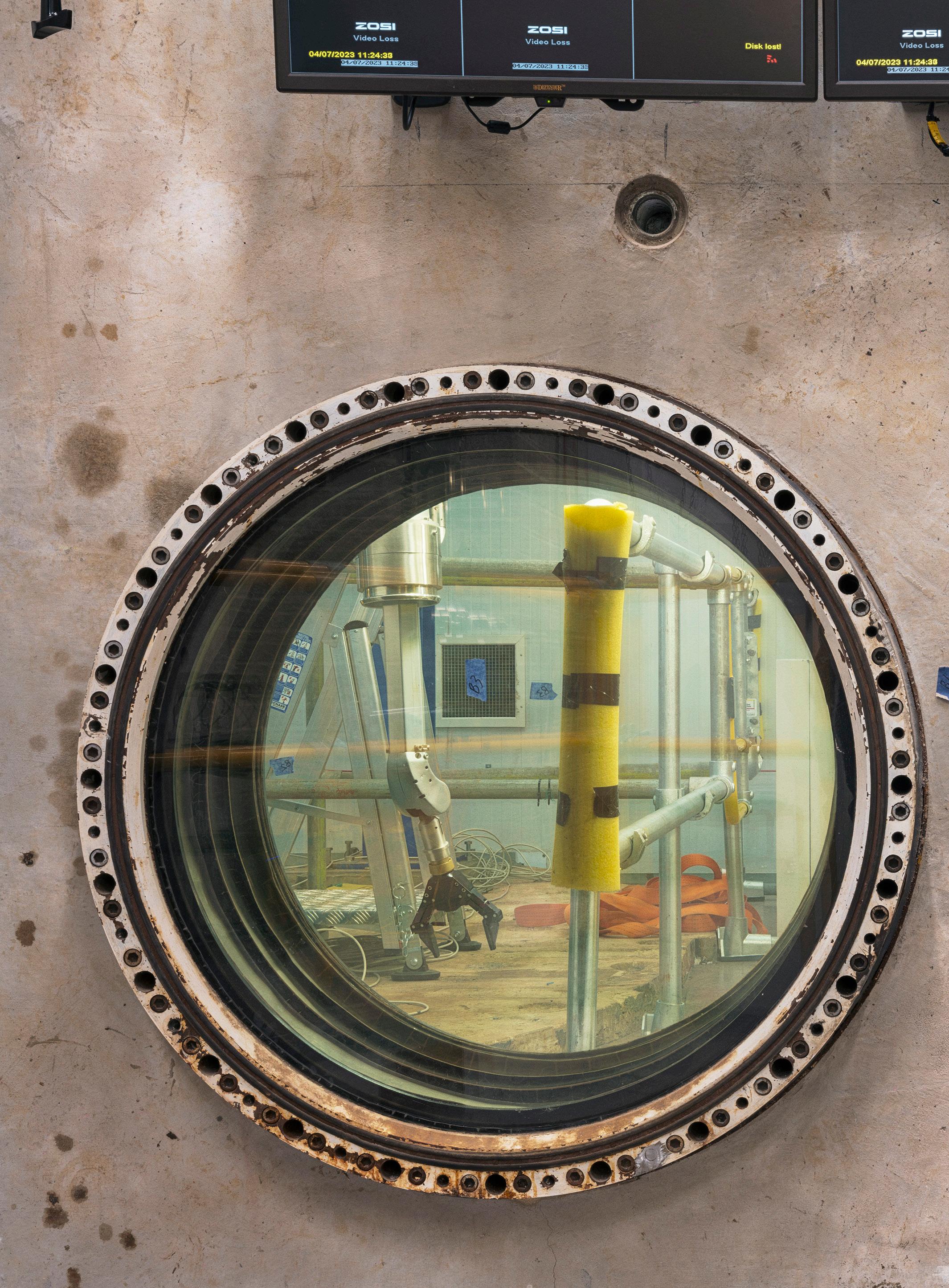

Michael Collins was given access to Britain’s nuclear power stations. His photographs provide an insight into a remarkable series of spaces, once seen as the future of power generation. Some have reached the end of their working lives, and are now in the process of being dismantled. Other are still functioning, while an experimental new generation of reactors take shape, a reminder that we depend on atomic power.

Writing in 1979, the American artist Robert Morris observed that, “in one form or another, technology has produced the monuments of the 20th century: the mines, the rocket assembly buildings so vast that weather forms inside, the Four Corners Power Complex, the dams of the 1930s, the linear and circular accelerators of the 1950s and 1960s, the radio telescope arrays of the 1960s and 1970s, and soon, the tunnel complex for the new MX missile.”1 Morris’ essay was about land art as a form of reclamation in the context of the vast opencast mines that scarred the North American landscape. In observing the monumental status of an industrial legacy, he sought to question how such sites should be viewed in the future – whether they should be afforded heritage status. In so doing, Morris asked his audience to consider the formal and material treatment of redundant structures once they had become technologically obsolete. Should they be obliterated or camouflaged, or was a better strategy to retain some memory of their presence? His argument trod a thin line between ecological sensitivity, consciousness of heritage and the commercial possibilities of commissioned art as a form of amelioration and commemoration.

1Morris, R. (1979) ‘Notes on Art as/and Land Reclamation’. Revised version of a keynote address, July 31 1979. Published in Morris, R. (1993) Continuous Project Altered Daily. The Writings of Robert Morris (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press) pp.211-231.

Morris’ observations are increasingly prescient in Britain today, where the monuments of its post-war modernisation programme have routinely been demolished before their true significance has been explored or understood. Most of the large coal-fired power stations built in the 1960s have now been decommissioned. Many of them have already been blown up, and their sites cleared. The distinctive silhouette of the parabolic cooling tower, the iconic form of power generation, was

064

065

(Below)

065

(Below)

THE NUCLEAR SUBLIME

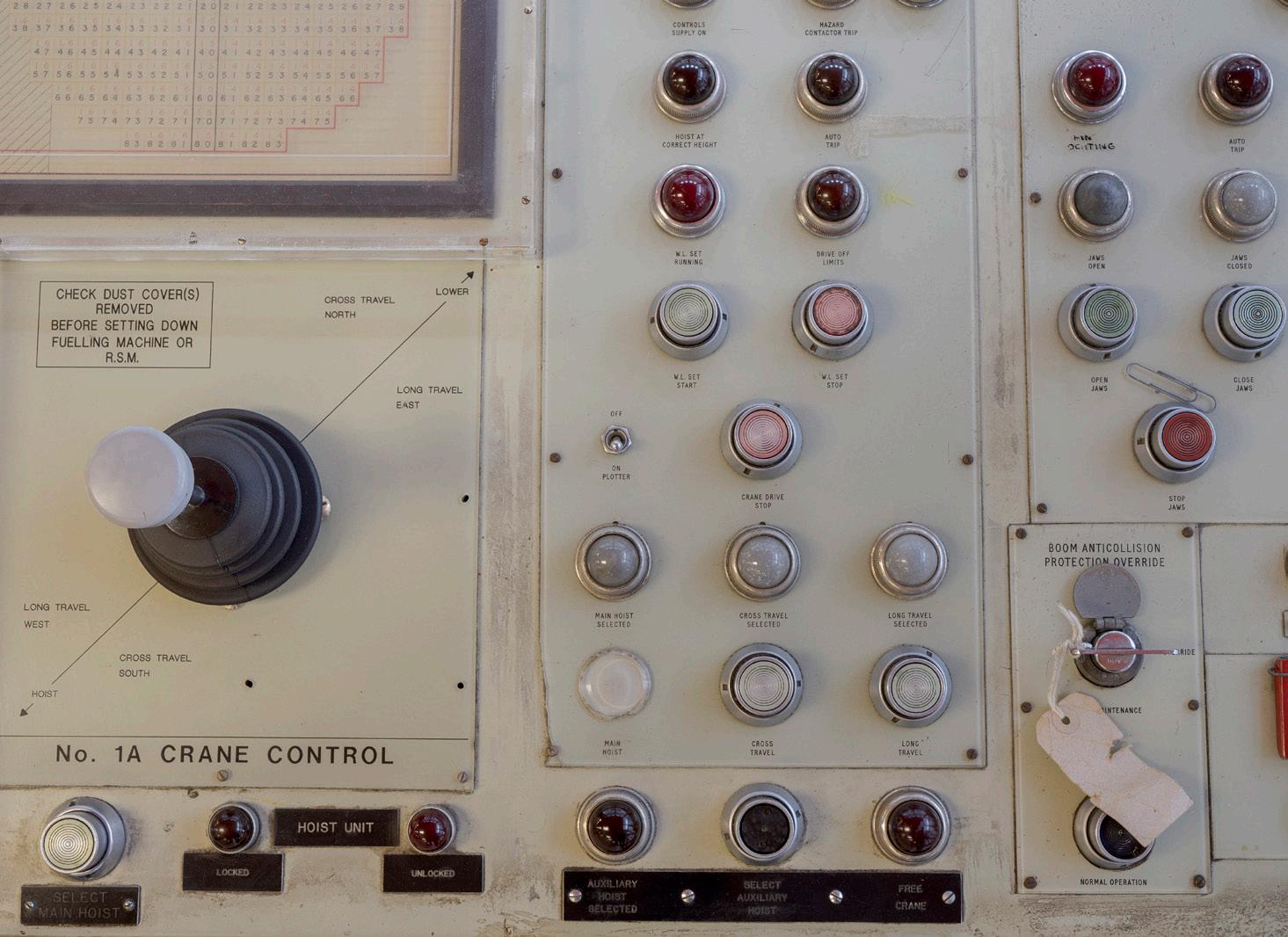

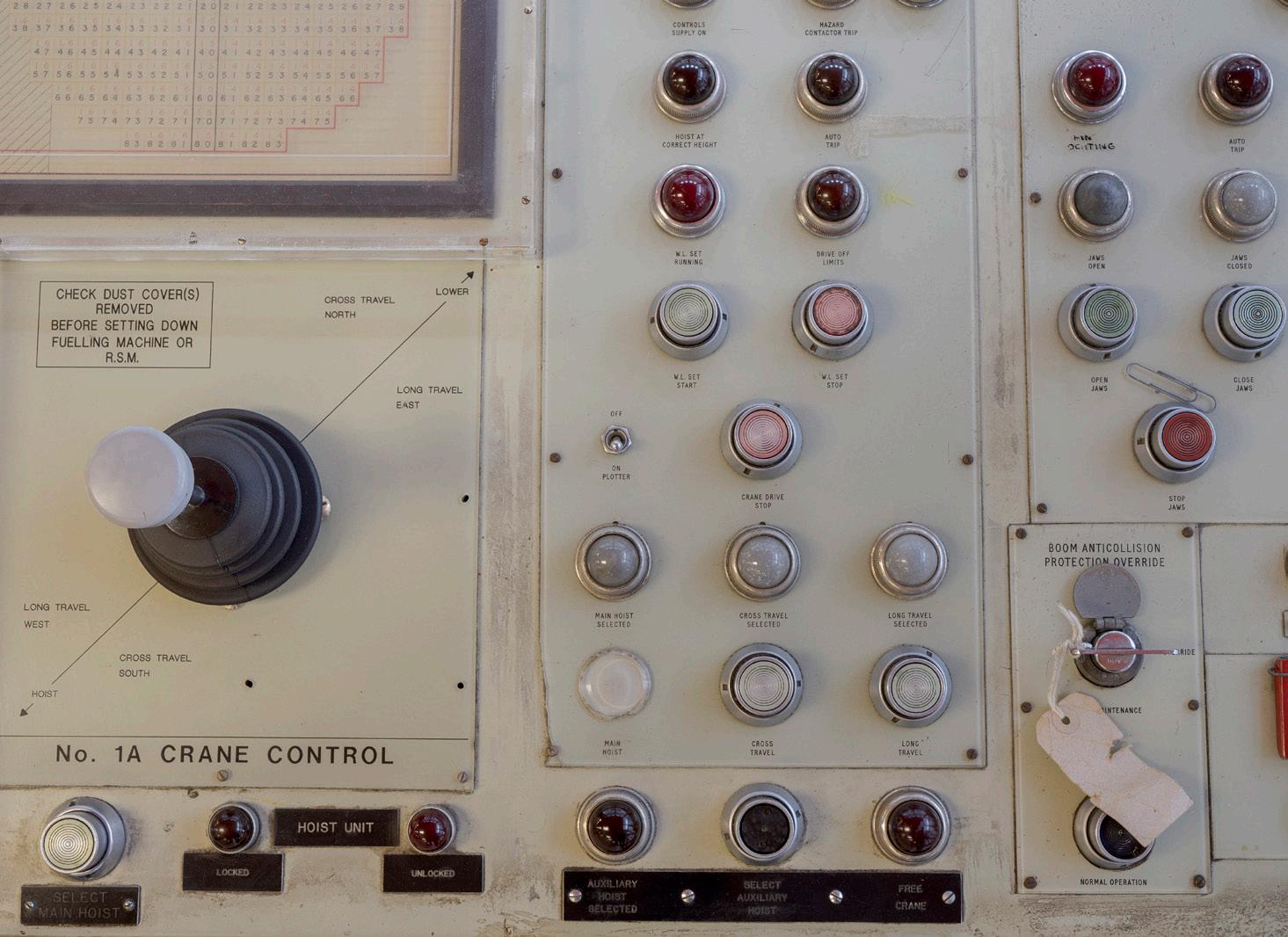

(Above) Gas Circulator Torness 2023 Redundant controls Dounreay Fast Reactor sphere airlock 2023

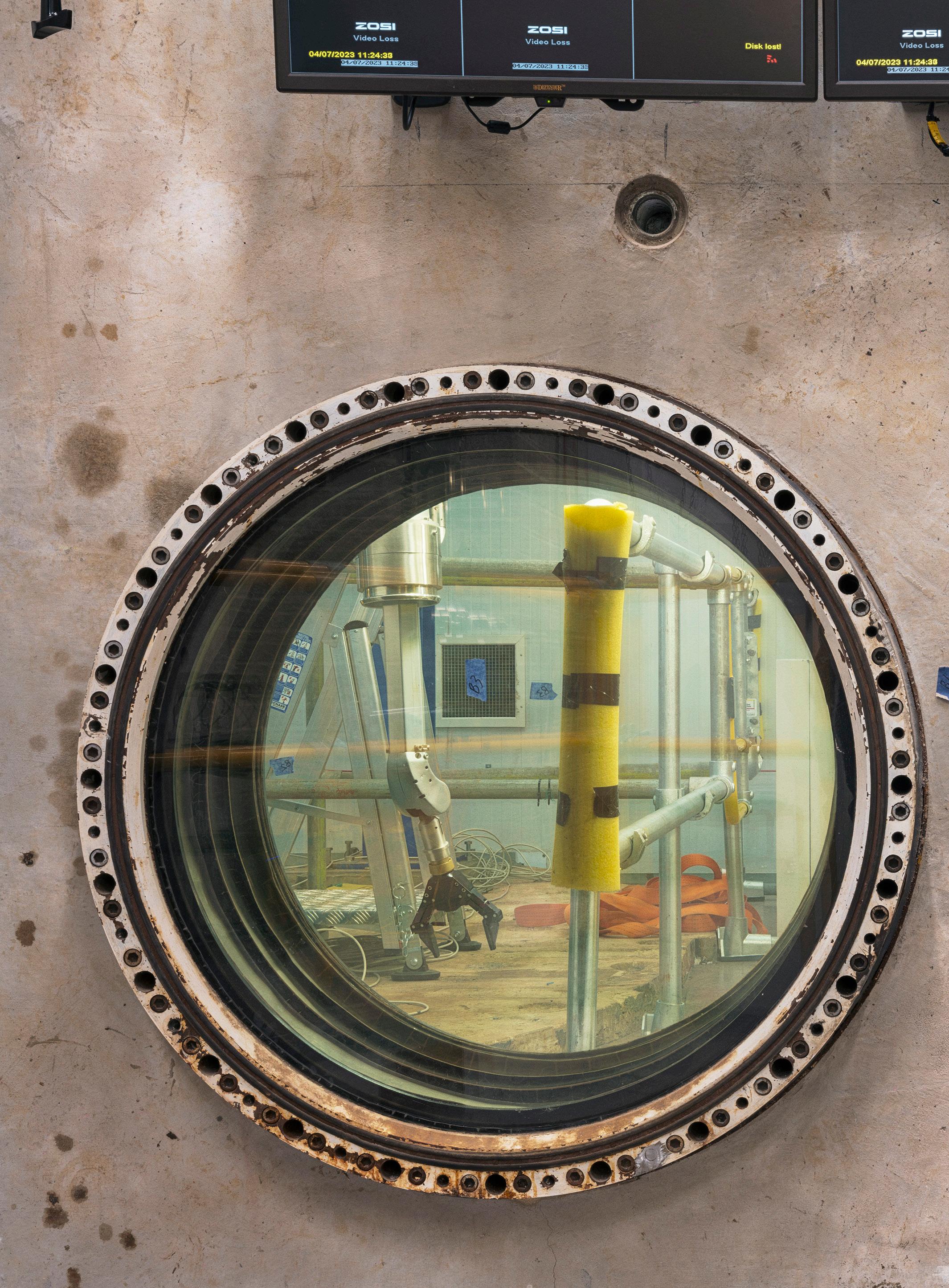

066 (Right) Interior of in-vessel training facility of JET Fusion reactor No 1

066 (Right) Interior of in-vessel training facility of JET Fusion reactor No 1

(Right) (Overleaf)

Obsolete master slave manipulated Reactor 2 Dungeness 2023

Master slave manipulator Dragon Reactor Winfrith 2023

(Right) (Overleaf)

Obsolete master slave manipulated Reactor 2 Dungeness 2023

Master slave manipulator Dragon Reactor Winfrith 2023

indelibly inscribed in the mind’s eye of an entire population and is steadily and purposefully being eradicated from view. The requirement for cooling water-situated power stations on low lying, level land where their massive forms were visible to any traveller on the motorway network, itself expanded in parallel with the capacity of the national grid. Motorways and carbon giants were not the only forms of new infrastructural landscapes that emerged in the post-war decades – where coal fired meant coal fields. The geography of Britain’s nuclear power stations was markedly more remote and almost exclusively coastal. Only Harwell and Trawsfynydd are exceptions.

To the communities that harboured atomic energy production facilities, their impact was absolute. Small settlements expanded to accommodate incoming workers. Supply chains and attendant social, cultural and essential provisions tied entire families to nuclear employment, amongst the spheres, domes and oddly cubist forms of reactor halls. In the UK, by 1976, 13, of an eventual 19, nuclear reactors were connected to the national grid from 11 sites. The first was Calder Hall at Sellafield in Cumbria, which went onstream in 1956. The most recent nuclear power station in Britain is Sizewell B, which opened in 1995. It was the year in which nuclear-generated electricity peaked at 25 per cent of the total supply. It is down to less than 18 per cent today.

devoid of nature at all. This collected series of images presents an entirely man-made environment shaped exclusively by function and, as such, defining its own order, tonal palette, and graphic catalogue.

Collins is knowledgeable about his subject. He has a long-held interest in industrial structures and landscapes. A connection with the Financial Times opened the door to his first nuclear power station, Sellafield, and, after waiting nine months to achieve security clearance, his visit revealed to him both the archaeological nature of these sites and a technological palimpsest – stasis in tandem with layering that is uniquely industrial and is amplified in nuclear sites. The photographs that he took then attracted the attention of the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority which is charged with responsibility for dealing with the afterlife of the power stations after they cease operating. The NDA sees consultation with the public as an essential part of its activities, and it was this that motivated Collins’ commission to document the stations. Collins accepted the commission with the proviso that he would be free from direction from the NDA. It would be understood as a creative project, rather than commercial photography. His uncompromising stance was understood and accepted by the public body and access, whilst highly controlled in terms of safety, was effectively unlimited.

Not subject to the decarbonisation programme that drove the demolition of coal and oil-fired facilities, a generation of nuclear power stations has reached the end of its operational life. Unlike the carbon operations, the winding down of atomic sites is incremental. The half-life of spent nuclear fuel necessitates that change is at a glacial pace. From a heritage perspective, this gives time to consider the value of the old stations. It offers the opportunity to appreciate the preserved image of facilities that were founded on notions of stability and maintenance regimes that prioritised a status quo – change for change’s sake was not desirable.

The photographer Michael Collins is one of the few people who have been afforded access to all of Britain’s nuclear sites. His new book, The Nuclear Sublime, captures, in extraordinary detail, a moment and an aesthetic that is as intriguing as it is unsettling. Collins’ view though is not one of objects in a field, his is an interiorised perspective, a rare glimpse into contained space that is almost devoid of natural light, indeed

His work reflects Bernd and Hilla Becher’s powerful documentation of the typologies of industrial architecture, and he shares their fascination with various forms of record photography. When Collins met the German artist duo in Dusseldorf, they discussed the question of the influence of the Neue Sachlichkeit photographer Albert Renger-Patzsch on their work. Bernd Becher told Collins that the canon was not that useful to him and produced a gazette of local industry from the Siegen area where he grew up as an example of the type of image that inspired him.

Collins has explored many archival collections and champions their inherent cultural value. For him, the period in which municipal departments and large engineering contractors routinely employed professional photographers represented documentary photography in its purest form. It has left a largely unknown but very valuable legacy of images that are yet to be fully appreciated for the technological record they contain and the corresponding socio-cultural narratives that they support. He believes they deserve statutory protection in the same way that buildings are protected by listing for their architectural or historic significance.

071

(Above)

2

A

(Left)

Pile Cap detail Reactor

Dungeness

Pile Cap and Crane, Reactor 2 Dungeness A 2022

THE NUCLEAR SUBLIME

072

073

1A

NUCLEAR SUBLIME

(Below) (Left) (Below Left) Pile cap Crane Control No 1A Sizewell A 2022

Control Panel Crane Control No

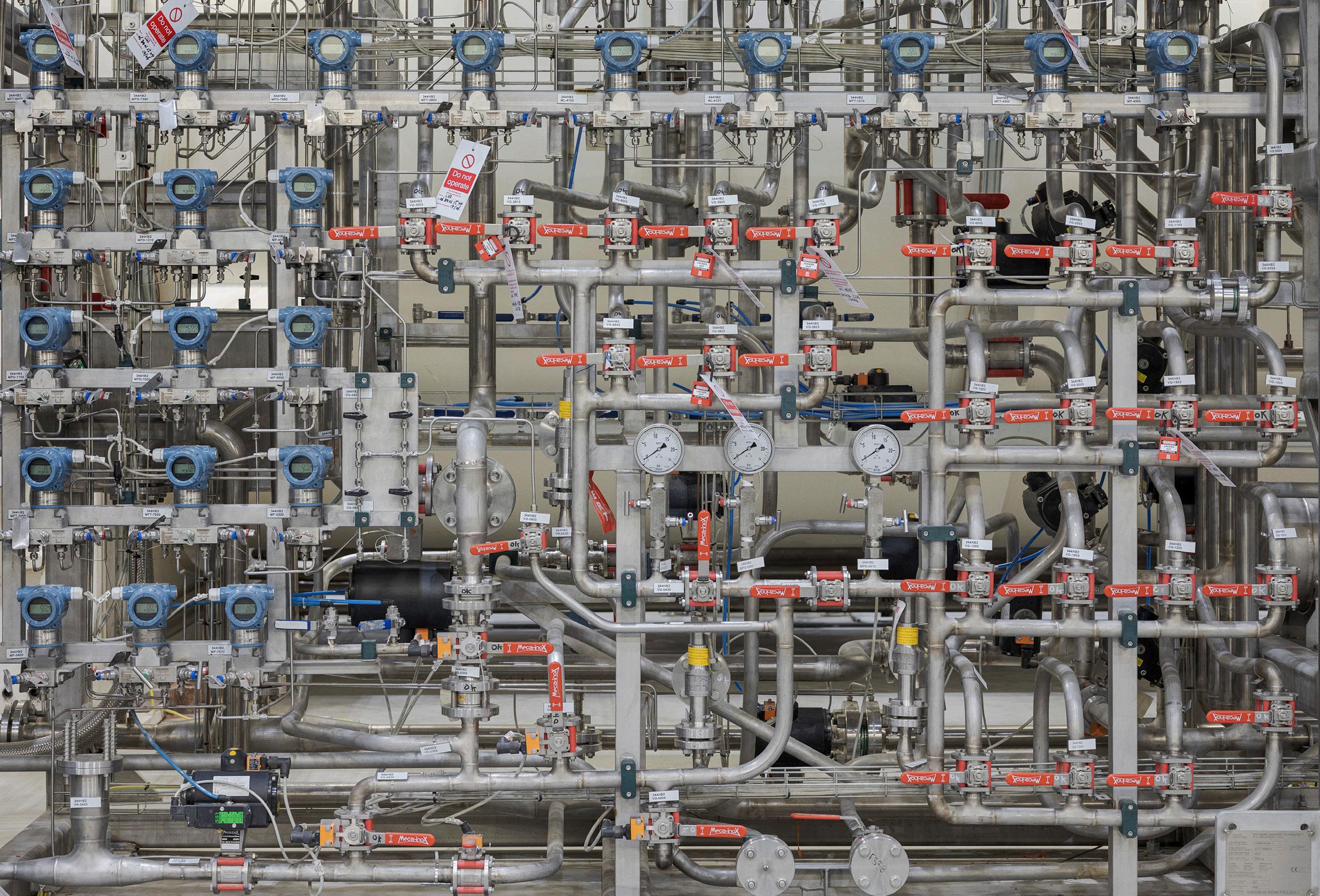

Manifolds and Valve Control System Cryoplant International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor 2022 THE

In Collins’ work this “most matter of fact” aesthetic is important. He seeks clarity, a depth of field, sharpness of focus and compositions that are revealing and not necessarily exhibiting mood or sensation. This careful and informed approach lends the photographs in this collection a neutral quality that commits the viewer to visual interrogation, every detail, mark, insignia, object, or colour has its own meaning that narrates a bigger story beyond the limits of each frame. Collins’ aim is not to document, despite employing a documentary style, and this is manifest in the images which ask more questions than they answer in their production.

Collins describes nuclear sites that have been decommissioned as “private museums”, and their interior details as free from the interpretation of curators. His gaze into these secure spaces, admittedly personally thrilling by virtue of their inaccessibility, allows the viewer to form their own interpretations. Collins’ text accompanying his images is as precise as the photography and describes the processes of production. In so doing, Collins contextualises the contents of each image within a bigger system at the same time as liberating the viewer, allowing their own interrogation and interpretation. Fittingly they have a sense of containment, that each photograph is only giving a glimpse of a fraction of the spaces and sequences that constitute these systems. Here, the sublime is expressed in the absence of a complete understanding of how a nuclear power station functions, and our inability to grasp the consequences of nuclear energy and nuclear waste. Even an apprehension of nuclear physics and fission only offers a partial grasp of the operations of such complex sites, and it is this incomplete operational perspective that is captured in the photographs and in their compilation. They are an archive record, they are traces and memories of people and processes, but they are also artefacts in their own right.

(Previous Page)

(Right)

Turbinehall Chapel Cross No 1 2022

Waste Skip (New) Chapel Cross

in this case, safety. It makes sense to demarcate functions in clearly contrasting colours. At Dungeness the pile caps – the thick concrete mats – are marked out in white on a blue floor so that a crane operator can be unequivocal in their motion. For decades designers have toyed with these aesthetics. Ben Kelly’s work for Factory Records and others is perhaps the most celebrated. The floors of the reactor halls also call to mind Sam Jacob Studio’s recent scheme for the Science Museum Group’s National Collections Centre. Both are codified spaces. However, the contrast in purpose is stark. An underlying sense of the seriousness of the codification of these operations is hard to shake and, as fascinating as their reading and interpretation is to the viewer, as beautiful as the aesthetic may seem, the images are inevitably ominous.

Beyond the content of each photograph, a nuclear aesthetic is made evident. Pragmatic industrial design creates its own visual image, a lexicon of function and,

The book includes photographs from British nuclear power stations at Chapelcross, Dounreay, Dungeness, Sizewell, Torness, Trawsfynydd and Wylfa. However, this is more than a work to record and recall: Collins’ conception of The Nuclear Sublime extends to those facilities that are developing a new generation of power production to address the transition from carbon. The closing images are from sites researching nuclear fusion reactors in the UK and France. These new objects are not the worn, patinated, entropic surfaces of power stations past, they are crisp, cast and overwhelmingly polished stainless steel and aluminium edifices, some with their cellophane wrappers yet to be removed. More than those that preceded them, their image is “bewilderingly technological”, “challenging the limits of our comprehension”. By their inclusion Collins reminds us that the ghosts of nuclear past are not monuments to histories – in the absence of any viable alternative, they are but a staging post to a seemingly inexorable future.

The Nuclear Sublime is published by RRB Photobooks £50. A special edition including a print is available for £200.

Photographs copyright Michael Collins.

076

(Above)

Pile Cap Reactor 2 Trawsfynydd 2023

(Right) Turbine Hall Gauge Board Sizewell A No 1 2022

(Right) Turbine Hall Gauge Board Sizewell A No 1 2022

079

079

THE NUCLEAR SUBLIME

(Left) Control Room Reactor 2 Dungeness A 2022

080

Window No 10 Irradiated Fuel Cave Dounreay Prototype Fast Reactor 2023

Right) Dounreay Prototype Fast Reactor Mortuary Control Panel 2023

Refuelling Cavity Reactor Sizewell B No 2 2023

(Below) (Right) (Below

(Below) (Right) (Below

081

WORDS Deyan Sudjic PHOTOGRAPHY

Where design meets art

Clémence and Didier Krzentowski set up Galerie kreo in Paris as the outcome of their personal collection. It provides a distinctive view of contemporary design

082

Emma Le Doyen

(Right) Commissioned and displayed by their gallery, Marc Newson's Quobus storage system has a practical purpose. Photography Emma Le Doyen

(Left) The Krzentowski apartment overlooks the Seine, and is filled with their collections. Photography Emma Le Doyen

Clémence and Didier Krzentowski established Galerie kreo in 1999 in the rue Louise Weiss, an unprepossessing area of eastern Paris. They joined a group of galleries focused on French contemporary art that left the high rents of the Marais in the city centre behind and moved into a building leased cheaply to them by the government. At a time when the Parisian art scene had become something of a backwater eclipsed by London, Berlin and New York, rue Louise Weiss turned into a thriving platform for new work. “I won’t go so far as to say that it stopped us being ashamed of being French when it came to contemporary art, but it certainly gave us a reason to hope,” one gallery owner described the project later when the artists’ attention had moved to other areas of Paris.

Galerie kreo brought something new to the mix of contemporary culture: design. Its opening exhibition was titled Furniture and Objects 1960-2000 and mixed vintage pieces followed by new work from such designers as Marc Newson and Ron Arad. The gallery developed a distinctive personality, offering design from the recent past, particularly lighting from France and Italy, dating between 1945 and 1985 but also by working with contemporary designers to produce limited editions. Galerie kreo stands out from other galleries that offer what was sometimes called design art, a blurry category that sometimes fails to be either. The designers it works with belong almost exclusively to the mainstream of industrial design. Jasper Morrison, for example, who had his first solo exhibition with kreo in 2006, has produced flat screen televisions for

084

(Above) Grcic used square section aluminum, a ready-made material from the car industry, for precision engineering as the basis for a group of seven lights. Displayed is a group of glass tables and a chair. Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

Sony, cameras for Canon and furniture for Muji. Like Morrison, Konstantin Grcic, who was Morrison’s first assistant, has also been involved with mass production. This experience gives both designers an insight into the potential of industrial materials and technology. Morrison designed the Air Chair for Magis, which has been made in the hundreds of thousands. It depends on industrial gas-blown plastic moulding techniques, developed to make cheap components for car interiors, that require no finishing or manual work, which allows them to sell for £118 each. Morrison’s Carrara table collection for kreo is put together by hand and made from aluminium honeycomb and marble in an edition of just 12, along with what is known as a prototype, or artist's proof, and is available for up to £43,000.

The concept of the limited edition comes from the early days of printing and moulding techniques, when each impression caused a slight drop off in quality as the copper plate was brought into contact with the paper, or each time a mould was used to make a cast. Translating the concept of the edition to contemporary design is not an exact match. It is not about avoiding a deterioration in the sharpness of an impression. Limited editions reflect the experimental nature of the pieces which cannot be mass-produced at reasonable prices. An edition allows for designers to experiment with what is possible without the constraints of mass production.

085

(Above) Konstantin Grcic named his show Transformers, but confessed that his lamps were neither tranformable, nor robots. He used aluminium and glass for furniture that he suggests should not be seen as furniture

(Right) For a group show each designer taking part produced their own version of a ladder. Virgil Abloh contributed the Leaders ladder, inscribed with the names of people he found inspirational.

Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

(Above) Konstantin Grcic named his show Transformers, but confessed that his lamps were neither tranformable, nor robots. He used aluminium and glass for furniture that he suggests should not be seen as furniture

(Right) For a group show each designer taking part produced their own version of a ladder. Virgil Abloh contributed the Leaders ladder, inscribed with the names of people he found inspirational.

Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

(Image) Galerie kreo paid tribute to Virgil Abloh with Echosystems, an exhibition that placed work that inspired or attracted him, including Jerszy Seymour's ladder, set against the mural by Pablo Tomek. Photography Alexandra de Cossette, Courtesy Galerie kreo

(Image) Galerie kreo paid tribute to Virgil Abloh with Echosystems, an exhibition that placed work that inspired or attracted him, including Jerszy Seymour's ladder, set against the mural by Pablo Tomek. Photography Alexandra de Cossette, Courtesy Galerie kreo

You can use a Carrara table as a stand for a stereo system, to hold a vase or a framed photograph, but if you could afford to buy one, its role in a domestic interior would go beyond its practical purpose. Even as a child, Jasper Morrison understood that some objects and certain pieces of furniture could create what he calls “an atmosphere” that put him in a good frame of mind. He remembers a room in his grandfather’s house as the first modern space that he ever encountered. He noticed that it had bare floorboards, a shag pile rug and a Dieter Rams designed Braun radiogram, a line-up that he later realised was the result of his grandfather’s prolonged exposure to Denmark. “It was an early revelation that a space like that could make you feel better. Subliminally I knew I felt good or bad in a place instantly. Discovering that design can cause a change in the atmosphere of a place was vital. Function can be handled, but the atmosphere of an object is its most important quality.”

For Morrison, and other designers from his generation such as Tom Dixon and Ron Arad who began their careers in the London of the 1980s, making furniture themselves in very small numbers was a necessity. There were no manufacturers interested in working with them. So, Ron Arad started by salvaging seats from Rover cars, Tom Dixon taught himself to weld, and Morrison made 20 examples of a side table using two sets of bicycle handlebars at each end of a plank. One set to stand on, the other to hold up the glass tabletop. It was a witty reminder of Marcel Breuer’s first cantilevered steel chair that had been inspired by the Adler bicycle that he rode around Dessau while teaching at the Bauhaus. And it paid Morrison’s rent for a while.

Grcic, who designs mass-produced furniture for Vitra and lighting for Flos, but like Morrison also has a sensibility that brings him close to the art world, used to compare the design of editioned pieces to the relationship between working on a Formula 1 car, made each year in low single figures and producing a high-volume production car. There are technologies to be transferred and concepts to be shared.

But Clémence Krzentowski has another explanation for the appeal that producing a collection with kreo has for the designers that they work with regularly. Against a background in which many product categories, from cameras to music systems and TV sets, have dissolved into the digital cloud, working with physical objects with people who care about the way in which they are made remains important for designers. And even in the furniture world, many companies no longer maintain the same direct relationships with designers that they once had.

088

(Left) Pen and ink drawing by Ronan Bouroullec

Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

(Right) AR Penck's bold painting formed part of the Echosystems exhibition.

Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

(Above) Tajimi 08 one of a series of ceramic pieces by Ronan Bouroullec.

Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

Galerie kreo has been shaped by Didier Krzentowski’s lifelong passion for collecting. He started by assembling a collection of key rings and then of watches as a child. Early on he bought a complete series of Nan Goldin photographs from her first show in Paris and has been accumulating art ever since. At various times he has collected flint tools, lesser-known Hermès bags from 1950 to 1980, and the furniture of Pierre Paulin. He told Alice Rawsthorn from the New York Times that he had originally planned to build a modern chair collection but discovered it was too late –Rolf Fehlbaum, founder of the Vitra Design Museum had beaten him to it. After he acquired a Verner Panton Wire lamp, better described as secondhand rather than vintage given that it was made as recently as 1972, Krzentowski realised that 20th-century lighting was still unclaimed territory. Since then, he has built up more than 800 examples of lights of all kinds going back to the 1950s. A Swiss publisher has produced two books documenting it.

Clémence Krzentowski was working for the Winter Olympics in France in 1992 when she had the idea of commissioning Philippe Starck to design the torch. After the games, Didier and Clémence set up a consultancy together that choreographed commercial partnerships for designers, such as the Ricard branded carafe and pitcher, respectively by Garouste & Bonetti and Marc Newson, produced for the pastis maker.

090

(Below) Edward Barber and Jay Osgerby's lighting pieces, titled Signal, were shown both in Paris and in London. Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

But Didier spent more and more time haunting showrooms and flea markets to pursue his collecting obsession, and Galerie kreo became all consuming. It was successful enough to move from its original home to a much larger space on the rue Dauphine in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, close to the Seine, in 2008. They took over what had been Ruby's, a nightclub on the ground floor of the Hôtel de Mouy, a grand late 17th-century townhouse.

The gallery’s philosophy has been to produce new collections of work with individual designers, and to intersperse them with group shows that mix the well established with newcomers. It is a chance to find new talent, without imposing the pressure of a solo show on less experienced designers.

Along with Marc Newson, Jasper Morrison and Konstantin Grcic, kreo has built up long-term relationships with both Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec, Hella Jongerius and Ed Barber and Jay Osgerby, among others. And in 2020 they staged Efflorescence, a solo show with Virgil Abloh, at the time working for Louis Vuitton’s menswear collections.

The Krzentowskis were close to Azzedine Alaïa and his approach to fashion, but had been careful to avoid their collections being co-opted by a prominent fashion label. With Abloh, who had trained as an architect and was himself a serious collector of contemporary design, it was clear that was not the intention. Design fascinated him, and Abloh brought his own distinctive sensibility to the project.

After Abloh’s sadly early death in 2021, kreo brought together Echosystems, a remarkable celebration of his life and influences from skateboard to graffiti, art from Gordon Matta-Clark and JeanMichel Basquiat as well as design by Tom Dixon, Jerszy Seymour and the Bouroullecs. In a sense it was also a summation of Abloh, and of the unique achievement of Galerie kreo.

091

(Left) Guillaume Bardet's 2019 exhibition. Photography Fabrice Gousset, courtesy Galerie kreo

WHERE DESIGN MEETS ART

(Above) A piece made by Virgil Abloh for his first collaboration with Galerie kreo, the Effloresence exhibition, returned for Echosystems. Photography Deniz Guzel, courtesy Galerie kreo

092 (Right) Doshi Levien's Kinari bedside table. Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

(Left and above) A vase and a flask made by Hella Jongerius during her exploration of the interaction between colour and form, part of a long relationship with the gallery. Plate with bird is another of her pieces. Photography Sylvie Chan-Liat, courtesy Galerie kreo

092 (Right) Doshi Levien's Kinari bedside table. Photography Alexandra de Cossette, courtesy Galerie kreo

(Left and above) A vase and a flask made by Hella Jongerius during her exploration of the interaction between colour and form, part of a long relationship with the gallery. Plate with bird is another of her pieces. Photography Sylvie Chan-Liat, courtesy Galerie kreo

095

(Above) Not all of Didier Krzentowski's collections are contemporary. He has a number of flint tools that were made before the age of mass production and machines.

WHERE DESIGN MEETS ART

Photography Emma Le Doyen

096

(Below) Didier Krzentowski has an extensive collection of lights, with a focus on Italian and French designers from 1950 to 1980. The Gino Sarfatti wall lamp was particularly rare. He saw it on the cover of an ancient copy of Domus and was determined to track it down. Photography Emma Le Doyen

099

WHERE DESIGN MEETS ART

(Above) Clémence and Didier Krzentowski in their apartment.

Lab and processing by S.C.A.N. Services

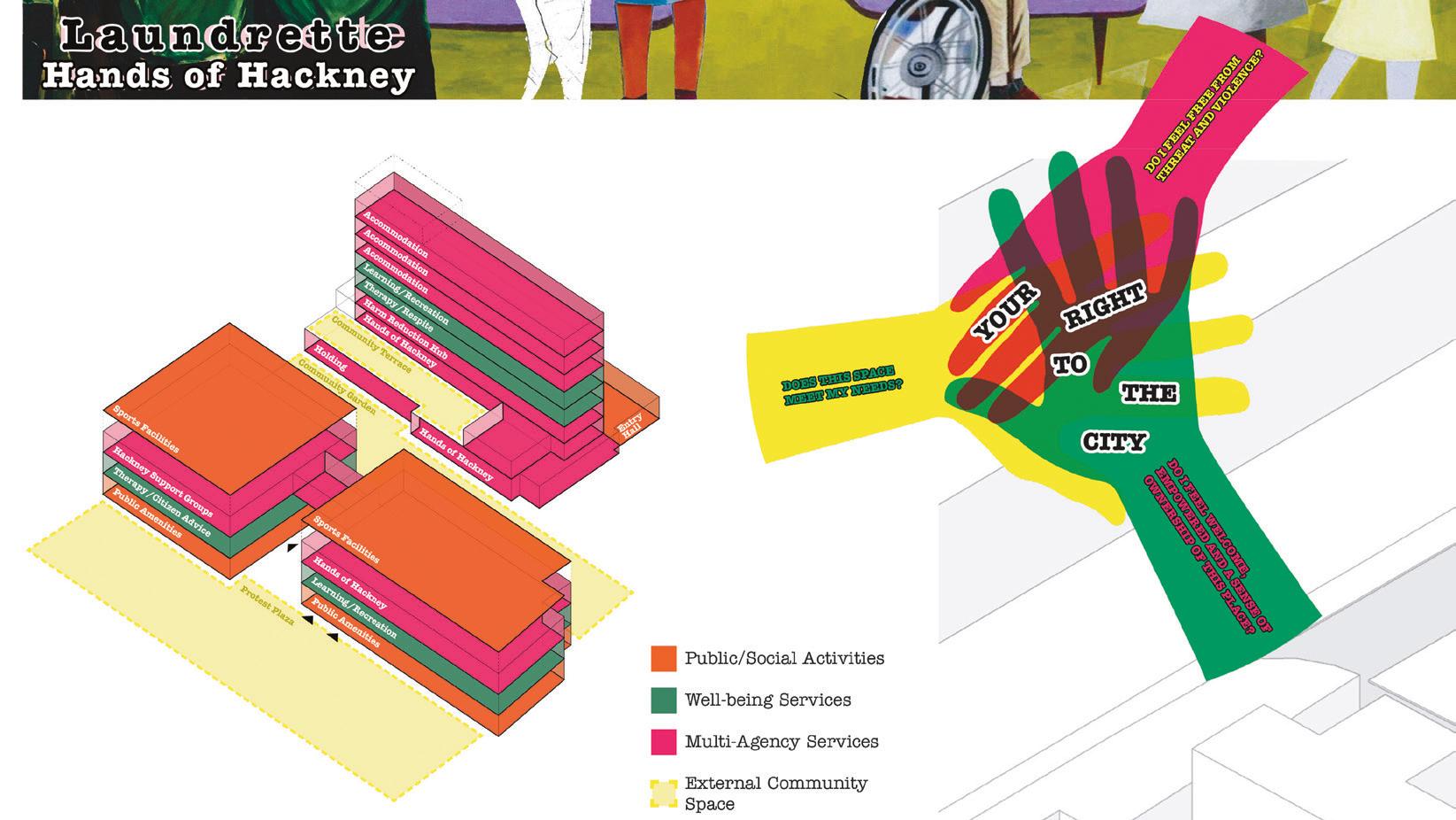

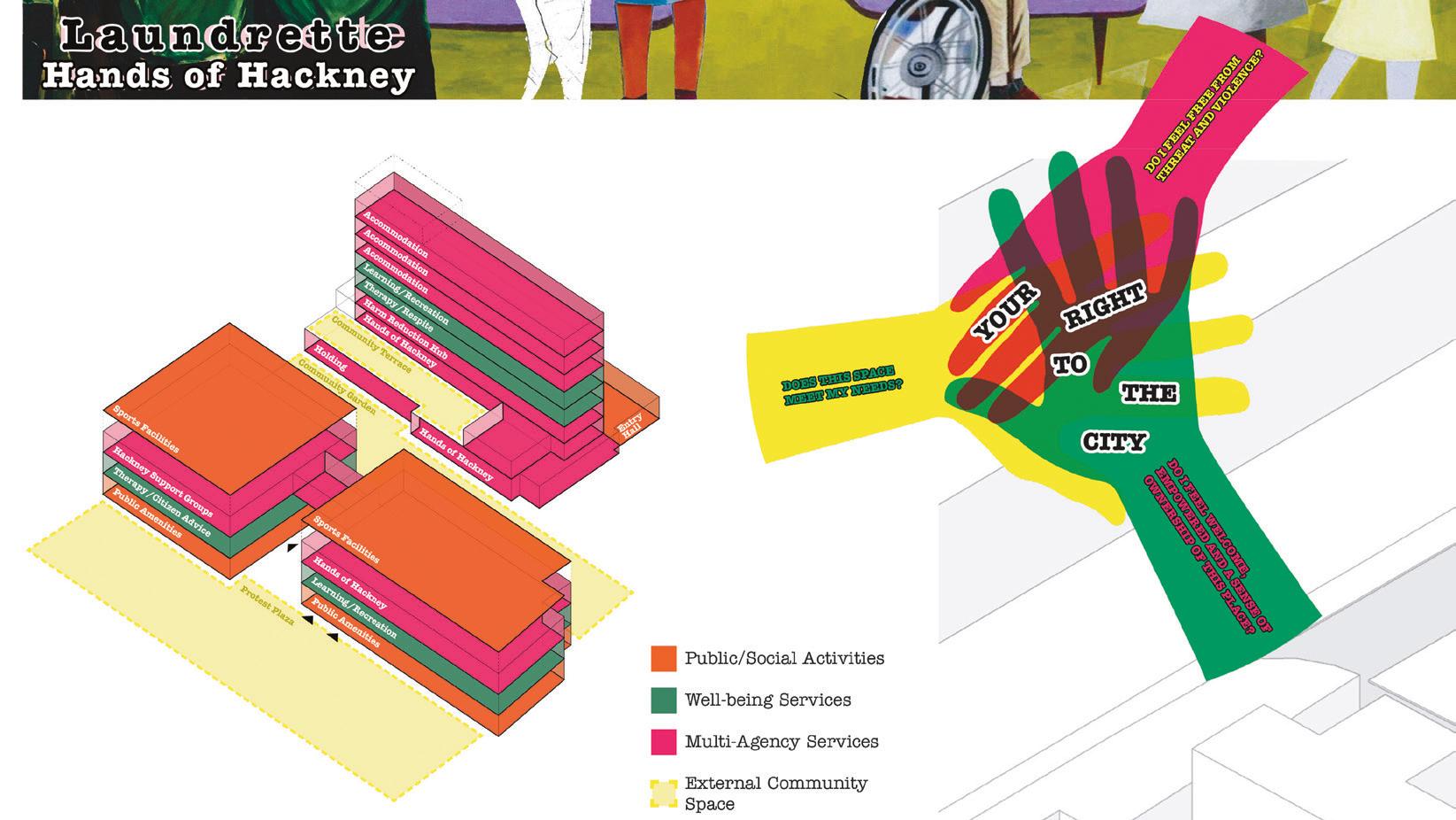

What does it take to design a habitable civilisation on the moon? Hassell reveals the Lunar Habitat Masterplan, offering a glimpse into humanity’s next frontier

Living on the Moon

0100 o

(Right) Frontal view of Hassell's Lunar Habitat Masterplan, copyright ©imigo

WORDS Ayla Angelos

Despite the robot moon lander Odysseus breaking one of its legs on touch- down in February, America’s plans to establish a long-term lunar human settlement are moving ahead. More than 50 years since the last time humans walked on the moon and the Apollo 17 mission returned to earth, NASA’s Artemis programme is taking shape. It involves funding private companies such as Elon Musk’s Space X and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin to build the rockets, and Intuitive Machines to design and make the landers that, between them, would make a return possible. Despite pushing back the tentative date for the first human to return to the moon to 2026, NASA is still planning to build a lunar base within a decade.

“It’s a bit like having a masterplan for a city; you don’t always know how it will be filled in”

is changing; the astral community is becoming much more inclusive. Tourism will be a thing,” says De Kestelier. “In our masterplan, we’ve set it up so that it can be developed in different ways, whether that’s tourism, science, research, exploration or manufacturing. It’s a bit like having a masterplan for a city; you don’t always know how it will be filled in.”

0102

America is not the only country planning for the trip. There have been recent Japanese, Indian, Chinese and Russian un-manned missions. The European Space Agency (ESA) has its own programme, which involves collaborating with NASA.

The idea of lunar settlements has preoccupied filmmakers and science fiction writers with increasing levels of technical plausibility ever since Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey correctly predicted the idea of a space station in earth orbit acting as a gateway to a lunar base. Since then, films such as Moon, Gravity and The Martian have depicted sterile, utilitarian base camps and remote research stations in which isolated individuals are trapped in the most unforgiving conditions.

Xavier De Kestelier, an architect based at the international practice Hassell, began thinking about space flight as a child, and has worked on concepts for lunar, Martian and low-earth orbit living in his professional life. Having lead Norman Foster’s submission for NASA’s 3D Printed Habitat Challenge in 2019, he acknowledges that the modular bubble-shaped structures shown in Ridley Scott’s film The Martian, in which Matt Damon’s character struggles to survive after being marooned on the Red Planet, are likely to resemble what might actually be built with a fair degree of accuracy. Most recently, he led the design of the Lunar Habitat Masterplan, conceived in collaboration with ESA and Cranfield University.

The ambition of the project represents a significant step forward compared to previous plans for settlements in space, which have been designed to accommodate a maximum of 12 astronauts – the capacity of the International Space Station (ISS). De Kestelier envisages a community that could grow in self-contained stages to reach a maximum capacity of 144 people. This reflects the evolving nature of the idea of space travel and its fundamental purpose. SpaceX has launched some extremely wealthy tourists into space, and flights have gone up to the ISS, meaning that space tourism is well and truly underway. The Lunar Habitat Masterplan has been designed to cater for a wider range of people hoping to travel to the moon. “The type of astronaut

It’s no secret that the moon is a vastly inhospitable place. It has no atmosphere, and while scientists have identified limited concentrations of water molecules at the moon’s poles, the Artemis mission will have to find usable amounts of water to make permanent settlement possible. Bringing it from earth in sufficient quantities would make no economic sense in the medium and long term, it would demand too many rockets to be feasible. Another equally difficult problem to overcome is the absence of a magnetosphere to protect the moon from solar wind and radiation. “The big difference between the moon and the earth is that our planet is electromagnetically charged. We have an invisible shield protecting us from radiation from the sun and the cosmos,” De Kestelier explains.

Living in a rock cave with walls thick enough to screen out harmful radiation would be the idea solution, but since none have yet been identified, the ESA plan envisages that the astronauts would need to build their own protection. Cargo rockets would bring teams of lightweight solar-powered robotic printers, capable of operating in swarms to scoop up lunar dust and form it into thousands of solid hexapod forms, something like the concrete barriers used to guard against coastal erosion on earth. Also in the cargo bay would be a large lightweight plastic balloon packed flat, that once inflated would provide the form on which the robots would build the protective shell and ensure that it took the planned shape. A subsequent rocket would bring the living quarters themselves, also inflatable, that would be inserted under the shell in groups of three or four, each one equipped with a prefabricated airlock.

ESA’s masterplan suggests a basic inflatable unit that could house four astronauts, with its own solar power supply, and with enough space for them to live, work and socialise. The settlement would grow by adding more and more of these units, connected by airlocks, and inflatable external corridors to allow for communication and privacy.

The units would be pressurised and allow for an assortment of uses and layouts, such as kitchens, living rooms, labs, greenhouses and gyms. Each basic unit is 10m by 23m and is structured on three levels. Astronauts would sleep and move between one unit and another at the lowest. Above that is an elevated walkway, an inflated tube which De Kestelier calls a “lunar street”. There is an external route for astronauts to enter the lunar environment through an airlock or connect to rovers, vehicles that

can operate in low gravity which were called dune buggies in the Apollo era, three of which were left behind in the 1970s.

Life on the moon is not all about having a place to rest your head during the extended night (which lasts 14 earth days), or a porch to put your moon boots on. It’s also about making the planet as welcoming a place as possible to live for the long-term. “We need to start planning for how larger communities can not only just survive, but also thrive and live on the moon,” says De Kestelier. If you look at the ISS (and most of the film depictions), you’re met with a cliché assortment of cold, sterile materials and tiny spaces for the astronauts to manoeuvre in –there’s enough room to house a city of mechanical equipment, but nowhere to relax and unwind. The ISS doesn’t even have a living space – it was apparently cost-engineered out of the design. The Lunar Habitat Masterplan has designed a more comfortable settlement with both recreational spaces and bedrooms, cushioned by the aesthetics of a “nice little boutique hotel”, says De Kestelier. In the bedroom renders, for example, the floor has carpets and bamboo finishes. “We imagine growing bamboo on the moon,” he adds. “It grows quickly in greenhouses and can be used to create more tactile environments.”

The location of the habitat also plays a vital role in the survival of its residents. If you’re on the moon’s equator, you’d have 14 days of day and 14 days of night. A case of SAD would kick in every two weeks, the temperature would drop and you’d be unable to harbour enough solar energy. “Which is terrible and bad for your mental health,” says De Kestelier. The Lunar South Pole, where he has sited the settlement, is on a slightly higher level and the sun will turn 360-degrees around it over 28 days, providing a constant source of energy. “The sun is always there,” De Kestelier adds. It’s also near the Shackleton Crater, close to India’s Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft landing base from last year, where ice can likely provide sufficient drinking water and suitable options for mining.

Having worked with anthropologists, psychologists, roboticists and astronauts, the Lunar Habitat Masterplan shows that space settlements don’t have to be as sterile as those that came before. The concept is yet to physically land on the moon, but when astronauts return to space via the Artemis programme, and people start staying more permanently in the 2030s, these designs will be put through their paces. After thorough research and testing based on existing science, Xavier and the team are certain of their concept. “The way we approach design is, for us, never sci-fi. It’s always sci-fact.”

0103

(Below) Copyright ©imigo

LIVING ON THE MOON

(Above) Photograph of the Lunar Habitat Masterplan, courtesy Hassell

(Image) Concept bar for the Lunar Habitat Masterplan, copyright ©imigo

(Image) Concept bar for the Lunar Habitat Masterplan, copyright ©imigo

Sara Doherty (Right)

Sara Doherty (Right)

New Ways of Teaching Architecture

The London School of Architecture is Britain’s first independent school for architects since 1849. It’s small, but making a big difference

106

PHOTOGRAPHY Henry Gorse

108

Oliver Hartley

Jahba Anan

Olivia Bailward

Rose Hussey LSA communications manager

(Above)

(Above)

(Above)

(Above)

109 LONDON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

LSA 1st year students (Above)

Photography Henry Gorse

(Left and Above)

Thomas Harris

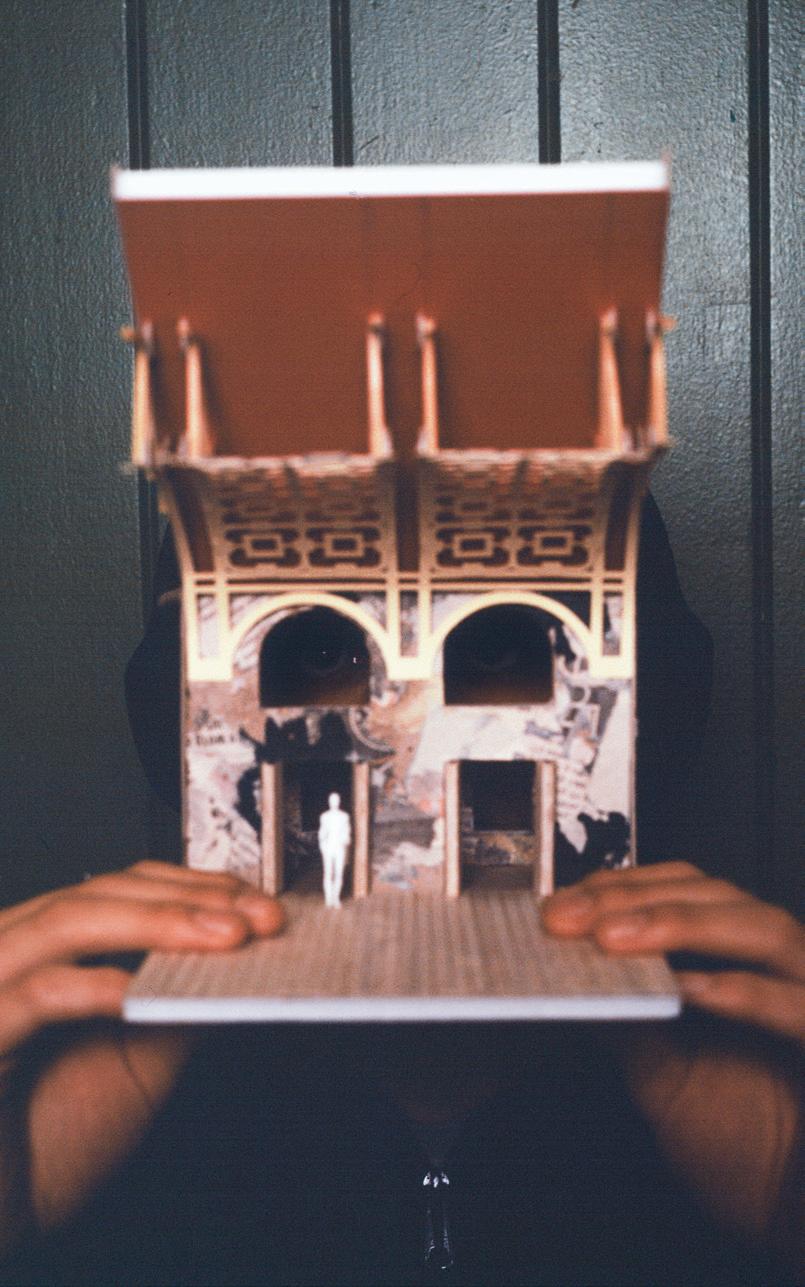

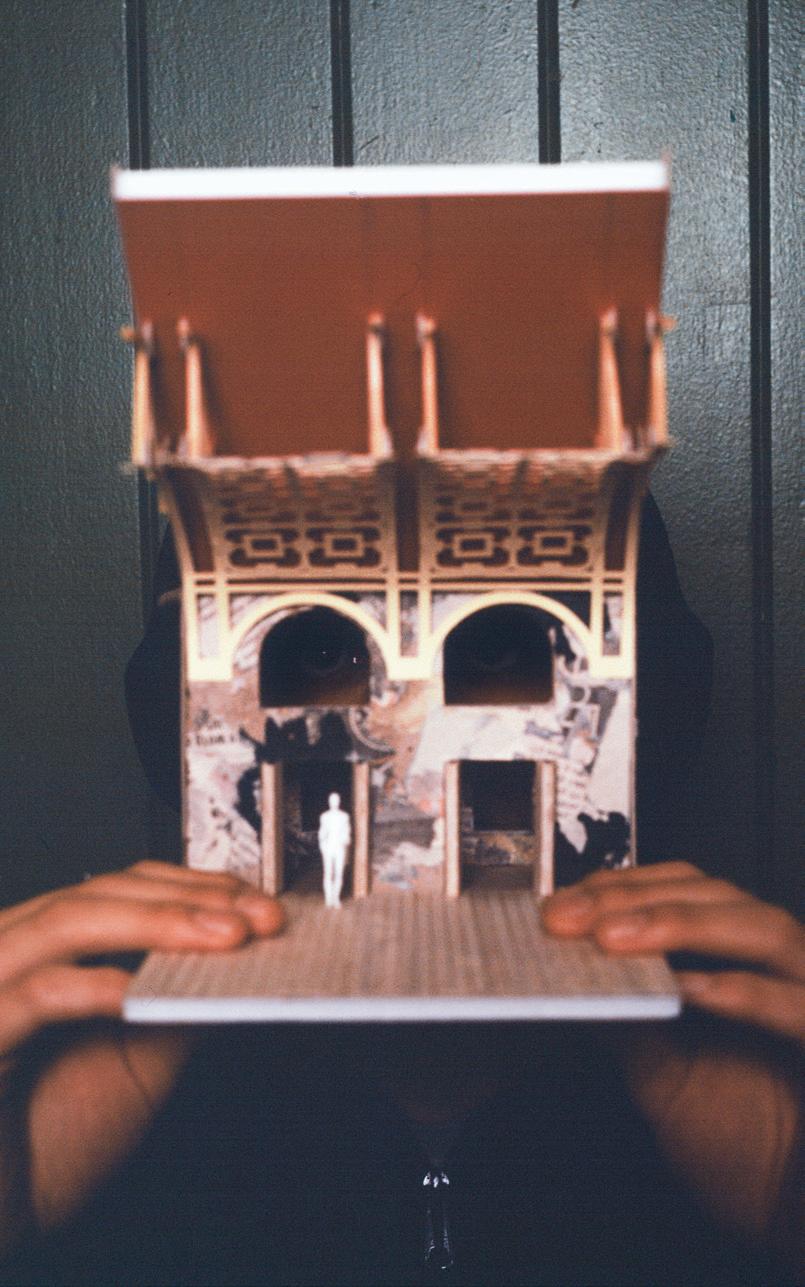

Completed his undergraduate architecture degree at the University of Plymouth, followed by an urban design course in Vancouver. He has a placement with Mulroy Architects. Pictured with his model of a staircase at Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre.

110

Photography Henry Gorse (Above)

Louis Duvoisin

He studied for his first degree in architecture at Newcastle University. While working for his MA Arch at the LSA he has worked for Grimshaw Architects. His major project is for the Battersea Arts Centre.

0111

LONDON SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE

Photography Henry Gorse (Below)

Connie Pidsley