KE HUY QUAN: WOW, WINNING AN OSCAR IS A BIG DEAL. BECAUSE PEOPLE THEN START CALLING.

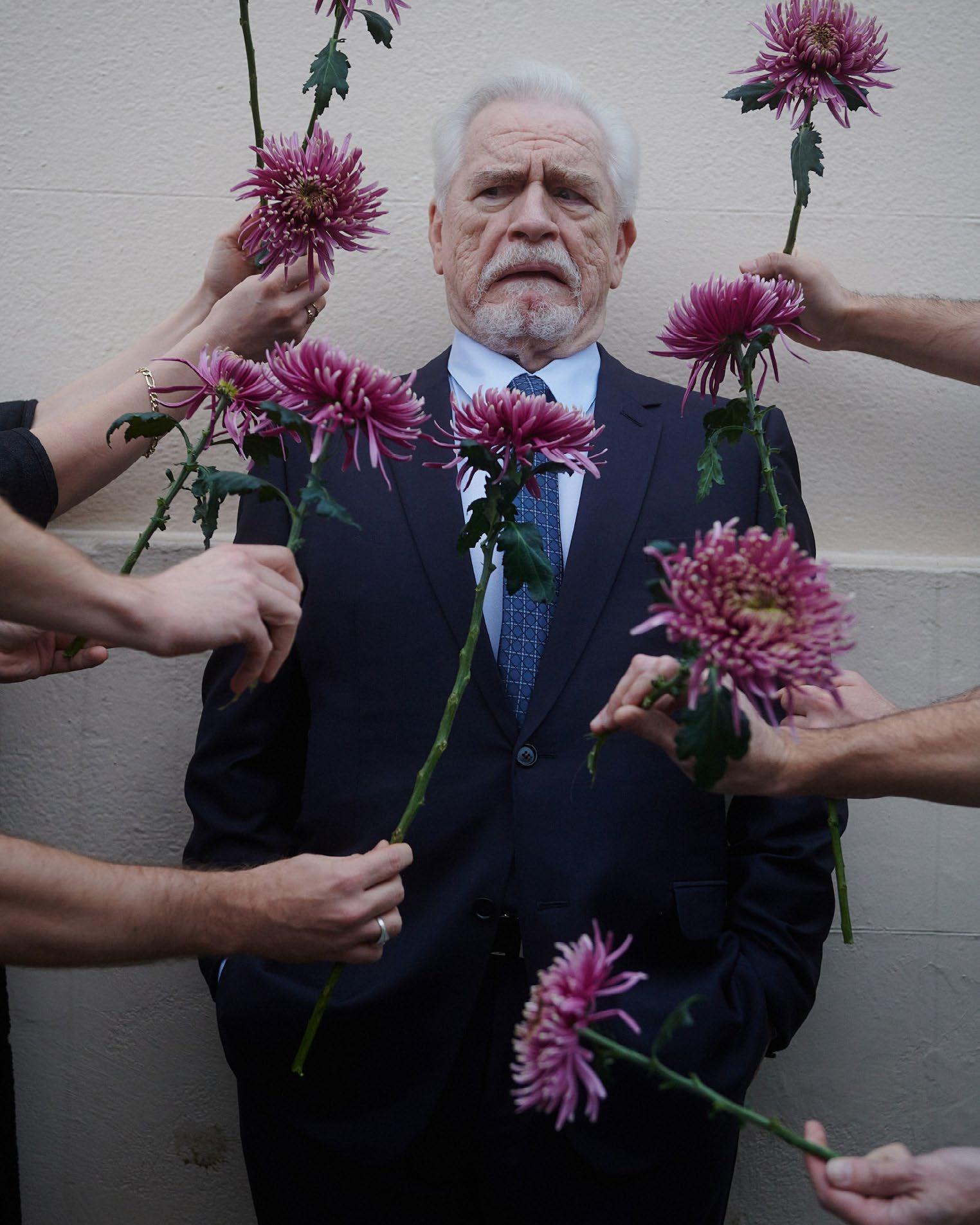

WHISHAW HARI NEF BRIAN COX PORT 34

BEN

9 772046 052060 34 £12

1

3

dior.com –020 7172 0172

5

dior.com –020 7172 0172

7

17

21

TWIGGY SEATING SYSTEM | RODOLFO DORDONI DESIGN DISCOVER MORE AT MINOTTI.COM/TWIGGY

SENIOR EDITOR

Kerry Crowe

MANAGING EDITOR

Samir Chadha

SPECIAL PROJECTS MANAGER

Ethan Butler

HOROLOGY EDITOR

Alex Doak

SUB-EDITORS

Sarah Kathryn Cleaver

Gus Wray

EU CORRESPONDENT

Donald Morrison

US CORRESPONDENT

Alex Vadukul

SENIOR EDITORS

Katrina Pavlos, Film

Hans Ulrich Obrist, Art Rick Moody, Literature

John-Paul Pryor, Music

Brett Steele, Architecture

Deyan Sudjic, Design

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Kabir Chibber

Robert Macfarlane

Albert Scardino

SPECIAL THANKS

Bella Weston

Jeremy Lee

FASHION EDITOR

Georgia Thompson

COVER CREDITS

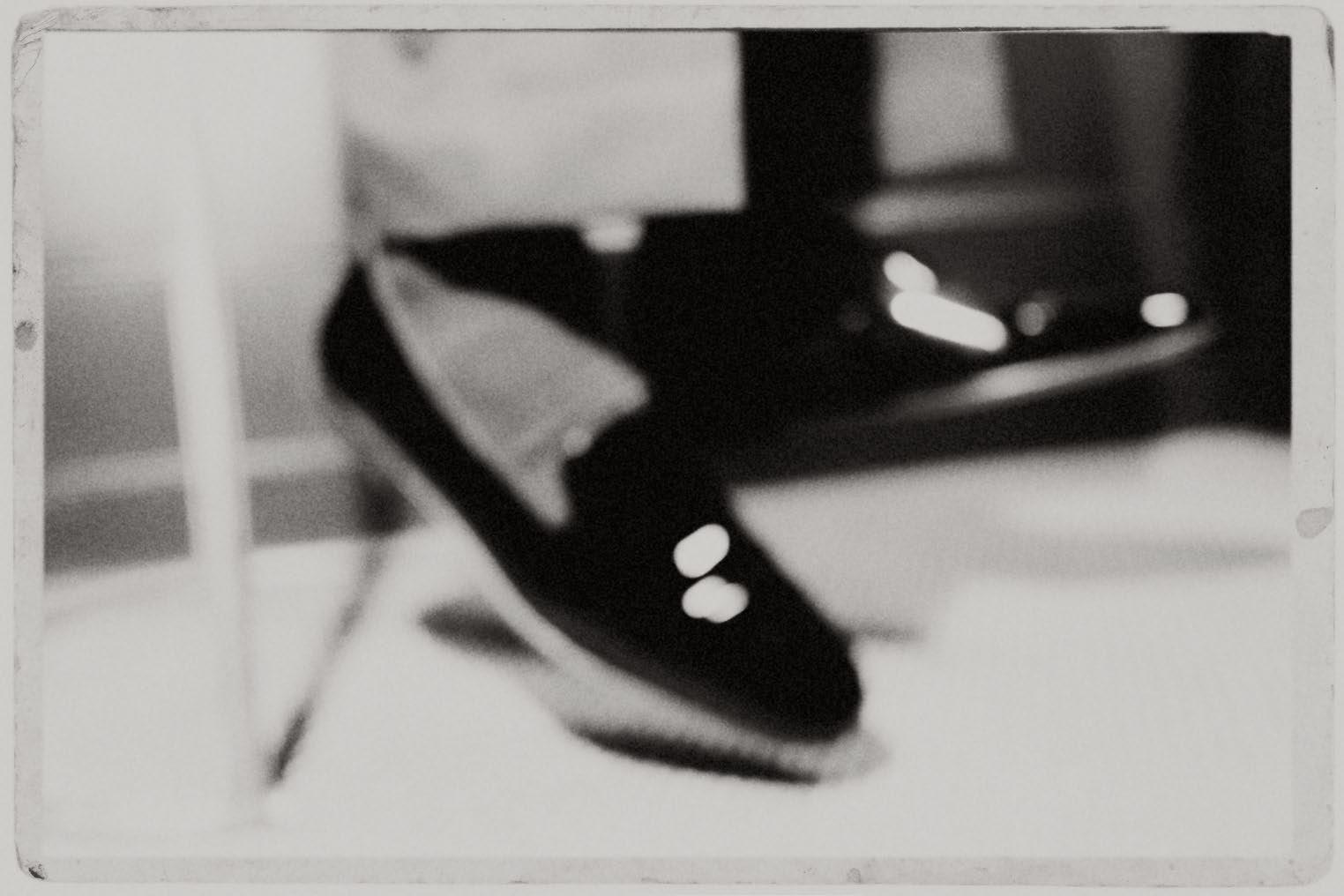

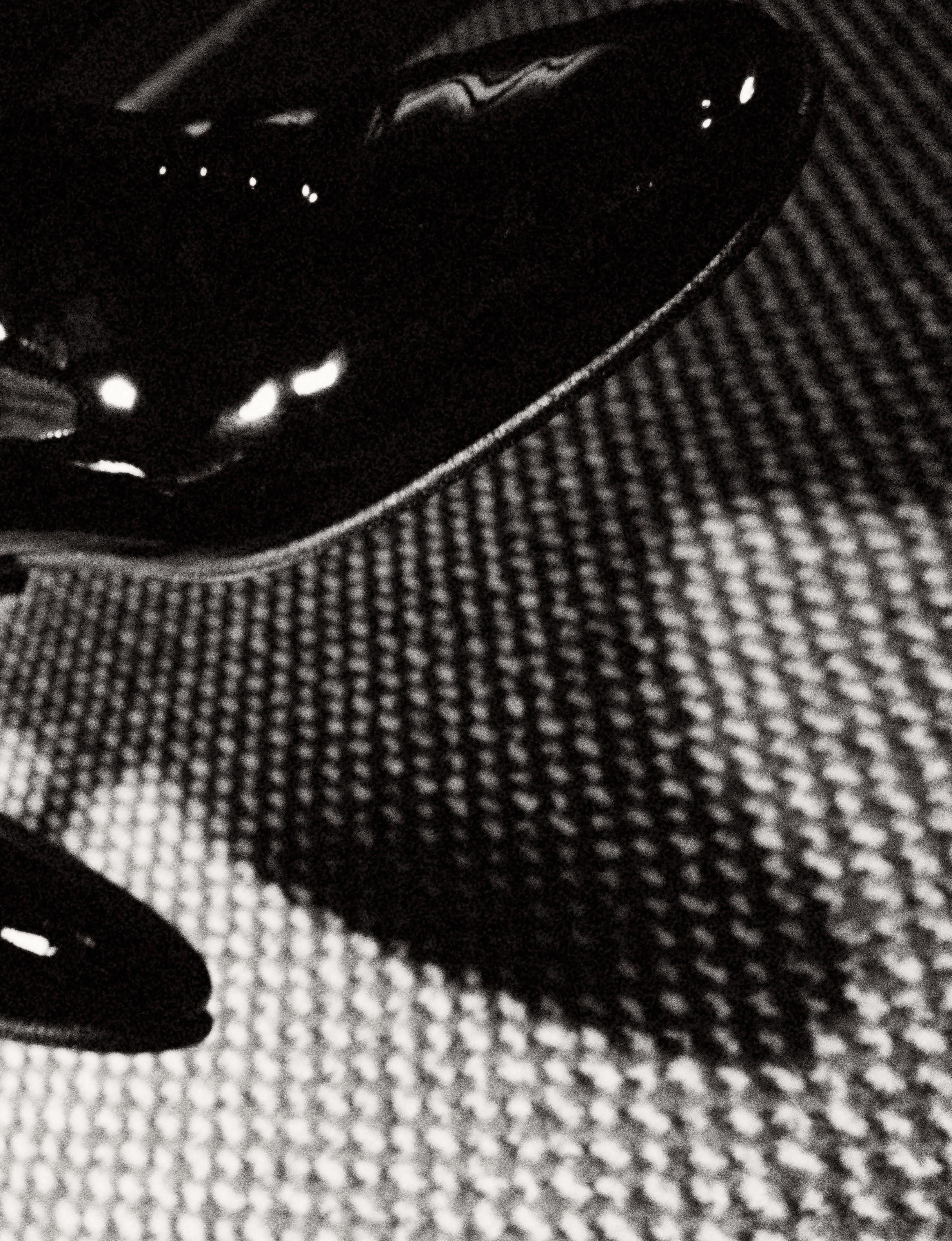

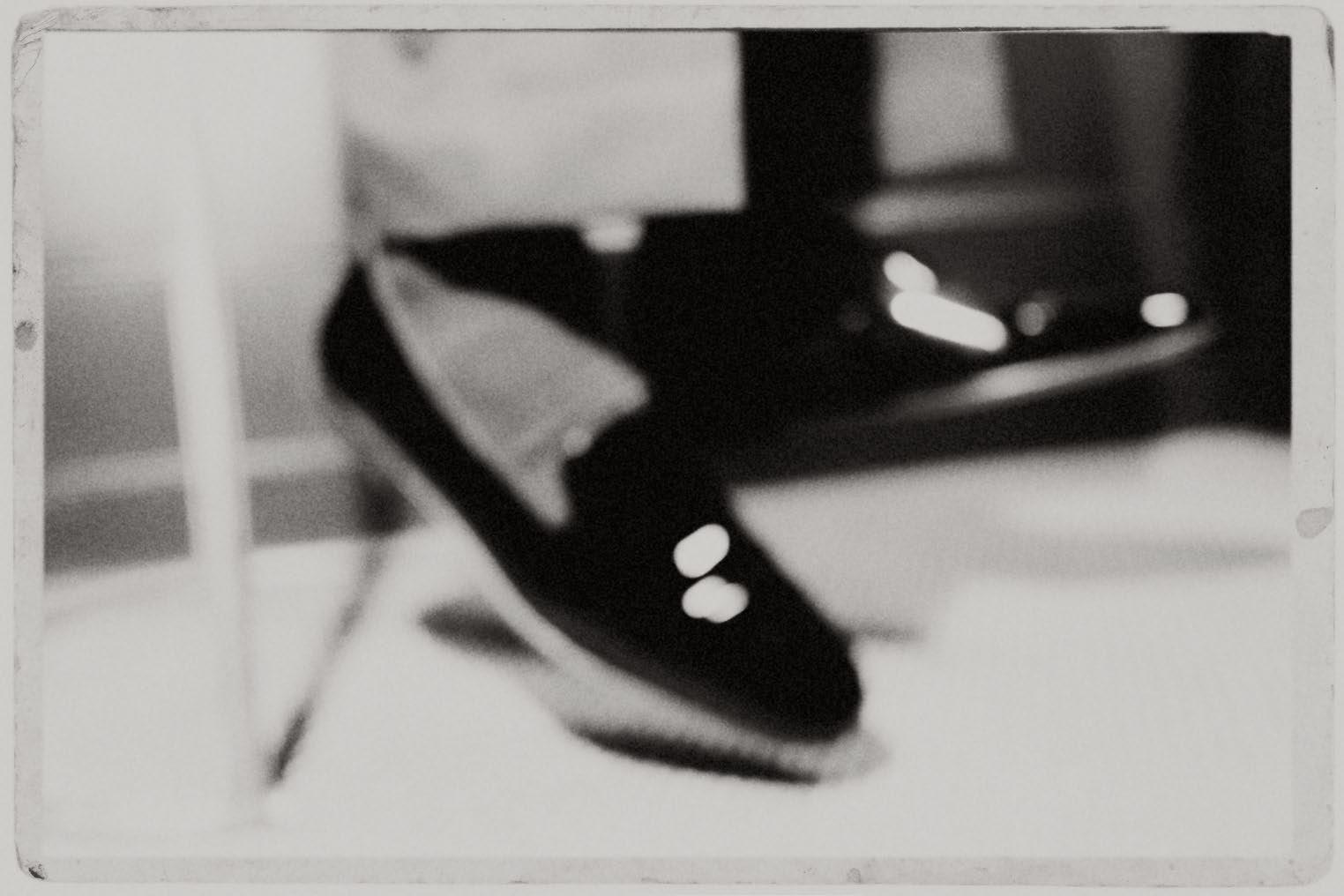

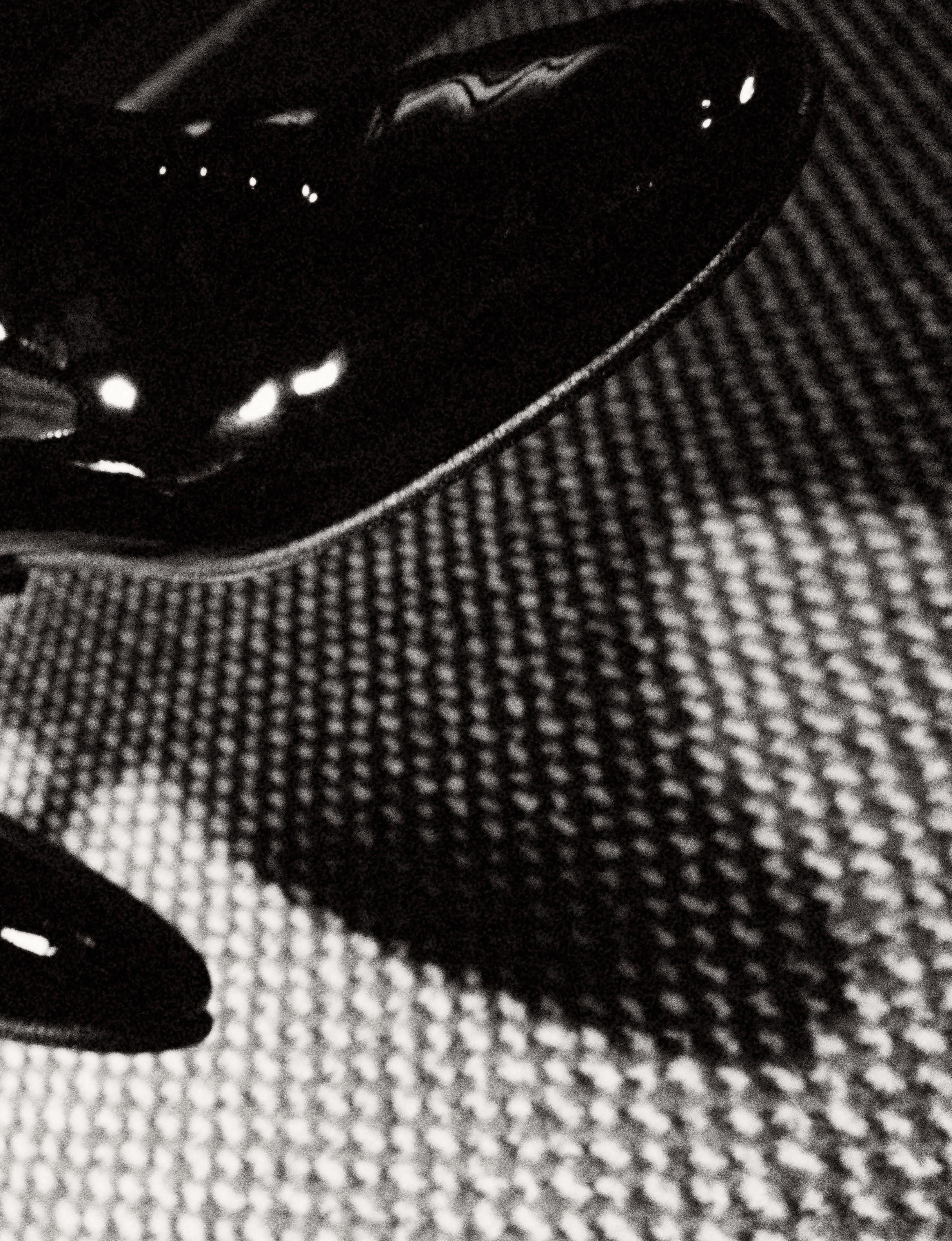

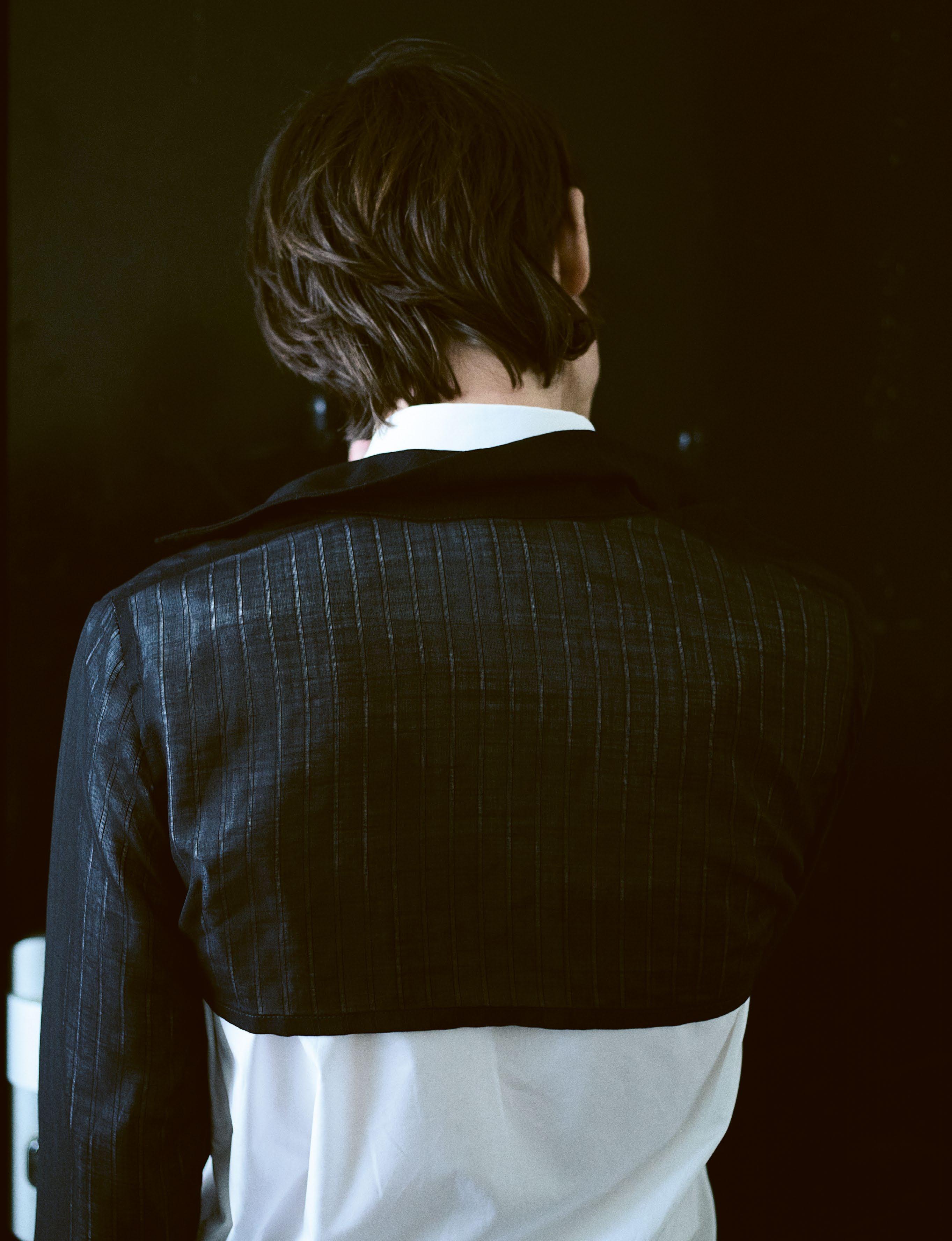

Ben Whishaw photographed in London by Chieska Fortune Smith, wears ALL FOOTWEAR

MANOLO BLAHNIK

Hari Nef photographed in New York by Bruce Gilden, wears CELINE throughout

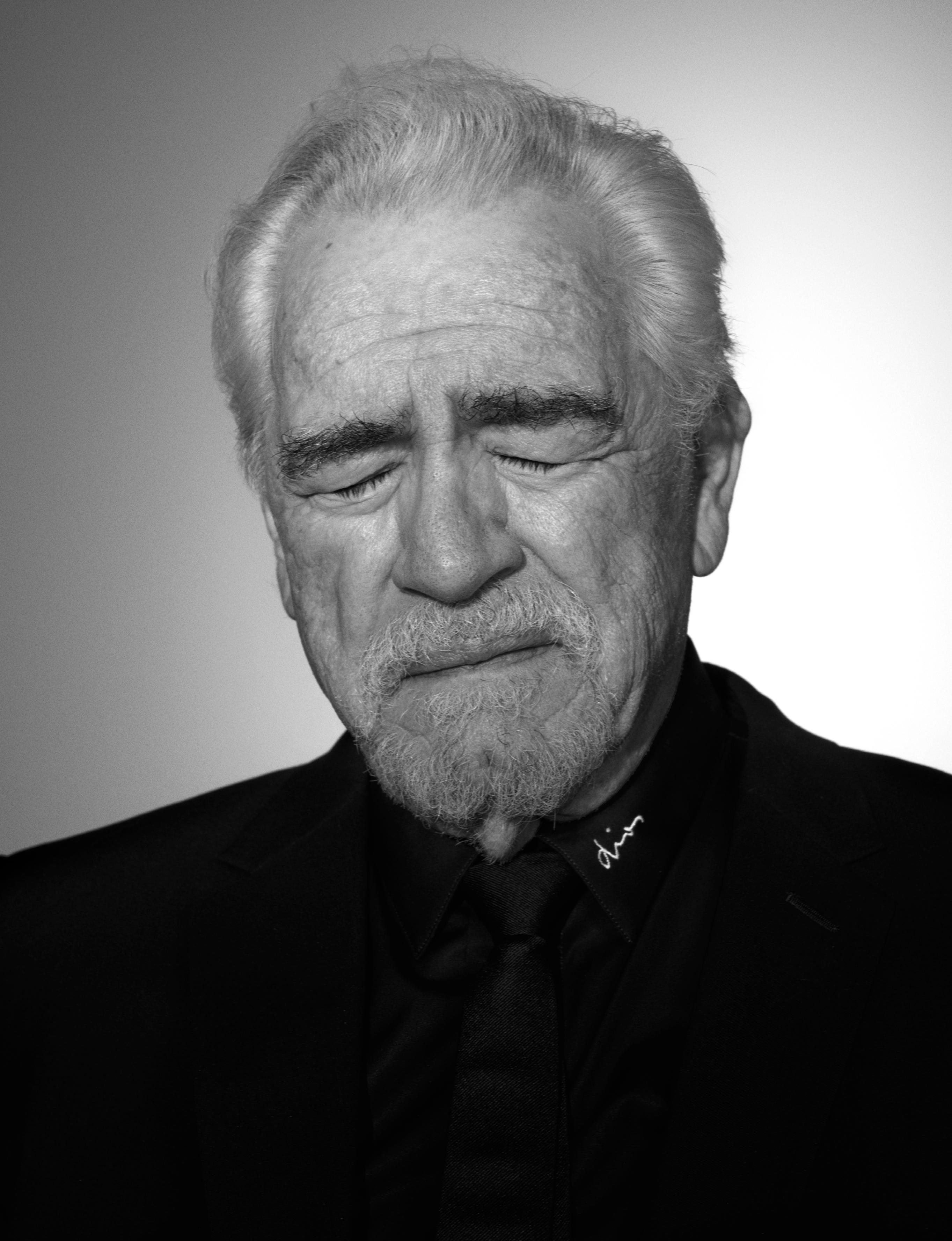

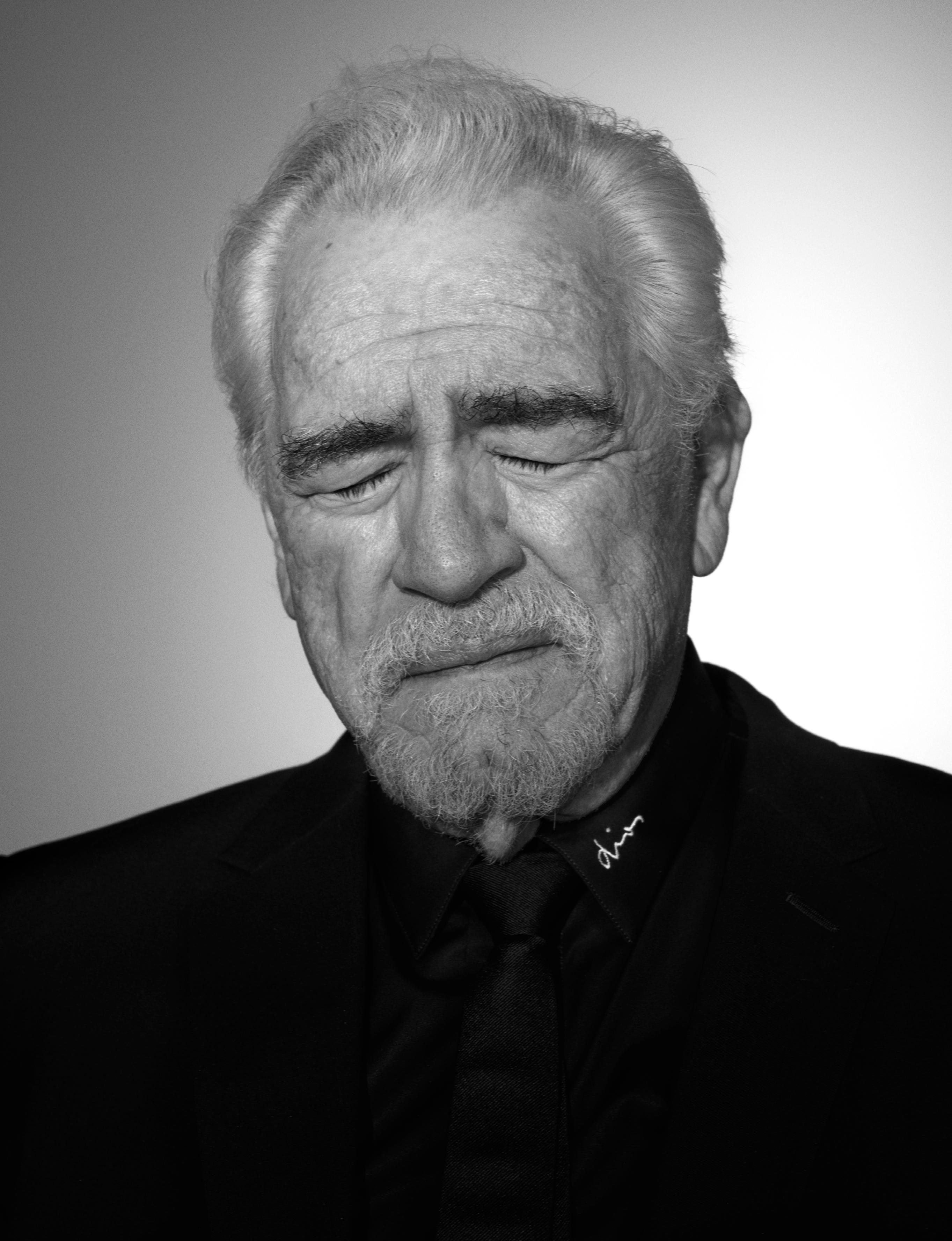

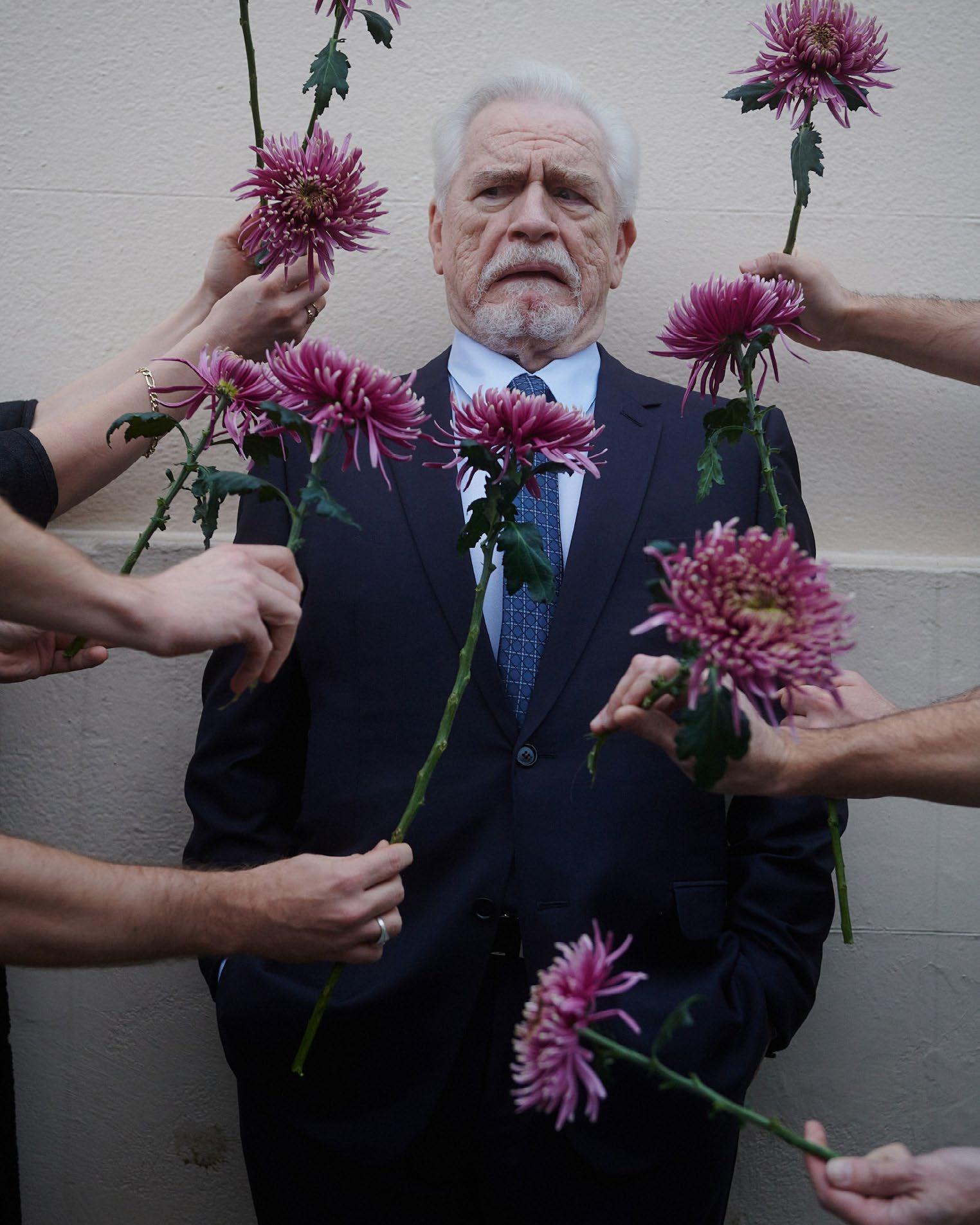

Brian Cox photographed in London by Tom Johnson, wears DIOR SS24 throughout

Ke Huy Quan photographed in LA by Buck Ellison, wears ZEGNA OASI LINO SUMMER 24

Jeremy Lee photographed in London by Sophie Green

“If you have food in your jaws you have solved all questions for the time being.”

Franz Kafka, ‘Investigations of a Dog’

tr. Willa & Edwin Muir

WORDS

Fedora Abu, Ayla Angelos, Chloë Ashby, Samir Chadha, Emmeline Clein, Marie Le Conte, Dan Crowe, Kerry Crowe, Jason Diamond, Fernanda Eberstadt, Katie Goh, Hannah Gold, Joshua Hendren, Tom Hiddleston, Jeremy Lee, Jenna Mahale, Isaac Rangaswami, Nikki Shaner-Bradford, Deyan Sudjic, Amelia Tait, Hannah Williams

PHOTOGRAPHY

Adam Barclay, Guy Bolongaro, Tex Bishop, Adrian Catalan, Angèle Châtenet, Lea Colombo, Buck Ellison, Ramak Fazel, Bruce Gilden, Sophie Green, Peter Guenzel, Marius W Hansen, George Harvey, Gianluca Di Ioia, Adama Jalloh, Tom Johnson, Nicolas Kern, Philippe Lacombe, Jelka von Langen & Roman Giebel, Crista Leonard, David Luraschi, Sufo Moncloa, Paolo Monti, Stanislas Motz-Neidhart, Jukka Ovaskainen, Louis de Rofgnac, Kuba Ryneiwicz, Jenna Saraco, Blommers & Schumm, Scheltens & Abbenes, Jo Metson

Scott, Chieska Fortune Smith, Dham Srifuengfung, Dongkyun Vak

ARTWORK

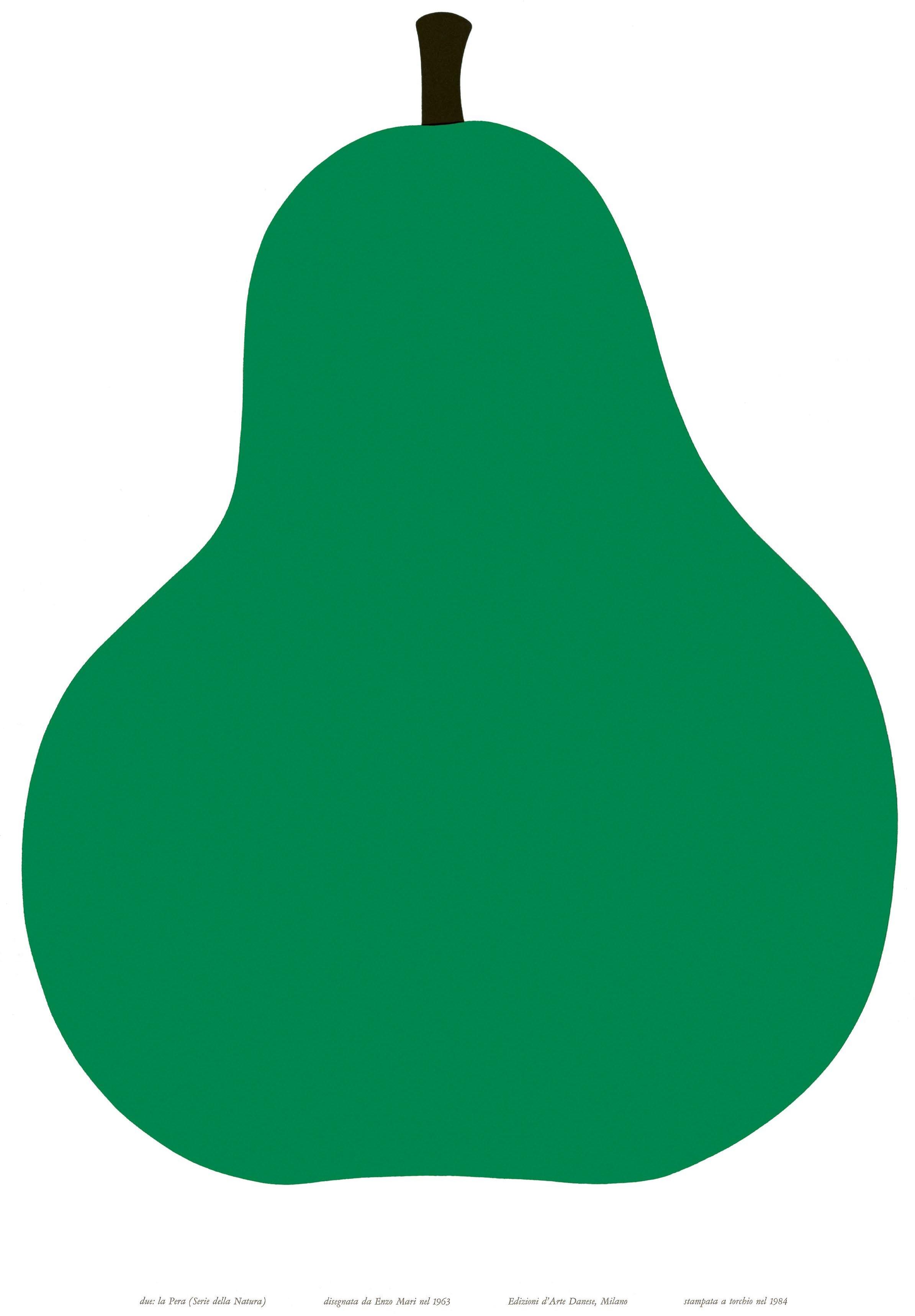

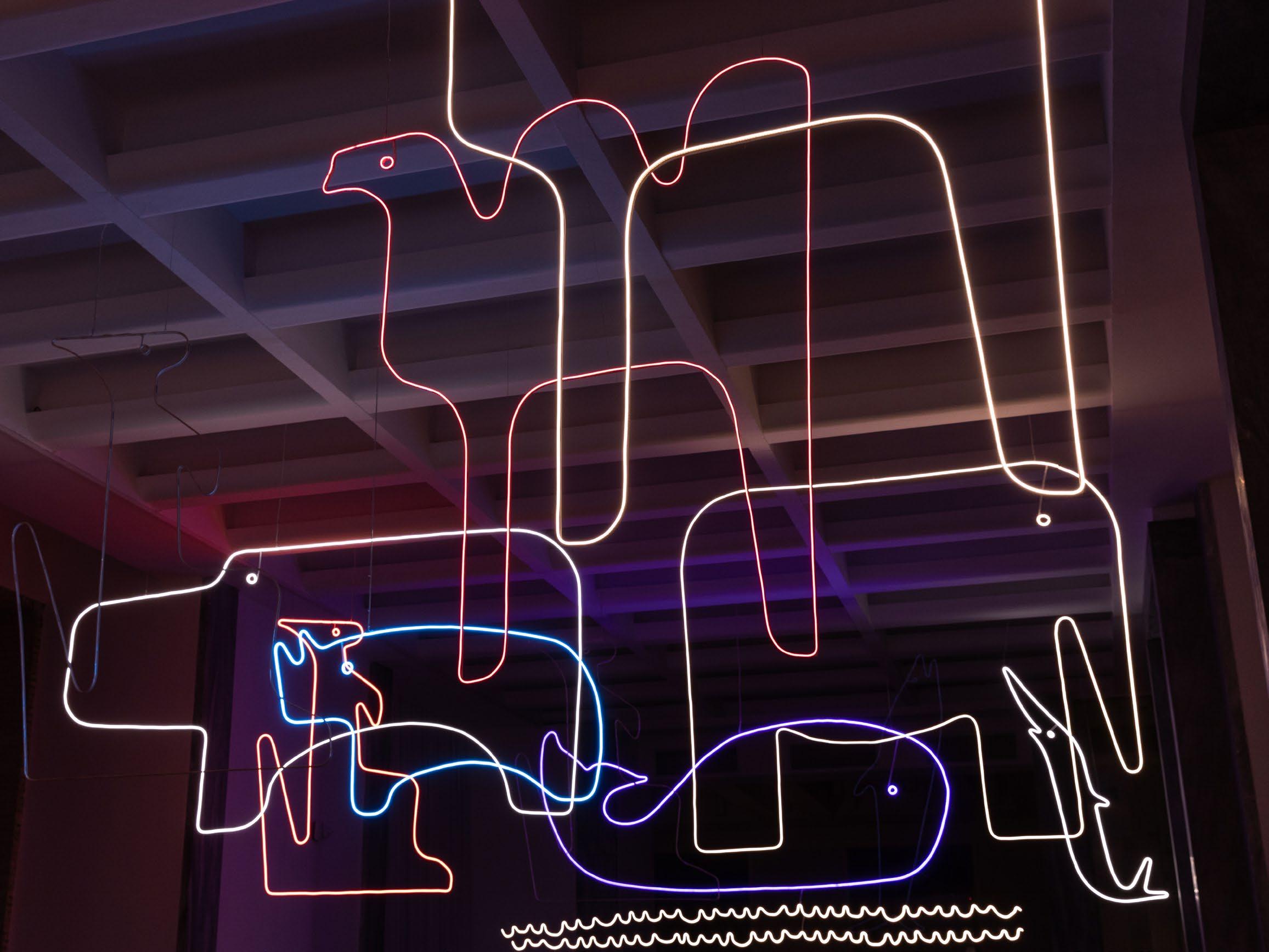

Antonio Citterio, Alec Doherty, Brian Ma Siy, Enzo Mari

PUBLISHER

Dan Crowe

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER

Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono

MANAGING DIRECTOR

Dan Crowe

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

Andrew Chidgey-Nakazono andrew@port-magazine.com

ACCOUNTS

Charlie Carne & Co.

CIRCULATION CONSULTANT

Logical Connections

Adam Long adam@logicalconnections.co.uk

CONTACT

info@port-magazine.com

SYNDICATED

SYNDICATION syndication@port-magazine.com

ISSUES Port China Port is published twice a year by Port Publishing Limited Somerset House, Strand London, WC2R 1LA port-magazine.com Port is printed by Park Communications Founded by Dan Crowe, Boris Stringer, Kuchar Swara and Matt Willey Registered in England no. 7328345 All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited. All prices are correct at time of going to press but are subject to change. All paper used in the production of this magazine comes, as you would expect, from sustainable sources.

24 MASTHEAD

25

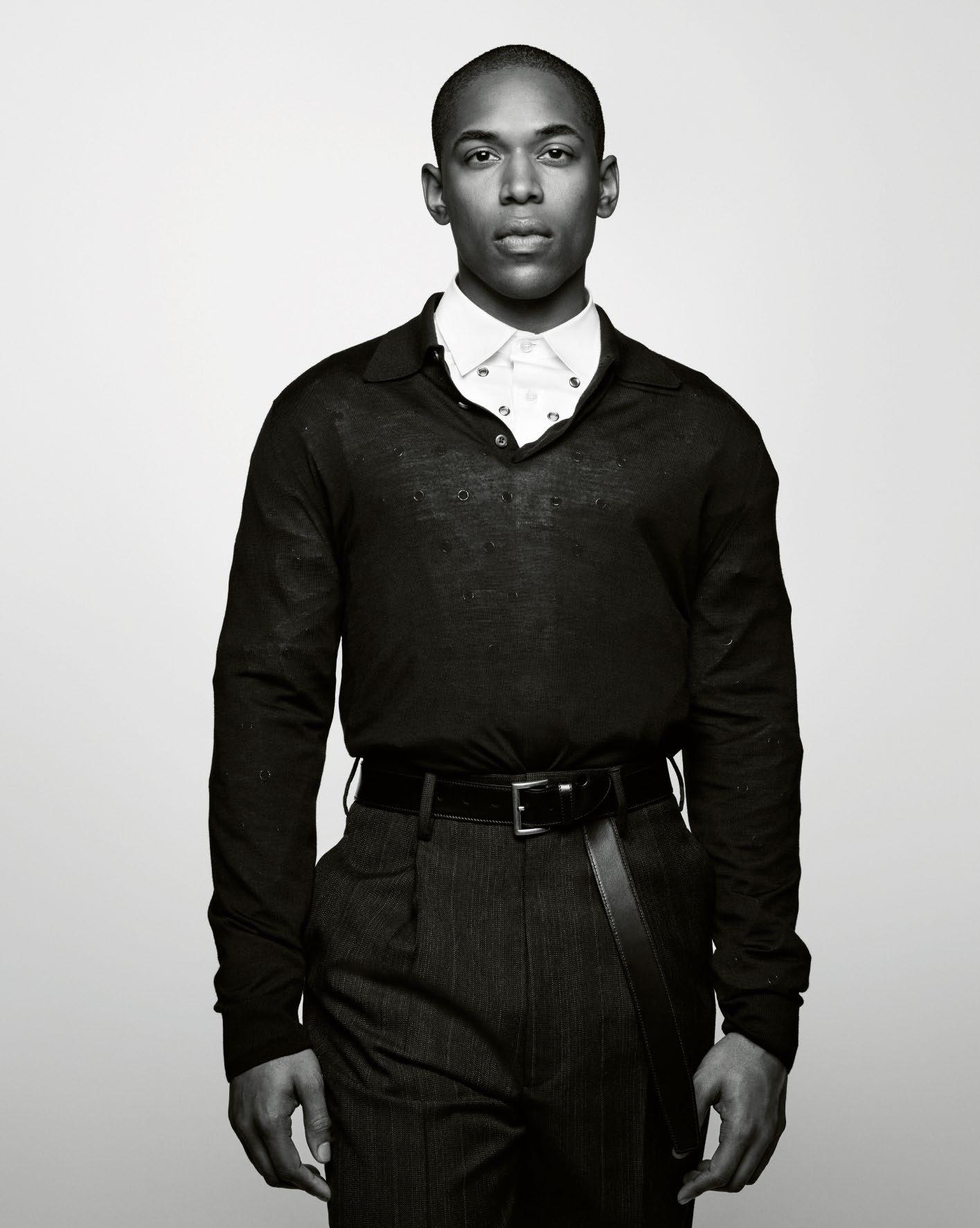

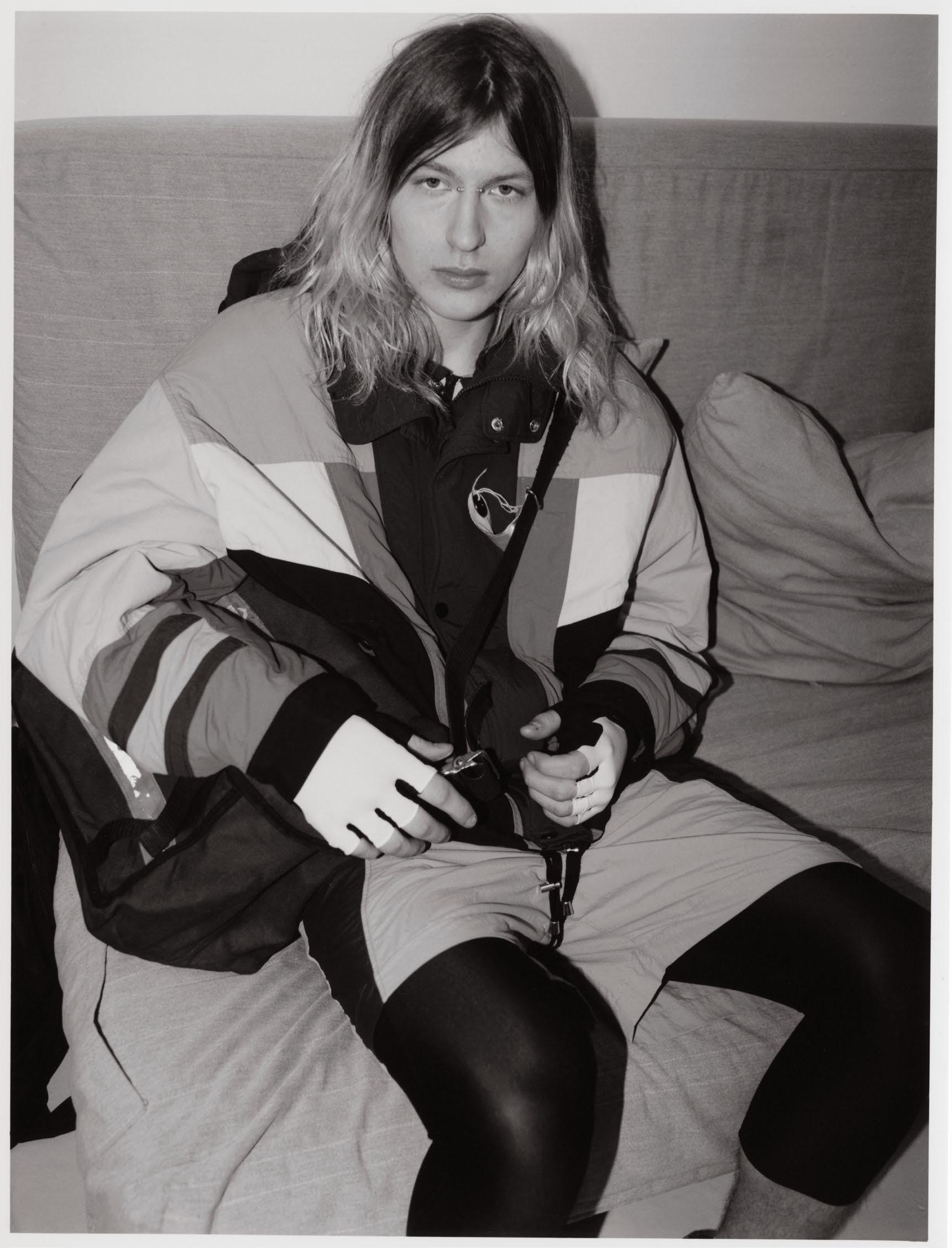

OUT-TAKE

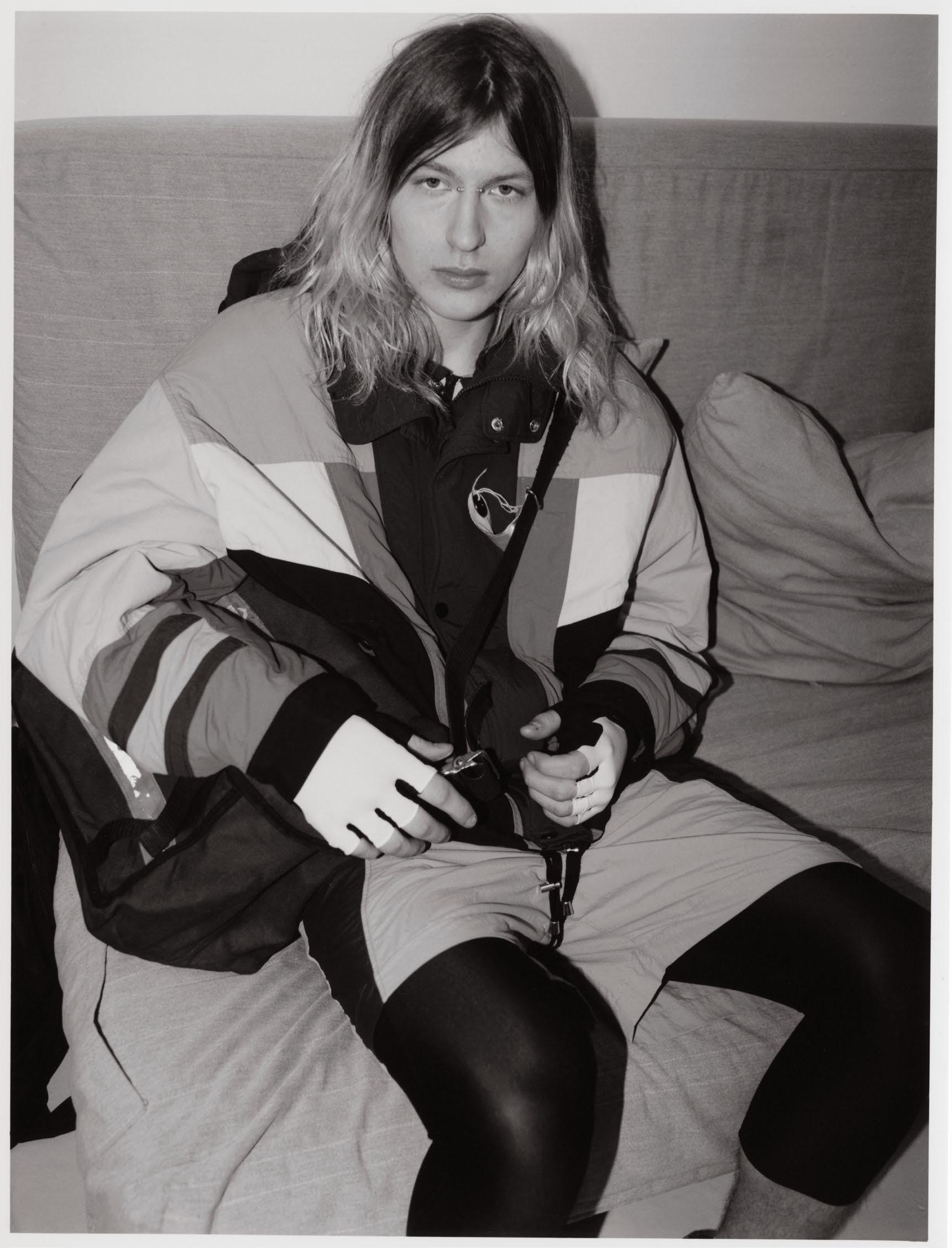

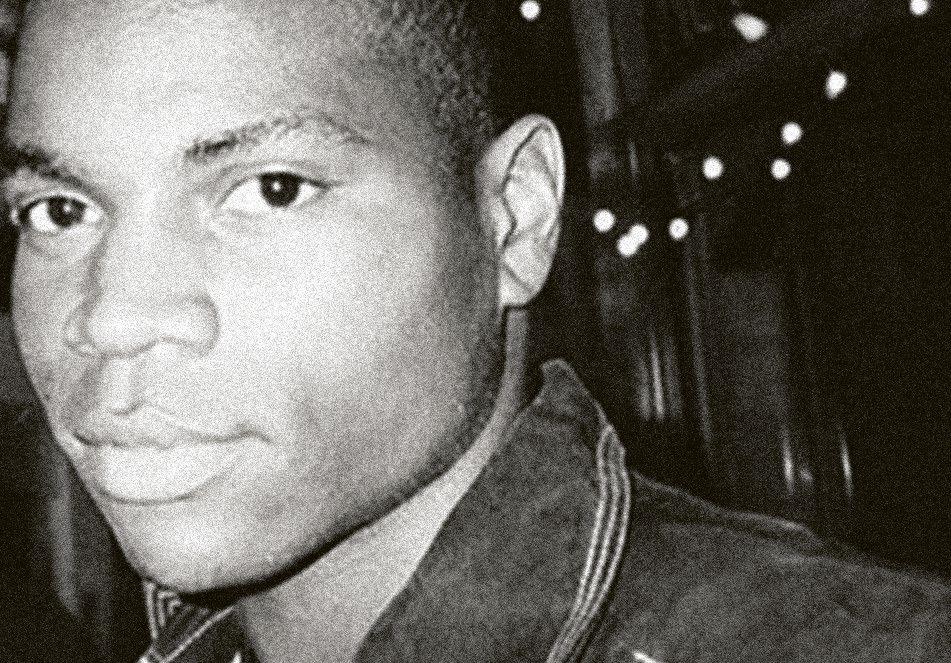

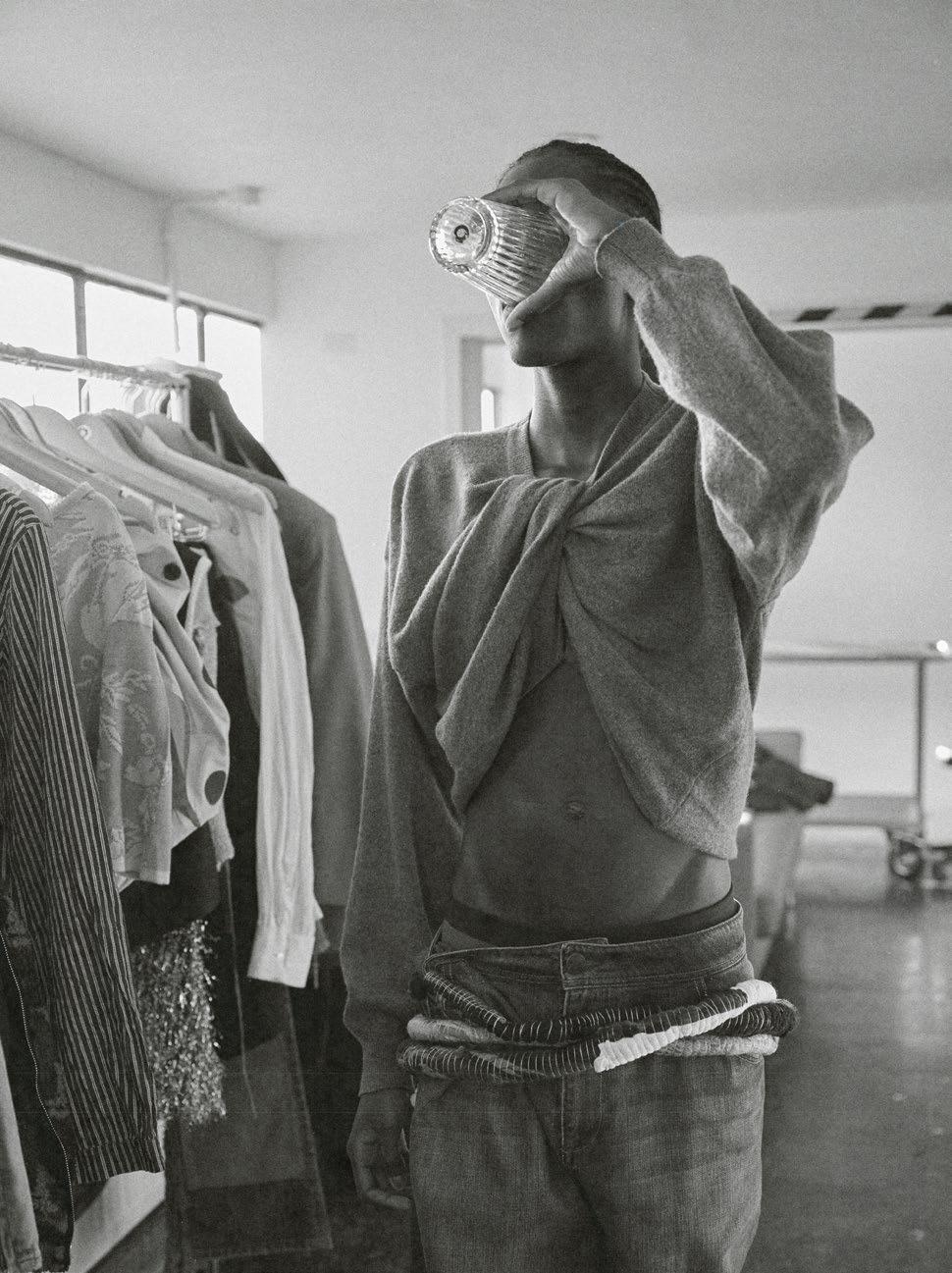

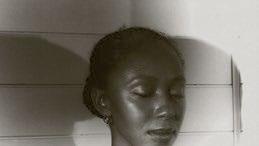

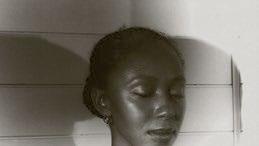

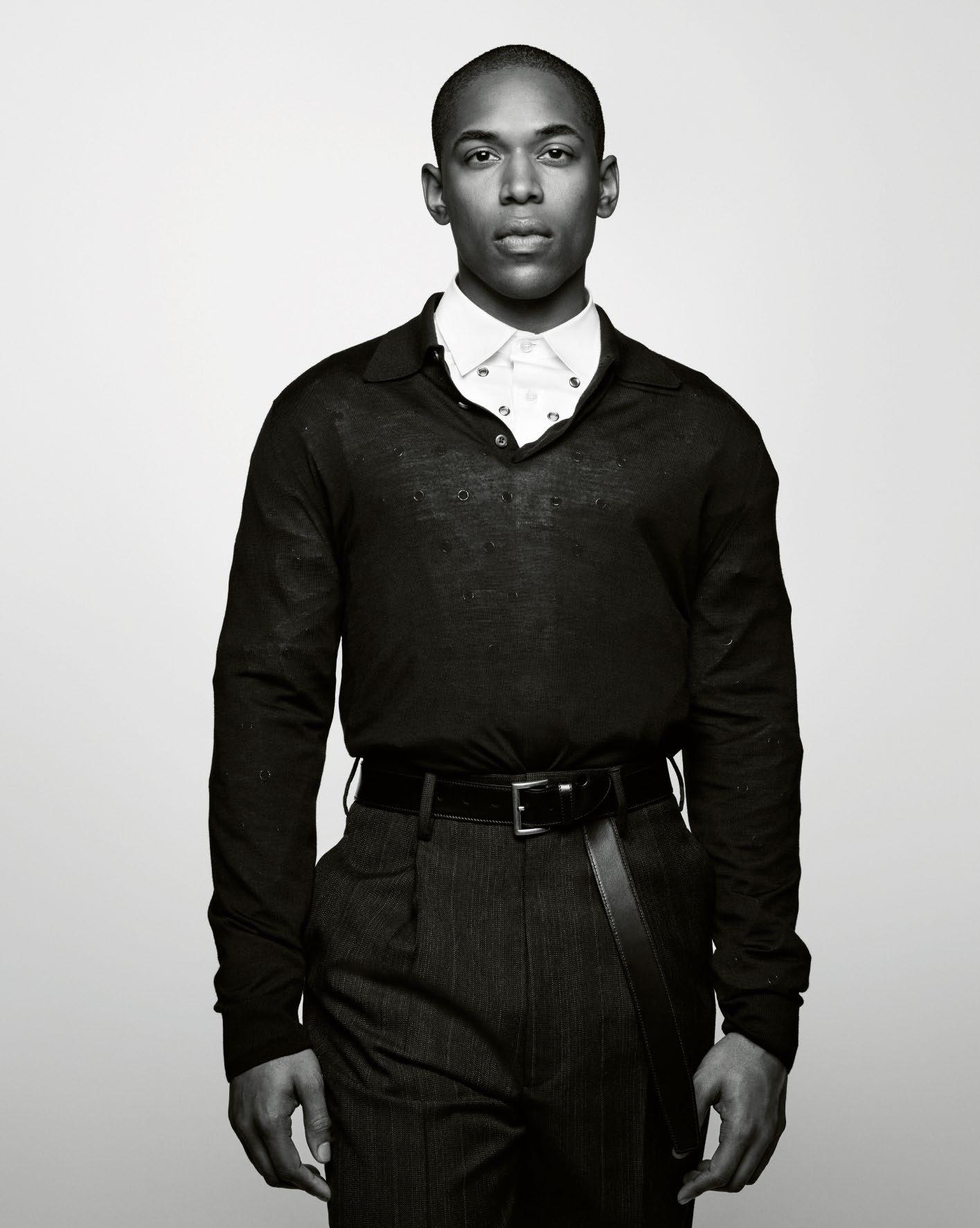

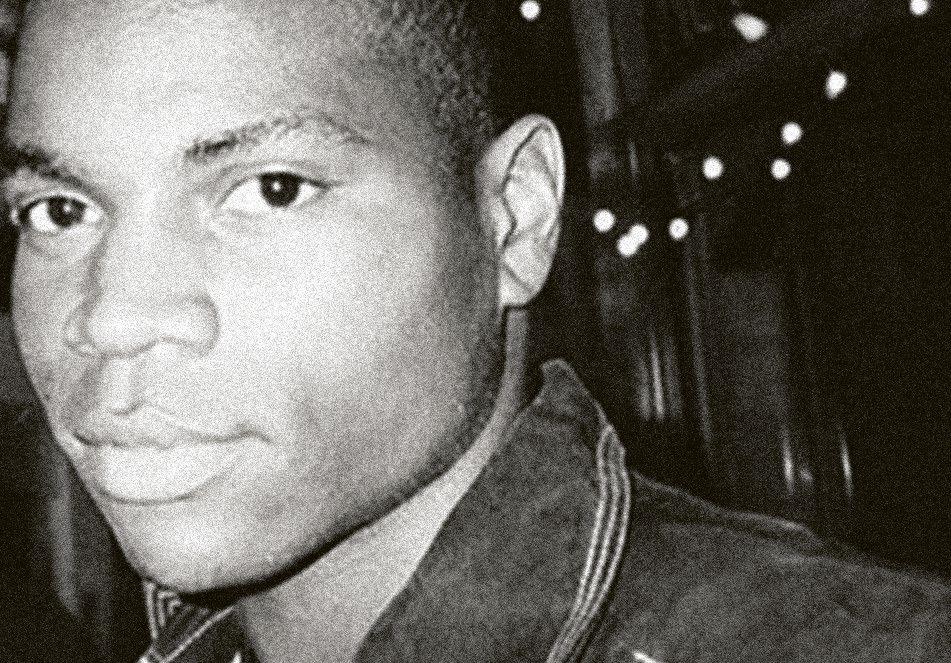

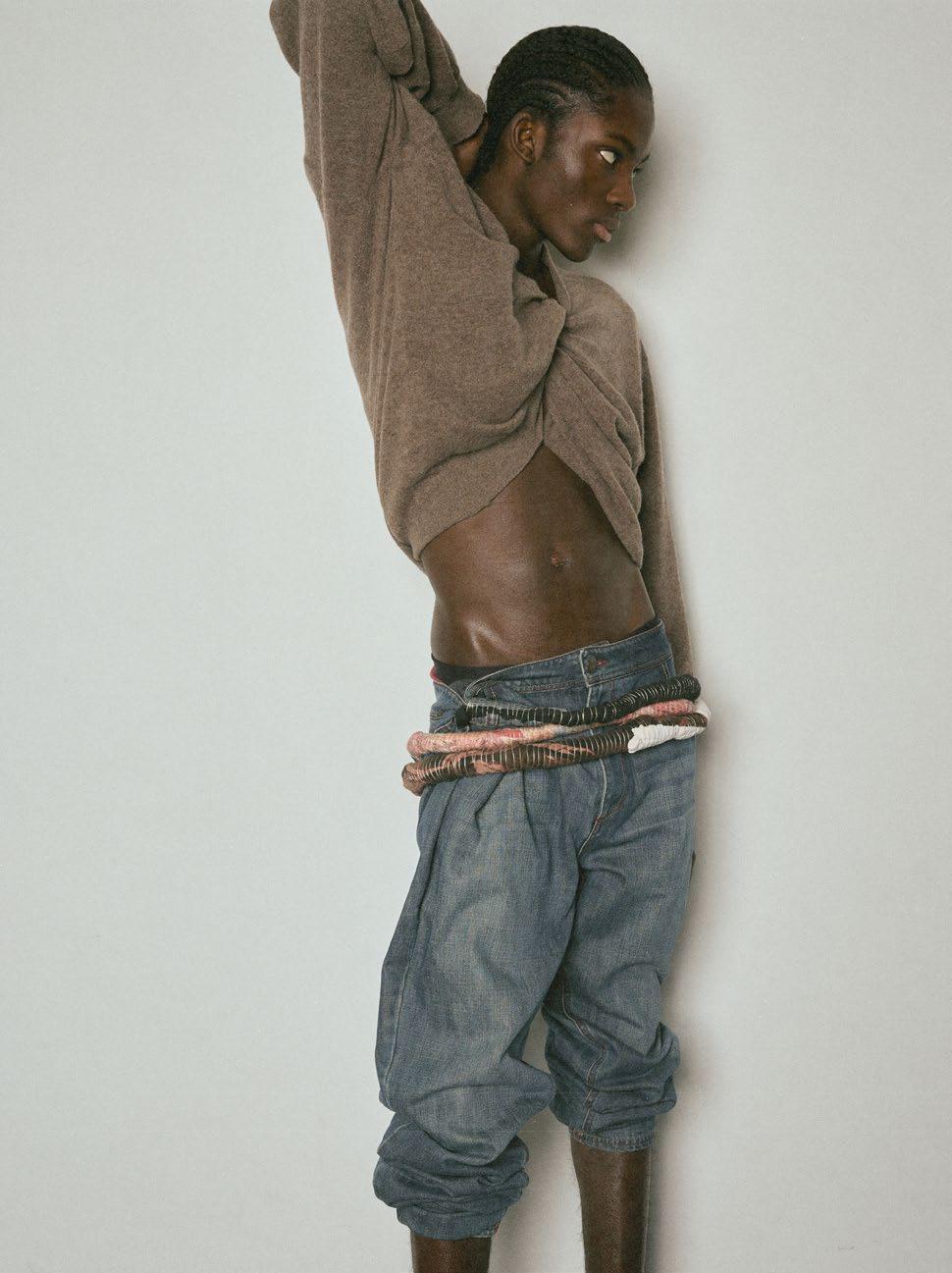

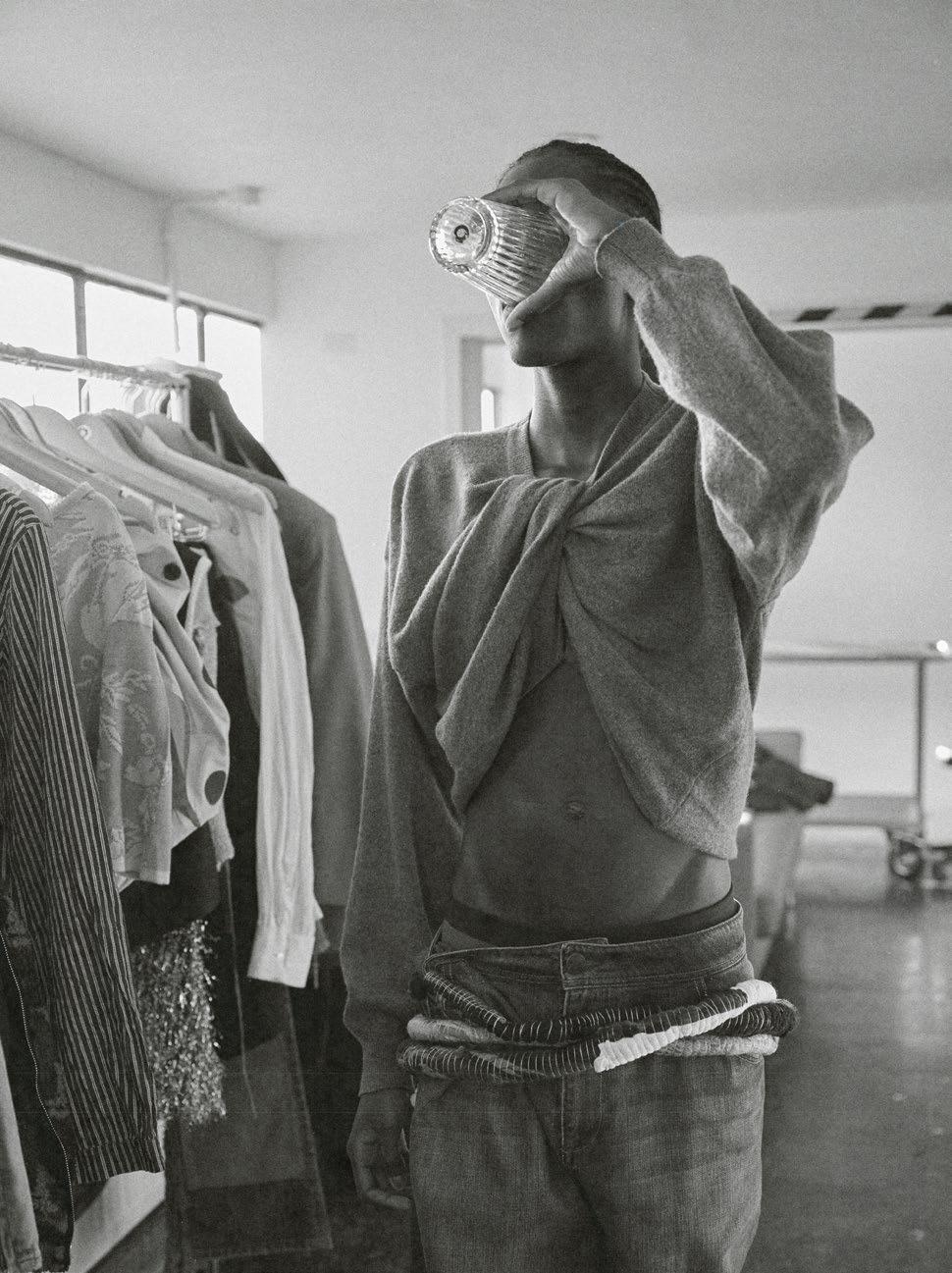

WE CATCH HARI NEF back home in New York after a whirlwind few months, busy with Fashion Weeks as well as awards season of the back of her role in Greta Gerwig’s Barbie. Here, she’s photographed with a fellow New Yorker by Bruce Gilden.

She is now making time for her writing – Hari’s been a columnist in the past, an era she describes as “trying to be some kind of self-styled Carrie Bradshaw”. Right now, she’s working on a screenplay as well as preparing for some new roles.

When the topic of yearning comes up, she seems unconvinced by the past, so we ask if she’s committed to the future. She tells us: “I’m afraid I am, but I think the future is overrated as an object of inquiry.”

Read the profile on page 104

26 OUTTAKE

27 PHOTOGRAPHY: BRUCE GILDEN

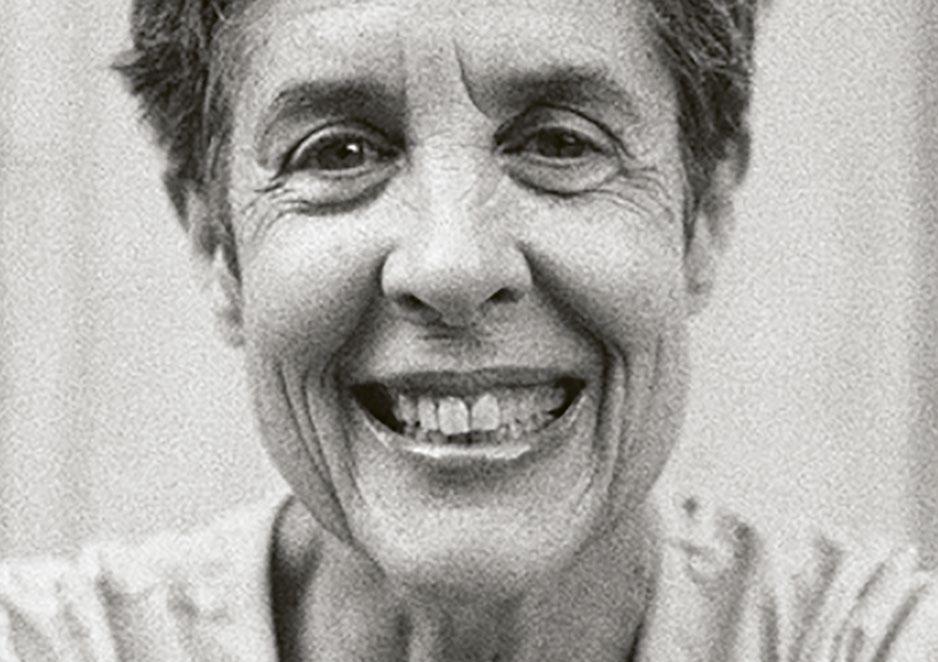

THERE IS A RICH history of food in magazines and journals stretching back to a time when newspapers only ofered cooking tips and recipes in small inserts, and good housekeeping was the lot of the housewife. How things have changed.

Often found in old books are snippings of cherished recipes, hidden to be found again by cooks such as this one, when turning the pages of Mum’s cookery books, or a fair few bought secondhand.

So, when asked to guest-edit an issue of Port dedicated to food, I wondered what a cook might bring to a journal. I found that, by curious chance, I could look up at the shelves over my desk – in the eaves of Quo Vadis, by a window overlooking the rooftops of Soho – and draw on not just books old and new but much else gathered over time. Sticking out of books were gems, like those pioneering articles in Vogue by Elizabeth David, who wove travel, photography and food onto the page, paving a mighty path, inspiring new generations.

There was a wealth of writing, photography and illustration such as those of John Broadley that adorn our menus (below) and those of Brian Ma Siy that illuminated the seminal menus at Alastair Little, just round the corner, where I had cooked so long ago.

First of there had to be lunch, laughter and chat and that with Fergus and Margot [Henderson], dear friends who were at the forefront of bringing British food and cooking centre stage. Rochelle Canteen is an idyll in east London, set in the playground of a school always planted and tended beautifully. Founded by Margot and Melanie Arnold, not far from St John where Fergus garnered great acclaim for nose-to-tail eating, the canteen is a family afair. Hector Henderson (Fergus and Margot’s son) is in the kitchen cooking alongside his best friend Jake Farley, both of whom have cooked at Quo Vadis, and they set forth a cracking lunch.

On being asked who was joining them in the issue, we reminisced on the last time Port had dedicated an issue to food – when Fergus was guest editor, with a remarkable portrait of the back of his head gracing the cover. I remember the excitement still.

Mention was made of talking with Hato Press about food and film, of visiting Corin Mellor at the factory built in Shefeld by his dad, David. Being at home sifting through pots, bowls, cupboards and a few pestle and mortars. Talking with Joké Bakare, who had cooked a dinner at QV prior to opening her tremendous restaurant. There was breakfast in Bethnal Green at E Pellicci’s with Ray Winstone, both

of whom need no introduction, and further afield, the food culture of Seoul discussed by Katie Chung, creative director of MCM. There is Ben Whishaw eating at Quo Vadis, and a visit to venerable and beloved Sweetings in the City of London, famed for, among much, a silver tankard of black velvet, made with Guinness and champagne. There is a perusing of the art on the walls of George in Mayfair, then wandering down the road to visit Ollie Dabbous at Hide on Piccadilly.

Food and cooking feed a fundamental need – not just of necessity, but also to please – and so it is unsurprising, really, to find food appearing in art, in film, theatre, in books, newspapers and of course, in a magazine. Talk over lunch continues amid laughter and wine and leads to mention of fashion, food and cooking, art, photography, the curious business of artlessness and style in what we prepare, wear, see and choose to look at, read, watch and take inspiration from. A great adventure.

’Tis a very great joy and a very great honour to be here talking with you, and I hope you enjoy this issue of Port as much as I enjoyed wearing an editor cap for the first time.

Jeremy Lee, Guest Editor

EDITOR’S LETTER

28 EDITOR’S LETTER

42 INSISTENT AND BEYOND CHOICE Chloë Ashby 46 DELECTABLE TRINKETS Joshua Hendren 48 BUTTER. BUTTER. BUTTER. BUTTER. BUTTER. BUTTER Amelia Tait 52 CLATTERING FISH KNIVES AND SCRAPING STOOL LEGS Isaac Rangaswami 54 PULL THE FRUIT APART Katie Goh 58 PETITES MAINS Fedora Abu 60 POMELLO SOURS 62 DESIGNED FOR THAT DAY Samir Chadha 64 WASH IT ALL DOWN Marie Le Conte PORTFOLIO 30 CONTENTS

FEATURES

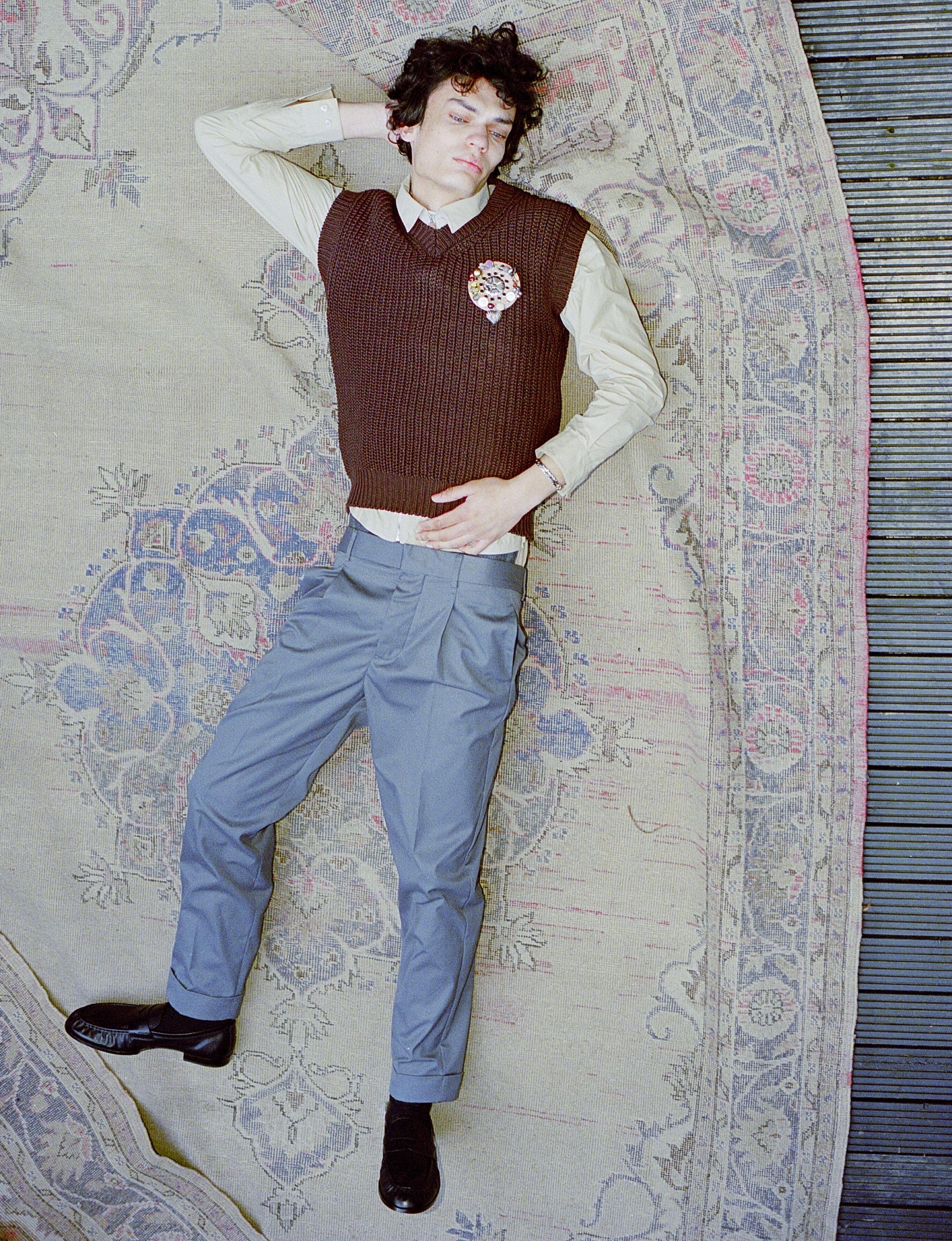

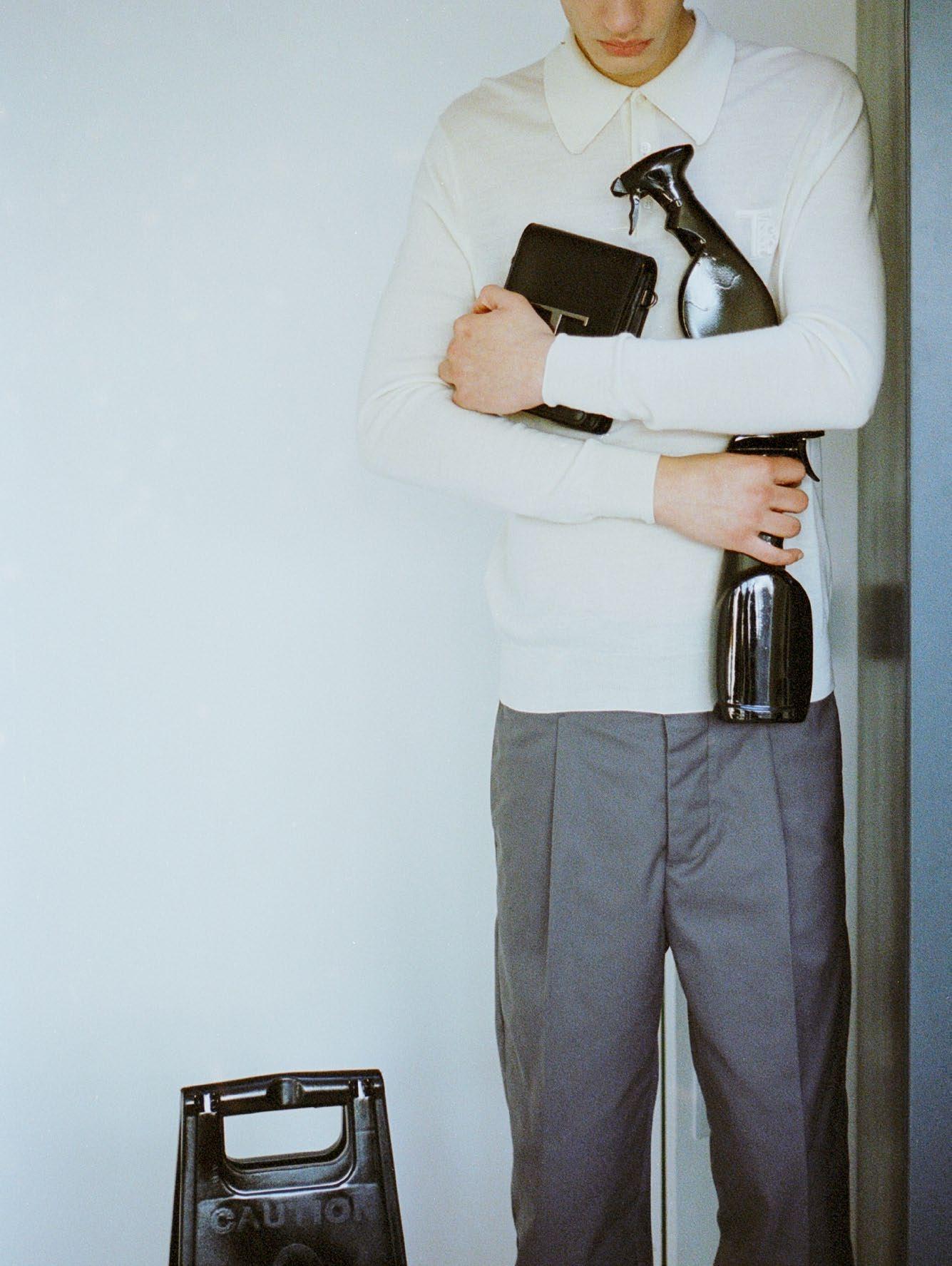

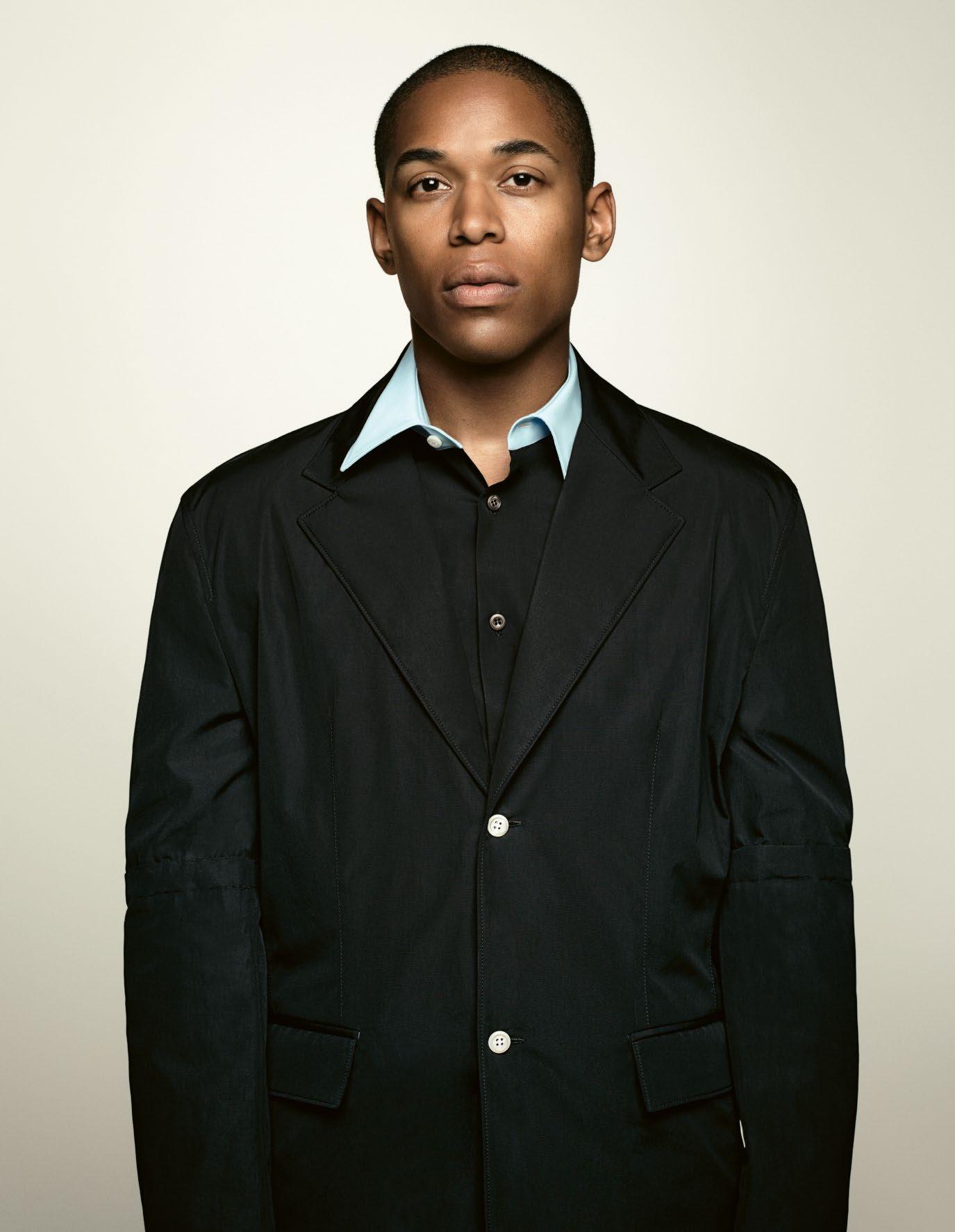

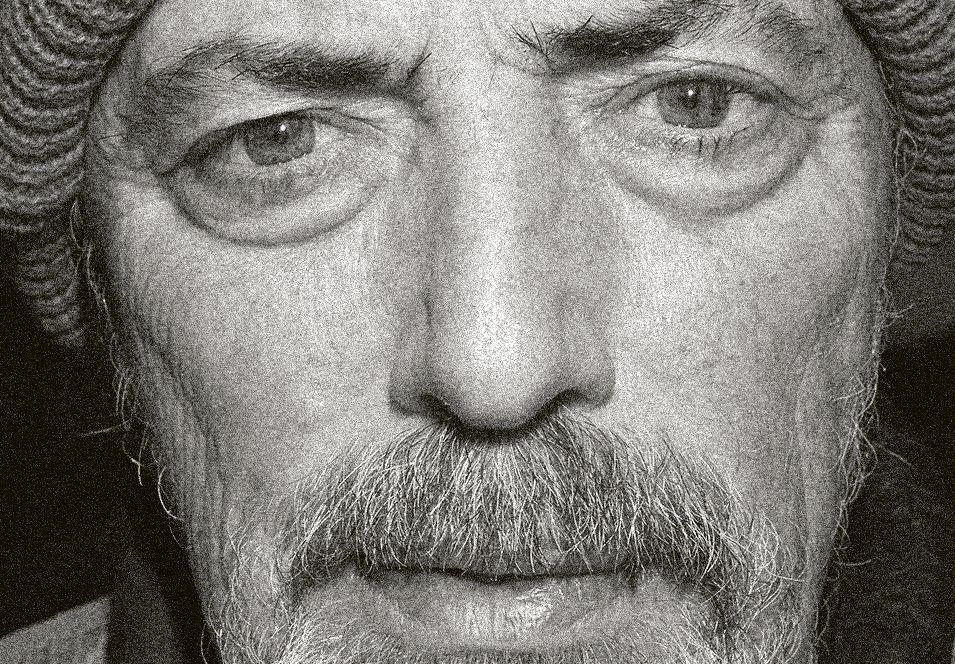

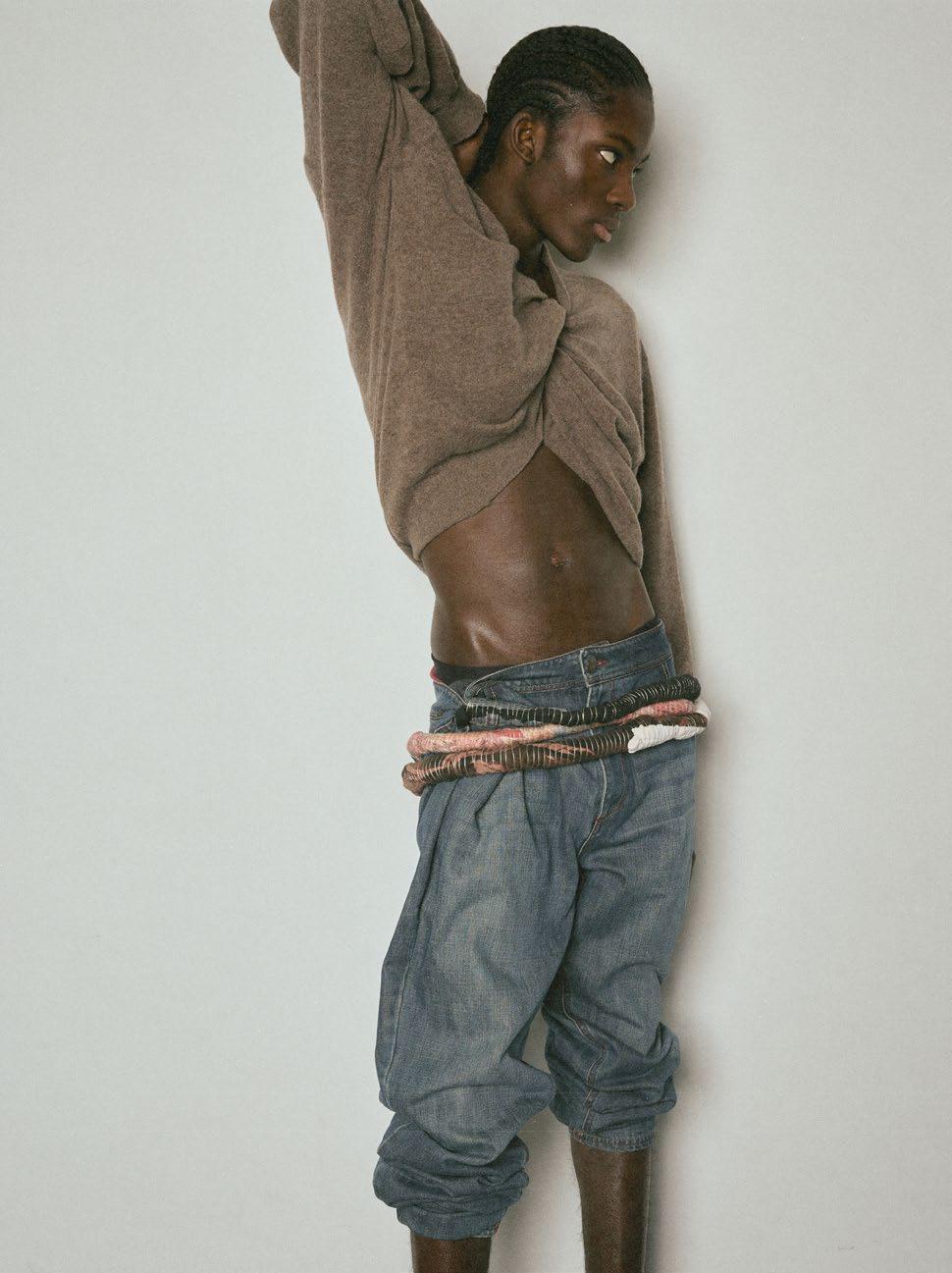

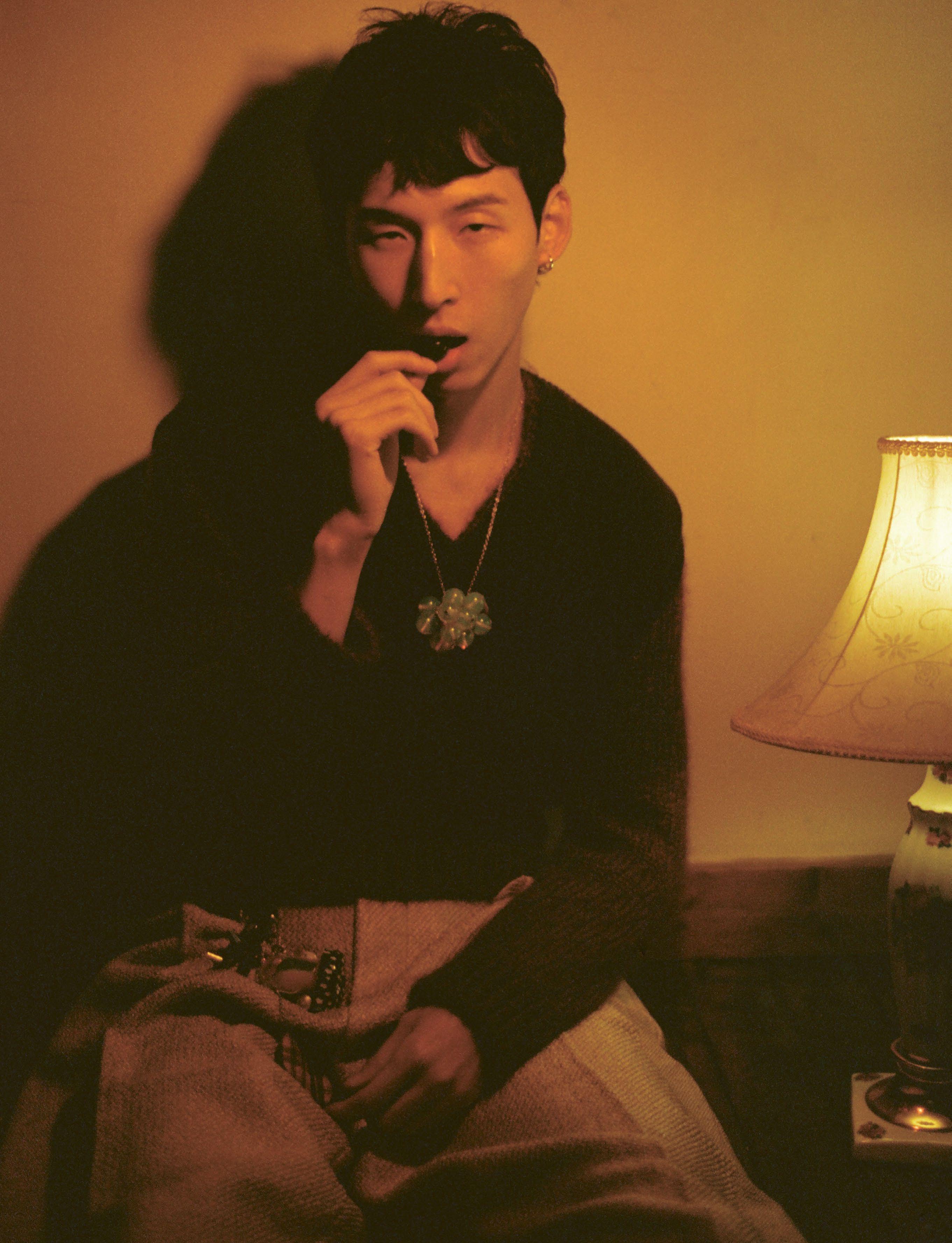

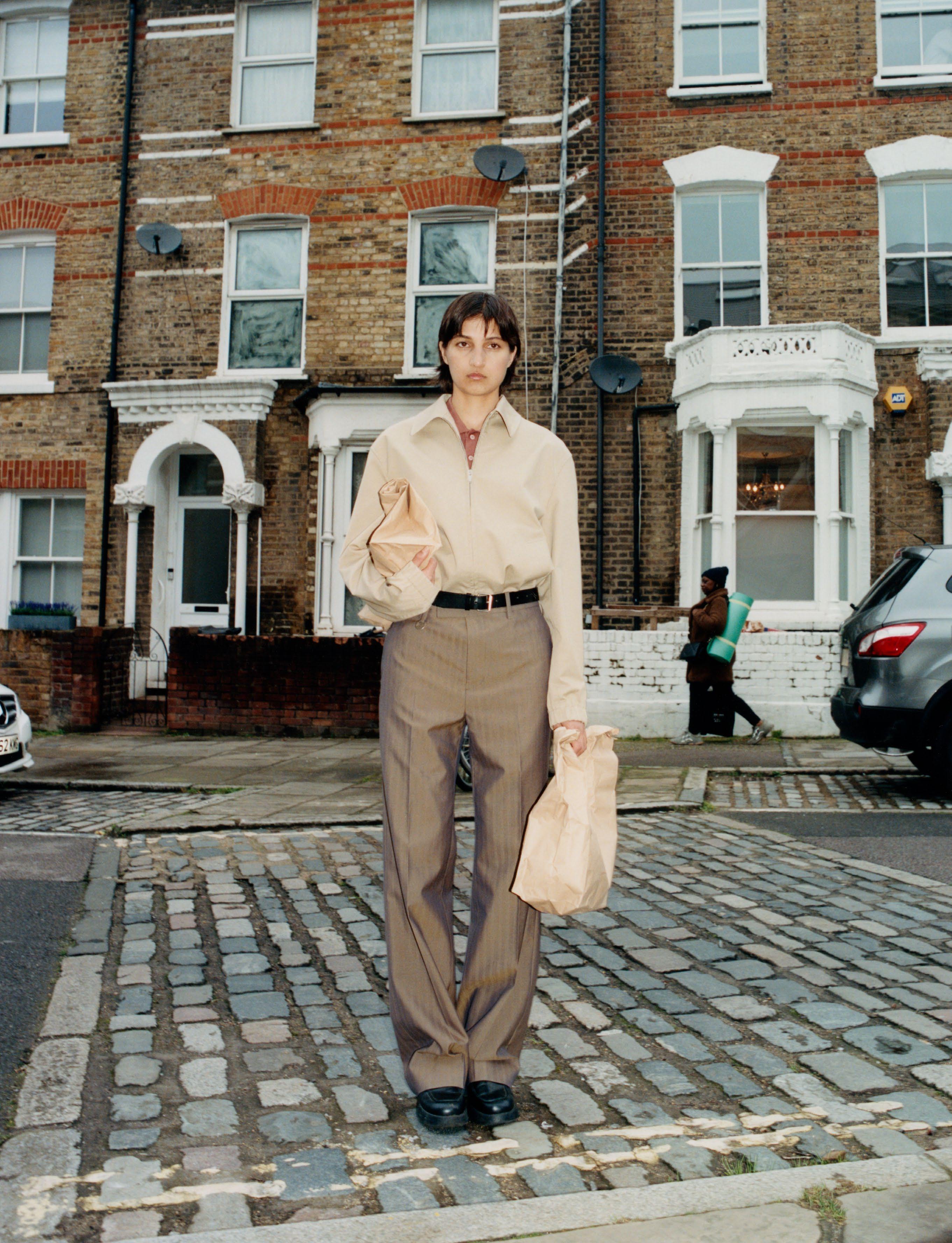

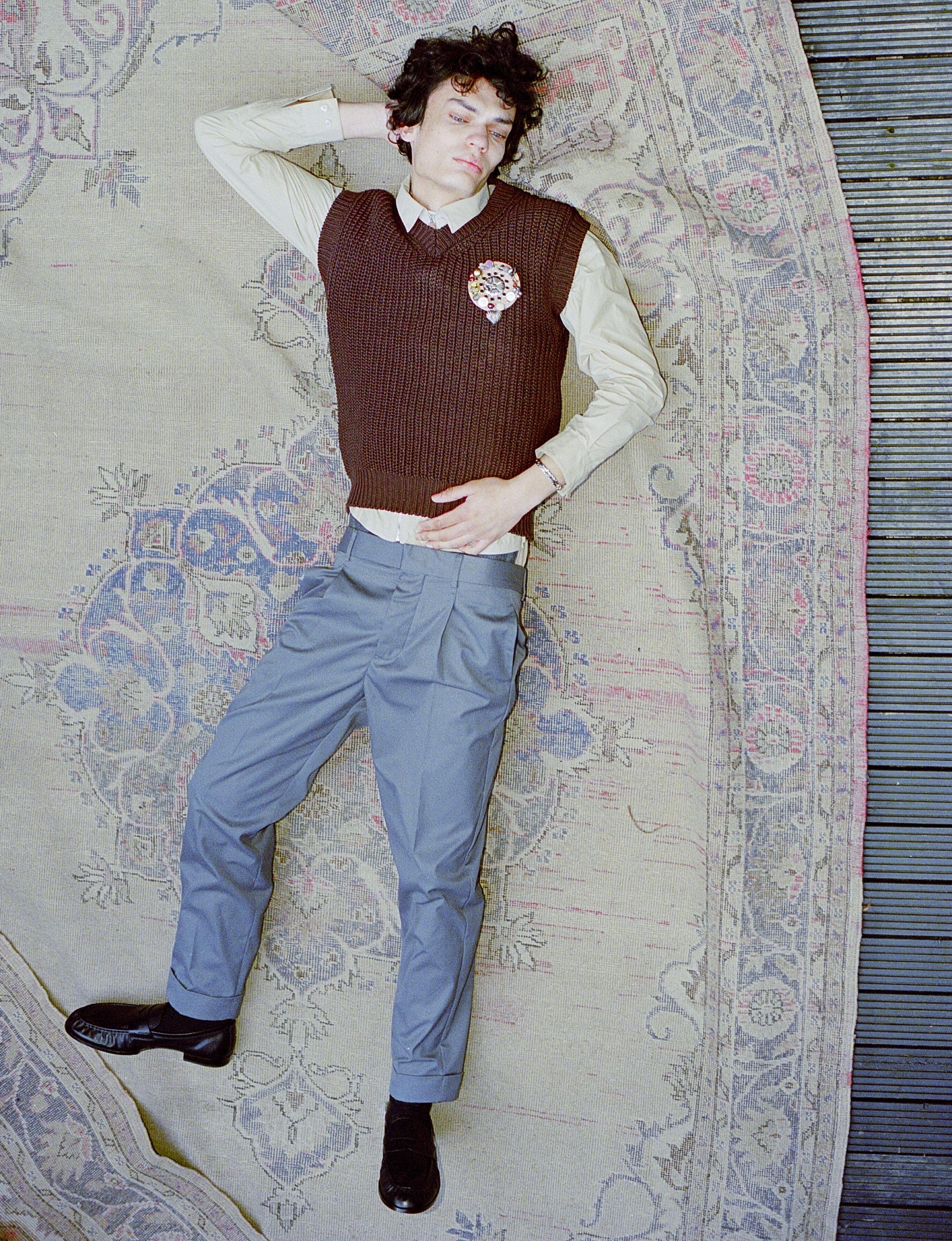

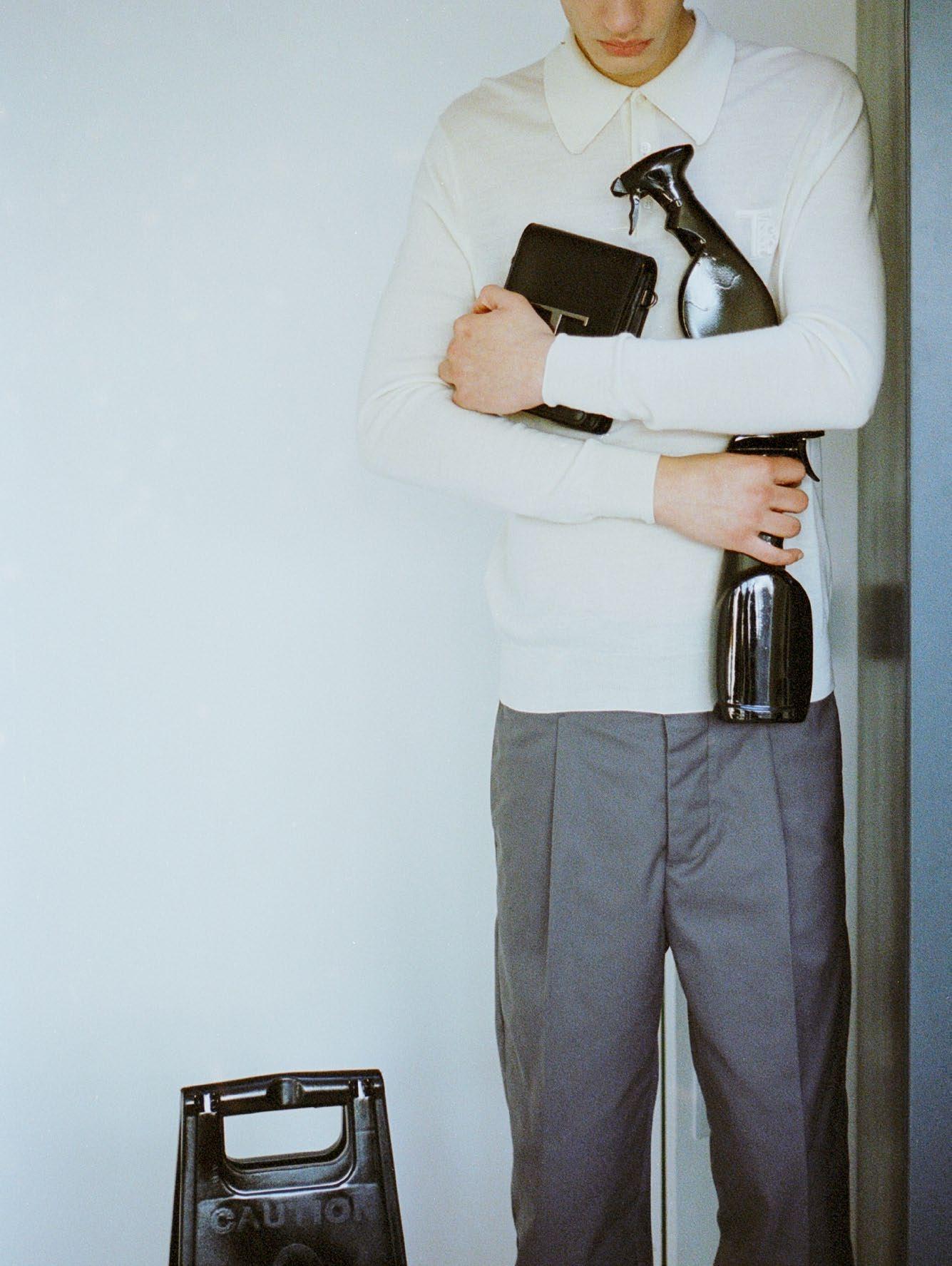

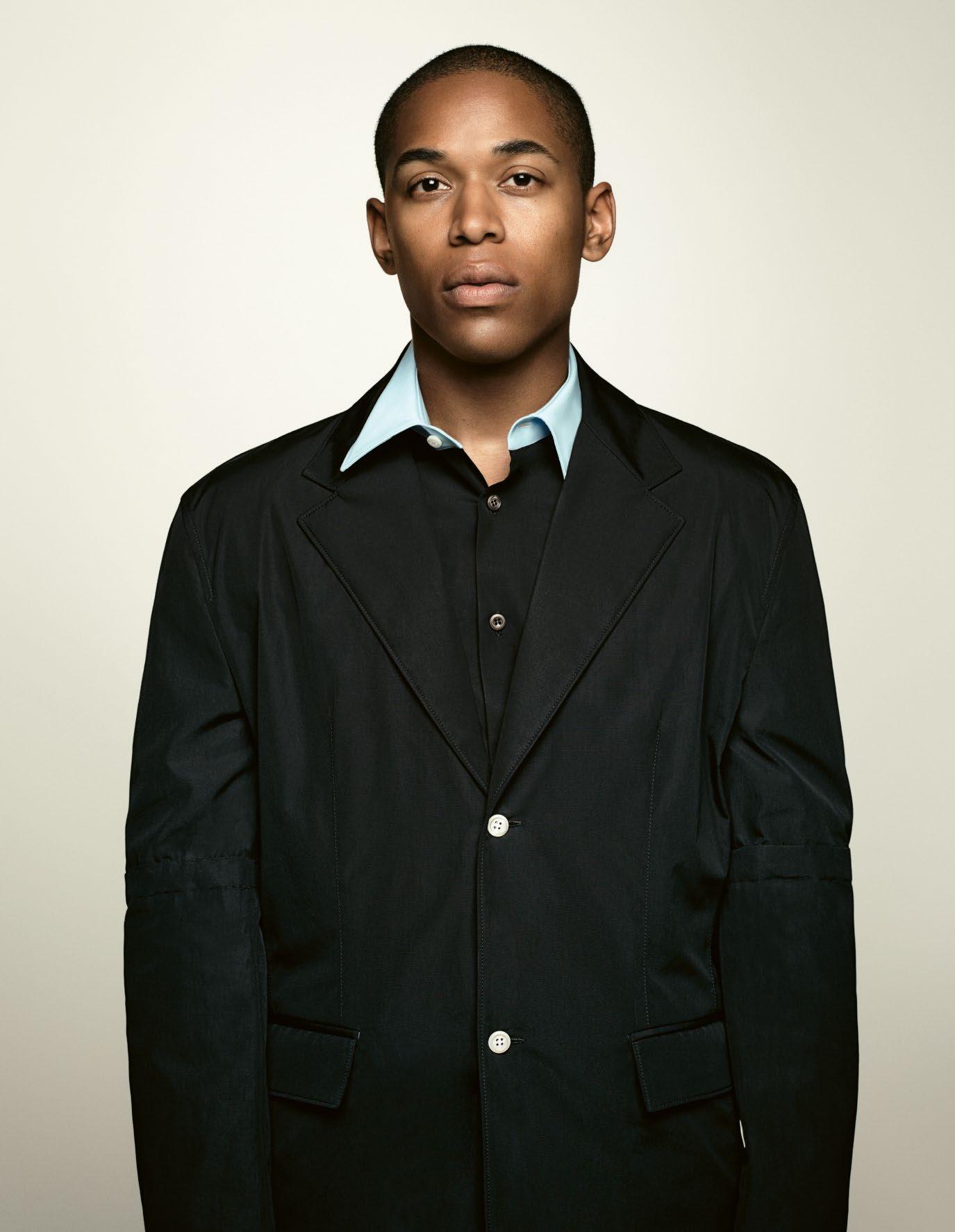

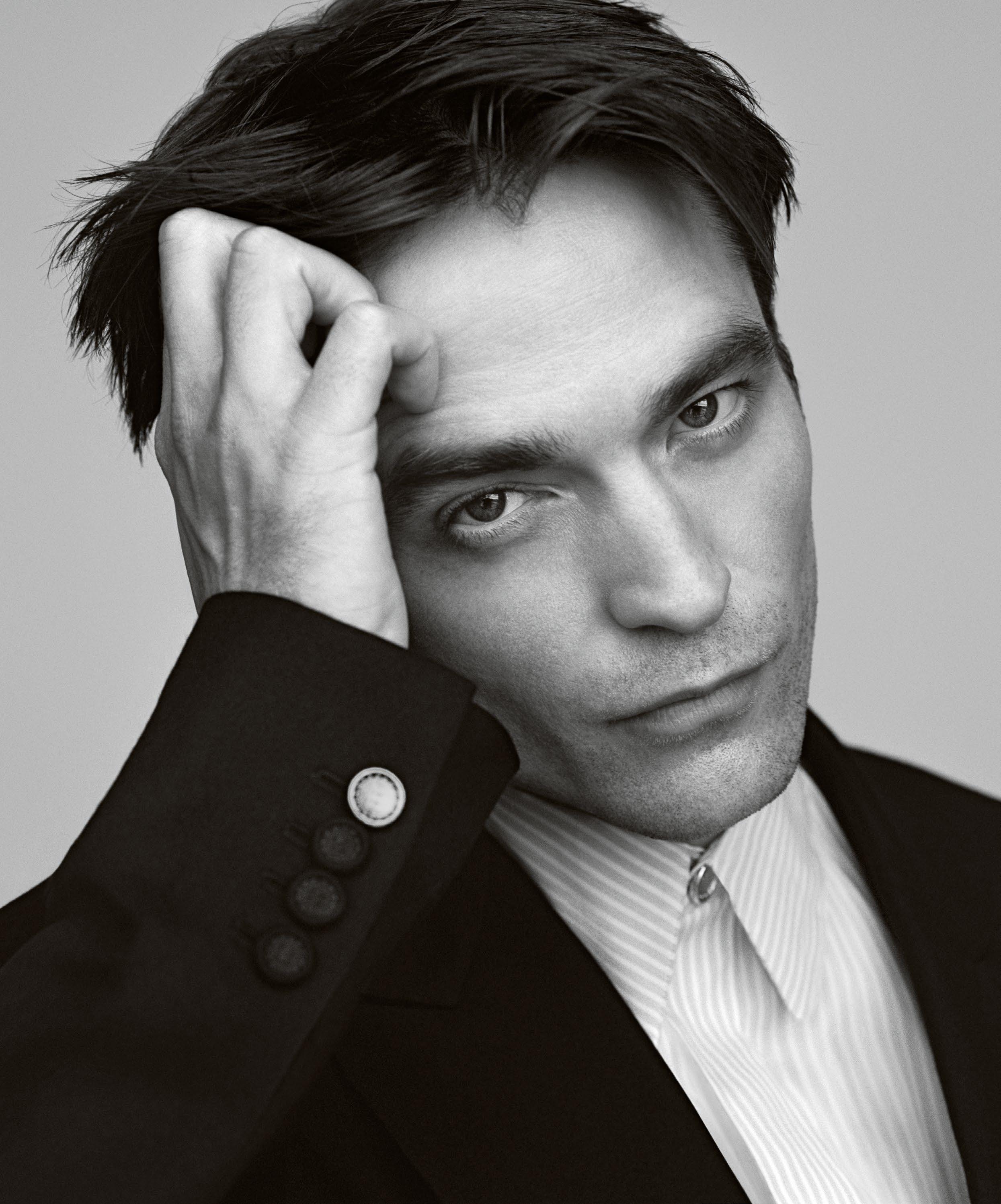

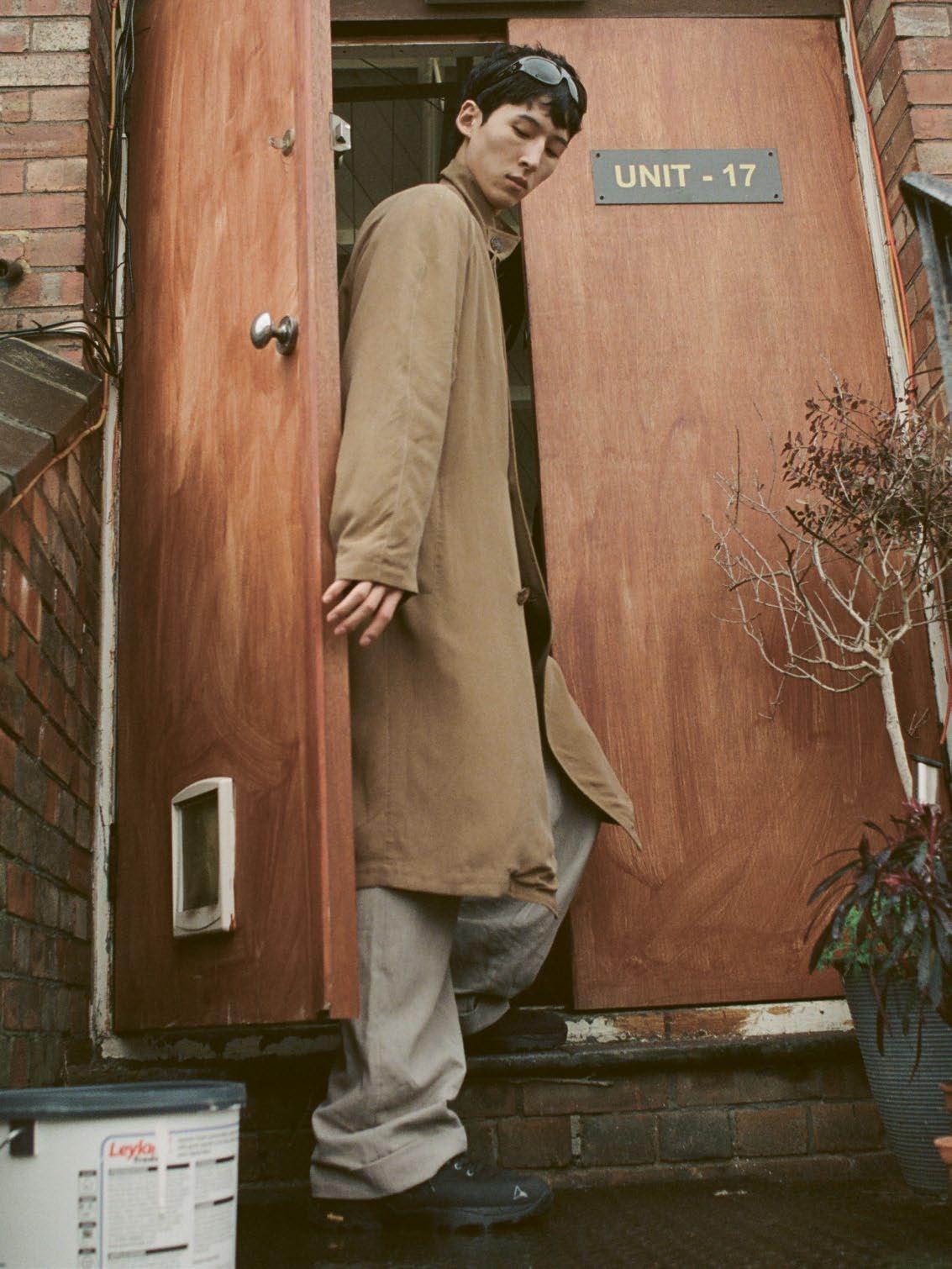

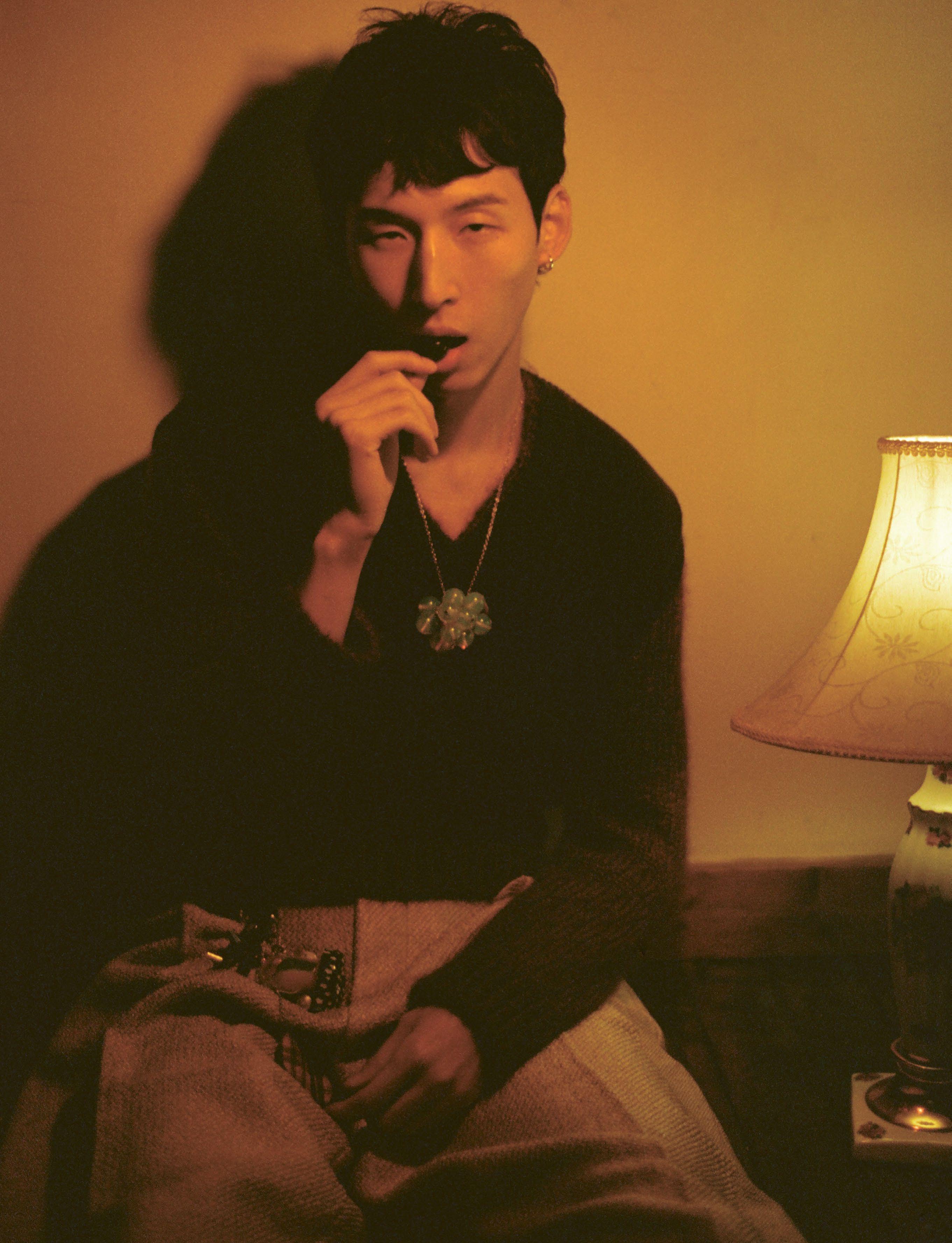

70 GELLING THE FRIENDSHIP Lunch with Jeremy Lee, Fergus Henderson and Margot Henderson Interview Samir Chadha Photography Sophie Green 78 AREAS FOR CHANGE Katie Chung, MCM’s creative director, discusses her work and her tastes Words Jenna Mahale Photography Dongkyun Vak 79 HEAVEN SCENT A new book from Louis Vuitton traces the roots of key scents Words Samir Chadha Photography Adam Barclay 80 BEN WHISHAW The Passages and Paddington star discusses his career to date Words Kerry Crowe Photography Chieska Fortune Smith 94 CANINES, CANVASES An art tour of Mayfair’s George club Words Hannah Williams Photography Jukka Ovaskainen 100 INGREDIENTS AND SAVOIR FAIRE Maxime Frédéric talks about his approach to cooking Words Jenna Mahale Photography Philippe Lacombe 104 HARI NEF The actress and model thinks about what’s next Words Hannah Gold Photography Bruce Gilden 114 OF SHELVES, CUPBOARDS AND POTS A selection of kitchen contents and cookware Words Jeremy Lee Photography Jo Metson Scott 122 COOKING WITH SCORSESE Kenjiro Kirton and Jeremy Lee discuss iconic food moments in film Interview Jeremy Lee and Port 128 KE HUY QUAN Discussing a triumphant return to acting with a dear friend Interview Tom Hiddleston Photography Buck Ellison 138 UNEXPECTED HARMONIES Ollie Dabbous chats about his approach to cooking and serving Words Hannah Williams Photography Dham Srifuengfung 142 RAY WINSTONE Catching up with a London icon Interview Dan Crowe Photography Tex Bishop 148 DETAIL THAT SHAPES Up close with Chanel’s mini additions to the Coco Crush line Words Fedora Abu Photography Stanislas Motz-Neidhart 152 FABRIC INSTINCT Designers thinking diferently about Fabric Words Jenna Mahale Photography Jenna Saraco 160 NEVER BREAD AND BUTTER Joké Bakare talks about her Michelin-winning cooking philosophy Interview Jeremy Lee Photography Adama Jalloh 162 BRIAN COX The veteran reflects on how far he’s come, and how much he’s yet to do Words Jason Diamond Photography Tom Johnson

31

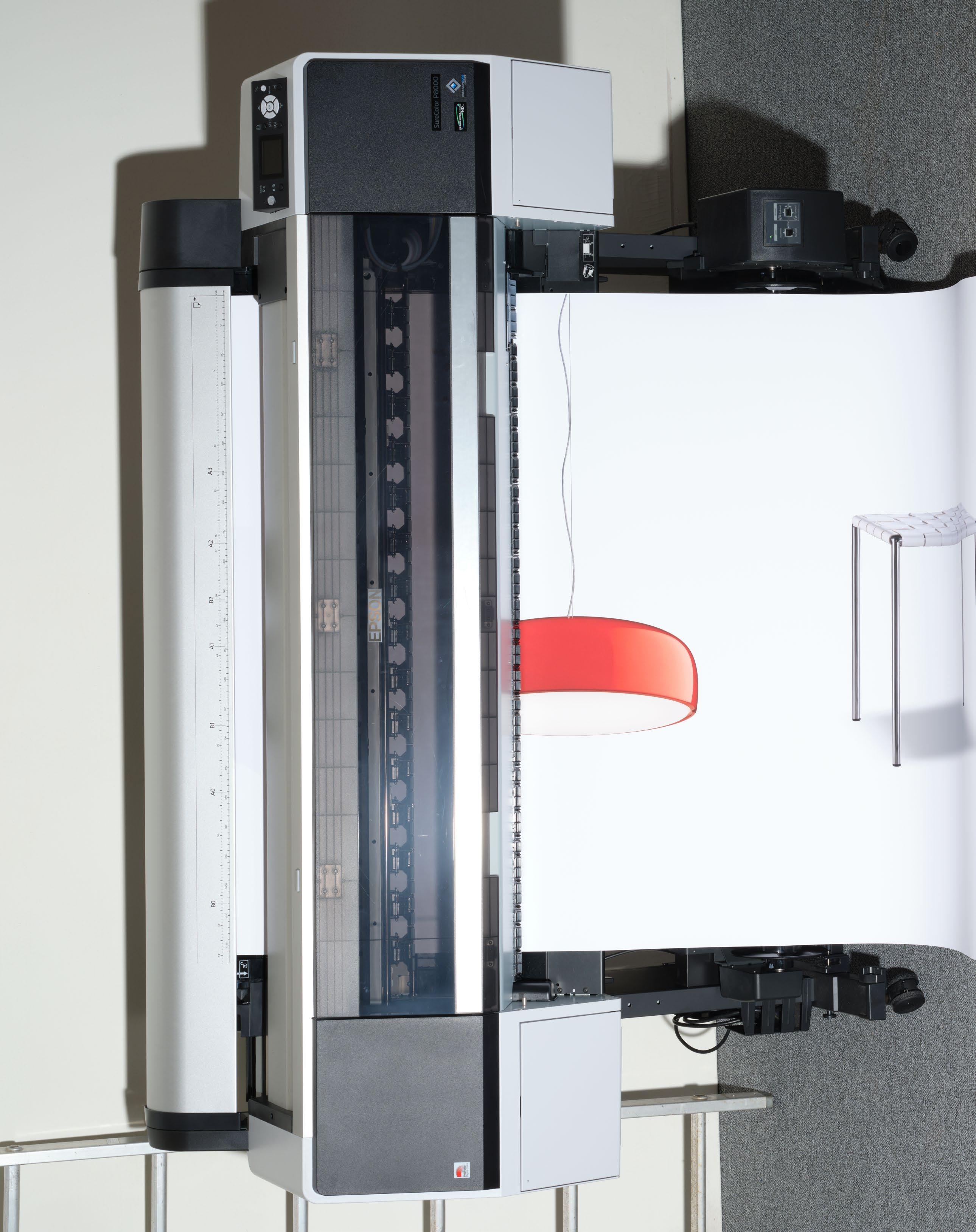

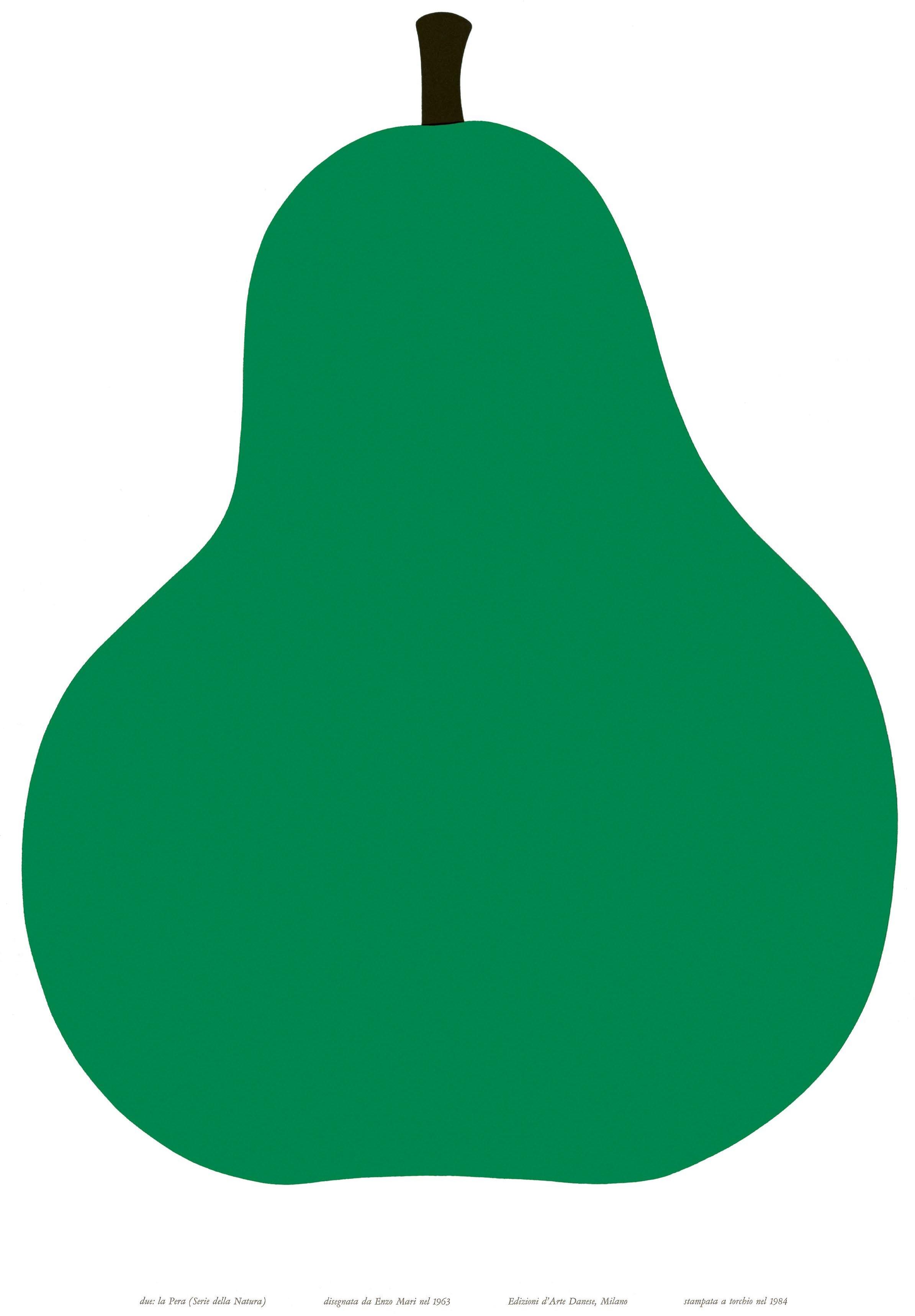

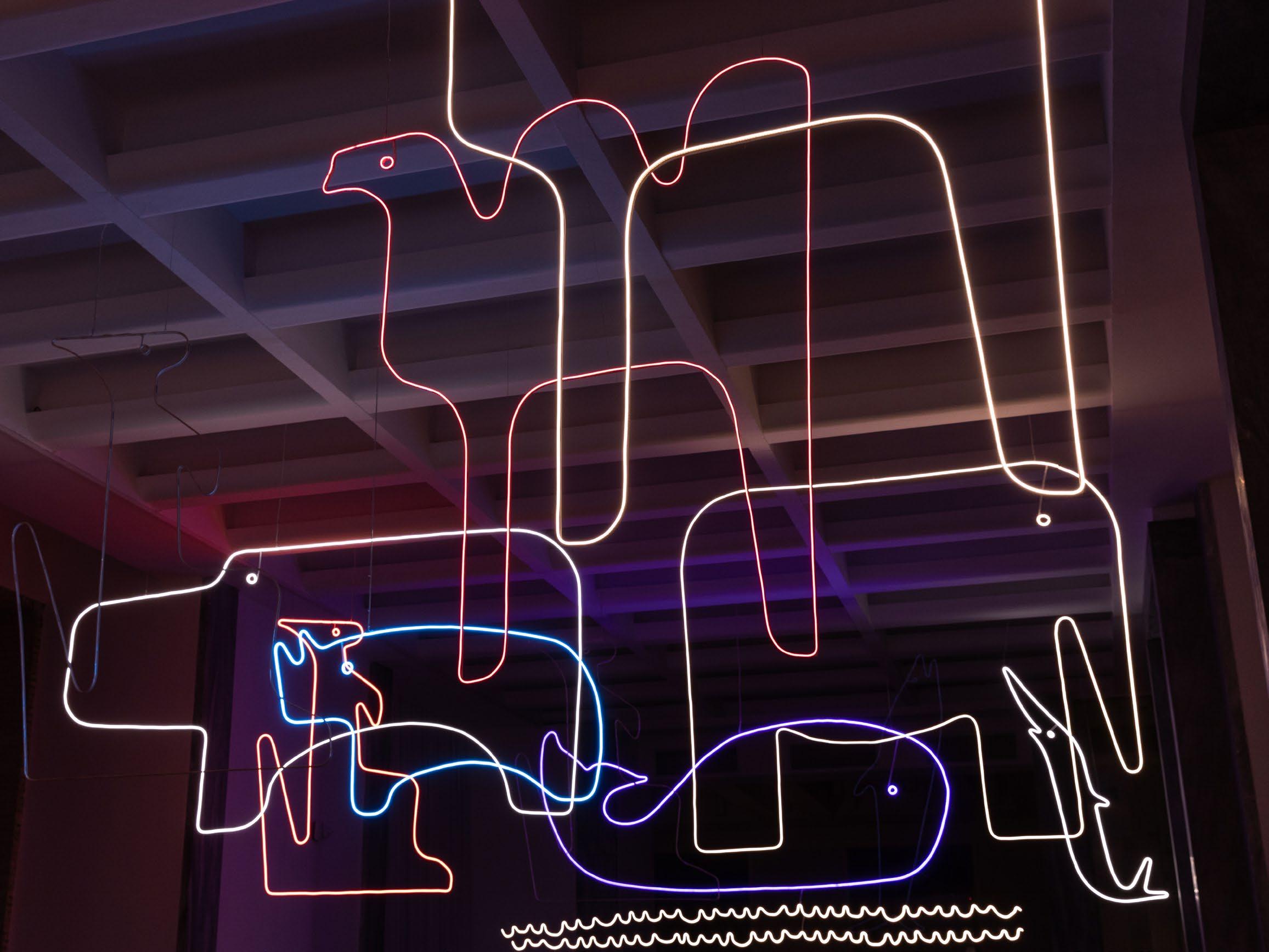

6 MINIMAL WITH MAXIMUM IMPACT A Practice For Everyday Life reflect on their principles Ayla Angelos 10 PEOPLE HAVING GOOD DESIGN A visit to David Mellor’s cutlery factory Samir Chadha 20 MATERIAL DIALOGUE: ATELIER OÏ The design trio reflect on their work with Louis Vuitton 22 PRINT JOB Iconic designs for the home Deyan Sudjic 32 A NEW KIND OF CONTEMPORARY Reflecting on Antonio Citterio’s work with Maxalto Deyan Sudjic 34 I SUGGEST YOU LOOK OUTSIDE THE WINDOW Discussing Enzo Mari with Hans Ulrich Obrist Deyan Sudjic 40 CONTINUE EXPLORING Photographer-makers on their approaches to craft

PORT REVIEW OF DESIGN 34 CONTENTS

THE

FASHION

174 (RE)CONSIDER THE OYSTER Nikki Shaner-Bradford 176 I WILL KEEP YOU WITH ME FOREVER, EVEN IF IT KILLS YOU Emmeline Clein 180 HOW NOT TO SKIN A RABBIT Fernanda Eberstadt COMMENTARY

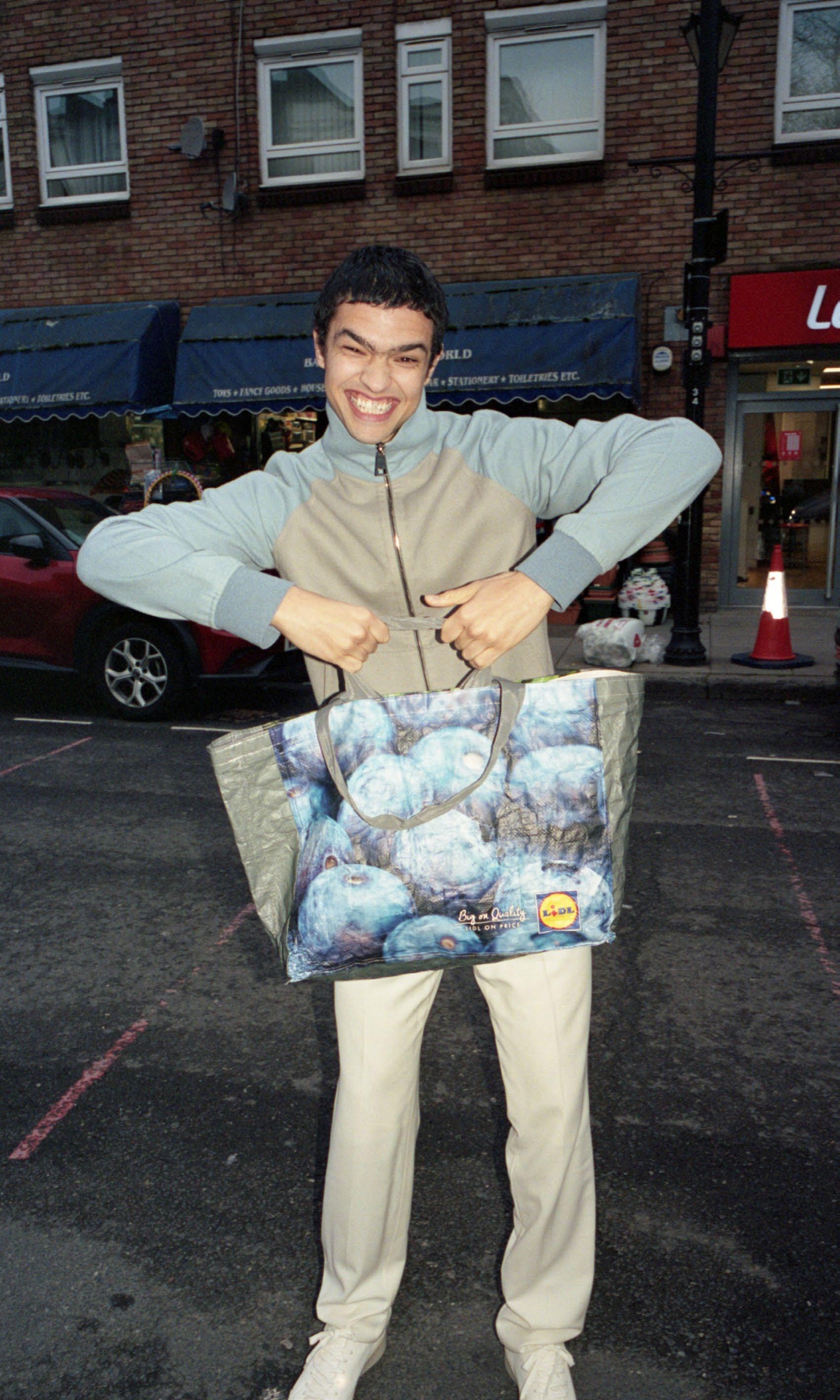

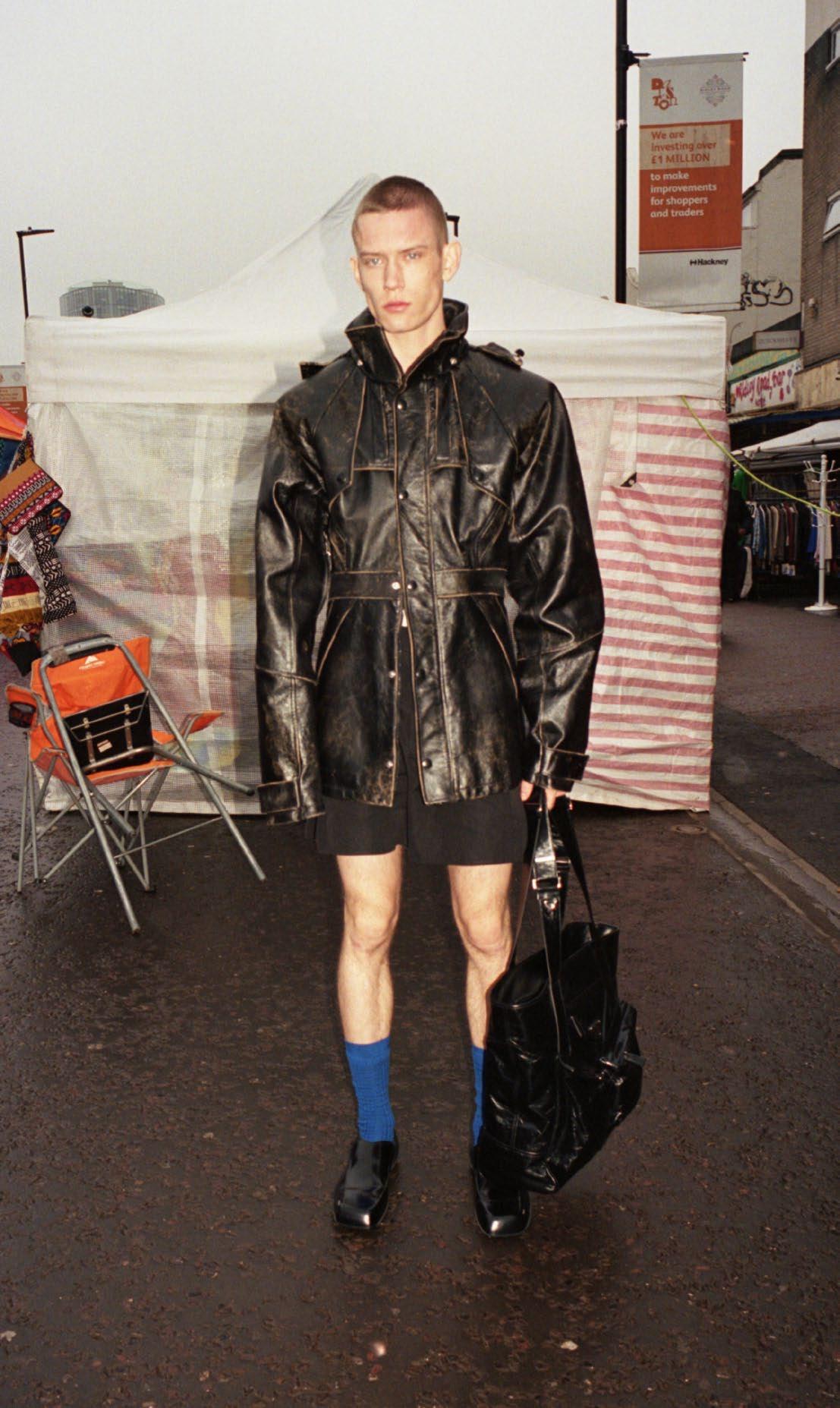

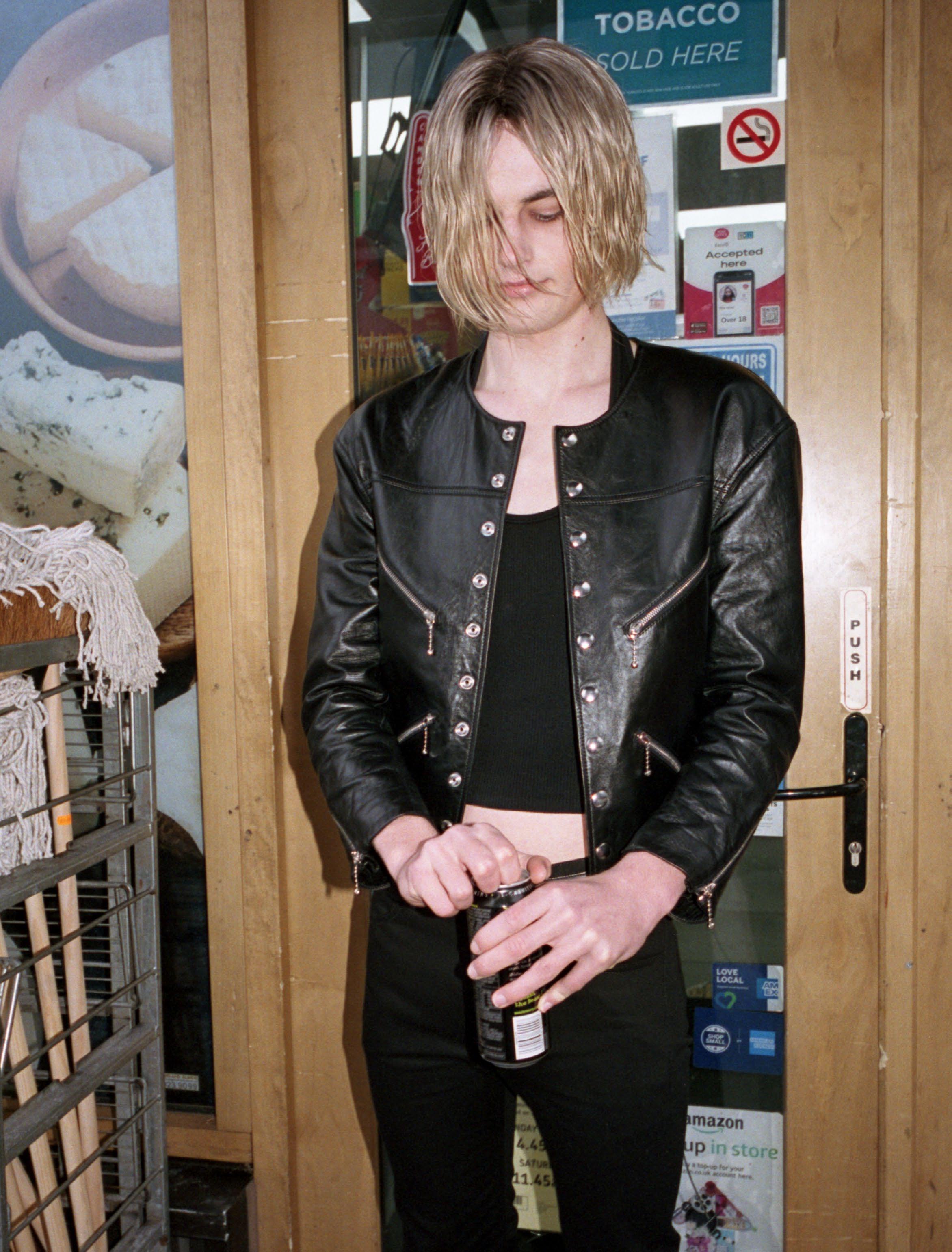

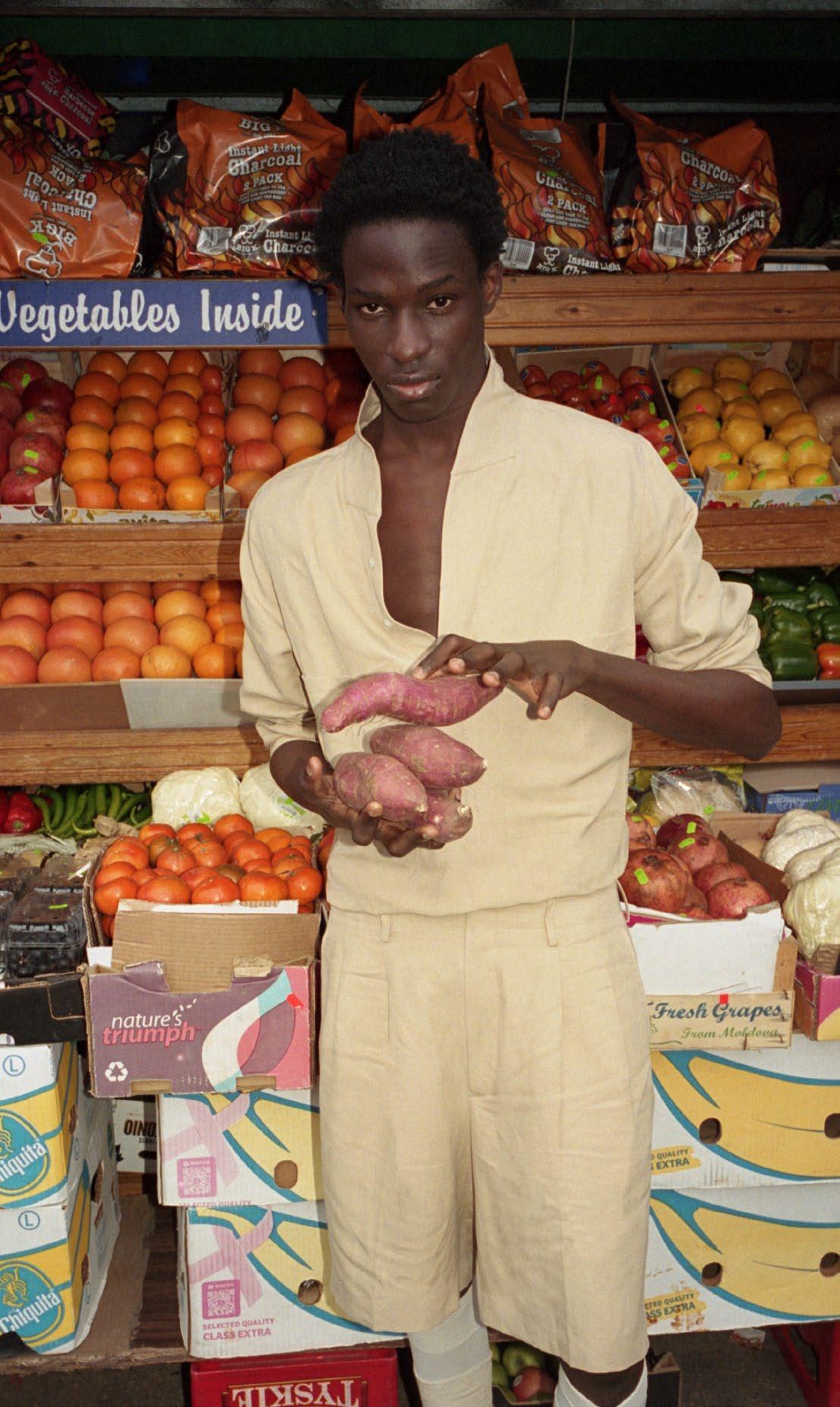

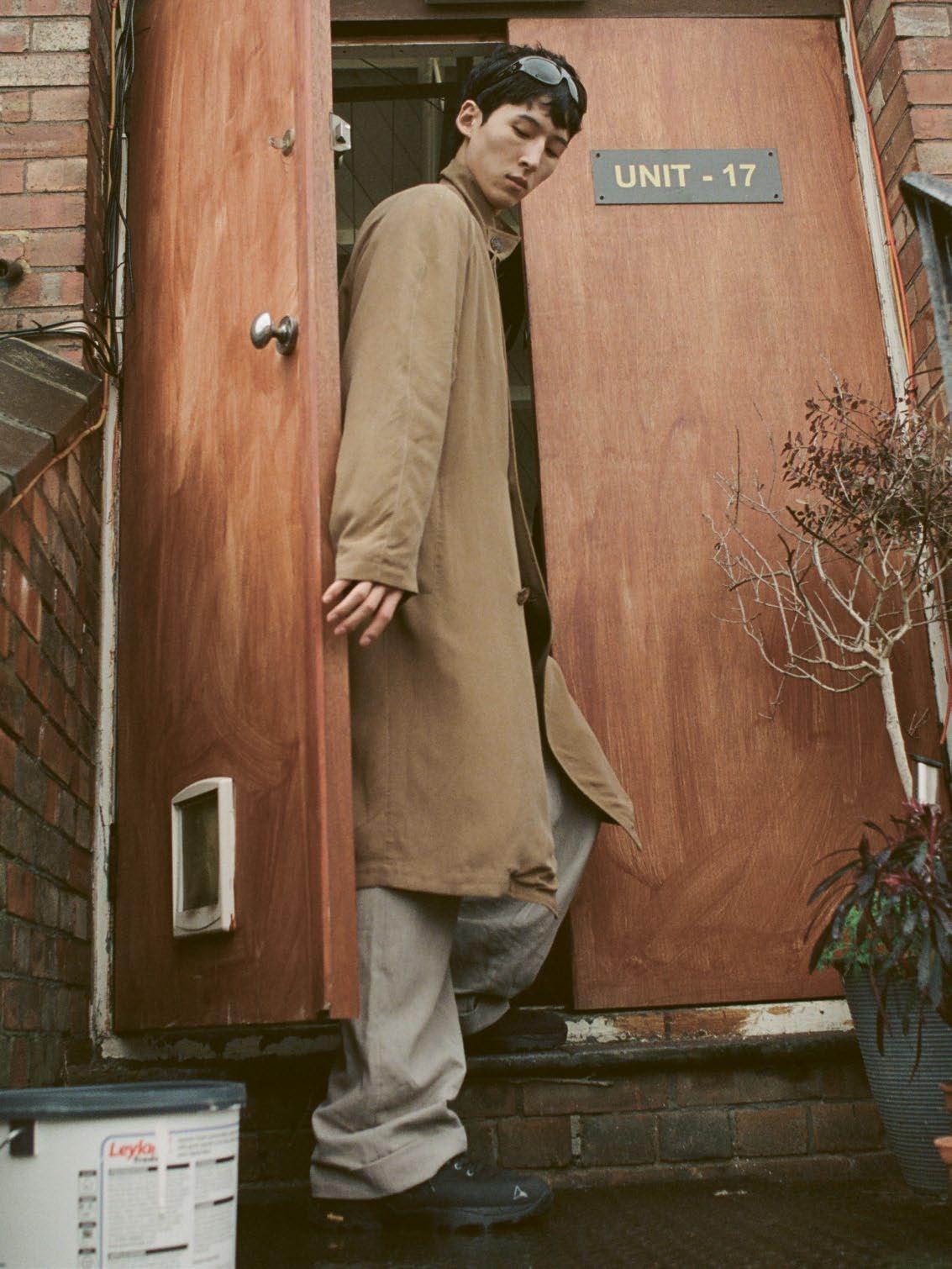

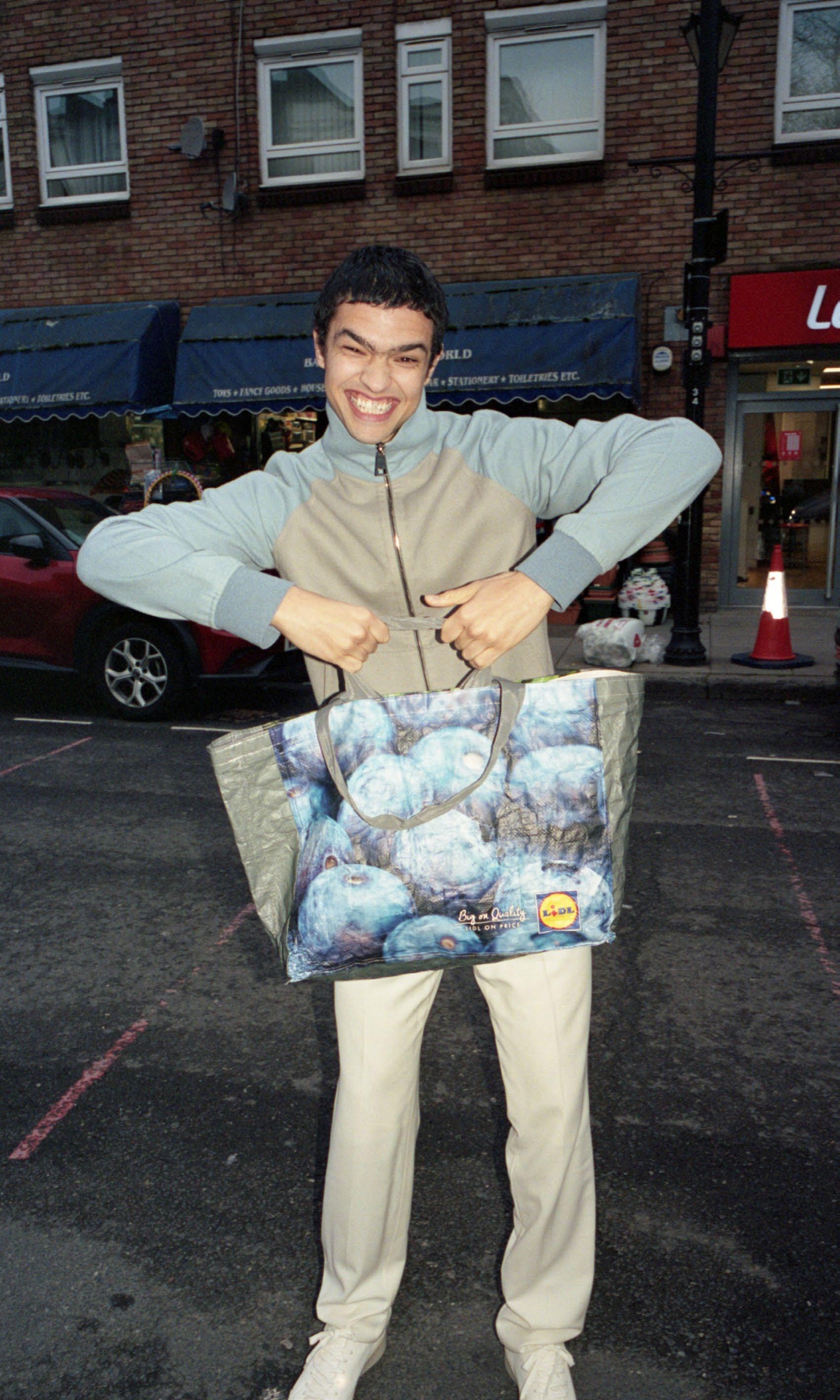

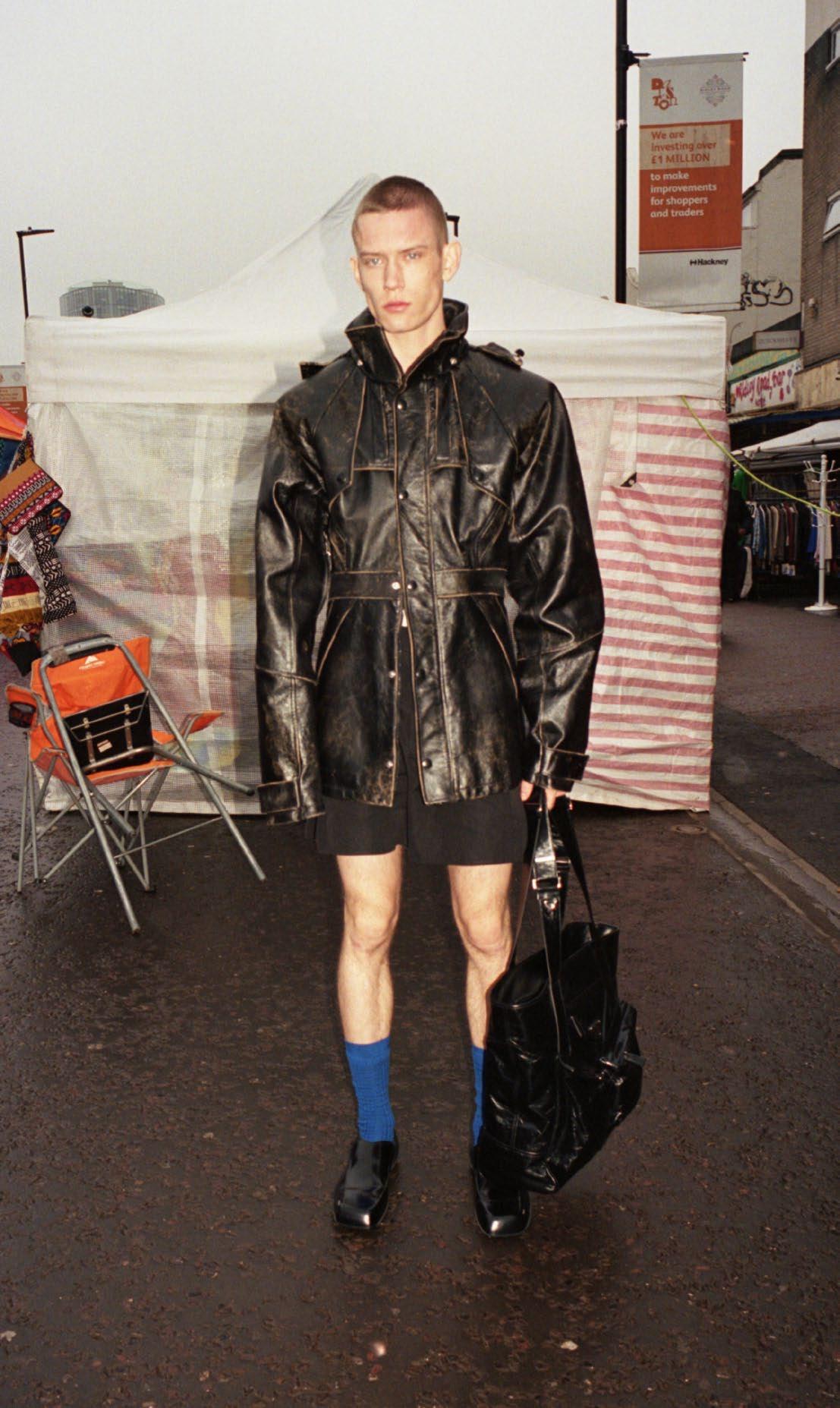

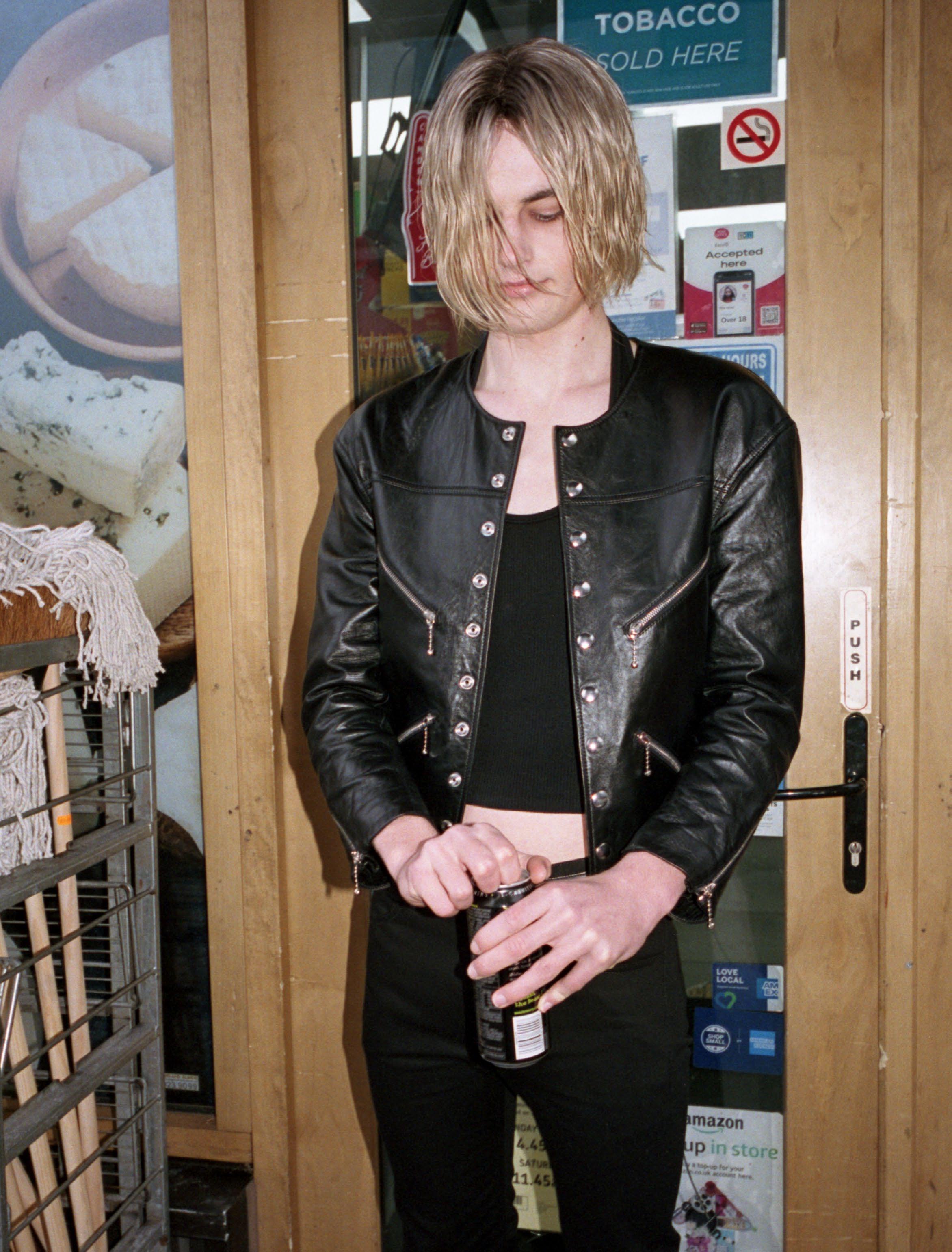

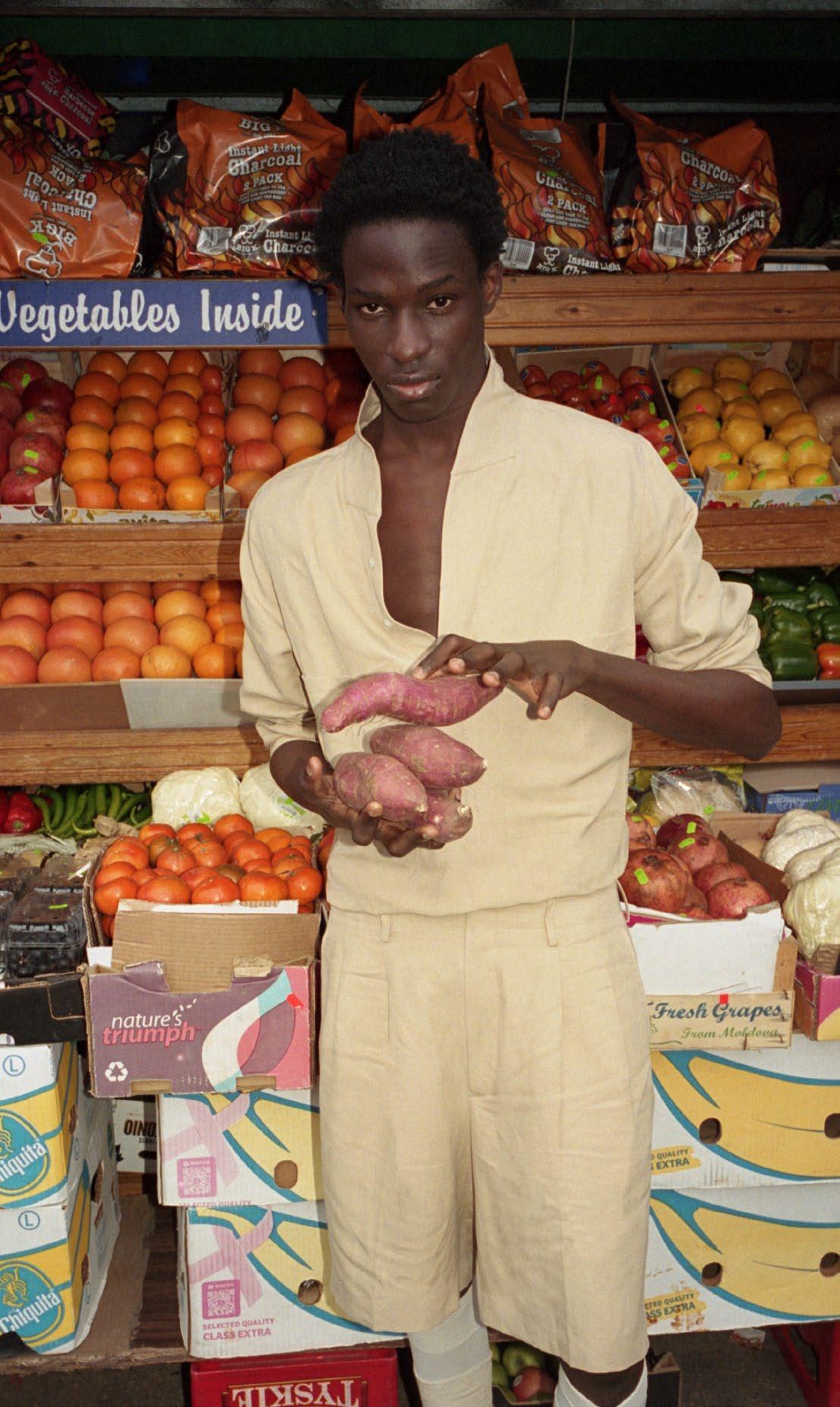

186 MARKET SHARE Photography Kuba Ryniewicz Styling Georgia Thompson 201 SALAD DAYS Photography Adrian Catalan Styling Julie Velut 217 SPHERE SPAWN Photography Sufo Moncloa 229 GOSSAMER Photography Louis de Rofgnac Styling Mitchell Belk 244 FRAME WORK Photography Crista Leonard Styling Georgia Thompson 260 CHECKED AND BALANCED Photography Nicolas Kern Styling Mitchell Belk 272 LAST MILE Photography Jelka von Langen & Roman Giebel Styling Naomi Miller 288 FALLING FAR FROM THE TREE Photography Angèle Châtenet Styling Julie Velut 35

IAN MCRAE is a NYC based stylist and consultant from Tallahassee, Florida. His work is influenced by all things whimsical and playful and the blurring of masculine and feminine in youth culture. He’s worked with brands and magazines including Another, Nike, Fantastic Man, and SSENSE.

KATIE GOH is a writer and editor based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Katie’s writing has appeared in publications such as the Guardian, Prospect, Dazed, i-D and VICE. She edits non-fiction at the literary magazine Extra Teeth. Katie’s debut memoir Foreign Fruit is forthcoming from Canongate and Tin House in 2025.

JENNA MAHALE is a writer, editor and researcher based in London. Her journalism appears in publications including The Atlantic, New York Magazine, i-D, and Kinfolk, and her fiction has been shortlisted for the Guardian / 4thWrite Prize. She is currently at work on her first book.

BRUCE GILDEN was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1946. He first went to Penn State University but he found his sociology courses too boring for his temperament and he quit college. Gilden briefly toyed with the idea of being an actor but in 1967 he decided to buy a camera and to become a photographer. In 2013 he received a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship.

38 CONTRIBUTORS

ISAAC RANGASWAMI is a writer based in London. He runs the Instagram page @cafs_not_cafes and the newsletter Wooden City, both of which celebrate everyday places with unusual staying power.

EMMELINE CLEIN is a writer. Her first book, Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger & Harm, is out now from Picador in the UK and Knopf in the US. Her chapbook Toxic was published by Choo Choo Press. Her essays, criticism, and reporting have been published in The Yale Review, The Paris Review, The New York Times Magazine, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and other outlets.

FERNANDA EBERSTADT is the author of five novels and two non-fiction books. Her most recent work, Bite Your Friends: Stories of the Body Militant, has just been published in the UK by Europa Editions.

TOM HIDDLESTON is a noted actor of stage and screen, recently appearing in productions of Betrayal and Coriolanus, and onscreen in The Essex Serpent, The Night Manager, High-Rise, Only Lovers Left Alive, War Horse, and many more. Since 2009, Tom has played Loki in numerous Marvel Studios films, and most recently in two series of the hit standalone television series, of which he was also a producer. He has served as a Global Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF UK since 2013.

39 TOM HIDDLESTON PHOTOGRAPH STEVE SCHOFIELD

THE PORTFOLIO

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARIUS W HANSEN

INSISTENTANDBEYONDCHOICE

.

AuthorandplaywrightSheilaHetid

ybhsAëolhCyB

i sc u s s esherlatestbook , rework i n g a d e c a ed o f .seiraid

DIARIES ARE of-limits, private musings of private minds. To read them would be wrong, insensitive, near illegal – so I’m told by Google. But what about when they’re typeset, bound, in a bookshop?

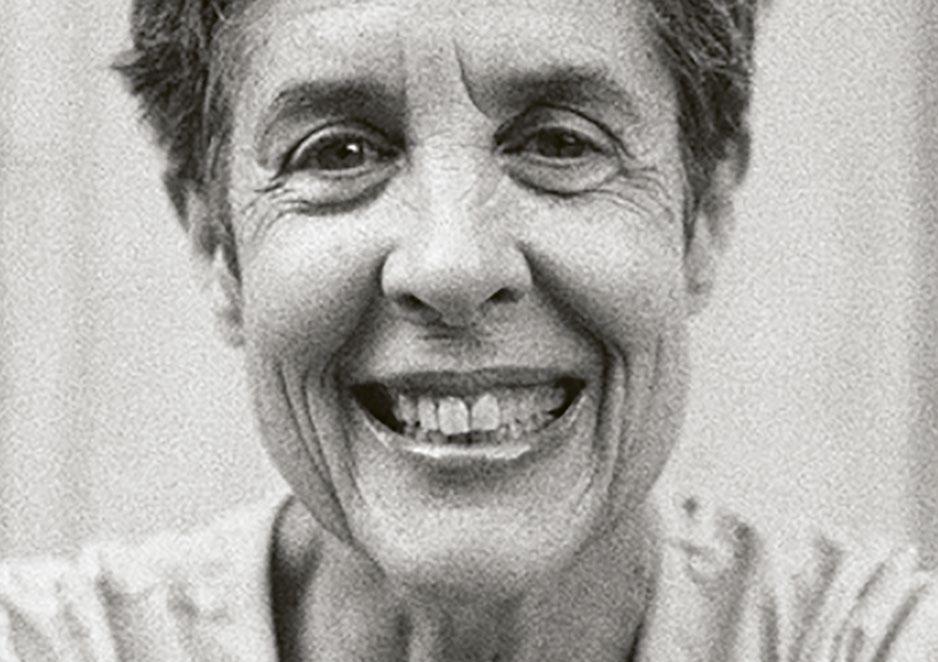

Sheila Heti began compiling a decade of her own diaries after writing her wildly original 2012 novel How Should a Person Be? She loaded half a million words typed between her mid-20s and mid-30s into an Excel spreadsheet, and ordered the sentences from A to Z. Of course, there was more to it than that – whittling down the wordcount, lending the lines rhythm – but that’s the gist. The result, Alphabetical Diaries, is a compendium of the author’s thoughts, feelings, wonderings. It’s about living. Being with the right and wrong men. Buying and wearing nice clothes. Having or not having children. Lipstick. Love and sex and desire and shame. Money and lack thereof. Reading and writing books. It’s curious, philosophical, funny, earnest.

I ask where the seed for the project came from, and Heti tells me, “Maybe it was that I wanted to see who I’d been all those years. Maybe it was a curiosity about which repetitions would come up or what it would do to the story of one’s life to alphabetise it.” But those were secondary concerns. “The primary concern was that I’d just finished a book and I wanted to stay on the computer and keep working.” Which, judging by the books she’s published –11 to date – isn’t something she struggles with.

And yet, when we speak in early January –Heti from her home in Toronto – she admits she only woke up 45 minutes ago. “Somebody was yelling in the street, and I thought, why is she waking me up at seven in the morning? And then it turned out it was 10,” she says, laughing – over the course of our conversation, we’ll both do a lot of this. She has her first cofee of the day in hand, is nestled on a comfy-looking armchair by a window letting in the not-so-early milky light, and is fresh-faced and ready to go.

So, what was it like, revisiting her past self on the page? Emotional? “I don’t think so, for one thing because the sentences are broken up – so I wasn’t looking at my life in a narrative way, going through scenes.” She ofers to show me, and together we zip through long lists of isolated sentences on her shared screen. To begin with, she didn’t edit for fear of ruining the experiment, then the experiment became a book. “I never changed the meaning, but I did cut 90 per cent of the words.” The lines that remain resemble scraps and fragments, individual pieces that, as you read, gradually form a semi-complete puzzle, loosely Heti-shaped.

I wonder whether she had any surprises about herself (nasty or nice). “I guess it makes you think about your life more archetypally,” she says, looking towards the window. “When you’re living your life narratively, you think, okay, there’s this one guy, and he’s diferent from the next guy, and then he’s diferent from the next guy, but when you alphabetise it, you realise, oh no, I’m just always thinking about… a guy.” We laugh. “I think we have this feeling, going through life, of things happening to us, but the repetition makes you appreciate the fact that actually you’re making things happen to you, over and over again, because your character enjoys or needs them.”

44

In her deeply personal and formally inventive novels, Heti writes beautifully and honestly about what she’s lived and thought about and felt. Motherhood is an exhilarating meditation on maternal ambivalence; Pure Colour considers art criticism, grief, God. But she doesn’t think of those books as confessional or particularly exposing: “By the time the experiences are in book form they feel separate from me as a person.” The diaries are a little more daunting – perhaps because, unlike in her novels, the character she’s putting across to readers is “more mysterious”. She worried, when they were excerpted in The New York Times, that they would come across as trivial or narcissistic. Then again, as she points out, “Everyone’s diary is solipsistic – it’s a place to be thinking about yourself.”

Heti’s process is intuitive: rather than thinking about why she’s writing, she just writes. “Everything can be worked out later,” she says. “But if you don’t go with your instincts, there’s going to be nothing to work with.” She doesn’t write to a schedule. “I feel bad when I’m not thinking about a project, so it gets done.” If there are gaps, she figures they need to happen; maybe a dream will spark something. She compares writing to a relationship, the way it slips and shifts, works itself out. “I’m not trying to make myself into a diferent kind of person in order to write books. I think the trick is to figure out what kind of person you are and then come up with a process that suits you.”

One early sentence reads: “All I ever wanted when I was younger was to be a writer, to be able to sit in one place and write things forever, and not feel like I had to do anything else.” She isn’t sure what prompted that ambition. “Sometimes you don’t know where these things come from.” She gives it thought. “They just come strongly, and they’re insistent and beyond choice.”

She’s also managed to fulfil her desire to write in one place. Besides small stints, she’s lived her whole life in Toronto, where she was born to Jewish-Hungarian immigrants on Christmas Day in 1976. Alphabetical Diaries is peppered with the tussle between her hometown – “Toronto felt to me yesterday like putting on soft pyjamas,” – and the life she could be living in New York, “full of parties and glamorous people, never feeling sad, alone, left out, apart”. Does she regret staying? “I’m happy in Toronto and staying here was the right decision for me for a million reasons,” she says, reeling of a list that includes afordability, healthcare, grants, the absence of noise, having friends and collaborators around. “If what I most wanted was to be a writer, it made sense to stay.”

It reminds me of another line in the book: “Everything has to be sacrificed for writing.” Heti clarifies: “I don’t think that’s everybody’s path, but I’ve always loved Kierkegaard, Simone Weil – the people who have sacrificed everything for writing.” She tries to choose interesting experiences, to expand her knowledge of what it feels like to live. To go into the emotional stuf with a sense of courage. To use her life as a testing ground and not take herself too seriously. Still, I wonder aloud if the prospect of sacrificing everything for one’s art could come across to some as bleak. Heti smiles. “I don’t think it’s bleak. I think it’s exciting, thrilling. A bit like being an adventurer on the high seas.”

45

THE HAMBURGER. An enduring staple of American fast food and a much-loved addition to menus across the globe. Not an item one would usually associate with the glistening world of jewellery, but for Singapore-based designer Nadine Ghosn, it has proven to be the ultimate muse to inspire her playful talismans, rendered in solid gold and colourful, vibrant combinations of gemstones.

Her bestselling jewel, the Veggie Burger, is a shiny stack of six rings – including a gem-dusted ‘gluten-free’ top bun and a burger patty – that puts a high-end twist on everyday food with diamonds, sapphires, tsavorites and rubies. “I loved the idea of taking an ordinary universal food that reminds us of our childhood: the famous burger. It was an unexpected fine piece of jewellery at the time because it was stackable and colourful. We all can relate, and it often puts a smile on our faces,” says Ghosn. “The stackable component – so people can customise their burger – was an arduous manufacturing practice, to make sure they fall in the right place once stacked.”

Ghosn, who founded her namesake brand in 2015, has long brought a light-heartedness to the fine jewellery space with collections inspired by diferent foods, like her edamame, sushi and croissant charms, as well as her YOUtensils line, that applies a golden touch to the humble fork, spoon and disposable straw. Today, she is one of a handful of jewellery-makers working up appetites with food-inspired designs that rif on the work of artists like Hayden Kays and Andy Warhol by translating commonplace objects into precious trinkets, while paying subtle homage to heritage jewellers like Carl Fabergé, whose exquisite, bejewelled eggs have delighted and intrigued since the 19th century.

Mish Tworkowski, the founder of the USbased label Mish Fine Jewelry, is a leading name in the niche market today. Playing with size and scale, Tworkowski dreams up tasty jewels like his Strawberry Flower collection, which brings precious expression to his favourite fruit, the strawberry. On earclips, bracelets and pendants, every detail of the strawberry, from its dainty seeds to its stalk, has been replicated in gold, lending each design a delightfully tactile and vibrant appeal.

Much like Tworkowski, Dolce & Gabbana has paid recent homage to the delicacy of berries with one of its most spectacular jewels to date. The Cherries set, unveiled as part of the Italian fashion giant’s Alta Gioielleria ofering, includes a high jewellery necklace and bracelet modelled with two ruby-encrusted cherries and yellow gold leaves. Enamelled by hand, the pieces recreate the atmosphere of an enchanted forest with a lustrous pavé of emeralds, rubellite tourmalines, peridots and rhodolite garnets set into twisted gold wire.

Meanwhile, for Rosh Mahtani, the founder of the London-based jewellery line Alighieri, creatures from the sea provide ample inspiration. Sculpted in bronze and plated in the brand’s signature 24-carat gold, her Gone Fishing earrings celebrate the wonders of the seaside with a shimmering gold fish suspended on a single hoop. Other delicacies include Alighieri’s Olive earrings (pictured),

which replicate the oval fruit in freshwater baroque pearls from London’s Hatton Garden, and the Flickers of the Sea necklace, a bronze fishbone pendant on Indian cotton cord.

And who could forget the candy-coloured creations of Rosie Fortescue? Founded in 2015, the London-based demi-fine jewellery brand specialises in failsafe jewels that can be styled from day to night, like her silver pendants and mix-and-match charm hoops that hug the lobe with gem-set treats, from sweets to zirconia-studded chillies.

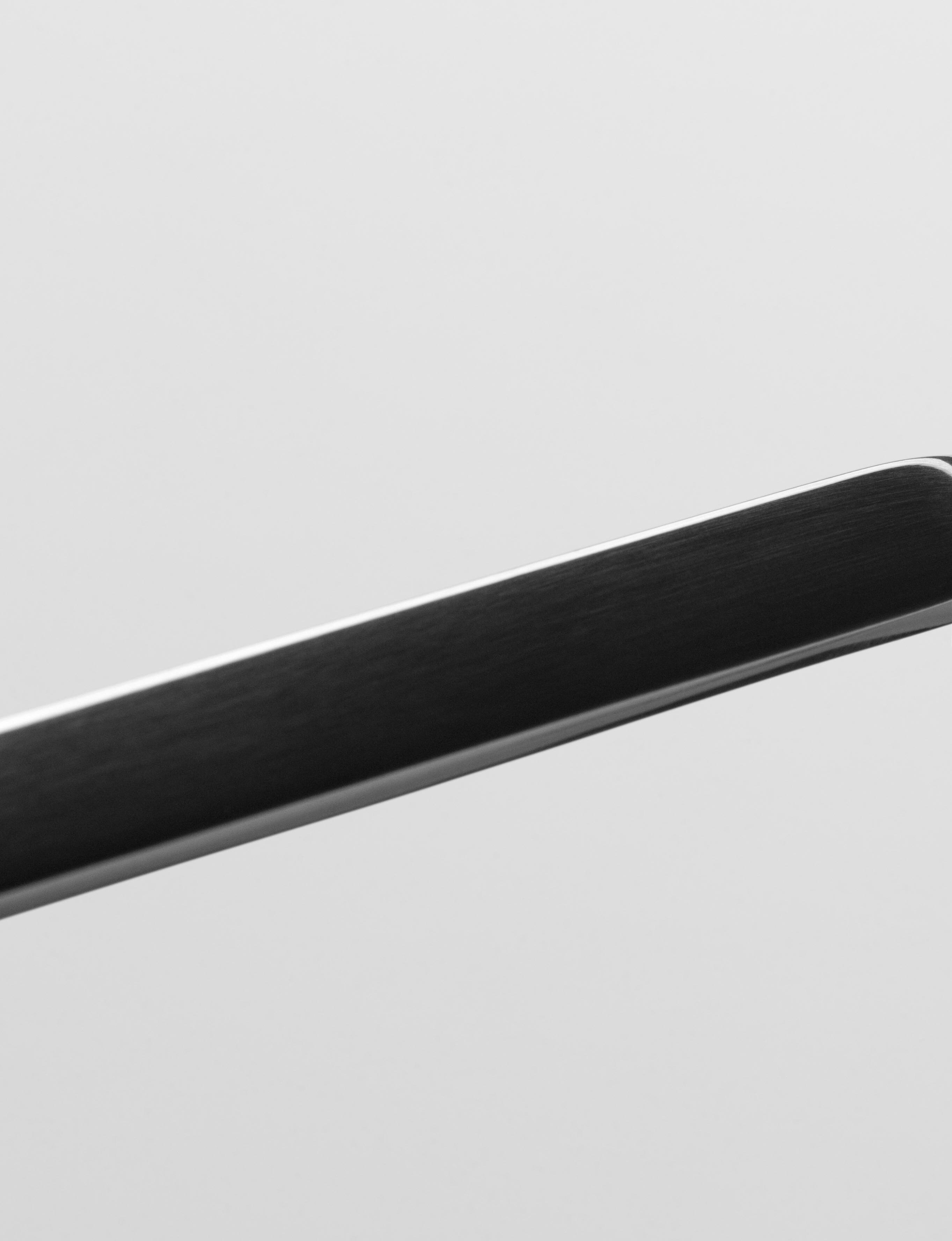

With its mood-boosting colour palette and talismanic qualities, the trend for food-inspired bijou speaks to a shelving of old styling rules and traditions. In 2024, jewellery should spark joy, and as our love of playful treasures shows no sign of abating, we can expect many more delectable trinkets to infiltrate our jewellery boxes in the coming years.

Jewellery courtesy Alighieri Jewellery

ByJoshuaHendren

EKNIRT T S . F oodinfluenced charms .

ELBATCELED

46

RETTUB . UB T T E R . B U TTER. BUTTER. BUT T E R. BUTTER. Clarifying the use of kitchens’ favourite fat. By Amelia

48

Tait

49

IT’S A SECRET THAT hasn’t been a secret for at least 20 years. At the turn of the millennium, the late chef Anthony Bourdain appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show and made her audience gasp, laugh, and shake their heads. “It is usually the first thing and the last thing in just about every pan,” he said of butter, before Winfrey pressed him to reveal exactly how much patrons ate when dining out. Bourdain said that at a classic French restaurant, you could easily eat “a stick plus” of the delicious golden dairy – that’s 113g, or around half a standard-sized block. “That’s why restaurant food tastes better than home food a lot of the time,” he smiled.

For too long, we have considered this revelation worrying and not wonderful. Butter has been demonised for decades, despite the fact that it contains bone-boosting vitamins and fatty acids which may help fight disease. The dairy in our dinner enriches, emulsifies, crisps and caramelises – without it, we would leave restaurants healthier perhaps, but also far, far

unhappier. Still, one thing has to be clarified before it can be celebrated. Two decades after Bourdain’s butter disclosure, how much dairy does the restaurant industry really use – and which dishes are the butteriest?

“I can’t see a kitchen that can live without butter,” says James Cochran, head chef of Islington-based modern bistro 12:51. The dish on the menu with the most butter is his aerated crab hollandaise, which is whipped inside a foam gun. “You basically get a lot of butter but served in a very light format,” he says. How much butter, exactly? About 25g per portion. A little pat of butter that you might grab at a hotel breakfast bufet is usually 8g – so that’s only about three of those.

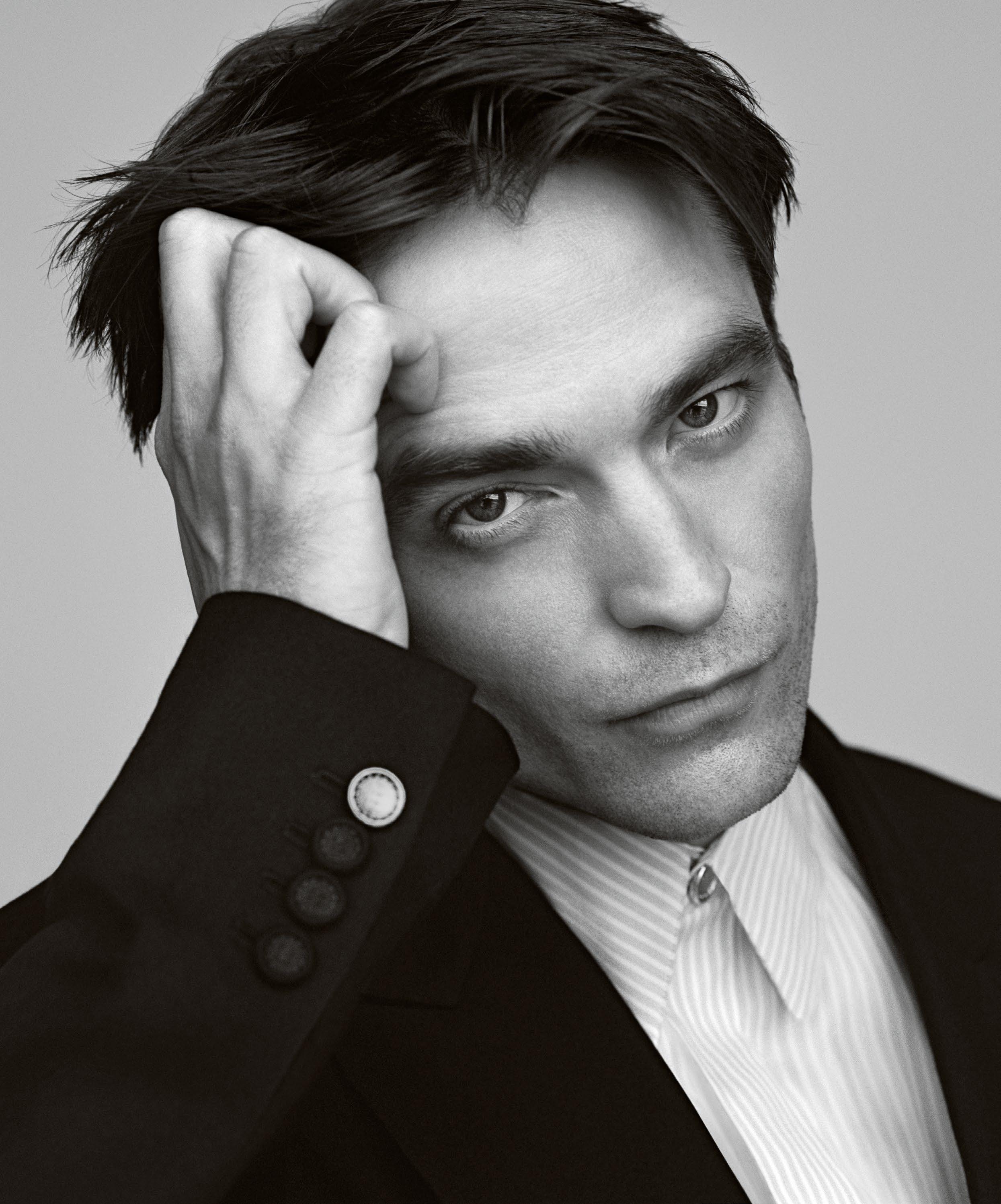

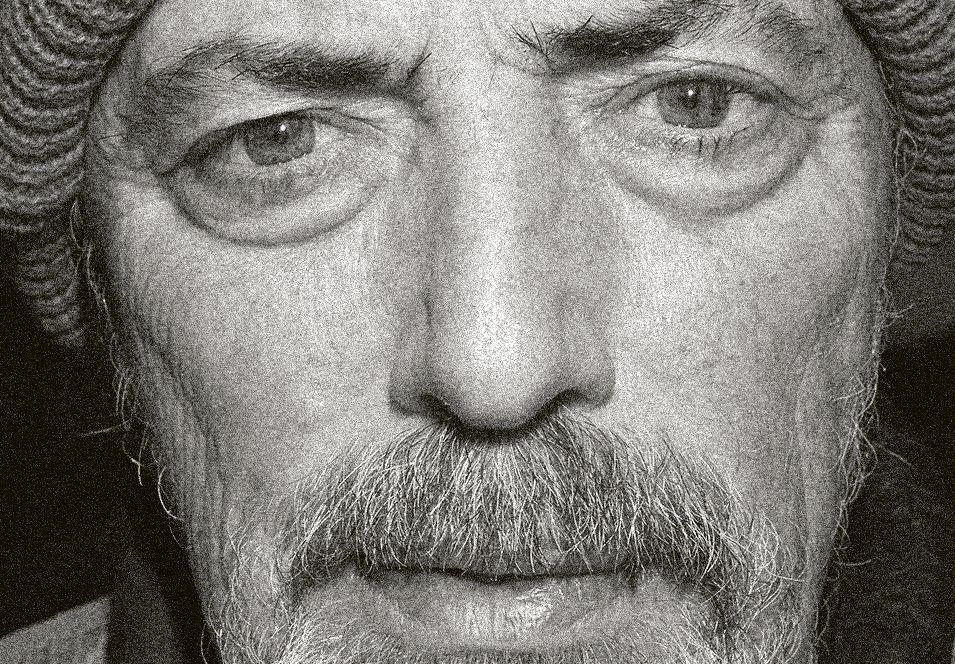

In total, 12:51 goes through around 25kg of butter a week (meaning that if they used the same 200g blocks that you have in your fridge at home, they’d need 125 of them). When cooking meat, Cochran likes to add rendered fat from the pork or beef to the butter to make a rich, enhanced beurre noisette.

“I think it’s just one of the most versatile products that you can use,” Cochran says. “It’s such a staple product that every human being has been brought up with from an early age.” Sameer Taneja, executive chef at the Michelin-starred Benares in Mayfair, has fond childhood memories of butter that allow him to celebrate, not vilify, the ingredient.

“Butter or ghee is very indigenous to the community, the culture we come from,” says Taneja, who was born in Delhi. “We also take it for therapeutic or medicinal use rather than calories.” When he was a boy, Taneja’s mother would rub ghee on his cuts, burns and bruises. Scientists have found that ghee – which is clarified – has antibacterial and antioxidant properties that can help blisters and inflammation and promote speedy healing. “Before, I didn’t understand that this is not a medicine, it didn’t come from a pharmacist,” Taneja says, “but it worked.”

Benares goes through around 10-15kg of butter a week, a fact Taneja is sweetly nervous

50

about disclosing: “I’m actually telling the world how many calories I use!” One of the butteriest dishes on the menu – besides, of course, the butter chicken, which uses around 20-30g –is the scallop curry, which is emulsified in butter. Usually, there’s about 10-15g of butter in a portion of the dish (which, again, could easily be devoured in two rounds of toast from a breakfast bufet).

Taneja is efusive about the benefits of ghee: “It’s full of minerals, it is rich in potassium.” Butter contains vitamin B12, which can prevent anaemia, as well as vitamin A, which is beneficial for our eye health. It is a good source of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), a fat which has been found to reduce the growth of cancer.

Taneja also notes that many Hindus use ghee in lamps lit for prayers, which he says “signifies the purity of the product”. And of course, there’s no point pretending it doesn’t taste good. “It makes the dish not only delicious, but it takes it to a diferent tangent. The fat is the one which brings all the tastebuds alive.”

Naturally, butter usage does vary from restaurant to restaurant and cuisine to cuisine. MasterChef finalist Matthew Ryle, head chef at Marylebone-based Maison François, says he goes through about 60kg a week. Meanwhile, Masha Rener, head chef at the Soho-based Italian deli Lina Stores, says that most of her dishes use extra virgin olive oil, which is more traditional in Italian cooking. Still, all of the six Lina Stores locations across London use a combined 400kg a week for their cakes, bakes and pastries.

“Butter helps create a crisp brown crust when searing a steak, ensures a rich buttery crumb in our cakes and we add it to our maritozzi [flufy brioche buns] to enrich the dough,” Rener says. Indeed, the ingredient has endless uses. “You also need butter to toast the rice in risotto, which is believed to have originated in Lombardy in the north of Italy, or for the traditional béchamel sauce; which, although not strictly Italian, is a key ingredient in our homemade lasagne.” Truly,

then, there is nothing better than butter – nature’s gold. Taneja compares a chef working without butter to a patisserie forgoing sugar. TV chef Julia Child famously adored butter, using 340kg over the course of her 1990s show, Baking with Julia. Bourdain himself called butter “everything” (emphasis his) going as far as to say that it was an invaluable ingredient “in almost every restaurant worth patronising”.

“All the nice stuf is the naughty stuf, basically,” summarises Cochran, “nine times out of 10 it’s going to be butter or some kind of fat put in there,” that is making a dish delicious. The chefs in this piece stress that they understand that moderation is important, as is good old-fashioned exercise – but it’s also worth remembering that a buttery night at a French restaurant has never killed anyone. “As a society we are pretty health conscious, but once in a while we’re allowed to indulge,” Cochran says. “And why not just eat loads of butter?”

51

By Isaac Rangaswami

A visit to City stalwart Sweetings.

CLATTERING FISH KNIVES AND SCRAPING STOOL LEGS.

I’D HEARD LOTS about Sweetings over the years, but it wasn’t until I called to make a reservation that I learned it was walk-in only. So I decided to get there early, to guarantee myself a seat and feel this Victorian seafood restaurant’s atmosphere grow.

I arrived at a wildly corniced four-storey building, paint peeling beautifully from the signage at its base. Sweetings has occupied this patch of the Square Mile since 1889, back when the trafc around here was horse drawn and “eating out” meant at fish and oyster bars like this.

I pushed through the restaurant’s ancient doors; it was 11.29am and I was the first customer of the day. As I descended a few steps, the floor-to-ceiling windows rose up around me, before the silent dining room swallowed me whole. I drifted towards its edges, where I was shown to a cobalt blue cushion on four wooden legs.

Then came the suits. All around me new arrivals in gilets and pale blue collars took their stools, sitting like me with their backs to the room. Except one guy, who greeted a waiter by name and knowingly ducked underneath the counter, before swivelling round and grabbing a stool on the window side, so that he and his friend could sit face to face. Apparently, Sweetings’ waiting staf used to occupy these same enclosures, trapped like the bartender in Hopper’s ‘Nighthawks’.

The bill of fare here is similarly eccentric because it is old. There’s no turtle soup anymore, but you can still enjoy Welsh rarebit, potted shrimps and the skate wing in black butter Toulouse-Lautrec wrote to his mother about. Then there’s the place’s signature drink: a perspiring silver tankard of black velvet (pictured), a mixture of Guinness and champagne.

After my own prawns, chips, samphire and skate wing, someone crept up behind me with a perfect bowl of steamed pudding and custard. Without turning around, I could sense the room was now entirely full. All those bankers, insurers and consultants were perched on the same wraparound counter, yet somehow ensconced in their distinct little groups. Silence had been exchanged for the rumble of voices, supplemented by the odd laugh, clattering fish knife and scraping stool leg.

52

53

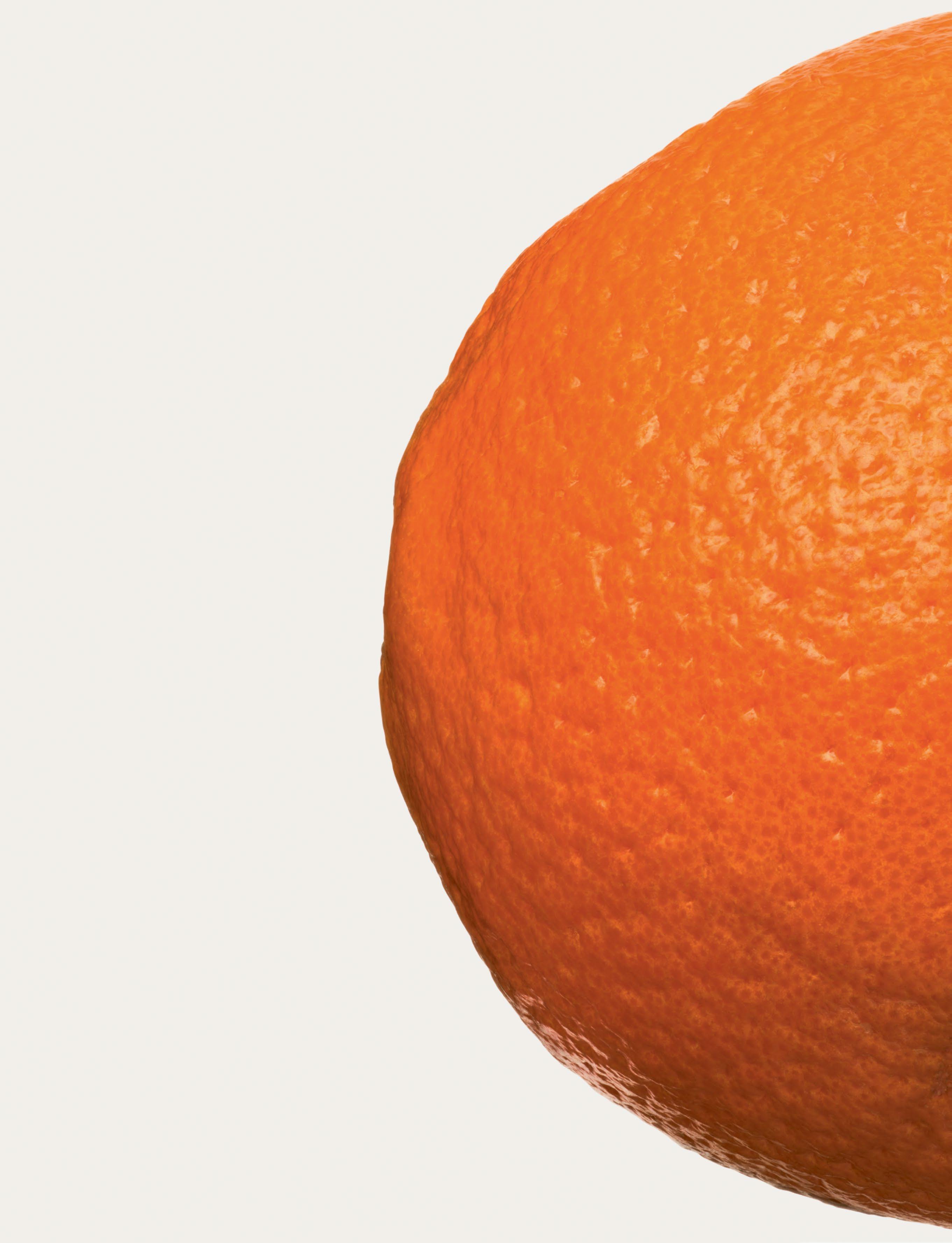

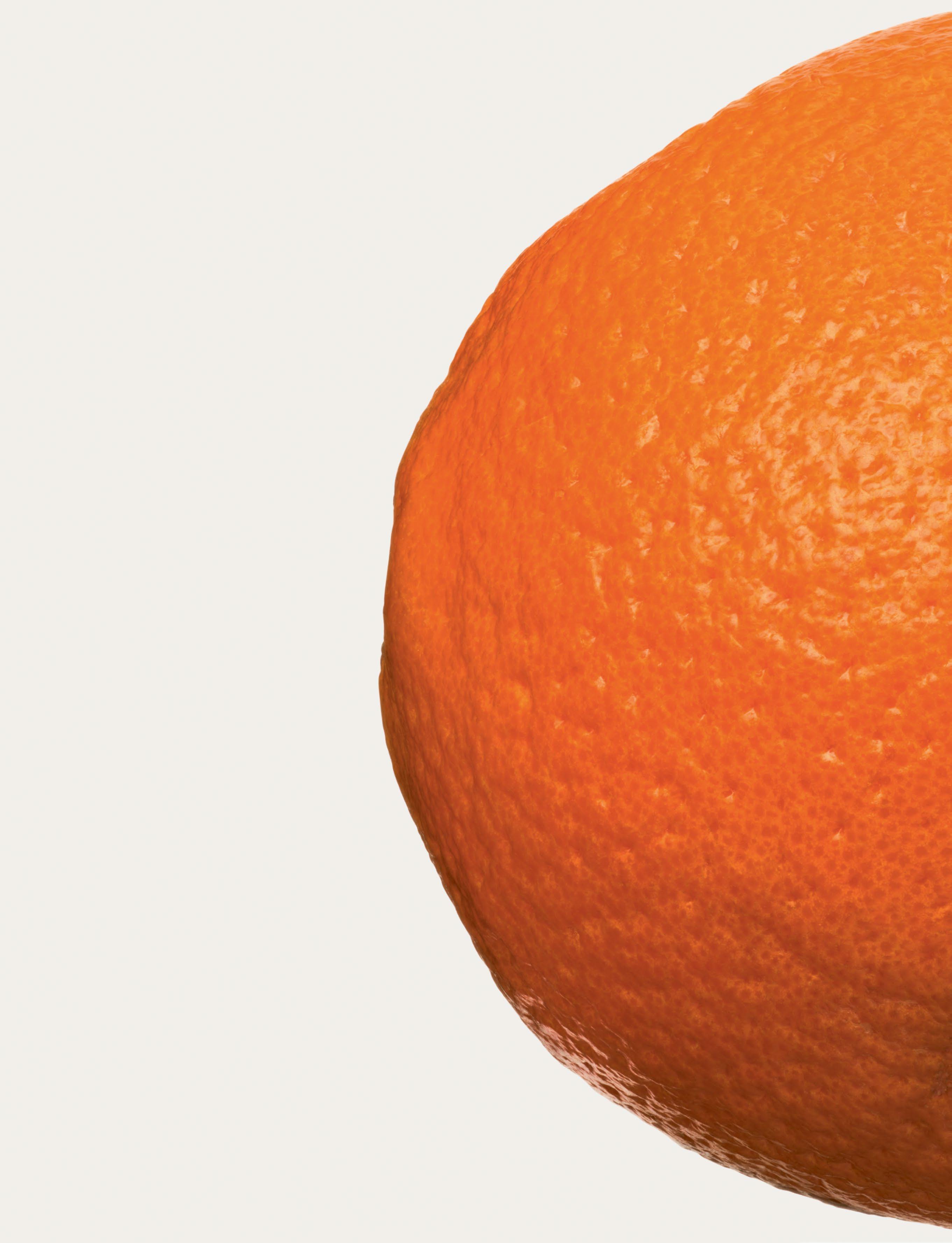

PA A R T . A v i s i t t o t h e fi r s t o f C a l i f o r n i ’as o r ang e trees. ByKatieGoh

TIURFEHTLLUP

54

IN 1873, THREE CITRUS SEEDLINGS arrived in Riverside, California. They had travelled far. Originating in Sao Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, they were carried northward at the request of the US Department of Agriculture. In the US capital, the saplings were re-christened the Washington Navel orange and, now American, they headed west to Eliza Tibbets’ garden in the city of Riverside, 50 miles east of Los Angeles. Planted in Californian soil, one sapling was trampled by a cow, but the other two grew into fruit-bearing trees, nurtured by the sun and Eliza’s dirty dishwater. The sweet, seedless fruit was so popular that Eliza cut buds from her trees to be grafted to other citrus rootstock. By 1910, over a million Washington Navel orange trees had sprung up in Riverside, each tracing its lineage back to one of Eliza’s two parent trees.

One of these orange trees still grows in Riverside. In the armpit of Magnolia and Arlington Avenues, the 150-year-old tree stands behind a screen cage to protect it from disease, insects and greedy hands. I found myself standing before it in January, California’s peak orange season, and so ripe fruit hung from its branches like golden ornaments. I circled it slowly, taking in its peeling, grey trunk and glossy evergreen leaves. Like Eve’s apple and Persephone’s pomegranate, California’s oranges are as much myth as they are fruit. They tell a story of California as a paradise of empty land waiting to be worked into groves of ripe fruit by a new generation of Anglo-Americans. But they also tell other stories: of Indigenous genocide, of immigrant workers, of land seized, of orange barons, of capitalism, of manifest destiny. Oranges created California. Once you start to pull the fruit apart, you pull apart a nation’s self-mythology.

I was in town to visit the University of California Riverside’s Citrus Variety Collection, one of the most extensive citrus collections in the world. I had been emailing its curator, Dr Tracy Kahn, for a few months and she had agreed to show me around the collection. I took an early morning train from LA to Riverside, rattling along hills and freeways into the rising sun. In Riverside’s small station, I waited for Tracy beside an abandoned plastic bag that had spilled its insides – tiny easy peel oranges – across the sidewalk. It seemed I was in the right place.

Tracy had picked me up in her car and as we drove, she asked me to explain why I was in Riverside again. I told her I was writing a book about oranges and my research had led me to the Citrus Variety Collection. She seemed amused that a writer – and one who was adamantly not a science writer – had travelled all the way from Scotland to Southern California to visit the collection. Even though I had only asked to see the collection’s fruit, Tracy decided that I should get the full tour of Riverside’s citrus history for my bother. So, to Eliza’s tree we had driven.

“Look down there,” Tracy pointed to the tree’s base. Rather than a single trunk, multiple thick branches curved from the tree into the earth. Tracy explained that this is called inarching. In 1918, the tree became ill, sufering from a root-rotting fungal disease. Inarching – a process in which rootstocks from other citrus trees are grafted to the original tree to create a new root system – was delivered by three scientists, so that no single man could be blamed

if the operation failed and Riverside’s beloved tree died. Lemon and orange seedlings were inarched successfully by the three scientists, with several more grafted in 1951. The citrus genus is cultivated through grafting, whereby rootstock and budwood from diferent fruit trees are brought together to create one stronger tree. Grafting surpasses reproducing citrus from seed – a laborious process which can take seven years to bear fruit – and it gives the genus its versatility and its endless fruit-bearing possibilities. A single tree can host diferent varieties – blood orange can be grafted to pomelo to lemon; pink, green and orange fruit can thrive together.

The Citrus Variety Collection is fenced in from the freeway in the south-east of Riverside. It encompasses 22 acres of land and over 1,000 varieties of citrus. Trees – tall and short, heavy and thin – ran into the distance in perfect lines, in every direction. Oranges grew in their tens of thousands. I had never seen so much citrus.

We moved towards the trees. Tracy carried a heavy blue binder of papers with her, flipping through its pages to find her map of citrus. When she located the numbered citrus variety she wanted to show me, she set of, moving fast through the rows of trees with me stumbling after her. We stopped at a Washington Navel, which began life as a bud on Eliza Tibbets’ parent tree. Tracy pulled a fruit from its branches and quartered it with a pocket knife. She handed me a segment and I bit into the fruit, which turned to sweet juice and stringy flesh in my mouth. It would have tasted good anywhere, but pulled fresh from its tree, under the Californian sun, its taste was pure pleasure. Tracy handed me another quarter, and when we were finished, we discarded the rind at the base of the tree. I shook droplets of juice from my fingers as Tracy strode on to the next tree. I hurried behind her.

Tracy was keen for me to sample as much as I could stomach. I bit into an acidless Vaniglia Sanguigno that tasted like candy and then nibbled at a Boukhobza that made my lips and eyes sting. The juice from a Moro, a Sicilian blood orange, ran down my hands and a sticky residue gathered beneath my jewellery. “This is a popular one.” Tracy pulled apart two citrus halves to reveal splotchy red flesh in a heart-shaped rind. “It’s called a Valentine.” I ate yuzu from the Philippines and pomelo from Tahiti and soon my lips were numb. “You’ll be glowing in the dark later,” she said with a satisfied smile.

As we explored, Tracy told me about its history, going back to its life as the Citrus Experiment Station on the slopes of Riverside’s Mount Rubidoux in 1907. Eliza’s navel oranges had sparked a booming orange industry, which called for more experimentation into fruit cultivation, as well as citrus diversity and genetics. The collection expanded rapidly in the 20th century, and the site is now as much a conservation project as a laboratory. Close to the grove, an enormous translucent structure is being built. Tracy explained that it’s called a Citrus Under Protective Screen (or CUPS), and it will function like a bigger version of what guards Eliza’s navel tree in downtown Riverside. One of each variety in the collection will be stored inside the living archive, protected from disease-carrying pests which threaten not only this historic grove, but the US’s citrus industry at large.

Tracy sliced into a thin Australian finger lime and squeezed until tiny lime-coloured juice vesicles spilled out. “Citrus caviar,” she called it. The collection’s researchers had been using Australian finger limes to crossbreed with other citrus, hoping to bolster more disease-prone species. I nibbled at the end of the strange fruit and its tiny balls popped between my incisors. We tossed away the peel.

Before I left Riverside, Tracy drove me out to the California Citrus State Historic Park, which includes 200 acres of citrus groves, growing navel and Valencia oranges. The Santa Ana winds had discarded palm leaves across the deserted parking lot. Tracy left me to wander round the visitor’s centre, which outlines California’s small but significant part in citrus’ global story.

I had been researching the orange for two years, but that was all theory, history and concept. I followed the trail of museum placards that told me how the orange is the hybrid ofspring of the pomelo and mandarin; how it was originated on the Tibetan Plateau, and made its way across Asia; how it travelled the Silk Roads to arrive in Europe, where it gave its name to a colour; how it was cultivated in Versailles’ orangeries for the king; how it was carried in Christopher Columbus’s ships to the new world, taken to California by Spanish missionaries searching for El Dorado. The state had two foundational gold rushes: the discovery of golden nuggets in 1848 and the planting of Washington Navel orange trees three decades later.

This long history led me to Riverside. I was surprised by how moved I was to be so close to the fruit, to be in the home of the orange in the US. It is one thing to read a paper on citrus taxonomy and another to pull an orange from its tree, slice into its flesh and place a segment between my teeth. Each bite felt like encountering that history with my body, making it familiar.

Before we got back into the car, Tracy pointed out a line of tall palm trees that careened overhead, swaying violently in the breeze. They receded into the distance, in exact increments. “That’s how workers knew where they were.” In the thicket of the orange grove, the palms were a map of the land along the horizon. These two plants – the palm and the orange – have become synonymous with southern California, but they are foreign imports that have cultivated the state’s mythology as a tropical paradise at the end of the wild west. Oranges built an empire of industry, but it waned in the 20th century as groves were razed to make way for highways and amusement parks. Now, citrus farming has moved to northern California, and the southern region finds itself memorialising its formative industry. In Riverside, historical re-enactments of groves and living archives keep the memory alive. But I keep returning to Eliza’s tree. It stands alone in the city, a ruin of California’s citrus past, behind a screen and between two congested streets. Eliza’s last tree will never be allowed to die because it embodies Riverside’s 150-year-old history in its boughs. It is a sickly tree kept alive by grafted roots. And yet, every January, it still grows oranges. The people who maintain the tree pick some of its fruit to take home, but mostly it piles up behind its safety screen. Each orange ripens until it falls from its branch, hits the earth, and begins to rot.

57

58

PETITES MAINS.

ReinterpretingDior’sclassic

cannage motif

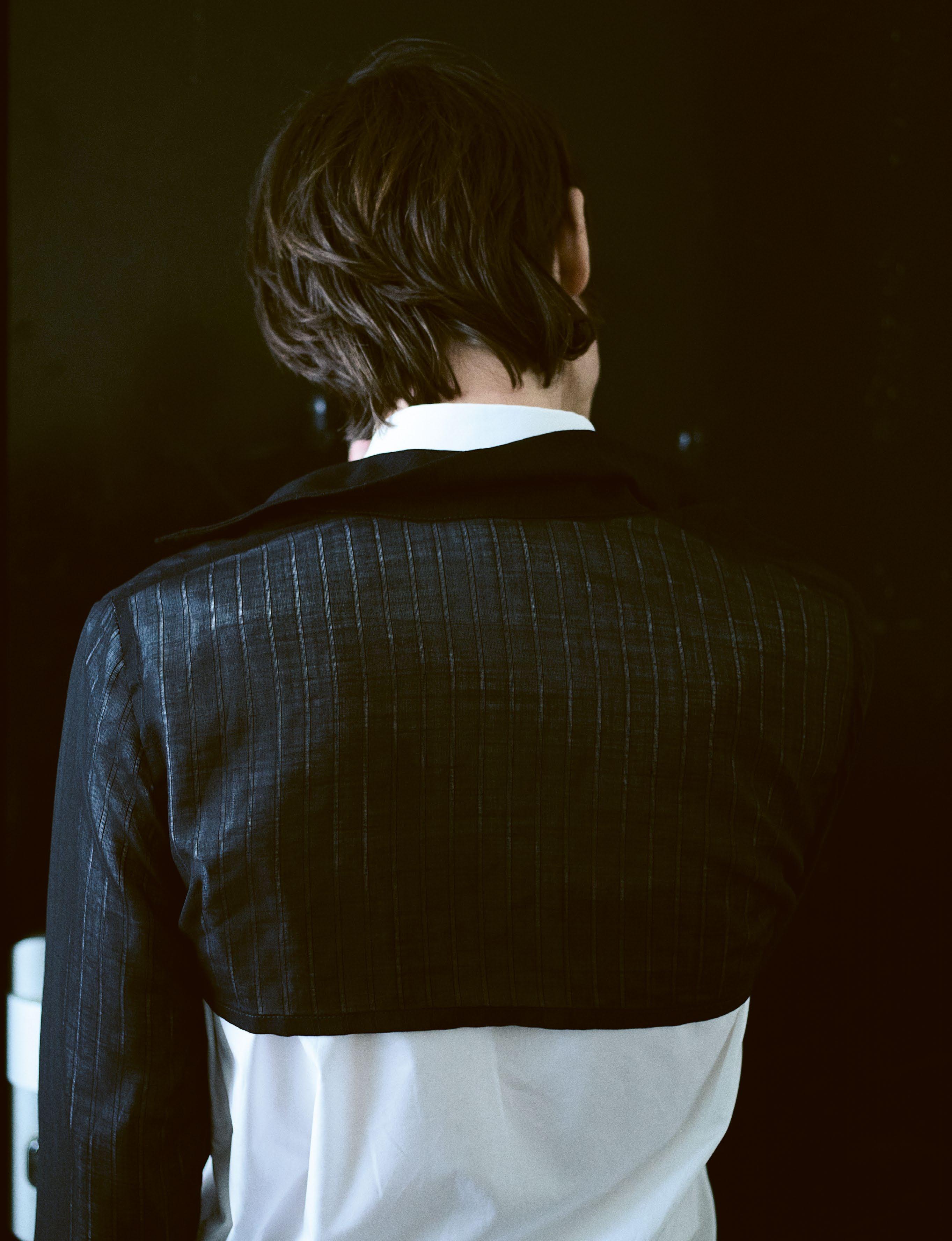

ByFedora Ab u

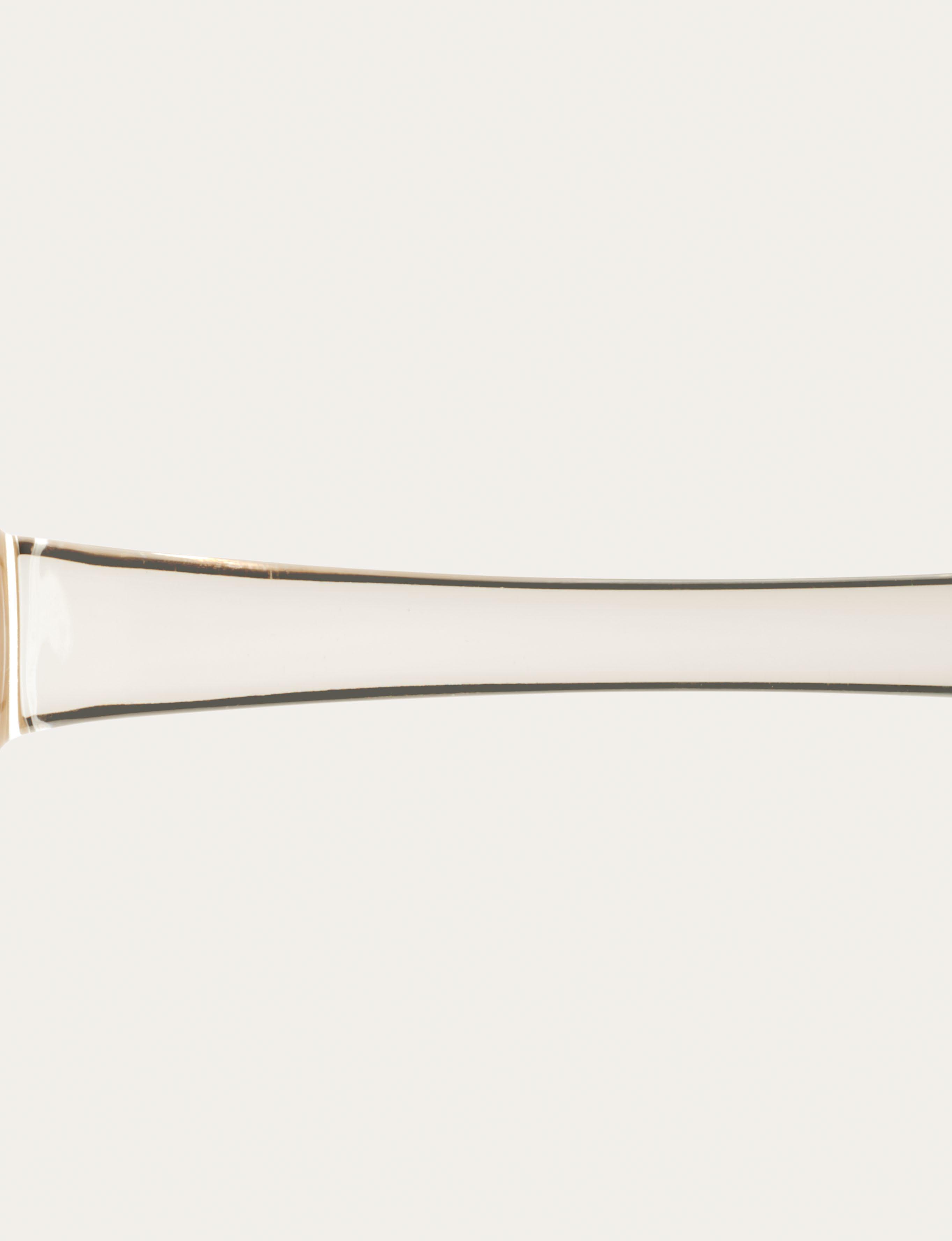

THERE’S NO OFFICIAL HANDBOOK for the fashion designer who suddenly finds themselves at the helm of a revered French haute couture house, and who must now navigate the tricky task of preserving its traditions while driving it into the future. Where some might opt to play safe, and others appear to abandon the founder’s vision almost entirely in favour of what feels most cutting-edge, Mr Kim Jones is one creative director who seems to have struck upon the perfect formula, creating menswear for Dior that’s covetable and undeniably contemporary yet always with an eye to the maison’s archives.

With his SS24 Dior Men’s collection, Jones has breathed new life into cannage. Derived from the French for ‘lattice’, the criss-cross style of stitching dates back to Dior’s founding in 1947 and has since become one of the house’s most enduring motifs. As the story goes, Christian Dior, a keen decorator, initially took inspiration from the Napoleon III cane chairs of his couture salon at 30 Avenue Montaigne and reimagined their woven intricacy in his creations. Decades later, in cannage’s most memorable outing, Gianfranco Ferré’s Dior stitched the motif into a boxy leather handbag that would eventually be christened the ‘Lady Dior’ in honour of its most famous wearer: Diana, Princess of Wales.

For Jones’ modern man, cannage takes countless forms: embroidered into richly textured coats and relaxed tailoring cut from boucle wool in navy blues and the house’s signature greys; graphically printed across cashmere-wool jacquard knits and cardigans. Chunky-soled Bufalo loafers are cast in quilted-leather and elevated in cannage cotton tweed.

Cannage tweeds also lend dimension and texture to the Dior Saddle Twin – a more compact version of the equestrian-inspired design first introduced under Galliano and later revived by Jones – while the Dior Charm (pictured), a newly unveiled satchel style, features laser-cut leather that evokes the Lady Dior. At its most inventive, cannage is reimagined in intricate 3D-print across rectangular-frame sunglasses in shades of grey, khaki and neon green.

But more than a mere nod to the house’s past, the SS24 collection is underpinned by clothes-making techniques that Dior has devoted decades to honing – elsewhere leather jackets and pinstriped shirts are hand-embroidered with jewel-like beading inspired by the founder’s cabochons. In an age where luxury fashion can at times feel removed from the craftmanship and quality that once defined it, Kim Jones’ Dior ensure the petites mains who prop up its atelier are as valued as they ever were.

59

.

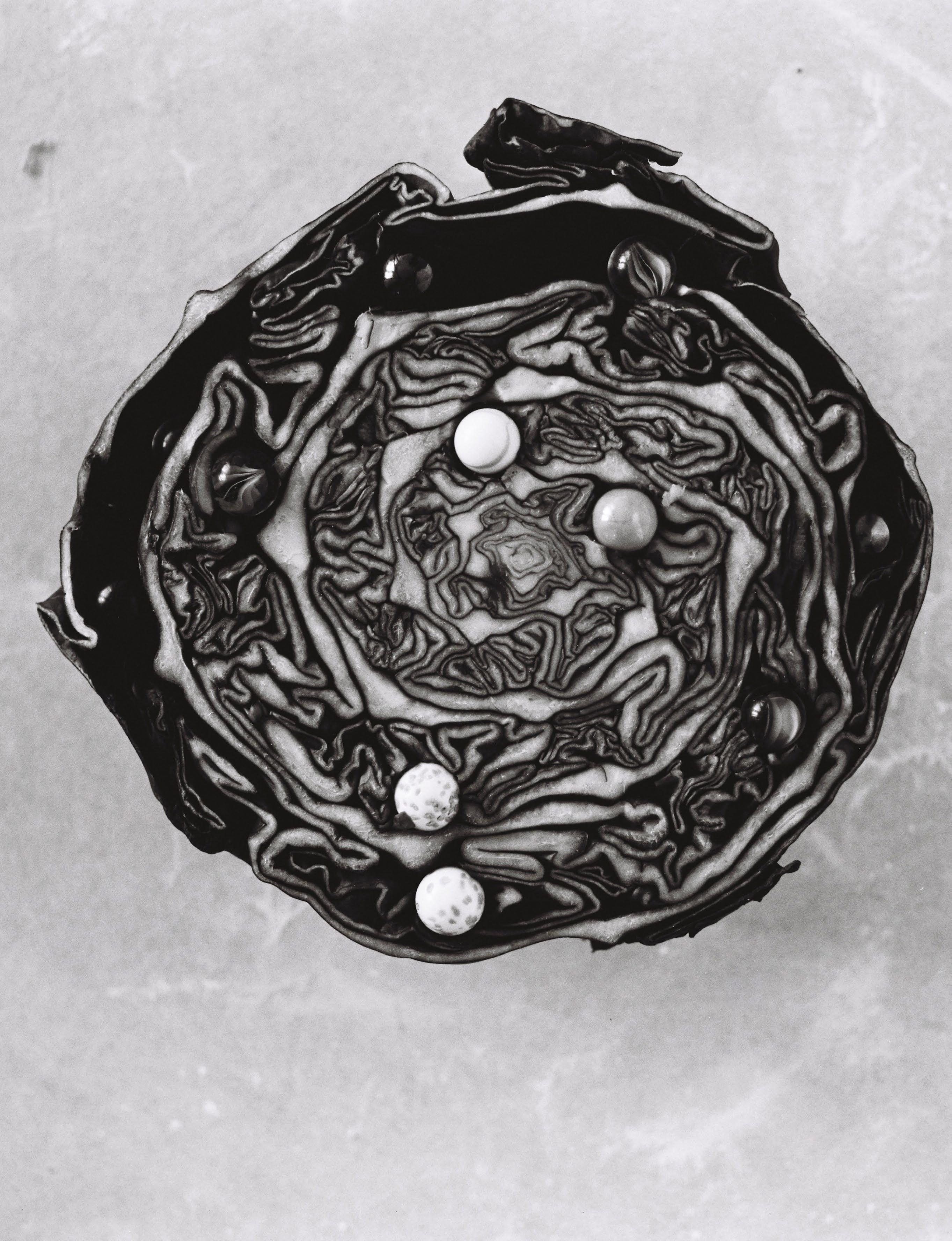

60

POMELLO SOURS. A spring-summer serve. Ingredients: 60ml Pomello

• 20ml fresh lemon juice

• 15ml sugar syrup

• 20ml egg white (optional)

1. Pour into a shaker with ice and shake! 2 Strain and pour back into the cocktail shaker, without ice Shake! 3 Pour into a coupe or rocks glass and serve.

61

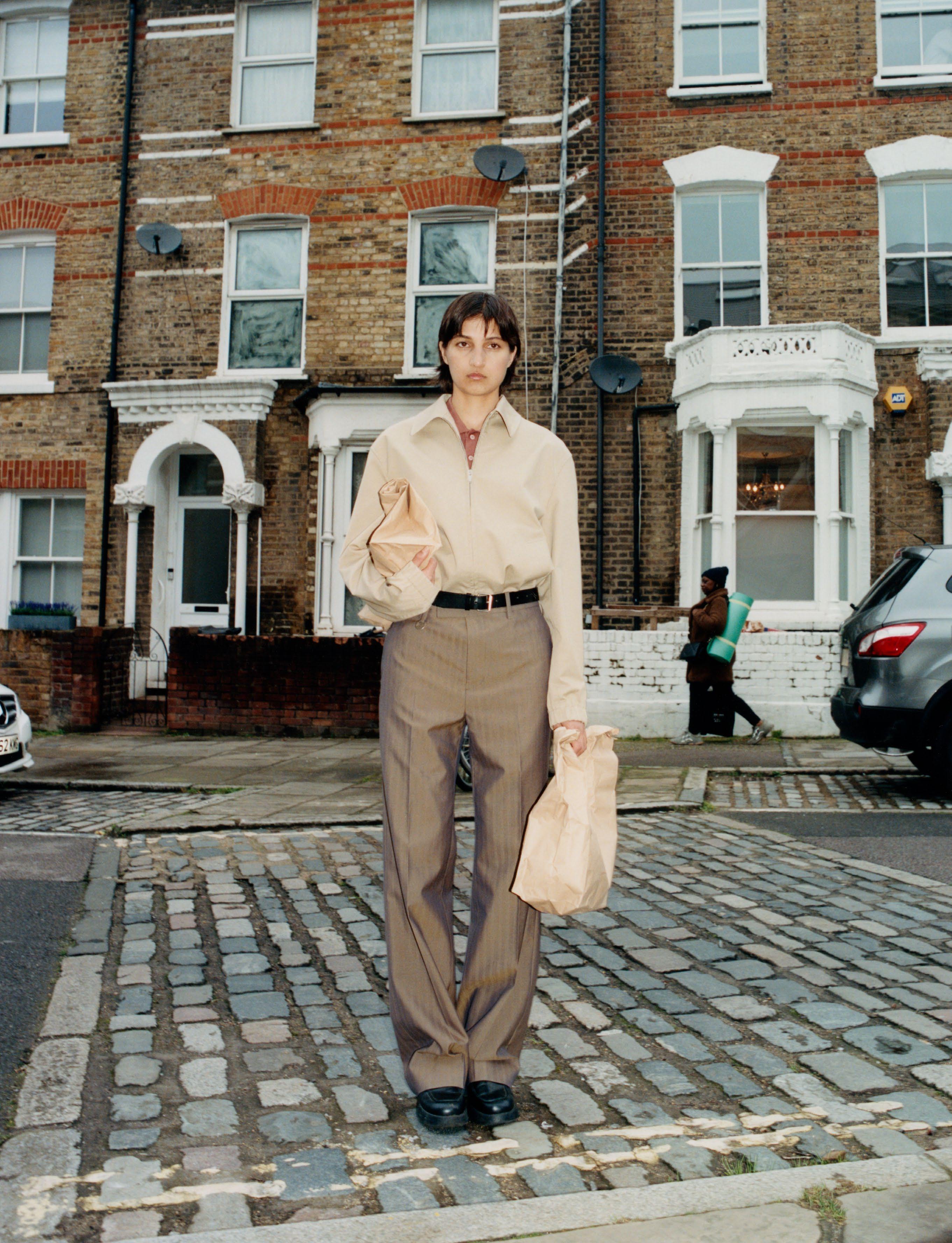

62

TIM SUMNER HAS been collecting paper bags for some time now, and as more and more people find out about the collection, more and more have been ofering him bags. With the collection approaching 2,000, he’s starting to say no to quite a few. “It makes me sound like I’m really picky, but sometimes it’s just space. You know, I don’t have a massive warehouse to put them in. It’s just a bit of racking and some boxes.”

Is it important that they’re bags? “I suppose it is important in a sense, but I don’t think it’s the be-all and end-all. It’s the history of it and the aesthetics.” There’s also the fact that they’d normally get thrown away. “They’re sort of designed for that day. They’re supposed to just be gone… you’re a nutter if you keep them. I kind of just love the fact that people collect all sorts of things now.” Part of the thinking behind the archive is just to share things that’d otherwise end up forgotten. He tells me “It’s good to collect,” but “it’s a shame for them to rot under someone’s stairs.”

I learn from Tim that the word ephemera comes from Ancient Greek for lasting only a day – making the bags, in some way, “the ultimate ephemera”. He notes that for how long they’re meant to last, a lot of efort used to go into them. Talking about places that still hand out paper bags, it seems the approach is to “make your own stamp, buy a load of bags and stamp it on… rather than doing a four-colour screen print or something.” As a collection, some things jump out that might have got lost over time. He says it “sort of tracks social history, things like coronations. You can see how the flavours of design have changed, and illustration.”

After our call, he emails me a picture of a recent find – a plain Selfridges bag, with ‘Selfridges’ written in Cooper Black. It’s part of an upcoming zine on department store bags. I’ve tried to look for that iteration of their logo online but turned up nothing. It’s lost on the internet, but it’s in this archive.

63

T h e P a p e r B a g A r c h i v e . B y S a m i r C h a d h a

DENGISED ROF TAHT YAD

ByMarieLeConte

WASHIT ALL DOWN. On the banya.

64

65

WHEN THEY TELL you about the banya, they usually start by explaining that you will get beaten. The Slavic sauna, they say, is like every other sauna except that, at some point, a man will pick up a bundle of birch twigs and tell you to lie down.

He will press some cold wet leaves on your face, then he will gently whip you, back and front, as others watch. They tell you that afterwards the man will make you jump into an ice bath, and you will not want to put your head in the water, but he will make you do it. You will, in time, realise that he was right, and had your best interests at heart. You will get very hot then very cold, and you will feel great.

What they do not say is that the odd, not wholly unerotic experience will not end there. Once you have recovered from your beating, you will sit at a table in a restaurant, on a wipeclean couch, and you will eat without putting any clothes on. Some sour cream may well end up over your naked thigh, or on your damp swimsuit. A slippery pickle may land on your wet stomach. Again, not wholly unerotic.

Is the banya a sensual place? Yes, without a doubt. Is it a sexual one? Even Russia isn’t sure. Then again, what would Russia know? As academic Ethan Pollock wrote in his book on the topic, “before there was Russia, there were banyas”. When Herodotus wrote of the tribes north of the Black Sea in 440 BCE, he noted their fondness for baths. Ibn Rusta, a Persian geographer and explorer, did the same in the 10th century.

Around two hundred years later, the Primary Chronicle – a history of the people of Kievan Rus, the eastern and northern European state which eventually gave birth to, among others, Ukraine and Russia – was written. In it, the unknown author spoke of hot, humid rooms, birch beatings and cold water. The banya, as the saying goes, is older even than the tsar.

For a millennium it was a conflicted and conflicting place, where people went to cleanse themselves after sex but also to have sex with each other. The steam both purified people and led them back towards sin.

Banya No.1, hidden away near Old Street in east London, has not existed for a thousand years, and it is not a den of sin. It opened in 2012 and is a rather more sedate afair. You must book a slot in advance, then be guided to your personal booth. Treatments are also sorted ahead of time and run like clockwork.

Still, there is something quietly thrilling about eating a meal when so much flesh is on display. Back in 2000, Anthony Bourdain filmed an episode of A Cook’s Tour in Russia, where he visited the banya. In one of the scenes, he and his guide are sitting topless, towels around their waists, sharing food and alcohol.

“Some smoked meats, country bread, some smoked…” he tells the camera. He pauses. “What kind of fish is that?” he asks. The question doesn’t get a definitive answer. Bourdain still tucks in, gnawing on pieces of skin with his teeth, his chest glistening with sweat.

Back in London, the fish is definitely herring, and it is salted and served with slices of sharp, raw onion, a marriage made in heaven. The mushrooms are pickled too, as are the Georgian gherkins.

Other cold foods include Ukrainian salo, which struggles to look appetising. What is salo? Simple: it’s pure pork fat. Sometimes it also features pig skin, or is marbled with meat. Here, it is neither. The slabs are white as snow, naked as the day they were born. Italian lardo can, at least, rely on its slices being paper thin, but now is not a time for subtlety – you are recovering from being very hot and very cold and what you need is thick slabs of fat, placed on even thicker slabs of rye bread.

Some may wash it down with beer, but here that feels like the wrong choice. An ice-cold shot of vodka, downed in one, cleanses the back of your throat and prepares it for what is to come. A bite from the pickle that was placed on top of the glass acts as a palate cleanser.

While the kitchen gets to work on the other dishes, you may as well go spend some more time in the sauna. Sweat out the salt, sweat out the booze, watch as others get beaten in front of you, jump in the ice pool, return to your seat. Somehow life feels lighter than it did 20 minutes ago. “Steam your bones and your whole body will be cured,” the Russians say, and you will come to believe that they are correct.

If you require more convincing, you may turn to the works of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Alexander Pushkin, Nikolay Karamzin, and countless others. In Notes from the House of the Dead, the former writes of convicts being let out at Christmas and allowed to go to the banya, much to the horror of a nobleman. As Pollock writes, “Dostoevsky’s Siberian banya was a no-man’s land, a liminal space, beyond good and evil and thus well suited for his exploration of morality.”

The banya turns up in The Brothers Karamazov as well where, Pollock continues, “Dostoevsky’s banya represents ambiguity – a place of sinful birth and disgust, as well as sanctity and wonder.” Conflict, always conflict, but never mind that. More food is here to be eaten.

There are now pelmeni in front of you, pillowy dumplings made of thick dough and “meat”. The menu did not reveal which animal it comes from. Eating them doesn’t either, but it doesn’t really matter, as long as you dip them in melting sour cream first. They’re meant to be eaten with a fork but, if no-one is watching, you can and should pick one up with your hand and lick your fingers afterwards. Be careful –some dill may end up under your fingernails.

The red, nearly burnt-orange borscht should be eaten with a spoon. There is no other way to pick up the pieces of beetroot and cabbage, and all that sour cream hiding at the bottom of the bowl. That’s the secret of Slavic cuisine: about half the dishes are vehicles for sour cream. No one is complaining.

To wash it all down you should be drinking Banya No.1’s homemade kvass, a fermented drink made from rye bread and honey. It is sold by the half litre and the litre but really, you could drink it by the gallon. If you want to imagine the taste, picture a Breton cider and subtract the apples. It’s sour and fizzy. People have been drinking it for over a thousand years.

In fact, people have been eating all of this for centuries and centuries. Salo, it is said, was first eaten in ancient times. Pickles predate Jesus Christ. Northern Europeans ate salted herring in medieval times. No-one quite knows

when humans started putting meat in dough, but it isn’t a recent development. Borscht was written about as a staple in Kyiv in the 16th century by merchant and traveller Martin Gruneweg. “Ruthenians rarely or never buy borscht,” he recounted in his diary, “because everyone prepares it at home, as it is their everyday food and drink.”

The banya isn’t really sexual but it is sensual, in the way that very old things can sometimes be. We have always had flesh and skin and heat and steam and food. It is reassuring to be reminded that we will always have those things.

There are tensions in the banya but that is the point. As anthropologist Dale Pesman wrote while researching Russian life in the 1990s, “the fact that baths are a locus for meeting and promiscuity, dirt and purity, power and equality, heat and cold, sobriety and drunkenness, health and illness, communion with others and contact with one’s own ‘deepest’ needs, as well as drink, song, and healing, makes them dushevnyi [soulful] – anything that unites things is.”

A Russian friend of Pollock’s once told him that “a person in a banya today might experience something akin to what a person experienced in a banya one hundred, or two hundred, or even one thousand years ago. Nothing here is new. The banya is eternal.” It has outlived millions, and it will outlive you. Long live the banya.

66

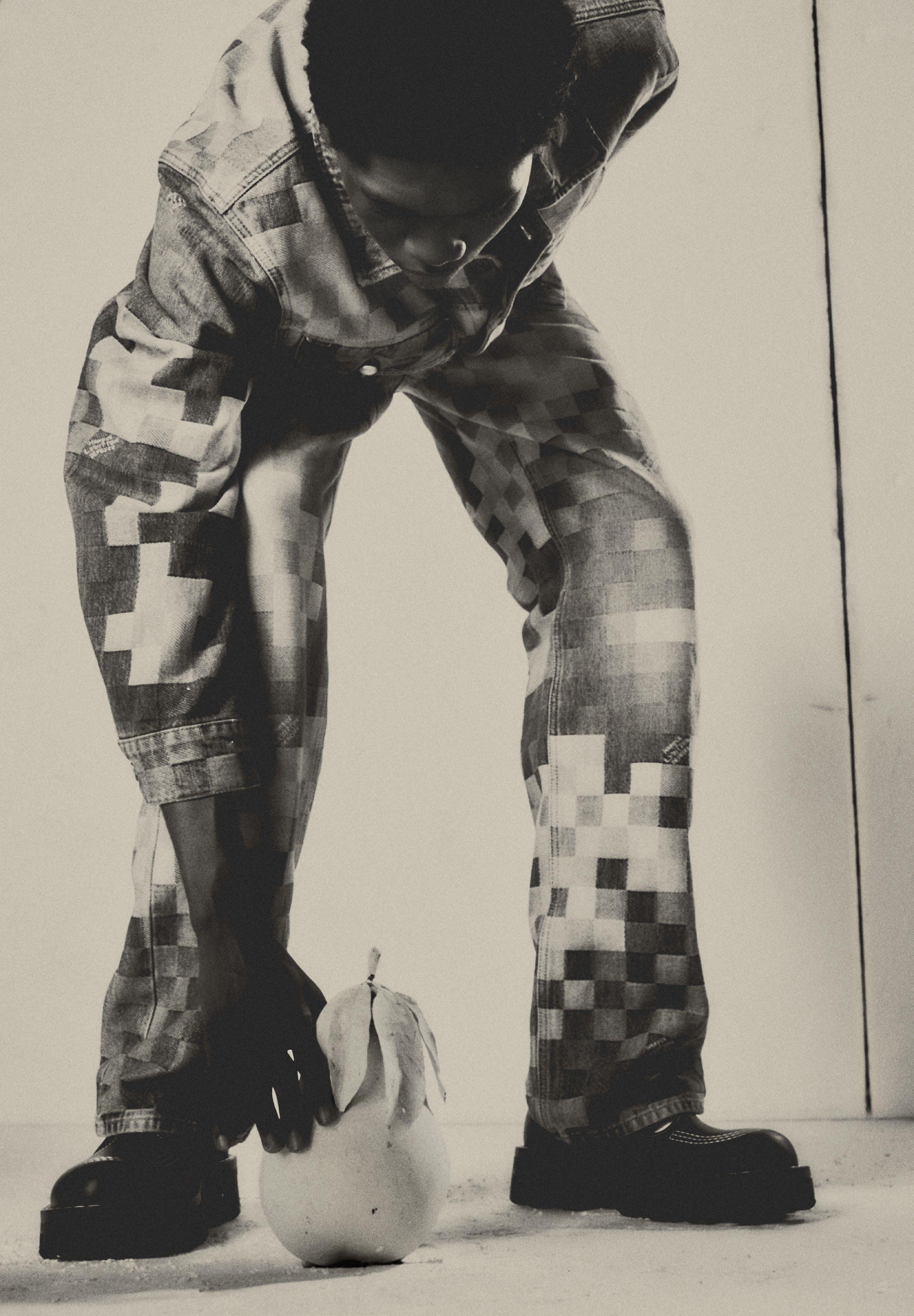

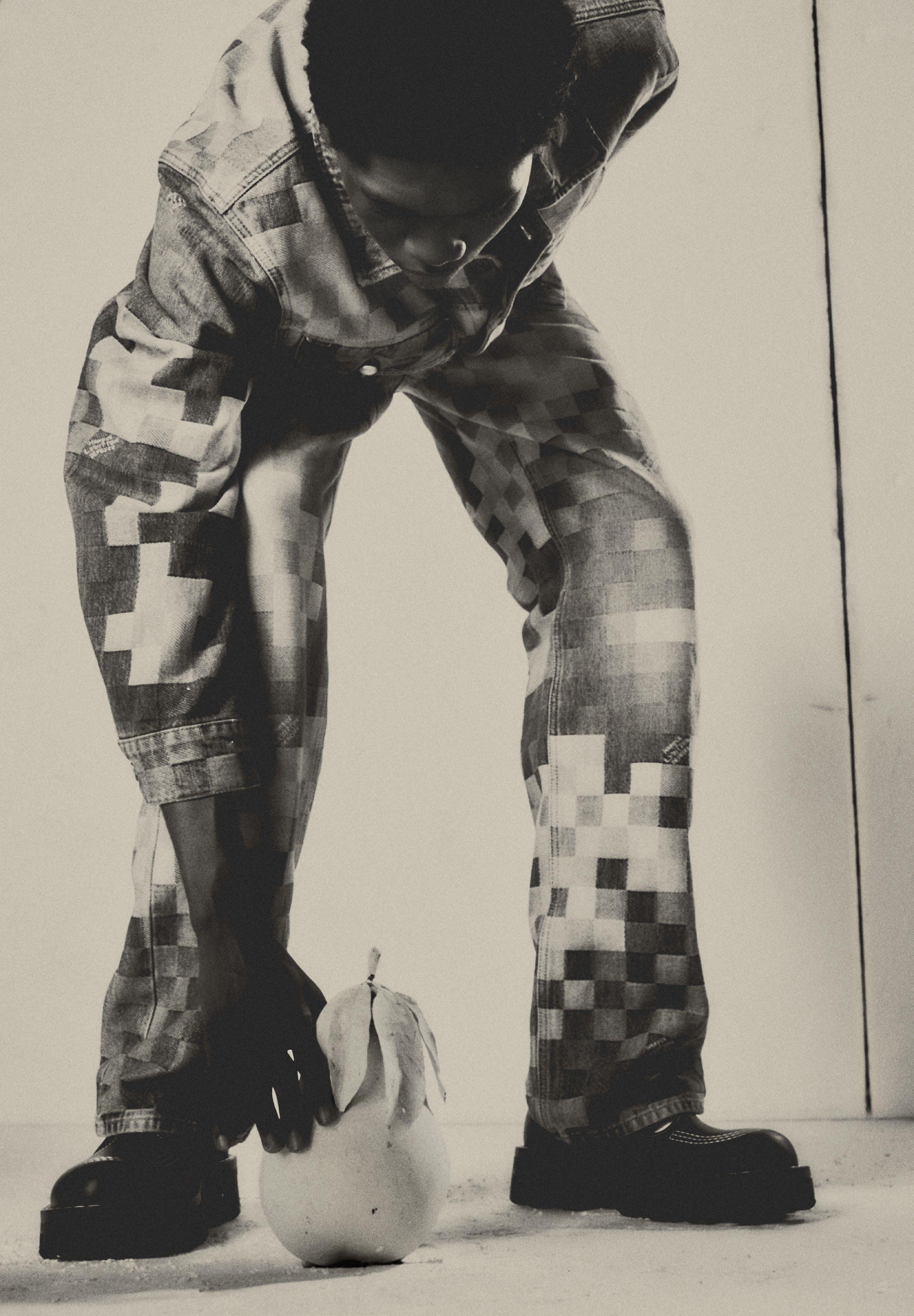

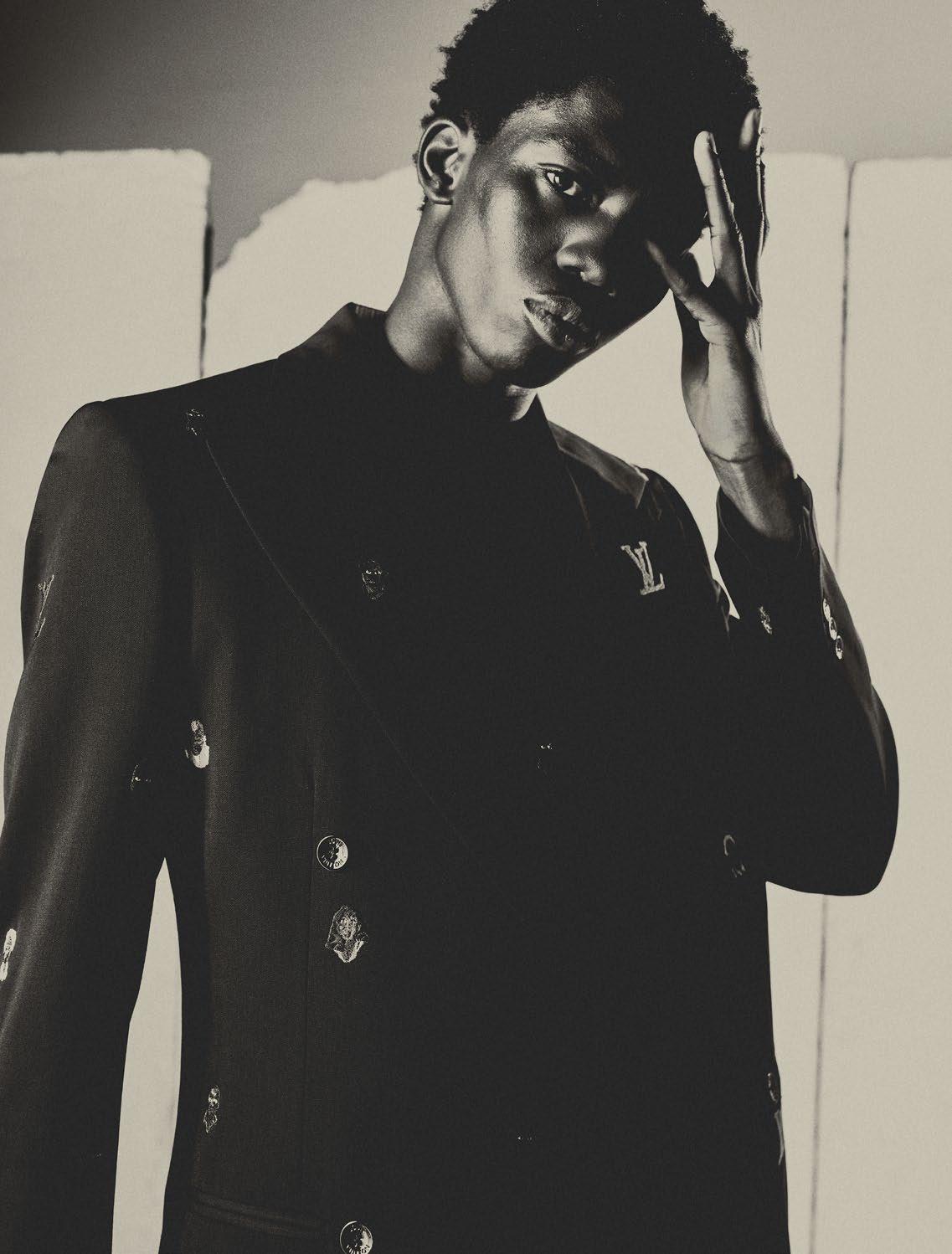

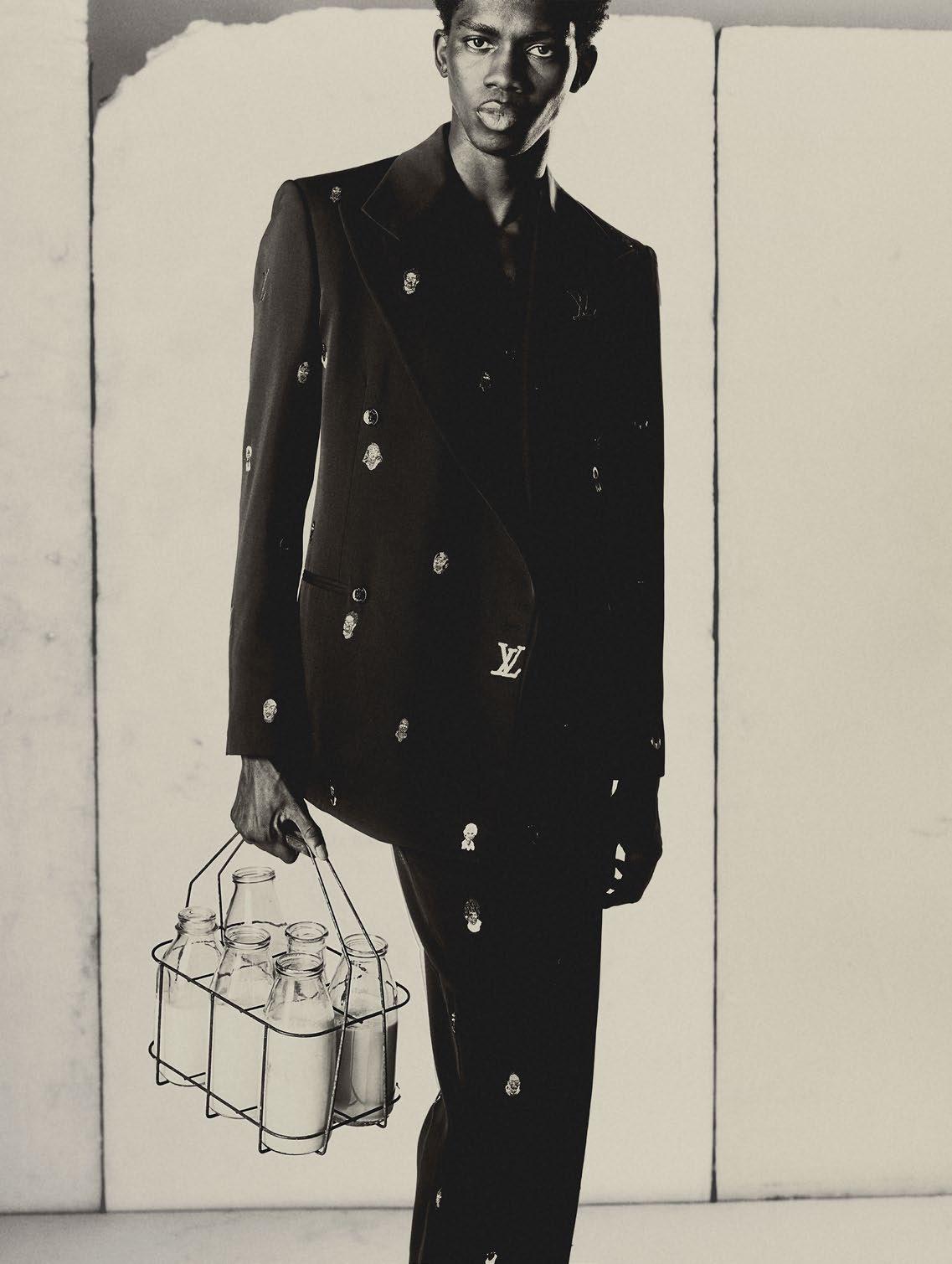

67

68 GELLING THE 70 FRIENDSHIP 78 AREAS FOR CHANGE HEAVEN SCENT 79 80 BEN WHISHAW CANINES, CANVASES 94 100 INGREDIENTS AND SAVOIR-FAIRE HARI NEF 104 114 CUPBOARDS AND POTS OF SHELVES,

69 COOKING WITH 122 SCORSESE 128 KE HUY QUAN UNEXPECTED 138 HARMONIES 142 RAY WINSTONE DETAIL THAT SHAPES 148 152 FABRIC INSTINCT NEVER BREAD 160 AND BUTTER 162 BRIAN COX

GELLING THE FRIENDSHIP

Lunch with Fergus Henderson, Margot Henderson & Jeremy Lee at Rochelle Canteen

INTERVIEW

Samir Chadha

PHOTOGRAPHY

Sophie Green

M.F.J.

IT’S BEEN SOME time since Jeremy Lee, Fergus Henderson and Margot Henderson all ate together, though in the 90s, when they were all making names for themselves as London cooks, that used to happen all the time.

Fergus guest-edited Port’s first food special, back in 2013. His nose-to-tail approach to cooking, popularised at St John, doesn’t seem as revolutionary as it might have done in the 90s, simply because it’s been so influential. We’re speaking in Rochelle Canteen; the restaurant Margot runs with partner Melanie Arnold.

Jeremy Lee: We skirted each other’s lives forever, so it would seem, amazingly. Because Ferg’s the same age as me, bar a few months. And both of us fell into cooking and the restaurant business. And I think when I started at Euphonium, because we only opened for dinner, I used to go down and buy bread at St John every day.

Margot Henderson: We were living in Earlham Street, which was quite a social gathering spot, wasn’t it? Literally, dinner party every week. I’d be on the phone, calling people, and then they would leave messages. I’d drop the kids of at school and stop in telephone boxes on the way, inviting people. And you wouldn’t know really how many people were coming.

Samir Chadha: You were working in kitchens all day and then hosting dinner parties at night?

MH: I did both. I mean, I was in the kitchen, but I wasn’t just in the kitchen, because I had small kids.

JL: There was still a lovely hub of food community in the West End, still, even then. A lot of which has moved on.

MH: But there is a new hub of restaurant community. They’re young.

JL: Yes, the youth, the next generation, who we love.

MH: But sometimes I feel that they think there never was, and they will think that it’s just all started. Yeah, I’m really sorry guys, it

73

was there before we were there, and it keeps on going.

JL: You have 400 years or so of restaurant history and food community, and growers and producers and makers. Particularly back then, if we weren’t cooking in kitchens, we were eating in restaurants. That’s what we seemed to do our whole time – or around the Earlham Street, and on occasion at mine. Yes, that always starts with a couple of pals, and then the next thing you know, you’re actually putting piles of magazines round the table and getting people to sit on them and going “I do need to get a few more chairs.” It was always an adventure.

MH: Building friendships, it’s often, for us, about sitting at the table. I always feel if you’ve invited somebody to your home, and they sit down at the table, that is sort of gelling the friendship. We were hungry for community, and we wanted all of that. And it’s fine to bump into people in bars and things, but if you really want to build on your friendship, you have to work on it, and it’s hard work. And to sit down, and once you’ve sat down and gathered like that, I think that is when you’re building on what is to come into the future.

JL: St John took of like a rocket. And this extraordinary thing, when folks suddenly realised there was such a thing as British food and produce and cooking. And what was so significant was this idea of – which had been bandied around forever – about keeping it simple, and seasonal, and use all of an animal. That strange thing, the Brits would go abroad and they would tuck into anything in Italy, in France, and then come back and go, you couldn’t possibly do it here. And what was Fegato alla Veneziana in Venice would be ‘liver and onions’ here, no one could eat liver and onions here. Call it Fegato alla Veneziana and they just tuck in with gusto, and you’re like, really?

MH: Do you sell much ofal?

JL: We do, but we had to rein it in. You can have an ofal starter and an ofal main course, so long as there’s a balance, you know, of some other dishes. That’s what the pie is great for. It ofsets everything.

MH: Fergus was really one of the first people to get the pie on the menu – back then, with his bone marrow, Trotter Gear, do you know about Trotter Gear?

JL: I love Trotter Gear, it was genius.

MH: Out of trotters, you make this sort of sauce, and that can go into things like your guinea fowl. So, [it can go] into more dry things [such as pie fillings] to bring in moisture and succulence. And we have blocks of it frozen in the freezer.

JL: Infinitely better than an OXO cube.

MH: It was meant to go into Waitrose.

JL: It did for a while, didn’t it?

Fergus Henderson: About two days, it was.

MH: I’m worried about the pastry now coming with the pie. Jeremy’s about to eat it. Oh, my God.

JL: No! Delicious.

SC: What are your favourite places to eat these days?

MH: Noble Rot, Ciao Bella, Kiln, Canton Arms, it’s our local pub. I love Koya.

74 GELLING THE FRIENDSHIP

75

JL: Nick Bramham [Quality Wines], Black Axe Mangal, Hoppers! You know, touch wood, but restaurants in London – they’re doing pretty well.

FH: You can come and stay anytime you like. You’re a good eater.

SC: It’s delicious and I will eat constantly, forever. Favourite pie, all of you?

FH: Pheasant and trotter, bone marrow in the middle.

MH: I always love a mutton pie.

JL: Guinea fowl and porcini, which we’re going to put on the menu at the pub [The Three Horseshoes in Batcombe, which Margot runs] next week.

MH: We make amazing rough puf [pastry] at the pub. And it’s really good. And we use this incredible flour from Landrace. Which I’m going to show you. I want to buy their flour here. They bring it up to London – Leila’s [Shop, on Calvert Avenue] gets it all.

MH: What’s your last meal?

JL: Grouse. Langoustines. Raspberries. And freshly churned ice cream.

FH: Sea urchins.

SC: What was yours going to be?

MH: I always feel like boiled ham and parsley sauce. It’s something I learned from Fergus and his mother. His mother was an amazing cook. You have a whole ham and then it’s poached really gently, with onions. And then you slice it thinly, parsley sauce.

JL: This is such a delightful, rare treat, to be sitting down properly and have some time with you. It’s the one thing – keeping up with your pals now is really hard. That’s a full-time job in itself.

MH: And if you’re not careful, they disappear.

SC: It’s a lot of work!

JL: Do it. You need it. These are important. Some of the most important people in my life.

77

AREAS FOR CHANGE

Katie Chung discusses her creative approach and culinary preference

By Jenna Mahale

IN KATIE CHUNG’S favourite restaurant, the walls are lined with vinyl LPs. The health-conscious creative director of MCM accessories doesn’t indulge in much, but at Buto – a European-Korean fusion restaurant and Hansik bar in Seoul’s Yongsan District – she’ll treat herself to a fried delight: a hot, fragrant order of Eggplant Menbosha. “Unlike other restaurants, they wrap shrimp into eggplant instead of bread, and colour it with squid ink,” she tells me. “There’s this vintage, classic ambiance where, regardless of where I sit, I feel a real sense of comfort during the meal.”

A Central Saint Martins graduate, Chung started designing for her mother’s label Wooyoungmi: “I naturally assumed I had to pursue this path from a young age.” She doesn’t see this as a “particularly glamorous starting point” (though it arguably is) but rather “one that felt natural and familiar”. Now at MCM, working in tandem with global creative lead

Tina Lutz, she likens her career to that of a musician. “I always think of brand directing as akin to conducting an orchestra. Just as each orchestra varies in size, instruments, and the people performing, directing a fashion brand entails a great deal of understanding and adapting to unique circumstances and requirements.” Her approach is “not about rigidly adhering to my own methods or style, but rather comprehending the working methods involved in conceptualising each brand’s core products, and suggesting areas for change.”

Having lived in both London and Paris before settling in Seoul, Chung feels that certain localities have had their time in the sun as cultural and artistic hubs. “What I’ve come to realise is that there are cities capable of exerting significant cultural influence on the world, during their own eras.” In years past, she says, “cities like London, Tokyo, Antwerp and New York had periods of prominence for

creatives”. But times change. “Personally, I feel that Seoul is experiencing such a period now.” The city’s vibrant food culture is just one indicator of sound cultural health, and Seoul’s is particularly compelling. While she aims to prioritise low-sugar, high-protein foods overall, Chung’s policy is to – at a minimum – sample everything. “When something new is launched, I’m inclined to give it a try out of curiosity, at least once. Myself included, Koreans often enjoy dining at casual eateries like chimaek,” she says, referring to the heavenly pairing of fried chicken and beer served in the evening by many South Korean restaurants, as well as a few specialty chains, some of which have made their way across the world. But the company is often the best part: “I love to get together with friends or family to indulge in those experiences. It’s important to have unique spaces for people to socialise over food,” she adds, “and shared moments”.

78 PHOTOGRAPHY: DONGKYUN VAK

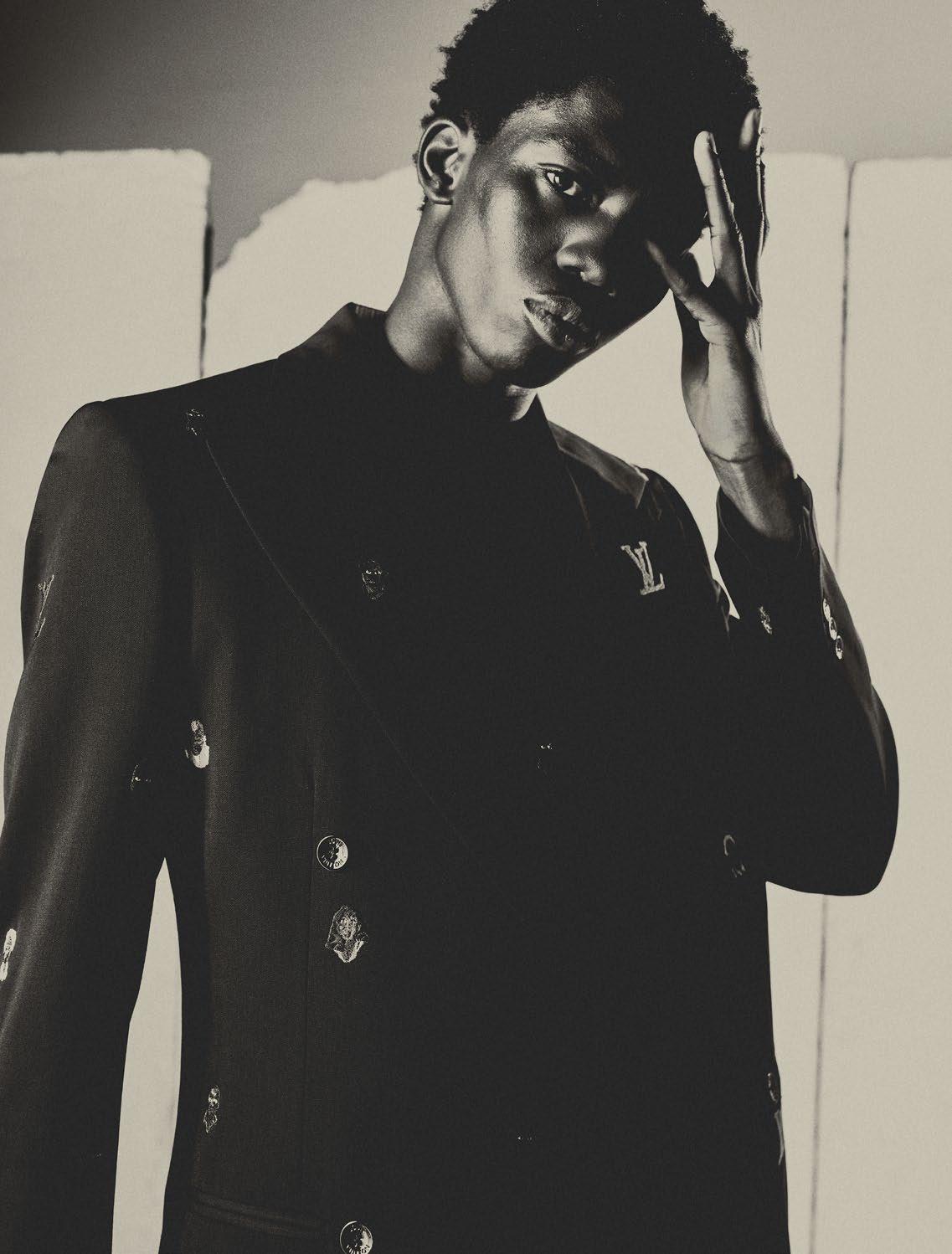

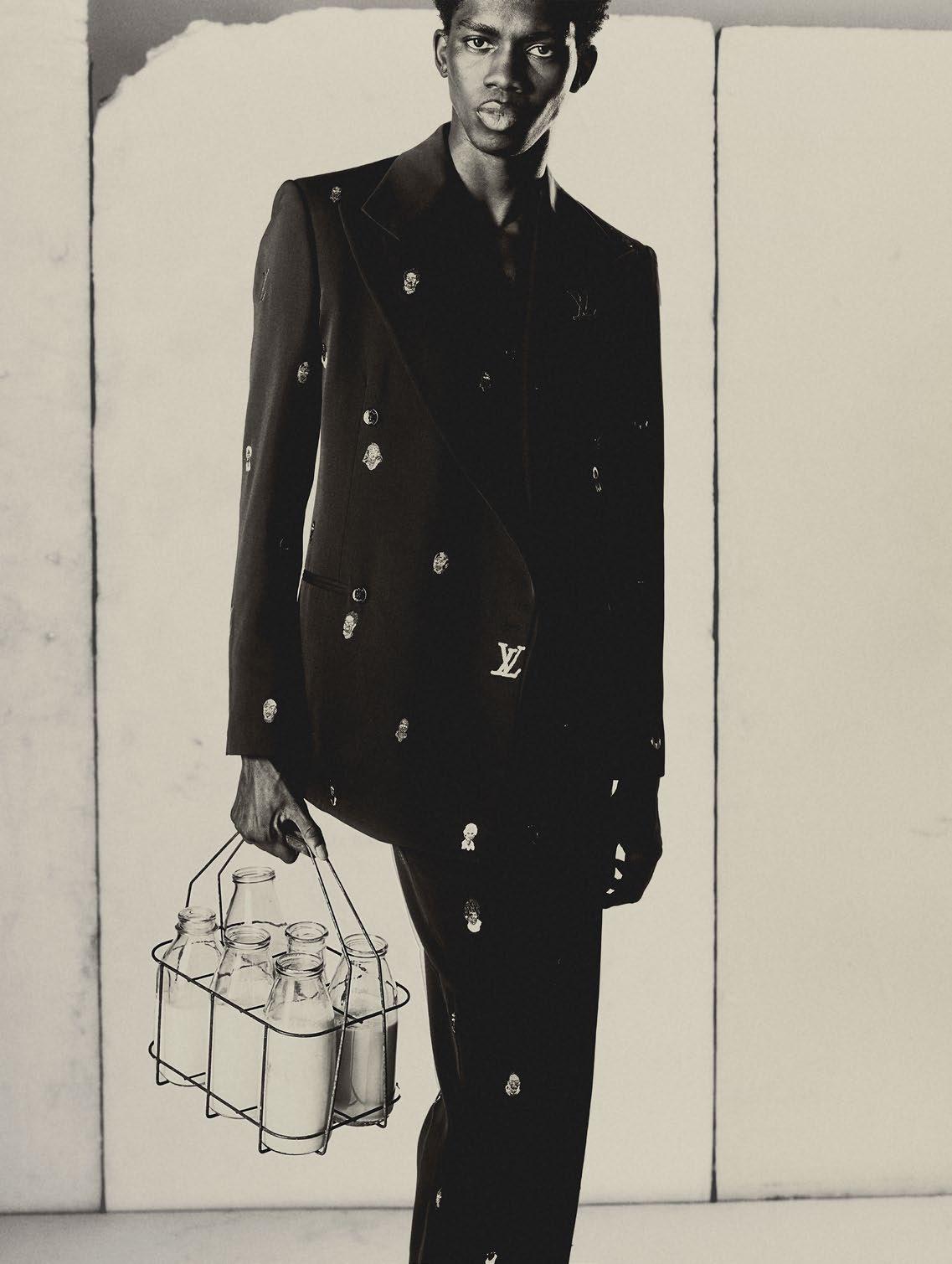

HEAVEN SCENT

A new book from Louis Vuitton reflects on fragrances’ roots

By Samir Chadha

SCENT IS, ARGUABLY and famously, one of the hardest experiences to reliably recreate – it relies on fleeting, volatile molecules that don’t travel well. Louis Vuitton: A Perfume Atlas hopes to trace those journeys, tracking core notes in iconic fragrances back to their inspirational and chemical sources.

One such subject is the Sicilian mandarin. A core part of Le Jour Se Lève, its presence evokes a hurriedly unwrapped fruit, or a trip to the Mediterranean, or a kick with breakfast. Lionel Paillès, the book’s author, tells us that the fruit’s olfactory characteristics vary wildly across the year – shifting from a piquancy in the autumn harvest to a rich sweetness in late winter. If perfumery is about layering, the mandarin is particularly fitting; especially in comparison to its blossom, not part of this essence. In it, you find orange blossom, other citrus, and a surprising hint of thyme.

Another subject is the Peru balsam, illustrated here by Aurore de la Morinerie. Paillès traces the mythological history of the plant, and then the diligence in its extraction – extracted with a mix of climbing, incision, and well-placed flames. The products of the tree, with their unmistakable warm, comforting scent, have also been treasured for hundreds of years for their medicinal properties. Perhaps that’s the origin of the association.

Behind all of the scents these elements coalesce into, there’s a distant but vivid natural root, and beneath that lies centuries of legend, memory and experience.

79 PHOTOGRAPHY: ADAM BARCLAY

BEN WHISHAW ALL FOOTWEAR MANOLO BLAHNIK WORDS KERRY CROWE

PHOTOGRAPHY CHIESKA FORTUNE SMITH STYLING NAOMI MILLER

Ben Whishaw’s roles to date have included Q in the Bond films, Paddington Bear, and Hamlet. He’s adapted to all of them, but has maintained a sensibility all his own throughout, one that’s won him both awards and adoration. He sat down to lunch in London with Port’s Kerry Crowe

SLIGHT OF FRAME and rufed, with dark, doleful eyes, Ben Whishaw embodies a unique gentleness. With over 40 film credits to his name and numerous stage appearances, he has worked with some of the most exciting directors in the business, including Jane Campion (Bright Star), Yorgos Lanthimos (The Lobster) and the Wachowskis (Cloud Atlas). He brings a humane urgency to each role, elevating characters’ better qualities to become the very beating heart of their scenes and evoking deep pathos in their lesser traits.

Born in England in 1980, into an unassuming Bedfordshire life without the early privilege enjoyed by many high-profile actors, he attributes his career, at least in part, to the influence of an amateur dramatics teacher in his home town named Rory Reynolds. “If I hadn’t met him and gone to that youth theatre, I’m not

sure I’d be doing it, because I don’t think that’s a path I would have found. It’s amazing really,” Whishaw tells me. “Rory treated all of us like we were little artists, like little professionals. He would give you an end-of-term report,” he says with tangible incredulity and gratitude, “and it was just a Sunday. He opened up all sorts of things to me: theatre and literature and art and performance and acting.”

Did it feel like a leap then, to go from this world to the hallowed studios of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where he would later train? He thinks. “Yes, actually. I do remember feeling, like… Woah!” He feigns shock. “Like, when somebody first mentioned something to me about the idea of going to ‘drama school’, I thought, ‘What is that? ’ And I remember thinking quite distinctly at one point that if I could just get there, that would be enough. I think I must have been quite determined to…” He searches for the right word. “I think I must have been quite determined,” he resolves.

“Although, I was also really fortunate: when I went to drama school, I managed to get the last of a thing that’s been discontinued and scrapped, which is a dance and drama award.

So if you were from a background or a family that couldn’t pay for the course, which was expensive,” he smiles emphatically, “you were supported by this grant. They were scrapped literally the next year, so I just got there in the nick of time. I think I was very lucky in that sense. I think that for people who came after me, it’s been much harder, and that’s not a good thing.” He briefly looks sombre at the thought of the dire state of arts funding in the world beyond our peaceful room.

I’m reminded of This is Going to Hurt, the 2022 television series based on former NHS doctor Adam Kay’s memoir about his time in the profession. Both Kay’s candid book and screen adaptation deploy warts-and-all industry insights, including of his own personal failings, and Whishaw – who plays Kay, in a BAFTA-winning performance – brings the role to life with such empathy that the viewers’ commitment to the protagonist is never threatened, despite his occasional misanthropic cynicism. However, it is the current state of the health service that forces its way through as the primary cause of many of these problems – Herculean shifts leading to exhaustion and depression and, in turn, fractured personal

83 BEN WHISHAW

PRODUCTION: LOCK STUDIOS

DIGITAL OPERATOR: LAURA HECKFORD

DOP SELF SHOOTER: MATTIAS PETTERSSON

SET DESIGNER: GEMMA TICKLE

HAIR: JODY TAYLOR

SKIN: NATHALIE ELENI

85 BEN WHISHAW

relationships, for example. In taking the part, how important was exposing these structural issues to Whishaw? Did it feel like a battle cry for the NHS? “It felt very important, yes, and it was very much what Adam Kay wished for it to be, a sort of battle cry, and a love letter.” He continues: “He wanted it to have social impact, and, yeah, for it to be really honest, especially about mental health with the people working in the NHS.”

In 2023, Whishaw worked with director Ira Sachs on the French film Passages, playing Martin, husband to Franz Rogowski’s Tomas – a passionate and intellectually scintillating but emotionally infuriating film director. The film is a heady, erotic continental love story, following Tomas as he embarks on an afair with Agathe (Adèle Exarchopoulos). The scenes between Rogowski and Whishaw are electric in the clashing of the two performers: Tomas is visceral and muscular, utterly without self-doubt, while Martin is considered and considerate, and sometimes seems frighteningly fragile, caught in his husband’s vortex. “Acting isn’t really about pretending or acting, it’s about what’s really happening, I think,” Whishaw explains of their onscreen dynamic. “I just found Franz really compelling as a person and as an actor and as a presence. I just loved being in his company. I loved talking to him and being quiet with him… I loved what he thought about stuf, about life, about films. He really occupied my full attention, and that’s not something you can really pretend or manufacture or act – it just kind of is what it is.” He continues: “But it was also special, because Ira Sachs made an environment where what I’ve just described was allowed for and was given space and then he would capture it, and it wasn’t like... this is what’s written, we’re going to do it exactly like this. Every day it felt like, well this is what we’ve got, but… is it right? Maybe let’s cut this, or maybe let’s do that. It was very alive.”

Discussing the essentials of his craft is where Whishaw comes to life. I mention having previously heard that he likes it when a director says, ‘Let’s play four pages without stopping.’ “Ooh yeah, I love that,” he says, straightening up and grinning at the thought. “It’s lovely when you’re given the space to do the scene; it’s quite hard to do little bits,” he says. “Some of the things that are hardest are the things that will look the easiest, and you’ve gone… that was really fucking hard, just to do that one little bit! Some of the things when people will say, ‘Wow, that was so impressive’ – you’re like… that was the easy part!”

Can he give an example of this in action? “Sometimes, filming, you have to react to something that’s not happening. In actual fact, it’s really hard! Coz there’s no… you’re not receiving anything: you have to conjure it all up. I know you could say that’s the job, but you’re always looking to not do any acting, if possible,” he laughs. “So when you have to go, ‘Oh, there’s an explosion!’ but there’s no explosion and you are just coldly standing there in front of the camera, and it’s scrutinising your face… that’s hard. But it would be nothing; it would be like a second [clicks fingers] in the

86

film. But if you had four pages, that would be lovely.” He smiles softly again.

“It’s also lovely when a director is really specific about what they want – they have a specific vision and a specific taste or sensibility. One of the hardest things is when you’ve no idea what you’re being asked to do. And then the worst thing is if someone wants to talk too much. That’s terrible! You sometimes need very basic instructions, like ‘go faster’, or ‘slower’, or ‘don’t think about it’ or ‘less’.” And what happens when a director talks too much? “Well, you open a box of things that are irrelevant.”

I tell him that I’ve heard him suggest in the past that he can feel shy around directors. “Oh yeah, I do actually. I always think they will… I always think they’re going to…” he pauses for a moment as he searches for the right words, before exclaiming, “fire me!” We both laugh. “Oh dear. Yeah, you feel like you’re going to let them down. Or might let them down, or it’s not going to be good enough. But I’m trying to overcome that, coz, you know, perhaps that’s not a very healthy or useful attitude.”

Clearly Whishaw is too humble to recognise himself as having produced some of the finest acting work of his generation, but he nonetheless continues to exert himself in his varied stage and screen career. His weary medic of This is Going to Hurt and troubled lover of Passages signal a shift from the quixotic boyishness for which he was once known into something more mature and complex. An as-yet-unreleased project sees him as the multifarious Russian political dissident and poet Eduard Limonov in Kirill Serebrennikov’s Limonov: The Ballad of Eddie – another repertoire-widening curveball, based on the eponymous biographical novel by Emmanuel Carrère. “He’s an amazing director, Kirill. I felt like I was working with a really incredible artist who was a truly creative person.” (Conversation with Whishaw is liberally interspersed with heartfelt compliments and praise for

others wherever he can find an opportunity.)