18 minute read

From the Office of Development & Alumni Affairs: The William A. Crimmins ’48 Scholarship Fund

PORTSMOUTH ABBEY SCHOOL IS FORTUNATE to enjoy philanthropic support from a broad range of constituents who share the common interest of ensuring that the School can fulfill its mission of helping young men and women grow in knowledge and grace. This support can take many forms, but it usually falls into one of three categories: 1) the Annual Fund, which provides current use dollars to help fund the School’s operating budget, including importantly financial aid, 2) capital giving, which typically supports the construction or renovation of a building or the grounds, and 3) endowment giving, which through a current or planned gift, provides ongoing support of the School through the interest earned from a permanent fund. While all three are important, the Annual Fund remains paramount. But many donors choose to make gifts over and above the Annual Fund to one of the other two categories. The newly created William A. Crimmins ‘48 Scholarship Fund for Arts, Athletics, and Civilization is one example of endowment giving.

Established in the fall of 2020, the William A. Crimmins ’48 Scholarship Fund honors William “Bill” Crimmins for his many contributions to Portsmouth throughout his long association with the School as a student, teacher, coach, parent, and benefactor. The scholarship reflects Bill’s unwavering commitment to the well-being and success of students, particularly those in financial need, and his support of the Monastery and School over the course of many years.

Created by former students and faculty colleagues in recognition of Bill’s exceptional and enduring contributions to Portsmouth, the fund will be used to provide tuition, room and board, and a clothing/travel allowance for candidates who demonstrate the well-rounded character of the student-athlete with the desire and capability to contribute in their own unique way to the Portsmouth Abbey School community. A small travel allowance would include costs for exposure to arts/civilization travel within the School curriculum that recipients of the scholarship might not otherwise be able to afford.

Should the fund reach the $1 million mark, the School will award a single scholarship to a recipient who will be known as the Crimmins Scholar. The Crimmins Scholar would be expected to complete a project centered on some aspect of arts or civilization during his or her Fifth or Sixth Form that would then be shared with alumni and the rest of the School community.

We thank Jamie MacGuire ’70 for capturing Bill’s story in the following article and hope you enjoy learning more about his fascinating life and unique connection to the School. If you wish to contribute to the William A. Crimmins ’48 Scholarship Fund, please contact the Office of Development & Alumni Affairs at alumni@portsmouthabbey.org or 401-643-1291.

Matthew P. Walter Assistant Headmaster for Advancement

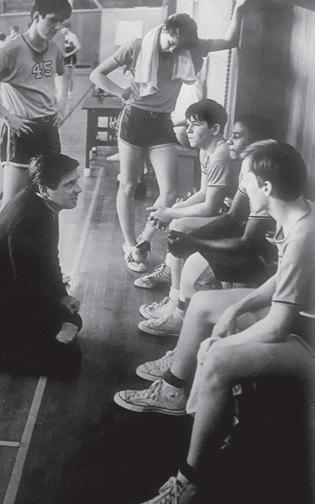

Bill Crimmins, left, coaching the basketball team in 1968, including Tim Tully, Paul Ferrarone, Marvin George and Gill Kerr, all from the Class of 1971

The William A. Crimmins ’48 Scholarship Fund: A Legacy of Kindness and Compassion

By James P. MacGuire ’70

The establishment by alumni, former faculty and friends of the William A. Crimmins ’48 Scholarship Fund is a signal event in the School’s history, connecting a precious link to the School’s founder, the upcoming celebration of the School’s Centenary, and our second century. Bill Crimmins has a unique history of contributing to the well-being of Portsmouth Abbey School through his support of the monastery, school, individual students, and even fellow faculty members.

Younger members of the Portsmouth Abbey family might well ask: Who is Bill Crimmins and how did he come to Portsmouth Priory? The answer is as colorful as William A. Crimmins himself.

Some History

Bill Crimmins is descended from the Duke of Bedford, father of both Queen Victoria and Bill’s grandfather Arthur. Arthur wed Lady Chance of Dublin whose marriage produced Bill’s mother, Ethel.”Ethel studied medicine at Oxford and married Thomas Crimmins, an American who graduated from Harvard, studied at Brasenose College, Oxford, then worked as the European rep for the First National Bank of Boston in London, Paris, Munich and Rome. Strong-minded and strongwilled, Ethel brought her husband back to their country seat, outside Cobh in County Cork where she enjoyed fox hunting.

“The local hunt often started there,” Bill said of his mother. “She raised poodles, had twelve of them, and they were more welcome in the drawing room than I. I grew up in the kitchens, with what my mother called the peasants, whom I loved. There was a Nana who was too old to handle me, so they gave me to a sixteen-year-old maid, Kathleen.”

“My father drowned when I was almost three. He was sailing off Cobh and the boat turned over. A doctor friend of his was on shore and saw him and ran to start his motor launch. My father clambered up the upside-down hull and gave the all clear sign. But the plugs in the 8-cylinder motor were all wet and had to be dried, so when the doctor looked up again my father had disappeared. He had suffered a heart attack and drowned.”

“At the age of four I was sent off to London with Kathleen to be deposited at a boarding school in St. John’s Wood. It was cold and the food was miserable, and Kathleen wouldn’t leave me. She called the one number she had been given in case of an emergency. It was Sir Charles Bell, an eminent London doctor and my mother’s cousin. He heard Kathleen’s story and said, ‘You bring that boy to me at once.’

Bill, left, catches up with E. J. Dionne ’69 at reunion.

Kathleen later came with the Crimmins to America, and Bill took care of her until the end of her life.

Coming to Portsmouth

At the Yale Club of New York dinner celebrating the creation of the Dom Andrew Jenks Chair in Mathematics on St. Andrew’s Night in 2011, Bill was the last speaker. His remarks, which tell of his coming to Portsmouth, resulted in a standing ovation and more than a few tears. Here are his own words from that night:

“I have been asked to tell a story about an encounter I had with Andrew as a child. Many stories have been told about him: the hamburgers or pancakes he kept in his habit pockets, his brilliance, his volatility, and above all his thoughtfulness. My story deals with his compassion. However, I should set the stage.”

“When I was about three and a half, I started exhibiting a slightly irregular pattern of walking, most likely brought on by a fall my mother had while pregnant and the touch of cerebral palsy this resulted in for me. Unable to bear the sight of my ungainly movement, she sent me away to school in England.”

“The trip entailed crossing the Irish Sea from Cork to Swansea, Wales, by overnight steamer, thence the train from Cardiff to London: a four-hour ride, where I was met from someone from the school at the station. I was escorted for the first two years, but at five I was deemed old enough to make this trip by myself.”

“So, I crossed the sea with a tag attached to my lapel, ‘Deliver to Charring Cross Station.’” Thus, sent like a package, I rode in the baggage car. This turned out to be a rather happy place – things went on and off at stops, and the Welsh workers liked to sing and so did I.” “I made the trip back and forth for five years until the war broke out and my American grandfather, who had made his fortune in the wool trade in Fitchburg and then gone into banking, insisted the family come here to his summer place in Camden, Maine, to protect us from the troubles in Europe. His plan was thwarted, however, when my brother Hugh, at the age of nineteen, joined the Canadian Air Force, and my other brother Tom joined the ROTC program at Princeton to become a Marine. I was put in Fessenden School where I sorely missed my brothers as they had been my anchors to windward in the choppy waters of my maternal sea.”

“A year or so later my mother decided I should have a Catholic education and I came to Portsmouth to interview, where I first met Andrew, then a brother, and attended a Conventual Mass. Andrew was charming, but I found the Mass rather dull. I was used to more lively hymns which we frequently rewrote: ‘Hark the herald angels sing, Mrs. Simpson’s pinched our King.’ So, in spite of his charm I wanted to stay at Fessenden.”

“Dear Mama persisted, and Father Gregory Borgstedt opened up a First Form for me and seven other boys. Despite the fact my mind was often with my brothers, I fell in love with Portsmouth. Several exceptional men made this possible: Andrew, Hilary, and, of course, Father Hugh, for whom I often served his private Mass.” “I was there for about two-and-a-half years before my brother, Hugh, was shot down on D-Day, 1944…my father, and now my brother were both gone. Less than a year later, on a dark, blustery April evening, Father Bede informed me that my eldest brother had been killed on Okinawa.”

“Overwhelmed with rage, I asked permission to go out. Once beyond the confines of the building, I

Bill at Peter Raho ’70 and his wife, Liz’s, wedding in Greene, RI circa 1982. Kneeling are Joe Raho ’72, Jamie MacGuire ’70, Byron Grant ’70 and John Melia ’70. Standing are Jay Hector ’74, Noel King ’72, Peter Tovar ’72, Peter Buckley ’72, Nicholas Raho, Bill, Liz, Pete, Fr. Peter and, and Denis Hector ’70.

Christopher Buckley ’70, Bill Crimmins ’48 and Jamie MacGuire ’70

began shouting at the gods. I strode up the alley of huge elms then along the side of the Manor House driveway. My voice dissolved into the heavens, muffled by the roar of the wind in the branches above.”

“Gradually I became aware that someone had been walking with me. Andrew’s quiet presence and loving concern eventually calmed me down, and I returned to St. Benet’s and he to the Manor House – having never said a word, but then none was necessary. Thomas A. Kempis once said, ‘I would rather feel compassion than know its definition.’ Andrew was the epitome of compassion and certainly knew its definition.”

After Portsmouth, Bill matriculated at Notre Dame followed by additional research in history at Washington University in St. Louis, after which he drifted for some years. As Father Hilary once described it to me, “He was spending all his time in Maine and Palm Beach. Finally, I met him one night in New York and said, ‘You can’t go on like this. You’re wasting your life.’ And he said, ‘Why not? The one thing I really want to do I can’t.’ And I said, ‘What’s that?’

Faculty Member and Friend

In our day at Portsmouth, Crimmins was a stylish lay master in his late 30s, who wore a Pierre Cardin doublebreasted blazer over his turtleneck (eschewing the neck ties that were de rigeur for other faculty and students), taught ancient history and coached the middler football team. Crimmins had a pair of navy-blue Camaros and enjoyed racing whichever of them he was piloting down the long School driveway a few minutes late to his history classes.

Sports were primitive at the Priory in those days. We practiced football on a severely sloping sheep meadow and basketball in the ancient carriage house of the original estate. Lad, Father Hilary’s sheep dog, would occasionally run loose and come down to herd us up into a circle. At the end of an undistinguished season Crimmins threw a party for us at his spacious house on Indian Avenue overlooking the Sakonnet River in Middletown. Students loved him for the generosity of his spirit and his slightly mad nature. In his living room hung a quotation from Love’s Labour’s Lost:

There is a gift that I have, simple, simple; A foolish extravagant spirit full of forms, Figures, shares, objects, ideas, Apprehensions, motions, revolutions: These are begot in the ventricle of memory, And delivered upon the mellowing of occasion. But the gift is good in those whom it is acute, And I am thankful for it.

But Crimmins was crazy like a fox, and often figured out what we were thinking before we had put it into words ourselves.

Bill Crimmins taught ancient history exuberantly and enjoyed elucidating the difference between the Spartan concept of “Severitas” (imposed from without) and the Athenian virtue of “Disciplina” (cultivated from within). His course in Medieval History was more highspirited, focusing on battles from Constantine’s victory at the Milvian Bridge in 312 through the Crusades to the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Crimmins also covered the rise of the religious orders and the growth and schisms of the Medieval Church; but with his own in-

nate humanism he would point out that the Council of pre-game training meal that day. His assistant, Happy Trent (1570) had declared: “Whoever does what within Boniface, looked stunned and drawn. Unusually, Bill him lies, God will not deny the necessities of salvation.” Crimmins was on hand as well, and after we had eaten His excitement with History’s sweep was infectious and he stood up to speak. along the way “Uncle Billy” gave bonus points for victories in athletics, which in our first year was problematic, “Coach Coen was looking forward to this game, but since we had a defeated two-game season in football. In he can’t be here today.” Crimmins took a deep breath. the last game Coach Crimmins stood on the sideline “Coach Coen’s daughter was killed in a car crash last saying, “Just one victory will save the whole season.” night. He has requested that the game go forward, wants As the long afternoon waned Crimmins shifted to, “Just you to know he will be thinking of you, and asks that one score…” Finally, he pleaded, “Just one sustained you go out and play the best game you can. Let’s stand drive….” It was not to be, but and say a prayer for Karen and all the Coen family.” he never gave up hope. Nor did he ever hesitate to interrupt a It was Father Hilary who once We did go out, and with “Uncle Billy” as our bulwark on the practice or lecture when he saw described Bill as “the most personally sideline, battled a much bigger a student daydreaming. “Mac- generous man I have ever known,” team to a standstill in the first Guire! Are we thinking about football? Or is it Alice again?” but then, with Gallic exasperation, half. St. George’s scored the first touchdown of the game after We thought he had an uncanny could not resist adding, “But he’s got a long drive late in the third ability to read minds. this Irish sense of time, and life just quarter. Our break came when To help get through the endless winter term Bill started a doesn’t work that way.” Bryan McShane ’71 forced a St. George’s fumble and recovered Sunday afternoon film club in it at midfield with two minutes the old Science Lecture Hall, he encouraged us to can- left. Mike Mooney ’70 threw for two quick first downs, vass for Eugene McCarthy in the 1968 primary election, and then we ran twice unproductively up the middle. and to participate in community service programs in On third down at the twenty Mooney faked into the Newport. Along the way he performed countless acts of line and rolled out right. He found his flanker streaking charity with effortless elan. (When, for example, Law- for the end zone and threw a perfect spiral that hung rence Doyle ’71 realized he had been found out imper- forever in the air. At the last instant Robbie Rudd ’71 sonating a naval officer with a stolen ID at the package split his double coverage and made a circus catch for the store in Portsmouth, he lit out across the muddy fields touchdown. On the extra point we faked the kick and back to Cory’s Lane ahead of the police and called Bill Mooney rolled out right again. Rudd again found dayfrom The New, saying he was sure Father Philip would light, caught the ball and clutched it close. We were up find his muddy clothes and kick him out for having been 8-7, and fifty seconds later had hung on to win, our first AWOL. Bill immediately got into his car and came to victory over St. George’s in seventeen years. campus to collect Larry’s bundle, and by room inspec- After the game the St. George’s captain, Tom Campbell, tion the next morning the clothes were neatly laundered came into our changing room, shook our hands and and ironed back in his room.) said, “We hated to lose, but after we heard the news, if After serving as our middler football coach Bill reveled it had to happen, we’re glad it was today.” After Campin our progress in later years and played a critical role bell left, at Bill Crimmins’s suggestion, we knelt to pray in our 1969 championship year and its upset victory again. The following Monday Father Damian and “Uncle over St. George’s late in the season. I knew something Billy” drove us in the beat-up bus of that era, the “Red was wrong when Coach Coen did not appear for the Baron,” to Karen Coen’s funeral.

Along with Father Andrew, Bill was especially close to Father Hilary Martin and during a free period could often be found conversing over coffee or, before lunch, even a sherry in Hilary’s art-appointed St. Bede’s rooms. They shared a love for art, architecture, and European civilization, so much so that Bill sometimes accompanied Hilary and his graduating Sixth Form boys’ Arts & Civilization summer tours to the Continent.

It was Father Hilary who once described Bill as “the most personally generous man I have ever known,” but then, with Gallic exasperation, could not resist adding, “But he’s got this Irish sense of time, and life just doesn’t work that way.” And yet it worked that way for Bill, and those on whom he lavished his infinitely patient and generous attention.

In January of 1981 I attended Father Hilary’s funeral Mass with Bill in the Abbey church. At the consecration, incense surrounded the altar and spiraled upward in slow swirls into the spun-gold wire sculpture of The Trinity by Richard Lippold. Afterwards, in the monastic cemetery, black-cassocked and cowled monks chanted the last prayers over snow-covered ground. I was reminded by these two images of the verse we often sang at Sunday Mass: “Sprinkle me O Lord with hyssop, and I will be purified. Wash me and I will be whiter than snow.” The reading which came into Bill Crimmins’s mind was far more apposite: “I have loved, O Lord, the beauty of Thy house, and the place wherein Thy glory dwelleth.”

As “Uncle Billy” enters his 92nd year, the William A. Crimmins ’48 Scholarship Fund in Arts, Athletics and Civilization will serve as the most fitting link imaginable between the founding and development of Portsmouth Priory, some of its most memorable monks, and the bright future of Portsmouth Abbey School, enabling worthy young men and women to gain a first class education, personified by a beloved schoolmaster, coach, and philanthropist of rare learning and infinite time, kindness, concern and, yes, compassion for others. Bill Crimmins’s generosity has been legendary. Here are a few examples:

v He gave the double-faced cross above the altar in the church in memory of his two brothers killed in WWII;

v When the church organ broke, Bill paid for a new organ out of his own pocket;

v When in the 1960s Father Hilary told then-Headmaster, Father Leo van Winkle, he had to cut the science building further and Leo told Bill he couldn’t make it any smaller, Bill said he would fund the stone walls, thus preserving the building size Fr. Leo needed;

v Bill paid tuition for students in need. Many students who were in academic or other trouble were also supported by Bill with active intervention on their behalf to keep them in the school.

v In addition to his work and philanthropy on behalf of the School, Bill has also been active and generous in Newport, co-founding the Newport

Music Festival with Katherine Warren and Ann Kinsolving, sponsoring the groundbreaking Monumenta con- temporary sculpture show, producing a movie shot on Aquidneck Island and shown at the Cannes Film Festival, as well as supporting myriad local institutions such as the Newport Art Museum and Redwood Library and Athenaeum.