by Ivy Rockmore

Illustrated by Ella Buchanan

“No marriage ‘till you’re 30.”

These words have been ingrained in me since the day I turned eight. I had just immigrated to the U.S., and my parents sat me down to tell me the three rules that would define my adolescence.

First: no piercings or tattoos. (Some Jewish cemeteries prohibit the burial of people with tattoos, a practice that emerged after the Holocaust. My grave plot is already purchased, waiting for me in Canada.)

Second: marry another Jewish person. Their gender or sexuality does not matter, as long as they're Jewish. (My parents became more lenient on this one as time passed, but the principle still stood. For hundreds of years, my ancestors only procreated with Jews, and I was expected to do the same. According to a DNA test, I am 99.9% Ashkenazi Jewish. The rule derived from something my great-grandfather told my grandmother—to build a house, you need a strong foundation. For my family, that foundation was our shared history and Jewish heritage.)

And third: no marriage until 30, along with a requisite history of two or three long-term relationships before settling down. (If I were to ask for their blessing to marry my first love, the answer would be no.)

Their rationale made sense to me. The brain is not fully developed until age 25. Many of my parents’ friends who married young ended up divorced. In fact, divorce rates are higher for couples who marry between the ages of 20 and 25, with around 60% of those marriages failing. It’s unclear whether this is due to immaturity, financial instability, or something else—or if couples who marry

Dear Readers,

For the past few months, I’ve been in a state of limbo. Though it doesn’t quite compare to Dante’s descriptions of souls looming around verdant meadows for all of eternity, I imagine the number of sighs and days melding into one another is not so different. After spending all summer stating my life’s purpose under different character count restrictions, I must now simply wait for Big Med School to determine my fate. While much of this waiting has consisted of neurotically checking my email and online forums for updates, it has also provided me with something I’d long been coveting: time. To read books I enjoy, to walk around in the crisp autumn air, to say yes to spontaneous plans, to call my parents, to care for my friends. To mull over my future, yes, but also to appreciate the blessing of having any time at all.

This week in post-, our writers are also dedicating

later are simply more cautious about divorce due to age, fear of finding a new partner, or social judgment.

Why, then, I wondered, did Americans rush to marry so young? In the South, there was a weight in the air, thick with the expectation to find your high school sweetheart, to pin down “the one” before the ink on your youth was even dry. Despite all the statistics, people still leaped into it. My Jewish-Canadian identity taught me that timing is everything; you need to be older and more mature to be sure of what you want. But down South, it wasn’t about certainty—it was about proving to the world that you had it all figured out, that you could beat the odds in a country that worshiped the illusion of self-made perfection. And so, I never quite understood that rush, never quite understood the pull to marry young, because I never understood the culture in the first place.

My parents’ love story, however, was as clear as midnight starlight on still water.

Picture this: my father, lean, sharp blue eyes, and too intelligent for his own good. At 21, he was tanned and full of himself. He was sitting in a dimly lit bar with framed posters of The Godfather on the wall, staring into the winedark eyes of a girl who would later become my mother. She sported a ’70s trench coat, for it was winter in Toronto, and a chic tulle skirt that covered her knees. Her hair curly and makeup smudged, she found herself bored by their conversation. As she sipped her appletini, she realized she was not impressed by his so-called “Rico Suave” shtick. He was too cocky. Politely, she made an excuse about needing to tend to a friend, left early, and decided that Michael was a “no.”

time for reflection. In Feature, Ivy shares her experiences with dating as a trans woman and how they relate to the tenets of marriage instilled in her by her family. In Narrative, Helen digs deep into how her relationship with self-image, food, and her culture have influenced one another and evolved over the years. Meanwhile, Pooja’s piece shares with us a series of quotes—and the stories behind them— that have motivated her through difficult times. In Arts & Culture, Zoe writes an ode to Faye Webster and discusses how her creative autonomy and passion for music shine through in each project. In the other piece, Ellie analyzes a print of Edo and delves into the paradoxical portrayal of urban alienation. As for Lifestyle, writers Jedidiah and Ishan respectively encourage readers to step outside their comfort zone and take initiative to make Brown feel like home. In post-pourri, Michelle gets us into the fall spirit as she defends the season through its classic tropes. And to

A decade passed, and they finally met again for a meal. He’d changed. Not only was he kind and personable now, but he genuinely cared—and, thankfully, his frat boy days were behind him. He had a stable job, too. As my mother caught the twinkle in his aquamarine eyes, she felt herself blush. He would make a good husband, she thought. A good father, too. (He sure did.)

Within six months, she was walking down the aisle. I listened to my mother tell me this story until I internalized it as much as her American phone number or our new address in Dallas. She had my brother and I repeat each detail 10 times over, and then 10 times again, until it rolled off our tongues like a cold breath on a Canadian morning—or perhaps, like phlegm.

The next three years went by quickly. Suddenly, I was 11 and insecure in my body, my gender, and this new place I called home. I was at a sleepover at my then-best friend’s house, and we were sharing his twin bed. He was the kind of born-and-raised Texan who took me to his grandfather’s ranch and begged his mom for late-night “hubchubs” from Whataburger. We couldn’t have been raised more differently, but I loved him the same.

On nights like these, we would typically eat something you’re not supposed to have for dinner, like donuts. Then, we’d attempt to name all the countries in the world by memory and count all the stars on his ceiling tapestry, until our eyes grew sore and our bodies caved to exhaustion. But tonight was different.

“When do you wanna get married?” he asked

round out the issue, check out our crossword as it takes a fun twist on alphabet soup.

Despite being suspended in limbo, taking time to relish the experiences that bring me joy has made me that much more resilient in the face of uncertainty. Who would’ve thought that I would be learning the most about myself when I’m least certain of where I’ll be a year from now? All of this to say, dearest Readers, cherish any and all time you have. Whether it be your commute to class, the burrito bowl line at Andrews, or the queue in the mail room, good things come to those who wait—or so they say. And if you’re still unconvinced about the hidden benefits of waiting, pick up a copy of this week’s issue of post- to make the wait worth your while.

Taking it one day at a time,

earnestly, his head tilted toward me.

I stared up at the ceiling, avoiding his piercing gaze. “30,” I said, my Adam’s apple bobbing as I swallowed saliva.

“30?! That’s so far away!” His body shifted closer to me as he turned on his side. He curled into himself, scratching his neck. “My parents got married right after college, and, dude, they’re so in love. I want that, you know? And I want it quick, while I’m still young.”

He looked at me for too long, and I thought his crooked smile gave him away. But I was fed up with his naiveté. Headstrong and voice clear, I reprimanded his thinking.

“Look, I get that. But you don’t know where you’re going to be in a year for middle school, let alone five, 10, or 20 years. People change, especially when they’re young. Also, my mom says that love is chemical, and relationships are work. They’re not sustained by attraction, but commitment.” (He could barely get his times tables done in math class; I doubted his readiness for a genuine romantic commitment.)

“But worst of all,” I continued, “even if you do commit, it won’t last. All of my parents’ friends got married too young, and they ended up sad, separated, and divorced. You don’t want that for yourself, do you?” I was panting as I finished my spiel, my heart rate catching up to the speed of my breath. When I turned to him, his eyes were wide and glossy with tears.

“You know, you can be a real mood-killer sometimes,” he whispered, his lips trembling. He turned away from me and moved toward the wall, pulling the shared cotton blanket with him and leaving the cold air to envelop my legs.

I had hurt him—this I understood. I stared up in silence at the ceiling, trying to count the stars until I could drift to sleep and forget this interaction. But I couldn’t. I stayed awake for hours, feeling awful for how sad I made him. Yet, at the same time, I strangely felt proud of myself, because I knew I had stayed true to myself and my family. In a part of the country where my cultural values were seen as especially foreign and obsequious, this was my one chance to establish myself as normal, mature, and worthy. I had proved to this American, Texas-born boy with shaggy hair that life wasn’t going to be so easy. I had stuck with my Jewish-Canadian upbringing and rebelled against American concepts of “the one.” I was an interloper and an outsider in his world, but I was my mother’s child all the same.

Nine years have passed. The leaves are falling, turning a tepid orange. I am 20, eating scrambled eggs and crispy hash browns at the V-Dub dining hall at Brown, and I’m a girl now, too. It has been five years since my childhood best friend’s parents got divorced.

Across from me is a guy friend who I asked to get breakfast with—something casual, so I could get to know him better and see if we might be a match. We chatted about the things you’re supposed to: how classes are going, what movies we enjoy, how nervous we are for the

upcoming presidential election. And then came the things you’re not supposed to bring up so early—if we’re happy at school, where we see our lives going.

That night, I called my mom to tell her how it went. My eyes lit up as I debriefed the coffee date over FaceTime— me in Providence, her in Dallas, over 1,740 miles apart. She nodded along as I recounted the details, but then stopped me.

“Honey,” she cooed. “Why did you even ask him out in the first place?”

“What do you mean?” I asked, biting my inner cheek. “Well…he’s 19, you’re 20. You’re just too young. You know, I didn’t have my first boyfriend until I was 22. 22! What’s the rush? You’ve got so much time. And he must be immature. Boys always take longer to catch up. Does he know you’re trans?”

I groaned. “Yes, mom. We’re friends.”

“Ok, good.” She nodded approvingly.

“I asked him out because I wanted to see if we’re a match. That’s all it really is. And mom, I’m not looking for anything serious,” I reassured her. “But I still want a relationship at some point in college. Besides, I’ve got to have three real relationships before I settle down. That’s the rule. So I want to stay on track and start exploring now.” I felt good about my explanation. “Plus,” I smiled, my gums showing, “he’s Jewish.”

She chuckled, making eye contact across the screen. On her lap was Olive, our 13-year-old Shih Tzu who I missed deeply. And then my mother’s expression darkened, as a new thought crept upon her.

“Pickle…” she mumbled. Pickle was what she called me when she wanted to comfort me, to remind me that she loved me.

“What?” I asked, a nervous edge creeping into my voice.

“That rule you mentioned. That doesn’t…apply to you, not anymore. Not after you transitioned.”

“Oh.” My expression grew somber. I gazed out the window of my dorm. The sky was a deep navy, verging on pitch black, and outside, crickets serenaded the night in full bloom.

I understood what she meant. For three years, I had bemoaned the struggles of dating while trans to her.

For one, the proportion of the population who would be open to the idea is slim (roughly 5%). Though Gen Z attitudes are more progressive than older generations, many are still apprehensive. Second, being trans carries emotional burdens that can be difficult for partners to navigate, especially if they’re unfamiliar with the trans experience. Third, romantic partners have to be comfortable with their sexuality—whatever that may be— and unashamed to be publicly with a trans person. While the latter should be the standard, the former is harder to ask of college students just finding their place in the world. Fourth, I am what is problematically dubbed “cis-passing,” meaning someone probably couldn’t clock me as trans

6. Extraterrestrial if you don’t know how to spell

7. My great grandpa

8. The one who is friends with Edd n Eddy

9. Page Board 10. -ward Cullen

unless I disclose it. (The term is considered problematic because it purports an artificiality to my womanhood. Even if I “look like a woman,” the term assumes that I’m not really one, instead just “passing.”) Passing creates difficulties because I often find confusion on the faces of potential romantic interests when I tell them I’m trans, driving them away from something they aren’t ready for and couldn’t have expected.

It was clear why my mother’s supreme third rule had shifted. What hadn’t hit me, though, was the underlying assumption behind such a shift: I wouldn’t find love more than once, and that I would have been able to if I were cis.

With this, I began to feel guilty. The only thing my mom has ever wanted me to be is happy. I felt my world collapse as I realized that such happiness might become elusive, out of reach—for both her and me.

I was a rules-based child who loved nothing more than organization and structure. Yet here I was, experiencing a fundamental shift in my perception of reality. I had glorified this so-called “third rule” throughout my childhood, perhaps as a way to solidify my Jewish-Canadian identity in a part of the U.S. that was predominantly Christian and conservative. I repeated this mantra at sleepovers, dinners, even prom. It was what I knew to be fundamentally true, and what separated me from my peers who grew up in a different culture.

But now, the thing I knew to be truest was wrong, and it was wrong only for me. This thing was wrong because of who I fundamentally was. There was nothing I could do to change that.

“So what now?” I asked her.

“What now?” she replied.

In the coming days, I reflected on our conversation. At first, I felt somber, then rageful, and finally rested on content. I realized I was placing far too much pressure on a simple coffee date, especially with a friend. Relationships take time to build, and you can’t force them. If I don’t reach that magic number of three relationships before marriage, that’s surely fine. I’ll have matured anyway. Although I am certainly not dating for marriage at this age, I can still let myself look for the qualities I’d like in a potential future partner.

But more importantly—beyond the troubles of dating while trans—the person who is meant to be with me will love me for me, not in spite of me. That principle applies to everyone reading this, regardless of gender identity.

If upholding that standard means I have to wait, I will wait, because I can see my future: I’ve just turned 40, and my wrinkles are coming in. I am with someone who has matured since his time at Brown, or wherever else. We have a dog (a Shih Tzu, of course) named Eeyore, or perhaps Rooster. We’re on our balcony overlooking a lake, rippling in the sunlight. He has brought me chamomile tea and dark chocolate.

And I am happy.

“Every group has a Beyoncé and every group has a Lea Michele.”

“I’m in an American studies seminar and everyone wears docs and has septum piercings.”

by Helen Xie

Illustrated by Angelina So

TW: eating disorder

1.

Not yet tall enough to reach the kitchen counter, you are your grandmother's shadow as she prepares dinner every evening. You spend your days in your grandparents’ kitchen instead of at daycare, like the other children on your suburban street. As Grandmother kneads dough for dumplings and Grandfather hauls in pillow-sized bags of jasmine rice from the Asian supermarket, you recite rhyming Chinese lullabies and twirl in circles on the sticky vinyl floors. You mimic Grandmother's posture, as proud and straight as the oldest tree in the forest, standing on tiptoes to watch her weathered, wrinkled hands measure smooth grains of rice from a bulging sack. The grains make a “shhhhh” sound as they tumble into a metal basin. In a ritual you observe with awe, Grandmother rinses and rinses the rice with cold water until it turns the basin cloudy.

2.

Amid the din of the Hamilton Elementary School cafeteria, you crane your head from your spot at the end of the long table in an attempt to join the buzzy conversation of the popular girls. Your grandmother, in an attempt to help you fit in, now kneads dough for pizza. But the pizza is too thick, too bready, with hot dog slices instead of pepperoni. At lunch the next day, you stare enviously at the Domino’s served to your friends on cardboard trays with cartons of chocolate milk. How can you ever hope to fit in, if even your pizza stands out among the others?

3.

In the basement of Rutgers Chinese Community Christian Church, you sit on a metal folding chair next to children who are familiar and yet not your friends. You squirm, restless, and feel the backs of your thighs unstick from the cold metal. “How great is our God…” the other children intone, mouthing along to the lyrics projected on uneven white walls. But your lips are unmoving, shoulders hunched and head bent—to anyone else, it seems you are praying. In the dim light, no one sees that your eyes are squinted and your fingers are poking and prodding at the skin on your thighs. Like Grandmother kneading dough, you think. You are in fourth grade, your body already a dwelling you wish to escape.

4.

You are not allowed to eat apples with the skin intact—all those pesticides. If you want an apple as an after-school snack, you have to wait patiently by the kitchen counter and watch Father or Mother or Grandmother take the largest and shiniest apple from the bowl, scrub it furiously under a stream of water, and begin to peel. You roll your eyes as your father recites (for what seems like the thousandth time) a warning about pesticides, chemicals, and GMOs, but deep down, you know that this is how he shows his love.

Here’s how your family peels apples. Grab a knife, probably the small serrated knife sold to your family by one of those door-to-door saleswomen as part of a set. Holding the apple firmly in one hand, press the sharp edge of the knife against the skin at the top of the apple, like a surgeon making a sideways incision. Slowly turn the apple as the skin comes off like a ribbon. Once this ritual is done—the apple stripped bare, a ribbon of peel dumped unceremoniously in the metal tin your family keeps next to the sink for food scraps—cut the apple into bite-sized pieces. While your mother and grandmother know how to slice the apple so that each cube of light yellow flesh is nearly identical to the next, you know your father’s work by the mismatched, ragtag assortment of apple chunks.

5.

Polo shirts untucked from navy skirts, 10 girls crowd around a table meant for five. In front of you is a bowl of chicken noodle soup and an Italian sub wrapped snugly in clear plastic—served to you by the kind lunch lady with wrinkles around her eyes. What is in an Italian sub, you do not know—only that it is something American girls eat. You miss your mother’s home-cooked meals, itch to peek at the worn paperback hidden under the table—but those are comforts of childhood that must be left behind. In this private-school lunchroom, you can blend in. And isn’t that all a middle school girl hopes for? The days of smelly thermoses and old lunch boxes are no longer. If you wear the same clothes and eat the same food as these rich, private-school American girls, you too can be an American girl.

6.

In the basement you scrounge up a dirty mirror, propping it up in your bedroom. While doing homework, your legs move of their own accord, delivering you to your reflection, who looks you up and down. The mirror becomes your constant companion, a hypnotist luring you in. It invites you to scrutinize your complexion, your nose, your stomach, your legs, until you have collected a list of things you wish you could change.

7.

Your middle school doesn’t have a track, so your coach—also your seventh-grade science teacher—sprays uneven white lines to form a small 200-meter track on an unused grassy field. You choose track as your spring sport because Ryan, the most popular girl in your grade, is a track star and you want to be friends with her. Every day after school, you are a hamster running around in circles on that makeshift track—arms pumping, sneakers squishing into the overgrown grass, sweat soaking the gray Far Hills Country Day School t-shirt. You begin doing ab workouts on a purple yoga mat your mother buys you from Walmart, obediently copying the movements of models on YouTube who promise you six-packs like theirs. In the locker room before track practice one day, you are changing into your sports bra (you don’t need one), when you overhear Ryan and the other girls debating over who the skinniest girl in the 7th grade is. When Ryan mentions your name, you turn away, hiding your smile in the cotton of your smelly gym shirt.

8.

High school is a season that shepherds in change. You begin to eat apples with the skin intact—forgoing the tradition of watching a loved one peel away skin and carefully slice it into pieces. Other changes: orange patches caked over red pimples, courtesy of a tube of heavy-duty concealer from Sephora; fewer Skype calls with your grandparents, who can no longer make the 13-hour flight to the US; googling restaurant menus beforehand to ascertain the healthiest option. You scoop out smaller and smaller portions of sticky jasmine rice at dinner every night, and watch your reflection in the mirror shrink too, until rice becomes as foreign a food to you as your American classmates. At night, your stomach growls at you, angry at this lessening, but you ignore it.

9. Your senior year of high school is consumed by discipline. Every morning, you lace up your running shoes before the sun rises, hitting the pavement for a few miles. The thud of your feet on the concrete is a rhythm you depend on. The early morning fog and the biting cold feel like penance for the body you’re determined to change. You’ve cut out carbs entirely, trading family meals of rice and noodle soup for fruits and vegetables that never seem to fill your stomach. The vibrant flavors of your grandmother’s cooking are now distant memories, replaced by bland, calculated meals. But it’s working— you’re getting thinner, and you’re getting faster. Each run feels like victory, and each rib you count in the mirror fuels your drive. It's no longer about health or fitness; it’s about control. You’re not just training for cross-country races anymore—you’re in a battle with your own body, one that you can’t afford to lose.

10.

It’s the summer after your sophomore year of college when your period vanishes completely, and instead of panic, you feel a strange sense of relief. To you, it’s a sign that you’ve finally gotten it right—that all the carb-cutting, the endless miles, and the calorie restriction have brought you to the perfect balance. No period means you’re lean enough, disciplined enough. You never seek a doctor’s help, brushing off the warnings you’ve read about RED-S. You convince yourself that this is just a natural consequence of being in control. How could you, of all people—so disciplined, so regimented—damage your own body? But in the back of your mind, there's a quiet voice—one you refuse to listen to—hinting that this might be too much. The fatigue, the constant injuries, the brittle nails—they’re all pointing to the same truth: You’ve pushed your body too far, and now it’s pushing back.

11.

The breaking point comes during what’s supposed to be a routine run. You’ve mapped this route so many times you could do it blindfolded, but today, something feels off. Your legs feel like lead, your breath comes in shallow gasps, and halfway through, you’re forced to slow to a walk—a betrayal of everything you’ve trained for. You bend over, hands on your knees, fighting the dizziness, but it’s more than just physical exhaustion. As you stand there, sweat dripping down your face, it hits you: The person you’ve been chasing all this time is a stranger. You’ve spent years defining yourself by how you look, how fast you are, how “clean” you can eat. In that pursuit, you’ve lost not only your period, but pieces of your identity—your connection to family, your culture, the traditions that once filled you with warmth. You barely remember the taste of your grandmother’s dumplings or the joy of twirling in her kitchen as a child. You’ve been running toward a version of yourself that you no longer recognize, and suddenly, all the discipline and control feel hollow. Standing alone on the side of the road, you realize the real loss isn’t just your strength—it’s the person you used to be.

12.

Recovery isn’t linear. College becomes a complicated dance between old habits and new growth. You begin to reintroduce the foods you once feared, starting with small portions of rice and yaki imo sweet potato at family dinners, then dumplings, and finally the rich, flavorful dishes that had been absent from your life for so long. You rediscover the joy in cooking with your family, learning the recipes that your grandmother has passed down through generations. In the process, you reconnect with the parts of your culture you had distanced yourself from. Through storytelling, food, and community events, you rediscover the parts of yourself you had suppressed, realizing that your identity is not something to hide or reshape—it’s something to embrace. Your body, once a battleground, starts to feel like home again.

by Pooja Kalyan

Illustrated by Kaitlyn Stanton

TW: suicidal ideation

They provide me with comfort.

They inspire me to grow.

They follow me every day, in every moment.

When I hear them, they stick.

When I need motivation, they float to the front of my mind.

I can’t pinpoint the exact moment when I became obsessed with quotes, but I am now. Quotes are not bound by age, gender, or culture, and guide every person who can relate to them. The beauty of quotes is their universality.

“She believed she could, so she did.” — R.S. Grey.

I first discovered this quote when I was eight years old. My figure skating choreographer gave me a folder containing all the exercises I had learned so I could practice them independently. I flipped to the front page and there it was—the quote that would guide me through life. I didn’t know then how much that quote would mean to me as I grew older.

It continued to mean more to me

The older I got.

Through the ups and downs, the falls And failures.

I found more than just inspiration in: “She believed she could, so she did.” I found comfort, a soothing balm for the soul in times of uncertainty and doubt.

It meant more than simply coming back after a fall. It meant persevering through life, forgiving a slash on my calf despite no apology, moving forward after a bad exam, or continuing on even after considering leaving life.

It means I will always be there for myself, no matter what happens. I will show up every day and let go of the negativity that others have. Whether it's toxicity, jealousy, or the hate thrown my way, they motivate me to strive for improvement.

"I can. I will. I did." — Me.

This quote also guides my life. It always works.

I remember being afraid to try my double axel jump after not having done it for over a year. I was at Meehan Auditorium, circling and circling, my way of “popping” or pulling out of a jump, depending on how familiar you are with skating terminology. I kept going in “Circles,” as Post Malone sings, and ironically, that was playing at one

point during my circles.

WhatamIdoing?I ask myself. Comeon,doit.JUST DOIT.Nike, Nike, Victory.

Nothing worked.

I thought back to what I told myself in Tulsa, California, Chicago, Colorado, and especially in Arkansas—when I was away from my primary coaches. When I was at home working with my favorite coaches, they weren’t as experienced in teaching triple jumps.

I CAN, I WILL, I DID.

Double Axel—Landed!

This is my process. What goes “round and round” in my head.

Then came the quote that guided me throughout the 2021 Nationals in Las Vegas. This was my first time doing a complete short and long program at the Championship Senior Level. I had to withdraw in 2019, and I didn’t qualify in 2020. This was my second chance. I wanted it to be better. In a way, it was my first chance. It was good luck to be in Vegas.

“The sky has no limits. Neither should you.” — Usain Bolt: the GOAT, the LEGEND.

Someone I’ve always wanted to meet.

Faster than a cheetah.

That’s him.

That's who I want to be.

I found solace in this quote. I realized there was no problem, no harm, in aiming high. It's no problem to daydream or wish for a dream to manifest.

I’m not sure what to think about this quote, though it’s been lingering in my mind for a while.

Should I doubt myself? Ido.

Should I limit myself? Itrynotto.

Should I reach for the stars? To space? That’swhat Ido.

I want to embody the quotes that occupy my mind. I write them down. Over and over and over again.

In my bullet journal, I color the words according to the rainbow, trace them in gold, cut up magazines, and rearrange them to spell them out.

I say them over and over again,

Until I can’t know them any longer.

They fill my head like clouds on an overcast day, like sunbeams in the summer.

“Oh, the places you’ll go kid.”

“I’m not superstitious, just a little stitious.”

“Karma is my best friend.”

I love the feeling of living up to my quotes.

To never “stop believin’.”

These quotes make up much of who I am.

A forever dreamer, Pooja

“Is

it’s all Clairo this, Clairo that, no shade

by Zoe Park

Illustrated by Lesa Jae

Faye Webster’s latest album stayed true to its title. UnderdressedattheSymphony did not quite meet the 2024 standard of new indie albums. However, with her ongoing live performances, Yo-Yo Invitational, and recent singles, Webster is reminding people of her relevance and flair. While her current shenanigans may feel like Webster is finally becoming her own person, in reality, she’s always been like this.

Let’s take a step back: The year is 2013, and it’s nearly Halloween. Webster releases her first album. The record, Run and Tell , is distinct from her current work and serves as a memento of her Southern upbringing. While she cites Atlanta as her musical inspiration on all her albums and features the pedal steel, a specific type of guitar, to this day, Run and Tell’s sound is definitely Southern, especially in comparison to her later work. Her vocals on songs like “Sweet Lad” and “Mama Stay” have much more of a country folk twang. I love those songs and the rest of Run and Tell because of this, but Webster has expressed a degree of dissatisfaction with the record. In an interview with American Songwriter, she stated: “I wish I didn’t put out my own record when I was 16. But, I think that’s just an ‘artist’s perspective on their own work’ kind of thing. Overall, I’m very grateful, because, obviously, I wouldn’t be the same person or doing the same stuff if I hadn’t done all of that first.”

After Run and Tell , Webster attended college in Nashville for a semester, before returning home to Atlanta to continue producing music. She left Tennessee because of its stagnancy and the feeling that everyone was making the same music as each other. On the other hand, Atlanta was unapologetic in its sound diversity— everyone did their own thing. Not only was Atlanta a more inspiring city, but she also found community at Awful Records. She was introduced to Awful by longtime friend Ethereal, and started working with them as a photographer. She composed the perfect shots of artists, including middle school friend Lil Yachty, while still writing songs in her own time. Eventually, she signed with Awful, despite the label almost exclusively representing rappers and R&B artists, including Father and formerly, Playboi Carti. The only record she released with Awful was her self-titled album. This time in her career was the first of many instances when Webster simply knew what she wanted and just did it.

What is refreshing about Faye Webster is her continuous creative autonomy. At Awful, she was just making music and art with her friends. Her success comes from her passion for every project. Even after switching labels a few years ago, she still does what she wants, both as a creative director and musical artist. Take Atlanta MillionairesClub . More often than not, when I mention this album, people say, “Oh, is that the one with the really disgusting cover?” Yes, it is the one with chocolate coins oozing out of her hands, residue smothering her lips, and eyes affixed in a trance. It’s honestly one of my favorite covers because of how off-putting it is. It is not the most savory image, but who said it had to be? Despite the contentious cover, AtlantaMillionairesClubis filled with hit songs such as “Kingston” and “Right Side of My Neck” — this is the album that made her famous. The sound is quintessential Faye Webster, like no other

out there. Part of what makes her unique is the frequency of the pedal steel, which is most commonly found nowadays in country music. However, even with the pedal steel and songs about longing, her music is far from country.

While Faye Webster could be successful in her production alone, she is known for her intimate yet silly lyricism. In UnderdressedattheSymphony , her favorite track (according to her Instagram) is “Feeling Good Today.” The song is over-autotuned and the best verse is: “I might open my doors / I got a exterminator / So it doesn't matter if bugs come in / That way my dog goes outside / My neighbors know his name / Thought that was weird, but I'm over it.” There is nothing groundbreaking about how she thought it was weird her neighbors knew her dog’s name, but it is a relatable inner monologue. She also reveals so much about one sliver of a moment, but that is it—a single moment. The ephemerality of her lyrics creates an illusion for listeners. We feel connected with Webster, but the moment is zoomed in and blurry, and ultimately, we are not a part of it. Despite writing songs that I assume are semi-autobiographical, she shares solely her emotions and maintains her privacy.

The same can be seen in her most recent single, “After the First Kiss.” The song is a glimpse at a whirlwind of a future. One single kiss, and Webster knows this person is her wife and makes plans to meet her mom, yet she does not even know her last name. There are many details that frame the narrative without giving very much away. Many listeners on the internet suspect the song is about Webster’s girlfriend and singer, Deb Never—an inference based on the music video for the same song, which features Live Action Role Playing (LARP). In what appears to be a field behind the local Safeway, the video takes place during a battle of LARPers, with Webster in green warlock prosthetics and Deb Never in fantastic prosthetics as well. By the end, they are the two sole survivors, and they kiss. While the video was directed by frequent creative partner, Kyle Ng, this video could not be any more Faye Webster. While LARP as a term might be quasi-mainstream, the activity itself is not. No studio executive could have thought of this concept, not even an indie one. I suspect Webster is genuinely interested in LARPing and wants to explore it on set.

My favorite fun fact about Webster is her love for yo-yos. It is unclear when she started yo-yoing, or how or why, but she certainly is not shy about her passion. She has released multiple yo-yos and recently hosted the first Faye Webster Yo-Yo Invitational. The event took place amidst a slough of seven straight tour dates on her and her team's ‘day off.’ She has multiple music videos on her social media that feature her yo-yo skills. Her authenticity and commitment are beyond endearing,

especially in the age of PR gimmicks and clickbait. Seeing public figures who care about what they do makes me appreciate their work so much more. In addition to yoyos, Webster also loves minions. While it is hard to find someone who doesn’t like minions, who can say that they collaborated with Illumination Entertainment on their Coachella set to minionize themself, and then started every subsequent show on tour with the animation? Faye Webster can.

While we probably can’t expect another album soon, Faye Webster is far from irrelevant. Pulling from her love of Atlanta, yo-yos, and minions, her antics are unpredictable, yet delightful. While she has evolved as a musician over the years, her music remains truthful to who she is. Faye Webster has built a world that is cohesive in its eclectic and candid nature, the traits that make her an indie darling.

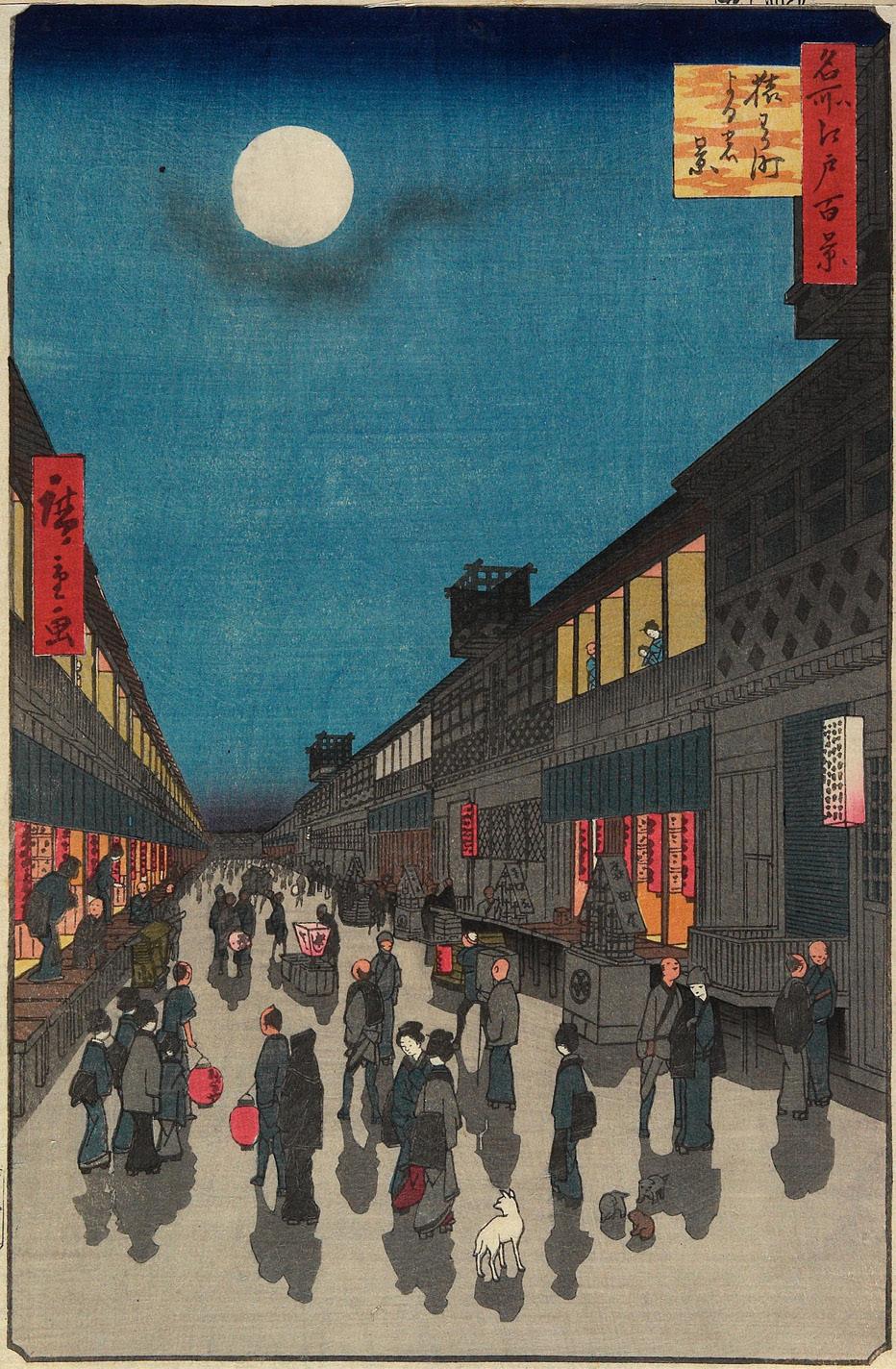

urban

alienation as viewed through Hiroshige’s Night View

of Saruwaka-machi

by Ellie Kang Illustrated by Fiona McGill

Ukiyo-e (“Pictures of the Floating World”), a genre of Japanese art focusing on the portrayal of ukiyo (“The Floating World”), flourished from the 17th through the 19th century. During the Edo period (1603-1868), the economy in Japan boomed and the country was unified under the strict control of the Tokugawa Shogunate. This brought prosperity to an emerging merchant class and allowed the arts and culture to flourish as people had more time for leisure and entertainment.

The bustling city, a prevalent theme in Hinohara Kenji’s AnIntroductiontoUkiyo-e, details life in the newly urbanized city of Edo (modern-day Tokyo), where great masters produced works to commemorate the 18th century’s largest city and its new social patterns. A major sub-theme of the bustling city was famous places in Edo with artworks featuring bridges, key points in the city’s transportation network, popular temples and shrines, and the Yoshiwara officially-licensed pleasure quarter. Another subcategory of entertainment was kabuki, a popular form of theater and one of the greatest delights of the commoners, or heimin. Additionally, sumo emerged as a popular spectator sport.

Despite all these activities and the mass migration from rural communities to Edo, alienation and isolation remained pervasive, exacerbated by Japan being closed off to the rest of the world. Loneliness became more prominent in the city. Great masters like Hiroshige managed to portray this paradoxical theme of urban alienation during the prime years of ukiyo-e Hiroshige’s woodblock print Night View of Saruwaka-machi, part of the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, illustrates the new theater district of Saruwaka-machi, or Saruwaka Street, named after Saruwaka Kanzaburo, the founder of Edo kabuki theater in the Nakamura Theater over 200 years earlier.

In this scene, teahouses line the east side of the street on the left of the print, as well as puppet theaters further in the background. On the right side are the three main kabuki theaters licensed by the government, arranged in order of seniority. The theaters are identified through the boxed turrets called yagura projected above the eaves of the buildings, indicating government approval. Typically during the theater season, the fronts of the buildings are covered with signs and banners, and the streets are packed with people as they file in and out. However, this scene features a much quieter and detached autumn atmosphere.

Typical scenes of the city show the chaos of a rush hour, simultaneously implying a network of deeply-connected social relations. However, the city’s dynamic in Hiroshige’s print seems much more distant and subdued in a mysterious and dangerous atmosphere.

Upon closer inspection into the people populating this scene, the figures are mostly turned away from each other with downcast expressions and little interaction. Even those walking together or in close proximity, like the two women in the center, are turned in opposite directions. This could portray ideas of timidness and modesty, but it could also reflect the sad and lonely atmosphere sensed through the print. It reveals urban isolation—disconnection despite the dense population. The only visible interaction, between waitresses and their guests from the veranda, implies that relationships in the city are limited to business, lacking deeper connections. The lack of facial details on most of the figures reflects a sense of anonymity that creates more lonely souls lost in the sea of the urban fabric.

This print shows a serene night-view landscape. However, the most prominent features of it are the

full moon that rises high in the deep autumn sky and the array of shadows cast by the figures. The moon, a subject for depicting seasonal beauty and evoking home, acts in concert with the shadows to add a more eerie effect that suggests the coldness of being alone in the city. The relative darkness of the kabuki theaters paired with the shadows give the print a hauntingly quiet impression in juxtaposition with the typical bustling atmosphere of Saruwaka Street. The shadows, rarely used in ukiyo-e, create a haunting atmosphere and suggest the influence of Western art on Japan, particularly through the use of perspective and depth. However, for both Western viewers accustomed to seeing shadows in art and for Edo viewers to whom shadows are a curiosity, this print still has the similar effect of creating an otherworldly, almost mystical atmosphere.

This print, created in 1856, also reflects the socialhistorical context of Japan during the final years of its isolation. After the Shimabara Rebellion in 1637, Japan remained closed to the West for over 200 years, fostering a period of peace and cultural flourishing. Although Japan's isolation officially ended in 1853 with Commodore Matthew Perry's arrival, significant societal changes didn't occur until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. Despite the print’s crowded space, the disconnected figures symbolize Japan's detachment from the rapidly globalizing world. After two centuries of insularity, this disconnection within the population is captured in the subdued and detached crowd scene Hiroshige portrays in one of the most striking pieces in his series.

there’s so much more outside of it

by JedidIah Davis

Illustrated by Candace Park

In typical unfortunate October fashion, I’m inundated with due dates and midterms and fighting to keep my head above water. Recently, I washed up on the third floor of List after midnight, sleepily typing out an email to my professor—the studio door was locked, dashing hopes of meeting yet another deadline. With mild dread for the next day, I was ready to leave when another student, a fellow stranger also on a late-night cramming mission, came up to me with a request that would leave me glad to have been stuck helpless at List that night.

As we dive further into fall semester, I’m sure many of you find yourselves settling into a steady routine. Perhaps you’re still diligently waking up for your 9 a.m., or rather, utilizing Lecture Capture to prioritize sleep (both respectable in my eyes). Maybe you faithfully trek up to Andrews from south campus each weekend for a hearty burrito bowl, no matter how long the line may be when you arrive. Or, possibly, you hunker down most nights in your library of choice for a much needed lock-in session.

Whatever your campus routine, I’m sure it also comes with its own catalog of familiar faces— your closest friends, acquaintances, smile-andwaves, the opp or two (or more!). It’s my senior year at Brown, and, as is par for the course, I’ve been reminiscing about that incomparable feeling of being a first-year, staring down the countless possibilities awaiting me. This is not to say I’ve discovered everything there is to find at Brown— far from it. But no matter your year, falling into a routine can also mean falling out of that college life honeymoon phase. My first year here, I remember impulsively accepting lunch invites with strangers, taking my first sip of vodka (its harsh burn has never grown kinder), hopping on the train for a weekend getaway, stretching myself thin with classes and commitments, and feeling the rush of novelty every single day. But in the years since, I’ve felt a shift, where first encounters have become rare and weekend adventures are fewer and farther in between. There is much comfort and security to be found in a weekly regimen, but I’ve forgotten what it feels like to regularly engage with the unknown. The ringing of the hourly University Hall bells remind me of where I should go next but also of all the places I could otherwise be. There was an era when I’d jump at an opportunity to go outside my comfort zone, with a carefree “Why not?” Now I ask myself, “Why did I stop?” ***

“Can you help me get this lock open?” My late-night List companion—let’s call him Ami— pointed to a padlocked cabinet, his project tucked away inside. What are the odds that both of us would find ourselves on this same floor, at the same time, with the same problem? Apparently, not that unlikely, according to a VISA-concentrator friend of mine. As we took turns futilely rattling the lock, the tried and tired first rounds of conversation began: “What year are you?” “What’s your concentration?” We’ve all been there.

Finally, the lock relented, and Ami held his poster in his hands. There. Mission complete.

I’m relieved of duty and free to walk away with a superficial “Nice meeting you!”

Right?

It would have been smarter to leave, to spend the dwindling hours before my alarm blared sleeping or catching up on work. But something held my feet in that studio and compelled me to pull up a seat as Ami prepped his poster paper. Within moments, guarded conversation melted away to an unexpected heart-to-heart under the cover of night and stark studio lights. We bonded over the complexities and existential pressures of being low-income students at an Ivy League school and the struggle of reconciliation with cultural and ancestral pain. We even talked about our grandmothers.

An image comes to my mind of friends chatting beneath a blanket tent at a sleepover, their huddled silhouettes lit up by lamplight. There’s nothing like a nighttime exchange with a stranger to remind you that you’re never alone. The night’s backdrop allows us to open up to each other more easily and share the intimate facets of ourselves that we keep hidden from the daylight— the things that, arguably, most shape who we are. It feels unfair that I sometimes hesitate to bloom unabashedly, to brandish my bruises or to beget brutal vulnerability in front of friends, yet am so willing to do so with a stranger. Another of routine’s curses—that the ever-enchanting should gray into the mere everyday.

My chance meeting with Ami ended not uncommonly, with an exchange of socials and a promise to meet again, one on which I hold conviction to make good. On my walk alone down the spotlit streets, I was awash with feelings and memories that I’d steadily forgotten: that quick prick of hyper-awareness when you may have overshared with someone you just met, that steady swell of adventurous spirit when going to an asyet-undiscovered locale, that all-consuming spark when you may have found a new friend for life. I enjoy my current routine, but I sometimes yearn for those old feelings.

Routine is something I still depend on a lot. To have a steady support system, loved ones you can always go to for a laugh or rant, and that feeling that you’ve grown into a new setting, like breaking in a pair of shoes, is a wonderful thing. Still, those old feelings remind me that there is so much left to find, relish, regret, and learn outside of the regularly scheduled bubble I keep myself in. Pop it! Be brave, step outside of yourself every once in a while. When you return to the warm embrace of routine, let your eyes refresh to behold the beauty that’s before you in those steadfast friends, those familiar faces, and those usual pathways. There is always so much life to find, and I’ll do my best to always keep searching, both inside and outside my bubble. I hope you do the same.

afollow-up to f inding a home

by Ishan Khurana

On March 9, exactly seven months ago as I started writing this, I opened a Google Doc, titled it “post- lifestyle article (IK),” and began writing something which came to be called “Notes on the Possibility of Home.” The piece walked through ideas I’d collected on what it means to fit into a place: for my head to fit into my mom’s arms, or for me, a midyear transfer, to fit in at Brown. I was looking for a place to belong, not to belong to a place.

Over the course of the week, I wrote about the things I was trying to do to adjust. I wrote about missing my friends, about not having the energy to put posters up on my wall, and about immersing myself in the exploration of buildings to avoid thinking too much about the extremity of the change. I was overwhelmed and unsure.

I ended the article with the line, “Maybe home is an empty space that I’ll grow to occupy. Maybe this is right,” and the uncertainty that surrounds this statement captured my own uncertainty perfectly. Truthfully, it wasn’t something I believed at the time. It was something I was trying to convince myself of. So, I wrote towards it until I did. And until now, I had no idea just how right I was.

Today, I did pretty badly on a midterm. I walked out of Salomon, frustrated that despite feeling so prepared beforehand, I got flustered and panicked during the exam. I regretted not sleeping enough the night before, not starting to study for it earlier, losing my eraser yesterday, and many such things. Something I didn’t regret, though, is transferring. I didn’t fall into the same spiral I often found myself in last semester. Now, I’m sitting on a train, riding back from Boston towards College Hill. I just went to a concert and I sang along, loudly, without a second thought. I am realizing that, for the first time in maybe a year, I

feel like I am a part of something. I feel like this place I am returning to is a new home.

Why do I feel this comfort now, when I didn’t before? Here’s what has helped as I’ve grown into this new space:

(1) Belonging somewhere is being familiar with the people and places that define it. This may seem obvious, but it took me a while—and adjusting to countless places—to realize, so I think it’s worth mentioning. This familiarity happens with time, sure, but also with regular exposure to as much of your new place as possible. So,

(2) Take walks. During the day, see as many faces as you can, as many times as you can, so they become familiar. If you’d like, say hi to people you don’t know until you do know them.

(3) Find and fall into patterns. Something as simple as regularly getting lunch at the Ratty provides its own comfort when there’s so much external uncertainty. The backbone of my day is still the routines I established throughout last semester, and it’s nice to know where to go and what to do next.

(4) Don’t hesitate to hope for more than what’s possible. In addition to routines, remember why you started something new. This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t question your decisions—doubt can’t be avoided—but remember the very first things that you were excited about.

(5) Find beautiful moments and hold onto them. Sit outside late at night and listen to music, watch sunsets and sunrises with friends, go ice skating in downtown Providence, or whatever you think may end up changing the way you see the world. It’s impossible to know what will shape your lens—and in fact, everything does—so do what you think you will love.

(6) If anyone tells you that adjusting just takes time, do not believe them. Encourage

yourself to actively engage with your new space as much as possible. Be out there. At the same time, somewhere deep down, hold onto the fact that they are right, because they are. It does just take time.

(7) Do not blame yourself. Know that things will work out, because they have before.

Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve been thinking a lot about the first time I saw Brown. My friend showed me around the campus in the December dark, and more than anything, I remember the uncertain anxiousness hovering over everything I saw. Thinking back to each of those places brings back that uncertainty, but then a sort-of proud feeling surfaces.

I can’t believe how much I’ve grown in the ten months since I first saw this place, and in the seven months since writing the first article. I can’t believe that those same unfamiliar places now hold beautiful memories that define who I am.

When (not if) you are new to something— whether you’re a transfer, a freshman, starting a job, or anything else—remember the last time you felt this unfamiliarity. Trace back your thoughts to everything that seemed impossible to overcome, and remember yourself overcoming them, too. Remember yourself slowly growing into the space. Remember yourself belonging to it.

As this train approaches Providence, I can only think back to the first time I saw it. The street signs looked so pointed, and the road seemed so much narrower than those in Los Angeles and Minnesota. The city was preparing for winter, the small pieces of leaves on the sidewalks serving as a reminder that fall was ending, but wasn’t yet frozen. Somehow, it seems so different now. It’s remarkable how much I’ve changed and how much it hasn’t.

by Michelle Bi

Illustrated by Ellie Kang

Nowadays, the first thing I see through my window when I wake up is bright scarlet leaves adorning the tree that ripples in the breeze by Alumnae Hall. I refuse to leave my dorm without throwing on a baggy pullover or cable-knit sweater. If you encounter me anytime between the hours of 2 and 5 p.m., it’s likely that I’ll have a hot coffee from Andrews or V-Dub clasped in my hands, the liquid inside still too scorching for anything beyond sipping.

Thus is the magic of fall.

At this point, you might already want to stop reading. I’m sure this is about the thousandth piece of the season rhapsodizing over autumnal beauty. And I bet you’re tired of hearing people harp on and on about the same three features of the ‘ber months. Maybe it feels overhyped. Maybe it feels basic.

But here’s why I implore you not to give up on shamelessly and vocally loving the fall.

I firmly believe this season brings so much to appreciate. After long summers of soaring temperatures and skies so bright they make your eyes water, what’s not to love about the first tinge of autumnal chill in the air? When you step outside bundled up in a sweater, is there really anything stopping you from stepping on every leaf you encounter to try and find that perfect crunch?

Aside from the occasional downpour, the weather outside is generally and genuinely lovely. The majority of my camera roll has become simple landscape photos, my repeated attempts to capture these fleeting moments of beauty. To say it very plainly, there’s a lot to love about fall.

It’s easy to forget that in a month or so, these are the times we’ll miss.

It’s easy to complain about things like the sometimes-biting

chill in the air or the overcast clouds that darken the sky in the middle of the day. I’ve caught myself grousing about both things and more on occasion. Not everything about the season is ideal.

I’ve never experienced a New England winter, but I’ve been told over and over that the weather will only get bleaker from here on out. My friends from the area and concerned adults back home describe snowstorms, icy paths, and belowfreezing weather like war stories. Every day, the presence of the singular puffer jacket I own seems to hang heavier inside my wardrobe.

Just as we’re yearning for summer sun and skies right now, I know that these days will soon become the ones we reminisce on instead. And that realization—that in just a few short weeks, the world will grow colder than I’ve ever known it to be—continues to drive me to take a deep breath and look up at the reddening leaves every moment I step outside.

I know there will always be those who denounce this sort of fall aesthetic as “basic,” “stereotypical,” or even “uninspired.” But I believe that there’s nothing wrong in deriving pleasure from the simple things. Such is the most beautiful thing about humans: our ability to find joy in the sound of a dry leaf crunching under our boots, in the whisk of a squirrel’s tail up an oak trunk, in these brief moments that comprise this brief life.

So for these next couple months, you’ll catch me unabashedly wearing the same two knit sweaters every day, spending way too much money at the Underground, and taking every opportunity I can to stop walking, stare upwards, and say, “Look at how gorgeous that tree is!”

Because the trees really are gorgeous, and chai really is delicious, and there’s nothing quite like the feel of cool October wind slipping through your fingertips, like something alive in and of itself.

by Aj Wu

Illustrated by KAITLYN STANTON

Casual eatery What the letters in an alphabet soup might be... or a hint to 1D and 3D The artist formerly known as Facebook, Inc.

"___ the West Wind" or Keats' "___ a Nightingale"

Cheese you might serve at a FEAST It was renamed Tokyo (you'll find a hint in the post- Arts & Culture section this week!) NYC art museum 1 2 3 4 5 1 3

“After all, how do you let yourself grow roots, become entangled, when your time in a place has an end date? When you’re certain to have to leave, and don’t know where you’ll be going next, or how long you’ll stay there? It feels safer to appear and disappear unnoticed.”

Liza Kolbasov, “Haunted Grounds” 10.26.23

“So maybe magic is not reserved exclusively for the naive minds of kindergarteners. Maybe it rests most abundantly in the things unassuming and reckless and unspoken, and it is just up to us to find it.”

You might want a DICER to make this yummy beverage Have an _____ grind (a grudge)

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Joe Maffa

FEATURE

Managing Editor

Klara Davidson-Schmich

Section Editors

Daphne Cao

Elaina Bayard

ARTS & CULTURE

Managing Editor

Elijah Puente

Editors

Section

Emily Tom

AJ Wu

NARRATIVE

Managing Editor

Katheryne Gonzalez

Section Editors

LIFESTYLE

Managing Editor

Tabitha Lynn

Section Editors

Daniella Coyle

Hallel Abrams

Gerber

POST-POURRI

Managing Editor

Rachel Metzger

HEAD ILLUSTRATORS

Junyue Ma Kaitlyn Stanton

COPY CHIEF

Emilie Guan

Copy Editors

SOCIAL MEDIA

Managing Editor

Tabitha Grandolfo

Section Editors

Alex Hay

Eliot Geer

LAYOUT CHIEF

Gray Martens

Layout Designers

Amber Zhao

Alexa Gay

Romilly Thomson

STAFF WRITERS

Nina Lidar

Sarah Frank

Pooja Kalyan

Ana Vissicchio

Gabi Yuan

Lynn Nguyen

Daphne Cao

Sofie Zeruto

Evan Gardner

Isadora Marquez

Ayoola Fadahunsi

Samira Lakhiani

Ellyse Givens

CROSSWORD

Sarah Kim, “Meadowmount, Music, and Magic” 10.21.22 Want

Lily Coffman

Gabi Yuan

Chelsea Long