Cover by Moe Levandoski @moelevo

Cover by Moe Levandoski @moelevo

OCT 21 VOL 30 — ISSUE 5In This Issue Meadowmount, Music, and Magic SArah Kim 5 Cute Aggression Ellie Jurmann 4 Daddy's Girl Ellyse Givens 2 The Winchester Robin Hwang 6 To Hold in My Hands Liza Kolbasov 4 postScrapbooking Marlena Brown 8

In my high heels, I stumble across the wooden floors of my kitchen. He’s already in the car, as he always is. I shove a Ziploc pouch of apple wedges into my oversized and overstuffed tote bag and flounder out the garage door.

“Sorry,” I murmur as I practically fall into the passenger seat.

“It’s okay, sweetie.”

He turns the volume knob gently as he begins reversing down the driveway. Sports broadcaster Dan Patrick’s voice draws my body a bit more from its early morning placidity. It’s time for work.

***

After the conclusion of my freshman year of college, I came home for the summer. I had secured an internship with a company whose headquarters happened to be a 5 minute walk from my dad’s commercial real estate office, where he’s worked for the past 9 years. Every Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday morning, I draped myself in business casual attire, feeling like a child in a costume,

Letter from the Editor

Dear Readers,

Happy apples-and-cinnamon season! Leaves on all the sidewalks crunch-crunching season! Finally listening to my Halloween playlist season! I’ll abandon my string of exclamations now, but suffice to say, I am pleasantly immersed in all those lovely mid-October things. And yes, there’s work to be done and readings that never end, but I simply will not let that deter me from my autum nal euphoria. Also, we’re fast approaching another mid-October staple—Family Weekend! I hope everyone is able to spend some time with family this weekend, whether that be visiting family mem bers, on-campus chosen family, or some other locus of familial connection. Family can be such a squishy term, at the end of the day.

This week, our Feature writer reflects on family connection, specifically writing about the evolution of her relationship with her dad. In Nar

Daddy’s Girl

a deliberation on drives with dad

By EllYse GivenS Illustrated by Lulu Cavicchi

and completed the 45 minute commute to downtown San Diego with my dad. I know—it was kind of the cutest thing in the world.

MGrowing up, my dad was always the ultimate girl dad. He knows all the moves to High School Musical’s ensemble number for “We’re All in This Together.” During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, he tied a bandana around the bottom half of his face and proceeded to call himself ‘John B’ (the star of Outer Banks). He can recognize a Shawn Mendes anthem from a single initial guitar chord. When I looked beside me as my family watched the conclusion of the Fault in Our Stars, he was crying nearly as much as I was.

Despite my dad’s endorsement of 21st century femininity, my younger self always wondered if he, deep down, wanted a son. What dad wouldn’t? My dad was a man without a counterpart; he had no one with whom to appreciate the manly delicacies of life: football, food, and foolishness.

This thought plagued my young mind, inspiring me to seek achievement in a sort of ‘masculine’ manner to cultivate true commonality between my dad and me. If I didn’t have a hobby whose intricacies could be analyzed and technicalized, what would we talk about? I didn’t want to unbox my emotions with him, not seeing heartto-hearts as one of the hands-on, interest-based activities conventionally shared amongst fathers and daughters. So, while my sister bonded with him over action-filled sci-fi movies, I sought recreational activities that could foster closeness between my dad and me.

Because he played golf in college, so I created for myself an athletic identitysportsI loved being an athlete more than anything. After my volleyball tournaments, my dad and I discussed playing time, debated game strategy, and compared players on other teams. It was my chance to be the ‘tomboy’ daughter for which fathers roared from the sidelines, to embrace technicality and competitiveness and fervent ambition. I would not cry

Grades

rative, one author reaches for a definition of the self, while the other writes about the concept of cute aggression. Our first A&C writer looks back on her experiences at violin camp and the second considers the complexity of his first time shooting a gun. In Lifestyle, our writer thinks about scrap booking as a potential outlet for the urge to collect memories, as an alternative to social media.

A wide range of topics in this issue! However you choose to embrace the orange loveliness of this season, I hope you do so with a copy of postin hand (or on screen!). And, hey, if your parents are comin’ into town for Family Weekend, give them a copy!

Watching the leaves fall, Kyoko Leaman Editor in Chief

FEATURE

1. 3rd 2. USDA certified prime 3. NC 4. Ariana Grade 5. Graded within three days of submission 6. Steep grade ahead, trucks use lower gear 7. AA Eggs 8. Curved 9. Gradient Descent ( ) 10. Scope 2 post

in front of him, would not show when the performance anxiety became too overwhelming to suppress. I fought back tears and battled my teammates for playing time; I nodded like a soldier when my coaches yelled, acting as if their harsh words were the fuel to my internal flames. I just wanted to make him proud.

When I began to want to stop playing volleyball, I was almost embarrassed, feeling like a failed tomboy, a daughter who’d surrendered to her innate feminine ‘softness.’ I remember when I told him I didn’t want to—couldn’t—do it anymore: I feared we would lose the closeness forged through our sports-based discussions. Yet in no time, I picked up another extracurricular pursuit that we could bond over. Although we both knew competitive speech and debate was the ultimate ‘nerd activity,’ my dad enthusiastically embraced this new interest alongside me. He woke up at 6:00 AM to take me to tournaments. He volunteered as a parent judge several times, for hours listening to 17-year-olds yell at each other. We discussed the intricacies of speech and debate competitions, the strategy of vocal tone variation, and the ineptitude of certain judges.

Yet still, I never cried to him, never displayed the anxiety that bubbled within me before each round. It was almost as if I were still an athlete.

***

When considering the social and moral development of a child, fathers are often left out of the conversation, with traditional fatherly archetypes characterized as working, breadwinning, absent figures within a child’s early life. But according to Dr. Linda Nielsen, a Professor of Psychology at Wake Forest University, fathers play a prominent role in developmental stages pertaining to risk-taking and self regulatory behaviors. Fathers are more likely than most mothers to encourage their children to take calculated risks, playing with their infant in ways that are more intellectually stimulating and physically demanding.

As a daughter ages, a father continues to encourage autonomy and “share his own excitement about work and recreation with her,” inviting daughters to partake in activities alongside him. Indeed, when she enters her teenage years, the father-daughter relationship is more closely related to her academic, athletic, and vocational success than her teenage relationship is with her mom, which tends to be more emotional. In fact, daughters at this age presume that “their fathers might either be disinterested or judgemental should they reveal what they are really feeling or thinking.” Licensed social worker Cara Brendler says that even ‘close’ fathers and daughters feel this estrangement, rooted in a fear that “being authentic will result in disapproval.”

Developmentally, it makes sense that I never wanted to cry in front of my dad early on, never wanted to go to him when friends or crushes or coaches made me question

my self-worth. Even though we were so close (he was the ultimate girl dad), I never wanted to seem weak to him. This aligns with the myth that Dr. Nielsen describes— that “men are not as empathetic…not as communicative… not as compassionate” as women. This is not the case, but because fathers and daughters operate under this stereotype, the daughter, regardless of the father’s actions, is “less willing or less apt to go to her dad because she already believes that men don’t communicate well, or men aren’t interested in hearing personal things from their daughter.” Not wanting to bore or annoy my dad, our exchanges remained lighthearted when I was young, centered around sports, academics, or recreation.

But this summer, I no longer had a core extracurricular activity. I was no longer an athlete, a speech-giver, or a tween eager to discuss Shawn Mendes melodies (although maybe still a little bit). I was a college student. I felt more complicated. It was almost as if emotions were the only thing I could articulate. Nevertheless, I wondered what exactly we would speak about during our 45 minute commutes; I hadn’t spent everyday drives with him since my sophomore year of high school. It was weird at first, sitting in the passenger seat of the same Chevy Volt that I loved just as much now as I did at 13. Being there again made me feel like I had to fold up and pack away all the experiences, dreams, and fears that had accumulated in my body during my first year of college, and shove myself into a sweatshirt that fit me snuggly seven years ago.

Day by day, though, my dad’s and my relationship evolved—just as we had. We laughed over the woes of business casual attire, over humorous coworkers, over the corporate American’s after-lunch-slump. In early June, I helped his coworkers organize a surprise, French themed birthday extravaganza in his conference room. We went on walks through downtown San Diego together, me in my heels and him in his brown loafers. With every step, I became more comfortable both walking on my stilts, and opening up to my dad. I asked him about his career trajectory, sharing my fears for how mine would eventually unfold. Disillusioned by office life, I would often ask him anxiously whether it was more important to love my job, or be good at my job. He told me that it would get better, and that I would find my way.

When my bosses’ comments pierced my armor slightly, my dad empathized more deeply than I could have imagined. So sensitive to words like I am, he showed me through example how to take critique “in stride,” reflecting upon but not personalizing bosses’ feedback. His boss came into town some days, and my dad was saddened by harsh commentary: I saw the disheartenment that gnawed at his spirit. Yet he did not allow these emotions to drown him, staying in the office late to improve upon his work. Like me, he was hurt by others’ words, but learned how to transfigure those

bruises into means of self-improvement. He showed me that my softness could actually be a strength. ***

This summer also brought another change. I brought a boy home for the first time, a wonderful boy. But – like any teenage girl – I stiffened when my father broached the topic. I found myself wanting to change the course of the discussion, quickly digressing into my then boyfriend’s favorite football teams as opposed to the actual feelings I had for him. A first boyfriend, to me, seemed like an initial symbol of a daughter’s womanhood, in a funny and weird way. I wasn’t ready to admit this to my dad. I wasn’t ready for us to both be adults, to disclose that I was no longer just his daughter, but a coworker, lover, and friend to so many other people he may never know as deeply as I.

Dr. Nielsen states that, because emotions often overrule girls’ rational thinking during teenage years, daughters are more capable of relating to their fathers maturely and rationally between the ages of 18 and 25. Education professor at Meredith College Tisha Duncan says that, at this age, young adults come to no longer view their parent as an “authoritarian,” but rather as a “confidant and adviser.”

Inadvertently, my dad and I both understood that I was no longer a daughter staring up to a master figure, but one looking beside her to an equivalent for consultation, guidance, and love. To my surprise, my dad did not scold me for the late nights I spent with my then boyfriend— and the grogginess lingering in my voice when I entered the car the following morning. He asked me questions not to interview me, but to love me as I began to love another man for the first time in my life. He didn’t attempt to deter me from entering a long distance relationship, but rather understood that I was 19—and that I wanted nothing more than for my emotions to dictate my direction. We spoke openly about my relationship without nervousness, nor judgment.

I finished my internship at the end of July, and I found myself feeling slightly empty. I wondered when I would ever have the privilege of spending that much time with my dad again. It was such a perplexing experience, to be on the cusp of adulthood, working in an urban office for the first time, loving my first boyfriend, beginning to think about the colors my future would assume—while also sitting in the same passenger seat I frequented every day in 7th grade. It was like looking over a cliff’s edge, but realizing I did not have to jump alone.

I held the door open as my dad walked into Goddard House for the first time in September, my new home for the year. I squeezed him tightly as we said goodbye, tears streaming down my cheeks. I didn’t need to be a ‘tough’ girl anymore—for my dad would always be there in the car seat next to me, as I take every every one of life’s changes “in stride.”

***

“I was sick in a sick-in-the-head sense, not in the literal sense.”

“Your car is Dorian Gray and you are the portrait.”

“Tell me he doesn’t look surprisingly submissive and breedable.”

FEATURE

***

October 21, 2022 3

To Hold in My Hands on trying and failing to define myself

by Liza Kolbasov Illustrated by Lucid Clairvoyant IG: @l.u.cid

by Liza Kolbasov Illustrated by Lucid Clairvoyant IG: @l.u.cid

When I was in fifth grade, I was given an assignment to write a poem about “who I am.” A big task, really, for a fifth grader with naive brown eyes and puffy cheeks and very little concept of what it means to be something or someone. Centered on a page, in a font meant to imitate handwriting, I carefully typed out:

“I am from Russia and worry a lot

I wonder if magic exists

I hear rain pitter-patter on roofs

I see puffy clouds in the sky

I want to be the best at everything I am from Russia and worry a lot

I pretend I am somebody else

I feel my mother’s hands on my cheek

I touch soft fur

I worry about a lot of things

I cry when I get bad grades

I am from Russia and worry a lot

I understand I am not perfect

I say everything is possible

I dream of being in a famous play

I try to be helpful

I hope others like me

I am from Russia and worry a lot”

It is uncanny, really, how much that fifth grader, fundamentally, has not changed. Some things have, sure—I no longer dream of being in a famous play, I no longer feel my mother’s hands on my cheek, I no longer say that everything is possible. But still. I worry a lot. I try to be helpful. I hope others like me. I want to be the best at everything. I understand I am not perfect. I worry a lot. I worry a lot. I worry a lot. A poem about who I am? Or a poem about not knowing who that could possibly be?

Maybe, when we grow up, it’s not so much that we learn who we are, but that we learn that we have never had any idea who we were in the first place. Is this all I am, all I ever was? A person who worries a lot?

myself standing in the kitchen, looking over a large pot of leeks. I haven’t been feeling well, and the inside of my head is filled with a hollow buzzing, like bees swirling inside a cave, my mouth sticky-sweet with their honey. I do not want to be a person who is filled with bees. Is that what I am? No, no, that can’t be right.

As they melt, the leeks smell sharp, spicy. I chop potatoes, smash and mince garlic, pour in a can of coconut milk. I run my hands over the potatoes as I chop them, feel the indentations where they used to have eyes. Let the scent of garlic stain my hands and my clothes. Soup is one of my favorite foods, thanks to how easy it is to make and how it coats my insides with warmth. It appeases the bees, lulls them into a soft sleep. For the moment, I am a person who has made a large vat of potato-leek soup.

I let that piece of information float in my mind among the bees, turn it over on my honey-coated tongue like a cough drop. I am a person who has made a soup. I find this strangely comforting.

***

It stresses me out how much our culture forces us to be constantly defining ourselves. Who are you? What makes you tick? What are your hobbies, your interests? Define it, make it easily packageable and marketable, and ship it off under the label of “identity,” leaving you the same formless blob you began with. But really, please tell me, what does it mean to be someone?

Is that who I am? Am I doing this right? I can’t shake the feeling that someone would disapprove.

Erik Erikson’s stages of ego development state that we go through the stage of “identity vs role confusion,” in which our senses of identity are established, between the ages of 12 and 18. As a psychology major, I could recite facts about various personality theorists’ beliefs about identity and self-perception, I could talk about the debate between the role of nature and nurture in shaping who we are, I could tell you about the causes and treatments for personality disorders.

But as a person, I cannot tell you anything. Am I even a person if I do not know who I am? As a ghost, then, perhaps.

As a ghost, my sense of self fell apart at 18, rather than crystalized. I had gotten into college, and found myself walking face-first into the glass wall that is The Rest of Life. The teetering jenga tower that was “Liza” came crashing upon the floor, kicked by the pandemic and smashed against the cliffs of college. I was, if anything, more mired in the sea of “role confusion” than I ever had been.

I say that as if I’ve resolved this conflict. That’s how it goes, isn’t it, when you write about your feelings? You go through conflict, and at the end you tie it up neatly with a bow of resolution. Leave the reader with a satisfying take-home message to hold under their tongues.

No, no, I’m sorry, there’s no satisfaction to be had here. I have yet to figure out how to pick apart this thing that calls itself sense of self. I can approach it with silly little metaphors—reach my hand into the beehive, look for crystals in the honey. Dig for words amid the chaos. But it’s too vast, too confusing. The only way to survive is to simply exist.

***

Please, stop asking me who I am. I don’t know how to answer that question.

I make a soup—sweet potato, potato leek, butternut squash. I embroider three wonky carrots on a tote bag and a bunch of flowers on the pocket of a pair of jeans. I understand I am not perfect. I hold hands with people I love. Propagate my pothos and watch its roots grow longer and longer. I try to be helpful. Feel my shoes sink into the soft mud as I run. Chop vegetables and mince garlic and make sauce and mix milk into coffee. I worry a lot. Look up at the clouds as I walk and pause, for a moment. I hope others like me. Give hugs and hold on tight.

Could that, maybe, be enough?

***

No, that’s not right. Let me begin again. It is midafternoon on a Friday, and outside it is raining. I find

I am a person who embroiders badly. I stab my fingers with the needle by accident as I make wobbly, child-like carrots line my tote bag, thin and scrawny, as if they were the last few to get picked out of the bushel at the farmer’s market, sold at a reduced price. And yet, time after time, I sit at the dining table as conversation bubbles around me and stitch uncertain stitches into the tan fabric. Draw with an insecure fifth-grader’s hand on a twenty-year-old body that has never taken an art class. Attempt to pull light orange thread through the eye of the needle—make it on the fourth try. Turn the words satin stitch, stem stitch, french knot over on my tongue, let them melt into honey. Try them out, make them wobbly and a little too far apart. Carry the tote bag anyway, although not quite proudly, because after all, I bought it and spent time making it, and it would be a waste not to use it.

Here, I think, is what I might be trying to say: I am a person who stands under the stars, holding pieces of scattered self in their hands.

Cute Aggression beauty is pain

by Ellie Jurmann Illustrated by Audrey Wijono

As I walk into my living room, my dog Sammie lifts her head at the sound of my approaching footsteps. My eyes meet her sleepy round ones, full of——as I believe——the secrets to world peace and of the universe. As I gaze into her sweet chocolate eyes, I notice the slight wag of her perfectly curly pug tail. I

NARRATIVE 4 post

***

***

am overwhelmed by a sudden intense urge to scream at my fur baby girl.

I realize that sounds totally uncalled for, but this is where I introduce the concept of “cute aggression.”

I have become very familiar with this idea ever since adopting Sammie. Cute aggression is the feeling you get when something or someone is so cute that you just want to squeeze them or, as some say, “eat them up.” Now, I obviously have no intention of hurting the adorable creature I love so much, despite these intense feelings. Even the idea of accidentally stepping on Sammie’s paw knots my stomach and makes my chest feel heavy. In fact, the experience of having such cuteness in my life is so beautiful, and so heartwarming, that it literally causes me physical pain.

I honestly have no idea if feeling pain is an inherent part of experiencing cute aggression, or if it is just a bonus comorbidity that I have been blessed with. I am not even being dramatic when I say that looking at my dog causes me to feel like my heart is exploding. It feels like someone has clasped my heart between their two hands and is squeezing so tight that it completely bursts open. (My apologies for the somewhat gross image evoked there.)

While I may experience painfully intense emotions when looking at something cute, I am so grateful for how much I get to feel on a daily basis. I love how I gasp when I find gorgeous blackberries at the supermarket. I revel in the joy I get from ordering an iced matcha with oat milk and raspberry syrup on the sunshiniest days. I live for the feeling evoked by nearly every item at Trader Joe’s, or how I full-on squealed when I found a BABY PINK Trader Joe’s employee tee while thrifting. The list goes on and on, but basically I have no chill about anything, especially when it comes to any of the finer things or simple pleasures in life. I know those categories cover a lot of territory. Anything aesthetically pleasing, evocative of warm and fuzzy feelings, or designed for any sort of human enjoyment, I am all over. I am not only obsessed with cuteness, but aggressively obsessed with all the many joys of life.

I owe Sammie an abundance of gratitude for my passionately positive attitude. She is—and always will be—my most extreme obsession, and if you saw her face you would immediately understand why. I have always been rather chipper, but it was not until Sammie came home to me that I knew feelings could be this intense. I have wanted a dog ever since I could spell the word. Sammie being the embodiment of all my hopes and dreams, coupled with her perfectly smushed face, means that she was always destined to

be the center of my universe. Plus, as silly as this may sound, I think the fact that she does not speak any human language adds to my mental image of her as the epitome of absolute goodness, kind of like a newborn baby untainted by the world.

But it would be totally untrue for me to claim I love Sammie for being untainted by the world, because she certainly has been. My heart shatters into a million pieces thinking about all of the possible places her scars may have come from. There exists no worse feeling than seeing the look of utter terror in her eyes when she used to cower on reflex, tail between legs, when someone would lift a hand to pet her. While she does not do this anymore, it took several years for her to trust us enough to unravel these long-reinforced instincts developed from god-knows-what evils she faced.

If anything, though, watching her learn to trust me healed both of our souls in away that I think forever changed me. I now understand the preciousness of life in a way I never had before. When I look at Sammie curled up in a little ball on the couch, I have no choice but to scream in her face. I mean, just look at her face!! I simply want to inhale her wheat-y fragrance. If you do not have any pets I am sure you are ready to call the local psych ward on me. I assure you, though, both my parents are therapists, and they are only moderately concerned about my Sammie obsession. This is probably because they are obsessed, too.

While the degree of cute aggression is vastly different between my parents and me, we do all scream for joy at the sight of our baby girl. Not only has watching her heal from her past trauma bonded us, but Sammie healing me from my own various insecurities and struggles has made me love her in a way so intense I cannot handle it. She and I are really the epitome of “who rescued whom.” The combination of her already perfect cuteness and the way I associate her with everything that is good in the world causes an overload in my brain that causes aggressive enthusiasm every time I see her. While to a slightly lesser degree, my matcha drinks, my novelty thrift finds, and all things pretty and nice also cause me to shriek with excitement at just the thought of how much happiness they bring me. I want to treasure all beautiful things in this world and scream from the rooftops about the joy they bring me.

I get overwhelmed constantly by the fervor I feel, but what would my life be without it? Trying to imagine has me feeling deplete of emotion; for the longest time such intensity is all I have ever known. My case of cute aggression may be rather acute, but I could not be tepid when looking at my dog even if I tried.

Meadowmount, Music, and Magic finding feeling in fauré

by SArah Kim

Illustrated by Connie Liu

In kindergarten, our class read the story of the Gingerbread Girl who comes alive after she is baked and runs away to escape being eaten. We had parents come into class and help us build gingerbread people as a fun, relevant activity and then we set them in the oven to bake during recess, only to find them missing when we returned.

Five-year-old me had to reckon with this: surely the gingerbread people didn’t come alive and run away… right? But why would we have gone through all that work of having parents come in and help us bake if we weren’t even going to enjoy eating them? Was the entire school helping us search for the gingerbread people out of their commitment to the bit or was this a serious, real event?

My only logical conclusion? Magic. And until I realized—perhaps later than I should’ve—that the teachers and parents were just having fun, that story was my anecdote of magic, real and tangible as anything else.

Many of us believe the world is too extraordinary to be completely devoid of a sort of… magic. Maybe it fits it into the articulations of religion, metaphysics, the universe. Whatever it is, many of us find that personal anecdotes and stories (of lost wedding rings recovered from the bottom of the ocean, or finding yourself next to the random person you had an incredible connection with at a bar months ago whose number you lost) validate this enough.

I believe music is one of those extraordinary things, which I realize is no radical original thought. It’s likely the same motivator behind playing classical music for your unborn baby or playing at a nursing home—music has this ability to touch suffering hearts, to inspire, to open people up emotionally to buried meanings in their lives, to elicit peace amidst a season of chaos. I think this ‘ability’ is where the magic lies. While this sentiment is felt to differing degrees according to personal history and preferences, classical music reserves a unique space in this conversation. It's easier to understand the way lyrics tell a story–artists have a message to share with their audience; they take emotions, convert them into words, and reveal meaning. Coupled with the right soundscape, instruments, and production, a song is elevated to drive that message home, whether that be emotional, uplifting, or honest.

But with classical music, how is the story told? Is it the melody? How does an interval, a chord, share grief or passion, or create its own version of dialogue? (If you have your pen and paper out, ready to take notes and explore this topic on your own, I’ll tell you that Tchaikovsky’s Peter and the Wolf is a piece that demonstrates this exceptionally. Each character is represented by an instrument and never before has storytelling with classical music made so much sense. However, I won’t assume this and continue writing.)

There is classical music I believe I understand, or at least understand how it moves me. Mahler’s fourth movement of his first symphony makes every cell in my body palpitate with raw energy,

NARRATIVE October 21, 2022 5

like a bolt of lightning ripping from a cloud, a trembling havoc splitting the sky. Wagner’s Feirerliches Stück makes me so emotional that I cried the first time I watched four cellists perform it and kept the program like a movie ticket stub saved from a first date. And Schoenfield’s second movement, the moment where cello and piano modulate to major over the sustained note on the violin ignites the most intense relief in every nerve of my body, as though thick, viscous honey is being extracted, oozing out of every pore.

But then there is classical music like Gabriel Fauré’s Violin Sonata in A major whose music gambles with traditional French music to create his own musical idiom. There is music like his whose sonata is abundant with daring harmonies and sudden modulations, still invariably carried out with supreme elegance and a deceptive air of simplicity. Arcane details lie in his compositions, demanding a sort of path of access that must be discovered and pursued.

I typically reserve technically difficult or time-consuming pieces for the summer, where I know I’ll be spending seven weeks as an isolated monk practicing in a cabin at Meadowmount. These are weeks meant to drill, to experiment with sounds and techniques, to get frustrated with pieces and see them through. My reaction to Faure’s Violin Sonata or really, the lack thereof, seemed to be a reason to spend the summer of 2019 learning and untangling it.

If I can contextualize: I rely on ‘the way something makes me feel’ in order to figure out and assess how I feel; my emotions are not the byproduct of thoughts but the producer. For better or worse, I am sensitive to these emotions and so, when I get that brain notification that I’m feeling “something,” I’ll search in my articulations of feelings, figure out its name, and from there, analyze what such a feeling means. This is how I build and navigate my understanding of myself in the world. And perhaps more than any bad feeling, it is most concerning when I feel nothing at all.

For example, I once spent close to an hour alone in the cereal aisle of a grocery store. I stood there, trying to figure out how I felt about each cereal, figuring out which one would serve me best at that moment. Did I want the sweetness of

the Lucky Charms cereal coupled with the crispy and crumbly texture of the marshmallows or did I want the nostalgia of Pops shoved into my mouth? Fighting aggressive ambivalence, I left with no cereal; in the absence of decisive feelings, I was lost.

Confronted with the lack of heartstrings being tugged and mind running empty on ways to extrapolate meaning from Fauré’s sonata, Meadowmount, with its quirks and cracks, proved quickly to be the perfect landscape to uncover the feeling. At 7:30 a.m. each morning, tired musicians slowly shuffled their way to the main house, motioned a spiritless wave to their counselor to confirm consciousness, and relished in the remaining half hour we had before practice hours commenced by engaging in gentle conversations over remarkably unmemorable breakfast. Minutes before 8 a.m., I’d take my violin, music, notebook and pencil and make my way to my Stradivarius cabin. A violinist and her metronome methodically drilling Prokofiev runs out of one cabin and a cellist hellbent on Shostakovich double stops out another–the sounds of acoustic strings beginning to braid with the chirping of birds and mooing of cows to fill the space between the trees. My pace would slow and I’d linger by, listening and playing a guessing game of who I thought was playing. Walk a little farther, just around the bend, and there she was: weather-beaten wood clapboard painted a deep forest green and one white door with a just-lessthan-completely-battered mesh screen on the outside; one window, one stand, two chairs on the inside. This was where I practiced.

Day after day, I returned to the cabin. Once I had unveiled my violin from beneath her dark blue velvet blanket with its sleek silver underbelly, I secured the shoulder rest into place. Then, just as I did yesterday and just as I would do tomorrow, I began: scales and etudes running through my left hand to warm up followed by my Leviathan: Fauré’s Violin Sonata.

I tell you all this not to precede a detailed outline of how this sonata should be played or to explain how stiff melodies between the violin and piano will instead reveal a beautifully woven relationship with just the right amount of nuance and context. If anything, I have realized it is near

impossible to do that with a piece of music–that is, to explain how it is to be played. Because perhaps even with all the recordings in the world and all the best teachers to help guide you, even with time and patience and perseverance, that is not what gives way for notes on a page to transcend to become music: transformative and meaningful. Perhaps more than anything, it is in the choice to pursue and uncover that music comes alive in the way we imagine.

So often do the beauty of things like the color of someone’s eyes or the wave of the ocean swelling from underneath and finally breaking to crash at the shore become mundane and ordinary when they are meant to be awesome and inspiring. I think no matter how calloused we can become in life, there are certain things that can reignite this beauty we know to exist, reminding us to hold those things near and precious. Paths are personal and unique, and it seems as though classical music is mine. Fauré taught me that sometimes, to understand something, you must be willing to go to it; you must find your own answers. Where there is potential to discover, you must make that move and choice to seek it.So maybe magic is not reserved exclusively for the naive minds of kindergarteners. Maybe it rests most abundantly in the things unassuming and reckless and unspoken, and it is just up to us to find it.

The Winchester a first-time shooter’s review of clinking

by Robin Hwang Illustrated by Connie Liu

“Robin-Robin-Robin–after this, you’re gonna be a man!”

Kyle ends his playful, sarcastic comment with a measure of reassuring laughter. Today is the highlight of my friend group’s trip in southern Montana. My friends Jason, Sean, Kyle, and I had whizzed through numerous hiking trails of the stark mountains nearby, and we were running out of things to do. On the fourth day, lounging in the living room of Jason’s family ranch, my friends

ARTS & CULTURE

6 post

stumble into a revelation: I had never seen a real gun before.

Having spent half of my life in gun-restrictive Korea and the other half in suburban California, guns existed as the flashing sidekicks to action movie heroes rather than the quiet mass of steel they were in reality. Kyle and Sean are better acquainted with guns, having gone to a shooting range together last year. But Jason is our chief expert. Since he was eight, his summer stays at the ranch were interspersed with his uncle gently guiding Jason’s lanky frame into the lithe stance of a seasoned marksman.

A boyish motivation to be part of the group leads to the conclusion that I must shoot a gun by the end of the trip. As Jason leaves to ask his uncle about borrowing the guns, the room trembles with ecstatic conversation. Recalling his previous time at the range, Sean demonstrates his stance with the confidence of an Olympic athlete. Kyle teaches me about conscription in his home country of Switzerland, through which most people our age learn how to shoot.

Listening to the hum of conversation, I hold on to a quaint sense of appreciation for this moment. I know my friends here, like many Brown students, look at 2nd Amendment rights and gun-waving machismo with skepticism at best. But the combination of humor, curiosity, and fantasy gives me the sense that we’re indulging in a small dose of simple teenage boyhood, before the realities of a final year in college confront us on our flight back to Providence.

Jason instructs our rowdy group to gather materials for clinking–that is, the act of shooting at small targets for entertainment. As we get to work, we pluck out crumpled up coke cans from recycling bins to fill with tap water. Jason reaches into the fridge to take out the half-foot-long Jimmy Dean pork sausage roll that no one has eaten (we will be leaving in a few days, anyway, and no one is eating it, so we might as well shoot at it, or so goes the logic).

The door clicks open. A hush falls over the room. In the doorframe, Jason’s uncle is holding two guns–a small revolver and a 22-caliber Winchester rifle. Jason confidently wraps his hands around the guns, though he matches that confidence with a cautious move to point them to the ground. The presence of amateurs motivates him to model professional safety. He beckons us outside.

A moment of awkward stillness arrests any movement towards the door. My friends and I refuse to walk ahead of Jason for any reason, because a sudden image jabs into our minds–a freak accident where the guns point up and shoot into our backs. Kyle tries to break the silence with an awkward laugh, to suggest that “uh…maybe Jason should lead.” After some timid chuckles at the recognition of our hesitance, an appearance of relaxed enthusiasm returns, though we remain behind Jason at all times.

A wide-open sky greets us as we step outside. Though it’s mid-August, the altitude and the mountains that surround us in the distance bring cold winds through the dry grass fields of Jason’s family ranch. We trudge over to the east, where an unassuming hill unfurls onto the sea of grass.

In contrast to the majestic scenery, the four of us are all hunched, hands awkwardly hiding in our pockets or holding boxes of the targets. Before setting up the cans, Kyle’s feet are glued in place until Jason swings the rifle to the ground. An argument between Sean and Jason interrupts the stillness of the grassfields–just aim the gun north

for the safety demonstration. Dude no I can’t; you can’t see who might be in the grass there. Just aim way above it. No, that's still dangerous. And so on.

A frown sets over Jason’s face as he explains gun safety: Never point it at someone. Always assume it’s loaded. It’s your responsibility to make sure that the gun is not loaded, even if someone else says it is. Assume that the safety lock is not functional.

A dry heartburn sparks in my chest from seeing my friends argue in the company of deadly weapons. The altitude or anxiety or both force us to take shallow breaths. Part of me wants to go back inside, but my curiosity locks me in place as Jason steps up for a demonstration shot. He deftly brings the barrel against his shoulder, while his head tips to line up his vision with the sights. A breeze sweeps his hair off to the side of his face as we wait for him to–POP!

Jason’s shot is followed by a faint tweeee. It’s the sound of ricochet, and Jason mutters a quick “shit!” before turning to tell us that we should change locations. It has something to do with the angle or the ground material or something that’s making the bullets bounce off, but shooting here can be dangerous, he says. Kyle looks at me with a sardonic smile. As if it’s ever totally safe to shoot anywhere, his face seems to say. I match his twisted smile with my own, although they both shift into more of a grimace of repressed anxiety.

After we set up again, my friends take turns trying out the guns. After a few initial stopsand-starts and reviews of loading and cocking, we get into a rhythm. Cluck-cluck. POP. Cluckcluck. POP. As each of my friends get comfortable with the gun, they become more ambitious. The gunshots speed up. Water spurts from the cans. Can-tops fly off. I stare at their focused eyes with an equal mix of awe and terror–has this ferocity always been a part of them? Was it there, even when I saw their eyes soften with tenderness as they told me about meeting their girlfriends for the first time? Or is the gun entrancing their eyes to transform into a dark, deadly shadow?

With a small lurch in my stomach, I realize that my turn has come. I take the rifle gently from Kyle. Are my hands shaking out of fear or thrilling anticipation? I’m not sure, but they move without

my conscious direction, finding bullets and loading them into the barrel. I get up.

With my head tilted, looking down the sightlines, my vision warps around the barrel that reminds me of a childish memory of exploring a mirror maze–how the concave mirrors blow out the reflection’s center. The bushes and grassfields in front of me slow down, while the sky narrows to an unfamiliar sliver of color at the top of my vision. My breath becomes quiet. I register a gentle surprise at the sense of peace filling my mind, like I could stay still for an eternity in the split seconds that pass by between my breaths.

I pull the trigger.

The recoil gently pushes into my shoulder. My hands, almost by instinct, give the forearm of the gun a quick pump, as my mind registers the dust my bullet kicked up. Too lLow, whispers a voice in my head. Click-clack. I fire again, and again. Seeing a can drop on the other side fills me with ecstasy and an unquenchable thirst to shoot again. I take aim again, towards the sausage this time. POP-POP-POP!

My friends cheer at the sight of my targets falling down. They are laughing again now, enthusiastic at the damage we can unleash together. I start to chuckle with relief at being able to join in the same pleasure as the rest of the boys.

After 30 minutes of shooting, the sun begins to dim, so we reluctantly pack up to go inside. I am making dinner with Sean that night, and the large kitchen knife in my hands slices up-anddown through layers of red onions whose scraps I carry over to the garbage can. Sean asks me if I enjoyed my first time shooting, and I mumble a polite response about how I could see why others enjoy it, but that it felt too violent for my liking.

But I was lying. As I gaze into the garbage can, I realize the actual target of my deception: myself. My own self-image as the lefty-hippie humanities-major in the group, full of dreams about a future without guns and violence, was put into question. As I gaze into the garbage bin, I can finally recognize the sliver of color at the top of my vision while shooting the Winchester rifle as pleasure–for it was a red, a red as bloody and scarred as the bullet-riddled sausage roll, rotting in its own juices at the bottom of the bin.

ARTS & CULTURE

October 21, 2022 7

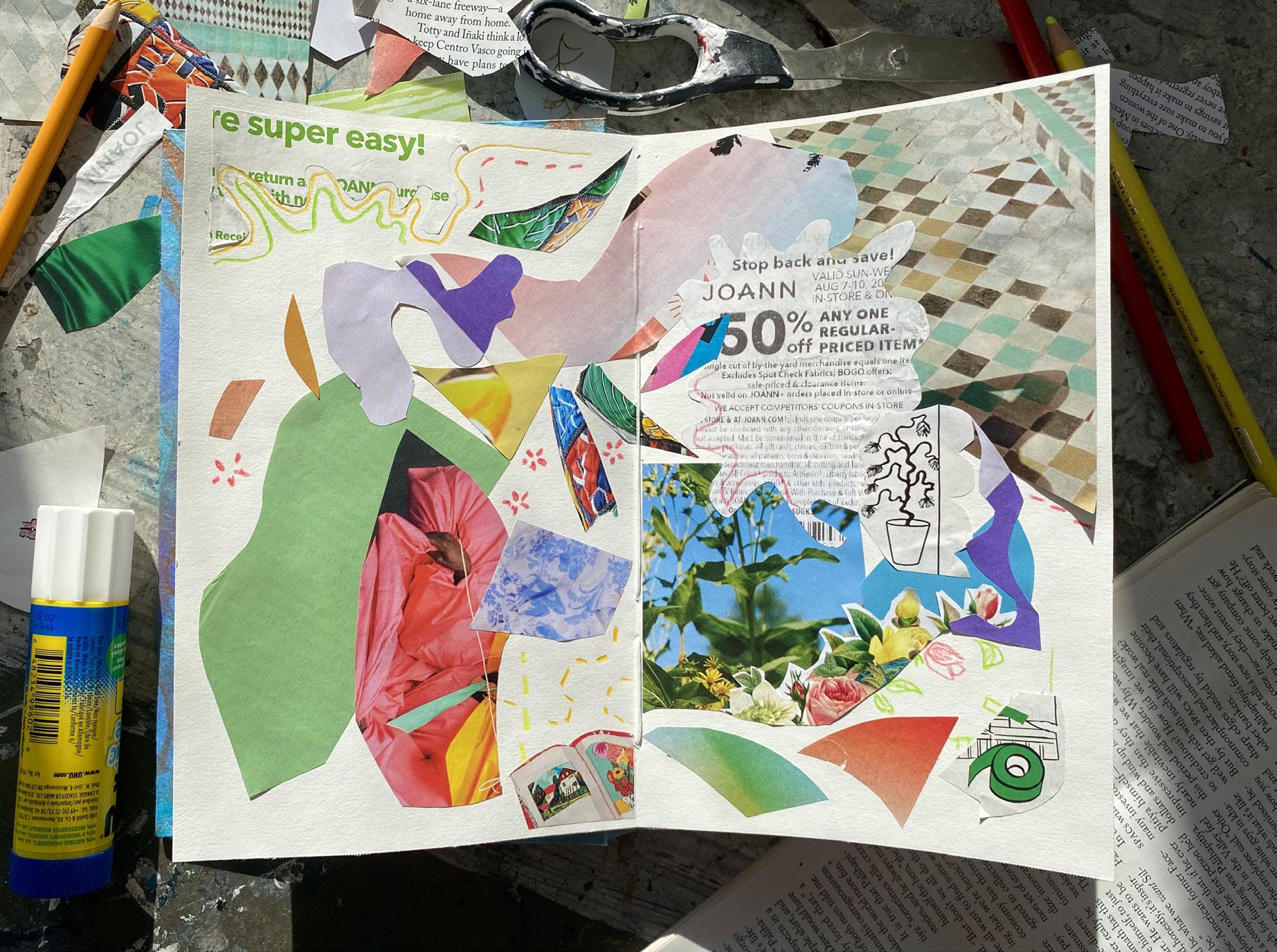

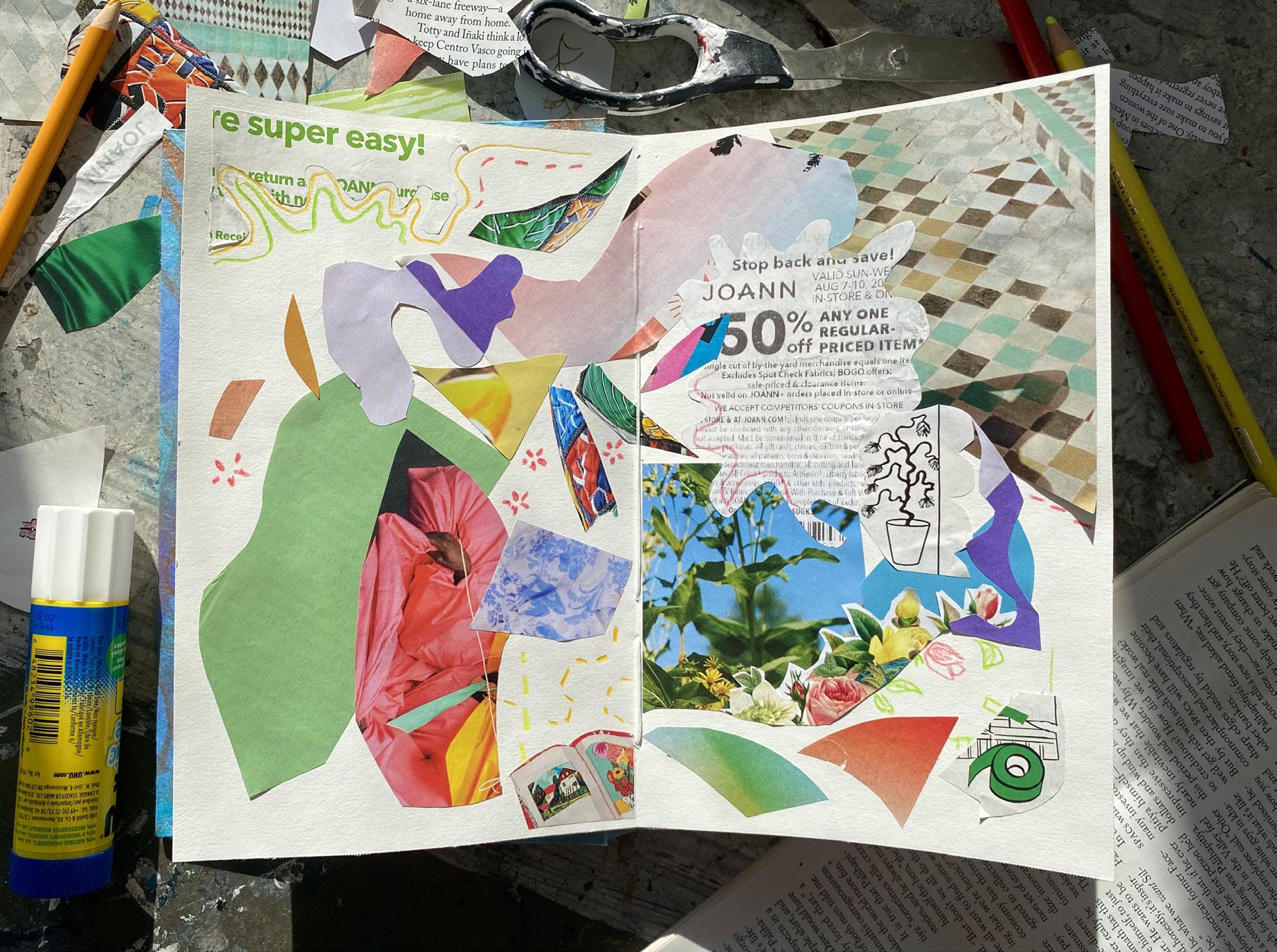

Scrapbooking the original casual instagram

by Marlena Brown Illustrated by Hannah Bashkow

Since around summer 2020, “casual Instagram” and other “casual” forms of social media have taken over celebrity profiles—not to mention those of the general public. Despite conflicting opinions on the trend, casual Instagram has many dropping highly edited posts in favor of blurry mirror pictures and overly zoomed-in photos of their dog. Casual Instagram speaks to an instinct to just record our lives, even the nitty-gritty, day-to-day elements of it, to look back on later.

While the photos themselves are unedited, there’s a kind of curation that can evolve out of a casual Instagram account. For example, one might post a series of heart-shaped objects or quotes about sisterhood, so that a theme emerges even from a “casual” account. Digital collections have even made their way to other platforms, including the recent trend of TikTok photo collages. Scrapbooking, then, is the nondigital equivalent. Which is why scrapbooking,

of all things, is your new alternative to casual social media.

The scrapbook, however, is unique from other forms. When I graduated high school, my grandmother gifted me the scrapbook she’d been putting together since I was born. It was unlike most gifts I’ve ever received; I could run my finger over the photographs and stickers spanning 18 years. There’s something to be said for the tactile nature of a scrapbook. For the same reason that those who grew up in the digital age turn to vinyls and camcorders, the analog format of scrapbooking demands the practice of attentiveness. Documenting a life with paper scraps in one’s own handwriting takes a different kind of time and care. And that attention is rewarded by a scrapbook’s permanence. Many also curate physical scraps on dorm walls or through computer stickers. But we move locations, platforms change, passwords are lost. A scrapbook is physical, tangible, portable, and can therefore be kept and cared for.

The real advantage to the scrapbook, however, is its intimacy. An Instagram account, a phone case, or even the walls of your dorm are open to public perception. This creates an awareness of the external gaze, conscious or not, that affects how we curate. In my opinion, that awareness is the root of the frustration casual Instagrams have stirred up. There are numerous articles lamenting

the performance that is casual Instagram, despite its facade of nonchalance. Yet I want to give credit to owners of “casual” accounts. There is nothing inherently wrong with the curatorial instinct of Instagram; we just must also acknowledge that accounts exist in the public eye. The solution, then, isn’t necessarily abandoning a more casual aesthetic and returning to carefully perfected profiles. Instead, scrapbook.

Scrapbooks, unlike profiles, can remain entirely private. On some level, you have to invest mental and emotional energy into posting casually—it’s hard to document yourself honestly while simultaneously being aware of how you will come across. Scrapbooking, on the other hand, requires no extra energy. Journaling, then, is a private practice you might turn to. But, at least for me, it can be somehow difficult to write without imagining a disembodied audience, and journaling becomes tiring. Because scrapbooking is visual and tactile, it’s harder to create a scrapbook “for” anyone other than yourself–— unadulterated self-expression becomes intuitive.

It’s uniquely meditative to sit up late at night, sorting bits of receipts and paper animals you rescued from your coat pockets and arranging them on a page. You could start today, even if you don’t pick it up again for three months–no one will know. Because scrapbooking is an art of curation that’s meant for you alone.

“My name is like my hair: hereditary, curly, and meticulously looked after. A name that’s nine letters long is hard to fit into, but it motivates me to keep trying.”

—Magdalena Del Valle, “A Name with Room to Grow: Part Two” 10.22.2021

“I no longer felt my mother’s trust in me or her shadow over me. Without my mother’s shadow, was I still as beautiful as I thought I was?”

—Ingrid Ren, “For the First Time” 10.23.2020

LIFESTYLE Want to be involved? Email: kyoko_leaman@brown.edu! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kyoko Leaman FEATURE Managing Editor Alice Bai Section Editors Addie Marin Ananya Mukerji ARTS & CULTURE Managing Editor Joe Maffa Section Editors Katheryne Gonzalez Rachel Metzger Copy Editors Eleanor Peters Klara David son-Schmich Indigo Mudhbary SOCIAL MEDIA HEAD EDITORS Kelsey Cooper Chloe Zhao Tabitha Grandolfo Natalie Chang LAYOUT CHIEF Alice Min Layout Designers Alice Min Caroline Zhang Gray Martens Jiahua Chen NARRATIVE Managing Editor Siena Capone Section Editors Danielle Emerson Sam Nevins LIFESTYLE Managing Editor Kimberly Liu Section Editors Tabitha Lynn Kate Cobey HEAD ILLUSTRATOR Connie Liu COPY CHIEF Aditi Marshan STAFF WRITERS Dorrit Corwin Lily Seltz Alexandra Herrera Olivia Cohen Danielle Emerson Liza Kolbasov Marin Warshay Aalia Jagwani AJ Wu Nélari Figueroa Torres Daniel Hu Mack Ford Meher Sandhu Ellie Jurmann Andy Luo Sean Toomey Marlena Brown Ariela Rosenzweig Nadia Heller Sarah Frank October 7, 2022 8

IG: @hbashkow

Cover by Moe Levandoski @moelevo

Cover by Moe Levandoski @moelevo

by Liza Kolbasov Illustrated by Lucid Clairvoyant IG: @l.u.cid

by Liza Kolbasov Illustrated by Lucid Clairvoyant IG: @l.u.cid