Cover by Ella Buchanan Insta:@nanahcube OCT 14 VOL 30 — ISSUE 4In This Issue Long Way Home AJ Wu 5 The Walls and Me Mack Ford 4 Detaching From Detachment Joyce Gao 2 Talkin' Tennessee Evan Gardner 6 Life as Conjunctions Marin Warshay 3 postOf Wind and Fall Layering Sean Toomey 7 Surviving Sick Season Nadia Heller 9

Detaching From Detachment and how I learned to enjoy sweet potatoes

By Joyce Gao

Illustrated by Lucid Clairvoyant IG: @l.u.cid

I’ve always known that if you really try to stare into space long enough, you can pry open the screen of reality and reveal a sliver of what is behind. Growing up, it was like a game, to lie awake during naptime and stare until I could see the frames of the world shifting off-kilter the slightest bit, just enough to let the detachment come through. Since reality was no longer real, I was no longer attached to anything: not the wooden bed frame, the drywall ceiling, my family’s conversation in the next room, or the body I reside in. My mind floated up like a heavy but determined helium balloon, to a distance where the world below looked like a cool Julian Voss Andreae sculpture; if you try a different angle, everything disappears into thin air. Once I was done with the game, I would break my gaze, and reality would readily unfold to occupy my entire field of vision again.

In psychology, this feeling is called depersonalizationderealization: observing oneself outside of one’s own body and perceiving things around oneself as not being real. Although classified as a disorder at the extreme, most people have experienced this feeling at some point in their lives. For me, naptime during kindergarten was when I most often allowed myself to drift into detachment. I distinctly remember the lines of the ceiling tiles in the nap room, since I have seen them tilt and bend so many times in my mind. The teachers would shut the doors and windows to block out the sound of traffic, but in my moments of detachment, nothing could stop me from floating out to the city streets and looking through the window at a room full of sleeping children. I saw my friends sleeping in their small wooden beds, and I saw myself breathing under a blue blanket, all the while feeling the rise and fall of my chest and that same blanket tucked snugly under my chin.

It usually took some time to fully return to my body after naptime, and even then the aftertaste of the experience tended to linger. Once, we had sweet potatoes after the nap. Still dazed from detachment, I suddenly began to think about how unreal food and taste are. I really like sweet potatoes, but during a moment of detachment, they were just a pleasant illusion—and pleasant illusions are still illusions. What is the point of enjoying something that might not even exist? As I chewed on my sweet potatoes, I felt like I was just biting down on air. If sweet potatoes didn’t matter because they’re an illusion, then neither would warm blankets, friends, or earning a prize at school. The same thought process applied to less pleasant things, like feeling abandoned by a friend or losing a beloved toy:

Letter from the Editor

Dear Readers, First off, a virtual—or printed, depending on your preferred post- form of consumption—hug to all of you wonderful people. As we go around our oblong Prod table (over)sharing our responses to this week’s icebreaker (“How are you doing—like, actually doing?”), I’m acutely aware of our mutual desire for care as the semester reaches its midpoint high—or I guess low. For me, these tiny desks have been my support network getting me through the week: Those cute little seat desks where I let myself doze as my professor waxes poetic about strategy patterns, and dependency injections, and such and such that gets explained between my extra long blinks; NPR’s Tiny Desk where I find myself singing and conversing through the screen, as if catching up with Phoebe, Omar, and Lianne over a jam sesh and a cup of tea; The unsettlingly pretty desk in the upper bounds of the CIT where we cry over our code and

If neither pleasant nor unpleasant things are real, then it makes no sense to get all involved and emotional about them. If I wanted, I could just detach at any moment, so the people and events in my life reach me like commotions on land reach a fish in the water.

As I grew older and had less time dedicated to stare at the ceiling, I visited the feeling of detachment less frequently. Even so, it was comforting to know that it was an option. By the time I was a teenager, I checked my ability to detach like checking on a homemade fallout shelter. It became less about the sensation of detachment itself and more about the reassurance that, if things got out of hand, I would still have this last escape to buffer me from the unpredictable world outside.

***

Right before I came to the United States for college, I lost my ability to detach. I was in a small hotel room in Hangzhou that smelled of cigarettes and dampness, sniffling from the cold and a long cry. I went there for a nonprofit training event with a friend, who was sitting in the bed next to mine. By day, we learned about the organization and practical skills, and by night, we talked about ourselves. We did the classic retreat-style activity of sitting around a dim

laugh over out-of-context Slack channel musings; And at the end of the day, my all-too-small Harkness desk where I return to a bowl of Frosted Mini Wheats from Jo’s and J Kenji Lopez Alt’s new noodle recipe. Our authors this week appear to be searching far and wide for their own care networks. In Feature, the author peers into the abstract and unpacks the dissociation she has felt at different points of her life, and the acts of love that bring her back to the pres ent. One of our Narrative writers balances caring for herself in the moment, and for herself in the future, while the other one contemplates the comfort she finds inside significant walls. For A&C, our writers discuss the homes they find in unexpected places: whether that be through reading between the lines of Morgan Wallen’s music, or watching their relation ship with their parents reflected on the silver screen. And in Lifestyle, our writers discuss physical wellbe ing, be it staying warm (and stylish) as the weather gets nippy, or staying healthy as everyone—me and my choppy cough included—seems to be falling ill.

light and sharing our darkest moments until everyone cries. Clichéd, I know, but the intimacy alone was enough to bring me to tears. I don’t remember what I said, but I do remember crying and confessing while my chest trembled like aged machinery. The tears came from a combination of being so intensely connected to a group of people, talking openly about myself for the first time in a while, embarrassment, and feeling simultaneously hopeful about the changes I could make and hopeless about the limits of that future. I was too overwhelmed to process all of these emotions and possibilities—so I cried instead.

Emotions still brimmed to the edge of my heart when we went back to our hotel room. I knew if I let all of the emotions spill out, I would probably not be able to collect myself back up before tomorrow. This is the kind of moment that I reserve detachment for—when I desperately need to press the easy button, run away, dissociate, at least for now. I climbed into bed, took a deep breath, then gazed into the walls like I had so many times before. But this time, their sharp lines refused to tilt and let me escape from myself. No matter how hard I tried, the walls still looked like walls: cold, tangible, real, sealing me in.

All the panic, grief, love, and fear that I had been holding

As the pressures seem to be weighing extra heavy, I hope these stories are able to slide off the page and wrap you in a big ol’ word hug. Hang in, hang on, and a happy semester midpoint to all.

With care and kindness, Joe Maffa A&C Managing Editor

FEATURE

2 post

back all night spilled out of my heart. Somehow, I knew that I would never be able to detach again. Maybe it was the newness of the environment, the coldness, or my exhaustion that made everything that night felt like the build up to a long farewell. I got ready to clench my jaw through the nausea of disappointment, but the wave passed before I was ready. Instead, I found myself drawing in a long breath, and my body loosened up on its own accord. My emergency exit had crumbled before my eyes, but I was… relieved. Without a way to escape, I could finally stop thinking about escaping. I could fully commit to work, to bond with people, to live my life in the present, because there wouldn’t be an alternative. I don’t have to reason with myself that I actually might like sweet potatoes anymore.

So there I was, with the room enclosing me in a perfect square, while a faint, steady rhythm leaked from the faucet like a prelude to a larger symphony. My hands, made out of flesh over flesh, rested limp on the yellowed bed sheet. At this time of the year in South China, you can’t escape the clammy air or the misty rains in the afternoon, which find their ways into the palms of my hand through every damp sheet. I ran my fingers through them. It was cold and damp and real, like the smell of rain when you step out of a small airplane cabin.

My friend leaned over from the other bed. “Do you want to talk?”

This world was all I had now. There was nowhere else to be.

I nodded.

***

In the morning, I hugged many people. I hugged my friend, even though we are both terrible at hugging, especially with each other. I was still lightheaded from the previous night’s emotions, but it was light the way a willow branch is light, knowing it is connected to a trunk and roots that claw into the earth, no matter where the wind is blowing. I have lost one world, but I have this one, right here, right now. I rarely enjoy hugs, but it didn’t matter that morning, because they were my only way of telling people what I couldn’t quite put into words then: I have nowhere else to be now, but there is no place I’d rather be than right here with you.

Virginia Woolf writes that for most of our lives, we live in the cotton wool of daily life: tedious, repetitive, our senses muffled. But for a few unexpected moments, the world becomes violently clear and intense. One becomes truly present, truly awake. She calls these moments “moments of being,” a phrase that perfectly describes the embodiment that I felt that morning. It was as if I was seeing and hearing people for the first time, and as I put my arms around them, we became one solid form with our feet planted into the earth. As I held on to the hug, all the colors and words and shapes and sounds of that moment held on to me with a symphony of voices that sounded like “you are here you are here you are here.” I am here, gladly.

Flats

Life as Conjunctions

finding the and

by Marin Warshay

Illustrated by Icy Liang

It’s roughly 5 p.m. I’m plopped down at our six-seat kitchen table and observing my roommates as they begin to trickle in from their days on campus in search of food for their rumbling bellies. A symphony commences: microwave beeps, fridge slams, the click of our gas stove that has a laggy ignition.

This is the homey cacophony I yearned for when I was in on-campus housing—knowing you are surrounded. Doing mundane tasks together. Cleaning together. Existing together. Boiling water together. That’s what I signed up for in this living arrangement.

On paper.

In theory.

Theoretically.

I love it. I do.

I really do.

Right?

Yes!

Some of us come home with fresh news from the seven hours we’ve spent apart: sometimes good, sometimes bad.

No matter the chatter, the movement of the scene is what I’m enamored with. So why do I still feel unsettled in this new home I’ve fostered with some of my closest friends? Why does a part of me still long for the on-campus world I left?

+

At home on the first day of classes, I was struck with an intense feeling. Not my senior year angst, not my first-day excitement, but something else entirely. I noticed it when my roommate was swirling her rigatoni around in the saucer we found on the side of the road. Rays of light bounced onto

her feet, reminding me of how my dad used to tickle mine as a kid. I could see the orange glare asking to come in, so I quietly walked over to the window and pushed up the shade. The room was swallowed by the golden hour’s breath.

My pasta-making roommate was encapsulated in the solar glow—visibly luminous heat. Recognizable but irreplicable. It was then that I realized why our house felt so incomplete and unsettling to me.

It’s insular. It’s easy to get stuck inside. I’m quick to feel like I have everything at an arm’s length. All my basic needs are a walk away—a walk which does not require putting on my shoes. But why would I want to settle at “just enough?”

For me, home means an inside and an outside. I need time spent inside typing away on my couch in pajamas and outside warmth from the breeze weaving through grass. I’m energized by cooking with a friend and sitting alone basking in the light hitting Faunce steps. I want to sit on the roof with my roommates and smile because of the leaves falling on my head while I perch under a tree writing this.

It was entertaining to fantasize about having a home, and it’s here—so now what? I have what I wanted. But just because I have an apartment now doesn’t mean it’s the only place where life exists. I have an odd yearning for my old bed in Perkins. The chase for off-campus housing was so satisfying because it was nice to complain about dorm life. I am incredibly grateful to be living where I am. I am lucky to have the chance to do so. And, I miss campus.

I miss proximity to green spaces and running into people. The 15 minute walk from Fox Point to the green is hard to motivate myself to do, but the incorporation of both greenery and home fuels my biophilia. Humans’—and certainly my own—intrinsic love for the environment and living things has become obvious in my race to living like an adult. I never want to lose being a kid, playing in the grass, sitting under trees on the quiet green.

I have to remind myself that the word “and” is a powerful thing. Spending time soaking up Brown

“That’s why we can’t drink. Because we’re so fertile.”

“What if you killed a worm and it’s just somebody’s boyfriend.”

FEATURE

1. Ass 2. Stanley 3. Rascal 4. Earth 5. Tires 6. 7. Ballet 8. British apartments 9. -ulence 10. Chest October 14, 2022 3

♭

and the community that I’ve built for myself here is powerful. But taking time to do nothing, be alone, and acknowledge the sun’s beauty is brave.

+

It’s 5 p.m. and I walk into my kitchen. I say hello to my roommate making kale chips from our wilting greens, pull up our shade, and release a breath.

She turns around. “How was your day?”

“It was nice. Pretty busy, and I was able to rest when I needed to.”

I let the outdoors stream in and feel the comfort of merging my life, bound by “and.”

“How about you?”

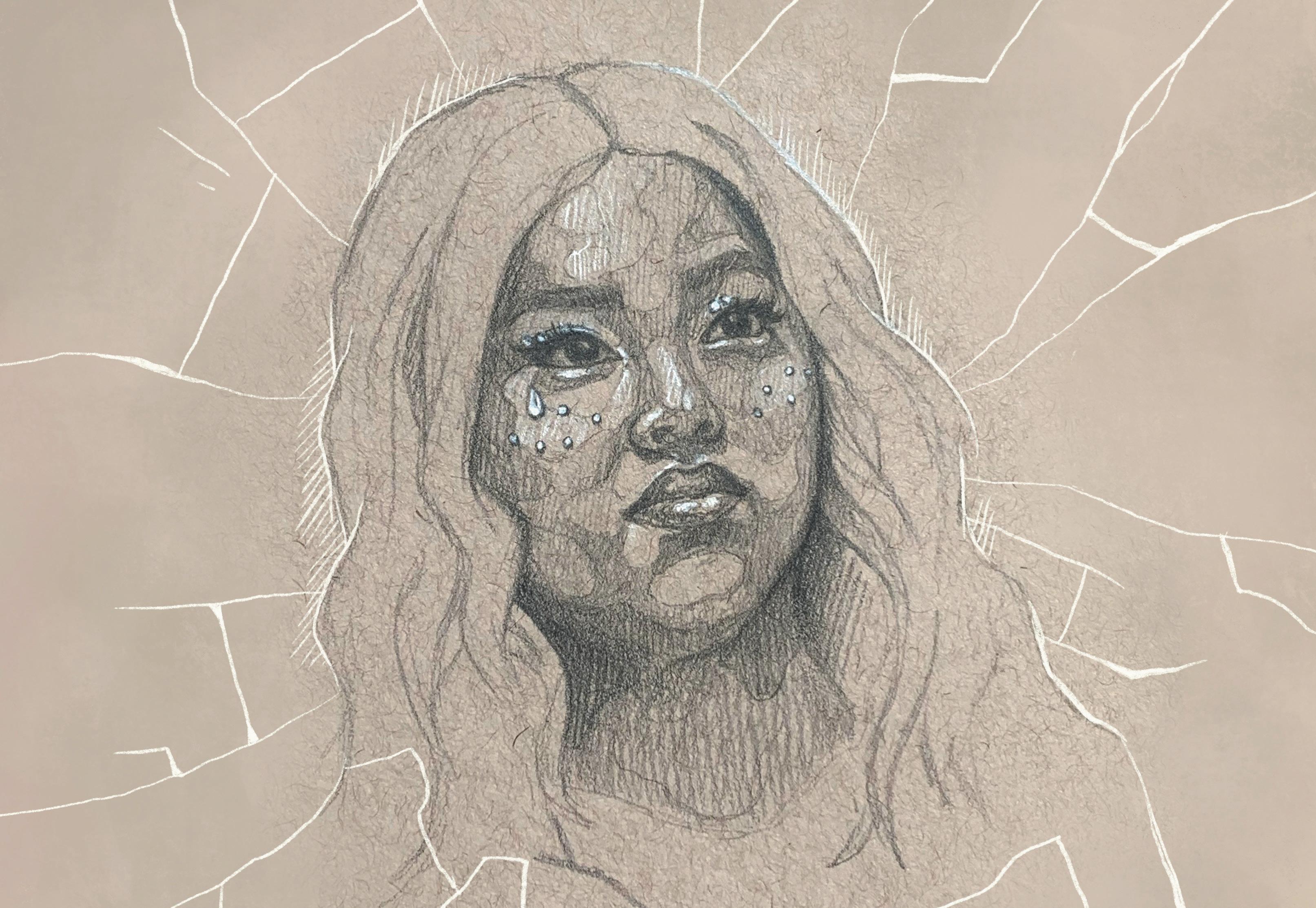

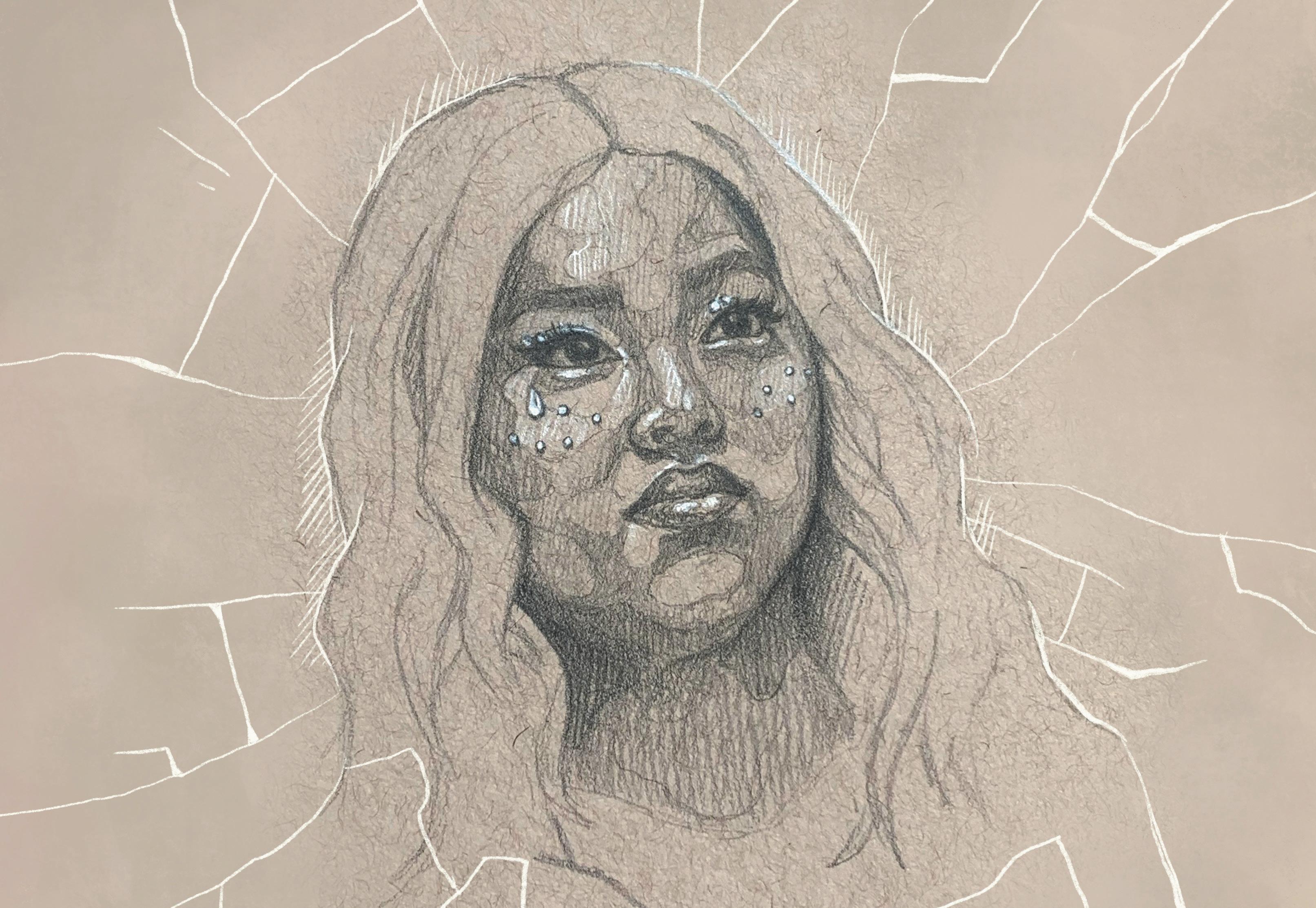

The Walls and Me a love letter to hiding places

by Mack Ford Illustrated by Ella Buchanan Insta: @nanahcube

tw: homophobic slur

There is no greater joy than to find a new place. I collect them: places to squirrel away in, places to sit and rest for a while, places to dilly-dally. There are places to watch and places to think and, most of all, places to hide.

My hiding places are often fleeting: I lose them as quickly as I find them. I lose them to circumstance, to accident, to memory. One morning, they pulled up the fire escape ladder, and now it’s just a bit too high to haul myself to the top. Last year, I forgot which stairway brought me to the little room on the fourth floor of the public library that smelled like old books and cigarettes. Two summers ago, I realized I was too heavy to swing myself onto even the lowest branch of the sequoia tree in my childhood backyard.

To lose these beloved places causes me near-physical pain. I miss them like I miss the jasmine perfume my mother wears now that I’m living far from her, or the scratchy fabric of my grandmother's sweater against my cheek.

This is one particular way to lose a place:

I was sixteen years old and sitting on my very favorite bench when a man drove by and yelled a horrible thing.

I will start with the bench. It is a sturdy bench, made of fourteen wooden planks linked in a satisfying curved formation, the sort of curve that cradles the shape of your back. The armrests are metal and always cool, which is particularly pleasant in the summertime. Over the bench looms an old oak tree. The grooves in this tree run deep, like the veins in the hands of my grandfather, who believed a man should always chop his wood by hand. The sharp

spiced scent of recently fallen acorns floats down to rest around the bench. The right armrest is perpetually sticky— maybe from tree sap or a long-ago spilled chocolate ice cream cone. From this bench, I can hear the screeching cry of a particularly obnoxious crow. He screams like someone has taken his lunch and smacked him on the head with a newspaper and he needs nothing more than for the whole world to hear his indignation. I have named him Stuart. I am very fond of him.

I like to sit on this bench in the late afternoon, because that’s when the oak tree shades the left side of the bench— the side which is just as sticky as all the other public benches in the world. By then, Stuart has exhausted his vocal chords for the day, and the wind has settled in to rest for a while. It is late afternoon and I am trying to read, only to find myself distracted by the pleasant sun, and by the thought that it is a terrible crime that anyone should have to concentrate when the sun is so bright and wide-armed.

Then a man drove by in a gray sedan and yelled at me to give him a smile, you fucking dyke.

Then he drove away.

Nothing moved except my breathing. I stared at the place where the car had been. The bench beneath me was hard, somehow tougher than it had been before. Or maybe it was just the concrete air slowly filling my lungs.

I long for these spaces where I might be unwatched, and the longing becomes a question. It asks why I would want a place that can’t be seen. It asks who is always watching. Space becomes a labor; I have to constantly move in it, move through it, knowing it cannot be mine. I try to claim it, sit for a moment, and find a brief reprieve. But it only ever lasts a moment.

To be a female, and particularly a female finder of places, is to always be watched. I am a spectacle, with men as my unbidden audience. Often, even when I am putting on my socks in the morning and completely alone, I tuck my hair behind my ears. I am always conscious of the man, the watcher, who is ever-present. He is peering through the keyhole in my own head.

These are Mary Oliver’s words, give or take a few:

Whatever a space is to the heart and body of a woman, surely it is as much or more to the spirit. I long for spaces that speak to my spirit, spaces that hide me. Sometimes these are warm, quiet spaces best accompanied by a cup of Earl Grey tea, unsweetened and lukewarm from sitting on a desk too long. At other times they are cool, dark and mossy, surrounded by toadstools and small wild things. Or they are bright and bursting with lots of windows I can see out of, but nobody can see into. I would like there to exist places that are small and snug and well-tucked in, secret and quiet and almost intangible; places that are unobservable, yet from

which I can observe perfectly well. I want to be held by a space. I want the very walls to wrap around me and press gently inward. Nobody can see me in this place. It closes its eyes and gives me a gentle kiss on the forehead.

These are the spaces I imagine. Surely such places reflect the state of my soul. There are hidden places that reach out towards me with tantalizing fingertips, and there are places that lurk in solemn silence, waiting for my hand; there are places that nudge, places that prod; there are places that hold me by my elbows and rock me to sleep, humming gently.

As my imagined places are mirrors of my soul, so my real places must contain a bit of my soul made tangible.

I am a private person. Even the thought of sharing my places, I’ll admit, feels just a bit more unpleasant than slowly peeling off one of my fingernails. For you, though, I will try.

Here is one of my places:

There is a building on the corner of Jefferson Street (even now I have changed the name so I may keep this place mine for a little while longer) that is in the shape of the letter “L.” It is a sturdy building, with tall windows and great sweeping ceilings. Most importantly, if you slip a brick in the door of this building, it won’t lock for the night.

Walk into this building, then up to the second floor. It will be dark—it has to be, because evening is the only time the building is free from crowds of students. Now, the only noise is the creaky breath of the building itself. Hear it inhale, then exhale. There is a window on the second floor that opens halfway, the only window in the building that opens even that much.

My place is just at the corner of the building, in the crook of the “L.” Outside of this window is a roof, slanted on both sides like a gingerbread house, and framed by a gutter.

If you crawl out of the window and slide down the roof to the gutter, you will be propped between the roof and the wall of the building. This little place is precarious and sturdy. I could fall from the roof if it would let me.

Here I am, with my arms braced against the wall and my feet angled down into the gutter, with my head pressed back onto shingles and the sting of almost-winter wind on my face. I am relieved, unburdened, secure, chilled and scratched, delighted. I am on the edge and Unobservable.

Beneath my hand I feel bricks. It is almost as if we share a secret, the walls and I. A drop of water falls on my shoulder from the gutter above, then rolls down my arm towards the gutter at my feet. To the water, I am nothing different from these walls that clutch my shoulders, which are brickmarked and open and clutching back.

(Inspired by Margaret Atwood, Georges Perec, and Mary Oliver)

NARRATIVE 4 post

Long Way Home

understanding love with everything everyone all at once

by AJ Wu Illustrated by Connie Liu IG: @the_con_artist

“If you run away,” said his mother, “I will run after you. For you are my little bunny.”

For a long time, I didn’t realize this story was also a love story. It goes like this:

My parents grow up in the 1980s in neighboring towns along the southeastern coast of China. My dad sits behind my mom in math class and studies the curve of her head. He chases after her all through their time in school.

My dad scribbles a poem in my mother’s yearbook at the end of high school. He sends her love letters throughout college, sleeps cold and happy after stealthily giving her his blankets on a midwinter overnight ferry.

I flip to a picture of my mother in her twenties. She is young and pretty. My dad poses next to her, squatting down on a rock and flashing double peace signs.

I flip the page and we’re by the edge of a lake on a day out. My dad skips stones with one hand while baby me in a dress swats at a butterfly as my mother holds me. She laughs at someone behind the camera.

Like any self-respecting queer ABC (American-born Chinese), I watched Everything Everywhere All at Once in theaters when it came out. It’s a dazzling sci-fi epic in the multiverse about a middle-aged Chinese-American woman, Evelyn (Michelle Yeoh), struggling to keep her laundromat open while her marriage to her husband, Waymond (Ke Huy Quan), falls apart. Her emotionally distant father (James Hong) is visiting and she is still grappling to accept that her daughter, Joy (Stephanie Hsu), is gay.

Evelyn is filled with regret because of the unfulfilling life she has led since following Waymond to the United States, while Waymond longs for Evelyn to exit the callous solipsism of her own remorse to notice him for just a few moments and remember the love they used to have for one another.

My father jokes whenever my mother is angry. It’s pathological; I think he’s physically incapable of silence. He is soft-spoken, gentle, and unhurried—everything about Ke Huy Quan’s on-screen performance brings to mind images of my own father so visceral I have to double-check to make sure he’s not here. He built the world as I knew it, steadily and without complaint.

Early days blur into nights; my dad rocks me to sleep, singing a song about airplanes in the rain. I feel safe in those first years sitting in the back of his car even during heavy storms. I play the lullaby on the piano sometimes now, trying to figure it out by ear. I can’t remember fully how it goes.

I flip to another page: the year is new and it’s cold and we can’t go home. My dad is gone. (Will return in a few days, apologetic.) My mom takes me and my little sister, then nine and four, by the hand and we wander around a Target for hours pretending that we’re looking for something.

I grow away. They do too. We take years from each other. My mother blames my failings on my father more and more. Maybe that’s where I first started to learn manhood from. She wishes I were more like her. I secretly think I am and that’s why we’re stuck pushing against one another in perpetuity. I’m stubborn. I lash out too easily and act too impulsively. I don’t know when to stop pushing. My mother and I fill any room we’re in together.

Evelyn is unable to bring herself to introduce Joy’s girlfriend to her father; she settles for introducing her as a good friend. She tries to apologize to Joy afterward and convey her love for her daughter, but what ends up coming out is, “You have to try to eat healthier. You are getting fat.” My friend and I giggle through the entire scene. Because it’s such a cliché and isn’t it such an unfair caricature of Chinese mothers that Evelyn isn’t capable of speaking emotionally to her daughter without commenting on her weight?

I admitted aloud that I was trans for the first time to a

friend and couldn’t get through it without breaking down because of the guilt. When I tried suicide, my parents’ suggestion was a Christian counselor affiliated with our church who would fix me. My mother lets me know she thinks my haircut is ugly and too short, my clothes aren’t anything like my sister’s (younger and already more agreeable), and that I should eat less because I’m putting on weight. She and my aunt text me pictures regularly of when I was in sixth grade and had long hair, look how pretty you are in this one.

“For some reason when I’m with you it just hurts the both of us,” Joy finally tells Evelyn, exhausted.

She tells me a dream she had of how she imagined I would be when she was pregnant with me. A little girl in a dress (with pockets!) sitting on the steps leading into our home, eating graham crackers out of her pockets and waiting for her mom to come home. It’s silly, isn’t it? Oh, I don’t know. I don’t tell her about the dream I have where I wake up in her body, look in the mirror, and see my own face growing in.

My mother knows the ins and outs of how to take me apart. It’s not a particularly original skill. My mother’s father wanted a son but had two daughters. He asks us to call him 爷 (paternal grandfather) to pretend he didn’t fail.

Evelyn’s father disowns her and pushes her out of their home when she decides to follow Waymond to America, “If you abandon this family for that silly boy, we will abandon you.” I watch and wonder how we let go of each other so easily.

I always considered myself lucky to have parents that made an effort to read to me. The first book we read together is God’s Wisdom for Little Girls. The illustrations are beautiful; the poems make my head heavy and warm. I love the rhythm of the words and beg my mom to read me more, but really, it’s our time together that I’m putting off parting with.

My dad stands at the side of the sanctuary passing out programs for Sunday service. I fetch bottled water for the pastor and station myself beside my dad, mimicking his stance

ARTS & CULTURE October 14, 2022 5

The Runaway Bunny by Margaret Wise Brown

with all my six years of height. I wish more than anything to be an usher too. At home, I try on his ties and Sunday suit; they’re ridiculously large.

December now. My trans friend visits me and meets my dad briefly. You can barely even tell, my dad wonders out loud before he’s even fully out the door. I hate him for it. I hate myself for hating him but more so for letting my friend face his scrutiny. Maybe I’m learning. I return home after school to all my athletic shorts thrown out because my mother was sick of them. I hide my things better. I sneak out to homecoming in a suit, change in the parking lot of an Uncle Julio’s afterward and reflect on how silly the whole thing is, go home. Everything is normal.

It gets better. Any good love story has to. Evelyn learns that her family has chosen her in every universe. She may not have succeeded in the ways she had hoped, but she has a husband who loves her and a daughter who longs for connection. She breaks the cycle of intergenerational hurt by introducing Joy’s girlfriend to her own father and telling him she no longer needs his approval. She’s proud enough of herself.

Even now, when I look at Ke Huy Quan as Waymond, I still can’t help but see my father. I’m learning that this can coexist with everything else. He was the first to call me. I’m trying. Your mom needs more time.

I fall in love with a girl. We hold hands during a bad movie and lean into one another. We run our bikes down wide roads. I hurtle after her bright back. Light rain beats

back the late-summer dust that gathers in our throats and the night turns clear and sweet. I’m slowly learning to choose and be chosen in this lifetime; there is no other. I take my time walking back home, pausing at corner stores and apartment complexes I hadn’t realized had always been there. I started to believe this could also be a love story.

I am trying to be a decent son. I ask my mother to teach me how to cook and I methodically write down and take pictures of every recipe she guides me through. I don’t want to lose any of it. The kitchen grows dark. By the window, scraps of moon blur with our white reflections. At last, as the stars begin pricking out of the sky, the pork floss rolls are tucked away into the oven.

This is not that story. But I hope it ends satisfactorily. My family is one that is messy and full of contradictions, but it’s a comfort that so is everything else. In this world out of infinite others, maybe we still have time.

It’s raining and we huddle under one umbrella. I’m standing straighter and taller than her now. She rests her head tentatively on my shoulder. Somehow it makes sense.

Now—hundreds of miles apart from one another—she asks about my classes, doesn’t ask about the things we agree not to talk about. I am afraid you are doing a lot, have too much pressure. I tell her I’m doing well, she has nothing to worry about.

She texts me pictures of sunsets. This evening, beautiful.

Last night I dreamt I jumped into the lake and waited patiently for a denouement. Two splashes.

Talkin’ Tennessee

a radical reading of broadway girls and the country canon

by Evan Gardner Illustrated by Connie Liu IG: @the_con_artist

Morgan Wallen hails from Tennessee—the home of the Klu Klux Klan, the former land of lynch mobs, and the deathbed of the Civil Rights Movement’s greatest hero—and croons endlessly about its virtues and beauty. After he famously said the N-word, his fans made him a martyr to cancel culture, saluting him as their own Colin Kaepernick. This combination of racist origins and behavior makes country icon Morgan Wallen the antithesis of Blackness. After the N-word controversy, Wallen attempted to redeem himself, not through apology, but through song: he released “Broadway Girls,” a collab with Southside Chicago rapper Lil Durk. This move was the classic “I Have a Black Friend” Moment: with streams, sales, and autotune, Wallen attempted to return to the good graces of the Black community. On the surface, this move was an epic failure. But for me, a Black man from New York City, this placed him on my radar for

post

ARTS & CULTURE 6

the first time, and ever since I discovered this track, I have not been able to shake my shameful infatuation with his work. Through love songs about home and a romanticization of what is leftover from the urban elite, Wallen appealed to parts of me I didn’t know were still healing and gave me poetics that–when analyzed using aesthetic cognitivism–hold Black revolutionary potential.

Living as a Black person in the legacy of slavery means trying to piece together who you are without a homeland. Wallen’s songs are collages of his homeland and its glory, built from the forgotten scraps of rural existence; titles like “Talkin’ Tennessee” and “More Than My Hometown” proudly communicate his propensity for declaring his origins. In the lyrics themselves, Wallen tells the story of his land and his people by encapsulating it in small representations of his culture–the kind overlooked by the gaze of mainstream media and “high culture” due to their apparent triviality. As he tells us in “Still Goin’ Down,” he is from “a town where the doors don’t lock,” a “scene a little more Podunk than pop,” and “a small town, southern drawl crowd.” He further defines this place as one in which “we’re sippin clear, drinkin beer on a Friday night,” where “every country girl got on her cutoffs,” and where they “circle up big trucks around a fire, still kickin up some dust behind the tires.” By compiling a collection of unlocked doors, weekend beverages, shorts, and cars, Wallen creates a picture and feeling of home that struck me like one of Cupid’s arrows, imbuing me with a surface-level sense of love and understanding of Southern culture, despite having never ventured below the Mason-Dixon line myself.

Through this artistic practice, I have come to see Wallen as someone who is “the same gas station cup of coffee in the morning” and whose “heart’s stuck in these streets like the train tracks,” as he describes in “More Than My Hometown.” While gas station coffee and train tracks may hold little to no significance alone, Wallen collects these overlooked items to create an identity in the shadows of the powerful. His objects are poetically valuable not for their beauty, complexity, or rarity, but instead because of how they come together to build an aesthetic, a home, and an identity out of what remains.

As Black people, Morgan Wallen is not our home. The backroads he so artfully extols are haunted by the spirits of our ancestors who hang from his beloved trees. His homeland is the graveyard of Black mothers, fathers, sisters, and brothers executed without cause or trial, and of the great Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. himself. The same land which Wallen’s art is designed to revere and preserve holds years of Black suffering, oppression, and death. Even Wallen himself is a continuation of this legacy, as his use of racial slurs demonstrates.

So, I am not suggesting that we find home in Wallen or his people. What I am suggesting, however, is that we use his poetic construction of a homeland as a blueprint to visualize our own. The way to revolutionarily consume Wallen’s music is not by praising its value as such, but rather by evaluating it through the lens of aesthetic cognitivism. Wallen himself sings, “If I’m ever gonna move on, I’m gonna need some whiskey glasses, cause I don’t want to see the truth.” “Whiskey Glasses” is a double entendre; he needs glasses of whiskey, but he also needs his whiskey to function as glasses. The second meaning is the relevant one here. Just as whiskey glasses are an alternative way to see the world that is instrumental to Wallen’s healing, Wallen’s poetic devices can be valuable to healing African-Americans as a lens through which they can visualize a path forward. I am not praising the racist country music canon, but rather speaking of the potential power Wallen’s poetics hold

for the Black listener to use it as a locus to open up their own canon.

The imagining of a Black homeland is nothing new: Negro spirituals and Afro-Futurism are two Black art forms that used this sort of creative process to bring us closer to freedom. Both mediums were created in an oppressive society, yet used a cultural imaginary to produce a supernatural world in which Black freedom and homelands could be considered. This kind of psychic transformation holds the secret to revolutionizing oppressive art like Wallen’s: we can use Wallen's poetics to construct our own homeland in the midst of his oppressive one. I am not saying we should ignore Wallen’s problematic ties; instead, I am proposing we actively fight his oppression using his own devices.

This artistic transformation is powered by a weaponization of the leftover. Negro spirituals imagined a Black future, but they were written as part of a religion created when enslaved people turned the slaveowners’ oppressive Christianity into their own source of community and rebellion. Just as Soul Food took the remains of the masters’ meals and made a culture out of it, the Black church took the leftovers of oppression and made it revolutionary.

Thus, we must engage in a similar transformation of the leftover with Wallen to take his work from racist to revolutionary; fortunately, the listener can learn this practice from Wallen’s aesthetics themselves. His imagery of the homeland grows out of everything that has been left behind–by the American elite, or by a woman. My favorite Wallen song, “Sand in My Boots,” illustrates the poetics of the leftover perfectly: it is the story of a summer fling in which Wallen shares a perfect night by the beach with a woman whom he tries to bring back to Tennessee, hoping to share its beauty. Wallen believes that she will meet him before he departs for Tennessee, but she does not, leaving him to reckon with this heart-wrenching contradiction: for “something about the way she kissed me tells me she’d love eastern Tennessee, but all I brought back with me was some sand in my boots.” Wallen captures his love, his desire, and his heartbreak, into the image of sandy boots. This almost-love story is compelling as an example of Wallen’s poetics, but it is even more powerful when considered as an artistic endeavor: Wallen is taking the leftover–his unrequited love represented by the remaining kernels of sand–and spinning it into an art piece in order to heal. He creates a narrative that is as much a love story as an ode to his home out of the leftover pain, and this creative process is regenerative.

If Wallen can use an artistic transformation of the leftover to heal from a one-night stand and to charge $400 a seat at his show, one can only imagine its potential when weaponized for the African-American revolutionary canon. Just as he turned “a parking lot into a party” with a reclamation of the small forgotten details in “Up Down,” the Black listener can turn an oppressive country canon into their own revolutionary one via the same aesthetic cognition. Most enjoy Morgan Wallen for the masculine drumline or the gritty guitar, for that is who he is, but someone who listens to songs like “Sand in My Boots” with the cultural imagination of Negro spirituals and AfroFuturism can also use his poetics of a homeland built from the remains of the powerful as a way to heal. While Wallen’s aesthetics of beer, trucks, and whiskey may represent oppression and “low culture,” it gives me a strong emotional response, which is precisely the role of the artist and the revolutionary. Emotion spurs radical change; thus Wallen’s love of the home—a radical emotional leftover from a scrawny white boy hailing from the backroads of racial oppression—is a potential tool for Black revolutionaries.

Of Wind and Fall Layering

by Sean Toomey

Illustrated by Grace Pinsonault

Fall is really flying by, thanks to the universe deciding to jump from summer breeze to winter gales (with a little help from a hurricane), and I bet some of you are freezing your asses off. The wind is blowing, the rain is pelting, and you are caught on 45 degree mornings wearing sweat shorts and another university’s hoodie (tut-tut). At some point, your streak of rotten luck is not the weather, it's you. Luckily, here’s a little guide on how to layer, from the bottom-up, inside-out, and with some style (not pointing any fingers but many of you need it).

Underlayers:

For the uninitiated, underlayers are anything you can wear underneath normal, everyday clothes. A flannel shirt, tights, any thin trousers that fit underneath some loose pants might come to mind. For the skiers and northerners among us, you’ll recognize these as long johns. These generally come in polyester and cotton mixes, with some high quality ones coming in merino wool. Underlayers will keep you warm, but depending on what else you’re wearing with it, they may have you sweating out the Narragansett Bay, so save these for extremely cold days or when you're feeling sweater averse.

Shirts:

You can basically do anything with shirts as long as you’re not wearing an untucked pirate shirt three sizes too big (though I suppose…that could be okay too). The complex part of this freedom is actually making all your wild shirt dreams come true and not look like a costume mixing experience gone wrong. Generally, a buttoned shirt will be your go to base layer for the fall and winter seasons. These can come in a terrifying variety of styles and patterns, but to start out, I would recommend a solid color or quiet-patterned cotton button up in white, blue, or checkered (please no gingham, and no, I will not elaborate), and a more vibrant color of your choosing. I would also recommend a flannel or two in any pattern. These shirts are going to be the base layer under your sweaters and sport coats so making sure the colors match is of prime importance. Color match doesn’t have to mean that they are in the same corner of the color palette (e.g. light orange with a lighter orange), I personally recommend trying to get a good contrast with your shirts: Think white shirt and navy blazer/sweater.

Sweaters:

These are your bread and butter. There’s a reason they call this sweater weather . Sweaters are one of the big statement pieces that your outfit can be built around and, because of this, there are fewer rules and guidelines about what colors and patterns to follow. Crewnecks, V-necks, turtlenecks, and polo-necks are all acceptable styles to wear out. Shetland crewnecks in dark fall colors like red and green, and chunky navy sweaters of all varieties will always look good, just make sure to match the color with your button-ups. When it comes to material, a wool sweater will be warmer than a cotton sweater, but cotton will still do the job well.

Blazers and Sport Jackets:

Tweed is king here. There is little more to be said. Blazers of any color are good as long as the patterns mix

ARTS & CULTURE October 14, 2022 7

correctly (remember: contrast is good) and navy will basically go with anything. Tweed blazers, however, are the language of fall and, provided they fit, will flatter your figure and make your sweaters pop underneath. It’s that chic-Ivy-professor look everybody and their mother has been trying to go for since Beau Brummell went crazy and Tom Wolfe died. Trust me, you want tweed. Grays and browns in herringbone, houndstooth, and glen plaid will be the most common and will look the best with your layers.

Pants:

Please for the love of Bruno (yes I invoked it), no skinny fit—that ten-year moment is over. What you’re going to want for the coming seasons are warm and dependable pants that won’t stick to your leg like you got dipped into Willy Wonka’s chocolate river. Wool flannel pants, chinos, and (on occasion) jeans will all work fine. Wool pants should be your winter staple as they’ll keep you warm and look good at the same time. I recommend varieties in gray and navy blue—they’ll go with everything in your wardrobe while adding flair. If you’re adventurous and are trying to go for the 1930s struggling author look (like me), try getting wool pants with pleats and high waists to go all in on classic silhouettes and incomprehensible manuscripts about train station platforms. Chinos will always serve you well, khakis being the easiest to pair with

the previous layers mentioned, but some explorations into fall colors like burnt orange and green can also be worthwhile, provided they’re paired with the right pieces. Jeans are jeans and to keep up with the theme of impressing your parents, try to pair them with more casual layers.

Coats:

The function of a coat in the colder seasons is to (1), keep you warm and (2), make you look cool as hell. The right coat can make an outfit go from good to great and consequently the wrong coat can make an outfit look wrong or in between styles. Generally, it's always a safe option for your coat to be contrasting with the rest of your outfit–a dark coat with a light outfit, a light coat with a dark outfit–but similar color layering is possible if coordinated well. There are many (headachingly many) different styles of coats but to keep things simple I’ll differentiate between single-breasted and double-breasted coats, which refers to how many rows of buttons there are on the closure of the coat. Single-breasted coats will look sleek and generally slim your figure down at the cost of warmth and dramatic wooshiness. Double-breasted will keep you warmer, look more formal, and generally add a broader edge to your figure as well as giving you the ability to layer more underneath. It’s a matter of preference but I recommend a double-breasted coat

for their classic look and warmth. Good materials to look for are wool, tweed, cashmere wool, cotton gabardine for rain, and camel hair. Navy coats and tan coats are good starting options as they can go with most of everything but under no circumstances should you ever be wearing a single-breasted tan overcoat. Never.

Accessories:

Lastly, it is important to remember all the little accessories you can pair with your outfit to really make it pop. Bright scarves, socks, and hats are the finishing touches that can add some personal style to your outfits of solid darker colors. They're also good for keeping you warm in the Providence winds if, like me, you sometimes forget you live in the real world and not a Polo Ralph Lauren ad. Cashmere is always a good option for warmth and comfort as well as providing a luxurious flair that might help more casual accessories from slipping into grubbiness.

Hopefully this guide will help you find the right way to layer in the coming cold and not freeze half to death on the way to class. Remember: tweed is your friend, contrast is good, look smart on parents' weekend, and always check the wind speed before getting dressed in the morning. Good luck out there everybody, stay warm and stay stylish.

LIFESTYLE 8 post

Surviving Sick Season

by Nadia Heller

Illustrated by Lucid Clairvoyant

IG: @l.u.cid

IG: @l.u.cid

NOTICE: The recommendations in this article are NOT from a professional doctor, a pre-med student, or even someone who remotely comprehends biology. The following “facts” are based on an English concentrator’s own experiences for remedying sicknesses. She is not to be held responsible for worsening conditions OR speedy recoveries. The reader is advised to “take it or leave it.”

For me, Sunday is the day that gracefully dovetails the weekend into the workweek. It’s a day for the soft smell of laundry detergent to waft through and linger in every corner of the house and for the mop to address the wooden floors. It’s my day for inky newspapers and lazy 2000s songs. The generous hours belong to me, my bed and, perhaps, a walk to an expensive latte.

On this particular Sunday, the last restful day of September, I woke up a monster. I usually wake up rejuvenated on the brink of the afternoon to the sun sifting through the cracks of my blinds—but this gloomy Sunday, every bone in my body ached and shivers snaked from my shins to my fingertips. I was freezing but also

“So, now, I take books to the pool, let them have a look at the sun, and smell the sunscreen. I hope they will absorb it all, so that when I open them again, I can read myself in the in-betweens.”

sweating. My head pounded against my pillow and my nose leaked like a broken faucet.

When I finally found the ability to move, I rolled out of bed and unfortunately caught my reflection in the mirror. My tan from summer’s kind sun had vanished from my face and left me with a ghostly complexion. My eyes were covered in a thin layer of mist and my lips were cracking all over. The bestowed image was a humbling revelation. After being mortified by my new appearance, I had no choice but to get back in bed and hide from the rest of the world.

For five days I laid in bed with a fever that jumped over the hundred degree mark. When day three rolled around, I decided it was time to get better.

I started with chicken broth.

I know what you’re thinking: “Nadia, you’re vegetarian!” While it’s humiliating to admit, desperate times call for desperate measures. When an itchy, prickly, thick substance shuts your throat and stops the passage of any food from your mouth to your poor, hungry tummy, chicken broth is the only solution. Not only is hot soup an affordable massage for the esophagus, it’s also delicious. I drank the entire carton in one day. I devoured it shamelessly, eating it with a spoon and drinking it in a cup. Whether it was the chicken (rest in peace) or the broth, something in that carton magically improved my unnamed illness.

A friend of mine gave me a piece of advice that I turn to for every illness. When you’re sick, the only way to get

better is to sweat it out . Before getting into bed at night, I put on two pairs of pajamas and sleep under multiple heavy blankets. You might overheat and you may wake up in your own little swimming pool but trust me the way to GET it out is to SWEAT it out. I don’t understand the science behind it but I believe it has something to do with the perspiration washing out the evil germs. It’s gross, I know, but winning the big war includes losing some smaller battles.

On day three I noticed that coffee, which I thought would give my body the energy to fight my illness, was actually just dehydrating me. Instead of charging my immune system with the spark to hop into action, the caffeine chose the side of my sickness and helped it to fight against me. So giving caffeine a rest for a few days when you are sick could really lessen the stress your body undergoes.

Getting sick in college is as inevitable as the sun setting. The relationship between sicknesses and colleges is a modern day love story—especially on Brown’s campus. As I write this article, a week and a half after my last ailment, I find the familiar stuffiness crawling into my nose and the tiredness settle onto my eyelids. At this point being sick is almost a comforting feeling. And while I will engage in the boring practices of drinking water, sleeping tons, and taking my vitamins, I will also chug chicken broth, sleep in fourteen thousand layers, and lay off coffee for a day or two. Hopefully I’ll be better in no time.

NARRATIVE

SOCIAL

“I didn’t want to stay inside, so I laid on the dewy grass, wetness seeping through my sweatshirt, and watched the sky. It opened after a few minutes, offering clusters of stars, patterns of the Big Dipper, Orion’s Belt, the bluish hues of the Milky Way against a velvetnavy sky.”

—Grace Layer, “Far From Home”

Nélari

COPY

LIFESTYLE Want to be involved? Email: kyoko_leaman@brown.edu!

—Julia Vaz, “Home” 10.15.2021 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Kyoko Leaman FEATURE Managing Editor Alice Bai Section Editors Addie Marin Ananya Mukerji ARTS & CULTURE Managing Editor Joe Maffa Section Editors Katheryne Gonzalez Rachel Metzger Copy Editors Eleanor Peters Klara David son-Schmich Indigo Mudhbary

MEDIA HEAD EDITORS Kelsey Cooper Chloe Zhao Tabitha Grandolfo Natalie Chang LAYOUT CHIEF Alice Min Layout Designers Alice Min Angela Sha Caroline Zhang Gray Martens

Managing Editor Siena Capone Section Editors Danielle Emerson Sam Nevins LIFESTYLE Managing Editor Kimberly Liu Section Editors Tabitha Lynn Kate Cobey HEAD ILLUSTRATOR Connie Liu

CHIEF Aditi Marshan STAFF WRITERS Dorrit Corwin Lily Seltz Alexandra Herrera Olivia Cohen Danielle Emerson Liza Kolbasov Marin Warshay Aalia Jagwani AJ Wu

Figueroa Torres Daniel Hu Mack Ford Meher Sandhu Ellie Jurmann Andy Luo Sean Toomey Marlena

Brown

Ariela

Rosenzweig

Nadia

Heller Sarah Frank

10.5.2018 October 14, 2022 9

IG: @l.u.cid

IG: @l.u.cid