post-

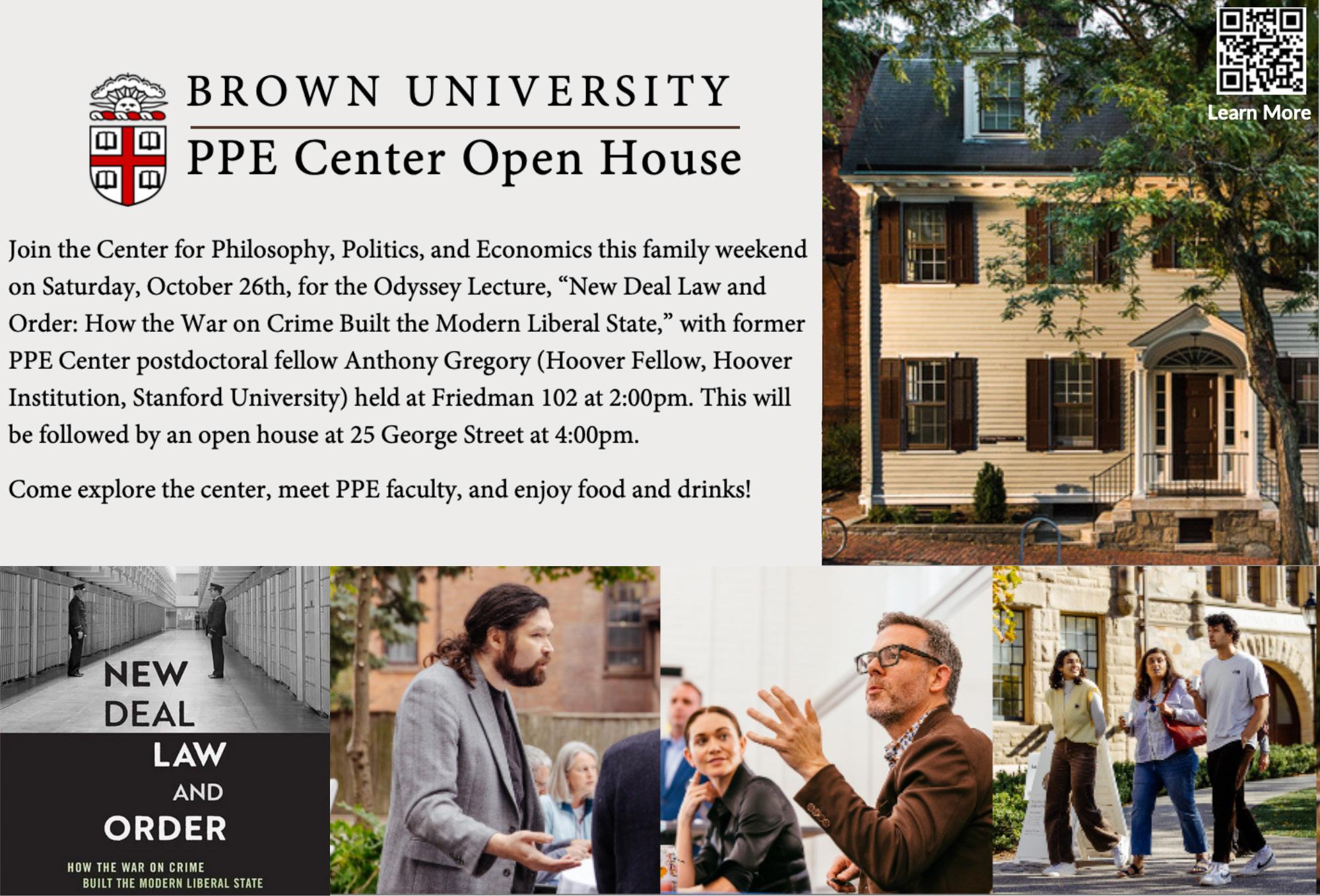

Déjà vu floats among us today. At the top of my mind is the fact that this is the fourth, fifth, tenth time that I’ve sat down to write about my family this year. In an attempt to reconnect with the literary half of my brain that had been exercised solely on Wednesday evenings for the past couple years, I embarked on a journey into two writing workshops this semester— for those keeping track, that is two more writing workshops than I have ever taken in my life. One of these deals exclusively in weaving stories about those who we call family, the traumas that break us apart, the ties that bind us together, and most compellingly to me, the way that these relationships flourish and buckle when they are exposed to a reader’s eye. The main takeaway from today (perhaps an obvious one): it’s really hard to write about family without writing about other people. The ethics and morals of writing about other people is such a weird and wonderful web

journey, from the rickety rails to the music her brother introduced to her. Lifestyle writers Nina and Michelle explore what it means to care, respectively sharing their love for letter writing and hugs, intimacies that communicate worlds and pierce deeply. Finally, postpourri is focused on definitions as Rchin interrogates the meaning of bread and how communities form around these arbitrary distinctions.

This task, capturing the beautiful nuances of the people that shine so brightly in our lives, is no easy feat, yet it remains a noble one. It’s what I love so much about post- Magazine, this family that I’ve had the honor to call my own during my time at Brown. I’m feeling an extra special helping of déjà vu today as we print our first full edition of the magazine since the pandemic first disrupted our operations. The post-ghosts of yore—all of my brave and inspiring former EICs (shoutout Olivia, Kyoko, and Kimberly!), the animated, dynamic editors that taught me what community looks like, the writers and illustrators that have bared their souls to the world every single week—look upon us favorably today. This is the family that has created this tangible capsule of our hearts and minds that we can pick up and cherish and share with our friends and share with our family and request back and fold and bookmark and frame and read again and again and again. I implore you to do all of that and more with your very own copy of post-.

to be tangled within; how do we reduce these intricate, complex, vibrant people, often those we care the most and know the least about, to characters in a story?

It’s a challenge that our writers are brave enough to take on this week for our special Family Weekend edition. In Feature, Alissa thinks through the places she has called home and nesting instincts, the avian desire that overtakes us and urges us to share our homes with others. In Narrative, Benjamin introduces us to his grandparents through a trip around Providence—a juxtaposition of his origin and where he is now. Meanwhile, Emily’s piece shares vignettes of Hawaii, the paradise that us mainlanders know as a vacation spot but she knows as her home. In Arts & Culture, Isa reflects on her mother’s love that she inherited and which has blossomed into an innate desire to look out for others. In the other piece, Eleanor catches the train and hears all the sounds of this

Part of the family, Joe Maffa Editor-in-Chief

BY ALISSA SIMON

ILLUSTRATED BY ROKIA WHITEHOUSE @SATURNKT14

For thousands of days, I have woken to birdsong. The street where I grew up is flush with trees, some a century thick, that provide home to robins, cardinals, house finches, and mourning doves cooing in the blue-black of early morning. These birds scatter in my wake on morning walks. They snip at each other on telephone poles and build nests in porch eaves and tree branches, out of paper straws, mud and twigs, and fine threads of plastic. In the summers, fearsome storms come rolling in the afternoons and blow these careful homes to pieces. I’ll find bits of newspaper and feathers in the gutters. I’ll notice when nests go missing and when they reappear a few branches higher.

I love to watch the rain, to rush to the rocking chair by my window and curl tight as the sky darkens and trembles. I love listening to the sound of birds’ caws quivering up, faster and faster, and marvel at how they can possibly live like this— constantly rebuilding, not knowing when the next predator or lightning strike will come. I don’t understand how they can keep laying eggs in the wind’s path.

***

It is the end of my final summer before senior year, the last one clearly defined by the bounds of school on either side, and I am watching robins with my brother.

Mount Pleasant, with its stony green slopes and abundance of porches, is the kind of neighborhood that makes you forget you are in the heart of DC proper. After spending my childhood witnessing my brother shuttle between schools up and down the coast, I’m still not used to thinking about him in one place. But now he has settled, a soft-nosed labrador and two small children tying him to this house for years and years. Now I am the one who comes and goes.

My sister-in-law flits past us—a flash of blue linen and dark hair. She produces object after object from her endless canvas bags, affixing small, neat labels in brown masking tape to diaper bags and pantry goods. My brother laughs goodnaturedly. She’s nesting. A fluttering of limbs, sticks and cloth, clean pillow cases, and ceramic plates.

I watch her as my brand-new nephew grows heavier by the minute in my arms, his small red hands, his socked feet, his open mouth all arching into one long curl before settling into an empty sleep.

She breezes by me—moving quickly for a woman two weeks postpartum—and I can’t imagine what could possibly be so urgent. Their home is already perfect. The living room is flushed with lamplight, my niece’s fairy wings are tucked neatly behind the front door, and the crib upstairs smells like new wood.

***

We signed our lease for senior year almost a year ago, in September, with months of dorm living left for us to daydream about what comes after. On every run through Fox Point, every icy trek back from Coffee Exchange, I would spare a glance for our home, not yet ours, and let myself imagine fresh flowers kept in a vase on the desk and shelves filled with small tokens: my rings, ceramic dishes, books.

It was the daydream of homemaking, of presiding over dinner parties and watching movies on a real TV, that enchanted me. Spoken to my friends, it felt like a promise. Something firm to hold onto as the end of our Providence years began to sharpen into focus.

***

I didn’t know what to call the impatience, the sharp

desire to return to a home I hadn’t lived in yet and prepare myself forthe year to come, more intense than any year before.

I thought of my sister-in-law, determined to overhaul her entire pantry in the early days of motherhood, and the word that my brother had diagnosed her with. The nesting instinct—a little bit science, a little bit folklore—describes the urges that strike new mothers to build out their homes, to organize, clean, and make ready for babies to come. Dozens of blogs (ones with words like “bump” and “momma” in their title) list the side effects of nesting in late pregnancy—including intense bursts of energy and a desire to stay rooted in the house. The American Pregnancy Association explains that expectant mothers should not be surprised “if just being home takes on a new meaning.” Like geese or crows, we scout for the perfect location to build nests. We flock tightly with the people we trust, seeking safety.

The entire premise of nesting in pregnancy is slightly suspect, rooted in essentialized preconceptions about female biology and motherhood. But there’s something about the idea that sticks with me, a birdlike charm that is difficult to shake: the desire to burrow in, to make foreign territory into a home fit for growing.

***

My first night of senior year is a hot, strange one. I cross the threshold of our sprawling Fox Point apartment into a maze of unidentifiable smells and broken furniture. The grand ceilings that let in so much sun during the daytime have turned cavernous in the dark; the rooms are full of shadows and my imagination is wild. I force myself into sleep and dream the vivid dreams of a new bed. It isn’t until after the third fitful night that I recognize the feeling of waking up.

One by one, my housemates arrive like pigeons to roost. We are giddy and a little delirious from the heat and the stink of dust and bleach. I want to feed everyone. Simple things— waffles with peanut butter, apple slices, eggs and toast.

For a week, all we do is clean, the hems of my jeans soaked through with soap and water. My knees chafe from hauling furniture, scrubbing at kitchen shelves, working with utmost concentration until my armpits and calves and temples sting with sweat. Feverishly, I imagine my sisters felt this way in their pregnancies, driven to build dressers and reorganize pantries with a fanatical devotion, feeling children on the way. Immediately, I cringe at imagining myself anywhere close to motherhood while eating toast off of a paper towel.

Still, I am grateful for it all. I know that these are precious days—nesting days—before paper deadlines and 9 a.m. classes and job interviews. The most pressing tasks are ones that can be accomplished with bare hands and bottles of bleach and car rides to Target and Savers. Slowly, the strange dishes in the cupboards become our dishes. We chip the edges of counters, smudge mirrors with our fingerprints, and fill the kitchen with the smells of coffee and salmon and sweet potato. We sleep on clean, hard-earned mattresses. We leave our shoes by the door.

home, even when she felt it was inelegant or unmade. I wanted to imitate nearly everything she had done, to roll up my sleeves and love my friends with clean bathroom floors and recycled shopping bags and mugs of tea, the way she loved me. ***

I was never good at that kind of stuff, my mother mused every time we left my brother’s. She was talking about nesting, about my sister-in-law’s perfect house and expert hand. It’s something some women just have a sense for.

Maybe I also should have told her about birds, perhaps the most capable homemakers in the world, and their dwellings that are as wild and diverse as the species themselves. Robins build their small, careful nests low to the ground, cleaning religiously and sounding sharp calls whenever an approaching predator threatens them. Bald eagles return to the same nests year after year, laying pounds and pounds of grass and wood atop each other to create a stronghold for their massive eggs.

September is slipping by and the dark comes a little quicker now, with a little more bite. When I turn towards home in the evenings, the streets of Fox Point unfurl before me, triple-deckers filled with yellow light and the sounds of cooking.

I’ve been thinking about my littlest nephew again, how he will grow up with his whole childhood sprawling out from the walls of my brother’s house. He will know the trees and robins outside his bedroom as well as his own name.

I don’t know where I will be in nine months. Our apartment, stripped back to its bones, will be a place that we

“Talk amongst yourself while I tackle and brutalize the technology.”

“It's like I'm the benchwarmer for the polycule.”

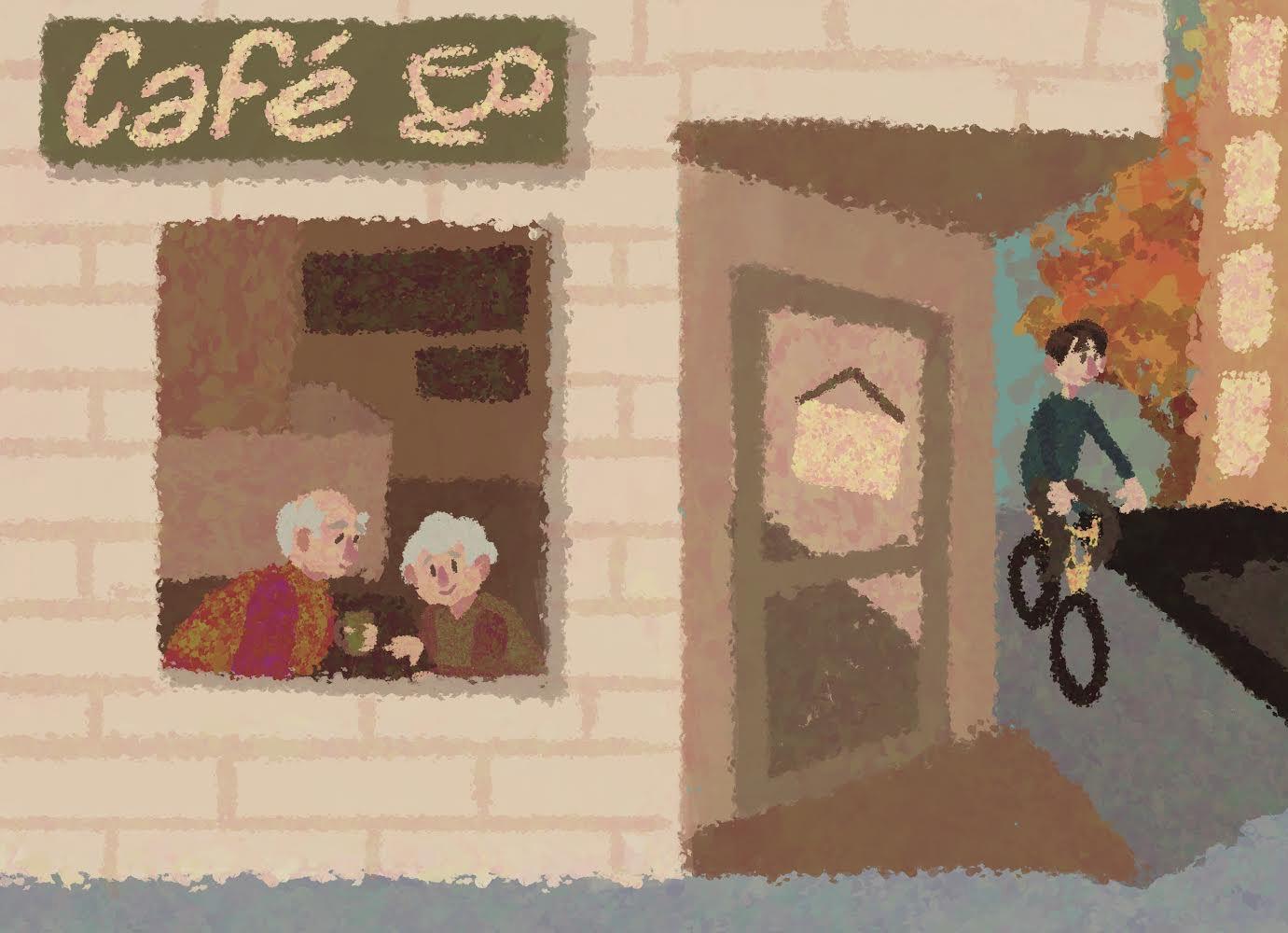

BY BENJAMIN HERDEG ILLUSTRATED BY DINAH BIGA @DINAH_DOES_ART

My grandparents came to Providence last weekend. Truth is, I was scared to see them. On Saturday, they had said they would drive through on Sunday, so I cleared my schedule

When I'm at home, they live next door, so I see them almost daily. Yet, each day they seem slightly different: their voices slower, their hair thinner, their smiles larger but with less reason. The years delight and age them. The last time I saw them was summer—if one day makes a world of difference, what about September? And what about my grandparents, the faces I have missed for weeks?

I was not sure where they were coming from. I just knew they were heading home. I rode my bike to meet them downtown. I had no idea if they came out of their way to meet me in this hillside, brick-red city. I wondered about the length they came to see me and the hour they saved to forfeit—they built their lives on sacrifice so they should never have to wait, yet they still remain so patient. I biked as fast as I could. I knew they would be there before me.

What does family do when the youngest hosts the oldest, and he learns to hold their hands? My grandparents said we had one hour. Then, they would go back home.

If we only had one hour, how much of that time would I need simply to readjust to their faces, more creased than when

I saw them last—how much time would they need to refocus on mine? I feared that us getting to know the people we had become would eat up our whole hour.

I hurried down Williams Street, pedaling at near-flight speeds. The moment I saw the coffee shop, my grandmother was visible too. She waved a wave I recognized from movies: My love is coming home! But never had I imagined that my grandmother would do it to me.

The hill's momentum was enough to carry me all the way to our home. I braked fast before my grandmother, careful not to cross her shadow, as fragile as her frame. How long had the past month been for her to shrink to the height of my torso? When she said hello, I shrunk a little too.

Every time I see my grandmother, I know how much older I seem. I know I am much closer to being a stranger than the last time I saw her. I know I haven’t thought of her or called her as much as I should have. But for her, it is enough. Biking five minutes when she had driven many miles was enough. And when I saw her, I felt the youngest I had ever been.

I looked at her eyes and followed her gaze to the café's floor-to-ceiling window, past barstools and pastries, and to the line and my grandfather's age-spotted, balding head. Good grief, she said. He's been in there a while.

She went to stand on the street corner, watching

the bikes speed by, their riders wearing shorts and shirts, stretching summer past its prime. The lengths that people go to stretch a finite time! September was over with, and my grandmother knew it but said nothing; she looks at my grandfather and says nothing. She only smiles.

When I walked inside, I heard my grandfather arguing with the barista. I ordered a croissant, but he called it a scone. I said it was not, but it was funny of him to joke. He asked whether I thought I was in Paris or Providence. At least, I think he knew we were in Providence. He often says one thing when it really is the other. He leaves us wondering.

They asked if Providence is liberal. They asked if I have a boyfriend. They asked if I am studying too hard or going out too often or enjoying this incredible city of which they have only seen a side street.

They recalled a time when they were going to move here. But they have forgotten why. How mysterious our relatives become when they're old, when their most valued memories are fading. Do we, the young, have lives to live and the lives of others to hold?

We finished our coffees and stood up to go; they wanted to see the river. My grandmother was anxious about time: our hour was halfway up. But she held the hand of my grandfather, as they followed my steps in my shadow. We traced the edges of the river.

They stopped at every statue; they glossed over all the plaques. At every spot where the light looked different, we rested for a breath.

Somewhere around the block along the east bank of the river, our conversation moved from asking questions to discussing plans. And in mentioning the future, we made it all of ours, which made time ours too, as it hadn’t been at the start. The time of reintroducing ourselves gave way to spending time. I knew them once again.

But as it happens with completion, the feeling of being whole, something falls out of place that was too much for the world to hold. My grandmother checked her watch, her smile bearing a new, heavy weight, about to fold. They were so delighted to have come. I felt exactly the same. It cost nothing to clear my schedule; it cost nothing to bike five blocks; it only cost an hour that would have just been one of mine.

Then, we walked back over. The weather was so nice. The leaves were changing day by day, and falling faster to the streets. I mounted my bike to go; they found their car to leave. I must have looked so young to them, to have my own city.

BY EMILY TOM ILLUSTRATED BY ROSA ZHA @ZRGZZZZ

Here’s the thing: I left home to become a writer and now all I want to write about is home.

But before I tell you about that, I must tell you about the Night Marchers, the way they circle the island like the beads of a broken necklace. Hundreds of years ago, they chose to leap from the Pali before the enemy could take them. Their heads opened against the rocks like roses. They are no longer warriors, which is to say, they will not hurt you if they don’t have to.

But before that is the Pali. One summer we drove to the Pali and our car broke down on the highway because we angered the goddess on the other side. I didn’t think I had pork in my car, but now I’m not so sure. And besides, the goddess is not always angry. But if you see her on the side of the road, her white dress billowing like a memory, the hem hovering above the asphalt, you will stop for her. You will take her wherever she needs to go until she decides she is bored of you.

I must tell you all roads lead to the same ocean but not all oceans are the same. Every summer, my father takes me to the bay where he nearly drowned as a boy. We watch a seal slip through the water like an afterthought. In shallow water, he shows me a fish holding another in its mouth, two pairs of eyes turned up as if in prayer. All the while an eel stares at us, yawning. I sit on the sand and watch my father swim beyond the wavebreak.

I must tell you I have never been a good swimmer. I have never trusted myself enough. Before I came back to the mainland, though, I loved jumping from the rocks into the water. We had to swim out, then climb with slippery fingers, and suddenly we were high in the air, and the ocean was flat as glass. I watched the waves roll in, gentle as breath. I jumped with the tide. This was how I learned I am better at falling than

staying afloat.

I must tell you I’ve never seen a group of boys happier than when they were throwing rocks. We were in sixth grade. It was a class camping trip. There was a beach and a zipline and a ghost story told around a fire. We kept the lights on past ten, and one of the chaperones yelled at us for it. The next morning, before breakfast, a group of boys stood on the lookout above the beach and threw rocks at the crabs below. They stopped when they finally hit one. Its body turned inside out. The boys went quiet and left for breakfast.

I almost forgot—I must tell you about 7-Eleven Spam musubi, the kind my dad and I always buy on the way home from the beach. Saimin from Zippy’s, the first meal I eat once I’m off the plane. Spicy ahi poke from Foodland. Manapua from the shop across the street from the radio station. Loco moco from Rainbow Drive-In. Malasadas from the Leonards truck at Koko Marina (my favorite). Malasadas from Agnes Bakery in Kaneohe (Dad’s favorite). All the things I didn’t know to crave until I moved halfway around the world.

I must tell you we were always told we would leave one day. Our parents fed us this notion the way they fed us Spam and rice. We talked about college as if it were a pilgrimage. The mainland, we were told, is where we would find success. Whatever we wanted to do, we couldn’t find it at home. The island was too small to hold all of us.

I must tell you this island will always be big enough for those who do not live there. My sister and I drive through Waikiki, yelling through the windshield at a gaggle of sunburnt tourists jaywalking across Kuhio Ave. Move, I shout. I will run you over, she says. And the whole time we are laughing because we know they can’t hear us, as if there will ever be a time we no longer have to stop for tourists.

I would tell you what it means to live in a place that other people see as a destination, but I’m still not quite sure. All I know is the way it felt to watch the fires on the news, listening to the journalists describe charred bodies in the streets. The way my mom spent an entire day calling her friends on Maui to make sure they were safe, the panic in her voice when she couldn’t reach them. The way people posted photos of family members on Facebook: My uncle lives in Lahaina, has anyone seen him? And beneath that, a photo of a blonde woman lounging on the beach: My honeymoon spot is gone :(

I must tell you how I felt like crying, watching Front Street burn over and over. I told my dad so, and he said, Of course you feel like crying, this is our home. But a few weeks later, when I was on the plane to Boston again, I thought about all the people stuck in hotels because they had nowhere else to go, and I wasn’t so sure.

I must tell you my parents work for the airline. The pandemic was the first time I saw an empty beach, and it was also the first time I thought my parents might lose their jobs. As much as I hate the way haoles have turned my home into a destination, my family’s livelihood—my livelihood—relies on that perpetual image.

I must tell you that I am from Hawai‘i, but I am not Hawaiian. I don’t know how it feels to have the land taken from me. I don’t know how it feels to fight for it back. All I know is that, although this land was never mine, it is the one that raised me. It is the only thing I want to write about. I’m turning my memory into mythology for you.

But before I say any of that, I must tell you that the longer I spend trying to explain my home to you, the further from home I feel.

BY ELEANOR DUSHIN

ILLUSTRATED BY ANNA NICHAMOFF @MOSSMILKSHAKE

Every holiday, I take the same train home. Even though I live in a tiny town, the Amtrak stops 12 minutes away from my house. I know all the stops along the way: New London, Mystic, Westerley, Kingston, Providence. Something is a bit different every time—the snow is fresher, more trees have fallen, the glass on the street lamps is a bit foggier—but it’s still the same place, the same route.

When I say that I’m from Connecticut, I’m often confronted with the fact that, to many, my home is just a space in between. It’s nothing more than a bridge between New York and Providence—a hellscape of traffic with nothing to look at.

I watch the signs change on the train platform. I put headphones on. I wait for Bluetooth to connect. I wait for the train to come. I wait for the doors to open. I stare out the window and watch houses pass by. I’m between spaces that are between spaces that are between spaces. Everywhere is hardly anywhere. Everywhere is somewhere.

+++

On the train home during spring of my freshman year, I listened to “to Perth, before the border closes” by Julia Jacklin. I didn’t notice her Australian accent through the thickness of her words.

“Everything changes, everything changes / Everything is changing, everything is changing”

Everything was changing, but the route was the same. The people on the train are always different, but they are always there. It’s always hard to find a seat, and I always end up sitting next to a person who, like me, is hardly anyone. Someone who is someone. I feel grounded in unfamiliarity.

I recognize the bridge connecting New London and Mystic. I know that the big white cylinders are wind turbines being assembled. I know that there was a crash on the bridge early last year, that someone with a flat tire pulled over and an oil tanker crashed into the side, that the oil tanker driver didn’t

survive, that the flat-tire driver did, that burning oil dripped down from the bridge onto the houses down below. I don’t think other people on the train read Connecticut news. On the way back to Providence, the farther I get from home, the less familiar it all feels. I recognize a few landmarks and rivers, but there’s a house I’ve never noticed. I pass a Tesla dealership, and I don’t know where I am.

Everything moves fast, but the train always moves slower than I think it does.

+++

On the train home during fall of my sophomore year, I listened to “The Sorcerer” by Twain. I don’t talk to my brothers much—we grew up pretty distant and never had a reason to get closer—but most of my communication with one of them consists purely of music recommendations and last-minute reminders of birthdays and anniversaries. Messages that used to include hard rock music have recently included softer albums: Buck Meek’s Two Saviors, Daniel Rossen’s Silent Hour / Golden Mile, and Twain’s Rare Feeling

Sitting next to a stranger and staring at a vaguely familiar scene, I listen to Twain’s soft and intimate music. The bass glugs along and two guitars melt into each other. Mat Davidson’s tender voice echoes slowly. I hear the lyrics like I’ve known them my whole life.

“Every minute I spend with you is like eternity / So why should I get jealous about your boyfriends? / The second I close my eyes, they'll be gone / The second I close my eyes, they'll be gone”

I don’t know much about my brother’s life. That fact has never bothered me, but I wonder what it means that he shows me softer music these days. We don’t talk any more than we ever have, but our relationship feels softer. He tells me things he thinks are beautiful. He asks me what inspires me. On a phone call (potentially the only call we’ve ever made just to catch up),

we awkwardly exchange I-love-yous. It’s all unfamiliar. Going home for Thanksgiving feels softer. The ride home feels softer.

On the train home during spring of my sophomore year, I listened to “catbite” by kid at the corner. In a space between lines, strings pluck, and new parts fade in and out. Around the seven-minute mark, the song peaks as the singer repeats:

“Our table is a mattress / Our backs against the door / Our table has no napkins / Our table is the floor”

I think of the homes I’ve built for myself: the triple I lived in with two close friends and a cat that grew to trust me, a Steinert practice room, the Underground, a SciLi study room. All familiar places that are always changing. People come in and out; decorations go up and come down. We write on whiteboards and erase it. I eat at different tables, even if the table is the floor of my friend’s room or a mattress. Every table is a home. Every home is a home for now. Eventually, I will never go to any of these places again.

When I go back to my hometown, the popcorn I always buy is a bit more expensive, I have new coworkers, and a new spider has made its own home above my bed. Yet, the same corner of the kitchen is still unpainted. My mom still drinks the same coffee and eats the same chocolate. My dad still roots for the same teams. I still don’t know what teams they are. We eat dinner at the same table we’ve had since I was six. We still eat in the same seating arrangement.

Things push and pull, they change and stay the same, they stop and start. Spaces in between become homes and then become unfamiliar again. In a way, the train seems like home. My shoulders always hurt by the time I get to Westerley. It always stops and starts at seemingly random intervals. It’s always in between the same stops. There, I’m hardly anyone, I’m hardly anywhere. Even so, I’m someone, somewhere.

get serious: on love and motherhood

BY ISADORA MARQUEZ

ILLUSTRATED BY HAIMENG GE

The woman across the street hardly knows your name, yet she lets you pass first along the busy street, before any of the men ahead have the chance. The girl in your third-grade class offers you a slice of her orange despite being explicitly told that she shouldn’t share her food. Your mother runs her hands through your scalp calmly and softly. She blows raspberries into your stomach until you shriek and gasp and giggle. The quiet thrum of Jermaine Jackson’s Let’s Get Serious plays low on our kitchen speakers, she sighs when it’s on the radio, left hand slowly turning the knob.

All the time I think of you.

When I was 13 years old, I assumed I was the ugliest person in the world, with my teal braces, hand-me-down, illfitting Macy’s jeans, and dry curls. I didn’t want to be seen in mirrors, could hardly stand putting on a dress in a fitting room, and refused being photographed for roughly two years. I remember what it felt like when my mother put her own shade of lipstick on my mouth, warm hands cupping my cheeks, and a

small smile on her face. I remember her telling me I was so, so beautiful, and how she was so, so grateful I could be a part of her life. It almost makes me laugh now at how horribly simple I am—at how quick tears fell down my cheeks in gratitude, in appreciation, in pure, unadulterated love for my mother. I’ve started to realize that my urge to love, to appreciate other people, to look out for one another, is all taught by her.

You’re with me no matter what I do.

I often wonder how many little girls never hear those words, how many children grow up untethered, lacking a mother's love. Men have started wars, created famines, and committed atrocities because of the absence of a mother’s love. And perhaps that is the tragedy of motherhood, of a soul connection with a single human—that her grief, her absence, her anger manifests onto you. True loneliness starts the minute your mother forgets to pick you up from daycare, the minute she forgets the birthday of your dear friend or the date of your dance recital. The pain of being forgotten by the person

that matters most—that force is enough to smother.

In the place I wanna be, with my love in you.

When I was 17, I was angry and bitter at the world, struggling to cope with the loss of my rose-colored childhood glasses. I became convinced that “my people”—those who truly understood me—were somewhere far away, across the seas. I believed that once I ventured out into the world, my longing for connection and understanding would finally be fulfilled. My mother would listen to me moan and groan and complain about all I desired while washing my clothes, braiding my hair, fixing my old 2005 Buick. She would smile, and smile, and smile despite my insistence that I would never return to my hometown after graduation. She smiled like she understood, like she forgave my immaturity, and in my aggressively delusional state, I just assumed she would let me go.

Walk around with a smile upon your face.

A year later, at 1:29 a.m., I walk the streets of Providence alone, backpack resting on my right shoulder and tears welling

Careers in the 21st century increasingly place a premium on the ability to collect, process, analyze, and interpret large-scale data on human attributes, preferences, attitudes, behaviors, and complex systems of human interactions

Explore our range of courses that pave the way to a degree in:

SOCIAL SOCIAL ANALYSIS AND AND RESEARCH RESEARCH (SC B )(SC.B.)

5TH-YEAR MASTER’S 5TH-YEAR MASTER’S IN SOCIAL DATA IN DATA ANALYTICS ANALYTICS (SC M ) (SC M )

SCAN TO LEARN MORE

MASTER’S IN MASTER’S IN SOCIAL DATA ANALYTICS ANALYTICS (SC M ) (SC M )

STEM-designated programs

Hands-on research opportunities

Designed to prepare students for careers in data analysis, market research, and beyond

BROWN.EDU/ACADEMICS/SOCIOLOGY/PROGRAMS

in my eyes as I cross the near-empty roads. I pull out my phone from my back pocket and dial the number I memorized at seven years old. She answers on the first ring and as she laughs into the receiver I feel relief from the weight of the day, of endless change, of confusing friendships, of shitty grades, of insecurity. Despite the fact that she has her own life, her own job that she has to wake up for in five hours, despite the 352 miles of distance that separate us—I feel like I’m home again.

Longing for each other just ain’t fair.

You sit in your classes, finish your problem sets, eat three meals a day at the dining halls, and avoid calling your mother because the burden is too great to bear in your everyday life. But when your friend is crying into your shoulders, you rub her back in the same calming circles your mother did when you were a child. And when you fall ill to the natural freshman germs that permeate the classrooms every October, you shuffle through your drawer of medications and drench your Ratty tea in the same honey brand your mother used. And on the rare occasion that you pass by groups of young children running down Thayer, you move to the side so they won’t run headfirst into the traffic on their left. You don’t even understand; you can hardly fathom the fact that your mother’s teachings bleed into every little thing you do today, that a silent lesson of culture, of empathy, of love has now been instilled in you before you could even form your first words.

And you cannot tell me that you don’t hear your mother’s

words in moments of fear, that you don’t think about her when you adorn yourself with her old jewelry or listen to a Top 40 song from 2004. I think, sometimes, it hurts more to admit how much we care.

When we’ve got so much love we want to share.

I remember being 19, sitting in my advisor’s office, telling her how useless it was that the only thing I seemed to care about, beyond school, beyond friends, beyond hobbies, was people.

“I like people, right? But you can’t make a degree out of that,” I complained, voice high and (probably) annoying.

“Well, sure you can. Why would that be a bad thing?” At my advisor’s question, I’m left silent, although the answer dances on my lips: Because then, I would be like my mother. And that’s terribly unkind to think of, but it’s what I do think of. I think of the Saturdays we spent helping my uncle, who could hardly spare my mother a “thank you.” I think of my mother under the hot weight of the sun, pulling weeds from our neighbor’s garden because Barbara’s knees were too weak to crouch. I think of her with her students in the classroom, attempting to rub their Sharpie marks out of her desk, hunched over, tired but persistent.

And I think that if I had a heart that big, it would probably choke me. But for my mother, it fills her like a reservoir—an unlimited resource that is meant to be shared.

And perhaps the bravest thing you can do within a world of trained apathy and feigned nonchalance is to love like a mother. With open hands and tired eyes, insistent, egoless, unafraid.

At the very least, I’ll try to.

Let’s get serious.

In my mind, you have taken a permanent space.

BY MICHELLE BI

ILLUSTRATED BY JIAYING

LI @JIAYINGL_I

But you’re too infatuated with the moment to worry about any of this.

ii. on grasping

For the hundred-thousandth time, you’ve found yourself in your friend’s driveway.

The two of you have known one another for over a decade, grown up intertwined. You’ve been here many times before: to meet her for snacks before racing to the playground, labor over middle school geometry worksheets with the rest of your friends, get ready for tenth-grade homecoming.

This time, this sunny August afternoon, is different. This time is a goodbye.

eyes each time you say another goodbye.

The night before the flight away from everything you’ve ever known, you crawl into your parents’ bed, pull their polkadotted comforter up to your chin, and bawl your eyes out.

Sure, on occasion you find yourself fielding a dozen questions at once from your parents’ friends and your friends’ parents—“So far away!” they fret. “What happens if you get sick? What happens if you miss home?” And you assure them that you’ve had all your COVID-19 booster shots, that you’ve always preferred cooler weather anyway, and you flash them a smile with all your teeth.

And sure, every day your still-empty suitcase seems to yawn a little wider, and your packing list flashes a little more urgently on your smudged laptop screen. (What should you bring in case it snows? How many clothes hangers do you need? Which one of your dozen raggedy stuffed animals should you pack? What happens if you miss home? What happens if you miss home?)

Today, there’s four of you: you, her, and two other friends sitting in the car. You’ve grown up together, seen each other at your bests and worsts. She leaves for college tomorrow, and that collective awareness seems to put a crackle in the air.

The group lingers in the car for far too long, bantering and laughing. And then you’re standing at her front door in a circle— “Can we just stay here for a little longer?” someone asks.

So you all stay for a little longer, make feeble jokes that die quickly on your tongues. Somebody starts crying, and then everybody else does too. You hug each other tightly, hands clutching desperately at shoulders. This love rends your chest in half.

And then she’s disappeared behind her front door. You

iii. on holding

Your hands are cold as you clutch the handles of your suitcases close to your body. Em-Wool looms in front of you like a brick-red Mt. Everest. The trees are so green here that they make your eyes water.

Every single street on this campus seems to be swarming with people on move-in day: hundreds upon hundreds of jittery freshmen, parents hovering just behind them, mounds of luggage everywhere you look. Surveying what is to become your new home for the first time, you feel a bruising ache in the bottom of your ribcage.

The morning passes in a blur of staircases and sweat, bags and a bare new dorm—the whiteness of its walls almost oppressive.

You and your parents wrangle the sheets onto the mattress, Swiffer the floor, smooth out your wrinkled posters, and tape them haphazardly above the bed. When you finish, you step back to admire your work; your mom puts her palm on your back, and you find yourself leaning into it, hungry for the warmth.

You spend the rest of the day roaming the campus, both with your family and without, learning this new roadmap and the shapes of the paths across the grass. So different from the rolling yellow hills of your hometown, the sleepy quiet that blanketed every street. Everything here is green and bright and soaked through with an unfamiliar energy, quicker than the airplane that brought you here, quicker than the wind chasing through the trees.

iv. on lingering

And then your parents and sister are off to explore New England for the next few days, and you find yourself alone on campus, adrift in seas of “What’s your name? Where are you from? What are you studying?”

Orientation is like nothing else. You strike up conversation with anyone you can, beam at strangers-turned-acquaintances until it feels like your face is frozen in a smile, think of home, exchange names and Instagrams and jokes and phone numbers, think of home, fight with the laundry machines and attend ice cream socials and stay up until 3 a.m. and think of home, and think of home.

You’re not homesick—you’re exhilarated—and yet you find yourself searching for hints of California wherever you go. The way the sunlight on the Main Green pools across your shoulders feels just like the warmth of your backyard. The cerulean sky, even studded with gray clouds, is an all-too-familiar shade. Your laugh begins to grow louder, broader, just as it sounded before.

Four days after moving in, you meet up with your family for the last time before they board the plane back to LA. You can tell this moment will live forever in your mind, that you will spend

hours poring over your memories of the emerald-green trees in front of Emery and the breeze tousling your hair. You know their voices will soon fade to an aching echo in the atrium of your heart.

Most of all, you sense that you will replay their hugs, the way you hug back, hands sliding behind rib cages and between shoulder blades; four becoming one for just a moment, four becoming three and then one going, going and gone.

v. on letting go

It’s not until a few weeks into the year that you realize things are beginning to feel familiar. You can suddenly swipe into the SciLi on your first try every time. You always skirt around the seal on the Pembroke steps for completely rational reasons. You can trace your way from Jo’s back to your dorm without even thinking about it.

Oddly enough, the very realization makes all of it seem new again.

Some nights you still find yourself thinking of the warmth of your childhood bedroom, the sounds of the crickets along the main road. Some nights you compose yearning love letters in your mind to the town you left behind, the people who raised you, shaped you, and then, and then—

The crackling of new autumn leaves underfoot as you walk past the dancing statues, your fingertips gliding across the ragged piano in the basement of the campus center, the sunset over Sayles, the weight of an acquaintance-turned-friend’s head on your shoulder, their hand in yours.

You’re a month into this strange new life, and it feels like an embrace.

BY NINA LIDAR ILLUSTRATED BY CHASE WU @CUUBIKL

When I left California for Rhode Island, I said a permanent goodbye to a world where the people I held dear were amassed in one place. My relationships to them began to be rooted more in memory than in the present. Meanwhile, my love found new footholds with a sparkling web of college friends, whom I learned to crave with the same daily regularity that, before, I had craved my hometown clan with. A break in a semester or between school years now swaps my two worlds—college friends, sprinkled across the country, even the globe, dissipate into a world temporarily beyond access, and, for a spell, the people at home become my world again.

Between whichever cast of people distance wedges itself, we try to bridge the gulf. We send sporadic texts, we call, and it all feels like a flattened facsimile of the relationships we know to be so much more.

But we forget that correspondence can be more—it can be a thrill and a treasure.

In the last days of August, I wrote a longhand letter for the very first time. Of course, I’d handwritten personal messages before. I scrawled a dramatic, tear-stained goodbye to my collegebound sister six years ago. I’ve written sentimental birthday cards, pressed carefully creased notes of affection and well-wishes into the hands of camp friends and graduating classmates, left inscriptions in books I’ve gifted, and so forth. But the intention

behind them was not to elicit a response, nor probe into a new corner of the relationship, nor reveal new truths—only to offer up old affections in new prose, like a period at the end of a long, trailing sentence.

This letter was not that. I left home in California to spend the last week of summer with relatives in the lush foliage of the northeast. There, the full weight of my distance from those I care for in my home state settled on my chest and made my every move heavy. It hurt to miss people so deeply, and, even more, to anticipate the stunted online echoes they would soon morph into.

Made meditative by wooded seclusion and backed by the chatter of wind-rustled leaves and wood thrushes’ soprano exchanges, I bent over a blank sheet of paper and wrote my first real letter. I wrote driven by the necessity of converting care, nostalgia, and gratitude into something tangible and permanent— for myself, yes, but more urgently and more essentially, for its recipient. I wrote a letter with a cramping, ink-smudged hand, because no other medium could accommodate the honesty, directness, and openness that felt so vital to convey.

The process started haltingly. My prose came out clunky and overwrought, and I worried about inconsequentialities like the consistency of my handwriting and the quantity of scribbled-out, misspelled words. The page seemed fit to burst with superfluous adverbs and filler sentences. The trash can swallowed

my first, second, third attempts.

But then I realized that I was writing neither an essay, nor the epilogue to a friendship consummated by life changes like a graduation or a big move. I wasn’t composing a writing sample to prove my prosaic worth to some rigid professor. I was doing nothing more—and nothing less—than having a conversation with someone dear. The only difference between normal conversation and this was that writing delivered my thoughts through a slower, more refined channel than the usual hurried spillage of spoken dialogue—a chance to cut out the “ums” and replace them with words that nailed a feeling or idea on the head.

The words flowed. I wrote about moments from the summer, spent with the letter’s recipient, that I’d been thinking about with particular fondness. I relayed anecdotes from the time since I’d landed on the East Coast. My musings and sentiments gathered momentum and rolled straight out onto the page.

When I slipped the sealed envelope into the mailbox, I felt a similar kind of catharsis to that of when I close my freshly inscribed journal and lower my head onto the pillow each night. All those pent-up kernels of thoughts had found their way into words. And now, those words would find their way into the hands of the person for whom they’d urged their way into coherence.

Of course, receiving a letter in return delivered a fresh tide of gratification and gratitude. How special it was to see that

handwriting! Those loops and smudges are, I’m convinced, the next most alive, physical form of access to another person after touchable, visible, and audible presence. They’re a distillation of personality into a precious visual pattern: no letter is the same as the next, but each one’s variability is familiar—like the cadence of a voice. And it made me smile so wide to hear that voice in my head—no less full of honesty and personality than if we were talking side-by-side over the hum of a car engine, or in the quiet of a bookstore backroom, or in whatever other setting our adventures have landed us—but inflected, here, by the same attention to linguistic accuracy I’d poured into my own letter. In that attention lies a wonderful truth about letter-

writing contains explicit professions of care, its existence is evidence enough: effort and intent and purpose live in each scratch on the page.

I view electronic communication modes as inherently generic. I’ve never felt inclined to print out a text message, even if it says something as explicit as “I love you.” Any sentimentality is circumscribed by pixelated, formatted impersonality. I could receive two “I love you” texts years apart and in entirely unrelated contexts, but seen together, they’d look and read exactly the same. But a letter, I’ll save in a heartbeat. Its preciousness lies in the minute choices: the positioning of a word on the page, or the smushed revision of an added word over a carrot—proof of continued consideration. And in the physicality—the blot of ink where a hand smudged a word before it dried, the crease where a thumb and forefinger pinched the paper into a neat fold. The evolution of the script from print to quasi-cursive where the writer had relaxed into flowing dialogue—the same way that, as comfort seeps into face-to-face conversation, we shed stiffness and stop fidgeting and grow loose, at ease. A handwritten “I love you” note, even if undated and unsigned, is unreplicable. A precious instant of the scribe’s life is preserved in all those leaning letters.

I’m revealing nothing new. I’ll surprise nobody by saying that letter-writing is a rich, age-old tradition. But I think it’s a valuable—essential—reminder, particularly to our generation so saturated with screens, that such personal, treasurable communication is possible. It’s as available to us as any of our

“A tale in fragments can endure eons; I am a scattered clay piece of an ancient epoch. My ancestors are spread elsewhere, but I know the story of my mother, my brother, and especially me—even in its broken pieces.”

— Leanna Bai, “On Fragmentation And My Disappearance"

“In the midst of this season of self-discovery, love arrived, quietly, letting itself in through the back door. I currently cherish someone very deeply and am cherished by them in my entirety. Just when I was least expecting it, love snuck up on me, like a tiger in the night, terrifying but beautiful. As the leaves fall, so do I.”

— Indigo Mudbhary, “It’s Okay to Love Multiple People” 11.2.23

other modes. I don’t argue staunchly against the value of texting or sending voice notes or even posting on your Instagram story. Those modes of communication are so ubiquitous that it would be ridiculous to recommend replacing them with my new favored anachronism. But their ephemerality diminishes their strength, no matter how carefully crafted they may be. A text gets buried under the next messages within days, even hours. That emoji I tack onto the end of my “See you soon!” is a feeble attempt at distinguishing my message from the sea of its potential duplicates.

The letter from which I brushed pollen deposited by the breeze, where I scratched out a word in exchange for one whose musicality I thought the recipient would enjoy more, into which I poured a long stream of effort and honesty…That letter is a more legitimate version of me than I’ve ever put into a text or even a call. And I know the same is true of the letter I was so lucky to receive.

Letter-writing is a slow mode, and a quiet one, too. We trade the exhilarating pace of spoken dialogue for a pensive kind of care—the head rush of anger for an exhalation of forgiveness, the comfort of physical presence for the warm, smoldering embers of nostalgia.

Our relationships can grow in that empty space between us. And holding a letter, the feel of paper dented by a pen’s excitement, the little heft of it folded inside its envelope, we remember that the space between us really isn’t empty at all.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Joe Maffa

FEATURE

Managing Editor

Klara Davidson-Schmich

Section Editors

Daphne Cao

Elaina Bayard

ARTS & CULTURE

Managing Editor

Elijah Puente

Section Editors

Emily Tom

AJ Wu

NARRATIVE

Managing Editor

Katheryne Gonzalez

Section Editors

Gabi Yuan

Chelsea Long

LIFESTYLE

Managing Editor

Tabitha Lynn

Section Editors

Daniella Coyle

Hallel Abrams

Gerber

POST-POURRI

Managing Editor

Rachel Metzger

HEAD ILLUSTRATORS

Junyue Ma

Kaitlyn Stanton

COPY CHIEF

Emilie Guan

Copy Editors

Indigo Mudhbary

Shaliz Bazldjoo

Jessica Lee

SOCIAL MEDIA

Managing Editor

Tabitha Grandolfo

Section Editors

Alex Hay

Eliot Geer

LAYOUT CHIEF

Gray Martens

Layout Designers

Amber Zhao

Alexa Gay

Romilly Thomson

STAFF WRITERS

Nina Lidar

Sarah Frank

Pooja Kalyan

Ana Vissicchio

Gabi Yuan

Lynn Nguyen

Ben Herdeg

Emily Tom

Zoe Park

Daphne Cao

Indigo Mudbhary

Ishan Khurana

Katherine Mao

Eleanor Dushin

Sofie Zeruto

Evan Gardner

Isadora Marquez

Sydney Pearson

Ayoola Fadahunsi

Samira Lakhiani

Ellyse Givens

CROSSWORD

AJ Wu

Ishan Khurana

Will Hassett

Lily Coffman

Want to be involved? Email: joseph_maffa@brown.edu!

BY RCHIN BARI

ILLUSTRATED BY ANGELINA SO @ANG_I_I

What is a sandwich?

We think we know until someone mentions a hotdog. Many resolve the hotdog debate by defining a sandwich as “two slices of bread with something in the middle.” It’s a simple enough response until you consider subs or hoagies. Then things get messy.

Subs and hoagies are often not cut all the way through. Does that mean they are not sandwiches? If the act of slicing determines what is or isn’t a sandwich, should we define a percentage of how much a loaf is cut? That seems arbitrary. If we don’t use the cut as the deciding factor, then a hotdog would qualify as a sandwich and we’re left to define the role of bread. Consider folded breads: Does folding bread make it a sandwich? If the amount of filling matters, does a sandwich even need sliced bread? Otherwise, an open-top sandwich might be incomplete or infinitely flooded.

Are tacos just folded, open-sided sandwiches? If we accept this, does the percentage of closure matter? Then the amount of filling should be irrelevant. If not, then any filled bread—like a burrito, gyro, or even a hotdog bite—would also count as a sandwich. Would one olive in a 100-foot square block of bread be a sandwich?

When does something stop being a sandwich and simply become bread?

If any contact between bread and another material constitutes a sandwich, at what point does it become something else?

In western culture, we tend to see bread as something that can be sliced. We define bread by its core ingredients (flour, water, salt, and yeast). Yet bread comes in many forms. Matzo is unleavened bread eaten during the Jewish holiday of Passover. In Ireland, Subway’s bread is classified as cake. In the Indian subcontinent, everyday bread like roti is made with just atta (wheat flour) and water.

Indigenous peoples across the world use maize, cassava, and rice to make bread-like foods. So why

divide things into categories that, when scrutinized, are utterly arbitrary?

How much bread makes a sandwich? Is bread ever really just bread?

Bread could be defined as a product of gluten, but that excludes almond flour or cassava flour breads. What about moisture? Hardtack, the teeth-breaking “bread” of sailors and soldiers before modern rations, had close to none. Starch? Stephen Wealthall, who cannot consume starch, made bread without starch. If the percentage of content doesn’t define bread, it may simply be a question of commonality. All breads share carbohydrates. As does lettuce. And mango.

Carbohydrates are molecules composed of hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon atoms, typically in a ratio of 1:2:1. According to quantum field theory, particles are excitations of underlying fields that permeate our universe. Carbohydrates, like all matter, are made up of particles that appear and disappear due to fluctuations within these fields. The very essence of bread is rooted in these energy fluctuations.

The percentage of carbohydrates required to define a bread product is completely arbitrary, so could any food item with carbohydrates be bread? Could any item with carbs be bread?

For millennia, humans have divided the world to make sense of it. We have understood much of the world through definitions and equations, insisting that something can only exist within the frameworks we made up. But in doing so, we invalidate the ineffable nature of our universe, and narrow our scope of understanding.

Perhaps we cannot help dividing objects around us. Nevertheless, by considering all the possibilities of an object and then setting in place meaningful and distinct limitations, the frameworks we place provide us a way to objectively explore the universe, one slice at a time.

Campus Shop and Technology Center

244 Thayer St. Providence, RI 02912

401-863-3168 | ShopBrown.com

Store Hours:

Monday to Friday - 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM

Saturday - 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM

Sunday - 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM

AXIS HATS NEW YORK

Book Talk with Elizabeth Abbott by Cathrine White Editor of Bill Reynolds Story Days

Friday, October 25th - 12 PM to 6 PM

Saturday, October 26th - 10 AM to 6 PM

Friday, October 25th at 5:00 PM

Herff Jones

Friday, October 25th - 11 AM to 5 PM

Saturday, October 26th - 11 AM to 5 PM

Sunday, October 27th - 11 AM to 2 PM

Family Weekend Hours

Friday, October 25th - 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM

Saturday, October 26th - 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM

The Brown Bookstore is a gateway to the University and beyond. Your one-stop shop for Brown apparel and gifts, as well as books, technology, and more! Visit the Brown Bookstore at 244 Thayer Street or shop online at ShopBrown.com.

Sunday, October 27th - 8:30 AM to 4:00 PM

Jostens

Friday, October 25th - 10 AM to 4 PM

Saturday, October 26th - 10 AM to 4 PM

Sunday, October 27th - 10 AM to 4 PM