MAR 3 VOL 31 — ISSUE 3 In This Issue New Leaves Despite It All Liza Kolbasov 4 And The Eyes Are Hers Mack Ford 4 Esport Epics Hari Dandapani 2 I Can Say It For You Lily Seltz 6 postImmortality In The Virtual World Olivia Cohen 7 Far From The Thrifting Crowd Sean Toomey 8 Crossword Will Hassett 9

Cover by Harshini Venkatachalam @hxrshini

It’s Friday afternoon, and I’ve arrived home from middle school just in time to catch the last game of the European professional League of Legends scene. The rest of my night will be spent catching up on highlights from the games I missed while I was at school, with breaks only to eat, walk my dog, and spend enough time with my parents to satisfy their social batteries. I drift off to sleep listening to my favorite streamers playing League through my phone’s tinny speakers, and I awaken refreshed at noon on Saturday with another afternoon of European League of Legends ahead of me.

Letter from the Editor

Dear Readers,

This week, my mind’s been on running. Run-on sentences (deliberate and inadvertent), running out of time, running into people on Thayer street, running home to my friends, running away… As a senior on the brink of an ending, I’ve been dreaming of escape. I’ve been running from the dark chasm in front of me and diving into deep pools of comfort: my roommates around the kitchen table, steam from our teacups catching the afternoon sun; stolen moments of softness in Providence bars, cafes, boba shops; pockets of frivolity, of aimless, ambling joy. I am romanticizing, I am running toward the very fantasy I am living.

Esport Epics on what makes sports fun

to watch

By Hari Dandapani

illustrated by Jasmin Lin IG: @sasha_art_0201

By 4 p.m., the European scene is over for the day, but my evening is just beginning. Now, it’s time for the North American League. I don my Team Liquid shirt to show support for my favorite team and spend the next five hours watching regular season games. After each game, I switch browser tabs to Reddit to comment my analysis of the winning team’s strategy, rewatch the sickest plays, and upvote memes about the day’s games. I know all of the players, all of their current and former team affiliations, and all of the narratives surrounding the players and the teams—I am living the life of a

Our writers, too, are escaping, fantasizing, dreaming, hoping. In Feature, our writer draws pleasure from caring deeply about League of Legends. In Narrative, one writer holds out hope for their houseplants; the other ponders the vulnerability and power of taking the stage as a woman. In Arts & Culture, one writer looks to the artist Samia for rescue, relatability, and redemption; another reminisces about connecting with a friend through the fantasy worlds of video games. Our Lifestyle writer, having escaped to Bologna, advises us on thrifting in his new home. Also in Lifestyle: the first of our now-weekly crosswords!

So come run away with us—be it deep in the crossword clues, into video games and childhood

League of Legends superfan.

How did I end up like this? What happened?

***

Growing up, I tried again and again to follow different sports. I thought it might be inspiring to watch people do something at the top of their game, and because many of my friends were interested in the sports world, I figured I would get into it too. So, I would turn on the TV and watch a game of baseball, basketball, or football, and while I understood pretty

stories, or toward glorious music and theater. Sink yourself, for a moment, into what’s right in front of you, keep your mind from running months ahead. For a moment, forget that time is running, always, onward.

Prematurely nostalgic, but always yours, Aditi Marshan Copy-Chief

FEATURE

2 post –

quickly what was occurring on screen, I never got to the point where I would really want to watch it. Maybe it was the pace of the game or because I didn’t actually play it, but this didn’t explain the whole picture: I would eagerly and intently watch mind-numbingly boring games of League, and I did play pickup basketball with my friends sometimes.

The more likely reason behind my disinterest was that I didn't immerse myself in the narrative world of those sports fandoms. It’s like starting a TV series from season eight—as a casual viewer, I didn't have the background knowledge that would have allowed me to care about the characters or the world that players, casters, and fans have constructed.

Once you’ve bought into a sports universe, the potential for analysis is endless. Sports fans spend their time arguing over who the greatest of all time (GOAT) is. They invest themselves in conjuring narratives for why their favorite player should be the MVP and uphold long-running rivalries with other fan communities who have constructed different stories and assigned different protagonists and antagonists from the same set of events. These points of discussion—which may seem mundane to outsiders—are how sports fans construct the narratives that keep them so excited by the repetitive and linear nature of actually watching the sport. They know what good dunks, clutch touchdowns, and crazy knuckleballs look like—these are things they’ve seen before. What they want is a good story.

My relationship with League is inseparable from my childhood. I grew up in Melbourne, Florida—a place my friends and I dubbed “Mel-boring,” since there was never anything exciting going on. Although we’re right next to the beach and only an hour away from Disney World and Universal, it was often hard to find things to do. The issue with Melbourne is its suburban sprawl; everything is so far apart that, until you get a car and a license, it’s impossible to go anywhere without being driven.

As fifth graders stuck at home most afternoons and weekends, my friends and I thought that technology might be the solution. I didn’t own a gaming console like most of my classmates, but my parents had recently bought a laptop for our house, so I did some research and convinced my friends to try out the hottest new game in 2012: League of Legends.

League is a team-based, multiplayer online battle game, where two teams of five players compete against each other, employing strategy and mechanical skill to try to destroy the opposing team’s Nexus, a structure located at the heart of each team’s base, while defending their own. Players select from a large pool of “champions” and in-game items, with your

Bones

decision varying depending on how your team is doing, the champions the enemy team has chosen, your own preference, and many other considerations. League is a challenging game to learn, and a number of my friends would quit the game soon after joining because it was no fun being bad and losing all the time.

But I was determined. I wanted to learn how to navigate League’s endless strategic complexities —I wanted to get good, and I had the free time to do it. Or at least, to attempt to, because the hours I began putting into the game playing alone did not translate into any significant material gains.

My aspiring solo career was further quashed by another formidable obstacle: my parents, who managed to undermine my esports training regimen without particularly trying. I found myself playing less and less; I could never find the uninterrupted 45 minutes it took to play a game of League because I could never expect when my mom would summon me from my room to hand her the TV remote, or when my dad would ask me to help him uninstall some virus from sketchy Indian news sites. Not to mention, as a middle schooler, I needed to be in bed and ready to fall asleep by 10 p.m.

But my teenage brain was already hooked. Even when I wasn’t playing, I sought out ways to engage with its content. I found myself fantasizing about making super awesome plays in math class and brainstorming cheeky hypothetical strategies to use in game. And, importantly, I discovered after searching “Best of League of Legends game ever” on YouTube that there was an endless supply of LoL content to watch. I remember watching the entire game of Team WE vs CLG.EU and being so excited that I’d discovered an avenue for investing myself in the game that was free from the barriers I’d run into while playing it.

I kept creeping further and further down the League of Legends rabbit hole. I started watching the live games of the professional circuit of North America. Soon after, I was watching highlights from professional leagues in other regions and videos from League streamers, and eventually I found myself waking up on weekends to watch pro play in real time. I was addicted… not to playing League, but to watching other people play it. What had begun as a search for a way to fill my free time at home had grown into something that I cared very deeply about.

***

As I’ve gotten older and no less addicted to League, I have spent a lot of time thinking about why watching other people play this video game appeals so much to me, and just like with any other sport, the answer comes down to understanding esports as a form of storytelling.

The basic League of Legends game has a fairly

simple plot structure. At the beginning of the video, we meet our protagonist (and maybe their accomplices) as they venture to try to win. The friction in the story arises from some enemy constructed in the minds of the viewer by the streamer or casters: teammates playing poorly, the opposing team playing extremely well, or the difficulty of some new tactic that our protagonist is developing. As we watch the game, we get to root for our beloved protagonist—even imagining ourselves in their place—while they take on their enemies to try to achieve their goal of winning the game. The epic fight scenes, cheeky strategies, and bits of humor and excitement added in by commentators augment this fairly linear plot and make it something unique and special compared to the millions of other videos centered around the same overarching game.

At the same time, these stories fit into larger narratives that the fans construct about these players, often drawing upon history from previous competitive seasons or past drama. Will Tyler1 be able to show us that he can really reach the top playing every role? Does Doublelift still have what it takes to be the best after returning from two years of retirement? I’ve now spent enough years as a superfan of the pro scene and a follower of several streamers to understand all of the stories that the analysts and commentators want viewers to imagine. As I consume more and more content, the gameplay itself becomes increasingly immaterial. Instead, I am watching to see how the plot of the story progresses, to hope that my protagonists will be able to eke out the victory or to see if the underdogs can make a miracle happen. The real beauty comes from understanding these videos as stories or episodes that fit into a larger narrative.

***

I’ll be graduating from college in just about three months from now. My free time and ability to see others are no longer constrained by whether or not my parents can drive me to a friend’s house; my life has changed substantially from my middle school days. But here I am, still consuming League content, rooting for teams I arbitrarily decided were my favorites eight years ago and following players and long-time streamers to see how their seasons are going. I’m invested, perhaps partially out of fondness or nostalgia, but also because the tales that I and other spectators weave around teams continue to shift and unfold. I sometimes wonder if being a League fan will ever get old, but understanding these games as narratives lends them tremendous staying power. The thing about stories is that, when told right, they have the ability to sweep you into their arcs and captivate you all the same, whether you’re hearing them for the first time or the hundredth.

“It’s literally Silk Chiffon-ing outside.”

“To me, it looks labial.”

FEATURE

***

1. Humorous

2. Humerus

3. Ethmoid

4. -r

5. BBQ pork ribs

6. Red-

7. To pick 8. Wish

9. -ing

10. Apple Teeth

March 3, 2023 3

And The Eyes Are Hers women on display

by Mack Ford

Illustrated by emilie Guan

When the lights come on, there is a single spotlight, trained on the center of the stage. The actress is there, basking, lounging in the glow. Her legs dangle off the edge of the piano, willfully uncrossed. Her hair is piled high atop her head into a mount of carefully aligned curls. She wears a fitted black dress with lacy fringe. The hem stops just above her knees, and the neckline does not dive too low on her chest. Her mother always said it’s about what they cannot see. One strap slips off her honey-sweet shoulder. All eyes are drawn to that thin strap, slipping.

Then she begins to sing. Her lips pucker just so, and she stretches her shoulders back as if to drink in the rays of spotlight that shine down from above her. She is a star (she was always meant to be a star) from the minute she steps on stage.

The notes pour out of her chest, deliberate and dripping.

She feels the eyes on her and loves them. And they love her. And she loves them for loving her. All the while, they watch. The strap starts to fall further, only to tug back toward her when she raises her head—a tease. Mouths water. She has a gravity like that. Everything is drawn to her, as she is to everything.

She might say she started acting because of something she disliked about herself—so she could pretend to be someone else; or that it was only ever because her mother wanted her to be in movies; or that it was her way to revive, reclaim, redeem those characters she plays. But lurking behind the pretending and the mothers and the reclamations: power. On stage, under those caressing lights, each watchful eye is hers to bend at will.

Each ringlet of her hair is coiled into a stiff corkscrew. They bounce just a bit when she tosses her head back to laugh—a glittering sound composed of precisely three sharp exhales. She wets her lips and lets them fall slightly ajar. When the main spotlight shines, her lips seem to glimmer, daring anyone to be drawn in and drown in their dew. The soft skin of her chest slopes—she knows their eyes graze over it, knows how it intoxicates them. How they long to peel the rhinestone necklace off it, how they

long to peel the very skin off until there is nothing but muscle and bone. Only then might they experience her in her bare glory. It beckons them, that siren skin, and draws them out of themselves. Mouths lag open, tongues loll out, hands fall to laps; their bodies are no longer under their control. In fact, they are no longer bodies at all, but rather eyes, just eyes.

And the eyes are hers, even when her face twists with stage-lit tears. Her anguish is careful, measured. Her pain is raw, and it singes the eyes of the audience, even as they spur with their perverse desire to see without getting quite close enough to burn. They love to watch this selfravaging, this self-immolation. Her hands shake as they fall to her side, and her eyebrows draw together in grief. This is the opening of her soul, the turning inside-out of the femme fatale.

And now she has reached her final song. She lets her eyes drop sorrowfully and they realize that this is, indeed, the end. Oh, how their faces fall in despair. In that moment, they watch her. And she watches them watching her. She holds onto the last note like it’s a fraying rope— the only thing that stands between her and a brutal death below. It wavers a little, then holds strong. When her eyes shut, at last, there is silence: one suspended moment of silence fluttering gently to the ground, featherlike. When it hits the floor, the men erupt in cheers. Their applause is almost violent. They throw their hands together like poor, brutish seals begging to be fed, grunting and flushed with pleasure.

Perhaps tonight someone will call out and plead with her to stay. Of course she would not stay, even if they begged. But she dearly loves the look in their eyes when they fall to their knees before her.

And then she’s walking home, and it’s late. They are covered now, those shoulders that have reduced men to dogs, frothing at the mouth. Her hair is tucked beneath a checkered scarf like a little old lady in wintertime. She walks quickly, but their eyes find her anyway. They bend their gazes around corners from gum-spattered doorways, never quite close enough to touch. She can feel the eyes creeping up the back of her neck like so many legs. They are prying and writhing and frenzied. They follow her all the way up 78th street, and she walks a little faster. She was meant to be a spectacle far before she set foot on a stage.

At least on stage, the eyes are hers. There, she is ogled and claims that stare as her own.

She remembers it now: that moment just before she bows and the spotlight turns its great head away, when she

looks up. She feels the slinky dress and long legs and strap that nearly falls off her shoulders in a way that makes every man in the room want to fall right off with it. With these gaudy clothes under garish lights is an end to the stares she did not ask for. At least it will be her place now, this body. At least she won’t be slunk beneath a billowing coat with her chin tucked down, hurrying.

Under the spotlight’s final glow, she plants her feet, feeling the weight of the worship and the watching and the men who would throw themselves down upon her violet shoes if she let them. She doesn’t let them. Instead, she lets her face turn toward the light, looking up as it looks down at her. And she looks at it for looking at her. The acrid scent of hairspray settles around her mouth, and her lips curl, and she bows.

New Leaves Despite It All on

finding hope in houseplants

by Liza Kolbasov

Illustrated by Connie Liu

There are the ones I left in a drafty room over a frigid New England December, only to come back from sun-baked California to their slouching, frozen corpses. The countless overwatered succulents, the root-bound vines, the pothos I just couldn’t make happy. The ones left forgotten, unwatered on my windowsill while I spent 10 days in Covid quarantine. The ones I tried, too late, to rescue; the ones I burned in the sun or let droop in the shade because I wasn’t quite sure which lighting conditions they liked best.

I cannot count how many plants I’ve killed in my 21 years on this Earth. Needless to say, I do not have a green thumb. I’ve even killed plants that were not my own, hopelessly overwatering an unfortunate cactus subjected to my care while my mother went away for a business trip.

Growing up, my house was lined with cacti. The faint memories I have of the apartment I lived in as a toddler feature a cement-covered balcony with cacti all around, breathing in the sun. Cacti were my mother’s great love. When we moved, she brought them with us, gently placing them along

NARRATIVE

4 post –

the new, shadier balcony. She loved them until, one day, she brought home a cactus that shot needles at her from several feet away, leaving an array of microscopic shards embedded in the palm of her hand. Since then, she’s stopped buying cacti. I felt a little sorry for the cactus, fighting with all its might to maintain its independence, some control over its world. In some ways, I could imagine how it felt, pushing against the very hands trying to keep it alive.

Although a few cacti linger on my mother’s balcony nowadays, they’re far outnumbered by succulents—cacti’s tamer, gentler cousins. There are a few scattered leafy plants in my parents’ bedroom and in the corner of the living room—a money tree tied to a curtain rod with yarn, a Monstera whose arms trail along the floor—but for the most part, there are succulents all around.

It would make sense if, used to living with a plethora of succulents, I’d seek to grow some of my own. Perhaps, I would even have picked up some of my mother’s skills with them. I’ve been told time and time again that succulents are some of the easiest plants to take care of. But, truth be told, succulents unnerve me. There’s something eerie about a plant that dies from too much care. Cacti, at least, are upfront about their standoffishness. Succulents look absolutely fine and dandy until their arms start to fall off. It’s so easy to forget about succulents, perfect little wax figurines that they are, and so easy to smother them with care. I oscillate between the two extremes, never quite hitting the right balance. No, I’d prefer a plant that can communicate its needs.

For this reason, I am not unnerved by leafy houseplants—vines, Monsteras and pothos, even the occasional snake plant (although, being close to succulents in texture, those are on thin ice). I love them—the way their expansive greenery brings life to a room, even in winter, when everything outside is on the brink of death. Despite the countless times I’ve utterly failed at plant care, I buy plant after plant, and line them up in every room—a Scindapsus weaving its arms along the windowsill, a snake plant reaching for the sky, a prayer plant with its wispy leaves folded together. There’s the plants from various soon-tobe college graduates on Facebook marketplace, which I’ve walked across the city to collect; the one from the greenhouse above BioMed; the few that came to me from who knows where. I know that houseplants aren’t, in theory, difficult to take care of. All they need is a nice soak in a bowl of water every few weeks, some sun, and to be moved to a

bigger pot once in a while. I start every semester with the profound resolve to keep my plant companions alive and happy.

And yet, the moment my life starts to get busy—the moment darkness and cold start to settle over Providence at earlier hours—it all falls apart. I don’t have the energy to care for the complicated mess of a human I am, let alone the green dependents I’ve shackled myself to. They sit, wilting, on every surface, irritating little reminders of the fact that I do not have my life together. I know that, with just five minutes, I could spare them their suffering, bring relief to their parched roots (and give myself hope that I am not, after all, the most incompetent person alive—the perpetual thought pushing at the corners of my mind, keeping me stuck in this empty uselessness). There’s a part of me that knows, despite everything, that if I could just force myself to do these easy tasks, to water my plants, to move them into the light, I would feel just a smidge more human. It would be a confirmation for me that my hands are, afterall, capable of care. But somehow, this little task, like all little tasks, feels insurmountable.

So I am endlessly grateful for the ways in which, time and time again, my plants forgive me. So often, I find my life suddenly falling apart, my work undone, one too many days without doing laundry and three too many days without grocery shopping. But then, finally, I work up the energy to fill several bowls with water, to dip my dry plants with their curled up leaves into them. I watch them drink, zealously, emptying bowl after bowl of water. To be alive, they remind me, is to have needs. And the next day, they perk up, smile at the sun, at me. Not necessarily back to normal, but looking better, fuller, greener. Maybe not all hope is lost.

I share the house I live in with many plants— some mine, some not. One of my housemates grows succulents much more successfully than I ever could. Another has been propagating basil, with 10 or 20 new basil children shaking their leaves from inside paper cups. Fernando Gatsby, an asparagus fern in a large, brown pot, belongs to the house. Many people have taken care of him over the years. He’s almost died so many times but, like a phoenix rising from the ashes, keeps coming back to life. He’s survived two years of Covid, when the house was essentially deserted, summer after summer of being left with no caretakers. Watering him, watching his green, lopsided body grow larger, feels like contributing to something

bigger, stronger than myself. Maybe I’m not quite so incompetent, after all—not everything I touch dies.

A few weeks ago, one of my plants—a golden pothos with long, spindly tendrils—lost an arm. A 3-foot length of green dropped off suddenly with no explanation and lay on the floor in defeat. I rescued it and put it in a glass jar full of water on the windowsill, next to a miscellaneous row of other jars and bottles with clippings of plants— the beginnings of new plants to be. I used to be terrified of propagation; it felt like a profound cruelty, to cut a piece of a living being off, separated from its main body. But I’ve learned that it’s good for them, sometimes, to let go of the old. It helps them grow fuller, and the separated bits grow new roots, establishing themselves away from their old homes. Just recently, my poor plant’s arm has started sprouting a slim, white root covered with little hairs. Still alive, still trying its best to reach for water. One day, when I work up the energy, I’ll go out to buy some soil and give the arm a new home. A new adventure for my plant. One I still believe, despite it all, that I’ll be able to keep alive. That little scrap of unkillable faith in myself—my own tiny green leaf, curling towards the sky, thin white root digging through the soil.

I Can Say It For You

contemplating the (in)fallibility of our idols at samia

by Lily Seltz

Illustrated by elliana Reynolds

There was no second of purifying blackness, no raising of curtains or lowering of wires, no mechanized magic at all. Samia strode out to the microphone stand at centerstage, wearing her characteristic wide-eyed fishnets, mid-calf black leather boots, and a tiered white miniskirt that clung to her waist like a fluke.

Then there was her top. It was a tight little v-necked black thing just like what I bought last month from Urban Outfitters—was it the same one? I kept my eyes open until my vision blurred, and for a moment it was me up there, in that top; then my eyes refocused, and with a strange, almost relieved feeling, I ruled it out.

I couldn’t have known it, but what I was feeling then was the beginning of a breakage. A tenuous and contradictory marriage of ideas had enticed me to this concert floor—that paradoxical partnership between identification and deification; humanity and superhumanity; relatability and celebrity that has characterized my, and many other young people’s, relationship to music and its makers. As I looked up at the singer on stage, my whole body chilled. The marriage—or my faith in it—was beginning to crumble.

If you don’t count Spring Weekend, I had never been to a real (big, indoor, professionally produced) concert until a few weekends ago, when my housemates and I drove to Boston to see Samia. Samia is a big enough deal to book an 1800-person venue in Boston, but is still relatively unknown compared to the giants of her indie-pop genre (Phoebe Bridgers, Lucy Dacus, Japanese Breakfast, and so on). The occasion for the tour was her sophomore album, Honey , an 11-track display

March 3, 2023 5 ARTS & CULTURE

–

of young-adult angst and occasional delight, oblique anecdotes and crisp turns of phrase, rich guitar backing and the occasional wail of a synth, all guided by a voice of extraordinary depth and versatility.

My housemate Caleb drove us to the concert. There is some point in every city kid’s life where we have to start trusting our twenty-one-year-old peers to steer us down highways going 70. We don’t think about it, I guess. I leaned back in the passenger seat, queued Spotify’s “This Is Samia” on the aux, and turned the volume up as far as it could go.

We cracked jokes and sang along, all half-delirious with end-of-the-week relief and heady anticipation: we were driving to Boston for the joy and glamor of being part of a crowd, for the adventure, for the chance to hear the songs we loved played louder than the car speakers could achieve. But we were also going because some part of us believed—or some part of me did, at least—that Samia, age 26, knew something about life in its most nebulous construction that we did not. She had the answers. And maybe if I heard those answers straight from her, in her magenta, magnetic voice, well— what would happen, exactly? Would all my problems be solved? Would I magically get over my ex, discover a higher calling, be cured of all anxiety and ambivalence, and ace my history paper (for good measure)? Would everything, suddenly, make sense to me?

I could not have said any of this out loud, or even thought it to myself then, without laughing in derision. But there I’d been, riding shotgun, barreling north on I-95 to hear Samia’s next divination.

–

And here she was in front of the mic. Samia’s hair was half-up, half-down, and chased itself down to her lower back in a frizzy free-fall. Her chin stuck out to the left a little bit, like mine. I looked her up and down in disbelief: she was all bone; five feet and six inches of acute angles. She brought her hand up to cover her parted lips. Then she opened her eyes wide in a gesture of shock.

Samia, goddess, prophet of the night, looked at her audience—at least a thousand black crop-tops and fishnets and bony hands holding-barely-horizontal IDs—and said into the mic:

“What are you doing here?”

–

Some of you might understand it already. It’s that feeling when a song—through its eviscerating, clarifying precision—makes you cry, but right afterwards you

always feel better. From that moment on, you hold this singer responsible for your brief redemption. You invest in her a certain special trust. As we walked into the Boston venue, I held this trust for Samia; I thought she had the answers.

Let me try again. There is a natural human instinct, among all of us, although maybe especially among young people, to look for a guide, a God, or an idol. Music and the people who make it have always been well-suited to fulfill this desire for their listeners; in fact, the world of pop music is bolstered, if not altogether built, by this wish and the promise of its fulfillment. To set a group of words to music—to make them lyrics—invests in them a power that they would not have alone on the page. Set to music, words are imbued with the inevitability of melody and its resolution, and the more times a song is played and the more familiar it becomes, the more inevitable the melody, and thus the lyrics, begin to sound. In short, music is a reifying force; it has the capacity, from the music historian Richard Taylor’s book, to “weaken” the “intellectual resistance” of its listeners to any message that its lyrics hold. It is with this logic that I explain to myself the transfiguration that I witness between my first, and third, and twelfth rounds through any new album: a subconscious but undeniable shift from an interpretation of the music as the singer’s words to something more like The Word

The telepathic, or even prophetic, power that I and others my age tend to attribute to singers like Samia is reinforced by the sense that these artists are really just like us. This tilt towards “relatability” has already been analyzed to pulp by smarter people than me. But relatability, the process or feeling of identification with the artist on the stage, is immensely powerful. It offers a seductive comfort, a sensation of secret companionship. I haven’t got it all figured out just yet, which is a hard thing to admit, but when I listen to Samia, I don’t have to. She hasn’t got it figured out either.

–

But hasn’t she? Samia stood at center stage, stock still, the only sharp-lined thing in a swirl of white light. She was angelic. When she began to sing, her voice was as strong as I remembered from the recordings: rich, pure, entirely sure of itself. It soared into the crowd and we caught it and held it for a second and threw it back to her from our own, soon-to-be-exhausted lungs. She was our leader and we were her acolytes. Samia was a star.

When we seek to identify with artists, our goal is

not to dethrone them. We don’t want that at all—we want to have our problems shared, articulated, sorted, and then transfigured into art, so that all of a sudden they are both beautiful and meaningful, instead of ugly, useless, and mundane. What we really want is for the stage to be a mirror—but not just any mirror. We want a magic one, one we can peer into and see someone bigger than ourselves. Someone shinier and surer than who we really are.

Listening to music on AirPods or over a car speaker lets the mirror do its magic. Recorded music brings just the right amount of alienation from an artist herself, and from the visible production of stardom and “relatability.” Samia’s problems never take on substance or flesh: her trials are radio frequencies; her fraught subjectivity is a side-profile photo on an album cover. With struggles that intangible, it’s plausible to think that singing could be enough. That to understand and package and tell stories about what hurts might be all it takes to make those things disappear.

Here in Boston, it was different. Just as I had settled back into my enjoyment of the spectacle, Samia hiccupped. She stopped singing for a moment. She asked the band to start over, but in the brief, musicless pause, I looked up to the spotlights above her—to the machinery, to the source of the blurry white light. If the lights turned off, I realized, it would just be her (Samia, age 26, seven years older than me) and her bandmates, and some cords, and a drum set, and a thousand of us in the audience, waiting for her to show us the way. Here was the breakdown of the marriage; here was the paradox made visible. Samia did not have it all figured out. She was not—could not possibly be— both god and mortal, both superhuman and real.

And turning her problems into art seemed like a woefully inadequate solution. I turn my problems into art all the time; I storytell to my friends, I find patterns, I package. “I’ve got it!” I say, or, “That was the problem, the whole time.” And then in a year, or more often a week, I turn around and I say: “No, I was wrong.”

Samia is 26. What makes her any different?

What in the world were we doing here? –

If there was any answer to this, it was during “Stellate.”

Maybe ten songs into Samia’s set, she started singing one that I hadn’t heard before. For reasons that are peculiar to me—irrational, but legible, in my own way—the ballad cracked something inside of me that had been brittle for weeks. I started to cry.

They were good tears, tears that would make me feel better by their end. But for three and a half minutes, I was crying. My housemate Coco saw me stop dancing, and, wordlessly, pulled me into an embrace; we stayed like that until the last chord. What were we doing here? This. Maybe I was wrong to imbue Samia’s lyrics with the meaning that I did, but there is something different, and beautiful, in that collective investment in meaning.

What the meaning is doesn’t matter. Music gives us space to think differently—to interpret and respond to harmonies and lyrics in divergent, and even contradictory, ways. But ultimately there we all were, listening to Samia, agreeing on our basic affinity with it. Coco could not have known what I was thinking when “Stellate” made me cry. We never talked about it. But they were there all the same.

On the drive back home, I felt shaken, but happy, too. I sat shotgun and cued up a long list of songs in Samia’s genre—but none by her; we needed a break. Caleb was at the wheel, driving fast down the highway back to Providence, and I thought fleetingly about youth and infallibility and trust. Because we do have to trust each other, in the end: not as gods, not as idols, but as humans, our faces tilted up at a darkening stage.

ARTS & CULTURE

6 post –

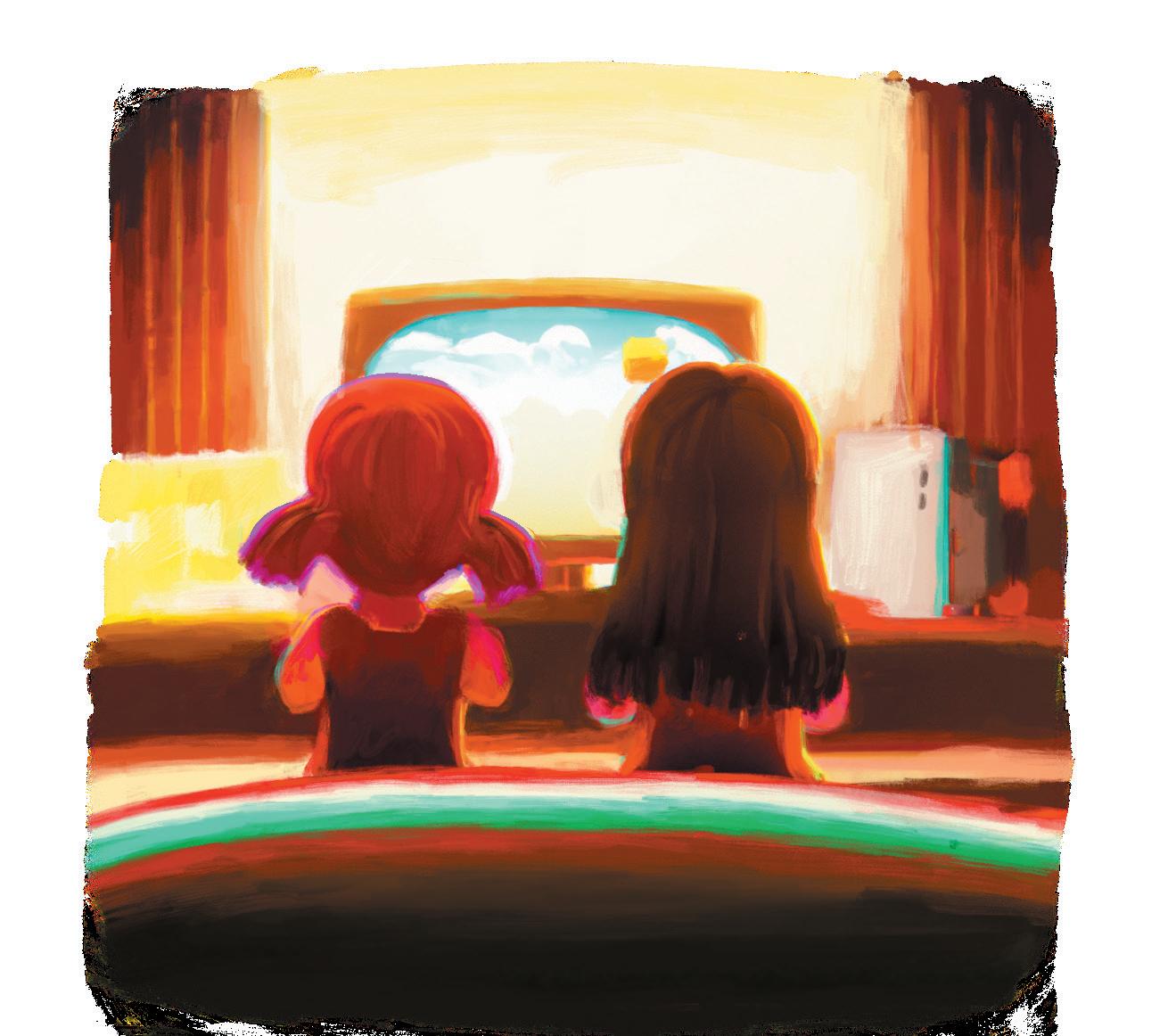

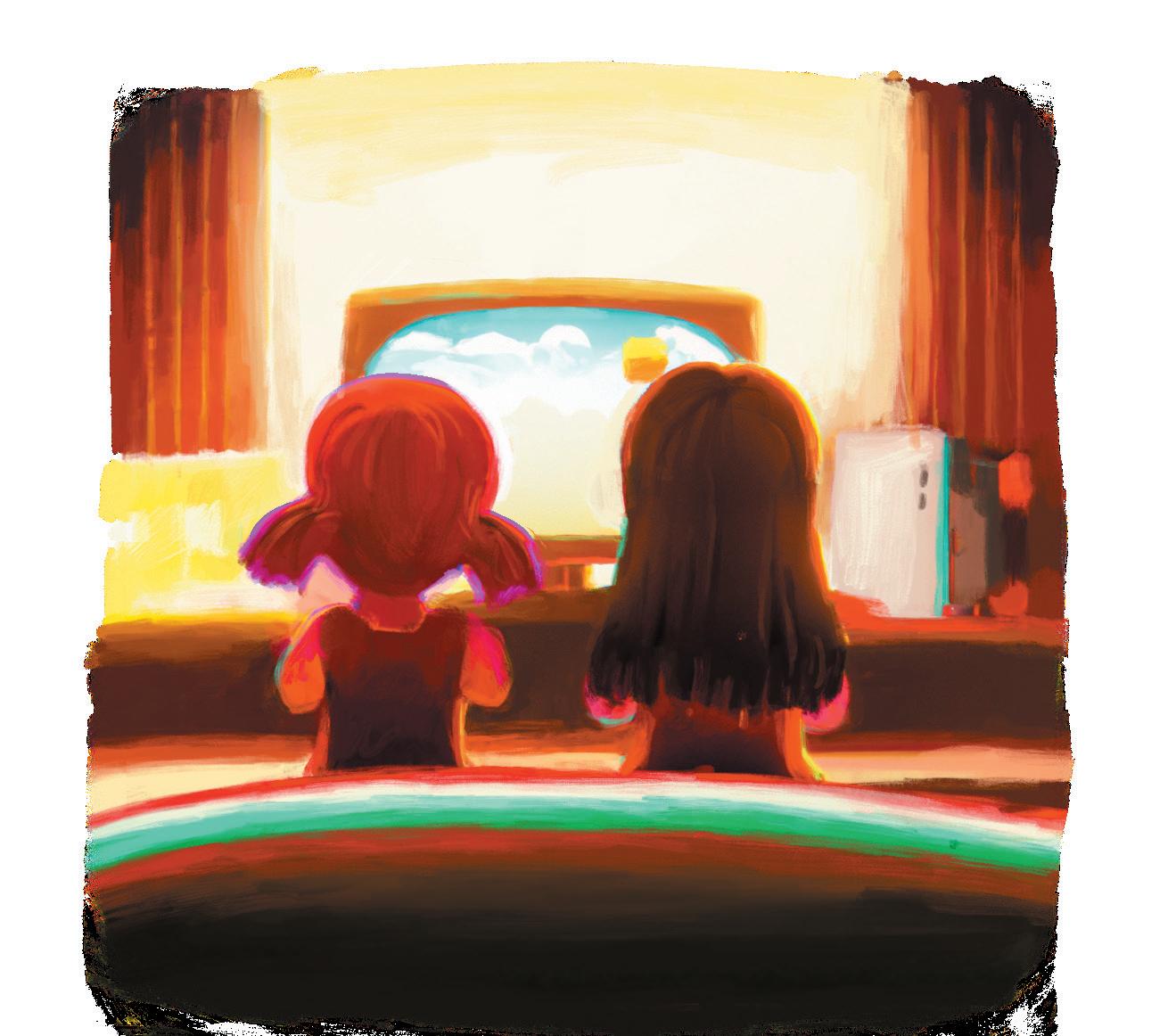

Immortality In The Virtual World

friendships today, and tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow

by Olivia Cohen

Illustrated by jeffrey TAO

My childhood best friend Lilah once discovered a copy of Super Mario Bros. on the hallway floor of our middle school and stole it. Neither her conscience nor mine stopped us from taking it to her house after school and immediately plugging it into her pink Nintendo DS. For the next few months, every time I went over to Lilah's for a sleepover, we constructed an elaborate pillow fort on the floor of her room and huddled around her DS, taking turns playing Super Mario Bros. She taught me how to climb the walls without stairs by ninja jumping. I showed her a green warp pipe that I found underwater, which sent Mario into a secret realm full of gold coins and venus flytraps. When I ran out of lives, it was Lilah's turn; when she ran out of lives, it was mine. I started to develop a Pavlovian rush of excitement in response to that Mario death sound effect, because it meant it was finally my turn to play. We passed the DS back and forth until either we or the DS ran out of energy—whichever came first. On particularly treacherous stretches of terrain, we whisper-sang a spirited rendition of Dory's "Just Keep Swimming" from Finding Nemo, which was frequently cut short by the sound of her dad's footsteps pounding up the stairs as he rushed to reprimand us for being awake past our bedtime. Lilah would quickly stash the DS behind her pillow and we would pretend to sleep, squeezing each other's hands to keep from laughing.

Eventually, Lilah lost the charger to her DS, and our midnight adventures through Mario's pixelated kingdom came to an abrupt end. But we didn't mind, because we had found a game to take its place: Webkinz, a virtual world in which we could take care of pets that had real-life stuffed animal counterparts. On Webkinz, Lilah and I cultivated online families together, looking after our pets like they were our own children: We fed them fruits and vegetables, celebrated their birthdays, furnished their homes with toys and rocking horses, and dressed them in matching outfits. We each had bought the same golden retriever from Hallmark; I named mine Charlie and she named hers Sophie. After some thought, we realized that the only logical way to unify our disparate Webkinz families was for Charlie and Sophie to marry; that way, all of our other pets— her heart-covered frog, her turtle, Michael, and my red robin, Alex—could be half-siblings, with Sophie and Charlie as loving parents. So, on the day of their union, we logged into the website and positioned Sophie and Charlie so that they were both standing in Lilah's Webkinz backyard under an animated white trellis and assembled our other pets around them. Simultaneously, in the real world, we held a ceremony on the floor of my parents' bedroom, in which we lined all of our Webkinz stuffed animals in rows, Charlie and Sophie positioned at the front of the room. Once the two animals had said their heartfelt vows and their union was sealed, Lilah and I held an hour-long Miley Cyrus dance party— partly to end the wedding but mostly to celebrate the fact that, now that our videogame children were married, we were technically sisters.

Every day after Lilah's mom picked us up from school, we ran straight to the desktop computer in her dad's office to play Webkinz. She sat in his big black

swivel chair and I perched on its arm, waiting eagerly for her to log into her account. Just as we had done when we played Super Mario Bros, we traded off gamefor-game. It was like a choreographed dance; both of our eyes stayed glued on the screen, leaning forward, tongues poking out, then an exasperated sigh and we changed positions. But we never grew tired of playing this way. It was a familiar cadence, the rhythm that defined our friendship.

Because of my relationship with Lilah, I found comfort and familiarity in Gabrielle Zevin's novel Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, which tells the story of Sadie and Sam, two friends who meet as children, grow apart, and then meet again in college, ultimately deciding to go into the game-designing business together. Zevin uses a story about video games to highlight more universal aspects of the human experience: the unpredictability of life and the intimacy of friendship.

Sadie and Sam meet for the first time at 11 years old in the kids' rec room of a hospital and bond over Super Mario Bros.—just like Lilah and me—and slowly open up to one another as they continue to play. Sam is recovering from a car accident which crushed his foot, and Sadie is in the hospital visiting her 13-year-old sister, who has cancer. When Sadie tells Sam she'll wait to play until his character is dead, she realizes that she may have come off as insensitive to Sam's condition. Sam, still playing, says, "This being the world, everyone's dying." He then hands her the controller: "Here. My thumbs are tired anyway." For these children, who each bear heavy burdens in their personal lives, it is easier to plunge into a virtual world, to immerse themselves in the rhythm of the gameplay, rather than express themselves explicitly. I found parallels to my own relationship with Lilah in Sadie's relationship to Sam. Particularly when we were young, it felt more natural to channel our social energy into an external task than to focus it on one another. We learned about each other through our unique styles of playing and choices rather than through conversation: Lilah could play the same game for hours without getting bored or giving up, and she found everything cute—monsters, animated sunflowers, Mario's exclamations ("Let's-a go!", "Mario number one!")—and she was always one to save her in-game currency, whereas I was always bordering on broke.

It's been 10 years since Lilah and I lay on the floor

of her room with her DS, but we still play Super Mario Bros. on my older brother's Nintendo Switch when I see her once a year. Something about that unified focus on a task has a neutralizing effect, turning back the clock until we're back to chanting just keep swimming, as if we'll have to scramble to turn off the game as soon as we hear her dad's footsteps coming up the stairs. Zevin's story addresses the notion that friendships which begin in early childhood almost always drift apart— sometimes for a few years, sometimes for many. Sam and Sadie's childhood friendship ends at age 12 and then rekindles in college, when they decide to start making video games together. Their paths remain intertwined as they work as business and creative partners together until their thirties, when Sadie moves to Boston and Sam remains in Los Angeles. When Sadie and Sam finally see one another again after years apart—first in college and then later in middle adulthood—they are still able to connect with one another, slipping back into that back-and-forth rhythm of gameplay. Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow is a reminder that the routine and the invariability of gaming worlds can be a blissful escape from the real world, where relationships are messy and turbulent, where stories get cut short.

At the end of fourth grade, Lilah moved to Oklahoma. When she left, Lilah gave me her username and password to Webkinz, and when I missed her, I would log onto her account. Our friendship taught me that when you experience art with someone—whether it be a movie or a song or a video game—the memory of them is crystallized in it; the art becomes a way to access them. Sometimes, I knew she'd logged on recently too because I could see that the Wheel of Wow had been spun, the daily gem had been mined at the Curio Shop, and Vinny the heart-covered frog had recently been fed his favorite food (candied rose petals). In those moments, I could picture her, wild blond hair pushed behind a pink headband, eyes laser-focused on the screen in front of us. Momentarily, I found myself next to her again, waiting for her game to end so that we could switch places and I could play. There was something so comforting about the immortality of that online world. Even if you let your avatars go unfed for years, they never died. Their house was always just as you left it, your progress was saved, the graphics were never updated. It was a relief to return to a world where everything stays the same.

ARTS & CULTURE March 3, 2023 7

Far From the Thrifting Crowd

vintage shopping and self discovery in Bologna

by Sean Toomey Illustrated by Emily SAXL

by Sean Toomey Illustrated by Emily SAXL

The rain waltzed through the antiquated, beige porticos lining the cobblestone streets. Soaked as I was, there was respite in the distance, peeking through the sun-dappled smog: Humana Vintage in all its vanityinducing glory.

The thrifting here in Bologna has been a real treat for a clothing maniac like me. In the past week or two I have found more classic pieces than I have during my twenty years in the United States. As much as I’d like to gatekeep my secret spots, I wanted to give a brief rundown of the thrifting scene in Bologna and my experience shopping in a different vintage culture.

First we have the ever popular, ever diverse Montagnola market that sprouts up at the piazza every weekend. Here the market-goers’ flesh melts into fabric as you encounter bazaar after bazaar dedicated to everything from the uniquely American Levi’s, threefoot-high piles of sweaters, and selections of Burberry trench coats for pennies on the dollar. My trips here have been fruitful for the tweedy professor/ “we-haveDrake’s-at-home” style that has overtaken my outfits: it’s giving “Indiana Jones when he’s teaching at university,” and I can’t say that I’m not enjoying it. A little trick for sport jackets and coats is to check in the jacket’s interior pocket for a size tag that might not be apparent

at first glance. Sizing and inconsistent pricing remains a problem for most of the stands, but taking the time to try on and feel each piece you're considering (along with a healthy dose of haggling) is a process well worth the effort.

For a more structured thrifting experience, I would recommend a visit to Humana Vintage, as I believe it to be the best vintage store I have ever shopped at. The inside is a decade-bending dream. Mannequins stand dressed in, at minimum, five layers of every style known to man, and the space is filled with clothes from the 60s to the 80s in every color. I have found a variety of sport jackets, big tweed Balmacaan coats, and a litany of wear ranging from the bell-bottom expressions of the 70s to the Armani inspired 80s and 90s. I also recommend their large collection of tastefully wide 70s ties (yet another step towards my Teddy Pendergrass phase). The pricing is comparable to the open air markets, but on a good day you can find amazing deals for very cheap rates. During end of season sales, there were days where every piece in the store was five euros, and the day after that, three euros. Needless to say I have been buying blazers like a maniac and will probably need a second suitcase as a result (I’ll cross that bridge when I get there).

What really surprises me about the thrifting

here is the sheer availability of everything. Back in America, in-person thrifting was, for me, disappointing: Everything within a reasonable distance was filled with clothes either too big, too poorly made, or too expensive. I remember when my boyfriend and I trekked through the curated shops of Nashville, we encountered the poisoned remains of the childhood of 60-year-old men: stunning oeuvres of leather and suede tassels and two hundred dollar band t-shirts for Bad Company. While the specter of the 70s and 80s remains present in much of the clothing in Italy—namely the low buttoning points of the jackets, the top-heavy Armani-style jackets lining every shelf—the options available outclass American vintage stores in price and creativity. The coat stand at the vintage market alone had more coats than I have ever seen in my entire experience in the United States.

Thrifting is a collective hobby for the clothing obsessed, and I have to say that Bologna is some of the best thrifting that I have seen in my brief, glen-plaidcloaked time on this planet. Vintage shopping is always an environmentally preferable alternative to the endless cycle of fast fashion and internet aesthetics so go forth and seize your thrifting finds! Happy hunting!

ARTS & CULTURE 8 post –

Crossword

by Will Hassett

“In these moments, I let myself fade away a little, lost in thought and in the smell of soft, sandy, salt. Sometimes, I run up to the edge of the waves, daring their icy tongues to lick at my feet. Other times, I’ll write words in the sand, letting my thoughts be swept away by the sea.”

—Liza Kolbasov, “Gone in a Moment” 03.04.2022

“This nonsense that I spew, these absurd yet allencompassing metaphors, are the fabric of my existence.”

—Ellie Jurmann, “Unfinding Meaning in Everything”

03.05.2021

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Kimberly Liu

FEATURE

Managing Editor

Alice Bai

Section Editors

Addie Marin

Klara David -

son-Schmich

Lilliana Greyf

ARTS & CULTURE

Managing Editor

Joe Maffa

Section Editors

Elijah Puente

Rachel Metzger

NARRATIVE

Managing Editor

Katheryne Gonzalez

Section Editors

Eli Gordon

Sam Nevins

LIFESTYLE Managing Editor

Kimberly Liu

Section Editors

Kate (Jack) Cobey

Daniella Coyle

HEAD ILLUSTRATOR

Connie Liu

Emily Saxl

Ella Buchanan

COPY CHIEF

Aditi Marshan

Copy Editors

Eleanor Peters

Indigo Mudhbary

Emilie Guan

SOCIAL MEDIA

HEAD EDITORS

Kelsey Cooper

Tabitha Grandolfo

Natalie Chang

LAYOUT CHIEF

Alice Min

Gray Martens

Layout Designers

Julianna Chang

Brianna Cheng

Anna Wang

Camilla Watson

STAFF WRITERS

Dorrit Corwin

Lily Seltz

Alexandra Herrera

Liza Kolbasov

Marin Warshay

Aalia Jagwani

AJ Wu

Nélari Figueroa Torres

Daniel Hu

Mack Ford

Olivia Cohen

Ellie Jurmann

Andy Luo

Sean Toomey

Marlena Brown

Sarah Frank

Emily Tom

Ingrid Ren

Evan Gardner

Lauren Cho

Laura Tomayo

Sylvia Atwood

Audrey Wijono

Want to be involved? Email: mingyue_liu@brown.edu!

LIFESTYLE March 3, 2023 9

5 6 7 8 Across Some may have it, some not so much Susan, but not Sue or Suzy Iridescent rocks Respond, reply, or retaliate Industry for many a CSCI grad 1 5 6 7 8 Down Indian currency One hit by a falling apple, some say Nothing at all A grate piece of fuit? Style, shape, or set

4 5

1 2 3 4

1 2 3

by Sean Toomey Illustrated by Emily SAXL

by Sean Toomey Illustrated by Emily SAXL