BEHIND THE COVER NAOMI DESAI

As a woman of color, rage is an emotion that I experience all the time. Female presenting people are never allowed to express rage and we’re ridiculed when we do. Rage is such a charged emotion and from a feminist point of view it has the potential be motivation for systemic change. We need to normalize talking about the imbalances of power in our society and rage is the perfect topic of discussion for that. Who is allowed to express rage and what are they trying to accomplish with it? Rage is a defense mechanism and marginalized groups deserve to express it.

I wanted to explore the electricity and angst of rage in the cover through a feminist lens. Inspired by Wong Kar-wai’s use of lighting to depict emotion and Petra Collins' feminist photography, I studied their work very closely before the shoot. These photos are part of a larger body of work that I’m creating to explore the visual language of feminist rage.

I would like to give a huge thank you to Erin Shannon, who is always willing to be the model and muse for my photography projects, and Avery Slezak, for helping with lighting and carrying out my vision.

4 10 12 14 18

anger: designed by

yi yun luo8 6

axe throwing, unbridled rage, and a good arm by

reace dedonspeak to me/what’s wrong? by

alexis m. howellsfeminist rage by

naomi desaicaged by rage: are rage rooms helpful?

by alex kaselto the conversation i overheard -- dekalb ave, late august -- walking home by

ella ferrerowall of shame by tien

servidio20 22 24 26 28 29 16 30

in his, i saw mine by alexandria anne

on the outside of the circle by

paige danielselodie has nothing to say by elodie

hollantthe hurting world: designing beyond diametric relationships by nina

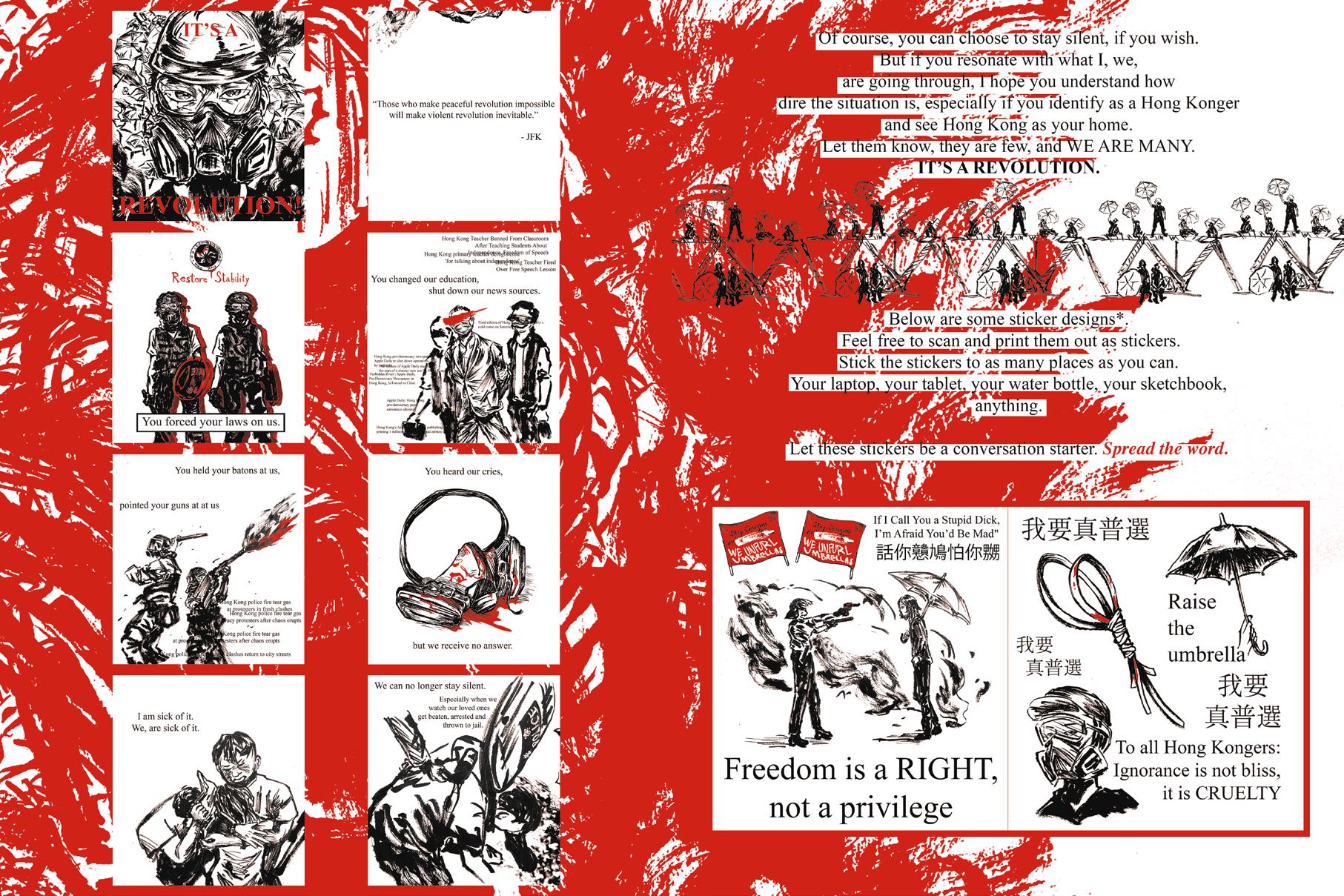

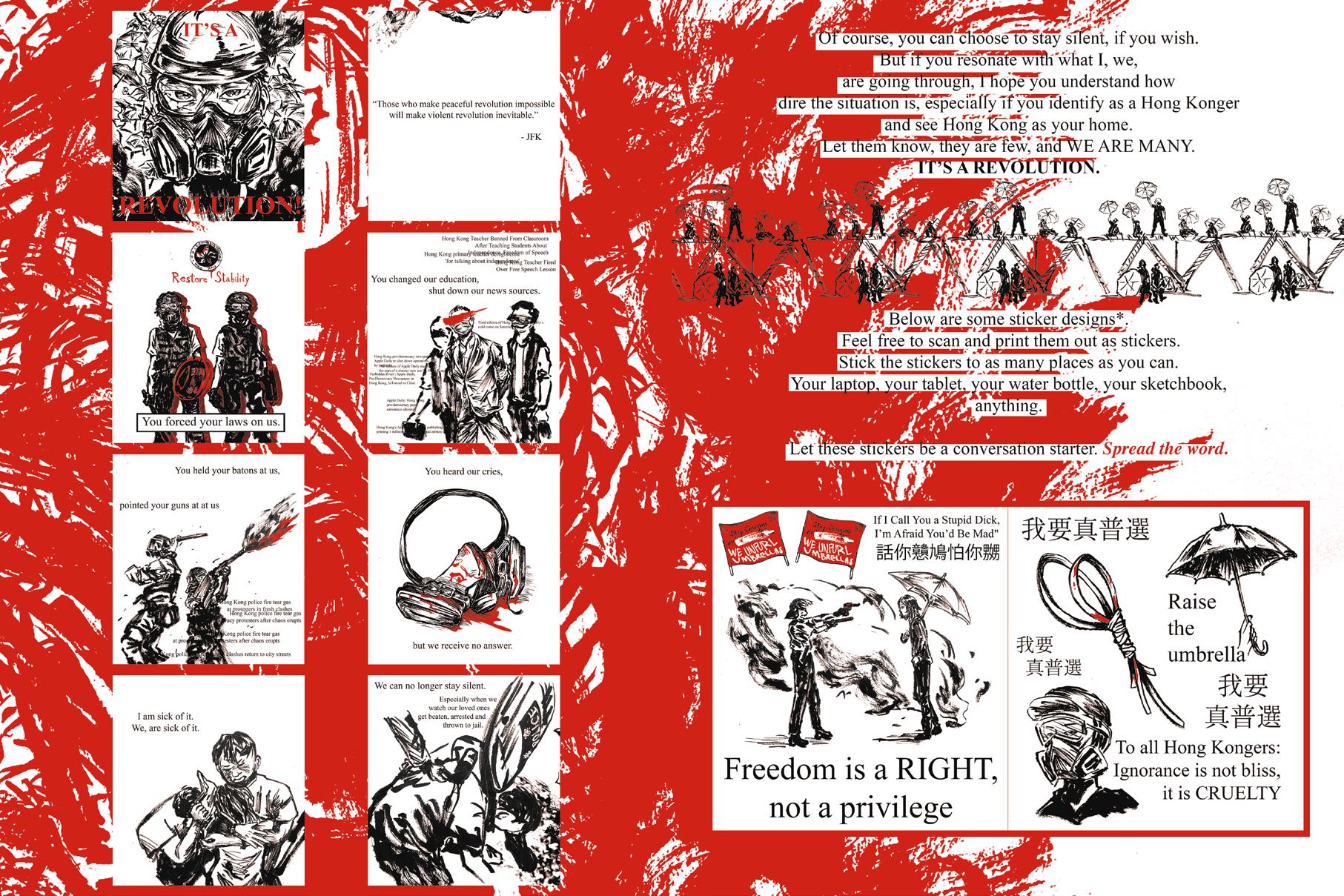

luit’s a revolution! by an anonymous hong

kongerhey, connor by

jordan anna torresrage crossword puzzle by mage sensitive machismo by seb

torrensANGER: Designed

“She is a good girl,” my third-grade teacher said to my parents. “She never gets upset, and she doesn’t disrupt the other students. She is a pleasure to have in class.”

It didn’t matter to my teacher that I was non-disruptive because I did not speak a word of English, or that I never got upset because I learned the consequences of upsetting authority before I learned to walk. It didn’t even matter to her that the “parents” that came to my parent-teacher conference were not my real parents but longtime family friends that stepped in to shield me from child-protective services. My real mother worked a 16-hour flight away, and my father left because he preferred a son to a daughter.

What mattered to her were only two things: I was quiet, and I didn’t disturb the classroom’s harmony. A grade of B+ for social behavior. Not outstanding. Not delinquent. A pleasure to have in class. She shook my “parents’” hands and asked us to wave the next set of parents and child in. She did not remember my name by the time I left for my next school at the end of fourth grade, and she never met my real mother.

High school came, and with it, the debate club. I watched as a competitor-turned-peer-turned-friend, award in hand, and gave a fake Oscar speech, complete with tears, in front of a crowd of cheering fourteen year-olds. A new core lesson was unlocked: in high school, emotions were everything. Extravagant displays of emotion were how you won debates, teachers’ recommendation letters, and friends. Everyone wanted to be beside an ever-pollyannaish paragon of teenage cheerleader-esque altruism. A pleasure to have in class went from quiet to loud.

I picked up a stack of sociology books at the local public library on my way home from the event. At the next conference I attended, I laughed and cried and shouted with the best of them. Each night, I put my new award down next to my shoes by the door and went back to my monotone. Photos from the day I graduated high school show me laughing and joking for hours with my friends and teachers. My search history from that day shows me taking four different self-tests for psychopathy.

In the first year of architectural design, students are taught to break down everything they think they know about architecture to

unlearn assumptions of what is “natural.” Only when you wipe the slate of preconceived notions clean can a new, truer understanding be learned. For me, rage was the first of those notions to be wiped clean. I learned how to control my temper before I learned to stop myself from crying or laughing. I learned how to laugh and grin. I can even make myself cry from time to time to release those vital endorphins that serve as an emotional shot of five-hour energy during the worst days of finals. Rage, the first to go, is the last to be rediscovered, partly because it is difficult to get a positive feedback loop on anger - no one craves being the target of rage, experimental or not. And partly because the discovery of true rage necessitates a surrender to the ecstasy of the sentiment, and that is in direct contrast to a polished, learned methodology,

In an effort to find rage, I slam my hands on the keyboard. gaqjkhgHIJOKp:KOJIHCUGYJZXXKJZGXJKCGvJKjkdgfhjwrolihvksnfd.

That was a lie.

I picked each of these letters out, one by one, with enough variety that it would pass for randomness - randomness vanishes when the human mind is able to create a pattern from nothingness. Enough balance of capitalization and lowercase to reinforce the forcefulness of the lack of statement without creating a norm, enough symbols to imply that it is a full keyboard, without breaking up the cohesive line format. Long enough to fit across the page and short enough to avoid making a second row. Spontaneous expression borne of years of reading on emotions. And then I will hand this piece to the editor with this line highlighted to verify that the false rage is contained enough, yet artistic enough, to merit being published. If this paper isn’t, all it would trigger is a sigh as an elegy to lost sleep, a quick rescheduling for rewriting, and a courteous email thanking her for her comments.

I wonder about the girl I cannot remember who wears my face and bears my name, who had every reason to be angry before she let third grade take her words and high school teach her new ones. I wonder what she would write, if you asked her

for a line about what rage is. Perhaps it would be GGGGHGGGG, a string of letters that she did not learn to pronounce properly until years later. Perhaps it would be RAGEANGRY in the shaky hand of a beginner. Are these arrangements of letters, far more controlled and less randomized, any more of a representation of rage than the learned key smash? At what point does rage simulacra eclipse rage as a feeling?

Or perhaps, she will write nothing at all, for writing is already a feeble attempt at defining the undefinable. Perhaps she will tilt her head back towards the sky and allow the emotions to sweep over and spill out until they tear her vocal cords raw and lock her muscles in a stone-vice grip. Perhaps, just perhaps, that will finally allow an older version of herself to speak without the fear of consequences for upsetting authority.

I tilt my head back and open my mouth. All that comes out is a yawn. It is 2:47 in the morning on a Wednesday; all around me, the campus is quiet. My suitemate is in the next room, sleeping to recover from her midterms. Even if I am still capable of screaming after a decade without, she would, in her kind-hearted concern, come knock on my door and ask me if I am alright because this behavior is unlike me. I never get upset, and I don’t disrupt the other students. I am a pleasure to have in class.

I wish that if I told her that version of me was a lie, I would be speaking the truth.

Because although I believed and hoped that I had once been capable of rage before unlearning it, the truth is that I remember nothing about ever having been truly angry. I look at the girl that wears my face and bears my name; if she could rage as much as she wanted to, would she?

Would I?

Axe Throwing, Unbridled Rage, and a Good Arm

BY REACE DEDONIt was in January of 2022 that I threw my first axe. On an inescapably rainy weekend in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, myself, my family and my girlfriend drove up and down the main street looking for something to fill our time. Ruling out racially insensitive dinner theatre and vivid reenactments of the sinking titanic, our options were slim. Eventually, we settled on two hours of controlled indoor violence at Appalachian Axe Throw and Xtreme Cornhole.

The first fifteen minutes of the two-hour time slot moved slowly with the instructor’s introduction to the weapons. Yes, weapons and not tools, as I was corrected. I didn’t appreciate his patronizing tone, but the respect with which he referred to the slew of knives, axes and throwing stars was something I would grow to understand.

We were taught the proper motions: two hands on the axe and feet together. Then, the right foot steps back while lifting both hands over the head. Finally, take a step forward and launch. He ran each of us through a practice run, our axes aimed at the splintered target before he left us to wreak havoc on our own. My father and brother caught on quickly, both experienced from their years of hunting and camping. My mother silently took her turns, mostly resigned to her role as a proud supervisor, and slung her axe with impressive precision and hardly a word.

My partner and I took turns in our shared lane, quick to catch on to the movements but slow to perfection. It was intoxicating

to watch the blade lodge itself so tightly into the splintering target. With each throw, a piece of it was chipped away, and with it our inhibitions.

We alternated throws. Axe, then dagger, then throwing star, then back to the axe. At first, we cheered each other on. It felt fun and silly. When we missed, we laughed. When we hit the target we clapped. We carried on that way for a while, but before long we grew silent and waited impatiently for our own turn.

The dry wood of the axe handle was becoming familiar in my palm, and with each throw a burdensome and uneasy feeling began to rise to the surface. The weighted drag of the axe and the slender stealth of the dagger was empowering. After thirty minutes, we’d improved, hitting the target majority of the time and inching closer to the center.

With a dagger in my hand, I was reminded of a sermon I attended with my grandmother when I was nine years old about the sinful nature of anger. “The Lord created you in his image, and to be angry at all is to be angry at God for what he created,” the pastor declared. I remembered telling my mother what I’d learned that day with the hopes that she’d take it to heart. I remembered begging God to let my parents go to heaven, even though they got angry sometimes. Despite having abandoned religion long before my time at Appalachian Axe Throw and Xtreme Cornhole, I felt the pangs of those words still resonating in me. I realized how much I had internalized those teachings.

My stomach tightened as the sickeningly addictive feeling of rage was unleashed—an emotion I had pushed down for too long—and with it came shame.

To be a woman is shameful, so it’s taught. Simone de Beauvoir famously said, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” and I became more of a certain type of woman on the day of that sermon. I learned that I was meant to be resigned to silence, and what was expected of me as a woman of God. It would be another six years before I learned to be a different type of woman, or that I didn’t have to be a woman at all.

At the age of fifteen, I realized I was gay. At the age of nineteen, I realized I wasn’t cis-gendered. After all the time I spent unlearning my youthful definition of womanhood, so much of what I’d let go of was still lingering in my subconscious. So rarely did I allow myself to explore these feelings that it took a sharpened blade and a strong enough throwing arm for me to finally accept rage as something other than sinful.

The tense silence between my partner and I was stark compared to the jovial hollering from my father and brother in the stall next to us. After an hour, my partner and I were rolling our shoulders and cracking our necks. We knew that our arms would be painfully sore the next day, but the throwing had become lethargic and we felt actualized in our shared discomfort.

I watched my partner release three blades consecutively, and I was reminded of the world. Her eyes stayed trained on the

blue rings in front of her and I noticed her firm grip on the tips of the blades before she flung them. She didn’t smile. She barely blinked, and when each of those blades lodged itself into the target she turned to me silently and nodded. In her eyes I saw the memories I knew of her childhood. The weight on her shoulders and the pain in her eyes had been carried with her through a strict catholic upbringing, and I realized that we were both understanding how we’ve been divesting ourselves of feeling.

I was also reminded of our visit to Dollywood a few days prior. It was late into New Year’s Eve. The park was closing soon, and visitors were thinning out. We posed together for a picture after most of the crowd had dispersed. We held hands and shared a chaste kiss. Around us, children’s eyes were shielded. A passing couple stared and whispered to one another while shaking their heads. We didn’t talk about the interaction afterwards because it felt better to ignore it, but with a throwing star in my hand I thought about the picture we had been taking. I thought about everything outside of the frame and how my unseen hand had clenched the back of her jacket in grief. I was reminded who we were taught to be, and who we were in that moment, however different that might’ve been.

I left Appalachian Axe Throw and Xtreme Cornhole angry. Rain pattered lightly on the car windows. Illuminated manger scenes whizzed by every few miles, and I squeezed my partner’s hand tightly.

Speak to Me / What’s Wrong?

By Alexis M. HowellsDid I do something? Because when I said Hi coming through the door, you ignored me. I understand if you were focusing on the TV, but, really, did I do something to upset you? I can take your honesty, believe me. I prefer it, actually.

You’re slamming cabinets again. I flinch each time. Easy indicator. Something is definitely wrong, you’d think. I try again. You double down, No, I’m not mad at you, so, clearly, I’ve done nothing to unnerve you, right? I take your word for what it is because I believe you are telling the truth. We go about our days, business as usual.

Oh, so you’re giving me the silent treatment now. How fun. I know neither of us is enjoying this. We used to enjoy a lot of things together: Late-night tv, meadow reports, going out. Now, it’s just awkward. I’m scared to speak. I feel like I burden you with my presence. Instead of your eyes, it’s your general direction I look to. I feel weak when our pupils connect. Frozen, stuck.

Maybe you’re just having one of those days. Nothing is going your way. But these days have turned into weeks, and still, there’s no change. I continue with kindness because my mother raised me right. But, you, on the other hand, continue your hostile plight. How was your day? Fine. Lots of work? Yes.

I’m so frustrated. A hermit, I’ve become. I’ve locked myself in my room, distancing myself away from you. Are you doing this on purpose? To make me angry? It’s working. I could throw a brick through glass and leave the shards for you to step on.

Everybody hates me, you complain. I wonder why… The irony defeats me. I roll my eyes after every other word. What makes you think I want to listen to your problems when you’ve created so many of mine? When you find yourself in the middle of complaining about others, at one point you should ask yourself, “Am I the problem?” Because most of the time, you are. Check yourself before you wreck yourself, they say. When you blame everyone else for your own issues, you’ll run out of people to blame. Woe is you.

I don’t have patience for your passive aggression anymore. Either I did something or I didn’t. Tell me straight up if I have, and I will place my apologies where they’re due. I can’t read your mind, and frankly, I don’t want to. I’d rather stab myself in the eye than immerse myself into your narcissistic neuroses. Consoling you is not on my agenda today. Maybe it was a month ago, but I won’t put myself into that position again.

So, say something. Tell me what’s wrong. Free me from these silent chains. The first step is to say, I’m upset. I’m your friend. I want to help. Don’t avoid me. Face your problems. Or, at the very least, don’t make them mine. I won’t know unless you say something.

Speak to me.

Art By Ashely Yu IG: @mono-xlan.art Twitter: @mono-xlanI’m so fucking angry. Literally all the time. About everything.

But I’ve been brainwashed by society to ignore all this anger and to meditate and journal my feelings away. When the only guy in the classroom full of women gets the most praise from the professor, when I think about how few women of color have leadership positions in the design industry and every time I get a New York Times notification that another fundamental right has been taken away from me — I am livid. This is feminist rage and it’s a powerful tool that has been ignored for far too long.

Women and femme-presenting people cannot express rage or they are written off as overly emotional. Rage is never taken seriously when it’s not coming from a man, but it’s a completely valid reaction to the oppression we face every day. Being a marginalized person at Pratt makes it hard to not be angry most of the time. Pratt’s COMD student population is overwhelmingly female and femme-presenting but our industry is dominated by men.

It’s incredibly empowering to be in a classroom where the majority of people aren’t male. So it’s extremely crushing when the professor, who is usually a white man, gives the one male student in the classroom the most praise. Even if we spend hours and try our hardest, there is no breaking the testosterone-infused bond between the men of the classroom. This creates a studio culture where it’s acceptable for men to produce lower quality work yet receive equal or even more praise than everyone else.

At Pratt, there’s only one female professor of color teaching graphic design intensive next semester. I cannot keep learning design from white men who put a male, eurocentric lens on my work. If we want to see any change in this industry, Pratt cannot keep hiring only white male professors across all the majors. White men dictate everything we do: they control our rights, the clothes we wear, our safety–– everything. Feminist rage is the only response to this lack of control. It’s a call to action.

Feminist rage is what motivates everything I do. Every written piece comes from a place of rage. It’s this heavy feeling in my chest that fuels my work and creative practice. Rage within a feminist scope isn’t working to elicit fear, rather, it’s a passion for change that encourages me to ignore the status quo and shift the way we think about the patriarchy’s expectations for women. This anger that I have is my biggest motivator and microaggressions, slurs and politics are all fuel to my fire.

Feminist rage has taught me to be an instigator and question everything: why does this make me angry and what am I going to do about it? This is why artists and designers are so important and why we need to elevate oppressed groups. Our insight and perspective is the key to making a more equitable community. Knowing you don’t have a professor’s full respect and attention because of your gender or race is unacceptable. The box that the patriarchy pushes me into is extremely claustrophobic and feminist rage is what is bursting me out.

This rage is power; don’t let it go. Next time you’re angry, use that energy to catalyze change.

Caged by Rage: Are Rage Rooms Helpful?

When this theme was introduced, one of the first things I joked about was going to a rage room. While they’re certainly not cheap–from nearly $40 per person for just 30 minutes of smash time to upwards of $125 per person for 45 minutes–one website advertised, “our rage room helps cure your anger.” Hallelujah! Was this the answer I’d been looking for?! Forget journaling, running and therapy (just as expensive)–was the solution to break sh*t? Based on further research and advice from a plethora of psychologists, rage rooms are actually not a constructive way to deal with anger in the long run.

Rage rooms were created by companies in Japan in 2008 as a way for employees to release their emotions in an intense period of time, stemming from the Freudian idea of catharsis.

By “fixing” employees as quickly as possible, these companies could capitalize on their increased productivity. Some still believe in the benefits of catharsis, but modern psychologists identify aggressive explosions to reinforce feelings of anger. What’s more, the recent outcome of studies dating back to the 1960s show that if people learn that acting violently is okay in one situation, they may do so at other times. Especially for people who have engaged in destructive behavior in the past, rage rooms can reinforce negative coping mechanisms.

It’s impossible to touch on cultural norms around anger without thinking about gendered expectations. Here’s a statistic to unpack: according to Vantroy Greene and other rage room owners, up to 95% of their visitors identify as women or

Words and art

By Alex Kasel

By Alex Kasel

gender-nonconforming (USA Today/Vice). Why is that? Society teaches men that anger is the only valid form of emotional expression while at the same time discouraging non-men from expressing their anger (if they do, they risk being dismissed or villainized). A study from Southwest Missouri State University, however, showed that non-men are as angry and act on their anger as often as men. They also found that men did not know how to proceed when made to suppress their anger, while nonmen were more able to control immediate responses to anger. So though rage rooms might be enabling for those inclined towards violence (statistically: men), they could be a safe way for non-men to express themselves in a way they have never been free to experience.

Ultimately, a visit to a rage room may offer brief relief but it won’t solve your deep-seeded rage. Anger is a natural response to situations in the world around us and we aren’t taught how to express our anger in healthy ways, the underlying causes of anger or that it can be a catalyst for positive change. Often a facade for deeper emotions including inadequacy, determination, exhaustion, fear and loss, anger is complicated. Dealing with these feelings can call for mental and written reflection, adjustment of thought patterns, open communication, plans of action and most importantly, time. This kind of change takes practice and is never “finished.”

To the Conversation I Dekalb Ave,

BY ELLA FERREROTaken from the Rib

Of a poor man’s Adam I am Pratt Pussy. I am laughing at Pratt Pussy. There is nothing wrong with women I just Want to avenge that original sin/sickness/my own sexual desire (Women are the disease of Pureness, we must remind them of this Unholy unholy). She bit

The apple first I only watched (observed, bit

The part not touched by the flesh, hit the core). The snake Looked at me with human eyes he laughed, this Is the woman you love. This is your mother/sister/daughter/love/sex. I cannot help it (I cannot help myself) around these girls they Are apples I bite into them, I whistle at them, Ciao baby, I beg for their names on the subway, I Am following her home, I am Grabbing the green ones. I leave when I Hit the core. It is too bitter, the seeds may Kill me. I do not know what woman means, I can only Point at what they give me. Pieces of fruit, their ripeness Does not matter. They are bags Of organs and I am hungry and plucking. I call them by their Stickers. Fuji, Pink Lady, Pussy.

I bit my ears when I heard this Pratt Pussy. I am a girl touched by older Men, ignored by dad, whistled at, my body dissected In boys’ group chats. You say you are a feminist. I Say that you laughed along. You let your boy Reduce me to body parts. You let your boy

Define what a woman is, when I am not sure. I know that she is not Pussy. I know that men are gifted Bodies in their own heads to Fulfill the things they cannot tell mom About. I know that my body is a language That you cannot speak, only Point at the rhythm And laugh at the accent.

ART BY THAÍS CURVELO

IG: @THHHACURVELO

Overheard -Late August -- Walking Home

In his, I saw mine

Words and Art By Alexandria Anne

His eyes meet mine and suddenly I am singed swollen skin, blistering with spite. I have touched that fire, recoiled from that burning shame, curled up on myself like a snake with a cut tail.

You may see Beelzebub and all the bad he brings, but I see a wounded child, still stinging from the backhand of being refused. Desertion birthed this retribution.

How can you not feel for that which clearly aches?

If you can look into his eyes and not know the excruciating sharp swallow and burning red throat, the nails that break skin with all the force of shame and sin, the belittling presence of entirely aware abjection;

Have you never loved something that turned from you? Or worse, turned to something else, something you despised, something that made you crave the breaking of their limbs and the sound of their cries, because I was once the angel with eyes on fire!

Skinned of pride and cast aside like a carcass left to fester, perceiving eyes feel like stabbing embers.

Being stripped down to self-abasing nakedness, using the last vestige of your dignity to declare, You will never be free of me. For what need is dignity to a crying Casanova?

We found it ironic when unbridled ambition displeased the inventor of lustcorrection; He invented desire, we let it consume us, and through us, birthed lust.

Our sour concealment, the only safeguard from admission of defeat. My arms curl like scorched paper, desperate to escape your heat.

Derision gave way to this guarded promise of war.

We crave their downfall, yet we will spend every day for the next eternity vying for their attention with spiteful insurrection.

Could you look us in the eyes and tell us we are alone?

Loss is just love; the sudden lack thereof, only eyes that have a heart can burn with such hate, only one who once held something dear knows the fall of that hot searing tear, and

Herein lies the ridiculous cognitive dissonance, in which I find my moral bind, of all his inherent evil, he has a heart that feels like mine.

on the outside OF the Circle

Last September, I found myself on the LIRR, approaching a pub I wasn’t old enough to enter without two thick, black Xs marking my hands. A friend and I were seeing one of those bands that varies between folk/indie/emo/ alternative-rock with each song. Packed like a sardine, ocean-tinted lights bore down on my grimacing face. “Did we really used to stand this close?” I wanted to ask my friend— but the music was loud and they’d been confused when I suggested we stand toward the back. So, despite the covid-conditioned voice mentally shaming me for it, we ended up in that sweet spot of crowd following the immediate front. This patch of bobbing heads and swaying palms was a liquid state— back and forth, up and down— until all of the sudden, it was as if someone had pulled the plug from a drain at its very center. The bodies before me began to swirl and derail, and I found myself standing in hesitation on the outer ring of a mosh pit.

The mosh pit is one of the more-negligible losses of the pandemic, but as crowds reform and precautions are thrown to the wind— they’re returning. Moshing began in the 70’s as hardcore punk popularized in rejection of hippie culture. Shows were often organized by the band themselves. This made progressive cities full of back corners and basements (like NYC), perfect. The crowded space and rage-filled music incited concert-goers to crash into one another— for reasons outsiders didn’t understand.

When done safely, the crushing of one set of bones into another parallels a head nod from across the room— it is a cathartic act of recognition and unity amongst strangers. But audiences outside of punk, metal, and now hip-hop crowds have never accredited moshing with having a reputation of “safety”. Saturday Night Live’s 1981 Halloween episode brought moshing from basements to mainstream television when punk band “Fear” performed. This exposure was cut short, however, as the crowd began moshing, screaming obscenities, and breaking equipment— the program cutting away to an Eddie Murphy sketch.

In the 90’s, many bands, such as “Fugazi” and “The Smashing Pumpkins”, were openly anti-mosh due to an increase of injuries and even deaths occurring at concerts. However, these dangers still didn’t stop pits from forming at their shows. Even today, with the added risk of contracting Covid in such a compact setting, people won’t be denied this thrill.

So why does the mosh pit persist? What do moshers feel in that moment of extended euphoria, bones crushing in pure bliss, and is that feeling worth the risks? As I watched a pit form before me that September night, I debated whether to scoot back from the anxiety-inducing madness— or closer. And then it hit me. No, really, somebody slammed into me. All thoughts flew from my head and, in that moment, I was both dizzy and acutely aware of my body. I looked up, pursuing the perpetrator, only to see a fleeting smile from whom it might have been, not a trace of violence or ill intent on their face. If anything, in the moments before happily disappearing back into the crowd, their smile seemed to signal “you’re welcome.”

By Paige Daniel Art by Ryan Nelsen IG: @ryanimate

Elodie Has NOTHING To Say

By Elodie HollantI hate being a writer sometimes. Because I know I’m going to have to be vulnerable. I hate that.

I don’t want anyone to get to know me or what I went through just to be entertained, just to critique. Shut up if my word choice is weak when I’m trying to talk about how I almost died when I was 18 because I decided to stop eating altogether.

But this is what I signed up for when I decided to become a writer. The whole point of studying writing is to nod thoughtfully when people tell you that there’s a better way of saying ‘I sometimes get so filled with grief that I want to throw myself from my dorm-room window, but I won’t because my little sister would be sad.”

I hate letting people know things about me, but my writing is centered around opening myself up, spilling my guts out. But I’d rather die than tell you anything about myself.

I’d stitch my organs together if I could.

I’m aware that if I keep this obsessive hold over my idea of privacy, I’ll end up alone. My mom tells me that I should give people a chance. But I don’t want to. I don’t want to give people the opportunity to hurt me. I guess that’s what I’m really afraid of. I have this warped belief that everyone’s out to get me. It’s silly, because I’m nothing special. I’m just like everybody else, but in my head, I’m the only one who has ever felt the way I feel.

Does this fit the theme? Is there enough RAGE here?

What’s the conclusion I’m coming to here, sitting at my desk? Is it that my fear of vulnerability will hold me back as a writer? Or is it that I should go to therapy?

I don’t know. But it doesn’t matter what I think, because once you read this, you’ll make up your mind about what you think this is about. Do you ever think of that? How your writing isn’t yours the second someone else reads it? I don’t mean that it’s no longer your idea or your beliefs, what I mean is that your intention gets lost if the reader doesn’t know what it is. If what you meant is convoluted, is it still what you wanted to say? Is this narrator still full of RAGE if the editor thinks she’s nervous?

I could’ve come up with a better idea for this essay. Something further away from me. A piece I could easily subtract myself from, so that the impending negative reviews will piss me off less. I could say this is experimental writing. I could say the shitty stream-of-consciousness voice was intentional, that this whole piece is ironic. I don’t think you’d believe me. But shut up if you don’t. Everything has an audience.

What kind of voice is this?

Is this RAGE? Nervousness?

Is this sad, a little pissed off?

Or is this just me?

You don’t know. I don’t know, either.

Art By Yi Shen Wei IG: @p.papple-artist by Anonymous Hong Konger

by Anonymous Hong Konger

the hurting world: designing beyond Diametric Relationships

Wordsand

art by Nina LuAh yes, New York City. A walk down the street has us brushing past walls of leaking garbage bags, an unearthly smell wafting up from the sewer grates and the guts of the last bird to perish in this concrete covered world. Every visual semblance of the seventies’ Earth Day and Loisaida gardens have been pasted over by Target and Nike signs; this is a city now designed for consumer manipulation, as opposed to wild community. With signs so big, we barely ever pay attention to the grass growing between the sidewalks. But it is certainly there – roots still run beneath our feet.

When urbanization occurs, the grit of bodies pushed against bodies is inevitable. Our eyes are dragged out of gutters, scanning each face through the lenses of stereotype, then not seeing anything at all. Yet when night falls, we get past the bouncer and push our bodies as close as possible to the next. Sure, city life is about the music - but it’s also about the desire. Unbridled, unbounded, deified desire. It’s the same desire we’re asked to target in the next ad mockup for class. “Convince me I need the product,” the teacher says. This is an environment swarmed with humans and graffitied with spit and urine. But it is ultimately design that reinforces a diametric relationship between urban spaces and our collective nostalgia of the “wild.”

That is to say, consumers are bombarded with products and messaging to buy and buy until they need to escape from the city’s visual noise after a while. Thus, the oversaturation of design made to sell creates a narrative of separation between urban-ness and

wilderness: ‘the city’ and ‘upstate.’ I mean, Prospect Park is such the only semblance of Brooklyn greenery untouched by Apple ads that it has changed surrounding property values and cultural enclaves. This need for ‘escape’ is a heavy nostalgia for a time when the city was more independent, radical and ecological.

So, it is only when we learn to see humans as more than a target audience – as individuals taking up a space equal to weeds in the ecological web – can we design for adaptation past destruction.

But perhaps we are in a place that will still try to train us to design for exponential production out of resource exploitation – reinforcing the “status quo.” This diametric that disregards our simply “being,” as creatures do. I mean, we despise Amazon, yet take their job offer. “Ugh,” we say. “It sucks, but that’s how it is.” We know “sustainable branding” is dishonest but ugh, at least we’re getting paid. We market ourselves as outstanding tools in the corporate belt– but “ugh, it’s a necessary evil.”

“Ugh, ugh, ugh.”

Design is supposed to be radical. Radicalism invites pushback and instability. It is now necessary for our survival not just to design for profit. Instead, we need to be connected, ecological people. You wield the power of visual influence. So, who are you designing for?

Rage Crossword puzzle

Created by Mage

Created by Mage

CLUES

Down

1. e.g A ______ spirit (as in: a ghost with ill intent)

2. A strong feeling of hostility

3. An intense form of anger

6. An intense emotional state of displeasure

7. 1999 film about an anonymous, violent club for young men based on the book of the same name. (2 words)

9. Retaliation for past wrong-doing or hardship

11. Achievement of progress or development

12. Expressing opposing views or feelings, often in a heated manner

Across:

4. Song title from gothic rock band The Cure’s selftitled album

5. To let go of anger or resentment toward someone for a past offense or mistake.

8. Descriptor found in the name of the destructive alterego to Marvel’s gamma radiation exposed scientist.

10. American rock band known for their song “Killing in the Name.” (4 words)

Dear Prattlers,

As the semester draws to a close, the dark days of winter wrap us in a wretched embrace. The cold outside amplifies the dreariness in the air. Seasonal depression moves in and unpacks its bags. As a foil to “Nostalgia,” we introduced “RAGE.” Consider it a bit of free therapy. In this issue, we invited our contributors to seethe, to boil over, to get even, and to let their heavy emotions flow freely. But above all, we wanted them to dismantle their rage and examine those pieces. We wanted to read about rage as a constructive and creative force.

But how does one write about a complex emotion such as rage? The truth is that anybody can rant about the horrible things another has done to them, but we didn’t want pieces only bitterly recounting scenarios. We challenged our contributors to go deeper, to find that productive anger. We wanted them to sit down with their rage. To name it. To tell us what it looked and felt like. To ask it what it wanted and to know when it was right and when it was wrong.

Art is a form often used by the overlooked and threatened to fight against oppressing forces. It is speaking without words or alongside them–– it is resistance. My art is a weapon, and yours is too. Let’s use it precisely.

Willfully Yours,

Ingrid Jones Prattler Staff Ingrid Jones Maddie Langan Editor-in-Chief Managing Editor Amber Duan Yotian Chu Co-Creative Director Co-Creative Director Naomi Desai Christina Park Production Manager Social Media ManagerISSUE 2 | FALL 2O22