8 minute read

Embrace Being in the Moment Amongst The Wonders of Japan

Here & Now

By Linda Barnard

The young Zen Buddhist monk had a shaved head and a decent swing. The metre-long stick in his hand hit the flat of my shoulder with a firm whack.

No surprise here. I’d asked for it, signalling with a deep bow that my mind was wandering during the 30-minute zazen (seated) meditation he was leading at Daihonzan Eiheiji, a Soto Zen temple in the forested mountains about 500 km northwest of Tokyo.

For about $10 Canadian, visitors can work their mindfulness muscles with a meditation at Eiheiji, meaning “temple of eternal peace.” Two-night stays with vegetarian meals, lots of time for silent reflection and humbling housekeeping chores are about $100.

There are 70 wooden buildings of various sizes in the monastery complex, which was founded in the 13th century. A heavy snowfall made the surroundings even more picturesque, silent — and cold. The monks go barefoot in the unheated monastery.

The half-hour spent propped up on a round meditation pillow, concentrating on my breathing and fidgeting to get comfortable, felt much longer. The monk sat motionless in the lotus position; his black matte silk robes arranged around him.

Like many people, I’m not very good at stilling my mind, living in the moment or keeping still, never mind getting into the lotus position. Could time in Japan help me learn Ichi-go itchi-e, the concept of being here, now?

Guide Yuko Ehara explained it to me this way over breakfast: our conversation, this sunny morning, the food, none of it can ever be repeated in exactly the same way. Ichi-go itchi-e means to focus on things as they happen and to be grateful for this unique moment.

I vowed to embrace it. From easing into the hot and healing waters of communal geothermal mineral baths, savouring each bite of luscious wagyu beef or fatty tuna, or feeling my legs burn as I climbed stone steps on a 1,000-year-old pilgrimage route, I’d tune into each experience as it unfolded on my six-day trip to Japan.

I arrived in Tokyo. Since we were heading to other regions on the main island of Honshu, I spent just one night. From my room at the Shibuya Excel Hotel Tokyu, I watched pedestrians 20 floors below take the famous multi-directional Shibuya Scramble crosswalk. I also went to the top of the neighbouring Shibuya Square building, where Shibuya Sky has 360-degree views from 230 metres up. Time-booked tickets are $22 Canadian.

We left frenetic, fascinating Tokyo behind on the five-hour train ride west into the foothills of the Japan Alps for a stay at Rurikoh, a ryokan in the Kaga Onsen region. The area is famous for its hot underground spring-fed baths, called onsens.

Ryokan are traditional Japanese inns. Rooms have woven tatami mat floors. Guests can sleep on the floor on plush futons. I opted for a bed for my stay. Two nights later, I chose a futon at the 575room Hotel Urashima Resort & Spa in the town of Nachi Katsuura Onsen. It was a surprisingly restful sleep. A peaceful soak in the hotel’s Pacific Ocean-view cave onsens (mineral-rich waters said to help everything from arthritis to skin conditions) likely contributed.

Men and women bathe separately and naked. It may seem strange to be unclothed around strangers at first, but the feeling doesn’t last long. Pictogram signs explain everything you need to know, like washing your body before your soak.

I stepped into the shallow 40 C water of a rock-lined outdoor pool at Rurikoh’s onsen (there’s also a larger bath indoors) and watched the snow falling on carefully pruned trees in the small garden.

Afterwards, I was so relaxed, that it was an effort to dress for the multicourse kaiseki dinner in a private dining room. These dinners are like a chef’s multicourse tasting meal and are usually part of a ryokan stay. The menu combines imaginative presentation and the best of local, seasonal foods. The kaiseki at Rurikoh was a banquet of creative courses, including house-made tofu topped with shaved radish designed to mimic a mound of snow, local seabream sashimi and newly in-season Queen crab rice. The meal was paired with sake brewed nearby, served cold from small glass flasks.

I used my vow to stay in the moment as an excuse to take breaks as we climbed a short but challenging section of the Kumano Kodo ancient pilgrimage route to a Shinto shrine in the Kii Mountain Range. The 267 stone steps seem to be an organic part of the moss-covered forest and the vertical route is lined with massive old-growth cedars, some 800 years old. The tranquil UNESCO World Heritage Site was a place to consider how many others had climbed this route, wearing the stone stairs smooth in spots. Now I was in this moment, walking their path, too.

Near the top, we bowed and walked under a vermillion torii gate, a traditional Shinto shrine entrance. The Kumano Nachi Taisha Grand Shrine is a group of brilliant red-orange buildings of varying sizes, each of which houses a spirit, or kami. Beyond is the pagoda-style Seiganto-ji Buddhist temple, with 133-metre-tall Nachi, the country’s tallest waterfall in the background.

In historic Kyoto, I struggled to keep my ichi-go itchi-e promise as I thought about the evening ahead and a geiko (the name for geisha in Kyoto) and apprentice maiko performance in a private room in a local restaurant over a kaiseki meal.

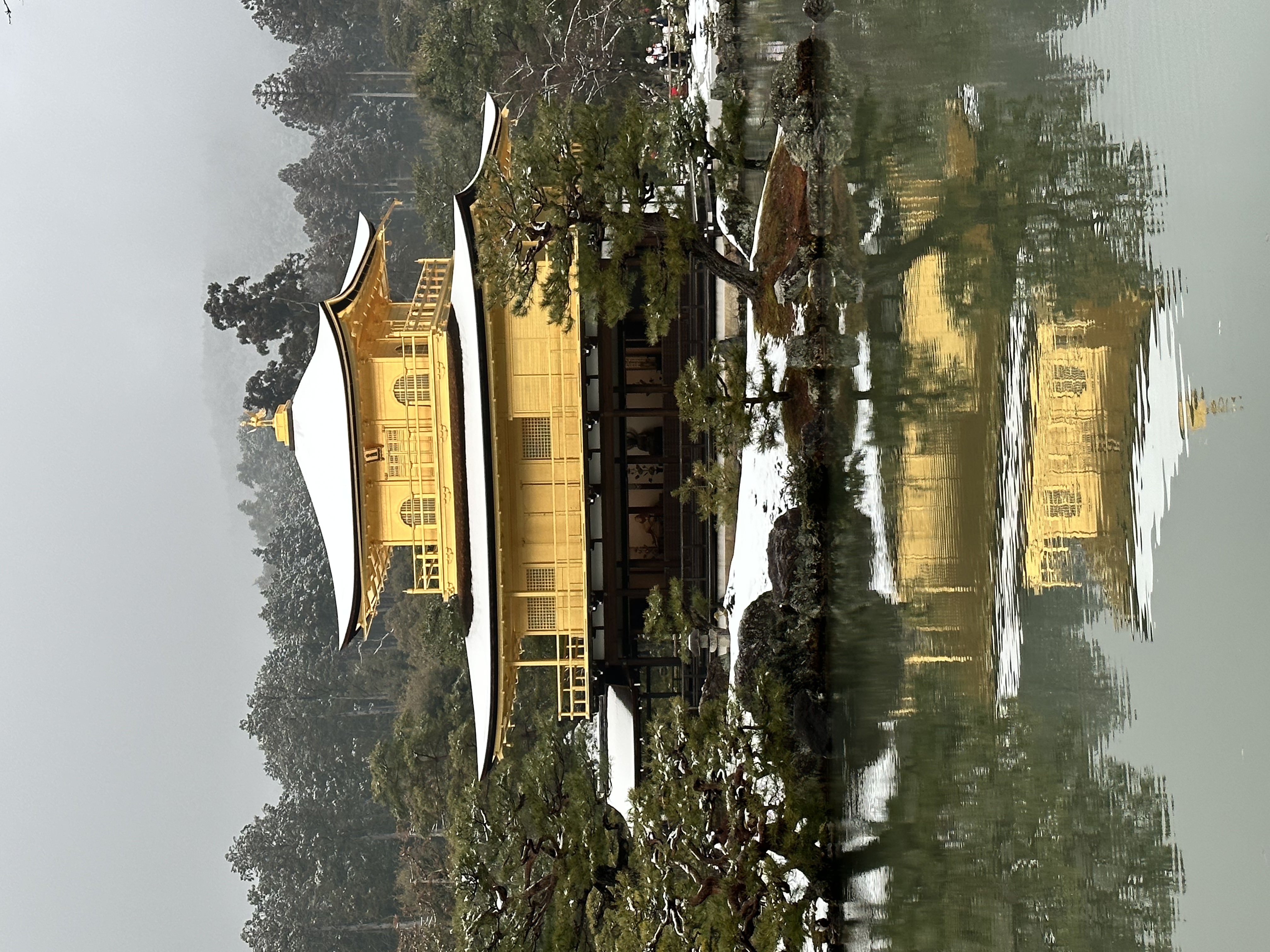

We started our day in northern Kyoto, where the first glimpse of Kinakuji (Golden Pavilion) made the here and now the best place to be. The top two floors are entirely covered in gold leaf. A still, tree-lined pond at the foot of the onetime home of a retired shogun created a stunning reflection. The shogun’s villa became a Zen temple following his death in the 15th century. It has been rebuilt several times since.

Recognized by the Japanese government as an “intangible cultural asset,” the geiko and maiko performance was everything I’d hoped for. It’s not easy to arrange to see these artists perform, considered to be agents of living culture in Japan. A personal introduction to the woman who runs the geiko house in one of the five “flower town” districts in Kyoto is required first. And it’s not cheap. Our private performance costs about $2,000 Canadian for 90 minutes.

Ontario-based Japan tour leader Sam Hirota said one option is to book a local tour. Or hire a travel agency to organize your Japan trip and request a geiko and maiko dinner when you book. If you’ll be in Kyoto in April, get tickets to the annual Miyako-Odori, where geiko and maiko do a month of showcase performances.

Geiko Tomitae and Maiko Hidechiyo greeted us at the door of the restaurant with low bows. I gasped when I saw them in their elegant kimonos, white makeup and traditional hairstyles. They smiled and bowed again.

Tomitae sang and played a shamisen, a three-stringed, banjo-like instrument. Hidechiyo danced with delicate exactness, moving her sleeves or holding her fan just so. Each dance began with her turned away from us, making a deep back bend. Their movements and gestures were graceful and precise, down to the careful way Tomitae folded her hands, fingers pointing down in her lap, as we talked. I couldn’t help staring.

Afterwards, they sat with us, pouring sake and tea, laughing at our jokes and answering questions through an interpreter. Tomitae, who became a maiko about 10 years ago at age 16, wanted to dispel Hollywood myths like the one that geikos are “sold” to mother houses as girls to train. Not true.

They invited us to play Konpira fune fune, a Japanese drinking game that looks easy but isn’t. I sat at a low table opposite Hidechiyo. We took turns tapping a round wooden block between us as Tomitae played a simple tune that kept speeding up until one of us made a mistake. Hidechiyo always won.

The evening with Tomitae and Hidechiyo was the definition of ichi-go itchi-e: one time to be treasured in Japan and never repeated.

Linda Barnard was a guest of the Japan National Tourism Organization, which did not review or approve this article.