HOME PLACE

BLUM PLACE

HIRSCHFIELD PLACE

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT

JUNE 2022

HIRSCHFIELD PLACE

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT

JUNE 2022

Preservation Texas

Bassett Farms Conservancy Kosse, Texas www.bassettfarms.org

MIG, Inc. Portland, Oregon www.migcom.com

Publication Credits: Information in this report may be copied and used with the condition that credit is given to authors and other contributors. The primary authors meet the criteria set by The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties for qualified professionals, as outlined in Appendix A of the Guide to Cultural Landscape Reports: Contents, Process and Techniques. Appropriate citations and bibliographic credits should be made for each use. Photographs and graphics may not be reproduced without the permission of the sources noted in the captions.

Acknowledgements: This project was generously supported through grants from The Still Water Foundation and the Texas Historical Commission.

The authors would like to thank Julie McGilvray, a Historical Landscape Architect with the National Park Service, who was instrumental in getting this project initiated, and the Preservation Texas Bassett Farms Conservancy Committee members (noted below) who provided valuable guidance.

In addition, the authors are grateful for input received during an October 2021 workshop from Tony Crosby, former chair of the Bassett Farms Committee and former NPS preservation architect; Dixie Hoover, Bassett Farms Committee; Kate Johnson, Chair, Bassett Farms Committee; Laura Lehmons, Kosse Heritage Society; Sarah McReynolds, Site Manager, Old Fort Parker; Karen Partin, President, Kosse Heritage Society; Tim Partin, Rancher, Bassett Farms ranching tenant; Alysha Richardson, Site Manager, Sam Bell Maxey House; Andrea Roberts, Professor, Texas A&M and founder of Texas Freedom Colony project; Ron Siebler, Preservation Texas board member; Mary Strickland, Bassett Farms Committee; Evan Thompson, Preservation Texas Executive Director; Brooks Valls, Mayor of Kosse, Texas; and Linda Valls, Kosse resident.

Cover: Looking southeast at the recently restored Bassett House at Home Place (Preservation Texas 2022)

Metal Pole Barn with the Wood Pole Barn in the background and a gate, fence, and remnant access road in the foreground at Home Place (MIG 2021)

Metal Pole Barn with the Wood Pole Barn in the background and a gate, fence, and remnant access road in the foreground at Home Place (MIG 2021)

SETTING AND CONTEXT

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT PURPOSE AND METHODS

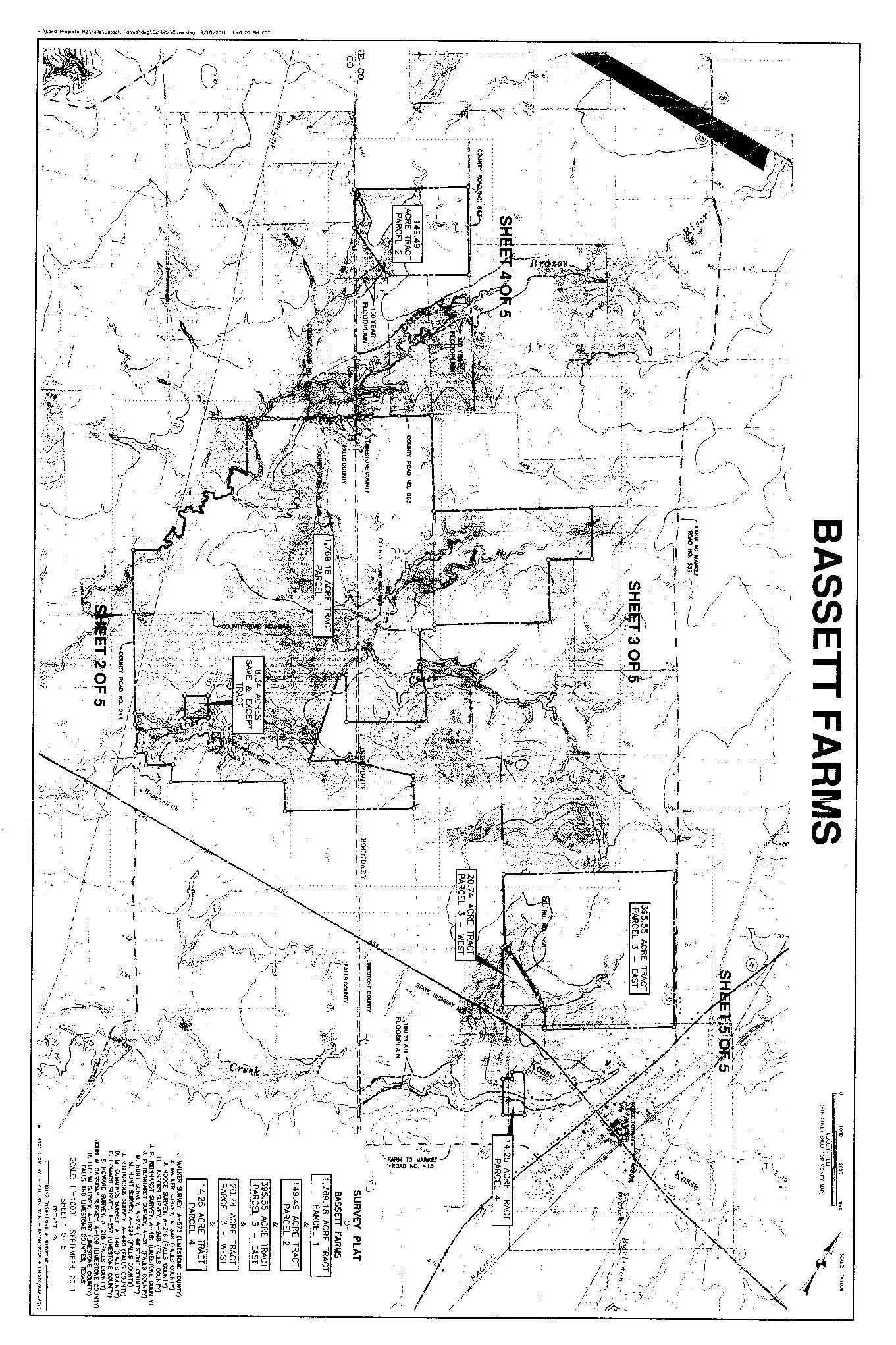

Bassett Farms Conservancy, (“Bassett Farms”) includes 2,349 acres in Limestone and Falls Counties, Texas, divided into four discontiguous parcels of 1,768, 416, 149.5, and 13.6 acres. Bassett Farms is located three miles northwest of Kosse, a small town (population 450) that was laid out in 1870 when it became the temporary terminus of the newly constructed Houston and Texas Central Railroad. The focus of this Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) is the landscape associated with the Home Place, Blum Place, and Hirshfeld Farm, and their associated pastures that are located within Parcel 1. Other tracts and parcels that are owned by the Bassett Farms Conservancy will be addressed in future planning reports.

Bassett Farms was assembled by the Bassett family over a forty-five-year period between 1871 and 1915 by both Henry Bassett (18171888), who made the initial purchase of the 160-acre Home Place in 1871, and his widow, Hattie Ford (Pope) Bassett (1851-1936), who purchased the last original tract in 1915 from the heirs of Martha Green, widow of AfricanAmerican Union veteran Robert Green. In 2012, following the death of Henry Bassett’s last surviving granddaughter in 2010, the property was bequeathed to Preservation Texas for longterm preservation, conservation, and educational purposes.

As an intact cultural landscape in this region of Texas, Bassett Farms presents the opportunity to share its history with visitors from near and far, so that they may understand and appreciate the successes, trials, and tribulations of the Bassett family over three generations, from 1871, through the 1970s, as well as that of

the Bassett family’s tenant farmers, and the residents of the Hopewell Freedom Colony. This landscape is known as Bassett Farms, but it is more complex than the collection of buildings that remain on site. Like all rural agricultural cultural landscapes, Bassett Farms was dynamic throughout its history. As needs arose, and economies evolved, the house at Home Place was built and modified, as were the garage, barn, and outbuildings. Some acreage was reserved for cattle grazing, while other areas were planted, primarily in cotton. As a rural agricultural landscape, it was especially vulnerable to the ebb and flow of local, regional, and national economic trends, as well as the predictability, and unpredictability, of seasonal weather patterns, drought, and temperature fluctuations.

During the same period, Hopewell Freedom Colony was the home for emancipated slaves after the Civil War, many of whom worked at Bassett Farm. Hopewell, like other Freedom Colonies across the south and areas of the mid-west, also evolved over time, as there were changing needs for families just freed from the yoke of slavery yet burdened with second class citizenship. Notably, children from Hopewell and the Bassett Home Place often played together, while their parents worked side by side in the fields or fulfilling the domestic needs in the Bassett House. This was a demanding life and recognizing that fact helps us all to comprehend what it took to secure, settle, and maintain this landscape, regardless of one’s station in life. Today, Bassett Farm and Hopewell Freedom Colony are both under the ownership – and protection – of Preservation Texas, the statewide non-profit organization dedicated to preserving these buildings and landscapes, and telling their stories together, as they were intertwined communities.

Bassett Farms is now prepared for a major cultural landscape preservation and rehabilitation planning effort. Excellent work has been underway for some time on building documentation, analysis and restoration, and new information about the structures is regularly revealed through investigation, documentation, and subsequent repairs. The Bassett Farms Cultural Landscape Report (CLR) provides the guidance and direction for the next phase of this major preservation effort.

The Bassett Farms Cultural Landscape Report provides treatment recommendations for the cultural landscape resources to address changes in the landscape since the period of significance, improve the overall condition of the cultural landscape, and recommend treatments in coordination with the goals of the Conservancy and Preservation Texas. The treatment recommendations are designed to support Conservancy objectives, provide a treatment framework to assure the long-term stewardship of the cultural landscape, and minimize the loss of critical character defining landscape features by providing sound, systematic management guidance consistent with Preservation Texas objectives.

The Bassett Farms Cultural Landscape Report:

• Broadens the understanding of extant landscape characteristics and features and their relationship to the period of significance (1871-1970s);

• Ensures that planning and design efforts reflect state and national guidelines, including The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties with Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes; and

• Develops a series of plans and graphic images depicting the landscape as it developed over time, with a focus on the historic period, that will serve programmatic, planning and design efforts and enhance the Conservancy’s interpretation and educational aspirations and materials into the future.

The CLR is organized in three sections.

• Section One of the Cultural Landscape Report includes a comprehensive site history.

• Section Two includes documentation of existing conditions, and a summary of analysis and evaluation of cultural landscape features.

• Section Three provides treatment recommendations for preservation and rehabilitation of significant resources in coordination with Preservation Texas objectives, potential operations, landscape maintenance needs, and a range of site access opportunities. It also considers potential uses for public access to Bassett Farms, including, but not limited to, harvest fairs, summer educational programs, concerts, and other events.

The CLR cultural landscape documentation, analysis and treatment recommendations are based on well-established standards of the National Park Service. These standards include thirteen cultural landscape characteristics and their associated features, and the ways in which they interact, with the intent of gaining and providing a comprehensive understanding of the cultural landscape as it is today, from its largest characteristic (overall spatial organization) to its most intimate features (small scale features.)

The CLR also engages established knowledge about natural systems, such as topography, soils,

native and invasive plant species, wildlife, and hydrological systems. Including information about the natural systems and features analysis is essential to gaining a comprehensive understanding of how and why the cultural landscape developed as it did, as is evident in the historical description, below.

Of the thirteen cultural landscape characteristics established by the NPS, nine are included in the CLR to deepen our understanding of this place. They are:

• natural systems: processes and features in nature influencing historical development or use

• spatial organization: the historical, threedimensional arrangements of physical form

• land use: historical activities that influenced development or modification

• buildings and structures: historical constructed forms and edifices

• views and vistas: historical range of vision, both broad and discrete

• vegetation: patterns of human-influence plants, both native and introduced.

• circulation: historical systems for human movement

• constructed water features: historical constructed form for water retention and conveyance

• small scale features: discrete historical elements that provide detail and diversity

Portion of circa 1916 photo of the Bassett House and ornamental vegetation that flanked its eastern side (Preservation Texas archives)

Portion of circa 1916 photo of the Bassett House and ornamental vegetation that flanked its eastern side (Preservation Texas archives)

OVERVIEW

HOME PLACE

BLUM PLACE

HIRSCHFIELD PLACE

This Bassett Farms Site History has been made possible by a grant from The Still Water Foundation. Preservation Texas is grateful for the Foundation's continuing support for historic preservation in Texas.

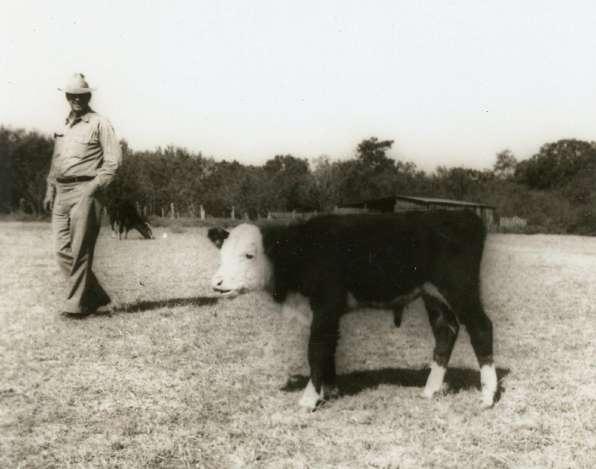

As Preservation Texas undertook detailed planning for Bassett Farms in 2012, which began with a study of the historic Bassett House and its outbuildings, it was still searching for an unknown number of underfed Hereford cattle in the mesquite thickets along Sulphur Creek. Consultants with expertise in land conservation and ranch management were called in for guidance as the organization began to adjust to its new role as the owner of a large, historic Central Texas ranch. Early on, the board recognized the enormous educational and environmental value of the land that had made it possible for the Bassetts to develop and sustain a 2,400-acre property for three generations. The need to balance historic and natural values were underscored by guiding principles for stewardship proposed in the Fall of 2012:

● All activities and practices are designed to represent or model an integrated approach to land and water, historical, cultural, and archaeological stewardship;

● Agriculture, conservation, preservation, and restoration are in balance. Each is defined in its own system and then integrated with the others to bring about a holistic outcome;

● All practices will have a focus of integrating the community and educating the generations;

● Anticipate and plan for emerging issues; and

● Those who came before are honored through the standards upheld today.

While Preservation Texas worked diligently to become familiar with the property's historic resources, archives, and collections, these guiding principles were kept in mind as it took a conservative "do no harm" approach to the landscape. Input from the Dixon Water Foundation about the use of cattle to maintain and sustain grasses and forbs through intensive rotational grazing and the availability of resources from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department's private lands program to restore native prairies provided the organization with sustainable models for land management. Yet as important as these natural resource-focused programs are, they seemed disconnected from Preservation Texas's traditional emphasis on the preservation of historic buildings by credentialed architects.

It was through a collaboration that began in 2017 with the National Park Service's Julie McGilvray to raise awareness of the remarkable, endangered mid-century modern house, Ship on the Desert, at Guadalupe Mountains National Park, that Preservation Texas was introduced to the idea of cultural landscapes as a management tool for large-scale land areas. The application of a cultural landscape framework to Bassett Farms

through which to integrate historic and natural resource management seemed to offer the preservation-oriented approach Preservation Texas had been looking for. The board of directors quickly embraced the language of cultural landscapes that could integrate and balance the sometimes competing ideas of historic preservation, natural resource conservation, public interpretation, agricultural management, and sustainable development.

With this new focus on understanding Bassett Farms as a cultural landscape, funding was secured from the Texas Historical Commission and the Still Water Foundation to produce this site history in support of a cultural landscape report to guide the organization in its stewardship of this complex site.

Evan R. Thompson, Executive Director San Marcos,Texas

August 2021

1.1 Bassett family and friends pose on a wooden gate along the Kosse-Marlin Road at Bassett Farms, circa 1920.

1.2 An aerial satellite map of the four discontiguous parcels of nearly 2,400 acres in two counties that comprise Bassett Farms, 2013.

1.3 A group of children gathered in front of the Bassett House, c. 1920.

1.4 The c. 1950 wooden pole barn on the Bassett Home Place in July 1992.

1.5 Map of the post oak savannah ecoregion.

1.6 Map of the Sulphur Creek watershed.

1.7 Map of wetlands and surface water at Bassett Farms.

1.8 Rural Falls County, c. 1930.

1.9 Reconstruction of a typical beehive-shaped hut at Caddo Mounds State Historic Site.

1.10 "Mapa Original de Texas por El Ciduadano Estevan F. Austin," 1829.

1.11 Map of the Camino Real.

1.12 Map of the sparsely settled northeastern New Spain in the late 18th century.

1.13 Map of Texas in 1835.

1.14 "Map of Texas with Parts of Adjoining States," 1835.

1.15 Sarah Pillow League, surveyed in 1835, with the area that later became Bassett Farms to the north and east.

1.16 Fort Parker, reconstructed in 1936 and again in the 1960s, on the site of the original Fort.

1.17 Map of Robertson's Colony made at Franklin, Texas in June and July 1839.

1.18 Map of Texas by William Bollaert, c. 1840.

1.19 Map of Texas by Arrowsmith, 1841.

1.20 "Corrected Plot of the Western Part of Limestone County, Texas," 1847.

1.21 "Pressler's Map of the State of Texas," 1857.

1.22 Asher & Adams Map of Texas, 1871.

1.23 A typical newspaper advertisement for the Houston and Central Railroad appeared in Galveston on November 26, 1870.

1.24 Logan's Railway Directory, 1873.

1.25 An illustration from Washburn & Moen Manufacturing Company's 1876 promotional booklet, Barb Fence: Its Utility, Efficiency and Economy.

1.26 Map of cotton production by county in Texas in 1909.

1.27 The largest of the Home Place stock tanks was constructed before 1939.

Bassett Farms Conservancy (“Bassett Farms”) consists of 2,349 acres in Limestone and Falls Counties, Texas.1 The property is divided into four discontiguous parcels of 1,768, 416, 149.5, and 13.6 acres. Bassett Farms was assembled by the Bassett family over a forty-five year period between 1871 and 1915 by Henry Bassett (18171888), who made the initial purchase of the 160-acre Home Place in 1871, and his widow Hattie Ford (Pope) Bassett (1851-1936) who purchased the final tract in 1915 from the heirs of Martha Green, widow of AfricanAmerican Union veteran Robert Green. In 2012, following the death of Henry Bassett's last surviving granddaughter in 2010, the property was bequeathed to Preservation Texas for long-term preservation, conservation, and educational purposes.

Bassett Farms is located three miles northwest of Kosse, a small town (population 450) that was laid out in 1870 and became the temporary terminus of the under-construction Houston and Texas Central Railroad. This new

1 Bassett Farms is bisected by the Falls and Limestone County line. From 1837 to 1846, the entire property was located in Robertson County. In 1846, the creation of Limestone County included all of Bassett Farms. Falls County was created in 1850, with the county line being drawn through the middle of Bassett Farms. The county boundaries have not changed since that time.

railroad would connect Houston to Dallas, opening up a large area of inland Texas to agricultural and commercial development by providing direct access for crops and livestock to Texas's port cities on the Gulf of Mexico. Connecticut-born Henry Bassett was one of thousands of new settlers populating the Texas frontier during Reconstruction, but unlike most, came with the capital to invest in real estate and otherwise "speculate and make the most money."2 The land that became Bassett Farms would be used to grow cotton, graze cattle, and explore for oil and gas. The wealth the family gained through its stewardship enabled the third (and last) generation of Bassetts to attend private Dallas schools in the 1920s, become debutantes in the 1930s, and marry doctors. At the heart of the family's identity, however, was Bassett Farms and the memories it held of three generations of Bassetts living in the Bassett House in the early 1900s.

In the 1960s, recognizing that the family line would come to an end with the childless third generation, the Bassetts began discussing the long-term preservation of the property as an ideal place to tell the story of early Texas farm and ranch life. Investments were made to "improve" the house, and over the next four decades, the Dallas granddaughters would steward the property from afar, seeking to develop its resources to reinvest in the maintenance and operation of the farm. However, over time, as the fields became overgrazed, they became increasingly thick with mesquite, honey locusts, and other species that transformed the landscape into something of a wilderness. And as the Bassetts aged, so too did the farm's buildings, and where once there was a thriving community populated with dozens of tenant farmers and families dependent on the Bassetts and their land for their meager livelihood, the Bassett House stood empty.

Mrs. Willie Ford (Bassett) Sparkman, the last of the Bassetts, nurtured ideas of a house museum paradoxically filled with personal collections of china and silver accumulated during her long life in Dallas. Her husband, Dr. Robert Sparkman, a surgeon, bibliophile, and friend of many of the leading Texas cultural figures of the mid20th century, cast doubt on any such enterprise. He summarized the challenges of Bassett Farms in a short list:3

● Unfavorable location to attract visitors

● Security

● Unreliable electrical supply

● Unimproved roads

● Lack of appeal for responsible employees - boredom

● Theft and vandalism

● Home for caretaker

● Administration - trustees? ownership?

The Sparkmans debated their options but Mrs. Sparkman's vision of preserving Bassett Farms to memorialize a way of life that had been otherwise lost prevailed in her bequest of the property to Preservation Texas.

Fortunately, the family's foresight to preserve family papers and photographs makes it possible to begin to reconstruct the complex story of Bassett Farms. While the Bassett family and their triumphs, trials, and tragedies anchor this story, the forgotten history of the Hopewell Freedom Colony has re-emerged through a study of the history of the Bassett property. The Bassett story is now inextricably linked to the formerly enslaved men and women and their families who worked as neighbors, tenants, and employees of the Bassetts for a century. As Mrs. Sparkman remembered decades later:

At the turn of the century, the Bassetts had many farmhands, and in fact, housed as many as forty families on the property. Annual celebrations such as Juneteenth were great festivities with barbecues, baseball games, and preaching. At Christmas, the family gave gifts to everyone housed on the farm, and decorated the main house with trees in every room. Birthdays at the Bassett home were special occasions with all the children in town invited for games, cake, and ice cream … one child visiting relatives in town was invited to the party. She had no money for a gift, but brought a box with fresh, juicy plums that were enjoyed by all.4

The history of Bassett Farms reveals at its core that life at Bassett Farms was a life lived outdoors. There are no family photographs taken indoors. Rather, the evidence reveals that nearly 150 years of work, recreation, and memory were and remain outdoors and inseparable from the land. Preservation Texas's vision for the property has evolved from Mrs. Sparkman's original idea of a house museum to take a wider view of the site's layers of

diversity, complexity, and change. This written narrative provides an important documentary foundation for understanding Bassett Farms and the unwritten legacy of its people that can be traced in the cultural landscape they left behind.

Bassett Farms is located at the western edge of the post oak savannah ecoregion where it meets the rich soils of the blackland prairie.5 The post oak savannah ecoregion features irregular plains that were originally covered in part by denser vegetation “in contrast to the more open prairie-type regions to the north, south, and west, and the pine forests to the east.”6 As at Bassett Farms, the modern land cover in this ecoregion “is a mix of post oak woods, improved pasture, and rangeland, with some invasive mesquite… A thick understory of yaupon and eastern red cedar occurs in some parts…”7 Forested areas include blackjack oak and black hickory with an understory that includes American beautyberry, all of which can be found at Bassett Farms.

Bassett Farms lies a few miles east of the Blue Ridge region of eastern Falls County. This area was settled in the 1840s primarily by families from Tennessee. The Blue Ridge is an elevation that rises 75 to 100 feet above Big Creek to its west and then descends gently eastward toward the Little Brazos River. Bassett Farms is located in the watershed of the Little Brazos and the property is more-or-less bisected by Sulphur Creek, which flows from northeast to southwest across the property before emptying into the Little Brazos. The Little Brazos forms a portion of the western boundary of the farm. Early deeds refer to most of the parcels that comprise Bassett Farms as being on the "headwaters of the Little Brazos," a seasonal stream that rises in southwestern Limestone County,

5 Historically, the post oak savannah ecoregion consisted of native bunch grasses, forbs, and scattered groupings of trees, principally post oaks, with forested riparian areas along creeks and rivers. Natural and man-induced wildfire coupled with bison grazing were essential elements in maintaining this ecosystem.

6 Ecoregions of Texas, 2007, p. 66-68. See https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth640838

7 Ecoregions of Texas, 2007, p. 66-68. See https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth640838

flowing parallel to the Brazos River through Falls and Robertson counties until it reaches the Brazos in Brazos County.

Riparian areas along the Little Brazos and Sulphur Creek and its tributaries have long been recognized for their timber and game resources. However, the Little Brazos and Sulphur Creek are typical intermittent Central Texas streams that depend on the area's average 38 inches of annual rainfall for their flow.8 Sometimes this rainfall comes in dramatic and unexpected torrents. While loss of life and structures through catastrophic flood events have not been recorded at Bassett Farms, dramatic weather events have been documented in the Kosse area as having an impact on its people, livestock, and crops impacts that are felt in the region today. The impact to Bassett Farms is on streambank erosion and the washing out of stream crossings.

As early as 1840, the Little Brazos was described as a "small, sluggish stream"9 and in 1860 it was "dry as a bone, except the inexhaustible holes."10 Extreme spring rainfall in May 1866 flooded the river: "the Little Brazos was a mile and a half wide in some places, and most of the streams had swollen till they were difficult to cross, and in some places, were impassable."11 It was because of torrential rains during a 48-hour period in April 1885 that the

"Little Brazos … together with innumerable smaller streams … have all risen rapidly and are overflowing."12 One of the worst floods in the Kosse area occurred in early July 1899:

Never in the history of this county has as much rain fallen as it has for the past week. It rained for seventy-two hours, with but few intermissions of ten minutes each. The crops on the lowlands and bottoms are from three to ten feet underwater, and have remained so since Wednesday last. They are entirely ruined. All the bridges throughout the county are gone. The roads are impassable. Several families had to be rescued from their homes to prevent their drowning. Numbers of horses, cattle, and hogs were drowned. No trains since last Wednesday. Railroad bridges wrecked and roadbed washed up. No telegraph communication. Fully three feet of water has fallen.13

While sudden, intense rainfall could be damaging to crops and infrastructure, heavy rainfall was generally welcomed when it tempered drought and provided needed water for crops and cattle. In April 1904, a "heavy rain fell throughout this [Kosse] section last night. All water courses, stock tanks, and cisterns are full. It is very beneficial to all growing crops…"14 Similarly, heavy rainfall in January 1939 was welcomed in Kosse because it "provided sufficient stock water, also preventing small grain from drying."15

Less frequent, but sometimes more destructive, were the effects of hurricanes and tornadoes, particularly in the spring. On May 2, 1871, what was termed a 'hurricane' "passed through a portion of the country near the northern terminus of the Central Railroad [Kosse]... Farm houses were blown down, and several frail dwellings and also the shed which served for a railroad depot in Kosse, were prostrated."16 On May 11, 1930, "a terrific wind and rain storm of cyclonic proportions, struck here [Kosse] about 8:00 [p.m.]... coming from the southwest… Barns, garages, outhouses, brick flues, were reported blown down…"17 On May 19, 1955, a tornado touched down and damaged the farm of M. A. Gunter, three miles northwest of Kosse, with a funnel cloud that was likely visible from Bassett Farms.18

Conversely, long periods of drought could have devastating impacts. As early as 1831, settlers recorded a severe drought in the Brazos Valley of Central Texas.19 In 1871, despite the May "hurricane," as the hot summer dragged on the Kosse area was "suffering for rain. In all Central Texas the cry is for water. At Bryan, Calvert, Bremond, Kosse, Groesbeck, Fairfield, and Corsicana, cisterns are a played out institution. Luckily for us, our springs hold good."20 Invariably, droughts were broken with torrential rains, as was the case on August 18, 1933 when a two

12 "Weather," Times-Picayune (New Orleans), April 24, 1885, page 8.

13 "Kosse," Bryan Eagle, July 6, 1899, page 11.

14 "Kosse, Limestone County, Texas," Houston Post, April 23, 1904, page 7.

15 "Conditions of Farms at Kosse Improve," Mexia Weekly Herald, January 13, 1939, page 5.

16 "Storm - Destruction of Property," Houston Daily Union, May 4, 1871.

17 Mexia Weekly Herald, May 16, 1930, page 7.

18 Waco Tribune, May 20, 1955, page 1.

19 Baker. A History of Robertson County, Texas, page 52.

20 Austin-American Statesman, August 5, 1871, page 1.

month drought in Kosse was broken "with a rainfall of 3.63 inches, accompanied with torrents of rain and damaging winds in some sections."21

Natural springs were much more abundant in the past and a critical source of water. Two historical springs are documented at Bassett Farms: Henry Bassett's spring, almost certainly at the site of his brick well on the Bassett Home Place, and the "Sulphur Spring" that was located on a 10-acre tract of the Hirshfield Farm acquired by Jay Bassett in 1897 and later transferred to his mother and brother in 1903. Henry Bassett referred to his farm as "Sulphur Spring Plantation," sometimes shortened to just "Sulphur Spring." Associated wetland areas adjacent to springs, seeps, stock tanks, and creeks are present as well. They perform important functions for "nutrient cycling, flood flow alteration, sediment stabilization, and providing plant and animal habitat." The value of these wetlands were not appreciated in the past when such areas were seen instead as obstacles to productive farming and grazing uses.

The area around Kosse is generally noted for its "temperate and healthful climate characterized by long summers … tempered, however, by southern breezes which blow most of the time. Winters are "short with periodic cold waves lasting a few days… in some winters severe sudden north winds called 'northers' are accompanied by freezing weather during January and February."22 Settlers long remembered a particularly severe winter in 1841-42, when

the Brazos River's flooded bottomlands froze.23 Otherwise, a typical year would see the last frost on March 9th, with the first frost on November 20th, for a frost-free season of 256 days.24

The corresponding architectural responses to climate are clearly expressed at Bassett Farms, particularly at the Bassett Home Place. The Bassett House is built on a slightly elevated position near, but not too near, the Bassett Branch of Sulphur Creek that supplied the family with water. A one-story porch, later replaced by a screened, two-story porch, provided summer shade and a place to sleep. Oriented to the south, the house was positioned to capture prevailing breezes, and large trees grew up on its west side to help keep the brick house cool. These basic principles of location, form, and orientation being driven by topography and climate were typical of rural farmsteads in the region, including the tenant houses at Bassett Farms.

While structures can offer shelter and protection for people, livestock, and material goods, they afford no respite for crops in the field. Of particular note was the grasshopper invasion of 1877. In September, "the sky was again darkened for two or three days," said R. A. McAllister, who lived just north of the Blue Ridge community of Stranger in the community of Odds. "They were in great droves and destroyed the grain and damaged the bark of the trees, they left their eggs and the next spring they hatched out and the gardens were ruined from them. When they grew wings, they left."25

The long history of human settlement in Central Texas has been documented at the Gault Site, eighty miles southwest of Bassett Farms, dating back 13,000 years.26 Closer to Bassett Farms, recent archaeological reports from Limestone County note that few excavations have been conducted in the region documenting Pre-Late Archaic people (before 2000 B.C.). A regional study of private collections and excavated sites in 2011 documented Clovis, Folsom, and Midland artifacts in Limestone County, generally found in low areas in the floodplains of the major streams. During the Late Archaic and Woodland period (2000 B.C. to 800 A.D.), excavations have revealed base camps in riverine settings with subsistence resource processing and extraction sites in the uplands. Settlement patterns in the region changed during the Late Prehistoric period (800 A.D. to 1650 A.D.) with increasingly sedentary behavior.27

In more recent history, the region was populated by Wichita Indians who moved southward around 1700 to inhabit the area between the Brazos and Trinity Rivers. Subtribes included the Waco, Tehuacana, and Kichai. The Wichita survived on buffalo meat and cultivated vegetables (maize, squash, melons, beans, peas, and pumpkins) while also gathering fruits, nuts, berries, and seeds. The Wichita lived in hide tipis when out on hunts but in beehive-shaped structures made of grass in more permanent villages. During the 18th century, Tonkawa Indians were also reported in the region, north of the Camino Real between the Colorado and Trinity Rivers.28

27 National Register of Historic Places Eligibility Testing of Sites 41LT172 and 41LT354 in Luminant's Kosse Mine, Limestone, Texas, Atkins North America, 2012, pages 6-7.

Texas was a sparsely settled northern frontier province of New Spain where European settlement was limited to short-lived efforts to establish missions and presidios. Transportation routes between Mexico and Louisiana consisted of a network of trails known as the Camino Real de los Tejas ("Camino Real"). Cutting across Texas from southwest to northeast in 1795, its crossings of the Brazos and Trinity Rivers became important landmarks for travelers and settlers well into the 19th century. Importantly, the Camino Real facilitated the movement of people and goods through the region, while serving as a boundary for colonization and political subdivisions.29 Although the road was rough and routes shifted based on changing weather conditions, during all periods, the Spanish, Mexican, and Texan governments regulated the Camino Real and other roads and related river crossings; the Republic of Texas required each land district to provide road maintenance and some counties used prisoners and enslaved men.30

29 It has been noted that "the development of secondary, non-governmental road networks" have "received little attention from researchers" and "were used as vital connections" between towns, ranches, and markets. A Texas Legacy, page 37.

30 A Texas Legacy, page 38

The Camino Real was influenced by the environment. The route stayed south of the post oak savannah region in which Bassett Farms is located, as the post oak savannah was “a natural barrier that delayed early travelers on their way eastward.”31 The post oak savannah region to the north of the Camino Real was a principal hunting ground for indigenous populations.32 Descriptions of the region in the late 17th and 18th century can be summarized as follows: apart from the major rivers (Brazos and Trinity), the area was interlaced with running streams that divided open woodlands from open, level plains with oaks, cottonwoods, hackberries, sycamores, pecans, and grapevines. Explorers traveling just south of Bassett Farms in what is now Robertson County noted the presence of Spanish cattle, bison, alligator, and puma, with nuisance fleas and ticks. Densely wooded areas included thorny trees that were likely mesquites and honey locusts.33

The earliest attempt at settlement in this frontier area was made in 1774 near the crossing of the Camino Real on the west bank of the Trinity River, about 65 miles southeast of Bassett Farms. It was known as Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Bucareli ("Bucareli") and it had a typical Spanish plaza, church, guardhouse, twenty residences of hewn wood, and numerous huts. The short-lived settlement failed as a result of an epidemic in 1777 and Comanche raids in 1778, and its settlers retreated to the east to Nacogdoches.34

31 A Texas Legacy, page 39, citing Gould 1969.

32 Conversation with archeologist Al McGraw, October 2020.

33 "The Natural Setting Encountered: The Sceneic Landscape," by Elizabeth A. Robbins in A Texas Legacy. Pages 263-264, "Robertson County."

34 "Bucareli," Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association.

From 1821 to 1836, the area that is now Bassett Farms was located in the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas Initially, Tejas formed one of five departments in the state with its capital in San Antonio. Later, additional departments were created including the Department of Brazos in March 1834 with its capital at San Felipe de Austin which would have included what is now Bassett Farms.

The Mexican government sought to increase settlement in its frontier regions to provide a buffer against French and American settlements to the east through the Empresario system. Large areas of land were granted to an Empresario who agreed to settle a certain number of families within a certain period of time, for which the Empresario would be rewarded with additional land. The area between the Brazos and Trinity Rivers north of the Camino Real was granted to the Nashville Company in 1825 (later known as Robertson’s Colony). Sterling Clack Robertson (1785-1842) clashed with Stephen F. Austin and Samuel May Williams who secured a grant for the same area on February 25, 1831. 35

35 For boundaries of the Austin & Williams land grant, see General Land Office Map #93836 (1833), "Texas" and Map #93853 (1835) "A New Map of Texas with the Contiguous American and Mexican States."

The ongoing legal disputes deterred settlement but were resolved when the contract for settlement was again awarded to Robertson in 1834. Robertson was to recruit 800 families who were to receive one labor (177.1 acres) of land; ranch families would receive an additional sitio or league (4,428.4 acres); single men were to receive one fourth league (1,107.1 acres). Robertson opened a land office at what he called Sarahville de Viesca, located on the west bank of the Brazos River near the falls for which Falls County would later be named.

The first titles were issued from Viesca beginning on October 20, 1834. One of those titles was for a league of land issued to Sarah Pillow on March 20, 1835. The Sarah Pillow League forms the western boundary of Bassett Farms. The league was surveyed by E. L. R. Wheelock prior to issuance of the grant and the accompanying grant identifies what is now known as Sulphur Creek as “Wheelock’s Creek” and what is now known as the Little Brazos River as “Harland" or "Harlin's" Creek. At six varas wide (16.66 feet), the creek supported a riparian zone 234 varas wide (650 feet) before entering what was described as prairie.36

No grant of land was awarded for the property that is now Bassett Farms during this early period because the coming of the Texas Revolution (October 2, 1835 to April 21, 1836) resulted in the closure of the land office at Viesca on November 13, 1835. The land office closure and the subsequent Comanche raid on Fort Parker (about 20 miles north of Bassett Farms) that killed numerous settlers on May 19, 1836, generally discouraged settlement in the region for several years after the Texas Revolution.

Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836 and its transition into the independent Republic of Texas began. In 1837, Robertson County was created with boundaries similar to those of the earlier Robertson’s

Colony. Surveyors in the new Robertson County established a frontier outpost on Mud Creek where a community developed around their outpost that became the county seat, Old Franklin. Settlement remained sparse, as fears of attacks by native tribes persisted. One such early settlement was Springfield (1838), which would later serve as the initial seat of Limestone County. In 1839, a frontier company of minute men was formed to protect settlers. In that same year, the Marlin and Morgan families were attacked near the Brazos about 15 miles northwest of Bassett Farms, and in 1841, Major Heard was killed at what is now known as Heard’s Prairie, about ten miles southeast of Bassett Farms, while on a scouting trip from Franklin to Parker’s Fort with eight other men.

Land grants in this unsettled frontier were issued under the laws of the Republic of Texas to reward families who emigrated to the Republic and men who served in the Texas Revolution. Several of these grants covered Bassett Farms, but the property was not settled and these earliest land grants were later forfeited.37

The earliest known Republic-era map depicting settlement in the area that is now Bassett Farms is the “Map of Robertson’s Colony” drafted by A. W. Cook and “made at Franklin June & July 1839.”38 The Little Brazos River is depicted with a notation that “this vacancy is surveyed but not correctly.” The only road depicted on the map is the “San Antonio Road, or Road from Bexar to Nacogdoches” well south of Bassett Farms. Just to the north of Bassett Farms, a vacant area was labeled as “rich muskeet prairies.”

Republic-era descriptions of the area were printed in 1840 and 1841. In 1840, Moore noted that “dense forests extend ... between the Brazos and Little Brazos; but most of [Robertson] county consists of prairies diversified with numerous post oak groves... The soil between the Brazos and Little Brazos is astonishingly fertile, and yields crops of corn, cotton and potatoes, unexcelled by those of any other section of the republic..."

37 One land grant was to Elijah Collard (320 acres), surveyed on December 16, 1845, centered on what later became the Bassett Home Place. Boundary references included post oaks (4", 8", 20", and 24" diameter), an elm (8" diameter), and a pin oak (12" diameter). Other grants covering Bassett Farms that were later abandoned were made to Marlin Kingsley Snell, Samuel Givens Evitts, J. L. Brady, and Thomas Mitchell.

38 Texas General Land Office Map #4656.

In 1841, William Kennedy described the area in his Texas: The Rise, Progress and Prospects of the Republic of Texas as follows:

The Little Brazos runs parallel with the main stream of the Brazos for about seventy miles… Rich timbered bottoms cover the space between the two rivers, but east of the Little Brazos, the prairie and wooded upland approach to the margin of the stream, affording the most eligible locations, while the bottoms furnish timber with an unbounded range for cattle and hogs.

These descriptions were published at the time that settlement was beginning to return to the area. A critical step was the establishment of the Torrey Brothers Trading Post in 1843 at the behest of Texas President Sam Houston. The Post was located about 25 miles north of Bassett Farms along Tehuacana Creek on the east side of the Brazos River. The trading post managed relations with area tribes and provided a sense of protection for new settlers in the area. It was near the Torrey Post that representatives of the Republic of Texas would regularly meet with tribal chiefs; a peace treaty signed there in 1844 provided regional stability.

The Torrey Brothers Trading Post encouraged the development of trading networks, dealing principally in deer, beaver, and bear hides. Goods would be transported to and from the Texas coast by way of ox-carts along unlocated trails east and west of the Brazos River, as the river itself was not navigable as far north as the Post. An early map of the region drawn by Stephen F. Austin in 1827 shows the location of the Camino de los Huecos a San Felipe de Austin, a road linking the Hueco (Waco) Indian village site on the Brazos River with Austin’s capital of San Felipe further south along the Brazos; this camino might have later served as Torrey’s ox cart road.

Other road networks existed, one of which linked Torrey's post with the small settlement of Alto or "Alta" Springs just a mile south of Bassett Farms. A letter in the Indian Papers of Texas 1844-1845 dated May 12, 1845 makes reference to “the path from the [Trading House] to Alta Springs.” Alto Springs was settled by Dr. David Seeley in 1844; a post office and stage stop was established shortly thereafter. A path from Torrey’s Post to Alto Springs would have passed through or very near to Bassett Farms.

Apart from these early primitive trails, the lack of transportation networks meant that crops had little value unless used locally, whereas cattle could be driven to points south (and later north) by land. Consequently, early settlers

to the open range during the Republic era were principally interested in raising cattle and horses, with farming limited to subsistence needs.

After Texas became a state in 1845, settlement began to increase at a greater rate. In the late 1840s, the Blue Ridge region west of Bassett Farms was settled by stock-raisers and small farmers principally from Tennessee. In the 1850s, several farmers moved to the region with enslaved men and women, but in general, 1850s agriculture in the immediate vicinity of Bassett Farms made only limited use of enslaved labor. This is in contrast to large plantation operations that were developed in the 1840s and 1850s further west in Falls County along the Brazos River bottoms by Churchill Jones and in northern Limestone County by the Ethan and Logan Stroud.

Oral histories collected during the Depression included that of Mattie (Keyser) Hunnicut. She was interviewed in 1936 and shared that most of the early Blue Ridge settlers lived self-sufficiently in log houses. Later, the northern part of the Blue Ridge settlement took the name of Stranger. She explained:

The Stranger community on the Ridge can be seen for miles from the Waco-Marlin state highway. In fair weather, there is always a deep blue atmosphere over it, hence the name of Blue Ridge… You may stand on the Ridge and look westward where you can see the broad valley as it abruptly drops down below you with a ravine between the Ridge and the valley. In the fall of the year cotton pickers can be seen swinging to and fro, gathering the fleecy staple. Tall trees, sloping hill and beautiful prairies form a never-to-be forgotten picture…”

East of Bassett Farms, a small community developed in the 1850s on Duck Creek called Eutaw, serving as a small commercial area for farmers and ranchers until the coming of the railroad in 1870 when the town’s residents moved 1.5 miles west into the new town of Kosse. Stage routes connected Franklin, Eutaw, Alto Springs and other small communities with more populous areas to the south. Mail routes were also established that connected Franklin to Springfield, the county seat of the newly formed (1846) Limestone County, close to the old Parker’s Fort. Another route passed through Alto Springs, suggesting another trail or road that crossed east-west through or near to Bassett Farms.

During the late antebellum period in 1857 a surveyor wrote a letter to the Southern Intelligencer newspaper (Austin) describing the area around Bassett Farms:

This morning we traveled to Alto Springs in Limestone County, which is a fine rolling country, well wooded, but not so well watered, but wells can be dug and water can be had. The country where we are now is like that north of Austin, but better land… The 27th [of April 1857] … our route lay through a country called the blue ridge, from the beautiful divide it makes between the Brazos and other streams, and also from its healthy locality. The country here is very

thickly settled, and some fine large farms are to be seen. The Spring wheat looks well. The people appear to have plenty of every article of consumption…

Settlement was given encouragement in the 1850s by a new state law passed in 1852 requiring those who had received early land grants as far back as the 1830s to file them with the General Land Office no later than August 31, 1853; otherwise, the grants would be forfeited and the land would be regranted. As a result, land that had been tied up but otherwise unsettled for decades was opened up for settlement. Most of the land that is now Bassett Farms had been held up in this way. The new owners of land at Bassett Farms were John G. Walker, who lived elsewhere and held his land for more than a decade, and Dr. Augustine Owen, who immediately sold his property to longer-term speculators. One such speculator was B. J. Chambers (1817-1895), a surveyor who in 1855 and 1856 purchased nearly 900 acres in Falls and Limestone Counties from Dr. Owen, much of which would later become part of Bassett Farms. Chambers only began selling his holdings in 1869 after the projected route of the Houston & Texas Central Railroad had become known, which would run about three miles southeast of Bassett Farms, dramatically raising property values.

Antebellum-era settlers to the frontiers of Falls and Limestone counties used the open prairie to raise cattle and horses. The prairie provided a nutritious supply of native grasses: bluestem, grama, and buffalo or "curly mesquite" grass. In 1840, Moore's Map and Description of Texas helped to reinforce the mythos of the Texas frontier stockman, which was established early in Texas culture:

There is probably no class of men upon the globe who can live more independently or with less care and labour than the herdsmen of Texas. Their herds of cattle feed out upon the prairies or in the wooded bottoms during the whole year and require almost as little attention as the wild deer. The herdsmen drive them into their pens once a year, and brand the calves in order to distinguish them from their neighbors.39

In 1850 in Limestone County, 8,638 acres were improved and 326,374 acres were grazed. Of the 279 farms in the county, only 603 bales of cotton were produced. There were 13,294 beef cattle; cattle sold from $2 to $5 per head. As late as 1879, almost a decade after the coming of the railroad, cattle was still being driven to market along public roads and trails.40 However, for the most part stockmen eagerly took advantage of rail transport when it became available. R.A. McAllister remembered his father in the 1860s as "a stock man. We did not raise cotton… The cattle were taken to Marlin, after the Houston & Texas Central Railroad was built from Houston to Waco, and shipped to the markets. Before that time, the men would go together and drive their cattle up the trails to the market as in Abilene and Kansas City."41

As the Comanche were pushed further north and west out of the region and the frontier became more settled by the 1850s, cotton production expanded from the southeast coastal regions inland into the alluvial soils along the

39 Moore, Map and Description of Texas, page 9.

40 Walter, History of Limestone County, 127.

41 Oral History of R. A. McAllister, Library of Congress.

Brazos River and other streams. These larger-scale operations were owned by Texas planters who introduced slavery into the mid-Brazos Valley as they opened the Brazos bottomlands to cotton planting. Yet outside of these rich bottomlands, the prairies and post oak savannas of eastern Falls County and southwestern Limestone County, stock raising persisted until a decade after the Civil War until the arrival of barbed wire about 1876.

The handful of early settlers along the Blue Ridge who brought a small number of slaves with them in the 1850s to cultivate cotton did not compare to the extent of major planters such as Churchill Jones on the Brazos or the Stroud family on the Navasota, with their thousands of acres and hundreds of slaves. By 1860, Falls County had 504 farms and a population of 1,716 slaves, comprising 47 percent of the total population. While cotton was significant, it did not dominate the county's agriculture. In 1860, the county's sheep ranches produced 17,500 pounds of wool and 26,310 cattle grazed the open range..42

The establishment of Bassett Farms in February 1871 and the settlement of the Town of Kosse on the new Houston & Texas Central Railroad are inseparable. This new railroad brought Henry Bassett to Kosse at a time when the new city was the terminus of the line. The Houston & Texas Central would make it possible for the Bassetts, their tenants, and their neighbors to purchase goods from and ship their farm products to coastal markets and to otherwise participate in the economic life of the state and country. With a direct link from Kosse to Houston by rail and from there to Galveston, New Orleans and other Gulf ports, agriculture on a commercial scale was now possible.

The Kosse townsite was surveyed in late summer 1870 to become a depot town on the Houston & Texas Central Railroad and was later incorporated by the Texas legislature in May 1871. For six months, from October 1870 to April 1871, Kosse was the terminus of the railroad as it was being constructed to link Galveston and Houston to Dallas and the Red River. On August 6, 1870, the Bremond Central Texan reported that the “Central Railroad Company have [sic] completed the survey of the future town of Kosse, ten miles distant [from Bremond], the whole area comprising two hundred acres. Business lots are held at $400 for inside lots, and $500 for corner lots again fixing a bait for the unwary, which will be sugar coated as usual.” Lot sales began immediately; for example, a deed for Lot 8 in Block 7 to M. L. Jackson for $600 gold was dated August 8, 1870.

By August 19, 1870, the Galveston Tri-Weekly News noted that the construction train was about five miles north of Bremond, half-way to Kosse. Later in August, merchants were in Houston buying goods to sell in Kosse even before the track was completed. “It … bids fair to be a large town, even before the track is laid to that point.” The Houston & Texas Central had struggled to accommodate the massive demand for cargo capacity, both on the ground in its new railroad towns but also on the rails themselves. As a result, major backlogs of goods sat on both ends of the line. To avoid this in Kosse it was announced in September 1870 that “in order to obviate the trouble that occurs in opening each station, we have concluded to put up temporary buildings [in Kosse] and lease them to commission merchants…” The backlog was, however, unavoidable; a Galveston merchant took out an advertisement to apologize for circumstances out of his control resulting in goods sitting out in the sun waiting for shipment inland.

During this terminus period in late 1870, Kosse became a “mushroom” town of nearly 3,000 residents and 600 hastily-constructed mostly temporary buildings. The Houston & Texas Central provided a route for

immigration inland to the Texas frontier. Land promoters circulated promotional materials throughout the United States and Europe in an effort to draw settlement to the region. Increased population, stimulated by the development of new towns along the railway, would in turn increase the profitability of the railroads through increased passenger and freight traffic. Increased population would also lead to increased agricultural production. The Handbook of Texas noted that "the number of farms in Texas rose from about 61,000 in 1870 to 174,000 in 1880 and 350,000 in 1900."43

Stage routes connected the Kosse terminus to points west, north and east, and the new town served as the primary point of immigration to inland Texas. So many people passed through Kosse in late 1870 that a newspaper editor pleaded for an immigration officer to be posted there. The post office in Kosse also handled over 1,000 pieces of mail daily on account of its being a funnel for mail to and from the frontier, to say nothing of the bales of cotton, hides, and other goods delivered to Kosse from much of north central Texas for shipment down the new rail line to the Gulf ports. The town was named for civil engineer Theodore Kosse, an employee of the Houston & Texas Central who had “laid out every mile of this road from Houston, and [had] devoted all his time to it for sixteen years” before quitting in August 1870 for failure of the railroad to make good on debts owed to local residents along the line who provided labor and material for the construction of the road.

The temporary yet large-scale nature of development in Kosse was reflected in the scale of the depot itself: it was 600 feet long. The flimsy structure was blown down in the “hurricane” that struck Kosse on May 2, 1871, several weeks after Groesbeck, seventeen miles north, had become the new terminus. On November 10, 1870, The Galveston Daily News reported that a new telegraph office had been opened at Kosse “the present terminus of the Central Railroad” which was “good news for many of our [Galveston] merchants, as the business with the new town of Kosse is quite large.” The telegraph was followed by the Enterprise, a Calvert newspaper that moved to Kosse in December and was noted for being “Democratic in politics, and a well-edited and neatly-printed journal.”

The train schedule changed on November 14th such that northbound trains leaving Houston at 10:30 A.M. would reach the terminus at Kosse at 8:20 P.M. Southbound trains leaving Kosse at 6:15 A.M. arrived in Houston at 4 P.M. The Houston & Texas Central wanted to show off as much of the trip as possible in daylight so as to promote the opportunities for development along its route. But Kosse's six month terminus period ended as abruptly as it began. On April 3, 1871, the Houston & Texas Central advertised that “PASSENGER TRAINS will leave Houston daily, (Sundays excepted,) at 11 A.M. and 8:15 P.M., reaching Groesbeck, the present terminus, at 10.20 P.M. and 12 M[idnight].” with stage connections “at Kosse for Waco.”

A regional history published in 1893 reflected that “the terminus periods of Kosse and Groesbeck were characterized by all the influx of what may be called ‘portable terminus merchants,’ who moved as the terminus moved, eager to supply the great trade that gravitated to it for scores and scores of miles in all directions. This brought a motley and mixed population along with it, so that in both places, while the terminus feature lasted, they were cities overgrown and unwieldy to be sure, but cities nevertheless… Motley as much of it seemed at the time, it was also mixed in large proportion with men of enterprising mold, many of whom are now prominent commercial and social leaders in these places… As soon as the terminus feature was removed from Kosse and Groesbeck they became small towns of a size fitted to supply the country back of them…”

By contrast, just two years after Kosse’s frenetic birth as a terminus town, Logan’s Railway Business Directory described Kosse in 1873 as a town of “about 200 inhabitants and is doing little business. When it was the terminus it was a thriving place, now its glory has faded. Cattle constitute the bulk of shipments from here.”

The arrival of the railroad in the region in 1871 brought diverse waves of new settlers seeking opportunities to farm rather than ranch, bringing diverse cultures, practices, and traditions to the region around Bassett Farms. This included Germans around Otto and Perry in northern Falls County and Westphalia in western Falls County, Italians around Highbank in central Falls County, and Poles around Bremond in Robertson County. Black and white families from the war-ravaged South also came to Texas through much of the 1870s and 1880s to settle new farms on the blackland prairie. Once barbed wire arrived about 1876, "the free range played out and the whole country was turned into farming," said George Ogden:

The first car load of wire came to Marlin … and the rail-road agent had a hard time getting any one to take the agency. After a long parley he finally induced Mr. Barclay, of the firm of Barclay Hardware Company, to take the agency. He refused to have anything to do with the wire unless the railroad company bore the expense, but in a week the first car had been sold and four more cars were asked for, after this the wire was sold faster than it could be delivered. The first car reached Marlin ... and I bought three spools from this car and used it for water gaps to hold my cattle.44

Barbed wire was a major development impacting rural land use and the rural economy. Invented in 1873, "barb wire" patents had been consolidated by the Washburn & Moen Manufacturing Company by 1876. This same

44 Oral History of George Ogden, McLennan County, Texas, District 8, File No. 240, page 10. Library of Congress. Ogden states that the first carload came in 1879, but it was likely several years earlier based on other news accounts.

year, a demonstration of barbed wire at the Alamo in San Antonio was said to have helped popularize its use, and a publication by the company extolled its virtues while illustrating its idealized installation and use.

Journalists and travelers exploring Central Texas by rail reported to Texans (and to East Coast newspapers) that these newly opened interior lands were "splendid country for corn and cotton."45 Despite periodic droughts and floods, the area's soils were productive, with cotton becoming the leading cash crop and corn an important staple for feeding people and livestock. Local agricultural news focused on little else:

● 1879: "Farmers east of Kosse say the cotton crop is flattering, while the corn crop is cut short. On Blue Ridge crops, both corn and cotton, are fair. We think enough will be made in this portion of the country for home use."46

● 1881: "Crops are suffering very much here at present for want of rain. The corn crop will probably be cut off; the cotton, however, is looking fine, and with rain soon will be a very large crop."47

● 1885: "Cotton is coming in well; receipts for this season show 100 per cent increase over last year. Our town [Kosse] has received and sold more goods up to this fall than any time since it was a railroad terminus."48

The growth in cotton production between 1880 and 1930 was also matched with population growth. In Falls County, the number of farms grew from 2,492 (1880) to 6,014 (1930), while the population grew from 16,238 to 38,771, more than double the 2020 Falls County population of 16,968. Cotton bales increased from 12,495 in 1880 to 61,989 in 1930, the highest ever in Falls County.49 By 1930, 73.8 percent of farmland in Falls County was devoted to cotton, and 15.2 percent was used to grow corn.

45 "Letter from Kosse," Houston Daily Union, 15 December 1870.

46 "Limestone," Galveston Daily News, 26 May 1877, page 4.

47 "Fairview Springs, Texas," Topeka Weekly Times, 25 July 1881, page 2.

48 Fort Worth Daily Gazette, 4 November 1885, page 6.

49 Falls County, TSHA Handbook.

Limestone County historian Doris Hollis Pemberton documented that cotton production was labor-intensive, relying heavily on Black labor. She noted that in 1912, Limestone County was the leading county for cotton production in Texas, and that:

profits were made owing to the prodigious labor of seasoned field hands… They could predict the weather by looking and listening to the descriptions of the skies, by the feelings in their bodies, and the activities of the animals and foul. The wet lands and mild climate bred malaria… Cotton choppers' hands were calloused. Their feet and legs were often wet. Working from sunrise to sunset cotton pickers' hands and clothes were wet with cool dew that hung on the pods and thick leaves of the cotton until about dinnertime… Their bodies became distorted and stooped. Their knees were sore and painful from the back-breaking work in the hot sun...51

Pemberton also investigated the kind of cotton grown in Limestone County. She found that between 1850 to 1900, "the leading kinds of cotton grown by Limestone County farmers were the Mexican big boll type and its successor, the Texas big boll type. At the turn of the century, many farmers were growing the Texas storm-proof type." In the early 20th century, farmers experimented with the Lankart, Rowden, and Mebane types.52

50 Soil Survey of Falls County, Texas, 1932, p.5.

51 Pemberton, Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing, 25.

52 Pemberton, Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing, 26.

The expansion of cotton farming and the elimination of the open range with barbed wire came at the expense of stock raising. The cattle, sheep, and horse raising that supported the economic life of the earliest settlers in the region all but vanished. By 1930 the Falls County Soil Survey reported that "there are no large ranches or livestock farms in the county."53 In Limestone County, the number of cattle fell to 19,236 in 1920 and 18,929 in 1930, as hay acreage and rangeland continued to be converted to cotton production.54 The total domination of farming over ranching was also reflected in these 1930 statistics: 89.5 percent of Falls County was in farms, of an average size of 70.9 acres. Similarly, 78 percent of Limestone County was in farms, with 257,932 acres in cotton.55

Apart from cotton, a small amount of truck farming was carried on, principally potatoes, sweet potatoes, and watermelon. As noted in the Soil Survey of Falls County (1932), "the agriculture has always been more especially concerned with the production of cotton as a cash crop and the growing of feed crops … to provide for the local and home requirements of the farm livestock."56 Market gardening in 1930 also included pecans; there were 8,930 bearing pecan trees in 1929, producing nearly 60,000 pounds of nuts. Other produce included peaches, pears, plums, grapes, and berries; dark soils were favorable for onions, cabbage, garlic, and similar plants.57

53 Soil Survey of Falls County, p. 7.

54 "Bassett Family Home Place," RTHL nomination, p. 3.

55 "Bassett Family Home Place," RTHL nomination, p. 3.

56 Soil Survey of Falls County, p. 4-5.

57 Soil Survey of Falls County, p. 6.

Cotton peaked in 1929. But change came quickly as the price of cotton fell and concerns about erosion and depletion of the "exhausted" soil grew. As Mrs. Bassett noted in the fall of 1931:

We made a good cotton crop, but the price was so low it did not amount to much. We will have to keep on trying, and trust in the Lord for guidance. I never heard so much cry of hard times in my life. No business doing. The cotton law past [sic] by the Legislature will make it hard on the poor class of people and negroes for another year.58

Mrs. Bassett makes reference to the Texas Cotton Acreage Control Law, passed on September 22, 1931, that restricted the amount of cotton planted in 1932 and 1933 to no more than 30% of that planted in 1931, and prohibited planting cotton on the same plot of land for two successive years after 1933. A lawsuit filed in neighboring Robertson County in 1932 resulted in the declaration of the law as unconstitutional and consequently null and void, a decision upheld by the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in March 1932.

President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Agricultural Adjustment Act into law on May 12, 1933. Its goal was to reduce crop surpluses, raise commodity prices, and support struggling farmers. The program directly impacted Limestone County farmers like the Bassetts and their tenants. In 1933, a total of 3,795 Limestone County farmers, who had planted 190,618 acres of cotton, contracted with the U.S. Department of Agriculture to plow up 69,746 acres or approximately 36.5 percent. Only 35 farmers in the county refused to participate. In exchange, farm owners would receive a total of $736,85759 but many of the neediest tenants and sharecroppers received nothing.

The federal program required that cotton crops had to be fully destroyed to receive a payout; young plants could be plowed under, while more mature stalks could be cut through. Texas A&M offered suggestions to farmers for replacement crops to enhance a shortage of feed, including grain sorghums for forage, sudan grass for grazing and hay, red top sorghum for hay or bundled forage, cowpeas for hay or forage, millet for hay and stock beets for succulent feed. It was also suggested that seed could be planted between rows of cotton before the cotton was destroyed to ensure that a crop would have enough time to grow.60 As a consequence of the 1933 plow-up, that year's harvest was the lowest in Texas since 1922.61 The Extension Service at Texas A&M reported that as a result of federal payouts of $42 million in Texas, "old debts and back taxes" were paid off, with some money going into "purchase and repair of farm machinery … many farmers report that the cotton program has put them in the best financial position they have had since 1928 or 1929."62

With respect to Bassett Farms, Mrs. Sparkman, Henry Bassett's granddaughter, wrote in 1989:

58 HF Bassett to Fred and Gladys Glass, 30 October 1931. Glass papers, UT Arlington.

59 "Limestone Farmers to Get $736,857 from Federal Fund," Mexia Weekly Herald, 21 July 1933.

60 "Tells How to Make Use of Cutover Lands," Mexia Weekly Herald, 28 July 1933, p7

61 "Texas Cotton Crop Shortest Since in 1932," Mexia Weekly Herald, 11 August 1933, p8.

62 "Farmers Feel Better After Forty MIllion," Mexia Weekly Herald, 1 December 1933, p6.

Sixty or more years ago (1929), most of Bassett Farm was planted in cotton by tenant farmers. Fields were kept clean and clear of weed and brush. But cotton production ended when the conservation program was instituted. No improvements have been made in the fields since that time and they are now overgrown heavily with mesquite trees and weeds.63

The oncoming Depression, coupled with the federal programs aimed at reducing farm production, led to a decrease in the number of farms in Limestone County from 6,081 in 1930 to 3,427 in 1940. The county's population also fell during the same period from 39,497 to 33,781.64 By 1950, farm tenancy dropped in Limestone County to 40 percent, with the average farm size rising to nearly 200 acres. Former cotton acreage was converted to improved pasturage for livestock grazing. Cotton acreage further declined from 118,776 in 1949, to 8,300 acres in 1977 that produced a mere 1,400 bales of cotton.65

Through the 1940s and 1950s, limited cotton production continued at a small scale at Bassett Farms. In 1960, the Old Ocean Pipeline Company documented a field in cultivation on the Vann Place; the Bassetts produced a photograph of one of the granddaughters sitting there in a cotton field. Aerial photographs also suggest areas of carefully cultivated fields and even a new tenant house in the 1950s, and receipts and canceled checks document the continued improvement of tenant houses during the same period.

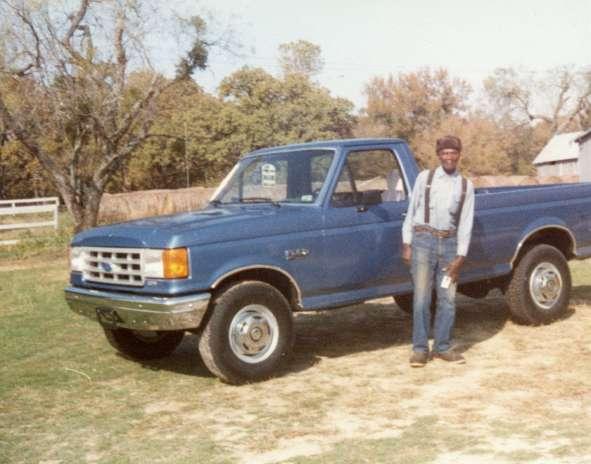

Eventually, however, cotton production did come to an end at Bassett Farms, and Mrs. Sparkman noted that between 1969 and 1989, only 62 acres at Bassett Farms were under cultivation for hay, consisting of three plots (35, 15, and 12 acres). Half of the remaining land was leased for grazing at $10 per acre and the other half was retained for the Bassett's own herd of polled Hereford cattle.66 Cattle grazing had once again became the dominant agricultural land use in the Kosse region. The Bassetts regularly purchased registered bulls and routinely sold cattle at auctions such as the one in Groesbeck. Receipts show thousands of dollars earned at sales annually through much of the 1950s and 1960s. Ranchers like the Bassetts invested in planting Johnson grass and numerous variants in order to improve the quality of the food supply for cattle.

After the death of Willie Ford Bassett in 1967, his daughters continued to manage the herd from Dallas, a challenge that by the early 1990s had become difficult to continue. A lack of on-site management and expertise left the herd was left to inbreed, wander, and otherwise struggle on increasingly overgrazed and unproductive pastures. Neighboring ranchar Ronald Stone lamented that the once-carefully managed ranch land at Bassett Farms was regularly patrolled by vultures in search of the latest fallen cow.

As cattle returned in large numbers at Bassett Farms in the mid-20th century, with a herd well in excess of 200 head of cattle, the Bassetts focused on securing the supply of water for their livestock through building stock

63 Sparkman tax protest, 1989, Bassett Archive.

64 "Bassett Family Home Place," RTHL nomination, p. 4.

65 Pemberton, Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing, p. 26.

66 "Condition and Use of Land in Bassett Farm Property," 1989, Bassett Archive.

ponds, known as "tanks." To guide ranchers, in 1940 the USDA published Stock-Water Developments: Wells, Springs, and Ponds 67 It differentiates between natural stock-water supplies (springs, streams, and lakes) and constructed water supplies (wells, artificial reservoirs, and ditches). Springs and wells were often fed by underground sources, while streams and reservoirs were generally supplied by surface water.68 The average daily consumption needs per head of cattle is between 10 to 12 gallons, depending on the season and local conditions.69

At Bassett Farms, at least twenty stock tanks were built by forming an earthen dam using soil excavated from to form a basin; the dams restricted the flow of runoff water through pastures during major rainfall events that would otherwise have flowed directly into Sulphur Creek or the Little Brazos River. In addition to providing water for livestock, these tanks were stocked with fish, provided habitat for waterfowl, attracted game, and could also be used to fight fires. An article in the Mexia Weekly Ledger in 1940 encouraged stabilizing farm pond spillways with Bermuda grass and fencing the ponds to prevent livestock from trampling, damaging, and contaminating ponds; pipes through the dams to feed troughs were thought to be the best way to water.70 In 1949, a USDA publication recommended watersheds of 10 to 30 acres as ideal for individual stock tanks, adding that "the watershed should be covered with grass or ungrazed trees and shrubs … [and] free from any source of contamination."71

The major 1950s drought led to a second phase of post-cotton tank construction. In 1957, the Kerrville Times noted that "thousands of small impoundments have been created by putting dams across small dry stream beds within the state during the last several years."72 A July 1957 Farm Pond Survey found 342,000 ponds, averaging less than eight years old.73 In the 1960s, land management and soil conservation experts were recommending the careful dispersal of stock tanks across a ranch so as to encourage rotational grazing and discourage overgrazing.

67 Farmers Bulletin No. 1859. UNT Digital Library.

68 Stock-Water Supplies, page 4.

69 Stock-Water Supplies, page 5.

70 "Value of Farm Ponds Realized by Farmers," Meixa Weekly Ledger, 1 March 1940, p3

71 Atkinson, Walter S. How to Build a Farm Pond. USDA Leaflet No. 259 (1949), p. 2.

72 Kerrville Times, 24 August 1957, p21.

73 "Lots of Farm Ponds in State," Lubbock Evening Journal, 3 December 1958, p22

Evan R. Thompson

Evan R. Thompson

The Bassett Home Place consists of 160 acres acquired by Henry Bassett in 1871 and an additional 16 acre wedge of land acquired from J.E. Vann in 1883. The Home Place is located almost entirely in Limestone County, Texas; the Limestone-Falls county line runs north-south through the far western portion of the Home Place.

The lands out of which the Home Place tract was created by 1869 had been granted in the 1850s to John G. Walker (northern portion) and Dr. Augustine Owen (southern portion). Surveyor and speculator B.J. Chambers acquired most of the Walker and Owen lands and sold a smaller 160-acre parcel to Sidney M. Jones who in turn sold it to Henry Bassett.

Sidney M. Jones Ownership (1869-1871)

Sidney M. Jones (1832-1901) was born in Georgia and settled near the Eutaw community, east of present-day Kosse, in Limestone County before the Civil War. He deserted the Confederate Army and later became one of the leading white Republicans in the county. Jones purchased 160 acres from B. J. Chambers on October 8, 1869 for $800 gold. The deed referenced the southeast corner of the property as being 250 varas east of Jones's house and 500 varas north of the Sulphur Spring; this is the approximate location of the present 1875 Bassett House.

The presence of a house on the site at the time of Jones's 1869 purchase suggests that he (or someone) had been living on the property prior to that time.1 That same year, Jones was taxed in Limestone County on 160 acres ($640), 100 horses ($2,620), 20 cattle ($80), and miscellaneous property ($140) for a total value of $3,480.2 The following year the tax list omitted his real property, but included 100 horses ($2,500), 12 cattle ($48), and miscellaneous property ($215) for a total value of $2,763.3

On May 19, 1870, Jones took his oath as Limestone County Sheriff and three days later on May 22nd he took his oath as Justice of the Peace for Limestone County, Precinct 4.4 In the 1870 census taken in June, the 37-year-old Jones was recorded as a "planter" living with his wife, Eura, and three children Annie, Albert, and Robert, and two others (Columbus Bragg, age 11, and Ben Hammonds, 22, a planter born in Mississippi). He owned real estate valued at $1,600 and sizable personal property valued at $6,850.5 The agriculture census of 1870 noted that he owned 20 horses, 4 mules, 50 cattle and 100 swine. His 65 improved acres produced 600 bushels of corn.6 In 1871, Jones became a central figure in the aftermath of the murder of D. C. Applewhite (first cousin and brother-in-law of Hattie Ford (Pope) Bassett), an event that triggered the declaration of martial law in Limestone County. He also provided testimony about the contested Congressional election of 1871.

1 Jones was taxed on property elsewhere in Limestone County in 1868 and likely did not move onto the property until 1869.

2 1869 Limestone County Tax list, page 15 (image 18)

3 1870 Limestone County Tax list, page 16 (image 17)

4 Texas, U.S., Bonds and Oaths of Office, 1846–1920

5 1870 US Population Schedule, 48th District of West Texas, Limestone Co., Texas.

6 1870 US Agriculture Schedule, 48th District of West Texas, Limestone Co., Texas.