SUURSAATKOND THE FINNISH EMBASSY TALLINN

SOOME SUURSAATKOND THE FINNISH EMBASSY TALLINN

SISUKORD / CONTENTS

LUGEJALE TO THE READER

Peeter Talvar: ARHEOLOOGILISED KAEVAMISED SOOME SUURSAATKONNA TERRITOORIUMIL ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS AT THE SITE OF THE FINNISH EMBASSY

Juhan Maiste: AADLIPALEE TOOMPEAL THE TOOMPEA MANOR

Simo Paavilainen: ARHITEKTUURNE PROJEKTEERIMINE ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Asko Rahikka: PROJEKTEERIMISTÖÖD STRUCTURAL DESIGN

LUGEJALE

Vaevalt võiks Soome suursaatkonna maja Tallinnas olla kesksemal ja esinduslikumal kohal kui Toompea all-linna poolsel nõlval aadressil Kohtu 4/ Pikk Jalg 14. Soome Vabariik omandas kinnistu 1926. aastal ja sai oma vana maja jälle tagasi 1993. aastal. Kolm aastat hiljem põhjalikult taastatud hoonesse kolides naasis saatkond Eesti poliitilisse keskmesse, Toompeale, kus tegutse vad nii Riigikogu kui ka Eesti Vabariigi valitsus.

Soome suursaatkonna maja restaureeriti äärmise hoolikusega. Lõpptulemuses väljendub sügav austus ja lugupidamine kõigi nende ehitusajalooliste kihtide suhtes, milles nüüdne, algselt eri kinnistutest koosnenud ehituskompleks on välja kasvanud. Ehkki pinnasekiht katab jälle kihis tustest vanimaid, teadmata millal maha põlenud rauaaegseid puitkonstruktsioone, on keldrisü gavuses jäetud kõigile vaatamiseks kivivundamendi vanimad osad. Teatud hulk arheoloogili sest leiumaterjalist on koondatud omaette väikeseks muuseumiks. Teise maailmasõja järgsest aastakümnete pikkusest lagunemisprotsessist on jäänud üksnes mälestus, varasemate aegade algupärasest interjöörist on säilinud õige vähe. Esindusruume valgustavad siiski ennesõjaaegsed kroonlühtrid: need olid seisnud aastakümneid Helsingis − lahti pakkimata! − 1940. aastal eva kueeritud kraami hulgas.

Oma spetsiifilisest ajaloolisest väärtusest hoolimata on saatkonnahoone eelkõige hästi funktsio neeriv ruum, mis vastab riikliku esinduse vajadustele Soome jaoks tähtsal naabermaal. Restau reerimise projekteerijatel oli täita äärmiselt nõudlik ülesanne: oma asendi tõttu sopilises majas asetsesid ruumid koguni seitsmel eri tasandil, aga neisse ruumidesse suudeti siiski paigutada kaasaegne, mitmeid eri ülesandeid täitva diplomaatilise esinduse vajadustele vastav büroo.

Alates maja renoveerimisest 1996. aastal on saatkonnahoone kasutajate missioon olnud armas tusega hoida ja säilitada saavutatud suurepärast lõpptulemust. Käesolev trükis kõneleb sellest ehituskompleksist ja tema ajaloost.

Soome suursaatkonna ajaloost ja tegevusest Eestis annab parima ülevaate 2015. aastal Jussi Pekkarise sulest ilmunud väärikas teos Kohtu tn 4 (SKS; e.k. Varrak).

TO THE READER

It would be difficult to conceive of a more prominent location for the Finnish Embassy in Tallinn than the Kohtu Street 4/Pikk Jalg 14 property, situated on the Toompea hill overlooking Tallinn’s Lower Town. The Republic of Finland bought it in 1926. In 1993, Finland regained possession of its former embassy building; three years later, diplomatic personnel moved into a thoroughly renovated structure. The Embassy’s proximity to the Estonian Parliament at Toompea Castle brought it once again into close contact with Estonia’s political centre of gravity.

The Finnish Embassy building was renovated with extreme care and respect for the historical architectural stratification that has accumulated over the centuries in a complex that once consisted of separate properties. The earliest layers, such as the burnt remains of wooden construction dating from the Iron Age, still lie buried, but older stone foundations left standing in basement depths serve as a small museum for archaeological objects unearthed on the site. Fortunately, the building’s physical deterioration brought on by decades of neglect following World War II is now only a memory. Only traces of the original interior furnishings remain, but reception spaces are lit by the same chandeliers used during the pre-war period; brought to Helsinki during an evacuation in 1940, they were later discovered by chance in unopened crates.

Despite its complex history, the Finnish Embassy is a workable building supporting Finland’s diplomatic interests in an important neighbouring country. In this respect, renovation planners were faced with a formidable task. The Embassy’s structure, a combination of seven floors, was labyrinthine in places owing to the steep site. Within a rich historical framework, planners and builders however succeeded in creating a modern and multi-purpose facility meeting Finland’s diplomatic needs.

Ever since the completion of the renovation in 1996, it has been the honorable task of the Finnish diplomats and embassy staff in Tallinn to maintain and cherish the wonderful results of the restoration work. This booklet tells about the fascinating and colourful history of the embassy building.

ARHEOLOOGILISED KAEVAMISED SOOME SUURSAATKONNA TERRITOORIUMIL

Peeter Talvar, kaevamiste juhataja, arheoloog

Soome suursaatkonna rekonstrueemistöödega seoses toimusid 1995. aasta talvel ja kevadel kae vamised Kohtu tn 4 hoovis ja keldrites.

Tallinna ajaloo seisukohalt oli tegemist üliolulise piirkonnaga, sest just siin, Toompea kõrgemas osas, võis asuda eestlaste muinaslinnus. Arheoloogilised kaevamised osutusid üllatavalt tule muslikeks. Seni vanimad jäljed inimasustusest leiti just saatkonna territooriumilt. Hoovi idaosas avastati looduslikku aluspinnasesse süvistatud poole meetri sügavune ja sama lai ümar lohk. Kunagise koldekoha põhja olid asetatud rusikasuurused munakivid. Kivide peal lasunud söe kihist võetud radiosüsiniku (C-14) proovi analüüsi põhjal võib öelda, et 7. sajandi teisest poolest kuni 9. sajandi lõpuni elati Toompeal kerisahjudega köetavates hoonetes. Inimeste elutegevusest annavad tunnistust kultuurkihist leitud savinõude killud.

Kuigi muinaslinnuse ehitiste jälgi polnud kultuurikihis säilinud, oli puitlinnus siin hiljemalt 11. sajandil olemas. Sellest andsid tunnistust savinõude killud kultuurikihis. Linnuse pärast 13. sa jandi alguses eestlaste, taanlaste, sakslaste ja venelaste vahel peetud võitlustest annavad tunnis tust arheoloogilistel kaevamistel leitud relvad – ammunoolte- ja viskeodade rauast otsad.

Tõenäoliselt ei elatud linnuses pidevalt, vaid siia tuldi ainult otsese hädaohu korral. Saatkonna peasissekäigu ette jäävalt alalt leiti seitsme Taani aega ehk 13.–14. sajandisse kuuluva puithoone jäänused. Hoonetest olid alles alumised seinapalgid või neid toestanud kivid. Kahes hoones olid säilinud kerisahjude alused – järelikult kasutati neid elamutena. Ülejäänud hoonete puhul oli tegemist majandushoonetega sh lautadega (otsustades hoonetest väljaspool lasuvate sõnnikukih tide järgi).

Samast kohast leiti ka palkidega sillutatud tee ja ilmselt kahte kinnistut eraldanud palktara jäänu sed. Saatkonna edelapoolseimast keldrist leitud palktee haru suundus Toompealt alla, Tõnismäe suunas. Kohtu tänava poole jäänud kaevandist leiti kahe savilaos keldrimüüridega 13. sajandi lõ pus–14.sajandi esimesel poolel kasutatud eluhoone jäänused. Hoonete vahelt suundus kruusaga sillutatud tee lõunasse: klindi serva ja Toompead ümbritsenud ringmüüris olnud torni suunas. Viimase jäänused leiti arheoloogiliste kaevamiste käigus. Torni keskaegsetel müüridel on ekspo neeritud valik arheoloogiliste kaevamiste käigus saadud leidudest. Saatkonna keldritest leiti siin asunud lubimörtseotises hoonete keldrimüüre, mis hävisid tõenäoliselt Toompea suurtulekahjus 6. juunil 1684. aastal. 19. sajandi keskel omandas krunt tänapäevase ilme (hoonestuse). Suurima osa arheoloogilistest leidudest moodustasid savinõude killud. Nendele lisaks saadi roh kelt teisigi igapäevase olmega seotud esemeid nagu rauast nuge, luust kamme ja nõelu, samuti rauast ukselukke ja uksehingi. Rohkelt oli leidude hulgas hobuseriistu: hobuseraudu, suuraudade katkeid, raudpannal hobuserakmete küljest, jaluse katke ja isegi üks hobuse kammimiseks mõel dud rauast suga.

Mõned leiud lasid piiluda keskaegse inimese vaimsete huvide ja jõudeaja tegevuste ringi – leidude hulgas olid luust palvehelmes ja vilepill. Vilepill on täiesti “töökorras” ja asub Tallinna Linna muuseumi ekspositsioonis. Elanike ilumeelest andis tunnistust peenelt välja töötatud pronksist hobusekujuke – ilmselt lihtsalt iluasjake.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS AT THE SITE OF THE FINNISH EMBASSY

Peeter Talvar, Archaeologist, head of the excavationsIn connection with the reconstruction of the embassy building, archaeological excavations were carried out in the yard and cellars of Kohtu Street 4 during the winter and spring of 1995. The area in question, of great importance in the history of Tallinn, is the highest part of the Toompea hill and as such the most likely location for an ancient Estonian fortress.

The excavations undertaken in the area yielded unexpectedly rich results; the earliest evidence of human settlement at Toompea was found on the very site of the embassy. A round pit, 0.5 metres in diameter and about 50 centimetres deep, its bottom covered with fist-size cobblestones and obviously the base of an ancient fireplace or a cobblestone oven, had been dug into the sub soil in the eastern part of the yard. A radiocarbon analysis of a charcoal sample taken from the cavity indicated its age as dating from the second half of the 7th century to the end of the 8th century. This proves that at least one house heated by a cobblestone oven existed at Toompea at that time. Potsherds found in the cultural layer provide evidence of its dwellers’ daily activities. Although no remains of the ancient stronghold were preserved in the cultural layer, there is no doubt, based on an analysis of the ceramic finds, that a fortification, most probably timbered, existed here in the 11th century at the latest. Iron arrow tips and spearheads provide evidence of battles waged by Estonians, Danes, Germans and Russians for control of the hilltop fortress at Toompea. It would appear that the stronghold lacked permanent inhabitants and was used only in times of peril.

The remains of the seven wooden houses dating from the 13th-14th centuries (Danish period) were discovered in the area facing the embassy building’s main entrance. Only the lower logs of the walls, or in certain cases only the underlaying flagstones, remained. The foundations of cobblestone ovens were found in two buildings that had obviously been dwellings; the other structures, judging by the layer of manure surrounding them, were apparently sheds or stables.

Near these buildings the remains of a log-covered path and a stockade fence, the latter ap parently forming the boundary between two properties, were excavated. A branch of the log path, discovered at the southwestern basement of the embassy building, led downwards towards Tõnismäe hill.

In the pit at the Kohtu Street side of the embassy site, the remains of two dwellings dating from the end of the 13th century to the first half of the 14th centuries were excavated. The preserved walls of their cellars were made of limestone, with clay used as a mortar. Between the houses a gravel-surfaced road led southwards towards the edge of the limestone ridge and one of the towers, whose remains were unearthed during the course of the archaeological excavations, that formed part of the wall that encircled the Toompea castle. A selection of the archaeological ob jects yielded by the excavations is now on display in the basement of the medieval tower.

In the cellarage the excavations uncovered the basements of the houses apparently destroyed by the great fire of Toompea that took place on 6 June 1684; the site attained its present appearance in the mid-19th century.

The archaeological finds were primarily potsherds; several other daily artefacts, including iron knives, bone combs and needles, iron locks and door hinges were found. A large number of horseshoes, as well as fragments of bits and other harness-related items such as an iron buckle, a fragment of stimup and even an iron currycomb were also uncovered. Certain finds, such as the bone bead of a chaplet and a flute, reflected the spiritual interests and leisure activities of the medieval populace. The flute, entirely in working order, is now displayed at the City Museum of Tallinn.

A finely crafted bronze statuette of a horse, probably a decoration, attests to the dwellers’ advanced aesthetic sensibilities.

AADLIPALEE TOOMPEAL

Juhan Maiste, kunstiajaloo professorToompea, mis otsekui ripub mere ja vana hansalinna kohal, kerkib iga tallinlase ette võimsa ja ürgselt salapärasena. Võrreldes toimeka all-linnaga on elu ordu, piiskoppide ja aadli tsitadellis kulgenud sajandite pikku eri radu. Selle üheks ilmekamaks tunnismärgiks on aadlipaleed, mis veel täna kujundavad kauni ja kutsuva pärja ümber põlise Toomkiriku ja selle juurde suundu vate kitsaste tänavatel. Carl Ludwig Engeli poolt projekteeritud Kaulbarside perekonna kuue sambaga „Kreeka templi“ kõrval „Akropolise mäel“ on 1926. aastast Soome saatkonnale kuuluv kunagine Uexküllide palee üks Tallinna suuremaid ja esinduslikumaid. Selle arhitektuuristiil, olles küll kaugel hellenite Ateenast, kutsub esile assotsiatsioone Rooma või Firenzega. Kangas tub Alberti ja Serlio looming – palee Kohtu tänaval on kavandatud kui muistne maakodu linna lähistel. See on Rooma patriitside villa suburbana Itaalia kõrge ja sinine taevas oli unistus, mis 19. sajandil kogu Euroopas lummas nii põlis- kui ka vaimse aadli meeli. Dresdenis projekteeris Firenze palazzodest vaimustunult Gottfried Sem per. Peterburis lõikas loorbereid Iisaku katedraali ehitusel kuulsa prantslase Auguste Richard Montferrandi juures koolituse saanud Andrei Stackenschneider, mees, kes oli klassitsismi kõrval omandanud historistliku lähenemise ja teadmise arhitektist kui isikust, kelle käes oli valik otsus tada erinevate epohhide ja kultuuride vahel. Juba aastatel 1831–1835 kavandas Stackenschneider A. von Benckendorffile neogooti stiilis villa Tallinna lähistel Keila-Joal. Eesti arhitektuuris oli sellega juhatatud sisse uus ajastu.

Kulus veel kümmekond aastat. 1845. aastal alustati Toompea keskel, otse iidse Toomkiriku vas tas rüütelkonna uue maja ehitamist. Esialgu loodeti saada läbi kohalike arhitektide oskuste ja teadmistega. Kui neist aga puudus kippus tulema, otsiti abi Peterburist ning tõenäoliselt oli just Stackenschneider see, kes moodsa maitse eksperdina soovitas oma noort ja andekat abilist Georg Winterhalterit. Kui juba tutvus korra loodud, ei olnud midagi loomulikumat kui palgata sama mees 1848. aastal ehitustöid juhtima ka naaberkrundil. Uexküllide linnapalee arhitektuur võttis kokku nii ehitusisanda ambitsioonid kui ka arhitekti ülevaimad taotlused. Ehkki 1855. aastal tõusis Winterhalter akadeemiku seisusesse, ei leidu tema hilisemast Peterburi loomingust, millest lõviosa moodustavad tollase keskklassi üürimajad, Tallinna loomingule võrdset.

„Renessanssvillale“ Toompeal oli aga eelnenud pikk ja vaevaderohke ajalugu. Ikka ja jälle on siin vaheldunud poliitilised võimud ja ehitusisandad. Pea korra sajandis laastasid Toompead sõjad ja kahjutuli. Paiga varasem ajalugu ulatub tagasi rohkem kui aastatuhande taha. VII–VIII sajandi paiku (C-14 meetodil hinnangute põhjal ajavahemikus 670–890) asus klindi nõlvale paika, mida täna tunneme saatkonna majana, esmakordselt inimene, seadis end siin püsivalt sisse ja püstitas eluaseme. Toompea kunagisest asukast ja tema tegevusest jutustavad arheoloogide poolt 1995. aastal rohkem kui nelja meetri sügavuse kultuurikihi alt esile toodud koldeasemed, püstandaiad ja potikillud – kogu leiuaines, mille tähtsust Tallinna varasema ajaloo tundmaõppimisel on raske üle hinnata.

Aastal 1219 pöördus ajalugu. Pärast eestlastega peetud võidukat lahingut asus Toompeale Taani kuningas Waldemar II. Kroonik Läti Henriku järgi kiskusid taanlased maha vana linnuse ja hak kasid ehitama uut, mis nüüd hakkas kandma Castrum Danorum Revaliensise nime. Toompea piiskopikiriku juurest hargnevad tänavad lõppesid kaitsetornide juures. Üks neist tornidest leiti restaureerimistööde käigus Soome saatkonna krundilt.

1346. aastal vabastas Taani kuningas Waldemar IV Atterdag oma Eestimaa alamad talle antud ustavusvandest, müües kalliks ja tülikaks kujunenud provintsi 19 000 kölni hõbemarga (nelja tonni hõbeda) eest Saksa ordule, kes selle peagi pisukese vaheltkasuga Liivi ordule loovutas. Toompea põliselanike-vasallide elus muutis selline poliitiline otsus sisuliselt siiski vähe. Hansa linna kõrge viiluga kaupmeheelamu asemel valitsesid looduse poolt hästi kindlustatud Toompeal teised ehitustavad. Ennekõike sarnanesid siinsed rüütliõued mõisakeskustele. Taraga ümbritse tud hoovilt siirdus hommikuti luhale sööma kari.

Kuna aga elati rahutul piirialal, valmistuti pidevalt vaenlase rünnaku vastu. Aastatel 1454–1456 ehitati linna ehitusmeistri Hans Kotke juhtimisel valmis Lühikese jala väravatorn Thor am klei nen Domberge. Samal ajal rekonstrueeriti ulatuslikult ka tema vastas asuv väravatõke, mis nüüd nagu kaitsevöönd Pika jala torni kohal kujundas ühtse Toompead kindlustanud kindlussüsteemi. Tallinn oli võimas. Läbi kogu keskaja ei õnnestunud kellelgi seda vallutada. Linna saatuse mää rasid jõudude vahekorrad mujal ning muutused Euroopa poliitilisel kaardil. Aastal 1558 puhkes vanaks ja väetiks jäänud Liivi ordu pärandi pärast Liivi sõda. 1561. aastal alistus Tallinn tollastest vaenlastest kõige meelepärasemale – Rootsi kuningas Erik XIV-le. Esialgu valitses Toompeal pikkadest sõja-aastatest tingitud viletsus. Aadli asemel oli sinna elama asunud alamrahvas, kes oli hakanud sinna ehitama hütte, poode ja väikesi maju.

Aastal 1684 tabas Toompead üks tema ajaloo suuremaid õnnetusi. Külma ja pakaselise talve järel oli saabunud erakordselt kuum suvi. Kuuendal juunil puhkes tulekahju. Peagi nägi kogu barokk linn välja nagu tulemeri. Kokku hävis rohkem kui 200 kaunist aadlimaja. Vaid paar nädalat pä rast traagilist sündmust koostas fortifikatsiooniinsener Toompea kindlustamise hiigelkava: ette oli nähtud keskaegselt kõvera tänavatevõrgu ulatuslik laiendamine, kruntide ümberplaneerimine ja kaheksa võimsa suurtükitorni ehitus, millest üks oleks asunud just meid huvitaval alal.

Paraku sattus maa enne nende plaanide teostumist taaskord sõjakeerisesse. Aastal 1700 puh kenud Põhjasõjas raius tõusva Venemaa noor ja hakkaja tsaar Eesti kaudu akna Euroopasse. Toompeale asus uus võim. Esialgu oli olukord muidugi raske. Seda nii maal kui linnas. Ajaloo ürikutest teame koguni juhuseid, kus aadel oli sunnitud elamiseks kasutama ilma korstnata suitsu täis rehetuba.

Suuremad muutused said alguse alles 19. sajandil, mil esialgu poole, seejärel kogu praeguse saat konna krundi ostsid Eestimaa ühte vanemasse ja auväärsemasse aadlisuguvõssa kuulunud Vigala tohutu majoraatmõisa omanikud Uexküllid. Uute omanike ümber oleks nagu lehvinud mingi eriline pärimuste, edu ja vaimsuse oreool. Perekonna maja väljaehitaja Bernhard Otto Jacob von Uexküll (1819–1884) oli koos paljude hilisemate Vene riigitegelastega alustanud õpinguid Tsarskoje Selo lütseumis, jätkanud filosoofiastuudiumit Berliinis, reisinud hiljem Prantsusmaal, Inglismaal ja Itaalias. Oma Läänemaa mõisates laskis ta ehitada maju ja rajada inglise stiilis parke. Tema oli ka see mees, kes perekonna Toompea valdustes kavandas vanema barokkstiilis maja kõrvale uue ajakohase villa.

Paraku, nagu suurte ideede puhul ikka, ei kulgenud mitte kõik valutult. Aadlielamuid Toompea klindiserval arvati veel ikka teenivat riigikaitse huve. Insenerikomando poolt 1849. aastal koos tatud raportis paluti keskvõimul ehitustööd koguni peatada. 1851. aastal sai uus hoone siiski val mis. Arhitektuurivallas oli astutud otsustav samm moodsa stiili ja uue esteetilise mõtte suunas. Kui hoone välisarhitektuur tõi tollasesse linna ajastu romantilise vaimu, siis siseruumides valitses ajalooliste eeskujude range diktaat. Ühtäkki meenuvad Rooma paleed ja teatrid – kogu Rooma keisrite aegne pompöösne ja pidulik luksus. Aeg oli valla assotsiatsioonidele. Antiigi vägevuse kõrval otsiti kontakti kaasaja ja vararomantismi vaimus koha maagia ning ajalooga. Läbi kesksete ovaalsaalide ümarkaarsete akende paistab ära Niguliste kiriku torn. Oleme palees, kus iga ruum tõusis esile omaette, kujundades ühtekokku ometi terviku, milles arhitekti dirigeerimisoskus on suutnud ehituskunsti üksikosad panna kõlama Beethoveni või siis Schuberti voolavas taktis, kõigi sellele omaste võimsate tõusude ja mõõnadega.

Majja on ikka ja alati tuldud ülevate tunnetega. 1922. aastal ostis Uexküllide hiigelkrundi Kons tantin Päts, iseseisva Eesti esimene riigivanem ja üks Eesti olulisemaid poliitikategelasi tänaseni. Päts laskis hoonestuse stiilselt ennistada. Alates 1926. aastast kuulub valdus Soome saatkonnale, kes on maja ulatusliku restaureerimisega korvanud kuhjaga oma vahepealse rohkem kui poole sajandi pikkuse eemaloleku. Ruumides on tunda püüdlikkuse ja ammendamatu energia innus tavat jõudu.

THE TOOMPEA MANOR

Juhan Maiste, Professor of Art HistoryLike a curtain hanging between the sea and the upper reaches of the old Hansa city, Toompea looms before the citizens of Tallinn as a majestic source of power and mystical strength. Com pared to the busy Lower Town, life in this stronghold of knights, bishops, and feudal lords has proceeded at an entirely different pace for centuries. The clearest proof of this is offered by the Toompea manors that even today form a beautiful and attractive architectonic wreath surround ing the ancient Dome Church and the narrow streets leading to it. One of the most grandiose and representative mansions, sited near a six-columned “Greek Temple” designed for the Kaulbars family by Carl Ludwig Engel to overlook its “Acropolis”, is the former Uexküll palace that has served as the embassy of Finland since 1926. Although the design has drawn its inspiration from Hellenic Athens, the architecture of Rome and Florence comes more readily to mind, and the works of Alberti and Serlio rise before one’s eyes. The palace facing Kohtu Street recalls ancient country houses built outside a city – the suburban villa of a Roman patriarch.

During the 1800s throughout Europe, Italy’s lofty blue sky was a dream that enchanted ordi nary citizens as well as the nobility. Florentine palaces provided the inspiration for Gottfried Semper in Dresden. In St. Petersburg, they secured a reputation for Andrei Stackenschneider, an architect who had learned his craft on the St. Isaac’s Cathedral building site in St. Petersburg under the direction of the famous Frenchman Auguste Ricard Montferrand. Besides absorbing Classicism, he had also embraced a historicised image and role model that granted architects the authority to freely select motifs from different cultures and historical periods. As early as 1831–1835, Stackenschneider had designed a Neo-Gothic style villa for A. von Benckendorff at Keila-Joa near Tallinn. In the architectural history of Estonia, this was the “opening kick-off” to a new age.

In 1845, construction began in the centre of Toompea, opposite the ancient Dome Church, for a new House of the Nobility. Initially, it was believed that the project could be undertaken using the skill and artistry of local architects, but when these proved insufficient, help was sought from St. Petersburg. It is likely that Andrei Stackenschneider himself recommended his talented young assistant Georg Winterhalter for the task. After the acquaintance had been formed, it seemed only natural to hire the same architect to direct building activities on the neighbouring site in 1848. There the architecture of Winterhalter’s Uexküll urban palace seemed to express the highest ideals of its client, user, and architect. Although Winterhalter became a member of the Academy in 1855, none of his later work in St. Petersburg, essentially flats for the middle class, ever measured up to what he had accomplished in Tallinn.

The building of Toompea’s “Renaissance Manor” was however preceded by a long and troubled history. Landowners and rulers changed continuously. Toompea was usually swept by destruc tive wars and fires at least once every hundred years.

The previous history of the Toompea area stretches back over a thousand years. Sometime be tween the 7th and 8th centuries, the limestone hill area we know today as the site of the Finnish embassy witnessed its first permanent human settlements. What we know about Toompea’s ear liest inhabitants and their ways is largely the result of archaeological discoveries made in 1995. Digging down through more than four metres of cultural stratification, researchers uncovered the remains of fireplaces, fences, and pottery fragments.

It is difficult to overestimate the significance of this discovery to scientific studies of Tallinn’s earliest inhabitants.

In 1219, history changed course. After defeating the Estonians, the Danish king Waldemar II installed himself on the Toompea hill. According to chronicler Henricus de Lettis, the Danes demolished the earlier fortifications and began to build a new set that went under the name Castrum Danorum Revalensis.

In 1346, the Danish king Waldemar IV Atterdag freed his Estonian subjects from the oath of allegiance they had sworn to him and sold what had turned out to be an expensive and difficul ty-managed province for 19.000 Cologne silver marks (four tonnes of silver to a German Order of Knighthood, who in turn sold it at a small profit to the Livonian Order of Knighthood). These political decisions had little discernible effect on the daily lives of Toompea’s permanent residents and feudal lords. In contrast to the high-walled houses of the Hansa city’s merchants, the natural protection offered by the Toompea hill led to a different pattern of building. The hill’s “castle yards” bore a greater resemblance to countryside estates: Livestock kept in fenced yards were let out in the morning to graze at Tõnismägi.

The city’s restless border location however created a situation in which preparations to repel enemy attacks had to be made year after year. Under the direction of master builder Hans Kotke, the Lühike Jalg gate tower was built between 1454–1456. At the same time, a gate fortification was rebuilt forming a defense zone with the Pikk Jalg tower, and the result was Toompea’s first unified fortification system. Tallinn was extraordinary. All through the entire Middle Ages no one was able to really conquer it physically; the city’s fate was more likely to be affected by the relative strengths of nations elsewhere, as well as by changes on the European political map. In 1558 The Livonian War broke out, essentially a fight over the estate of the Livonian Order of Knighthood, now aged and powerless. In 1561, Tallinn surrendered to one of its more congenial enemies from those times, the Swedish King Erik XIV.

As a result of the war, Toompea experienced hardship for many years. The hill’s aristocrats were replaced by poorer citizens who built huts and small houses.

In 1684, Toompea experienced one of the most horrific catastrophes ever to befall the area. An unusually hot summer followed a cold and freezing winter. On the sixth day of June, a fire ac cidentally broke out. Soon the entire Baroque-style city was enveloped by a wall of flame. Over 200 beautiful mansions were destroyed. A few weeks after the tragedy, a fortifications engineer was already preparing grandiose plans for the rebuilding and fortification of Toompea that en tailed a large-scale widening of the medieval street network, a rezoning of lots, and the erection of eight imposing guard towers, one of which would have been built in the area now occupied by the embassy.

Unfortunately, the country was again caught up in the throes of war before the rebuilding plan could be fully implemented. During The Northern War (1700–1721), a young and energetic Rus sian czar battered his way through Estonia to gain a window facing on Europe. A new ruler had once again arrived at Toompea. At first, the hardships faced by citizens were as pervasive in the countryside as they were in the city. Historical accounts tell of landowners who were forced to

live amid smoke and soot in drying barns without chimneys. It was not until the age of Enlight enment that any significant progress took place.

Major changes began to occur only during the 1800’s, when the site was bought by the von Uexküll family, owners of the vast Vigala country estate and one of Estonia’s oldest and most respected aristocratic families. The new owners brought with them a unique aura of tradition, spirituality and success. The builder of the family mansion, Bernhard Otto Jacob von Uexküll (1819–1884), who was later affiliated with numerous Russian diplomats, began his education at the Tsarskoye Selo lyceum, continued his philosophical studies in Berlin and later travelled extensively in France, England, and Italy. At his country estate in western Estonia, von Uexküll built houses, cleared land for parks in the English style, and designed the family’s new, up-todate mansion on the Toompea property next to the old Baroque-style house.

As is often unfortunately the case with grand ideas, everything did not proceed without effort. The opinion of the military was that the manor houses on the crest of the Toompea hill should also serve national defence needs. A military engineer’s report prepared in 1849 even went so far as to request that the central government stop all building works, but the suggestion was ignored and the new building was completed in 1851. Estonian architecture had taken a decisive step forward towards a modern style and new aesthetic thinking.

The exterior architectural character of the building recalls the romantic spirit of earlier urban cityscapes, whereas the interiors are governed by an uncompromising adherence to classical precedents. The entire Caesarean pomposity and festive luxury of Roman palaces and theatres easily come to mind. The time was ripe for various historical associations: along with the mag nificence of Antiquity, there came a yearning for the spirit of early Romanticism, with its affinity for the magic and tradition of a place. A dramatic view of the Niguliste church tower is framed by the windows of the round central hall; we are in a palace in which every room proclaims its individuality. The result, however, is a unified whole in which the architect’s skill as a conductor has enabled him to co-ordinate the tempo and flow of the building’s individual architectural elements like the movements within a well-written symphony by Beethoven or Schubert.

The building has always aroused strong emotions. In 1922, the von Uexküll family’s sizeable site was purchased by Konstantin Päts, independent Estonia’s first statesman and one of the country’s most prestigious politicians. Päts restored the building with a firm sense of style. Since 1926 the property has housed the Finnish Embassy, which has compensated for its almost half century of absence by realising a financially generous and architecturally extensive renovation. The newly renewed spaces project an atmosphere of enterprise, boundless energy, and inspira tional power.

PROJEKTEERIMINE

Simo Paavilainen, arhitekt SAFA, Arkkitehtuuritoimisto Käpy ja Simo Paavilainen

AJALUGU

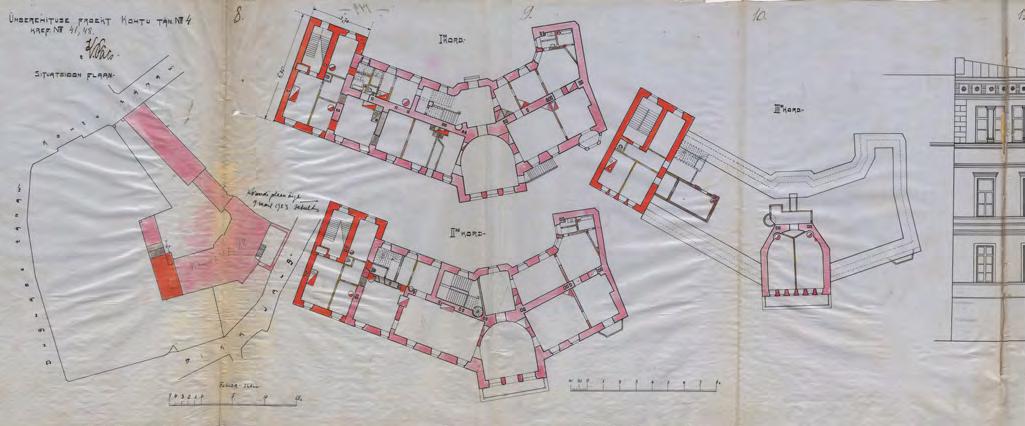

Soome Tallinna suursaatkond paikneb väikesel, aga seda väärtuslikumal krundil Toompea mãel ja nõlval nii, et õuede kõrgusevahe on umbes 10 meetrit. Kõrvalkruntide pitsituses oleva ülaõue kitsus johtub sellest, et see oli algselt kaitsetorni Toomkiriku väljakuga ühendav tänav. Suur saatkonna hooned on keskaegsed ja eri etappidel ehitatud. Praegu linnapildis näha olevad majad esindavad peamiselt kahte eri ajaperioodi ja kolme erinevat ehitusstiili. Kohtu tänavalt algav ja hoovi piirav kantselei hoone on ehitatud peaasjalikult 18. sajandil. Ehitise barokseid jooni rõ hutavad veelgi mansardkatus ja riigivanem Pätsi poolt 1920. aastate algul ehitada lastud Kohtu tänava poolne erker, mistõttu kinnistu hakkas meenutama 18. sajandi maamõisat. Nii residents kui ka konsulaat on 19. sajandi keskpaigast, kuid esindavad sellest hoolimata erinevaid stiile. Residents on varane näide nn. itaalia uusrenessanssist, konsulaat aga esindab inglise uusgootikat. Stiilinõudmistele vastavalt on residents krohvitud, konsulaat aga paekivist.

PÕHIPRINTSIIBID

Toompea on väga väärtuslik ajalooline territoorium. Seda ei ole peetud kohaks, kus võiks silma hakkaval moel uut arhitektuuri eksponeerida. Seepärast üritati maja uute funktsioonide ja uue tehnika poolt dikteeritud lahendused sobitada olemasolevasse raami nii, et tulemuseks oleks ta sakaalustatud tervik. Ehitiste uusosad ja lisad pidid igal juhul tahaplaanile jääma. Kõik uus teos tati modernses vormikeeles, mis on märgatav alles täpsemal vaatlemisel. Vana arhitektuuri igat detaili ja profiili käsitleti omaette tervikuna, kusjuures eesmärgiks oli selle arhitektuuri demonst reerimine kogu tema suurejoonelisuses. Hoones esinevaid nn ebareeglipärasusi ja „kapriise“ ei üritatud parandada. Projekteerijad olid veendunud, et ehitise esteetilised väärtused pääsevad kõige paremini maksvusele juhul, kui järgitakse tema rajamisperioodi algupäraseid lahendusi. Mõnel juhul – näiteks residentsi põrandate ja uksekäepidemete osas – otsiti abi vastas olevast Rüütelkonna hoonest, mille on samuti projekteerinud Georg Winterhalter.

Residentsi välises värvilahenduses taotleti samasugust 1920. aastate fotodelt tuttavat heledust, mis iseloomustas hoonet Soome omandiks siirdumise ajal. Kantselei värvitoon tuli välja vanade krohvikihtide alt. Kõik interjööri värvilahendused põhinevad kohapeal tehtud uuringutele. Mit mest varasemast värvikihist valiti arhitektuurilise üldilme ja tervikuga kokkusobiv.

Nii 18. sajandile kui ka 19. sajandi uusrenessansile on omane ehtsate materjalide vältimine: need asendati imitatsiooniga. Vastavalt sellele värviti metallpinnad remondi käigus metallivärviga, tavalistele puupindadele aga katsuti anda väärispuu välimus.

Konstrukisioonide osas püüti majad säilitada oma endisel kujul. Vahelaed on ka nüüd puust, ehk ki suur osa põrandataladest tuli kas osaliselt või täiesti välja vahetada. Kõik katusekatted, laed, välis- ja siseseinte krohv, samuti põrandad on täiesti uued. Ainukese erandi moodustab residentsi alumise fuajee vana kahhelpõrand. Residentsi paraadtrepp ja mõned kõrvaltrepid välja arvatud, tehti kõik muud trepid uuesti kas siis tuleohutuse nõuete tõttu või kasutuse käepärastamiseks. Radiaatorkütte ja ventilatsiooni ehitamisel kasutati ripplagesid ainult kõrvalruumides. Kõik ka minad ja ilusamad ahjud säilitati ja suurem osa neist ka remonditi kasutuskõlblikuks.

Suursaatkonna polüfunktsionaalne tegevus sobitus üllatavalt kergelt vanasse kinnistusse. En dine ruumijaotus oli võimalik säilitada peaaegu täies ulatuses. Residentsi ehitati lift ja üks uus trepp tagamaks ühendust köögi, pööningu ja keldri vahel.

KANTSELEI

Kantseleid iseloomustavad peente profiilidega aknad, ilusad korrastatud uksed ja kogu suursaat konna kõige elegantsemad stukklaed. Interjööris rõhutati hoone 18. sajandi atmosfääri selles kunagi kasutusel olnud pastelltoonidega. Majas on laudpõrandad samal ajal kui mujal on parkett.

RESIDENTS

Residentsi ruumid on suuremad ja pidulikumad kui kantselei omad. Seinad värviti siin uusre nessansile tüüpiliste raskete värvidega. Paraadkorruse kolme ruumi – söögisaali, sinise salongi ja raamatukogu – seinu ehivad endiste tapeetide järgi siiditrükis teostatud tapeedid. Residentsi kõige suurem väärtus on peitsitud saarepuust uksed, mida kaunistavad voluudid ja muu dekoor. Esindusruumide juurde kuulub suurepärane modernne köök.

Residentsiga on ühendatud suursaadiku kolmel korrusel asuv korter. 1920. aastate algul valmi nud ehitises on olnud mitmeid kortereid. Hoone kõledat trepikoda katsuti soojade värvitoonide ja puutrepiga hubasemaks muuta. Korteri, aga ka suursaadiku kabineti juurde kuulub väike aed. Residentsi paekivist võlvitud keldrisse rajati saun ja köögi laoruumid. Eesmärgiks oli paekivi rolli rõhutamine. Kaminatoast leiti kahe varasema trepi osad, mida võib näha põranda klaaskaane all. Saatkonna teine ajalooline vaatamisväärsus on kaitsemüüri nurgatorn, mis tuli välja konsulaadi arhiivi jaoks süvendit kaevates. Selleks, et arhiivi pääseda, tuli ehitada trepp ja sild väärtusliku torni ületamiseks.

KONSULAAT

Konsulaat on suursaatkonnaga ühenduses vaid ühe ukse kaudu. Tegelik sissekäik on Pika jala uusgooti stiilis trepi kaudu. Müüri taga on klaaskatusega kaetud ja pinkidega varustatud hoov klientidele. Kolmel eri korrusel paiknevad konsulaadiruumid on ühendatud keerdtrepiga. Trepi käsipuu balustersambad pärinevad algupärasest trepist, ehkki trepp ise on suuremalt jaolt uuesti tehtud. Konsulaadis rõõmustavad silma uusgooti stiilis uksed ja Tudor -aknad.

SISUSTUS

Suursaatkonna sisustus on täiesti modernne. Selle erinevad detailid on kõigis kolmes majas üsna ühtemoodi. Hoonete eripära rõhutati eelkõige värvidega, erinevate puuliikide ja mööbliriidega. Kantseleis kasutati pööki, residentsis saarepuud ja konsulaadis kaske. Niinimetatud antiikmööb lit on üksnes residentsis ja suursaadiku kabinetis. Tapetseeritud ja värvitud seintega tubade eri nevusi katsuti mahendada sel teel, et tapeediga tubadesse paigutati modernne mööbel ja värvitud tubadesse antiikmööbel. See põhimõte ei ole realiseerunud söögisaalis. Õnneliku juhuse tõttu oli võimalik residentsi kolme ruumi – peatrepikotta, ümarsalongi ja söögisaali – tagasi tuua omal ajal saatkonnast Soome evakueeritud kroonlühtrid. Residentsi keskseim ruum – ümarsalong – on sisustatud Eliel Saarineni mööbliga otsekui meenutamaks meile, milline oli Saarineni mōju 20. sajandi alguse Tallinnale.

EHITUSKULTUUR

Ehitustööde käigus üllatas eesti ehituskultuuri erinevus soome vastava kultuuriga võrreldes. Eestis on paekivi kõige tavalisem ehitusmaterjal. Soomes on seda kasutatud vaid väärtuslike põrandate ja fassaadikaunistuste tegemiseks. Johtuvalt paekivi tavalisusest Eestis ja selle väärtus tamisest Soomes, on paekivi kasutatud rohkesti suursaatkonna uute põrandate, treppide ja lettide tegemisel. Teine näide keskeuroopalikust kultuurist on võretatud tagasein kantselei kolmandal korrusel. See eksponeeriti remondi käigus.

ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

Simo Paavilainen, Architect SAFA, Architects’ Office Käpy and Simo PaavilainenHISTORY

The Finnish Embassy in Tallinn occupies a confined but valuable site on the crest and slope of the Toompea hill such that the elevation difference between upper and lower courtyards is about 10 metres. The extreme narrowness of the upper yard, squeezed between neighbouring sites, is explained by the fact that it was originally a street that connected the fortification wall tower with the Cathedral Square.

The embassy’s structures have their roots in the Middle Ages and were built in many phases. The structures visible in today’s urban cityscape essentially represent two historical periods, even though three building styles are in evidence. The chancery structure that begins at Kohtu Street and encloses the courtyard was built primarily during the 1700s. Its Baroque-style qualities were accentuated by the mansard roof and bay window added in the early 1920s by Konstantin Päts. These additions very nearly provide the building with the character of a 1700s country manor house. Both the residence, an early example of the so-called Italian Neo-Renaissance style and the consulate, representing the English Neo-Gothic style, date from the mid-1800s. Like its stylistic ideal, the residence is a stucco-surfaced structure, whereas the consulate’s limestone construction has been left unplastered.

DESIGN PRINCIPLES

Toompea is such a valuable historical area that it was not considered a suitable location for a display of modern architectural pyrotechnics. Solutions required by modern functions and tech nologles have been integrated with the existing framework to achieve a balanced overall result. New parts and additions, almost undetectable at first, have been realised using a modern form language that reveals itself after closer inspection. Every existing architectural detail has either been reproduced or restored. Each building has been treated as a separate entity to allow its ar chitectural quality to shine on its own terms, but no attempt has been made to resolve the archi tectural inconsistencies and “whims” found throughout the complex. Planning has proceeded from the assumption that each building’s aesthetic values are more successfully expressed by respecting the design integrity of each historical period. In certain cases, such as the residence’s floors and door handles, help with stylistic precedents has been sought from the House of the Nobility situated across the street, as well as from the work of architect Georg Winterhalter, designer of the residence.

The exterior colour of the residence has been restored to the shade, as revealed in historical pho tographs, that the building possessed in the 1920s at the time it was acquired by the Finnish gov ernment. The colour shade selected for the chancery has been found under facade stucco layers.

All interior colour schemes are based on investigations carried out on the site. Colour shades, usually from earlier periods, have been selected from numerous layers according to how well they blend with the overall architectural character.

During the 1700s and the Neo-Renaissance style of the 1800s simulated materials were widely used in building. In that spirit, metal surfaces have in many cases been treated with metallic paint to imitate gold and bronze, and wood surfaces have been painted to resemble oak or ash.

Structurally, the buildings have been preserved in their existing forms. Intermediate floors are still wood construction even though many floor joists had to be partially or completely replaced. By contrast, all roofs, interior ceilings, exterior and interior plastering, and flooring surfaces have been rebuilt, the sole exception being the existing ceramic tiled floor at the residence’s entrance hall. Stairs, except for the residence’s main staircase and two minor secondary stairs, have been renewed to improve fire safety and convenience of use. The use of radiator heating and a displac ing air conditioning system has meant that suspended ceilings were required in secondary spaces only. All fireplaces, as well as the more attractive heating stoves, have been preserved, and many have been restored to operating condition.

Inserting the complex spatial functions of a modern embassy into such a historical setting was sur prisingly easy, enabling the existing spatial arrangement to remain essentially intact. A new lift was added to the residence, as well as a service stair linking the building’s kitchen, attic, and basement.

CHANCERY

The Chancery building features gracefully profiled windows, beautifully restored doors, and the embassy’s finest stucco ceilings. The 1700s character of the building has been emphasised by its pastel interior colours, all of which are based on earlier paint layer shades discovered on the site. Board flooring provides contrast to the parquet employed in other structures.

RESIDENCE

Spaces in the residence building are larger and more festive character than those found in the chancery building. Room walls have been painted in the heavy colours characteristic of the Neo-Renaissance style. Working from samples found on the site wallpaper surfaces in the re ception floor’s dining hall, blue salon, and library have been restored to match their original character using silk-screen printing techniques. Among the residence’s most handsome features are the stained ash doors, with their decorative volutes and frames. An attractive yet modern kitchen serves the reception halls.

The Residence is connected to the ambassador’s living quarters that occupy three levels. Con structed in the early 1920’s, the building has at times contained numerous flats. The formerly dreary staircase has been given a cosier atmosphere with warm colour shades and wood-surfaced stair treads. The dwelling, as well as the ambassador’s office, are connected to their own private gardens.

The residence building’s limestone-vaulted basement spaces have been renovated to accommo date a sauna suite and kitchen storerooms; emphasising the limestone’s appearance has been the architectonic intent. The remains of two earlier stairs may be seen under glass floor hatches in the vaulted sauna lounge. The embassy’s second historical vestige of former times is the fortifica tion wall’s corner tower, unearthed when the consulate’s archive spaces were excavated. To gain access to the archives, a new stair and walkway were built to bridge the historically important tower.

CONSULATE

The consulate is linked to the embassy through a single door. The building is entered through the Neo-Gothic gate on the Pikk Jalg 14 street side, and a glass-roofed waiting area with benches has been designed in the courtyard behind the wall. The consulate’s spaces, distributed over three floors, are connected by a single spiral staircase. Staircase balusters are original even though the staircase was almost completely rebuilt. Other sources of architectural delight in the consulate include its Neo-Gothic-style doors and Tudor-style windows.

INTERIORS

The detailing of the embassy’s modern-style interiors has been consistently implemented throughout all three buildings. The varying character of the buildings has been expressed pri marily by colours, wood species, and fabric coverings. Consistent with each building’s tradition, beech has been used in the chancery, ash wood in the residence, and birch in the consulate.

So-called “antique” furnishings have been employed only in the residence and the ambassador’s office. The differences between painted and wallpapered rooms have been softened by placing contemporary furniture in wallpapered rooms and antique furniture in painted rooms. The main staircase, round salon, and the dining hall were refitted with their original chandeliers, discov ered by a fortunate stroke of luck in Helsinki years after the embassy’s war time evacuation. The round salon, the residence’s central space, has been fitted with furniture designed by Eliel Saarinen in memory of his influence on Tallinn’s architecture and urban planning during the early 1900s.

BUILDING TRADITIONS

During the construction period, surprising differences between Estonian and Finnish building traditions became apparent. Limestone is an extremely common building material in Estonia, whereas in Finland it has been used only for facade decorations and floors at important locations. As a result of its abundance in Estonia and the symbolic value attached to it in Finland, lime stone has been used extensively for the embassy’s new floors, staircases, and reception counters. Another example of Central European building culture is the timber wall truss, left exposed in conjunction with renovation works, that is to be found on the chancery’s third floor.

PROJEKTEERIMISTÖÖD

Asko Rahikka, insener, Insinööritoimisto Asko Rahikka OyEHITUSUURINGUD JA ESIALGSED KAITSEMEETMED

Juba esmapilgul oli selge, et osal pea kümneks aastaks täiesti hooldamata jäetud majadest olid puust vahelaed nii pehkinud, et neid pidi varingu vältimiseks toestama. Ka läbijooksvatele plek kkatustele tehti hädaremont ja pidevate veekahjustuste ärahoidmiseks suleti katkised aknad. Visuaalse vaatluse põhjal ning avades mõningaid vahelagede kõige tõenäolisemaid läbilaskekoh ti koostati uurimisprogramm selgitamaks projekteerimise tarvis konstruktsioonide seisundit. Nagu vanade ehitiste puhul tihti, selgus ka siin ehitustööde käigus, et täpsema eelprojekti tege mine oleks nõudnud märgatavalt laiemaid uuringuid, millised hiljem ka läbi viidi. See aga tingis ehitustööde käigus tehtud uuringute suure mahu. Viimast asjaolu on sedasorti objektide puhul üldiselt raske vältida, kuna täieliku pildi saamine konstruktsioonidest ja nende seisukorrast eel daks praktiliselt kogu maja lammutamist.

VANAD KARKASSIKONSTRUKTSIOONID JA NENDE KAHJUSTUSED

Ehituskompleks koosneb viiest 1–3-kordsest eri aegadel ehitatud hoonest, millele on tehtud aas tate jooksul mitmeid lisasid. Kõikide hoonete välisseinad ja ka osa kandvatest siseseintest on laotud paekivist. Samuti on paekiviplaatidega kaetud keldrite põrandad. Keldrite laed kujutavad endast massiivsetest paekiviplaatidest tehtud silinder- ja ristvõlve. Rasked vahe- ja katuslaed on võimsatest aampalkidest ehitatud ning täidetud saepuru ja segatäitega. Katusekonstruktsioonid on puust, katus kaetud plekiga.

VUNDAMENTKrundi aluspind kujutab endast vana, eriti tihedat paeklinti. Hooned on ehitatud osaliselt klin dile, osalt selle peale tekkinud moreenikihile või siis omal ajal aastasadu tagasi tehtud kivimüüri tisele. Mõned hooned on rajatud ka suurtest paekividest laotud kaitsemüüri peale. Tegelikke vundamendivigastusi esines vaid kahes kohas. Mõlemal juhul leiti vundamendi alt pehme lokaalne savikiht, osaliselt isegi vanu, hästi säilinud puitreste. Veeleke oli siiski põhjusta nud konstruktsioonide väikseid vajumeid. Kuna keldriruumi laiendati, tuli vana keldri põrandat alla lasta ja vundamenti süvendada. Nende tööde käigus parandati ka mainitud vundamendi kahjustused.

SEINAD

Välisseinad ja mõned kandvatest siseseintest olid lubimördiga laotud 0,6–1,2 meetri paksused paekiviseinad. Osa kandvatest vaheseintest olid püstpalkseinad või püstplankseinad, mis üldju hul sellistena ka säilitati. Seinte seisukord nimelt oli küllalt hea, ehkki aastasadade jooksul tehtud muudatused avades ning puust ukse- ja aknatalad olid tekitanud neisse rohkesti suuremaid ja väiksemaid pragusid. Praod parandati injekteerimise teel.

VAHELAED

Enamalt jaolt koosnesid vahelaed massiivsetest puittaladest, mille all oli mh laelaudis ja tradit siooniline puitpeergudele tehtud krohv. Mitmes kohas olid peergude asemel õlgmatid. Aampal kide peal oli põrandatalastik, selle peal 30–40 millimeetri plankpõrand ja põranda kattematerjal. Täitena oli enamasti kasutatud ehitusprahti või mingit muud rasket materjali. Vahelae paksus oli keskmiselt 420 millimeetrit.

Juba ehitusuuringute käigus selgus, et vahelaed olid paiguti üsna pehkinud, osaliselt isegi nii, et need oli vaja maha lõhkuda. Suurem osa kahjustustest olid siiski sellised, et pärast nende eemal damist vastas puutalade kandevõime veel nõudmistele. Raske täitematerjal asendati ehitustööde käigus kergema mineraalvatiga. Eemaldatud aampalgid korvati liimpuidust kandjatega. Halvas seisukorras olevate paekiviseinte toestamiseks ja sidumiseks asendati puitvahelaed mõnes kohas terasbetoonplaadiga.

KATUSLAED JA KATUSEKATE

Välja arvatud kaks terasbetoonist trepikoja katust olid kõik katuslaed puust. Kantseleihoone katuslagi ja katusekate olid hoolduse puudusel nii halvas seisukorras, et need oli vaja koguni välja vahetada. Samasugust väljavahetamistööd oli vaja teha mujalgi, eriti lõunapoolse välisseina teatud elementide osas. Üldiselt tehti katuslagede remont sama moodi nagu vahelagedel. Katuse katte plekk oli eriti halvas seisukorras ja see vahetati kogu objektil välja.

UUED KONSTRUKTSIOONID

Nagu juba varem märgitud, tuli osa vanadest konstruktsioonidest välja vahetada. Uutena ehitati välja pööninguruumid, kuhu paigutati kolm ventilatsioonikambrit ja osa suursaadiku eraruumi dest.

TREPID

Ehitises oli algselt seitse üksteisest täiesti erinevat ja eri kujuga teras-, kivi-, betoon- ja puutreppi. Nendest säilitati pärast mõõdukat remonti vaid kolm. Ülejäänud neli ehitati terasest ja betoonist.

ÕLIMAHUTI JA TORUSTIKUKANAL

Krundi ülaõue paigaldati energiavarustuse tagamiseks kaks õlimahutit, mis asetati õue alla vee kindlatesse terasbetoonkünadesse. Kuna kõik hooned koos moodustavad omamoodi pika ahela, on toru-, kaabli jms ühendusi rohkesti. Seetõttu ei olnud neid võimalik mahutada muuks kasu tuseks mõeldud kitsastesse keldriruumidesse. Ülaõue hoonete välisseinte vundamendi kõrvale ehitati õlimahutiga ühendatud ligi 60 meetri pikkune torustikukanal, mis juhiti residentsi alt umbes 10 meetri sügavusele keldrisse.

LIFT

Saatkonda ei pidanud algselt lifti tulema. Siis, kui ehitustööd olid juba kaunis kaugel, otsustas töö tellija, et lifti on siiski vaja. Selle karkass tehti 150 x 150 x 8 millimeetri terastoruprofiilidest, mis täideti raudbetooniga ja ühendati nii üksteise kui ka välisseinaga A 60 tulekaitseklassi kuuluvate terasprofiilidega. Seal nad laoti silikaattellistest poolkiviseinana. Liftišahti poolt läbi lõigatud vahelagede puuosad toetati šahti teraskonstruktsioonidele. Terassambad omakorda toetuvad alu mise torušahti raudbetoonist seinakonstruktsioonidele.

STRUCTURAL DESIGN

Asko Rahikka, Engineer, M.Sc., Engineering Office Asko Rahikka OySTRUCTURAL INVESTIGATIONS AND PROTECTIVE MEASURES

The first preliminary visual inspections immediately revealed that sections of wooden floor con struction in buildings left untended for ten years were so deteriorated that special bracing was required to prevent their imminent collapse. Emergency repairs were also carried out on the leaking metal roof, and broken windows were sealed to prevent rainwater from further entering the building.

A structural investigation programme was prepared, based on visual inspections and the open ing of damaged floor areas, to assess the building’s foundation conditions and structural sound ness for purposes of renovation planning.

During the building period it however became apparent that, as is often the case with older structures, the preparation of a more precise preliminary design would have required a far more elaborate investigation. As a result, a great deal of survey and planning work took place during the construction period itself.

EXISTING STRUCTURAL MEMBERS AND DAMAGE

The embassy complex is composed of five 1–3 storey buildings built during different historical periods in which additions and alterations have been carried out over a period spanning hun dreds of years. All exterior walls, as well as sections of interior bearing walls, have been con structed using laid-up limestone masonry. Basement floors are generally earthen floors, and use spaces have been paved with limestone. Basement ceilings are massive cross vaults and barrel vaults built with limestone masonry. Intermediate floors, as well as the roof, have been built us ing massive timber beam construction packed with sawdust. All buildings are now metal-roofed.

FOUNDATIONS

The site is set upon an extremely dense layer of limestone bedrock. Certain buildings have been founded directly on this rock, while others have been placed upon a compact moraine layer or centuries-old rock fill. Other structures stand on the remains of ancient defensive fortification walls built with large limestone rocks. Serious foundation damage was detected only in two areas where a soft local clay layer was found under foundations. In one case, water seepage under a reasonably well preserved timber foundation had caused minor settling. Because a great deal of new basement space was created, existing basement floors were lowered and foundations were extended. The two cases of foundation damage previously mentioned were repaired in conjunction with these works.

WALLS

Exterior walls and certain interior bearing walls, varying in thickness between 0.6–1.2 m, are masonry walls laid up with limestone and limestone mortar. Certain load-bearing interior walls, constructed using vertical logs or vertical planks, were usually left intact. The condition of walls was generally satisfactory, but changes made over the centuries to window openings, as well as the additions of window and door lintels, have led to cracks in walls that were filled using an injected mixture of epoxy resin and cement mortar.

FLOOR CONSTRUCTION

Floor construction generally consists of massive wooden beams, to the undersides of which were attached bulkhead panelling and traditional plastering over wood lath. In several locations straw mats were used in place of wood. Main beams generally supported log timber framing covered with 30–40 mm thick planking and the floor’s surfacing material. Sawdust and other heavy ma terials were generally used as fill. The average overall thickness of intermediate floors is 420 mm.

Where floors had become deteriorated beyond repair, they were completely dismantled and re placed. In most cases, the carrying capacity of beams fulfilled structural requirements even after decayed sections had been removed because heavy sawdust fill was replaced by lightweight min eral wool. Joists in poor condition were replaced by glue laminated beams. In certain locations, wooden floors were replaced by reinforced concrete slabs to support and stabilise limestone masonry walls in poor condition.

ATTICS AND ROOF

Except for two concrete stair towers, wood was used for all roof construction. The attics and roof in the chancery, severely deteriorated from a lack of maintenance, were replaced completely. Particularly at the south wall, the decayed ends of roof beams were replaced. Roof repairs were generally carried out using the same techniques applied to floors. The extremely poor condition of metal roofing throughout the complex required its complete replacement.

NEW CONSTRUCTION

Besides those parts of buildings that were completely replaced, new construction was necessary at attics that were taken into use for such functions as mechanical equipment rooms and a sec tion of the ambassador’s private residence.

STAIRS

In its pre-renovation state, the complex contained seven distinctly different steel, stone, con crete, and wood staircases. Of these, only three were worth restoring: the remaining four stairs were completely reconstructed using steel and concrete.

OIL TANK AND PIPING TRENCHES

To ensure an uninterrupted energy supply, two oil tanks have been located in watertight concrete basins concealed under the upper yard. Because all the buildings on the site form an intercon nected chain, it was not always possible to fit the large amount of required pipes, ducts, and cables into existing basement spaces appropriated for new uses. For that reason, a partly visible, partly buried piping tunnel 60 metres in length was constructed from the oil tank along the foundations of the buildings to the residence’s basement spaces.

LIFT

While not originally planned, a lift was added by the client while the works were in progress. The frame was constructed using 150 x 150 x 3 mm concrete-filled steel tubes that were fixed to floors and exterior walls with fire-insulated steel profiles. Floor joists interrupted by the lift shaft were supported by steel construction, and structural steel columns were founded on the concrete walls of the underground pipe tunnel.

Väljaandja | Publisher Soome suursaatkond, Tallinn | Embassy of Finland, Tallinn Tõlked | Translations Kulle Raig, Roger Freundlich Korrektuur | Proofreading Kai-Riin Meri

Fotod | Photography Tanel Meos, Kaido Haagen, Jussi Tiainen, Sven Tupits, Tallinna Linnaarhiiv Kujundus | Layout Priit Isok | RAKETT

Tallinn 2022