8 minute read

The importance of bridging the digital divide for primary school children

The importance of bridging the digital divide for secondary school students

SARAH DAVIES, CEO OF NATIONAL CHILDREN’S CHARITY, THE ALANNAH & MADELINE FOUNDATION, DISCUSSES WHY ALL CHILDREN MUST HAVE ACCESS TO DIGITAL LITERACY FRAMEWORKS IN ORDER TO BRIDGE THE DIGITAL DIVIDE.

CEO of the Alannah & Madeline Foundation Sarah Davies. ESo much of life nowadays happens online. Digital technologies bring many positive opportunities to teenagers and reforms to NAPLAN assessments will see Year 10 students being tested on digital literacy, if the school opts in.

But those students who can’t access high quality digital resources or information about how to use them safely may be excluded from basic educational and career opportunities and are also at risk of exploitation. What is digital literacy and why is it important? Digital literacy and digital intelligence describe the set of skills and knowledge that students need to appropriately identify, select and use digital devices or systems. Knowing and understanding how to make the most of the technologies available to them, adapting to new ways of doing things as technologies evolve and protecting themselves and others safely in digital environments are essential skills for all our children. Poor digital literacy levels can lead to significant disadvantage over a lifetime, with digital inclusion being critical for people to engage in education, employment and public life, as well as to access health, financial and community services.

WHO IS MOST AT RISK OF DIGITAL EXCLUSION?

Many of Australia’s most vulnerable children and their families also have the lowest levels of digital literacy and digital inclusion. According to the Australian Digital Inclusion Index (ADII): • Households with the most precarious access to technology and the lowest digital skills tend to be those which are already struggling with other barriers, such as low incomes, unemployment, disability, internet access through mobile phone data only, and education levels below Year 12.

Indigenous Australians are particularly affected. • Major inequalities exist between capital cities and rural areas. The Australian regions with the lowest digital inclusion are all rural, including

North-East New South Wales, North-West

Victoria, North-West Queensland and Burnie and

West Tasmania.

In particular, the ADII notes that 800,000 school students are growing up in families in the lowest income bracket, where digital inclusion scores are well below the national average.

A survey of nearly 2,000 Australian teachers found that four out of five teachers believed students’ access to educational technology was affected by their socio-economic circumstances.

CHILDREN NEED SUPPORT IN THEIR ‘MIDDLE YEARS’

The years between the ages of 10 and 14 are hugely

Dex is one of a range of characters who guide students through the gamified learning experience.

significant for children, inlcuding the onset of puberty and the move from primary to secondary school.

The middle years are also a critical time for young people’s digital literacy and wellbeing.

An ACMA report found that more than threequarters of Australian children aged 12 to 13 owned the mobile phone they used, while, according to a Royal Children’s Hospital poll, three in four teens have their own social media account.

Recent research from the Office of the eSafety Commissioner into the digital lives of teenagers found they spend an average of 14.4 hours a week online – 93 per cent to chat to friends and 77 per cent playing online games. In fact, six out of 10 children and young people are online gamers. Young people are very much using digital technology to form social networks.

COVID-19

The onset of COVID-19 saw a rapid transformation in the way students learn. Lockdowns and remote learning are especially hard on families in the lowest income bracket, many of whom lack access to suitable devices and tech options, have fewer digital skills, and who pay more of their household income for digital services, compared to the rest of Australia.

New statistics from the Office of the eSafety Commissioner saw online risks continue to rise through the first half of 2021.

Complaints of serious cyber bullying against Australian children, for example, have been up by almost 30 per cent on the same period in 2020.

Research from Monash University revealed that cyber bullying represents the top social issue negatively affecting school communities – 60 per cent of principals and assistant principals ranked this issue within their top three.

REDUCING DIGITAL DISADVANTAGE

Building digital intelligence across all Australian society is an absolute must to keep our children safe from online harm.

Teaming up with international digital intelligence think tank, the DQ Institute, and Accenture Australia, the Alannah & Madeline Foundation has recently launched its eSmart Digital Licence+, an education and training program aligned to the Australian curriculum which builds digital intelligence among 10 to14-year-olds.

A completely updated and reworked version of the eSmart Digital Licence, Digital Licence+ offers an exciting learning experience with gamified elements for students to explore an interactive story world to build digital intelligence.

Focusing on building the knowledge and skills of students across areas including technology use, cyber risk management, cyber security and online cultures, Digital Licence+ supports the development of important social and emotional skills in the middle years and assists educators to cater for different learning levels.

A targeted rollout offering access to the Digital Licence+ is now available at no cost to for eligible schools and aims to address the digital divide in regions with low levels of digital inclusion and below average ADII ranking. All other schools across Australia will have access in 2022. Visit digitallicenceplus.org to see if your school is eligible. EM

Davies says building digital intelligence across all Australian society is an absolute must to keep children safe from online harm. The onset of COVID-19 saw a rapid transformation in the way children learn with remote learning.

Insights on the wellbeing of school leaders throughout COVID-19

RESEARCH FROM DEAKIN’S EDUCATOR HEALTH AND WELLBEING TEAM HAS UNCOVERED THAT WHILE THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAS BEEN A MIXED BAG FOR EDUCATORS, SCHOOL LEADERS’ FAITH IN THEIR ROLES REMAINS LARGELY POSITIVE. DEAKIN UNIVERSITY POST-DOCTORAL RESEARCH FELLOWS BEN ARNOLD, MARK RAHIMI AND MARCUS HORWOOD (OF THE HEALTH AND WELLBEING TEAM) RECOUNT.

EOver the last year, concern has grown about the health and wellbeing of education professionals. Preventative measures aimed at addressing the coronavirus pandemic, such as the partial or complete closure of schools, colleges and universities, have had a significant impact on those working in the education sector. In many contexts, educators have been required to adapt to a ‘new normal’ where they work on the frontline of the pandemic alternating between face-to-face and online teaching and caring for the health and wellbeing of their school community.

The question of how to promote the development of safe, healthy work environments for educators their communities is of particular interest for us in Deakin’s Educator Health and Wellbeing Team.

Formed by Professor Phil Riley in 2018, we track education professionals working environments and health and wellbeing over time.

We currently undertake research with educators at all levels of the education system, from early childhood through to tertiary education,

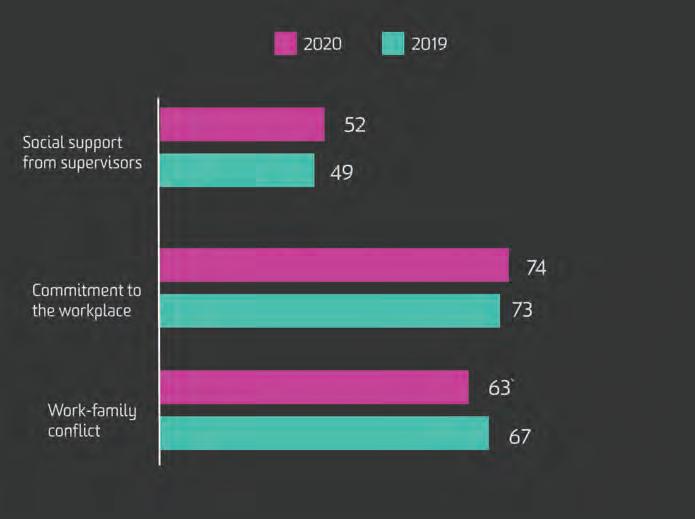

Figure 1: Australian School Leaders’ interpersonal relations at workplace in 2019 and 2020 (%) to investigate how their workplace and work tasks impact on their mental and physical health. Our aim is to provide researchers, policymakers and educational leaders with evidence that can be used to establish healthy, safe working environments.

We also embed our discoveries and knowledge into Deakin’s postgraduate education courses, to better prepare the leaders of the future, and into educational policy and practice.

This year, we drew on Professor Phil Riley’s research into school leaders to map school leaders’ experiences of work during 2020 – the first year of the pandemic – and identify the issues and opportunities facing this group of educators in this current context.

While working conditions have been unfavourable, we were pleased to discover that school leaders reported some positive changes to their work environment.

SEVERAL DISRUPTIONS AND DECLINING FAIRNESS AT WORK

School leaders reported that while their workloads declined slightly, they continued to be a major burden and source of stress.

Our analysis also found that school leaders’ work environments changed during the 2020 and became more fluid and unstable.

School leaders reported that their work was less predictable in 2020 and they were less clear about the exact nature of their job role, expressing more doubt about their workplace tasks, duties and responsibilities.

School leaders also reported considerably lower levels of justice at their place of work in 2020, meaning that workplace procedures, interactions and the distribution of work were perceived to be less fair than in previous years.

STRONGER RELATIONSHIPS AND BETTER WORK-LIFE BALANCE

But despite these challenges, school leaders also appeared to experience a number of positive changes at work during 2020.

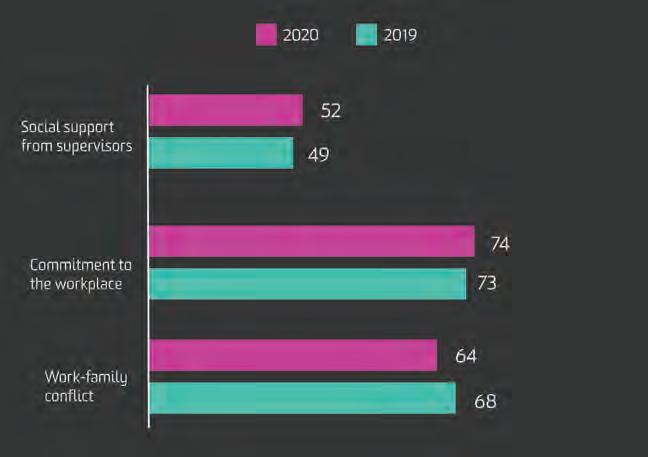

School leaders reported receiving greater levels of support from their supervisors and colleagues, and reported a stronger sense of commitment to work during the first year of the pandemic.

Contradictory to some reports, school leaders also reported having a significantly better balance between

Deakin’s Educator Health and Wellbeing Team are investigating how educators’ workplace and work tasks impact their mental and physical health.

Figure 2: Australian School Leaders Social Support and Work Life Balance in 2019 and 2020 (%).

work and their home lives, with work less frequently affecting the time they spent with family members and the energy they had available at home in 2020.

AUSTRALIAN SCHOOL LEADERS SOCIAL SUPPORT AND WORK LIFE BALANCE IN 2019 AND 2020 (%)

Overall, the changes forced by the pandemic to the work environment appear to have affected school leaders’ mental health and wellbeing. Compared to 2019, school leaders reported an increase in levels of stress and burnout in 2020.

Although less is known about the impact of the pandemic on the work and wellbeing of school teachers and early childhood educators, anecdotal evidence suggests that these education professionals have been significantly impacted.

At Deakin, we’re committed to undertaking robust research involving these groups of educators to better investigate their current working conditions and the status of their mental and physical health and wellbeing.

To learn more about Deakin’s School of Education and research priorities in education and teaching, visit deakin.edu.au/education EM

Buyer’s Guide

Deakin University Ph: 1800 963 888 Email: myfuture@deakin.edu.au Web: www.deakin.edu.au/education