Advancing Health Equity in North Carolina

Recommendations for Improving Sickle Cell Disease and Maternal Health Care Among Medicaid Enrollees

Recommendations for Improving Sickle Cell Disease and Maternal Health Care Among Medicaid Enrollees

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs Policy Workshop Report

February 2022

Workshop Instructors

Heather Howard

Daniel Meuse

Authors

Nitya Agrawal

Emily Audet

Rachel Fehr

Sophie Graham

Philippa Haven

Conor Hussey

Jenna Overton

Jeff Simon

Annie Yu

Christine Zizzi

This report was prepared by Master in Public Affairs students at the Princeton University School of Public and International Affairs. This report incorporates information gathered through students’ independent research, interviews conducted from October to December 2021, and guidance from course instructors Heather Howard and Dan Meuse. The report fulfills the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs’ degree requirements for an immersive policy workshop and associated policy proposal.

The authors acknowledge the generous support and insights offered by the individuals listed below. Their perspectives and insight into the health care landscape of North Carolina guided the research and analysis used to develop the recommendations included in this report. The authors would like to especially acknowledge the guidance, wisdom, and support of professors Heather Howard and Dan Meuse. Finally, the authors would like to thank the staff of the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services and the Princeton University School of Public and International Affairs, without whom this report would not have been possible. Specifically, Dr. Emma Sandoe for the opportunity to do this report and Ryan Linhart for his support with policy workshop logistics.

This report includes insights from a range of individuals, but the analysis and recommendations contained herein are solely the views and responsibilities of its authors.

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services

Dr. Mandy Cohen, Former Secretary

Emma Sandoe, Associate Director of Strategy and Planning, NC Medicaid

Dave Richard, Deputy Secretary, NC Medicaid

Jay Ludlam, Assistant Secretary, NC Medicaid

Dr. Shannon Dowler, Chief Medical Officer, NC Medicaid

Julia Lerche, Chief Strategy Officer and Chief Actuary, NC Medicaid

Kimberley Kilpatrick, Contract and Compliance Specialist, NC Medicaid

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Dr. Sophie Lanzkron, Director, Sickle Cell Center for Adults and Professor of Medicine

Justin Calhoun, Sickle Cell Program Supervisor

Susan Johnson, Sickle Cell Educator Counselor

Naomi Moore, Sickle Cell Educator Counselor

Community Care of North Carolina

Dr. Tom Wroth, President & CEO

Kimberly DeBerry, Maternal Child Health Director

Dr. Marian Earls, Deputy Chief Medical Officer

Carlos Jackson, Executive VP & Chief Data and Analytics Officer

Dr. Kate Menard, OB Physician Champion

North Carolina Community Health Workers Association

Honey Yang Estrada, President

Duke University Sickle Cell Center and SCD Community Advisory Committee

Dr. John Strouse, Hematologist, Pediatric Hematology-Oncology Specialist

Members of the SCD Community Advisory Committee

East Carolina University Sickle Cell Comprehensive Clinic

Dr. Darla Liles, Chief, Division of Hematology/ Oncology

Dr. Beng Fuh, Director

Dr. Charles Knupp

NC Child

Kaylan Szafranski, Health Program Director

La-Mine Perkins, Assistant Director of Community Engagement

North Carolina General Assembly

Representative Ricky Hurtado (D – District 63)

North Carolina Justice Center

Hyun Namkoong, Deputy Project Director, Health Advocacy Project

North Carolina Medical Society

Chip Baggett, Executive Vice President & Chief Executive Officer

Alan Skipper, Vice President, External Affairs

Ashley Rodriguez, Chief Legal Officer

NCCARE360

LaQuana Palmer, Program Director

Princeton University

Dr. Keith Wailoo, Henry Putnam University Professor of History and Public Affairs

Triangle Doulas of Color

Ste’Keira Shepperson, Owner, Birth Doula, Postpartum Doula, and Childbirth Educator

UnitedHealthcare

Karla Theobold, Director of Maternal and Child Health

Dr. Michelle Bucknor, Chief Medical Officer, Community & State

Dr. Robert Eick, VP of Clinical Strategy

Dr. Derrick Hoover, Medical Director, Community & State

Kern Eason, Clinical Practice Performance Consultant, Maternal and Child Health

University of Minnesota School of Public Health

Katy Kozhimannil, Distinguished McKnight University Professor, Division of Health Policy and Management

University of North Carolina Collaborative for Maternal and Infant Health

Erin McClain, Assistant Director and Research Associate

Kimberly Harper, Perinatal Neonatal Outreach Coordinator

University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health

Dorothy Clienti, Associate Professor, Department of Maternal and Child Health

University of North Carolina OneSCD

Dr. Jane Little, Director of the Adult Sickle Cell Program

Dr. Jacki Baskin, Pediatric HematologyOncology Specialist

Tara Alin, Nurse Practitioner

Diana Wells, Clinical Social Worker

WellCare

Sue Lynn Ledford, North Carolina Director of Field Services

Affordable Care Act

American Society of Hematology

Cesarean Section

Community-Based Organization

Community Care of North Carolina

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Children’s Health Insurance Program

Community Health Worker

Certified Midwife

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Certified Nurse Midwife

Certified Professional Midwife

Delayed Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions

Day Hospital

Department of Health and Human Services

Division of Public Health

East Carolina University

Emergency Department

European Medicines Agency

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment

External Quality Review Organization

Food and Drug Administration

Federal Poverty Level

Health Effectiveness Data and Information Set

Health Resources and Services Administration

Hydroxyurea

Institute for Clinical and Economic Review

Local Health Departments

Mountain Area Health Education Center

Managed Care Organization

Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program

Michigan’s Maternal Infant Health Program

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services

Non-Emergency Medical Transportation

Nurse-Family Partnership

National Institutes of Health

National Quality Forum

Primary Care Physician/Provider

Prepaid Health Plans

Pregnancy Medical Home

Quality-Adjusted Life Year

Red Blood Cell

Subscription-Based Payment Model

Sickle Cell Disease

Sickle Cell Data Collection

Social Determinants of Health

State Plan Amendment

Transcranial Doppler

Ultrasonography

Transportation Network Companies

University of North Carolina

Vaso-Occlusive Crisis

The following report outlines strategies for the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NC DHHS) to consider implementing in order to improve Medicaid enrollees’ access to and quality of care. These strategies specifically focus on the health outcomes and racial and ethnic disparities that exist among two populations, enrollees living with sickle cell disease (SCD) and enrollees who are pregnant or postpartum.

This report is based on stakeholder interviews conducted in North Carolina in Fall 2021 and a literature review focused on Medicaid’s role in advancing health equity for these two populations. The interviews and literature review revealed that Medicaid enrollees, including enrollees with SCD and who are pregnant or postpartum, face similar barriers to quality care, such as transportation, provider bias, care management, and data gaps. Several SCD-specific challenges were identified, including continuity of care during the pediatric to adult transition, access to care, and lack of universal screenings. Challenges specifically related to pregnant and postpartum enrollees were also identified, including the lack of clinical and non-clinical support during pregnancy and postpartum and the lack of continuity of care across the peripartum period.

This report provides recommendations for NC DHHS to address each of these challenges. The goal of these recommendations is to ensure that the promise of Medicaid Managed Care is fulfilled, and that the needs of enrollees who are at a higher risk of experiencing barriers to quality care are sufficiently addressed.

Below is a high-level summary of recommendations for NC DHHS, Medicaid, and/or DPH to implement in order to improve Medicaid enrollees’ access to and quality of care.

Rural Health

• NC DHHS should convene a working group with two subcommittees—one for SCD and one for maternal health—to develop best practice standards for establishing hub and spoke models of care.

Transportation

• NC Medicaid should offer ridesharing as a form of Non-Emergency Medical Transportation (NEMT).

• NC Medicaid should provide NEMT tailored to the needs of pregnant and postpartum women.

Provider Bias Training

• NC DHHS should expand and improve its implicit bias training requirements to include perinatal and SCD providers.

Non-Medical Drivers of Health

• NC DHSS should increase resources in NCCARE360 and CBOs to ensure their ability to address non-medical drivers of health.

Data Gaps

• NC DHHS should ensure the public has access to timely and useful data.

Care Management

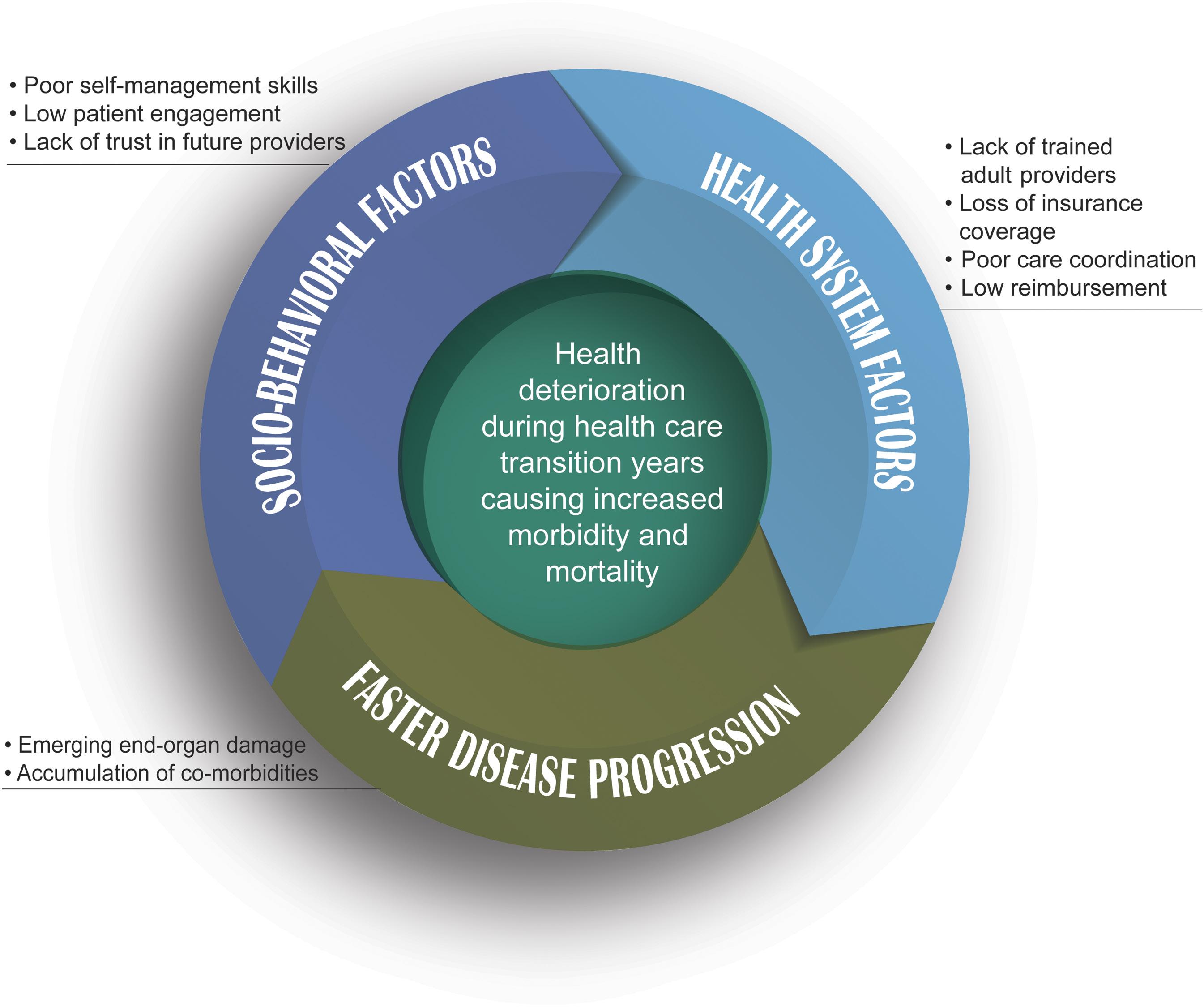

• Pediatric to Adult Transition Care Models. NC Medicaid should encourage support during the transition of pediatric patients with SCD into adult care.

• Primary and Specialty Care Coordination. NC Medicaid should invest in the development of a network of primary care providers (PCPs) knowledgeable about the treatment of SCD and should implement additional financial incentives for care coordination between PCPs and SCD experts.

• DPH Existing Programs. NC DHHS should support legislation to increase funding for the NC Sickle Cell Syndrome Program to ensure continuous care and treatment for people with SCD.

Access to Care and Services

• Telehealth. NC Medicaid should cover physician and hospital outpatient telehealth services at parity for people with complex care needs, including the Medicaid population that experiences SCD.

• Sickle Cell Day Hospitals. NC DHHS should bolster established SCD day hospitals in North Carolina.

• Hydroxyurea. NC Department of Health Benefits (DHB) should aim to improve hydroxyurea (HU) access and uptake among people with SCD.

• Pain Management. NC Medicaid should require PHPs to take steps to improve pain management approaches within the SCD population.

• Red Blood Cell Molecular Testing. NC Medicaid should expand required newborn traditional blood testing.

• Transcranial Doppler Ultrasonography. NC Medicaid should facilitate annual transcranial doppler ultrasonography (TCD) screening for children with SCD aged 2 to 16.

Leveraging Prepaid Health Plan Contracts

• Priority Population. NC Medicaid should include “people with sickle cell disease” as a priority population in PHP contracts.

• Quality Measures. NC Medicaid should assess PHP performance on outcomes for people with SCD.

Payment Models

• Incentive Programs. NC Medicaid should explore innovative payment models, such as incentive programs, to increase utilization of recommended SCD treatments and improve SCD health outcomes.

• Subscription-Based Payment Models. NC Medicaid should explore innovative payment models, including SubscriptionBased Payment Models (SBPMs), to increase utilization of new therapeutics and improve SCD health outcomes.

Care Management

• Home Visits. NC Medicaid should expand the coverage and quality of services provided through home visiting programs.

• Postpartum Continuity of Care. NC Medicaid should improve access to and continuity of care during the postpartum period.

Care Services

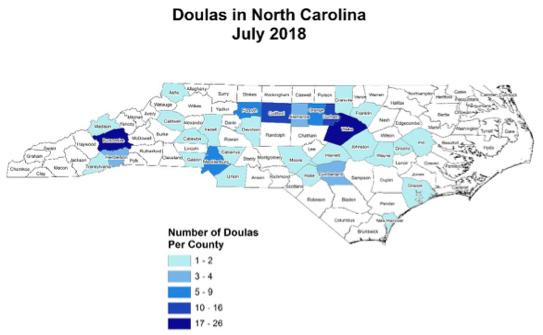

• Doula Services. NC Medicaid should cover and support doula services.

• Group Prenatal Care. NC Medicaid should require PHPs to cover group prenatal care.

Access to Care and Services

• Midwife Workforce. NC DHHS should support changes to the state midwifery certification and reimbursement processes..

• Screening of Perinatal Mental Health Conditions. NC Medicaid should incentivize PHPs to conduct perinatal mental health screenings.

Quality Measures

• NC Medicaid should encourage PHPs to decrease disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Administrative Burden

• NC Medicaid should reduce administrative burdens that keep pregnant and postpartum enrollees from enrolling in Medicaid.

• NC Medicaid should improve enrollees access to translation services during perinatal appointments.

North Carolina has long been a leader in designing and implementing innovative and bipartisan programs that address health care delivery and non-medical drivers of health. Almost 50 years ago, the state created the Sickle Cell Syndrome Program. This program is focused on delivering services to meet the changing needs of sickle cell disease (SCD) patients.1 Ten years ago, the NC Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) established a pregnancy medical home (PMH) model for Medicaid patients. PMHs deliver care to pregnant and postpartum enrollees in a holistic way that includes non-clinical support such as health management and community services.2 In 2018, NC DHHS’ five-year Healthy Opportunities program was approved through a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) 1115 Medicaid Waiver. Healthy Opportunities funds projects focused on non-medical drivers of health, such as the nation’s first electronic, statewide directory of organizations connecting health care and human services, called NCCARE360.3

2022 represents a pivotal year for DHHS. DHHS is operating amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, which is disproportionately impacting those with Medicaid and, as we have seen, Black communities.4 On top of the pandemic, NC Medicaid began transitioning the majority of Medicaid enrollees from fee-for-service to Prepaid Health Plans (PHP)—typically called Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) in states with similar models—in July of 2021. PHPs encompass both Standard Plans and Tailored Plans—designed for people with significant behavioral health needs and intellectual/ developmental disabilities—that will launch in December 2022.5 In this report, we will use PHPs when discussing North Carolina Standard Plans and MCOs when discussing other state models.

NC DHHS officials requested assistance on two health equity-focused policy areas. Specifically, the state Medicaid agency welcomed recommendations on how to design care and payment models for enrollees living with SCD and how to decrease racial and ethnic disparities in maternal health outcomes. While these are two different health experiences, both are marked by glaring racial inequities.

One limitation of this report is that NC Medicaid alone cannot adequately address the systematic racism that leads to inequities in SCD and maternal health outcomes. A second limitation is that this report’s scope does not include the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians Tribal care management plan. As a result, the barriers to care that the North Carolina Indigenous population faces are not addressed. Nevertheless, NC DHHS has the ability to greatly improve the health outcomes and reduce disparities within SCD and maternal health, as this report recommends.

This report envisions a North Carolina where Medicaid enrollees face no shortage of providers and can access care without barriers, Medicaid providers are trained to overcome biases in care, and non-medical drivers of health are fully integrated into the health system. Medicaid enrollees with SCD would receive care from medical professionals who understand their community and holistic care needs, have the option of receiving medical care from the comfort of their home, and have access to fundamental SCD services like hydroxyurea, red blood cell molecular testing, and transcranial doppler screenings. Medicaid enrollees who are pregnant would have access to navigators, multiple home visits, and doulas and certified midwives, and those who are postpartum would receive pre-discharge postpartum care plans and depression screenings and treatment.

The authors of this report are ten Master of Public Affairs candidates at Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs. The graduate students had assistance and guidance from co-instructors Heather Howard and Daniel Meuse, who lead the State Health and Value Strategies program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Between October and December 2021, 22 stakeholder meetings were conducted with representatives from 17 organizations in North Carolina, along with several maternal health and SCD experts from across the nation. Stakeholders included health care providers, PHPs, medical research and academic institutions, government agencies, and patient advocacy groups. The following report incorporates feedback from these meetings, as well as a review of data, academic literature, and evaluations of other state Medicaid policies.

One limitation to our methodology is that our investigation lacks interviews with Medicaid enrollees. Obtaining institutional review board approval was not feasible given our report timeline. We recommend that NC DHHS invites Medicaid enrollees who are SCD patients or pregnant or postpartum mothers to speak about their experience accessing care. Given Medicaid enrollees face resource constraints, NC DHHS should compensate enrollees for taking the time to speak with them.

Stakeholders were overwhelmingly receptive to the recommendations outlined in this report and believed that the recommendations would take North Carolina one step closer to ideal care. We addressed any concerns about operational feasibility that came up in our interviewees, either by adjusting our recommendation or detailing the implementation challenges. North Carolinian stakeholders agreed that while the political will to pass the following recommendations is strong, the prospects of legislative approval are unlikely. Given the political landscape, we recommend prioritizing the recommendations that can be implemented unilaterally.

In this report, we use “women” and “mothers” to describe pregnant or postpartum people. Of note, we recognize that not all people who become pregnant or give birth identify as women. We use these terms to align with the language in the Social Security Act, which establishes pregnancy Medicaid.

Part I of our report details overlapping themes and recommendations for the SCD and maternal population. Part II provides recommendations for designing care and payment models specifically for the SCD population. Part III provides recommendations on Medicaid interventions to improve maternal health outcomes through innovative care and payment models.

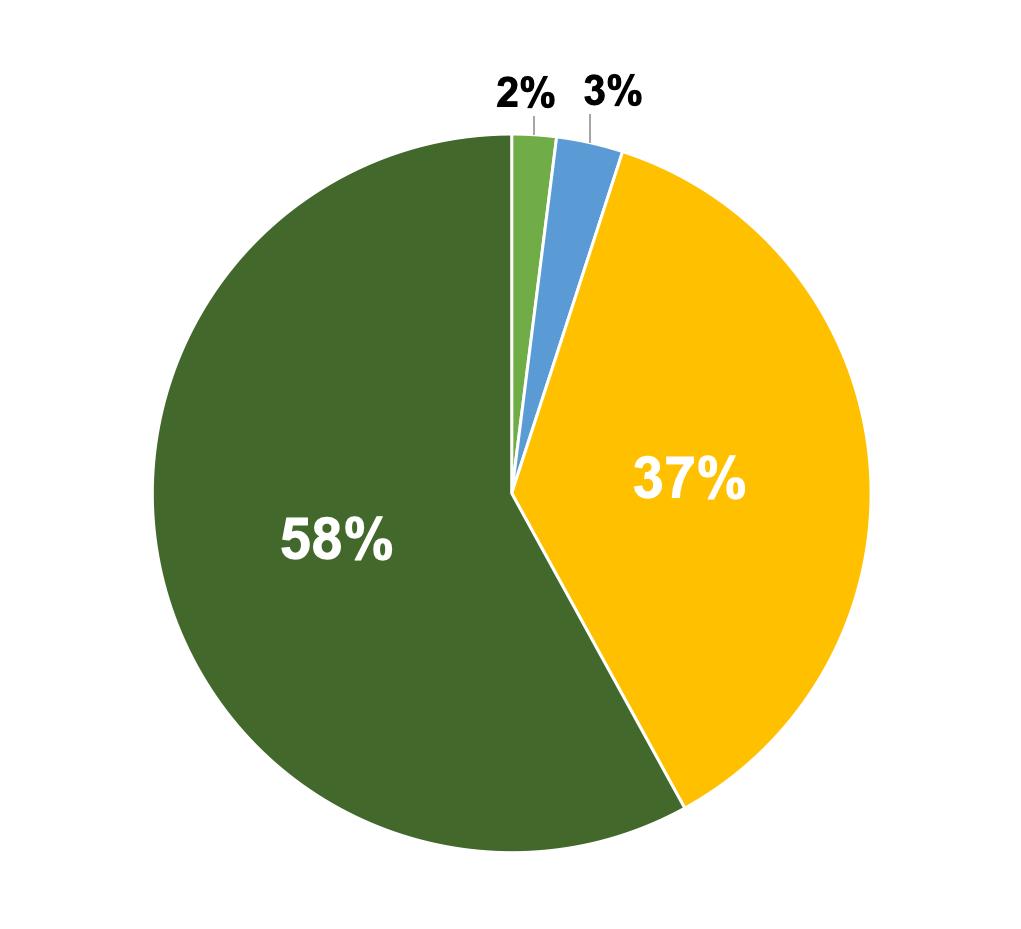

North Carolina’s population is 70.6 percent white alone, 22.2 percent Black or African American alone, 3.2 percent Asian alone, and 1.6 percent American Indian or Alaska Native alone.6 The state’s population is 9.8 percent Hispanic or Latino. Twelve percent of North Carolinians speak a language other than English at home.7 Figures 1 and 2 display the Black population by county and the overall racial demographics of Medicaid enrollees in North Carolina.

The median household income is $54,602 (in 2019 dollars) and 13.6 percent of people are below the poverty line.8 Figure 3 shows the poverty rate by county and Figure 4 shows urban/rural designations by county.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is the most common inherited blood disorder in the United States, with approximately 100,000 Americans having SCD.9 Medicaid is the predominant source of health insurance for people with SCD, covering about 67 percent of children and 45.7 percent of adults with the disease nationally.10 Within North Carolina, approximately 5,000 North Carolinians have SCD.11

Percent of Population that Identifies as Black/African-American (2020)

Figure 1. Percent of North Carolina Population that Identifies as Black/African-American (2020)

0% 60%

© OpenStreetMap

Source:2020 US Census

Data source: 2020 UC Census

Data source: NC DHHS

Indigenous Asian Black White

8% 28%

© OpenStreetMap

Data source: 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates

Source: 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates

© OpenStreetMap

Data source: USDA Economic Research Service

Source:USDA Economic Research Service

Additionally, 80 infants in North Carolina are diagnosed with SCD each year.12 In 2017, 2,082 North Carolina enrollees, or five percent of Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), had SCD.13

SCD is rare among white Americans, with Black newborns being 24 times more likely than white newborns to carry the sickle cell trait.14 It is important to note that SCD affects people of other ethnic minorities, although at a lower rate. One in 12 Black Americans carry the SCD trait, while one in 100 Hispanic Americans carry the SCD trait.15

SCD is caused by a mutation affecting red blood cells (RBCs). While healthy RBCs are round and glide easily through blood vessels, RBCs in people with SCD are sickle-shaped and stiff. This results in RBCs sticking together and blood vessel blockages damaging vital organs and tissue.16

The sickle-shape can cause extensive and severe morbidity.17 Blood vessel blockages can result in the following: i) acute pain episodes, known as “vaso-occlusive crises” (VOCs) or “pain crises;” ii) chronic pain, whose origins are not well-understood; iii) heightened risk of strokes, which in turn may result in cognitive deficits; and, iv) acute chest syndrome if there are blockages in the lung tissue, which is the most common cause of death among people with SCD.18 Median life expectancy for people with SCD is only 42 to 47 years.19

Care utilization for people with SCD is very expensive and often involves hospitalization. In 2012, SCD was ranked the fifth most common principal diagnosis for hospital stays among Medicaid “super-utilizers”—those with four or more hospital stays during the year.20 Pain is the most common SCD morbidity and the primary driver of SCD-related hospitalizations.21 About 81 percent of the costs for SCD-related complications are attributable to inpatient hospital care. Improvements in comprehensive care have the potential to reduce hospitalizations and related costs.22

North Carolina has a strong infrastructure for caring for individuals with sickle cell disease because of its Sickle Cell Syndrome Program, located within the Division of Public Health (DPH). The NC Sickle Cell Syndrome Program provides genetic counseling, education, medical services, reimbursement for treatment, screening, and care coordination. It includes nine regional Educator Counselors, one community-based organization, the Piedmont Health Services and Sickle Cell Agency, six comprehensive sickle cell medical centers, and state program staff.23 However, the NC General Assembly has not increased the program’s budget since the 1980s (except for modest salary increases). The program’s funding levels have not kept pace with the availability of new, more expensive treatments for SCD. The Governor’s appointed Council on Sickle Cell Disease and Other Blood Disorders is currently developing a ten-year plan to address this funding constraint.

The U.S. has one of the highest rates of maternal death and maternal morbidity of any high-income country, and North Carolina’s rates are below the national average. Nationally, an estimated 13 percent of women become pregnant experience life-threatening or potentially life-threatening conditions during the peripartum period.24 An additional 15 percent of women have other maternal complications that are not lifethreatening but serious nonetheless.25 Between 2014 and 2015, 35 North Carolinians died of pregnancy-related causes during pregnancy or within one year postpartum, and many more suffered from maternal complications that did not end in death.26

Examining aggregated data, however, does not show the whole picture. There are significant disparities in health outcomes experiencedby Black pregnant women compared to white pregnant women. In North Carolina, Black women have almost twice the risk of dying from pregnancy-related complications than white women.27 Racial inequities are particularly stark

among the Medicaid population—nationally, Black women with Medicaid are about four times more likely to suffer a severe maternal morbidity than white women with Medicaid.28 Sadly, racial disparities in maternal outcomes are not narrowing, and actually have increased in North Carolina over the past 20 years. 29

Because Medicaid covers more than half of births in North Carolina (see Figure 5), NC Medicaid plays an important role in reducing maternal mortality and morbidity and eliminating racial disparities. Recent steps toward expanding pregnancy-related Medicaid coverage to one year postpartum, along with the transition to Medicaid Managed Care, make this an ideal moment for NC Medicaid to address maternal health disparities.

Women can die from pregnancy-related causes or experience other pregnancy-related issues throughout the peripartum period. Nationwide, 31 percent of maternal deaths occur while women are pregnant, 17 percent during childbirth or in the period shortly after childbirth, and the remaining 52 percent occur after the day of delivery during the first year postpartum.30 The leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths among Black women are a weakened heart muscle (cardiomyopathy) and cardiovascular conditions.31 Of note, these mortality statistics only focus on pregnancy-related issues. Overall, homicide is the leading cause of death while a woman is pregnant or within one year postpartum, with Black women at the highest risk.32 Policies to reduce the risk of homicide during the peripartum period are beyond the scope of this report. However, domestic violence referrals are a component of NC Medicaid’s Healthy Opportunities pilots.33

© OpenStreetMap

Note:"Prenatal Medicaid" means that Medicaid paid for prenatal care and delivery.

Data source: State Center for Health Statistics, NC DHHS

Source:State Center for Health Statistics NC Department of Health and Human Services

Researchers point to a multitude of factors contributing to the high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity across the U.S. First, increased rates of underlying—often undiagnosed—conditions, such as hypertension or diabetes, result in increased health risk for the person while pregnant and postpartum and can increase the likelihood of preterm labor.34 Second, the lack of access to adequate prenatal care throughout pregnancy can result in under-management of pregnancy conditions and risks.35 Third, hospitals overutilize labor interventions, such as cesarean sections (C-sections) and epidurals, that can worsen health outcomes when used unnecessarily.36 Fourth, the lack of continuous care after sixweeks postpartum results in clinicians missing early detections of postpartum complications.37 Finally, structural racism in the health system affects patients’ access to care and results in bias in care received while in clinical settings.38

We must examine these racial disparities through a lens that considers systemic factors and non-medical drivers of health. Women with preexisting chronic conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypertension), mental health disorders (e.g., depression, substance abuse) and prepregnancy obesity have an increased likelihood of experiencing a poor maternal outcome.39 Black women suffer from these medical conditions at a higher rate due in part to systemic racism and non-medical drivers of health such as access to housing, food, and social support systems. Black pregnant women are also more likely to be treated at underfunded, low-quality hospitals, which contributes to worse outcomes.40 Even when receiving care at the same hospital, Black women are at higher risk for maternal mortality and morbidity than white women.41 In rural areas, these racial disparities can be compounded by access issues and provider shortages, as many rural North Carolina hospitals have shut down their maternity units in recent years.

The North Carolina Maternal Mortality Committee determined that 63 percent of maternal deaths were preventable. Forty-one percent of these

preventable deaths were classified as “having a good chance to avert the outcome ‘by one or more changes to patient, family, provider, facility, system and/or community factors.’”42 Although the Committee did not break down the data by race, nationally Black pregnant women are more likely to die from a preventable death.43

Not only are these poor maternal health outcomes disastrous for the women and babies in North Carolina, they also cost the state’s health care system money. Medicaid births with complications cost almost twice as much as births with no complications.44 Additionally, postpartum women with poor maternal health outcomes have a higher chance of being readmitted to the hospital and may have longterm health issues that cost the state.

Infant mortality, and racial disparities present in the infant mortality rates, are also major issues in North Carolina. In 2019, the Black infant mortality rate was 2.7 times that of the white infant mortality rate. Many of the same factors that contribute to maternal mortality and morbidity within the Black population in North Carolina also affect poor infant outcomes. While reducing the infant mortality rates is an extremely important component of improving the health of North Carolinians, this report will focus on efforts to improve maternal health.

In the U.S., systemic racism has led to unequal resource allocation and Black, Indigenous, and people of color having less wealth, lower socioeconomic status, poorer access to health care, and worse health outcomes compared to their white counterparts—all of which impact health outcomes. Racism also negatively impacts mental and physical health and is a fundamental driver of racial and ethnic health disparities.45

The health care system itself is not immune to the racist and discriminatory practices of broader society. Hospitals were rigidly segregated in the 19th and 20th century until the threat of losing federal funding from Medicare in 1965 forced them to desegregate. Medical professionals participated in state-sanctioned sterilizations of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color in the 20th century, and also led the Tuskegee Syphilis Study that withheld treatment from hundreds of Black men to track the course of disease. Medical education perpetuated false beliefs of biological differences like greater pain tolerance among Black people.46 These legacies of mistreatment that generated medical mistrust among communities of color are exacerbated by the firsthand negative experiences people of color have with providers who discriminate against them.

In recent years, racial health disparities have gained attention as the country reckons with racial injustice. This report provides policy recommendations that are focused on addressing coverage, access, and clinical health needs. These recommendations also incorporate the understanding that racism is embedded in the health care system and improving health outcomes requires more than addressing health care. Improving health outcomes requires confronting the systems that have led to generational injustices that result in racial and ethnic health disparities, as well as a peoplecentered approach and a critical assessment of policies.

Sickle cell disease sits at the intersection of racism and the health care system. SCD primarily affects people with African ancestry. The perception of SCD as a “Black disease” and proxy for Black health has shaped attitudes towards people affected by the disease. In the early 20th century, sickled cells were viewed as an “inherent feature of Negro blood” and

used to confirm fundamental biological race differences and prejudice about racial mixing and integration.47 As medicine’s interest in the disease grew, people with SCD became valued as medical subjects—however, there was a reductionist focus on blood cells and the molecular level of the disease, not the patient experience or pain associated with SCD.

Pain is a major symptom of the disease, but the difficulty of objectively measuring pain led to a decline in sympathy for people with SCD and a crisis of patient credibility; the frequent pain episodes and fatigue that people with SCD experience can cause absenteeism, contributing to a stereotype of unreliability and fragility. Society also began to associate inferiority, addiction, and low mental capacity as the “real” problems with SCD, and this stigma has led to discrimination, devaluation, lower quality of care, strained patient-provider relationships, and greater pain from being labeled as drug seeking and providers not taking their pain seriously. Many problems intersect with anti-Black prejudice: studies show racial disparities in pain assessment and treatment, and providers are more likely to dismiss Black people’s pain.48,49

In 1972, the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act of 1972 was passed, which provided funding for research, patient care, and reproductive counseling for parents. Although the legislation provided much needed attention to SCD, reproductive counseling also raised very real concerns of discrimination, eugenics, and reproductive control of Black bodies. Linus Pauling, one of the people who discovered that hemoglobin played a major role in the formation of sickle red blood cells, once suggested “[t] here should be tattooed on the forehead of every young person a symbol showing possession of the sickle-cell gene…”50 Thus, promises of innovations like gene therapy are tempered by mistrust and negative experiences with the health care system.

Despite being the most common genetic disease, SCD suffers from a lack of attention and resources. In the U.S., the projected life expectancy for people with SCD is 54 years compared to 76 years for people without SCD in the U.S.; quality-adjusted life expectancy is 33 years for people with SCD compared to 67 years for people without SCD.51 Despite gains in life expectancy, there is still no formal protocol for the transition from pediatric to adult care, leaving gaps in treatment and care.

Cystic fibrosis (CF), which is a comparable inherited, life-threatening disease that primarily affects white people, affects one-third fewer Americans than SCD, but receives four times the amount of federal funding and seven times the foundation funding.52 Few adult hematologists focus on SCD and most providers lack knowledge on SCD, which prevents people with SCD from receiving recommended therapies and appropriate pain management.53

Furthermore, stigma still surrounds SCD and the pain experienced by people with SCD continues to be undertreated. The story of SCD presents what Dr. Keith Wailoo, a historian of medicine, describes as a “disturbing portrait of America, one in which basic health and social services are often hard to obtain, in which skepticism about the motives of patients in pain is rampant, and in which high-stakes gambles [of expensive and risky treatments such as bone marrow transplantation and gene therapy] are too often championed as remedies instead of attending to basic health care needs.”54 Most SCD research has focused on dreams of breakthrough medicine without considering how the marketplace prevents people with SCD from accessing these expensive breakthroughs and overlooking the development of basic care protocols that could benefit many people with SCD.

There is a long history of racism within obstetrics and maternal care. During the era of slavery, J. Marion Sims—often referred to as the “father of modern gynecology”—developed his surgical techniques by experimenting on enslaved Black women.55 Additionally, François Marie Prevost developed the C-section by repeatedly performing the technique on enslaved Black women without consent and without any type of pain medication.56 Once these techniques were developed, however, doctors often failed to perform these interventions on Black women who needed them, choosing to use resources to provide these interventions to white women instead.57

During the 19th century, most U.S. women delivered their babies out of the hospital under the care of midwives, and labor and delivery was a woman-centered, autonomous process. Black midwifery had a strong presence within communities of color, as generations passed down an abundance of knowledge of labor and delivery techniques. However, with the professionalization of medical degrees among white men and a growing concern for the country’s high maternal and infant death rate, Black midwives were pushed out of the workforce. One North Carolina physician rejected Black midwives as having “fingers full of dirt” and “brains full of arrogance and superstition.”58 As deliveries became medicalized, the institutional knowledge of birth possessed by Black midwives was lost and the woman-centered, autonomous process was rejected. By 1950, most deliveries in the U.S. occurred in the hospital setting, placing the doctor in the forefront of the process and often ignoring women’s, and specifically Black women’s, wants and needs. Although the maternal and infant death rate drastically decreased since the 1950s, it is important to note that much of the credit is due to improved public health measures and that racial disparities actually grew during this time.59

The history of obstetric trauma experienced by Black women and the rejection of Black women being actively involved in the birthing process are still felt now. Although the rates of maternal death in the U.S. have drastically decreased compared to rates 100+ years ago, the number of deaths has increased over the past 20 years and the racial disparity in maternal outcomes has increased with it. In the 1990s, Dr. Arline Geronimus coined the term “weathering” to describe the physical and emotional toll being a Black woman in the U.S. takes on the body.60 A recent article described the concept—which has become widely accepted among maternal and child health researchers—as a “kind of toxic stress trigger[ing] the premature deterioration of the bodies of African-American women as a consequence of repeated exposure to a climate of discrimination and insults.”61 This concept, as theorized by Dr. Geronimus, can lead to greater adverse pregnancy outcomes among Black women.62 Today, Black women in the U.S. are five times more likely to die to due to pregnancyrelated causes than white women.

The intersection of SCD and maternal health culminates in poor health outcomes. Pregnant women with SCD have a high risk of morbidity and mortality. Women with SCD are 16 times more likely to die in childbirth than other women and 28.5 percent of women with SCD experience crisis during delivery.63 There is also an increased risk of stillbirth for pregnant women with SCD.64 These issues underscore the importance of quality care and coordinated care for this population that has been marginalized.

Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain the highest level of health possible.65 Achieving health equity requires more than a focus on disease and treatment because the absence of disease does not equate to good health. 80-90 percent of a person’s health is determined by non-medical factors such as socioeconomic, physical environment, and health behaviors.66 Achieving health equity requires focused efforts to address systemic inequalities—including poverty, racism, and discrimination—that result in differences in health outcomes. As health policymakers in a position to elevate the needs of communities that are marginalized, we must intentionally apply a health equity lens and ensure that policies will uplift, and not harm, these communities. In this report, the authors provide targeted recommendations to improve the health outcomes of two Medicaid populations experiencing health disparities in North Carolina: people with SCD and pregnant or postpartum women.

NC DHHS has taken approaches to advance health equity. In 2021, NC Medicaid launched a temporary health equity payment initiative, which enhanced payments to Carolina Access primary care practices serving enrollees from areas in the state with high poverty levels.67 The goal of the program was to improve access to primary care and preventive services where historically marginalized populations faced challenges highlighted by the pandemic. NC Medicaid will evaluate this initiative and gather information to target future investments in programs that improve access to care and address health disparities.

NC DHHS’ Healthy Opportunities pilot emphasizes the importance of non-medical interventions in improving health outcomes. This investment in connecting residents to needed resources are likely to improve maternal health, especially for mothers of color, and aid individuals living with SCD. As the state implements its Healthy Opportunities strategy, it should look for ways to use pilots and lessons learned to advance the goals of this report.

In 2015, the NC General Assembly directed NC DHHS to transition Medicaid from a fee-forservice model to a Prepaid Health Plan (PHP) model. Under the fee-for-service model, NC Medicaid reimbursed providers based on the services they provided and procedures they ordered. In contrast, under the PHP model, the state contracts with insurance agencies, which receive a capitated per-member rate for health care services that is pre-determined and therefore allows for improved budget predictability. Under the PHP model, patient health outcomes are used to assess the performance of providers.

This shift reflects a national trend—approximately 70 percent of Medicaid enrollees in the U.S. are covered by PHPs, and before the transition, North Carolina had been the largest state in the country without substantial PHP involvement in Medicaid provision.68 The state estimated that 1.7 million of its 2.6 million Medicaid enrollees would transition to NC Medicaid Managed Care, which consists of a system of five PHPs.69 The North Carolina PHPs are AmeriHealth Caritas North Carolina, Healthy Blue, Carolina Complete Health, UnitedHealthcare Community Plan of North Carolina, and WellCare of North Carolina.

Beginning July 1, 2021, most Medicaid enrollees in North Carolina began receiving health care coverage through NC Medicaid Managed Care. Some enrollees with more intense health care needs and specific populations like people eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare and children in foster care continued to participate in traditional Medicaid, administered in a fee-for-service model through NC Medicaid

Direct.70 The transition to NC Medicaid Managed Care is still in early stages, but some smaller providers reported challenges in adapting their administrative processes and navigating the new PHP system.71

As Governor Cooper recently reiterated, North Carolina Medicaid expansion remains the ideal policy. Per North Carolina’s 202122 budget, a joint legislative committee was created in January 2022 in order to study the potential effects of Medicaid expansion in North Carolina.72 Build Back Better, federal legislation currently pending in Congress, offers the potential of providing greater coverage to North Carolinians through expanded Marketplace subsidies in non-expansion states. As the legislation has been written and passed in the U.S. House of Representatives as of November 19, 2021, people currently in the coverage gap in North Carolina would not pay premiums and would have access to low-deductible Marketplace plans.73

The recent postpartum coverage extension the NC General Assembly passed has the potential to significantly reduce maternal morbidity and mortality in North Carolina. More than half the maternal deaths in the U.S. happen after giving birth, making the postpartum period an especially vulnerable period for new mothers.74 For the most recent years with available data, Black non-Hispanic women in North Carolina had on average three times greater risk of dying during childbirth than white non-Hispanic women.75 The continuous coverage through oneyear postpartum holds significant promise to improve these disparities.

Expanding Medicaid is the single most meaningful step North Carolina could take to reduce racial health disparities in sickle cell disease and maternal health outcomes.

Over 2.6 million people, or one in four North Carolinians, are enrolled in Medicaid.76 However, over 1.1 million people, or 11 percent of the state’s population, remain uninsured.77 Medicaid expansion, which was not included in the FY 2022-23 state budget, would have cut the uninsured rate in half by providing Medicaid coverage to more than 600,000 North Carolinians.78

In states like North Carolina that have not closed the coverage gap—the population that is not eligible for Medicaid nor premium subsidies for a Marketplace insurance plan—people are at risk of churning into the coverage gap from Medicaid or the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace. In North Carolina, one in five income-eligible adults are at high risk of losing their Medicaid coverage because of the low eligibility threshold (41 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL)).79 The postpartum period is a particularly high-risk time for churn, and 20 percent of pregnant women who lose Medicaid coverage become eligible within a year.80 Similarly, people with SCD have high levels of churn: 31 percent of people with SCD enrolled in California’s Medicaid program and 40 percent of people with SCD enrolled in Georgia’s Medicaid program experienced gaps in coverage.81

Research on the impact of Medicaid expansion has found improvements in uninsured rates, access to care, care affordability and financial stability for enrollees, enrollee health outcomes, and economic benefits to states.82 Many of these changes are particularly impactful for people of color, those with very low incomes, and those living in rural areas.83 Medicaid expansion has benefited states through increased tax revenue, reductions in overall spending, and accelerated economic growth. Medicaid expansion has been shown to lead to roughly seven fewer maternal deaths per 100,000 births.84 This impact was driven by substantial drops in mortality among non-Hispanic Black mothers, leading to overall narrowing of racial disparities.

The following recommendations are based off of a critical analysis of the barriers SCD, pregnant, and postpartum Medicaid patients face in accessing quality care in North Carolina. Several overlapping barriers were identified after interviewing a diverse range of North Carolina stakeholders and perusing empirical studies focused on people with Medicaid. Developing standards for establishing hub and spoke models of care, expanding non-emergency medical transportation, improving implicit bias training, and publicizing key public health data will benefit the health outcomes of SCD, pregnant, and postpartum Medicaid enrollees.

NC DHHS should convene a working group with two subcommittees—one for SCD and one for maternal health—to develop best practice standards for establishing hub and spoke models of care.

Implementation:

• NC DHHS should convene a working group with two subcommittees—one for SCD and one for maternal health—to develop and publish best practice standards for providers that would like to establish or join a hub and spoke system.

• NC DHHS should incentivize providers to operate through hub and spoke models.

• NC DHHS should provide financial support for providers to establish and operate hub and spoke models.

• NC DHHS should support a telementoring program to facilitate instruction between hub and spoke sites.

Background

A “hub and spoke” model of health care delivery consists of a “hub” care provider, which offers a wide range of services and specialist care, and a network of “spokes”, or smaller outlying care centers that offer fewer services.85 The hub and spoke sites coordinate with each other to direct patients to the site most appropriate for their needs and assess the services they require, their risk level (e.g., their SCD care history, whether they have had pregnancy-related complications in the past), and the distance they can travel for care.

For SCD care, the spokes may be internists, primary care physicians (PCPs), emergency nurses, and hospitalists located in rural regions where SCD specialists are inaccessible. Shortages of SCD specialists drive the need for these spokes.

For maternal care, the spokes may be local community hospitals, family practices, midwifery services, or other clinics that focus on routine prenatal and postpartum care but may not have the resources to deliver babies or handle highrisk pregnancies.

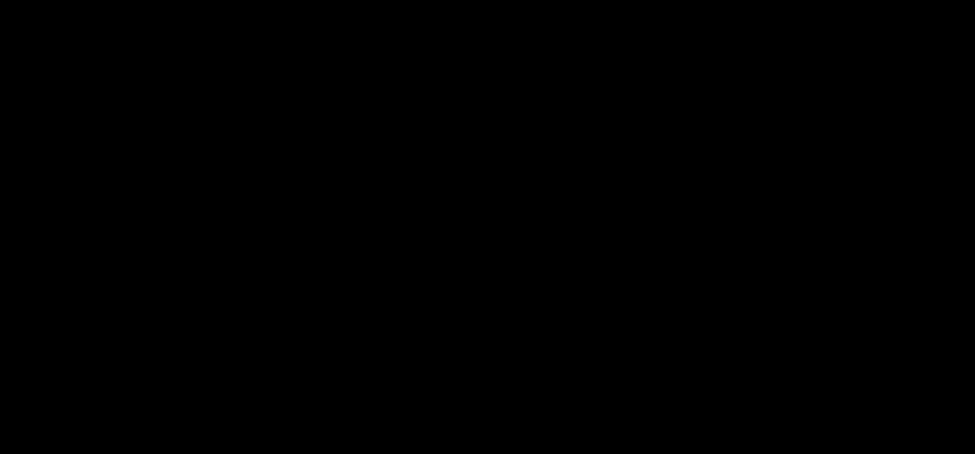

There is a range of potential SCD care models for high-need and/or high-risk patient populations, as displayed in Figure 6. Each model operates best in a specific setting— urban, suburban, or rural regions. For example, a classic comprehensive care center is ideal and feasible in an urban setting. However, this is not feasible in rural regions, including the rural regions of North Carolina.

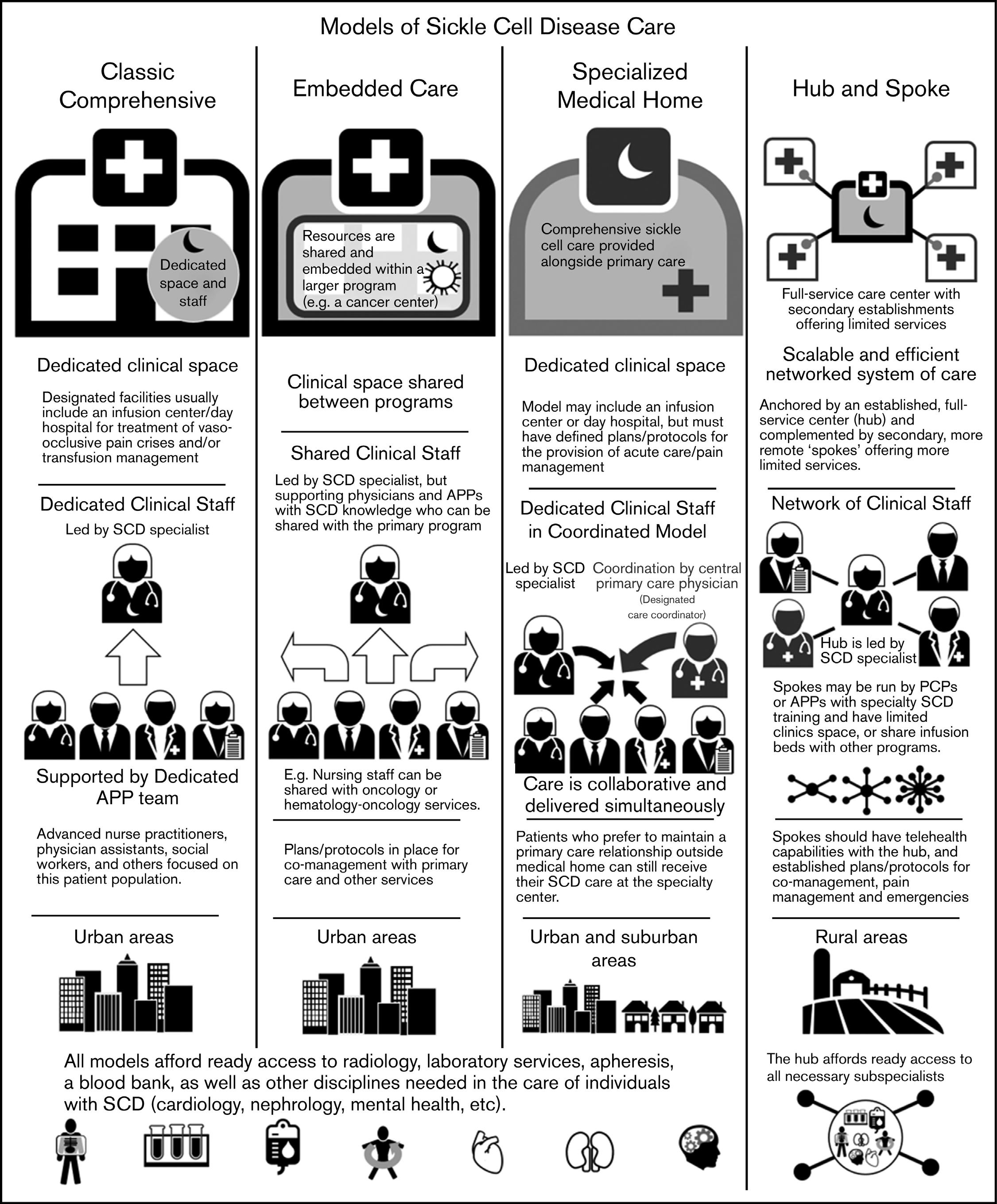

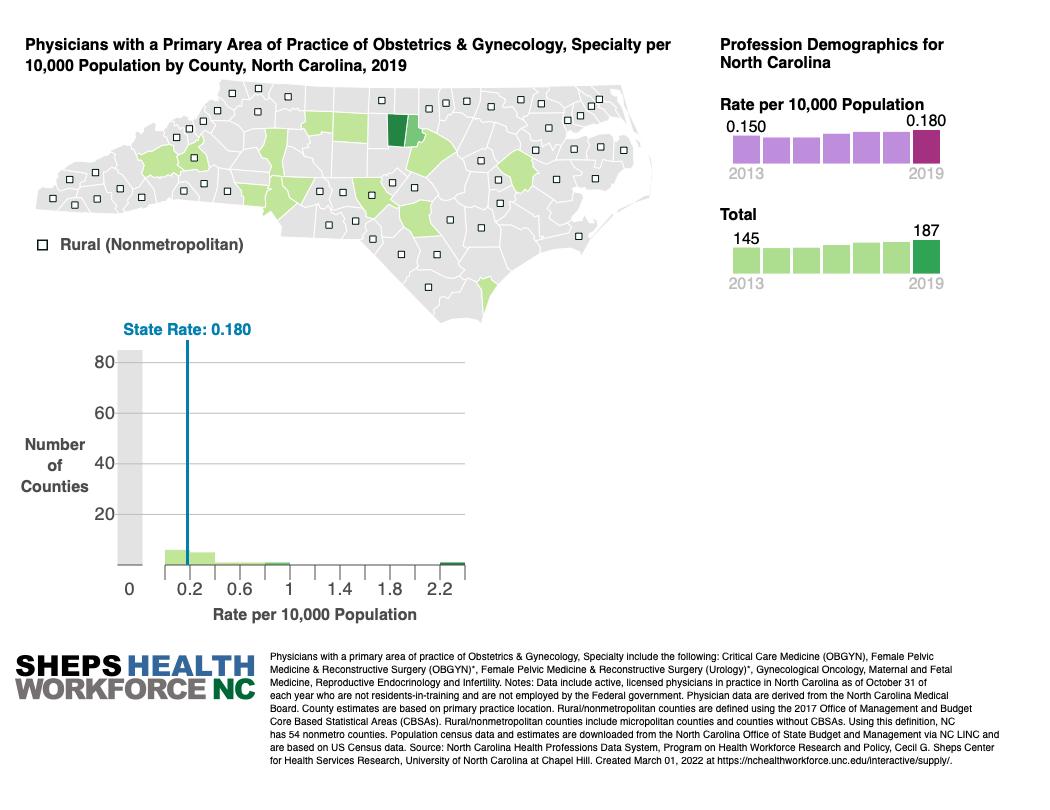

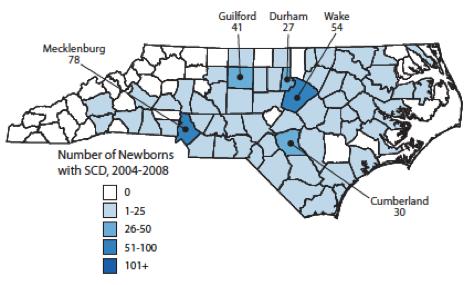

Currently, North Carolina has six SCD comprehensive care centers: Atrium Health, Duke University, East Carolina University (ECU) School of Medicine, University of North Carolina (UNC)-Chapel Hill, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, and Mission Hospital (pediatric only).86 As a result, there are geographic disparities in access to physicians specializing in SCD care, such as hematologists/ oncologists. In North Carolina in 2019, about one hematologist/oncologist existed per 20,000 residents. Over 40 counties had no hematologist/ oncologist, including many counties in eastern North Carolina, which has a sizable population of newborns with SCD.87 There is a mismatch between the geographic distributions of hematologists/oncologists and newborns with SCD in the state. See Figures 7 and 8 for details, and note that these maps may underestimate the full extent of the problem.

Individuals with SCD who reside in rural areas are more likely to lack comprehensive coordinated care, have higher rates of acute care utilization and readmission, and greater dissatisfaction with care received, compared to their urban counterparts.88 In interviews with several key provider-facing and patient-facing NC stakeholders, difficulty with access to SCDspecific care for rural community members

was repeatedly raised. Stakeholders frequently mentioned difficulty surrounding the time required to travel long distances, money to pay for gas, timing of appointments, and low energy levels to make necessary drives.

Lack of access to specialized care hinders provision of standard SCD care, including standard treatments (e.g., hydroxyurea, iron chelation, transcranial doppler ultrasound screening). Additionally, as new medications for SCD offer hope for patients (e.g., crizanlizumab, voxelotor, L-glutamine), these treatments and, subsequently, potentially improved outcomes will not be available without access to specialized care. New therapeutics cannot stand alone— regular comprehensive care is needed.

In a 2020 Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) report, patients with SCD expressed concerns about doctors not knowing enough about new therapies to be willing to write prescriptions.89 In a 2021 study of providers in the U.S., significant barriers to providing care were influenced by providers’ specialty, training, and practice setting.90 Providers that were not SCD specialists were not comfortable providing essential SCD care.

Access to adult comprehensive SCD programs is associated with numerous improved health outcomes, including fewer acute care visits, fewer emergency department (ED) visits, fewer hospitalizations, and decreased health care costs overall.91 Additionally, access to SCD care leads to increased likelihood of being prescribed hydroxyurea (HU), which has been shown to lead to improved psychosocial outcomes.92 All of these improvements contribute to anticipated improved qualityof-life and improved cost-effectiveness when compared to ED-based care. With many SCD patients living in rural communities and without immediate access to one of North Carolina’s six comprehensive care centers, improved care coordination between rural providers and comprehensive SCD centers is essential and can be achieved through hub and spoke models.93

Source: Julie Kanter et al., “Building Access to Care in Adult Sickle Cell Disease: Defining Models of Care, Essential Components, and Economic Aspects,” Blood Advances 4, no. 16 (2020): 3804–13.

Source: North Carolina Health Professions Data System, Program on Health Workforce Research and Policy, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Created February 08, 2022 at https://nchealthworkforce.unc.edu/interactive/

Similarly to SCD patients, pregnant and postpartum North Carolinians have difficulty in accessing care in rural areas. North Carolina, like the U.S. overall, has a concerning shortage of maternal health care providers, particularly providers of color and in rural areas. The national OB-GYN workforce is roughly 6,0008,800 providers short of the necessary levels, according to CMS.94 The shortage of providers of color and providers in rural areas is even more severe. As of 2019, 25 counties in North Carolina, including 16 rural counties, have no OB-GYN providers, and another 12 counties have a single OB-GYN (Figure 9).95 Midwife care is also severely lacking in North Carolina (see Midwife Workforce Section in Part III for more detail).

Source: National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Division of Blood Disorders, “Sickle Cell Disease in North Carolina” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Source: North Carolina Health Professions Data System, Program on Health Workforce Research and Policy, Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Created February 08, 2022 at https://nchealthworkforce.unc.edu/interactive/ supply/.

Medicaid enrollees living in rural parts of North Carolina generally have to travel much further for pregnancy-related care than those in urban areas. Maternity care units are often the first department that struggling rural hospitals cut, as they can be a drain on hospital finances. At least ten rural hospitals in North Carolina closed their maternity care units between 2013 and 2020.96 Pregnancy-related care in rural areas is relatively more expensive than in other areas since family physicians and hospitals that deliver babies in low-volume areas typically pay higher malpractice insurance costs and may be charged low-volume penalties.97

In North Carolina, some centers like Mission Hospital in Asheville are already serving as de facto hubs for the surrounding area, since it is a large hospital with the capacity to provide specialist care. However, “hubs” like Mission Hospital would benefit from financial support to cover the costs of coordinating care and ensuring effective communication and records sharing across different hospitals.98

Establishing a North Carolina hub and spoke model of care for SCD will improve access to care and outcomes for people living with SCD. Individuals, especially young adults, with SCD experience optimal care when their care plan is co-managed by a sickle cell specialist and primary care provider.99

Similar to SCD specialists in North Carolina, SCD specialists in South Carolina are often located in urban centers, while many patients and their primary care providers reside in rural regions.100 As a result, South Carolina has implemented a hub and spoke state network called (SC)2 The (SC)2 network utilizes the Lifespan Comprehensive Sickle Cell Clinic at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) as its hub, with spokes throughout the state in Beaufort, Columbia, and Georgetown.101 Lifespan is modeled off of New Mexico’s Project ECHO— originally a hepatitis C hub and spoke care model utilizing telementoring to train more frontline providers in specialty care—and applying it to the state’s SCD care network. Below is

Hub and spoke care models already exist in North Carolina, specifically to improve care for people with substance use disorders. In 2020, experts at Mountain Area Health Education Center (MAHEC) and UNC at Chapel Hill established a partnership to create a regional referral network.105 This hub and spoke model of care is funded by a $1 million, two-year grant, where the “hub” is the clinic with addiction specialists and the “spokes” are primary care providers and community health centers. The goal of this partnership is to address the challenges of sparse and fragmented addiction care across the state and “to create stronger connections between clinics that care for low-income people and experts at MAHEC and [UNC] so patients receive seamless care.”106

Similarly to caring for those with SCD or high-risk pregnancies, caring for patients experiencing addiction typically requires specialty care, yet there is a shortage of doctors who have the training and licensing requirements to prescribe addiction treatment medications. The medical director of Project CARA, a MAHEC program used to help pregnant women with opioid addiction, stated that “what makes the hub and spokes model work is the idea that it is alive and it is a network where the providers that deliver care have to understand and have relationships with each other.”107 Other states have also implemented the hub and spoke model to improve access to opioid treatment, including Vermont, New Hampshire, Washington and California.108

a description of how one “spoke,” Beaufort Memorial Hospital in (SC)2 operates. The SCD clinic at Beaufort Memorial Hospital:

• Is run by a full-time advanced practice provider, for example a nurse practitioner, trained by the hub;

• Provides care Monday through Friday;

• Serves 40 individuals with SCD in the Beaufort region;

• Offers transfusion therapy, hydroxyurea management, and acute pain management with individual care plans;

• Has local, emergency backup through the ED and hospitalist service;

• Provides care under the hub’s supervision, with check-ins as needed for patient-care issues;

• Has a supervising SCD provider from the hub utilize telemedicine to see patients remotely (on a scheduled and as-needed basis); and

• Has a supervising SCD provider travel from the hub to the spokes to provide patient care and assess new patients (on a quarterly basis).102

A hub and spoke model will improve access to care and health outcomes for enrollees living in rural areas of the state, where there are few (if any) maternal health providers. Hub and spoke models can achieve “Perinatal Regionalization of Care,” as recommended by CMS, which ensures that women have access to whichever providers can deliver risk-appropriate care. This approach has worked well in other states. For example, Avera Health in South Dakota has developed a system of connected rural hospitals that collaborate via “labor analysis software that supports providers in identifying risks and potential need for transfer during labor and delivery.”103

MUSC also operates a hub and spoke model by matching local pregnancy care providers with specialists to collaboratively manage care for women with high-risk pregnancies. In this program, women can meet simultaneously with their local provider and the specialist, who is

often located in a different part of the state, using telehealth. Telehealth-based hub and spoke models can work particularly well for providing mental health care, as in programs like “Lifeline4Moms” and Georgia’s “Live Health Online” programs.104

NC DHHS should convene a working group with two subcommittees—one for SCD and one for maternal health—including providers, enrollees, advocates, and PHP representatives to develop and publish best practice standards for rural providers that are interested in establishing or joining a hub and spokes system. NC DHHS should also provide some form of incentive and financial support for providers to cover the costs of creating a hub and spoke system in their region. This includes costs such as establishing sufficient telehealth capacity and managing data from different spoke providers’ medical records systems. This financial support could take several forms, including direct reimbursement from PHPs or a competitive grant program (run either by NC DHHS directly or by PHPs). To facilitate a hub and spoke model operation, NC DHHS should support telementoring directly or provide guidance to PHPs between specialists at hubs and providers at spokes throughout the state for utilizing telementoring. These reforms are relatively long-term solutions.

Implementation:

• NC Medicaid should apply for CMS approval to require or incentivize PHPs to offer ridesharing as a form of NEMT by partnering with companies like Uber or Lyft.

• NC Medicaid should offer competitive grants for PHPs to innovate in the NEMT market to provide expanded transportation options, specifically for rural enrollees where ridesharing-based NEMT is not a viable option.

Implementation:

• NC Medicaid should require PHPs and NEMT brokers to allow enrollees to bring their children, and possibly an adult attendant if needed, to their appointments in all cases.

Effective NEMT is critical for enrollees to access either SCD treatment or pregnancy-related care. In North Carolina, Medicaid covers transportation to appointments using personal vehicles, taxis, vans, mini-buses, mountain area transports, and public transportation. Since the transition to managed care, PHPs have each operated their own NEMT systems by contracting with brokers (including Modivcare and OneCall). PHPs may choose to offer additional transportation services, but they are not required or incentivized to do so. Healthy Blue offers all enrollees a $20 Uber gift

card each year.109 Complete Care provides $75 in annual “healthy rewards gift cards,” which can be used for transportation among other uses.110

Currently, all PHPs guarantee that enrollees who use NEMT will not have to arrive at their appointment more than one hour early and will not have to wait more than one hour after their appointment is done to leave.111 However, there are no limits on the amount of time transportation itself will take, as vehicle may pick up and drop off many other enrollees along the way. All PHPs guarantee enrollees that they will be informed about who is allowed to accompany them on NEMT without cost. PHPs allow caretakers and guardians to accompany enrolled children to their appointments. However, PHPs do not include any guarantee or guidance in their contracts, member handbooks, or other enrollee resources explaining their policy on children accompanying their parent to appointments for their parent’s care.112

In interviews, stakeholders reported that many enrollees do not view the current NEMT system as meeting their needs. In particular, enrollees struggle with the long wait times as their NEMT vehicle makes several stops to pick up other enrollees. Further, they often assume or are informed by the NEMT broker or driver that they cannot bring their children on NEMT if the medical appointment is for the parent’s care. This is particularly a problem for women who are breastfeeding, people with unpredictable and inflexible work schedules, and people who do not have stable child care.

A MACPAC focus group of Medicaid enrollees across the U.S. also found that “late pickups and driver no-shows are the primary reasons for complaints from [enrollees], providers, and care managers.”113 All of these issues can result in enrollees missing scheduled appointments. One of our interviewees noted that if the “no-show” rate becomes a major problem, some providers become reluctant to see Medicaid patients. This can further reduce access to necessary care.

Over 20 percent of state residents live in rural areas and coordinating care for this population can be especially challenging, particularly for individuals with complex health needs like pregnant and postpartum enrollees and enrollees living with SCD.114 Enrollees in rural areas have less access to public transportation, taxis, rideshare services, and other means of transportation than their urban and suburban counterparts. In interviews, stakeholders confirmed that challenges in accessing NEMT are exacerbated in rural areas.

Insufficient NEMT may lead to racial disparities, both in maternal health outcomes and outcomes for people with SCD compared to other enrollees. Black non-Hispanic Medicaid enrollees delay care due to transportation issues much more often than white non-Hispanic enrollees.115

Reimbursing ridesharing services as a form of NEMT is a promising approach that 18 states have incorporated into their Medicaid NEMT systems.116 This includes several large states with substantial rural populations, including Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Texas. Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) like Lyft and Uber have experience in the NEMT market since 2016 and 2018, respectively.117 Research on the success of rideshare-based NEMT is somewhat mixed, but several studies have found a positive impact on decreasing driver no-shows and late pickups, increasing customer satisfaction, and decreasing health care costs.118 A Lyft-sponsored study found that a Washington, D.C. program allowing Medicaid enrollees to use ridesharing to travel to prenatal appointments, urgent care, and appointment follow-up care led to a 12 percent drop in ambulance use and a 40 percent drop in emergency department use.119

Rideshare-based NEMT does not need to be scheduled as far in advance as traditional NEMT services, which may improve convenience of use for enrollees. Additionally, Medicaid enrollees do not need a smartphone or the Uber/Lyft apps to use rideshare-based NEMT, as they can access service through a simple text message-based system. This may increase access for people who are low-income and may not be able to afford to maintain a phone data plan.

Ridesharing-based NEMT may improve access to care for urban and suburban enrollees, but it is likely not a viable option for rural residents. NC DHHS could offer competitive grants for PHPs to innovate in the NEMT market to provide expanded transportation options, specifically for rural enrollees.

Several states have experimented with tailoring NEMT to better serve pregnant and postpartum Medicaid enrollees. In 2019, Texas started a pilot program to provide NEMT dedicated only to transporting pregnant and postpartum women and their children to appointments, without sharing the vehicle with other enrollees.120 Georgia allows pregnant and postpartum women to bring their children on NEMT for their mother’s appointments, whereas other enrollees are only allowed to bring an escort that provides medically-necessary assistance to the patient.121

Rideshare-Based NEMT

NC Medicaid should require or incentivize PHPs to offer ridesharing as a form of NEMT by partnering with companies like Uber or Lyft. Alternatively, NC Medicaid could require all PHPs to incorporate some form of ridesharing as a value-added service. Additionally, NC Medicaid should offer competitive grants for PHPs to innovate in the NEMT market and offer expanded transportation options for enrollees. This is a relatively short-term solution which can be implemented by updating PHP contracts.

NC Medicaid should require PHPs to provide NEMT tailored specifically to pregnant and postpartum women. Specifically, NC DHHS should require PHPs and NEMT brokers to allow enrollees to bring their children, and possibly an adult attendant if needed, to their appointments in all cases. This policy should be clearly communicated to enrollees. For an approach even more tailored to pregnant and postpartum women, NC Medicaid could require or incentivize PHPs and their NEMT brokers to provide a dedicated vehicle to transport groups of pregnant and postpartum women directly to their appointments without waiting for other enrollees to complete their appointments. This is a relatively short-term solution which can be implemented by updating PHP contracts.

Implementation:

• NC DHHS should convene a working group to recommend an approach for expanding and improving implicit bias training.

Implicit bias in the health care system is a serious barrier for patients of color receiving the care they need. Although the state already requires PHP staff to undergo equity and implicit bias training, stakeholder interviews revealed that implicit bias training is a critical need for North Carolina.122

The North Carolina Institute of Medicine’s 2020 “Healthy Moms, Healthy Babies” report, which proposed recommendations to reduce infant and maternal mortality and morbidity in the state and address racial disparities, discussed implicit bias as a key factor that contributes to health disparities. Similarly, a needs assessment survey of ED providers in North Carolina on barriers to care for people with SCD revealed that nearly 40 percent of ED providers identified implicit bias as a barrier.123

Research has shown that Black patients have lower levels of trust in the health care system due to experiences with biased providers and historical racist practices.124 Distrust in health care is associated with lower rates of recommended disease prevention and treatment of acute and chronic illness, as well as worse health status.125 It is crucial that providers

NC DHHS should expand and improve its implicit bias training requirements to include perinatal and SCD providers.

understand this context and develop strategies for building trust and communicating across lines of difference.

In SCD care, implicit racial bias leads to negative interactions with providers, longer ED wait times during pain crises, and restricted access to adequate pain management.126 Racial bias also prevents patients with SCD from accessing opioids essential for pain management.127

Providers are more likely to suspect that Black patients and patients with SCD are addicted to opioids and engage in drug-seeking behavior than white patients and patients with non-SCD chronic conditions, even though rates of opioid use among patients with SCD did not rise while opioid use was accelerating in the general population.128 Patients with SCD report that opioid stigma has made providers more likely to underestimate and undertreat their pain.129

Implicit racial bias can lead to negative maternal and child health outcomes for Black women, as they are less likely to receive prenatal education resources.130 Bias can contribute to Black mothers’ risk of serious pregnancyrelated conditions like postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia, as their concerns are often overlooked and ignored by health care providers.131

Several states including California, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, and New Jersey require some form of bias training for health care providers by law.132 California specifically requires hospitals that provide pregnancyrelated care, alternative birth centers, and certain primary care clinics to establish an

“evidence-based implicit bias program” that covers unconscious biases, strategies to communicate across different identities, and maternal health inequities, among other topics.133

It is difficult to estimate the impact of bias training programs because outcomes are hard to quantify.134 However, researchers have developed a series of best practices based on provider feedback. Providers reported that shorter trainings would be most effective, and that modules should be easy to divide into multiple sessions to fit into physicians’ busy schedules. Training courses should be available for free or at a low cost to low-resource hospitals.135 Ideally, Medicaid enrollee advisory boards or patient focus groups should inform the creation of training materials.

NC DHHS should establish a working group to investigate best practices to improve implicit bias training. The working group could consider recommending or requiring provider participation in the Carolina Global Breastfeeding Institute’s ENRICH program, which offers maternal healthfocused provider bias training, or the perinatal provider-focused, evidence-based training model developed by Diversity Science.136

Although SCD-focused bias training has yet to be implemented, NC DHHS can look to states like Michigan, which requires bias training for health care providers writ large for initial licensure or registration and renewal under the Michigan Public Health Code, for examples of bias training content and implementation strategy.137

These are relatively medium-term reforms. because NC DHHS already requires PHP staff to engage in some degree of bias training. The best practices the working group formulates for providers can be implemented quickly.

NC DHSS should increase resources in NCCARE360 and CBOs to ensure their ability to address non-medical drivers of health.

Implementation:

• NC DHHS should increase advertising and communication to community-based organizations on NCCARE360.

• NC DHHS should invest in technical assistance and resources to communitybased organizations to incorporate NCCARE360 into their practice.

• NC DHHS should set a community reinvestment requirement for PHPs.

Many North Carolinians face conditions including food insecurity, housing instability, unmet transportation needs, and interpersonal violence, all of which impact their health and well-being. More specifically, over 1.2 million North Carolinians cannot find affordable housing; the state has the eighth highest rate of food insecurity; 47 percent of North Carolina women experience intimate partner violence; and nearly a quarter of North Carolina children have experienced adverse childhood experiences.138 Screening and identifying these unmet needs provide opportunities for intervention, to improve health outcomes and to generate cost savings.

NC Medicaid is a leader in the country in its effort to integrate non-medical drivers of health into models of care. The state has taken several initiatives to address non-medical drivers, including creating a set of nine standard screening questions for providers to determine if Medicaid enrollees face barriers related to transportation, food, housing, or interpersonal safety and developing Healthy Opportunities

to improve screening for social needs, care coordination, and the provision of non-medical services to its Medicaid population.139

Furthermore, the state has created a statewide platform called NCCARE360, where providers can refer and connect patients to community-based organizations (CBOs). The coordinated care network was launched in 2019 and now boasts over 1,000 CBOs that connect people to resources they need in all 100 counties.140 However, one challenge has been a lack of widespread use of NCCARE360 by health care providers and community-based organizations.141 Stakeholder interviews indicated a need for greater awareness of NCCARE360 across provider networks as well as greater organizational capacity to implement it. CBOs cited a lack sufficient staff and technical training to implement NCCARE360 at a larger scale.

The effectiveness of these programs to connect people to local services depends heavily on CBOs’ resources and ability address people’s needs. The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted nonprofits in the state; 87 percent of nonprofits report lower than usual revenue and 77 percent report higher demand than usual for services.142

Non-medical drivers of health are particularly important for people with SCD, who are more likely to experience structural barriers and racial disparities that exacerbate the physical and behavioral health challenges associated with SCD and result in worse health outcomes.143 A study examining universal screening for social determinants in patients with SCD in a pediatric hematology clinic at the Boston Medical Center found that 66 percent of patients screened positive for at least one unmet socioeconomic need with an average of 2.1 unmet needs per patient (among patients with unmet needs). The most common unmet need was food insecurity, followed by difficulty paying utilities, a desire for more education, unemployment, transportation, housing, and childcare.144 The same study found that patients were proactive after being referred

to community organizations, with 45 percent reaching out to resources within two weeks, demonstrating the benefits of a screening and referral program for people with SCD.

Similarly, for pregnant and postpartum women with Medicaid, non-medical drivers of health can affect health outcomes. A study found that attending fewer than 10 prenatal appointments and having preexisting conditions, such as obesity or diabetes, were significantly associated with maternal mortality.145 Non-medical factors, such as lack of transportation or lack of healthy foods, inhibit access to prenatal care and contribute to adverse risk factors such as obesity and diabetes. Screenings and referrals have shown promise in improving health outcomes for pregnant and postpartum women. For example, women referred to and participating in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits have a reduced likelihood of pregnancy-related ED and lower rates of preterm births.146 Additionally, screening for domestic violence among pregnant women increased identification of and interventions for domestic violence.147