BEHAVIORAL INSIGHTS TO

PROMOTE DEMAND FOR COVID-19 VACCINES IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

PROMOTE DEMAND FOR COVID-19 VACCINES IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

Zainab Amjad specializes in international development with a focus on urban policy. Prior to Princeton, she worked as a development consultant with Delivery Associates, supporting sanitation reform with the government of Pakistan, implementation of reforms for Vision 2030 with the government of Saudi Arabia, and education reforms at the Prime Minister’s office in Saint Lucia. At Princeton, Zainab has taken courses in urban policy and public health, while deepening her skills in spatial analysis and econometrics.

Chloe Cho specializes in economics and public policy, with a focus on public finance and international development. Prior to Princeton, she worked as a research analyst at the International Budget Partnership, conducting cross-country analyses of budget deviations. Previously, she worked at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Verité Research, analyzing budget, tax, trade, and other government policies in the United States and Sri Lanka.

Jack Diao is a CPA who has held progressive positions at the federal level, where he oversaw $400M+ in spending for large-scale publicprivate partnership infrastructure projects. He has also held numerous policy dialogues, engaging stakeholders at all levels. He has also worked for the World Bank in researching policies enabling resilient growth and green private sector development, as well as led fiscal and public finance reforms to improve the efficiency and collection of tax systems. Speaking Spanish, French, and Mandarin, Jack hopes to continue working in international economic development.

Eunji Kim is a journalist by training and worked as a radio producer at Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) in Seoul prior to Princeton. She has produced documentaries, talk shows, and news programs, covering South Korea’s politics, history, culture, and society, that reached audiences worldwide. At Princeton, she is focusing on international relations and international development with a concentration on environmental policy.

McKenzie Leier is a fourth-generation North Dakotan who grew up with the extraordinarily flat land of the Red River Valley in her backyard. McKenzie completed a Fulbright fellowship in Malaysia and has worked for the Iowa Department of Public Health and Boston Children’s Hospital. Most recently, she worked as a project manager for Partners in Health’s U.S. COVID-19 response. At Princeton, she is focusing on global health and development.

Nash Mepukori is a global health advocacy, communications, and policy specialist, passionate about strengthening health systems in emerging economies to improve wellbeing. Working at the intersection of global health practice and policy, her expertise lies in driving outcomes on key health issues, including maternal and newborn survival, reproductive health, immunization, universal health coverage, and health financing. She has worked closely with Ministries of Health, private sector, civil society, and development partners in East and Southern Africa, India, and the United States.

Caitlin Quinn previously worked for the federal government on the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the State Department's Office of Central American Affairs as a Scholars in the Nation's Service Initiative (SINSI) graduate fellow. Most recently, she worked on systemic police reform efforts at the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice. At Princeton, she is focusing on both foreign and domestic policy.

Nausheen Rajan worked as a Senior Associate in the Asia Regional Business Unit at Chemonics International, where she provided project management and business development support for USAID-funded projects, before Princeton. Previously, she has engaged with issues at the intersection of foreign affairs and economic development through work with the United States Department of State, think tanks, and initiatives that have built the capacity of women to create, sustain and scale their businesses in Pakistan. At Princeton, she is focusing on international development and urban policy.

This report was prepared by second-year Master in Public Affairs students at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs. The authors would like to thank the many experts who lent their time and knowledge to our group. We are especially grateful to our professor, Varun Gauri, for sharing his behavioral science expertise and guiding us in creating this report. Finally, we would like to thank the Mind, Behavior, and Development (eMBeD) Unit at the World Bank for their partnership and guidance. Any errors in the report should be attributed to the authors, not the experts listed below. We hope that this report will be useful to the eMBeD team and make a small contribution to the understanding of vaccine hesitancy.

Specifically, we would like to thank:

Zeina Afif Senior Behavioral Scientist, eMBeD Unit, World Bank

Thomas Black Senior Program Officer, Global Delivery Programs, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Katherine E. Bliss, Ph.D. Senior Fellow and Director, Immunizations and Health Systems Resilience, Global Health Policy Center, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS)

Corey Morales Cameron Consultant, eMBeD Unit, World Bank

Sergio Cecchini Infodemic Management Officer, Africa Infodemic Response Alliance Coordinator, World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa (WHO AFRO)

Alin Coman, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Princeton University

Christopher Giles Researcher, Stanford Internet Observatory

Shelby Grossman, Ph.D. Research Scholar, Stanford Internet Observatory

Ellen Elizabeth Moscoe, Ph.D. Behavioral Scientist, eMBeD Unit, World Bank

Ifeanyi Nsofor, M.D. Public Health Physician; Senior Atlantic Fellow for Health Equity, George Washington University; Director of Policy and Advocacy, Nigeria Health Watch

Victor Hugo Orozco-Olvera, Ph.D. Senior Economist, Development Impact Evaluation (DIME) group, World Bank

Joachim Osur, Ph.D. Vice Chancellor, Amref International University

Jeff Pituch Senior Consultant, DevGlobal

Justin Sandefur, Ph.D. Research Fellow, Center for Global Development

Sema Sgaier, Ph.D. Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Surgo Ventures

Jana Smith Managing Director, ideas42

Morgan Wack Doctoral Candidate, University of Washington Department of Political Science

This report, prepared for the Mind, Behavior, and Development (eMBeD) Unit at the World Bank, applies a behavioral science lens to analyze the impact of misinformation on COVID-19 vaccine demand, with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa.

Based on our review of the relevant literature, we find five major thematic enablers of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: 1) health concerns and risk perceptions, 2) low trust in institutions, 3) automatic thinking and heuristics, 4) social processes, and 5) cultural and religious beliefs. Given time and resource constraints, we were unable to conduct primary research for this report. As a result, we relied on other scholars’ work on diagnosing vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa to draft our original diagnostic questions.

For each of the five enablers of vaccine hesitancy, we propose interventions tailored to the eMBeD team’s needs, meaning that most of these interventions take place online. We suggest social media advertisements, most of which are customized to persona type, WhatsApp chatbots, and interactive games based on inoculation theory. In addition to these online interventions, we propose several in-person interventions based on our findings about social norms, cultural and religious beliefs, and automatic thinking.

Just days before the Omicron variant was first detected in sub-Saharan Africa in November 2021, South Africa made global headlines by asking Johnson & Johnson and Pfizer to delay scheduled COVID-19 vaccine shipments. Demand for the vaccines had slowed, and officials were worried that additional doses might expire before they could be used. The situation in South Africa demonstrated that while supply-side issues have been the preeminent roadblock to widespread vaccination thus far for sub-Saharan Africa, vaccine hesitancy is emerging as another significant barrier to vaccinating the region.

As of December 2021, over 290 million cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed worldwide, and over 5 million people have died of COVID-19.1 Despite having fewer public health resources compared to the rest of the world, Africa has been perhaps the least affected region in the world (with the notable exception of South Africa). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Africa accounts for just 4% of the world’s COVID-19 infections and just 3% of the world’s total deaths from COVID-19.2 By contrast, roughly 18% of the world’s population lives in Africa.3 These low case rates suggest that much of Africa’s population remains susceptible to the virus.

As of December 2021, 56% of the world’s population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, but differences in regional vaccination rates

are stark. Whereas 72% of those in the United States and Canada have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, only 11% of their African counterparts have done the same.4

While developed countries initially monopolized the supply of COVID-19 vaccines, availability has increased in developing countries in recent months. However, misinformation threatens to impede vaccination efforts by fueling hesitancy and outright hostility toward the vaccines. As internet and social media use have become more widespread across the globe, people increasingly turn to online sources to stay informed and communicate with one another. Information is circulated throughout society more rapidly and in greater quantities than ever before. As a result, COVID-19 misinformation has proliferated on social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp across the world.5 Moreover, multiple studies have shown that exposure to misinformation through nontraditional media sources—especially social media—has been linked to reduced vaccine acceptance.6 From these results, it is clear that misinformation may have deleterious effects on vaccination rates and public health.

In sub-Saharan Africa, multiple studies have shown that COVID-19-related misinformation has proliferated in the region and fueled concerns about COVID-19 vaccines. For example, in a 2021 study by the African Union and

the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), data was collected from over 15,000 individuals in 15 African countries, including 13 in sub-Saharan Africa. Two-thirds (66%) of respondents reported being exposed to “some” or “a lot” of misinformation.7 The researchers found that respondents “who self-report exposure to rumors also show a higher propensity to believe them.”8 The study also found that nearly half of respondents believed that COVID-19 is a planned event by foreign actors, and that online sources, particularly social media, tend to be the most trusted source of information among vaccine-hesitant individuals.9

Another 2021 study by Afrobarometer surveyed a representative sample of 6,000 individuals in five West African countries and found that only four in 10 people said they would be likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine.10 Similarly concerning results were reported in a study of South Africa and Zimbabwe, two of the first sub-Saharan African countries to receive COVID-19 vaccines.11

While a substantial portion of COVID19-related misinformation is not based in truth, it is important to note that

vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa is often grounded in actual events. Historically, people in colonial Africa were victims of unrestricted medical experimentation, with little to no oversight or accountability. For example, as late as 1955, a prominent British physician at Oxford University stated enthusiastically: “[I]t is the almost unlimited field that Africa offers for clinical research that I find so enthralling.”12 In a more recent example, a 1996 Pfizer meningitis drug trial in northern Nigeria killed 11 children and generated lasting distrust of vaccines within and beyond the region.13

In light of the proliferation of online COVID-19 misinformation and the evidence that misinformation reduces vaccine acceptance, this report seeks to offer behavioral insights to promote demand for COVID-19 vaccines in subSaharan Africa. We analyze the issue of online misinformation as a potential driver of vaccine hesitancy, summarizing the literature, proposing diagnostics, and suggesting interventions.

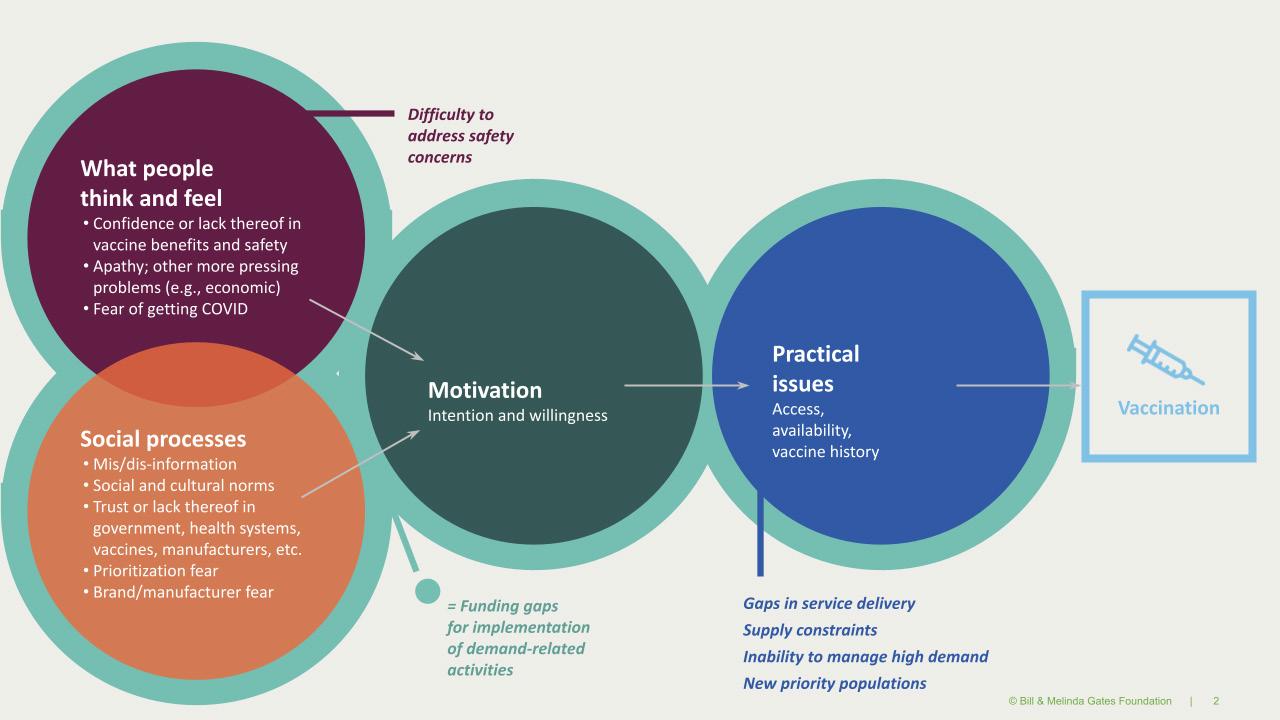

In this report, we focus on the impacts of COVID-19-related misinformation on vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa. However, the broader issue of vaccine uptake in sub-Saharan Africa is significantly more complex. Much of the literature we review focuses on individuals’ thoughts and feelings about vaccines, but as Brewer et al. note in their 2017 review paper, “few randomized trials have successfully changed what people think and feel about vaccines, and those few that succeeded were minimally effective in increasing uptake.” They elaborate: “Interventions appear to be able to increase vaccine confidence, but the impact of increased confidence

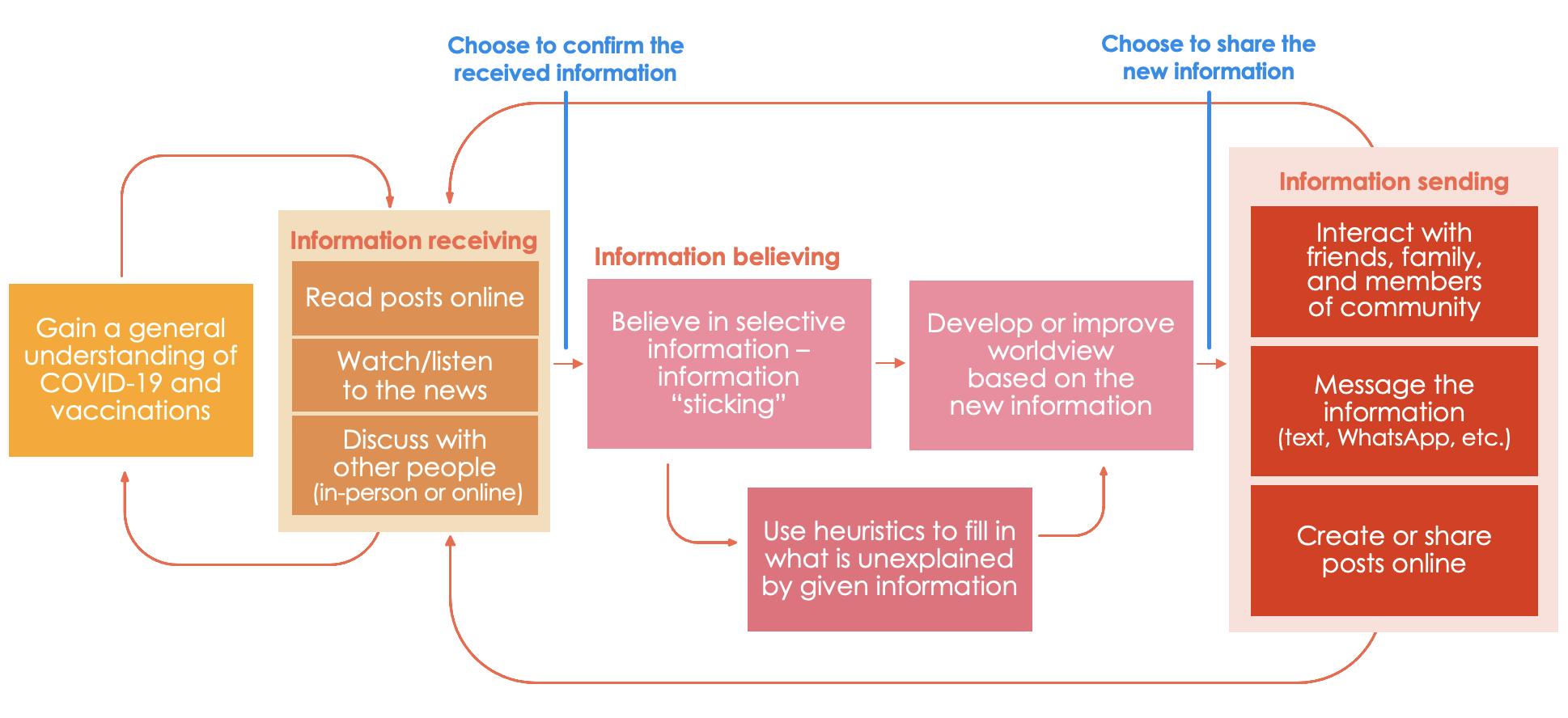

on uptake is unknown.”i This insight was echoed by public opinion researchers from the Gates Foundation, who noted that although the causal link between exposure to COVID-19-related misinformation and reduced vaccine uptake may seem intuitively obvious, it has yet to be empirically proven in the existing literature.ii Research from Goldstein et al. in Nigeria found no relationship between overall belief in misinformation and willingness to be vaccinated among a group of urban, middle-class Nigerians.iii The figure below shows how people’s thoughts and feelings about vaccines may contribute to their choice to get vaccinated.

According to Brewer et al., the available evidence (as of 2017) on using behavioral science interventions to increase vaccination suggests that the most effective interventions focus not on individuals’ thoughts and feelings, but rather on reducing barriers and directly facilitating action. In terms of reducing barriers, Brewer et al. list a number of obstacles individuals may face when seeking to get vaccinated: lack of reliable transportation or childcare, inconvenient clinic opening times, language barriers, and cost (even if a vaccine is “free,” the opportunity cost of missing wages can be steep). Interventions meant to reduce these barriers might include setting up mobile vaccination clinics or using defaults. An example of default-setting is presumptively scheduling people for vaccine appointments and giving them the option to reschedule or cancel their appointment by phone, which had a significant effect on vaccine uptake in one randomized trial.iv

In terms of directly facilitating action, Brewer et al. emphasize that even people who are favorably inclined toward vaccination often fail to follow through on their intentions to get vaccinated,

which implies that interventions meant to close the intention-action gap can help increase uptake. The authors cite studies finding that telephone reminder/recall systems worked well in this respect, and that such reminders were most effective when managed by a centralized health institution and endorsed by patients’ providers. Healthcare provider recommendations and presumptive announcements have also been shown to be effective at increasing vaccination, especially among hesitant individuals: “By framing vaccines as routine care, presumptive announcements speed the decision process for people with positive vaccination intentions. For people who are hesitant or opposed to vaccination, the process will slow down, allowing them to ask questions and the provider to ease their concerns.”v Finally, using incentives, such as rewards for getting vaccinated or penalties for remaining unvaccinated, and vaccine requirements can be effective interventions, but the authors caution: “[D]epending on the prevailing reasons for undervaccination in a population, it may be sufficient or more advisable to apply other less coercive measures.”vi

i Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Rothman, A. J., Leask, J., & Kempe, A. (2017). Increasing Vaccination: Putting Psychological Science Into Action. Psychological science in the public interest: a journal of the American Psychological Society, 18(3), 149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100618760521

ii Black, T. & Pituch, J. (2021, October 22). Personal communication [Zoom interview].

iii Goldstein, J.A., Grossman, S., & Startz, M. (2021, October). Belief in COVID-19 Misinformation in Nigeria. Manuscript under review. Abstract available at: https://www.sites.google.com/site/shelbygrossman//papers/

iv Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Rothman, A. J., Leask, J., & Kempe, A. (2017).

v Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Rothman, A. J., Leask, J., & Kempe, A. (2017).

vi Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Rothman, A. J., Leask, J., & Kempe, A. (2017).

To effectively mitigate the potential consequences of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy caused by misinformation, we must first clearly define the problem. Put simply, misinformation is any content that is false or misleading.i Key features include unverified or false content, information shared with no background context, conspiracy theories, and poor quality content, regardless of source.ii Misinformation can also take subtler forms, such as content that is only partially accurate, or that contains plausible-sounding half-truths. In the context of COVID-19 vaccines, misinformation often comes from hearsay or news stories from unverified or unreliable sources, as well as from social media through one’s social circles.iii

The WHO has stated that rumors and conspiracy theories online continue to undermine pandemic response efforts, and that social media is often a vector

of misinformation.iv In addition, it has become increasingly clear that some parties are deliberately proliferating false narratives to cause discord and to discredit public officials for political gain.v,vi Here, it is important to note a distinction: whereas misinformation simply contains falsehoods regardless of source or intention, disinformation is a subset of misinformation that involves deliberately spreading fake news for purposes such as attempting to sway public opinion or diminish public trust. Disinformation is spread online by both foreign and domestic actors, often for political reasons. Empirical studies have shown a significant link between foreign disinformation campaigns and vaccine hesitancy.vii Regardless of the type of misinformation, our goal is to gauge the impact of misinformation-related vaccine hesitancy and devise strategies to combat it.

i Vraga, E., & Bode, L. (2020). Defining Misinformation and Understanding its Bounded Nature: Using Expertise and Evidence for Describing Misinformation. Political Communication. 37(1), 136-144. https://doi.org/10. 1080/10584609.2020.1716500

ii WHO & Pan-American Health Organization. (2020). Understanding the infodemic and misinformation in the fight against COVID-19: Digital Transformation Kit, Knowledge Tools.

iii Alaoui, S. (2020). Immunizing the public against misinformation. United Nations Foundation.

iv WHO & Pan-American Health Organization. (2020).

v Bliss, K.E. & Morrison, S.J. (2020). The Risks of Misinformation and Vaccine Hesitancy within the Covid-19 Crisis. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

vi Tagliabue, F., Galassi, L. & Mariani, P. (2020). The “Pandemic” of Disinformation in COVID-19. SN Comprehensive Clinical Medicine, 2, 1287–1289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00439-1

vii Wilson, S.L., & Wiysonge, C. (2020). Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Global Health, 5(10). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004206

What are the best methods for measuring online misinformation? In this box, we briefly review some techniques used in the literature and offer some of our own.

We can measure COVID-19-related misinformation and vaccine hesitancy in terms of people’s exposure to misinformation (whether they have heard of different misinformation narratives or conspiracy theories); their stated beliefs in misinformation or conspiracy theories (whether they believe misinformation); and their behavior when it comes to sharing that misinformation (whether they forward, repost, or otherwise spread misinformation narratives online).

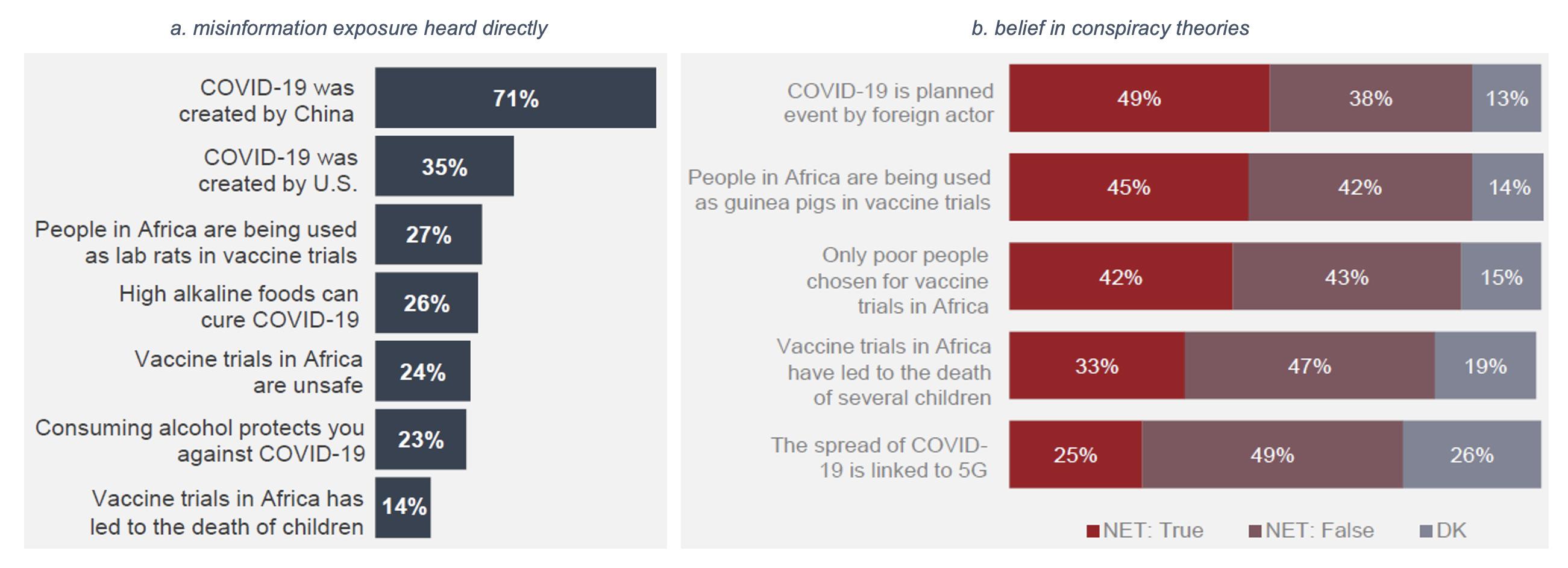

The 2021 Africa CDC study surveyed people about whether they had heard of popular but false narratives

surrounding COVID-19 and vaccines, as well as the extent to which people believed this misinformation. In all parts of the continent studied except West Africa, online sources were the most popular sources of information, with social media comprising a significant proportion. Demographically, men (44%) and young people between the ages of 18 and 24 (51%) were on average more likely to report getting their information from online sources, including social media platforms like WhatsApp. Furthermore, those more susceptible to misinformation were also more likely to rely on online sources and to trust social media as their main source.i

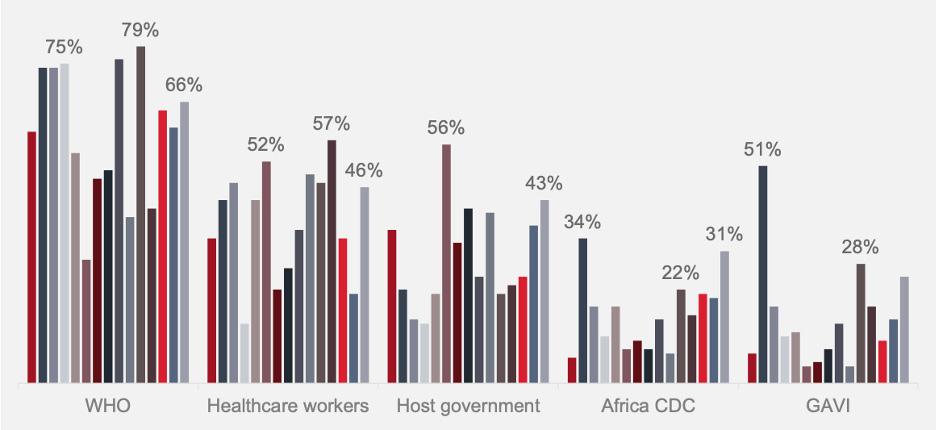

The survey found that there has been widespread exposure to conspiracy theories, as well as a sizable minority who believe in them (Figure 1.2).

Source: Africa CDC. (2021).

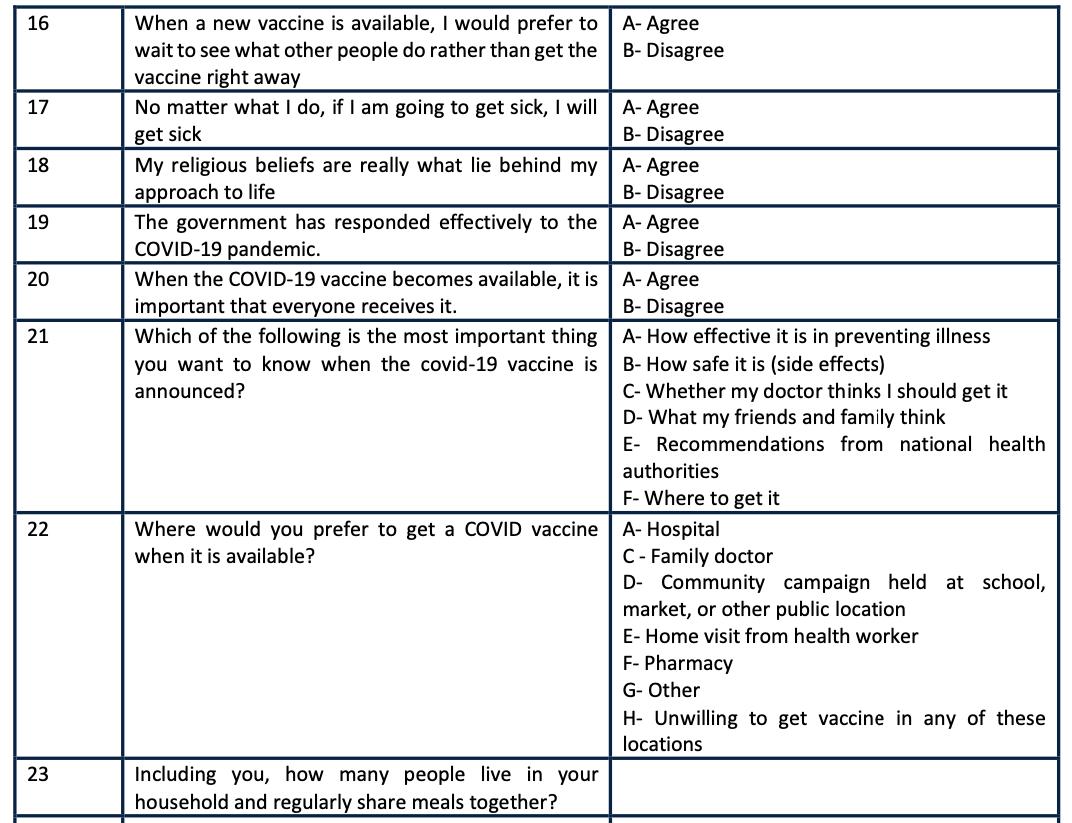

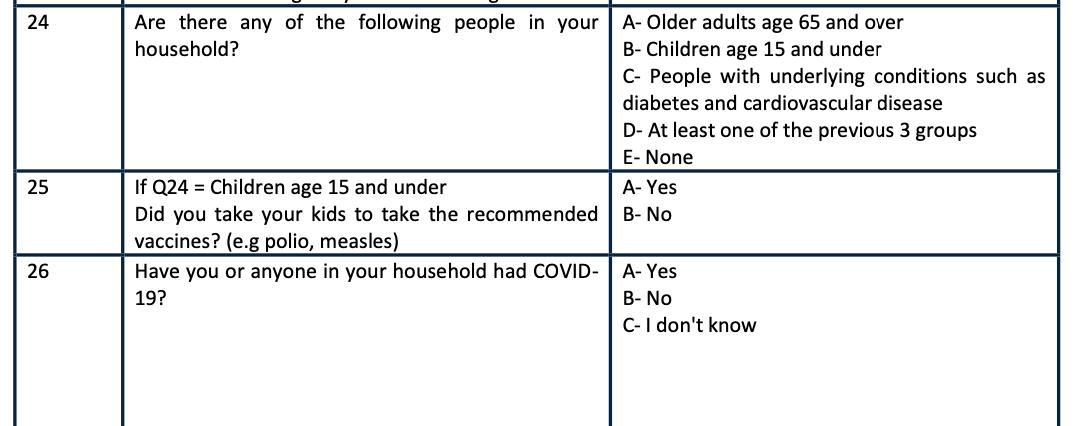

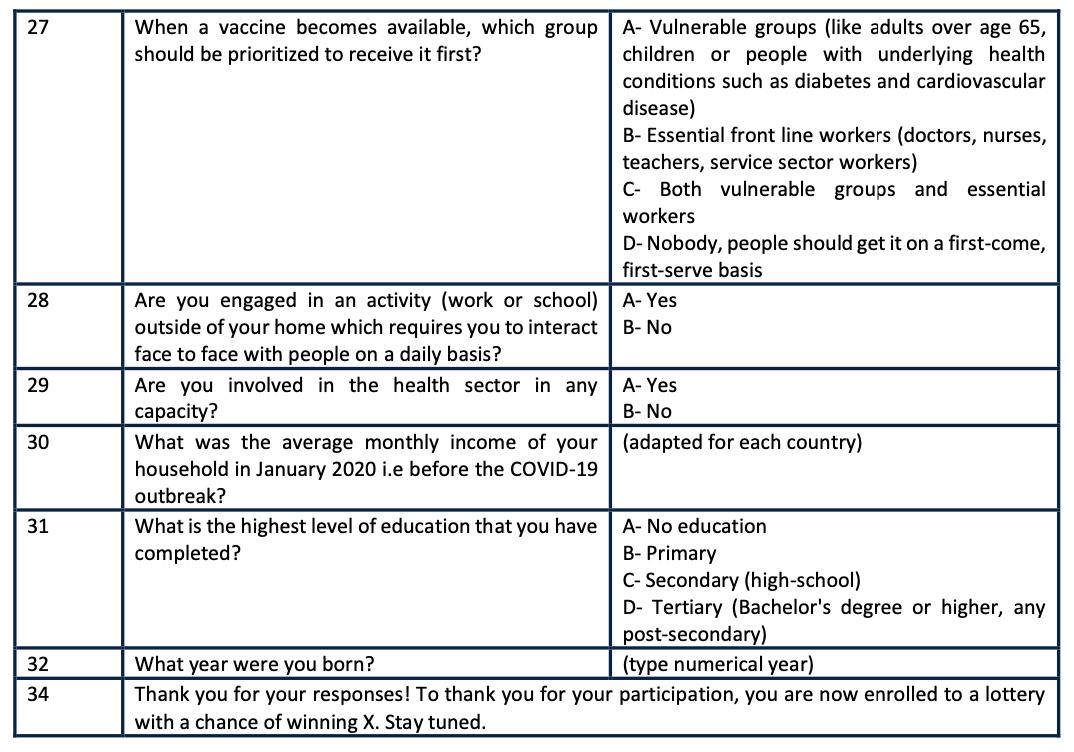

Thus, by surveying people about their exposure to different conspiracies, researchers can gauge the relative popularity of different misinformation narratives. Furthermore, asking whether people believe those narratives can help researchers estimate the potential impact that misinformation has on people’s opinions of the vaccine. Similar to the method followed by Schmelz and Bowles, survey questions could ask about respondents’ beliefs, their willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, and whether or not they are aware of popular misinformation in circulation.ii Surveys should also measure demographic characteristics such as age, education level, vaccination status, and attitudes toward COVID-19

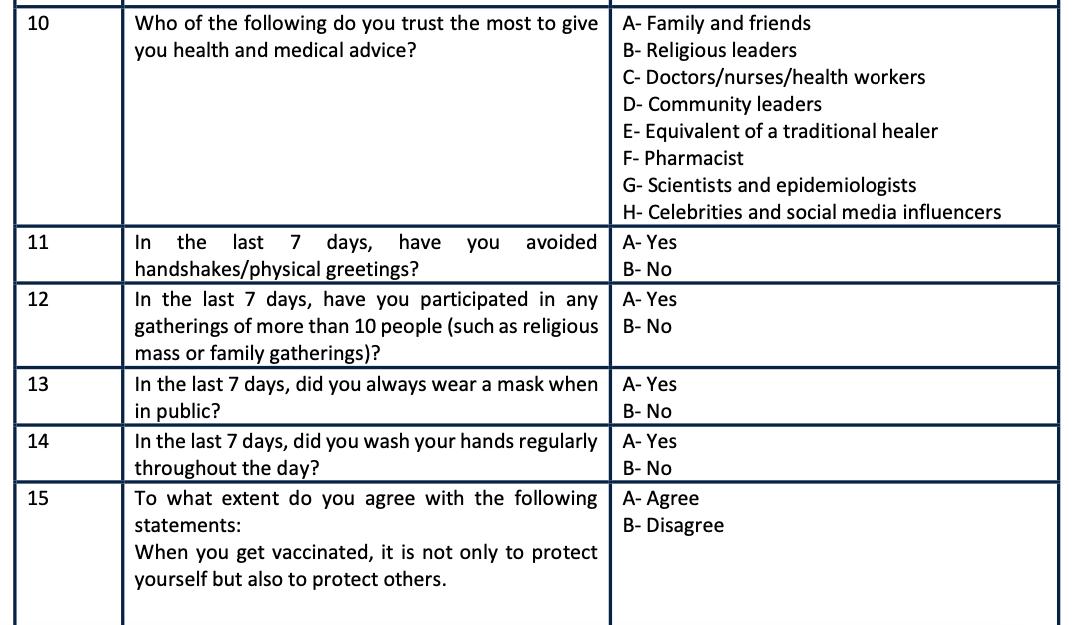

vaccines, thereby allowing researchers to study trends across demographic and other characteristics. The table below outlines some questions researchers can use to measure misinformation.

Using the questions and metrics in the table below could help researchers evaluate how many or what percentage of people believe misinformation, social norms around belief in misinformation, and individuals’ attitudes toward vaccination. If a particular population segment exhibits both high hesitancy and high rates of belief in misinformation relative to other groups, then they could be targeted for further study and, if feasible, intervention.

Exposure Average agreement/exposure rate (%) to misinformation

Beliefs Average agreement rate (%), supporting misinformation

How strongly beliefs are held about certain pieces of misinformation

Social norms around belief in misinformation

Average agreement rate (%), misinformation-associated hesitancy

Vaccine uptake rates or vaccination status (%)

Have you heard of [Conspiracy X]?

Do you believe [Conspiracy X] is true?

How confident are you in your belief that [Conspiracy X] is true?

Do you feel that this belief is accepted in your community?

Given what you heard, are you hesitant to get a COVID-19 shot?

Have you had the vaccine? If not, do you support it?

Source: Princeton team.

i Africa CDC. (2021, March). COVID 19 vaccine perceptions: A 15 country study. African Union. https:// africacdc.org/download/covid-19-vaccine-perceptions-a-15-country-study/ ii Schmelz, K. & Bowles, S. (2021, June). Overcoming COVID-19 vaccination resistance when alternative policies affect the dynamics of conformism, social norms, and crowding out. PNAS, 118(25). https://doi. org/10.1073/pnas.2104912118

We conducted our literature review using a snowball approach. Our team reviewed over 60 scientific publications on misinformation and public health related to COVID-19 and other infectious diseases. The most relevant of these publications are discussed below, and detailed information on 36 of our source articles can be found in a separate attachment. In addition, we have consulted researchers and practitioners in the fields of medicine, health policy, misinformation, behavioral science, and international development. Our interviewees hail from institutions including the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Stanford University, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and are listed in our Acknowledgments.

In this section, we review literature on the processes, mechanisms, and beliefs that enable two related behaviors that we seek to disrupt. The first behavior is believing misinformation about COVID-19 encountered online. The second is sharing that misinformation with others. By examining the factors that enable these behaviors, we hope to assist the eMBeD team in diagnosing the sources of vaccine hesitancy in various contexts and, in turn, identifying

opportunities and methods for intervention. We have identified five enablers of misinformation belief and sharing behaviors:

• Health concerns and risk perceptions

• Low trust in institutions

• Automatic thinking and heuristics

• Social processes

• Cultural and religious beliefs

In addition, understanding the particular underlying drivers of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among various populations in sub-Saharan Africa is critical to intervention design. High-quality diagnostics can provide insights into locally and demographically specific COVID-19 vaccine attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. Practically, conducting diagnostics involves use of diverse tools, including surveys, face-to-face interviews, observational data, and data on demographics, service use, problem or issue tracking, and epidemiology.14 Data should ideally be collected frequently and on an ongoing basis, given the rapid evolution of the pandemic and hesitancy patterns. For example, the Johns Hopkins COVID Behaviors Dashboard, which presents data from global surveys of COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and practices, is updated on a bimonthly basis.15 Additionally, data from 343 (and counting) quantitative studies conducted globally is aggregated on the Risk Communication and Community

Engagement platform and updated monthly.16 While diagnostics can shed light on which interventions are likely to be most effective in preventing certain groups from believing and sharing misinformation, it is crucial to take note of the regional diversity in sub-Saharan Africa and differences among countries that may not be fully captured by the studies and surveys presented in this section.

Among the most prevalent enablers of vaccine hesitancy in sub-Saharan Africa are concerns about health and safety. These concerns can distort individuals’ perceptions of the potential risks and benefits of getting vaccinated against COVID-19. As Brewer et al. explain, multiple factors influence an individual’s vaccination decision. Examples include the perceived likelihood of getting infected; the perceived severity of the disease if one does get infected; and affective risks such as worry, anxiety, and fear.17

With regard to the perceived likelihood of getting infected, research suggests that a combination of true information and misinformation has led many Africans to underestimate the risk that COVID-19 infection poses to people in sub-Saharan Africa. It is true that, while countries like the United States, Brazil, and much of Western Europe were devastated in the early months of the pandemic, Africa was largely spared. As Dzinamarira et al. explain, “The low effect at a personal level of COVID-19 in its first wave in Africa contributed to a widespread belief that COVID-19 is overwhelmingly not an African

problem.”18 South Africa, of course, has been a notable exception to this trend. Unfortunately, the disease’s lack of early penetration in most of sub-Saharan Africa has fueled myths that threaten the success of vaccination efforts in the region. These myths include that COVID-19 only kills non-Africans; that it does not affect young people; and that traditional African remedies work as well as or better than vaccines to prevent COVID-19.19 Researchers from the Africa Center for Strategic Studies have emphasized the need to tackle these myths directly: “Restoring trust in the COVID vaccine campaign will require pushing back against vaccine myths and creating an environment of people-centered, transparent, and inclusive vaccine outreach.”20

Besides misinformation, a lack of information also appears to be contributing to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. In a 15,000-person, 15-country survey conducted between August and December 2020 by the African Union and the Africa CDC, over half of respondents considered themselves either “not very well” or “not at all” informed about the development of COVID-19 vaccines.21 Individuals who are not well informed about the vaccines’ development may be more susceptible to misinformation narratives that contradict the overwhelming scientific evidence that COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective. Consequently, a lack of accurate information about the vaccines can lead people to make vaccination decisions based on misleading narratives that portray the vaccines as unnecessary or even harmful. Unsurprisingly, beliefs about the vaccines’ safety are closely correlated with vaccination intentions: in the Africa CDC survey, among respondents who indicated they would

reject the vaccine, 60% said they believed it was not safe, compared to 16% of those who intended to accept a vaccine.22

Concerns about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines tend to be rooted in a combination of true and false information. In addition to the aforementioned 1996 Pfizer drug trial in northern Nigeria that killed 11 children, the temporary pause of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine in several European countries following reports of a rare but serious blood-clotting side effect caused lingering doubts about the vaccine’s safety among many Africans.23 Unfortunately, misinformation about the purported health risks of COVID-19 vaccines have exploited the reasonable misgivings that incidents like the Pfizer trial and the AstraZeneca pause have created for many Africans.

Researchers from the Africa Center for Strategic Studies provide several examples of such misinformation:

One myth holds that live viruses are injected into the body and that individuals can die after vaccination. Another says that the vaccines cause infertility or serious side effects that are worse than contracting the virus. Other conspiracy theories hype that the vaccines are in fact poisons that alter the DNA to reduce Africa’s population. They also claim that vaccines are a cover to implant traceable microchips, and that Microsoft founder Bill Gates and the U.S. government are behind it.24

The cumulative effect of this misinformation and lack of information appears to be causing many people to overweight the costs and underweight the benefits of accepting a vaccine against COVID-19. This is evident in the fact that, in the 15-country survey by

the African Union and the Africa CDC, about half of the more than 15,000 respondents felt that the threat of COVID-19 had been exaggerated. This view was particularly prevalent among men, young people, and people who cited social media as a trusted source of information.25

Notably, health-related concerns about COVID-19 vaccines do not necessarily translate to hesitancy about vaccines more generally. Many people in subSaharan Africa—a region with a history of remarkable vaccination success stories—view COVID-19 vaccines as less safe than other types of vaccines. Although women in the region have higher levels of vaccine confidence in general compared to men, they appear to be more skeptical when it comes to COVID-19 vaccines.26 Additionally, in one study in Zambia, just 66% of parents and other caregivers who brought their children to a measles-rubella vaccination site indicated that they planned to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, which seems indicative of fears about the novelty of the COVID-19 vaccines. Yet a much larger share—92%—of the caregivers said that they intended to have their children vaccinated against COVID-19.27 This suggests that vaccine hesitancy may be due in part to a perception that vaccines are helpful for children, but unnecessary or even harmful for adults. As the study’s authors explain, “Agreeing to vaccinate a child likely reflects confidence in the vaccine, while refusal to self may reflect a lower perceived risk to personal health. Targeted messaging will be required to capture a population less familiar, and possibly less comfortable, with receiving vaccines.”28

Concerns about infertility are also dominant across the continent.

Popular misinformation narratives have suggested that the COVID-19 vaccine contains abortion drugs.29 Concerns about fertility can be shaped by mental models that women in particular may have. One expert, pointing out that many African women’s only adult encounter with injections is as a contraceptive method, suggested that a mental model in which shots are either for children or for birth control may contribute to fertility-related fears surrounding COVID-19 vaccines and their possible side effects.30 In addition, the thought of a new medicine affecting one’s ability to have children can evoke a particular fear for women living in communities where their identity as a mother is regarded as a central aspect of womanhood.31

For individuals who are hesitant about COVID-19 vaccines due to health concerns, research suggests that trusted messengers can help dispel misinformation and provide accurate information about the vaccines. This in turn can help individuals recalibrate their vaccine risk assessments to better account for the true benefits and risks of accepting a vaccine. Research by Brewer et al. suggests that recommendations from healthcare providers in particular are strongly associated with vaccination behavior, in part because these recommendations “may affirm or augment people’s perceptions of the value and safety of the vaccine.”32

In addition to enlisting healthcare providers as vaccine proponents, Nsoesie and Oladeji suggest several actions that social media companies could take to promote credible information and remove misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines from their sites. The researchers argue that algorithms could better identify and remove misleading content if the

algorithms were designed to recognize the similarities and differences in the framing of misinformation about COVID-19 transmission, prevention, treatment, and vaccination. Beyond these measures, the researchers encourage interventions aimed at increasing public understanding of the possible adverse health effects of misinformation. They write: “Health misinformation should be incorporated into digital education curriculum to educate the public on how to find, assess, validate, and corroborate information from trusted sources before adopting recommendations seen on social media platforms.”33

This recommendation appears repeatedly in the relevant literature. For instance, Brewer et al. urge policymakers to try to instill accurate knowledge and understanding of vaccines as much as possible before misinformation has a chance to spread in a community.34 This proactive approach is related to the “prebunking” or “inoculation” style of intervention that seeks to get out in front of misinformation. It reflects the reality that changing someone’s mind once they have already formed an opinion about a controversial topic is typically more difficult than nudging an individual toward a position on an emerging topic. As van der Linden et al. succinctly put it, “Prevention is better than cure. This is true as much for diseases as it is for the spread of misinformation.”35 As evidence, the researchers report that in one study of “prebunking” versus “debunking” interventions, “vaccination intentions only improved when participants were presented with anticonspiracy arguments prior to exposure to the vaccination conspiracy theories but not when presented with counter arguments afterward.”36

misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines, policymakers should take care to avoid interventions that might inadvertently backfire. Brewer et al. caution against two such approaches. The first is using pharmaceutical companies to reassure people about the safety and efficacy of vaccines. Evidence suggests that people do not perceive vaccine manufacturers as credible sources in this context, and the reassurances can actually increase suspicions that the vaccines are risky and/or ineffective. The second approach is relying on fear to motivate vaccine behavior. Brewer et al. cite evidence that suggests that fear communication can elicit anger, which undermines the effectiveness of the intervention.37

Concerns about the safety of COVID-19 vaccines remains the most cited reason for hesitancy both globally and in subSaharan Africa. Recent data show that on average, approximately 57% of vaccinehesitant individuals globally and 54% in Africa are worried about side effects, with the proportion ranging from 73% in Côte d’Ivoire to 40% in Tanzania.38 In the previously described 15-country study by the Africa CDC, researchers asked respondents if they agreed with the following statements to measure perceptions of vaccine safety:

• “COVID-19 vaccines are safe.”

» Responses among people who report willingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine: 84% “yes”; 14% “no”; 2% “don’t know”

» Responses among people who report unwillingness to accept a COVID-19 vaccine: 59% “yes”; 37% “no”; 4% “don’t know”

This mixed-method study utilized faceto-face and telephone interviews to gather responses from at least 1,000 respondents per country. The top five most common reasons respondents gave for not wanting to take a new COVID-19 vaccine were:

• “I do not trust the COVID-19 vaccine”;

• “I do not believe that the virus exists”;

• “I am concerned about the safety of the vaccine”;

• “I do not feel that I am at risk of catching the virus”; and

• “I do not have sufficient information to make a decision”.39

COVID Behaviors Dashboard suggests similar concerns. The most common reason given for vaccine hesitancy in the WHO African Region is “concern about side effects”, reported by 54% of respondents, followed by “plan to wait to see if it’s safe” (Table 2.1).

Source: COVID Behaviors Dashboard.

Note: Individuals who reported they would probably, probably not, or definitely not get vaccinated were asked about the reasons for their decision.

Source: The Collective Service for Risk Communication and Community Engagement.

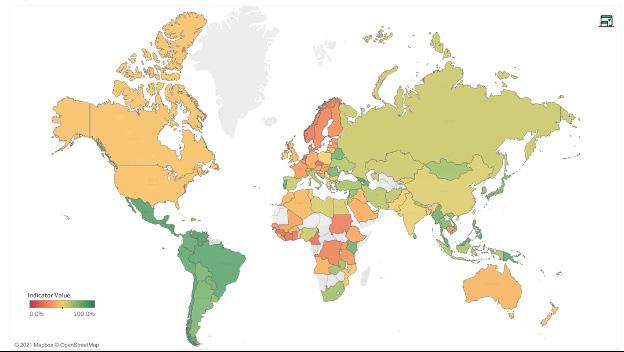

At the same time, risk perception varies widely by region within Africa. Data from Risk Communication and Community Engagement (RCCE) shows that close to half of all respondents in East and Southern Africa believe they are at risk of contracting COVID-19, compared to 39% in West and Central Africa—where vaccine hesitancy prior to the pandemic had been higher.40, 41 In the map above from the RCCE database, East and Southern African countries are mostly shaded green and orange, indicating a higher fraction of individuals who believe they are at risk of contracting

COVID-19. By contrast, many countries in Central and West Africa are shaded red, indicating lower risk perception among surveyed individuals.

Table 2.2 breaks down the percentage of survey respondents in each country who believe they are at risk of contracting COVID-19. Countries such as Mauritius and Kenya have relatively high risk perception, at 89% and 75%, respectively, while Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire have the lowest risk perception in the region, at approximately 20%.

Percentage of individuals who believe they are at risk of contracting COVID-19 (October 2021)

Source: The Collective Service for Risk Communication and Community Engagement.

Concerns about side effects and risk perception can also be driven by exposure to and belief in misinformation. Mental models shape the way people process misinformation. For example, polled respondents in Africa cite recurring disinformation narratives:

• “COVID-19 is a planned event by a foreign actor.” (49% “true”; 38% “false”; 13% “don’t know”)

• “People in Africa are being used as guinea pigs in vaccine trials.” (45% “true”; 42% “false”; 14% “don’t know”)

• “[COVID-19] Vaccine trials in Africa have led to the death of several children.” (33% “true”; 47% “false”, 19% “don’t know”).42

• “People in Africa are being used as guinea pigs in vaccine trials.” (45% “true”; 42% “false”; 14% “don’t know”)

• “[COVID-19] Vaccine trials in Africa have led to the death of several children.” (33% “true”; 47% “false”, 19% “don’t know”).43

Broadly, data suggests that concerns about the health and safety of COVID-19 vaccines and underestimates of the threat the disease poses lead many Africans to feel hesitant about accepting a COVID-19 vaccine. Additionally, populations in West and Central Africa have lower risk perception of COVID-19 compared to their counterparts in East and Southern Africa. These disparities may be due to lower access to factual information about COVID-19 in West and Central Africa; higher rates of disinformation circulating on social media platforms; and/or deeperseated factors such as a lack of trust in government, foreign actors, and the medical establishment.44 The issue of trust is discussed in greater detail in the next subsection.

Earlier, we described a 15-country survey by the African Union and the Africa CDC that surveyed over 15,000 individuals and examined sources of vaccine hesitancy in Africa. In large part, the study attributes vaccine hesitancy among respondents to doubts about the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines and misinformation about the disease.45 Similarly, Afrobarometer conducted a survey from October 2020 to January 2021 in which researchers collected responses from 6,000 individuals—1,200 per country—in five West African countries: Benin, Liberia, Niger, Senegal, and Togo. As was mentioned earlier, that study found that just four in 10 respondents indicated they were likely to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, and that lack of trust in government institutions drives much of the concern about vaccine safety. According to Seydou of Afrobarometer, “Vaccine hesitancy/ resistance skyrockets alongside doubts about the government’s ability to ensure that vaccines are safe…Large majorities in Niger (89%), Liberia (86%), and Senegal (71%) believe that prayer is more effective than a vaccine in preventing coronavirus infection.”46

Lack of trust has developed for many reasons. First, memories of colonization and other abusive political and economic practices committed in Africa by foreign powers are deep-rooted. Research has shown that countries in Central Africa that were targets of invasive colonial medicine projects involving painful and damaging forced procedures have lower acceptance of vaccination and blood tests today.47 Additionally, as was mentioned earlier, West Africans are

particularly distrustful of new vaccines after an experimental meningitis vaccine tested by Pfizer in 1996 killed 11 children and paralyzed dozens more in northern Nigeria.48 That tragedy resulted in drastic reductions in routine vaccinations for tuberculosis, tetanus, measles, and polio, and set back the global goal to eradicate polio by a decade.49 Since this historical episode is a part of recent memory for the region, it potentially has reinforced mental models that shape the way people receive and process misinformation. For example, some misinformation narratives circulating today suggest that Africans are being used as guinea pigs (45% of polled respondents believe this to be true) or that COVID-19 vaccine trials in Africa have led to the death of several children (33% believe this to be true).50

Where people get their information also plays a significant role in shaping individuals’ attitudes toward vaccines and their exposure to misinformation. In the Africa CDC study, 64% of respondents listed television as one of their most trusted sources of information about COVID-19; 51% listed radio (61% in West Africa); 41% listed online sources; 23% listed health bodies; and just 18% listed government sources. The survey also found that “[o]nline channels, particularly social media, tend to be the most trusted source among hesitant groups,” and that misinformation about COVID-19 “appears to be widespread, with those who self-report exposure to rumors also showing a higher propensity to believe them.”51 Additionally, trusted information sources vary across countries and across demographic groups; for example, older respondents were more likely to trust healthcare bodies and government sources, while online sources tend to be trusted more by men and by young people.52

The reasons for lack of trust vary across countries, communities, and individuals. For example, distrust in powerful foreign institutions and conspiracy theories about efforts to “depopulate” Africa have led to pervasive concerns about COVID-19 vaccines causing infertility across the continent. Similarly, recurrent misinformation narratives have suggested that the COVID-19 vaccines contain abortion drugs.53 Misinformation about COVID-19 vaccines being dangerous and harmful for Africans is particularly pernicious because such content is spread using highly sophisticated techniques on social media, such as content modification, coordinated copy-pasting across dozens of groups with thousands of users, coordinated link sharing, and crossplatform posting within a few hours or days, resulting in tens of thousands of shares.54 This mass amplification of misinformation erodes trust in the very institutions tasked with delivering COVID-19 vaccines in Africa. Data shows that mistrust in institutions and external actors is strongly linked to vaccine refusal, especially among individuals who are more educated, younger, urban, and social media users.55

In-group and out-group attitudes also play a significant role in trust in COVID-19 vaccines. The groups that individuals identify with may have an effect on their behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic, including the decisions to wear masks, socially distance, and accept a COVID-19 vaccine. In-group bias is the tendency for individuals to give preferential treatment to members of their own group, as well as disregarding or actively harming outgroups. Perhaps most significantly for our work, that preferential treatment includes increased trust inof fellow in-group members. In-group bias is

based on social identity theory, which postulates that individuals construct a large part of their identities through their membership in groups.56 Research on vaccine-rejecting parents in Australia (conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic) showed that these parents constructed themselves and their vaccine-rejecting peers as an in-group important to their sense of identity, and considered vaccinators as an outgroup, thinking of them as the “Unhealthy Other.”57 Research on social identity and in-groups also tells us that people are more likely to trust individuals within their in-group and to distrust, and less likely to trust individuals in the outgroup. As a result, traditionally vaccinerejecting individuals are unlikely to trust messages coming from out-group members. Depending on the country context, as COVID-19 vaccination rates increase and certain demographics in sub-Saharan Africa begin to be more likely to be vaccinated compared to others, it is possible that in-group/outgroup dynamics will also emerge along the lines of vaccination status.

While it is difficult to debunk misinformation once it is widespread, an important step articulated by Kumar and Geethakumari is “identifying the most influential nodes whose decontamination with good information would prevent the spread of information.”58 Early detection campaigns, proactive countermessaging, and communications that address deep-seated issues of trust with actors and institutions connected to vaccines are all vital in weakening belief in the misinformation presented and ultimately reducing vaccine hesitancy. Therefore, bolstering the legitimacy of these institutions among populations exposed to certain disinformation narratives will be necessary to stem hesitancy in the long-term. Bolstering

legitimacy entails having a recognized justice and dispute resolution system that is seen as fair, a consistent provision of basic services for citizens, the assurance of physical security for civilians, and governing institutions that are deemed accountable to citizens.59 Achieving this essentially means systemic change throughout the continent. For the time being, in order to curb vaccine hesitancy in the short-term, it is important to rely on institutions and individuals that are trusted by individuals who are prone to vaccine hesitancy. These trusted individuals may include religious leaders, local healthcare providers, and some intergovernmental officials from organizations like the WHO.

Additional research from Australia conducted by Cruwys et al. found that people indicated a greater willingness to take a vaccine and perceived it to be less risky when it was developed by an ingroup rather than an out-group source.60

The research included two prospective surveys and one experiment. In the experiment, which took place before any COVID-19 vaccines were available, the researchers tested respondents’ willingness to get a vaccine when the vaccine was developed by Australians (in-group, treatment 1) as compared to the French (out-group, treatment 2). The authors note that not all outgroups are the same. For example, most Australians perceive the United States to be a higher-status country, and France to be a similar-status country. The authors intentionally chose France, and they found that respondents were indeed more willing to accept a vaccine developed by in-group members—fellow Australians—compared to French outgroup members. When considering this research in the context of sub-Saharan Africa, one needs to carefully consider how different out-groups are perceived,

including the various countries that have produced COVID-19 vaccines. Cruwys et al. limited their study to Australian participants, meaning that we should be cautious about external validity for sub-Saharan Africa. However, despite being conducted in a different context, the study’s implications are important to consider in sub-Saharan Africa. The authors interpret their results to mean that the tendency to trust in-group members can be harnessed to improve COVID-19 public messaging.

As noted in the literature review, trust—or lack of trust—can shape how misinformation “sticks” in people’s minds. Therefore, identifying the trustworthy entities conveying vaccine-related information is important to reduce misinformation that would otherwise hinder vaccine acceptance. Trust in institutions varies depending on each individual’s socioeconomic, religious, and racial background, and their level of trust also varies across institutions. Among different institutions, governments and how they are perceived by their citizens provide a notable insight into expected vaccine uptake.

Afrobarometer’s survey on five West African countries asked respondents about their trust in government in relation to their vaccine acceptance.

• “How much do you trust the government to ensure that any vaccine for COVID-19 that is developed or offered to citizens is safe before it is used in this country?” (68% Not at all/Just a little; 31% Somewhat/A lot)

• “If a vaccine for COVID-19 becomes available and the government says it is safe, how likely are you to try to

get vaccinated?” (44% Very unlikely; 16% Somewhat unlikely; 19% Somewhat likely; 20% Very likely)

Using these questions, Afrobarometer was able to compare vaccine hesitancy and resistance in relation to people’s trust in government. They found that vaccine hesitancy or reluctance runs high where people highly doubt “the government’s ability to ensure that vaccines are safe.”61 The high (negative) correlation between people’s trust in government and vaccine acceptance rate is consistent with studies focused on other regions, such as North America and Asia.62

Identifying the most trusted sources of information about COVID-19 is a key step in dispelling or correcting misinformation. The Johns Hopkins COVID Behaviors Dashboard provided eight trusted sources as answer choices in its related question.

• “How much do you trust the following sources to provide accurate news and information about COVID-19?” (Trusted sources: local health workers and clinics; scientists and other health experts; WHO; government health authorities or officials; politicians; journalists; friends and family; and/ or religious leaders)63

The Dashboard uses a two-by-two grid, using exposure level (“the percentage of people who get information from that source”) and trust level as the axes.64 WHO data from the African region shows that local health workers, scientists, and other health experts, on average, are trusted information sources (Figure 2.2). The country-specific graphic provides insight into how messaging can have varying effects on the national and

local levels, as well as into which sources would likely be effective carriers of messages and interventions correcting misinformation.

Data indicates that the WHO is generally regarded as a more trusted information source than government health authorities or officials in Africa. The country-level differences in trust

levels in government and international health organizations are important to note, however. This is consistent with the findings from the Africa CDC’s 15-country survey (Figure 2.3), which notes “regional differences are evident, suggesting that a country-specific approach would be necessary" when advocating for vaccine safety and effectiveness.65

Note:

Source: COVID Behaviors Dashboard.

Note: Results for the period from Nov 1 to Nov 15, 2021

Source: Africa CDC. (2021).

Depending on the country-specific or regional context, survey questions can be worded to attempt to gauge how people’s socioeconomic, racial, religious, and/or geographical background has contributed to their trust in institutions. In the United States, where many people of color have had negative experiences within the healthcare system due individual and systemic racism, people’s perception of fairness in the medical system can be asked in relation to race, as in Surgo Ventures’s survey question: “How strongly do you agree/disagree that people of your race are treated fairly in a healthcare setting?”66 A variation of this question could be utilized to test people’s trust in the healthcare system that is context-variant. Given this paper’s geographical focus on subSaharan Africa as a whole, it is important to note the varying degrees of impact different identity markers will have in various countries and regions. While a question tailored for the specific country or community of focus is recommended, a two-part question could account for some heterogeneity of the survey region when conducted across many countries:

• A. How strongly do you agree/ disagree that people with the same identity as you are treated fairly in a healthcare setting?

• B. What identity are you referring to in Part A?

Answer choices for Part B of this sample question can include: country, race, gender, tribe, ethnic group, religion, and economic status. These answer choices are inspired by questions included in the Afrobarometer Round 8 survey in South Africa, specifically in its “Identity and society” section.67 The order of Parts A and B will anchor the survey respondents in different ways.

Literature review

When individuals encounter information online, especially on social media, how carefully do they consider its veracity? Do they engage their deliberative system of thinking, expending mental effort to consider indicators of credibility? Or do they engage in “automatic thinking,” absorbing the information without concentrating on whether or not it is likely to be true?68 Might individuals choose to share misinformation without going through the cognitively effortful process of attempting to ascertain whether or not it is true?

Depending on the answers to these questions, we may conclude that automatic thinking drives individuals to believe online misinformation, to share it on social media, or both. The implication is that if individuals paused and engaged in deliberative thinking, they would be less likely to believe and/ or share misinformation online.

This was the conclusion of a review article by Pennycook and Rand in which the researchers synthesized existing literature on online misinformation and found that “poor truth discernment is associated with lack of careful reasoning and relevant knowledge, and the use of heuristics such as familiarity”—trademarks of automatic thinking.69 The authors concluded that a large proportion of misinformationsharing online happens as a result of this automatic thinking process. They also reported findings that a simple intervention designed to address inattention—asking participants to rate the accuracy of each headline before deciding whether or not to share it—

reduced the sharing of misinformation by 51% relative to a control group.70 To state these results in a different way, according to Pennycook and Rand, automatic thinking is largely responsible for the sharing of misinformation; therefore, interventions that combat automatic thinking by forcing people to pay attention to the veracity of the content they encounter should reduce misinformation sharing.

An additional study that appears to support the hypothesis that automatic thinking drives misinformation sharing behavior comes from Rosenzweig et al. The researchers found that feeling any emotion, and particularly happiness and surprise, was positively correlated with belief in and sharing of false, relative to true, headlines.71 Emotional responses are a key component of automatic thinking; they drive impulsive, nondeliberative thought processes and decision-making.

Both Pennycook and Rand and Rosenzweig et al. focused on misinformation sharing behavior, rather than belief. It is not clear from their research that interventions designed to combat automatic thinking might work uniformly to interrupt both individuals’ belief in and their sharing of misinformation. Indeed, Pennycook and Rand note the “substantial disconnect between what people believe and what they share on social media.”72

This disconnect has also been observed in the specific context of COVID-19 misinformation behaviors in two subSaharan African countries. Wasserman and Madrid-Morales surveyed approximately 1,967 individuals in Kenya and South Africa in April 2020 and found that a significant percentage of respondents showed an interest in

sharing misinformation about COVID-19 online, even if they did not believe the content. The researchers report: “The most common motivation to share these social media posts was a perceived moral or civic duty to share information (whether true or not) and raise awareness about an issue. There was also a desire to spark debate and solicit other people’s views. Many respondents also said they would share misinformation for fun or entertainment.”73 Given these findings, it seems likely that at least for some people, the threshold for sharing social media content is lower than the threshold for actually believing it.

If automatic thinking is a major contributor to sharing misinformation, can educative interventions decrease misinformation sharing? The approach proposed by Pennycook and Rand— prompting social media users to pay attention to content veracity before they share—is a top-down intervention that hinges on the use of sites such as Facebook and Twitter, where the platform can flag misleading content and deliver prompts directly to users. In developing countries such as India, however, encrypted messaging services like WhatsApp are much more popular. Consequently, top-down interventions are less feasible on these services. Considering the challenge of encryption, educative interventions that encourage user-driven learning and fact-checking offer another possible path to curbing automatic thinking and misinformation sharing.

Evidence on such an approach comes from an experiment by Badrinathan in India, in which participants received a media literacy training program intended to improve their ability to identify misinformation. The intervention was designed to mitigate

some of the effects of automatic thinking by teaching individuals how to use deliberative thinking processes to identify misinformation. However, Badrinathan found that the intervention did not, in fact, significantly increase recipients’ ability to correctly identify misinformation. Further, among one important subgroup—supporters of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), to which the current Indian prime minister belongs—the intervention actually reduced recipients’ ability to identify pro-attitudinal stories as false.74 This “backfire effect” suggests that, at least for BJP partisans, encouraging deliberative thinking may not be enough to dislodge belief in misinformation. In some contexts, motivated reasoning and identity-based cognition heavily influence belief in misinformation.75

Badrinathan’s findings demonstrate the importance of both identitybased cognition and consideration of local context when designing misinformation interventions. Slowing down automatic thinking and shifting to deliberative thinking may not be enough. Interventions that work in developed countries may not transfer to developing countries, particularly given differences in the demographics of social media users. Educative interventions about misinformation also may differ in their effectiveness based on the political nature of the content featured in the experiments. This would suggest that the degree to which COVID-19 is perceived as a political or ideological issue within any given context may impact the efficacy of interventions designed to counter automatic thinking.

In one of the studies reviewed in the Pennycook and Rand article described above, 1,005 participants who regularly

shared political news on social media were randomized to see 36 true and false news headlines on Facebook and Twitter.76 Before participants were selected and randomized, to ascertain whether or not potential participants shared political news on social media, every potential study participant was asked:

• “Would you ever consider sharing something political on Facebook?” (“yes”; “no”; “I don’t use social media”). Those who responded yes were included in the main analysis.

• Individuals in one arm of the study— the accuracy condition—were asked:

“To the best of your knowledge, is this claim in the above headline accurate?” (“not at all accurate”; “not very accurate”; “somewhat accurate”; “very accurate”)

• In the sharing condition, participants were asked: “Would you consider sharing this story online (for example, through Facebook or Twitter)?” (“yes”/“no”)

In a follow-up study, researchers recruited 401 participants to investigate the extent to which individuals value accuracy when deciding to share information online. Participants were asked:

• “When deciding whether to share a piece of content on social media, how important is it to you that the content is...?” (column labels—“not at all”, “slightly”, “moderately”, “very”, “extremely”; row labels—“accurate”, “surprising”, “interesting”, “aligned with your politics”, “funny”)

Subsequent studies aimed to identify whether calling attention to accuracy increases sharing of accurate news online. As a pretest, participants in this

study were asked to judge the accuracy of a politically neutral news headline to see if this “accuracy cue” had an effect on participants’ capacity to pay closer attention to news accuracy in subsequent tasks. They were also asked:

• “Do you agree or disagree that it is important to only share news content on social media that is accurate and unbiased?” (Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”)

• “If you were to see the above article on Facebook, how likely would you be to share it?” (“extremely unlikely”, “moderately unlikely”, “slightly unlikely”, “moderately likely”, “extremely likely”)

The authors found that when asked to rate the accuracy of a headline before sharing, participants reduced sharing of false headlines by 51%.

People may also rely on heuristics or mental shortcuts when evaluating whether to read and share content online. Pennycook and Rand note that a salient feature of misinformation is its emotional evocativeness, and especially its ability to provoke moral outrage.77 Indeed, misinformation is “sticky” because it often features deeply emotive human stories that elicit reactions such as anger, surprise, happiness, and fear. For example, in a study of 409 adults in the United States, Martel et al. found that people who report positive or negative emotions before encountering a headline were more likely to believe false news headlines. Participants completed a 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule scale and for each item were asked:

• “To what extent do you feel [itemspecific emotion] at this moment?”

(Likert scale: 1=very slightly or not at all; 2=a little; 3=moderately; 4=quite a bit; 5=extremely)

Following this assessment, participants were randomized and shown a series of 20 actual headlines, half of which were accurate and the rest fake news. Some headlines were favorable to the Republican Party and some to the Democratic Party. Headlines were presented in the form of Facebook posts with a picture, headline, byline, and source. All participants were asked a follow-up question:

“

To the best of your knowledge, how accurate is the claim in the above headline?” (Likert scale: 1=not at all accurate; 2=not very accurate; 3=somewhat accurate; 4=very accurate)

The researchers found that belief in fake news is nearly twice as high for participants with the highest aggregate positive and negative emotion scores compared to participants with the lowest emotion scores. However, the study does not find significant threeway interactions among political concordance, emotion, and news type (accurate versus fake).78

The Rosenzweig et al. study discussed above found that COVID-19 headlines that generate emotions among social media users were more likely to be believed and shared.79 The online study recruited 1,341 Facebook users in Nigeria and showed them a mix of 10 true and false COVID-19 headlines. After reading the headline, participants were asked to rate their emotions using emojis:

• “Please select the emoji(s) that best represent your emotional state when you read the headline.” (surprised; scared; angry; disgusted; happy; sad)

• “On a scale from 1 (not very strongly) to 7 (very strongly), how strongly did you feel [emotion]?”

The authors measured belief using the question:

• “Do you think this headline accurately describes an event that actually happened?”

• “Are you interested in clicking to read the headline and sharing the headline online?”

The researchers found that happiness and surprise were associated with greater belief in and sharing of false COVID-19 headlines relative to true headlines.

Literature review

Social norms are defined as the “tacit rules that members of a group implicitly recognize and that affect their decisions and behavior.”80 There are two types of social norms: descriptive and injunctive norms. Descriptive norms indicate the behavior of relevant others and inform behavior by example, while injunctive norms represent how important others would like one to behave and they influence behavior through informal reinforcements or punishments. One source expands on the notion of social norms further: “We look to other people when in doubt…Taking cues from other people’s behavior is a valuable resource when we seek to improve our own decision-making.”81

As an example, healthcare providers can create and communicate injunctive social norms by indicating to their patients, either through explicit recommendations or implicit cues, that they expect patients to get vaccinated.

Their recommendations can also communicate descriptive social norms by implying that most other patients get vaccinated or that vaccination is what most previous patients have chosen before misinformation proliferated.82

A study by Gauri et al. illustrates how shifting social norms reduced the problem of open defecation in rural India. Although it was not directly related to vaccines, this experiment explored how mental models and social norms influenced individuals’ attitudes and behaviors toward an important public health resource, and aspects of the intervention may therefore be applicable to the context of COVID-19 vaccines. The researchers found that there were two pathways through which social norms inhibited the use of toilets in rural India: (1) beliefs about ritual notions of purity that dissociate latrines from cleanliness; and (2) beliefs and expectations that others do not use toilets or latrines, nor find open defecation unacceptable. Thus, the researchers piloted an information campaign to test the effectiveness of two strategies. The first was rebranding latrine use to associate it with cleanliness. The second was promoting positive social norms by providing information about the increasing prevalence of latrine use among individuals’ neighbors.

As the study explains, “If practices are motivated by social beliefs, changing empirical and/or normative expectations can shift people away from engaging in the practice. If information about the positive practices and behaviors of others in one’s reference group can be highlighted, it can induce positive behavior change by updating people’s perceptions of what others do and what the social norms are within their reference group.”83 A version of this intervention adapted to the COVID-19

context might inform individuals about how other people in their reference group—perhaps their local community, or their country, or their religious group— regard COVID-19 vaccines. If individuals learn that the majority of their referents intend to accept a COVID-19 vaccine, for example, it might nudge them toward acceptance as well.

Relatedly, findings about demographic trends in vaccine attitudes suggest that social norms may reinforce vaccine acceptance or hesitancy for different groups of people. For example, the Africa CDC has observed higher-thanaverage vaccine hesitancy among young people, city residents, the unemployed, and women. In the Africa CDC’s 15-country survey, the researchers found that vaccine acceptance was highest in Ethiopia and Niger and lowest in Senegal and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Factors associated with vaccine skepticism included not knowing anyone who had tested positive for COVID-19; believing that the threat of the disease had been exaggerated; and believing in conspiracy theories.84

Social norms are also impacted by the influence of social networks. Lack of social norms about fact checking before sharing information online can lead individuals to fail to identify misinformation. Online misinformation spreads quickly in part because it elicits an emotional response. In one article, Lewandowksy et al. summarize studies that show how repetition in the echo chambers of social media can create a “perceived social consensus,” even if such a consensus does not exist, and how this can result in pluralistic ignorance and solidify one’s belief in misinformation. This effect is stronger when information comes from within people’s reference groups. Once an individual’s social

network has shared misinformation, anything that is inconsistent with it is deemed as inconsistent or incompatible. The researchers elaborate: “Messages that are inconsistent with one’s beliefs are also processed less fluently than messages that are consistent with one’s beliefs… In general, fluently processed information feels more familiar and is more likely to be accepted as true; conversely, disfluency elicits the impression that something doesn’t quite ‘feel right’ and prompts closer scrutiny of the message.”85

Social networks can also serve as a positive source of information and set communal behavior. For example, the Social Mobilisation Action Consortium was Sierra Leone’s coordinated community engagement initiative during the Ebola outbreak. The Consortium worked across 14 districts and approximately 12,000 communities, comprising organizations such as mosques, churches, and radio stations. The Consortium facilitated over 2,000 Community Mobilizers to implement behavioral change interventions. These interventions were effective when communication channels and platforms were appropriately used, combining community-based interpersonal communication with mass media. Specifically, consistent information and messaging that supported communityled responses and were repeated and reinforced via multiple channels demonstrably increased information credibility. Additionally, radio provided a platform to disseminate accurate information using trusted messengers, including religious leaders, community champions, traditional healers, survivors, and others. Religious leaders, in particular, were able to use social networks to persuade communities to adopt behavioral changes related

to modifications in traditional burial practices.86

Other effective mobilization strategies that have utilized social networks include campaigns like the Oseto-Ose Tok (House-to-House Talk) campaign, which brought together social mobilizers, youth, and volunteers who went door-to-door to share information on ways families could protect themselves against the Ebola virus and prevent its spread. Groups that went door-to-door consisted of a health worker, a community volunteer, a youth leader, and a teacher. In addition to spreading helpful information and providing communication materials on Ebola prevention, these groups also dispelled rumors and misconceptions about Ebola. Another low-technology tool, megaphones, became an important communication device across West African countries in rural and urban areas. Megaphones were used to gather crowds and make announcements containing Ebola prevention messages, sometimes on moving vehicles, through town criers or traditional communicators.

In conclusion, social learning and normsetting strategies can shift social norms to promote greater COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. If individuals witness their friends, relatives, and other reference group members getting the vaccine, they may be more likely to follow suit, as they can rely on immediate information from close contacts who are reliable sources rather than on the questionable information they may encounter online.

To restate a few key insights from our literature review, the scope of social norms largely depends on what is considered normal within an individual’s

reference group. Researchers often distinguish descriptive norms, which “offer information people can use to orient their actions,” from injunctive norms, which “put pressure on people to meet other people’s expectations.”87 While the workings of social processes are complex, the literature establishes a strong correlation between social norms and individuals’ behaviors. Specifically regarding COVID-19 vaccines in Africa, a data synthesis paper from Tulloch et al. noted that “local social norms may be more influential on people’s actions than rumours or misinformation.”88 A systematic literature review on H1N1 vaccine uptake from Bish et al. similarly concluded that there is “evidence of an influence of social pressure in that people who thought that others wanted them to be vaccinated were more likely to do so.”89

This is consistent with what Graupensperger et al. found in their November 2020 study of vaccination attitudes among U.S. undergraduate students: “[S]ocial norms...are robust predictors of health behaviors.” To assess both descriptive and injunctive norms, Graupensperger et al. asked:

• To assess descriptive norms:

“Considering typical young adults in America, what percentage do you think will get a[COVID]/[flu] vaccination/shot?” (On a scale of 0% to 100%)

• To assess injunctive norms: “In your estimation, how important do typical young adults think it is to get a [COVID]/[flu] vaccination/shot?” (A 7-point Likert scale, 1 = Not at all important and 7 = Extremely important)

The authors found that “estimated social norms were positively associated

with participants’ own intentions and perceived importance of getting a COVID vaccine.”90

Others have analyzed social norms through the lens of Theory of Reasoned Action and Theory of Planned Behavior to predict the behavioral outcome in other parts of the world. For such studies, the questions were more direct in connecting the respondents’ behavior and their perception of social norms:

• “The opinion of family and friends is important in my decision to take COVID-19 vaccine” (A 10-point scale, 1 = Absolute negative and 10 = Absolute positive)91

• “My relatives expect from me to do X” (A 5-point Likert scale: 1 = Completely disagree; 5 = Completely agree) where X referred to health behaviors such as handwashing and limitation of social contact.92

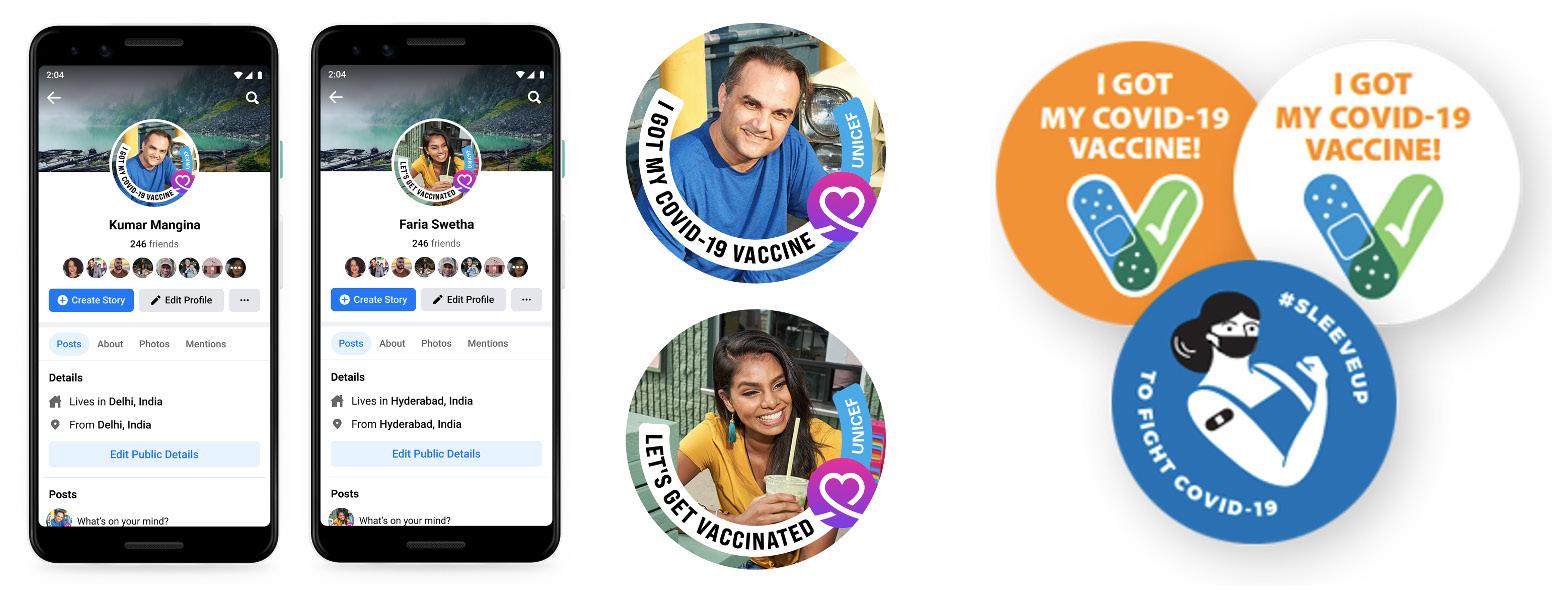

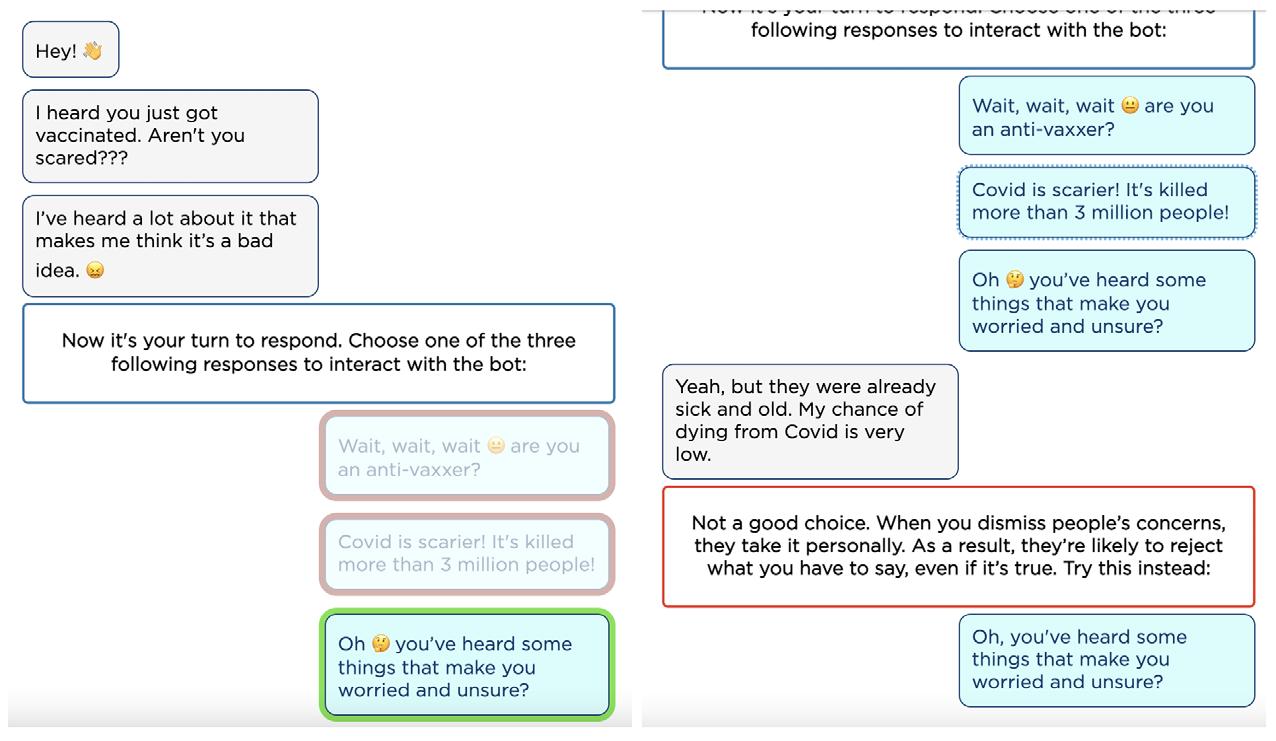

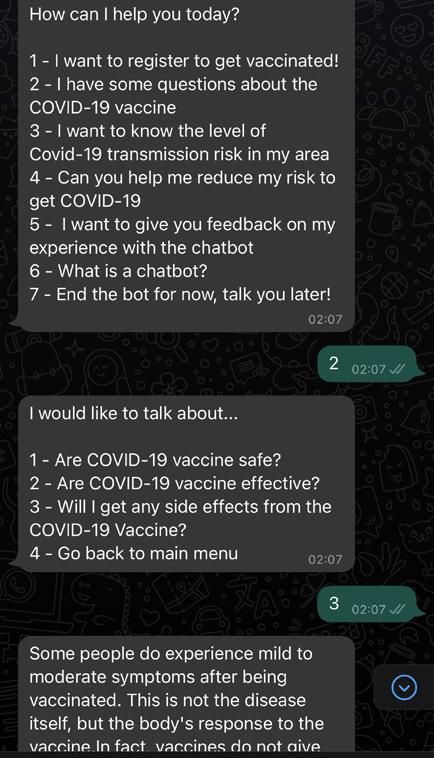

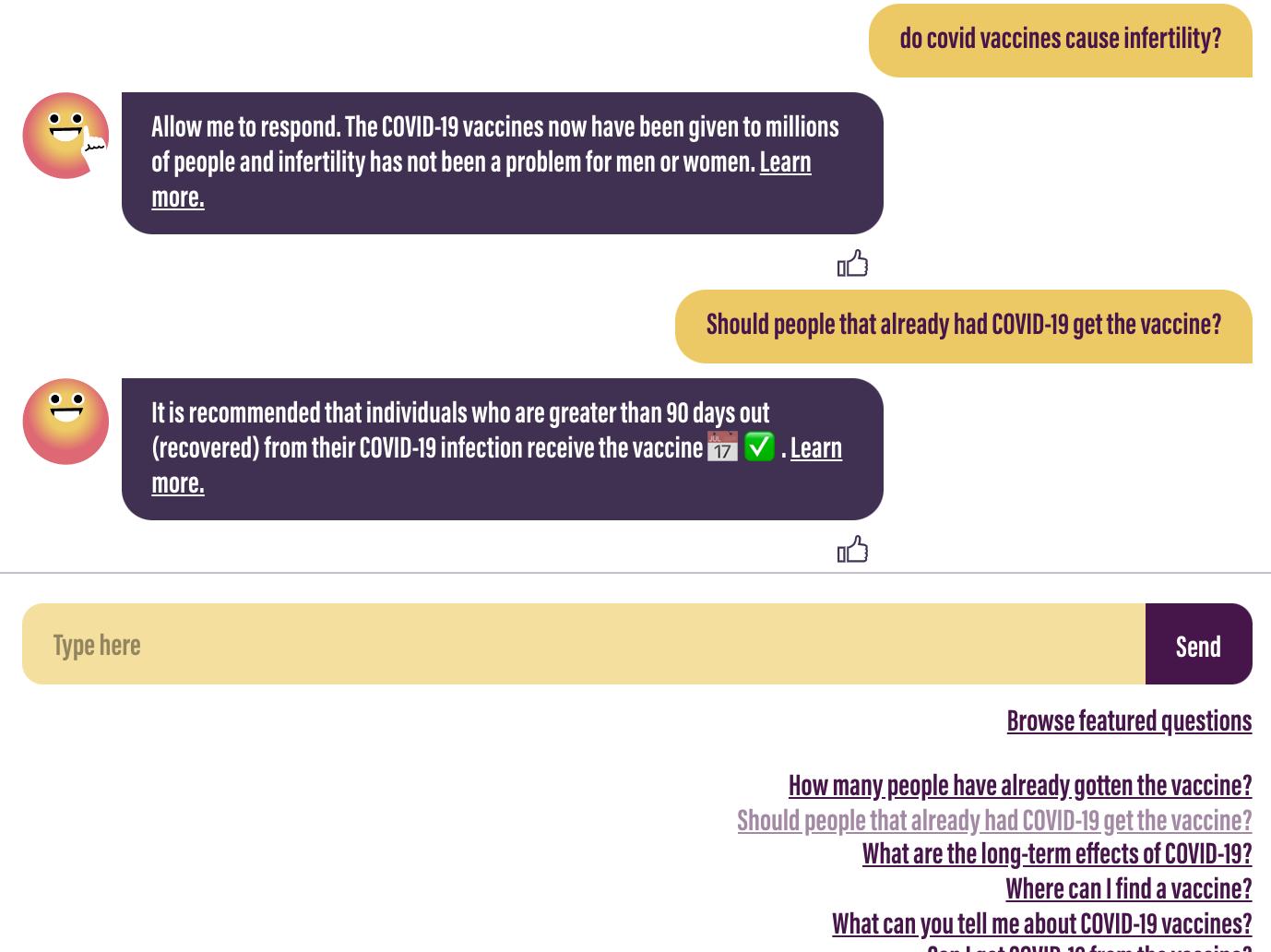

In addition to influencing vaccination behavior, social norms can be a strong driver of misinformation belief and sharing. Lewandowsky et al. note that “perceived social consensus can serve to solidify and maintain belief in misinformation.”93 As the impact of social norms is well established across cultures, a crucial aspect to utilizing social norms to curb misinformation is identifying demographic factors that construct social norms. In addition to unearthing these broad trends, it is important to identify the motivations for individuals’ attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines. Such motivations appear to vary widely across individuals and groups, ranging from protecting oneself and others to asserting freedom of choice to acting upon a sense of civic responsibility. Understanding these motivations is key to designing context-specific and effective interventions.