Expanding Health Insurance Coverage in the United States Virgin Islands

This report was prepared by Master in Public Affairs students at Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs. This report incorporates information gathered through students’ independent research, in-person and remote interviews conducted between October 17 and October 28, 2022, and invaluable guidance from course instructors Heather Howard and Dan Meuse. The report fulfills the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs’ degree requirements for an immersive policy workshop and associated policy proposal. We are grateful to the United States Virgin Islands Department of Human Services that enabled us to conduct research and make recommendations on this topic, particularly to Medicaid Director Gary Smith. We also wish to extend our gratitude to the many policymakers, health professionals, consumer advocates, and subject matter experts who shared their perspectives with us throughout the course of this project. We hope that this report will contribute to ongoing efforts to build on and expand the successes of the United States Virgin Islands’ Medicaid program.

Eduardo bhatia, Former President, Senate of Puerto Rico, and John L. Weinberg/Goldman Sachs & Co Visiting Professor, Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

Cheryl Charleswell , Chief Examiner, United States Virgin Islands Division of Banking, Insurance, and Financial Regulation

Tina Comissiong , Chief Executive Officer, Schneider Regional Medical Center

Justa Encarnacion, Commissioner, United States Virgin Islands Department of Health

Senator novelle E. francis Jr. , Vice President, Legislature of the Virgin Islands

Senator Donna frett- gregory, President, Legislature of the Virgin Islands

lisa Hanley, Interim Director for Healthcare Service Financials, Governor Juan F. Luis Hospital and Medical Center

Tai Hunte-Caesar, Chief Medical Officer, United States Virgin Islands Department of Health

Rosalie Javois, Interim Executive Vice President of Finance, Governor Juan F. Luis Hospital and Medical Center

natasha Joseph, Financial Advisor, St. Thomas East End Medical Center

Doug koch, Chief Executive Officer, Governor Juan F. Luis Hospital and Medical Center

Joanne luciano, Partner, Data and Technology Associates, LLC

Roida mason, Vice President of Human Resources, Schneider Regional Medical Center

g lendina m atthew, Acting Director, United States Virgin Islands Division of Banking, Insurance, and Financial Regulation

Hazel Philbert , Chief Operating Officer, Governor Juan F. Luis Hospital and Medical Center

Darice Plaskett , Chief Nursing Officer, Governor Juan F. Luis Hospital and Medical Center

Julia Sheen, Health and Human Services Policy Advisor to Governor Albert Bryan

gary Smith, Medicaid Director, United States Virgin Islands Department of Human Services

massarae Sprauve webster, Chief Executive Officer, Frederiksted Health Care, Inc.

Donna Street , Manager of Billing & Collections, St. Thomas East End Medical Center

Shawna Richards, Chief of Staff to Senator Novelle Francis

brandon Richardson, Vice President of Information Systems, Schneider Regional Medical Center

Janis Valmond, Deputy Commissioner, United States Virgin Islands Department of Health

Su- l ayne walker, Legal Counsel, Schneider Regional Medical Center

Jay w oods , Director of Revenue Services, Frederiksted Health Care, Inc.

EXPANDING HEALTH INSURANCE COVERAGE IN THE UNITED STATES VIRGIN ISLANDS

A bP Alternative Benefit Plan

ACA The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

APP Advanced Practice Provider

APR n Advanced Practice Registered Nurse

bEAD Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program

CHIP Children’s Health Insurance Program

Cm S Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

CoVID-19 SARS-CoV-2, or Coronavirus 2

CSf Critical Shortage Facility

DoH Department of Health

DHS Department of Human Services

ffCRA Families First Coronavirus Response Act

fm AP Federal Medical Assistance Percentage

fQHC Federally Qualified Health Center

f Y Fiscal Year

HCoP Health Careers Opportunity Program

HIE Health Information Exchange

HPSA Health Professional Shortage Areas

HRSA Health Resources and Services Administration

ImlC Interstate Medical Licensure Compact

lCmE Liaison Committee on Medical Education

nf Nurse Faculty

nHSC National Health Service Corps

PmPm Per-Member Per-Month

R n Registered Nurse

SPA State Plan Amendment

USVI The United States Virgin Islands

USVIPl USVI Poverty Level

UVI University of the Virgin Islands

As a U.S. territory, the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) is situated in a unique geographical, population, and funding context. Not only is the USVI over a thousand miles away from the mainland U.S. and frequently susceptible to natural disasters such as hurricanes, but its population of approximately 87,000 people is seven times smaller than the smallest state.1 The USVI is also subject to many legal and financial challenges that impact the health of its residents. Its high cost of living paired with a high poverty rate exacerbate health disparities compared to the general U.S. population, and the USVI’s status as a territory makes it ineligible for certain federal healthcare funding opportunities that are normally available to states. This report proposes recommendations to improve access to affordable and quality healthcare given these constraints.

Our primary recommendation is to increase health insurance coverage for USVI residents by implementing a Medicaid buy-in program. We also recommend several broader health system improvements to enable the success of a Medicaid buy-in program. We selected these strategies based on their ability to improve health insurance coverage, access to care, and population health outcomes, while also considering estimated costs, political viability, and potential administrative burden on USVI government agencies. Our recommendations, which are summarized in a table on the following page, were ultimately informed by insights drawn from interviews with 27 stakeholders across government, healthcare facilities, and partner organizations in the USVI.

Establish a medicaid buy-in Program

1. Identify the eligible population and determine the income eligibility threshold

2. Establish a premium structure and use the remaining Medicaid funds allotted to the USVI to subsidize premiums

3. Adjust the Alternative Benefit Plan for the Medicaid buy-in population

4. Design a marketing strategy to promote take-up of the Medicaid buy-in program

Expand Health Education measures and Improve Health literacy

1. Promote the importance of preventive care through individual patient interactions and broader community outreach

2. Educate residents about the benefits of health insurance

1. Partner with the UVI Medical School

2. Adopt medical compacts to facilitate provider licensing

3. Increase telehealth utilization

4. Leverage health workforce development funds to increase provider supply

5. Improve care coordination

1. Create a new cross-agency Healthcare Cabinet task force

2. Develop a centralized government healthcare website for healthcare information.

1. Improve collaboration between DOH and health facilities for data sharing

2. Train interested DHS and DOH employees in data analysis

3. Establish the Health Information Exchange

Like other territories, the structure of the capped block grant Medicaid system of the USVI results in limited federal resources for the provision of care. Individuals without employer-sponsored health insurance, who earn an income that is too high to qualify for Medicaid, are left without a coverage option due to the unavailability of individual health insurance plans. The tempestuous fiscal cycles of the federal government expose additional vulnerabilities for territories by creating moments of funding uncertainty.

In this unique environment, the Department of Human Services requested our assistance in identifying options to expand coverage to more residents of the USVI. The Medicaid buy-in program serves to include more members, who would have otherwise been ineligible for coverage, and provide them with access to healthcare services.

In this report, the background section offers context on demographics, economic considerations, and the healthcare landscape of the USVI. Next, the methodology section outlines our research methods and analytical approach to developing recommendations. The subsequent set of recommendations all serve the overarching goal of covering more residents of the USVI with comprehensive health services. Recommendation

1 is our core policy recommendation, while Recommendations 2–5 are enabling recommendations which are critical to the success of core Recommendation 1.

While this is not an exhaustive list of ways to expand healthcare access, these recommendations draw on recurring themes from stakeholder interviews conducted in the USVI. We heard about individuals who would like to use Medicaid, the need to improve and expand health education and literacy, the challenge of provider shortages, a desire to improve intergovernmental coordination, and the relevance of effective health data collection and analysis.

The authors of this report are eight graduate students at Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs, and this report is prepared for the capstone project of the Master in Public Affairs program. This report is informed by secondary research as well as interviews with stakeholders across St. Thomas and St. Croix during autumn 2022. This project benefited from the guidance of the course’s co-instructors: Heather Howard and Daniel Meuse, two national healthcare policy experts who lead the State Health and Value Strategies program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, located at Princeton University.

According to the 2020 Census, 87,146 people currently reside in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI). This represents an 18% decrease in population since 2010. 2 The USVI’s population decline was exacerbated by the devastation of Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, after which many residents left the territory. 3 However, the population decline began in the years leading up to the hurricanes; 11,000 residents are estimated to have emigrated from the USVI prior to 2016 in response to economic issues detailed in the following section. 4

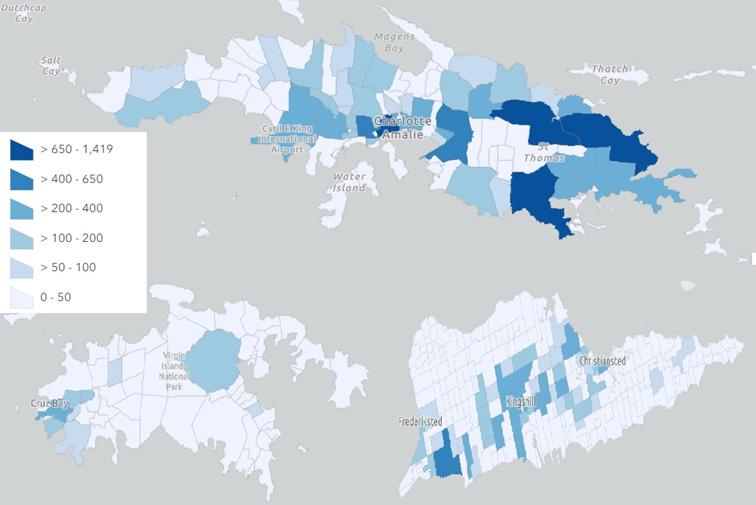

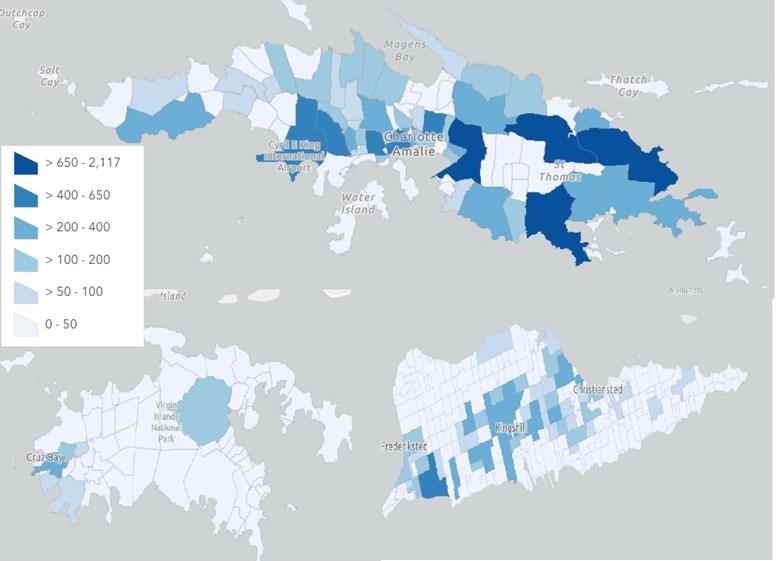

A summary of the USVI population by race, age, and income course is provided in figure 1 below. While this report uses population figures from the 2020 Census, a number of stakeholders interviewed throughout our research reported concerns with the accuracy of the 2020 Census, noting challenges around data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stakeholders suspected that the number of residents without legal immigration status in the USVI were undercounted in the Census, potentially out of fear of speaking to government representatives. We provide an estimate of the undocumented population residing in the USVI in Appendix b.

The reported population decline is associated with a 27% decline in the local economy, measure d by real Gross Territorial Product, from 2008 to 2016. 5 The USVI lost an estimated 6,000 jobs during this period of economic recession.6 An additional 4,300 USVI residents filed jobless claims after the 2017 hurricanes, representing a loss of roughly 8% of all jobs in the territory.7

These economic challenges have exacerbated poverty rates in the USVI, which are significantly higher than national rates. 8 The median family income in the USVI is $52,000, compared to the national median family income of $67,521. In 2020, 22.8% of the USVI’s population lived in a household where the household income was below the federal poverty level. Child poverty rates were particularly high, with 33% of children under 18 living in a household with household income below the federal poverty level.9

High poverty rates correspond to higher health risks among the USVI’s population across multiple chronic disease areas. Obesity rates in the USVI are higher than the national average: 32.2% of adults reported a body mass index of 30.0 or higher in USVI in 2016, compared to 30.1% of U.S. adults nationally. Diabetes is also more prevalent, with 16.8% of USVI adults reporting having ever been told they had diabetes, compared to 10.5% of adults nationally in 2016. Residents who are Black, non-Hispanic, older, lower income, and with lower levels of education were all more likely to have been diagnosed with diabetes.10

One contributing factor to these health outcomes may be the limited access to preventive care in the USVI. In 2016, USVI estimates of preventive service uptake lagged behind national figures across a range of critical services, including prenatal care, routine mammograms and colonoscopies, and child vaccination.11

Healthcare remains unaffordable for many residents in the USVI. As a result of high health service costs, many forego care: 22% of people in the USVI report that they were unable to see a doctor due to high costs in the past year, compared with 13% of individuals surveyed in the 50 states and D.C.12

However, all USVI residents are guaranteed care, regardless of income or insurance status. A statutory requirement added to the USVI Code in 2019 states “no resident of the Virgin Islands shall be denied medical care because of financial inability to pay.”13 While this requirement is critical to ensuring access to care, it also creates financing challenges for the hospitals and clinics in the USVI when patients are unable to pay for services. As a result, Juan F. Luis Hospital estimates roughly $40 million per year in uncompensated care.14 While the territory allots some funding to reimburse facilities for uncompensated care, it is not sufficient to cover the full costs.

While the USVI has made notable strides toward expanding health insurance coverage over the last few years, 24.6% of the population still lacked coverage in 2020.15 This uninsured rate remains well above national uninsured rates – 6.6% in Medicaid expansion states and 12.7% in non-expansion states.16 Among the remaining three quarters of the USVI’s population, 46.6% had private health insurance in 2020 and 37.2% had public insurance coverage.17 The share of residents with public insurance has increased further over the last two years due to the continuous coverage requirement that prevents disenrollment of Medicaid enrollees during the public health

emergency (PHE). This is further discussed in the section below regarding COVID-19 policy changes.

USVI residents have limited options for health insurance coverage. Like other states and territories, the fair market rules of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) that are meant to protect consumers apply to the insurance markets of the USVI. These include guaranteed issue, restrictions on annual and lifetime caps, and protections for those with pre-existing conditions. However, unlike states, the USVI does not have access to the subsidies offered in the ACA that typically protect the stability of the insurance market while providing affordable coverage to consumers. As a result, no individual health insurance plans currently exist in the USVI. All private insurance plans are offered to large groups or through employers. Roughly a quarter of residents covered by private health insurance in 2020 were enrolled in the territorial government insurance plan offered by Cigna.18

Emigration has left a shortage of doctors and other healthcare providers in the USVI.19 In our interviews, stakeholders reported that attracting and retaining new providers is difficult given lower local salaries than those in the states. Additionally, the lack of specialist providers practicing in the territory results in the frequent need for residents to fly to Puerto Rico or the mainland for care.

Each of the USVI ’s three largest islands, St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John, are designated Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA) for primary care services, and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) estimates that 15 additional primary care providers are required to fill the access gap. 20 This would represent a 21% increase from the current 72 primary care providers. 21

In 2016, an estimated 23,177, or 22%, of Virgin Islanders received health insurance from Medicaid or the Children ’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). As of September 2021, that number had increased to 34,158 individuals, meaning as much as 39% of USVI’s population is now enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP. 22

The USVI’s Medicaid program offers 13 of the 15 mandatory Medicaid benefits (figure 2). Additionally, the program offers two optional benefits to enrollees: prescription drugs and dental services.

The USVI has historically faced two key restrictions on federal funding for its Medicaid program.

First, the USVI has a statutory annual cap on federally matched funding, while federal funds to the 50 states and D.C. have no such cap. Second, the USVI’s Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP) is statutorily set, unlike the FMAP for the states, which is calculated annually based on each state’s per capita income. 23 While the ACA raised the FMAP for the USVI from 50% to 55%, this match rate still amounted to insufficient federal funding levels for the territory, given that the rate would have been 83% if it were calculated using the same methodology as the states. 24 However, these federal funding limitations have recently been addressed, detailed in the next subsection.

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically altered the federal funding landscape for Medicaid in the USVI. The USVI saw an unprecedented influx of

✓ Inpatient hospital services

✓ Outpatient hospital services

✓ EPSDT: Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment Services

✓ Nursing Facility Services

✓ Home health services

✓ Physician services

✓ Federally qualified health center services

✓ Laboratory and X-ray services

✓ Family planning services

✓ Nurse Midwife services

✓ Certified Pediatric and Family Nurse Practitioner services

✓ Transportation to medical care

✓ Tobacco cessation counseling for pregnant women

x Rural health clinic services

x Freestanding Birth Center services

federal health funding beginning in Fiscal Year (FY) 2020, when the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) increased the USVI’s federal funding cap from $18.3 million to $128.7 million. Additionally, throughout the pandemic, Congress temporarily raised the FMAP to the maximum rate of 83% for the USVI through a series of short-term funding bills. This change was recently made permanent in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 (H.R. 2617), signed into law at the end of 2022. 25 This is a critical step toward ensuring the continuity of new services offered under Medicaid during the pandemic, including a personal care attendant program, a hospice benefit, and assistance for Medicare

premiums for some dual eligible residents. 26 Additionally, the FFCRA included a provision that required states and territories to provide continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees throughout the PHE to receive enhanced federal funding. 27 This provision has increased Medicaid enrollment by 28% nationally since the start of the pandemic and has benefitted a significant number of USVI residents. However, the recent Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023 set the end of the continuous coverage requirement for March 31, 2023. 28 Now, the USVI faces the challenge of implementing a redetermination process that may result in the loss of coverage for thousands of residents.

USVI, including government, health facilities, and non-governmental partners.

We collected information for this report in two stages. First, we conducted a literature review of the USVI’s health system context, key challenges, and current and past policies affecting healthcare delivery in the territory. Second, we conducted 13 interviews with USVI-based stakeholders from October to November 2022. These interviews allowed us to incorporate the perspective of 27 stakeholders in this report, representing a range of organizations across the

In the following report sections, we outline recommendations to improve health insurance coverage for U.S. Virgin Islanders developed based on our research and stakeholder interviews. Recommendation 1 first focuses on the core proposal to design and implement a Medicaid buy-in program. Then, Recommendations 2 through 5 provide broader health system strengthening strategies to enable successful implementation of the Medicaid buy-in program.

To evaluate the recommendations, we used a decision matrix and scored each recommendation based on the following criteria:

External Considerations: These factors provide estimated impacts of each recommendation on USVI residents based on how they are able to access and afford healthcare in the territory. Recommendations that have a positive, direct impact on health access and outcomes receive a higher score than recommendations with limited or no impact.

• Access to Health Insurance: How will this recommendation impact the ability for USVI residents to navigate insurance options and enroll in health insurance in the territory?

• Access to Care: How will this recommendation impact the ability of USVI residents to see providers and receive care in the territory?

• Territory Health Outcomes: How will this recommendation impact health outcomes for residents in the USVI, including disease burdens affecting the territory such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity?

Internal Considerations: These factors provide determinations for the USVI government

and healthcare stakeholders to consider when implementing each recommendation, based on estimated cost, political feasibility, and burden on agencies and their staff. Recommendations which are more politically feasible and less costly and burdensome to the USVI government are scored higher than more expensive recommendations which may require broader agreement, legislation, and/or federal approval to implement.

• Administrative Burden: What is the capacity of the territory’s government agencies to implement this recommendation, given their current resources and staffing levels?

• Financial Impact: What is the cost of this recommendation to the USVI government, in terms of its territory budget? Will it require new local territory funds to implement?

• Political Feasibility: Does this recommendation require legislative action or approval from the federal government to implement? If so, how likely is it that the recommendation will get approved or passed into law? Will healthcare stakeholders in the territory be broadly in support of or against the proposals of this recommendation?

Recommendation 1: Establish a Medicaid Buy-In Program

Identify the eligible population and determine an income threshold.

Establish a premium structure and use the remaining Medicaid funds allotted to the USVI to subsidize premiums.

Adjust the Alternative Benefit Plan for the Medicaid buy-in population.

Design a marketing strategy to promote take-up of the Medicaid buy-in program.

Recommendation 2: Expand Health Education Measures and Improve

Promote the importance of preventive care through individual patient interactions and broader community outreach.

Educate residents about the benefits of health insurance.

Recommendation 3: Address Provider Shortages

Partner with the UVI Medical School. Adopt medical compacts to facilitate provider licensing. Increase telehealth utilization.

Leverage health workforce development funds to increase provider supply. Improve care coordination.

Recommendation 4: Improve Coordination Between Different government Agencies and Departments

Create a new Healthcare Cabinet, a cross-agency task force that meets regularly to discuss healthcare policy, programs, and insurance.

Develop a centralized government healthcare website for USVI residents to reference consolidated access points to care and information on government and community healthcare resources.

Recommendation 5: Enhance Health Data Collection, Analysis, and Coordination Practices

Improve collaboration between DOH and health facilities for data sharing.

Train interested DHS and DOH employees in data analysis.

Establish the Health Information Exchange as a centralized data repository for population health tracking by expanding patient inclusion.

Our primary recommendation for increasing health insurance coverage and improving health outcomes in the USVI is to establish a Medicaid buy-in program. This recommendation was motivated by two factors: the USVI is a high risk market for potential private insurers and the USVI receives limited federal contributions towards paying for its healthcare costs.

When we thought through how to increase health insurance coverage in the USVI, we identified three factors that make the USVI a high risk market to private insurers. First, the USVI’s relatively small population makes it challenging for insurers to operate a profitable market, since a smaller population implies a smaller risk pool (i.e., there are fewer healthy and relatively lower cost people to help offset the higher costs incurred from those with greater healthcare needs). Second, the high chronic disease burden also implies higher healthcare costs. Third, fair market rules such as guaranteed issue, protections for those with pre-existing conditions, and no annual or lifetime limits, when applied to insurance markets, make insurance premiums more expensive. Because the USVI is not statutorily eligible for ACA subsidies designed to reduce the risk and cost of providing health insurance under these market rules, there is little incentive for insurers to enter the USVI market. Given the lack of an individual insurance market, we wanted to identify an insurance coverage option that could be administered through the USVI government.

Considering both funding limitations and the need for affordable insurance coverage for those who are currently uninsured or who do not have other opportunities to purchase insurance, we chose to focus on four key populations in the

USVI: residents who either 1) earn just above the Medicaid income limit, 2) are self-employed, 3) are employed but whose provider does not provide health insurance or 4) residents who will lose their current Medicaid coverage after the continuous coverage requirement expires at the end of the PHE. Our decision matrix provides further detail on each recommendation’s feasibility and likely impact.

Medicaid buy-in programs have attracted the attention of several state and city governments throughout the country as a way to expand health insurance options for those with limited to no insurance options. Medicaid’s per enrollee costs have grown more slowly compared to other payers, 29 which makes providing Medicaid and Medicaid-like coverage an appealing option to policymakers. In recent years, fourteen states have explored Medicaid buy-in programs as an alternative insurance option, mostly through commissioning studies or proposing legislation. 30 However, states often look into Medicaid buyin programs as a way to increase competition in their state marketplaces, which would lower premiums. While such Medicaid buy-in programs in the states are typically not eligible for federal match, the USVI may be able to establish a Medicaid buy-in program that is eligible for federal match given its lack of a marketplace.

For the USVI, a Medicaid buy-in program could provide many residents who currently lack health insurance the opportunity to pay a monthly premium for Medicaid-like insurance coverage. While Medicaid currently does not require premium

contributions or other out-of-pocket payments towards the health services used, a Medicaid buy-in program would require enrollees to make income-based premium contributions (i.e., pay a premium on a sliding scale). A Medicaid buyin program would provide Virgin Islanders who earn more than the Medicaid income limit an affordable health insurance coverage option and potentially improve health outcomes.

Since the USVI does not have an individual insurance market, it would encounter a different set of challenges when implementing a Medicaid buy-in program. The following sections outline financing and implementation recommendations for establishing a Medicaid buy-in program.

we recommend four next steps to design and implement a Medicaid buy-in program:

1. Identify the eligible population and determine the income eligibility threshold

2. Establish a premium structure and use the remaining Medicaid funds allotted to the USVI to subsidize premiums

3. Adjust the Alternative Benefit Plan for the Medicaid buy-in population

4. Design a marketing strategy to promote takeup of the Medicaid buy-in program

Identify the Eligible Population

The Medicaid buy-in program for the USVI should focus on the most economically vulnerable population not currently covered by an insurance program. In the USVI, this is the population that makes just above 133% of the USVI poverty level (USVIPL), the current income limit for the territory’s Medicaid program. Extending this eligibility up to 400% of the USVIPL would allow other uninsured Virgin Islanders to access health insurance, bring in patients who could potentially afford premiums, and diversify the risk pool.

An alternative approach is to focus on population groups with certain disease burdens, such as hypertension or diabetes. However, since this population would need to utilize the healthcare system more on average than other USVI residents, the cost of insuring them through Medicaid would make insurance premiums unaffordable without subsidies by the local government. Targeting the Medicaid buy-in program to the population within a defined range above the current Medicaid income limit would provide a more stable risk pool for the program and make premiums more affordable.

groups that are currently covered under medicaid based on income, asset, residency, and citizenship criteria:

• Pregnant women

• Children under age 21

• CHIP children under age 19

• TANF children and adults

• Blind and disabled

Note: Income standard for the categorically eligible for a family of one is $15,654. For Aged, Blind, or Disabled, for a family of one the standard income level is $20,833.

Expansion option 1 (Recommended)

Population with incomes between 133% – 400% (size dependent on cost) of the USVIPL

Expansion option 2

Population groups with disease burdens (e.g., hypertension or diabetes)

The first step to determining the optimal income eligibility threshold for the new Medicaid buy-in program would be to use claims data for the current eligible population to estimate a per-member per-month (PMPM) cost for the program. Claims data from the “expansion population,” or members whose incomes are between 100% and 133% of the USVIPL, would allow calculation of a PMPM that will be closer to the potential costs of the program for the population just above the current income limit. The USVI Medicaid Office should hire an actuary to do this analysis. This analysis should include sensitivities for the premium estimates based on available data on the disease burden and healthcare usage of the new Medicaid buy-in population. If the Medicaid buyin expansion population has a higher level of chronic disease, or if they are expected to utilize the healthcare system at a rate higher than other population groups, the estimated premiums might need to be higher to account for these larger expected costs of care.

Progress on this recommendation would require broad stakeholder support across the healthcare system for a new Medicaid buy-in program in the USVI. Implementing this recommendation would likely also incur additional administrative costs for the USVI Medicaid Office. Finally, estimating an accurate PMPM for the Medicaid buy-in population would depend on the depth of data available to the USVI Medicaid Office on healthcare usage and disease burden for this population, which may be a challenge given the lack of healthcare data currently available in the territory.

Establish a Premium Structure:

Once a PMPM rate for the new population has been estimated, the next step is to think through how a pricing structure would work for the program. Since the USVI government would not be able to fund a Medicaid buy-in program on its own, the sum of the premiums paid by Medicaid buy-in enrollees should cover the territory’s share of expected Medicaid costs for this new population. During our interviews, healthcare stakeholders in the USVI generally agreed that a premium between $50-200 per month would be an affordable range for the population earning between 133% and 400% of the USVIPL.

The premium could either be a flat rate for all enrollees in the new eligibility population or work as a sliding scale, in which lower-income enrollees pay a lower premium than enrollees with incomes closer to the top of the income range. A sliding scale may lead to unaffordable premiums for higher-income enrollees and reduce takeup of the program. However, without additional funding from the USVI government, a flat rate premium would likely not garner enough funds to cover the expected costs. Based on our conversations with stakeholders in the USVI, a sliding scale premium structure should be feasible for residents who earn between 133% and 400% of the USVIPL and who 1) do not have insurance options available to them through an employer, 2) are self-employed, or 3) will lose their Medicaid coverage once the PHE ends. Focusing on these populations would fill an existing gap in insurance coverage for USVI residents.

We recommend that the USVI hire an actuary to calculate the premium range after identifying the PMPM rate and estimated disease burden.

While premiums are necessary to fund a Medicaid buy-in program, relying on premiums alone would likely make costs too expensive for USVI residents. The USVI should rely on other funds to help subsidize premiums paid by residents. Through our conversations with USVI Medicaid staff, we learned that USVI’s Medicaid agency often does not utilize its entire allotted federal match (i.e., it does not spend enough local dollars on qualifying Medicaid expenditures to maximize the federal dollars the USVI could be getting from its 83% FMAP). For example, the USVI had around $40 million remaining in potential federal dollars available for Medicaid expenditures at one point during FY 2021. Since the USVI does not always use all of its potential Medicaid funding, it could potentially categorize Medicaid buy-in premiums as Medicaid spending eligible for federal match. For example, for every $100 spent by USVI residents on premiums for coverage through a Medicaid buy-in program, the USVI could be eligible for $488 in federal funding.

The USVI should engage with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to determine how premiums paid to a Medicaid buy-in program could potentially qualify for federal match. The USVI would likely need to either file a State Plan Amendment (SPA) or apply for a Section 1115 waiver, but should confirm a path forward with CMS.

Total federal match allotment (FY 2022): $131.4M

If the USVI spends $158.3M on Medicaid, they will get the full allotment in federal match. With a 83% FMAP, the USVI would be liable for $26.9M. $40M of the federal match allotment is unused per year, meaning the federal government is only reimbursing the USVI $91.4M. This means the USVI is currently spending $110.2M on Medicaid when it could be spending $158.3M to get the full match. There is $48.2M that could potentially be used to subsidize Medicaid buy-in premiums paid by residents. With the $40M match, $8.2M would be paid by residents via premiums. This scenario is illustrated in figure 6.

Identifying a suitable premium structure will rely on actuarial calculations based on several factors, including the PMPM rate, risk pool, disease burden, and demographics. This will also rely on having adequate data on the aforementioned variables to make such calculations. Additionally, getting Medicaid buy-in premiums to qualify for a federal match will depend on CMS and their proposed path forward. Given the additional administrative burden involved with handling premiums, managing new individual intake, and filling out paperwork like an 1115 waiver application, additional administrative costs could pose a challenge given current staffing levels in the USVI’s Medicaid Office.

For Medicaid enrollees who are between 100% and 133% of the USVIPL, the USVI uses an alternative benefit plan (ABP). The Federal Employee Health Benefits Blue Cross Blue Shield Service Benefit Plan serves as the base benchmark plan. 31 When creating a Medicaid buy-in program, the USVI could either offer this same ABP to buy-in enrollees or create a new set of benefits tailored to the new population. A decision on whether to maintain the current ABP or offer a new benefit package to the buy-in population will depend on the results of the actuarial analysis. If the PMPM rate estimate is expected to be too high to support affordable monthly premiums, the USVI Medicaid Office should determine which benefits are leading to the highest costs for the program. These high-cost benefits could be removed or pared back for the new buy-in population to drive down their PMPM rate.

Additionally, the optimal benefits package would be tailored to support the buy-in population’s

unique healthcare needs. More information about these needs can be ascertained through available health data on this population or through interviews with community and other healthcare system stakeholders. This new benefits package could remove or pare back benefits that are not needed for the new buy-in population, determined based on their prior healthcare usage, or it could add or bolster benefits that are prevalent among the new population. However, without local funding to support the buyin program, it is more likely that a new benefits package would need to be less generous than the current ABP so that monthly premiums are affordable for enrollees.

If possible, maintaining the current ABP for the Medicaid buy-in population would provide the simplest approach to setting up the program and will reduce administrative barriers to enrollment. A new benefits package for the buy-in population would require USVI Medicaid office staff and providers in the USVI to understand how it differs from the ABP offered to the current adult expansion population, and it may also create confusion and frustration for enrollees when benefits change for those who move in between programs due to changes in their income. A single ABP for the population with incomes above 100% of the USVIPL would eliminate these differences and reduce friction in the Medicaid enrollment process.

Progress on this recommendation depends on available administrative capacity to design an affordable benefits package that meets the needs of the buy-in population while also resulting in affordable monthly premiums. If a new benefit package is created, there may be costs involved with providing information to consumers and providers on the differences in benefits offered to the traditional Medicaid population, the adult expansion population, and the buy-in population. A new ABP that deviates from the benchmark Federal Employee Health Benefits Blue Cross Blue Shield Service Benefit Plan may also require a waiver from CMS to ensure the

coverage is appropriate for the target population, which could require additional staff hours and resources.

Design the Marketing Strategy:

To ensure that the population eligible for the Medicaid buy-in program actually enrolls, the USVI should design a marketing strategy to increase awareness of the program and the benefits of being insured. The marketing strategy should outline the positive benefits of enrolling in the program to the skeptical uninsured population. There may be healthy USVI residents who do not see any benefit to having health insurance. USVI Department of Health (DOH) staff should design a marketing strategy that educates this population about the importance of having insurance in case of a health emergency or other sudden change in health status, as well as the importance of having access to affordable preventive care options. Sub-Recommendation 2.1 in this report further details strategies the USVI DOH and Medicaid offices can use to increase awareness of the benefits of health insurance for USVI residents.

This marketing strategy does not need to be limited to the new buy-in population; it may be advantageous to market to those who may be eligible for either the traditional Medicaid program or its adult expansion. Increased enrollment of healthier individuals will reduce the USVI risk pool and lower costs for everyone else in the program, potentially making premiums more affordable for the buy-in population.

Implement the Marketing Strategy:

The first step to implementing a successful marketing strategy is to ensure monthly premiums

are affordable for the target population. Even those who are aware of the program and its benefits will not sign up if the costs of enrolling are too high. Second, policymakers should conduct outreach and partner with community stakeholders to increase awareness of the buyin program, how it works, and how those who are eligible can sign up. USVI government officials should also work with providers to ensure they are aware of how people can buy-in to the program. When uninsured patients who may be eligible for the program access the healthcare system, providers should be prepared to explain the program and direct patients to people or resources to help with the enrollment process, if necessary.

Progress on this recommendation depends on available funding for marketing and enrollment assistance. Policymakers could consider lower-cost marketing options, such as outreach to providers and community healthcare organizations, if funds are tight. However, if funding is available to support marketing, traditional outreach methods such as radio, web, and print advertisements may also prove successful in reaching a larger population.

While a Medicaid buy-in program would fill a persistent gap in insurance coverage for thousands of Virgin Islanders, it would not come without financial and implementation challenges. Funding a Medicaid buy-in program through premiums alone would likely make premiums too expensive for Virgin Islanders. Given the budgetary constraints of the USVI government, it is also unlikely the territorial government would be able to allocate additional funds to a separate buy-in program. This makes obtaining a federal match on premiums paid to a buy-in program critical to success. This process relies on CMS approving a SPA or 1115 waiver, which comes with administrative challenges such as undergoing negotiation processes that can take months

or even years and working with contractors to evaluate (an 1115 waiver’s) outcomes.

The Medicaid buy-in program’s success is also contingent on enrollment levels and service utilization. If too few people enroll in the program or if there aren’t enough healthy people enrolled to balance out the risk from unhealthy people, then the risk may be too high. Low utilization of health services such as preventive care can also drive up overall healthcare costs. Strategies to address these challenges are discussed in Recommendation 2 .

Additionally, success of a Medicaid buy-in program could be hindered by issues related to provider participation in the program or provider capacity. However, the USVI already reimburses Medicaid costs at Medicare rates, so this should mitigate the risk that providers choose not to provide services to enrollees of the buyin program. Despite parity in reimbursement rates, provider shortages still persist in the USVI.

Strategies to address the provider shortage are detailed in Recommendation 3.

Care coordination between the government agencies and departments responsible for providing healthcare to USVI citizens will also be crucial to successful implementation of a Medicaid buy-in program. Strategies on how to improve care coordination are outlined in Recommendation 4 . Finally, collection, analysis, and coordination of territory-level updated population health data is needed to operate and maintain a Medicaid buy-in program. Strategies on how to collect and use such data are detailed in Recommendation 5.

If these administrative capacity and process challenges are addressed, a Medicaid buy-in program could provide thousands of Virgin Islanders with affordable quality health insurance that is currently non-existent due to the lack of an individual insurance market.

During our interviews, multiple stakeholders reported low health literacy as a barrier to preventive healthcare utilization in the USVI. Preventive care refers to any routine healthcare service aimed at preventing illnesses, disease, and other health problems, and includes screenings, checkups, and patient counseling. 32 Preventive care is critical to both maintaining a healthy population and avoiding medical costs associated with treating preventable disease.

Increasing USVI residents’ understanding and utilization of preventive care services would thus be critical to controlling health spending under a Medicaid buy-in program. Initial health costs could be particularly high as the risk pool expands to include residents who may previously have lacked access to preventive care services. Additionally, improving health literacy could improve the success of a Medicaid buy-in program by ensuring residents who qualify for the program have a clear understanding of how the program will improve their lives. This understanding would be key to promoting enrollment in the program.

This section outlines preventive care access in the USVI and shares key stakeholder takeaways about the barriers to accessing them. It then provides recommended strategies for increasing knowledge and uptake of healthcare services.

1. Promote the importance of preventive care through individual patient interactions and broader community outreach

2. Educate residents about the benefits of health insurance

The DOH has demonstrated its commitment to strengthening community health. We learned through our interviews about recent investments to build a new public health center that will focus on preventive care, behavioral health, and community education. The center will also include an onsite lab for testing and screening.

These investments will be critical in the USVI, where preventive service provision indicators lag behind national figures. For example:33

• Prenatal care: In 2017, 16.6% of births in the USVI had no prior prenatal care, as compared to 6% of births nationally. 34

• Routine screening: In 2016, 49.9% of USVI adults aged 50-75 reported having a colonoscopy in the last 10 years, compared with 63.3% nationwide. Additionally, 72.7% of adult women aged 50-74 in the USVI had received a mammogram in the past 2 years, compared with 77.5% of women in the same age group nationally.

• Child vaccination: Children in the USVI had the lowest rate of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination in the United States in

2017, at 70.5%. The national MMR vaccination rate for children in the same year was 90.8%. 35 Stakeholders reported lack of care-seeking behavior as a major challenge underlying low preventive care access. This was particularly believed to be a challenge among uninsured residents, who are perceived to seek primary care at lower rates than residents with Medicaid or employer insurance. However, preventive care-seeking is reported to be low among the insured as well. In our interviews, we heard that many people covered by the territorial government’s health insurance plan do not seek annual check-ups and mammograms despite these services being free as guaranteed by the ACA.

One underlying theme driving low preventive care-seeking behavior highlighted during our interviews is that many residents are unfamiliar with basic health insurance concepts and are unfamiliar with the benefits that health insurance provides. This is a problem of low health literacy, which is defined as the ability to navigate the healthcare system and make informed decisions regarding one’s own care. 36 Low health literacy is very common: half of Americans report that they do not understand basic health insurance terms and are not confident using health insurance to access care. 37 Low health literacy can lead to underutilization of preventive care, such as in cases where people may not understand what services are exempt from copays on their plan. 38 Accordingly, low health literacy is consistently linked to worse medical outcomes. 39

Increasing the health literacy of residents will help Virgin Islanders understand whether the Medicaid buy-in program is a good option for them, be more confident that they will be able to afford the care they need, and feel more empowered in their own care. Improving health literacy can increase both enrollment in the Medicaid buy-in program as well as utilization of services, which can help broaden the program’s risk pool and improve health outcomes.

Stakeholders also reported that cultural norms and misconceptions may also reduce care-seeking

behavior. Private doctors are viewed as the preferred health providers, and some view services from clinics as lesser quality and feel reluctant to use them. Residents may be further discouraged from using public health facilities if they are unable to pay, preferring to forego care out of pride. A desire to maintain privacy may also discourage care-seeking. People may worry about insurance providers accessing their personal health information following doctors visits.

In our interviews, we heard that these factors can delay care seeking behavior until issues become acute, and that this is especially common for patients without health insurance.

It is important to note that these barriers are not unique to the Virgin Islands. Underutilization of preventive care is widespread across the United States. Underutilization of preventive care also increases with higher unemployment, 40 and the USVI’s unemployment rate is usually higher than the 50 states. Utilization of preventive care is also closely associated with health insurance coverage, 41 and expanding access to health insurance is associated with significant increases in preventive care utilization. 42

Values and cultural ideas of health, gender, pride, and other factors can lead patients to delay preventive care or not seek it out at all. However, focusing too much on patients’ personal responsibility for neglecting their care can stigmatize patients and make them less likely to seek care.

In our conversations, we heard that Virgin Islanders will use traditional medicine and home remedies when they are sick. 43 Herbal medicine and prayer are common healing practices among Black Caribbeans. 44 We see this as evidence that Virgin Islanders do value preventive care, but that this care is currently not happening within the formal medical system.

Finally, even when people decide to seek primary care services in the formal medical system, they often face long wait times. SRMC Hospital reported that discharged patients may wait up to five weeks to have their first follow-up appointment. Both hospitals in the USVI reported that

primary care often ends up being delivered in the ER, which drives up ER wait times. Perception of long wait times can then further discourage care-seeking behavior.

In our interviews, we heard that there is currently insufficient public communication around the importance of and options for preventive healthcare. Focusing on health promotion and education efforts can help improve health literacy and increase utilization of preventive care within the territory.

Providers can serve as key educators in health literacy and use patient interactions to promote the importance of preventive care. Providers should understand that low health literacy is a risk factor for adverse outcomes, and should understand themselves as having a responsibility to explain concepts clearly, educate without judgment, and confirm understanding of important concepts, like the importance of preventive care.

To build on existing beliefs in the value of preventive care services, while moving those care-seeking behaviors into the medical system, we recommend encouraging healthcare providers to validate traditional medicine and home remedies rather than dismissing them, as long as they are not actively harmful. Providers could work with patients to understand evidence-based healthcare as being complementary to medicines they may be more comfortable and familiar with. Providers should respectfully listen and seek to understand patients’ use of alternative and complementary medicines to build trust and

facilitate information sharing within the provider-patient relationship. 45 Providers can also integrate alternative and complementary medicines into treatment, such as by identifying traditional foods and medicines that are compatible with a treatment plan for diabetes. 46

Additionally, public health leaders could consider using co-design to integrate patients into the process of creating and updating educational materials. Letting patients share their perspectives and recommendations for phrasing information in plain and accessible language produces more useful materials and increases the health literacy of participants, so they can be health literacy ambassadors in their own communities. 47 To the extent feasible, providing child care and compensation to participants could ensure a broad range of patients have the opportunity to participate in such a co-design process.

Finally, the USVI should expand outreach services to meet people where they are rather than requiring them to come to a healthcare center. Such outreach could include mobile service centers, partnerships with trusted community centers such as libraries, 48 or duplicating existing models such as the successful territorial partnership with the Diabetes Center of Excellence. 49

Implementing culturally-competent behavior-change programs will require significant resource investments, including both staffing, financing, and time. Clinical providers in the USVI already face high patient loads and may not have bandwidth for the additional work to design and implement new comprehensive community education programs. This recommendation would be more feasible if the USVI also further invested in strengthening a community health workforce. A robust cadre of community health workers would be best equipped for the type of community- and personal-level outreach required to successfully educate USVI residents on preventive care strategies.

USVI stakeholders reported a lack of general patient understanding around the benefits of and processes for enrolling in Medicaid. After qualifying for presumptive Medicaid eligibility, patients remain temporarily enrolled through the end of the following month. However, not all patients follow up to enroll in the program on a full and ongoing basis. Since patients cannot receive presumptive eligibility twice in the same year, they must be treated as uninsured if they seek care again within the same year without having converted to full eligibility. Because of the statutory requirement that no patient be denied service because of ability to pay, a patient’s insurance status will not affect their ability to receive care. This can further lead to a lack of urgency in enrolling in Medicaid for those eligible.

For many residents, a Medicaid buy-in program would be their first opportunity to have affordable health insurance in their adult lives. Health insurance is complicated, with its own language of copays, deductibles, in-network and out-ofnetwork, and other concepts that do not come intuitively to the average person. After enactment of the ACA, CMS created the Coverage to Care initiative to address this challenge by providing information to new enrollees on how to use their coverage and access primary and preventive care services.

The USVI Medicaid Office should use the CMS Toolkit for Making Written Material Clear and Effective to design fact sheets, handouts, and other written materials for potential Medicaid buy-in enrollees. 50 Because materials designed for patients familiar with basic health insurance concepts may not resonate with audiences who have never held health insurance, materials should define technical terms in plain language, break complex information down into manageable pieces, and use graphics when appropriate. 51

Concepts should be explained using analogies to more familiar terms: for example, a health insurance deductible is like an auto insurance deductible and a provider referral is like a job search referral. 52

To design education and outreach materials, the USVI Medicaid Office should work with community members and representatives to design materials that are accessible and culturally competent. This could follow the model of Insure Detroit , a partnership between researchers and community-based organizations during ACA implementation that worked with local focus groups to design a website and educational videos using storytelling techniques to promote health insurance literacy. 53

Materials and providers should also communicate how patient privacy is respected within the medical setting. We heard that in a small community, some people avoid care because they worry that their provider will share their personal information with other members of the community. This is an opportunity to invest in health literacy regarding patient privacy protections to remove a barrier to seeking care.

On the provider side, the USVI DOH should encourage healthcare providers to complete the health literate healthcare organization 10 item questionnaire. 54 This self-assessment allows providers to assess where they can better serve patients by integrating health literacy education into every aspect of their operations. The DOH should also encourage healthcare providers to establish or strengthen patient advisory boards to integrate patient perspectives and identify areas where providers can serve as key communicators. Finally, the DOH should host professional development trainings, eligible for continuing medical education (CME) credits, on educating medical providers on best practices for communicating information clearly and checking for comprehension.

The breadth of existing educational materials from other health literacy programs mean that

the USVI would not have to create new provider training curricula and community outreach materials. However, adapting these toolkits and documents would require resources for both language and cultural context translation and dissemination.

Additionally, overburdened health providers may not be able to attend professional development trainings. To mitigate this, patient communication best practices around health insurance could be incorporated into existing in-service and pre-service training modules. Offering self-guided curricula, such as the health literate healthcare organization 10 item questionnaire, can also facilitate providers’ ability to develop their communications skills at their own convenience.

Behavioral solutions to encourage people to seek preventive care can help change existing attitudes and habits related to preventive care and demonstrate the benefits of seeking more formalized preventive care. However, given the constraints and provider shortages that the USVI medical system is currently facing, behavioral change can only go so far. People cannot seek out preventive care if there are not enough healthcare professionals to supply it. While we believe

these solutions can help increase access and utilization, underutilization can also be a response to real lack of providers. These recommendations will become more feasible paired with strategies to address health workforce shortages. While effective evidence-based strategies to improve health literacy and patient outcomes are well-documented, health literacy is not useful if people cannot access healthcare. Even with a Medicaid buy-in program, many residents will still face barriers to care. The costs of care may remain high, the provider shortage may continue, and navigating the system may continue to be complicated. Accordingly, the effects of improving health literacy are limited by the ability of patients to use their new health literacy to actually access care. Further, any uninsured residents who cannot afford to buy into Medicaid will continue to face cost and access barriers even as health literacy improves.

Finally, we have provided a number of recommendations that focus on incorporating both community voices and traditional practices into health literacy efforts. Soliciting this input from a diverse array of community voices, rather than those who are frequently consulted, may require additional time and resources in order to achieve full community representation and buy-in.

During our conversations in the USVI, we heard from a variety of stakeholders that provider shortages posed a challenge to the healthcare system. As the USVI considers expanding Medicaid services to cover more people through a Medicaid buy-in program, the lack of availability of Medicaid providers could impact the success of the program. Increased demand could lengthen wait times for services, and diminish enthusiasm and desire to participate in a Medicaid buy-in program.

Implementing strategies to reduce provider shortages and maximize the efficiency of existing healthcare structures will strengthen the healthcare system as a whole, increase patient satisfaction for those who buy-in to the expanded Medicaid program, and reinforce the sustainability of the Medicaid buy-in program. As USVI healthcare stakeholders consider implementing a Medicaid buy-in program, we provide options for increasing access to providers within the program.

Strategies to address provider shortages:

1. Partner with the future UVI Medical School

2. Adopt medical compacts to facilitate provider licensing

3. Increase telehealth utilization

4. Leverage health workforce development funds to increase provider supply

5. Improve care coordination

Provider shortages are a national issue that has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic,

with rising patient demand while healthcare providers are leaving the industry in record numbers. The USVI is no exception to this challenge. The HRSA Bureau of Health Workforce designates HPSAs based on regions where the population-to-provider ratio demonstrates limited healthcare accessibility. As of September 30, 2022, the population of the designated HPSAs in the USVI was 207,477 for primary care, 207,238 for dental care, and 154,841 for mental healthcare. 55 Stakeholder interviews in the USVI confirmed the challenges of a provider shortage from a government, provider, and community perspective.

The USVI is pursuing a number of avenues to increase access and reduce health workforce barriers to the provision of care. In July 2022, the administration of Governor Albert Bryan Jr., approved $20 million to bolster USVI hospitals given staffing challenges. SRMC on St. Thomas and Juan F. Luis Hospital on St. Croix each received $10 million in American Rescue Plan Act funding to support recruitment and retention efforts. Governor Bryan, Jr. referred to this effort as, “The beginning of the giving to create an environment where we can attract medical professionals that can help treat us and give people the healthcare they deserve.” We heard from health system leaders and read accounts that this funding has helped address pressing workforce challenges. 56

Health leaders in the territory also mentioned that low Medicaid reimbursement rates and high administrative burden might have dissuaded providers from enrolling in Medicaid in the past. Recent changes by the Department of Human Services (DHS) to allow Medicaid authorization without referral have motivated providers to

enroll in Medicaid or continue seeing Medicaid patients.

Providers in the USVI are exceptional in their ability to play a wide variety of supportive service roles, in addition to their clinical duties, in order to meet the needs of their patients. However, the more responsibilities per patient assumed by a provider, the fewer patients they can see. A strong social service network – including municipal, nonprofit, religious and community-based organizations – is thus vital in every health system. Social support services help promote the overall well-being of a patient while addressing social determinants of health to achieve more equitable health outcomes.

Ensuring timely access to care is vital to the success of a Medicaid buy-in program, as increasing insurance coverage could lead to increased demand for health services. As a result, longer waiting periods to see a Medicaid provider could dissuade people from remaining enrolled in the Medicaid buy-in program. Individuals would be less inclined to pay for insurance if access fails to meet demand, or if there is a perception that making an appointment as a Medicaid member might be challenging. The following strategies aim to offset that increase in demand.

The University of the Virgin Islands (UVI) is in the process of building a new medical school, which holds great potential to increase the number of physicians in the USVI by educating a new generation of doctors. The UVI medical school intends to focus on recruiting and retaining those with roots in the USVI by reserving seats for residents. This focus will have long-term benefits for combating provider shortages and ensuring a robust primary care physician workforce in the future.

Medical professionals throughout St. Thomas and St. Croix will assist with clinical instruction

as preceptors for UVI students. The university also plans to offer away-rotations for students at other medical schools, presenting an additional opportunity for recruiting future physicians to the USVI. Creating a scholarship for those committed to practicing in the USVI after graduation, or maximizing participation in NHSC scholarship and loan repayment programs (described in more detail in section 3.4) could similarly support provider recruitment.

During medical training, UVI could send medical students for clinical rotations at Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and community health clinics. This would expose students to the benefits and challenges of working with underserved populations and may foster future career interests in these areas. In addition, UVI could consider the creation of an “Islands Track’’ as a specialty training track within its school of medicine, modeled after special-interest tracks at other US medical schools. Such a program would serve to identify, admit, and educate students about healthcare issues specific to the USVI, with the goal of increasing the number of students who return after the completion of their training. Specialty tracks provide motivated students with additional didactic and clinical training opportunities through special lectures, tailored clinical experiences, and mentorship programs.

Apart from efforts to recruit and retain student doctors, the medical school holds promise for energizing the region economically through the establishment of an academic research hub, a state of the art simulation lab, and other new infrastructure. The Economic Development Administration of the Department of Commerce awarded a $14.1M grant to the Medical School Simulation Center, located on the Albert A. Sheen campus on St. Croix. 57 The agency also awarded an $18.6M grant to the Medical Research and Training Lab on St. Thomas. 58

The UVI School of Medicine is currently in the process of accreditation with the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) and is preparing to

move to the next step in the accreditation process in 2023. The potential benefits of the UVI School of Medicine cannot be harnessed until accreditation is complete. Additionally, the creation of a specific track program within a medical school will cost money to design, implement, and operate. Most rural track programs in U.S. medical schools are funded by grants and have great variability in funding and administration. The UVI School of Medicine will be limited by these same constraints when evaluating the addition of special-interest programming to their curriculum.

Another strategy to increase the number of medical providers in the USVI is through the use of medical compacts. Medical compacts aim to ease the barriers associated with entering into medical practice by expediting the licensing process and decreasing administrative burdens for applicants. The overarching goal of these compacts is to encourage licensure with aim of increasing access to both in-person and telehealth services.

The Bryan-Roach administration has already identified medical compacts as an avenue for increasing access to healthcare in the USVI. In December of 2021, Governor Bryan signed Bill 34-0040 into law, which enabled the USVI to participate in the Nurse Licensure Compact. 59 Through the Healthier Horizons initiative, the Governor’s Office is also exploring additional interstate licensing compacts for several in-demand medical professions, including physical therapy, psychology, and emergency medical services. With the increased use of telehealth, these compacts may be particularly useful for increasing access to care, as the provision of telehealth varies by state and inter-state practice is not always permitted.

The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact (IMLC)

is another licensing agreement that has potential to ease physician licensure burdens in the USVI by streamlining and expediting the licensure process. This compact does not change a state or territory’s existing Medical Practice Act or impede its ability to regulate the practice of medicine, but allows for faster licensing for physicians already licensed in another state. Thirty-seven states, Washington D.C., and Guam already participate in this compact.60 In order to join the IMLC and other compacts, the USVI legislature would need to introduce and enact a bill authorizing the territory to join, with language that is consistent with other states that have already joined.

The Governor’s office has already laid the groundwork for participation in several medical compacts. With minimal costs and negligible work required to draft the legislation, the main obstacle will be ensuring broad support to pass it.

Telehealth utilization increased dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic and will likely be a permanent fixture of the healthcare landscape in the U.S. In 2021 alone, telehealth usage increased 38x compared to the pre-COVID-19 baseline.61 Increasing telehealth utilization in the USVI would not only help providers more appropriately triage care by directing patients who would normally go to urgent care or the emergency room for non-emergency cases to primary care, but would expand care access to Virgin Islanders who cannot easily travel to seek the care they need. It would also ease the care burden exacerbated by the provider shortage and lack of many types of services, including many forms of specialty care. Other benefits of telehealth include better continuity of care, decreased care costs, and improved quality of care.62

The USVI has already taken meaningful steps to increase telehealth utilization in the USVI, including identifying telehealth as one of the eleven initiatives specified in Governor Bryan’s “Healthier Horizons” healthcare reform agenda.63

The Virgin Islands Telehealth Working Group, established in January 2020, drafted the Virgin Islands Telehealth Act (“VI Telehealth Act”), which was submitted as a proposed bill to the Legislature of the Virgin Islands in June 2022.64 The VI Telehealth Act as proposed would establish insurance reimbursement parity for telehealth visits and increase both the number and types of providers available to Virgin Islanders if the telehealth provider registers with the Department of Health. The VI Telehealth Act would also work with the Nurse Licensure Compact signed into law by Governor Bryan in December 2021, which allows registered nurses and licensed practical/vocational nurses to have one multistate license and provide care both in-person and via telehealth. These provisions would directly address the provider shortage by incentivizing providers to see more patients via telehealth and expanding the types of providers available to Virgin Islanders.

Codifying the VI Telehealth Act could help the USVI lay a foundation of key policies and processes needed to effectively integrate telehealth into the USVI’s healthcare landscape. Establishing payment parity for telehealth visits for insurance reimbursement purposes and expanding the type and number of providers allowed to provide care to Virgin Islanders who currently cannot access the care they need will likely provide some much-needed relief to the USVI’s current provider shortage. Joining medical compacts like the IMLC and other profession-specific medical compacts would also increase the number of providers available to Virgin Islanders and reduce the administrative burden typically involved with allowing providers outside the USVI to provide care to Virgin Islanders via telehealth. All of these proposed flexibilities could attract more providers to the USVI.

Strong political support of telehealth from Governor Bryan and Legislators increases the likelihood of the passage of the VI Telehealth Act. However, the resources required to ensure providers have the technology needed to successfully conduct telehealth visits may be a limiting factor. The USVI’s 2021-2024 Health IT Strategic Plan clearly lays out a vision of how to empower patients and providers to use telehealth, but the implementation of such technology will require significant investment from the USVI government or other entities (e.g., ensuring providers have adequate telehealth technology and internet access).65 Current investments into improving the USVI’s broadband infrastructure include approximately $85 million 66 from the Federal Communications Commission to build out high quality fixed and mobile networks by 2027 and at least $25 million 67 from the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program (BEAD), which funds planning, infrastructure development, and adoption programs. These resources could help the USVI ensure providers and other stakeholders are equipped with the proper technology they need to successfully utilize telehealth.

The USVI can facilitate the long-term stability of the healthcare workforce by leveraging several existing programs and structures. These include maximizing participation in federal programs designed to recruit providers to healthcare shortage areas, creating healthcare career pipeline programs for young Virgin Islanders, and utilizing the skills of Advanced Practice Providers (APPs) as part of the healthcare team. HRSA offers scholarship and loan repayment services that could

be utilized by providers looking to practice in the USVI.

The National Health Service Corps (NHSC) has several programs that aim to alleviate provider shortages through the use of scholarships and loan repayment in exchange for a commitment to practice in a designated HPSA for several years. Applicable programs for providers in the USVI include:

• NHSC Scholarship Program: awards scholarships to students pursuing eligible primary care health professions training in exchange for a commitment to provide primary care in a HPSA.

• NHSC Loan Repayment Program: open to licensed primary care medical, dental, and mental health providers who are employed or seeking employment at approved sites.

• Nurse Corps Scholarship Program: Scholarship program for nursing students in exchange for a two-year commitment at an eligible healthcare facility.

• Nurse Corps Loan Repayment Program: Open to RNs and APRNs, supplies 60% of total outstanding loan balance in exchange for a two year service commitment in a Critical Shortage Facility (CSF).

The Nurse Corps Loan Repayment Program pays up to 85% of unpaid debt for registered nurses (RNs), advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), and nurse faculty (NF) in exchange for working in either an eligible nursing school, or a CSF.68

The HRSA also administers the Health Careers Opportunity Program (HCOP), which centers around eligible academic medical institutions and could be pertinent to the UVI School of Nursing, and in the future, the UVI School of Medicine. The program offers funding to high schools or professional degree programs with activities designed to support students who seek to enter into a primary care setting in a rural and/or medically underserved area. If utilized in USVI high schools whose students aim to matriculate into

medical programs, these funds could expand the reach and efficacy of health workforce pipeline efforts.69

In addition to focused programs such as those offered through the HRSA, general pipeline programs provide opportunities for mentorship, education, and exposure to a variety of healthcare careers for primary, secondary, and higher education students. These programs encourage young people from underrepresented backgrounds to pursue careers in medicine and public health. In 2019 Governor Bryan introduced a USVI Talent Pipeline Workforce Development Initiative targeting an array of industries, including health sciences. This initiative has objectives at every stage of learning, and relies on employer partners to inform, attract, acquaint, train, and hire candidates.70 ,71