Climate-Adaptive Migrationand Agricultural Resiliencein Guatemala’s Western Highlands

March 2024

TableofContents

PositionalityStatement

Acknowledgements

Acronyms

Glossary

ExecutiveSummary

Introduction

Methodology

Background

FindingsandRecommendations

Conclusion

Endnotes

2 3 4 5 7 8 12 15 25 37 39 44

OurTeam 1

The authors would like to acknowledge the experiences and identities that informed the report’s research and recommendations. The authors come from a variety of professional backgrounds, including immigrant rights advocacy, foreign policy, international development, agriculture, U.S. social policy, and education. Most of the authors are bilingual in Spanish and English, which allowed them to conduct interviews and research in both languages; however, none of the authors speak the Indigenous languages spoken in the Western Highlands Several of the authors have professional experience or have lived in Latin America, though none of the authors had direct experience living or working in Guatemala before writing this report

Several students identify as Latine and/or Indigenous and brought to the project a shared history of Spanish colonization. Others have experienced migration (documented and undocumented), poverty, lived in rural communities, or have lived in places shaped by racism and environmental injustice.

The team's diverse perspectives, policy interests, and networks resulted in many rich discussions about climate adaptation, agriculture, and migration. To avoid bias, discussions were held to set priorities in interviewing and questions were collaboratively written and refined as the project advanced

2 PositionalityStatement PositionalityStatement

Princeton SPIA policy workshop team with U S Ambassador to Guatemala Tobin Bradley in Washington, D C , September 2023

Acknowledgements

This report was produced by ten second-year MPA students and one MPP student under the guidance of Dr. Dafna H. Rand. It was edited by Lizabelt Avila, Caroline Kuritzkes, and Barghav Sivaguru and designed by Betsabe Gonzalez and Marissa Molina Quintana. The photos were captured by Sergio Rodriguez Camarena and Barghav Sivaguru

The report was written to fulfill the requirements of the Princeton SPIA MPA program It has been informed by interviews conducted between September 2023 and December 2023 All recommendations reflected in this report are the opinions of the authors and are not necessarily shared by Princeton University or the organizations and individuals interviewed.

The authors would like to thank the following organizations for sharing their expertise during in-person site visits in Guatemala, consultations in Washington, D.C., and virtual meetings. In particular, the authors would like to thank the smallholder Guatemalan farmers who shared their knowledge, experiences, and samples of their crops This report would not have been possible without their invaluable contributions to our understanding of the topic of study:

Organizations:

Catholic Relief Services (CRS)

Center for Global Development (CGD)

Cooperativa Agrícola Integral Santa Maria (Santa Maria Agriculture Cooperative)

Export-Import Bank (EXIM)

Mercy Corps

Ministerio de Agricultura Ganadería y Alimentación (Guatemalan Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food)

Pop N’oj

Red de Agricultores Tejutlecos (Tejutla Farmers Network)

Salem State University

USAID Mission - Guatemala

USAID Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC)

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)

U.S. Embassy - Guatemala

U.S. State Department Office of Central American Affairs

United Nations Food and Agriculture

Organization (FAO)

United Nations World Food Programme (WFP)

World Bank

3

Acronyms

CICIG - Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala (International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala)

CPF - Country Partnership Framework

CRS - Catholic Relief Services

DHS – Department of Homeland Security

FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

FDI - Foreign Direct Investment

FLW - Food Loss and Waste

GDP - Gross Domestic Product

GHG - Greenhouse Gases

IDB - Inter-American Development Bank

IFAD - International Fund for Agricultural Development

ILO - International Labor Organization

INGO - International Nongovernmental Organization

IOM - International Organization for Migration

IPCC - Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

MSME - Micro, Small & Medium-Sized Enterprises

NDC - Nationally Determined Contribution

NGO - Nongovernmental Organization

OAS - Organization of American States

SMEs - Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

TPS - Temporary Protected Status

UNGA - United Nations General Assembly

USAID- United States Agency for International Development

WFP- World Food Programme

4 4

This report adopts glossary terms from the Center for Global Development,₁ International Organization for Migration, Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO),₂ and Catholic Relief Services (CRS),₃ below

Termsrelatedtomigration:

Migration refers to “the movement of persons away from their place of usual residence, either across an international border or within a State” (IOM, 2019: 137).

Forced displacement refers to “the movement of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or humanmade disasters” (IOM, 2019: 55)

Circular migration is “a form of migration in which people repeatedly move back and forth between two or more countries” (IOM, 2019: 29) In the context of climate-affected borderlands, circular migration may prove useful to maintaining livelihoods

Temporary migration refers to migration “with the intention to return to the country [or area] of origin or habitual residence after a limited time or to undertake an onward movement” (IOM, 2019: 213). In the context of climate change, seasonal migration (circular temporary migration typically within the same country) often allows rural agriculture-dependent households to diversify their incomes.

Remittances are “personal monetary transfers, cross border or within the same country, made by migrants to individuals or communities with

whom the migrant has links.” They may be formal transfers sent through banking networks, or informal, distributed in-kind or as cash (IOM, 2019: 180)

Trapped populations are populations “who do not migrate, yet are situated in areas under threat, [ ] at risk of becoming ‘trapped’ or having to stay behind, where they will be more vulnerable to environmental shocks and impoverishment” (IOM, 2019: 220)

Climate migration is defined by the IOM (2019: 31) as “the movement of a person or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment due to climate change, are obliged to leave their habitual place of residence, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, within a State or across an international border.”

Environmental migration is defined by the IOM (2019: 65) as “the movement of persons or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive changes in the environment that adversely affect their lives or living conditions, are forced to leave their places of habitual residence, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, and who move within or outside their country of origin or habitual residence ”

5 Glossary

A sudden-onset disaster is “triggered by a hazardous event that emerges quickly or unexpectedly. Sudden-onset disasters could be associated with, e.g., earthquake, volcanic eruption, flash flood,” etc (UNGA, 2016a: 13).

A slow-onset disaster “emerges gradually over time. Slow-onset disasters could be associated with, e.g., drought, desertification, sea-level rise, epidemic disease,” etc (UNGA, 2016a: 13).

A hazard is “the potential occurrence of a natural or human-induced physical event or trend that may cause loss of life, injury, or other health impacts, as well as damage and loss to property, infrastructure, livelihoods, service provision, ecosystems and environmental resources” (IPCC, 2018: 551)

Vulnerability refers to “the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected Vulnerability encompasses a variety of concepts and elements including sensitivity or susceptibility to harm and lack of capacity to cope and adapt” (IPCC, 2018: 560).

Exposure refers to “the presence of people; livelihoods; species or ecosystems; environmental functions, services, and resources; infrastructure; or economic, social, or cultural assets in places and settings that could be adversely affected” (IPCC, 2018: 549).

Resilience refers to “the ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions through risk management” (UNGA, 2016a: 22)

Risk refers to “the potential loss of life, injury, or destroyed or damaged assets which could occur to a system, society, or a community in a specific period of time, determined

probabilistically as a function of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and capacity.” Disaster risk is understood to reflect the concept of “hazardous events and disasters as the outcome of continuously present conditions of risk” (UNGA, 2016a: 14).

Adaptive capacity is the “the ability of systems, institutions, humans and other organisms to adjust to potential damage, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequence” (IPCC, 2018: 118).

Adaptation is “the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects” (IPCC, 2014) This may occur through action that is incremental, or transformative

Termsrelatedtoagriculture:

Land tenure refers to “the relationship, whether legally or customarily defined, among people, as individuals or groups, with respect to land.“ Land tenure is an institution (i.e., rules invented by societies to regulate behavior) that defines how property rights to land are to be allocated within societies; how access is granted to rights to use, control, and transfer land; as well as associated responsibilities and restraints. Land tenure systems determine who can use what resources for how long, and under what conditions. (FAO, 2020).

Water-smart agriculture refers to agronomic practices that increase agricultural productivity and resilience through the restoration of soil and water resources The approach aims to overcome challenges of land degradation, drought, and erratic rainfall through improved soil and water management, rainfall capture, and irrigation systems, among other techniques (CRS, 2021).

6 Termsrelatedtoclimate:

The climate crisis is decimating economic livelihoods across the globe and exacerbating societal vulnerabilities. Those impacted by climate change often face two options: adapt in situ or migrate. It is no surprise that climate change is thus accelerating migration and displacement, both internal and across borders, as governments and the international system collectively fail to reduce dependence on fossil fuels and invest at scale in green economies.

Guatemala ranks ninth in the world for “level of risk to the effects of climate change”₄ and is among the most climate-vulnerable countries in the Western Hemisphere ₅ The Western Highlands – Guatemala’s mountainous region stretching from the city of Antigua to the Mexican border – is particularly susceptible to droughts, floods, rainfall variation, and other extreme climate events that have undermined agricultural systems, the principal livelihood source for rural and Indigenous Guatemalans Western Highlands departments also experience the country’s highest rates of emigration, mainly to the United States and Mexico ₆

As such, Guatemala provides an instructive case study for the impacts of climate change on human mobility, agricultural livelihoods, and inclusive economic development. This report explores effective climate adaptation and livelihood support strategies for those at the margins of Guatemalan society: rural and Indigenous agricultural communities in the Western Highlands. In essence, it examines the following question:

Which interventions have been most effective in 1) bolstering in situ climate adaptation, and 2) expanding migration decision-making in Western Highlands agriculturalcommunities?

The workshop team held in-person and virtual consultations with several U S and international organizations implementing projects that aim to improve agricultural and adaptive practices in the Western Highlands In December 2023, a field research team also traveled to the Western Highlands with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and visited several farming communities, cooperatives, and FAO project sites The report synthesizes insights from interviews and fieldwork with these organizations and Guatemalan producers and examines the impacts of climate change on agricultural livelihoods, mobility, and resilience

Through a multidisciplinary lens, the report evaluates interventions that hold high potential for scalability, spotlighting strategies, initiatives, and programs that are currently underfunded or under-exposed. It embraces a theory of change that recognizes migration (for those who decide to move) and improved agricultural practices (for those who stay in place) as both necessary and viable climate adaptation strategies. It highlights the need for interventions that foster agricultural resilience and treat migration as an inevitable, multicausal, and fundamentally human experience. Finally, it recommends inclusive and integrated approaches that empower marginalized sectors of Guatemalan society and contribute to shared prosperity for all Guatemalans.

7

ExecutiveSummary

Introduction

Guatemala, a nation of diverse landscapes and rich cultural heritage, is currently at a crossroads marked by demographic shifts, climate change, and a transforming political landscape. The country’s distinct demographic, environmental, and political conditions impact rural livelihoods and migratory patterns This report aims to comprehensively examine how these interconnected dynamics shape climate adaptation and migration decisions in communities of the Western Highlands

CurrentDemographics

The World Bank classifies Guatemala as an upper-middle-income country and the largest economy in Central America, with a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $95 billion in 2022.₇ However, the country’s relatively robust economic output remains highly concentrated, with approximately two-thirds of the population living on less than $2 per day.₈ Guatemala’s poverty and inequality rates are among the highest in Latin America and the Caribbean, and a large and underserved population – primarily rural and Indigenous – lacks access to basic services, formal employment, and economic opportunities.₉

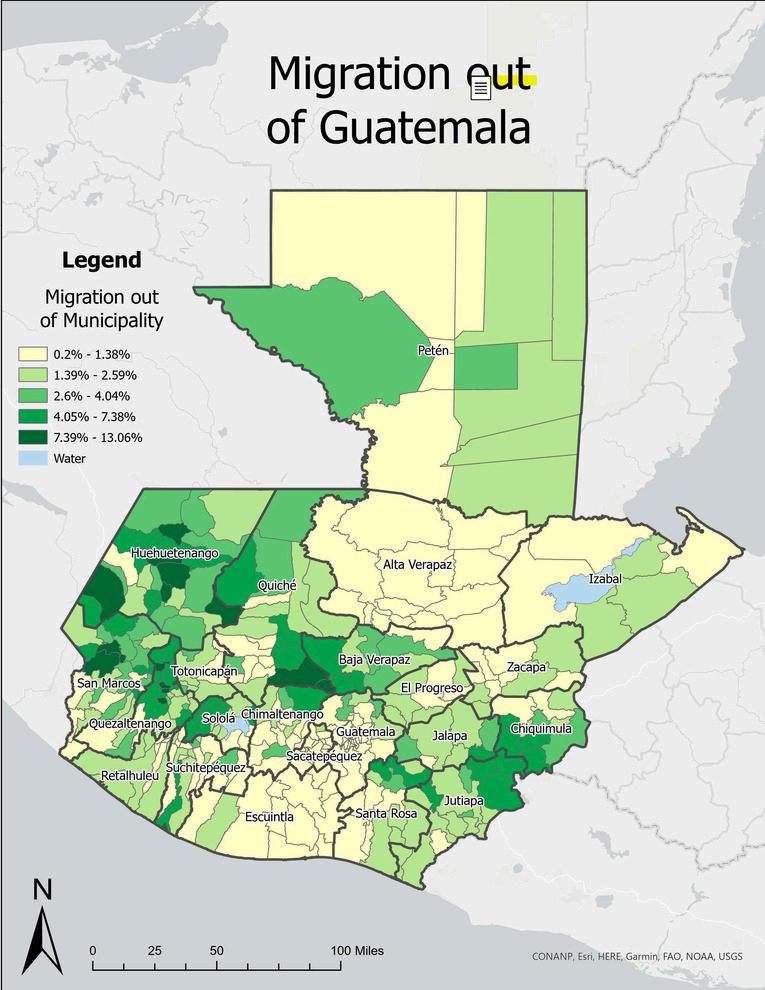

Of Guatemala’s 18 2 million citizens (2023 estimates), more than half live in rural areas and over a third are employed in the agricultural sector ₁₀ In recent years, Guatemala has been urbanizing as a result of internal migration from rural departments to urban centers driven by climate change and other factors ₁₁ The country currently outranks its Central American neighbors in net migration outflows and remittance receipts, with the Western Highlands departments of Huehuetenango, San Marcos, Quiché, Quetzaltenango, and Totonicapán reporting the highest emigration rates.₁₂

8

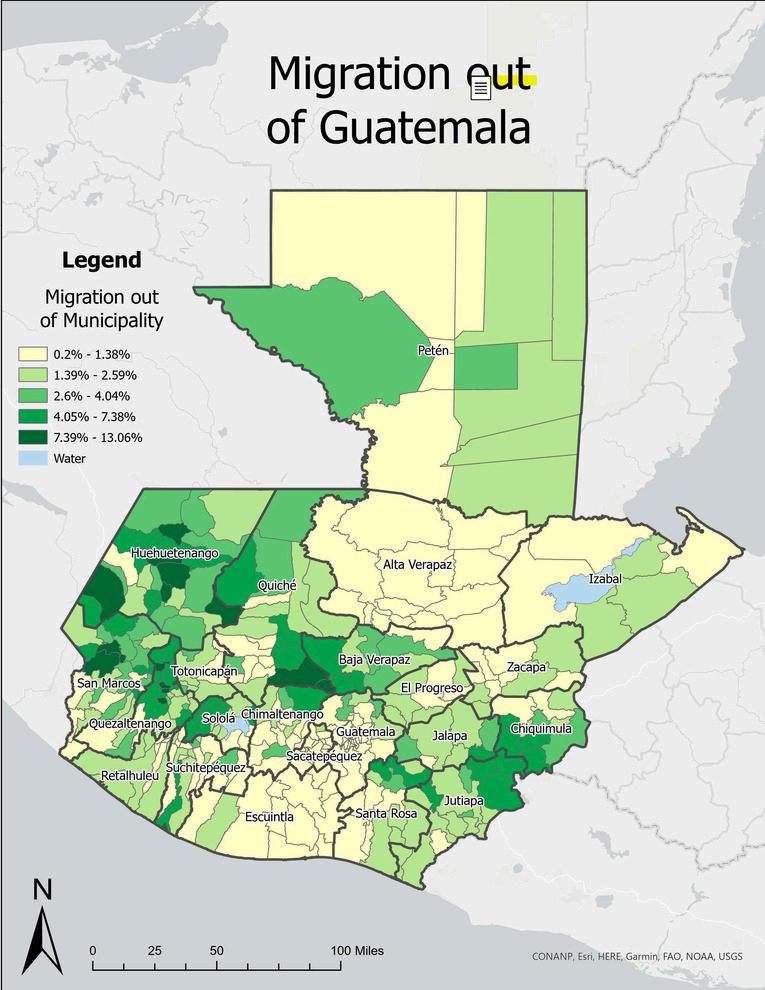

EmigrationRatesbyGuatemalanMunicipality (asPercentageofMunicipalPopulation)

Western Highlands departments of Huehuetenango, San Marcos, Quiché, and Quetzaltenango (location of fieldwork, circled above) report Guatemala’s highest per capita emigration rates.

Over 43 percent of Guatemala’s population identifies as Indigenous, the highest share in Latin America ₁₃ Twenty-two of the country’s 24 Indigenous groups are of Mayan descent and live in the Western Highlands in predominantly rural departments north and west of Guatemala City ₁₄ Indigenous Guatemalans experience higher rates of poverty, food insecurity, infant and child mortality, and illiteracy, among other drivers of out-migration ₁₅

Women in Guatemala face significant economic and social barriers, including greater obstacles to participating in the formal economy, owning property, and accessing credit and financing relative to men ₁₆

USAID estimates that only 37 percent of women participate in the formal labor market (compared to 85 percent of men), 27 percent own their own business, and 28 percent have access to financial markets (as opposed to 66 percent of men).₁₇ Nonetheless, women are often left behind by migrating male family members to oversee land tenure and other livelihood sources.₁₈ Indigenous women face increased land ownership barriers due to prevailing patriarchal norms against women’s inheritance or purchase of land Guatemala also has one of the highest rates of femicide in the world ₁₉

Nearly half of Guatemala’s population is under age 19, making it the youngest population in Latin America ₂₀ Guatemalan youth face substantial barriers to accessing educational and employment opportunities Over 2 3 million young people, or about a third of the school-age population, are not enrolled in school, and of the minority who complete secondary school annually (an estimated 150,000), only 50,000 secure formal employment ₂₁ Such disparities are especially acute in rural and Indigenous communities, where poverty and social marginalization continue to plague the capacity of Guatemalan youth to thrive ₂₂

Additionally, Guatemala has one of the highest child malnutrition rates globally, with nearly half of children (46 5 percent) chronically malnourished ₂₃ In 2022, food and nutrition insecurity reached historically high levels, with more than a quarter of Guatemalans – primarily subsistence farmers and households with minimal or no income –urgently requiring food assistance ₂₄ The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) projects continued humanitarian need in Guatemala as droughts, rainfall variation, and other extreme climate events accelerate human mobility and render subsistence farming less productive ₂₅

9

AccesstoLandandLandRightsin Guatemala

Enduring legacies of unequal land access and ownership depress agricultural livelihoods and exacerbate poverty and climate vulnerability among Indigenous producers, who have historically faced land dispossession and weak tenure protections under Guatemalan law ₂₆

Approximately 2 5 percent of Guatemalan farms own two-thirds of agricultural land and control most of the country’s vast and fertile tracts ₂₇ In contrast, subsistence farmers tend to occupy smaller, less productive plots at higher elevations in the Western Highlands ₂₈

Land distribution figured prominently in the 1996 Peace Accords and subsequent national agrarian policies; however, limited political will for comprehensive land reform has thwarted implementation ₂₉ Many Indigenous producers, lacking titles to parcels they have long occupied, face increased risks of courtordered evictions, land grabs, and disputes with large private landowners or neighboring farmers ₃₀ Still, those who can retain their land often suffer productivity losses due to declining soil fertility, overuse, and erosion ₃₁

CorruptionandHumanRights

Guatemala faces substantial challenges to human rights, citizen security, and the rule of law Journalists, advocates, and public officials who denounce organized crime and corruption risk retribution from political or criminal actors who enjoy high levels of impunity ₃₂ The climate of corruption and citizen insecurity has only accelerated migration outflows in combination with other push factors

Corruption affects many of the country’s public institutions₃₃ and cuts across several Western Highlands development challenges by depleting public resources available for rural infrastructure, health care, education, and service delivery.₃₄ Notably, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), an anti-corruption mechanism supervised by the United Nations, contributed to meaningful advancements in high-profile corruption cases ₃₅ However, CICIG’s mandate lapsed without renewal in 2019 under former President Jimmy Morales, who declared the commission a threat to national security ₃₆

In recent years, presiding justice officials have consolidated efforts to shield members of the Guatemalan political elite from criminal liability Attorney General Consuelo Porras, reappointed in May 2023 to a four-year term, has used her mandate to block high-profile corruption cases, weaken the Office of the Special Prosecutor against Impunity (FECI), and crack down on independent judges, prosecutors, and journalists ₃₇ Amnesty International documented 2,273 attacks against human rights defenders and those working in the justice sector between January and October 2022 ₃₈ The worsening climate of intimidation against judges, prosecutors, civil society, and the media has forced several prominent judicial reformers and human rights defenders into exile ₃₉

Corruption continues to undermine agricultural livelihoods in the Western Highlands by depriving the rural poor of equal access to justice, protection under the law (especially in the administration of land titling and tenure), and quality social services such as water, sanitation, and transportation infrastructure ₄₀

10

CurrentPoliticalSituation

In a stunning upset, anti-corruption candidate Bernardo Arévalo of the center-left Semilla Party defeated former first lady Sandra Torres of the National Unity of Hope Party (UNE) in Guatemala’s 2023 presidential elections.₄₁ The recently founded Semilla Movement grew out of widespread 2015 anti-corruption protests and has since maintained a focus on the rule of law, poverty reduction, and youth mobilization ₄₂ Arévalo’s victory illustrated deep public discontent with the political establishment and renewed hope for a reformist agenda

Throughout the fall of 2023, Guatemala’s Public Ministry made numerous attempts to invalidate the election results and disrupt a democratic transfer of power, which was far from assured Under Attorney General Porras’ leadership, public prosecutors repeatedly ordered the Semilla Movement’s suspension over alleged anomalies in the party’s registration ₄₃ In November 2023, the Public Ministry filed a request to strip Arévalo and his running mate of their immunity for past social media comments in support of student protestors, who in 2022 briefly occupied Guatemala’s sole public university ₄₄ In October 2023, frustration with judicial interference in the election outcome culminated in nationwide mobilizations, largely led by Indigenous groups, demanding Attorney General Porras’ resignation ₄₅

Amid the political turbulence, the U S Department of State₄₆ and Organization of American States (OAS) urged a safe, free, fair, and democratic transfer of power ₄₇ Despite opposition efforts to prevent a peaceful transition, Bernardo Arévalo was sworn into office on January 15, 2024

The report’s next section will discuss our research methodology: how we collected information, sourced data, and developed our understanding of complex multivariate phenomena.

11

Methodology

ResearchQuestionandTheoryofChange

Against this backdrop, the report aims to identify effective interventions that 1) bolster in situ climate adaptation and 2) expand migration decision-making in Western Highlands agricultural communities. It evaluates policies that hold high potential for scalability, spotlighting strategies, initiatives, and programs that are currently underfunded or under-exposed. It embraces a theory of change that recognizes migration (for those who move) and improved agricultural practices (for those who stay in place) as necessary and viable climate adaptation strategies.

Together, the report’s recommendations highlight opportunities for increased scale-up, funding, policy attention, and coordination that can effectively build on the strengths and capacities of existing development programs. They also point to areas where the Guatemalan government and development partners can capitalize on the window presented by the Semilla Party’s transition to help drive lasting, locally informed change. To that end, the report identifies interventions ripe for enhancement, replication, or expansion in Guatemala’s current political context and implementation landscape.

12

ResearchProcess

The workshop team conducted in-person and virtual interviews from September-November 2023 with a broad array of stakeholders based in Guatemala City and Washington, D.C., including representatives from government offices and agencies, NGOs, academia, and civil society (for an exhaustive list of interviewees, please refer to “Acknowledgements”) Five team members also traveled to Guatemala with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in December 2023 and conducted four days of site visits to ten FAO projects in the Western Highlands, including the villages of Cuya, La Esmeralda, and Tzalé (in San Marcos department) and Xexuxcap, Xoloché, and Xix (in Quiché department) The field research team held numerous meetings with FAO local staff, agricultural producers, women’s cooperatives, and the Guatemalan Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food (MAGA) in these locations, as well as agriculture and food security specialists from Catholic Relief Services (CRS) and the World Food Programme (WFP) in Guatemala City

These consultations helped inform a comprehensive understanding of the current programming landscape and recommendations that encourage a unified approach to climate adaptation, migration, agricultural resilience, and livelihood support in the Western Highlands Integrating topdown and bottom-up perspectives, the report bridges practitioners’ expertise with the realities and needs of agricultural producers impacted by climate change

The report’s recommendations are not intended as the only possible solutions Rather, they provide strategic suggestions that align with the unique aspirations and constraints of Guatemalan, U S , and international development partners As such, the report aims to highlight adaptive strategies that resonate with the diverse needs and capacities of a broad spectrum of stakeholders, including Western Highlands farmers, Indigenous communities, women, and youth

13

FAO and MAGA staff with producer from Tejutla Farmers Network in the village of Cuya, San Marcos department (December 2023)

ContributionsandLimitations

This report offers a holistic, though not exhaustive, treatment of climate-adaptive agricultural practices and migration behavior in the Western Highlands It does not seek to establish causal claims about specific migration drivers – due to the methodological limitations of disentangling the many factors underlying migration decisions – or empirically verify the effectiveness of ongoing programs and strategies It briefly touches on, but does not thoroughly address, climate-adaptive development in Guatemala City and other urban centers; U S immigration enforcement and deportation policies; refugee resettlement programs; and opportunities to make migration safer and improve conditions for migrants in transit, upon arrival at the destination, or upon return ₄₈

Nonetheless, the report contributes to the emerging nexus between human mobility, climate adaptation, and agricultural development First, it synthesizes in a single frame perspectives from diverse subfields (agricultural economics, governance and human rights, gender and Indigenous equity, and U S foreign assistance), organizations (U S government, multilateral, INGO, and Guatemalan civil society), and operational levels (D C headquarters, country offices in Guatemala City, and field visits in the Western Highlands) Such a multidisciplinary approach is consonant with the report’s view toward climate-related migration as a multidimensional phenomenon that requires policy attention from several domains and institutional angles ₄₉

Second, the report embraces an outlook toward migration as an inevitable, naturally occurring, and fundamentally human experience, while also recognizing the forces that push people to flee who wish to remain in situ For decades, U S foreign policy in Central America has optimized migration deterrence, whether by addressing the “root causes” of migration outflows (as emphasized by the Biden administration) or impeding migration inflows (the focus of the Trump administration) ₅₀ The report’s distance from U S donor priorities allows for a relatively neutral, clear-sighted assessment of U S and INGO programs on the merits of supporting climate-affected, migrantsending communities, rather than curbing immigration to the United States

Third, the report mainstreams gender and Indigenous equity considerations throughout its findings and recommendations Central to its objectives is the empowerment of marginalized sectors of Guatemalan society, including farmers, migrant-sending households, Indigenous communities, women, youth, and migrants themselves The report highlights how Guatemalan, U S , and international actors can uplift local solutions toward climate adaptation, agricultural resilience, and shared prosperity

14 ContributionsandLimitations

Background

TheStateofAgriculture,Challenges,and ImpactsonRuralandIndigenousLivelihoods

Given the overarching political, institutional, and economic challenges outlined above, climate change has magnified the hardships of rural, primarily Indigenous Guatemalans. Residents of the Western Highlands have long faced unique food, land, and livelihood stresses due to geographic isolation and lack of political power. Agricultural production rarely meets the country’s needs, and limited off-farm income opportunities are available to weather agricultural shocks or bridge the food availability gap, exacerbated by the region’s relative isolation from domestic trade. In sum, numerous economic, social, and environmental factors contribute to Guatemala’s agricultural challenges, which in turn drive rural poverty, food insecurity, and high migration outflows.

Agriculture accounts for the principal livelihood source in the Western Highlands and is dominated by smallholder maize-based cropping systems.₅₁ The typical farm in the region is a little larger than one acre, plants primarily for subsistence, and specializes in maize or a traditional maize intercropping system.₅₂ Some farms, however, diversify production with cash crops or specialized coffee production as a common alternative to maize-based planting.₅₃ Livestock is a small but important contributor to rural livelihoods and food availability.₅₄

Crop yields are typically poor, and there is significant food loss and waste (FLW) during production and after harvest due to a range of factors, including drought, natural disasters, nutrient deficiency, pests, disease, harvest inefficiency, and post-harvest handling.₅₅ Across Guatemala, nearly onefifth of maize is lost before it leaves the farm gate, a rate which is almost certainly higher in the Western Highlands.₅₆

15

Challengestoagriculturallivelihoodsand foodavailabilityintheWesternHighlands

Shortfalls in agricultural production, farm income, and off-farm income constrain livelihoods and food availability in the Western Highlands. Farmers must be able to produce enough food to eat or trade, rely on functioning markets and adequate commodity prices, and supplement their livelihoods with wages from one or more household members engaged in non-agricultural activities On all three dimensions, Western Highlands farming households face exceptional challenges

The most significant production constraint for Western Highlands smallholders is access to sufficiently large parcels of quality cropland ₅₇ Larger farms can grow more food with greater efficiency and diversification, and larger diversified farm households tend toward higher food security Land constraints in the Western Highlands are rooted in historical and demographic factors The Guatemalan Civil War (1960-1996) displaced Indigenous communities from their ancestral homelands, and only a fraction of Indigenous land has been restored since the war’s conclusion in 1996 ₅₈ The most fertile land predominantly remained with government allies A population boom in Guatemala further exacerbated land inequities, propelling the division of remaining farmland among large families into progressively smaller parcels ₅₉

Compounding this challenge is Guatemala’s lack of a basic land law ₆₀ Instead, the current tenure system is a patchwork of 89 separate pieces of legislation, including the 1973 Civil Code, which provides general principles on land possession, use, transfer, ownership, and registration, and the 1999 Fontierras Law, which aimed to expand land access through low-interest loans and government land purchases ₆₁

Western Highlands farmers frequently lack a legal claim to the land they occupy, leaving them vulnerable to land grabs or protracted ownership disputes.₆₂ Tenure insecurity drives disinvestment in what little land farmers have to plant and adds needless risk to the alreadyrisky business of smallholder farming.

Governance failures are a recurring theme in Western Highlands production shortfalls Guatemala has no established water resource management law to efficiently distribute scarce water supplies, substantially compromising water access ₆₃ Additionally, the Guatemalan government has historically underinvested in the Western Highlands’ transportation, energy, and telecommunications infrastructure, amplifying the region’s topographic isolation from the rest of the country These failures have increased the already high costs of agricultural inputs and capital Underenforcement against violence and narco-trafficking further augments costs and risks for the region’s producers, who face extortion and land grabs from criminal organizations, neighboring farmers, and multinational corporations ₆₄

These conditions have left Western Highlands producers largely unable to adopt the agricultural practices best suited to their circumstances ₆₅ Most farmers do not use fertilizer, mechanized equipment, or irrigation systems ₆₆ Crop yields are thus highly dependent on favorable weather and the availability of manual labor Obstacles to practice evolution are deeply rooted and systemic, owing to a mix of self-reinforcing factors, including undercapitalization, unmanaged risk, and lack of technical knowledge or assistance Agricultural risk drives disinvestment, which deprives farmers of tools to mitigate future shocks

16

Factorsbeyondproductivityfurther constrainagriculturallivelihoodsandfood availability

While crop yield is critical for subsistence households, agricultural value chains also affect farmers’ livelihoods in the Western Highlands The region’s underdeveloped infrastructure makes production more costly and compromises crop storage and transportation, which are essential to market access and trade ₆₇ Higher incomes and integration with additional markets in Guatemala, Mexico, and Central America are critical steps toward bolstering livelihoods and food security for subsistence farmers ₆₈

The Western Highlands’ economic isolation offers farming households limited off-farm income opportunities.₆₉ Even in advanced economies, off-farm income is an important source of financial risk mitigation, providing income stability in unfavorable crop years and savings in strong years. Off-farm income would provide a critical channel of investment and financing for capital-starved farms and the broader rural economy of the Western Highlands Instead, Guatemalan producers tend to rely on remittances from migrant family members to weather income shocks, support daily consumption, and finance household investments ₇₀

Climatechangedepressesagricultural livelihoodsandfuelsout-migration

Climate change is a force multiplier to many challenges faced by the region’s agricultural communities Increasingly unpredictable rain patterns, higher temperatures, and extreme weather events resulting from climate change are lowering agricultural yields and putting millions of Guatemalans’ food security further at risk ₇₁ The effects of these projections on livelihoods are likely to accelerate human mobility

While migration has long been a traditional component of agricultural life in Guatemala, increasingly, residents of the Western Highlands, especially youth, are migrating given the lack of viable socio-economic alternatives. A study commissioned by Indigenous rights NGO Pop No’j on the relationship between climate change, vulnerabilities (in agriculture, health, and living conditions), and migration in the Huehuetenango department of the Western Highlands uncovered three trends: 1) climate change’s negative impacts on agricultural productivity influenced decisions to migrate (especially among youth); 2) farmers who did not own their land were more likely to use migration as an adaptation mechanism; and 3) remittances played a critical role in offsetting higher production and food costs ₇₂ These observations shed light on important dynamics present throughout the Western Highlands regarding the impacts of climate change on agricultural livelihoods and migration’s potential to unlock a range of adaptive strategies

17

Producer demonstrates plowing equipment provided by FAO to the Tejutla Farmers Network (Cuya, San Marcos department, December 2023)

OverviewofProgramsSupporting In-PlaceClimateAdaptation

Guatemalangovernmentprogramsin climate-adaptiveagriculture

Recent Guatemalan administrations have implemented several programs to support farmers impacted by climate change through the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Food (MAGA), with a focus on rural extension services, crop insurance, and agricultural stipends.

Since 2013, MAGA has sought to revitalize Guatemala’s once prominent rural extension system through its Regional Coordination and Rural Extension Directorate (DICORER).₇₃ The program deploys teams of three to five municipal extensionists who provide technical assistance, inputs (when available), and training in crop management and sustainable agriculture to groups of farmers organized into rural development units known as CADERs.₇₄

Extension workers offer guidance on various practices, including soil conservation, livestock vaccination, crop preservation, and pest management, which CADER representatives then transmit to other producers in their network.₇₅ According to FAO, the program has reached an estimated 326,740 producers across 22 departments, 70 percent of whom are women. However, a 2018 study by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) found that extension services tend to prioritize wellorganized networks with existing investment capacity over units with smaller degrees of farmer mobilization, landless producers, and home gardeners unable to integrate into CADERs.₇₆

In February 2022, MAGA introduced a parametric insurance program in collaboration with the Microinsurance Catastrophe Risk Organization (MiCRO) and National Credit Mortgage Bank (CHN), which compensates farmers when rainfall or drought periods exceed certain thresholds.₇₇ The initiative’s proactive approach to climate resilience combines financial support with educational modules to promote holistic risk management.₇₈ However, farmers have shown limited interest in the program, as payments triggered by high-magnitude weather events, rather than crop damages or revenue losses, do not cushion directly against livelihood shocks.₇₉

Additionally, as of November 2023 MAGA’s Agricultural Stipend Program has reached an estimated 76,650 producers nationwide.₈₀ The program aims to help farmers improve crop yields through a 1,000 Quetzales conditional cash transfer ($128 USD),₈₁ which farmers can spend on fertilizer and tools in exchange for implementing soil conservation practices, verified by MAGA rural extensionists.₈₂

U.S.andinternationalinitiativesinclimateadaptiveagriculture

U.S. and international organizations operating in the Western Highlands are currently providing support to communities affected by climate change to adapt in place, rather than migrate or leave their land. Many of these programs involve traditional development approaches, and some but not all are framed around the objective of deterring migration. Both public and private stakeholders in Guatemala are working to shore up climate adaptation and agricultural resilience.

18

The United Nations system is a critical actor in food security, agriculture, and rural development in Guatemala, especially through the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and World Food Programme (WFP). While all of these agencies implement climate adaptation and agricultural resilience programs, FAO emphasizes technical assistance and disaster risk management, IFAD focuses on strengthening market access and entrepreneurial capacity, and WFP mainly provides immediate food relief and cash transfers ₈₃ Additionally, the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) is the second largest provider of Official Development Assistance (ODA) to Guatemala after the United States and has used its funding to support local farmers, SMEs, and producer associations to adopt climate-smart agriculture ₈₄

The United States is the single largest development donor to Guatemala Between 2012 and 2022, U S bilateral assistance to the country increased from $145 3 to $245 million, despite a brief decline from 20172020 due to Trump administration cuts ₈₅ Its Official Development Assistance ($205 million in 2020) also dwarfs that of other leading donors,₈₆ including the European Union ($37 million, largely supporting agriculture and food security programs); Sweden ($34 million, supporting industry, environmental protection, and the justice sector); and Spain ($32 million, supporting citizen security, nutrition, and water and sanitation programs) ₈₇

The majority of U S development assistance to Guatemala is implemented through USAID under the “U S Strategy for Addressing the Root Causes of Migration in Central America” and the 2020-2025 Guatemala Country Development Cooperation Strategy (CDCS) ₈₈

Broadly, USAID programs aim to reduce irregular migration by promoting economic prosperity and combating food insecurity, poverty, corruption, and gang violence, among other migration drivers.₈₉ The agency’s agriculture projects target Western Highlands departments with high migration outflows (especially Huehuetenango, San Marcos, Quiché, Quetzaltenango, and Totonicapán) as well as Indigenous communities, women, and youth as priority demographics ₉₀

Despite capital mobilization challenges, private financing holds some promise for climate adaptation in Guatemala, and the United States has taken several steps to promote foreign investment and small business growth Since 2020, the U S International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) has announced over $200 million in financing for Guatemalan commercial banks to catalyze local lending to SMEs, women-owned businesses, and rural borrowers in the Western Highlands ₉₁ Launched in February 2023, the Vice President’s “Central America Forward Initiative” has also mobilized over $4 2 billion in financial commitments from more than 50 companies for the region at large,₉₂ including to increase financial inclusion, farmers’ access to disaster risk insurance, and lending to Guatemalan SMEs and women entrepreneurs ₉₃

Despite these initiatives, SMEs and microenterprises in Guatemala face a substantial credit gap of roughly $14 billion ₉₄ The IMF notes in its 2023 Article IV Consultation in Guatemala that although bank credit to the private sector grew by 20 percent in 2022, small enterprises received roughly ten percent of lending by Guatemalan banks, while large and medium enterprises captured over half ₉₅ Additionally, while Guatemala netted over $22 5 billion in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) stock in 2022, bureaucratic impediments, corruption, and a weak judiciary continue to deter international investment ₉₆

19

To address these challenges, several Guatemalan ministries and the Bank of Guatemala signed the “Guatemala Moving Forward” plan with private sector partners in 2021, with the goals of facilitating a more favorable investment climate and addressing gaps in infrastructure, human capital, and regulatory reform.₉₇ Since the plan’s adoption, Guatemala has made some progress in enacting legislation aimed at attracting foreign investment, including by simplifying bureaucratic procedures and tweaking leasing laws ₉₈

Remittances represent another important climate adaptation mechanism in Guatemala Currently, Guatemala ranks eleventh among the world’s largest remittance recipients and second in Latin America and the Caribbean, with remittances accounting for 20 percent of the country’s annual GDP (2022 estimates)₉₉ and 50 percent of income for recipient households ₁₀₀ Studies by the IMF and others demonstrate the benefits to human and physical capital of an income supplemented by remittances: on average, Guatemalan recipient households spend a smaller share of their income on food and a greater share on goods like education and housing than nonrecipients ₁₀₁ Remittance-receiving households in Guatemala also have a higher percentage of micro-entrepreneurs, suggesting the additional income could help recipients overcome barriers to market access and channel investment into small businesses ₁₀₂

As an additional cash flow, remittances hold high potential to help Western Highlands households weather climate shocks For example, Mercy Corps has partnered with Remitly, a company that facilitates remittance transfers, to pilot a program in the department of Huehuetenango that provides warnings to remittance senders in advance of forecasted storms, allowing diaspora members to send timely stipends ahead of natural disasters

Such “anticipatory action” programs aid greatly in short-term climate adaptation: every dollar remitted saves an estimated $6 in losses due to climate damages.₁₀₃

Despite their considerable share of Guatemala’s GDP, remittances remain highly concentrated among households with family members who have migrated internationally –– particularly in the Western Highlands departments of Huehuetenango and San Marcos, which capture more than $600 million in remittances each year ₁₀₄ Some communities are changing this narrative by setting up “migrant co-ops” to pool remittances, loan them to non-recipients, and invest jointly in economic endeavors such as business and skills training to channel remittance income toward community-wide gains ₁₀₅

Indigenous producer in community of Xexuxcap, Quiché department (December 2023)

20

ContextofClimateChange

Complexitiesin migrationpolicyformulation

Despite increased migration outflows from Guatemala and other countries disproportionately affected by climate change, U.S. decision-makers have faced two critical challenges in policy formulation. First, they have struggled to establish climate change as a direct driver of migration, compared to economic and security aspirations, family networks, and other variables. Second, they have placed outsized importance on the power of foreign aid to alter conditions on the ground that contribute to migration. The result has been a misguided focus on migration deterrence over policies that aim to make migration safer and more accessible to those on the move in the context of climate change. A strategy that recognizes both human mobility as a naturally occurring phenomenon and the complex relationship between climate change and migration, as the Biden administration is increasingly moving toward, would most effectively support climateimpacted communities in the Western Highlands and migrants themselves.

First, economic, political, social, environmental, and personal factors all contribute to migration decisions, which often stem from dynamic and mixed motivations.₁₀₆ While policymakers have observed an intertwined relationship between migration, climate change, and agricultural economies, they have struggled to measure the direct impact of climate change on migration decisions relative to these other determinants. Challenges in establishing causality have precluded the adoption of specific migration protections, both in the U.S. and internationally, for those migrating either wholly or partially in response to climate change.₁₀₇ Still, policymakers are increasingly acknowledging sufficient evidence of the relationship between migration and climate change to address the two topics jointly.

In recognition of the impacts of climate change on migration, in February 2021 the Biden administration signed Executive Order (E.O.) 14013 to commission a report on the subject₁₀₈ and in December 2023 provided an update on actions taken.₁₀₉

Second, policymakers have overestimated the power of development aid to improve Guatemalan livelihoods and thus deter migration aspirations. This inclination has inspired a policy doctrine focused on the “root causes” of migration, most recently illustrated in the Biden administration’s “U.S. Strategy for Addressing the Root Causes of Migration in Central America,” which pledged $4.4 billion “to improve the underlying causes that push Central Americans to migrate.”₁₁₀ However, the hypothesis that development aid sufficiently improves economic well-being to slow emigration does not hold true in the data. Historically, economic growth has initially increased (rather than decreased) emigration in most developing countries due to a boost in disposable income, rising education and professional aspirations, and increased international connections.₁₁₁

Additionally, current levels of development aid have not been effective in raising household incomes to a high enough threshold at which emigration begins to taper off,₁₁₂ nor in reducing structural barriers to economic growth.₁₁₃ In practice, U.S. aid to Central America over the past decade has not significantly improved poverty or governance outcomes such as citizen security, anticorruption reform,₁₁₄ or the rule of law.₁₁₅ Support for poverty reduction and anticorruption initiatives through aid and diplomatic tools should be goals in their own right, but they must be disentangled from migration policy.

21 MigrationPolicymakinginthe

Migration has long been a recurring, natural adaptation to climate and other shocks in Guatemala. The effects of climate change, alongside demographic shifts and increasingly interconnected social networks, will likely increase human mobility in the coming years Given the dubious impact of development assistance on migration outcomes, U S policymakers should move away from a “root causes” approach that aims to deter emigration through foreign aid Instead, they should increase climate adaptation investments for Guatemalans who choose to remain in situ and seek to establish climatesensitive protection pathways for those who move, as reflected in the Biden administration’s E O 14013 that recognizes the inevitability of human mobility linked to climate change

MigrationresponsesbytheGuatemalan government

Over the past decade, Guatemalan government responses to climate-related mobility have been modest, despite the country’s long history of internal displacement, first as a result of the country’s protracted 36year civil war and more recently due to severe weather events and organized crime The country’s 2013 Framework Law on Climate Change, one of the first climate change laws in the world and a substantial mitigation and adaptation effort, established a National Climate Change Council to coordinate climate policies and strategies and regulate vulnerable sectors, including agriculture, natural resource management, and disaster risk reduction ₁₁₆ However, the absence of specific provisions for climate-related migration represents a notable gap in an otherwise comprehensive climate change framework ₁₁₇

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) currently lack official recognition and important protections under Guatemalan law.₁₁₈ To correct for this gap, in September 2023 Guatemalan Congresswoman Ligia Hernández (a founding member of the Semilla Party) introduced legislation to establish prevention, protection, and comprehensive care mechanisms for IDPs in Guatemala ₁₁₉ The proposed law features provisions to recognize IDP status, conduct studies on displacement conditions and settlement locations, and coordinate efforts to prevent and respond to displacement by addressing basic needs such as access to clean water, electricity, food, and housing ₁₂₀ However, as of this writing, the proposal has not been enacted into law

Apart from legal recognition and protection for IDPs, the Guatemalan government must also move more swiftly to assist those displaced by severe weather events through coordinated service delivery, resettlement, and return Unfortunately, weak policies and institutional capacity limit support available to IDPs An inadequate Guatemalan government response preceding and following Hurricanes Eta and Iota in November 2020 left hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans internally displaced and unable to rebuild or return, particularly in Western Highlands departments that already lacked public investment ₁₂₁ In Quejá, a community deemed uninhabitable after the hurricanes, alternative living arrangements proposed by the Guatemalan government almost two years later fell significantly below the affected population's standard of living and livelihood needs ₁₂₂ Additionally, the government neglected to help rebuild houses in neighboring New Quejá ₁₂₃ Over two years after the hurricanes, Refugees International reported in February 2023 that half of the individuals they interviewed were still unable to return home ₁₂₄

22

Migrationresponsesbyothergovernments andinternationalinitiatives

International responses to the impacts of climate change on migration are also either nascent or limited in scope, and very few affect Guatemalans. The Cartagena Declaration on Refugees has a more expansive refugee definition than the 1951 Refugee Convention and includes protections for people who flee their countries due to circumstances that disturb public order ₁₂₅ This broad framework was not meant to address climate change specifically, but could theoretically apply to climate-related natural disasters

However, while the Declaration has propelled some general protections at the national level, it is not legally binding Free movement protocols and protections against migrant return are two other formal tools that were not established to protect migrants in the context of climate change but could be leveraged under specific circumstances to support migrants affected by environmental disasters ₁₂₆ The 2006 Central America-4 Border Control Agreement, for example, allows people from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua to move freely between the signatory countries without a visa or passport; however, travelers are limited to 90-day stays, and there are no climate-specific protections ₁₂₇ Humanitarian protections that support Guatemalan migrants affected by climate change are practically non-existent Argentina created a humanitarian visa for disaster-displaced people from the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico, but it has not been fully developed ₁₂₈

In the United States, Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is the only legal pathway that mentions protections for people affected by environmental disasters Still, it has never been assigned to Guatemalans

To qualify, prospective TPS beneficiaries must be lawfully admitted to the United States and physically present on U.S. soil. Further, TPS holders are currently ineligible for U.S. citizenship or permanent residency unless they pursue those statuses through other immigration pathways.

In recent years, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security has introduced two parole programs open to Guatemalans to help relieve pressure at the U S -Mexico border: 1) the Central American Minors (CAM) program, a hybrid refugee-parole program open to qualified children who are nationals of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, and 2) the Family Reunification Parole (FRP) process, which allows beneficiaries from Guatemala, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Haiti, and Honduras to be considered for parole while awaiting visa availability for a familybased immigration petition However, neither program mentions climate or environmental disasters as a qualifying condition ₁₂₉

Labor mobility pathways to the United States are limited and lack a climate-specific lens The most notable work visas that affect agricultural communities in the Western Highlands are the H-2A visa, established for temporary agricultural workers, and the H-2B visa, for temporary nonagricultural workers In 2022, the U S granted only 2,978 H-2A visas and 6,289 H-2B visas to Guatemalans, which represented 0 01 percent and 0 06 percent respectively from the total amount of these two visa types granted to the 22 countries in the North American category ₁₃₀ More broadly, demand for seeking a better life in the United States is substantially higher than the existing supply of visas, a differential that contributed to 233,061 CBP apprehensions of Guatemalans in 2022, almost all at the U S -Mexico border

23

The United States has also implemented Safe Mobility Offices (SMO) throughout Latin America with the stated objective of expediting refugee processing and facilitating access to safe and lawful humanitarian and labor migration pathways.₁₃₁ The initial phase of the program began in Guatemala in June 2023, but the initiative has been limited to virtual screenings and information sharing rather than brick-and-mortar processing facilities ₁₃₂ Eligibility for an interview at the Guatemala SMO was at first open to other countries in Central America but quickly became restricted to Guatemalans ₁₃₃

Additionally, the Biden administration launched the CBP One app in 2023 as the formal channel through which asylum seekers could apply for an appointment with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) before reaching the U.S. border. However, asylum seekers have faced technical difficulties with the app, which reportedly employs facial recognition software unable to detect darker skin tones and requires high-speed internet connection inaccessible to those in transit. Appointments can take months to schedule due to limited availability, a luxury migrants with limited resources can scarcely afford ₁₃₄

The disconnect between high levels of Guatemalan migration to the United States and shortcomings presented by existing legal pathways, SMOs, and asylum initiatives point to a broader U S reliance on migration deterrence and failure to adopt and implement adequate protections. The Biden administration promptly eliminated some Trump-era policies that violated the right to seek asylum and restored initiatives like the Central American Minors (CAM) program.₁₃₅ At the same time, the United States maintained a deterrent approach through continued expulsions of asylum seekers under Title 42,₁₃₆ a new rule denying asylum to migrants who transited through third countries where they could have first applied,₁₃₇ and some public messaging.₁₃₈

U.S. and Guatemalan decision-makers should establish opportunities that effectively respond to human mobility motivated wholly or partially by climate change in light of ongoing humanitarian and climate adaptation needs.

24

Findingsand Recommendations

The following findings and recommendations were curated from meetings with stakeholders in the Western Highlands, Guatemala City, and Washington, D C The interviews were complemented by an existing body of secondary source research on climate change, migration pathways, and agricultural practices in the Western Highlands

8

25

Findings:BolsteringIn-SituClimate Adaptation

The most salient climate change impacts in the Western Highlands are water-related, including droughts, precipitation variability, and torrential rains that affect crop yields. Climate change impacts various crops in the Western Highlands in different and unique ways The honey market, for instance, is affected by climate change through unpredictable rains that delay and diminish productivity because the crop cannot be collected during rainfall Bees feed on stored honey during prolonged periods without harvest, thus reducing overall yields

Climate adaptation techniques often focus on water-smart agriculture, and the most effective practices typically combine technical assistance with ancestral and Indigenous knowledge. Technical support has included the use of greenhouses that enable farmers to plant in more controlled conditions, efficient fertilizers (especially those that can be made at home with existing resources), and adaptive technologies such as venturi injections, dells, and other water containers to capture rainfall.

Valuing ancestral knowledge, local organizing practices where farmers exchange best practices, and the role of women have proven instrumental in the success of capacity-building programs implemented by FAO and partners. Ancestral and Indigenous practices that have been mainstreamed into development work as regenerative agriculture include rotational crops, climate-resilient seeds, and agroforestry techniques like living plant fences These strategies have been informed by a deep knowledge of nature passed down through generations that has strengthened farmers’ adaptive capacity.

26

Greenhouses RainfallCapture

MulchingTechniques

Findings:BolsteringIn-SituClimate Adaptation

Access to finance is a critical pillar of climate adaptation, but climate risk insurance and credit opportunities remain limited. Climate risk insurance programs by the Guatemalan government are costly and narrow in coverage Despite a March 2023 ministerial agreement that aims to expand parametric insurance to 100,000 producers nationwide, MAGA’s insurance scheme is pegged to the occurrence of extreme weather events (namely excessive rain and drought) rather than the magnitude of crop losses. Most farmers view climate risk insurance as a gamble that does not pay off or an expense they cannot afford.

Multilateral organizations like FAO and WFP are implementing climate risk insurance programs through pilot projects. In 2021 WFP piloted a parametric insurance scheme that benefited 1,300 smallholder farmers, almost 70 percent of whom were women, and the 2022 scaled-up version benefited 9,437 people, 81 percent of whom were women ₁₃₉ FAO also provides Community Contingency Funds in the Dry Corridor that serve as insurance to farmers ₁₄₀ Catholic Relief Services is facilitating credit opportunities through saving and lending groups as well as encouraging companies that borrow funds to support farmers in two of four categories, including regenerative agriculture, job creation, women’s empowerment, and better prices for producers.

Investments in multi-purpose agricultural technology can have a catalytic effect in generating additional farm revenue. For example, FAO provided producers from the Tejutla Farmers Network a plowing machine, which became the basis for a new business model: the farmers rent out their manual labor and use the technology to plow adjacent parcels in neighboring communities

27

Findings:BolsteringIn-SituClimate Adaptation

Remittances play a vital livelihood support role in the Western Highlands and could represent an important opportunity for in situ climate adaptation. Guatemalan recipients are more likely to channel remittance capital toward daily consumption, children’s education, and improvements in household dwellings rather than investments in agricultural inputs.₁₄₁ Part of the reason is that remittances sent by migrant youth are often received by older generations who remain in place and may not be well suited to continue working in agriculture

The majority of remittance receipts in the Western Highlands are captured by households and individuals rather than at the community level However, FAO is currently developing a pilot for a community remittance matching program in which they will match every dollar remitted before eventually transferring the project to the Guatemalan government. FAO expects the project will go live in late 2025 or early 2026, yet finessing strategies to encourage households to channel remittance capital into agricultural investments remains an ongoing implementation challenge.

Monitoring and evaluation mechanisms continue undergoing changes and innovations. An integrated perspective that accounts for the interconnected relationship between climate resilience, health, education, food security, and other development priorities has the potential to maximize well-being.

The Tejutla Farmers Network, for instance, partnered with the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food (MAGA) and Ministry of Education (MINEDUC) to promote nutritious food in Guatemalan schools ₁₄₂ Through the collaboration, smallholder farmers sell monthly deliveries of fresh produce to local schools, thereby generating twin benefits of expanding farmers’ market access and fighting child malnutrition The model was eventually scaled up nationally into a 2017 federal law (School Nutrition Law) During the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the network temporarily shifted to deliver directly to households due to school closures, which resulted in nutritional benefits for families at large.

FAO and MAGA are currently implementing reform requiring the registration of smallholders in a national database to prevent their displacement by large companies that have exploited the law to sell brand-name, less nutritious products in schools. Access to healthcare and education were two areas highlighted by Indigenous women farmers in Xexuxcap as complementary to food security needs

28

Findings:BolsteringIn-SituClimate Adaptation

Consultation mechanisms strengthen the effectiveness of climate adaptation. The Catholic Church, for example, has proven a successful avenue to secure buy-in from local communities When feedback mechanisms are accessible to beneficiaries, projects can improve over time and become better targeted. Bottom-up approaches can give more power to communities but at the cost of over-ambitious or unclear objectives that sometimes result in project failure.

Structural barriers to scale-up include language gaps, lack of land ownership (especially among Indigenous women), government corruption, and underinvestment in the region’s water, transportation, and telecommunications infrastructure, among other factors. Untapped opportunities for scale-up remain given that local demand for some crops, such as tomatoes, currently exceeds local supply

Womenfaceadditional,uniqueobstacles to climate adaptation on multiple fronts. Prevailing patriarchal norms have significantly restricted land ownership among Indigenous women, resulting in a gendered land distribution gap.₁₄₃ Women’s livelihood opportunities are also limited by competing priorities: unpaid household labor and childcare detract from agricultural work. Additionally, women tend to prioritize feeding their families with the crops they grow, limiting their ability to use their production for profit.

In some Western Highlands villages, such as Xexuxcap, women lead a high share of agricultural work in the absence of men who have migrated to Mexico or the United States Women who are single or whose husbands have migrated have slightly expanded livelihood opportunities due to remittance capital and custodianship over the land of male family members

Women’s mobility is also restricted in many communities, and women producers face difficulties transporting their products to market due to gendered norms that discourage women from driving. FAO staff estimate that in most rural communities in the Western Highlands, fewer than one percent of women drive.₁₄₄

29

Producer showcases fruit preserves made by Las Orchideas women’s cooperative, village of Tzalé, San Marcos department (December 2023)

Findings:BolsteringIn-SituClimate Adaptation

Migration is a multifaceted phenomenon, and while improvements in farming techniques can bolster in situ adaptation, such enhancements will only affect the mobility of those whose migration is primarily driven by the impacts of climate change on agricultural economies. Notwithstanding such climate-adaptive interventions, individuals may still choose to migrate due to social networks, lifestyle aspirations, or other factors.

Emigration of working-age men from the Western Highlands impedes smallholders from employing labor and growing their businesses. Youth migration reduces the agricultural labor supply, prompting workers who stay behind to charge higher fees for labor producers cannot afford

Emigration and high labor costs have also reduced the Western Highlands’ corn production, and as a result, the region’s households have substituted to buying corn produced in coastal zones This shift has negatively impacted nutrition in the Western Highlands, as children prefer the local corn flavor and reject alternatives.

Additional investments in youth are urgently required. Youth aspirations are the most significant predictor of future available labor in agricultural communities and migration outflows. Primary and secondary schooling does not adequately match potential labor market opportunities, and youth face profound difficulties accessing and affording college education.₁₄₅ Students who wish to continue their education at the university level must migrate from rural areas to larger cities.

Increasingly, youth in the Western Highlands lack interest in working on their family farms or in agriculture due to personal motivations and cultural shifts. As such, off-farm income opportunities represent an increasingly critical component of job creation and intergenerational social mobility

30

Deepenandreplicatecollaborationsthat haveresultedinsuccessfulprojecttransfer andscale-upbytheGuatemalan government.

The UN’s partnership with MAGA is particularly illustrative of sustainable capacity building: FAO pilots an intervention, deploys technical assistance and training to local actors, and transfers the project to MAGA’s custody for further institutionalization Deep and trustful partnerships can help build institutional knowledge, leadership, and infrastructure to sustain a project’s gains well into the future Greater collaboration between Guatemalan ministries and a narrower but highly capable set of partners would diminish collective action problems across development operations and optimize the use of resources.

Increasetechnicalandfinancialsupport forregenerativeagriculturaltechniques fortheirrelativelylowcostandeaseof adoption.

Considering the salience of water-related challenges in Guatemala, water-smart agriculture ought to be a priority for the Guatemalan government, USAID, NGOs, and multilateral organizations Best practices include grass barriers, water harvesting, raincapturing technologies, tree shades, droughtresistant seeds, and reforestation. When possible, plots of land can be made selfsustainable through the use of livestock, manure or plant-based fertilizers, living fences, composting, and mulching techniques.

Mainstreammonitoringandevaluation approachesthataimtoaddressagricultural challengesincombinationwithother developmentpriorities.

Such mechanisms should account for various areas of need (including nutrition, health, and education) and the perspectives of Indigenous peoples, women, and youth

Combinetechnicalassistancewith Indigenousandtraditionalexpertise passeddownthroughgenerations.

Indigenous communities are experienced environmental stewards. Layering technical assistance with traditional best practices such as crop rotation, climate resilient seeds, and agroforestry techniques can yield high productivity gains.

Expandlegalaidtohelpfarmersobtain businesslicenses.

A prerequisite for micro-loans, legal assistance can also shore up farmers’ negotiating position with larger companies buying their produce.

Increasecapitalinvestmentstohelp producersscaleuptheirbusinesses.

Farmers often seek to move beyond the production of raw goods and expand into adjacent finished-product industries, such as graduating from producing tomatoes to bottled tomato sauce, or fresh fruits to jams and fruit preserves. Multiple producers raised the importance of machinery, factory space, and manual labor required for scale-up, calling for additional capital investments in their ingenuity and entrepreneurship

Increaseinformationonandaccessto financialinstrumentssuchas microcredit,savingsandlendinggroups, andcropinsurance.

International donors and NGOs should work with MAGA to expand knowledge of and access to Guatemala’s climate insurance program, which was revitalized in 2022 They should also concentrate investments in group savings and lending schemes that help increase credit access

31

RecommendationsforUSAID,NGOs, andmultilateralpartners:

RecommendationsforUSAID,NGOs, andmultilateralpartners:

Increasefocusongenderdisparitiesin landownership,literacy,transportation, andcreditaccessacrossalllivelihood supportprograms.

The vast majority of women in the Western Highlands do not drive a car or ride a motorbike, substantially impeding their ability to transport goods to markets far off in city centers. Greater attention to women’s education is also needed, as literacy disparities restrict women’s mobility and independence. Limited access to business licenses and microloans also hinders the growth potential of women-owned farms and cooperatives To overcome these barriers, special legal and financial support should be dedicated to women’s collectives that wish to expand

Developandinvestinyouthemployment andlivelihoodopportunitiesoutsideof agriculture.

Given generational shifts and receding youth interest in farming, off-farm professional and educational pathways are increasingly needed as alternatives to migration that better match youth aspirations.

Expandfarmer-to-farmerknowledge transferthroughimprovedtargeting.

Development partners can further empower farmers through tours, workshops, and other fora for producers to exchange best practices. Digital platforms, such as WhatsApp, can play an increasingly valuable role in integrating producer networks and expanding the reach of Guatemala’s rural extension system

Expandaccesstoreliableweatherand cropforecastsandensureexisting programsreachvulnerablepopulations.

For example, information generated by the USAID-NASA SERVIR program, which uses geospatial technologies to inform decisions of Central American regional and local partners, should be made accessible to all who wish to use it. A more robust use of AI that complements Indigenous knowledge could also be considered.

Replicatecommunityremittance matchingandanticipatoryaction programsthatpooldiasporafinancing forclimateadaptationandresilience.

MAGA should implement a community remittance matching program that equips smallholders to pool investments for costly agricultural inputs and technologies, which could be shared between multiple producers. FAO is currently ideating on a similar remittance project and looking for donor funding. Matching remittance transfers with government funds has proven effective in crowding in diaspora financing, but requires trustful engagement between diaspora networks, migrant sending communities, and local governments.₁₄₆ If carefully coimplemented, such programs can spread benefits of remittances that would otherwise accrue solely to households with diaspora ties, while facilitating burden sharing for climate adaptation among Guatemalan government, international, and diaspora stakeholders

Additionally, FAO should consider implementing a remittance anticipatory action program through partnerships with private companies such as Remitly, as Mercy Corps has done. Such projects can harness remittances for climate resilience by providing information and early hazard warnings to remittance senders in advance of agricultural downturns, extreme weather, or other shocks.

32

RecommendationsfortheU.S.State Department,PresidentArévalo’s administration,andGuatemalanCongress:

TheArévaloadministrationshould capitalizeonpoliticalmomentumfor comprehensivelandlawreform.

Guatemala lacks a basic land law that defines tenure categories and addresses Indigenous communities’ longstanding land grievances. The lack of a clear and integrated agrarian policy has created ambiguity ripe for misinterpretation by civil courts, thus impeding land conflict resolution and sustaining unequal land ownership. The Arévalo administration would be credibly positioned to lay foundations for land law reform, potentially through participatory consultation and popular referenda in the absence of a Congressional majority. Such a process should capitalize on the momentum of the Semilla Movement’s electoral victory, consider provisions on communal land ownership, and focus on reducing tenure insecurity among Indigenous communities and women

GuatemalanCongressshould implementanationalwaterlawthat protectstherighttoadequate sanitationanddrinkingwaterand standardizeswaterregulation.

While constitutional provisions have outlined the right to clean and safe water, legislative efforts to operationalize the right to water have failed, which has left municipalities in charge of water regulation and resulted in inequalities and inefficiencies. A national water law should be a priority in Guatemalan Congress considering the Western Highlands’ dire water-related needs.

GuatemalanCongressshouldapprove legislativereformthatwouldenhance implementationoftheSchoolNutritionLaw, withthegoalsofcombatingchild malnutritionandexpandingsmallholders’ marketaccess.