BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT

Understanding the Role of Data in Early Warning and Durable Solutions for Internally Displaced Persons

A REPORT FOR THE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION GLOBAL DATA INSTITUTE IOM

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT: UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF DATA IN EARLY WARNING AND DURABLE SOLUTIONS FOR INTERNALLY DISPLACED POPULATIONS

Report prepared for the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Global Data Institute by Master in Public Affairs students at the Princeton University School of Public and International Affairs. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of IOM.

AUTHORS

MikaylahLadue

DenisseChavarría

BrontëForsgren

GregGuggenmos

KristinaLorch

FunkeAderonmu

TNangSengPan

FACULTYADVISOR

BrianKelly

VisitingLecturer,PrincetonUniversitySchoolofPublicandInternationalAffairs(SPIA)

EDITORS

BrontëForsgren

DenisseChavarría

MikaylahLadue

TRAVELLOGISTICSLEAD

FunkeAderonmu

KristinaLorch

GRAPHICSDESIGNER

MikaylahLadue

CONTRIBUTOR

ZoëGorman

PUBLISHEDFEBRUARY2024

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

The authors are sincerely grateful to the many people who supported this policy workshop and informed the findings of this report We would like to give special thanks to Brian Kelly, our faculty advisor, for his mentorship and guidance throughout the workshop. Our thanks also go to Dean Amaney Jamal, Senior Associate Dean Paul

Lipton, Associate Dean Karen McGuinness, Finance and Operations Manager Shannon Presha, Faculty Assistant Cecylia Jablonski, and the rest of the Princeton University School of Public and International Affairs Graduate Office team for their efforts in making this workshop possible

We would like to express gratitude to the following individuals, organizations, and community leaders for their insights, perspectives, and willingness to meet with and host us over the course of this workshop

Adamawa State Emergency Management Agency and Ministry for Reconstruction, Rehabilitation, Reintegration and Humanitarian Services (RRR)

HE Bello Hamman Diram, Honorable Commissioner

American University of Nigeria (AUN)

Attahir B Yusuf, DVC, Vice President of Academic Affairs and Provost

Patrick Fay, Dean, School of Arts and Sciences

Hajia Toure, Atiku Institute

Rukkaiyatu Bashir Ribadu, Director, Centre for Women Empowerment and Youth Development, Atiku Institute

Abdisalam Umar, United Nations Development Programme

Abdoulaye Sabi’u, United Nations Development Programme

Adamu Saad, Faculty, School of Social Science

Federal University of Technology (FUTY)

Inuwa Jafaru, Deputy Vice Chancellor

Jude Momodu, Director, Centre for Peace and Security Studies

Owonikoko Babajide, Coordinator, Graduate Programmes

Georgetown University

Elizabeth Ferris, Research Professor; Director, Institute for the Study of International Migration (ISIM)

International Organization for Migration (IOM), Abuja Office

Laurent De Boeck, Chief of Mission

Paula Pace, Deputy Chief of Mission

IOM COMITAS Project, Yola

Jabula Elijah Bello, Field Operations, Displacement Tracking Mechanism (DTM)

Dessalegn Gurmessa, DESSO, DTM

Abraham Oluseye Kolade, Senior Information Assistant, DTM

Amos Njoroge Nderi, Project Manager

Esther Avindia, Mobility

IOM Coordination Staff, Abuja

Ikechukwu Attah, National Protocol Officer

Blessing Soeze, Human Resources

Assistant

Maureen Chinenye Ezeanya, Senior Program Assistant

Silas Ogheneworo Uruwarie, Logistics

Assistant

Fawziya Mohammed Bornoma, Procurement Assistant

Patricia Onome Ogeh, Admin, DTM

IOM Displacement Tracking Mechanism (DTM), Maiduguri

Denis Martin Andrew Wani, Head

IOM Global Data Institute

Muhammed Rizki, Global Coordinator, DTM

Prithvi Hirani, Humanitarian Data Programme Officer, DTM

Stuart Campo, Data Impact Officer/Consultant

Robert (Rob) Trigwell, Senior Coordination Officer, DTM

Sarah Fekih, Data Management Officer, DTM

IOM Global Headquarters, Geneva

Siobhan Simojoki, Resilience and Recovery Advisor, Transition and Recovery Division

Sam Grundy, Chief, Transition and Recovery Division

Joe Sloey, Operations Manager, Global Support Team

Nick Bishop, Disaster Risk Reduction Lead

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

Hugo Brandam, Junior Officer

Charles Sell, Internal Displacement Officer

Damien Fresnel, Emergency Preparedness Officer, Preparedness and Response Division

Damien Jusselme, Data and Impacts

Analytics Team Lead, Global Migration Data Analysis Centre

Robert Beyer, Data and Research Analyst, Migration, Environment, Climate Change and Risk Reduction (MECR)

Fatma Said, Emergency Preparedness

Kristina Uzelac, Program Coordinator, DTM

Shannon Hayes, Humanitarian Data Expert, Department of Field Support

Vicente Anzellini, Global and Regional Analysis Manager

Ivana Hajžmanová, Global Monitoring Manager, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC)

IOM Livelihoods Sector, Yola

Ahmed Asekome, Livelihoods Focal Point

IOM Head of Office, Yola

Maliki Hamidine, Head of Sub-Office

Ameh Celestin, Mental Health and Psycho-social Support

IOM Regional Data Hub West Africa

Luisa Baptista de Freitas, Regional Data and Research Unit Head

David Musombi, Project Officer, DTM

IOM Shelter and Housing, Land Property, Yola

Bittinger Mshelia, Housing, Land and Property Officer

Ezekiel Ava'abem Aguh, Shelter Technical Supervisor

IOM Washington, D.C. Office

Vincent Houver, Chief of Mission

Kathleen (Katie) Kerr, Senior Program Officer

Joseph Ashmore, Head, Emergency Preparedness and Response Coordination Support Unit

Malkohi New City (Durable Solutions)

Umaru Abubakar, Community Leader

REACH for Impact

Katie Rickard, Director of Global Programmes

United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

David Alpher, Conflict and Violence Prevention Integrator

United States Department of State Bureau of Populations, Refugees, and Migration (PRM)

Seth Perlman, Data Scientist

Catherine Steidl, Global Migration Data Advisor

United States Department of State Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO)

Gray Barrett, Foreign Affairs Officer

Srividya Dasaraju, Foreign Affairs Officer

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Yola

Elsie Bertha Mills-Tettey, Head of Field Office

Ronnie Harold Miroh, Durable Solutions Officer

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA)

Momsiri Wesley Gambo, Humanitarian Affairs Officer

Leonardo Milano, Data Science Team Lead, Centre for Humanitarian Data

World Food Programme (WFP)

Anja Palm, Early Warning Conflict Risk Analyst

World Bank (WB)

Catherine Defontaine, Senior Operations Officer, Fragility, Conflict and Violence Group

Yale University

Nathaniel Raymond, Lecturer, Jackson Institute for Global Affairs; Executive Director, Humanitarian Research Lab, School of Public Health

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT

ACRONYMS PROJECT OVERVIEW AND METHODOLOGY DEFINITIONS BACKGROUND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION TO THE SOLUTIONS PATHWAY FRAMEWORK KEY RECOMMENDATIONS C O N T E N T S DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS 17. Ethical Framework for Data Collection and Analysis 22. Ethical Considerations for Qualitative Data Collection 25. Data Disaggregation 26 Insights from the Field EARLY WARNING AND RESPONSE 30 Recommendations for the Global Data Institute 34 Intersectional Considerations for Data Collection and Analysis 45 Political Challenges for Early Warning Systems SHORT-TERM ASSISTANCE DURABLE SOLUTIONS 49. Understanding the End of Physical Displacement 53 The Pursuit of Durable Solutions 56 Criteria to Measure the Durability of Solutions 60 Intersectional Considerations for Data Collection and Analysis CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 1 2 3 5 7 10 12 14 28 47 49 63 APPENDICES 68 REFERENCES 70 BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT

A C R O N Y M S

COMITAS

CRN

DII

DMS

DSEG

DSID

DTM

EW

HHI

IASC

ICRC

IDMC IDP

IFRC IOM ISIL LGBTQI+

Conflict Assessment Report in Ten Communities in Adamawa State

Community Response Network

Demographically Identifiable Information

Disaster Management System

Data Science and Ethics Group

Data for Solutions to Internal Displacement

Displacement Tracking Matrix

Early Warning

Harvard Humanitarian Initiative

Inter-Agency Standing Committee

International Committee of the Red Cross

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

Internally Displaced Person

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies

International Organization for Migration

Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex

Non-Governmental Organization

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

Personally Identifiable Information

Periodic Global Report on the State of Solutions to Internal Displacement

Reseau Billital Maroobe

Registro Único de Victimias (Single Registry of Victims)

Self-Reliance Index

Transhumance Tracking Tool

United Nations

UNGA

UNHCR

United Nations General Assembly

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees

World Bank

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1

SRI TTT UN

NGO OCHA PII PROGRESS RBM RUV

WB

D E F I N I T I O N S

Displacement: Displacement indicates the “movement of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence,” with causes including but not limited to: armed conflict, generalized violence, human rights violations, development, and disasters caused by natural hazards or of human origin.¹

Cross-border displacement: displacement across national borders.

Internal displacement: displacement within the borders of a sovereign nation.²

Durable Solutions: Our research finds that internally displaced persons find “durable solutions” to their displacement when they no longer face needs related to their displacement and when they can exercise their rights without discrimination because of their displacement ³

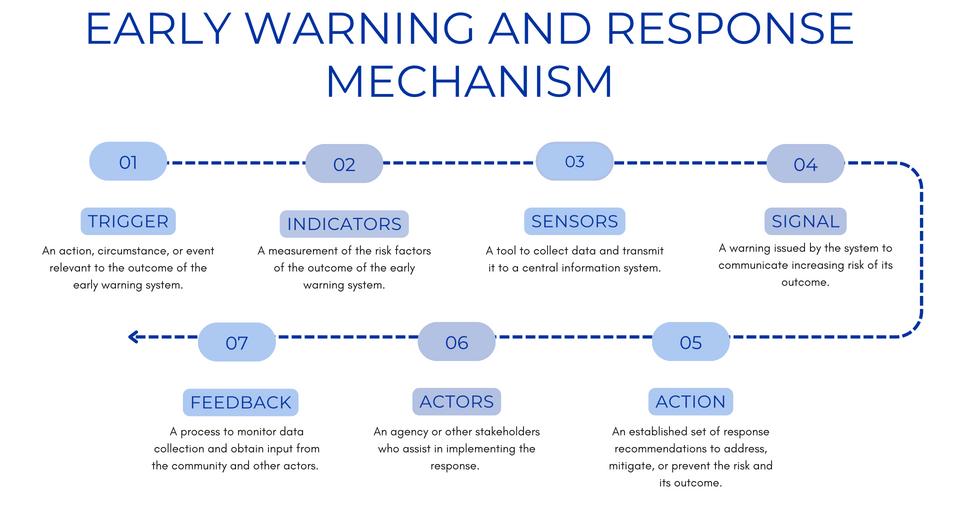

Early Warning: Early warning is a process to detect and analyze the increasing risk of conflict or crisis Early warning can lead to anticipatory action, including before a displacement event occurs ⁴

Host Community: Host communities are the communities that host internally displaced persons and refugees after a displacement event occurs

Integration: Integration is a “two-way process of mutual adaptation between migrants and the societies in which they live, whereby migrants are incorporated into the social, economic, cultural and political life of the receiving community” that “entails a set of joint responsibilities for migrants and communities, and incorporates other related notions such as social inclusion and social cohesion ” Integration does not require permanent residence ⁵

Internally Displaced Person: Persons or groups of persons forced or obliged to flee or leave their homes or places of residence due to various drivers (see Displacement) and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border but remain within their same nation.⁶

Key Informants: Key informants are essential primary sources of information. Key informants are well versed about their communities, communities’ inhabitants, the site visited, and/or the disaster, because of professional background, leadership role, or personal experience Key informants include, for example, local civil, community, government, religious, and tribal leaders ⁷

Local Integration: Local integration, in the context of internal displacement, is a process of integration into a host community where an internally displaced person has sought refuge that enables the achievement of durable solutions

Reintegration: Reintegration, in the context of displacement, is a process of integration following an individual’s return to their community of origin that enables the achievement of durable solutions

Returnee: A returnee is an individual who goes back to their original point of departure Returns can be voluntary or forced ⁸

Settlement Elsewhere: Settlement elsewhere, in the context of displacement, is a process of integration elsewhere in the country, not in the community where the internally displaced person has sought refuge, that enables the achievement of durable solutions

Transhumance: Transhumance is the action or practice of moving livestock from one grazing ground to another in a seasonal cycle, typically to lowlands in winter and highlands in summer.⁹

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 2

E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y

In 2022, over 71 million people worldwide were displaced within the borders of their own countries. The increasing global magnitude and scope of internal displacement requires direct, clear, and actionable solutions to improve the lives of those experiencing this displacement. An understanding of the best ways to prevent displacement, mitigate its harms when it occurs, and create comprehensive, durable solutions for those who have been displaced is a key aim of the global humanitarian community, including the United Nations International Organization for Migration (IOM).

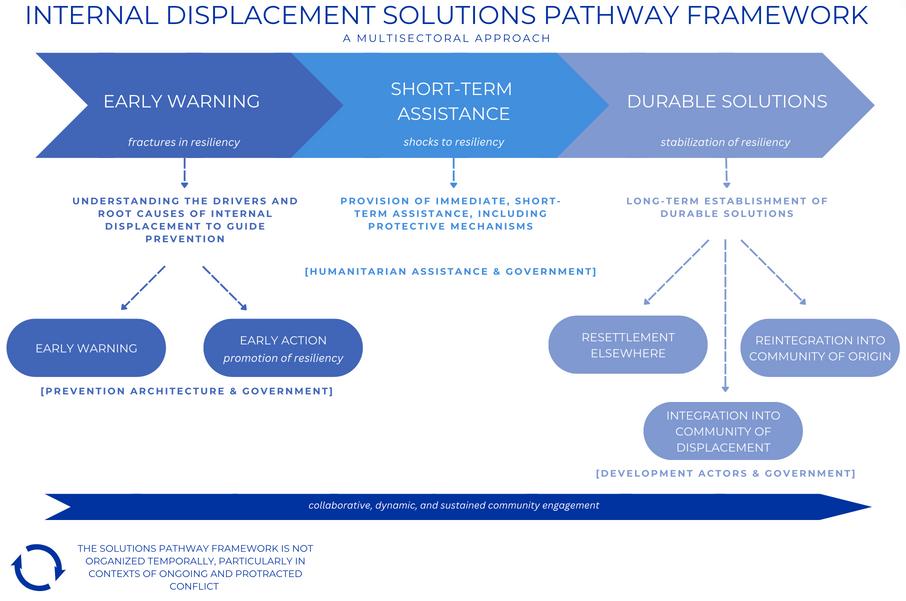

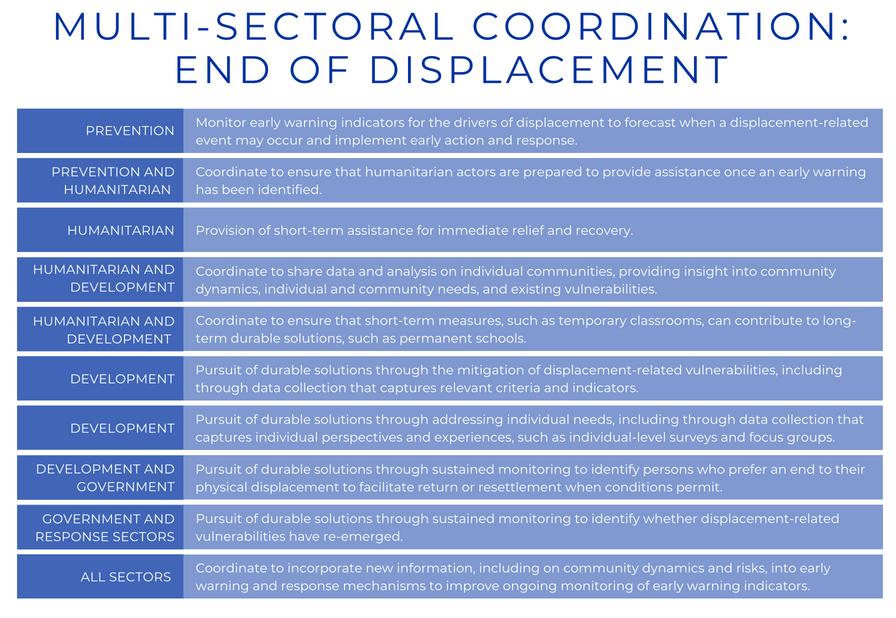

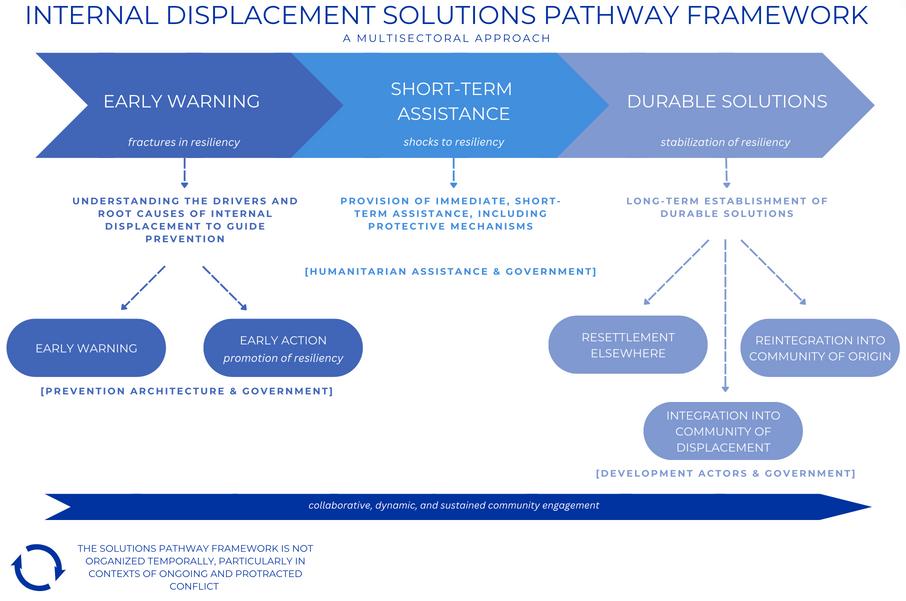

This report states that creating durable solutions to displacement is best viewed as part of an ongoing solutions pathway rather than a final status In doing so, it expands upon the concept of a solutions pathway, introduced by the Data for Solutions to Internal Displacement (DSID) Task Force and incorporated into the first iteration of the Periodic Global Report on the State of Solutions to Internal Displacement (‘PROGRESS Report’) The proposed Internal Displacement Solutions Pathway Framework (‘Solutions Pathway Framework’), anchored in a resilience framework, envisions solutions to displacement as including the continuum of prevention and response and the constantly evolving context of preparedness, risk, and recovery as they relate to mobility. The resilience framework strengthens the Solutions Pathway Framework by placing resiliency at the core of internal displacement The deterioration of resilience can inhibit a community’s response to displacement, while establishing resilience can support durable solutions Accordingly, the Solutions Pathway Framework specifically delineates three phases to the solution pathway: early warning, identifying fractures in resiliency and promoting resiliency; short-term humanitarian assistance, responding to shocks to resiliency; and durable solutions, rebuilding and stabilizing resiliencies within communities These three phases connect early warning to the overall attainment of durable solutions, including recognizing that understanding the drivers and root causes of internal displacement to guide prevention in the first place is a valuable tool to create lasting, durable solutions Importantly, the Solutions Pathway Framework mandates collaborative, dynamic, and sustained community engagement in all relevant processes, including data collection and analysis

Using the Solutions Pathway Framework as a foundation, the report expands to explore key understandings of the data sets, tools, and concepts used to analyze each phase, with a particular emphasis on early warning and durable solutions All phases rely on quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis to provide insight into evolving displacement dynamics, which raises significant ethical considerations and concerns. Many data ethics questions are context dependent, shifting based on the culture and crisis at hand, meaning there is no globally applicable framework to deconflict ethical issues that may arise This report builds upon existing ethical frameworks to delineate clear, universal recommendations for data collection and analysis, alongside specific, nuanced considerations that must be accounted for within different contexts

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 3

E X E C U T I V E S U M M A R Y

Beginning with prevention, we have collected a non-exhaustive list of early warning systems, data resources, and tools relevant to the specific drivers of internal displacement: conflict, development-induced displacement, situations of violence, violations of human rights, and disasters caused by natural hazards or of human origin. Early warning systems attuned to these drivers can provide an opportunity to predict when displacement may occur and appropriately respond to such a prediction.

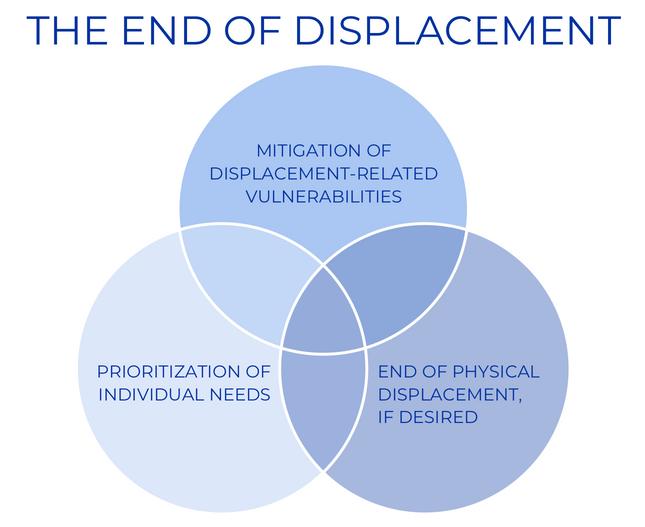

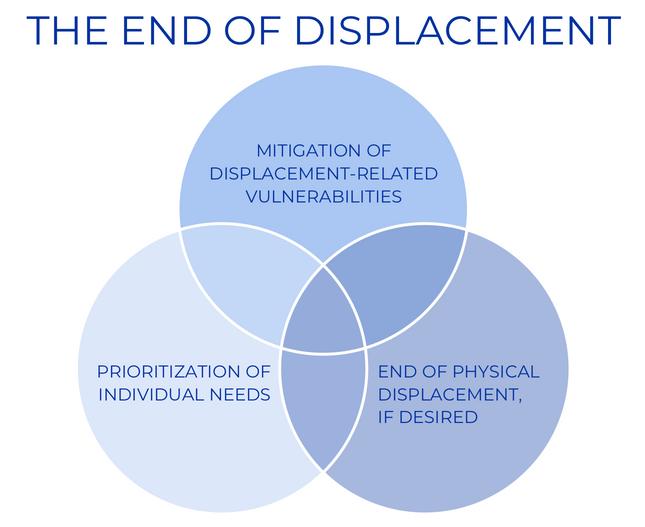

Once displacement has occurred, the focus shifts to the provision of immediate, short-term assistance, including protection mechanisms, and the establishment of long-term, durable solutions A question central to these responses is when displacement ends, but there is no consensus within current literature and practice as to when internal displacement ends In our analysis of durable solutions, we propose that the end of displacement is best viewed as the confluence of multiple factors: the end of displacement-related vulnerabilities, the prioritization of individual needs, and the end of physical displacement (defined as physically residing in a community that differs from the preferred location of residence), if desired This approach is inclusive of integration into the community of displacement, reintegration into the community of origin, and resettlement elsewhere Regarding durable solutions, the report reviews existing datasets and tools that may assist in measuring and analyzing whether durable solutions have been attained It further recommends the application of a set of criteria to assist in this determination, as well as in determining whether such solutions remain durable Importantly, this requires continued data collection and monitoring

We finalize our report with a list of conclusions and recommendations regarding approaches to data collection and analysis, early warning, and durable solutions as they relate to internal displacement. We propose that these findings may be built upon in future iterations of the PROGRESS Report.

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 4

K E Y T A K E A W A Y S

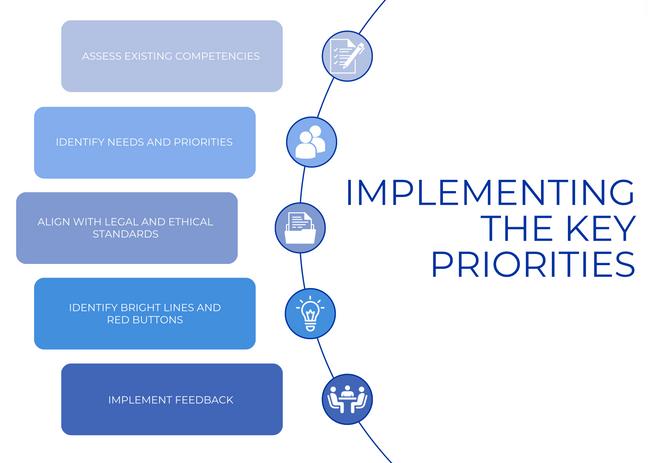

There are five key priorities for ethical data collection along the continuum of displacement, including for prevention and durable solutions:

Safeguard participants’ agency in data use and collection, Protect individual privacy, Keep data secure,

Maintain visibility and transparency of data use, and Ensure accountable partnerships

To ensure implementation of these key priorities, an organization must:

Identify its needs and priorities, Assess its existing competencies, Align with relevant legal and ethical standards, Identify when data collection should be initiated and terminated, and Implement feedback mechanisms

Ethical data collection and analysis, particularly for qualitative data, should: include informed consent; be founded upon trauma-informed approaches; apply an intersectional perspective that recognizes how different identities can increase vulnerabilities; establish clear guidelines on when collection and analysis should be terminated, including relevant safety and security protocols; and incorporate dynamic and flexible feedback mechanisms.

The decentralized structure of the humanitarian community, in addition to financial and human capital constraints, limits the feasibility of an external ethics review board to monitor whether data collection and analysis align with appropriate ethical guidelines In lieu of an ethics review board, organizations should adopt a two-pronged approach inclusive of (1) appointing an ethics advisor(s) at an organization’s headquarters, and (2) establishing a stakeholder working group at the local level that is inclusive of the internally displaced population, personnel from the humanitarian country team, and on-the-ground prevention, humanitarian, development, and government actors The IOM Global Data Institute (‘Global Data Institute’) should work alongside the ethics advisor(s) in coordination and advisory capacities.

An internal displacement solutions pathway framework that is inclusive of early warning, humanitarian assistance, and long-term durable solutions is critical to incorporate ethical approaches into solutions to internal displacement and ensure collaborative, dynamic, and sustained engagement of internally displaced populations

Resiliency should be a core component of an internal displacement solutions pathway framework. As a component of early warning, actors can identify fractures in resiliency that increase vulnerability to internal displacement, identify existing resiliency to strengthen early response to the drivers of internal displacement, and promote the development of resiliency to strengthen future response Humanitarian actors, through short-term assistance, support communities after experiencing shocks to their resiliency. Resiliency also strengthens durable solutions by bolstering an internally displaced population’s ability to adapt to and recover in their new environments

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 5

K E Y T A K E A W A Y S

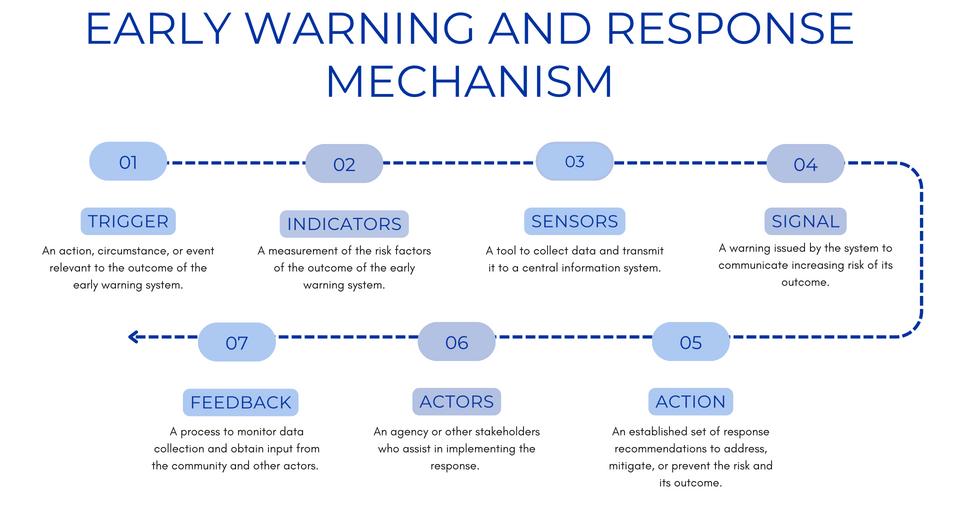

Early warning must include early action and response to effectively prevent displacement, mitigate its duration, and respond to its harms. An early warning and response mechanism will broadly consist of seven components: triggers, indicators, sensors, signals, actions, actors, and feedback mechanisms

Given the various drivers of displacement, it is logistically and technically infeasible to create a single early warning system to forecast internal displacement. The Global Data Institute should prioritize integrating IOM into existing early warning and response mechanisms to ensure the organization can respond once the warning of a driver of displacement occurs. The Global Data Institute should further coordinate to share datasets, tools, and best practices, when appropriate; consult on data collection and analysis approaches; and assist in developing new early warning and response mechanisms

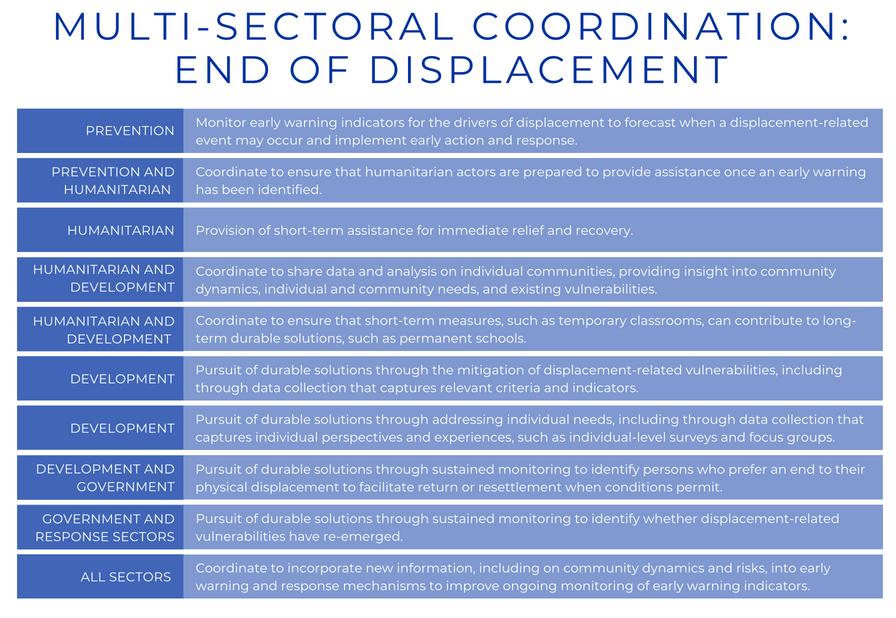

Although humanitarian and development assistance are often viewed as separate, discrete forms of aid, both forms should be used in tandem to prevent service interruption and deepen resilience in populations facing displacement. Designating internally displaced person (IDP) coordination focal points within a variety of organizations could facilitate this cooperation

When displacement ends is still unresolved but should be viewed as the confluence of several factors, rather than a single measurement or end state. These factors include:

The end of displacement-related vulnerabilities, which can include strengthening community resilience;

The prioritization of individual needs; and

The end of physical displacement, defined as physically residing in a community that differs from the preferred location of residence, if desired.

This definition indicates that an individual can no longer be displaced but still

still experience vulnerabilities

The following criteria should be applied to determine when a solution has been achieved or whether it remains durable:

Long-term safety and security

Freedom of movement.

Adequate standard of living.

Sustainable livelihoods and economic stability

Access to rights and services

Empowerment through self-sufficiency

Community integration and social cohesion

Psychosocial support and mental well-being. Participation in public affairs.

A durable solution may not truly be durable in the long term, even if it has been established by governments and aid agencies or agreed upon by IDPs and host communities, when applicable. Continued monitoring is needed to ensure that solutions are durable for all segments of the internally displaced population, that community buy-in remains, and that no new displacement-related vulnerabilities have arisen

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 6

PROJECT OVERVIEW AND METHODOLOGY

The analysis and recommendations detailed in this report responded to a set of questions from the project client, the Global Data Institute The research questions centered on the “bookends” of internal displacement, namely: early warning, when displacement might occur, and durable solutions, when displacement ends The specific research questions are noted below

PROJECT RESEARCH QUESTIONS

EARLY WARNING

What data tools/sets, IOM or non-IOM, are helpful in giving early warning about forced displacement?

What are the ethical issues and other political, social, or cultural challenges associated with collecting and analyzing this information?

What resources are required to ethically collect and analyze data about forced displacement?

DURABLE SOLUTIONS

Can displacement end before an individual’s preferred durable solution is achieved?

What data tools/sets, IOM or non-IOM, are helpful in analyzing this?

What are the ethical issues and other political, social, or cultural challenges associated with collecting and analyzing this information?

What resources are required to ethically collect and analyze data about the ending of displacement?

To address the client’s questions, our team conducted research between September 2023 and January 2024, and deployed multiple research methods, including desk research, field research, and interviews.

Desk Research: Prior to stakeholder interviews, the project team conducted background research on a wide variety of relevant topics, including background on early warning, useful early warning tools, data collection, durable solutions to internal displacement, and ethical issues surrounding displacement. The team reviewed existing datasets and tools used to inform understanding of early warning systems and indicators to measure durable solutions, as well as the ethical considerations in collecting and analyzing data from vulnerable populations experiencing conflict and humanitarian crises. The aim of this research was to understand the context and breadth of early warning systems and durable solutions tools used within humanitarian and migration contexts.

As a component of the desk research, the project team considered several country situations to delve deeper into how displacement, ethics, and durable solutions exist in practice. The report features three detailed case studies on Colombia, Iraq, and Nigeria, and has relied upon rich insights and experiences from other country contexts.

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 7

Field Research: During a trip to Nigeria in October 2023, members of the project team visited the Malkohi Durable Solutions site for displaced persons in Yola, Adamawa State, established by the United Nations Office of the High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) With support from IOM staff, we interviewed a local community leader to learn more about the community’s perspective on their displacement and durable solutions This field research informed and enriched the Nigeria case studies and our overall understanding of displacement from the perspective of the displaced Nigeria is further a priority country under the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General’s Action Agenda on Internal Displacement, discussed below, and experiences several drivers of internal displacement

Interviews: The project team conducted a series of in-person interviews with stakeholders to gather insights from IOM headquarters and country offices. Interviews were conducted in Yola, and Abuja, Nigeria; Geneva, Switzerland; and Washington, D.C., United States. Additionally, the project team held several virtual and inperson interviews while at Princeton University.

In addition to IOM staff, we interviewed a wide variety of stakeholders and subject matter experts, including government officials in Nigeria and the United States, academic researchers in Nigeria and the United States, community leaders, and stakeholders from the UNHCR and World Bank (WB), among others. A full list of organizations and individuals who were interviewed or who presented to the group is detailed in the Acknowledgements section of this report. Interview questions were loosely structured by the guiding research questions to enable identification of overarching themes. Team members adapted their questions to the relevant stakeholders. The interview questions centered on:

Design and implementation of early warning systems

Indicators to measure durable solutions or the end of displacement

Data sets and information sources to inform early warning analysis and measures of durable solutions

Ethical, social, and other non-technical considerations with collecting and using data to inform early warning systems and durable solutions

The report findings and recommendations further build on several frameworks for understanding and measuring progress on preventing and ending displacement. These frameworks include:

Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement: The 1998 presentation of the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement (‘Guiding Principles’) to the UN Commission on Human Rights established the foundational framework for protecting and recognizing the rights of IDPs. In all, the thirty delineated principles detail recommended protections across all stages of displacement, including preventing displacement, protection while in displacement, guidelines for humanitarian assistance, and protections while pursuing a durable solution of return, integration, or resettlement. The principles also restate that national governments are primarily responsible for ensuring access to rights and resources for IDPs within their borders, although assistance from the international community is also affirmed. Although the Guiding Principles are not legally binding, they are officially recognized as an authoritative framework on internal displacement by the UN General Assembly (UNGA).¹⁰

United Nations Secretary-General’s Action Agenda on Internal Displacement: As a follow-up to the Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Internal Displacement, the Action Agenda on Internal Displacement (‘Action Agenda’) lays out the Secretary-General’s vision for ending displacement to mobilize governments and the international community to make commitments toward advancing durable solutions.¹¹ solutions.¹¹

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 8

solutions ¹¹ The Action Agenda builds on existing UN agency frameworks and includes the following overarching goals:

The Action Agenda builds on existing UN agency frameworks and includes the following overarching goals:

Helping IDPs find durable solutions to displacement, Preventing new displacement crises from emerging, and Providing effective protection and assistance to IDPs

Inter-Agency Standing Committee Framework on Durable Solutions: The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Framework on Durable Solutions (‘IASC Framework’) aims to define and clarify the concept of durable solutions stemming from a rights-based approach ensuring IDPs:

Can voluntarily make informed choices on their preferred durable solution,

Can participate in the planning and management of durable solutions, Have access to humanitarian and development actors, and Are involved in peacebuilding processes in cases where their displacement was driven by conflict or violence.

In line with this approach, the IASC Framework details eight criteria to determine the extent to which durable solutions to displacement have been achieved for a population of IDPs These criteria involve:

In line with this approach, the IASC Framework details eight criteria to determine the extent to which durable solutions to displacement have been achieved for a population of IDPs. These criteria involve:

Long-term safety, security, and freedom of movement

Access to employment and livelihoods

Access to effective mechanisms to restore housing, land and property

Access to personal and other documentation without discrimination

Family reunification

Participation in public affairs

Access to effective remedies for displacement-related violations

These criteria are all underpinned by the principle of non-discrimination, including discrimination on the basis of displacement or any other grounds They also serve as benchmarks for measuring progress made toward achieving durable solutions ¹²

These criteria are all underpinned by the principle of non-discrimination, including discrimination on the basis of their displacement or any other grounds. They also serve as benchmarks for measuring progress made toward achieving durable solutions.¹²

Periodic Global Report on the State of Solutions to Internal Displacement: The Periodic Global Report on the State of Solutions to Internal Displacement (‘PROGRESS Report’), released by Institute for the Study of International Migration at Georgetown University and the Global Data Institute, furthers the Action Agenda and IASC Framework by asserting that obtaining durable solutions to displacement is a process or pathway rather than a final state. According to the report, data can be leveraged to assess the progress of humanitarian actors and IDPs themselves in moving along the pathway from displacement to durable solutions. The PROGRESS report offers an approach to understanding how and when durable solutions can be achieved, with an emphasis on self-reliance that involves economic well-being, adequate housing, and social inclusion as requisites for IDPs to embark on the durable solutions pathway.¹³ The PROGRESS Report is the first iteration in a series of reports intended to “contribute to a people-centered, data-driven foundation for IOM’s work.”

These frameworks, alongside the desk research, field research, and interviews, have informed the development of the report and its content.¹⁴

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 9

BACKGROUND

As of 2022, there are an estimated 71 1 million IDPs across the world Although internal displacement occurs globally, nearly 75% of all IDPs live within ten countries: Syria, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ukraine, Colombia, Ethiopia, Yemen, Nigeria, Somalia, and Sudan ¹⁵

With the increase in displacement globally, there is a growing concern to ensure coordinated efforts to end displacement Ending displacement, however, has been a topic of global concern for decades At the 78th session of UNGA, Secretary-General António Guterres noted that “the plight of internally displaced persons is more than a humanitarian issue It takes an integrated approach combining development, peacebuilding, human rights, climate action, and disaster risk reduction efforts ”¹⁶

Given the continually growing crisis of displacement, it is imperative that solutions to ending displacement take an integrated approach among prevention, humanitarian, development, and government actors to ensure that these solutions are durable

DRIVERS OF DISPLACEMENT

Conflict and violence represent one of the most prominent drivers of displacement worldwide In fact, as of December 2022, conflict and violence left 62 5 million people living in displacement across 65 countries and territories ¹⁷ Armed conflicts, civil unrest, ethnic tensions, and persecution compel millions to flee their homelands in search of safety and security The looming threat of violence serves as a catalyst for such involuntary migration

Natural hazards are additionally culpable, accounting for 8 7 million people internally displaced in 88 countries and territories as of 2022 ¹⁸ Events like floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, and wildfires cause destruction to habitations, rendering communities uninhabitable The aftermath of these catastrophes often leaves people with no choice but to seek refuge elsewhere until their homes can be rebuilt, a process that might span years

Environmental changes, exacerbated by climate change, contribute significantly to displacement Rising sea levels, droughts, deforestation, and soil degradation render certain areas inhospitable, compelling communities to relocate to more sustainable environments compelling communities to relocate to more sustainable environments

Moreover, development-induced displacement, a consequence of infrastructure projects or economic development initiatives, significantly impacts populations. An estimated 15 million people per year worldwide are forced from their homes to make way for infrastructure construction.¹⁹ These large-scale construction projects, urbanization, and industrialization often displace people from their homes without adequate compensation or resettlement plans.

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 0

Political instability and violations of human rights further propel individuals to abandon their residences Oppressive regimes, persecution based on ethnicity or beliefs, and the denial of fundamental freedoms push people to flee, seeking sanctuary in places that may offer some semblance of safety

Socioeconomic factors also play a pivotal role Poverty, economic hardships, and the lack of viable livelihood opportunities coerce many to undertake arduous journeys in search of better prospects In pursuit of improved living conditions, individuals migrate within or across borders, often facing impossible challenges along the way

TYPE AND LENGTH OF DISPLACEMENT

Displacement differs in type and length Displacement can take the form of internal or external displacement Internal displacement, which this report focuses on, is when people have been forced or obliged to move to another area in their country External displacement or cross-border displacement occurs when people have to leave their country of origin Displacement varies greatly in duration, influenced by the underlying drivers of displacement and the efficacy of interventions to address them Some displacements are temporary, and individuals are displaced for short periods (usually for a few weeks to a few months only) until conditions in their native regions stabilize, allowing them to return home

Conversely, protracted displacement persists for extended periods, often spanning years, decades, or generations Prolonged drivers of displacement can trap individuals in a state of uncertainty, forcing them to reside in temporary camps or settlements, struggling to regain a sense of normalcy In the most severe cases, displacement can be permanent Some of the causes of displacement, such as conflicts and disasters caused by natural hazards, may render return impossible, resulting in the permanent relocation of affected populations to new areas

These differences in the length of displacement depend greatly on the nature and intensity of the triggering events For instance, conflict often results in prolonged and widespread displacement, leading to longer durations, while disasters caused by natural hazards such as earthquakes, floods, or hurricanes might lead to temporary displacement, varying in length based on the scale and intensity of the calamity

Governmental policies, humanitarian aid, and the efficacy of response mechanisms also contribute to disparities in the length of internal displacement Efficient government intervention, well-coordinated humanitarian assistance, and timely provision of aid can help shorten the duration of displacement by facilitating a swift return, resettlement, or integration of affected populations On the other hand, having bureaucratic hurdles, inadequate aid, or political instability may prolong displacement, exacerbating the length and severity of the crisis

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 1

INTRODUCTION TO THE SOLUTIONS PATHWAY FRAMEWORK

Our report contributes to the foundation laid by the PROGRESS Report, which builds off the work of the DSID Task Force. The DSID introduced the concept of a solutions pathway, which “begins when an IDP is no longer in displacement, either due to moving to a location of solution (return or resettlement locations), or has decided to locally integrate in the area of displacement (local integration, however, has not yet overcome their displacement-related vulnerabilities.”²⁰

We believe that the solutions pathway established in the PROGRESS report provides a powerful mechanism for analyzing strategic decisions around the collection, analysis, and deployment of data-driven insights. Our aim is to enhance the ethical deployment of data in each stage to drive improved outcomes, and ultimately more quickly and fairly allow displaced people to move through the solutions pathway to durable solutions. Moreover, we believe that the first principle for any data strategy should be helping governments “shift from reactive assistance over long periods to beginning solutions pathways early in the displacement experience.”²¹

This report expands the proposed solutions pathway in two ways: by adding the use of early warning systems to prevent displacement before it begins and by clearly delineating three phases along the solutions pathway, each containing unique challenges and ethical considerations

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 2

Our Internal Displacement Solutions Pathway Framework (‘Solutions Pathway Framework’), which expands on the concept of the solutions pathway presented by the DSID, envisions solutions to internal displacement as encompassing measures ranging from early warning to the implementation of durable solutions

To account for situations of ongoing and protracted conflict and crisis, the Solutions Pathway Framework is not organized temporally This is illustrated by anchoring the solutions pathway within the resilience framework, which captures evolving dynamics of preparedness, risk, and recovery The resiliency framework also helps manage tensions between short- and long-term imperatives and between humanitarian and development programming, aligning with the Action Agenda

There are three primary components of the Solutions Pathway Framework:

1.

Early warning. Early warning requires understanding the root causes and drivers of internal displacement to guide prevention efforts. Early warning involves identifying the fractures in resiliency that may be present in a community, in part so that action can be taken to promote stronger resiliencies.

2.

Short-term assistance. Short-term assistance, including protective mechanisms, typically takes the form of humanitarian assistance. This assistance is delivered in moments where conflict, crisis, and disasters create shocks to resiliency.

3.

Durable solutions. Durable solutions require building stabilizing, long-term resiliencies within communities. They include, among other priorities, the end of physical displacement.

The Solutions Pathway Framework also notes the various stakeholders typically involved in internal displacement, including prevention, humanitarian, and development actors. Beyond these stakeholders, it also includes government actors to highlight government obligations, encourage government ownership, and ensure interagency collaboration. A collaborative approach is needed between all stakeholders along each phase of the pathway. This approach will look different in different communities, particularly due to variations in state capacity or government complicity in internal displacement.

Most importantly, this Solutions Pathway Framework states that all aspects of the solutions pathway require collaborative, dynamic, and community engagement. A solutions pathway is not sufficiently meaningful or inclusive if it does not integrate the voices of affected communities.

This expanded Solutions Pathway Framework provides important advantages:

Connects the decisions and challenges of engaging with early warning systems to the ultimate goal of achieving durable solutions

Allows for a more nuanced examination of data ethics, available tools, challenges, and opportunities at each phase of the solutions pathway

Forces a critical examination of the dichotomy between short-term, reactive humanitarian aid and longterm development programs We hope this framework will help actors in both spheres, alongside prevention and government stakeholders, to better collaborate and synthesize their efforts

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 3

DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

This section considers sources of data collection for early warning and durable solutions, provides an ethical framework for data collection and analysis, and addresses challenges to data collection and analysis that have been identified in the field. The core contribution of this section is the ethical framework, providing an outline of five key priorities for data collection, including safeguarding the agency of data, protecting privacy, keeping data secure, maintaining visibility, and ensuring accountable partnerships, alongside a comprehensive ethical framework for qualitative data collection specifically.

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS STATISTICS

The International Recommendations on Internally Displaced Persons Statistics (‘International Recommendations’) includes an internal displacement statistical framework, guidelines on coordination of statistics, data sources for collecting and selecting statistics, guidelines on data integration, and criteria for measuring durable solutions ²² It is inclusive of the three classifications or subgroups of IDPs: those in areas of displacement, or local integration; those in areas of return, or reintegration; and those settled elsewhere, or integration in settlement locations

PRIMARY AND SECONDARY DATA COLLECTION

Primary and secondary data collection play critical roles in informing early warning and durable solutions

Primary sources are those that provide direct access to a given subject of research, including individuals and communities that are or may become internally displaced, while secondary sources are those that provide secondhand access to or independently assessed analysis

The advantages of primary data collection include learning community-level information, including social, cultural, and political dynamics; independently confirming or rebutting secondary data sources; and promoting individual- and community-level involvement in data on internally displaced persons, which is an essential component of addressing and resolving their displacement ²³

Primary data collection may be infeasible due to logistical, resource, safety, or time constraints Interviews revealed that the following sources of primary data are seen as providing some of the most actionable insight for early warning and durable solutions:

Individual- and household-level interviews or surveys

Key informant interviews

Focus group discussions

Risk assessments and mapping

Multi-sectoral needs assessments

Intentions surveys

Biometric registration

Telephone polls

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 4

Interviews, focus group discussions, and additional forms of community engagement are important to obtain a clear understanding of individual- and community-level needs and vulnerabilities preceding, during, and after a displacement event occurs Interviews and surveys on the individual level, rather than the household level, can provide critical insight into differential experiences based on personal characteristics Risk assessments and mapping can identify potential hazards, risks, vulnerabilities, and resiliencies within a community to inform programming and response Where in-person data collection is not feasible, telephone and cell phone polls can be implemented This approach may be limited in areas without connectivity or in circumstances where funding is not available to provide phones to people who do not own them.

Multi-sectoral needs assessments aim to understand the multi-sectoral priority needs of populations, including of displacement-affected populations, to inform humanitarian assistance and response and provide insight into progress towards durable solutions These assessments are based on household-level surveys and can complement other assessments, including those informed by key informant interviews Intentions surveys identify the intentions of a population to monitor population dynamics and migration patterns. These include intentions to return or relocate elsewhere, and the reasons for these intentions

These forms of data collection are not always objective. Key informant interviews with local community leaders, for example, may not be representative of the needs and perspectives of individuals and households. Similarly, a head of household may not hold the same priority needs as members of the household This requires caution in data analysis to ensure that a range of perspectives are represented, and so that the entirety of community dynamics can be understood. In cases where community leaders or outspoken individuals are present, the views of other respondents and their individual needs and priorities may be drowned out Additionally, individuals may not be comfortable sharing views that are unpopular or may expose informants as members of minority or marginalized groups. To address these challenges, these forms of data collection should be complemented by other data collection methods discussed herein and enumerators should endeavor to be inclusive in their collection approaches.

Biometric registration allows different agencies to accurately track who is receiving services, identify movement patterns, and distribute aid In particular, biometric data is deployed to ensure accountability and prevent unethical leadership from diverting humanitarian support away from those in highest need.²⁴ Although biometric data is increasingly widespread, it can also raise significant data privacy concerns and itself incite conflict Additionally, while some individuals may have conflicting personally identifiable information (PII) in different humanitarian registries, biometric data, such as fingerprints or photo documentation, cannot be as easily changed across organizations It may be difficult to establish biometric registration in some contexts, such as in Somalia, where three separate governments are present

Secondary sources should receive independent verification and comparison with primary data, when available This is particularly important if the source of information, such as a government or organization, has motivation to report inaccurate information. Interviews revealed that the following sources of secondary data are seen as providing some of the most actionable insight for early warning and durable solutions:

Geolocation and mobility analysis

Social media platform analysis

Reporting from alternate sources

Migrant stocks and flow monitoring

Remote sensing analysis

Artificial intelligence and big data

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 5

Social media organizations and third party data collectors, who do not have a direct relationship to the owner of the data or information, can be valuable sources of data These organizations play an increasing role in data collection through population location and movement monitoring, third party polling on behalf of private actors, and phone surveys For example, Data for Good at Meta includes datasets and tools with de-identified information ²⁵ Meta has also supported monitoring population movements in Ukraine in the wake of Russia’s invasion ²⁶

These organizations may also contribute to tracking and analyzing information provided on social media platforms, which can contribute to monitoring and analyzing community-level dynamics, including allegations of human rights violations or increasing propaganda. There are thus valuable near- and long-term opportunities for UN agencies to collaborate with these data collectors. As will be discussed, however, many of these data collectors may not have developed stringent approaches to data ethics. Agreements for data use with these organizations must be rigorous, as evidence shows that ambiguous language and exploitation of exceptions can be used by third parties to expand their access to and use of PII for other purposes.²⁷

Data collection and analysis should be inclusive of reporting from alternate sources, such as news outlets, social media platforms, and police reports. This reporting should be analyzed with caution as it may lack objectivity or be an intentional source of misinformation. In other circumstances, such as with police reporting, it is important to recognize the issue of under-reporting as well as the influence of bias on part of the person authoring the intake report.

Migrant stock and flow monitoring can also inform early warning and durable solutions. Note that this monitoring may be inclusive of primary and secondary sources, as national statistics offices may collect this information. Migrant stock references the total number of migrants in a given location at a specific point in time, while migrant flow references the number of migrants arriving in or departing from a location over a particular period in time.²⁸ Surveys, population registers, and other administrative sources may provide this data.²⁹

Remote sensing analysis is an additional source of information that has been employed, including as a source of early warning and understanding of informing early warning and understanding displaced populations. For example, local government officials in Nigeria stated that the use of satellite imagery to see when governments or local farmers have built over legally established cattle migration routes should be significantly expanded. This imagery could serve as an early warning tool to detect areas where conflict between herders and farmers is likely.³⁰ The Harvard Humanitarian Initiative Signal Program on Security and Technology has developed extensive practical guidance on remote sensing evidence and satellite imagery analysis, including for displaced populations and situations of conflict and crisis, both of which can be applied to early warning or durable solutions.³¹ The Satellite Imagery Interpretation Guide for Displaced Population Camps provides critical insight into deploying satellite imagery in these contexts and the relevant ethical, social, and cultural concerns.³² It addresses, for example, practical and operational considerations, limitations, and critical questions of analysis. Ethical concerns with remote sensing analysis, however, include the co-optation of this information by malign actors who can leverage mobility information to initiate, further, or target violence.

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 6

Artificial intelligence and big data are additional digital technologies that may contribute to data collection and analysis, including in place of enumerators However, implementation of artificial intelligence and big data faces operational barriers, including connectivity and technological capacity challenges, as well as significant protection concerns These technologies may contribute to anticipatory action by rapidly analyzing data, to response by mapping affected communities, and to recovery by facilitating data collection Yet these benefits have to be weighed against considerable protection concerns, including data quality, algorithmic bias, and data privacy ³³ Given the increasing use of artificial intelligence, it is critical that organizations develop standards on using and analyzing this data

ETHICAL FRAMEWORK FOR DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS

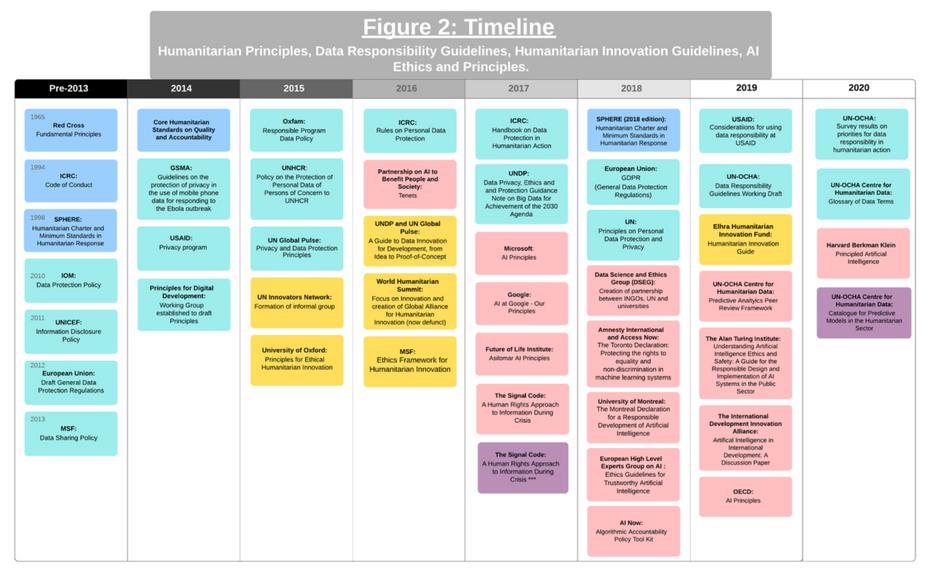

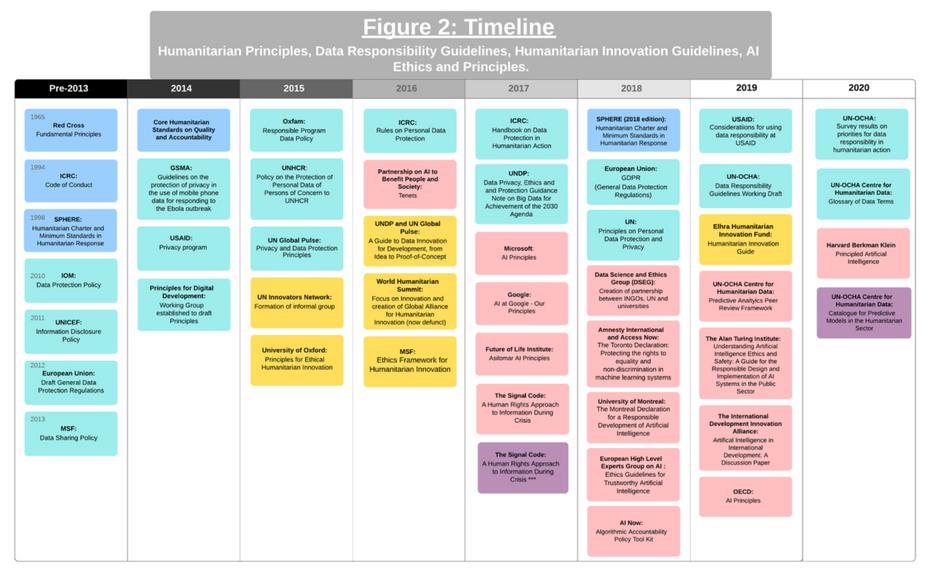

Despite the desire for clear, universally applicable answers, many answers to data ethics questions are context dependent and vary based on an in-depth understanding of the unique environment, challenges, opportunities, and limitations of a specific crisis in a particular location. We draw on a rich array of existing ethical frameworks and resources which highlight valuable ethical frameworks and detail diverse use cases and case studies. Several of these reports are highlighted below. Beyond this curated list, we underscore key priorities essential for data collection and analysis. See Appendix A for a full list of ethics frameworks and guidelines collated by the IOM Data Science and Ethics Groups.

We relied heavily on the following four reports to guide our understanding of the ethical issues associated with collecting and analyzing data on early warning and durable solutions. These reports focus on the humanitarian sector given the mandate of IOM, but insights from prevention and development actors have been incorporated into the final ethical framework.

The Framework for the Ethical Use of Advanced Data Science Methods in the Humanitarian Sector: Recently published by the IOM Data Science and Ethics Group, the framework serves as a guide for the ethical application of data science methods in humanitarian work. Developed by the Humanitarian Data Science and Ethics Group (DSEG), a multi-stakeholder group established in 2018, the framework emerged as the culmination of consultative processes and discussions. It offers a set of ethical and practical guidelines tailored for a diverse audience within the humanitarian sector, ranging from on-the-ground data collectors and enumerators to data scientists, project focal points, program managers, donors, and private and civil sector actors.³⁴

Handbook on Data Protection: The Handbook on Data Protection, a collaboration between the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the Brussels Privacy Hub, emphasizes the fundamental importance of personal data protection for humanitarian organizations. Recognizing that successfully safeguarding individuals' personal data is integral to preserving their life, integrity, and dignity, it provides practical insights on how data protection principles should be applied within the complex landscape of humanitarian action. It builds upon existing guidelines, working procedures, and practices established in challenging environments, with a focus on the most vulnerable victims of armed conflicts, violence, disasters caused by natural hazards or of human origin, pandemics, and other humanitarian emergencies. The handbook provides specific guidance on interpreting data protection principles in the context of humanitarian action, especially when utilizing new technologies, and underscores that data protection legislation enables the responsible collection and sharing of personal data within a framework that respects individuals' right to privacy.³⁵

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 7

Data Responsibility Guidelines: The United Nations Office of the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Centre for Humanitarian Data published the Data Responsibility Guidelines emphasizing the safe, ethical, and effective management of personal and non-personal data for operational response in humanitarian action These guidelines, designed for OCHA staff involved in data management across core functions such as coordination, advocacy, policy, humanitarian financing, and information management, comprise principles, processes, and tools to support responsible data practices within their work See Appendix B for a visualization of the entire data life cycle derived from this report, which is useful for organizing and implementing data projects

These guidelines are informed by the Centre’s extensive gap analysis studies, research, and field testing conducted by OCHA over several years, including the piloting of a working draft in ten different response contexts in 2019 and 2020 Finalized and endorsed in 2021, they reflect sound global guidance and policy instructions from within the UN Secretariat and across the broader humanitarian system ³⁶

Signal Code: Ethical Obligations for Humanitarian Information Activities: Published by the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative (HHI) as a pioneering effort to fill the existing gap in ethical guidance for humanitarian practitioners, Signal Code provides a robust ethical foundation to navigate the complexities of contemporary humanitarian work. The report translates and applies foundational ethical principles to the realm of humanitarian information activities, covering areas such as mobile devices, WiFi provision, data collection, storage and analysis, and biometric registration tools. The document integrates international humanitarian and human rights law and standards, ensuring that individuals affected by crises have fundamental rights regarding access, provision, and treatment of information.³⁷

Building Data Responsibility into Humanitarian Action: OCHA, alongside HHI, published this report regarding the responsible use of data in humanitarian response to protect vulnerable populations from harm. It identifies a four-step process to achieve data responsibility: evaluating the context and purpose within which data is being generated and shared, taking inventory of the data and how it is stored, preidentifying risks and harms associated with a proposed use of data before data is collected, and developing strategies to mitigate those risks. To implement this process, four minimum humanitarian standards are adopted, including identifying the need for data, assessing core competencies, managing risk to vulnerable populations, and adhering to legal and ethical standards. Lastly, it notes that a humanitarian organization who uses data responsibility will adhere to the following characteristics: incorporating responsibility as an iterative process, developing rules for the deployment and cessation of data collection, ensuring transparency, and implementing feedback loops with key stakeholders at all project stages.³⁸

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 8

KEY PRIORITIES FOR DATA COLLECTION

Five key priorities have been identified for the ethical pursuit of data collection

I Safeguard participant’s agency

Every person holds the right to control the collection, utilization, and disclosure of their PPI and aggregate data, encompassing personally identifiable details such as demographically identifiable information (DII) Furthermore, populations maintain the right to be adequately informed about information activities throughout all stages of information acquisition and use Access to information in times of crisis, along with the means to convey it, is a fundamental humanitarian necessity Every individual and community possesses an inherent right to generate, access, obtain, transmit, and derive benefit from information during crises This right to information endures through every phase of a crisis, unaffected by geographic location, political, cultural, or operational context, or severity Additionally, organizations should guarantee data subjects' rights to be informed about the use of their personal data and to access, correct, delete, or object to its processing ³⁹

II. Protect privacy.

Meticulous use of anonymization or aggregation methods is essential to minimize re-identification risks. Personal data retention should be limited to a defined period necessary for the original collection purposes. Subsequently, an evaluation should determine whether deletion or prolonged retention is warranted in order to maintain necessary quality and utility for credible results. Comprehensive coverage of potential data analysis operations must be outlined in the relevant retention policy or information notice. If data processing is planned during collection, this should be disclosed in the initial information and consent notice, with the retention period aligned with the time required for the analysis.⁴⁰

III Keep data secure

Humanitarian organizations are responsible for adhering to applicable national and regional data protection laws or to their own data protection policies When crafting data management systems, humanitarian organizations should, by default, explicitly align with the principles of privacy and data protection In developing open data frameworks, considerations for personal data protection must be integrated. Systems focused on data security should be implemented at every stage, including but not limited to encryption and deidentification of data.⁴¹

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 1 9

IV Maintain visibility and transparency

In humanitarian response, data management should prioritize transparency, particularly with affected populations This entails providing clear information about data management activities and their outcomes Additionally, sharing data should be approached in a manner that fosters genuine comprehension of the activity's purpose, intended use, sharing mechanisms, and associated limitations and risks ⁴²

V Ensure accountable partnerships

Effective coordination between humanitarian and development actors will require information-sharing agreements, which should be based on standardized legal arrangements for sensitive data sharing and include technical and ethical standards for data handling, management, and information systems No information should be shared without explicit agreement and the inclusion of accountability measures

Despite the need for collaboration, organizations must remain vigilant to potential risks, particularly in contexts of violence or conflict If involved parties gain access to sensitive data findings, the data could be exploited to locate and harm individuals, families, or groups This risk compromises the safety of people in need and the neutrality of the aid organizations ⁴³

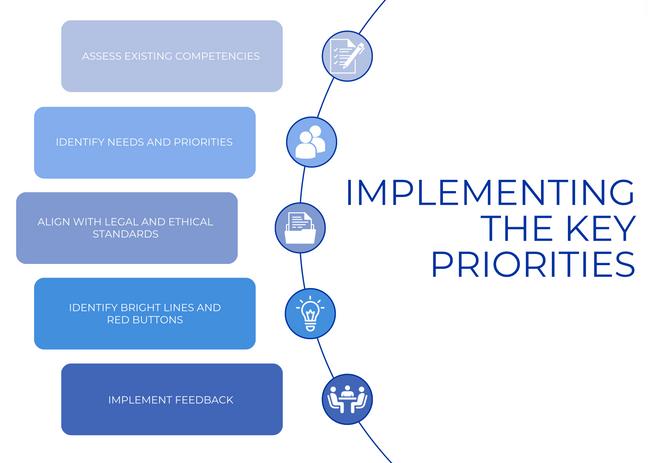

IMPLEMENTING THE KEY PRIORITIES

Implementing these identified priorities requires an intentional, coordinated, and iterative process In academia, all processes for data collection on human subjects are guided by an external ethics review board While several interviewees indicated that a similar ethics review board would help in guiding accountability for ethical data collection and analysis, we believe instituting an external ethics review board in humanitarian agencies would not be a feasible organizational strategy given several constraints. This includes human and financial capital resource constraints, which may mean that individuals with other primary roles and responsibilities are tasked with ethics review This increases the likelihood of slow decision making and a façade of accountability without the requisite expertise to ensure responsible and ethical data collection and analysis

Instead, we argue that humanitarian organizations should consider a two-pronged approach that creates (1) an advisory role(s) at the organization’s headquarters or within the Global Data Institute and (2) a stakeholder working group at the local level The advisory role(s) should be staffed by those with expertise in ethical approaches to data collection and analysis who can review existing guidelines and approaches, provide relevant recommendations, and manage an ongoing assessment of data collection and analysis This would ensure that there is an appropriate mechanism in place to determine whether the organization is aligning with ethical priorities and obligations To assist with this advisory capacity and ensure that it can function effectively in local and country contexts, a stakeholder working group should be developed that includes the internally displaced population; personnel from the country team; and on-the-ground humanitarian, development, prevention, and government actors The working group should be representative of the diversity of the internally displaced population, and the resident or humanitarian coordinator in the country should be aware of the stakeholder working group to ensure accountability and encourage coordination, collaboration, and implementation The Global Data Institute should work alongside the ethics advisor(s) in coordination and advisory capacities

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 2 0

To implement the key priorities for the ethical pursuit of data collection and analysis, an organization thus needs to: identify its needs and priorities, assess existing competencies, align with legal and ethical standards, identify when data collection should be initiated and terminated, and implement feedback mechanisms ⁴⁴

Prior to data collection and analysis, it is critical to assess the existing competencies of an organization to uphold the priorities of safeguarding agency of data, protecting privacy, keeping data secure, maintaining visibility, and ensuring accountable partnerships. If an organization does not have the capacity to uphold these priorities, then it should not begin data collection. This will require an assessment in the design phase and will need to be attuned to the local context to account for different government stakeholders and infrastructure.

Once competency has been established, an organization needs to clearly identify its needs and priorities in a given context. Only the minimum data necessary to accomplish intended organizational actions and goals should be gathered to limit the potential for collecting and subsequently analyzing data that could harm a given population. This may require a risk assessment or profile to understand the data risks associated with a given context and with the driver of displacement. Risk will differ based on whether the driver is a hazard or conflict, for example. Any identified risks should have a correlated risk mitigation plan.

Data collection and analysis will also need to align with existing legal and ethical standards. No global doctrine for data responsibility exists, so it is important for humanitarian actors to understand the local and national regulations that may constrain or support the data collection and analysis process

These delineated needs and priorities, identified competencies and risks, and guiding standards will structure the development of “bright line” rules and “red button” responses Bright line rules are those established in the design phase that will guide the data collection and analysis process Red button responses are those that clearly articulate when data collection must be terminated, and what steps should be taken once such a response is needed

Lastly, organizations should establish internal and external feedback loops to assess data collection and analysis approaches throughout the process These mechanisms should include coordination with the ethics advisors and stakeholder working group, recommended above

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 2 1

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR QUALITATIVE DATA COLLECTION

Qualitative data collection can take several forms, including observation and monitoring, focus group discussions, key informant interviews, eyewitness accounts, participatory assessment workshops, profiling exercises, risk assessments or mapping, information ecosystem mapping, or community and incident reporting. Conducting qualitative data collection poses an array of potential risks: it may place the person disclosing information (‘informant’) at risk of harm, stigmatization, or violence for their participation; it may directly harm or traumatize the informant; it may reinforce existing stigmatizations; or it may place the enumerator at risk of harm, stigmatization, or violence

Because of these risks, qualitative data collection should only be pursued in ways that promote inclusivity and are based on trauma-informed, intersectional, age-appropriate, contextually relevant, culturally sensitive, and gender-sensitive approaches There must be an easily communicated plan that delineates when qualitative data collection is or is not appropriate and corresponding security protocols to ensure the safety and security of all involved

An ethical framework for qualitative data collection must incorporate the five following features:

I. Dynamic, continuous informed consent.

At a baseline, all data collection requires informed consent. Consent is a continual, dynamic process. At any time during data collection, the informant may revoke consent. When interviewing children and persons with intellectual disabilities, an enumerator must obtain informed consent from a parent or legal guardian, if they have one.

II. Trauma-informed approaches and active promotion of inclusivity.

Data collection can inadvertently result in traumatization or re-traumatization, especially for persons who have recently experienced violence Traumatization or re-traumatization in the process of data collection undermines the autonomy, agency, and dignity of the informant, and is more likely when enumerators conduct the discussion or interview in a way that is one-sided, extractive, or dismissive.

To mitigate these potential effects, all data collection must be guided by a trauma-informed approach, which requires all enumerators to be appropriately trained. A trauma-informed approach would require that:

Data collection occurs in a safe and secure location. This includes options for either complete privacy or having an additional support person present in the room, if desired. At the end of the discussion or interview, enumerators should again address any safety or protection concerns.

Lines of questioning are worded in a sensitive manner. Doing so supports autonomy and agency, avoids furthering blame or stigmatization, and recognizes the unique impacts, including psychological impacts, of experiencing trauma.

Lines of questioning about violence are carried out in a survivor-centered, gender-sensitive, child-sensitive, and child-competent manner. If an enumerator is not trained in these approaches, then they should not be addressing such content.

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 2 2

Enumerators are informed of local social and psychological support services available to assist informants. Contact information should be provided at the time of the discussion or interview If there are no support services available, then any line of questioning or discussion that may result in traumatization or retraumatization must be terminated ⁴⁵

A trauma-informed approach is relevant for focus group discussions, key informant interviews, participatory assessment workshops, risk assessments, surveys (in the phrasing and framing of questions as well as in interactions with informants, if applicable), and community and incident reporting In observation, monitoring, and eyewitness accounts, the enumerator must take care to use rights-based language that does not undermine the autonomy, agency, or dignity of the persons being described. IOM has provided guidance on implementing a rights-based approach to its programming, including across different forms of data collection.⁴⁶

III Recognition of the importance of an intersectional approach, including how certain identities can increase the harm, marginalization, and vulnerabilities that an internally displaced person may face

Qualitative data collection occurs in contexts rife with political, social, cultural, and other challenges

Enumerators must understand how to navigate these challenges prior to initiating data collection Without understanding the local context, it is possible for enumerators to perpetuate blame and stigmatization Understanding context can be done in collaboration with local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) that have insight into on-the-ground realities This collaboration should, as much as possible, be grounded in an inclusive approach by engaging with local organizations that focus on marginalized identities, such as women’s organizations or organizations for persons with disabilities Other potential actors to consult include humanitarian, development, or government stakeholders, who may already have insight through existing risk assessments or local connections

An intersectional perspective recognizes the marginalizing impact of specific identities, as well as how the intersection of identities can compound marginalization and risk of harm All participation of these persons should be accessible, consultative, collaborative, and inclusive An intersectional approach will recognize the status and influence of power differentials between persons, which can arise from economic, social, and political hierarchies This approach also considers structural drivers of violence that can place certain people in situations of increased vulnerability Identities considered by an intersectional approach include, for example, age, gender identity, gender expression, sexual orientation, sex characteristics, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, religion, nationality, caste, indigenous status, legal or displacement status, disability status, and status as a linguistic minority ⁴⁷

IV Clear delineation of when data collection is not appropriate or should be terminated, including a set of easily understood safety and security protocols

Given the potential risks associated with both qualitative data collection and internal displacement, it is critical that there are protocols outlining when data collection is inappropriate or must be terminated. These protocols must be flexible to respond to changing risk scenarios and apply to different communities. Data collection must not be initiated or must be terminated when:

BOOKENDS OF DISPLACEMENT 2 3

Data collection is not voluntary

Informants have not provided their free and informed consent

Qualified staff trained in trauma-informed, survivor-centered, child-sensitive, and child-competent approaches are not available

In addition, if an informant mentions violence but an enumerator is not trained in trauma-informed approaches, then data collection should be terminated

Qualified, trained staff who can overcome barriers to data collection are not available For example, male enumerators may not be able to safely speak one-on-one with females in particular contexts, so they should terminate data collection with those informants An organization should make every effort to identify an appropriate enumerator to resume data collection.

Risk assessments indicate that the risks of harm outweigh the potential benefits.

Local psychosocial support services have not been identified to support informants.

Enumerators or organizations cannot guarantee that the privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality of informants will be upheld.