Moving the Needle: A Strategy for U.S. Policy in Yemen

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

Policy Workshop Report

Fall 2021

Houthi rebel inspects the damage after an air strike in Sanaa.

Cover photo courtesy of AFP - Getty Images.

Houthi rebel inspects the damage after an air strike in Sanaa.

Cover photo courtesy of AFP - Getty Images.

Moving the Needle: A Strategy for U.S. Policy in Yemen

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

Policy Workshop Report

Fall 2021

Faculty Advisor

Ambassador Daniel C. Kurtzer

S. Daniel Abraham Professor of Middle East Policy Studies

Authors

Jacqueline Baumgartner • Merlin Boone • Garin Bulger • Dina Chotrani • Raisa Chowdhury •

Alex Gephart • Baher Iskander • Jack McCaslin

(below) With Ambassador Moosa Hamdan Al Tai at Omani Embassy, Washington, DC

(right) With Special Envoy Timothy Lenderking and Deputy Assistant Secretary Daniel Benaim at State Department, Washington, DC

(left) With Special Envoy Timothy Lenderking at Princeton University, Princeton, NJ

(below) With Ambassador Moosa Hamdan Al Tai at Omani Embassy, Washington, DC

(right) With Special Envoy Timothy Lenderking and Deputy Assistant Secretary Daniel Benaim at State Department, Washington, DC

(left) With Special Envoy Timothy Lenderking at Princeton University, Princeton, NJ

Policy Insights

Beating a dead horse: Should the United States continue supporting the Hadi-led ROYG?

“The more they eat, the hungrier they get”: Houthi strategy after the fall of Marib

“A pariah state”: Should the United States break with Saudi Arabia?

Is the U.S. Congress a barrier to the peace process in Yemen? The “bloody nose” approach: Putting U.S. military options on the table

Table of Contents 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 1 3 5 14 22 31 32 34 36 Executive Summary Background to the Conflict Key Actors Shortcomings of Past Approaches to Resolving the Yemen Crisis Moving the Needle: Proposed Strategy Conclusion List of Interviews Workshop Participants Endnotes 6 8 10 16 30

• • • • •

Preface

This report is the final product of a policy workshop sponsored by the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs as part of the Master in Public Affairs degree program. It results from the work of eight graduate students advised by Ambassador Daniel Kurtzer. The report’s content was briefed to the U.S. Special Envoy to Yemen, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Arabian Peninsula Affairs, and the NSC Director for Political-Military Affairs (MENA) on December 7, 2021.

The report’s information and recommendations stem from months of research and interviews with current and former government officials from the United States, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen, researchers, members of civil society, and UN officials. A list of those we interviewed can be found at the end of the report. The group conducted virtual and in-person interviews in Princeton, Washington, DC, and New York City.

Throughout the report, we make reference to some of those we interviewed by name, indirectly by title, or merely as a workshop interview. This was done at the requests of those we interviewed to allow them to speak freely and for us to use the information they gave us. The report does not necessarily reflect the views of any individual author, facilitator, Princeton University, the U.S. State Department, humanitarian professionals, or any person or their affiliated organizations interviewed as part of this workshop.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the many people who supported us during our workshop. We thank the government officials, researchers, and others who generously lent their time and expertise to us. Their contribution to our understanding of the Yemen conflict was invaluable.

We would like to thank Ambassador Kurtzer for his mentorship and Bernadette Yeager for her support during our workshop. We are also thankful for Dean Amaney Jamal, Associate Dean Karen McGuinness, Associate Director of Finance and Administration Ryan Linhart, and everyone else at SPIA who helped make this workshop possible.

Page i

The war in Yemen is in its seventh year. Hundreds of thousands of Yemeni people have been killed by hunger, disease, and fighting, while millions more have been internally displaced. Though often overshadowed among policymakers and in the media by regions perceived as more important to U.S. interests, Yemen remains a priority for the Biden administration. Biden came into office committed to ending the conflict, and in February 2021 he appointed Ambassador Timothy Lenderking as a Special Envoy for Yemen.

A complex web of actors, shifting interests, and fraught alliances characterize the conflict. The situation contains three layered conflicts in one: between the UNrecognized Republic of Yemen Government (ROYG) and the Houthis; the Houthis and Saudi Arabia; and Saudi Arabia and Iran. U.S. involvement in the conflict began with the Saudi-led Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) intervention in March 2015, shortly after the Houthis unseated the UNrecognized government at the end of 2014.

In this report, we chose to limit U.S. objectives to mending the U.S.-Saudi relationship and achieving a Saudi-Houthi détente. We assess that Saudi Arabia is indispensable to the Biden administration’s goal of ending the war. Not only does Saudi Arabia’s historical intervention in Yemen form the basis of Houthi grievances, the

country also supports the anti-Houthi coalition and hosts the ROYG in Riyadh. It therefore has enormous influence over the outcome of the conflict. So too, do the Houthis, whose unexpected and largely unchecked military victories have given them control over roughly 70-percent of Yemen’s population.

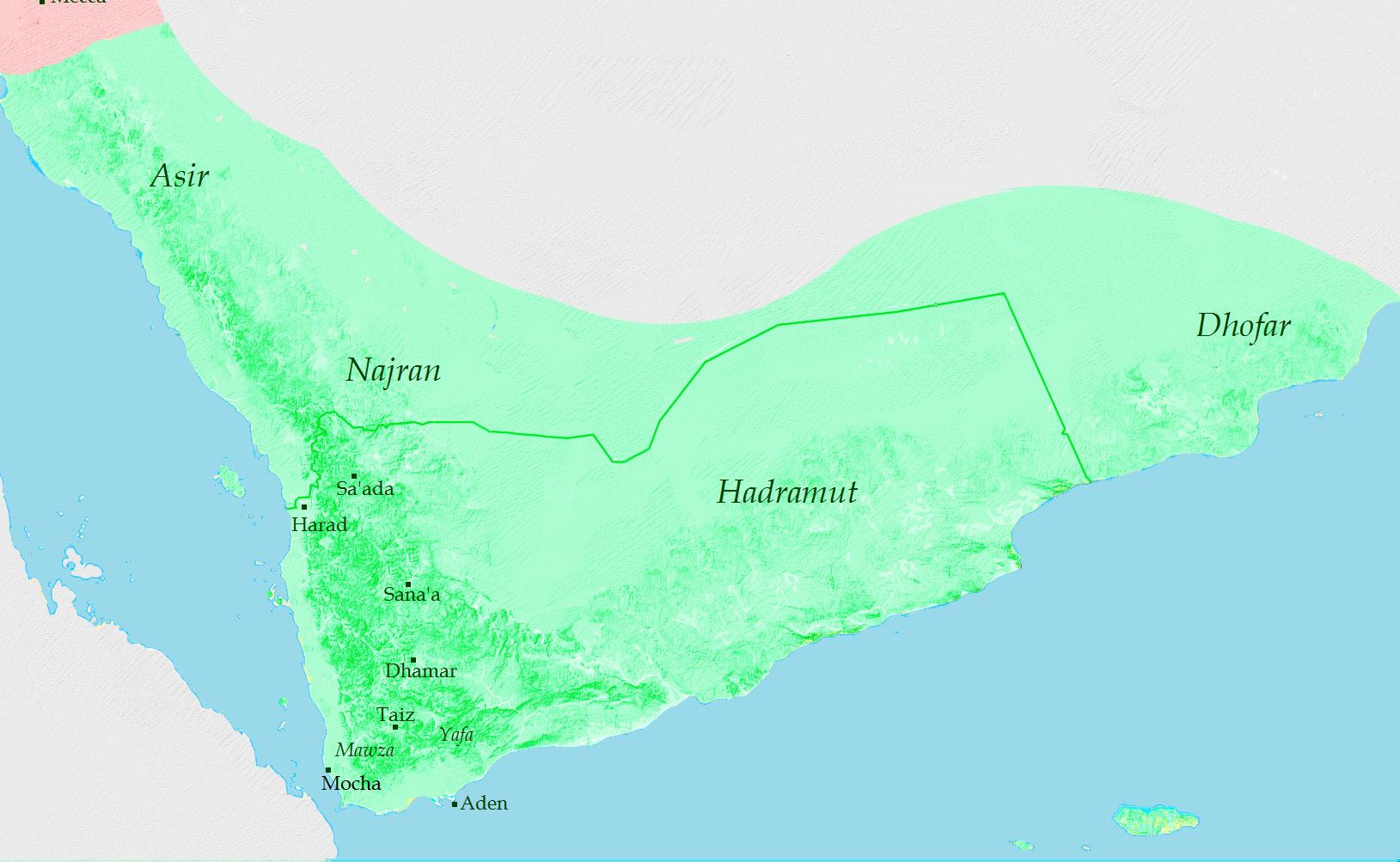

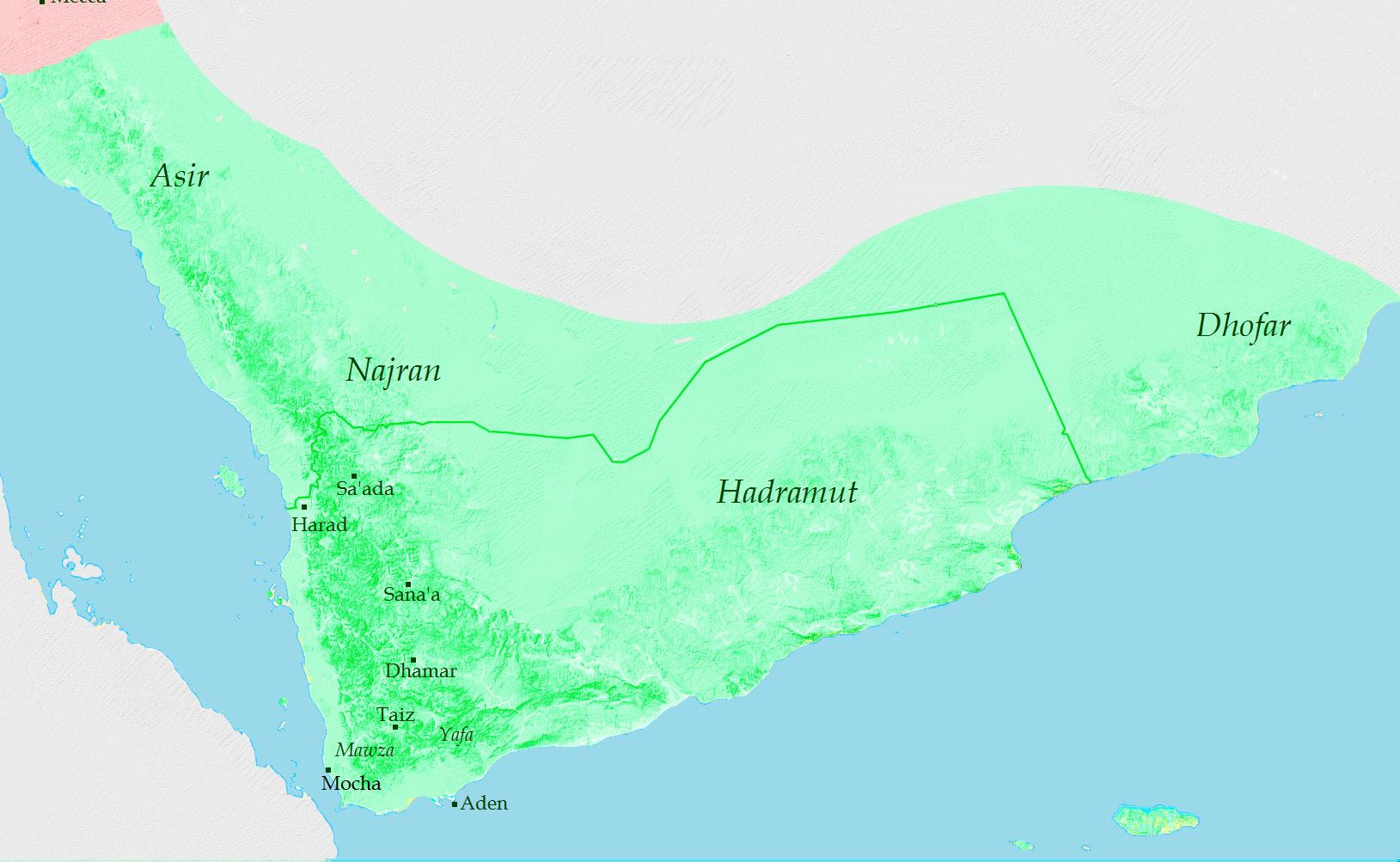

Houthi controlled territory

ROYG & controlled territory (nominally)

Our strategy focuses on the Houthi-Saudi relationship, and our goal is de-escalation between the two. We recommend a series of small, interim agreements between these two main actors. This approach departs from past efforts, such as the Stockholm Agreement and the Joint Declaration, which had pursued comprehensive settlements that sought to address a wide range of issues and involved

Page 1

1 | Executive Summary

Map of the Yemen conflict as of June 2019 European Council on Foreign Relations

a wide range of actors. We assess that smaller agreements with limited scope can lay the necessary groundwork for a future comprehensive Yemeni political agreement. Our strategy has two parts.

First, we call on the U.S. government to rehabilitate its relationship with Saudi Arabia. If the United States wants to help bring the conflict closer to an end, it must rebuild a close partnership based on trust with Saudi Arabia, given the latter’s central role in the conflict. Saudi Arabia is the party in the Yemen conflict that the United States has the greatest potential to influence.

Second, we call on the U.S. Special Envoy to intensify his parallel diplomatic negotiations

with the Houthis and Saudis to help address each side’s grievances, win concessions, and build trust. Two discrete near-term goals are an end to Houthi cross-border attacks into Saudi Arabia and a ceasefire in Marib. Longer term, our strategy aims to reach a ceasefire across all frontlines in order to lay a path toward normalization of relations between the Saudis and the Houthis so that each feels secure from foreign intervention and attacks.

Our strategy assumes the United States and Saudi Arabia would commit the necessary resources, including limited U.S. military strikes, to prevent the fall of Marib to the Houthis. We do not assume an inevitable Houthi victory in Marib. To focus on the strategy, our report does not engage in depth with related issues like counterterrorism, the humanitarian crisis, or internal Yemeni political dynamics or tribal politics. We discuss some spoilers (or disruptors) that could undermine our strategy, including the role of President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi, the U.S. Congress, and the potential fall of Marib, though this list is not exhaustive.

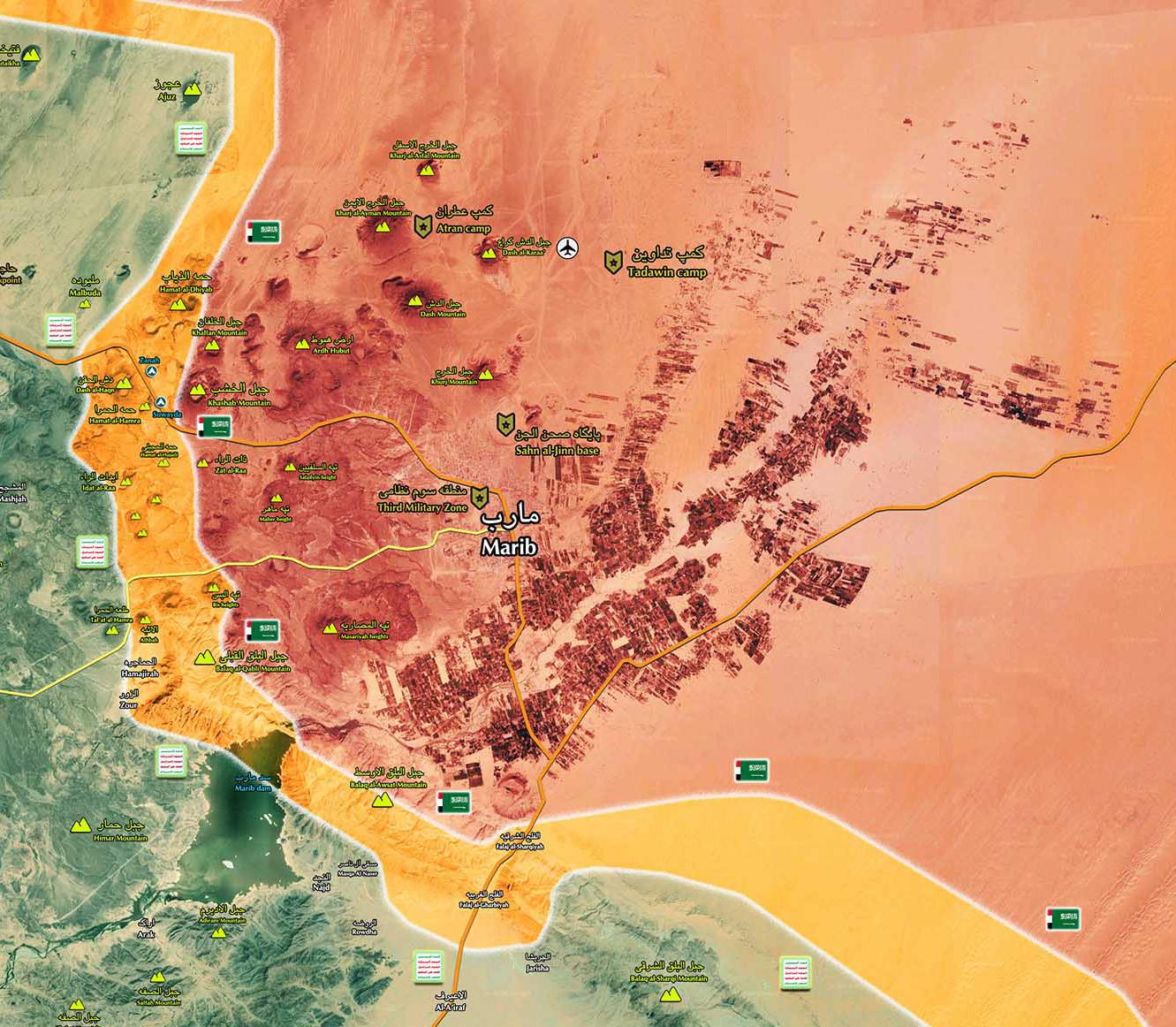

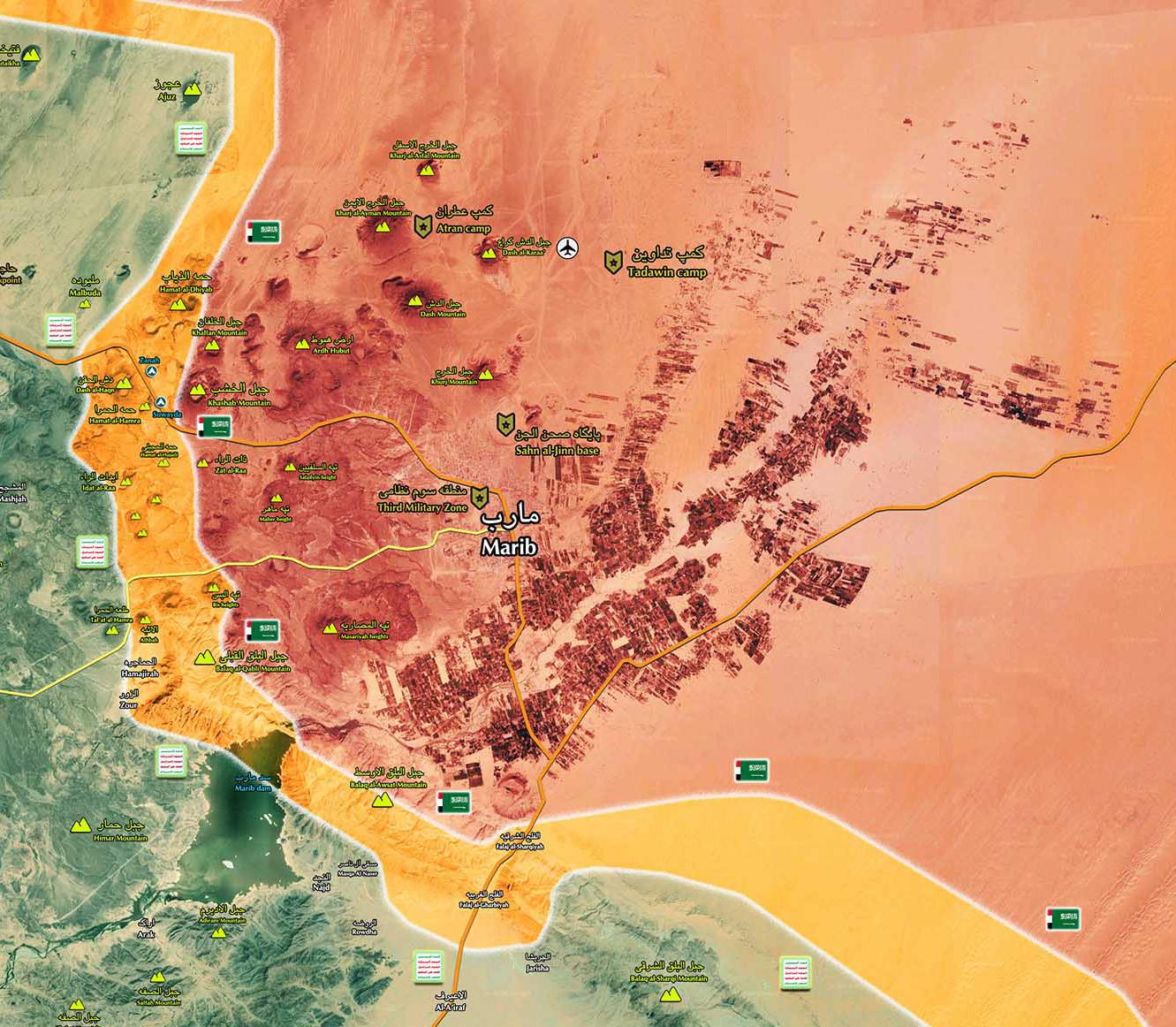

The front lines of Marib, December 2021 Islamic World News

ROYG controlled territory

Contested territory

Houthi controlled territory

Page 2

2 | Background to the Conflict

The Imamate, Unification, and Civil War

In Yemen, conflict and division are nothing new. Beginning in 897 CE, an Imamate administered political and religious rule over different parts of modern-day Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Oman.1 After it gained independence from the Ottoman Empire following World War I, the Imamate ruled in northern Yemen until a revolution in 1962 ushered in republican rule. 2 South Yemen gained independence from British colonial rule in 1967 and soon became a Marxist state with close

Saada Wars

Saleh’s government waged a series of wars from 2004 to 2010 in the Saada governorate against the Houthi family and its followers. The conflict was triggered by public demonstrations against Saleh that escalated into a series of battles in which the main opposition leader was killed under contested circumstances at the hands of the Yemeni military. These wars allowed the Houthi movement to demonstrate its resilience and expand across northern Yemen.5

Arab Spring

In 2011, the wave of protests gripping the Arab world, later dubbed the Arab Spring, spread to Yemen. Protests broke out against Saleh’s three-decade autocratic rule. By the end of the year, Saleh agreed to step down and was replaced by his vice president, Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi. Hadi’s term as President was originally supposed to be for two years as part of a transition arrangement partially brokered by the GCC.6

ties to the Soviet Union.3 The North and South merged to create a unified Yemen in 1990. The South had joined to achieve economic stability but grievances mounted due to economic marginalization and political violence. Civil war broke out in 1994, but within two months, northern forces led by Ali Abdullah Saleh triumphed, leading secessionist leadership in the South to go into exile and take its movement underground.4

National Dialogue Conference

In March 2013, the 565-member National Dialogue Conference (NDC) commenced. The goal of the NDC was to determine the political reforms necessary to create a structurally sound and united Yemen. Comprising eleven working groups and a nine-member presidency, the NDC included most significant interest groups in Yemen, including the General People’s Congress (GPC), the Islah party, the Houthis, southern socialists, tribal leaders, and civil society

Page 3

The Yemeni Zaidi State in 1597 under Al-Mansur al-Qasim Wikimedia

organizations. The NDC decided to transition Yemen into a six-district federated system, with Sana’a and Aden becoming special zones outside the districts. However, the Houthis felt their political power had been severely diluted through the district creation process, and they withdrew their support for the new constitution. Additionally, many southern Yemeni leaders boycotted the entire conference.7

Houthi-Saleh Alliance Takes Sana’a

In 2014, the Houthis expanded their control in the north by signing non-aggression pacts with several northern tribes. They moved into the capital of Sana’a with little resistance with help from forces loyal to Saleh, who had formed an

alliance with the Houthis against Hadi’s government. In September 2014, the Houthis pressured President Hadi to sign an agreement that granted both Houthis and southerners a place in his government. This agreement lasted five months before Hadi fled to Aden.

GCC Coalition Intervention in Yemen

As the Houthis continued their push to take the southern governorates in 2015, Saudi Arabia led a GCC military intervention in March 2015 to restore the internationally recognized government to Sana’a. Initial successes later settled into the stalemate of the last few years.8 The damage from military hostilities has led to a humanitarian catastrophe across all of Yemen. The economic situation remains dire. The Houthis have only been emboldened with their military victories—and they seem intent to take over Marib, the strategic oil rich city in the north.

Page 4

Protestors calling for the ouster of President Saleh during the Arab Spring Suhaib Salem/Reuters

Key Actors

Republic of Yemen Government

The ROYG is the UN-recognized government of Yemen. It is led by President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi, the former vice president to President Ali Abdullah Saleh. The government has been based in Riyadh since 2015 when Hadi fled Aden following the Houthi advance on the city.9 President Hadi formally requested outside support, providing the primary justification under international law for the Saudi-led coalition’s intervention in Yemen.10 Hadi’s primary partner in the government is the Islah party, an Islamist political party with links to the Muslim Brotherhood.11 Saudi Arabia brokered the Riyadh Agreement in 2019, which sought to ease tensions between the ROYG and the Southern Transition Council (STC), providing the latter a formal role in the internationally recognized Yemeni government. The agreement is yet to be fully implemented.12

The ROYG today is characterized by infighting and conflicting agendas. It is held together by its dependency on Saudi Arabia and antipathy toward the Houthis.13 Hadi is both reliant on and distrustful of his Saudi partners. He sacked the popular Khaled Bahah in 2016, fearing that the Saudis preferred Bahah to lead the ROYG, and in 2018 he fired his prime minister, Ahmed Bin Daghr, for bringing together expatriate GPC leaders. Bahah was replaced with General Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar, who was closely affiliated with the Islah party.14 The relationship between Hadi and Islah is a marriage of convenience since both were politically vulnerable in the

aftermath of the Houthi takeover of Sana’a. The Hadi-Islah alliance is driven primarily by self-preservation, resisting threats to each of their positions from the Houthis, the STC, and an array of other Yemenis and outsiders. This comes at the expense of strengthening the antiHouthi coalition and bringing an end to the war.

Houthis (Ansar Allah)

The Houthis now control territory that includes about 70 percent of the Yemeni population.15

The Houthis are a Zaidi revivalist group within Shia Islam. The contemporary movement began in the 1990s in response to the spread of Salafi institutes in their homeland and marginalization by the Sana’a government. After their leader, Abdulmalik al-Houthi, was killed by Saleh’s security forces, the Houthis fought the Saada wars against Saleh between 2004 and 2010, with Saleh’s militias receiving support from Saudi Arabia.16 The Houthis later took part in protests that led to Saleh’s resignation during the Arab Spring and participated in a GCCsupported National Dialogue Conference in 2014. The Houthis later teamed up with Saleh after his resignation, and took Sana’a, unseating the internationally recognized government led by President Hadi. Without a strong military or national base of support, the Houthis benefited from Saleh’s control of military forces and were eventually able to use Saleh’s GPC patronage networks to infiltrate the government, even after the Houthis killed him in 2017.17

Iran’s support to the Houthis has strengthened

|

3

Page 5

Beating a dead horse: Should the United States continue supporting the Hadi-led ROYG?

The denouement of Afghanistan’s former government serves as a warning for U.S. policymakers. Supporting a corrupt government that has little to no support from its people is a recipe for failure. The official government of Yemen maintains our support even though it bears the same warning signs that characterized Ghani’s government before it fell.

U.S. policymakers must ask: What value does Hadi’s leadership offer and what are the downsides to supporting his government? It is true that Hadi remains the official representative of the internationally-recognized government of Yemen. He has also been supportive of U.S. counterterrorism operations inside Yemen. But Hadi carries no domestic legitimacy with his people. Interviewed Yemenis emphasize this point—the man is extremely unpopular. His government has been in exile for years, which is both a cause and a symptom of his country’s lack of trust in his leadership. Further, Hadi has made peace more difficult to attain. “Incentives for Hadi to negotiate a deal are close to zero,” relayed one analyst, “once he negotiates a deal, he is negotiating himself out of power.”43

After assessing the benefits and risks of supporting Hadi, U.S. policymakers should ask their Saudi and Yemeni partners the following questions: Is there a suitable replacement for Hadi? What is the roadmap that could lead to the ROYG returning to Yemen? Should there be a different model considered for governing Yemen—such as a weak figurehead, with stronger, more autonomous governors in charge of the various parts of Yemen? Unless a strong case has been made to support Hadi’s government, the United States should remove Hadi from its plans for a post-war Yemen.

Page 6

ROYG President President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi in 2019 Hamad l Mohammed/Reuters

Houthis (continued)

over the past few years. Iran was one of five countries with diplomatic missions in Sana’a in 2015 after other embassies pulled out. The group also received Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Hizballah members for security and military training. Houthis regularly receive weapons shipments from Iran and some Houthi leaders have been hosted in Tehran for training and indoctrination. Many of our interviews emphasized that the solution to Yemen “lies in Tehran,” not Riyadh.18

The Houthis have sought to secure their border with Saudi Arabia, undercut and marginalize the Hadi-led government, and end foreign intervention in Yemen.19 These three goals have not fundamentally changed, but specific Houthi demands have evolved. In April 2020, the Houthis laid out a set of demands for peace. It called for a ceasefire overseen by the UN, “brotherly relations” with Saudi Arabia, and the end to foreign interference in Yemen. It called for the end of land, air, and sea blockades by the coalition and the demilitarization of border crossings, all of which would presumably make it easier to smuggle in weapons. It also demanded the coalition provide compensation to all those affected by the war, taking virtually no responsibility for rebuilding or governing Yemen. 20 In December 2021, the Houthis called on the Saudi-led coalition to arrange a ceasefire and negotiate an end to the war under the auspices of the UN. 21

Southern Transitional Council

The STC is a southern political entity founded in 2017 by Hani bin Breik and Aidroos al-Zubaydi. It grew out of the Southern Movement, or Hirak, a protest movement against President Saleh that began in 2007. The protests had roots in the outcome of the 1994 Yemeni civil war, when southern secessionists sought to divide the just-unified Yemeni state, only to lose to forces led by then-President Saleh. 22

When the Houthi-Saleh alliance invaded parts of the south in March 2015, the movement quickly transformed into the Southern Resistance and was supported by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in its campaigns against al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the Houthis. 23 Though it does not represent the entire southern region, the STC is currently in control of Aden, the de facto seat of the ROYG in Yemen, and it has support in Dhale, Lahij, and the western Abyan governorates. 24

Given present and historical animosities, the STC has a complicated relationship with the Hadi-led ROYG. While it advocates for southern independence, it has also publicly supported Hadi as the legitimate president in the context of the anti-Houthi coalition. In January 2018, the STC seized control of the Aden government from Hadi-aligned officials. Clashes between government forces and STC forces continued throughout 2018 and into 2019. The fighting

Page 7

“The more they eat, the hungrier they get”: Houthi strategy after the fall of Marib

Our recommendation assumes Marib remains under the control of ROYG forces for the short term. Should the city fall to the Houthis, two questions ensue. First, will the Houthis stop their military campaign, or will they continue onto Shabwa and the south? Second, will the ROYG collapse?

We assess that the Houthis, emboldened by their victory and empowered by access to new oil revenues, will continue their military campaign beyond Marib. Some analysts we spoke with emphasized the Houthis’ predilection for fighting over governing. Houthi history demonstrates a tendency toward fighting rather than consolidating gains, especially since they have no experience with governance. Houthi ideology is also laden with visions for conquering all of Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Iran will likely support their campaign eastward and capitalize on their new victory. For these reasons, we assess that Houthi fighting will continue. To be sure, some voices within Houthi ranks will prefer to parlay victory in Marib into a maximalist negotiating position. Those are the moderate, pragmatic voices that the United States and Saudi Arabia should empower and elevate.

A defeat in Marib will likely spell the end of the Hadi-led ROYG. President Hadi is on the record claiming that he will not let the city fall.44 If it does, his scant legitimacy in Yemen would be gone. A scramble for new leadership, driven by the Saudis or other partners, would likely ensue. The ROYG’s collapse may also prompt Saudi Arabia to abandon their ineffectual partner altogether and to seek accommodation with the Houthis, exchanging a reduction of Saudi support to the ROYG for an end to Houthi rocket attacks. In tandem, the STC may feel liberated to abandon the ROYG to deal directly with the Houthis; according to our interviews, this is a prospect that has been considered.

Page 8

STC (continued)

intensified in August 2019, when advancing government-backed forces were turned back by UAE airstrikes that killed hundreds of soldiers. 25 In November 2019, Saudi Arabia brokered the Riyadh Agreement which aimed to stop the intra-coalition fighting by establishing a new unity government that included representatives from the STC. 26

The STC’s main interest is independence for the south of Yemen. According to one STC official, the “crux of our struggle against the Houthis in the south has been to achieve independence and reestablish the state of southern Yemen.”27 In the short term, the STC wants international recognition and legitimacy. It would prefer that international actors drop their insistence on supporting Hadi and on a unified Yemen government. Our interviews affirmed that the STC continues to resist the Houthis and terrorist groups, including AQAP and the Islamic State (IS).

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia has a long history of intervention in Yemen. In 1933, just one year after the establishment of the modern state of Saudi Arabia, a border dispute drew Saudi forces into open conflict with their southern neighbor. The war resulted in the expansion of Saudi territory, which remains a source of grievance for the Houthis today. 28 Historically, Saudi intervention has been characterized by financial and military support to various sides to skew internal

Yemeni disputes in its favor. Saudi Arabia’s overall goal has been to maintain stability in Yemen to prevent its problems from spilling over the border, while ensuring the country remains dependent, weak, and friendly to Saudi leadership. 29

Saudi involvement in the current crisis began during the Arab Spring, when the GCC helped facilitate a transition plan to end President Saleh’s 33-year rule.30 After what appeared to be a successful transition, Saudi Arabia—which was instrumental in negotiating Saleh’s exit and Hadi’s appointment—was not deeply involved as the GCC transition plan played out through the NDC.31 The plan fell apart when Houthi forces and forces still loyal to Saleh in the Yemeni military joined together and took Sana’a in 2014.

On March 22, 2015, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announced Operation Decisive Storm, initiating the now seven-year-long Saudi intervention. The Crown Prince’s exact motives for intervening were not certain, but some argue that “it had more to do with Iran than with Yemen itself,” specifically concerns of Iran’s influence over the Houthis.32 Since 2015, Saudi Arabia has received U.S. military equipment and assistance with targeting and aircraft maintenance, although its primary partner on the ground in Yemen has been the UAE. When the war began, the Saudis focused on the north and the Emiratis on the south and the coasts.33

Today, Saudi Arabia is increasingly pushing for

Page 9

“A pariah state”: Should the United States break with Saudi Arabia?

When it comes to U.S.-Saudi relations, the options available to the administration range from complete decoupling to rehabilitating and returning to a strong relationship marked by mutual trust. Our research leads us to advocate for the latter approach. A stronger relationship with Saudi Arabia serves current U.S. interests in Yemen, and it will reap dividends in the future.

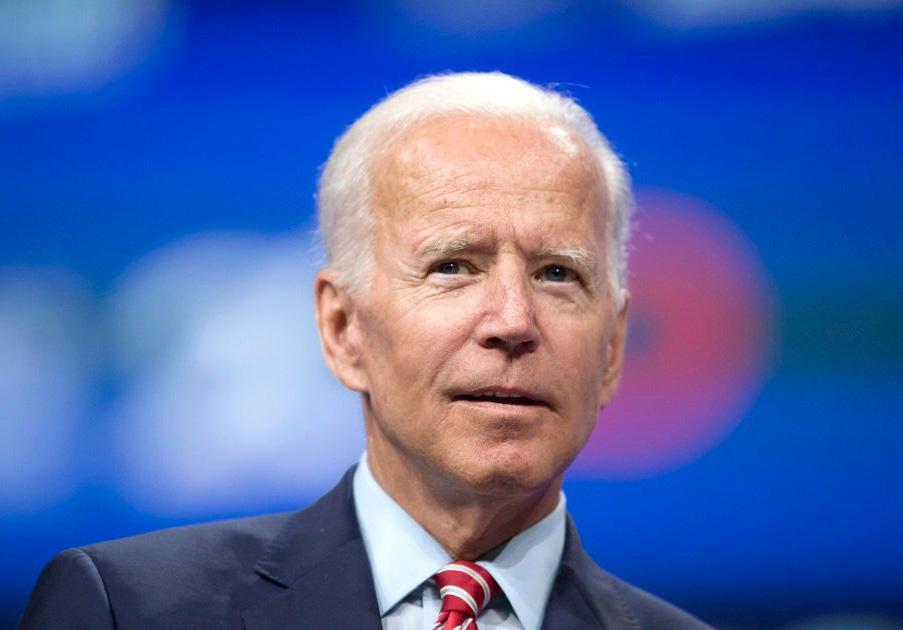

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud (MBS) (Saudi Royal Court/ Reuters) and US President Joe Biden (Michael Stravato/The Texas Tribune)

If the United States wants to prepare for global competition with China, it must maintain alliances at strategic chokehold points beyond the Indo-Pacific, such as the Arabian Peninsula, over which Saudi Arabia enjoys regional leadership. Saudi Arabia will continue to exercise influence within the Muslim world given its custody of Islam’s holiest sites as well as being a regional leader. Barring an extreme event, Mohammed bin Salman is slated to rule the country for the next several decades, and he is seeking to expand his country’s influence, transforming it into an economic and cultural hub for the Arab world. Given the Crown Prince’s young age, it would be prudent for the United States to maintain and strengthen the bilateral relationship in order to hold some sway over his country’s behavior for the foreseeable future. If we do not repair our relationship with Saudi Arabia, we lose influence over the Arabian Peninsula and cede its strategic value to competitors.

History suggests the U.S.-Saudi relationship is extremely resilient. It has managed challenges across successive administrations, surviving tensions over Israel; the oil embargo of 1973; the discovery of Chinese ballistic missiles in 1985; the 9/11 terrorist attacks; the boycott (and potential invasion) of Qatar; and the brazen murder of a U.S. permanent resident and journalist. The U.S. would do well to look beyond Saudi Arabia’s failed policies in Yemen to see their value as a strategic partner and potential friend for the future’s largely unknown contingencies.

Page 10

Saudi Arabia (continued)

a negotiated resolution to the conflict, spurred by U.S. and UN support. It is searching for ways to exit gracefully in the face of surprising Houthi victories. In March 2021, the Saudis released a peace plan and ceasefire arrangement, which was rejected by the Houthis.34 Saudi Arabia remains concerned about its security in the face of a near daily barrage of drone and rocket attacks from Houthi territory and the possibility of greater Iranian presence on the Arabian Peninsula.

Iran

Iran’s involvement in the Yemen conflict is characterized by strategic opportunism. Iran provides security assistance and training to the Houthis. Specifically, our interviews affirmed that Iran’s IRGC has provided weapons and assistance in setting up security directorates and establishing a police state in the northern territories. To be sure, Iranian support to the Houthis was not inevitable. President Rouhani of Iran had sought détente with Saudi Arabia, but he faced internal opposition. Iranian hardliners who opposed normalization with Saudi Arabia found the Houthis a suitable partner in Yemen to achieve their interests. Supporting the Houthis with weapons and training was a cheap and convenient way to drain Saudi coffers. Hardliners accused Saudi Arabia of funding

anti-Iran movements across the Middle East, an accusation punctuated by the Saudi execution of a Shia dissident cleric in January 2016. Following the death of King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, who had sought to reduce tensions between Riyadh and Tehran, and the rise of King Salman, Iran increased its involvement in Yemen.35

The Houthi-Iran relationship is fraught, and it would be incorrect to describe the Houthis simply as an Iranian proxy in the likes of Lebanon’s Hizballah. Unlike Hizballah, the Houthis have their own history and ideology that stand apart from Iranian doctrine. They maintain a deep sense of sovereignty over their territory. Indeed, the Houthis have publicly criticized Iran, like when the latter announced plans to build a naval base in Yemen. 36 Iran’s role in Yemen is further complicated by internal Iranian division.

Iran Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei Reuters

Page 11

For example, the Iranian embassy in Yemen did not support the Houthi takeover of Sana’a, but the IRGC did.37

For its part, Iran’s influence in Yemen is limited. Their support for the Houthis comes in the context of entanglements in other conflicts— Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria—and punishing U.S. sanctions. That said, the future of Iran’s role in Yemen, particularly following a potential Houthi victory in Marib, remains unclear. Some analysts have suggested that Iran may seek to dramatically increase its partnership with the group, leading to a “Hizballah 2.0” inside Yemen.38

United Arab Emirates

The UAE had been Saudi Arabia’s primary and most effective foreign military partner in Yemen from 2015 to the downsizing of its military footprint in 2019. Emirati operations occurred principally in southern Yemen and were characterized by the cultivation of local fighting forces that achieved early successes against Houthi forces and later AQAP forces. The UAE has two immediate goals in Yemen: (1) degrade and defeat AQAP and IS, and (2) prevent Houthi-domination of Yemen that would provide a foothold for Iran on the Arabian Peninsula. For the UAE, Iran’s ability to disrupt shipping routes and oil exports while waging asymmetric warfare through proxies all drive its regional “risk reduction strategy.39

The UAE’s significant role in the GCC coalition

is complicated by two contradictions, one emanating from the UAE and the other from its proxy forces. First, the UAE strongly dislikes both the Islah party, based on the party’s affiliation with the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Hadi-led government, which lacks legitimacy and competence. Second, as Emirati proxies achieved success on the battlefield, southern secessionist sentiment was reignited and empowered, undermining the UAE-ROYG relationship. These two fissures in the antiHouthi coalition have not yet been resolved.

To project power and influence in its neighborhood, the UAE has acquired ports and licenses for its firms to operate, developed closer ties with Ethiopia, and established military bases in Somaliland and Eritrea.40 For example, the Assab base in Eritrea has been used by Emirati special forces to train Yemeni fighters and to send Sudanese soldiers to fight in Yemen. The UAE ultimately seeks to achieve the ability and the legitimacy to protect vital maritime trade routes, making itself valuable to regional and international actors.

In 2019, the UAE conducted a “downsizing” that has been mischaracterized as a withdrawal. According to the UN’s Yemen Panel of Experts, the Emiratis maintain operational control over roughly 90,000 fighters throughout Yemen.41 Ultimately, the impact of UAE’s intervention in Yemen lies in its fracturing of the anti-Houthi coalition and its empowering of the southern secessionist movement.

Page 12

Oman

Oman has ensured its security through a strategy of peaceful coexistence and careful balancing, eschewing military intervention. It cherishes its status as a “neutral” player that can engage all parties. When Saudi Arabia began its military intervention in Yemen in March 2015, Oman was the only GCC member that did not join. Our interviews made clear to us that Oman does not consider the Houthis a direct threat to its security.

Oman has three broad interests in Yemen. First, it wants to ensure a stable border region. Second, it wants the Mahra governorate in Yemen, which borders the Omani province of Dhofar, to be free of extremism and Saudi or Emirati influence. (Given historical, cultural, and economic ties, Mahra is the one foreign region where Oman is willing to exercise significant influence.)42 Third, Oman wants good relations with its neighbors: Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Yemen. Indeed, Saudi Arabia has come to lean more heavily on Omani diplomacy to end the war peacefully, evidenced by frequent visits between Saudi and Omani officials. According to our interviews, Oman holds no preference on a united or bifurcated Yemen.

Oman has cultivated close ties with parties on all sides of the conflict in Yemen, including the Houthis, Iranians, and Saudis. These relationships have enabled Oman to host Houthi leaders for extended periods, facilitating their communication with other parties to the

conflict, and to mediate hostage releases and prisoner exchanges.

Page 13

4 | Shortcomings of Past Approaches to Resolving the Yemen Crisis

The U.S. Approach

The broader U.S. approach to Yemen should be viewed in the context of the U.S.-Saudi relationship. Despite rhetorical flourishes and some recalibration in the wake of the murder of Jamal Khashoggi and indiscriminate Saudi airstrikes inside Yemen, the United States has remained committed to the relationship. More recently, the United States has staunchly supported Saudi Arabia’s right to defend itself from Houthi rocket attacks. According to our interviews with people within the U.S. government and others, the United States has no stand-alone Yemen policy apart from Saudi Arabia.

The United States has an interest in preventing Iran from obtaining a foothold on the Arabian Peninsula, which would destabilize the region and undermine the security of Saudi Arabia and other Gulf countries.45 In terms of resolving the conflict and ending the humanitarian crisis, the United States continues to support a UN-led negotiated political settlement to the conflict. It has also sought to mitigate the humanitarian crisis through aid and economic relief.46

and September 11, the United States wanted a Yemeni government that would greenlight vast counterterrorism operations inside the country. It secured this capacity during President Saleh’s reign, and later under President Hadi.47

Support to the Saudi-led Coalition and Military Operations in Yemen

The United States, to varying degrees, has advised, supported, and armed the Saudiled coalition’s operations in Yemen against the Houthis. Over three administrations, this support has included arms sales, intelligence sharing, refueling and maintenance for Saudi jets, technical support to minimize civilian casualties in airstrikes, and the deployment of U.S. troops to Saudi Arabia after the 2019 Aramco attack. The United States has also been explicit in its support of Saudi Arabia’s border security. After the Houthis attacked a civilian airport in Abha, the State Department recognized the coalition’s military campaign as an act of selfdefense and asserted that Saudi Arabia “does face a threat from Yemen. We are standing with our partner.”48 Together, the Obama and Trump administrations were responsible for approving several billions of dollars in major weapons sales to Saudi Arabia.49

The

United States also has an enduring interest in securing key oil and commercial maritime routes through the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. After the al-Qaida attacks on the USS Cole in 2000

U.S. support for the Saudi-led coalition began in March 2015 under the Obama administration, which maintained logistical support for Saudi

Page 14

operations in Yemen, but in 2016, decided to reduce U.S. personnel support and limit certain U.S. arms transfers. The Trump administration followed by emphatically backing the Saudiled coalition and using the Houthi threat to the coalition as a justification to double down on countering Iranian influence in the region, including support to the Houthis.50 The administration decided to proceed with planned arms sales that the Obama administration had halted. President Trump thrice vetoed congressional bills that would have prevented U.S. military involvement in noncounterterrorism Saudi missions in Yemen.51

It is unclear whether U.S. support for the coalition has actually decreased under the Biden administration, which announced in February 2021 that it would end U.S. support for offensive operations in the war, including relevant arms sales.52 The administration initially paused the implementation of some arms sales approved by President Trump and initiated a process to review allegations of human rights abuses or violations of international humanitarian law that involved American air-to-ground munitions.53 But by November 2021, the Biden administration signed off on new military contracts collectively worth $600 million to allow Saudi Arabia to maintain its fleet of Apache attack helicopters and to provide it with missiles and interceptors following increased crossborder attacks from the Houthis.54 According to the State Department, “the United States is fully committed to supporting Saudi Arabia’s

territorial defense, including against missiles and drones launched by Iranian-backed Houthi militants in Yemen.”55

The U.S. role in Yemen is nevertheless limited. State Department officials that work on Yemen emphasized to us that the United States does not direct the war and is not a party to the conflict.56 A U.S. government employee with access to classified briefings underscored the surprisingly small role for the United States in Saudi Arabia’s Yemen operations. Regardless, Congress has been a source of significant pressure on the Biden administration to cut off all ties to Saudi Arabia over their policies in Yemen. Support (or antipathy) for Saudi Arabia has become entwined with American politics and its Iran policy. A U.S. government official relayed how polarizing the issue has become, “If Republicans are anti-Iran, then progressives need to be pro-Iran.”57

U.S. Policy at the United Nations Security Council

U.S. support for a UN-mediated resolution to the conflict has been unwavering. The United States has used its seat in the UN Security Council to publicly support the UN Special Envoy’s work and call out Houthi obstruction to the peace process during the Council’s monthly briefing and consultations on Yemen.58 It has also emphasized the importance of dialogue as the only way to achieve a stable and unified Yemen.59

Page 15

Is the U.S. Congress a barrier to the peace process in Yemen?

Saudi Arabia is unpopular among members of Congress and the U.S. public. Members of both parties, but particularly progressives in the Democratic Party, have repeatedly pushed the Trump and Biden administrations to weaken the U.S.Saudi relationship. Legislative efforts to censure Saudi Arabia for its policies or to ban weapons sales are likely to continue.

Members must ultimately decide if they are more interested in punishing Saudi Arabia than they are in ending the war in Yemen. Saudi Arabia’s involvement in the war could come to an end—a critical step toward lasting peace in Yemen—if it can find a graceful way out. But the Saudis first need to feel secure from Houthi attacks and Iranian incursion before this can happen. Congress cannot continue to undercut Saudi security while the administration is asking Saudi Arabia to end the fighting. As such, we think senior officials from the administration should be more proactive in explaining to congressional leaders, especially those members who are most vocal against Saudi Arabia, what is at stake in the relationship, and how a strategy based on a strong U.S.-Saudi relationship can be implemented to end hostilities in Yemen.

Further, the administration should more forcefully relay to Congress and the public the threat facing Saudi Arabia, making clear that Houthi rocket and drone attacks into Saudi Arabia—which have doubled in the first nine months of 2021 compared to the same period in 2020—impact American interests.81 U.S. interests include stability of oil prices, the safety of tens of thousands of U.S. citizens in-country, safe passage for goods, and global energy supplies. These interests should be well publicized and acknowledged by the administration.

Bringing senators and congressmen into the administration’s thinking might temper criticism and limit it only to the most insistent anti-Saudi voices. Indeed, Congress seems willing to listen to the administration—it bodes well that last month 67 senators voted against the recent Senate resolution of disapproval for foreign military sales to Saudi Arabia.

Page 16

Senator Bernie Sanders discussing the U.S. role in the war in Yemen Mandel Ngan/Getty Images

Successive U.S. administrations have also used the Security Council as a venue to pursue other U.S. interests as they relate to Yemen. In April 2015, the United States supported the passage of UN Security Council resolution 2216, which endorsed President Hadi and the ROYG as the legitimate government in Yemen and called on the Houthis to disarm and withdraw from Sana’a.60 In December 2017, then USUN Ambassador Nikki Haley used the Security Council to accuse Iran of providing weapons to the Houthis.61 Most recently, in October 2021, USUN Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield used the forum to condemn the Houthis’ October 3 missile attack on Marib, the Houthi siege of Abdiya, and Houthi cross-border attacks against Saudi Arabia at King Abdullah and Abha airports.62 According to a U.S. government official, the UN should have the lead role in internal Yemeni peace, but it needs the “buttressing of strong, powerful countries,” like the United States.

Terrorist Designations and Sanctions

The United States has used sanctions and terrorist designations to punish the Houthis’ destabilizing activity and pressure the group to change its behavior and come to the UN’s negotiating table. At the UN, the United States supported the passage of Security Council resolution 2140 in 2014, which established “financial and travel ban sanctions against individuals and entities threatening

the peace, security or stability of Yemen” and imposed targeted sanctions on Yemen’s former President Saleh and two senior Houthi rebel leaders. Also, Resolution 2216 included an expansion of the criteria for designating individuals as terrorists.63

The clearest use of these coercive measures against Houthi obstructionism was the Trump administration’s designation of the Houthis as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) in January 2021. This last minute action was intended to confront Houthi terrorist activity and advance efforts to achieve a peaceful Yemen free from Iranian interference.64 Although the Biden administration reversed the designation on humanitarian grounds, it maintained the designation of three Houthi leaders—Abdul Malik al-Houthi, Abd al-Khaliq Badr al-Din al-Houthi, and Abdullah Yahya al Hakim—as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs),

Page 17

Former Secretary of State Pompeo, who designated the Houthis a FTO Wikimedia

and it has added two other Houthi commanders to the list.65 The Biden administration also extended a maximum pressure campaign against Iranian financial support to the Yemen conflict. In June 2021, it sanctioned the head of an IRGC-linked financial network led by Houthi financial supporter Sa’id AlJamal, who is based in Iran.66

Appointment of a U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen

On February 4, 2021, President Biden appointed Ambassador Timothy Lenderking as U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen. The decision to appoint Lenderking, a diplomat with extensive experience in the Gulf region, demonstrated U.S. resolve to find a diplomatic solution to the conflict.67

Lenderking’s shuttle diplomacy in the region, with trips to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and many others, has reinforced the role of regional actors and backchannel negotiations in mediating an end to the conflict. The public-facing details of his travels suggest American urgency and resolve to seek de-escalation of the continued Houthi offensive in Marib, the return of the ROYG to Aden, and an immediate nationwide ceasefire.68 In February 2021, soon after taking office, Lenderking met with Houthi chief negotiator

Mohammed Abdulsalam in Oman, and the two have maintained contact.69 In September 2021, Lenderking accompanied National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan to a meeting with Saudi

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, where they discussed the need for an immediate ceasefire and intensified diplomatic engagement.70

The UN Approach

UN Security Council Resolution 2216 (2015)

UN Security Council Resolution 2216 codified an overly-simplified vision of the Yemen conflict by enshrining a power dynamic that does not reflect the realities of the conflict.71 It demands that the Houthis withdraw from all seized territory and fully disarm but offers no incentives for them to do so.72 Since 2015, the UN’s binary characterization has slightly

Page 18

Special Envoy Lenderking with Prince Khalid bin Salman Prince Khalid bin Salman/Twitter

broadened to accommodate the Saudi-led coalition and the Houthis’ relationship with Iran. It was further broadened by the 2019 Riyadh Agreement, which integrated the STC into the ROYG. However, it still fails to account for numerous independently-aligned non-state armed brigades and civil society organizations that have a stake in any future power-sharing agreement. According to one UN official, the predominant interpretation of the resolution deeply constrains the UN in its approach by only allowing it to consult, but not negotiate, with these other conflict parties.

Kuwait Talks (2016)

building measures (CBMs)—have determined the framework of successive UN-led mediation efforts.75

One UN staff member we spoke with criticized the approach taken in Kuwait, explaining that the UN wasted its political capital in gathering both parties in one place without “preparing the ground” for talks. Questions surrounding which actors to include in the room, as well as the right level of Houthi representation, distracted from the substance of the terms requiring negotiation. According to that official, at one point, the Houthis were so surprised by the UN’s proposed roadmap that they nearly walked out in the middle of talks.

Stockholm Agreement (2018)

Ould Cheikh Ahmed—hosted rounds

Between March and June 2016, the Kuwaiti government—with UN support and under the direction of the UN Special Envoy at the time, Ismaïl

of dialogue between the ROYG and Houthi representatives. In the lead up to the talks, the international community hoped the two parties would agree on a longer-term roadmap toward peace and more immediate-term steps to start implementing resolution 2216.73 However, after three months of draft agreements, the ROYG and the Houthis were not able to reach consensus on the sequencing of the new government’s formation and the Houthis’ withdrawal and disarmament. Each party conditioned their commitment on the other party’s willingness to move first.74 Despite its breakdown, the format of the Kuwait talks—two-party negotiations on a ceasefire and interim political and security arrangements, with interspersed confidence-

In December 2018, UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths brokered a local ceasefire in the besieged Red Sea port city of Hudaydah. Analysts refer to Stockholm as a mixed success.76 Some point to Stockholm as hopeful evidence that the UN can broker a ROYG-Houthi deal. However, others point to the enormous amount of pressure by international actors, such as the United States, that was required to secure the agreement. Though it was signed, international pressure has not been sufficient to force the parties to implement the deal.77

The agreement was problematic in other ways. The entire process was accelerated, lasting just a week, and many issues were left ambiguous or unresolved in an effort to reach a deal quickly.78

Page 19

Several of those we interviewed emphasized that Stockholm, by formalizing the joint ROYGHouthi administration of Hudaydah, emboldened the Houthis, allowing them to effectively freeze their control over the city and mobilize on other consequential conflict frontlines, including Marib. Emirati-backed forces were on the verge of taking the port city from the Houthis, and the agreement effectively saved the Houthis from defeat.

Joint Declaration (2020)

The Joint Declaration was a four-point plan proposed to the ROYG in June 2020 by then UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths. It has involved shuttle diplomacy between the Houthis and the ROYG to get them to agree to a set of CBMs that would pave the way for a resumption of peace negotiations. A UN staff member noted the pressure for Griffiths “to do something,” especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on Yemen’s dire humanitarian and economic situation. However, what Griffiths proposed—a nationwide ceasefire that freezes the frontlines, the opening of ports and Sana’a airport, agreement on an oil revenue-sharing mechanism, and a return to peace talks—was nothing new. Instead, it further perpetuated the status quo by providing several concessions to the Houthis in advance of peace talks, and it did not include a ceasefire enforcement mechanism.79

Of the four points, the first two are strategic military objectives—not symbolic, easy-to-

negotiate, quick impact CBMs—and require complicated political calculus to arrange. Combining multiple challenging and disparate issues—none of which has seen progress when negotiated separately—into one proposal entrenches their complexity and pushes the UN further away from an end-state that sees these issues resolved. This partially explains the lack of progress on the proposal.80

The four point plan additionally fails to provide a clear path to political talks, and its success depends too heavily on changing party demands and conditionalities. Within the framework, the Houthis, who are winning militarily, are not offered incentives to engage diplomatically in a meaningful way. As a result, the proposal has been co-opted by the parties as a stalling tactic to, in the words of a UN staff member we interviewed, “buy more time to create facts on the ground.” The big hurdle facing Griffiths’ successor, Hans Grunberg, is reducing mistrust between the parties. This issue should not be overlooked because it has the potential to undermine any future deal.

Page 20

5

Moving the Needle: Proposed Strategy

We believe that pursuing a series of small, bilateral interim agreements, rather than a comprehensive agreement that includes all parties, can bring the conflict closer to resolution. Focusing on the Saudi-Houthi relationship is a crucial first step toward a nationwide ceasefire to allow internal and international actors to focus on improving the humanitarian situation and prepare the ground for the UN to restart a political process.

Our strategy has two parts. First, the U.S. government should rehabilitate its relationship with Saudi Arabia. If the United States wants to help bring the conflict closer to an end, we believe that it requires a close partnership based on trust with Saudi Arabia, given the latter’s central role in the conflict. Second, the U.S. Special Envoy should intensify his parallel diplomatic negotiations with the Houthis and Saudis to help address each side’s concerns and secure concessions.

Our goal is to end Houthi attacks into Saudi Arabia and reach a ceasefire on all fronts in the conflict to lay a path toward normalization of relations between the Saudis and the Houthis. Achieving this

will provide sufficient space for Yemenis to decide their political future. Our strategy is best implemented as soon as possible. It is predicated on exploiting the political space that now exists, prior to a potential Houthi takeover of the oil-rich city of Marib.

Step 1 — Rebuild Saudi Relationship

The fulcrum of our Yemen strategy rests on a strong U.S.-Saudi relationship characterized by mutual trust. Before we can ask the government of Saudi Arabia for any concessions in Yemen— which we believe will be necessary to end the conflict—the United States must rapidly seek to rehabilitate the partnership. We believe

Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/Associated Press

Page 22

|

A Patriot missile battery at Prince Sultan Air Base in Saudi Arabia

taking any number of the following steps will strengthen the bilateral relationship, encourage mutual trust, and allow the Special Envoy to push the Saudis to take uncomfortable steps needed to end the conflict.

Publicly support Saudi Arabia’s role in ending the Yemen conflict. Top U.S. officials should use statements and speeches to reaffirm their support and commitment to the Saudi government, beyond their right to self-defense from Houthi aggression. We believe a trip to Riyadh by Secretary of State Blinken would communicate resolute U.S. commitment to the Saudi regime.

Provide additional offensive and defensive military support. Beyond public messaging, a significant increase in military and intelligence cooperation would go great lengths to improve the relationship. This could take several forms, including sending back Patriot batteries; restarting air refueling operations; sharing intelligence regarding battlefield developments and the targets of Houthi missile and rocket launch pads; or signaling our intent to share future c-UAS technology.

officials, like the Secretary of State, should be far more proactive in relaying to the public the threat facing Saudi Arabia and its impact on U.S interests. Private overtures by Secretary Blinken to members of Congress might also be necessary to secure their cooperation.

Step 2 — Parallel Diplomatic Tracks

After strengthening the bilateral relationship with Saudi Arabia, the U.S. government should turn its attention to two parallel streams of diplomatic negotiations—one with Saudi Arabia, and the other with the Houthis. These tracks are meant to be implemented in tandem, rather than sequentially. Inasmuch as the Saudis are offering concessions, the United States would ask more from the Houthis, and vice versa. Mutually reinforcing CBMs will allow the United States to offer calibrated assurances and guarantees in response to concessions from both parties.

Engage

Congress to limit criticism. We recognize that Congress will likely seek to limit some of these actions, but we think a frank conversation with key Congressional leaders that seeks to bring them into the administration’s thinking might temper criticism and limit it only to the most outspoken anti-Saudi voices. Senior

Page 23

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s interests in the Yemen conflict are shaped by their strategic competition with Iran and the security threat posed by Houthi drone and rocket attacks against Saudi infrastructure. Saudi Arabia does not want Iranian influence anywhere on the Arabian Peninsula, much less on their southern border. The Saudis also want to ensure that their oil supplies and pipelines remain secure, including through the construction and development of a pipeline through the Mahra governorate in eastern Yemen.82 With respect to a political outcome, Saudi Arabia wants a Yemeni state that is stable but weak, decentralized, and dependent on its support and largesse. Saudi Arabia has historically bought off various tribal leaders and cultivated politically pliable leadership in Yemen. We assess that Saudi Arabia will seek similar outcomes in a post-war Yemen.

Potential concessions to seek from Saudi Arabia

Loosen Hadi’s grip on the ROYG. The United States should encourage Saudi Arabia to take a number of steps to compel the Hadi-led ROYG to greenlight a political process that includes the Houthis. President Hadi’s resistance to powersharing has limited the ROYG’s ability to engage in political discussions that include the Houthis. Saudi Arabia maintains leverage over President Hadi; since 2015, it has hosted him and other exiled ROYG ministers in Riyadh. Removing this support to President Hadi may pave the way for other political structures to emerge, such as a presidential council that includes a broader

array of Yemeni political actors. Alternatively, the Saudis could encourage Hadi to replace Vice President Muhsin al-Ahmar, which might get the attention of the Houthis and be viewed as a CBM. Relatedly, Saudi Arabia should begin to cultivate alternatives for future Yemeni leadership. This includes continuing to engage with the UAE to settle differences regarding the future role of the STC.

Expand engagement with Houthi officials. The government of Saudi Arabia should maintain its private engagement with the Houthis, and expand it beyond intelligence backchannels. This should include more senior officials and prominent royals. Building these relationships will be necessary if Saudi Arabia is expected to deal with a Houthi-controlled northern Yemen.

Increase humanitarian access to Houthicontrolled areas. In order to alleviate humanitarian suffering, the United States should encourage Saudi Arabia to loosen restrictions at Hudaydah port and allow commercial and humanitarian-related flights through Sana’a airport. The Houthis have consistently stated that lifting these restrictions was a precondition for their agreement to a ceasefire. These initial steps would not only facilitate humanitarian relief efforts, but could also curry favor with the Houthis. This may also allow the UN to further pursue discussions on a port revenue-sharing mechanism to pay public-sector wages in Yemen. (Saudi strategy continues on the left pages of the spread.)

Page 24

Houthis

In tandem with U.S.-Saudi discussions, the United States should simultaneously engage the Houthis, making demands and offering them incentives in an effort to begin winding down the conflict. This will be a process of give and take between the United States, the Houthis, and Saudi Arabia. If the Houthis remain resistant to moving toward peace, the United States should consider limited military options.

The Houthis’ Interests

The Houthis’ interests are shaped by their marginalization by the Yemeni government for many decades, their opposition to Saudi intervention in Yemeni affairs, and their significant (and unexpected) military successes against the GCC coalition. In public statements and documents, the Houthis have made clear that they want an end to foreign interference in Yemen, an end to outside interference in the north specifically, and a larger role in Yemeni politics.83 Many of our interviews affirmed that the Houthis crave recognition and legitimacy, especially from the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the United Nations. They also need massive financial and technical support to rebuild war-torn territories after the fighting stops and actually start governing.84 The Houthis have successfully pursued their interests through war and with Iranian support. Their battlefield successes have weakened their opposition and increased their strength, giving them significant leverage in future negotiations. They do not have many

incentives to change course. If they take Marib, we believe the Houthis will continue pursuing more military victories.

Potential concessions to seek from Houthis

Before the United States offers anything to the Houthis, it should seek commitments from them. We propose that the Special Envoy seek the following concessions from the Houthis, which could be met with more Saudi concessions, thereby improving prospects for a ceasefire.

Vacate the U.S. embassy and release prisoners immediately. In November 2021, the Houthis occupied the U.S. embassy in Sana’a and took prisoner employees, some of whom remain captive.85 The Houthis should vacate the embassy complex before the United States can commit to greater political engagement or offer any substantial concessions. Yemeni embassy workers and others who are still held captive should be released.

Halt strikes into Saudi Arabia. Houthis should temporarily halt their cross-border rocket and drone attacks against Saudi Arabia as a CBM. The Saudis might offer concessions in return, such as a pause to their airstrike campaign around Marib.

Pause inflammatory rhetoric. The Houthis should tone down their hostile rhetoric (Houthi strategy continues on the right pages of the spread.)

Page 25

Saudi Arabia

Pause the deportation of Yemeni workers. The United States should encourage Saudi Arabia to address Yemen’s dire economic situation. As a short-term measure, it should pause any deportation of Yemeni workers in Saudi Arabia. The reduced flow of remittances back into Yemen, a cornerstone for the Yemeni economy, would affect millions of Yemenis and worsen the economic crisis.

Commit to rebuilding Yemen with GCC partners. Saudi Arabia should commit longterm reconstruction funds for rebuilding critical infrastructure in a post-war Yemen. It should also consider the integration of Yemen into the GCC. Access to the GCC would facilitate economic recovery by providing increased opportunities for Yemeni goods and labor. A more economically integrated Yemen would likely reduce Houthi dependence on Iran.

Commit more resources to the defense of Marib. Since a Houthi victory in Marib is not inevitable, the United States should pressure Saudi Arabia to channel more manpower and resources to secure Marib and provide a decisive blow to Houthi ambitions. Although the bombing has intensified since November, some of our interviews have conveyed that Saudi leadership does not view the battle over Marib as “existential”.

Wind-down support to Salafi institutes and militias in northern Yemen. Saudi Arabia should stop its support and funding of Salafist causes

in northern Yemen, an enduring grievance of the Houthis. During the war, the rise of Saudisupported Salafi militias has contributed to the overall destabilization of cities in northern Yemen.

How the United States can pressure Saudi Arabia

As previously noted, great effort should be taken to rehabilitate the U.S.-Saudi relationship for more effective cooperation on the Yemen conflict and other strategic issues. If Saudi Arabia refuses to cooperate, however, the United States should threaten to roll back some of the positive steps it had taken. The United States needs to carefully balance its threats over Yemen with the overall U.S.-Saudi bilateral relationship. Our strategy’s original intent is to restore trust by strengthening the bilateral relationship to cultivate a more cooperative partnership. Nevertheless, should they remain intransigent, the following actions may compel greater cooperation.

Reduce public support for Saudi Arabia. A shift in tone in U.S. statements regarding Saudi Arabia would communicate U.S. frustration. The United States could choose to make less supportive statements regarding Saudi defense, or it could make more outright condemnatory statements. There is substantial domestic frustration with Saudi Arabia and the administration could strategically channel this energy.

Page 26

Houthis

aimed at the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the international community. The group should also accept a meeting with UN Special Envoy Hans Grundberg in Sana’a as a sign of their commitment to a UN peace process, which they have publicly supported.86

Address governance problems. The Houthis should pay the salaries of their civil servants. This could be done through an escrow account with Hudaydah port revenues. Additionally, the Houthis need to allow the UN to safely dispose of the Safer. If it deteriorates further and its 1.1 million barrels of oil spill into the sea, it would be a major disaster for the region.87 Doing something about the Safer would demonstrate Houthi willingness to be a responsible actor in Yemen’s future. The Houthis should also allow greater humanitarian access to the territories they control.

Halt advance on Marib. A pause to the Houthi assault on Marib would send the clearest signal of Houthi commitment to a political process. Even a temporary ceasefire would allow greater humanitarian access to the more than one million people who have sought refuge from the war in Marib. Such a move could be rewarded with the loosening of restrictions on Hudaydah port and may also make Saudi Arabia willing to pause airstrikes.

Reframe relationship with Iran. In December, the Houthis sent home the Iranian ambassador to Sana’a. Though he was allegedly sent

home for health reasons (he died of COVID shortly thereafter), the Saudis have publicly interpreted this as a sign of decoupling.88 A new Iranian ambassador will replace him, but the Houthis could choose to reject him. Taking this or any number of steps that reduce Iranian influence or weaken the Houthi-Iranian relationship would be met with U.S. approbation and more Saudi concessions. The Special Envoy could also push for the expulsion of key IRGC officers currently in Yemen, as well as Syrian Hizballah fighters.

How the United States can influence the Houthis

The United States should help the Houthis secure some of their objectives in exchange for concessions that bring the conflict closer to an end. Some steps can be taken unilaterally by the United States while others will require Saudi cooperation.

Empower and engage with moderate Houthi leaders. Given internal divisions, it is difficult to understand the scale and scope of Houthi strategy. Their vision changes and expands as more time goes by. Nevertheless, those we interviewed have discussed the presence of moderate voices among its leadership. It is up to the United States, Saudi Arabia, Oman, and others who engage with the Houthis to legitimize those voices.

Support Houthi governance. If the United States promised political support to Houthi

Page 27

Saudi Arabia

Pausing foreign military sales. The United States has been Saudi’s largest arms supplier for decades. Despite the more recent weapons sales, the Saudis are requesting additional weapons to defend against Houthi aggression. The United States could leverage Saudi Arabia’s reliance on U.S. weapons to extract Saudi concessions.

Do not oppose anti-Saudi legislation. Gulf leaders listen closely to Congressional debates and legislation that pertains to them—and how the administration chooses to engage. If the administration does not signal opposition to anti-Saudi legislative initiatives, which are bound to continue over the coming years, it may well compel the Saudis to alter their behavior, particularly if these legislative efforts deal with weapon sales.

Remove the U.S. Special Envoy to Yemen. The appointment of the Special Envoy to Yemen was widely perceived as a positive development toward ending of the Yemen conflict. It sent the message that U.S. political leadership desires to see the conflict end. But it was also the messenger selected that gave the appointment weight. Ambassador Lenderking had spent three years as the Deputy Chief of Mission in Riyadh, and the Saudis prize personal relationships. If President Biden were to remove the Special Envoy, or threaten to do so, there would be substantially less attention given to the Saudi side of the conflict. Perhaps more importantly, it would signal U.S. frustration with their troublesome partner who remains uncooperative and responsible for allowing the conflict to drag on. The Saudis would prefer to avoid this perception and could make concessions to prevent such a dramatic outcome.

Page 28

U.S. Special Envoy to Yemen Tim Lenderking (left) Carolyn Kaster/Getty Images

Houthis

governance and offered it political legitimacy, this might lessen their dependence on Iran. Examples of these incentives include the promise of limited reconstruction funds, the restarting of some USAID development funding, toning down rhetoric critical of Houthi leaders and actions, as well as taking some Houthis off of the SDGT list.

Progressively legitimize the Houthis. The United States could progressively legitimize the Houthis as they take positive steps. If the Houthis can demonstrate that they can be a responsible actor, moving from a heraka (movement) to a hezb (political party), then the United States should be prepared to reward them with legitimacy. Some recommended steps to progressively legitimize the Houthis could include public statements indicating

the Houthis will be a part of a future Yemeni political settlement; U.S. officials could meet publicly with Houthi leadership in Muscat or Riyadh, if not Sana’a. If Houthis respond positively, the U.S. could conduct a phased reopening of the embassy in Sana’a. Finally, the United States could push for a renegotiated UNSC Resolution 2216 that acknowledges Houthi control in the north.

Page 29

Houthi supporters attending a rally in Sanaa in 2019 Mohammed Huwais/AFP

The “Bloody Nose” approach: Putting U.S. military options on the table

A strategy for the Houthis that does not clearly demonstrate U.S. resolve is likely to fail. Our proposed diplomatic initiatives require U.S. willingness to use military force and coercive pressure if necessary. If the Houthis do not cooperate, the United States must be prepared to consider a wider range of punitive policy options. Otherwise, the Houthis have little incentive to believe the United States is serious about bringing the conflict to an end. There are some military and diplomatic policy options that would apply greater pressure on the Houthis.

Militarily, the United States should be prepared to engage in limited airstrikes against Houthi targets around Marib. This targeted use of force would effectively demonstrate U.S. resolve and represent a significant change in U.S. policy. To address mission creep concerns, this policy should not be sustained if it does not ultimately compel the Houthis to alter their behavior.

Diplomatically, there are several options to apply pressure on the Houthis in the face of intransigence. These actions can be taken in sequence or individually. First, the United States could continue escalating official rhetoric and public censure of Houthi actions. Second, the United States could add more Houthi leaders and personnel to the SDGT list. Third, it could redesignate the Houthis as a FTO. Fourth, it could freeze humanitarian aid. (Although extreme, freezing aid has “gotten the attention” of the Houthis in the past, and it was restarted in exchange for concessions.) 89 As a final measure, the United States could begin formal notification procedures and preparations to temporarily relocate its diplomatic mission in Yemen to Aden.

Taken together, these military and diplomatic policies would provide escalatory policy options to U.S. leaders. These actions should only be taken in a calculated way to demonstrate U.S. resolve in hastening peace negotiations. If U.S. resolve is questioned, it is unlikely that the Houthis will believe American policy positions or potential “red-lines,” and the conflict will drag on.

Page 30

The United States has a clear national interest in the cessation of hostilities and a stable Yemen. The conflict threatens the stability of our close partner Saudi Arabia. It also has the potential to disrupt global oil supplies and international shipping. The conflict is poised to dramatically increase Iranian influence in the region and provide Iran with a permanent foothold on Saudi Arabia’s border. The instability can also be exploited by terrorist groups who could reconstitute and threaten regional stability. And finally, the conflict has produced one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.

This report provides a roadmap for U.S. policy that focuses on two primary actors—Saudi Arabia and the Houthi coalition—in the Yemen conflict. We did not focus on state-level politics, reflecting America’s limited ability to influence internal Yemeni dynamics. Nevertheless, the United States has an important role to play by virtue of its long-standing relationship with Saudi Arabia.

First, this report recommends strengthening the U.S.-Saudi relationship, which we believe is critical to winding down the fighting and to future negotiations in the Yemen conflict. Second, this report recommends the United States pursue parallel diplomatic tracks with the Houthis and with Saudi Arabia to offer calibrated assurances and guarantees in response to coordinated concessions. Together, these two policy recommendations directly serve U.S. interests in the Gulf region and support progress toward

a peaceful resolution of the Yemen conflict.

It is critical to note this report’s assumptions and scope. This report assumed that Marib had not fallen and that the United States and Saudi Arabia would commit the necessary resources, military or otherwise, to prevent such an outcome. If Marib were to fall, our strategy would need to be revisited and adjusted.

Page 31 6 |

Conclusion

7 | List of Interviews

We are grateful to the diplomats, scholars, analysts, and other professionals who took the time to speak with our policy workshop. They were invaluable and helped inform the perspectives presented in this report. The content of the report does not necessarily reflect their views or the views of their affiliated organizations. Some of those we interviewed from the United Nations, U.S. government, and some foreign governments requested that their names not be included. They are listed below in alphabetical order.

Amb. John Abizaid former U.S. Ambassador to Saudi Arabia and U.S. CENTCOM Commander

Summer Ahmed Southern Transitional Council’s U.S.-based Foreign Relations Representative

Nadwa Al-Dawsari Non-Resident Scholar, Middle East Institute

Mohammed Abdullah Al-Hadrami former Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Yemen

Amb. Prince Turki Al-Faisal Al-Saud former Saudi Ambassador to the United States

Waleed Alhariri U.S. Office Director, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies

Ahmed Atef Counselor, Southern Transitional Council Foreign Affairs Department

Daniel Benaim Deputy Assistant Secretary for Arabian Peninsula Affairs, Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, U.S. Department of State

Marieke Brandt Senior Researcher at Institute for Social Anthropology, Austrian Academy of Sciences

Sana Brosnan Humanitarian Advisor, U.S. Mission to the UN

Casey Coombs Researcher, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies and Independent Journalist

Elana DeLozier Rubin Family Fellow, Washington Institute for Near East Policy

Amb. Gerald Feierstein former U.S. Ambassador to Yemen and Senior Vice President, Middle East Institute

Lise Grande President and CEO, United States Institute of Peace

Bernard Haykel Professor of Near Eastern Studies, Princeton University

Kelsey Hampton Senior Officer, Search for Common Ground

Gregory Johnsen Non-Resident Fellow, Brookings Institute

Page 32

Trevor Keck Deputy Head of Policy and Humanitarian Affairs Advisor, International Committee of the Red Cross

Jacob Kurtzer Senior Fellow, Center for Strategic and International Studies

Amb. Tim Lenderking U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen

Marc Linning Senior Advisor, Center for Civilians in Conflict

Daphne McCurdy Foreign Policy Advisor to Senator Jeff Merkley

Rob McCutcheon Chief of Staff to the U.S. Special Envoy for Yemen

Daniel Mouton Director for Political-Military Affairs (MENA) at National Security Council

Summer Nasser CEO, Yemen Aid

Asher Orkaby Associate research scholar at Princeton University’s Transregional Institute.

Scott Paul Senior Manager for Humanitarian Policy, Oxfam

John Phillips Program Officer for Asia, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, U.S. Department of State

Miles Price Senior Disaster Operations Specialist, United States Agency for International Development

Peter Salisbury Senior Analyst, International Crisis Group.

Jeremy M. Sharp Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs, Congressional Research Service

Rachel Smith-Levy Political Advisor, U.S. Mission to the UN

Amb. Moosa Hamdan Al Tai, Omani Ambassador to the United States

Eric Trager Professional Staff Member, U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee

Amb. Matthew Tueller U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, former U.S. Ambassador to Yemen

Katherine Zimmerman Fellow, American Enterprise Institute

Professional Staff Member U.S. House of Representatives

Former U.S. Ambassador to the United Arab Emirates

Page 33

Workshop Participants

Ambassador Daniel Kurtzer is the S. Daniel Abraham Professor of Middle East Policy Studies at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA). During his twenty-nine-year career in the Foreign Service, he served as the U.S. ambassador to Egypt and Israel.

Jacqueline Baumgartner is a master’s student studying domestic politics at SPIA. Prior to coming to Princeton, she worked for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) for five years in Geneva, Paris, Athens, and Washington, DC, where she was responsible for monitoring the humanitarian consequences of migration. Prior to the ICRC, Jacqueline worked for the American Red Cross National Headquarters and for the International Rescue Committee assisting with refugee resettlement in the United States.

Merlin Boone is a PhD student at SPIA and an active-duty officer in the U.S. Army. Professionally, his experience includes special operations in Syria and throughout the Asia Pacific. Merlin’s research interests include great power competition, economic statecraft, and East Asian security relations. Merlin holds a MA in international affairs from The University of Hong Kong and BS in economics (Honors) and Chinese from West Point.