Nile Waters Conflict: The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs Policy Workshop Report

Fall 2022

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs Policy Workshop Report

Fall 2022

Cover Photo: Building of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in 2019.

(Source: Tiksa Negeri/File Photo/Reuters)

Cover Photo: Building of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in 2019.

(Source: Tiksa Negeri/File Photo/Reuters)

Nile Waters Conflict: The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

Policy Workshop Report

Fall 2022

Faculty Advisor

Ambassador Daniel C. Kurtzer

S. Daniel Abraham Professor of Middle East Policy Studies

Authors

Harrison Fuller • Julia A. Herrle • Samantha Libraty • Jared A. Lockwood • Matthew D. Lillehaugen • Jessica Moore • Andrew Olivieri • Adam H. Sigelman • Ashley M. Stracke

The Blue Nile Falls, Ethiopia. (Source: CNN/Deagostini/ Getty Images)

The Blue Nile Falls, Ethiopia. (Source: CNN/Deagostini/ Getty Images)

Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgments .............................................................................. 7 List of Abbreviations ........................................................................... 8 Executive Summary ........................................................................... 9 Background to the Conflict ................................................................. 13 The United States’ Stake in the GERD Dispute ................................. 19 Conflict Parties: Narratives, Positions, Interests ................................ 22 Barriers to an Agreement ................................................................... 34 Recommendations ............................................................................. 39 Potential Spoilers / Considerations .................................................... 47 Conclusion ......................................................................................... 50 About the Team .................................................................................. 51 Endnotes ............................................................................................ 54

Preface

This report is the final product of a policy workshop sponsored by the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs as part of the Master in Public Affairs degree program. It results from the work of nine graduate students advised by Ambassador (Ret.) Daniel Kurtzer. The students briefed the report’s content to the U.S. Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa on December 21, 2022 and the U.S. National Security Council staff on December 11, 2022.

The report’s information and recommendations stem from months of research and interviews with current and former government officials as well as experts and members of civil society from the United States, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan. The group conducted virtual and in-person interviews in Princeton and Cairo, Egypt. [Note: The group was unable to travel to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, but conducted interviews with lead Ethiopian negotiators virtually and in Cairo.]

Throughout the report, interviewees are referenced according to their preferences, either by name, indirectly by title, or anonymously. This practice allowed interviewees to speak freely. The report does not necessarily reflect the views of any individual author, the workshop director, Princeton University, the U.S. State Department, or any interviewee or their affiliated organization.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the many people who supported us during our workshop. We thank the government officials, researchers, and others who generously lent their time and expertise to us. Their contributions to our understanding of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and its history were invaluable.

We would like to thank Ambassador Daniel Kurtzer for his mentorship and Bernadette Yeager for her support during our workshop. We are also thankful to Dean Amaney Jamal, Associate Dean Karen McGuinness, Laura Kijewski, Ann Lengyel, and everyone else at the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs who helped make this workshop possible.

The authors would like to thank the following people for their contributions:

• American University-Cairo Dean Dr. Noha El-Mikawy and panel of water experts and university students

• Professor Khaled AbuZeid

• Ambassador Seleshi Bekele Awulachew

• Lauren Ploch Blanchard

• Sanda Chao

• Dr. Steven Cook

• William Davison

• Ambassador Mohamed el-Molla

• Jeffrey Feltman

• Julian Hadas

• Ambassador Mike Hammer

• Essam Heggy

• Dr. Mohamed Hela

• Ambassador Hassan Ibrahim Musa

• Abdurehman Jemal

• Kholood Khair

• Ambassador Jessica Lapenn

• Dr. Nadia Makram Ebeid

• Dr. Marwa Mamdouh Sale

• Bethany Milburn

• Dr. Abdel Monem Said Aly

• Dr. Mohamed M. Nour El-Din

• Daniel Paul-Schultz

• Ambassador Geeta Pasi

• Deputy Ambassador Qudsi Rasheed

• Ambassador Daniel Rubinstein

• Dr. Salman M.A. Salman

• Dr. Aaron Salzberg

• Dr. Mohamed Sameh Amr

• Ambassador David Satterfield

• Atef Sayed

• Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry

• Ms. Susan Stigant

• Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation Dr. Hany Swailem

• Lara Talverdian

• The Egyptian GERD Negotiating team

- 7 -

List of Abbreviations

AU - African Union

BCM - billion cubic meters

CDCS - Country Development Cooperation Strategy

CFA - Cooperative Framework Agreement

DoP - Declaration of Principles

EPRDF - Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front

GERD - Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam

HAD - High Aswan Dam

IMF - International Monetary Fund

IPoE - International Panel of Experts

NBI - Nile Basin Initiative

NISRSG - National Independent Scientific Research Study Group

PRC - People’s Republic of China

TPLF - Tigray People’s Liberation Front

UAE - United Arab Emirates

UN - United Nations

UNEP - United Nations Environment Programme

UNSC - United Nations Security Council

USAID - United States Agency for International Development

USBR - United States Bureau of Reclamation

USDA - United States Department of Agriculture

USIP - United States Institute of Peace

- 8 -

Executive Summary

For over a decade, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan have engaged in a dispute over Ethiopia’s building of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), the largest dam in Africa and one of the largest in the world. Given Egypt’s reliance on the Nile River for 92 percent of its water; Ethiopia’s need to develop its economy and support its growing population; and Sudan’s agricultural, water security, and development needs; the GERD has become a thorny political issue that has poisoned relations among the three countries and risks drawing the region into prolonged conflict. Due to competing urgent regional priorities and the difficulty of achieving a negotiated GERD agreement, the United States and others in the international community may be tempted to put this dispute on the backburner. However, if the conflict intensifies, which could be sparked by prolonged drought, increasing water demands, or the construction of additional upstream dams, the consequences could be catastrophic.

In order to promote peace and stability in the region, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) dispute should remain a high priority of the United States and the international community. While ideally Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan should enter into a formal agreement that would include drought mitigation measures, an information sharing process, and a conflict resolution mechanism,

Fishermen on the Nile in Egypt. (Source: The New York Times)

Fishermen on the Nile in Egypt. (Source: The New York Times)

the current political context and barriers make achieving a legally binding agreement unlikely in the near term. For these reasons, the Princeton Nile Waters Policy Workshop Team recommends the following steps to make progress on issues related to the GERD dispute until a formal agreement can be adopted:

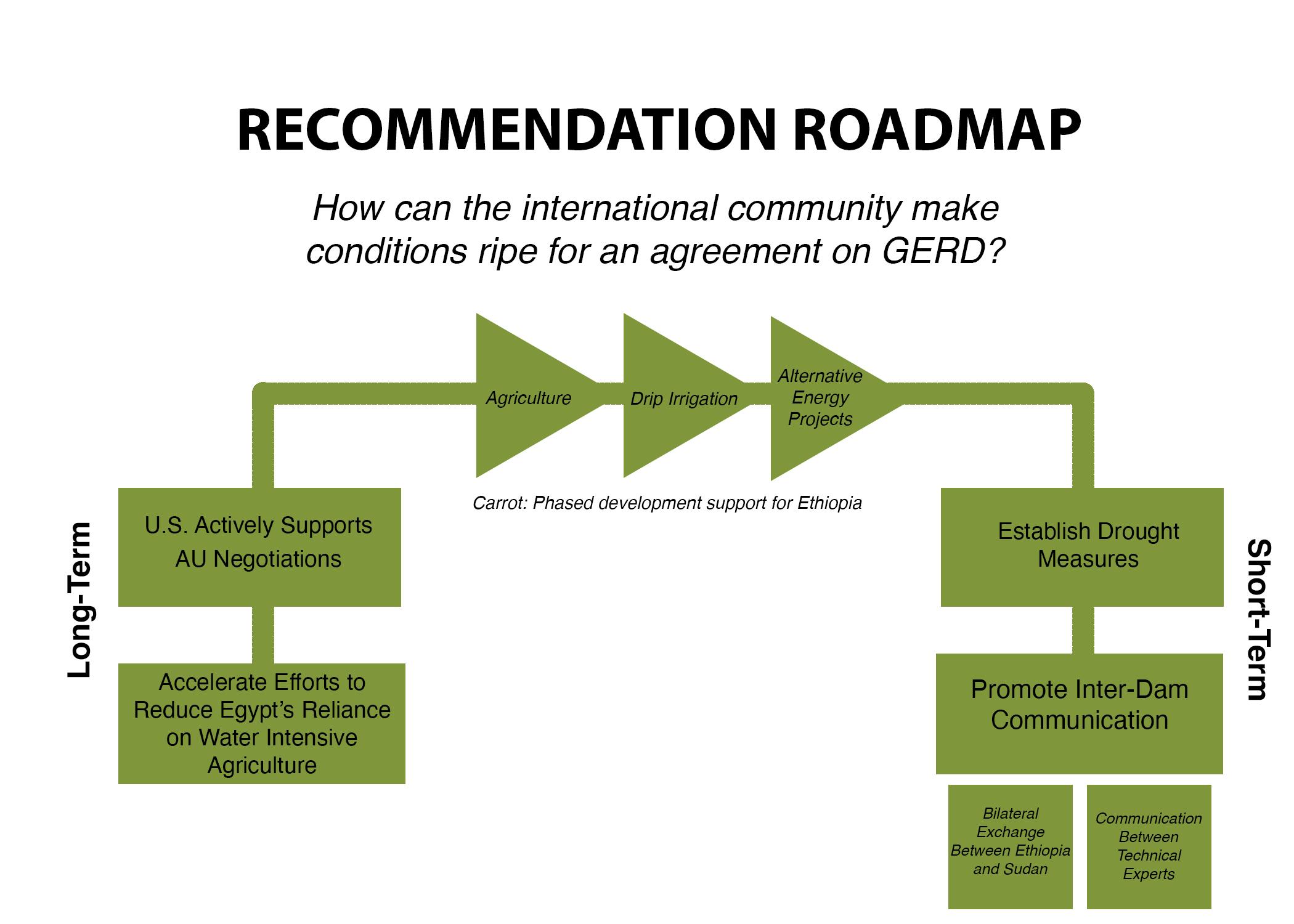

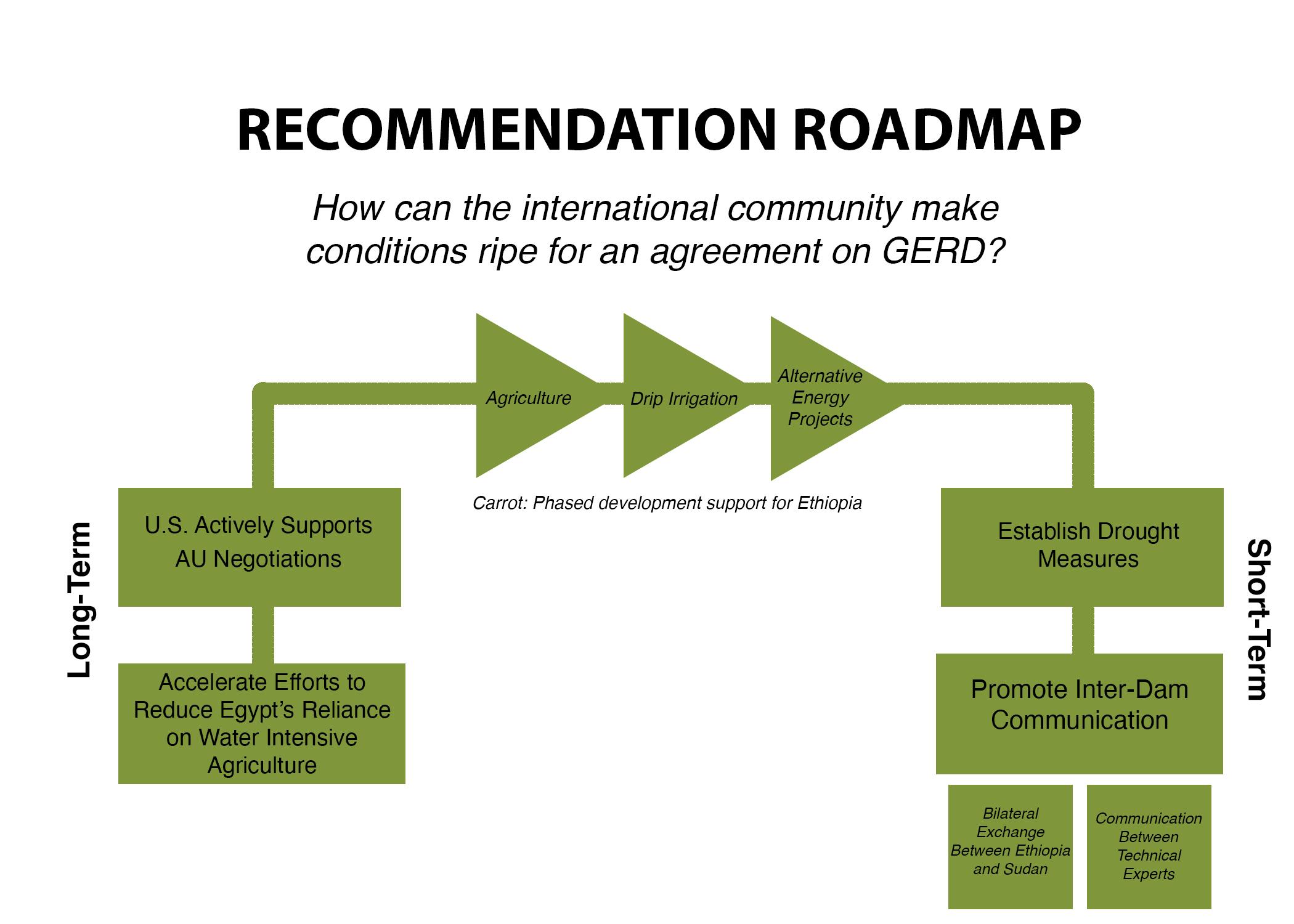

• Establish drought management measures. We recommend that Egypt and Ethiopia develop a plan for drought management measures as an intermediate step to reduce tensions between the two parties and address the significant risk posed by sustained periods of drought. Instead of engaging in a formal negotiation process, the United States and international community could encourage Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia to exchange information via diplomatic notes as part of a coordinated planning process to address different drought scenarios. These notes could include a plan for cooperation during a drought along with each country’s domestic plans to reduce long term water consumption.

• Promote inter-dam communication. Based on conversations with various stakeholders and the flooding that took place in Sudan in 2020, we believe there is currently insufficient coordination among the three countries in their inter-dam operations. The United States should focus on establishing regular, consistent, and mutually agreed upon inter-dam communication as the most immediate action. Inter-dam communication could be achieved by encouraging Sudan and Ethiopia to establish a committee, through which Sudan could then coordinate separately with Egypt. Alternatively, the United States could encourage direct communications between the technical experts of all three countries, who appear to be closer in agreement than their political counterparts. Communication could be as simple as implementing a technical and apolitical website that would allow each of the parties to regularly publish and glean helpful information to improve the operations of their own dams.

• Support AU-led negotiations. The African Union (AU) continues to be the best forum to secure some level of buy-in from the three main parties as well as other riparian states, given its status as a pan-African organization that has acted as a mediator in other disputes on the continent and given that the 2019-2020 Washington Process produced terms that were highly favorable to the Egyptian position, making direct U.S. mediation a difficult sell. Moreover, given that Ethiopia stands to benefit most from the status quo, choosing to support its preferred mediator may be the only way to get the country back to the table. External partners, especially those on the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) — the UK, France, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) — should provide the AU with support during the negotiations.

• Accelerate efforts to reduce Egypt’s reliance on water-intensive agriculture. To promote greater water use efficiency and water security in Egypt, the United States should step up its efforts to encourage Egypt to reduce its demand for water in parallel with its efforts to resolve the GERD dispute. This includes encouraging Egypt to transition away from crops like cotton and rice, which require large amounts of water, and to less water-intensive crops, such as wheat. In the long run, the United States could help the Egyptian economy diversify away from the agricultural sector with the support of USAID.

- 10 -

• Bring Ethiopia to the table by supporting the country’s development. It is important that the United States and international community reopen Ethiopia’s access to capital in a phased approach that incentivizes the government to engage seriously in GERD negotiations and creates stronger linkages based on mutual benefit among all parties. The United States should help revive Egyptian private sector investment in Ethiopia, which had been partly disrupted by the internal conflict, and provide funds for small-scale alternative energy projects to help provide access to electricity to rural communities. Alternatively, the United States may want to consider support for future projects along the Nile in exchange for meeting measurable milestones toward a comprehensive agreement with Egypt, Sudan, and other riparian countries where appropriate.

Successful U.S. engagement on the GERD would provide benefits to millions of Africans across the Nile basin. It would reduce the risk of escalation of conflict between Ethiopia and Egypt, promote regional cooperation, contribute to Ethiopia’s and Sudan’s development goals, and strengthen U.S. ties and influence in the region. Moreover, it would reduce the risk of escalation in a conflict that could destabilize the region and have devastating humanitarian impacts. Despite the significant challenges to reaching a comprehensive agreement, the United States should continue to support the parties in pursuing a long term, formal resolution to this dispute; simultaneously, the United States should take immediate steps to promote cooperation among the parties on key intermediate issues and to increase the efficiency of their water usage and their resilience to drought.

- 11 -

An Ethiopian farmer works with wind turbines behind him. Financial support for Ethiopian development including alternative energy sources may encourage the Ethiopian government to enter into an agreement with Egypt and Sudan on the GERD. (Source: CNN/ AFP/Getty Images)

- 12 -

Map of The Blue Nile and Nile River (Source: Research Gate, Dr. Yohannes Yihdego Woldeyohannes)

Background to the Conflict

The Nile River is the longest river in the world and passes through eleven countries. The Blue Nile, the largest contributing tributary of the Nile, starts in Lake Tana in Ethiopia and merges with the White Nile - the Nile’s second largest tributary by volume - in Sudan before continuing on to Egypt and exiting into the Mediterranean Sea. Given the region’s arid climate, the inhabitants of the Nile River Basin have sought to control the river’s waters throughout history.1 These conflicts date back centuries: some scholars suggest that Ethiopian emperors have used the Nile as a coercive diplomatic tool against Egypt since as early as a thousand years ago.2

When the British colonized Egypt in the late 1800s, they signed various treaties concerning uses of the Nile and pursued a range of tactics to protect their interests in Egyptian agriculture.3 These tactics included support for Italy’s efforts to colonize Ethiopia.4 In 1929, Egypt and Britain entered into the “Nile Waters Agreement,” a treaty in which other riparian countries would need to obtain permission from Egypt before pursuing any projects or efforts that would impact the volume of Nile water flowing into Egypt’s water share.5 In 1959, Egypt and Sudan entered into an agreement that claimed rights over the entirety of the Nile. The 1959 treaty asserted that Egypt and Sudan would “jointly consider and reach one unified view” regarding any other riparian state’s “claim [of] a share in the Nile waters.”6

In 1999, the Nile Basin Initiative (NBI) was launched to “achieve sustainable socio-economic development through equitable utilization of, and benefit from, the common Nile Basin water resources.”7 By 2011, six of the Nile Basin countries, including Ethiopia, signed the Nile Basin Cooperative Framework Agreement (CFA, also known as the Entebbe Agreement), a proposed agreement that would establish legally-binding principles, rights, and obligations regarding uses of the Nile River. The CFA does not attempt to quantify the water rights of Nile Basin states, though its principle of “equitable and reasonable utilization” would entail a near-certain reduction of the shares claimed by Egypt and Sudan in their 1929 and 1959 agreements. Consequently, Egypt and Sudan have rejected joining the CFA.8 The CFA requires six ratifications to enter into force; to date, only Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda have ratified the treaty.

- 13 -

Egyptian dock workers load cotton onto boats in 1922. (Source: The New Yorker/National Geographic Image Collection/Alamy)

Against this historical backdrop, Ethiopia’s then Prime Minister Meles Zenawi decided to operationalize plans for a Blue Nile dam, which was originally proposed for construction in the 1950s and 1960s by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR).9 Work on the dam began quietly in 2010.10 In 2011, Prime Minister Meles officially announced the multibillion-dollar Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), originally christened the Grand Millennium Dam. The GERD, which will be the largest hydropower dam in Africa once fully operational, is a critical part of Ethiopia’s plans to modernize and become a regional economic power. The expansion of transmission lines associated with the GERD is expected to facilitate energy exports to neighboring countries and provide 65 million Ethiopians with access to affordable energy.11 In order to reach its full power-generation capacity, the GERD reservoir must remain filled at or above a certain level at all times.

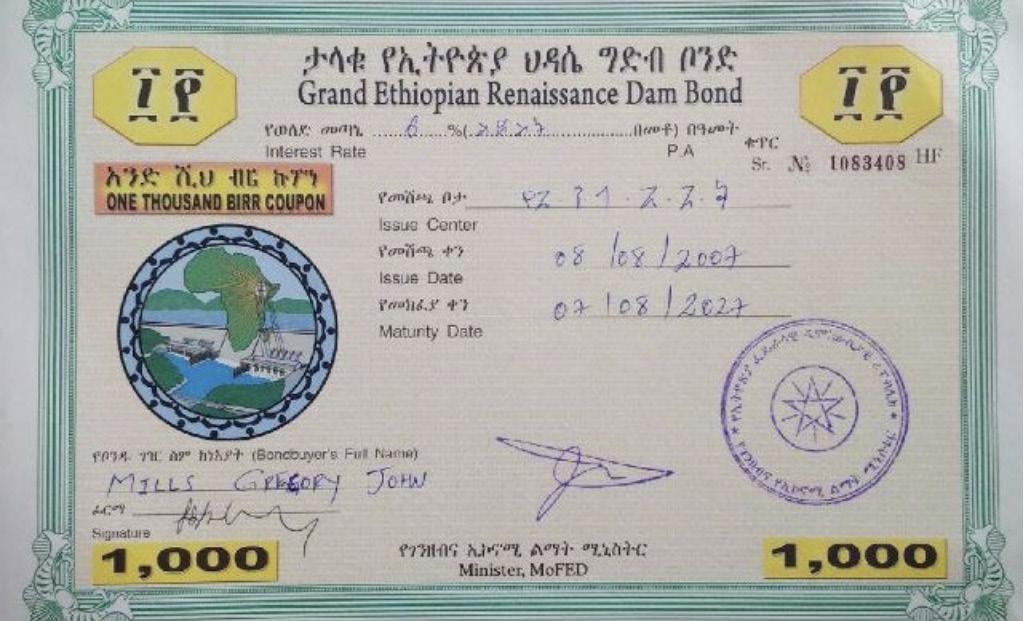

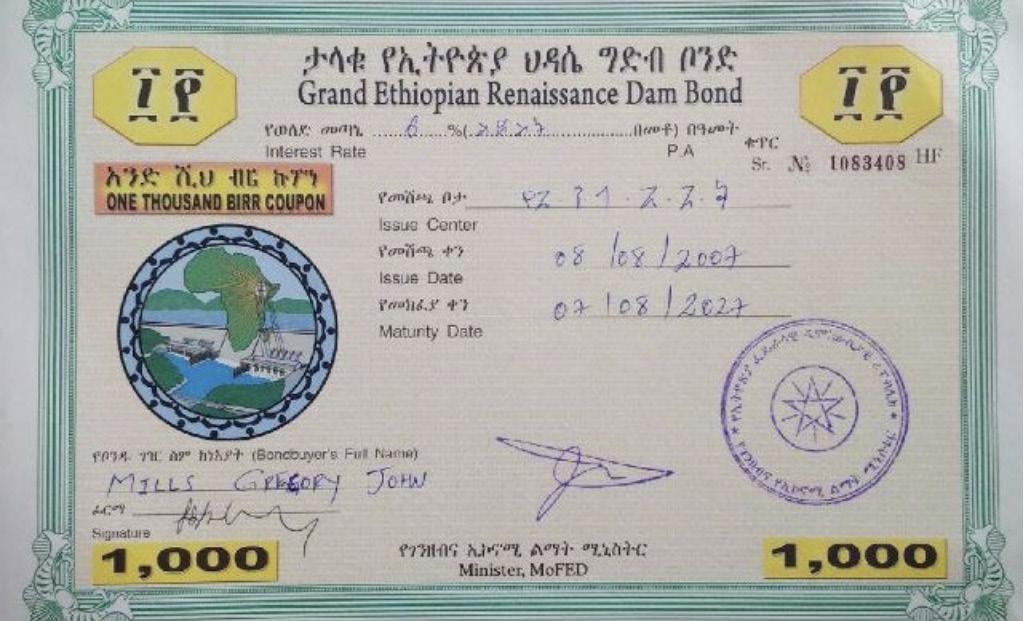

Due to constraints in access to credit through international financial institutions, Ethiopia raised significant funds for the dam via domestic bonds and voluntary contributions. Ethiopian leaders blame Egypt for their inability to raise international funds for the GERD, alleging that Egypt pressured the United States to block World Bank or other funding for the project due to the lack of a water sharing agreement between the two African countries.

The announcement of the GERD, which is located 20 miles away from Ethiopia’s border with Sudan, surprised both Egypt and Sudan. The announcement also coincided with the Arab Spring in Egypt, which resulted in the removal of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak from office. Egyptian officials later speculated that Ethiopia purposely moved forward with construction during a time when Egypt was vulnerable.12

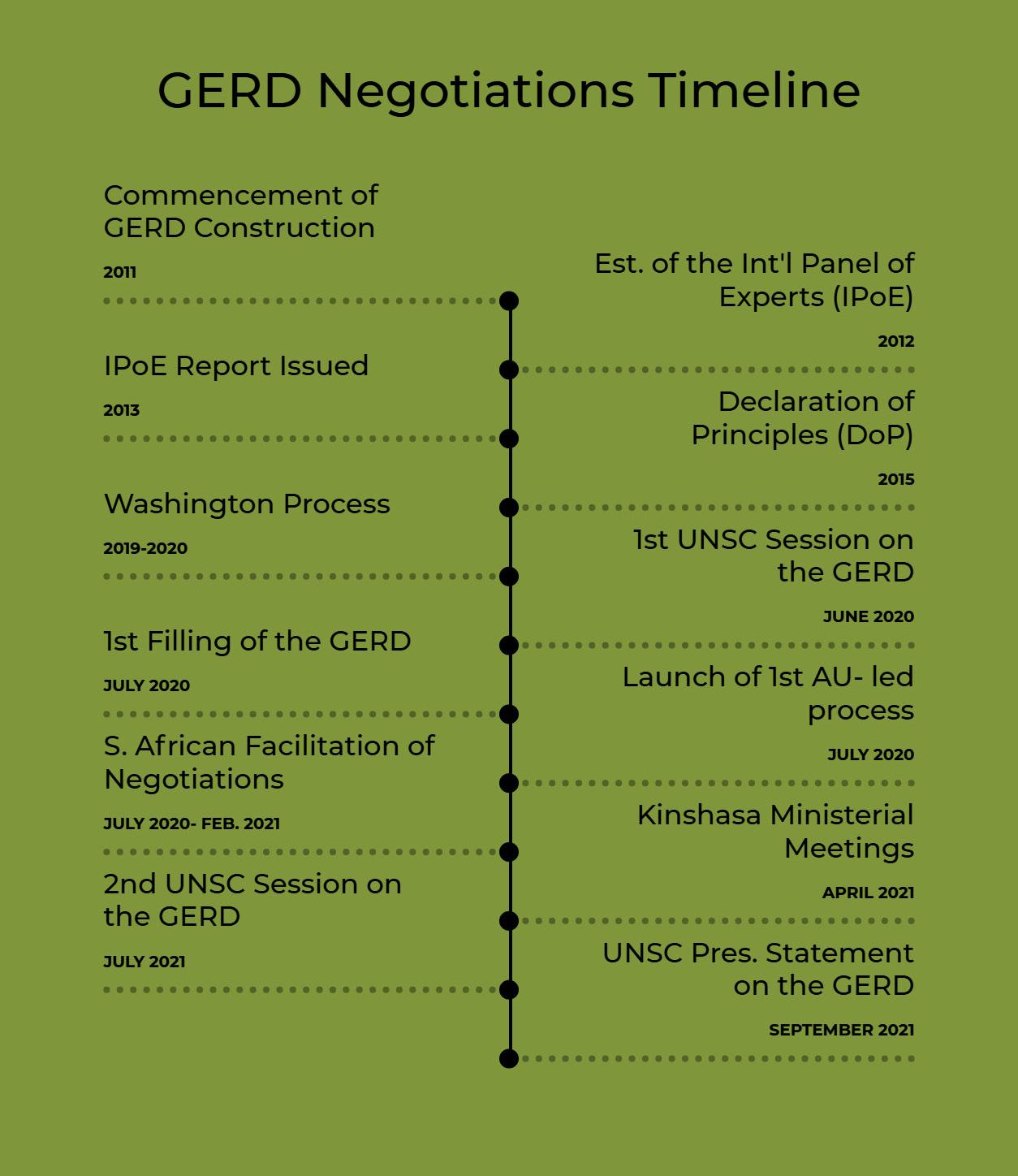

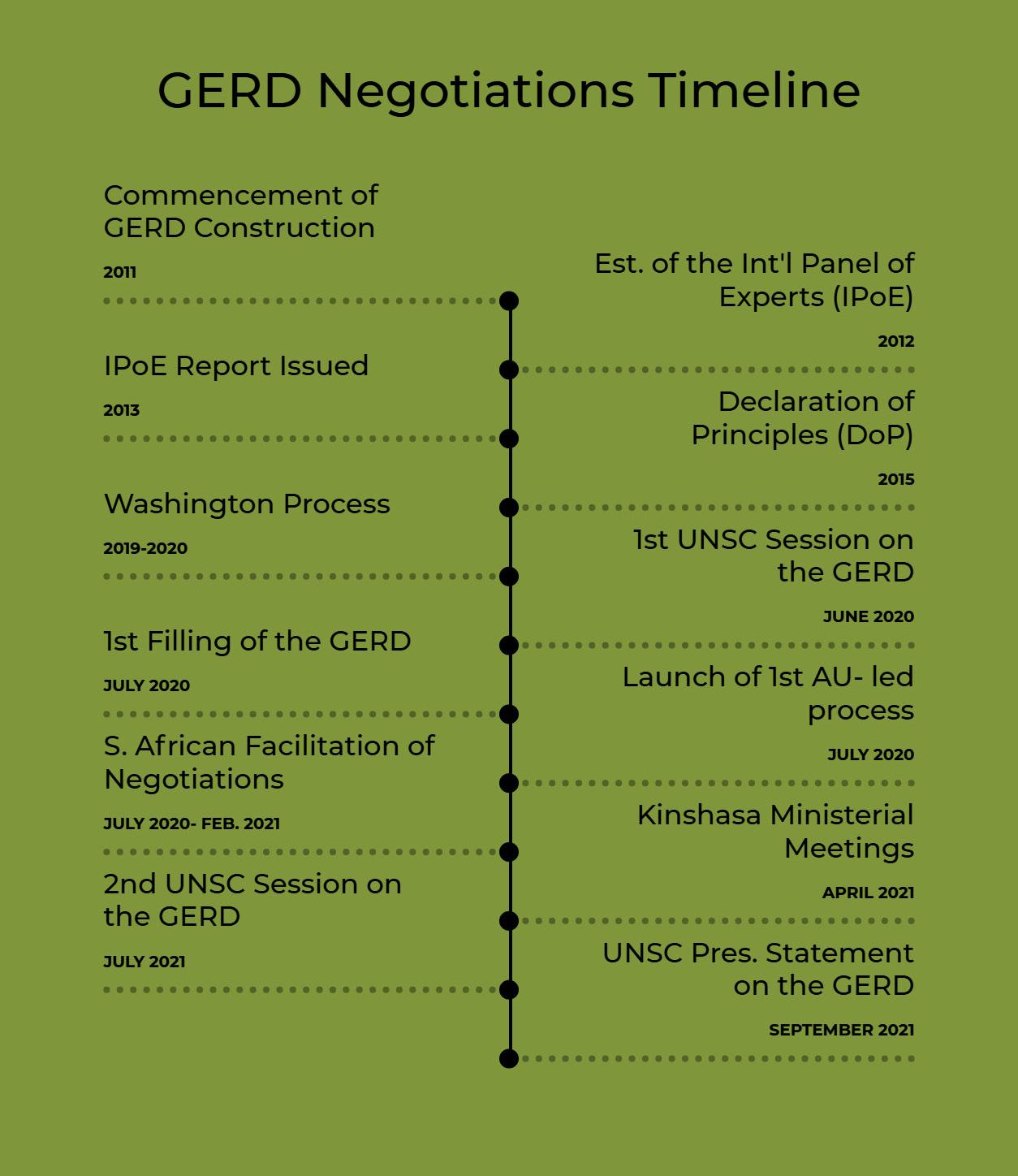

In 2012, Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia formed a 10-member International Panel of Experts (IPoE) to assess the construction of the GERD and its impact on downstream neighbors.13 The report was not publicly released, and all three parties interpreted its findings differently. Ethiopia believed the report “showed the dam offers high benefit for all three countries,” while Egypt argued the report called for additional environmental and social impact assessments.14 Despite Egypt’s calls

- 14 -

Ethiopian Blue Nile Diversion Ceremony in 2013. (Source: Al-MonitorAFP/Getty Images)

for a halt to dam construction, Ethiopia began to divert the flow of the Blue Nile in order to build the GERD, again surprising Egypt and Sudan. Ethiopia’s diversion of the flow of the river further escalated tensions between Egypt and Ethiopia.15

Despite these rising tensions, a breakthrough came in 2015 in the form of the Declaration of Principles (DoP). The DoP, which was signed by all three parties, was seen as a preliminary step to solving the dispute by outlining the following ten principles: the need for cooperation; development and regional integration; avoidance of significant harm to riparian countries; equitable and reasonable use; implementation of the IPoE’s recommendations on the filling, operations, and safety measures of GERD; confidence building; information exchange; respect for sovereignty; and peaceful settlement of disputes.16 Although the declaration called for further studies to be completed in fifteen months, Ethiopia refused to pause construction.17 When BRLi, the French firm that conducted the study, completed its report in 2017, both Sudan and Ethiopia expressed reservations over the legitimacy of the findings on the economic, social, and environmental impacts of the GERD.18 By the end of 2017, Ethiopia had completed at least fifty percent of the construction of the dam.

In 2019, the United States hosted Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan in Washington to set a timeline for four rounds of meetings to resolve outstanding issues on filling and operating the GERD. Ethiopia withdrew from the final meeting in early 2020 citing dissatisfaction with the negotiation process, prompting the United States to finish hosting the talks with just Egypt and Sudan. At the conclusion of the negotiations, Sudan declined to formally consent to the text, leaving Egypt as the only signatory.19 These talks, known as “the Washington Process,” have implications for Ethiopia, Sudan, and Egypt’s perceptions of the United States’ future role in resolving the dispute, described in the Box below.

Still without an agreement, Egypt requested that the Arab League support Egypt and Sudan in the dispute, but Sudan did not agree to the resolution in front of the Arab League for fear that doing so would damage its relationship with Ethiopia. Ethiopia offered a partial agreement to Egypt and Sudan to cover the initial filling terms, since the rainy season presented an opportunity for Ethiopia to fill the GERD. Egypt and Sudan, however, rejected the Ethiopian proposal.

In May 2020, Egypt submitted a 17-page letter to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) protesting Ethiopia’s actions and demanding a halt to GERD construction until an agreement was signed. In its own letter to the UNSC, Ethiopia responded that it did not have to seek Egyptian approval for GERD construction and blamed Cairo for the failure of previous negotiations. While Ethiopia decided to move ahead with the dam, Egypt again requested United Nations (UN) intervention, citing a threat to international peace and security.20 However, the Security Council demurred on the Egyptian request, preferring for the dispute to continue to be handled by a regional body such as the African Union.

The African Union took up the role of mediator in July 2020, when Sudan, Egypt, and Ethiopia agreed to resume talks under African Union (AU) leadership. These negotiations took place during

- 15 -

the same month that Ethiopia began its first filling of the reservoir. Observers from the European Union and United States as well as legal and technical experts attended the talks and expressed hope that they would result in a negotiated settlement. Reports noted progress, indicating that the AU’s “involvement [had]...halted a regional axis formation and eased the pressure on regional states to choose sides.”21 Ultimately, the talks did not satisfy the demands of the three parties. Egypt wanted assurances that it would receive sufficient flow of water in the case of a drought, Sudan wanted a binding agreement for resolving future disputes, and Ethiopia wanted a guarantee of their sovereign ability to fill the GERD without intervention; no party was willing to make the requested concessions to the others.

By mid-2021, Ethiopia decided to move forward with the second filling of the GERD despite the lack of a comprehensive agreement. AU-led talks again failed to reach a negotiated settlement on the filling after Ethiopia rejected the timeframe outlined. Egypt then brought the issue back to the UNSC in July 2021. After a draft resolution put forth by Tunisia failed to garner sufficient support, the UNSC issued a presidential statement “encouraging” the parties to resume AU-led negotiations.

Egypt continues to raise the issue of the GERD at the UN, in its bilateral meetings, and in other international fora. In the meantime, Ethiopia continues to fill the GERD reservoir without an agreement in place.22

- 16 -

A worker overlooks the GERD as it is being built. (Source: Aljazeera/AFP)

- 17 -

Instability in Ethiopia

The War in Tigray started in November 2020 when Ethiopian President Abiy Ahmed launched what he called the “Mekelle Offensive” in response to alleged attacks carried out by security forces loyal to the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the former ruling party of Ethiopia, against federal military bases in Tigray.23 The civil war has displaced over five million people internally and forced millions more into neighboring Sudan.24 The U.S. government has criticized the Ethiopian government for blocking food, water, and medical aid from entering the Tigray region and pointed to credible reports of ethnic cleansing and other human rights abuses being committed against Tigrayan civilians by government-aligned Eritrean and Amharan forces.25 26 There have also been unverified reports of Egypt and Sudan providing military support to the TPLF, which some experts and officials claim has further complicated efforts to achieve a diplomatic solution to the GERD dispute. On November 2, 2022, the Ethiopian Government and TPLF leaders signed a peace agreement that called for the “immediate and permanent cessation of hostilities,” aid and reconstruction, and access to humanitarian assistance.27 On November 15, 2022, humanitarian assistance began arriving in Tigray.28

While the peace accord is promising, the agreement is still nascent. It is critical that the United States and the international community remain focused on helping Ethiopia carry out its commitments, which means there may be little bandwidth within the Ethiopian government to focus on a meaningful resolution to the GERD dispute. However, given Egypt and Sudan’s alleged role in the conflict, a resolution on the GERD may help lower tension in the region.

- 18 -

Relief distribution in Debark, Ethiopia. (Source: The Independent/Getty Images)

The United States’ Stake in the GERD Dispute

Currently, Ethiopia is operating the GERD with no agreement and limited coordination with Sudan and Egypt. However, the disagreement over the GERD will continue to plague relations in the Horn of Africa and could lead to a broader conflict. According to climate models, the Nile’s flow will be more variable in the future, while demand for water in the region is growing.29 The most concerning scenarios involve long periods of extreme drought.

While all sides have publicly stated a desire to avoid conflict, a few warning signs indicate that military escalation is not entirely off the table. Egyptian journalist and researcher Mohammad Maher argues that the combination of Egypt and Sudan’s diplomatic escalation in the lead up to the second filling, Egypt’s military alliances with Ethiopia’s neighbors, and Sudan and Ethiopia’s military clashes on their shared border may lead to conflict, especially given Egypt’s “history of responding to perceived threats to the Nile with force.” He cites an event in the mid-1970s in which the Egyptians reportedly blew up a shipment of equipment for an Ethiopian dam.30 Leaked statements by Egyptian officials indicate they also contemplated using military force against the dam. In 2010, WikiLeaks published emails from a high-level Egyptian official who wrote, “We are discussing military cooperation with Sudan…If it comes to a crisis, we will send a jet to bomb the dam…or we can send our special forces in to block/sabotage the dam.”31 In June 2013, a live broadcast showed Egyptian parliamentarians debating dispatching spies to sabotage the dam or funding Ethiopian rebels to attack the government.32 This rhetoric has continued in more recent years. In June 2021, Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry announced that “all options are on the table to deal with the GERD.”33 Although Shoukry later clarified that his statement did not refer to military options, experts argued that he could have been referencing an Egyptian airstrike.34

If an armed conflict were to take place, it would have significant regional impacts. Attempts by the main parties to form alliances with other riparians such as South Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, and Eritrea to exert pressure during CFA negotiations as well as Nile Basin countries’ involvement in each others’ diplomatic and security affairs may increase the likelihood that an armed confrontation over the GERD would become regional.35 A regional conflict would harm U.S. interests by causing instability that terrorist groups could exploit, disrupting trade and shipping patterns in the Red Sea, and creating humanitarian crises. In fact, the U.S. Institute of Peace reported that, given the enormous populations of Ethiopia and Sudan, the failure of either of these states would create the largest humanitarian crisis in modern history.36

There is also a general sentiment among some African experts and officials in the region that the United States has not focused enough on Africa. These critics claim the United States has taken a reactive approach to issues in the Horn, focusing mainly on counterterrorism and security issues. Meanwhile, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has become Ethiopia’s largest lender and trading partner.37 38 Furthermore, the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) released a report in 2020

- 19 -

outlining how Middle Eastern countries including Qatar, the UAE, and others have increasingly sought to influence activities in the Horn of Africa. According to the report, rivalries between countries in the Middle East are already causing instability.39 For example, the USIP report stated that “Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces have been deployed to Yemen and to Libya at various points to augment Saudi and Emirati-backed forces.”40 For this reason, the Institute recommends that the United States create a strategy that encompasses both the Horn of Africa and the Middle East.

The United States’ relationships with Egypt and Ethiopia are two of its most important relationships in the region. Egypt is an important partner for maintaining regional stability, countering terrorism, and advancing maritime security goals. Additionally, according to the U.S. Congressional Research Service, Egypt exerts significant regional influence, particularly through its soft power among Arabicspeaking countries and via its leading role in the Arab League.41 Egypt has also served as a strategic partner in promoting peace with Israel, including with the Palestinians.42 On maritime security, Egypt is part of the U.S. Central Command’s Combined Maritime Forces, and Egypt assures U.S. military ships expedited naval access through the Suez Canal.43 In sum, the United States’ strong relationship with Egypt is essential for both trade and military operations on land and at sea. However, the U.S.Egyptian bilateral relationship has suffered in recent years with the United States’ emphasis on democracy and human rights concerns, leading Egypt to diversify military and trade relationships with Russia, the PRC, and European nations. Russia is now one of Egypt’s principal arms suppliers.44 Successful U.S. involvement in the GERD dispute could help rebuild the U.S. relationship with Egypt, while an unsuccessful strategy could push Egypt further toward Russia and the PRC.

The United States’ main interests related to Ethiopia include regional stability, economic development, and countering Russian and PRC influence. According to Lauren Blanchard of the Congressional Research Service, Ethiopia is important due to its “size, susceptibility to food insecurity, and position in a volatile but strategic region.”45 The region itself is strategically important because of the United States’ counterterrorism efforts in the Horn.46 The United States also invests heavily in Ethiopia; in 2021, Ethiopia was the largest recipient of U.S. humanitarian and development assistance, and the United States was Ethiopia’s top humanitarian donor.47

Successful engagement on the GERD could further all these U.S. interests. It would reduce the risk of escalation of conflict between Ethiopia and Egypt, promote regional stability, contribute to Ethiopia’s development goals, and strengthen U.S. ties and influence in the region.

- 20 -

The Washington Process

In November 2019, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi asked former U.S. President Donald Trump to help Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan come to an agreement on the filling of the GERD.48 At the time of the request, Ethiopia had not yet begun filling the reservoir. President Trump appointed Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin to lead the negotiation process. Over the course of three months, Secretary Mnuchin convened meetings with the three countries.49 However, when Ethiopia saw the final text of the proposed agreement, it released a press statement indicating that the country was disappointed with the results of the negotiations and criticized the final text as not accurately reflecting the discussions.50 While Egypt moved forward with signing the agreement, Sudan later decided not to sign it, citing concerns that Ethiopia was not a party.51 Ethiopian officials shared with the Princeton Policy Team that the agreement included language similar to that found in the colonial-era 1929 and 1959 Nile Treaties that excluded Ethiopia.52 Because of how the Washington Process unfolded, Ethiopian experts believe that the United States has lost its credibility as a neutral mediator in future negotiations. However, because President Trump committed to helping Egypt enter into an agreement with Sudan and Ethiopia, Egyptian officials continue to look to the United States for leadership in resolving their concerns on the GERD.53

- 21 -

Former U.S. President Donald Trump shakes hand of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi in 2019.

(Source: U.S. Embassy of Egypt)

Conflict Parties: Narratives, Positions, Interests

Egypt

Since Ethiopia announced the construction of the GERD in 2010, Egypt has insisted the dam’s filling and operation be conducted in coordination with the Egyptian government and guaranteed by a binding agreement. Without this coordination, Egypt has called the GERD an “existential threat” to the country’s water security, food security, and economic growth. In addition to Egypt’s dependence on the Nile, Egypt also believes it has a historical claim to the Nile’s waters given the two colonial-era treaties Egypt signed with Sudan. Egypt has reiterated that it has negotiated with Ethiopia and Sudan in good faith. Egypt preferred the Washington Process over the ongoing AU-led talks due to Egypt’s friendly relationship with the United States and the relatively favorable terms that the Washington Process produced for Cairo.

An Existential Threat

One of the driest countries in the world, Egypt views its water security as necessary for guaranteeing its own food security and achieving sustainable economic growth, particularly through agricultural activity. Egypt depends on the Nile River for 92 percent of its freshwater needs; 85 percent of this freshwater comes from the Blue Nile that originates in Lake Tana in Ethiopia. Given Egypt’s water scarcity, which existed prior to the GERD, the Egyptian government has implemented several water conservation initiatives such as reuse, desalination, and public awareness campaigns.

In addition to its concern over water scarcity, Egypt worries that the unilateral filling and operation of the GERD on the Blue Nile will impact the operations of Egypt’s High Aswan Dam (HAD) located downstream from the GERD. The HAD is Africa’s second most powerful hydroelectric dam, generating 2.1 gigawatts annually.54 To compensate for the lack of rainfall, the HAD supports Egypt’s irrigation scheme, allowing Egypt to produce water-intensive crops in the Nile Valley such as cotton, sugarcane, and rice.55

Egypt also prizes the HAD for its role in controlling flooding in the Nile River Valley. Prior to the construction of the HAD, the valley would experience annual floods during Ethiopia’s and Sudan’s rainy seasons. Although flood control is considered a positive consequence of the HAD, the annual floods were vital to the fertility of the land by carrying sediments downstream. The sedimentation process also protected the delta from coastal erosion. In addition, the floods would flush waste from the delta, improving the quality of water.56 Egypt worries the GERD will exacerbate water quality issues and erosion, in turn further depleting fertile farmland, reducing biodiversity, harming the fishing industry in Lake Nasser, and accelerating the erosion of the Nile Delta. This erosion, according to one Egyptian expert interviewed for this report, could increase the likelihood of blockages in the Suez Canal akin to the Even Given debacle that blocked the waterway for six days in 2021.

- 22 -

For these reasons related to both water quantity and quality, Egypt has argued that coordination between the GERD and the HAD is necessary, particularly in periods of drought. In a June 2021 letter to the UNSC, Egypt warned that the HAD barely has enough water to operate in years of average rainfall due to evaporation losses.57 In the event of a prolonged drought, Egypt estimated that it will face a water shortage of 123 billion cubic meters (BCM) over a period of 20 years, according to simulations based on data from the severe drought during the 1980s and early 1990s.58 The HAD would not be able to operate in this scenario, threatening Egypt’s hydroelectric capacity and agricultural activities. Though these predictions depend on the actual fill rate of the GERD reservoir and potential impacts of climate change, even Ethiopia’s own projections show that hydroelectric output at the HAD may decrease by up to 25 percent during years of average rainfall due to the GERD.59

The combined fear of poor management of the GERD and a prolonged drought is the crux of Egypt’s existential crisis. According to Egyptian analyses, the socioeconomic cost of a prolonged drought would equate to 290,000 Egyptians with lost incomes, 130,000 hectares of uncultivated land, $150 million in increased food imports, and $430 million less in agricultural production.60 The government fears this doomsday scenario would result in a host of social problems including increased poverty, rising social tensions, deteriorating health conditions, and migration.61 Consequently, high-level Egyptian officials have considered the GERD’s perceived threat to Egypt’s water security as tantamount to a threat to the country’s national security.

- 23 -

An Egyptian farmer stands in his rice paddy fields. (Source: Reuters)

Cultural Importance and Historical Rights

Not only do Egyptians view the Nile as vital to their water security, they also consider it a critical aspect of their national and cultural identity. Egyptians quote Aristotle’s adage that “Egypt is the gift of the Nile” and Herodotus’ proclamation that “Egypt is the Nile, and the Nile is Egypt.”62 They speak of their ownership of the Nile waters in terms of 4,000 years of history dating back to biblical times. In Egyptian media, Egyptian leaders speak in terms of Egypt’s “God-given” or “historical”63 rights as the “stewards”64 of the Nile waters, giving them a greater claim to the river compared to upstream riparian states.65 Egypt justifies its present claims of historical rights to the Nile by pointing to the 1929 and 1959 treaties.

“Good Faith” Actor

Egypt feels it has made earnest attempts via multiple channels and mediators to come to a negotiated agreement over the GERD with Ethiopia. Egyptian officials blame Ethiopia for the failure of past negotiations and question whether Ethiopia is stalling intentionally to gain time to build and fill the dam. Egypt has also expressed interest in a formal information-sharing mechanism to allow Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan to coordinate the operations of the GERD and the HAD.66 Ethiopia, in turn, says it would only enter into such an agreement if Egypt shares HAD data reciprocally, which Egypt considers unnecessary since the HAD is located downstream from the GERD.

Ultimately, Egypt has invested significant time in these talks and blames their failure on the Ethiopians’ lack of political will. The Egyptian government fears that although Ethiopia continues to engage in negotiations, it has only proven it will continue to act unilaterally until the GERD is completed and functioning. Egypt fears this will set a precedent for future projects Ethiopia has planned on the Blue Nile, some of which may be consumptive dams with the potential to prevent more water from reaching Egypt.

- 24 -

A model of an Egyptian sporting boat (ca. 1981–1975 B.C.). Egyptian nobility would enjoy hunting excursions along the Nile. (Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Catastrophic Dam Failure

In July 2022, an Egyptian professor of engineering hydrology published Google Maps imagery showing what appeared to be cracks in the GERD saddle dam, causing alarm that the saddle dam could collapse and raising questions about the quality of its construction. Failure of the saddle dam could lead to a sudden outpouring of more than 50 BCM of water from the GERD reservoir, resulting in catastrophic flooding in Sudan and an immense human and economic toll.67 However, technical experts assert that the probability of a catastrophic dam failure is very low

Ethiopia

To Ethiopia, the GERD is a responsible infrastructure project that is necessary to develop the country’s economy and improve the livelihoods of its people. The government has rejected demands for a binding agreement on the coordinated use of the dam, viewing those demands as attempts by Egypt to control Ethiopia’s sovereign decision making processes. Despite Ethiopia’s intentions to fill and operate the dam unilaterally, the government has referred to the GERD as “a site of cooperation” in official documents and touts the benefits it will have for other African countries. These benefits include reduced flooding in Sudan and energy exports for its African neighbors. To date, Ethiopia has completed its third filling of the dam and inaugurated the use of its second turbine in August 2022.

The Key to Ethiopian Development

Despite boasting one of the fastest growing economies between 2005 and 2015, Ethiopia is still considered one of the poorest countries in the world given its per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $944.68 As of 2021, Ethiopia also held a national debt equal to 52.95 percent of its GDP.69 In addition to its outstanding debt, the Ethiopian government relies heavily on foreign assistance and direct investment. In 2020, the World Bank reported that Ethiopia received $5.3 billion in foreign assistance.70 Ethiopian leaders have viewed this reliance on foreign assistance as a national security threat and a point of “national disgrace.”71 Projects like the GERD, Ethiopian officials say, are necessary to propel the country forward on a path of economic self-sufficiency

In addition, Ethiopia continues to struggle with key development challenges, including low levels of human capital and high levels of food insecurity. The conflict between the government and the TPLF has exacerbated these conditions by causing internal displacement and damaging crucial infrastructure in the country’s north. In this difficult climate, the private sector has not been able to grow or create jobs. There are concerns the labor market, which is already struggling to employ the country’s young population, will be unable to absorb the country’s conflict-displaced workers.72

The Ethiopian government has described the GERD as an answer to these challenges. In the short term, the construction of the dam will stimulate the economy by creating an expected 12,000 jobs.73 Once fully operational, the electricity generated by the dam will provide access to 60 million

- 25 -

Ethiopians. Consequently, Ethiopia remains focused on completing the GERD and planning for eventual export of electricity, which is “expected to secure hard currency” for subsequent infrastructure projects.74

Despite boasting one of the fastest growing economies between 2005 and 2015, Ethiopia is still considered one of the poorest countries in the world given its per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of $944.75 As of 2021, Ethiopia also held a national debt equal to 52.95 percent of its GDP.76 In addition to its outstanding debt, the Ethiopian government relies heavily on foreign assistance and direct investment. In 2020, the World Bank reported that Ethiopia received $5.3 billion in foreign assistance.77 Ethiopian leaders have viewed this reliance on foreign assistance as a national security threat and a point of “national disgrace.”78 Projects like the GERD, Ethiopian officials say, are necessary to propel the country forward on a path of economic self-sufficiency.

In addition, Ethiopia continues to struggle with key development challenges, including low levels of human capital and high levels of food insecurity. The conflict between the government and the TPLF has exacerbated these conditions by causing internal displacement and damaging crucial infrastructure in the country’s north. In this difficult climate, the private sector has not been able to grow or create jobs. There are concerns the labor market, which is already struggling to employ the country’s young population, will be unable to absorb the country’s conflict-displaced workers.79

The Ethiopian government has described the GERD as an answer to these challenges. In the short term, the construction of the dam will stimulate the economy by creating an expected 12,000 jobs.80 Once fully operational, the electricity generated by the dam will provide access to 60 million Ethiopians. Consequently, Ethiopia remains focused on completing the GERD and planning for

- 26 -

Ethiopian coffee farms. Coffee is a top export of the country. (Source: NPR/The Royal Botanical Gardens)

eventual export of electricity, which is “expected to secure hard currency” for subsequent infrastructure projects.81

Finally, the GERD remains but one part of Ethiopia’s development plan for the Blue Nile. Ethiopia has long understood the untapped potential of the Blue Nile and the role it could play in its country’s development. In 1964, the Ethiopian government invited the USBR to assess the Blue Nile and identify potential projects, including dams for both irrigation and hydroelectric power. Ultimately, USBR proposed four sites for dams on the Blue Nile and Atbara Rivers, including the site where the GERD is being built. Ethiopians see the GERD as the first of multiple steps tapping into the potential of the Blue Nile.

A National Symbol

Ethiopia has been embroiled in political instability in the last decade largely due to the country’s ethnic, linguistic, religious, and cultural differences. There are over 80 different ethnic groups in Ethiopia, and only a minority of Ethiopians speak the official language, Amharic.82

To address these tensions, the Ethiopian government ratified a new constitution in 1994 that established a federal system with eleven states drawn largely along ethnic lines.83 However, many Ethiopians claimed the borders were ill-defined, and various ethnic groups remained skeptical of the central government. The Ethiopian constitution also provides each state the power to secede.84 For these reasons, maintaining the unity of the Ethiopian state has not been an easy task. Led by the Tigrayans, the four-party coalition

- 27 -

“We have finished with the syndrome of dependence.”

– Zadig Abraha, Deputy-Head of GERD Coordination 92

A GERD Bond. (Source: The Brenthurst Foundation/Greg Mills)

government that drew up Ethiopia’s 1994 constitution remained in power for nearly 30 years. To maintain unity, the central government focused on infrastructure projects to connect the country’s states including roads, railways, and telecommunications.85 It was this investment that helped grow Ethiopia’s economy between 2005 and 2015.86 However, this growth did little to reduce ethnic tensions. Resentment towards the Tigrayans, who represented only 5.7 percent of the population, resulted in protests starting in 2010. In 2018, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn stepped down and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was appointed by the coalition to fill the role.87 While Prime Minister Abiy was re-elected in June 2021 for another five-year term, his position remained dependent on the support of the coalition government.88 Amidst this backdrop, Prime Minister Abiy has continued to promote large-scale infrastructure projects like the GERD to distract from internal tensions, including the conflict with the TPLF that began in 2020.

In the media, which has become increasingly polarized, the GERD remains a symbol of national pride, partly due to the belief that it was financed by the Ethiopian people.89 Because of the lack of external financing, the government deducted money from the paychecks of civil servants, issued bonds, ran lotteries, and undertook other efforts to mobilize national support for the project.90 While there is some disagreement about whether the entire $4-billion project was publicly financed, it has become a point of prestige for all Ethiopians. “There is only one thing that brings all Ethiopians together, and that’s the GERD,” according to one former U.S. official who worked in Ethiopia.91

- 28 -

A member of the Ethiopian Republic Band awaiting a performance at the GERD (Source: Al-Jazeera/Amanuel Sileshi/AFP)

Righting a “Historical Imbalance”

Although 85 percent of the Nile waters originate in Ethiopia, Ethiopia has arguably gained the least from the river of all Nile Basin countries; construction of the GERD is thus part of an effort to right this historical imbalance. With the GERD squarely within its borders, Ethiopia has claimed a sovereign right to move ahead with the dam’s construction, filling, and operation even in the absence of an agreement that would allow for monitoring, coordination, and info-sharing with Egypt and Sudan. The dam represents Ethiopia’s assertion of its right to a share of the Blue Nile waters that it has always possessed but never fully utilized. According to Ethiopian officials, international scrutiny of the GERD perpetuates the historical imbalance that has long existed. Ethiopian officials point out that no other dam on the Nile has received such a high level of scrutiny even though Egypt, Sudan, and other Nile riparians have been building dams since the 1960s.93

Ethiopia justifies its right to correct this historical imbalance with a core tenet of international transboundary water resource governance: the “equitable and reasonable utilization” principle. This principle allows each riparian “to use and develop an international watercourse in a manner consistent with adequate protection of the watercourse and subject to consideration for the interests of other watercourse states.” The principle is general and subject to interpretation; the UN Watercourse Convention specifies that equitable and reasonable utilization requires taking into account “all relevant factors and circumstances” such as geography and hydrography, social and economic needs, population dependency, effects of use on other watercourse states, existing and potential uses, conservation of the watercourse, and availability of alternatives to a particular use.94 The Ethiopian government argues that Ethiopia has historically not used its equitable share of the Blue Nile and that it will operate the GERD in a manner consistent with international law. Egypt counters that Ethiopia has failed to appropriately account for Egypt’s existing use of the Nile. Egypt also cites another principle of international watercourse law, the obligation not to cause significant harm to other watercourse states, as further proof for the need of an agreement. The precise interpretations of “equitable and reasonable utilization” and “obligation not to cause significant harm” remain points of contention between the two countries.

- 29 -

“If you are a really good person, pray for me for just one thing—that I can manage our debt.”

– Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed 95

Sudan

Despite initially supporting the GERD in 2013, Sudan became concerned by Ethiopia’s disregard of the DoP as Ethiopia began to unilaterally fill the dam. Sudan faces immediate threats to its own water security given that its Roseires Dam sits 100 km downstream from the GERD and is only one-tenth of the size. Concerned about flooding due to poor coordination between the dams, Sudan supports a legally binding agreement that forces Ethiopia to share information required to operate its dam properly. In this dispute, Sudan finds itself to be the weakest party, especially given its recent military coup and its own development challenges.

Wavering Position

Like Egypt, Sudan claims “historical rights” to the Nile River waters according to the two colonialera treaties. For this reason, Sudan also refused to sign the CFA over Article 14b, which excluded the clause promising “to not adversely affect the water security and current uses and rights of any other Nile Basin state.”96 However, Sudan was not always opposed to the GERD. In fact, in 2013, then President Omar al-Bashir told the Ethiopian ambassador to Sudan that he supported the dam.97 A year later, President al-Bashir noted the potential benefits the GERD would provide for Sudan, saying, “Aswan is useful to Egypt, and GERD is life to Sudan.”98 Even after construction started on the dam, Sudanese Foreign Minister Ibrahim Ghandour stated, “We made sure that the dam is being built in a safe way so that Sudan is not harmed,” signaling that he was content with the assurances provided by his Ethiopian counterparts.99

However, Sudan changed its position once Ethiopia began unilaterally filling the dam in 2020 and aligned itself with Egypt. The two countries lobbied unsuccessfully for the UNSC to lead a negotiation process among the three parties. Sudan also began to align itself militarily with Egypt, which sent a strong signal of protest to the Ethiopian government ahead of the second filling. In March 2021, Sudan and Egypt signed a military cooperation agreement in response to increased instability in the Horn of Africa, including the armed conflict within Ethiopia.100

- 30 -

Sudanese houses flooded after heavy rains in 2020. (Source: Al-Monitor/Getty Images)

Egypt has called for political stability in Sudan since the October 2021 coup and has considered playing a mediating role in a negotiation to secure a transitional government. Despite this political turmoil, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan have continued to cooperate on issues related to the GERD. Following the Sudanese leader’s visit to Cairo in March 2022, Egypt announced humanitarian assistance for Sudan ahead of the third filling of the GERD scheduled in July, which both countries condemned.101

Protecting the Roseires Dam

Perhaps the greatest concern for the Sudanese is the operability of the Roseires Dam, which supplies the country with 80 percent of its electricity. In general, electricity access in Sudan is low; only 39 percent of the population was connected to the national grid as of 2016. Sudan is also heavily reliant on hydropower, which supplies the country with 75 percent of its electricity.102 The Roseires Dam, a hydropower dam that produces 1,800 megawatts annually, is one of six dams that Sudan has built on the Nile. Only 210 kilometers downstream from Roseires is the Sennar dam, an irrigation dam that has less than one percent of the storage capacity of the GERD.

Failure at the Roseires Dam has the potential to affect the lives of the 20 million Sudanese who live along the Blue Nile. For this reason, Sudan seeks some information-sharing mechanism that would allow it to properly operate its own dam. Without information from Ethiopia regarding the release of water at the GERD, Sudan cannot coordinate releases at its Roseires Dam, leaving itself at risk for both flooding and droughts. Flooding did occur in 2020 after the first unilateral filling of the GERD, which shut down 13 water stations and caused significant power outages according to Sudan’s Water Resources Minister Yasser Abas.103

Fearing a similar situation ahead of the second filling, Sudan sent a letter to the UNSC in June 2021. In the letter, Sudan cited technical experts who said flooding from the second filling of the GERD could result in a 47 percent decrease in the hydropower generation at the Roseires Dam and a 45 percent decrease at the Merowe Dam due to flooding. Ultimately, the second filling decreased water flow to the Roseires Dam by 50 percent, impacting irrigation systems and decreasing the amount of available drinking water.104

- 31 -

Sudan’s Roseiries Dam. (Source: International Hydropower Association)

Threat to Water Security and Agriculture

Like Ethiopia, Sudan faces its own development challenges, which it has been unable to address fully due to its own tumultuous political history. Historically, Sudan has relied heavily on oil exports to bolster its economy. However, when oil-rich South Sudan seceded from Sudan in 2011, Sudan lost more than half of its government revenue.105 As a result, economic growth declined, and inflation increased to double-digit levels, leading to violent protests in September 2013. However, the secession was not the only cause of Sudan’s emerging economic crisis; many structural economic problems can be traced back to President Omar al-Bashir’s rule from 1993 to 2019. Under President al-Bashir, the country incurred $60 billion in debt, which has limited its access to international loans. Currently under military rule, Sudan lacks the stability and international legitimacy required to pursue additional development projects.

The country’s challenges include equitable access to water and sanitation. Seventy-three percent of Sudan’s freshwater needs come from the Nile River and its tributaries.106However, its access to the Nile River has not translated into water security for the Sudanese. Approximately 17.3 million people lack access to drinking water, and 24 million lack access to sanitation facilities.107 The spread of waterborne diseases, including cholera and diarrhea, is also a concern during periods of flooding. Flooding complicates waste removal, leading to an increase in the prevalence of these illnesses. Therefore, Sudan views the proper management of the GERD as necessary to addressing its own water scarcity and sanitation concerns.

Furthermore, the Nile River is inextricably linked to Sudan’s agricultural activities. After South Sudan seceded, the Sudanese government grew even more reliant on agriculture to drive its economy. In particular, Sudan has parceled and sold land to foreign governments, including the Saudi Arabia, which leased one million acres in 2016, and Bahrain, which leased 100,000 acres shortly thereafter.108 Development experts and economists agree that Sudan could feed water-scarce countries in the Middle East as well as food-poor countries in Africa. As of 2020, agriculture made up 40 percent of Sudan’s economy and employed 80 percent of its workforce.109 This agricultural activity accounts for a whopping 97 percent of Sudan’s water use.110 According to Sudan’s letter to the UNSC in June 2021, the GERD threatens over 70 percent of its irrigated agriculture and could result in “loss of over half of its agricultural floodplain agriculture.”111

- 32 -

Ethiopia has stated its intention to export electricity generated at the GERD, which could help promote development in Sudan. However, the Sudanese government indicated that they would like an agreement.112 This illustrates that Sudan’s fears over GERD’s impact on its domestic development projects overshadow its hopes for imported energy.

Stake of Nile Basin Countries

There are eleven riparian countries that share the Nile waters. Together, the countries have been involved in the NBI, founded in 1999, to promote cooperative management of these water resources. Notably, outside the three parties involved in the GERD dispute, other riparian countries have not sided with any party in the dispute. While these upstream countries have remained silent, it does not mean they do not have a stake in a conflict whose outcome will likely set a precedent for future projects on the Nile. Egypt has helped fund several infrastructure projects in riparian countries, including the Julius Nyerere Dam project in Tanzania and a solar power plant in Uganda. However, Ethiopia has maintained the GERD will provide benefits to its neighbors through energy exports. Being courted by both Egypt and Ethiopia, riparian countries have preferred to stay neutral and support the AU-led process.

Above: Ambassadors and representatives from Nile Basin Member States, a delegation from the European Union, and representatives from the Nile Technical Advisory Committee meet in 2022 (Source: Nile Basin Initiative)

Prior Page: A Sudanese farmer plants crops along the Nile in 2009 (Source: Council on Foreign Relations)

- 33 -

Barriers to an Agreement

Nationalism in the Face of Domestic Crises

Both President El-Sisi and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed face challenges at home that they fear threaten their hold on power. The two leaders may seek to use the GERD to rally unified domestic support in face of these internal challenges, making concessions on the GERD politically costly. In Egypt, the government has struggled to facilitate sustainable economic growth since the fall of Mubarak in 2011. Instead, the government accumulated external debt to fund large-scale infrastructure projects. Propped up by foreign investment, Egypt became vulnerable to external shocks like the war in Ukraine. Between February and March 2022, nervous investors bracing for a potential global recession decided to pull out $20 billion from Egypt.113 To address Egypt’s economic instability and high levels of debt, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) agreed to a $3 billion loan. Shortly after, the value of the Egyptian pound plummeted to 24 pounds against the dollar due to the loan’s condition for implementing a flexible exchange rate regime. The loan includes other conditions related to governance and structural reforms that may lead to economic pain for Egyptians in the short-term.

Scholars have argued that the Egyptian government has painted Ethiopia as a boogeyman that threatens their water security - and thus, their livelihoods - to drum up domestic political support. Viewed in this way, Egypt’s saber-rattling and threats of “all options on the table” may not have targeted Ethiopia but rather served as a way to stoke nationalist fervor in Egypt.114

As an economic crisis plagues the Egyptians, political instability and armed conflict have also threatened Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s hold on power in Ethiopia. Since 2020, the Ethiopian military has been fighting the TPLF in Tigray, resulting in a civil war that has left thousands dead and has displaced millions. There have been reports of human rights violations committed by all parties involved.115 In December 2021, armed forces in the Amhara region increased their violence against ethnic Tigrayans. Meanwhile, ethnic violence and uprisings have continued elsewhere in the country alongside the Tigray conflict. The Ethiopian government has been battling ethnic militia who have launched attacks in the region where the GERD is located. Escalating waves of ethnic violence in the Oromia region have taken a mounting humanitarian toll and threaten Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s control.

The GERD is one of the few domestic issues that has support from virtually all Ethiopians, regardless of ethnic and religious affiliation. As previously mentioned, ordinary Ethiopians financed the dam through the purchase of dam bonds or through small (often forced) salary donations. Some local taxi drivers don #MyDam stickers to publicly display their contribution to the dam.116 Furthermore, there is evidence that the Ethiopian government conducted public campaigns on Facebook to target its own domestic audience with nationalist rhetoric in support of the dam. The campaign was particularly active between 2020 and 2021 during the intensification of the conflict in Tigray.117 To deal with its fragmented society, the government has rallied behind the GERD as a national symbol

- 34 -

to garner support for Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed.

If both leaders continue to feel unstable in their positions of power, they may continue to use the GERD to drum up public support, further entrenching them in their respective positions. With GERD as a politically salient issue for both domestic audiences, any concessions made by the leaders to solve the dispute might cost them significant political capital.

Lake

Turkana Controversy

Although the GERD dispute has received the most international attention, the Gibe III is another example of a transboundary dispute between Ethiopia and another riparian country, Kenya, that has arisen due to a lack of consultation and coordination with neighboring governments and their communities. In 2016, Ethiopia inaugurated Gibe III, a hydroelectric dam on the Omo river. The river supplies 90 percent of the water to Lake Turkana in Kenya. Hundreds of thousands of Kenyans living downstream also rely on the annual flood to support their crops, and the lake is an important source of fish stocks. According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), the lake’s water level dropped 363 meters the year the dam opened.122 During the same year, communities complained that the amount of water released by the dam was not enough to sustain agricultural activities. Furthermore, Ethiopia will divert most of the water from the dam to its Kuraz Sugar Development Project, the country’s largest agricultural venture.123

Regional Rivalry

Both Egypt and Ethiopia are jostling for influence in the Horn and in Africa and the Greater Middle East as a whole. This geopolitical rivalry may also complicate GERD negotiations. In addition to Egypt’s efforts to control use of the Nile, Egypt has also made efforts to ensure Ethiopia remains weak and unable to pursue future projects on the river. For this reason, Egypt supported Eritrea’s independence from Ethiopia and currently hosts Eritrean opposition groups in the country.

118 Although Egypt has denied any involvement in the recent conflict with the TPLF, if rumors of its support were true, they would represent yet another example of Egypt’s attempts to destabilize Ethiopia.

Ultimately, the GERD is a direct challenge to Egypt’s historical dominance over Nile waters.119 By pursuing its own development, Ethiopia hopes to realize its identity as an “African lion” - a term used to describe Ethiopia during its economic boom between 2005 and 2015.120 To gain influence

- 35 -

Lake Turkana, Kenya. (Source: Kanaga Africa Tours)

over its neighbors, Ethiopia has continued to refer to the GERD as “a site of cooperation” that will benefit all its neighbors’ needs for electricity imports.

Following the political turmoil of the Arab Spring, Egypt’s resulting domestic problems, and the rise of the Gulf countries as hegemons in the Arab world, Ethiopia may see an opportunity to increase its regional influence. While Egypt has had to rely heavily on financing from its Gulf allies, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have fostered ties with Ethiopia and have indicated they remain unwilling to take sides in the dispute.121 In this context, Ethiopia may see the GERD dispute as part of its larger efforts to reshape geopolitics in the Horn of Africa.

Situational Power Imbalance and Lack of Trust

Given that it stands to benefit from the status quo, Ethiopia lacks incentives to come to agreement on the GERD. Meanwhile, Egypt lacks diplomatic, political, or economic leverage over Addis Ababa to push it toward an agreement. Although Egyptian officials have not ruled out the possibility of military action in a time of crisis, most analysts agree that it would be expensive and prohibitively difficult logistically and diplomatically for Egypt to render the dam inoperable. Consequently, a clear power imbalance exists in favor of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa has little incentive to make concessions in a trilateral context in which it holds all the cards. Any agreement, therefore, will likely require some form of external pressure or incentives to make the prospect of compromise appealing to Ethiopia.

Mutual distrust between Egypt and Ethiopia exacerbates this power dynamic. Each country views the other as a regional rival attempting to exert undue influence over internal affairs. The Ethiopian government perceives Egypt’s insistence on a GERD filling and operational agreement as an attempt to place legal restraints on Ethiopia’s sovereign right to development. Rumors of Egyptian support for TPLF rebels in the Ethiopian civil war further fuel the Ethiopian government’s skepticism toward Cairo. Reports of Egyptian “meddling” in Tigray, including through the alleged provision of materiel to rebels, are regularly cited as evidence of Cairo’s desire to keep Ethiopia weak.

Egyptian officials view the construction of the GERD as an Ethiopian attempt to place a stranglehold on Egypt. They claim that Addis Ababa has no intention to accept an agreement and is intentionally stalling negotiations to make the construction of the GERD a fait accompli. Even if an agreement is reached, Cairo has little faith that Addis Ababa would adhere to its terms; Egyptian officials claim that Ethiopia has regularly abrogated its Nile-related promises, including the 2015 DoP, which they cite as evidence of bad faith. Egyptian officials say that Prime Minister Abiy lacks the political will necessary to sign onto an agreement, especially given his use of the GERD as a way to unify the country amidst serious internal strife.

Against a backdrop of historical animosity dating back thousands of years, Egypt and Ethiopia’s mutual distrust is exacerbated by their competition to be the region’s dominant power. Consequently, an undercurrent of power struggle permeates the gridlock over the GERD even when officials agree on technical solutions.

- 36

-

“Blue” Versus “Green” Water

Some Egyptian water experts have suggested distinguishing between “green water” and “blue water” when addressing the question of water management. Blue water includes stores of surface and groundwater, such as lakes, rivers, dam reservoirs, and aquifers, that can be extracted for use. The Nile and its tributaries, for example, are sources of blue water. Green water consists of water originating from precipitation that does not contribute to usable stores but that temporarily remains in the ecosystem as moisture before it is lost to evaporation or transpiration from plants. Green water is site-specific and has limited uses, the most significant of which may be rain-fed agriculture.124 Egyptians who advocate for distinguishing between blue and green water in a GERD agreement are effectively making the case that Egypt should get the rights to more of the Nile waters because, unlike Ethiopia, Egypt receives essentially no green water. However, because the uses of green water are relatively limited in Ethiopia at this time, we assess that this distinction is not helpful for addressing the GERD dispute.

Scope of an Agreement

Perhaps the greatest barrier to reaching an agreement is deciding on the scope and form that an agreement would take. Egypt and Sudan prefer a legally binding agreement that would: 1) govern the filling and long-term operation of the GERD; 2) provide assurances that Egypt and Sudan’s “current use” of Nile waters will not be adversely affected; 3) guarantee a minimum level of water flow during periods of drought; 4) establish a dispute resolution mechanism through a third party; and 5) address future development on the Blue Nile. Ethiopia, meanwhile, prefers an informal understanding like the CFA, which would not mandate coordination or information-sharing but rather promote cooperation over all Nile waters. Due to concerns over sovereignty, Ethiopia opposes any agreement that would subject the country to international arbitration or allow for punitive measures imposed by a third-party in case of a dispute; it instead prefers that disputes be resolved directly between the heads of state of Egypt, Ethiopia, and Sudan according to the

- 37 -

Heavy rainfall in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (Source: Wikimedia Commons/Ralf Steinberger)

procedures detailed in the DoP.

Despite the lack of an agreement, Ethiopia maintains that it will operate the GERD in a manner that benefits both its development and the needs of its neighbors. The government asserts it does not need an agreement to complete the filling of the dam and begin operating the GERD responsibly. Consequently, assurances for a drought mitigation protocol are unnecessary in its view. Ethiopian officials are adamant that the GERD not be beholden to Egypt’s drought management plans. In other words, Ethiopian officials say that Ethiopia should not bear responsibility for Egypt’s water security in times of drought. Instead, they say that Nile riparians should bear the burden of drought management equitably and take measures to reduce their water consumption; in Ethiopia’s view, Egypt is not willing to do enough to reduce its dependence on the Nile. In this vein, Ethiopia is hesitant to agree to obligatory information-sharing systems, instead preferring the flexibility to pick which information it shares and how frequently.

What about the UAE Role?

The UAE has been involved in GERD negotiations since Sheikh Shakhboot Bin Nahyan was appointed the UAE’s Minister of State for African Affairs in early 2022. Little public information about the UAE process is available, though news reports indicate Minister Shakhboot has assembled a team of technical experts to aid negotiations. Publicly, the UAE effort is conducted in support of the AU-led process, though the extent of the coordination between the two efforts is unclear. Given Minister Shakhboot’s apparent interest in resolving the GERD dispute, the United States should coordinate bilaterally with the UAE to ensure the two countries’ efforts complement one another in moving the AU-led process forward.125, 126

- 38 -

UAE President Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan (left) and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. (Source: Borkena/Madote)

Recommendations

To promote peace and stability in the region, the GERD dispute should remain a high priority of the United States. Ideally, Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia should enter into a formal agreement that would address issues like drought mitigation and information sharing and would include a conflict resolution mechanism. However, the current political context and barriers described above make achieving a legally binding agreement unlikely. Given current constraints, we recommend that the Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa focus on helping the countries establish a mechanism for drought management as a means to reduce tensions between Egypt and Ethiopia, address Egypt’s top concern, and build momentum toward the possibility of a comprehensive agreement.

Given that Ethiopia has shown little interest in entering into a formal agreement that only addresses drought management, we recommend that the United States encourage both countries to come to an understanding on drought mitigation through the exchange of diplomatic notes. The content from these notes can be used to inform a full agreement if and when conditions become more favorable.

Next, the United States should help the three countries establish consistent, regular, and mutually agreed upon inter-dam communication channels to address the immediate need of coordinating dam operations to protect existing water infrastructure (e.g., Roseires Dam and High Aswan Dam) and prevent flooding that could impact or displace people living in the Nile Basin. Meanwhile, the United States should use its tools of influence to incentivize each party to remain engaged in the AU-led negotiations with the ultimate goal of signing a formal agreement. These tools of influence include promoting development and water management projects in both Egypt and Ethiopia, which have the additional benefit of increasing their resilience to droughts. We provide greater detail of these recommendations below:

- 39 -

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed (Left) meets with Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi in 2019. (Source: Office of the Egyptian Presidency)

I. Establish drought management measures.

Until a legally-binding agreement can be established, we recommend that Egypt and Ethiopia develop a plan for drought management measures as an intermediate step to reduce tensions between the two parties and address the significant risk posed by sustained periods of drought. Instead of engaging in a formal negotiation process on drought management, the United States and international community should encourage Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia to exchange diplomatic notes as a part of a unilateral but coordinated planning process to deal with drought scenarios. Compared to formal talks, which have repeatedly failed, notes will provide each party a space to move from their public positions and signal to each other potential concessions.

It is understood that the three countries have already discussed mitigation measures during previous negotiations that would address dry years, droughts, and prolonged droughts. Whatever has been agreed upon should serve as a baseline for the diplomatic notes. Additionally, the notes should outline a process for what meetings or actions should be initiated if conditions for an extreme drought are observed. For example, the three heads of state could agree to meet when such conditions are initially detected; or alternatively, the AU could convene the three leaders with the other Nile Basin countries as observers. The notes should also be used to share each party’s domestic plans to reduce water consumption during drought, which would help allay Ethiopia’s concerns that Egypt is not doing enough internally to prepare for a worst case scenario. Although the exchange of these notes would fall short of a formal agreement - which would be Egypt’s preference – it would allow both parties to openly communicate and negotiate the key issues without the pressure of their constituencies. This solution of coordinated unilateralism, if managed well, could also allow Egypt and Ethiopia to claim a political victory internally. Egypt would get in writing what it needs the most – drought management – while Ethiopia would avoid having to sign a binding agreement that would limit its future development.

- 40 -

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed turns on power at the GERD.

(Source: Ahram Online/Ethiopian Prime Minister’s Official Twitter Account)

II. Promote inter-dam communication.