Puerto Rico’s Renewable Energy Mandate

Recommendations for an Equitable Transition

March 2023

This report is the final product of a 2022 Policy Workshop sponsored by the Princeton University School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA) as part of its Master in Public Affairs degree program. All members of the project team participated in discussion, debate, and preparation of this report.

Lead Professor

Eduardo Bhatia

Report Authors

Hannah Ceja

James Duffy

Cherrita Guy

Caroline Hayes

Ryan Klaus

Hilary Landfried

Shua-Kym McLean

Kacie Rettig

Bryson Rose

Parker Wild

Editors

Hannah Ceja

Cherrita Guy

Ryan Klaus

Parker Wild

Designers

James Duffy

Kacie Rettig

Suggested Citation

Princeton University. (2023). Puerto Rico’s Renewable Energy Mandate: Recommendations for an Equitable Transition. Policy Workshop Report. Princeton School of Public and International Affairs.

Disclaimer

The report presented here does not represent the views of Princeton University, any individual instructor, any individual student, or any person interviewed by this workshop.

3

Acknowledgements

On behalf of our report team and the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, the authors would like to give a special thanks to the following individuals, organizations and community members for their insights, perspectives and willingness to meet with us before, during and after our time in Puerto Rico:

Communities of Puerto Rico

Community Members of Castañer

Community Members of Adjuntas

Community Members of Culebra

Organizations

Cambio PR

Casa Pueblo

Center for A New Economy (CNE)

Cooperativa Hidroeléctrica de la Montaña

Environmental Defense Fund (EDF)

Fundación Comunitaria de Puerto Rico / Puerto Rico Community Foundation

Hispanic Federation - Puerto Rico

LUMA Energy

Mujeres de la Isla

National Renewable Energy Laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy (NREL)

Office of the Governor of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico Energy Bureau (PREB)

Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA)

Queremos Sol

Rocky Mountain Institute

Solar and Energy Storage Association of Puerto Rico (SESA)

U.S. Department of Energy

Individuals

Alberto Santiago

Alexis Massol González

Angel Figueroa-Jaramillo

Angel Rivera

Arturo Massol Deya

Charlotte Gossett Navarro

Clare Sierawski

CP Smith

Edison Avilés-Deliz

Elizabeth Arnold

Ferdinand Ramos-Soegaard

Francisco Berrios Portela

Ingrid Villa

Javier Rua

Jia Jun Lee

Josué Colón

Lillian Mateo Santos

Lord Nicholas Stern

Marisol Bonnet

Mario Hurtado

Michael Liebman

Nate Blair

PJ Wilson

Robin Burton

Roy Torbert

Ruth Santiago

Sergio Marxuach

Sylvia Ugarte Araujo

Vernice Miller-Travis

4

Table of Contents Executive Summary 6 Summary of Recommendations 7 Introduction 9 Part I: Policy Context 11 Section A: Puerto Rico's Energy System 11 Section B: The Economic Barriers to Energy Justice 14 Section C: Challenges to Accessing Seed Funding Sources for Future Development 21 Part I Summary 24 Part II: Recommendations 25 Section A: Alleviating Barriers to Renewable Energy for LMI Communities 25 Section B: Institutional Reform 28 Section C: Eliminating Financial Hurdles to the Renewable Energy Transition 32 Part III: Guiding Principles for Puerto Rico's Energy System 37 Conclusion 38 Appendix A: Glossary 39 Appendix B: Green Energy Trust Tables 40 Author Biographies 46 Endnotes 47 5

Executive Summary

Puerto Rico is currently not on track to comply with the first renewable energy target of Act 17, requiring 40% renewable generation by 2025. In 2019, the Puerto Rico legislature passed the Puerto Rico Policy and Energy Act (“Act 17”), mandating 40% renewable generation by 2025, 60% by 2040, and 100% by 2050. Yet, an outdated grid and challenging political environment continue to hinder efforts to transition, and access to reliable service across the island is worsening. Given that Puerto Rico is far away from reaching its first Act 17 target, this report provides recommendations for officials in both the Government of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Federal Government aimed at facilitating a smoother, faster, and more equitable transition to renewable energy on the island.

Puerto Rico exited bankruptcy in early 2022, and is now at a turning point. Its economy cannot grow without a functioning energy sector, and in many ways, Puerto Rico is primed to make a more rapid transition to renewable energy. Furthermore, there is substantial federal funding available to modernize Puerto Rico’s grid following Hurricane Maria in 2017, and recent regulatory reforms broke up the public electric utility monopoly on the island and created an independent regulatory body, the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau (PREB).

Our report focuses on four areas where improvements may have catalytic effects. First, all government agencies must anchor energy justice at the center of their transition strategy and implementation, as current transition efforts are leaving last mile communities behind. Both utility and small-scale solar installations are needed to support these communities, and must be financed and implemented in an equitable manner. There is a lack of financing options available for micro-level projects in these communities, and for renters, targeted energy efficiency programs could help lower burdensome rates.

Second, Puerto Rico Energy Power Authority (PREPA) and LUMA Energy (LUMA), the power company in charge of energy distribution, continue to deal with legacy issues from previous mismanagement of the grid and generation assets. They struggle to manage an outdated and damaged grid while providing new infrastructure. PREB should take on a stronger leadership role in the transition. As an independent and apolitical regulator, PREB can chart a path to regulatory and financial stability in the energy sector while communicating openly and transparently with the public to build trust. There are opportunities to restructure the power sector by bringing in new apolitical actors, such as Independent System Operators (ISOs).

Third, given the amount of government actors involved, strengthening public trust will be important throughout the renewable energy transition. Enhanced communication between government agencies and Puerto Rico’s public would increase trust, accountability and take a critical step towards better engaging communities and identifying avenues for public participation in the green energy transition.

Lastly, the federal government has committed approximately $12 billion to rebuild Puerto Rico’s energy sector, but disbursement has been significantly delayed. Administrative red tape, extensive application requirements, matching requirements, and changing federal administrations have all contributed to the delays. The failure to rebuild and provide adequate energy infrastructure puts the health and well-being of all Puerto Ricans at risk. The federal government should streamline funding approvals, center vulnerable communities, and waive the Jones Act for materials to rebuild and modernize the grid. While federal funds will play a critical role in Puerto Rico’s transition, Puerto Rico’s Green Energy Trust should also be strengthened to attract private investment capital.

These recommendations have a broader significance. Around the world, the number of countries committing to net-zero by 2050 is growing quickly, and as of May 2021, these commitments covered 70% of global emissions of CO2.1 At the end of 2021, 31 states and the District of Columbia had renewable portfolio standards or clean energy standards, and 20 states had committed to 100% clean electricity by 2050.2 According to the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, reaching net zero by 2050 requires rapid deployment of available technologies through 2030.3 The 2020’s must be a decade of massive clean energy expansion to reach these targets. Each country and state face different conditions and challenges in their transitions but all must grapple with how to ensure vulnerable communities are not left behind, develop unified plans across agencies, and obtain the necessary financing.

Recent reforms and the renewable energy targets in Act 17 are a significant step towards Puerto Rico’s renewable energy transition, but much remains to be done to achieve these goals. Still, plenty of time remains for officials to amplify the renewable energy transition in hopes of actualizing this vision. In alignment with the island’s commitment to 100% renewable energy, the policy recommendations provided in Part II serve as concrete steps that policymakers and government officials can consider, before and after the publication of the United State's Department of Energy's completed PR100 study. This report’s section recommendations coupled with the energy justice framework discussed in Part I also demonstrate the existing policy tools and mechanisms that Puerto Rico can leverage to attain its renewable energy objectives.

Known as the Island of Enchantment, Puerto Rico’s leadership in its renewable energy transition will help lead the way in charting a brighter clean energy future for its residents, for other islands and for the world.

6

Summary of Recommendations

Alleviating Barriers to Renewable Energy for Low and Middle Income Communities

In approaching the renewable energy transition, and in anticipation of the PR100 study, we recommend that government actors, including the local and federal government stakeholders:

1) Identify energy insecure regions and target efforts to those regions. Specifically we recommend they:

· Establish a Social Vulnerability Index specifically for Puerto Rico.

· Invest in enhanced data collection and reporting.

· Employ cost of living measurements across Puerto Rico.

· Engage directly with communities and community leaders.

· Identify active non-profit, community-led projects and projects led at the municipal level, focused on renewable energy installations and microgrids.

2) Engage with solar leases and power purchase agreements. Specifically we recommend they:

· Provide direct financial assistance and cash payments for homeowners who enter a lease or new power purchase agreement (PPA) for rooftop solar.

· Require third parties to include a production guarantee.

· Promote the installation of batteries.

· Work with companies to lower the credit score required to enter into a lease or PPA agreement.

· Retain and extend the net metering program while balancing customer equity and financial restraints.

3) Employ targeted energy efficiency programs. Specifically we recommend they:

· Update building codes to include both weatherization and appliance requirements.

· Provide funding or cost saving opportunities for qualified landlords.

· Phase in requirements, and require and enforce timely weatherization updates.

Institutional Reform

Leading to the renewable energy transition, we recommend Puerto Rican government actors:

1) Restructure the electrical power sector. Specifically we recommend:

· LUMA should only be responsible for maintenance of the transmission and distribution system.

· An Independent Service Operator (ISO) should operate the system in real time and plan future grid investments.

· Policymakers should learn from the experience of other jurisdictions that established ISOs to ensure Puerto Rico’s reforms are successful.

· The Puerto Rico Energy Bureau (PREB) should commission a comprehensive study on the viability of a wholesale electricity market for Puerto Rico.

2) Ensure PREB maintains independence. Specifically, we recommend the Puerto Rican government keep PREB apolitical and deter any political influence.

3) Work to enhance public trust of energy system actors, and enhance communication. Specifically, we recommend:

· LUMA increase staffing on its customer support lines.

· LUMA improve personal solar systems interconnection and provide clear timelines for interconnection.

· LUMA improve access to green energy information.

· PREB introduce a Public Value framework to increase public trust.

· PREB enhance its website to improve online presence and communication.

· PREB increase engagement on social media platforms.

7

Eliminating Financial Hurdles to the Renewable Energy Transition

In preparation for the transition, we recommend federal and local actors increase access to public infrastructure funding and finance. This includes:

1) Ensuring FEMA funds for permanent work reach communities in Puerto Rico. Specifically, we recommend the Department of Energy work with the relevant Puerto Rican and federal agencies, and employ federal funding, to:

· Fund a workforce program focused on rebuilding the electrical grid, that is protected from bankruptcy-related intervention.

· Incentivize Puerto Rican engineers’ involvement in rebuilding the energy grid, by establishing a federallyfunded program which provides salaries that are competitive with mainland salaries.

· Fund and invest in training and certification programs for green energy jobs.

· Create and train a workforce of administrative staff, to make available to municipalities for grant processing.

· Work with local leaders and governments to streamline funding to high-need areas.

2) Alleviating barriers to FEMA funds, and reduce infrastructure cost. Specifically, we recommend FEMA:

· Review the Alternative Procedures Program and identify and eliminate unnecessarily burdensome processes.

· Waive reimbursement requirements for permanent work in LMI and vulnerable communities.

· Work with DOE to identify all materials that will be used to rebuild the grid, establish microgrids, and meet the renewable energy mandate and, where possible, request that the White House waive the Jones Act for Puerto Rico’s imports of these materials.

3) Enhancing Puerto Rico’s access to investment in green energy development. As such, we recommend the Government of Puerto Rico bolster its Green Energy Trust Fund by:

· Launching residential and commercial term loan products as a top priority for the Green Energy Trust.

· Engaging with credit enhancement products, which can help incentivize private investors to lend to vulnerable communities.

· Engaging with long-term product options, which include on-bill and commercial property assessed clean energy financing.

· Increasing staff capacity and leadership, which are crucial to the Green Energy Trust’s success.

· Employing IRA funding, which represents a significant opportunity for the Green Energy Trust to secure capitalization funds.

· Pursuing other complementary sources of funding to the IRA’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

Renewable Energy Options

Finally, we discuss possible renewable energy pathways to consider when moving forward with the transition. We recommend energy transition actors at the local and federal level work to:

1) Increase resiliency through hardening of existing grid infrastructure and grid decentralization.

2) Invest in both utility-scale and distributed generation to meet the needs of different communities.

3) Pursue a portfolio approach to renewable energy generation rather than relying solely on solar and storage.

8

The Puerto Rico Public Policy and Energy Act (“Act 17”) of 2019 created a Renewable Portfolio Standard of 40% renewable generation by 2025, 60% by 2040, and 100% by 2050.4 Despite local communities calling for change and local and federal government efforts, Puerto Rico is not on track to meet its 2025 target. In 2021, more than 95% of the island’s energy still came from imported fossil fuels.5

This challenge is compounded by the bleak reality that many households within Puerto Rico continue to live with a weak, inefficient and disrupted electrical grid. Major damage caused by Hurricane Maria has only worsened the overall quality of the energy system and there are long-term structural issues that require evaluation and repair to make the energy system optimal. In addition, the unreliability of the electrical grid has amplified public health concerns, policy challenges, and has also contributed to loss of life on the island. This report aims to provide critical institutional

sections of this report offer concrete policy recommendations to alleviate renewable energy barriers to low and middle income (LMI) communities, while also eliminating financial hurdles that may be impeding the island’s broader renewable energy transition.

Despite the many challenges facing the island, the tools necessary to facilitate change are already present. By many metrics, Puerto Rico is poised to make a rapid transition to renewable energy. In addition to Act 17’s (clear policy objectives, substantial funding has been committed for modernizing and improving Puerto Rico’s energy infrastructure. Specifically, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and other federal agencies have committed approximately $12 billion to rebuild and modernize the island’s energy system.7 Moreover, recent reforms have created a more balanced regulatory environment for the development of the energy system. In 2014, the Puerto Rico Energy Bureau (PREB) was

and policy context detailing why these challenges are pervasive in the Commonwealth, and present recommendations for how to alleviate them in order to better serve the people of Puerto Rico, while realigning with Act 17 targets.

Antiquated energy generation, dependence on imported fossil fuels, and disruption to the grid have increased spatial inequities to energy access. This has also resulted in hampered economic mobility, increased barriers towards debt crisis recovery, and has stifled the emergence of clean energy industries that would have contributed to economic growth. With a poverty rate of approximately 43 percent based on 2020 data6, the economic growth required for Puerto Rico to combat financial and economic distress cannot be achieved under the current energy system structure. As a starting point, the following

established by Act 57 as an independent and specialized body, with regulatory authority to monitor and enforce the energy public policy of the Government of Puerto Rico.8 Subsequently, the transmission and distribution (T&D) functions were separated from generation, breaking up the vertical monopoly previously held by the island’s public electric utility, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA).

To assist Puerto Rico in reaching its renewable energy goals as established by Act 17, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and five of its national laboratories are performing a comprehensive analysis of technical pathways to 100% renewable energy. The study, entitled Puerto Rico Grid Resilience and Transition to 100% Renewable Energy (PR100), will produce high-resolution datasets and open-

Introduction 9

source models that inform policymakers’ decisions about the future of Puerto Rico’s energy system, but it will not include specific policy recommendations or a detailed implementation plan. Instead, the authors will convey potential pathways to fulfill the 100% renewable energy goal and examine their impacts, in addition to performing analysis that will help stakeholders make informed investment decisions. Finally, recommendations will be focused on short- and long-term actions for the transition. The full report is expected to be complete by the end of 2023.9

In our conversations with Puerto Rican stakeholders, many expressed their enthusiasm for the island’s renewable energy future and the potential outcomes of the PR100 study. However, given that the study will only include analysis of technical pathways to 100% renewable energy, the strategic application and policy guidance needed to realize these technical pathways will be out of scope. Accordingly, the PR100 study will heighten the responsibility of government officials and policymakers in Puerto Rico to identify, define, and implement the next steps to actualize the technical pathways analysis and move the island’s renewable energy transition forward.

Yet, existing diffusion of responsibility among Puerto Rican energy policymakers paired with a lack of clear leadership for implementing the PR100 findings, increase the likelihood of inaction. It also risks a lack of agency coordination, and a failure to capitalize on PR100 to achieve Puerto Rico’s renewable energy goals. Decisive action in response to the PR100 findings remains unlikely if policymakers do not proactively address the current fragmented state of Puerto Rico’s energy policy landscape.

Puerto Rico’s energy oversight structure, comprising PREPA, LUMA and the PREB, also hold competing visions regarding the future state of the grid. Although PREPA and LUMA are charged with implementing the island’s renewable energy mandates under the supervision of the PREB, this relationship is often complex and even antagonistic at times, resulting in a misalignment of priorities, circular decision-making and potentially gridlock across the energy system. In the aftermath of Hurricane Fiona, President Biden tasked the U.S. Secretary of Energy with leading the Puerto Rico Grid Modernization and Recovery Team, but DOE lacks policymaking jurisdiction over many of the relevant leverage points in Puerto Rico’s energy sector. To ensure the PR100 findings bring about an effective transition, policymakers and stakeholders must work together to establish an inclusive implementation plan that targets current challenges and identifies specific organizational objectives within the energy system.

Furthermore, wealthier Puerto Rican residents are more likely to install distributed energy resources (e.g., rooftop solar and battery storage) than their LMI counterparts, for whom the upfront cost of residential systems remains a barrier. Since ratepayers have historically borne the burden of PREPA’s debt repayments, failure to address this disparity could result in LMI households being unfairly impacted by future debt restructuring plans that require rate increases.10

In anticipation of the PR100 publication, our report provides policy recommendations to ensure an equitable and rapid transition to renewable energy and prepare the grid for the integration of distributed energy resources.

The cornerstone to this report includes the following seven design principles that, based on our engagement with stakeholders, we believe should guide policymakers throughout Puerto Rico’s renewable energy transition. These design principles should also serve as a platform for policymakers’ evaluation of the technical pathways presented in the PR100 study.

1. Reliability: the grid loses power less often and power quality is high.

2. Resiliency: the grid can withstand and recover from weather events quickly.

3. Affordability: infrastructure investments should prioritize reducing the cost of electricity for consumers.

4. Carbon-free: the grid should reach zero carbon emissions from generation by 2050 in accordance with Act 17.

5. Operational and financial integrity: the entities that manage and regulate the energy system must have the technical capacity and resources to do their job effectively.

6. Accountability to the public: customers should have visibility into and a say in how decisions about the energy system are made.

7. Equity of access and quality of service: regardless location, background, or financial circumstances, residents should be able to access electricity from an energy system with the aforementioned characteristics.

The subsequent sections of our report will be presented as follows: This report first reviews the current policy context related to the Puerto Rican energy system (Part I). Specifically, it evaluates the state of the Puerto Rican energy system and its impact on Puerto Ricans (Section A). Through the lens of our tailored energy justice framework, the report then examines Puerto Rico’s economic development and challenges to an equitable renewable energy transition (Section B). Next, the report outlines private and public seed funding available for future development, and current institutional challenges and barriers to that funding (Section C).

Given this context, we then provide our recommendations (Part II). We conclude with a brief review of the top-line items discussed in our report.

10

Part I: Policy Context

Part I presents important policy context regarding the current state of Puerto Rico’s energy system and details the challenges arising for the island as a result. Our policy discussion provides critical context into Puerto Rico’s energy system and its current institutional oversight (Section A), the economic barriers that are preventing energy justice for low-and-middle-income (LMI) communities (Section B), and challenges to accessing seed funding sources for future development of the energy system (Section C). The conclusions derived from each of these sections will then be leveraged in Part II where we identify concrete policy recommendations to support the elimination of these barriers, institutional challenges and financial hurdles to Puerto Rico’s renewable energy future.

Section A. Puerto Rico’s Energy System

In the current Anthropocene, rapid climate change caused by increased greenhouse gas emissions affects the entire international community. Many local, state, territorial and national governments are taking significant strides to transition to a clean energy future. As an island, Puerto Rico is particularly vulnerable to climate change and natural disasters, as witnessed by the most recent devastating natural disaster brought by Hurricane Maria. Additionally, the challenge of having sequential disasters on the island has left the energy system severely damaged. The combined impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria left the island in need of critical infrastructure repairs and disaster relief. In 2017, Maria downed about 80% of the island’s power lines, after which it took 11 months to fully restore power.11 The series of earthquakes in 2020 also damaged energy infrastructure. Two major power plants, EcoEléctrica and Costa Sur, were both in disrepair. In particular, Costa Sur previously provided about a fifth of power generation for the island as a six decade old facility.12

Thus, the need for developing a scaled and renewable energy system that can sufficiently provide households with equal access to energy and have the capacity to proactively protect the people of Puerto Rico from these climatic vulnerabilities has never been greater.

While the passage of Act 17 solidified Puerto Rico’s commitment to a 100% renewable energy transition, the progress of its transition and overall Act 17 compliance has been slow and piecemeal at best. This is made manifest by the fact that Puerto Rico’s energy system is still heavily dependent on fossil fuels. In FY 2021, 44% of the island’s electricity was generated by natural gas-fired power plants. Petroleum fueled 37% of generation, coal 17%, and renewables 3%.13 Residents in Puerto Rico typically consume about a third of the average per capita energy consumption as the typical U.S. mainland resident and pay roughly twice as much per kilowatt-hour (kWh) as a result.14 Since Puerto Rico is heavily reliant on imported fossil fuels, the cost of electricity generation is dependent on international fuel prices and their market rates.

Within the Commonwealth, there are three primary local actors responsible for the energy system and the recovery of the grid. First,

the public utility Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA, and in Spanish “la Autoridad de Energía Eléctrica”) is responsible for the majority of energy generation on the island. Second, as of the summer of 2021, PREPA contracts out operation of the T&D system to the private entity, LUMA Energy, LLC (LUMA). Canadian company ATCO, Ltd., and U.S. company Quanta Services formed LUMA exclusively for their work in Puerto Rico.15 Finally, PREB, (in Spanish “el Negociado de Energía de Puerto Rico”) has a principal role in shifting momentum towards the transition to renewable energy since its formation in 2014, as an independent regulator and specialized body. Together, these three actors are charged with bringing oversight centricity and mutual cooperation within their respective lines of responsibility to the energy system.

PREPA remains a key player in the island’s electric grid. In the face of intense bankruptcy proceedings and the gradual phase-out of its role as both the owner and operator of grid assets, PREPA still owns about 86% of installed generation capacity on the island, much of which is outdated.16 Compared to an industry average of about 18 years, PREPA’s generation assets have a median age of over 40 years.17 The largest of these power plants are in the south, while the island’s population is concentrated in the north. This makes the grid highly reliant on long-distance transmission lines. Across the island, there are about 2,400 miles of transmission lines as well as 30,000 miles of distribution lines.18

Brief Overview of Puerto Rico’s Electric Utility

Despite the intentions of the Government of Puerto Rico, the current ecosystem under which PREPA, PREB and LUMA operate, does not always align with the priorities of the clean energy transition outlined in Act 17.

As a state-owned monopoly responsible for electricity generation, transmission, and distribution on the island, PREPA developed a variety of operational and fiscal problems that undermined its ability to serve customers and prevented it from actively pursuing Puerto Rico’s target of 100% renewable energy by 2050.19 According to news outlet UtilityDive, the utility suffers from a “lack of effective processes and procedures, inadequate generation management, damaging customer service and collections, politicization of leadership personnel, power theft, poor inventory control, poor procurement practices, an obsolete vehicle fleet, and safety concerns.”20 Further, stakeholders have highlighted concerns with PREPA’s performance in congressional testimony. These concerns cited PREPA’s overpayments for substandard fuel, their high spending on contractors who did not deliver on their contracted work, cuts to workers’ benefits, as well as the workforce, and overall delays to the energy transition.21 22

In 2014, Puerto Rico’s Legislative Assembly passed Act 57, which established PREB as a regulatory body tasked with monitoring PREPA’s performance, reviewing electricity rate proposals by the electric utility, and enforcing the energy policy of the government of Puerto Rico.23 Act 57 also laid the groundwork for the decoupling of electricity generation and distribution in Puerto Rico. Through Act 120 in 2018, the Legislative Assembly established a mechanism for

11

the sale or transfer of PREPA’s generation assets and the concession of its T&D functions – but not ownership – to a private entity. Variations of this approach were first pushed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in the 1990s as part of its efforts to increase competition between power producers and drive down prices, with the success of individual reforms often depending on the strength of oversight by state-level regulators.24

However, Act 120 stopped short of creating a wholesale electricity market to complement the current system of procuring generation capacity and ancillary grid services, via long-term contracts known as power purchase agreements (PPAs). Under the current system, existing power producers have little incentive to invest in lower-cost generation technologies, which has resulted in higher electricity prices for consumers. Act 120 also allowed for the concession of PREPA’s T&D assets and responsibility for their operation and management to just one private entity.25 In other words, although LUMA was required to compete for the right to operate and maintain the T&D system initially, it no longer faces competition from other companies.26 As a result, customers have no alternative if they are unsatisfied with LUMA’s service.

PREPA’s recent actions have not demonstrated a commitment to the vision set forth by Puerto Rico’s Legislative Assembly in Act 17, as its undiversified generation portfolio demonstrates. Earlier this year, PREB stripped PREPA of its authority to conduct requests for proposals (RFPs) for renewable energy projects as required by Act 17 due to the utility’s extreme delays in carrying out the first tranche. The regulator hired an independent coordinator to run the process instead.27 In its most recent integrated resource plan (IRP), PREPA also announced its intentions to continue building fossil fuel infrastructure despite opposition from stakeholders.28

Bankruptcy and the Introduction of the FOMB

On top of the added stress that oversight and implementation inefficiencies place on the energy system, Puerto Rico’s debt crisis has directly impacted grid management, investment and rates charged to all households. For reasons further explored in later sections of this report, PREPA began accumulating a substantial amount of debt beginning in the 1970s. The amount then surged after 1996. By early 2014, the public utility’s operations and finances were clearly struggling.29 That summer, PREPA could no longer afford fuel. By 2016, PREPA’s debt amounted to $9 billion.30 Notably, the rates that Puerto Rican customers pay for their electricity are the primary funding source for bond repayments. 31

In 2016, the U.S. Congress enacted the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA). Since the bankruptcy protections provided to U.S. states were denied to Puerto Rico due to an amendment to federal code in the 1980s, this law provided a debt restructuring process. Additionally, it established the Financial Oversight and Management Board (FOMB) and tasked it with restructuring Puerto Rico’s debt. Officially, FOMB is an entity of Puerto Rico’s government; however, the President of the United States appoints seven members to the Board and the Governor of Puerto Rico designates only one ex-officio member. The Puerto Rico Governor and Legislative Assembly have no control, supervision,

oversight, nor review over FOMB or its activities, and FOMB has the authority to prescribe or halt government decisions.32

This insight presents an important and distinguishing feature of the complexity of institutional oversight involved within Puerto Rico’s energy system, relative to islands with designated statehood such as Hawaii. As this report will discuss in future sections, FOMB’s involvement has profound implications on the level of institutional cooperation and policy alignment needed within the U.S. Federal Government, the Commonwealth and municipal governments in Puerto Rico, as well as between these entities, in order to press forward with Puerto Rico’s renewable energy transition.

Delays to Recovery

The need for quicker recovery from natural disasters, resolution to PREPA’s debt crisis and mismanagement, and improvement of Puerto Rico’s economic environment have played an important role in recent decisions about the island’s energy system. 33, 34 In particular, FOMB’s role in PREPA’s bankruptcy has influenced how federal funding for grid reconstruction has been allocated, and shaped the concession of PREPA’s T&D functions to LUMA.

Federal Funding

Under the Trump administration, federal agencies have pointed to the debt crisis as the primary reason to implement additional constraints on critical funding to Puerto Rico’s grid recovery. On September 9 and September 20, 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) published notices for two separate presidential disaster declarations under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (“Stafford Act”), one for Hurricane Irma and Maria respectively. Both declarations authorized FEMA to provide “such amounts as [found] necessary for federal disaster assistance and administrative expenses.” 35, 36 Following the initial authorization of funds and the presidential declarations in 2017, FEMA applied a revised program for funding disbursement in a manner that was specific to Puerto Rico.

The “Public Assistance Alternative Procedures” model is one that was initially created to impose additional control over spending on permanent work in response to Hurricane Sandy, but was only used for a small fraction of that work. 37 FEMA would use the funding model for all permanent work for the first time, in Puerto Rico. 38 Based on a letter written to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), FEMA instituted this model “due to Puerto Rico’s financial situation, weakness in internal controls, and the large scope of recovery funds, among other things.” 39 Local government and nonprofit leaders have cited this model as a source of delay in funding distribution. 40, 41

According to Pueto Rico’s Central Office for Recovery, Reconstruction and Resiliency’s (COR3) Disaster Recovery Transparency Portal, despite a commitment of $9.4 billion towards the energy grid in 2020, only one project related to grid recovery has been completed using FEMA permanent work funding.42 As of November 17, 2022, when the U.S. House of Representatives Natural Resources Committee held a hearing on rebuilding the Puerto Rican energy grid and recovery efforts after the hurricane, only $184 million of the total $9.4 billion obligated towards permanent work for the energy grid had been

12

disbursed.43 Notably, the funding may be used to update the system to support transmission of electricity generated from renewable energy sources, and to build microgrids. 44, 45

Privatization

The aforementioned factors also helped catalyze the conditions for PREPA’s contract with LUMA. Act 120 allowed for the formation of public-private partnerships to replace parts of PREPA’s monopoly functions, which resulted in the concession of its T&D responsibilities to LUMA.46 The FOMB also played a role in the privatization deal, in that it has been publicly supportive of LUMA and privatization of the grid’s operation. For example, the FOMB advocated for a supplemental contract amending LUMA and PREPA’s original Operation and Maintenance (O&M) agreement. According to the supplemental contract, the primary contract would not commence until after the assigned federal judge approved PREPA’s debt restructuring plan, and LUMA found that restructuring plan to be “reasonably acceptable.” The supplemental contract also increased the fee that LUMA would charge PREPA for O&M during the Interim Period, from the $70 million agreed to in the primary contract’s first year to $115 million during this new period, termed the “Interim Period.” 47, 48

In addition to attracting investors and helping the island emerge from debt, LUMA was also tasked with constructing a more reliable and resilient grid. In the privatization deal, LUMA assumed the authority to determine how to spend PREPA’s revenue and funding from FEMA for rebuilding post-Maria. LUMA set a goal to invest more than $500 million of federal funding for powerline and substation improvements in its first year but has spent less than $35 million so far.49 In response to concerns in the delay, LUMA Chief Executive Officer Wayne Stensby has said that the company did not know the full extent of problems with the grid until it began the rebuilding process. 50

In our conversations with stakeholders, some voiced their support for the privatization of PREPA’s T&D functions based on the assumption that doing so would allow regulators to impose financial penalties, without harming Puerto Ricans. Fining a public entity, meanwhile, would constitute an implicit tax on ratepayers. However, although PREB was granted the authority to impose financial penalties on LUMA for violating certain provisions of its performance-based contract, the Chair of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Natural Resources, Raúl Grijalva, has highlighted that the contract under which LUMA is currently operating, as amended by the supplemental contract, does not appear to include such penalties. In that same hearing, the Governor of Puerto Rico emphasized that the permanent contract with LUMA, which would impose fees, will not begin until PREPA’s debt restructuring is approved. 51

To date, the general public, notable celebrities, non-profits, local legislators, and legislators in the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate, have all raised concerns about LUMA’s operations to date. 52, 53, 54, 55 Commonwealth residents, about 43 percent of whom live in poverty, lengthened blackouts since LUMA took over operation of the T&D system in the summer of 2021. 56 In addition, as of December 2022, Puerto Rico’s citizens had experienced at least seven rate hikes amid increasing blackouts over the course of the year. 57 Further, LUMA also failed to recognize a collective bargaining

agreement with PREPA’s labor union and subsequently displaced many of PREPA’s employees with a new workforce. 58 After Hurricane Fiona, the Huffington Post reported that some municipalities hired former PREPA line workers or depended on other private actors to restore power. 59

In response to criticism, LUMA and their supporters stress the company’s progress in maintaining the grid, as well as the difficulties they face locally. For example, LUMA points to the fact that the company has already installed over 36,500 rooftop solar systems for customers in Puerto Rico. 60 LUMA has also faced challenges in carrying out permanent work on the Puerto Rican grid due to difficulty of staffing and contracting out its work. 61 As of November 30, 2022, PREB approved an extension of LUMA’s current contract. The permanent contract, granting LUMA the right to manage T&D for 15 years, will begin upon the federal court’s approval of the debt restructuring plan for PREPA. 62

Continued Challenges Due to PREPA’s Bankruptcy

PREPA’s debt restructuring remains unresolved as of publishing. Progress towards a settlement still remains stymied by an exclusive mediation process. FOMB, the Puerto Rico Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority, and PREPA have the primary negotiation roles with PREPA’s bond parties. 63 Still, Puerto Rico’s legislature must approve any Plan of Adjustment (POA) and has already rejected the terms of three mediation agreements notably due to proposed rate increases. PREB, which is also excluded from negotiations, is responsible for reviewing PREPA’s proposed rates and ensuring they are consistent with PREPA’s debt repayments and Puerto Rico’s service needs.64

In September 2022, bondholders sought control over PREPA and requested that the U.S. District Court of Puerto Rico dismiss the case or install a receiver who would raise rates.65 Later, on December 16, 2022 the FOMB filed their proposed POA for PREPA’s debt restructuring. According to their website, the POA “proposes to cut PREPA’s unsustainable debt by 48%, to approximately $5.4 billion, and should provide the financial stability necessary to invest in a modern, resilient, and reliable energy system for Puerto Rico.”66

Former Acting New York State Comptroller and now director of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), Tom Sanzillo, evaluated the most recent POA plan and published an official Letter on Puerto Rico Debt Restructuring through IEEFA. In this letter, Sanzillo writes that the POA will severely raise the price of electricity in the next 35 to 40 years.67 However, he further states that the plan “exempts low-income residents from having to pay the majority of the rate increase”. 68 Most importantly, he emphasizes that, “to raise the price of electricity further when it is already among the highest in the nation, and the people are among the poorest in the nation, is not a solution”.69 Thus, Sanzillo notes that raising the price of energy on the remaining 60 percent of Puerto Ricans not in poverty is still increasing energy prices for U.S. citizens that have the least amount of resources to meet those rate hikes. Residents would be forced to cover the cost of past mistakes that were not their own, including local government entities’ mismanagement of finances, and arguably irresponsible lending on the part of bondholders.70 Since energy costs bear the heaviest burden on those that are most

13

financially vulnerable, we need to think critically and long-term about how officials can make that burden lighter.

Given this energy system context, the following section provides a more substantive discussion of our framework for energy justice, and how it underpins the need to alleviate the current economic barriers that exist for LMI communities, and to transition from an economy that has a centralized grid and is heavily dependent on imported fossil fuels.

Section B. The Economic Barriers to Energy Justice

At its core, energy justice ensures that any energy system equitably provides access to energy to all communities, especially the most vulnerable ones. The concept itself also has a restorative property to right the wrongs towards marginalized communities that have been harmed and left behind by the negative externalities of the current energy system.

In Puerto Rico, energy justice is particularly salient as a result of the delayed transition to renewable energy to date, the island’s high susceptibility to rapid climate change, and the natural disasters that have left families and communities across the island devastated, and energy insecure.

A broad range of economic factors contribute to energy insecurity on

the island. For example, the median household in Puerto Rico earns approximately $22,000 annually - less than half the annual income of the poorest state in the continental United States. Further, as stated above, the cost of energy per kWh for residential customers on the island is nearly twice as high as that of states on the mainland. 71 Thus, a larger share of a smaller household budget is typically needed to consume the same amount of energy as most other Americans.

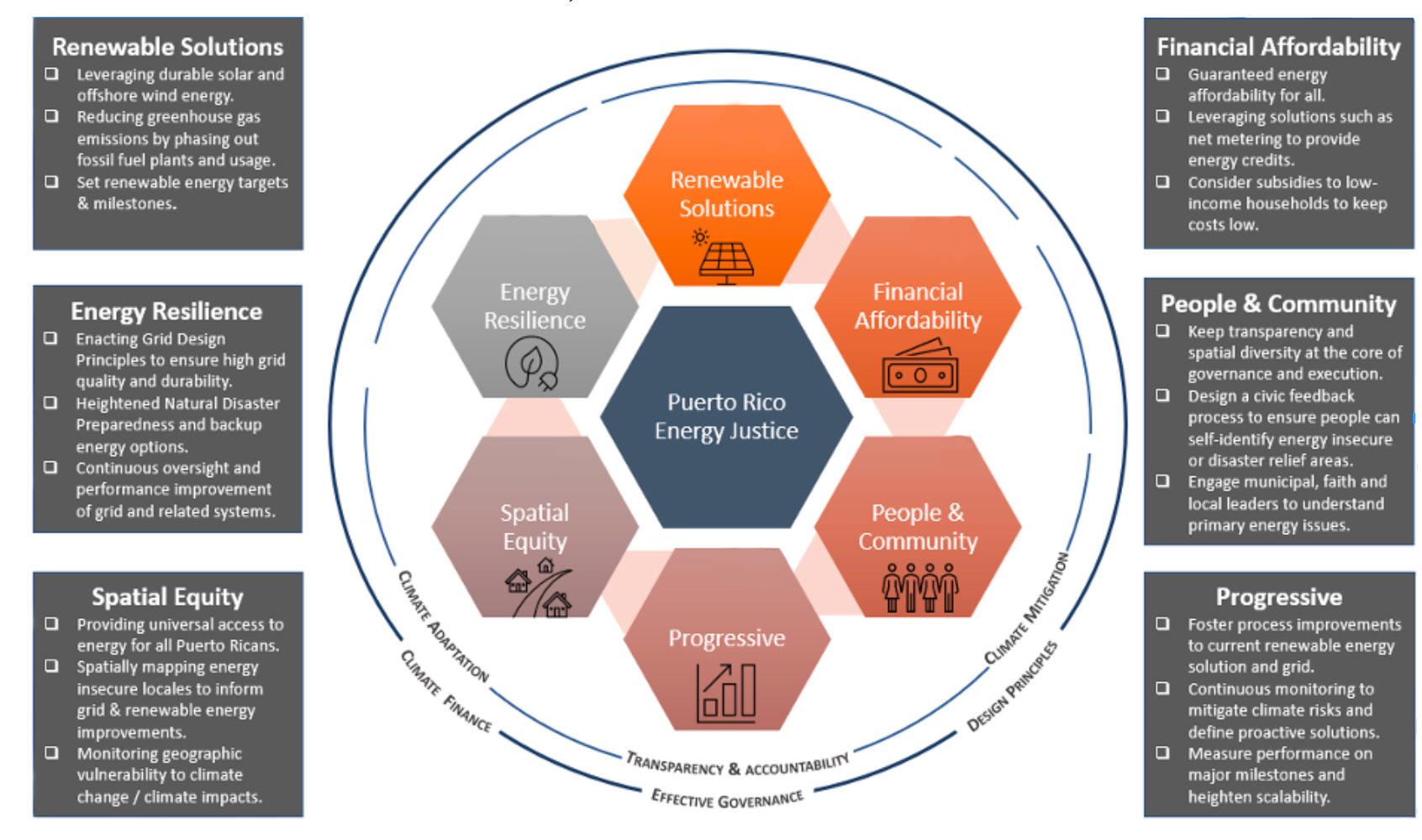

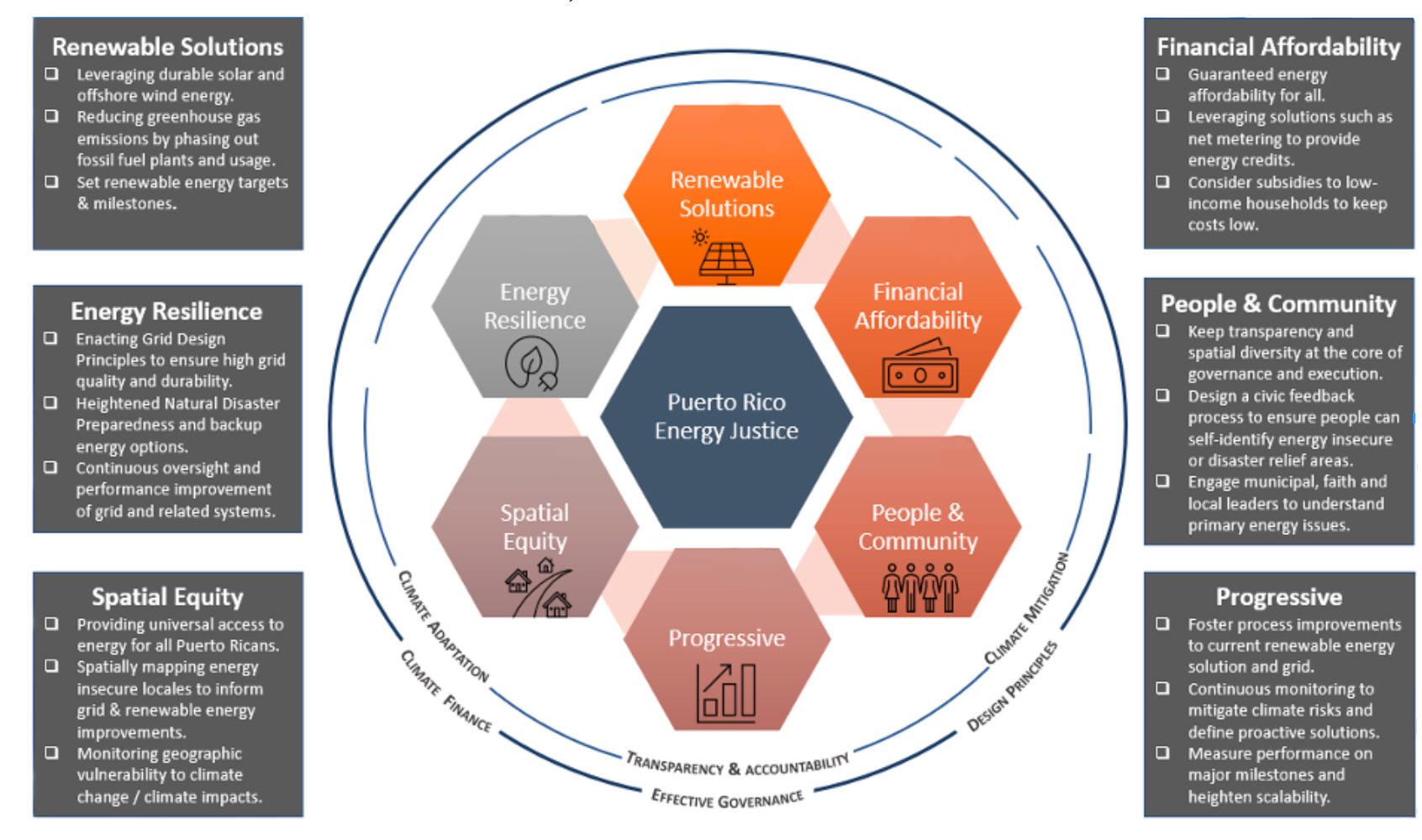

Our energy justice framework for Puerto Rico was developed with the people of Puerto Rico at the center. The framework establishes six factors as integral to substantive energy justice in Puerto Rico for all Puerto Ricans; these factors include: Renewable Solutions, Financial Affordability, People & Community, Energy Resilience, Spatial Equity, and Progressive Oversight. As depicted in the internal body of the circle, these six factors serve as critical drivers to the centricity of energy justice for all Puerto Ricans, and each of its six factors have been strategically mapped in alignment with the seven design principles outlined in the introduction of this report. The first outer ring of the energy justice framework showcases the critical importance of effective climate adaptation strategies, climate mitigation solutions, and transparency policymaking in facilitating effective energy justice. Lastly, the second outer ring demonstrates the imperative need for climate finance, effective governance and the seven design principles outlined in this report, to facilitate structural and systemic change and bring about a 100% renewable energy transition as stated in Act 17.

Energy justice is a journey and not a destination. As such, it is paramount that all stakeholders foster a culture of transparency and accountability in the monitoring and oversight of this endeavor. Further, it is also critical for federal and local government leaders to work in tandem to provide effective governance on this renewable

14

energy transition while being mindful of climate finance, adaptation, and mitigation strategies that can be leveraged in conjunction with grid design principles. Many of the concepts and solutions described here will continue to be discussed in more detail in the succeeding sections of this report.

Above all, this energy justice framework is both designed for and tailored specifically to Puerto Rico. It amplifies a call to action for activists, community members, non-profits, policymakers, and government leaders on to ensure that these factors and principles are being adequately leveraged in the pursuit and achievement of Puerto Rico’s broader renewable energy objectives. The below energy justice framework displays critical factors for a successful energy justice plan that can be used throughout the lifecycle of the island’s renewable energy goals in accordance with Act 17.

With this framework in mind, the subsections following this discussion will describe the challenges to achieving the renewable energy transition, and thus barriers to energy justice Puerto Rico currently faces as a result. The first subsection focuses on the challenges that LMI Puerto Ricans currently face as the island moves towards a renewable energy transition. The second subsection then provides a big picture perspective of the interplay between macrolevel regulatory, economic, and energy factors that have influenced economic development in Puerto Rico, and influence the transition accordingly.

Energy Insecurity Among LMI Communities

In academic literature, “energy insecurity” describes the inability of a household to meet its basic energy needs. Common drivers of energy insecurity are wide-ranging but typically are economic, physical, or behavioral in nature. In the Puerto Rican context, our research

team observed obstacles to sufficient energy access across all three of these areas. Stakeholders should account for these issues in order to keep the most vulnerable Puerto Ricans at the center of the energy transition, actualize energy justice and ensure no one is left behind in the process.

Economic Drivers

While an estimated 3,000 households in Puerto Rico currently transition to rooftop photovoltaic (PV) systems each month, 72 LMI households are the least likely to be part of that number. These households often lack the cash needed to purchase systems outright or the creditworthiness to lease them. The distributional implications for the future are significant, as wealthier households are holistically better equipped to reduce their reliance on PREPA’s generation. By contrast, LMI households that remain fully dependent on the grid will be the ones most exposed to any debt-recovery rates that may be applied as a result of PREPA’s bankruptcy.

Several federal programs aimed at increasing energy affordability are potentially inaccessible to low-income Puerto Ricans. Most incentives for installing PV systems are in the form of federal tax credits. However, residents of Puerto Rico do not pay federal taxes and therefore have no way of making use of these credits. Further, rural and suburban LMI households often struggle with issues related to land titling. This can make it difficult to access assistance through the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which requires that applicants provide proof of address, described as either an active lease or mortgage. To make matters worse, while some U.S. jurisdictions offer shut-off protection for specific customers for whom a loss of electricity poses an immediate threat to life, Puerto Rico is not currently one of them. This leaves many households, especially those that have health ailments, in Puerto Rico highly susceptible to lower quality of well-being and economic mobility overall.

15

Behavioral Drivers

Even so, various behavioral dimensions of energy insecurity intersect with the economic dimensions. The most natural case is self-regulation where LMI households, aware of their budgetary constraints, consume less energy than they need in order to keep their monthly bill within an affordable range. With air-conditioning being a large energy consumer for many households, this self-regulation can mean exposure to summer temperatures of up to 110 degrees with only limited usage of one’s cooling system. Self-regulation can also be detrimental at an individual and household level when at least one person has a health condition that is reliant on machine technology to support their health care, treatment regimen and/or survival. While heat-related injuries and fatalities are often difficult to identify, research does suggest that a warming climate has had a role to play in these occurrences, particularly in San Juan. 73

Communities that are struggling with the price of energy may also resort to illegal connections to the grid in order to avoid costs. This contributes to a state of energy insecurity as these households are subject to disconnection and law enforcement action at any time and may face criminal fines and penalties when the irregularity is detected. This compounds their household costs and adds to their existing financial constraints as a result of energy desperation. The Center for a New Economy estimates that as much as 15% of the power PREPA generates cannot be accounted for, mostly due to illegal connections.74 The costs of PREPA’s energy losses are largely recovered from paying customers through surcharges - spurring a cycle that continues to negatively impact those ratepayers with the least ability to pay.

Physical Drivers

Physical factors also play a major role in energy insecurity for many Puerto Ricans. Spatial inequality in particular is deeply rooted and present across Puerto Rico’s many municipalities, which further hinders the effectiveness of the current energy system. Through their platform ArcGIS Storymaps, the company Esri publishes geospatial maps and findings based on spatial data leveraged in their GIS tool. In an ArcGIS Storymap authored by Amelia Ward on Poverty in Puerto Rico, she uses public U.S. data on household income in Puerto Rico, Water Environment Federation (WEF) reporting on climate vulnerability, and Center of American Progress findings, to construct a comprehensive report on the poverty picture in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. In this report, Ward writes:

“The presence of spatial inequality clearly revealed itself post-hurricane, considering the degree of impacts on populations with different income levels, due to the unequal distribution of wealth and the lack of access to necessary public goods in certain spaces. The hurricane demolished the majority of Puerto Rican infrastructure, including a large number of public and assisted housing projects. The inevitable destruction of these projects left thousands and thousands of residents without shelter or resources”. 75

With regards to energy, it took 11 months for power to be restored to all customers across the island after Hurricane Maria. When Hurricane Fiona struck the island in September 2022, the entire energy grid was disabled once again, and it took several weeks for

power to be substantially restored across the island. 76 Stakeholders noted particularly long outages for those residing in the island’s mountainous interior. Outages were further compounded for communities like Utuado that already struggle with road accessibility. 77 In the absence of power for long periods of time, remote communities often rely on alternatives such as kerosene oil, candlelight, or wood fires to meet their energy needs - all of which carry either risks of carcinogen exposure 78 or represent potential fire hazards. 79

Coastal communities are also particularly energy insecure because of their heightened vulnerability during extreme weather events. While communities in each of the island’s major metropolitan areas – San Juan, Ponce, and Mayaguez – fall into this category, there is also typically greater local capacity to access aid in these cities in the aftermath of the event. On the other hand, smaller coastal towns like Salinas 80 and Loiza 81 are largely dependent on the government of Puerto Rico or the federal government for relief when disasters strike. While emergency personnel are usually able to respond more quickly to these low-lying areas than those in the interior, even short power outages can turn into fatal events for the elderly or the disabled, who may depend on powered medical devices to live.

According to the Initiative for Energy Justice (IEJ), a potential policy solution is to promote affordable access to renewable energy to every single person through decentralized structures. The IEJ considers three utility structure options that could support making energy affordable including: community choice aggregation, mechanisms to financial credit individuals’ bills (net metering), municipal utilities, integrating other innovative players and approaches into the market. While such policy interventions are important, they alone cannot accomplish the goal of long-term energy sustainability and affordability.82 Other mechanisms are needed.

As stated previously, the threat that climate change imposes on the island further compounds physical concerns. Puerto Rico faces significant challenges from climate change and natural disasters in the coming decades that will affect its energy system. Climate projections indicate that Puerto Rico will experience increased temperatures, decreased precipitation, and rising sea levels over the next 25 years.83 These changing climate patterns will impact consumer demand for electricity (e.g., air conditioning use), the island’s renewable energy resource potential (e.g., hydroelectric generation may be influenced by changing rainfall and drought patterns), and existing generation assets (e.g., some power plants are located less than six feet above sea level and less than 160 feet from the shoreline).84

Energy and Economic Development in Puerto Rico

The problems of economic development and energy security in Puerto Rico are not mutually exclusive. Many of the obstacles facing the energy system in Puerto Rico involve issues of redistribution, access to energy, a lack of renewable energy, exposure to the impacts of climate change, financial costs, and the utility’s operational and financial challenges. These factors have each contributed to and are a cyclical result of Puerto Rico’s nonlinear economic development path. The existing reinforcement mechanism between Puerto Rico’s economic development trajectory and current energy crisis must

16

be synthesized and evaluated in order to execute an energy justice strategy capable of supporting it.

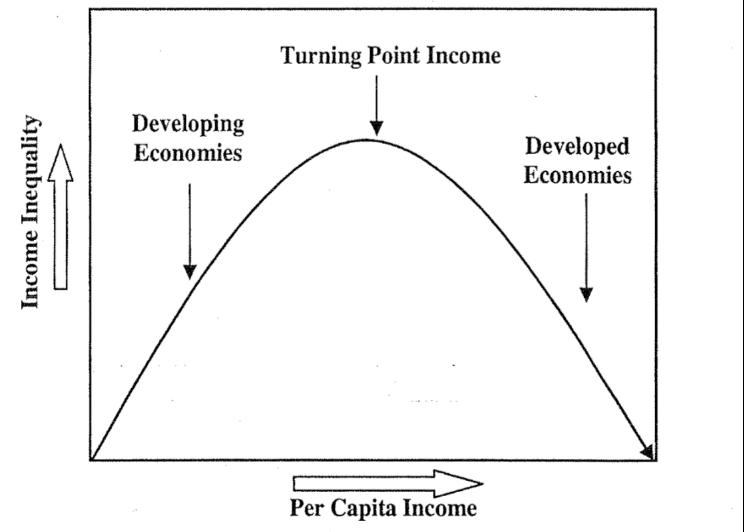

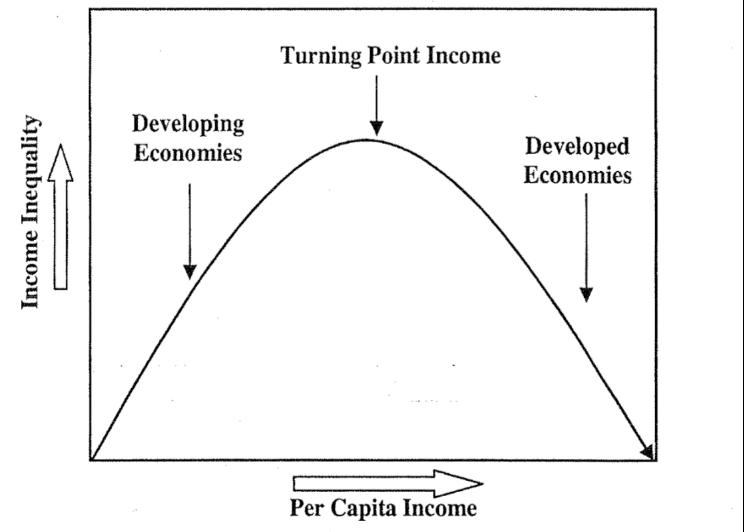

Theory of Economic Development

The late-economist and Nobel prize awardee, Simon Kuznets, hypothesized that as an economy develops, market forces first increase and then decrease the overall economic inequality of the society, which is illustrated by the inverted U-shape of the Kuznets curve in Figure 1.85 Put differently, greater economic development overtime leads to greater economic equality overtime. The curve in Figure 1 implies that as a society industrializes, the center of the economy shifts from rural areas to cities and rural laborers, such as farmers, begin to migrate and seek out better-paying jobs. This migration, however, results in decreasing rural populations in favor of increasing urban and suburban populations. 86 From a development standpoint, this would move traditionally agrarian economies to becoming more industrial in nature, and thus creating economies of scale. Figure 1 demonstrates this transition to a developed economy and thus lowered income inequality at a certain turning point threshold. 87 According to the theory, this is why many Western European countries do in fact have high per capita incomes and lower levels of inequality. Equally, the theory states that this inverse relationship between income inequality and per capita income will be consistent across developed economies.

Conversely, this is not the reality of Puerto Rico and is also not the reality facing the United States. As the theory goes, with higher average income per capita, economic inequality is expected to decrease when a certain level of average income is reached and the processes associated with industrialization, such as democratization and the development of a welfare state, will take hold. 88 However, while per capita income has increased over time, Puerto Rico’s economy has also been plagued by increasing levels of inequality. 89 In fact, as cited by Harvard University, Puerto Rico has higher income inequality levels than some of the poorest states in the United States. 90

The fact that the end-state of Kuznets’ theory does not hold and increased economic development is leading to increased inequality insinuates that there are additional mechanisms driving this inequality outside of income. More importantly, this trend defines a greater need for pure redistribution focused social justice. In his book, The Economics of Inequality, Thomas Piketty states that the “Kuznets curve is the product of a specific and reversible historical process. The inversion of the Kuznets curve spelled an end to the notion that there was a grand historical law governing the evolution of inequality at least for a time. In pure redistribution, redistribution is justified by considerations of pure social justice rather than by any supposed market failure”. 91

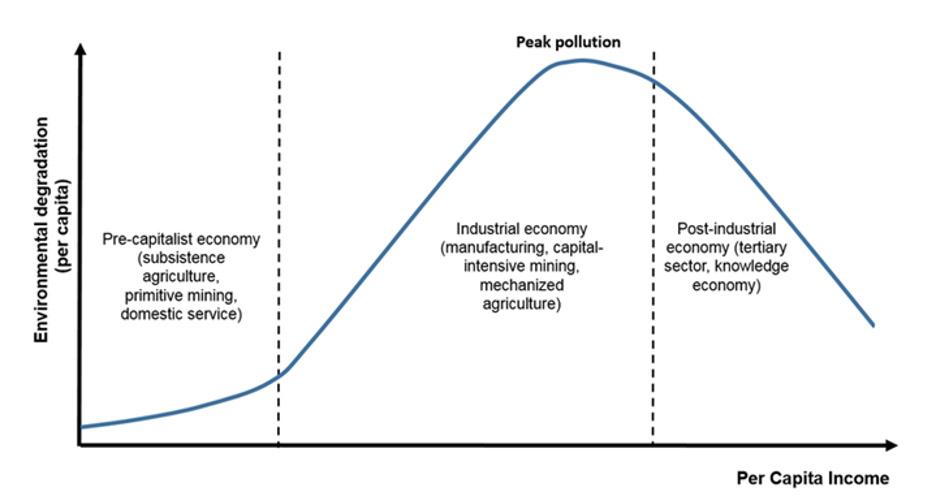

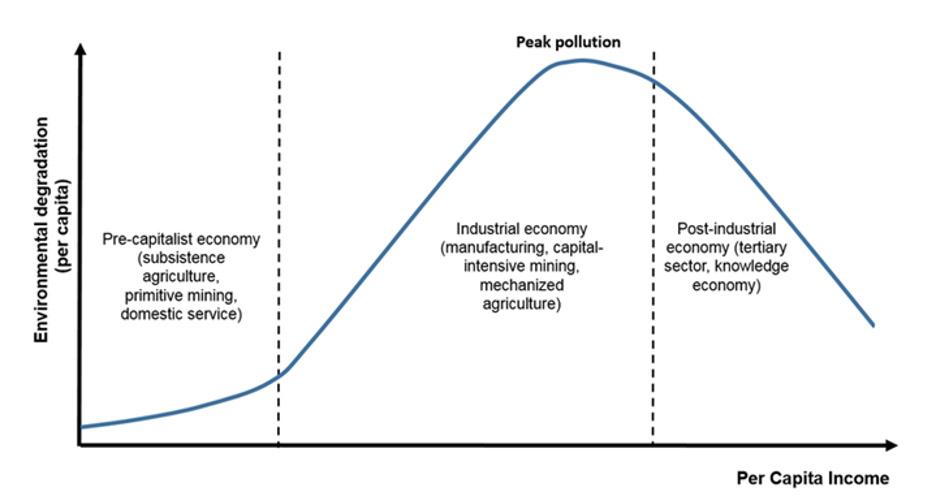

Piketty’s finding is especially applicable when examining Kuznets related environmental curve. The environmental application of the Kuznets Curve, shown in Figure 2, implies with similar logic that as an economy develops pollution emissions decrease overtime, bettering environmental quality and supporting economic growth. This also implies that in the early stages of development pollution emissions increase and environmental quality declines. Notably, this trend reverses beyond the turning point threshold of per capita income (which will vary for different indicators) so that economic

growth leads to environmental improvement at high income levels.92 Contrary to this model, worldwide and particularly in Puerto Rico we are witnessing increasing income per capita with high levels of inequality on top of higher levels of pollution emissions. 93

Puerto Rico’s deviation from both the traditional and environmental Kuznets model is significant because the model portrays the ideal state of what should be taking place in the absence of market or government failures. This insinuates that similar to Piketty’s view, both redistribution to promote equitable access to energy, and energy justice will be critical to correcting the inequalities witnessed from both an energy and economic perspective. Since energy and the economy are intertwined in Puerto Rico, energy justice would suggest that despite the presence of a renewable energy mandate, the factors necessary to remove the economic and access barriers that exist within the energy system are likely the same ones that are poorly understood causally and are left out in policy. A lack of understanding of and action to alleviate these economic barriers to energy justice will likely come at the expense of the overall effectiveness and completion of the renewable energy mandate.

The Economic Impact of the Jones Act on The Energy Sector

As referenced earlier in this section, a critical component to energy justice is establishing energy resilience through grid design and infrastructure, as well as the development of renewable energy solutions. Often fostering energy resilience and harnessing renewable energy requires a large supply of resources. Any barriers to accessing these energy resources, would impede renewable energy goal attainment. As discussed in Section A, the current energy system in Puerto Rico relies heavily on fossil fuels to power many of Puerto Rico’s homes. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s (EIA):

Puerto Rico has no proved reserves or production of fossil fuels. The Commonwealth has some renewable resources in the form of solar, wind, hydropower, and biomass, but relies primarily on imported fossil fuels to meet its energy needs. Puerto Rico consumes about 27 times more energy than it produces. Petroleum accounts for about two-thirds of the Commonwealth's total energy use, while natural gas accounts for one-fifth, coal for about one-tenth, and renewables account for the rest. 94

While Puerto Rico imports the vast majority of its energy resources, a federal law referred to as “the Jones Act” restricts the market supply available to Puerto Rico. 95, 96 In 1920, Congress passed this law, initially titled “the Merchant Marines Act,” which has since been called the Jones Act after its primary author. Among other things, the law established labor protections for workers on U.S. cargo ships, and required all goods shipped between two ports within the territorial U.S. to move only on U.S.-built ships, with a U.S.-citizen crew.97, 98 A key consequence of this law is that foreign ships cannot unload part of their shipment at one U.S. port, and then unload once again at another port. Thus, the law makes it less profitable for foreign ships to dock at smaller markets like Puerto Rico, as well as Hawaii, Alaska, and select U.S. territories for which the law has not been waived.

Instead, foreign ships will unload their cargo at destinations with

17

larger markets in the mainland. The goods destined for the by-passed areas will then be placed on U.S. ships, and the ships will deliver the goods to those destinations. The indirect movement of goods, in combination with the higher cost of shipping within the U.S., makes imports more costly and difficult for these areas to access in general and in a timely manner. 99

As a direct effect on energy insecurity in Puerto Rico, the Jones Act creates conditions where the island has more limited access to the international market for energy resources, while facing increased costs for oil imports in the domestic market than other islands in the region.100 Based on EIA’s energy profile on the island, only Alaska and Hawaii had higher energy prices than Puerto Rico, when compared to all U.S. states. 101

The Jones Act also cultivates more severe conditions for energy insecurity, by indirectly hampering the Puerto Rican economy. As

discovered in a 2016 report written by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “while causality from the Jones Act has not been established,” due to a lack of comprehensive analyses on its impact, “it stands to reason that the Act is an important contributor insofar as it reduces competition (shipments between the island and the U.S. mainland are handled by just four carriers)”. 102 The authors conclude that while the magnitude is unclear, the Jones Act’s impact on the Puerto Rican economy is negative.103

There are multiple territories that have either full or partial exemptions for goods imports under the Jones Act. Those with full exemption include the U.S. Virgin islands, American Samoa, and Northern Mariana islands. Guam and the town of Hyder, Alaska have partial exemptions. As the New York Bar writes “Puerto Rico is the only non-contiguous territory not wholly or partially exempt.”104

For that reason, the high cost of energy is not simply a consequence

Figure 1. Original Kuznets Curve

Figure 1. Original Kuznets Curve

18

Figure 2. Environmental Kuznets Curve

of Puerto Rico being an island, nor is its struggle with energy exclusively due to mismanagement in the energy sector. The fact that Puerto Rico imports the majority of its energy, and does so under a federal law that imposes restrictions on imports to Puerto Rico, are key contributors to the island’s struggle in energy and economic development.

Puerto Rico's Historical Focus on LMI Communities & Prior Renewable Energy Transition

Even if Puerto Rico were granted a full or partial exemption from the Jones Act, continued dependence on imports of fossil fuels would still contribute to energy insecurity on the island. A transition to renewable energy – energy sources that are domestically produced – would help to alleviate this burden. Yet, as referenced in the prior section regarding the disparity in rooftop solar adoption rates between income classes, the current market structure will not provide a guaranteed path for LMI Puerto Ricans in the transition.

Additionally, the Commonwealth’s history provides critical insight that this isn’t the island’s first attempt to leverage renewable energy solutions nor has it always been this complex. In the early 20th century, Puerto Rico also faced conditions of economic distress, disrepair in infrastructure, and heavy reliance on fossil fuels. Through a combination of local and federal efforts, the island was able to transition to increased reliance on renewable energy, with its most energy-insecure communities at the center of that transition. The work, led and carried out primarily by Puerto Rican engineers and scientists, could inform future federal and local action in the current transition.

According to PREPA’s review of Puerto Rico’s energy history, in the early 1900s, Puerto Rico primarily derived its energy from “thermal power stations and imported oil.”105 Three private companies held the majority of market power of the water and electrical system. One was Puerto Rican-owned, another Canadian-owned, and the last mainland-U.S.-owned.106 Notably, in this period it was not profitable for the private sector to connect remote areas of the island to the electrical grid.107, 108 As an apparent consequence of this, while rural residents in Puerto Rico made up more than 70 percent of the island’s population, the majority of the rural population had no access to electricity up into the 1930s.109

Additionally, before this energy transition, Puerto Rico endured a series of economic and natural disasters. In 1928 and 1932, the island faced two devastating hurricanes: San Felipe and San Ciprián.110, 111 Between those years, the economic consequences of the Great Depression hit the island hard. Multiple Puerto Rican businesses fell into bankruptcy, and by 1932, the Puerto Rican government was nearing its legally-established limit on its ability to borrow.112

In response to these challenges, the Roosevelt administration initially established a relief program in 1933, and in 1935, replaced it with a more robust New Deal entity called the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration (PRRA). Created under Executive Order #7075, the PRRA’s mission was to comprehensively alleviate negative pressures of the economy through public works, with a primary focus on increasing employment.113, 114 The administration moved the PRRA

headquarters to Puerto Rico, and hired well-known scientist and Chancellor of the University of Puerto Rico, Carlos Chardón as Regional Administrator.115, 116 Using funding from a series of Emergency Appropriations Acts signed into law from 1935 to 1938, the program spent a total of $1.36 billion in current dollars on labor and public works projects between 1935 and 1955. About half of the funding went to labor, and the other half to public works projects. The PRRA’s Rural Electrification Program is seen as a particular success among its public works programs. 117

The Rural Electrification Program, heavily staffed by Puerto Rican engineers, and led by Puerto Rican engineer Antonio S. Lucchetti Otero, constructed seven hydroelectric systems within Puerto Rico’s central mountainous region.118 Notably, cement produced on the island, from a PRRA-constructed cement plant, helped to create these major works.119 Thus a domestically-produced, lowercost input, facilitated this form of energy infrastructure. Puerto Rican laws passed prior to this period also facilitated hydroelectric infrastructure development. As PREPA writes, laws were passed in 1924 and 1925, “providing funding for the research, construction and operation of hydroelectric projects.”120 The laws also provided a path to data collection and hydrographic studies for the island. 121

As one scholar writes, by 1946, over 40 percent of the island’s energy was derived from hydroelectric plants.122 In the first half of the 20th century, Puerto Rico had alleviated energy insecurity in underserved regions of the island and also managed to surpass the 2025 goal proscribed by Act 17 in 21st century terms. As history proves, a consistent and gradual transition to renewable energy is not impossible in Puerto Rico. However, it is important to ensure that regardless of which renewable energy solutions or mechanisms are pursued, that the transition itself is sustainable in the long-term in Puerto Rico.

Energy, Rapid Industrial Growth, and Ensuing Instability

Puerto Rico’s history also teaches important lessons learned in the energy space as it conveys how economic forces, both within and outside of Puerto Rico's control, impacted the island's energy trajectory. Unfortunately, in the course of Puerto Rico’s development, many hydroelectric plants fell out of use, due to the island’s transition back to a fossil-fuel based economy. Under the precursor to PREPA – which had purchased all the three companies holding an oligopoly over the energy system by the early 1940s – construction, ownership of and reliance on fossil-fuel-based facilities began to grow once again in the mid-20th century. PREPA writes that the low price of oil at the time was a prime contributor to increased fossil fuel use for generation. A drought in the mid-1940s, and the need to ration energy use as a result, also caused concern regarding heavy reliance on hydroelectric plants. 123, 124

Moreover, Governor Luis Muñoz Marín’s economic development plan for Puerto Rico, “Operation Bootstrap,” pushed to shift the island from an agrarian-based economy to one based in manufacturing.125 Thus, there was a need for cheap, scalable energy to support the island’s rapid industrialization.

The cost of oil did not remain low for long, and the consequences were felt in Puerto Rico. As a U.S. DOE report from 1982 noted,

19

“since 1973, the economic impact of rapidly rising world oil prices has been particularly severe on the U.S. territories, the Trust Territory of the Pacific islands and the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.” At the time of that report, 97 percent of Puerto Rican energy came from petroleum.126 Yet the continued industrialization on the island, to which protective tax laws and international trade conditions contributed up until the 1990s, appears to have provided sufficient energy demand to partially offset the increased costs.

Starkly contrasting its more recent financial struggles, Puerto Rico’s economic growth bested its neighbors and most Latin American countries in the early 1990s.127 Puerto Rican and U.S. corporate tax exemptions, active in the late 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, are seen as spurring the Puerto Rican industrial base.128 Still, 1976 amendments to the U.S. Internal Revenue Code are further credited with growth in manufacturing. This latter federal law, referred to as Section 936, exempted corporations from paying federal taxes on revenues repatriated from Puerto Rico and attracted scores of big pharmaceutical, petrochemical, and tech manufacturers. Though the long-term sustainability of the tax break was seen as questionable, its impact is believed to have led to an increase in GDP by approximately 38%, the likes of which would’ve taken an estimated 10-year growth trajectory to produce. Further, local government leaders were able to use corporate revenue held in local banks as capital for development projects.129

By 1996, the federal corporate credit began to phase out as leaders started to associate the provision with high costs and low job creation.130 Furthermore, many Puerto Rican government officials in favor of statehood wanted to eradicate the provision because of the uniformity clause of the US Constitution, which disallows any one state from having tax benefits that other states lack. In their estimation, so long as Puerto Rico allowed for this provision, the

island would be held as a territory and could never petition for statehood. Coupled with passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), as well as increased labor, location and market supply competition for key Puerto Rican sectors following the U.S. entrance into the World Trade Organization, the loss of tax benefits led companies to flee the island and caused a major contraction in Puerto Rico’s industrial sector.131 The island’s higher levels of energy and import costs also likely contributed to industry relocation, in the new international trade and domestic tax environment.

With a smaller industrial base, and increasing costs of crude oil, the economic environment imposed a strain to the energy sector. To make up for the enormous loss in revenue, government leaders started issuing bonds at astronomical rates. Public corporation debt in particular had begun to climb sharply in the early 1970s, then steadily through the 1980s. However, the initial increase in the rate of public corporation debt accumulation was low in that period, when compared to the rate of accumulation post-1996.132

In the meantime, employment began to decline, first in the manufacturing sector starting in 1996, then followed by the public sector in 2010, after the Great Recession. In particular, the government of Puerto Rico embarked upon a period of unprecedented austerity, closing over 300 public schools, reducing the University of Puerto Rico system of education by 50%, and laying off thousands of public sector workers.133

The rapid deindustrialization by the private sector and the prolonged period of austerity still informs many Puerto Ricans’ sentiments about how private companies are utilized in the public domain. Many Puerto Ricans harbor suspicion of private firms’ involvement in the facilitation of public goods, especially energy, as a result of a lack of transparency and the past results left by private organizations on

20