Increase funding for United Nations trainings on environmental agreement implementation

The United States should encourage the United Nations General Assembly or other interested parties to support increased training of claimant states on implementation of existing multilateral environmental agreements.

The United Nations Institute for Training and Research offers an online, self-paced, four-part course on International Environmental Law to improve the legal literacy of lawyers and policymakers, and to build local ability to implement multilateral environmental agreements, including those relevant to the South China Sea.83 Price and language, however, present access challenges. The training costs $800 per person, which approximately equals the median monthly income of a Filipino worker.84 It is also currently offered only in English.

For the next budgetary cycle, Washington should seek to expand the training institute’s annual budget and to earmark as little as $24,000 of those funds to cover training for ten individuals each from Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.85

The high cost of overfishing more than justifies this investment. If the U.S. representative at the training institute meets resistance, the European Union could present an attractive option for supplementary funding in this area. The United Nations General Assembly, relevant bodies in the international community, or the United States should also fund translation of the course in Vietnamese and Indonesian.

While many lawyers in the Philippines and Malaysia already speak English, translation of the course into Vietnamese and Indonesian would make it more accessible to lawyers from those countries. Legal education alone will not solve implementation challenges in the South China Sea, especially in cases where litigation is used aggressively as “lawfare.” However, increasing the baseline of shared knowledge across the region will make it easier for countries to cooperate and communicate on multilateral environmental treaties and multi-jurisdiction cases.

30

IV. Conclusion

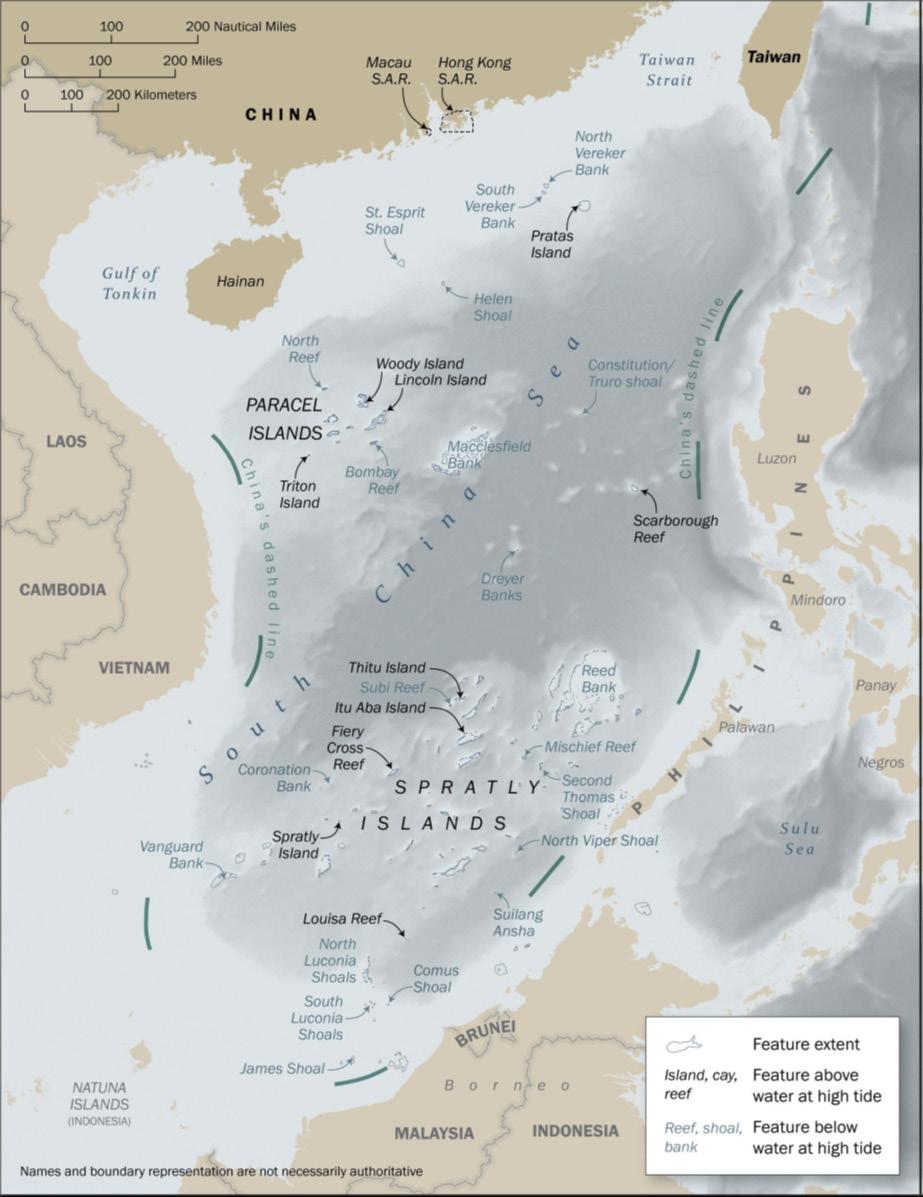

Increasingly aggressive Chinese behavior in the South China Sea calls for a coherent U.S. strategy to meaningfully protect U.S. interests in the region without triggering unwanted escalation. This report proposes that the United States adopt an environmental management approach to promote U.S. interests in the region. By leveraging responsible environmental management to: (1) build claimant state capacity to enforce existing environmental regulations within their territorial waters, and (2) increase cooperation among claimant states in Southeast Asia, the United States can bolster international law and safeguard freedom of navigation throughout the Indo-Pacific.

An environmental approach alone cannot overcome collective action problems and longstanding barriers to cooperation among U.S. allies and partners in Southeast Asia. However, in the context of simmering tensions between claimant states, environmental management provides a less controversial avenue for fostering cooperation among Southeast Asian nations. These efforts can advance the U.S. interest in a free and open Indo-Pacific in the short term, while paving the way for increased U.S. security cooperation with regional allies and partners in the long term.

31

Authors

Allison Blauvelt

Allison worked at Deloitte Financial Advisory services, where she conducted commercial intelligence analysis. She has a B.A. in International Studies from American University and is an MPA candidate at Princeton.

Matthew Fiorelli

Matt is an active duty Army officer and most recently commanded an Attack Aviation Company at Fort Campbell, Kentucky. As an MPA candidate at Princeton, his studies focus on American government and American foreign policy.

Alisa Laufer

Alisa has worked in support of the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Senate, and several NGOs and think tanks. She is currently an MPA candidate at Princeton, where she studies international relations with a focus on the evolving nature of conflict.

Jacobo

McGuire

Jacobo worked with the Millennium Challenge Corporation and Peace Corps before beginning his Princeton MPA. His studies at Princeton focus on technology policy and international development.

Wyatt Suling

Wyatt previously served in the Missouri Attorney General’s Office, where he helped lead its sexual assault kit reform initiative. He holds a B.S. in economics and a B.A. in policy studies from Syracuse University and studies defense policy and strategy at Princeton University.

Samantha Emmert

Sam worked at Global Fishing Watch, a nonprofit that utilizes satellite data and machine learning to improve ocean management, and Oceana, an ocean conservation advocacy organization. She studied biology at Duke University and is an MPA candidate at Princeton.

Benjamin Jebb

Ben is an active duty Army officer who led a Special Forces Detachment at Fort Lewis, Washington before starting graduate school. He is currently an MPA candidate at Princeton, where he studies international relations with a focus on Asia.

Luke Maier

Luke is a graduate student at Princeton University focusing on international relations and economics. Prior to coming to Princeton, Luke studied grand strategy and environmental science at Duke University.

Jennifer Shore

Jennifer is an MPA candidate studying international relations at Princeton University’s School of Public and International Affairs. She was previously a fellow at the White House National Economic Council during the Obama administration.

Ellen Swicord

Ellen is an MPA candidate at Princeton University studying international relations. She previously was Research Associate for Korea Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. She holds a B.A. in political science from the University of Chicago

32

Endnotes

1 Gregory Poling, On Dangerous Ground (Oxford University Press, 2022), p. 12.

2 Encyclopedia Britannica, South China Sea, https://www.britannica.com/place/South-China-Sea/.

3 Kent Harrington, “Commentary: South China Sea may run out of fish at this rate of overfishing,” Channel News Asia, February 5, 2022, https://www.channelnewsasia.com/commentary/south-china-sea-china-environmental-ecological-damage-coral-reefs-overfishing-international-law-2469871/.

4 Council on Foreign Relations Global Conflict Tracker, “Territorial Disputes in the South China Sea,” May 4, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/territorial-disputes-south-china-sea/.

5 U.S. Embassy in Laos, “Statement by Secretary Michael R. Pompeo, U.S. Position on Maritime Claims in the South China Sea,” July 21, 2020, https://la.usembassy.gov/statement-by-secretary-michael-r-pompeo-u-s-position-on-maritime-claims-in-the-south-china-sea/.

6 The White House, “2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/ uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf/.

7 Kenneth G. Lieberthal, “The American Pivot to Asia,” Brookings, July 28, 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-american-pivot-to-asia/.

8 FPRI: Asia Program, Foreign Policy Research Institute, “From Pivot to Defiance: American Policy Shift in the South China Sea,” August 31, 2020, https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/08/from-pivot-to-defiance-american-policy-shift-inthe-south-china-sea/.

9 Dzirhan Mahadzir, “Esper: U.S. Will ‘Keep up the Pace’ of South China Sea Freedom of Navigation Operations,” USNI News, July 22, 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/07/21/secdef-esper-u-s-will-keep-up-the-pace-of-south-china-seafreedom-of Navigation-operations/.

10

11

The White House, “Quad Joint Leaders’ Statement,” May 24, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/05/24/quad-joint-leaders-statement/.

Ian Johnson, “Biden’s Grand China Strategy: Eloquent but Inadequate,” Council on Foreign Relations, May 27, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/biden-china-blinken-speech-policy-grand-strategy/.

12 Jon Bateman, “Biden Is Now All-in on Taking out China,” Analysis Section, Foreign Policy, October 12, 2022, https:// foreignpolicy.com/2022/10/12/biden-china-semiconductor-chips-exports-decouple/.

13 Victor Cha, Complex Patchworks: U.S. Alliances as Part of Asia’s Regional Architecture, Asia Policy, 2011, p. 34.

14 ISEAS, “Southeast Asia Climate Outlook: 2021 Survey Report,” Climate Change in Southeast Asia Programme at ISEAS, November 14, 2022, p. 12, https://www.iseas.edu.sg/.

15 The White House, “2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/ uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf/.

16 Sumaila Rashid et. al., “Sink or Swim: The Future of Fisheries in the East and South China Seas,” ADM Capital Foundation, 2021, https://www.admcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Sink-or-Swim-Full-Report_171121.pdf/.

17 Ibid.

18

Pratnashree Basu, “In Deep Water: Current Threats to the Marine Ecology of the South China Sea,” Observer Research Foundation, March 8, 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/research/in-deep-water-current-threats-to-the-marine-ecology-of-the-south-china-sea/.

19 Reuters Staff, “China ‘Seriously Concerned’ by Philippine’s Building in South China Sea,” Reuters, March 27, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-southchinasea-philippines/china-seriously-concerned-by-philippinesbuilding-in-south-china-sea-idUSKBN0MN0SL20150327/.

20

John McManus, “Offshore Coral Reef Damage, Overfishing, and Paths to Peace in the South China Sea,” International Journal of Marine Coastal Law 32 (2017); Ben Dolven et. al., “Chinese Land Reclamation in the South China Sea: Implications and Policy Options,” Congressional Research Service, June 18, 2015, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R44072.pdf/.

21 Ben Dolven et. al., “Chinese Land Reclamation in the South China Sea: Implications and Policy Options,” Congressional Research Service, June 18, 2015, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R44072.pdf/.

22 Pratnashree Basu, “In Deep Water: Current Threats to the Marine Ecology of the South China Sea,” Observer Research Foundation, March 8, 2021, https://www.orfonline.org/research/in-deep-water-current-threats-to-the-marine-ecology-of-the-south-china-sea/.

23 Ibid.

24 Gregory Poling, “Illuminating the South China Sea’s Dark Fishing Fleets,” CSIS, January 9, 2019, https://ocean.csis.org/ spotlights/illuminating-the-south-china-seas-dark-fishing-fleets/.

25 Ibid.

26 Hongzhou Zhang, “Fisheries Cooperation in the South China Sea: Evaluating the Options,” Marine Policy 89: 67-76, doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2017.12.014/.

27 Keith Johnson and Dan De Luce, “Fishing Disputes Could Spark South China Sea Crisis,” Foreign Policy Magazine, April 7, 2016, https://foreignpolicy.com/2016/04/07/fishing-disputes-could-spark-a-south-china-sea-crisis/; Elena Bernini, “Chinese Kidnapping of Vietnamese Fishermen in the South China Sea: A Primary Source Analysis,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, September 14, 2017, https://amti.csis.org/chinese-kidnapping-primary-source/.

28 The White House, Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States, February 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf/.

29 The White House, Memorandum on Combating Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing and Associated Labor Abuses, June 27, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2022/06/27/memorandumon-combating-illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-fishing-and-associated-labor-abuses/.

U.S. Interagency Working Group on IUU Fishing, “National 5–Year Strategy for Combating Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing, 2022-2026,” https://media.fisheries.noaa.gov/2022-10/2022_NationalStrategyReport_USIWGonIUUfishing.pdf/.

31 The Sea Around Us, “Catches by Taxon in the Waters of the Philippines,” Sea Around Us, November 19, 2022, http://www. seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez/608?chart=catch-chart&dimension=taxon&measure=tonnage&limit=10/.

32 AIS is a tracking system that broadcasts vessels’ identity, location, and heading. It is mandated by the International Maritime Organization for ships over 300 tons and on international voyages. Source: International Maritime Organization, “Automatic Identification System,” https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/AIS.aspx/.

33 VMS is a technology similar to AIS mandated by some national governments to complement AIS. Source: Gregory Poling, “From Orbit to Ocean: Fixing Southeast Asia’s Remote Sensing Blind Spots,” Naval War College Review, Vol. 74, No. 1, Art. 8, 2021; Oceana, “Vessel Monitoring Technology Can Save Fishers’ Lives, Make Fisheries Transparent,” September 22, 2017, https://ph.oceana.org/press-releases/vessel-monitoring-technology-can-save-fishers-lives-make-fisheries/.

34 Ibid.

35 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Fisheries Administrative Order No. 266 Series of 2020 promulgating the Rules and Regulations on the Implementation of Vessel Monitoring Measures (VMM) and Electronic Reporting System (ERS) for Commercial Philippine Flagged Fishing Vessels Amending Fisheries Administrative Order No. 260 Series oF 2018,” https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC201655/.

36 United States Department of Transportation, “SeaVision: A web-based maritime situational awareness tool,” https://info. seavision.volpe.dot.gov/.

37 U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency, “Section 1263 Indo-Pacific Maritime Security Initiative (MSI), https://www. dsca.mil/section-1263-indo-pacific-maritime-security-initiative-msi/.

38 Aaron Lariosa, “Philippine Coast Guard Fleet Celebrates 15th Founding Anniversary Amid Modernization and Expansion Efforts,” Overt Defense, August 30, 2022, https://www.overtdefense.com/2022/08/30/philippine-coast-guard-fleet-celebrates-15th-founding-anniversary-amid-modernization-and-expansion-efforts/.

39 Jay Tristan Tarriela, “What Is the US Coast Guard’s Role in the Indo-Pacific Strategy?,” The Diplomat, June 21, 2019, https:// thediplomat.com/2019/06/what-is-the-us-coast-guards-role-in-the-indo-pacific-strategy/.

40 U.S. Embassy in the Philippines, “U.S., Philippines Unveil New Coast Guard Maritime Training Facility,” February 10, 2019, https://ph.usembassy.gov/u-s-philippines-unveil-new-coast-guard-maritime-training-facility/.

41 Gregory Poling, “From Orbit to Ocean: Fixing Southeast Asia’s Remote Sensing Blind Spots,” Naval War College Review 74, no. 1, Article 8 (2021).

42 Audrey Decker, “Navy’s Task Force 59 Launches Saildrone USV,” Inside Defense, December 13, 2021, https://insidedefense.com/insider/navys-task-force-59-launches-saildrone-usv/.

43 United States Coast Guard Atlantic Area, “Patrol Forces Southwest Asia (PATFORSWA),” November 12, 2022, https://www. atlanticarea.uscg.mil/Our-Organization/Area-Units/PATFORSWA/.

44 The White House, “Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States,” February 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/ uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf.

45 The White House, “Biden-Harris Administration’s National Security Strategy,” October 12, 2022, https://www.whitehouse. gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/10/12/fact-sheet-the-biden-harris-administrations-national-security-strategy/.

46 U.S. Department of Defense, “National Defense Strategy,” October 27, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3201683/department-of-defense-releases-its-2022-strategic-reviews-national-defense-stra/ https%3A%2F%2Fwww.defense.gov%2FNews%2FReleases%2FRelease%2FArticle%2F3201683%2Fdepartment-of-defe nse-releases-its-2022-strategic-reviews-national-defense-stra%2F/.

47 Mikayla Easley, “Coast Guard Cutter Program Treading Water,” National Defense, August 12, 2022, https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2022/8/12/coast-guard-cutter-program-treading-water/.

48 LT. CMDR Warren Wright, “Shiprider Program,” Indo-Pacific Defense Forum, November 22, 2022, https://ipdefenseforum. com/2020/01/shiprider-program/.

49 U.S. Interagency Working Group on IUU Fishing, “National 5-Year Strategy for Combating Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing Strategy 2022-2026,” October 19, 2022, https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/new-us-strategy-forcombating-illegal-unreported-and-unregulated-fishing/.

50 Baird Maritime, “VESSEL REVIEW | Teresa Magbanua – New Class of 97m Multi-Role Vessels for Philippine Coast Guard,” Baird Maritime, May 30, 2022, https://www.bairdmaritime.com/work-boat-world/maritime-security-world/non-naval/ vessel-review-teresa-magbanua-new-class-of-97m-multi-role-vessels-for-philippine-coast-guard/.

51 Jay Tristan Tarriela, “What the Philippine Coast Guard Now Needs,” BusinessWorld Online, March 3, 2019, https://www. bworldonline.com/editors-picks/2019/03/03/217486/what-the-philippine-coast-guard-now-needs/.

52 David Oliver, “Philippine Coast Guard Commissions Second H145 Helicopter,” Asian Military Review, October 28, 2020, https://asianmilitaryreview.com/2020/10/philippine-coast-guard-commissions-second-h145-helicopter/.

53 Republic of the Philippines Department of Transportation, “Proposed Acquisition of Seven Maritime Disaster Response Helicopters,” PCG - Foreign Assisted Projects, November 14, 2022, https://dotr.gov.ph/maritime-sector/pcg/67-maritimesector/3146-pcg-foreign-assisted-projects.html/.

54 U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency, “Security Cooperation Programs, Fiscal Year 2022,” November 12, 2022.

55 Airbus U.S., “H145,” August 3, 2021, https://us.airbus.com/en/helicopters/products-and-services/civil-helicopters/h145/.

56 Jay Tristan Tarriela, “What the Philippine Coast Guard Now Needs,” BusinessWorld Online, March 3, 2019, https://www. bworldonline.com/editors-picks/2019/03/03/217486/what-the-philippine-coast-guard-now-needs/.

30

U.S. Coast Guard, “Fast Response Cutters,” November 19, 2022, https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Our-Organization/ Assistant-Commandant-for-Acquisitions-CG-9/Programs/Surface-Programs/Fast-Response-Cutters/.

58 10 U.S.C. § 301(8).

59 U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, “U.S. Transfers Custody of New Joint Maritime Law Enforcement Training Center,” November 15, 2022, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/News/News-Article-View/Article/1272201/ustransfers-custody-of-new-joint-maritime-law-enforcement-training-center/https%3A%2F%2Fwww.pacom. mil%2FMedia%2FNews%2FNews-Article-View%2FArticle%2F1272201%2Fus-transfers-custody-of-new-jointmaritime-law-enforcement-training-center%2F/.

60 Thayalan Goal and Venkatachalam Anbumozhi, “Effects of Disasters and Climate Change on Fisheries Sectors and Implications for ASEAN Food Security,” Towards a Resilient ASEAN Volume 1: Disasters, Climate Change, and Food Security: Supporting ASEAN Resilience, Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia, December 2019, p. 162, https://www.eria.org/uploads/media/Books/2019-Towards-a-Resilient-ASEAN-Vol1/Towards-aResilient-ASEAN-Vol-1.pdf/.

61 Asian Development Bank, “Six Ways Southeast Asia Strengthened Disaster Risk Management,” May 6, 2021, https://www.adb.org/news/features/six-ways-southeast-asia-strengthened-disaster-risk-management/.

62 The United Nations Economic and Social Commission on Asia and the Pacific, “The Disaster Riskscape Across South-East Asia,” Asia-Pacific Disaster Report, 2020, p. 3, https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/IDD-APDRSubreport-SEA.pdf/.

63 NOAA, “How Do Natural Disasters Contribute to the Marine Debris Problem?,” March 3, 2015, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/disaster-debris.html/.

64 Stacey White, “Asia’s Response to Climate Change and Natural Disasters: Implications for an Evolving Regional Architecture,” CSIS Asian Regionalism Initiative, Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 2010, p. 64, https://www.csis.org/analysis/indigenous-defense-industries-gulf%2C%20https%3A/csis-website-prod. s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/200424_Indigenous_0.pdf/.

65 Meghan Sullivan, “Bolstering Regional Approaches to Disaster Management for the Future in Southeast Asia,” New Perspectives on Asia, Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 9, 2022, https://www.csis.org/ blogs/new-perspectives-asia/bolstering-regional-approaches-disaster-management-future-southeast-asia/.

66 Gregory Coutaz, “Disaster Management in the South China Sea: A Chance for Peace and Cooperation,” pp. 117–34, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62828-8_6/.

67 Association of Southeast Asian Nations, “ASEAN Disaster Resilience Outlook Report: Preparing for a Future Beyond 2025,” October 2021, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ASEAN-Disaster-Resilience-OutlookPreparing-for-the-Future-Beyond-2021-FINAL.pdf, 97-99.

68 We discuss humanitarian assistance and disaster response in the broader context of ASEAN given that the preponderance of disaster response coordination in the region already happens through existing ASEAN structures. The authors assess that it is more valuable to build solidarity among claimant states though these existing structures rather than create new and potentially duplicative coordination efforts among claimant states only.

69 Association of Southeast Asian Nations, “ASEAN to Improve Synergies for One ASEAN One Response,” March 28, 2018, https://asean.org/asean-to-improve-synergies-for-one-asean-one-response/.

70 Deon Canyon, Elizabeth Kunce, and Benjamin Ryan, “Structuring ASEAN Military Involvement in Disaster Management and the ASEAN Militaries Ready Group,” Security Nexus Perspectives, The Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, May 2020, p. 1, https://dkiapcss.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/brochure-2022. pdf/.

71 Deon Canyon, Elizabeth Kunce, and Benjamin Ryan, “Structuring ASEAN Military Involvement in Disaster Management and the ASEAN Militaries Ready Group,” Security Nexus Perspectives, The Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, May 2020, p. 4, https://dkiapcss.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/brochure-2022. pdf/.

72 United States Department of State, “Guidelines for Quad Partnership on Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) in the Indo-Pacific,” https://www.state.gov/guidelines-for-quad-partnership-on-humanitarianassistance-and-disaster-relief-hadr-in-the-indo-pacific/.

73 The 11 SEAFDEC member countries are Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

74 USAID, “Sustainable Fish Asia Local Capacity Development,” https://www.usaid.gov/asia-regional/fact-sheets/ sustainable-fish-asia-local-capacity-development/.

75 USAID, “USAID and NOASS Support for Sustainable Fisheries in the Asia Pacific Region,” https://www.usaid.gov/ asia-regional/fact-sheets/usaid-and-noaa-support-sustainable-fisheries-asia-pacific-region/.

76 Jeremy Prince et. al., “The CFRA: A Joint Assessment of South China Sea Skipjack Tuna Stocks,” 2022, http://www. rimf.org.vn/baibaocn/chitiet/a-joint-assessment-of-south-china-sea-skipjack-tuna-stocks/.

77 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), “NOAA takes strong stand against IUU fishing and harmful fishing practices,” https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/noaa-takes-strong-stand-against-iuu-fishingand-harmful-fishing-practices/.

78 Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center (SEAFDEC), “SEAFDEC, FAO successfully co-host the second training course for advanced stock assessment,” http://www.seafdec.org/seafdec-fao-successfully-co-host-thesecond-training-course-for-advanced-stock-assessment/.

79 NOAA, “Stock Assessment Training Program,” https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/population-assessments/ stock-assessment-training-program/.

57

Poungthong Onoora, “Addressing the legislative gaps in the implementation of port state measures: Southeast Asian perspective,” Fish for the People 16, no. 1, 2018, pp. 5-20.

81 Ibid.

82 Rong-Her Chiu, Chien-Chung Yuan, and Kee-Kuo Chen, “The implementation of port state control in Taiwan,” Journal of Marine Science and Technology 16, no. 3 (2008): 6.

83 United Nations Institute for Training and Research, “International Environmental Law - Self-paced track - 2023 - Q,” Full Catalog, November 21, 2022, https://event.unitar.org/full-catalog/international-environmental-law-selfpaced-track-2023-q1/.

84 48,200 pesos, or about USD 829.

85 The budget is currently USD 72,495 million. See “Programme Budget for the Biennium 2022-2023,” UNITAR/ BT/62/2, United Nations Institute for Training and Research, November 22, 2022, https://unitar.org/sites/default/ files/media/publication/doc/BOT-Adopted-ProgBudget-Biennium22-23_1.pdf/.

80

36

37