Harnessing the Power of Local and Equitable Climate Adaptation: A Proposal for the Accra Metropolitan As sembly (AMA)

Harnessing the Power of Local Government for Effective, Inclusive, and Equitable

Climate Adaptation:

A Proposal for the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA)

Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

Policy Workshop Report

April 2023

Faculty Advisor

Dr. Devanne Brookins

Associate Research Scholar and Lecturer, Princeton School of Public and International Affairs

Authors

Martina Bergues | Rouguiatou Diallo | Ariza Francisco | Kazim Habib

Claire Kaufman | J. Sebastián Leiva | Auri Minaya | Jessie Press-Williams

Ryan Sasse | Dominick Tanoh | Rain Tsong | Evelyn Wong

We dedicate this report to Seydi, our 13th team member. May you grow up in a world that is truly inclusive and equitable for all.

Sunset over the Accra skyline.

Cover photo courtesy of Adobe Stock Stock Photo ID: 341274506

Sunset over the Accra skyline.

Cover photo courtesy of Adobe Stock Stock Photo ID: 341274506

1 Preface 1 2 Acknowledgements 2 3 Acronyms 2 4 Executive Summary 3 5 Context 5 6 Purpose 11 7 Methodology 12 8 Key Actors 16 9 Analysis of Strengths and Challenges 21 10 Recommendations 30 11 Conclusion 45 12 List of Interviews 46 13 Workshop Participants 47 14 Appendix 53 15 Endnotes 56

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 | PREFACE

This report is the final product of a Policy Workshop sponsored by the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs (SPIA), fulfilling partial requirements for the Master in Public Affairs (MPA) degree program. It is the result of the work of twelve graduate students advised by Dr. Devanne Brookins, Lecturer in Public and International Affairs, Princeton University.

The report’s information and recommendations stem from months of research and interviews with current and former government officials in the city of Accra, members of civil society, academics, researchers, and officials of international institutions like the United Nations. A list of stakeholders interviewed is included at the end of the report. The group conducted in-person and virtual interviews in both Accra, Ghana and Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

Throughout the report, we make reference to some of those we interviewed by name, indirectly by title, or merely as a workshop interview. This was done at the request of those we interviewed to allow them to speak freely and for us to be able to use the information they provided to us in this report. The report, however, does not necessarily reflect the views of any individual interviewee, Princeton University, the Accra Metropolitan Assembly, or any person or their affiliated organizations who supported the workshop.

1 1 | PREFACE

2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are deeply grateful to the many people who supported us during our Policy Workshop. We thank the government officials, researchers, and others who generously lent their time and expertise to us. Their contributions to our understanding of the climate adaptation space in Accra was invaluable.

We would like to thank Dr. Devanne Brookins for her mentorship throughout the workshop. This final report would not have been possible without her expertise and thoughtful recommendations. A special thanks is also given to Eden Tekpor Gbeckor-Kove and Lydia Sarfoa from the AMA, whose on-the-ground support and hospitality while we were in Accra allowed us to make the most of our time in the city. Finally, we are thankful to Dean Amaney Jamal, Senior Associate Dean Paul Lipton, Associate Dean Karen McGuinness, Associate Director Tam Le Rovitto, Finance and Operations Manager Shannon Presha, and the rest of the SPIA team who helped make this workshop possible.

3

ACRONYMS

• AMA: Accra Metropolitan Assembly

• CAP: [Accra] Climate Action Plan

• GAR: Greater Accra Region

• GARCC: Greater Accra Regional Coordinating Council

• GARID: Greater Accra Resilient and Integrated Development Project

• GHAFUP: Ghana Federation of the Urban Poor

• GYEM: Ghana Youth Environmental Movement

• HRBA: Human Rights-Based Approach

• IOs: International Organizations

• MER: monitoring, evaluation and reporting

• MTDP: Medium-Term Development Plan

• MMDAs: Metropolitan, Municipal, and District Assemblies

• NAP: National Adaptation Plan

• NCCAS: National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy

• NUP: National Urban Plan

• NCCP: National Climate Change Policy

• NADMO: National Disaster Management Organization

• NDC: Nationally Determined Contribution

• NGOs: Nongovernmental Organizations

• PD: People’s Dialogue

• SDGs: Sustainable Development Goals

• UN: United Nations

• UNDP: United Nations Development Programme

• UNFPA: United Nations Population Fund

• UN-Habitat: United Nations Human Settlements Programme

• 100RC: 100 Resilient Cities

2 2 | ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

|

|

4 | EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa the urgent realities of climate change – including flooding, drought, sea level rise, and extreme weather events – are becoming increasingly evident. Cities face a disproportionate level of current and future climaterelated risks, and thus city governments play a key role in responding and adapting to climate change. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Accra, the capital city of Ghana. This rapidly urbanizing city is challenged by a precarious position along the coast and a river basin that regularly floods, disproportionately impacting communities living in informal settlements. The growing interconnection of urban poverty and vulnerability highlights the need for a cross-sectoral and strategic response from the local government, in addition to national and international actors.

In this report, we analyze the strengths, challenges, and opportunities of Accra’s local government unit, the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), to respond to climate change in a way that is inclusive to all residents. The AMA is expected to be both the local implementer of central government policies and the primary administrative authority for constituents living across formal and informal settlements, within the constraints of limited financial and human resources. Recent decentralization has, however, dramatically reduced the AMA’s jurisdiction and, subsequently their capacity to raise revenue and implement projects.

Within this challenging context, the purpose of this project is to support the AMA in enhancing its capacity to implement its climate adaptation agenda with meaningful engagement of marginalized communities, focusing on informal settlements. Together with the AMA, we identified two strategic objectives to guide our work:

• Objective 1: Develop a strategy to position the AMA as a global champion of effective local

government ownership, coordination, and implementation of their urban climate agenda.

• Objective 2: Build a framework for effective and sustainable engagement between the AMA and community stakeholders.

This report is the culmination of research and interviews conducted between September and December 2022, including a week of fieldwork in Accra. During this period, we completed interviews with 16 key actors within the AMA, national government, international organizations, civil society stakeholders, and academia. We complemented interviews with literature reviews, case studies, and theoretical frameworks.

Our research highlights three strengths of the AMA that provide the foundation for effective implementation of climate adaptation plans:

1. The AMA has built a climate agenda aligned with global climate priorities, including Ghana’s national commitments under the Paris Agreement and the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This positions the city as a focal point for international investments in climate resilience.

2. Climate-related policies have been incorporated into AMA’s local plans. Our analysis of the AMA’s Medium-Term Development Plan (MTDP) found significant inclusion of Climate Action Plan activities, particularly for solid waste management and wastewater.

3. The AMA engages with its residents on a regular basis. Community engagement is seen as essential, aiming to create a sense of shared responsibility. The majority of existing engagements are sensitization or education efforts, although the AMA does occasionally involve community actors in designing policies.

3 4 | EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Despite these strengths, we identified five challenges that impede climate adaptation. These challenges are not exhaustive but reflect concerns internal to the AMA.

1. The climate agenda is fragmented across departments and lacks effective coordination, despite an overarching planning focus on climate change. Climate actions are not streamlined between departments which are inefficient and makes the AMA less attractive for external funding.

2. The AMA faces budget and staff constraints as they seek to accomplish their ambitious climate plans. Internal revenue generation has been significantly reduced by decentralization. The community’s eroded confidence in local authorities’ capacity to deliver services has made the collection of funds more tenuous.

3. There is a low implementation rate of climate action priorities in the MTDP. Most of the activities identified in the Climate Action Plan (CAP) have not been mapped into the MTDP 2022-2025 for implementation, with a few departments, such as waste management, taking up the bulk of the activities.

4. Activities are not well-linked to strategic outcomes and impacts. In both Accra’s Climate Action Plan (CAP) and the MTDP, activities are usually listed at a high level and do not contain specific indicators or milestones, challenging implementation and monitoring.

5. Current community engagement is focused on informing and consulting, rather than partnering and empowering. It tends to be primarily one directional, and marginalized populations are rarely included in the design stage.

This report presents four recommendations that seek to address the outlined challenges so that the AMA can implement their climate adaptation agenda in a way that is sustainable, effective, and equitable for vulnerable populations.

1. Establish a designated unit of Climate Resilience and Sustainability, that will steer the climate change agenda at the AMA level. We present different options to create this unit, and illustrate the tradeoffs of long-term actions, short-term wins, and sustainability considerations.

2. Leverage external stakeholders to attract funding to advance the city’s climate action. The Mayor and the proposed unit of Climate Resilience and Sustainability could work together to identify new revenue streams and position Accra to attract international funding.

3. Ensure that climate adaptation plans are actionable, equitable and inclusive. The AMA could strengthen strategic planning to ensure annual action plans provide detail for step-bystep implementation, incorporate a monitoring, evaluation and reporting (MER) framework to evaluate outcomes regularly and budget time and resources not only for activities and also for data collection and evaluation.

4. Transform the AMA’s community engagement approach into community empowerment. This means implementing a community engagement framework that formalizes the AMA’s intention to engage informal settlements, convene community stakeholders, and use participatory processes to incorporate community feedback into proposed interventions.

Through our recommendations, we aspire to steer the AMA towards localizing its climate agenda in a way that will propel and solidify Accra’s regional and global leadership on climate action. Raising the Mayor’s profile internationally could help Accra attract more attention and resources. The design, coordination, and implementation of climate adaptation projects rooted in co-production with marginalized communities will avoid maladaptation and improve mutual trust and collaboration between the AMA and its most vulnerable community members. With streamlined and mainstreamed climate agendas, the AMA can use its limited resources more efficiently.

4 3 | ACRONYMS

5 | CONTEXT

This section provides some of the necessary context for our analysis of urban climate adaptation in Ghana and the city of Accra. It briefly covers the main climate change challenges, including flooding, solid waste management, and climaterelated vulnerabilities. The section also introduces our client, the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), who is the main local government institution tasked with responding to climate change issues in Accra.

This section addresses the following five areas:

i. Climate Change in Ghana

ii. Climate Change in Accra

iii. Climate and Informality in Accra

iv. Climate and Local Government

v. Climate and the Accra Metropolitan Assembly

CLIMATE CHANGE IN GHANA

Over the last 50 years, Ghana has had three major droughts and 19 flooding events. The average temperature of the country has already increased more than 1 degree Celsius since 1960.1 Flooding has become a perennial problem, and the Ghanaian government recorded over 300,000 people directly affected by flooding in 2020. 2 Landmark flooding in 2015 led to the deaths of 200 people when a flooded gas station in Accra exploded.3 Unfortunately, climate models predict increased drought, rainfall, and flood events for Ghana in the coming years.4

Since 1995, the government of Ghana has implemented over 40 climate adaptation-related policies, strategies, and plans.5 In 2012, the government adopted the first major policy on climate change, the National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NCCAS)6, and the first major policy on urbanization, the National Urban Plan (NUP).7 In 2013, the National Climate Change Policy (NCCP)8 was adopted to provide strategic direction to synthesize national aspirations for adaptation and mitigation.

In 2015, as part of the global Paris Agreement, Ghana committed to a greenhouse gas reduction of 45% by 2030 on the condition that external support is received, with the goal to increase resilience and decrease vulnerability. This goal and strategy are outlined in its National Determined Contribution (NDC, 2015) and the National Climate Change Master Plan Action Programmes for Implementation (2015– 2020).9

Ghana’s National Adaptation Plan (NAP), launched in 2020, brings together various adaptation planning efforts from different sectors, subnational structures, and scales of decision-making to medium- and longterm adaptation needs. Ghana received funding from the Green Climate Fund to implement the NAP within a 36 months period.10 11 The NAP process has two main objectives: to reduce vulnerability to the adverse impacts of climate change by building adaptive capacity and resilience; and to facilitate the integration of climate change adaptation into fiscal, regulatory development policies, programs and activities. It was built from the 2018 NAP Framework, which proposed a more sectoral-based approach to climate change adaptation planning in Ghana, with the EPA coordinating the development of an overarching NAP, and adaptation priorities identified for key sectors such as agriculture, forestry, water, energy, gender, and health.12

Today, Ghana’s MTDP identifies building resilience to threats as one of its six overarching goals and includes responding to climate change as a priority focus for the country.

“Climate forecasts and climate change scenarios for the country predict a more severe and frequent pattern of such drought and flood events. At present, there is broad international consensus that even if the world makes a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, the lag in the climate system means that the world is faced with decades of climate change due to the greenhouse emissions already put into the atmosphere from industrialization activities.”

5 5 | CONTEXT

- NCCAS 201

CLIMATE CHANGE IN ACCRA

Accra’s central climate adaptation issues revolve around flooding and solid waste management. More than half of the flooding incidents in Ghana since 2001 have affected the Greater Accra Region and will only become more common with climate change and increased rainfall.13 Flooding has significant economic and health impacts, especially when it forces the city to shut down as roads become impassable, and contaminated waterways put people at risk of diseases, such as cholera, typhoid, and dysentery. From 2001-2015, floods in Accra caused over 250 deaths and displaced over 178,750 people.14

The issue of flooding in Accra is partly due to and exacerbated by limited drainage and solid waste management infrastructure. The AMA has struggled to keep up with Accra’s solid waste generation, which is currently at 1,645 tonnes per day, amounting to an estimated generation rate of 0.72 kg per person per day.15 All of Accra’s waste disposal sites are currently closed; thus, collected waste is transported from Accra to Kpone landfill in Tema, approximately 37 kilometers away. The landfill’s capacity is 700 tonnes per day, but it receives about 1500 tonnes per day, of which more than two-thirds come from Accra. Uncontrolled dumping and open burning are also common in Accra. Uncontrolled dumping happens in abandoned stone quarry sites, gouged natural depressions in the ground, old mining areas, or man-made holes, while open burning occurs at some of the open dumps, particularly during the dry season.

Overall, waste management services in Accra are inadequate and face challenges such as insufficient financing, poor cost recovery, and institutional weaknesses.16 Gaps in service coverage are filled in by informal waste collectors. Waste collection has largely been asymmetrical, with poorer communities suffering the burden of poor solid waste management services. Without effective solid waste management, drainage gets clogged, and the hazards of flooding become more extreme.

CLIMATE AND INFORMALITY IN ACCRA

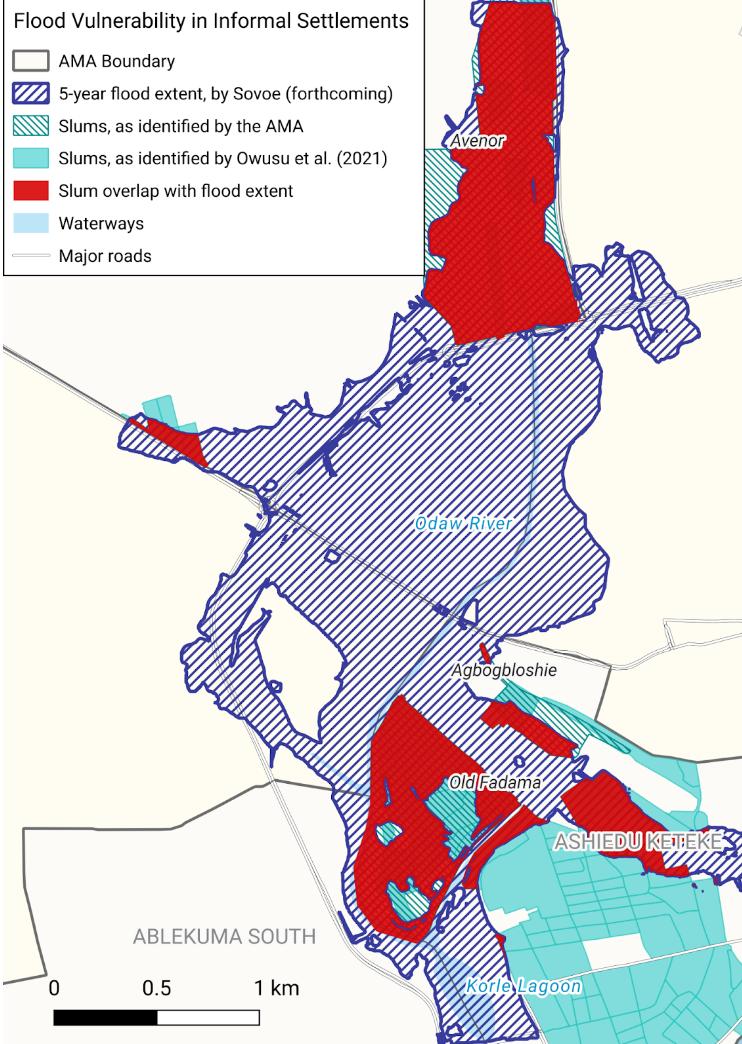

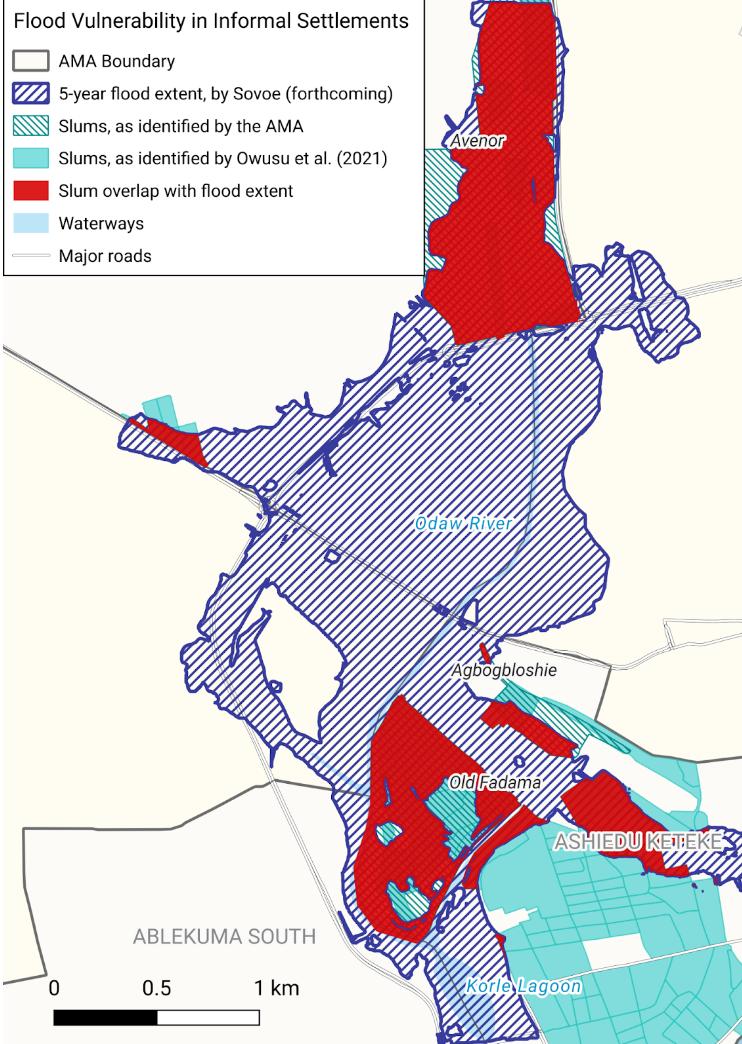

By some estimates, over 90% of communities at risk of flooding in Accra live in informal settlements – over 370,000 individuals.18 The Odaw River Basin has the highest flood risk in the area and contains 80% of Accra’s informal settlements, including Agbobloshie and Old Fadama (see Map 1).19 Despite this, informal settlers experience varying degrees of marginalization that exclude them from climate adaptation initiatives. While sometimes included in collaborative engagement, the forced removal of informal settlers and sellers from public space has led to continuous struggles over land. 20 Specifically, a series of evictions and demolitions in 1993 and

6 5 | CONTEXT

MAP 1: Flood Vulnerability in Informal Settlements near the Odaw River17

2002 attempted to reduce the number of informal settlements. This has made it difficult to consistently and genuinely partner with informal settlements.

Informal settlements are seen with different levels of legitimacy by local authorities and the general public. This informality makes the government’s role as a provider of basic services unclear. For instance, informal settlements are often overlooked in the provision of solid waste collection services. This challenge is exacerbated by the lack of accurate population estimates. After working with Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs) such

People’s Dialogue, informal settlements carried out enumeration efforts to self-report the population. These enumerations returned population estimates that exceed those provided by the AMA (see Table 1 vs. Table 2). This means that the issues of urban flooding in informal settlements may be underestimated and not properly addressed.

Ultimately, the confluence of informal settlements and flood risk underlies the growing interconnection of urban poverty and vulnerability, and requires a cross-sectoral, intentional, inclusive, and strategic response.

7 5 | CONTEXT

SLUM POPULATION, IN THOUSANDS FOOTPRINT (STRUCTURES) Avenor 122 972 Chorkor 18 697 Chemuena 42 1420 Old Fadama 69 2173 Agbogbloshie 110 311 King Nshornaa N.A. N.A.

TABLE 1: AMA’s estimated population of slums within its boundaries21

SLUM POPULATION, IN THOUSANDS FOOTPRINT (STRUCTURES) Avenor N.A. 1620 Chorkor 25 9010 Chemuena N.A. N.A. Old Fadama 80 (2009)23 N.A. Agbogbloshie N.A. N.A. King Nshornaa N.A. N.A.

TABLE 2: Slum Dwellers International’s estimates of population and number of structures in 201622

CLIMATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT

Local governments, in general, bear much of the burden of addressing climate-related damages and adapting to current and future challenges. For example, housing and infrastructure damaged by floods, storms, and heat damage, are under the purview of cities. In Ghana, the Metropolitan, Municipal, and District Assemblies (MMDAs) are the local government agencies with this responsibility.

A comprehensive decentralization program marks the history of democratic Ghana. The Constitution states that the country “shall have a system of Local Government and Administration which shall, as far as practicably, be decentralized.”24 The principle of decentralization was further enshrined in the Local Government Acts of 1993 (Act 462) and 2016 (Act 936), which delineated the creation and regulation of the MMDAs, which serve as administrative and decision-making units with deliberative, legislative, and executive functions.

Under the Ghanaian Constitution, MMDAs are composed of elected and appointed officials. Twothirds of the members are popularly elected, while the Ghanaian President appoints the remaining onethird of the assembly members. The Mayor, known as Chief Executive, is appointed by the President with the prior approval of not less than a two-thirds majority of the members of the Assembly present and voting at the meeting.

Decentralization has greatly increased the number of MMDAs, from 110 in 2000 to 261 in 2022. The AMA is now one of 261 current MMDAs in the country, and one of 29 in the Greater Accra Region (GAR), and its jurisdiction has been reduced from 10 submetros spanning an area of ~140 km2 to an area of 23 km2 encompassing 3 sub-metros (see Map 2). 25 Although the division of the country aims to bring services closer to citizens, it also diminishes the capacity to raise revenue and implement adaptation projects. 26

Furthermore, decentralization adds an additional layer of challenges, especially when it comes to addressing complex issues such as infrastructure and climate change that transcend administrative boundaries.

MAP 2: Impacts of Decentralization on AMA 2016-Present27

Still, as part of its primary functions, the AMA is responsible for the area’s overall development, including social development, basic infrastructure, service delivery, security, and public safety. According to the Local Governance Act of 2016, the AMA is empowered to define how the district develops, mobilize resources to spur this development, and improve the human settlements found throughout the district. 28

8 5 | CONTEXT

There are 16 Statutory Departments working in different areas in the AMA, including education, health, transport, urban roads, waste management, social welfare, food & agriculture, among others. Although non-exhaustive, Figure 1 summarizes key departments in the AMA with whom we engaged for this research.

SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT

SOCIAL WELFARE & COMMUNITY

• Responsible for the provision of the infrastructure, services and programs for waste management.

• Solid waste management is a key element of the climate agenda in Accra, responsible for 44% of the emissions.

• Responsible for the engaging with communities and vulnerable populations.

• On the climate agenda, the department helps with sensitization and engagement mechanisms.

DISASTER MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTION

METRO PLANNING AND COORDINATING

• Responsible for preventing and mitigating disasters, including climate threats.

PHYSICAL PLANNING

• Responsible for the providing leadership in the planning, implementation and evaluation of development projects and programs in the Assembly.

• Responsible for many activities, including assisting in preparations of physical plans as a guide for the formulation of development policies, including climate

9 5 | CONTEXT

FIGURE 1: AMA departments engaged in our research

CLIMATE AND THE AMA

The AMA has demonstrated that responding to climate change is a priority. The MTDP, the most important plan for the city, identifies poor drainage systems and poor sanitation as the top two priority development issues for Accra, with recurring flood incidents as a fourth major issue.

Accra-specific plans and programs as well have cemented city leadership with climate change. In 2014, the City of Accra joined the 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) initiative led by the Rockefeller Foundation and published a Resilience Strategy Book which outlined a vision of embracing informality as an engine of growth, designing infrastructure to improve the natural and built environments, and optimizing resources and systems for greater efficiency, accountability, and transparency. Although Rockefeller officially ended 100RC in April 2019, many of the recommendations are integrated into the MTDP.

In 2019, the World Bank, in collaboration with the AMA and the government of Ghana, launched the Greater Accra Resilient and Integrated Development (GARID) project. GARID is intended to improve flood mitigation infrastructure around the Odaw River basin through improved drainage and flood mitigation measures, solid waste management capacity improvements, participatory upgrading of targeted flood-prone low-income communities, and disaster preparedness. 29

In 2018, Accra partnered with C40 cities to develop its Climate Action Plan (CAP).30 Built from a citywide greenhouse gas emissions inventory, it aims to reduce emissions by 27% by 2030 and 73% by

2050. In the First Five-Year Plan 2020-2025, priority actions fall into the categories of solid waste and wastewater; energy, buildings and industry; transportation; land use and physical planning; and mainstreaming climate in development – the sectors that produce the most emissions in Accra.

Through its C40 membership, Accra is also a member of the Inclusive Climate Action Forum, a platform for peer-to-peer exchange, support, and learning that unites C40 cities in a common goal: the implementation of inclusive, local green new deals. This November 2022, the AMA hosted the four-day Inclusive Climate Action Academy.31 Further, Accra has signed the C40 Equity Pledge, committing the city to:

1. Community-led development;

2. Inclusive climate action and infrastructure projects that center low-income and vulnerable communities; and

3. Delivering bold climate action that benefits all residents equitably.32

The AMA does not have an institutionalized and permanent department responsible for climate change. Instead, the climate agenda is distributed across different departments, each contributing to various aspects of the climate agenda. According to one of the non-governmental interviewees, there exists an office for the AMA Chief Resilience and Sustainability Officer, and an office that accommodates the C40 Advisor and a Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety Advisors. However, this unit was not mentioned by AMA staff interviewed and appears to be mostly an externally funded unit for special projects. This indicates a lack of harmonization and institutional integration.

10 5 | CONTEXT

Given the current situation and aforementioned context, the purpose of this project is to support the AMA in enhancing its capacity to implement its climate adaptation agenda and support meaningful engagement of marginalized communities, focusing on informal settlements. For this reason, we have outlined the following two strategic objectives:

1. Develop a strategy to position the AMA as a global champion of effective local government ownership, coordination & implementation of their urban climate agenda.

2. Build a framework for effective and sustainable engagement between the AMA and community stakeholders.

Through our recommendations, we aspire to steer the AMA towards localizing its climate agenda in

POSITIONALITY STATEMENT

We have sought to center our research on what we heard from the government and citizens of Accra, prioritizing actionable recommendations that are sensitive to local context while taking an inclusive approach to incorporating global perspectives and knowledge. Nevertheless, we wish to acknowledge our positions and limitations as graduate students receiving policy training in an elite Western institution, which privileges certain perspectives on development and assumes neutrality and

a way that will propel and solidify Accra’s regional and global leadership on climate action. Our hope is to deliver a clear and streamlined process for the design, coordination, and implementation of climate adaptation projects that is rooted in coproduction with marginalized communities in order to avoid maladaptation and improve mutual trust and collaboration between the AMA and its most vulnerable community members.

This report details the outcomes of this project. The following sections Section 7 Methodology and Section 8 Key Actors provide context on how we approached the research and which actors we focused on, respectively. The following sections Section 9 Analysis of Strengths and Challenges and Section 10 Recommendations present our findings.

distance from the subject observed. While many of us are from the Global South, most have no prior experience in Ghana. While we have made efforts to include diverse stakeholder views, we acknowledge that not all voices are represented in this report. We view this report as a starting point for discussion and action rather than an authoritative assessment. We have included our contact information at the end of the report, and welcome feedback on aspects that we have missed or misunderstood.

11 6 | PURPOSE

6 | PURPOSE

7 | METHODOLOGY

This report’s information and recommendations are the culmination of research and interviews conducted between September and December 2022. We interviewed current and former government officials in Ghana, local and international researchers working in urban climate adaptation and informal settlements in the Global South, international organizations staff, and civil society members.

Our project purpose and strategic objectives were co-developed with our client, the AMA. We conducted our research and analysis using a mixed-methods approach, as described below.

i. Literature reviews

Prior to stakeholder interviews, we conducted literature reviews around three themes: urban climate adaptation, informal settlements, and local governance. We developed hypotheses and research questions based on our respective areas of interest, which were incorporated into interview protocols. After we refined the scope of work following interviews, we conducted targeted peerreviewed literature reviews to identify best practices and case studies pertaining to data analysis and policy recommendations.

ii. Interviews

We conducted interviews in person in Accra during a week of fieldwork in October 2022, and virtually in Princeton from September to December 2022. Semi-structured interview protocols were created for each organization type (e.g. government, international organization, academia) to aid consistency for coding themes while providing some freedom for interviewees to surface individual concerns. We recorded and transcribed each interview, and obtained permission for any direct

quotes. A list of those we interviewed can be found at the end of this report.

iii. Data analysis

We collected and analyzed climate adaptation frameworks, national and local development plans, and other relevant planning, budgeting, and reporting documents from the past five years, identifying key themes in climate planning and implementation. We assessed local plans for their alignment with strategic frameworks and the strength of operational detail.

iv. Case studies

We collected case studies across peer-reviewed journals and gray literature (e.g. government reports and non-profit research) on cities in the Global South that addressed the same challenges encountered in the Accra context. In selecting case studies, we focused on extracting transferable lessons as well as illustrating the successes and limitations of these strategies deployed.

v. Analytical frameworks

We used several analytical frameworks to situate AMA’s current climate adaptation and community engagement approaches within global best practices.

Framework 1: Mainstreaming Climate Adaptation

The Wamsler and Pauleit Framework proposes five types of strategies that increase goal clarity and facilitate implementation (see Table 3).33 These strategies could allow the AMA to integrate (“mainstream”) climate adaptation objectives into existing policies in a congruent manner.

12 7 | METHODOLOGY

TYPE OF MAINSTREAMING DEFINITION EXAMPLE

Managerial

Projects and Programs

Political or high-level support

Regulatory

Collaboration and coordination

The modification of managerial and working structures, including personnel and financial assets to better address and institutionalize aspects related to adaptation.

Integrating adaptation into on-the-ground operations.

Topp-down support to redirect focus by allocating funding, directing responsibilities, or promoting new projects.

Modification of formal and informal planning procedures that lead to the integration of adaptation policies.

The promotion of collaboration with other departments (within the organization) or stakeholders (across organizations) to generate shared knowledge and competence for issues of adaptation.

Framework 2: Locally Led Adaptation

Local actors are aware of the nuanced context in which they operate. Devolving power with local actors increases their awareness of and investment in adaptation, which can lead to longer-term and more effective adaptation outcomes. Figure 2 shows our AMA Community Engagement Ladder, adapted from Arnstein’s Ladder.34 It illustrates the different levels of community engagement, from least to most locally led.

Community engagement is often centered just on the first rung on the ladder, inform, which implies a one-way flow of information. The second rung, consultation, is an important step towards inviting citizens’ opinions, yet when not combined with other modes of participation it offers no assurance that citizen concerns and ideas will be taken into account. The third rung, involve, includes critical citizen participation, but is at risk of tokenism – involving citizens only to demonstrate that they were involved. The fourth rung, collaborate, involves a partnership with the public working alongside the government, where

Merging departments

Having adaptation goals embedded into daily tasks

Guidance or funding by higher administrative levels

Creating a legal mandate

power is redistributed through negotiation between community members and powerholders. In the fifth rung, empower, community actors have agency over adaptation, rather than merely participating in processes around adaptation. This is participation as delegated power, where governments and those with existing power give up a degree of control, management, and decision-making authority. The sixth and highest rung, local leadership, places the community in charge of their issue; in this case, the climate adaptation agenda. This includes devolving decision making to the lowest appropriate level, addressing structural inequalities, providing patient and predictable funding, investing in local capabilities, building in climate risk and uncertainty, flexible programming and learning, ensuring transparency and accountability, and collaborative action and investment.

In line with our purpose of co-production with marginalized communities to avoid maladaptive outcomes, we have aimed to recommend options that build towards a local leadership of adaptation measures wherever possible.

13 7 | METHODOLOGY

Information exchange between departments

TABLE 3: Types of Mainstreaming

Adopted from Wamsler and Pauleit (2016). Authors note “the framework can be applied to single municipal departments or other implementing bodies at all levels.

ENGAGEMENT LADDER

Adapted from Arnstein 1969

Devolve decision making to the lowest appropiate level and support communities implementing their agenda.

Framework 3: Human Rights-Based Approach

According to the UN Sustainable Development Group, a human rights-based approach (HRBA) is “a conceptual framework that is normatively based on international human rights standards and operationally directed to promoting and protecting human rights.”35

Support aspirations of the public and delegate responsibility through action teams and leadership development.

HRBAs seek to analyze obligations, inequalities, and vulnerabilities while rectifying discriminatory practices and unjust distributions of power that impede social progress and threaten human rights. This approach helps to promote the longterm sustainability of policies and programs by empowering people themselves (i.e. the “rightsholders”) to directly participate in policy formulation and thus hold accountable those who have a duty to act (i.e. the “duty-bearers”).

In the context of climate change, human rightsbased approaches can be used to:

Partner with the public in each aspect of planning through citizen advisory

• Inform policies and programs around climate mitigation and adaptation at both the national and local levels;

• Guide initial assessments of climate-related vulnerabilities, and then strengthen monitoring and evaluation processes; and

Ensure public wants are understood and taken into consideration through open space meetings, workshops and polling.

• Ensure equitable access to essential information among the affected population and meaningful participation of marginalized groups, without discrimination, in the design and implementation of climate change policy.36

Obtain feedback to make an informed decision through public comments, hearings, focus groups and surveys.

Communicate the issues and planned solutions through newsletters, flyers, websites and meetings.

6 | LOCAL LEADERSHIP

5 | EMPOWER

4 | COLLABORATE

committees, consensus building.

3 | INVOLVE

2 | CONSULT

1 | INFORM

14 7 | METHODOLOGY

FIGURE 2: AMA Community Engagement Ladder

Why is a human rights-based approach important to policymakers like the AMA?

• Climate change threatens the full and effective enjoyment of a wide variety of human rights.

• Inadequate mitigation and adaptation strategies can lead to significant human rights violations, especially in situations where adequate participation of local communities is not assured or where due process and access to justice is not respected for any necessary displacement/ resettlement.

• By focusing on the rights of those who are most vulnerable due to poverty and discrimination, a human rights-based approach can be a useful tool to complement and strengthen a range of other development efforts seeking to address the climate crisis.37

By using a HBRA in this report’s policy recommendations, we hope to ensure that the needs and experiences of the most marginalized in Accra – women, children, the elderly, persons with disabilities, and those living in informal settlements – are centered in the design and implementation of the city’s climate policies. International frameworks like HRBAs can be used to drive sustainable and resilient, people-centered development in Accra, creating an opportunity for the city to demonstrate its global leadership in effectively targeting the discriminatory practices and unjust power relations that are so often at the heart of inequitable rights outcomes.

15 7 | METHODOLOGY

Photo courtesy of Adobe Stock Stock Photo ID: 75565421

8 | KEY ACTORS

Implementation of Accra’s urban climate adaptation agenda is a multiscalar issue that demands coordination between diverse stakeholders. In this section, we detail a non-exhaustive list of stakeholders that are currently involved in Accra’s climate adaptation planning. The key actors, summarized in Figure 3 and expanded upon below, all bring varying perspectives of knowledge, power, and vulnerability that can inform the holistic approach necessary for sustainable intervention. It is important to note that although we have tried to identify stakeholders of particular importance, this is not a comprehensive list.

This section will cover the following stakeholder categories:

1. Local Government

2. National government

3. Intergovernmental organizations

4. Informal settlers

5. Domestic NGOs

6. Customary authorities

7. Academia

8. Private sector

16 8 | KEY ACTORS

Nongovernmental Organizations Intergovernmental Organizations Informal Sector Private Sector Government Academia National Government of Ghana Greater Accra Regional Coordinating Council Accra Metropolitan Assembly C40 Cities Resilient Cities Network The World Bank Informal Settlers Informal Workers The United Nations Slum Dwellers International People’s Dialogue COLANDEF INTERNATIONAL NATIONAL LOCAL

Stakeholders for Urban Climate Adaptation in Accra (not exhaustive)

FIGURE 3: Stakeholder Mapping

LOCAL GOVERNMENT

While this report was formally produced for the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), our findings acknowledge that the AMA is only one part of a larger local government system unique to Ghana. This system’s structure includes multiple players: the Regional Coordinating Council, Metropolitan Assembly, Municipal Assembly, District Assembly, Sub-Metropolitan District Council, Town/area Council, and Unit Committee (Figure 4).

In the GAR, the Greater Accra Regional Coordinating Council (GARCC) serves as the governing coordinating group that oversees the 3 MMDAs that compose Accra. It is an important liaison between the AMA and other Metropolitan Assemblies in the GAR, as well as NGOs and the national government.38 Although it lacks unilateral policy-making power, it is instrumental

in ensuring that the actions of the disparate stakeholders all support the development of the GAR. Because climate-related disasters naturally cross administrative borders, GARCC will play an important role in ensuring that adaptation efforts are well coordinated between the AMA and other pertinent partners.

The AMA is the lead coordinator of the city’s climate adaptation strategy, and holds the responsibility to respond as outlined in the Local Government Act of 2016. We expand on the strengths and challenges of the AMA in climate adaptation in Section 8, and Section 9 provides recommendations for the AMA as it moves forward. Within the AMA, the Mayor and 19 elected Assembly Members represent the voices of the electorate in local government. This is further separated into 3 sub-metropolitan district councils: Ablekuma South, Ashiedu Keteke, and Okaikoi South, and accompanied by 6 government

17 8 | KEY ACTORS

FIGURE 4: Structure of Local Government Service39

NATIONAL GOVERNMENT

Although Ghana maintains a uniquely decentralized political structure, the national government is a critical piece of the climate adaptation puzzle. National-level ministries like the Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology, and Innovation house important sub-agencies like the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency and the National Climate Change Committee, which each play an active role in developing climate adaptation priorities that the AMA must consider. Furthermore, the government of Ghana serves as the primary partner of development-focused institutions like the World Bank.

INTERGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS

By virtue of its economic and political influence, Accra has successfully joined multiple international institutions that influence its climate adaptation plans. The AMA has been able to benefit from its international partnerships and receives significant technical assistance and funding for climate adaptation from collaborators. This includes the World Bank through the GARID project, which is intended to improve flood mitigation infrastructure around the Odaw River basin. Support for Ghana’s long-term economic solvency will ultimately be an important piece of long-term climate adaptation funding sustainability.

Additionally, the UN Development Programme (UNDP), the UN Environmental Programme (UNEP), and the UN Human Settlement Programme (UN Habitat) provide technical and financial support to the central government and the AMA. UNDP’s most relevant initiatives are the Ghana Waste Recovery Platform to help collect data and coordinate waste collection initiatives in the city and the Accelerator Lab, where they are working to address waste management using behavioral insights. UNEP is involved in climate adaptation coordination and funding. UN Habitat is also supporting the creation of a new climate adaptation plan in cities like Accra in accordance

with various development frameworks including the Ghanaian government’s National Coordinated programme of Economic and Social Development Policies (2017-2024), the United Nations Sustainable Development Partnership (2018-2022), the UN New Urban Agenda, and African Union’s Africa Agenda 2063, along with the UN’s sustainable development goals.40

Finally, C40 Cities is Accra’s main partner in their Climate Action Plan and maintains a permanent office within the AMA. They have also been active in outreach to informal waste collectors. Previously, 100RC played a significant role in advising Accra on how to build resistance to climate, economic, and social crises. Its recommendations ultimately helped to shape key planning documents including Ghana’s MTDP. Accra remains a part of the Resilient Cities Network with access to its technical advising.

It’s also important to note that foreign country aid programs, like Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), play a role in financing development programs in Accra as well aimed at climate adaptation.

CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES

Customary and familial authorities play a significant role in Ghana’s land tenure system through their custodianship of “stool lands’’ and “family lands” respectively. Stool lands are the historical territories of Ghana’s many ethnic groups, while family lands are governed by individual families.41 These authorities have protected rights and ownership of around 80% of the land in Ghana. Although the MMDAs maintain relatively greater power in urban centers like Accra, leveraging these stakeholders could help remove potential grassroots roadblocks and help further formalize and institutionalize planned AMA initiatives. For example, customary authorities and land-holding families can often be more effective community interlocutors than the AMA.42 These stakeholders also have the power to disrupt or delay urban development interventions, such as those requiring infrastructure construction.

18 8 | KEY ACTORS

Thus, engagement is key for the implementation of climate adaptation initiatives.

DOMESTIC NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS (NGOS)

Domestic NGOs facilitate the AMA’s interaction with community members on several subject areas. There are a variety of local NGOs embedded in marginalized communities with wide-ranging expertise, from youth engagement to land tenure to informal work and settlement.

Specifically, People’s Dialogue (PD) – the Ghana affiliate of Slum Dwellers International – has been a key interlocutor over the years between informal settlers’ savings groups and government officials. PD provides technical assistance to informal settlers in their activities and in articulating and disseminating their policy priorities. The AMA routinely approaches PD to assist in the implementation of projects that necessitate community involvement. COLANDEF is another well-embedded local organization focused on issues of equity and land tenure. Additionally, youth organizations, like Ghana Environmental Youth Movement, are important stakeholders in raising awareness about climate change among young people and bringing climate policy priorities to the public debate.

INFORMAL SETTLEMENTS

Informal settlers are people who have settled on land that they either have no legal claim to, or in housing that is not compliant with the government regulations. Informal settlements usually lack access to basic services and are cut off from city infrastructure.43 Because climate and housing vulnerability often intersect (e.g. most flood-related vulnerability in Accra is concentrated in informal settlements), informal settlers are key actors in the climate adaptation process. As informal settlers have organized, they have found some occasionally influenced the AMA to recognize this and adopt more inclusive policy interventions, such as collaborative planning of community relocation. As

referenced in Context, several informal settlements lie within AMA boundaries and have vulnerabilities to climate-related disasters.44 By utilizing machine learning data, researchers were able to generate estimated boundaries for informal settlements, as captured in Map 3. While these boundaries may not be exactly correct, they give a sense of how far-reaching the informal settlements are, and, thus how important those communities are to decisionmaking.

19 8 | KEY ACTORS

MAP 3: Informal Settlements in the AMA45

ACADEMIA

Academic institutions play an important role in both the development of the urban climate agenda and engagement with informal settlements. Institutions such as the University of Ghana and the University of Cape Coast have already provided valuable research and technical assistance in the development of guiding documents such as the Accra Climate Action Plan, informing climate risk analysis and waste management procedures respectively.46

Interviews with representatives from the University of Ghana emphasized how academia can be both an effective and limited interlocutor when engaging with informal settlements about climate adaptation plans. For example, researchers from the University of Ibadan in Nigeria and the University of Ghana successfully engaged with informal waste collectors for a research project.47 This information was then used to develop a more formalized process of engagement with waste collectors. While this research has positive domestic impacts Ghanaian universities’ reliance on foreign funding can potentially tilt research away from explicit local priorities towards larger global interests.48

PRIVATE SECTOR

Private formal businesses and informal workers are key partners for the AMA in the delivery of services to its constituents. They are also an important MTDP of funds for the AMA through their payment of fees, property income, and licenses. In 2017, only 4% of solid waste was collected by the AMA, while 42% was collected by private sector companies and 29% was collected by “Kaya Bola,” or informal waste collectors who largely operate in middle to high-income areas.49 Still, a large fraction (between 10 to 26 percent) of solid waste remains dumped in the community.50 The AMA has started developing links with informal workers to close the gap in solid waste collection, thus providing a baseline for deepening engagement and developing a model for collaboration.

This list cannot cover the wide range of stakeholders who are working on and impacted by Ghana’s climate adaptation initiatives. It does, however, offer some perspective on both the wide range of interests involved and the unavoidable complexity of respecting the different priorities, perspectives, and societal power of all of these actors. Despite this complexity, a sustainable and equitable adaptation approach rests on engaging with all of these interests.

20 8 | KEY ACTORS

9 | ANALYSIS OF STRENGTHS AND CHALLENGES

In this section, we highlight three primary strengths that provide the foundation for effective implementation of climate adaptation plans in Accra. We also identify five challenges that might impede climate action. This following analysis orients the underlying need for our recommendations responding to Strategic Objectives 1 and 2.

This section describes those strengths and challenges, and the following section presents recommendations.

Strengths:

i. The AMA has built a climate agenda aligned with global climate priorities.

ii. Climate-related policies have been incorporated into the AMA’s local plans.

iii. The AMA engages with its residents on a regular basis.

Challenges:

i. The climate agenda is fragmented across departments and lacks effective coordination.

ii. The AMA faces budget and staff constraints as they seek to accomplish their ambitious climate plans.

iii. There is a low implementation rate of climate action priorities in the MTDP.

iv. Activities are not well-linked to strategic outcomes and impacts.

v. Current community engagement is focused on informing and consulting, rather than partnering and empowering.

STRENGTHS

i. Strength 1: The AMA has built a climate agenda aligned with global climate priorities.

Accra’s CAP links to national climate plans and global priorities, and has proved integral to

positioning the city as a leader in climate adaptation. The CAP maps out the path that Accra’s city government, citizens, and businesses must take to deliver an emissions-neutral and climate-resilient city by 2050, consistent with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. At the national level, Ghana has committed to unconditionally reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 15% by 2030, and by 45% by 2030 if certain conditions are met, compared to a business-as-usual scenario. Accra’s CAP lays out twenty priority actions to help limit global temperature rise to 1.5°C above the average preindustrial temperature.

Accra’s CAP is also aligned with the Paris Agreement’s global goal on adaptation (Article 7) through Ghana’s National Adaptation Plan in process. Adaptation plans and initiatives at the local level, like those around solid waste and wastewater and resilient buildings, will likely be integrated into the NAP. This means proactive climate change–induced adaptation planning at the city level could benefit city residents by translating the goals into the larger national plans. The NAP will ideally serve as a guide to address Ghana’s medium- and long-term adaptation needs, and Accra’s adaptation planning through the CAP and 100RC only facilitates greater collaboration and coherence.

Accra’s CAP is also aligned with the 17 SDGs, adopted by all UN Member States in 2015 as part of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The SDGs’ targets provide local governments with the global backing and resourcing needed to increase their capacities for effective climate change-related planning and management, particularly in lower middle income countries like Ghana.51

Additionally, by joining transnational municipal networks like C40 and 100RC, Accra has accessed knowledge sharing, formal support, and funding connections.

21 9 | ANALYSIS OF STRENGTHS AND CHALLENGES

ii. Strength 2: Climate-related policies have been incorporated into the AMA’s local plans.

Not only is the AMA climate agenda well-aligned with international and national priorities but it has also been mainstreamed into local development plans, particularly the Medium-Term Development Plan (2022-2025). In this process, the AMA localized the agenda based on the needs of its citizens.

This is reflected in the development priorities (chapter 2 of the MTDP), whereby AMA consulted with the community to prioritize issues based on their severity, intended benefits, multiplier effects on the economy, links to basic human needs and rights, and sustainable spatial development.

Based on this approach, several climate and environmental issues were identified as high priority: poor drainage systems were listed first, poor sanitation second, the recurrent incidence of flooding fourth, and inadequate dumping sites at nineteen. Taking citizens’ climate-related needs as input into development planning is a crucial component of responsive local government, and the AMA has built a strong foundation for this.

True to its prominence in the development plans, solid waste management in the AMA has seen real progress and holds promise to be a central piece of future climate adaptation efforts. The AMA has been included in a number of large projects focused on solid waste management, including the World Bank-funded GARID project, the Accra Compost and Recycling Plant, and the Waste Management Department’s plans for a waste-to-biogas plant. These projects demonstrate that the AMA has a history of understanding the importance of solid waste management. Moving forward, solid waste management has the potential to act as much of the foundation of the AMA’s climate agenda, perhaps even the central focus of climate action in the AMA, reframing an issue of public health within its larger plans for climate adaptation.

iii. Strength 3: The AMA engages with its residents on a regular basis.

Essential to the Mayor’s vision of shared responsibility for a new Accra is community engagement across local government programs. The AMA already engages with its residents on a regular basis to ensure its actions are representative of community interests. Traditionally, these engagements follow two dominant approaches. The first is sensitization or education efforts, which comprise a majority of the AMA’s engagements around policies and programs like promoting hygiene and sanitation.52 The second approach is less frequently practiced in isolated cases, where community actors are involved in the design-stage of policies. For example, in summer 2019, the AMA collaborated with residents of Old Fadama to organize an eviction agreed upon and carried out by the People’s Dialogue and other community organizations.53 The communitydesigned aspect of the AMA’s actions here defused tensions that otherwise would have been present in this difficult situation.

The Mayor’s leadership in community engagement efforts has pushed forward both normative and programmatic changes in how the AMA engages with informality. In September 2022, the AMA on behalf of the Mayor organized the first stakeholder conference geared towards deepening dialogue with the informal waste sector.54 The 19 elected Assembly Members and 6 government appointees in the three sub-metropolitan district councils also play a critical role in outreach to these areas.55

22 9 | ANALYSIS OF STRENGTHS AND CHALLENGES

“My vision is to build a new Accra; a model city whose inhabitants have a shared responsibility in making it modern.”

- Hon. Elizabeth Kwatseo Tawiah Sackey, October 7, 202156

i. Challenge 1: The climate agenda is fragmented across departments and lacks effective coordination.

The first challenge to implementing the AMA’s climate agenda is the need for more clarity around leadership, ownership, and coordination mechanisms. In the official structure of AMA which is prescribed by the Local Governance Act, 936 (2016), there is no department for climate change. During our field interviews, stakeholders pointed to different actors or departments responsible for the climate agenda, illustrating the challenge of ownership.

The AMA Resilience Unit, established with 100RC, was never institutionalized into the formal AMA structure, and the position of Chief Resilience and Sustainability Officer - created with 100RC - has changed hands about every 1-2 years. Even though the CAP defined the Resilience Unit as having the leading role, none of the AMA’s formal departments acknowledged this unit in our interviews. The CRO, C40 advisor, and Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety (BIGRS) officers are all currently externally funded and seem to be focused on special projects. The CAP also recommended reviving the Resilience and Climate Change Steering Committee to oversee the Plan. Yet, the Committee is still not operating, a reality that diffuses the monitoring and coordinating role.

Seeing as there is no permanent and clearly defined governance structure within the AMA to monitor and coordinate the climate agenda comprehensively and effectively, the result is a fragmented agenda across multiple departments responsible for various aspects of the climate agenda, like waste, transportation, energy, green space, and water management. Furthermore, the absence of a specific governance structure creates additional challenges for streamlining and harmonizing actions between departments, maximizing scalability gains, and preventing the

repetition of activities. Finally, the lack of a central department makes it harder to attract funding and resources from global partners, who are looking for focal points and progress reports.

ii. Challenge 2: The AMA faces budget and staff constraints as they seek to accomplish their ambitious climate plans.

While large fractions of the AMA’s budget come from the District Assembly Common Fund and the central government of Ghana, about half of the AMA’s annual 40 million GHS budget is generated internally.57 However, the dynamics of internally generated funds (IGF) appear to have changed with multiple rounds of decentralization, shrinking the AMA significantly. One AMA official noted that the AMA has lost a number of revenue MTDPs, including the airport and surrounding hotels that have challenged its ability to sustain itself through IGF. Additionally, the changing boundaries of the AMA have created confusion over, and at times conflict around, which local authority has jurisdiction, and therefore collection rights, over which area. The community’s eroded confidence in local authorities’ capacity to deliver services has made the collection of funds more tenuous.

Challenges in raising IGF make it difficult for the AMA to follow through on its CAP commitments. Based on our mapping of the climate-related activities in their MTDP and including 70 million GHS of expected donor funds not detailed within the budget, the city has allocated 73 million GHS for solid waste and wastewater. Additionally, the city has allocated 4.8 million GHS for transportation, 3 million GHS for mainstreaming the climate change threat in the development process, 880,000 GHS for land use and physical planning, and 30,000 GHS for energy, buildings, and industry.58 These significant monetary commitments will require significant capacity in IGF generation.

Clarifying the AMA’s jurisdiction and establishing a more trusting relationship with the communities it serves is crucial to improving its capacity to generate funds internally. However, this must be

23 9 | ANALYSIS OF STRENGTHS AND CHALLENGES

CHALLENGES

matched by building capacity in human resources.

Throughout our interviews, AMA heads of departments and personnel consistently lamented staffing shortages, sometimes connected to the loss of funds through decentralization. Moreover, political changes and low compensation have led to frequent staff turnover. Therefore, to meet staffing needs, departments draw significantly on national volunteers from the National Youth Volunteer Program. While these volunteers represent a pipeline of human capital, their low tenure makes it difficult to keep institutional knowledge within the AMA. This loss in knowledge is further compounded by a lack of clear dissemination of strategy from senior staff members down to the lower-ranking staff.

Ensuring the inclusivity of the work towards these climate adaptation commitments is another challenge. In addition to the community-facing staff of the Department of Social Welfare and Community Development, some AMA staff are designated community liaisons, and some are naturally involved in the community. This ranges from the Department of Social Welfare and Community Development to the Physical Planning department’s staff working in the field to catalog the city’s physical assets. Although these staff members might not be directly responsible for community engagement, their interactions with the community directly impact community members’ perception of the AMA. Therefore, it is important to build capacity across departments around community interactions. Identifying all community-facing staff members, training them, and enabling peer-to-peer sharing across departments could greatly improve the AMA’s community engagement capability. This is further discussed in Recommendation 4.

24 9 | ANALYSIS

OF STRENGTHS AND CHALLENGES

DEEP DIVE: CLIMATE FINANCE

The AMA’s limited budget and resources constrain its ability to carry out climate adaptation projects. Many cities in the Global South, like Accra, struggle to gain access to additional financial resources from outside MTDPs (public and private) to respond to climate change - financial resources often referred to as “climate finance.” Only 10-20% of global urban climate investments are funded by international financial institutions, UN climate funds, or private investors.59

City governments may face common barriers to accessing climate finance.60 For example, local governments struggle with the capacity to prepare project proposals, while the World Bank and UNDP cite the lack of appropriate projects as a barrier to scaling up urban climate finance. Projects need to be scoped within the administrative boundaries of city governments, an issue that may prevent the AMA from receiving funding for large infrastructure projects due to its limited geographic jurisdiction.

Increasing availability of subnational climate finance will require reforms at the national scale as well as potentially more innovative financing mechanisms; however, the AMA can take some actions to increase the likelihood of receiving funding. Accra has been able to successfully access external climate finance

resources through projects such as the C40 Cities Finance Facility (to conduct solid waste separation and community composting), the World Bank’s GARID project, the 100 Resilient Cities network, and other projects. Other Global South cities have found external support for project preparation facilities (PPFs) to be helpful in preparing projects. PPFs provide city governments with assistance to prepare project applications for financing. One example is through the Cities Climate Finance Leadership Alliance’s Project Preparation Action Group.61

In addition to being difficult to secure, external funding can lead to long-term risk for city governments. A reliance on external funding has contributed to the fragility of climate adaptation initiatives in Accra. The shuttering of 100 Resilient Cities meant that the three years of community engagement and hard work developing a plan was ultimately left behind. It is an indication of the risk governments face relying on private funding for such existentially critical work as planning for natural disasters, social shocks, and climate change. Additionally, the proliferation of plans backed by different funders has led to challenges with policy coherence, especially in the motivation and implementation of these climate adaptation measures.62

9 | ANALYSIS OF STRENGTHS AND CHALLENGES 25

iii. Challenge 3: There is a low implementation rate of CAP Priorities in MTDP.

The AMA’s Climate Action Plan has 5 priority areas: (1) solid waste and wastewater, (2) energy, buildings, and industry, (3) transportation, (4) land use and physical planning, and (5) mainstreaming the climate change threat in development processes. For each priority area, there are specific actions and detailed sub-actions.

Through a mapping process in which we reviewed the AMA’s MTDP 2022-2025 document to assess how much of the city’s Climate Action Plan is reflected in their development plan (Figure 5), we determined only about 20% of CAP sub-actions are included in the MTDP as of 2022.63 This shows the gaps between planning and implementation.

As of 2015, the majority of Accra’s emissions came from waste (44%), transportation (30%), and stationary energy (26%). In line with the top priority area, solid waste and wastewater have the highest

number of activities and associated budget in the MTDP. Out of the 27 sub-actions on solid waste and wastewater, 10 are being implemented giving a 37% implementation rate.

By comparison, only 13% of committed transportation and stationary energy sub-actions in the MTDP have been implemented. This presents an opportunity for the relevant AMA departments, such as Transport, Road, and Physical Planning Departments, to align their activities with the CAP.

“Mainstreaming the climate change threat in the development process” is the last CAP priority area, and is muddled among roughly seven different departments implementing community engagement activities. Although this shows that the city recognizes the importance of engaging the communities, most of the citizen and community engagement activities in the MTDP are focused on public education and awareness. A deeper and more meaningful community engagement would improve participation and community buy-in on the city’s climate campaigns and action.

26 9 | ANALYSIS OF STRENGTHS AND

CHALLENGES

FIGURE 5: Mainstreaming AMA MTDP and CAP

Source: Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA), & C40 Cities. (2020). Accra Climate Action Plan: First Five-Year Plan (2020-2025).

Percentage of Climate Action Activity Ref lected in the 2022 Plan

iv. Challenge 4: Activities are not linked to strategic outcomes and impacts.

Taking a closer look at the Accra CAP and the MTDP, it is noticeable that many activities listed are broad and at a high level. As a result, many of the actions still need further planning before they can be implemented effectively. Moreover, many activities do not have specific indicators or milestones, making implementation and monitoring more challenging. For instance, several actions presuppose the elaboration of new plans or strategies.

Of the 35 climate-related activities in the MTDP, only 3 activities have an output indicator. For example, the Waste Management Department plans to “integrate 300 informal waste workers into plastic waste separation in selected communities and institutions in Ga Mashie and Korle Gonno.” This activity demonstrates a clear target community and number of people to be integrated. Adding reasonable indicators also allows for better planning, targeting, and budgeting of activities for maximum impact and effective use of resources.

However, for most of the activities in the plans, there was no mention of specific targets. For instance, the National Commission for Civic Education plans to “educate the public on environmental sanitation”, but their target was not specified. Similarly, the Metro Public Health Department broadly put “create public awareness on channeling of effluent through drains” with no mentioned indicator. Although the division of the country aims to bring services closer to citizens, in the case of the AMA it has also diminished its capacity to raise revenue and has increased the challenge of implementing programs and projects, as revealed by many governmental officials during stakeholder interviews.64 At the same time as resources and capacity were diminished, the AMA is still expected to be both the local implementer of central government policies and the primary administrative authority for its constituents living across both formal and informal settlements. Particularly regarding climate adaptation projects, the challenges are not restricted to the AMA’s new limited boundaries,

which increases the difficulties of implementing and leading the local climate agenda.

With diminished boundaries and fewer resources, the biggest challenge is ensuring that the AMA has the institutional capacity to address climate change while meeting the needs of the most vulnerable populations.

“Why do cities keep producing these frameworks without leaving special amounts for their implementation? [...] Municipalities have all these documents, and we are left to implement them.”

v. Challenge 5: Current community engagement is focused on informing and consulting, rather than partnering and empowering.

While the AMA has invested significantly in community engagement, it has generally done so through informing, consulting, and sometimes even involving in planning.

However, marginalized populations are rarely placed at the center of planning; in other words, included in the design stage. This means current community engagement appears to be primarily one-directional. This can be analyzed through the Locally-Led Framework aforementioned, and the AMA Community Engagement Ladder in Figure 2.

For example, in Old Fadama, government-ordered demolitions removed more than 7000 people in 2003 and 2006, and sediment removal from Korle Lagoon removed another 1000 in 2020. While authorities were trying to help, they did not collaborate or empower residents, unlike their collaborative eviction in 2019, thereby failing to realize the strong tie residents have to Old Fadama beyond just housing - it is also a center of employment, culture, and family.

27 9 | ANALYSIS OF STRENGTHS AND CHALLENGES

- Eden Tekpor Gbeckor-Kove, Head of the Physical Planning Department, AMA, 2021

OF STRENGTHS AND CHALLENGES

Another example is Ghana’s flood forecasting and early warning systems. The National Disaster Management Organization and local governments coordinate the flood early warnings, preparedness, and response and recovery activities with the local communities. However, according to our interviews, these activities often fail to reach the last mile on time, and even if they did, there are few officially designated safe havens for flood victims. This means that the important investment in critical early warning systems is not reaching the people who need it most – a challenge that may have been mitigated with more active partnerships with the community in the design stage.

Additionally, infrastructure investments have dominated adaptation approaches, relegating community engagement to a secondary tier. Several large-scale adaptation initiatives are underway, including drainage investments, expanding access to energy-efficient building materials, and paving alleyways in informal settlements. However, most initiatives do not address the realities of the informal areas of the city. For example, the bulk of the $200 million World Bank-financed GARID project is focused on rehabilitating infrastructure to improve the management of the Odaw River.65 Even though there is $7 million designated for community

engagement, it has consisted of design consultations and stakeholder engagement workshops postdecision-making about the infrastructure.

Maladaptive outcomes are unfortunately quite common in addressing the impacts of climate change, and often arise from the failure to comprehensively consider vulnerability, the lack of inclusive participation, the retrofitting of adaptation project goals to match existing development efforts, and the tendency to insufficiently conceptualize ‘adaptation success.’66

A systematic review of climate responses in African cities from 1980-2019 found 52 examples of maladaptation - most pertaining to managing excess rainfall, and many relating to how funding is channeled to wealthier neighborhoods due to lack of oversight and transparency.67 In order to avoid this outcome, it is critical to center the community. Studies have shown inclusive planning leads to higher climate equity and justice outcomes.68

This analysis of both the strengths and challenges of the AMA’s approach to climate adaptation have led us to the following recommendations to address the strategic objectives, guided by the frameworks outlined in the methodology section.

RESPONDING TO COMMUNITY FEEDBACK ON INCLUSION IN CLIMATE AGENDA

In a federation-wide meeting facilitated by People’s Dialogue in October 2022, heads of informal settlement savings groups raised the issue of the lack of consistent enforcement of sanitary and building regulations by local officials. While they recognized that individuals had a responsibility to abide by local regulations, they blamed local authorities for allowing people to circumvent them.69

Furthermore, meeting participants perceived local authorities’ engagement with the community to be too technocratic and dismissive of their knowledge. According to them, community officers engage too late, when decisions have already been made, and not frequently or widely enough (i.e., they only engage a few representatives rather than understanding the heterogeneity of the community). This leads to a feeling of apathy among community members who see the

government’s engagement of the community as a checkmark to satisfy external stakeholders. We encountered a similar discourse among other local civil society actors regarding the local government’s community engagement practices.

Youth groups like the Ghana Youth Environmental Movement, for example, have taken on the issue of climate change in Accra. Although they are invited to partake in climate related events by the government, youth groups frequently feel like their concerns are not taken seriously by the government. Similarly, Ghanaian academics from institutions like the University of Ghana provide technical expertise that can help guide the climate agenda. However, international expertise, primarily from institutions in the Global North, is often prioritized over local knowledge.

28 9 | ANALYSIS

10 | RECOMMENDATIONS

This section presents our recommendations to help the AMA better implement its climate adaptation agenda. The AMA will need to implement a combination of strategic and community-based interventions as well as construct additional infrastructure to improve solid waste management and reduce flooding in Accra. Our research and recommendations in this report focus on our 2 Strategic Objectives (detailed in the Introduction):