Carl Densem

Steve Lindo Principal, SRL Advisory Services and Lecturer at Columbia University

Manager, Financial Markets, Rabobank SPONSORSHIP

PRMIA’s Intelligent Risk is distributed to more than 40,000 risk professionals worldwide. If you would like information about the various sponsorship opportunities available, contact sponsorship@prmia.org.

US ON prmia.org/irisk @prmia

Carl Densem Editor, PRMIA

Carl Densem Editor, PRMIA

Steve Lindo Editor, PRMIA

Steve Lindo Editor, PRMIA

Following on from the last issue’s look at risk culture, we turn outwards in May to scan for geopolitical risks. The capstone article is written by a veteran in this area, Karim Pakravan, on “Measuring Geopolitical Risk.” His article offers risk managers who feel under-prepared to assess the potential consequences of the resurgence of armed conflict (deaths in conflicts are at a 30-year high) a systematic approach to collecting data, scanning for threats and preparing a risk management playbook.

On the unrelenting topic of climate risk, Nadia Al Qassab offers her thoughts on how the Basel framework will need to change. Fraud is given a new look by John Thackeray in the light of a post-COVID wave of internal fraud concerns. Two new topics are addressed by Gary Wright (T+1) and Svetlana Borovkova (energy transition risks in residential mortgages). In the fast-growing area of AI’s capabilities and risks, Dr. Rout takes a look at how AI and machine learning are evolving on both sides of cybersecurity: attacks and defenses. Mal Gloyer is back with a machine learning-enhanced delta hedging approach.

We’re also seeing the impact of AI in some of our editorial work, in the form of greater use of genAI in submissions we receive. In fact, we used it ourselves in this issue to generate properly formatted APA references, after verifying that no hallucinations had crept in. We haven’t yet established a policy on its use in Intelligent Risk, preferring instead to adopt a commonsense approach in which AI use is (1) limited enough so that authors can still call their submissions their own work, and (2) acknowledged where needed. In this issue, several authors told us that they used AI in the research phase and for picking up on grammatical errors. We look forward to seeing how authors (and we) can best use this powerful technology going forward.

If you’re interested in sharing your thoughts in a future Intelligent Risk or providing feedback on something you read in this issue, we welcome your emails to iriskeditors@prmia.org.

Synopsis

Managing geopolitical risk is a growing skill priority for risk managers. This article describes the key definitions and classifications necessary to understand it and some existing metrics used for its measurement. As a practical tool for risk managers, the author introduces a dashboard that facilitates the tracking of relevant geopolitical risk indicators and provides a live example of its use in tracking the potential evolution of the Israel-Hamas conflict.

the what, how, how much and how likelyby Karim

Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!

-Monty PythonWith the world mired in poly-crises, geopolitical risk is currently at the fore. Yet, it has never been absent. My 30-year plus as a practitioner of country risk analysis and analyst of global economic and financial issues have led me to consider that geopolitics are inescapable factors in our interconnected and globalized world, an essential background factor underscoring both risks and opportunities in the global economy, in good times as well as bad times. The following analysis discusses the various dimensions of geopolitical risk, its measurement, management, and mitigation.

According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, geopolitics is “…analysis of the geographic influences on power relationships in international relations. The word geopolitics was originally coined by the Swedish political scientist Rudolf Kjellén about the turn of the 20th century, and its use spread throughout Europe in the period between World Wars I and II (1918–39) and came into worldwide use during the latter a.”

The World Economic Forum (2024) defines global risks as “…the possibility of the occurrence of an event or condition which, if it occurs, would negatively impact a significant proportion of global GDP, population or natural resources.”

In developing a geopolitical risk assessment framework, we have to distinguish between short, medium and long-term horizons. Short- and medium-term risk in turn are enfolded in broader trends and developments, each of which have a varied impact. Since the 1980s, we have seen several distinct periods: the developing countries debt crisis of the 1980s; the collapse of the Soviet empire and the end of communism in the 1990s; globalization and the integration of China in the global economy over 1989-2007; the global financial crisis and the Great Recession of 2008, and the global fragmentation that followed; and finally the era of COVID pandemic shock, recovery and acceleration. Finally, we have to distinguish between ongoing geopolitical risks and one-off shocks.

For policymakers or captains of industry, geopolitical risk assessment and management ultimately comes down to the “what, how, how much and how likelyb?” “What” means identifying a geopolitical risk; “how” means how does the risk affect a given situation; “how much” estimates how much it impacts the situation; and “how likely” gauges the likelihood of its occurrence. The “how” and the “how much” look at the channels of transmission of risks. Furthermore, in assessing the channels of transmission of adverse geopolitical risks, we have to distinguish between the macro and micro impacts.

At the macro level, adverse geopolitical events will impact the economy through inter-related macroeconomic and financial market shocks. On the macroeconomic side, we can see impact on output, employment, and inflation. On the financial market side, we can see a surge in volatility, as well as adverse impacts on stock markets. Furthermore, economies and markets can suffer from second and third round disruptions, such as credit crunches and banking crises. For example, the oil shocks of the 1970s resulted in global stagflation, surging interest rates and ultimately a global debt crisis and a stock market crash.

At the micro level, we can see issues such as supply chain disruptions, loss of access to resources, inputs and markets, labor unrest, expropriation, and violence. The COVID pandemic resulted in major disruptions in global trade and supply chains, as well as an acceleration of the fragmentation of the global economic order. The war in Ukraine initially impacted energy flows between Russia and Europe, as well as the global trade in wheat and other cereals. The more recent Israel-Hamas conflict has threatened to disrupt shipping flows through the Bab-el-Mandeb Straits and the Red Sea. In each of the above cases, the microeconomic impact has morphed into a macroeconomic impact. For policymakers and corporate strategists, the analysis of these risks goes back in each case to the “what, how and how much.”

b

The starting point is to realize that we are dealing with a probabilistic world. In the immortal words of former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, “There are known knowns, things we know that we know; and there are known unknowns, things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns, things we do not know we don’t know.” We can try to assign statistical probabilities to the known unknowns, but we have no model for the unknown unknowns.

In this context, risk measurement is essentially an exercise in scenario building. Scenarios are in turn driven by our risk analysis framework and methodology. There are two interrelated approaches to geopolitical risk: quantitative and narrative. The quantitative approach is based on developing indices of risk based on the aggregation and scoring of individual components. These indices in turn are used as leading indicators of potential risks, often accompanied with probabilistic assessments, leading to the development of specific scenarios and policy and strategy responses.

An example of this approach is the Geopolitical Risk Indicator developed by BlackRock (BGPRI). This indicator is based on a dashboard of 10 top geopolitical risks. The BGPRI index is derived from the frequency of mentions in brokerage reports and the financial press associated with each risk. The indicator provides an aggregate risk index that is then used to develop a risk map and scenarios. In a similar vein, Caldara and Iacovello (2022) developed a geopolitical risk index (GPR). The GPR is based on text-mining: searching news articles for pre-determined words. The authors used econometric analyses to study the impact of these risks on the macroeconomy over the period 1985-2019.

These text-mining models are based on the ability to extract information from a massive amount of news articles, which increasingly involves the use of natural language processing. Other risk analysts such as McKinsey rely on frequent communications to the C-Suite and Boards. Significant geopolitical risks are assessed and scenarios developed. Risk management relies on answering the following questions: “how did we get here; where are we now; where are we headed; and, what to do about it?” Furthermore, responses are based on three time horizons: short, medium and long-term. The World Economic Forum (2024) uses surveys of expert opinion to construct a Global Risk Perceptions Survey (GRPS) based on four dimensions: Risk Landscape, Consequences, Risk Governance, and Outlook, and complement the GRPS with an Executive Opinion Report.

These risk indicators provide useful metrics for management and policymakers. However, they are by-andlarge coincident or lagging indicators and need to be complemented by narratives and expert opinion. A systematic and forward-looking approach to design, implement and monitor risk indicators can involve a matrix approach that identifies potential event risk, as well as projects current event risks. The risk matrix, or dashboard, for a specific event would typically include the following items:

• A background narrative

• Time-horizon (short-, medium-, or long-term)

• Indicator(s) (trigger event(s) to be monitored)

• Indicator calibration: determined by expert opinion

• Likelihood (low-medium-high, or scoring such as -3 to +3)

• Impact (low-medium-high, or scoring such as -3 to +3)

While established methods are useful in providing easy-to-understand risk markers, they are essentially providing lagging or at best coincident risk indicators. Geopolitics deals with layered and complex situations where the identification and ranking of risks requires a historical narrative. This is why the knowledge of history, an often-neglected dimension of the problem, is an essential building block for understanding the risks. The history of a country or a region and an understanding of the long-term dynamics are essential to analyze the reaction functions and underlying trends. History and culture define the problems and underlie the motivations and reactions of the major players. Moreover, just like the unexpected arrival of the Spanish Inquisition in the British comedy skit show of the 1970s Monty Python, we have to expect the unexpected, characterized by Nassim Taleb as “black swans”—aka the unknown unknowns. The unexpected is the grist of geopolitics.

Furthermore, while scenario-building is useful, it is often too simplistic. To start with, we have seen repeated intelligence failures by the most sophisticated intelligence agencies in the world. Ultimately, geopolitical risk analysis is about resilience and sustainability. Typically, analysts try to develop best case-most likely case-worst case scenarios, but experience shows that what really matters is the worst case and that’s what should drive policies. When dealing with unknown unknowns, the keys are flexibility in response and contingency planning.

Finally, we should recognize that geopolitical risks do not appear out of the blue, but usually have a long gestation period. However, they become “operational” if a trigger is released. To paraphrase Hemingway, speaking about his many personal financial bankruptcies, geopolitical risks happen gradually, and then suddenly. Therefore, an important part of the risk management function is to monitor the “gradually.”

Conflicts in the Middle East have long been considered as key geopolitical risks: the Yom Kippur War of 1973, the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-88 each had a major impact on the global economy, inaugurating a period of stagflation, high interest rates and multiple banking crises. The purpose of the following analysis is to identify the “what, how, how much and how likely” posed by the conflict to the global economy.

The What: The Israel-Hamas War goes beyond the two warring parties and has involved both regional (Iran, Iran-supported militias, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Egypt) and global (United States) players. Iran plays a key role in the regional picture.

First, regardless of the nature of the regime, whether the late Shah’s imperial rule or the Islamic Republic, Iran considers itself the natural regional hegemon. Secondly, the Islamic Republic’s ideology is based on two important pillars of profound hostility to both the United States and Israel. Third, in the past few years, the Iranian regime has developed what it has called “the axis of resistance” by sponsoring and supporting non-state actors: Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, Hamas and Islamic Jihad in Gaza and proIranian militias in Iraq. At the same time, the Iranian regime is pragmatic and bent on its own survival. As such, Iran seems unwilling to escalate the conflict with the United States to a full-scale war and has had a muted response to US retaliation against attacks on American assets in the region.

Qatar has also emerged as another important regional player, acting as an honest broker between the US and Israel on one side and Hamas on the other. As Israel’s main ally, the United States is a key element of the risk equation, balancing its support for Israel with a push for a ceasefire by a reluctant Israeli government.

The How: In this section, we consider what is the potential macro- and microeconomic impacts of the conflict. At the macroeconomic level, the mechanism of transfer of shock is largely through oil prices, in particular the impact of prolonged oil price spikes on output and inflation. In addition, supply chain and shipping disruptions have an adverse impact. At the microeconomic level, the main impact is through supply chain disruptions, higher costs, and loss of access to resources and markets.

The How Much: So far, the main impact of the conflict has been disruption of shipping through the Bab-elMandeb Straits and the Red Sea (which lead to the Suez Canal) as a result of sporadic drone and missile attacks by the pro-Iranian Houthi militias. This has forced the rerouting of some global shipping routes from the Suez Canal to the longer route along the Cape of Good Hope, resulting in a sharp increase in shipping costs.

Oil markets remain buffeted between the winds of war and some optimism about a Gaza ceasefire. Nevertheless, on balance, the oil markets remain shielded from the conflict for the time being. Despite a half a million barrels per day cutback in OPEC production, the markets are well supplied, inventories are high, and demand remains weak. These factors are offsetting geopolitical risks, which seem to be contained, at least in the short term. In the longer term, the major players: Iran, the Saudis and The United States, have an interest to keep the oil supplies flowing. Given the oil medium-term fundamentals, oil markets are expected to stabilize at around USD $80/barrel for Brent over the next few months.

The How Likely: Given the interests of the major players and their efforts to avoid moving to the brink, the more extreme negative scenarios remain low risk (10-20%). At the same time, there is no overwhelming pressure to resolve the conflicts, and positive outcome scenarios are at best 50-50.

Below is a matrix-based model to assess the potential developments in the conflict. In what follows, I list some potential short-medium scenarios. On the positive side, an extended ceasefire; on the extreme negative side, an oil embargo, and a direct US-Iran or Israel & US-Iran conflict.

2024 is expected to be a turbulent year. In addition to the aforementioned catalog of geopolitical risks, we are facing a busy electoral cycle—50 elections worldwide—including the all-important US presidential contest. The potential for an expanded conflict in the Middle East is almost certainly in the cards. Moreover, a Trump presidency could lead to an escalation of the Iran-US tensions.

In this context, the main known unknowns would be a major disruption in oil flows from the Middle East tied to an escalation of the conflict. In the case of shipping disruptions and oil supply interruptions, governments and businesses can evaluate the worst-case scenarios and build their defenses. Once again, the key is resilience.

references

1. BlackRock Institute: “Geopolitical Risk Dashboard” December 15, 2023

2. Caldara and Iacovello (2022): “Measuring Geopolitical Risk” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, International Finance Discussion Papers, ISSN 1073-2500 (Print)

3. McKinsey: “How Global Companies Manage Geopolitical Risk” July 15, 2021

4. World Economic Forum (2024): “Global Risk Report” 19th edition

author

Karim Pakravan

Karim Pakravan is a global strategist with a lengthy career in international banking and academia as a country risk and global financial analyst and lecturer. Pakravan has written extensively on global risk issues, as well as global finance and banking. He holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Chicago.

peer-reviewed by

Steve Lindo

Synopsis

The imminent implementation of T+1 settlement in the US capital markets poses systemic risks for other jurisdictions. In this article the author explains the potential repercussions of this intended improvement, together with some mitigating steps and solutions.

Trade date plus one day (T+1) kicks off on May 27th and 28th in the US, Canadian and Mexican capital markets. This is causing major concerns to international investors, because most other major markets operate at T+2.

The US capital market is matched by the UK as the largest international capital market by trade volume, value, and issuer listings. So, asynchrony between the settlement timing of these two markets does not auger well for investors who invest their portfolios in each, in particular because market infrastructures are totally different in the USA, the UK and EU.

In the USA there is a close vertical alignment between the New York Stock Exchange, the DTCC and the Federal Reserve, with the SEC providing regulatory oversight. Settlement is very straightforward, with the DTCC – as depository – holding all the shares and electronically moving shares between buyer and seller via a netting process. The Federal Reserve moves money electronically to pay and receive based on data provided by the DTCC. All this is performed by overnight batch processing. So T+1 with shares and cash effectively within the same system is imminently achievable.

However, in the UK and EU the closely aligned vertical model in the USA is replaced by a horizontal model where market players can choose what platform to execute trades on, where to clear and settle. Share inventory can be with nominees at brokers, wealth managers or private banks and a number of custodians. Settlement supply chains can be long and include various settlement agents. In the international market this includes FX transactions.

EFAMA, the huge trade association in Europe that represents the vast majority of the fund industry, conducted a member survey in Europe and stated that T+1 in the USA will produce a significant increase in operational costs for its members as a result of T+1. EFAMA said that a survey of member firms which manage €28.5 trillion (USD $31.06 trillion) in assets found that, under the new U.S. T+1 settlement system, 40% of asset managers’ daily FX trades would have to settle outside the safety of the CLS multi-currency platform. “On a regular trading day, this could amount to USD $50-70 billion. In volatile markets, this figure could be in the hundreds of billions.”

CLS (Continuous Linked Settlement) is key to the efficiency of existing FX mechanisms and risk reduction. CLS was set up by major global banks to reduce their FX risks by netting off transactions internationally. Any individual who has performed an FX trade in any of the 18 currencies which CLS nets will have been indirectly impacted. The risk reduction which CLS offers financial services is massive, with capital market transactions only accounting for a single figure percentage of daily volume.

However, the cutoff times within which fund managers operate to enable them to perform their services make it almost impossible to transact and execute in enough time. CLS has not yet stated if they will change their processing deadlines to mitigate this looming problem. However, even a delay of a few hours will only make a small difference.

Most fund managers and asset managers outsource FX execution and settlement to their custodians, with a few executing transactions themselves. No matter which timescales and cut off times CLS operates, execution and settlement will get squeezed into a few short hours. Operationally, doing this using batch systems which need 100% data accuracy is a very difficult task. Logic says failed settlements in the equity/ bond or related FX markets will increase. Possibly significantly.

Solving it might be beyond the markets in the short or even medium term, as batch system technology and time zone issues with a strict CLS cut off time make it next to impossible. Longer term, a total revamp of technology and market structure would be required. Ultimately, this might open the door for distributed ledger technology to provide a solution.

Mitigation is the most practical approach in the short term, and this probably entails outsourcing all FX execution and settlement to a custodian bank. Unfortunately, this mitigation will incur increased costs and possibly wider FX spreads, as banks will not be taking on the added operational and business costs and risks without reward. However, it looks like the only solution for firms.

With May looming for T+1 in North America, the capital markets do not know how big and where the greatest impact will be. This is equivalent to a huge experiment with hope as a key feature. It is perverse that an industry that prides itself with understanding and managing risks is inflicting so many known unknowns on itself that could produce unintended consequences. This risk being generated by the capital markets will affect everyone, but most people won’t know it.

EFAMA further affirm in their statement that “This is of systemic importance,” adding that the European Central Bank, as well as U.S. regulators and the Federal Reserve, should require CLS to extend its cutoff for completing a currency transaction. Increased FX settlement risk carries systemic implications, EFAMA said, citing the collapse of German bank Herstatt in 1974, which caused a major chain reaction across the world as it left large FX trades unsettled.

The mere mention of Herstatt Bank will send most bankers of a certain age into a cold sweat. In 1974 this medium sized German bank almost brought down the global banking system. Today a similar event would do the same, if the safety barriers introduced over decades are rendered ineffective because of CLS limitations and T+1.

The systemic failure that could ensue would be greater than we have ever experienced. We do not have in place any defense other than the world’s central bankers and regulators, paired with potentially panicstricken governments and hastily arranged emergency lifeboats. We don’t need very long memories to appreciate what that looks like.

The painful truth is the T+1 implementation decided by the SEC in New York because of a regulatory breakdown may have inadvertently created the greatest systemic threat the financial markets have ever seen.

The worry is that we don’t know. In May we will be lighting a T+1 touch paper where we do not know what will happen. Optimists believe that it’s just a technology upgrade and getting used to new practices. Pessimists see it as opening a Pandora’s box of unintended consequences. Put another way, one of the four horsemen of the apocalypse in risk could be unleased. Systemic risk should at the top of our worry list come June 2024.

Gary Wright is Director of Industry Affairs at ISITC Europe. He recently conducted an academic research project on T+1 and is on the UK Accelerated Settlement Technical Taskforce steering committee. Gary is highly sought after for his views and advice on the impacts on business and operations of market and regulatory changes. Since 1969, he has held senior positions within several major financial institutions, participated in many industry committees, and acted as advisor to several leading suppliers. He has spoken at, chaired and moderated a considerable number of events globally. His blogs, articles, whitepapers, and reports are published worldwide.

peer-reviewed by

Steve Lindo

Most researchers argue that the first climate risk impact in the banking industry will be to business departments. However, risk management professionals can beg to differ, for the simple reason that without a risk management policy, Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) and risk monitoring units, business departments cannot execute any transaction. Hence the role of risk professionals is vital in mapping out the risk management practices and paving the road for other departments in the bank to execute their role within the risk tolerance level and mandates of the board. This leads to a thought-provoking idea: how are risk management practices evolving to accommodate sustainability practices and climate risks alongside business needs?

Indeed, the pressure on risk professionals is mounting given that the economic outlook forecasts increasing credit losses and, therefore, an increasing need to manage risks in order to enhance profitability. Since the risk spectrum is interconnected, other risks such as regulatory risk, strategic risks and others may emerge if a holistic review is not performed.

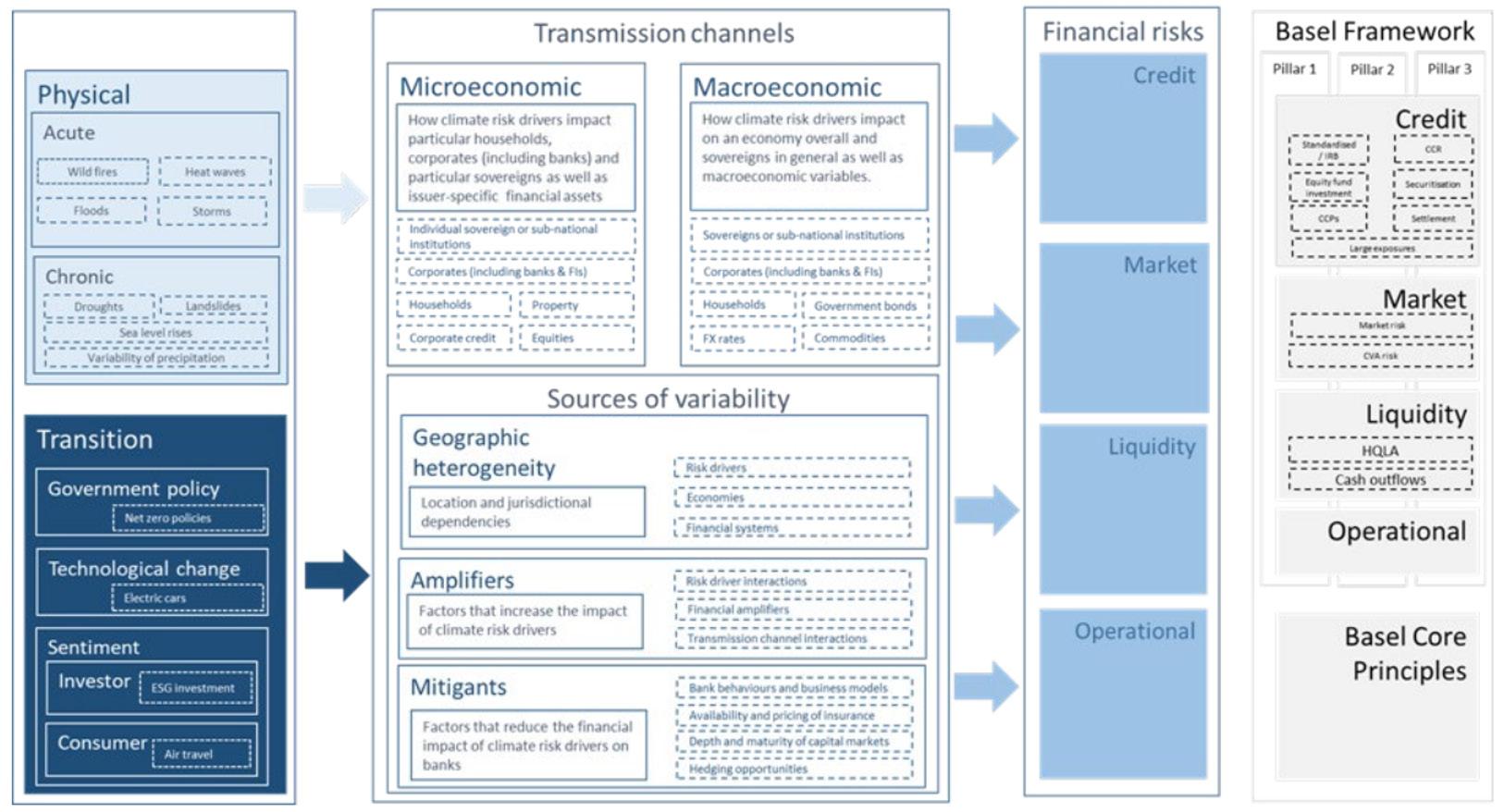

Climate risks reach beyond just rising ocean temperatures, for banks they are detrimental to the full array of traditional risk types. To understand how, this article explains the sources of climate risks, their transmission through Basel’s three pillars, and the final impacts on capital for market, credit and operational risks. Synopsis introduction background on Basel

A reference for mapping out the overall changes and the holistic review on risk management practices is the Basel Framework developed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). Basel Framework is divided into three distinct categories Pillar 1, Pillar 2, and Pillar 3.

Pillar 1 establishes the minimum capital requirements in accordance with the regulatory view while Pillar 2, the supervisory review process, details risk management governance and risk tools. Lastly, Pillar 3 describes market discipline, which includes transparency and reporting. All three pillars will be impacted by sustainability and climate risk going forward.

Incorporating climate risk into Pillar 1 involves identifying and assessing any gaps in the current structure and incorporating climate risks into the existing capital calculation framework. For instance, for credit risk this means enhancing the counterparty risk exposure and integrating climate risks into the internal credit scoring system while analyzing the external risks. Figure 1 exhibits the mapping by DeNederlandsche Bank (DNB) of the main risks affected by climate risk.

Additionally, identification of climate risk also includes assessing and incorporating physical and transition risks. Physical risks are those risks that impact the organization in the physical world, such as wildfires and earthquakes. The second type, transition risk, includes the impact of climate risk on the process of transforming into a climate-friendly model, such as the risks from policy and legal, technology, market, and reputational sources. It is worth mentioning that there is always a positive side to climate risks opening up such opportunities as greater energy efficiency, tapping in new markets and increasing business resilience.

Physical risks can be further classified into acute or chronic risks. Acute risks are sudden, event driven risks or hazards, such as earthquakes and floods, whereas chronic risks are usually longer-term impacts of climate risk, such as the sea level rise.

Figure 1: An overview with examples on how climate change can be a driver of conventional risk types (DeNederlandscheBank, November 2019)As described above, it is vital to incorporate sustainability concepts into risk management practices. To incorporate climate risk into the overall risk management practices, a top-down analysis starting with the overall risk management appetite and on to policies and procedures, stress testing, KRIs, internal and regulatory risk reporting should be conducted. Climate risks will impact the minimum capital requirements by impacting the RWA calculation as detailed in the Basel publication “Frequently asked questions on climate related financial risks” Published in December 2022. To clarify the impact on each risk, below is a detailed breakdown of credit, market and operational risks and impacts on Pillar 1. Figure 2 displays the impact on Basel III pillars.

Credit risk is considered banks’ largest area of concern, and since banks are revenue driven, their main concern is how climate risks will impact the credit risks of clients, i.e. the risk of customer default. According to Basel, the calculation of risk weighted assets (RWA) for credit risk is impacted going forward to the extent that the risk profile of a counterparty is affected by climate-related risks. These risks should be integrated into their own internal credit risk scorings or when using external ratings in the form of ESG ratings.

Figure 2: Impact on Basel Three pillars (BCBS, April 2021)Climate risks will impact credit risk management significantly. Current credit scoring assesses the creditworthiness of clients and the newly developed ESG scoring is used to assess the compliance of the organization to ESG pillars. Although ESG ratings have negligible impact on the lending and investment decisions now, they are gaining importance and momentum.

Overall requirements for calculation of RWAs for credit risk include probability of defaults (PDs), loss-given defaults (LGDs) and exposure at default (EAD). All three metrics should incorporate the relationship between climate risks and financial risks.

Market risk management

Market risk is the external risk of uncertainties due to financial market conditions that can impact a firm, similar to interest rate risk and foreign exchange risks. In order to adequately assess the market risk of a given investment or portfolio, banks should consider incorporating material climate related risk drivers in their stress testing models. Banks should measure the impact of those risks on their market positions, correlations and the pricing and availability of hedges.

Operational risk management

Many operational risks are directly triggered by sustainability risks such as failures in strategy, legal disputes, operations, reputation, systems, processes, people and many more. Strategic risks can stem from firms that either opt out or lag in implementing sustainability initiatives and this can trigger operational risks from non-compliance with regulatory guidelines, incurring legal risks as well. Operational risks can also stem from external events that can directly affect the firm’s operations, such as floods and earthquakes i.e. acute risks.

Calculation of RWA for operational risk, according to Basel, involves additional analysis to identify and incorporate losses stemming from climate-related risks identifiable from the loss database; these losses can be mapped to the event type category “Damage to physical assets”. A bank that misrepresents sustainability-related practices or the sustainability-related risks of its investment products could face litigation; this is classified as (event type category “Clients, products and business practices”).

Banks are required to assess the impact of climate-related risk drivers on their operation and the continuity of their operation. This can impact their business continuity plans.

In Pillar two, supervisors are required to evaluate and determine banks consideration of material climate related risks in their reporting, business strategy, governance structure and internal reporting.

Management and Governance: Most prominent is the need to formulate a subcommittee within the board assigned to resolve sustainability issues. Moreover, it is good practice to appoint a chief sustainability officer (CSO) with a designated team; however, some banks approach this by adding this role to an existing employee that either has a strategic or risk role. It should be noted that creating a governance structure should be in line with the size and complexity of the bank.

Risk Appetite Document: The risk appetite statement is a tool used to assess the amount of risk to be taken in pursuit of objectives, or risk-to-reward mechanism within an organization. Integration with sustainability risks is implemented qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitative changes include embedding positive screening (encouraging and selecting investments based on positive ESG criteria) and gradually phasing out investments that are fossil fuel intensive. On the other hand, quantitative features include measurable data which can be used for monitoring and decision making. Examples include calculating the emission level, portfolio warming potential, and targeted increase in renewables financing.

Risk Management Policies: Incorporating sustainability and climate risks into the existing set of policies and procedures is inevitable; so is introducing new policies and procedures to enhance the framework. Impacted policies include introducing or enhancing the climate risk management policy (part of the corporate social responsibility policy), incorporating sustainability into the lending policies and investment policies to encourage positive screening, enhancing the corporate governance policy to include the new sustainability responsibilities and roles as mentioned above, enhancing HR policies to include employee and diversity policies, introducing sustainability reporting to stakeholders and ensure stakeholder engagement.

Most banks should prepare an environmental and social risk management (ESRM) policy, which includes revamping and creating sustainability related policies regarding: setting the risk management framework, client onboarding policies, product development policies, transactional level policies, portfolio level policies and supply management policies.

Stress Testing: Basel, in its paper “Principles for the effective management and supervision of climaterelated financial risk,” published in 2022, directed banks to use climate scenario analysis (CSA). Designing an effective CSA requires that banks incorporate scenarios in plausible pathways. These pathways should incorporate short and long term, adjust to business size and complexity. Various examples such as the ECB, Fed and DNB devised stress testing and scenario analysis as detailed below.

According to the ECB, it was proposed to extend scenarios to include transition risk, whereby one is orderly (a structured and easy transition towards Paris agreement targets), while the second is disruptive (quick transition towards Paris). As with physical risks, the ECB stated in its papers how to assess the physical risks and how it will affect the client portfolio and any collateral associated with it. (ECB, 2024)

The US Federal Reserve incorporates stress testing by formulating a climate risk factor, or Climate Beta, that is inversely related to the portfolio impacted by transition risk and ultimately measures stock return sensitivity. Another metric proposed is CRISK, directly influenced by how firm value, size, and leverage are impacted by a climate stress test. (Fed, 2023)

Another prominent example of the implementation of stress testing is the Netherland’s central bank, the DNB, which was among the first central banks to develop a climate stress test. According to the DNB, climate stress testing is done by formulating four severe but plausible scenarios; these four scenarios revolve around two risk factors which are government policy and technological developments. All those changes will impact the Internal Capital Adequacy Process (ICAAP).

Risk Management Reporting: Stakeholders are increasingly interested in seeing sustainability risks in financial reporting, so many companies have voluntarily included sustainability metrics. Sustainability risk frameworks include the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). GRI is the most widely accepted reporting standard of all. Basel has been coordinating with other international bodies and standard setters, including the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), as it drafted Pillar 3 of the Basel framework guidelines. Pillar 3 promotes a common disclosure baseline for climaterelated financial risks across internationally active banks.

Pillar 3 requires qualitative disclosures in four areas by banks: governance, strategy, risk management and concentration risk. Quantitative disclosures include financed emissions, exposure by sector (transition risk), exposure to physical risk per geographic area.

conclusion

It should be noted that banks are value-driven entities and managing climate-related risks can be a complex process, with conflicting motives from banks and regulators. BCBS attempts to influence banks from the stage of drafting the initial strategy, amending their tools and techniques to the final disclosures as detailed in the Basel framework. Although Basel Committee guidelines are essential in driving and aligning the global financial system, climate risk is a dynamic topic and the BCBS must acknowledge this by publishing more guidelines and addressing any gaps in the model. Banks, on the other hand, should ensure adherence to those guidelines not as a tick-the-box exercise but rather to deliver impact.

“The impact of our collective actions today will determine the state of our planet tomorrow.”

- Leonardo DiCaprio

1. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision Climate-related risk drivers and their transmission channels -BCBS. (April 2021). Available at: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d517.pdf

2. Basel Committee on Banking Supervision Frequently asked questions on climate- related financial risks -BCBS. (2022). Available at: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d543.pdf

3. Crowe, M.A.B. (2024). Capturing climate-related financial risks in the Basel Framework - KPMG Global. [online] KPMG. Available at: https://kpmg.com/xx/en/home/insights/2023/02/capturing-climate-related-financial-risks-in-the-baselframework.html

4. Deloitte (2019). Sustainability Risk Management Powering performance for responsible growth. [online] Available at: https:// www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/my/Documents/risk/my-risk-sdg12-sustainability-risk-management.pdf

5. DNB. (November 2019). Good practice integration into climate risk. [online]. Available at: https://www.dnb.nl/media/ a4gdcovq/consultation-document-good-practice-integration-of-climate-related-risk-considerations-into-banks-riskmanagement-nov-2019.pdf.

6. Duyvendijk, S. van (2023). The Future of ESG Risk Management. [online] FloQast. Available at: https://floqast.com/blog/thefuture-of-esg-risk-management/

7. ECB (2024). “Failing to plan is planning to fail’’ – why transition planning is essential for banks. www.bankingsupervision. europa.eu. [online] Available at: https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/press/blog/2024/html/ssm. blog240123~5471c5f63e.en.html

8. FED. (2023). Climate Stress Testing - FEDERAL RESERVE BANK of NEW YORK. [online] Available at: https://www. newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr977.

9. KPMG.ESG risks in banks: Effective strategies to use opportunities and mitigate risks. (n.d.). Available at: https://assets. kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2021/05/esg-risks-in-banks.pdf

10. Lait, J. ESG lending: what banks need to do in 2024. Finastra. https://www.finastra.com/viewpoints/articles/esg-lendingwhat-banks-need-do-2024

11. Mazars (n.d.). Integrating sustainability into risk management - Mazars Group. [online] www.mazars.com. Available at: https://www.mazars.com/Home/Insights/Latest-insights/Integrating-sustainability-into-risk-management.

12. Sustainability Risk Integration Instruction. (n.d.). Available at: https://danskebank.com/-/media/danske-bank-com/filecloud/2022/12/sustainability-risk-integration-instruction.pdf?rev=b42ed0ca17774bfaace5f5c641e9000b

13. spglobal(n.d.). The Increasing Importance of Sustainability Factors in Credit Risk. [online] Available at: https://www.spglobal. com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/blog/the-increasing-importance-of-sustainability-factors-in-credit-risk.

author

Nadia AlQassab is a Senior Lecturer at the Banking and Finance Center at the BIBF, she is a Professional Risk Manager (PRM) and MBA in Business Administration Certified from Strathclyde University. Worked as AVP Market Risk Senior Manager at Gulf International Bank (GIB) and Head of Market and Middle office Desk at Bank of Bahrain and Kuwait (BBK). Chosen in 2009 as an Executive Trainee, with a fast Track career in BBK, reselected in 2020 part of the Ashridge leadership program, which was the first leadership program for senior managers developed in BBK, also selected as part of the first mentorship program initiated by BBK. She is also part of PRMIA Mentorship program worldwide and withholds 15 years of Risk Management experience. Additionally, Nadia also worked as a part time lecturer with Ernst and Young and withholds more than three hundred hours of Training Hours. Nadia is a highly motivated individual with innovative and creative solutions in tackling obstacles. Offering expert knowledge in Risk related issues, and precisely in Market risk solutions and ESG Risk.

Goel peer-reviewed by

Synopsis

In this article the author discusses his approach for and benefits from using machine learning derived trading rules in the delta hedging without options model. The approach uses a Multi-layer Perceptron to fine-tune trading rules applied to the basic Black-Scholes pricing model and Hull’s delta hedging algorithm and is tested on Apple shares, NatGas NYMEX futures and Ethereum tokens to demonstrate the model’s effectiveness across asset classes.

This provides a valuable contribution for practitioners, demonstrating how simple but effective trading rules derived via Python’s AI libraries and subsequently implemented as a spreadsheet macro can compete with expensive and administratively complex options-based trading strategies.

With large technology companies pouring billions of dollars into companies like OpenAI, Cohere, Anthropic and Mistral it has become difficult to ignore AI. Microsoft’s $10bn investment in OpenAI and the billions of dollars raised by San Francisco-based Anthropic from Google and Amazon helped push spending on AI groups to more than double the record $11bn set two years ago. A review of the history of AI suggests that successful applications of machine learning overlap with the application of specific modelling constraints, therefore applying AI to trading rules within the delta hedging methodology framework is likely to be more successful than applying AI to trading rules unconstrained by such a framework.

Delta hedging is a trading strategy that aims to reduce, or hedge, the directional risk associated with price movements in the underlying asset. Practitioners use delta hedging without options when no options are available to hedge the underlying asset or when such options are available but expensive (as the price of these is dependent on implied rather than historic volatility, unlike delta hedging). Therefore, options payoff diagrams for delta hedging without options should resemble Black-Scholes4 options payoff diagrams but with a lower cost of hedging, lower administration costs and lower guaranteed upside capture in mean reverting markets within the period of each option. This article will investigate whether AI tools, constrained within Hull’s5 delta hedging algorithm, can predict market direction sufficiently to increase guaranteed upside capture.

1 / https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~./epxing/Class/10715/reading/McCulloch.and.Pitts.pdf

2 / https://redirect.cs.umbc.edu/courses/471/papers/turing.pdf 3

3 / https://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~pift6266/A06/refs/backprop_old.pdf

4 / Black, F. and M. Scholes “The Valuation of Option Contracts and a Test of Market Efficiency”, Journal of Finance, 27 (May 1972), 399-418

5 / Hull, J. C. “Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives” 3rd edition Prentice Hall 1997 Pages 312-317

- May 2024

With transparency and explainability key considerations as financial market supervisors manage practitioners’ integration of machine learning, in this article the AI modelling has been restricted to predictive classification of 91-day periods where options were replicated using delta hedging. A multilayer perceptron (MLP) model trained on pre-2011 data using Python’s scikit-learn library can then be applied to a post-2011 test-set with regulator-preferred transparency improvements to option-style payoff diagrams and explainable performance enhancements augmenting theoretical R2 hypothesis testing.

A delta hedge trading strategy that replicates the performance of an option by buying and selling the underlying asset in proportion to changes in the option’s hedge ratio can be used as an alternative to expensive and operationally complex derivatives. A spreadsheet model with embedded macros replicating Hull’s Black-Scholes based delta hedging technique with a market momentum, trade reversal suppression measure and fixed 6% floor was enhanced using an MLP model which has the capacity to learn non-linear models as a supervised learning algorithm that learns a function f(·):Rm -> R0 by training on a dataset, where m is the number of dimensions for input and o is the number of dimensions for output. Given a set of features X= x1, x2, ..., xm and a target y, it can learn a non-linear function approximator for either classification or regression. It is different from logistic regression, in that between the input and the output layer, there can be one or more non-linear layers, called hidden layers. MLPClassifier6 from Python’s scikitlearn library was trained using pre-2011 data to predict the classification of either bull (10% hedging floor) or bear (6% hedging floor) periods based on delta model input variables of underlying asset returns and volatility plus interest rates. Research using 10% and 6% hedging floors have been found to be effective in balancing upside capture with hedge effectiveness as shown in the table below and in the author’s previously published articles (in May and August 20237 and February 20248).

Using this model with Apple shares (AAPL),9 91-day AAPL options were simulated from 2011 to 2023. In order to assess the model’s success in replicating options, Figure 1 plots the quarterly return of each of the 48 replicated options for delta hedging using a fixed 6% floor compared to delta hedging using either a 6% or 10% floor depending on whether the AI model predicts a bull or bear market. This plot should be similar to the option’s pay-off diagram taking account of the lower cost of the hedge (using historic rather than implied volatility).

6 / https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.neural_network.MLPClassifier.html#sklearn.neural_network.MLPClassifier

7 / “Cryptocurrency delta hedging” (May 2023) and “Energy Delta Hedging” (August 2023). Find at: https://www.prmia.org/Public/Resources/Intelligent_Risk.aspx

8 / “Hedging technological (crypto) commodities” https://prmia.org/Public/Resources/Intelligent_Risk_February_2024.aspx

9 / https://uk.investing.com/equities/apple-computer-inc

Figure 1: Plot to assess how well AAPL Delta Hedging with fixed and AI derived floor replicate Options

Another assessment of the model’s success in replicating options, by plotting the quarterly return of each of the 48 replicated options against unhedged AAPL share price return, delta hedging using a fixed 6% floor and delta hedging with an AI derived floor as a bar graph, is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Bar diagram to assess how well AAPL Delta Hedging with fixed and AI derived floor replicate Options

Finally, Figure 3 shows comparative cumulative 91-day performance figures for returns of unhedged AAPL shares, delta hedging using a fixed 6% floor, delta hedging with an AI derived floor and 1-month US LIBOR.

Figure 3: APPL vs. Delta Hedging (Fixed and AI derived Floor) Jan '21 - Sep '23

Using Amazon and Tesla share prices produced consistent results to Apple share price and are included in the results table below.

Using this model with NatGas NYMEX Futures10, 91-day NatGas options were simulated from 2011 to 2023. In order to assess the model’s success in replicating options, Figure 4 plots the quarterly return of each of the 49 replicated options for delta hedging using a fixed 6% floor compared to delta hedging using either a 6% or 10% floor depending on whether the AI model predicts a bull or bear market. This plot should be similar to the option’s pay-off diagram taking account of the lower cost of the hedge.

Figure 4: Plot to assess how well NatGas NYMEX Futures Delta Hedging without Options replicate Options

Another assessment of the model’s success in replicating options, plotting the quarterly return of each of the 49 replicated options against unhedged NatGas NYMEX Futures return, delta hedging using a fixed 6% floor and delta hedging with an AI derived floor as a bar graph, is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Bar diagram to assess how well NatGas NYMEX Futures Delta Hedging with fixed and AI derived floor replicate Options

10 / https://uk.investing.com/commodities/natural-gas-historical-data

Finally, Figure 6 shows comparative cumulative 91-day performance figures for returns of unhedged NatGas NYMEX Futures, delta hedging using a fixed 6% floor, delta hedging with an AI derived floor and 1-month US LIBOR.

6: NatGas NYMEX Futures vs Delta Hedging (Fixed and AI derived Floor) Jan '21 - Sep'23

Using Gold and Copper futures produced consistent results to NatGas NYMEX futures and are included in the results table below.

Results

11 /

Figure

Simulated delta hedging trading strategies that take a position in cash and an underlying asset proportional to the hedge ratio of a synthetic option provide a cost-effective alternative to strategies that use options to delta hedge portfolios of equities and commodities. When combined with machine learning derived trading rules, new possibilities for active management of investment risk and return become apparent. This presents an opportunity to apply auto-pilot AI trading rules to research risk simulations in similarly constrained environments while co-pilot trading rules can help traders, treasurers, asset managers or insurers actively manage their hedged exposures. As was the case with VaR, AI trading rules may subsequently migrate from the trading floor into risk management departments.

As delta hedging is based on Black-Scholes, extensions to this model may be included like the volatility smile and fat tails in the underlying asset, but the strategy in turn suffers from known Black-Scholes limitations, such as assuming no arbitrage opportunities and that asset returns follow a lognormal pattern, thus ignoring large price swings that are observed more frequently in the real world.

author

Malcolm Gloyer

Malcolm is a Chartered Member of the Chartered Institute for Securities and Investments. As a Certified Practicing Project Manager (CPPM MAIPM), he has more than 30 years’ experience working on projects in the UK and Australia, specializing in market risk, derivatives and commodities. Malcolm has worked as a consultant at companies including Bank of America Merrill Lynch, London Metal Exchange, Nomura, ABN Amro, EDF Trading, Santander and Lloyds Bank and has been a guest lecturer at several universities. Malcolm has had many articles published in professional investment magazines and has written several eBooks.

peer-reviewed Andrea Calefby

Synopsis

Communication, emotions and behavior can greatly impact the effectiveness of risk managers who, surprisingly, can learn a lot from how they are portrayed in Shakespeare’s writings.

Like many teenagers I had little appreciation for studying Shakespeare in high school. Of course, except for math and science courses, I had little appreciation for most high school subjects. High school was a time to learn how to maximize your weekends, rather than memorize soliloquies. With hindsight however, I wish I had paid more attention to Shakespeare (or that someone had made Shakespeare more interesting for me.) A knowledge of Shakespeare is surprisingly relevant for a career in risk management.

The first thing we learn about risk management from studying Shakespeare is the need to use clear and easy to understand language. As a student, I argued at length that it was useless to have students memorize and struggle to parse Old English. I still think that. However, I now have the benefit of reading Shakespeare in side-by-side translation with the Old English on one page and contemporary English on the facing page. This is a game changer, and one can more clearly understand the plot lines and even the nuances of many of the puns – of which some admittedly still need extra commentary to achieve full effect. Written in a language I can understand, Shakespeare comes to life and the plots have compelling twists and turns. How many risk reports are written in the equivalent of Old English that are a chore and a bore for non-enthusiasts to read? The lesson is to make risk management reports clear and easy to read, with a compelling analysis that the readers will appreciate and perhaps even take the time to study.

what Shakespeare knew about communication what Shakespeare knew about human behavior

While in university, I was talking to an English professor one day, and I was giving him grief over the uselessness of studying Shakespeare. The professor calmly turned to me and stated one of the most valuable lessons I learned in all of my studies.

He stated that the reason to study Shakespeare was because Shakespeare was the master of understanding human emotion. This response gave me pause, and as I have evolved in my career, this realization has become more valuable to me with each passing decade. Understanding how people act, and what drives them, is key to developing effective risk management. While the time was definitely different, the emotions of fear, indecision, hope, greed, hatred, and love that Shakespeare had his characters act out is as relevant today as it was in the 1600s. Risk management is ultimately about people. Shakespeare is an excellent source for remembering this important fact.

Hamlet is a play about decision-making in the face of uncertainty. Is that not risk management in a nutshell? Hamlet is faced with the decision of avenging his father’s murder. The issue is that Hamlet is not sure if his father was indeed murdered, and if he was, who the murderer was. The best information Hamlet has is from a ghost, but even that is imperfect as Hamlet cannot be sure if the ghost is sincere, honest, or even real. Perhaps the ghost is nothing but a figment of Hamlet’s imagination. Hamlet is confused and conflicted about this – as well as many other things, but this again is the life of a manager who needs to deal with uncertainty and risk. We never have perfect information, and we can never be certain a priori that we will make the best decision. Shakespeare teaches us that issues with decision-making under uncertainty are nothing new.

Hamlet’s plan of action is to produce a play (within the play) and observe the reaction of certain audience members to his carefully crafted performance. Observing how others react to specific situations is an underutilized tool for the risk manager. However, it has been demonstrated repeatedly that invoking human design elements into risk management interventions can dramatically increase risk effectiveness. Observing human reactions and designing risk interventions based on those reactions is a key Shakespearean lesson.

Like many Shakespeare plays, there are many lines from Hamlet that have become common expressions in our day-to-day. Perhaps the most well known from Hamlet is “To be, or not to be, that is the question.” We use many similarly common expressions each day – many of us without a moment’s thought that Shakespeare is the origin. In a very interesting book titled “How Shakespeare Changed Everything1,” author and social commentator Stephen Marche makes the case that Shakespeare is much more influential in our modern lives than we realize. From the assassination of President Lincoln to the election of President Obama, Marche gives numerous examples of the unknown influence of Shakespeare. Just like Shakespeare, risk management also has an outsized influence on how organizations survive and thrive, or limp along, or even perish. Risk management influences culture, profitability, survivability, and overall success or failure of every organization. While not always appreciated, risk management has influence.

HamletUltimately, studying Shakespeare provides us with some novel and unconventional ways of thinking about risk. Cognitive diversity can be a useful tool for developing better solutions for risk management, and let’s admit it – Shakespeare is about as cognitively diverse from risk management as you can get. One does not often think of Hamlet when considering risk management. Perhaps one should.

1. Marche, S. (2012). How Shakespeare Changed Everything. Harper Perennial. https://www.amazon.com/Shakespeare-Changed-Everything-Stephen-Marche/dp/0061965545/

author

Steve Lindo peer-reviewed by references

Rick Nason, PhD, CFA, is an Associate Professor of Finance at Dalhousie University where he been awarded numerous awards for teaching excellence. His academic work includes researching corporate risk management and complexity in business. As a former capital markets, as well as corporate learning professional, he remains active in consulting and corporate training, specializing on applications of complexity science and risk management.

He is the author / co-author of seven books and textbooks, including It’s Not Complicated: The Art and Science of Complexity in Business, published by University of Toronto Press, and Rethinking Risk Management, by Business Experts Press.

In response to the growing threat of fraud, the banking sector faces substantial loss impacting their profitability and survival. This article explores the strategies employed to mitigate these and keep banks in a going concern state by building out a framework connected to surrounding risks and informed by various banking scandals.

The purpose of this paper is to explore the pervasive issue of internal fraud within the banking sector and propose strategies to bolster the existing fraud framework in order to combat and mitigate its ramifications. Since its inception, fraud has plagued the banking industry with an escalating frequency of incidents that surpass previous records. Fraud manifests in various forms and continuously evolves alongside technological advancements and the introduction of new financial products. Additionally, it is exacerbated by its accomplices in cybercrime and money laundering. Internal fraud, orchestrated by employees, often reflects a flawed banking culture stemming from neglect, ignorance, or greed, necessitating utmost vigilance to prevent its entrenchment.

Fraud within the banking sector has garnered significant attention in recent times, with scandals surfacing at prominent institutions such as ABLV Bank in Latvia, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, Den Danske Bank (involving money laundering), and National Bank of Punjab (involving fraudulent letters of undertaking). Notable historical instances of banking fraud include Nick Leeson's actions at Barings Bank in 1995 and Jerome Kerviel's involvement at Societe Generale in 2008. Even industry giants like JPMorgan Chase & Co have not been immune, facing substantial losses in incidents like the London Whale scandal in 2012. These incidents have prompted regulatory interventions, including new rules prohibiting publicly insured banks from engaging in speculative trading.

In the context of likelihood and severity, fraud measures as a high-impact, low-probability risk to companies, capable of rapidly tarnishing their reputation and integrity. Many banks fail to allocate adequate resources and structure themselves to address this risk, which proves to be a costly mistake in the current environment. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the landscape of fraud, necessitating heightened awareness and education among employees, particularly in the United States, where the Department of Justice has shifted focus towards prosecuting individual wrongdoers.

Given the gravity of the situation and the potential for severe reputational damage, immediate action is imperative. Establishing and implementing a comprehensive fraud risk management framework guided by the board and executed by senior management is crucial. Active engagement of the board is essential to ensure effective corporate governance. A robust fraud risk management framework encompasses governance, assessment, strategy, and evaluation.

Let's delve into the steps a bank can take to develop and maintain an effective fraud risk management program:

• Create a dedicated governance structure to manage fraud risk: Establishing a culture that promotes ethical behavior and receives support from senior leadership is vital. This involves setting up an anti-fraud entity responsible for overseeing all fraud risk management activities, managing fraud risk assessments, leading training programs, and coordinating anti-fraud initiatives across the bank.

• Design and implement an anti-fraud strategy: Develop a comprehensive strategy to prevent, detect, respond to, monitor, and evaluate fraud. Allocate resources based on the bank’s fraud risk profile and focus on specific control activities to prevent and detect fraud. Respond promptly to new and emerging risks by assigning responsibility for analysis, assessment, and evaluation.

• Conduct risk-based monitoring and evaluate all components of the framework: Collect and analyze data to monitor fraud trends and identify potential control deficiencies. Evaluate the effectiveness of preventive activities, fraud risk assessments, anti-fraud strategy, and fraud controls/response efforts. Implement a risk-based approach considering internal and external factors influencing the control environment.

The emergence of COVID-19 introduced unprecedented challenges to fraud risk management, as pandemics and their effects were not previously identified as drivers for the escalation of fraud. Economic hardships faced by employees (potential bank layoffs) during crises like pandemics can amplify personal financial pressures, potentially rationalizing decisions to engage in fraudulent activities. On the other hand, banks may face increased pressure to manipulate financials or resort to fraudulent practices to meet objectives or navigate supply chain disruptions. Social media’s spotlight on bank failings, such as New York Community Bank case (albeit not attributable directly to fraud), can exacerbate the internal control problems.

In response to these challenges, banks must recalibrate their fraud risk programs and introduce countermeasures tailored to the new environment.

This involves re-evaluating governance structures, improving communication strategies, leveraging whistleblowing hotlines, tailoring messages to different audiences, harnessing big data for fraud detection, and continuously reviewing and renewing fraud assessments to adapt to evolving risks.

All the recalibration in the world cannot resolve and detect fraudulent activity without clear strategic intention. Moreover, in the biggest banking scandals mentioned above, if the embarrassment and shame outweigh the consequences then recalibration is, to quote Shakespeare’s Macbeth:

”“…a

poor player, That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, And then is heard no more. It is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.”

- Macbeth (William Shakespeare)

Examples abound, including The London Whale scandal that took place in a unit of JPMorgan that reported directly to Chairman & CEO Jamie Dimon. In Congressional testimony it came out that Dimon wanted to be responsible for what information was revealed, and information was withheld from the regulators.

In the Den Danske money laundering scandal, critical reports were "toned down" in the minuted discussions of the Executive Board and the dangers of money laundering minimized.

conclusion

Internal fraud represents a significant threat to banks, capable of inflicting severe damage to their reputation and financial stability. A dynamic and adaptable framework is essential to mitigate the risks posed by fraud. Efforts must be made to continuously evaluate and refine these frameworks to ensure they remain effective in the face of evolving threats. Ultimately, the responsibility lies with the bank to remain ever vigilant and proactive in combating fraud to avoid adverse consequences. The intent, however, can only be sustained if the tone at the top is both transparent and capable; otherwise the measures are but a paper tiger.

John Thackeray is a risk and compliance practitioner and writer. His firm, RiskInk, helps businesses control their risks by writing policies and procedures to mitigate them. John is a certified fraud examiner who has written many articles for the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. As a former senior risk executive at Citigroup, Deutsche Bank AG and Société Générale, he has had firsthand engagement with U.S. and European regulators.

peer-reviewed by

Nadia AlQassabSynopsis

Residential mortgages carry two contrasting types of transition risk: lower collateral value of energyinefficient homes and higher loan-to-value/loan-to-income ratios of mortgages whose obligors borrow to invest in energy-efficient home improvements. This article shows how using statistical and machine learning models to predict energy labels can be used to quantify these two credit risks more accurately than existing approaches.

introduction

The real estate sector makes a substantial contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 35% of emissions and 40% of the EU’s energy consumption. Therefore, investments in real estate energy efficiency are essential for facilitating the transition to a more sustainable economy.

Energy efficiency of real estate is typically measured by energy labels which range from A++++ (most efficient) to G (least efficient). Energy labels above C are considered ’green’, while those below are called ‘brown.’ Upgrading a ‘brown’ residential dwelling to achieve a green label requires a considerable investment of both cost and effort. Typically, this process involves improving insulation, installing a heat pump and solar panels, or similar expensive interventions.

Regulations regarding energy labels for real estate are continuously tightening in the EU. For instance, in the Netherlands, it's now prohibited to rent or sell commercial real estate with a brown energy label. A similar regulation for residential real estate is anticipated to be implemented soon, following the example of Germany where such rules are already in place. This legislation significantly impacts real estate prices. Recent research by Fitch revealed that across the EU, properties with superior energy labels fetch higher prices in the market compared to their brown-labeled counterparts. This price disparity ranges from 15% in the Netherlands to over 30% in Germany.

The price differentials observed, along with regulatory pressure that could require sudden retrofitting of brown dwellings (resulting in substantial investments), pose a significant source of transition risk for banks with extensive residential mortgage portfolios. A reduced value of a brown dwelling adversely affects the collateral value of a mortgage. Moreover, additional borrowing required for energy label upgrades leads to higher loan-to-value and loan-to-income ratios, thereby increasing the probability of default for borrowers. Therefore, it is crucial for banks to accurately assess this transition risk.

However, many residential properties lack energy labels. While newer properties receive energy labels upon delivery, older houses require assessment by a qualified inspector, and many homeowners do not perform such an assessment, unless they are planning to sell the house. As a conservative approach, banks typically assign a G label to missing observations, resulting in a significant overestimation of transition risk. A more accurate risk assessment could be achieved if the missing energy labels were imputed in a more realistic.

data collection

Our sample dataset is a subset of a typical Dutch bank’s mortgage portfolio, containing data on over 100,000 residential mortgages. For each mortgage, an extensive array of characteristics is available, including area, exact location, building age, size, type, and more. To develop and test our models, we considered properties for which the energy label was known.

Figure 1 below1 illustrates the typical distribution of energy labels in the Netherlands, showing that label C is the most prevalent, but that a proportion of brown dwellings is still substantial.

Figure 1: : Typical distribution of energy labels in the Netherlands

Figure 22 illustrates the distribution of energy labels per building decade, showing a clear trend in energy label improvement over time. Predominantly, buildings constructed before 1970 exhibit labels lower than F. Properties built during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s typically hold label C. Notably, in recent years, there is an increase in the proportion of A and A+ labeled buildings.

Before applying and testing predictive models, it's important to address the high imbalance in our dataset, characterized by significant differences in the proportions of different energy labels. To mitigate this issue, we augmented our training set using a technique called SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique).

SMOTE generates new data points close to existing ones through multivariate interpolation. This approach helps balance the distribution of energy labels in our dataset, enabling more accurate model training.

Our benchmark models are the multinomial regression and ordinal regression, which is suitable for this problem due to a natural ordering of energy labels. We also apply several machine learning models, such as k-Nearest Neighbors, Random Forest and XG boosting.

The model fit was assessed using well-known criteria such as confusion matrix, accuracy, precision, and recall. We also introduced our own accuracy criterion, inspired by the mean squared error, and augmented by a penalty, intended to “punish” predictions that falsely produce green label while the true label is brown and vice versa:

where N is the number of observations in the test set, TV and PV are true and predicted energy label values respectively (note that we encode them with integers 1 to 11) and the Penalty is equal to 2 for false green/ brown prediction and one otherwise.

We also tested the models in the situation when we reduce the problem to a bivariate classification problem, i.e., we only predict whether a missing label is green or brown. In this case, our benchmark models are the logistic regression and its ordinal version.

Figure 2: : Typical distribution of energy labels in the NetherlandsTables 1 and 2 show accuracy criteria for multinomial and binomial predictions, respectively. It is logical that all accuracy measures are higher for bivariate regression, as there is a reduced likelihood of error. Therefore, it is more appropriate to compare the accuracy numbers within each table rather than across the two tables.

We observe that both regressions have similar performance in both cases, with ordinal regression outperforming in the bivariate scenario. The contrast between statistical and machine learning models is more pronounced for multinomial predictions, where ML models outperform statistical ones. Conversely, the difference is less significant for bivariate classification.

Notably, Random Forest outperforms all other models, while also being computationally efficient. Hence, it appears to be the preferred model for this application.

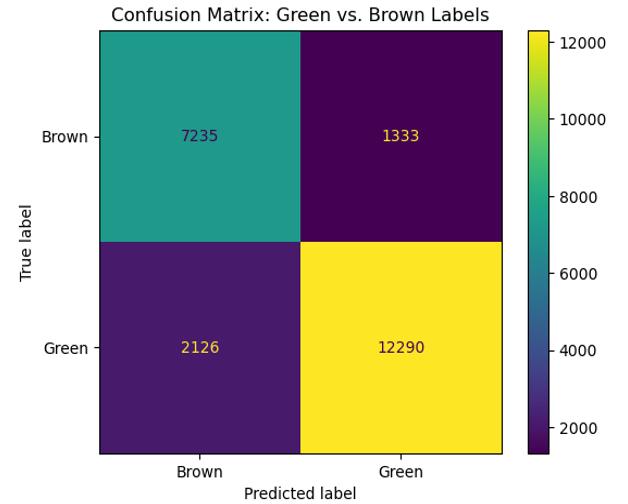

Below we show the confusion matrices for the bivariate prediction: for ordinal regression and Random Forest.

Ordinal regression: Accuracy 0.87

Figure 3: Confusion matrix for the bivariate prediction using ordinal regression Table 1: Accuracy measures for multivariate predictionBelow we show the confusion matrices for the bivariate prediction: for ordinal regression and Random Forest.

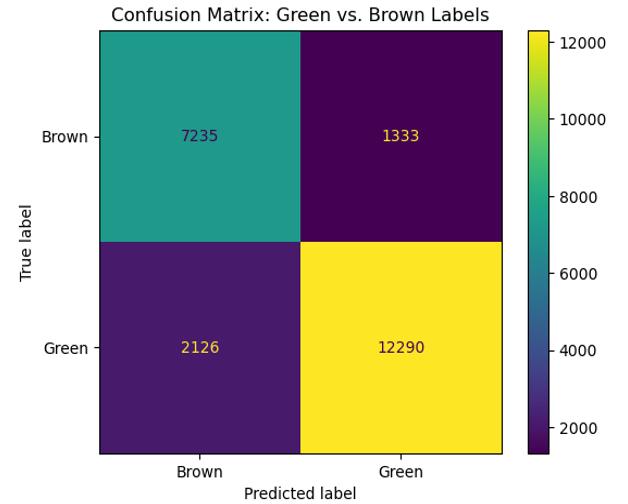

Random Forest: Accuracy 0.88

4: Confusion matrix for the bivariate prediction using Random Forest

The feature importance of the data is shown in the plots below (for Random Forest), for the full model and a reduced model, where we restricted the number of explanatory variables. We see that the main energy label predictor is the building year, followed by the dwelling type (free-standing house, row house or apartment, with apartments generally being more energy efficient) and other variables such as house value and its location.

Figure 5: Main energy label predictors for full model

Figure 6: Main energy label predictors for reduced model

FigureNext, we will examine the monetary implications of our prediction methodology for transition risk calculations. For this, we focus on the part of the mortgage portfolio where energy labels are missing.

Table 33 shows the estimated investment needed to upgrade a ‘brown’ dwelling to a green label, for different types of dwellings.

We used our Random Forest model to impute all missing energy labels and subsequently determine the total cost of upgrading dwellings with brown labels. The total cost of such upgrades amounts to €5,340,000. Conversely, if all unknown energy labels were imputed as label G, the upgrade costs for these dwellings would soar to €19,721,000, nearly four times higher than the costs calculated with our predictions. This contrast in costs can significantly influence the risk assessment of the entire portfolio, leading to a wide variance in default probabilities and estimated collateral values. Moreover, this impact escalates with the size of the portfolio.

conclusion

Our findings reveal that missing energy labels can be accurately predicted, particularly when distinguishing between ‘green’ and ‘brown’ dwellings, rather than precisely predicting the label itself. Both ordinal regression and Random Forest proved to be effective models for this task, exhibiting strong performance across all accuracy measures. Additionally, we identified the determinants of energy labels: the year of construction, dwelling type, location, value, and size. We also demonstrated that estimated upgrade costs can be significantly reduced – up to four times lower – when using predictive models compared to the conservative G-imputation method currently used by banks. This discrepancy in estimated retrofitting costs underscores the substantial impact our approach can have on the transition risk assessment of mortgage portfolios.

references

1. Source: Research data collected for this study

2. Source: Research data collected for this study

3. Francesco Caloia, David-Jan Jansen, Helga Koo, Remco van der Molen and Lu Zhang. Climate transition risk: A financial stability perspective. DNB Research Paper, Occasional Studies, Volume 19 – 4 (2022).

Table 3: Retrofitting investment per dwelling type.authors

Svetlana Borovkova

Duco Plasmeijer, Alexander Bijman, Ruben Korvinus

Dr Svetlana Borovkova is an Associate Professor of Quantitative Finance at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and the Head of Quant Modelling at Probability & Partners: Risk Management Consultancy.

Duco Plasmeijer, Alexander Bijman and Ruben Korvinus are graduates of the Finance & Technology Honors Program of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

peer-reviewed by

Steve Lindo

The author lays out a framework towards better surveillance of credit risks, up to date with considerations around regulation, data and required team skills. This approach recognizes the complexity of the problem and offers clear, practical solutions.

Historically, credit risk managers relied on various methods to monitor their credit portfolios. These included the bank’s transaction data or borrower submissions as part of the initial application and periodic updates. Unfortunately, metrics generated from those data are lagged and are not adequate predictors of borrower health. Even supplemented with external vendor data, they still lacked adequate predictive power and banks faced challenges in calibrating and integrating the data into their monitoring framework.