© Brydon Yao All rights reserved. School of Visual Arts MFA Products of Design

New York, NY May 2024 For Inquiries contact brydon.zhy@gmail.com

This is the view from my bedroom window in my childhood home in Shanghai. Since it faced west, it beautifully framed the sunset every evening. While on most days I would be buried in my computer playing video games or browsing the Internet, some days I would take a break and gaze out of the window for a long time. Looking out at this view, I was able to slow down my thoughts during a particularly rough patch in my teenage life. It was right before I went of to college at NYU, and it was starting to hit me that I would be moving to another country, living in a totally new environment, and saying goodbye to my family. Naturally, the stress began to eat away at me and I spent a good deal of time sitting in front of the window to try to find some reprieve from the overthinking.

One day as I sat catastrophizing, my brother entered my room, but I paid him no mind with so many nerve-racking things running through my head. After he cleared his throat to get my attention, I reflexively turned around to acknowledge him, but all I could see was a roll of paper towels speeding toward my head. With no time to react, I just sat there as he whacked me on the forehead with the roll of paper towels. It didn’t hurt, but I was fuming none-

-theless. “What just happened?” I thought. “He came in to disturb me… for this?” I leapt out of my chair and chased him down the stairs, past the kitchen, and into the living room, where we tussled over the roll of paper towels. I nabbed it from him and struck his head many times before he regained possession of the roll. After the paper towels switched hands many times, we were both tired and called a truce. It is a weird sensation, going from sitting in an anxious cloud of my own thoughts to feeling so pumped up in a play-fighting match within minutes. After everything was through, I was left with a mangled roll of paper towels… and the unexpected feeling that everything was going to be okay. I didn’t know it at the time, but what I had just participated in was a spontaneous session of rough-and-tumble play (RTP). The unspoken preference I have always had for this time of play would eventually lead me to the niche practice of grappling sports, an activity I now partake in enthusiastically.

Events like this one were what I thought back to when I worked on this project. I recalled all the emotions and sensations I had experienced in moments of play like these and wondered whether other people experienced them in a similar way. For

me it almost seemed like horsing around was the key to my happiness. Is there any merit to this perception?

In Chapter 2, I broadly address these questions in the context of the thesis project as a whole, and then in Chapter 3 I explore the questions in more depth and include relevant research findings to back up my observations. The chapters follow the progression of my research journey chronologically, features interviews with subject matter experts, such as coaches, psychologists, sociologists, and teachers followed by a review of the scientific literature I consulted and then. This chapter will provide insight into and evidence of the myriad benefits of RTP and describe why everyone should be partaking in it.

In Chapter 4, I introduce even more research, this time surrounding the users I identified in early phases of exploration. Then, in chapter 5, I take a look at three early prototyping and design projects that helped to motivate and inform my process and that would ultimately shape the course of the thesis as a whole. In Chapter 6, I go on to document the major design projects that resulted from the research and experimentation, covering a range of physical designs, digital platforms, and services.

Thinking back to the play-fighting incident with my brother, I realize that hitting a rough patch as one enters emerging adulthood is not a rare occurrence at all. In fact, it is a very common phase that people go through. Emerging adulthood refers to the age group between 18 and 25, proposed by Jeffrey Arnett as an addition to Erikson’s model of the stages of psychosocial development. According the psychologist Jeffrey Arnett, this stage of development is defined by and role confusion, which make developments that take placed during this stage especially tumultuous. According to new literature, a landmark occurrence among this age group is making the transition to college life, which commonly fosters an uptick in personal stress. This is especially notable considering that people in this age group are in a developmental state where they are much more sensitive to stress, which can lea to a myriad go compilations for an individual’s mental health (Worsely, Harrison, and Corcoran. 2021)(Brito and Soares, 2023).

What happens during emerging adulthood is exactly what the phrase would suggest. Adolescents are expected to transition into fully grown adults in a matter of a few years. For most, making the

transition involves foregoing any behaviors that are considered unbecoming of an adult, especially the different types of play (Van Vleet & Feeney, 2015).

As one grows up, unstructured RTP outside of sports contexts comes to be seen as especially inappropriate and frivolous in most adult situations. Despite this perception, studies have shown that adult participation in activities, such as RTP brings many benefits both physically and mentally. Mainstays of physical play during childhood such as rough-housing are great for stress mediation and resilience development, yet they are strongly discouraged as we grow up and face more stress and adversity.

“Horsing Around: Reconnecting Emerging Adults with Rough-and-Tumble Play” situates itself in the tension between growing up and acceptable forms of play. It interrogates the notion of juvenile physical play through a series of designs that set out to re-engage emerging adults with a myriad of frivolous play modalities.

2.5

Advaned Capitalism

A situation in which a society has deeply integrated the capitalist model for a long period of time.

(Butler, 2021)

Bad Retail Retail opitions that cater to vices, or exploit the vulnerable. Examples include liquor stores, smoke shops, and etc. (Kolb, 2022)

Consumption

The use of goods and services by households and individuals. (Kolb, 2022)

Extrinsic Values

Values that are centered on external approval or rewards. (Butler, 2021)

Intrinsic Values

Values that are inherently rewarding such as creativity and connection to others. (Zimmerman, 2019)

Identity A tangible sense of self continuity defined by unique physical and psychological features as well as a host of affiliations and social roles. (Verplanken & Sui, 2019.

Market Driven Identity (MDI)

Personal Growth Initiative (PGI)

Personal identities that are prominently regulated by identity-enhancing market driven criteria that emphasizes one’s status. (Butler, 2021)

An individual’s internal motivation to grow as an indiviual in ways that are important to them. (Cai & Lian, 2022)

Play

Psychosocial Development

Resilience

An activity done enthusiastially with the goal of recreation and fun.

(Van Vleet & Feeney, 2015)

Psychological/cognitive developments and changesin an individual that not only manifest in overt behavior but also in social cogntion.

(Orenstein & Lewis, 2022)

A personal adaptive attribute that helps individuals overcome stresses and adversities. It is also a protective factor against mental illnesses.

(Flemming & Ledogar, 2008)

Rough and Tumble Play (RTP)

Self Efficacy

Novel Play

A type of consensual play fighting between parties that is physical and aggressive yet also lighthearted and playful.

(Blomqvist & Stylin, 2021)

A personal belief in one’s capability ot organize and execute courses of action requried to attain desired performances. (Artino, 2012)

New forms and dimensions of play that were previously unexplored by the individual.

(Feeney, Personal Communication, 2023)

My research journey for this thesis has been highly exploratory. Initially motivated by a rough interest food systems, the subject of inequality of said system, eventually emerged as my focus. Although the final thesis is quite a departure from this initial focus. The research I conducted during the early phases is inseparable from the work I would later produce. In this chapter, I will review the entire research process that, through all of its twists and turns, has contributed to the context of the final thesis.

In the early stages of my research, I attempted to look at the ways in which inequality can be perceived as a physical phenomenon. In other words, how does inequality manifest in the bodies of people? My first instinct was to investigate the physical health outcomes experienced by members of underserved communities. The topic of food deserts would become a launching point for my later research.

Food deserts are defined by the U.S. government as experienced by “communities with poverty rate of 20 percent or greater, a median family income below 80 percent of the surrounding area, and at least 500 residents living more than a mile from a large grocery store” (Kolb, 2022). In response

to the issue of food deserts, scholars have posited that what needs to happen to improve the health outcomes of underserved communities is for grocery stores to be opened in close physical proximity to the affected communities, which presents a straightforward and simple solution to a stubborn problem. It was not long until food deserts became the de facto framework by which to understand urban health disparities. However, later research would show that the initial understandings of food deserts were completely erroneous.

According to later research, there was no substantial evidence that demonstrates that improved access to fresh foods, as well as less exposure to conveniently located fast food restaurants improve the diet or health outcomes of underserved communities (Kolb, 2022). Furthermore, the supermarkets that have been opened in designated food deserts are often not utilized by the local community, suggesting that the presence of a service or retail destination does not change people’s spending habits. Rather, there is a much more complex set of factors responsible for an individuals’ choice of where to participate in retail whether that be food or other items.

In conversations, Professor Ken Kolb, the author of Retail Inequalities, Reframing the Food Desert Debate, reviewed these factors. Rather than proximity to retail food outlets, factors like family dynamics, work dynamics, and income tend to have a more significant effect on how much time and money people spend on food. Fast food is a convenient option for people living busy lives, as they tend to purchase this type of food because it is an easy solution to access a meal. Having grocery stores available nearby their homes would not change that. One of Professor Kolb’s suggestions that really stuck with me is the idea that food inequality is not just about food; it is about retail access in general. This ranges from access to businesses like specialty goods stores to access to recreation athletics centers. In order to further explore this phenomenon, I began conducting interviews with individuals who grew up in government designated food deserts.

Among these interviews, I had the opportunity to interview a very accomplished judo athlete named Garry St. Leger. St. Leger received a black belt in judo and jiu jitsu and has years of experience competing at the national and olympic levels. He now owns and operates a gym in the Chelsea

“You can have a genuine interest in Jiu Jitsu, and a gym can open right beneath your apartment, but that doesn’t mean you’ll join.”

[Dr. Ken Kolb, Personal Communication, 2023]

“Martial arts helped me learn about who I am”

[Garry St. Leger, Personal Communication, 2023]

neighborhood of New York City. East New York, Brookyln, the area where Garry grew up and a long time retail desert, has historically been tumultuous. There was no easy access to recreational activities, however, Garry attended a primary school with a robust after school judo club where he was surrounded by a nurturing community of students who trained and competed together.

The club was inexpensive and held its judo practices across the street from his school. Garry would go there to train with his brother and friends immediately after school let out. For his parents, who both worked full time, the time Garry and his brother spent at the club accounted for a large portion of the day during which they were under adults supervision. While the proximity of the club to his school was a significant factor in his ability to join the club, it was the dynamics of Garry’s gamily that made his participation truly possible. During our interview, Garry talked extensively about his martial arts journey. Being a martial arts fanatic myself, I absolutely loved hearing about the positive impact that judo training had on his life. As we spoke, I pondered the uniqueness of the martial arts club Garry attended during his childhood and how many students miss

out on the benefits of such training.

In order to further observe how after school martial arts programs affect and benefit emerging adults and their psychological makeup, I visited the Brooklyn Polytechnic High School of Engineering, Architecture, and Technology, or “City Poly,” in Downtown Brooklyn, where a personal friend of mine, Erik Nicholson, serves as the dean of students. Erik is also a very capable Brazilian jiu jitsu brown belt as well as the head coach and organizer of the after school jiu jitsu club there.

I met Erik years ago at an early morning judo practice that we both attended. When I talked to him, I found out that he ran an after school Brazilian jiu jitsu program for the students at his high school. Erik was gracious enough to allow to to conduct a workshop with them so that I could learn about the students’ lives and the role that this Brazilian jiu jitsu program has played.

For the workshop, I put together packets with two components: the first component asked the students to draw a self portrait based on how they perceived themselves as martial artists. I encouraged labeling for this phase. The second component was a questionnaire that asked the students about their

martial arts practice. The findings were particularly interesting.

When responding to questions asking what they would be doing after school if the program did not exist, many students had said that they would be doing nothing. The program served as a major source of socialization for almost all the students surveyed, all of whom reported positive outcomes from the participation in jiu jitsu. Notably, a lot of the more senior students expressed their anxiety regarding college applications and the worries they have regarding potentially losing access to the club. The workshop made clear the importance of the program and the activities it enables. It also also helped to highlight the effect that access to a RTP heavy activity had on these students.

RTP is a type of rough physical play that is undertaken by consenting parties that has been demonstrated to help mediate better developmental outcomes in children and adolescents. It demands high levels of self-regulation during periods of play so that the practice does not escalate into real fighting. The requirement of self-control the activity places upon participants helps stimulate psychosocial growth (Blomqvist & Stylin, 2021).

Research on adolescent populations who participate in this form of play also shows the immense developmental benefits of participating in martial arts programs, especially in the after school context (Moore et al., 2021).

Research also indicates the essential developmental role that embodied physical play has in early childhood. The benefits includes things such as increased cognitive development, culturaltion, emotional development, social development, and more (Barnett, 1990). However, there is scant literature that studies the effect of any type of play beyond childhood (Van Vleet & Feeney, 2015). To investigate this further, I spoke with Brook Feeney, a professor of psychology at Carnegie Mellon University who has conducted a literature review of extant research articles studying adult play.

In our conversation, Dr. Feeney and I discussed the positive impacts of physical embodied play and RTP. We talked about how physical modes of play are uniquely impactful because they combine the positive outcomes of exercise with the beneficial routine of play. The amalgam of positive outcomes is considerable, from improvements in physical health (Moghaddaszadeh & Belcastro, 2021) and resilience;

“The benefits of play do not stop at childhood!”

[Dr.

Brooke F. Feeney, Personal Communication, 2024]

“ We don’t stop playing because we grow old, we grow old because we stop playing”

[George Bernard Shaw]

to the growth of self-efficacy (Arida & Machado, 2020); to the rapid imparting of positive emotional affect, and stress reduction (Lancaster & Callaghan, 2022).

When I asked Dr. Feeney why she thinks there is a drought of literature about adult play, she spoke about the expectations placed on adults, whose society require to be productive in most contexts. According to Van Vleet and Feeney (2015), “if play is not viewed as a productive means to spend one’s time, then play among adults may be perceived as frivolous, over-indulgent, or irresponsible.” However Dr. Feeney stressed that despite all this, the benefits of play do not stop at childhood. Somewhere during the transition from childhood to adulthood, play becomes discouraged and unacceptable behavior for adutls. This is especially curious and problematic. Considering the physical and mental health benefits that play can impart, why is it discouraged as people grow up and deal with greater level of adversity? Why is such a powerful tool as play left behind?

According to Jeffrey Arnett, emerging adulthood is a developmental stage situated between adolescence and early adulthood on Erikson’s model of psychosocial development. It is a transitory period marked my physical changes that result from the conclusion of puberty, the transition also involved numerous mental changed and societal expectations. One of the biggest changes for emerging adults occurs at the onset of this period. This change is called going to college.

Starting college is a pivotal transition for young adults. For many, it marks the end of the normal and stable routines they have previously accustomed to and the beginning of a very uncertain, stressful stage in their transition to adulthood. For most students, it is the first time that they are away from their existing familial and social support networks. They are face with the pressure of attempting to rebuild their social networks from the ground up while simultaneously facing the challenges of their academic life. The pressure many students face is amplified by the fact that their academic performance during college can have a significant impact on their future success and livelihood. These pressures combine and leave their imprint on new stu

-dents almost immediately.

According to Worsely, Harrison, and Corcoran (2021), there is a near immediate and measurable increase in psychological distress for students upon entering college. The study elaborates that complex life transitions in conjunction with new responsibilities account for the top stressors for new students. In other words, the combined stresses of having a higher academic workload and moving away from one’s entrenched social circle can culminate in high levels of mental pressure for college freshmen. This is especially significant as emerging adults are especially vulnerable to adverse mental health developments. This is because “emerging adulthood sees accelerated brain growth, heightened stress sensitivity, and uncertainty which make individuals more susceptible to the development of mental health disorders (Brito and Soares, 2023). In fact, according to Lipson et al. (2021), nearly “half of all lifetime mental health disorders have their first onset by mid-adolescence and nearly three quarters by the mid-twenties.” In other words, 75 percent of life-long mental illnesses develop before the conclusion of emerging adulthood. These facts can be seen reflected in the ongoing mental health crisis within colleges.

A review conducted by the Mental Health Association of New York State gathered data from the survey responses of 155,026 students across 196 colleges in the United States from 2007 through 2017. It found a significant increase in adverse mental health incidents in the college population throughout these 10 years. According to the report, the percentage of students diagnosed with mental health conditions increased from 21.9% to 35.5% in the given time period. The report also states that the rates of depression increased from 24.8% to 29.0%. And, most alarmingly, rates of suicidal ideation nearly doubled, going up from 5.8% to 10.8% (Richter, 2022). Although colleges have been attempting to keep up with the large explosion in the demand for mental health services, they often find they are not able to.

Many factors may contribute to the uptick in the prevalence of mental health disorders in the surveyed population in recent years. One factor is the cultural shift towards emphasizing extrinsic over intrinsic values that has taken place in advanced capitalist societies over the last few decades (Butler, 2021). According to Butler (2021) Extrinsic values, including an emphasis on physical appearance, wealth,

and success, have become the predominant factors in our self-perception and identity formation in recent years, producing major adverse developmental outcomes.

Another suggested factor is the continuous destigmatization of mental health issues that has been occurring. According to the survey answers, the review found that there is an inverse relationship between levels of stigmatization of mental health issues and help-seeking behavior (Richter, 2022). While one can argue the decreased stigmatization and increased help-seeking behaviors are creating the mere appearance of a spiraling mental health crisis, the prevalence of mental health disorders in college students is still quite concerning.

One proposed way to create better outcomes for college students is to affirm and build resilience in adolescents and emerging adults. Resilience is defined as one’s adaptability in the face of stress and adversity. It is generally accepted by psychologists to be a protective factor against the development of mental disorders or risk factors such as suicidal ideation (Shrivastava & Desousa, 2016). Studies have demonstrated that play has a strong effect on the brain’s architecture, particularly when it comes to the

development of resilience (Ho, 2022). However, the importance of the consistent strengthening effects of play have been neglected over time.

With all this in mind, the expectation that adults should play less as they get older presents a stark issue, in that, as studies have shown, not only is play a powerful developmental tool for children; it also has strong benefits for adults. Notably, play is a powerful resilience-building and stress management tool. Unfortunately, as one gets older and encounters a greater level of adversity, he or she, is often discouraged from using the tool of play. The result is a great gap in the mental health tool kit of emerging adults and adults, a significant factor in them being inadequately equipped to handle the added stresses that life presents and therefore worse mental health outcomes.

During the initial phases of research, while still pondering the topic of food deserts, I drew upon my background as a game designer to try and investigate the issue from a myriad of angles. With the research on hand, I began to develop a board game called Roots and Rocks to educate users about the general biochemistry that powers plant cultivation. Drawing upon different genres of games, Roots and Rocks simulates the battle between the forces of nature and human input. The game is designed to be fun, engaging, and informative in showing that all micronutrients can be both beneficial and harmful to the growth of plants. So how does the game work?

The materials are a satchel of approximately 2cm x 2cm black squares, a satchel of 4cm x 1cm white rectangles an approximately 45cm x 45cm playing board, and a deck of 104 playing cards.

Let’s take a closer look. The center of the playing board there is a large square with four circles inside of it. Each of the circles represents a living seed. The white rectangles, called “roots,” represent plant matter, while the black squares, called “rocks,” represent rocks, pests, and other obstructions to plant growth.

The game involves two to four players being placed onto two teams, with one team trying to help the seeds grow, while the other team tries too stunt the seeds’ growth and kill it. The first team’s goal is to grow its plants outwards from the center to beyond the edge of the board, while the goal of the second team is to prevent the plants from reaching the edge. The first team wins the game if it can get its roots to form a continuous path from the seed to the edge of the board, whereas the second team wins by using its available rock pieces to prevent the first team from reaching the edge (this victory condition is triggered when the first team depletes all their root pieces). The second team can also win by killing all four of the first team’s seeds, which is achieved by erasing all of the root pieces connected to a central seed and placing a rock piece atop it.

The teams are determined by the most convenient means available, whether it be rock paper scissors or a coin toss. Following team formation, the playing board is put on a large table-top, ensuring that all players can clearly see and reach the board. Then, the provided deck of cards is shuffled and placed face down next to the board. Five cards are then dealt to each player from the top of the deck.

The second team then puts eight rocks wherever they choose on the board, after which the first team “germinates” the seeds by laying four root pieces anywhere along the outer edge of all four central seeds.

At each turn, a player may place on of his or her team’s pieces or play an effect card. All cards carry two effects: the effect that gets activated when the card is played depends on the team playing it.

A turn ends when a player either discards a card or draws a new card from the deck. Players may only have five cards in their hand at the end of a turn. The game ends when either of the teams meets one of the victory conditions.

To see whether or not the prototype functions as intended, I play tested the game for a few rounds with friends. As with all games, and educational games in particular, the challenge lies in how well the thematic elements and game mechanics deliver the intended learning outcomes. How well games are able to impart the desired educational outcomes depends largely on how the act of playing is designed. One key takeaway from the play testing I conducted for this particular rendition of the game is that what were meant to serve as educational components ended up being merely decorative features. While astute players who are aware of the facts and information involved in the cards may receive the desired learning outcomes, it is also entirely possible to play the game without noticing the educational components at all. In a sense, the concept of plant micronutrients introduced in this game serves as a thematic and aesthetic foundation, rather than an indispensable part of the core mechanic as intended. Part of me thinks that this prototype strikes close to the appropriate balance between game and educational material, while another part of me wishes the educational component can be made even more obvious.

I conceived of the co-creation workshop as a step in the research process rather than a direct exploration of the design. The workshop came at a time when the research was still not quite formed and therefore would require some elaboration. When Erik Nicholson, the dean of students at City Poly, agreed to have me hold a workshop with his jiu jitsu students, I knew it was an amazing opportunity to conduct research with my main target audience of emerging adults and late adolescents. It was the perfect chance to continue my research via co-creation. Let’s take a look at how that went.

My desired research outcomes for the co-creation workshop was to gain a direct insight on how the martial arts have affected the lives of the students in terms of self-perception, identity, confidence, and community. The workshop was thus intended to facilitate students’ self-expression. As previously mentioned, the co-creation workshop had two main components. For the self-portrait component, I gave students a printed outline of a kneeling martial artist, and provided them with markers, pens, and pencils and asked them to imagine and draw their “inner martial artist,” which I suggested they consider their alter ego. Many of the students took a lot of time to draw themselves and contemplate the task. They had a wide array of perceptions of their martial artists, often donning bright colors and outfits similar to comic book superheroes.

For the second component, I provided students a questionnaire asking them to reflect on their martial arts practice and what they think their lives would be like without access to this after school program. The students were careful to answer each question and also provide me with feedback regarding the clarity of the questions. Whereas the self-portrait served as a type of warm-up to get the stu-

-dents thinking about martial arts and themselves, offering insight into their self-perception, identity, confidence, and sense of community, the questionnaire served as the primary research instrument, providing direct data from the students.

The findings of the workshop were unexpected. The majority of students reported that they would not be in any extracurricular activities if they did not participate in this club. They also said that the club served as a major source of after school socialization for them. They additionally suggested that on of the main benefits of the Brazilian jiu jitsu club is that it offers the benefits of athletics without the stresses and pressures of being on a high school sports team, a reference to the high barriers to entry that comes with team sports in high school. Many of the senior students spoke about their college applications and how they didn’t want to leave the club behind.

As mentioned in previous chapters, the benefits of playing are well defined by scientific literature, especially play as a developmental tool. The benefits include a range of factors, including improved self-efficacy, greater self-regulation, mood regulation, cognitive development, psychosocial development, stress mediation, bonding, resilience building, and many more. While these benefits are all very important in childhood, they certainly do not end in childhood. Play continuously imparts these and other benefits on participants well into adulthood. With this in mind, I went into the design phase of this thesis with the goal of remedying the great diminishing of play. To begin, I hosted an even called Fence.

Held on March 31, 2024, Fence is a gladiatorial play-fighting event that I organized with the goal of providing a safe environment and framework in which emerging adults can reconnect with RTP and realize its therapeutic benefits. Participants use foam implements to duel it out in one-on-one matches across an hour of non-stop tournament style play. Fence encourages the duelists to shed their “grown up” inhibitions and just to get playing. We took individuals who have not experienced play fighting in some time and thrust them into the event.

The choice was made to deliberately use props and toys designed for children to establish a tactile connection with an object of light-hearted aggression. For many, play-fighting with foam swords brings to mind early memories of similar play fighting done for fun as a child, which is why I chose foam swords as the main instrument of the game. I also carefully considered and curated the thematic elements and game mechanics to add layers of live action role play that would better situate players in the activity, essentially immersing them in a silly environment that would make them feel more liberated to cut loose and play. With the event, I sought to

provide a safe environment and framework where emerging adults could reconnect with RTP and become aware of its emotional and psychological benefits beyond childhood.

Part of the purpose of holding this event was to put the research I gathered on RTP into practice. During the event, I conducted interviews to make participants more cognizant of the changes in their emotion state that occur as they play. The interviews were formulated to observe the outward behavioral changes and emotional effects that take place over the course of the event.

We began the event with an introduction for all participants. The introduction began with an overview of the rules of engagement during the event as well as a brief Q&A session. Because all of the assembled participants had received an invitation booklet with the rules of engagement, this segment was quite fast. This was followed by participant interviews focusing on their current emotional state and recent RTP experiences (if any).

Following the introduction, the event enters the tournament stage in the form of King of the Hill rotations. Originally, we intended to have tournament brackets; however, there were not enough

participants to form a full competition bracket, so we opted for a King of the Hill tournament format. In this format, two people compete in a single fencing match, and according the the outcome, the winner remains in the designated fighting space and the loser exists. Any participant in the arena is then allowed to jump into the space and fight the previous winner; thereby forming the second match. This process continues until the allotted time is up. The tournament winner is the individual who wins the most cumulative rounds. The more you jump into the arena, the more likely it is for you to win.

After the fighting ends, the event winds down with a debriefing session and then a follow-up interview in which the participants are asked to reflect on the changes in their emotional state throughout the event. Participants emphasized that they felt an improvement in their mood, attributing it to the “unserious exercise.”

Although the event was a success, many friends and acquaintances whom I invited to Fence refused the invitation on the grounds that they would “feel weird” partaking in this type of activity. Then, during the event, when we attempted to stop strangers in the park and have them join us in our

activities, they seemed very uncomfortable with the idea. The apprehension that people were expressing was starting to annoy me.

I began this second project pondering “is it possible to persuade your friends friends and peers into a moment of RTP through the use of an ambush?” This is what eventually led me to create “Bom-Poms”. Bom-Poms are specialized gloves that are oversized and padded, designed to help you instigate unexpected bouts of RTP with your peers. At rest, Bom-Poms can be disguised as a regular pillow. They are a static item of leisure that you can use as you would a regular pillow. You can also bring them anywhere without fear that their true purpose will be detected. When put into action, Bom-Poms become fighting gloves that you can rapidly deploy to ambush you friends, peers, and coworkers, to take part in some good old rough housing.

The gloves went through many stages of design and required a lot of testing of materials to find a combination that was light enough to swing around, soft enough not to hurt somebody when hit, and comfortable enough to double as a pillow. I had to partake in many rounds of testing the product’s viability as both a pillow and a striking implement. My peers have struck me with every single iteration of the Bom-Poms to test their softness. Naps were also taken on the many versions of Bom-Poms. Eventually, the product would come to be made with a high-density polyurethane foam core and padded with you stuffing wrapped in felt.

Bom-Poms feature a specialized crevice for users to insert their hands. The crevice was carved in a special shape to assist in solid gripping of the Bom-Pom during bouts of RTP. This way, it ensures that the Bom-Pom stays well affixed to the user’s arm even in the most wild of play sessions.

The process for creating the Bom-Poms were especially grueling. I have never sewn before so it was very tricky to attempt to join all the different materials and components of Bom-Poms into one mass. Eventually I had to learn how to sew and work with soft forms.

While it can be a lot of fun, the type of spontaneity involved crosses a line that some individuals aren’t comfortable with. In addition, all the activities I conducted have required varying levels of physical contact, which it occurred to me not everyone who is interesting in participating is prepared to be involved in. This led me to consider whether it would be possible to extract and replicate the aggressive competitive goal orientation and embodied physicality of RTP while not making it necessary for people to make physical contact with others. To explore this consideration, I envisioned a video game called “Turf-Takers”.

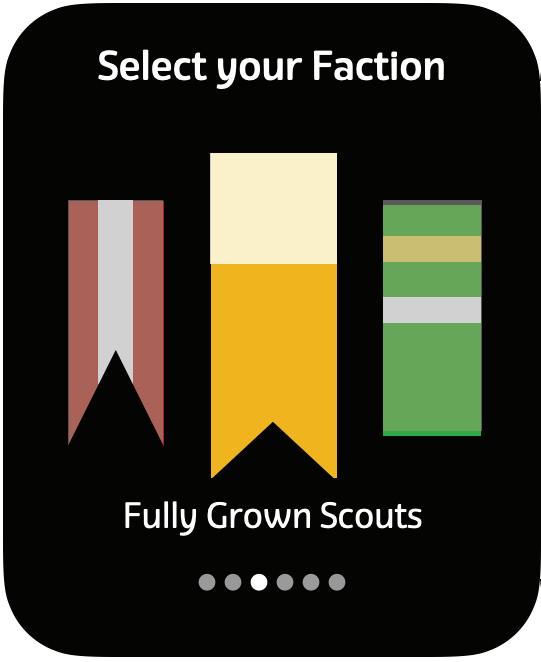

Turf Takers is a smart watch based augmented reality massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPGs). Its focus would be on combat between open-world players and player factions. Building off of the ideas of the titans in augmented reality and role-playing games like Pokémon GO and World of Warcraft, Turf Takers envisions a new type of player-versus-player MMORPG.

Turf Takers would involve a game world that correlates to the real world, meaning that the game map would match the existing physical world around you. Within the digital world, the male would be partitioned into sectors in which players can dwell. Using their smart watches, players could see where they are located in the game world and interact with its creatures and objectives while roaming the physical world.

The core mechanic of the game revolves around capturing digital sectors for your character’s chosen faction, which would grant that faction’s players with prestige and in-game rewards.

Upon entering the game, players are prompted to create a customizable digital character. Once they’ve done this, they can choose an in-game faction and be troubled with other players who have chosen the same faction.

When players press “Go!” The game runs passively in the background as they go about their day. The game uses the smart watch’s sensors to understand where the player is in the game world and pushes a notification when the player enters a contested or enemy held zone.

An example of a scenario that might take place in the game is a player named Bryan going out for a walk before running errands and noticing that he is near an unclaimed sector. Using the game map, he can navigate the contested sector and the game will notify him that he has entered a “capture point”. A capture point is a specific area within a digital sector where players can attempt to claim the sector.

The game will then prompt him with the actions he must perform to capture the territory. The designated actions might be high knees and chicken noises, which the smart watch’s microphone and myriad biometric sensors would be able to detect whether Bryan is actually completing. If he is the progression bar on his screen will advance.

An enemy player from a different faction can also come into the game and challenge Bryan at his contested point. That player must also perform the designated action of high knees and chicken noises. Once an enemy player does the movement, the main player’s progress stalls and the two players are locked in a battle of physicality. In this case, Bryan wins due to his better stamina and completes the capture of this point.

Upon victory, Bryan would receive a loot box of rewards, including cosmetic items and power ups for his in-game character. His victory would also leave an imprint on the came map, capturing this digital sector for all players to see.

This section will document two earlier projects that built off of the learnings and experiences gained from the co-creation workshop held at Erik’s school. These projects focused on providing avenues of access to RTP in the form of martial arts in order to reinforce play habits during a transitory developmental stage that sees the profound diminishing of play in an individual’s everyday life.

Martial arts such as jiu jitsu and judo have highly designed and structured training regimens. The structure provides a serious and productive learning environment that still offers a tremendous avenue for play. Erik’s club featured in previous chapters demonstrate the effects of bringing RTP to high school kids. Inspired by his efforts I went about thinking about ways similar benefits can be brought to students of other schools.

The amount of time and knowledge that Erik possessed does not come across frequently. His particularly education and unique institutional knowledge of both public schools and jiu jitsu academies have provided him the foundation necessary to effectively run a jiu jitsu club for high school kids. Similar attempts to open clubs at other institutions than City Poly would likely require much more time and effort due to the responsibility for building such a club not being assigned to one individual. Therefore I pondered if it was possible for students of other school to take advantage of Erik’s club. This led me to envision ClubHub.

I conceived ClubHub as a networking app that would serve as a platform for public high schoolers to be able to explore different after-school

activities than those that existed at their own high school. The club would provide high school students a venue at which to meet and interact with other students interested in exploring similar interests thereby giving students access to activities and communities that many would otherwise be shut out from.

ClubHub began as a play on GrubHub, the food delivery app, which served as a foundation in user interface. This was due to GrubHub’s existing navigational tools that allow users to explore nearby restaurants. ClubHub twists this base interface to allow students to explore nearby after-school clubs.

As the development of the app proceeded, it became apparent that it would not be simple. A formidable challenge was the school system itself. With the security demands and different scheduling across the high schools, convincing school administrators to incorporate this new system and accommodate students not attending their own school would be very challenging. With this in mind, I proceeded with the project cautiously as an explorative design more than anything else.

The project received a lot of validation with the first round of user testing. The students suggest-

-ed that an app like this would be interesting and even said thatthey would be likely to use it. However the students that responded in this round of user testing were in a peculiar situation. They were located in an area where three schools were down the block from each other. When I asked the students about traveling longer distances to schools that are farther away, their enthusiasm for joining other clubs dropped precipitously. This raises the significant consideration that there needs to be many interesting clubs dispersed throughout the city in close proximity to a variety of students in order for this idea to work.

I wondered if there was a way to get around the previously described limitations of ClubHub. I reframed the project and asked the question, what if instead of bringing students to interesting clubs, we bring the clubs to students? Returning to Erik’s special body of expertise, I wondered if it was possible to somehow replicate his club and run it at different schools. I embarked on a different direction this time and from the outset of this project, I focused on how a service can be designed to bring together the required institutional and technical knowledge to create customized and specialized programs that can help fully realize the benefits of RTP for emerging adults.

The result was After School Warriors. After School Warriors is a service that aims to bring psychologists, coaches, and school administrators together to create custom martial arts-based physical education programs for individual educational high schools, and thereby help late adolescents and emerging adults engage in more play. The purpose in exploring interventions for high schoolers is to reinforce RTP during a pivotal transitory period in their lives where the amount of play tends to decline.

Arida R M., Teixeira-Machado L. (2020). The Contribution of Physical Exercise to Brain Re silience. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/33584215/

Arnett, J. (2017). Adolescence and Emerging Adult hood: A Cultural Approach (6th Edition). Pear son.

Artino, A. R. (2012). Academic Self-Efficacy: From Ed ucational Theory to Instructional Practice. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC3540350/

Barnett, Lynn A. (1990). Developmental Benefits of Play for Children. Retrieved from: www. researchgate.net/publication/232469836_ Developmental_Benefits_of_Play_for_Chil dren. Accessed 13 Mar. 2024.

Blomqvist Mickelsson, T., & Stylin, P. (2021). Integrat-ing Rough-and-Tumble Play in Martial Arts: A Practitioner’s Model. Retrieved from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ fpsyg.2021.731000/full

Branje, S., de Moor, E. L., Spitzer, J., & Becht, A. I. (2021). Dynamics of Identity Development in Adolescence: A Decade in Review. Re trieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC9298910/

Brito A. D., Soares A. B. (2023). Well-Being, Charac ter Strengths, and Depression in Emerg ing Adults. Retrieved from: https://www. frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/arti cles/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1238105/full

Brown S., Vaughan C. (2009). Play: How it Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigo rates the Soul. Avery.

Butler, S. (2021). The Development of Market-Driven Identities in Young People: A Socio-Ecological Evolutionary Approach. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC8258256/

Cai, Jingxue, and Lian, Rong. (2022) Social Sup port and a Sense of Purpose: The Role of Personal Growth Initiative and Academic Self-Efficacy. Retrieved from: www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8793795/.

Consiglio, I., & van Osselaer, S. M. J. (2022). The Ef -fects of Consumption on Self-Esteem. Re -trieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S2352250X22000537

Demaske, A. S. (2020). Personal Growth Initiative, Need Satisfaction, and Subjective WellBeing: Testing a Process Model. Retrieved from: https://wakespace.lib.wfu.edu/bitstream/ handle/10339/96950/Demaske_ wfu_0248M_11565.pdf

Ho W. W. Y. (2022). Influence of Play on Positive Psychological Development in Emerging Adulthood: A Serial Mediation Model. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC9763996/

Kolb, K. H. (2022). Retail Inequality Reframing the Food Desert Debate. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Lancaster M. R., Callaghan P. (2020). The Effect of Exercise on Resilience, its Meditators and Moderators, in a general population during the UK COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020: a Cross-Sectional Online Study. Retrieved from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/ articles/10.1186/s12889-022-13070-7

Lipson S. K., Zhou S., Abelson S., Heinze J., Jirsa M., Morigney J., Patterson A., Singh M., Eisenberg D. (2022). Trends in College Student Mental Health and Help-Seeking by Race/Ethnicy: Findings from the National Healthy Minds Study, 2013-2021. Retrieved from: https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35307411/

Moghaddaszadeh A., Belcastro A. (2021). Guided Active Play Promotes Physical Activity and Improved Fundamental Motor Skills for School-Aged Children. Retrieved from: https:// www.researchgate.net/publication /348814446_Guided_Active_Play_Pro motes_Physical_Activity_and_Improves_ Fundamental_Motor_Skills_for_School-Aged_ Children

Moore B., Woodcock S., Dudley D. (2021). Well-being warriors: A randomized controlled trial examining the effects of martial arts training on secondary students’ resilience. Retrieved from: https://btateam.org/ wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Well-Being -Warriors-A-Randomized-Controlled-Trial -Examining-the-Effects-of-Martial-ArtsTraining-on-Secondary-Students.pdf

Oh, G.-E. G. (2021). Social Class, Social SelfEsteem, and Conspicuous Consumption. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC7905187/

Orenstein, G. A., & Lewis, L. (2022). Eriksons Stages of Psychosocial Development - StatPearlsNCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved from: https://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556096/

Reynes E., Lorant J. (2001). Do competitive martial arts attract aggressive children? Perceptual and Motor Skills 93, 382-386. Retrieved from: https://journals-sagepub-com.proxy.library. nyu.edu/doi/pdf/10.2466/pms.2001.93.2.382.

Reynes E., Lorant J. (2002a). Effect of traditional judo training on aggressiveness among young boys. Perceptual and Motor Skills 94(1), 2125. Retrieved from: https://journals-sagepubcom.proxy.library.nyu.edu/doi/pdf/10.2466/ pms.2002.94.1.21.

Reynes E., Lorant J. (2002b). Karate and aggressive ness among eight-year-old boys. Perceptual and Motor Skills 94, 1041-1042. Retrieved from: https://journals-sagepub-com.proxy. library.nyu.edu/doi/pdf/10.2466/ pms.2002.94.3.1041.

Reynes E., Lorant J. (2004). Competitive martial arts and aggressiveness: a 2-yr. longitudinal study among young boys. Perceptual and Motor Skills 98, 103-115. Retrieved from: https://journals-sagepub-com.proxy.library. nyu.edu/doi/pdf/10.2466/pms.98.1.103-115.

Richter, J. (2022). Mental Health & Higher Education in New York: A Call for a Public Policy Response. Retrieved from: https://mhanys.org/ wp-content/uploads/2022/06/20220222_ MHANYS_MentalHealthHigherEdWhitePaper. pdf

Shrivastava A., Desousa A. (2016). Resilience: A Psychobiological Construct for Psychiatric Disorders. Retrieved from: https://pubmed. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26985103/

Van Vleet M., Feeney B. (2015). Play Behavior and Playfulness in Adulthood. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication /283280677_Play_Behavior_and_Playfulness _in_Adulthood

Warde, A. (1994). Consumption, Identity-Formation and Uncertainty. Retrieved from: https://jour nals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00380385940 28004005

Worsley J. D., Harrison P., Corcoran R. (2021). Accommodation Environments and Student Mental Health in the UK: The Role of Relational Spaces. Retrieved from: https:// pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34008464/

Yilmaz, E. (n.d.). Identity: Definition, Types & Examples. Retrieved from: https://www.berke leywellbeing.com/identity.html

Zivin G., Hassan N. R., DePaula G. F., Monti D. A., Harlan C., Hossain K. D., Patterson K. (2001). An effective approach to violence prevention: Traditional martial arts in middle school. Adolescence, 36(143), 443–459. Retrieved from: https://link.gale.com/apps/ doc/A82535317/AONE? u=nysl_me_newyo rku&sid=AONE&xid=21bcb317.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank all those who made this possible.

Collin Yao

Yang Xiuqing

Yan Yu

Garry St. Leger

Erik Nicholson

Kenneth Kolb

Brooke Feeney

David Berreby

Chris Hyorok Lee

Bryan Leng

Hima Bijulal

Vincent Tang

Jeannie C

Hen Z

Mike Howell

Hiba Abid

Ghada Badawi

Peter Terezakis

Justin Chon

Akshita Bawa

Anastasia Gorski

Julia Knoll

Kristina Lee

Allan Chochinov

Siclair Smith

Kristine Mudd

Krissi Xenakis

Bill Cromie

Sam Potts

Alexa Cohen

Alexandre Pierre De Looz

Emilie Baltz

Becky Stern

Victoria Shen

Anne Quito

Rachael Yaegar

Megan Ford

Michael Chung

Sloan Leo

Heba Jaleel

Ria John

Shun Cheng Hsieh

Sama Srinivas

Jacey Chen

Nigel Keen

Rohitha Remala

Prerna Sharma

Rora Pan

Rui Yang

Wren Wang

Cyntia Abarca

Patrick Baca Chandler

Josh Corn

Jospeh Weissgold

Oscar De La Hera Gomez

And a special thanks to my editor Jana Weinstein.

© Brydon Yao

All rights reserved.

School of Visual Arts MFA Products of Design

New York, NY May 2024

For Inquiries contact brydon.zhy@gmail.com