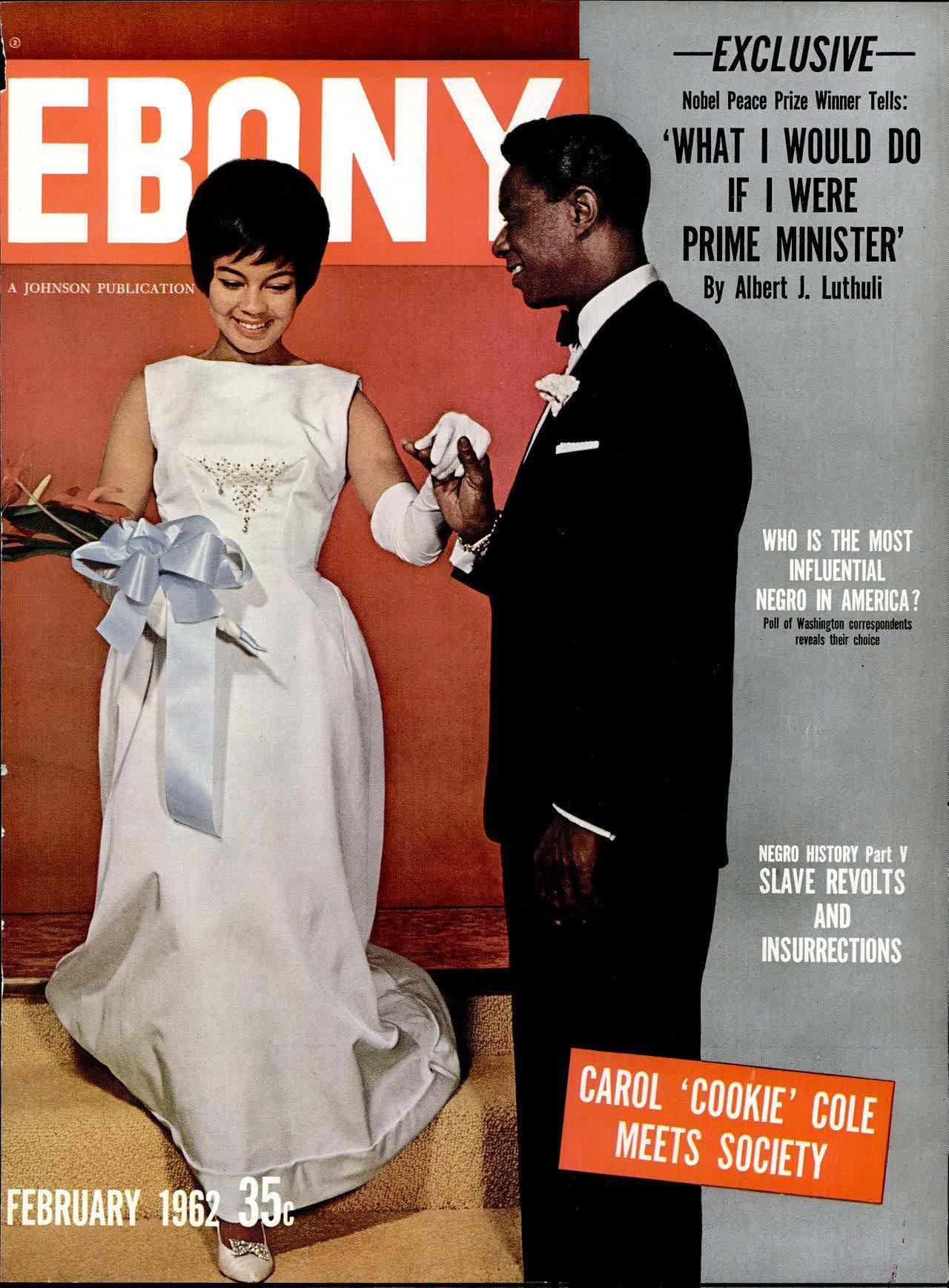

EBONY

More Than a Magazine

BY MARIAME KABA

Cover Art: Ebony Magazine, Feb. 1962

© 2024

Design: Cindy Lau

Harry Belafonte, Coretta Scott King, and Duke Ellington performing the month the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended, December 1956. Photo by G. Marshall Wilson.

“Ebony arrived in 1945…to inform us that our lives were so important, they could never be edited out of the history of our people,” Maya Angelou wrote in 1995.

Over its almost 80-year history, Ebony magazine was a crucial chronicle of African-American life and history, highlighting Black achievement, success, and struggle. The creators intentionally made the magazine for a Black audience that was tired of a white mainstream press which either ignored Black life or framed it through stereotypes and prejudice. Ebony transformed American media by giving Black Americans an unprecedented platform to see and speak to themselves.

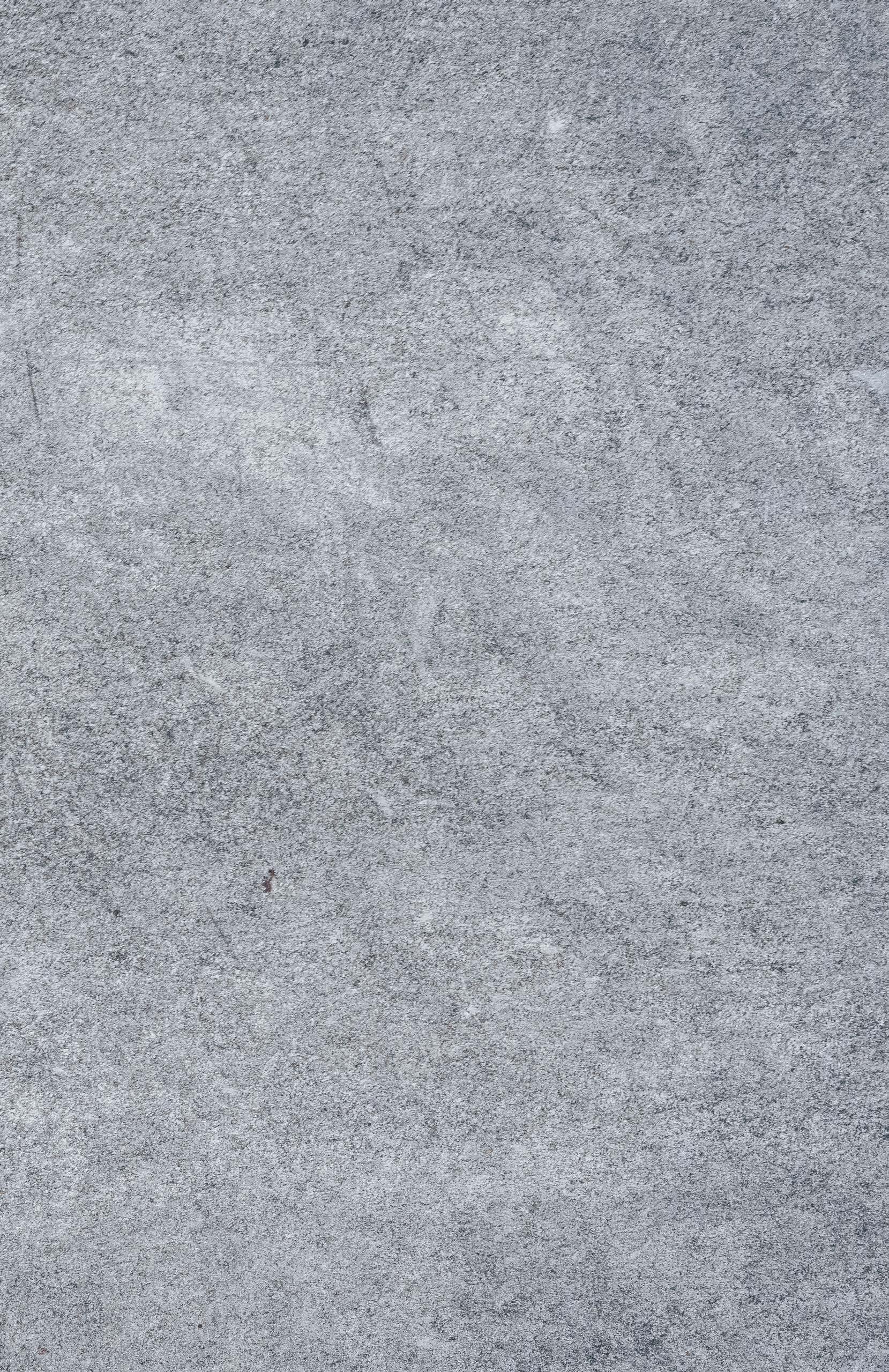

Chicago-based publisher John H. Johnson (1918–2005) released the first issue of Ebony two months after World War II ended. Inspired by the format of the general-interest, photograph-heavy Life, the first issue featured interviews with author Richard Wright and singer Hazel Scott. It also included a statement of purpose from the editors:

“We like to look at the zesty side of life. Sure, you can get all hot and bothered about the race question (and don’t think we don’t), but not enough is said about all the swell things we Negroes can do and will accomplish. Ebony will try to mirror the happier side

Ebony magazine, Volume LX, Number 12 honoring the life of John H. Johnson, the founder of Johnson Publishing Company, publisher of Ebony magazine.

of Negro life—the positive, everyday achievements from Harlem to Hollywood. But when we talk about race as the No. 1 problem of America, we’ll talk turkey.”

The formula of Black celebrity, aspirational optimism, and Civil Rights proved to be wildly popular with Black readers. By its second issue Ebony was “the biggest Negro magazine in the world in both size and circulation,” according to its editors. By its one-year anniversary, its circulation had hit 400,000 copies per month. Its actual readership would have been many times that number, since it was especially popular in barber shops and beauty parlors, where multiple customers would flip through each issue.

Some Black academic writers criticized Ebony for focusing on what sociologist E. Franklin Frazier called a Black bourgeoise “make-believe world” which did not grapple with the discrimination and violence most Black readers faced. There was some truth to that charge. At the same time, though, Ebony did over the years work to balance images of Black glamor and Black everyday life with support for the Civil Rights struggle.

“Ebony magazine was more than a publication— to black America, it was a public trust.”

Karen Grigsby Bates

One iconic image from the magazine, for example, showed singer Harry Belafonte, composer Duke Ellington, and civil rights leader Coretta Scott King—

all in elegant formalwear—singing together in 1956, the month after the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended. Another from the same year showed gospel singer Mahalia Jackson in her Southside Chicago home. White racists had tried to drive Jackson out of her house, but the photo shows her engaged in the typical homeowner’s work of mowing the lawn. And again in the same year, Jet, Ebony’s sister magazine, ran photos at his mother’s request of 14-year-old Emmett Till in his coffin following his horrific lynching in Mississippi. “Black joy has been shared with Ebony reader through pictures,” the editors wrote in 1975, “and so has black tragedy.”

Over the decades, Ebony chronicled Black history and achievement, creating what scholar Vincent Harding has called “a kind of running contemporary history

Above: Mahalia Jackson. Photo by staff photographer.

of [the] black struggle in America.” The magazine featured Martin Luther King with many cover stories, including a 1968 cover showing his widow, Coretta Scott King, at his funeral following his assassination. Executive editor Lerone Bennett Jr. wrote an indepth profile of Civil Rights and Black Power leader Stokely Carmichael. In 1977, the magazine ran a feature story on the Black members of Jimmy Carter’s administration. It covered Harold Washington’s rise to become Chicago’s first Black mayor in 1983.

“Image power is a prerequisite of economic and political power.”

John H. Johnson

The magazine’s success helped show the existence and profitability of a Black consumer market. Advertisers like Coca Cola and Virginia Slims began using Black models in their ads in the 70s; they would sometimes create

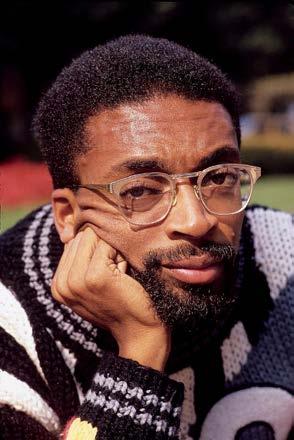

Left: Miriam Makeba and Stokely Carmichael, 1968. Photo by G. Marshall Wilson.

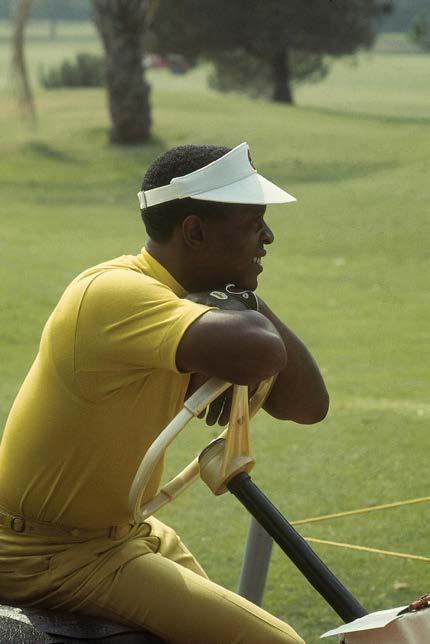

Right: Harold Washington, 1980. Photo by Vandell Cobb.

ads specifically for Ebony itself. John Johnson’s wife Eunice organized the Ebony Fashion Fair in 1958. They held the event annually for fifty years, showcasing Black models wearing clothes often created by Black designers like Patrick Kelly and Stephen Burroughs. When Eunice noticed Black models had to mix their own make-up for the fair, she created Fashion Fair Cosmetics. Sold in department stores in 1973, it was the first high-end cosmetic line for women of color.

In the 1980s, Ebony’s popularity continued to grow; advertisers estimated it reached an incredible 40% of all Black adults during the 1980s, and its circulation reached 7 million. That was the magazine’s peak, however. Like other print publications, the rise of the internet badly damaged Ebony’s ad revenue. A private equity firm bought it in 2016, and three years later it filed for bankruptcy amidst accusations that it had failed to pay freelancers. Many thought the magazine was finished, but the magazine underwent reorganization and relaunched as a digital publication in 2021.

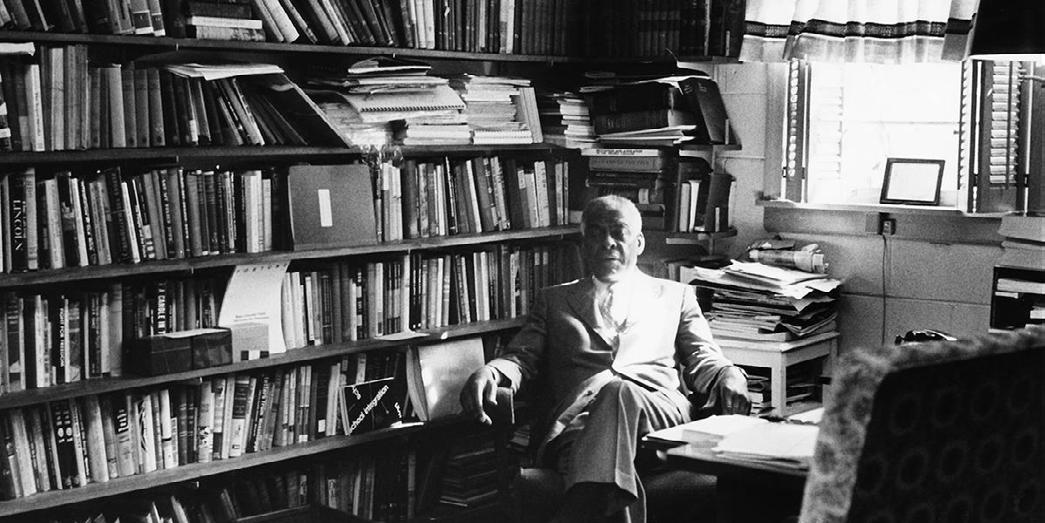

“Image power is a prerequisite of economic and political power,” Johnson wrote in 1975. Ebony hired Black photographers like Maurice Sorrell and Moneta Sleet, Jr. and journalists like Lerone Bennett and Era

EBONY'S INCREDIBLE POPULARITY

of Black adults were reached by Ebony during the 1980s

in circulation at its peak

Bell Thompson to create intimate portraits of Black celebrities, descriptions of Black life, and chronicles of Black history. It built and cultivated Black economic power by identifying and making visible an expansive audience of Black consumers. And it advocated for Black civil rights by highlighting Black achievements and reporting on racial injustice. Writing for NPR’s Codeswitch, one of the many Black focused platforms that built on Ebony’s success and example, Karen Grigsby Bates, summed up the publication’s legacy. “Ebony magazine was more than a publication—to black America, it was a public trust.”

at home with her tools – a yellow legal pad, thesaurus, dictionary, and Bible, 1982.

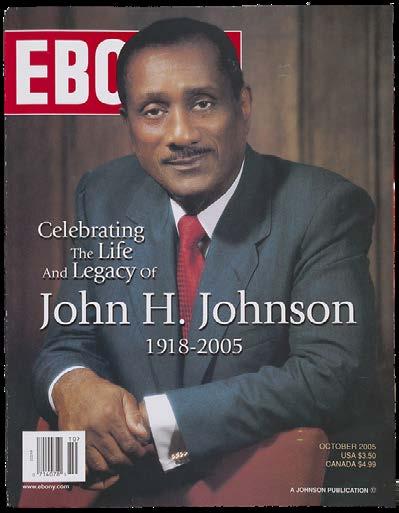

at home with his daughter Sherri in an Ebony feature about his family, 1957.

Left: Writer Maya Angelou working

Photo by Moneta Sleet Jr.

Right: Sidney Poitier

Photo by G. Marshall Wilson.

Sources Consulted:

“75 Years of Ebony Magazine,” National Museum of African American History and Culture: Smithsonian, 2020. https://nmaahc.si.edu/75-years-ebony-magazine

E. James West, Ebony Magazine and Lerone Bennett Jr.: Popular Black History in Postwar America, Champaign/Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020.

E. R. Shipp, “Ebony, 40, Viewed as More Than a Magazine,” New York Times, December 6, 1985. https://www.nytimes.com/1985/12/06/ us/ebony-40-viewed-as-more-than-a-magazine.html

Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, “John H. Johnson,” Encyclopedia Britannica, January 15, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-H-Johnson

Karen Grigsby Bates, “Former ‘Ebony’ Publisher Declares Bankruptcy, and an Era Ends,” Code Switch: NPR, April 13, 2019. https://www. npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2019/04/13/712437648/formerebony-publisher-declares-bankruptcy-and-an-era-ends

M.L. Anderson, “’I Dig You, Chocolate City’: Ebony and Sepia Magazines’ Coverage of Black Political Progress, 1971–1977,” Jounral of African-American Studies 19, 398–409, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12111-015-9309-x

“Power, Politics, & Pride: Johnson Publishing,” WTTW, Accessed February 8, 2024. https://interactive.wttw.com/dusable-to-obama/johnson-publishing

Rachel Parker, “Black in Print: The History and Resurgence of Ebony Magazine,” 1956 Magazine, April 11, 2022. https://1956magazine.ua.edu/black-in-printthe-history-and-resurgence-of-ebony-magazine%EF%BF%BC/

“The first issue of ‘Ebony’ magazine is published,” This Day in History: November 1, Accessed February 8, 2024. https://www.history.com/ this-day-in-history/first-issue-ebony-magazine-published

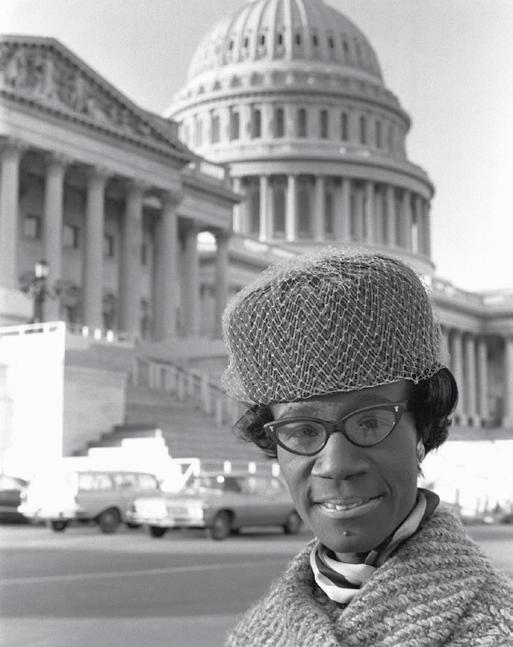

1 Dr. Benjamin Mays, 1971. / 2 Lee Elder, 1968. / 3 Thurgood Marshall with his wife Cecilia Suyat Marshall and son Thurgood Jr., 1956. / 4 Spike Lee, 1986. / 5 Langston Hughes, 1955. / 6 Shirley Chisholm, 1969. / All photos courtesy of The Johnson Publishing Company Archive.