Provide Heatwave Plan

Version: V2

Ratified by: FIC

Date ratified: 12/07/2023

Job Title of author:

Reviewed by Committee or Expert Group

Related procedural documents

Emergency Preparedness Resilience & Response (EPRR) Manager

Property, Health and Safety Group

Major Incident Plan

EPRR Policy

Business Continuity Policy

Service Business Continuity Plans

Review date: 12/07/2026

It is the responsibility of users to ensure that you are using the most up to date document template – ie obtained via the intranet.

In developing/reviewing this procedure Provide Community has had regard to the principles of the NHS Constitution.

Version Control Sheet

Version Date Author Status Comment

1 July2022 Emergency Preparedness Resilience & Response (EPRR)Manager

2 June2023 Emergency Preparedness Resilience & Response (EPRR)Manager

Approved Newplan (Replaces Adverse Weather Policy – HSPOL07)

Approved Updated Heat-Health Watch Systemanddatesinlinewith new UKHSA Adverse WeatherHealthPlan RemovedreferencetoCovid

1. Introduction

This plan provides the framework for coordinating Provides response to a Heatwave or a period of severe weather. It is not a standalone document and supplements the organisation’s existing Major Incident and Business Continuity Plans by providing additional information and guidance specific to mitigating, minimising and responding to the effects and disruptions of a heatwave. In line with national guidance the plan is:

• Constructed to deal with a wide range of scenarios;

• Based on an integrated, multi-sector approach;

• Built on effective service and business continuity arrangements;

• Responsive to local challenges and needs; and

• Supported by strong local, regional and national leadership measures.

The procedures within this plan are for use within the existing framework for command, control and coordination as detailed in the Provide Major Incident Plan. The activation of procedures from within this plan may or may not put the organisation at either Major Incident ‘STANDBY’ or ‘DECLARED’ status, with the final decision being made by the by the Provide Incident Director. When activated this plan contains procedures that allow the organisation to:

• Receive, and agree appropriate actions arising from, Heat-Health Watch notifications;

• Comply with any external reporting requirements and generate local situation reports as required;

• Reduce impact of the heatwave (including reducing the likelihood of excess deaths);

• Identify service users that are ‘high risk’ who might be at increased vulnerability during a heatwave;

• Ensure that critical services are maintained;

• Cope with localised disruptions to services;

• Provide timely, authoritative and up-to-date information for staff; and

• Return to normal working after a Heatwave as rapidly and efficiently as possible

This plan like all Provide’s emergency plans will be updated as new guidance is made available and following recommendations from internal (or external) incidents and exercises.

2. Purpose

The aim of this plan is to ensure that Provide can respond to severe weather disruptions to its business in a way that ensures that statutory obligations are met, and supports its overall vision and mission.

The objectives of this plan are to ensure:

1. Provide is compliant with its legal and regulatory obligations;

2. Critical and essential activities and services are identified, protected and ensure their continuity;

3. Stakeholder requirements are understood and can be delivered;

4. Staff, service users and the public are properly communicated with;

5. Staff receive adequate support and advice in the event of a heatwave

3. Definitions

The following terms and definitions are included within this document

Term Definition

Business continuity

Business Continuity Incident

Critical Incident

Civil Contingencies Act 2004

Civil Contingencies

Secretariat (CCS)

Capability of the organisation to continue to delivery of products or services at acceptable predefined levels following a disruptive incident

A business continuity incident is an event or occurrence that disrupts an organisation’s normal service delivery, below acceptable predefined levels, where special arrangements are required to be implanted until services can return to an acceptable level.

A critical incident is any localised incident where the level of disruption results in the organisation temporarily or permanently losing its ability to deliver critical services, patients may have been harmed or the environment is not safe requiring special measures and support from other agencies, to restore normal operating functions

The Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (CCA) delivers a single framework for the protection of civil protection in the UK.

The Act divides responder organisations into two categories; Category One and Category Two depending on the extent of their involvement in civil protection work

The Civil Contingencies Secretariat (CCS), or Cabinet Office, is to ensure the United Kingdom's resilience against disruptive challenge, and to do this by working with others to anticipate, assess, prevent, prepare, respond and recover.

Invocation Act of declaring that the business continuity arrangements need to be put into effect in order to continue delivery of key products or services

Major Incident

4. Duties

4.1

Chief Executive

A major incident is any occurrence that presents serious threat to the health of the community or causes such numbers or types of casualties, as to require special arrangements to be implemented.

The Chief Executive has the overall responsibility for emergency preparedness, resilience and response (EPRR) and is accountable to the Board for ensuring that systems are in place to facilitate an effective incident response including the continuity of critical/essential services.

4.2 Accountable Emergency Officer (AEO)

The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Provide Health is the nominated Accountable Emergency Officer (AEO) who is responsible for ensuring the full implementation of the organisation’s emergency preparedness resilience and response arrangements (on behalf of the Provide Group Chief Executive). The AEO may be called upon to help in the response of any incident that result in the corporate (this) plan being invoked

4.3 Emergency Preparedness Resilience & Response Manager

The Emergency Preparedness Resilience & Response (EPRR) Manager is responsible for assisting the AEO in implementing the emergency preparedness resilience and response arrangements and where available may be asked to provide advice during the incident response

4.4

All staff

All staff have a role to play in business continuity in raising alerts, assisting service leads/managers in keeping the service running as normal as possible, and being flexible in their working arrangements.

4.5 Heads of Service/Service Leads

Heads of Service/Service leads keep their business as usual role in a business disruption including those resulting from a severe weather incident and are responsible forthe coordination of the team andfunctions for which they are usually responsible. All Heads of Service/service leads need to be aware of their team’s essential and critical activities.

4.6 Associate Directors/on-call manager (Operational/Bronze)

The role of the Associate Director is to ensure Business Continuity arrangements are implemented within the services. In working hours, they or their nominated deputy are also the first point of contact to manage any incident or disruption that requires extra resources in any of the named teams or functions. Out of hours, this function will be completed by the on-call manager.

4.7 Director/Senior Manager on-call (Tactical/Silver)

The role of the Director or senior manager on-call (Tactical/Silver if a major/critical incident has been declared) is to coordinate the business continuity measures across the organisation.

4.8 Director on-call/Strategic

(gold) commander

The Director on-call or Strategic (Gold) Commander if a major incident has been declared) sets the strategic direction for the organisations response and provides final oversight and approval for the logs, authorises external situation reports, mutual aid arrangements and communications

5. Consultation and Communication

This plan has been reviewed by the Property, Health and Safety Group and ratified by the Finance and Investment Committee (FIC).

6. Monitoring

NHS England EPRR Annual Assurance Process

All NHS organisations and providers of NHS funded care are held to account by NHS England for having effective EPRR processes and systems in place. An annual assurance process is used by NHS England to seek assurance that organisations are prepared to respond to an emergency and have the resilience in place to continue to provide safe patient care during a major incident or business continuity event. The indicators are set against the EPRR core standards and an action plan is agreed against any standard that is assessed as requiring improvement. Progress against the action plan is monitored through Senior Leadership Team (SLT)

Business continuity or major/critical incidents will be monitored by the EPRR manager through SLT and any lessons identified will be considered for changes to EPRR practice.

7. Heatwave information / risk factors / regional and national planning

7.1 Planning information

Increasing temperatures in excess of approximately 25ºC are associated with excess summer deaths, with higher temperatures being associated with greater numbers of excess deaths (as seen in a heatwave); at 27ºC or over, those with impaired sweating mechanisms find it especially difficult to keep their body cool.

When the ambient temperature is higher than skin temperature, the only effective heat-loss mechanism is sweating. Therefore, any factor that reduces the effectiveness of sweating such as dehydration, lack of breeze, tight-fitting clothes or certain medications can cause the body to overheat. Additionally, thermoregulation, which is controlled by the hypothalamus, can be impaired in the elderly and the chronically ill, and potentially in those taking certain medications, rendering the body more vulnerable to overheating.

However, the main causes of illness and death during a heatwave are respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Part of this rise in mortality may be attributable to air pollution, which makes respiratory symptoms worse. The other main contributor is the effect of heat on the cardiovascular system as in order to keep cool, large quantities of extra blood is circulated to the skin. This can cause strain on the heart, which for elderly people and those with chronic health problems can be enough to precipitate a cardiac event, for example heart failure. Additionally, death rates increase in particular for those with renal disease. A peak in homicide and suicide rates during previous heatwaves in the UK has also been observed.

Sweating and dehydration can also affect electrolyte balance. For people on medications that control electrolyte balance or cardiac function, this can also be a risk. Medicines that affect the ability to sweat, thermoregulation or electrolyte imbalance can make a person more vulnerable to the effects of heat. Such medicines include anticholinergics, vasoconstrictors, antihistamines, drugs that reduce renal function, diuretics, psychoactive drugs and antihypertensives. Ozone and PM10s also increase the level of cardiovascular-related deaths.

7.1.1 Effects of heat on health

The main effects of heat on health are seen in those with existing respiratory or cardiac conditions. However, heat can cause its own specific illnesses including –

Heat Cramps: caused by dehydration and loss of electrolytes, often following exercise.

Heat Rash: small red itchy papules.

Heat Oedema: mainly in the ankles due to vasodilation and retention of fluid.

Heat Syncope: dizziness and fainting due to dehydration, vasodilation, cardiovascular disease and certain medications.

Heat Exhaustion: is more common. It occurs as a result of water or sodium depletion, with nonspecific features of malaise, vomiting and circulatory collapse, and is present when the core temperature is between 37 and 40ºC. Left untreated, heat exhaustion may evolve into heatstroke.

Heat Stroke: can become a point of no return whereby the body’s thermoregulation mechanism fails. This leads to a medical emergency, with symptoms of confusion; disorientation; convulsions; unconsciousness; hot dry skin; and core body temperature exceeding 40ºC for between 45 minutes and eight hours. It can result in cell death, organ failure, brain damage or death.

7.1.2 Heat and excess death

The excess deaths and illness related to a heatwave occur in part due to our inability to adapt and cool ourselves sufficiently. Therefore, relatively more deaths occur in the first days of a heatwave, as happened in 2006 during the first hot period in June (which did not officially reach heatwave status). This emphasises the importance of being well prepared for the first hot period of the season and at the very beginning of a heatwave. High temperatures are also linked to poor air quality with high levels of ozone which are formed more rapidly in strong sunlight; small particles (PM10s) also increase in concentration during hot, still air conditions. Both are associated with respiratory and cardiovascular mortality. Additionally, there may be increases in sulphur dioxide emissions from power stations (due to an increase in energy use for air-conditioning), which in turn worsens the symptoms of asthma.

7.1.3 Heat and urban areas

During a heatwave it is likely to be hotter in cities than in surrounding rural areas, especially at night. Temperatures typically rise from the outer edges of the city and peak in the centre. This phenomenon is referred to as the ‘Urban Heat Island’ and its impact can be significant. In London during the August 2003 heatwave, the maximum temperature difference between urban and rural locations reached 9ºC on occasions.

It should be noted that the effects of a heatwave could be quite vastly different across the organisation dependant on how urban the facility is, and this will need to be monitored.

7.2 Risk factors

7.2.1 In a moderate heatwave it is mainly the high risk groups listed below who are affected. However, during an extreme heatwave normally fit and healthy people can also be affected. High-risk groups include:

Community: Over 75, living on own and isolated, severe physical or mental illness; urban areas, south-facing top flat; alcohol and/or drug dependency, homeless, babies and young children, multiple medications and over-exertion.

Care home or hospital: over 75, frail, severe physical or mental illness; multiple medications; babies and young children (hospitals).

Medications: The following drugs are theoretically capable of increasing risk in susceptible individuals.

7.2.1

Heat and Respiratory Illness

The heat can affect anyone, but some people run a greater risk of serious harm. Many people who are at higher risk of ill health due to heat are also at higher risk of severe illness from respiratory related illness.

Clinical vulnerabilities that have been linked with worse outcomes from respiratory illness that are also risks for heat related harms are:

• high blood pressure

• chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

• heart and lung conditions (cardiovascular disease)

• conditions that affect the flow of blood in the brain (cerebrovascular disease)

• kidney disease

7.3

Preventative Measures

The key way of preventing heat-related illness and death is by ensuring people keep themselves cool; the best ways they can achieve this are by –

• Keeping out of the sun between 11am and 15:00;

• Wearing sunscreen, hats and loose-fitting cotton clothing;

• Avoiding extreme physical exertion;

• Drinking plenty of cold drinks and avoiding excess alcohol, caffeine and hot drinks;

• Monitoring their daily fluid intake, particularly if they have several carers or are not always able to drink unaided

• Eating cold foods, particularly salads and fruit with high water content.

• Taking cool showers or at least an overall body wash;

• Sprinkling their clothes with water regularly and splashing cool water on their face and the back of their neck. A damp cloth on the back of the neck helps temperature regulation

• Ensuring they stay cool at home

• Keeping windows exposed to the sun closed during the day and only opening windows at night when the temperature has dropped (please note that security risks will need to be assessed when leaving windows open at night);

• Turning off non-essential lights and electrical equipment.

Provide extra care:

• Keep in regular contact throughout the heatwave, and try to arrange for someone to visit or contact at least once a day

• Keep giving advice on what to do to help keep cool

• During extended periods of raised temperatures ensure that persons over the age of 65 are advised to increase their fluid intake to reduce the risk of blood-stream infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria

UKHSA have produced heatwave guidance that includes leaflets and posters and specific resources for heat risk. These can be accessed via their website https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/heatwave-plan-for-england

For advice staff. patients and carers can also be directed to https://www.nhs.uk/summerhealth and http://www.sunsmart.com.au/

7.4

Staff advice

During hot weather to help staff remain cool they should consider the following actions;

• Drink plenty of water

• If possible, restrict the length of time that they are exposed to hot conditions and avoid sources of heat and direct sunlight, particularly during the hottest time of the day; 11.00 –15.00

• Dress appropriately, removing layers where possible (as far as possible, whilst complying with dress code, health and safety and infection control requirements of the job); managers are encouraged to be flexible with dress code as long as patient care and safety are not compromised,

• Open windows where possible and shade them by closing curtains or blinds to reduce the heating effects of the sun

• In areas where there is poor air circulation, it may be beneficial to use a fan to move air towards windows and mechanical extraction.

Portable fans should NOT be used in the following situations:

‒ In a room where a patient is managed with respiratory (airborne) precautions

‒ In a room where a patient is managed with droplet or contact precautions, for example, Clostridiodes difficile, MRSA, norovirus

‒ During outbreaks of infection – this applies to all areas associated with the affected unit/ward inc. staff rooms, offices etc.

‒ In rooms were Aerosol-Generating Procedures (AGPs) are undertaken

‒ In rooms with directed airflow e.g. positive or negative pressure rooms

‒ In areas where sterile supplies are stored or where medical device reprocessing occurs, for example endoscopy units

Prior to commencing use of a portable fan, in a clinical area confirm:

‒ A risk assessment has been performed (and documented) for each occasion

‒ The use of a fan is determined to be of benefit to the patient’s clinical condition or comfort

‒ Where appropriate, alternative cooling methods have been attempted with no success e.g. removing bedding, application of cold compresses, anti-pyretics etc.

‒ The patient is in a non-restricted use location (see above)

‒ The fan is clean, with a green “I am clean sticker” attached (dated within 7 days)

‒ The fan has a current PPM / PAMs sticker

If a portable fan is sanctioned for use in clinical areas the following tips may be used:

‒ Positioning:

‒ Position the fan so airflow is directed towards the patient but not directly at them

‒ Position fan on a clean surface at the patient’s bed level or higher

‒ Ensure airflow is not directed towards the door of the room or across environmental surfaces. The direction of flow should be upwards toward the ceiling, avoiding smoke detectors

‒ Ensure airflow is not blowing directly on open wounds or directly into the patient’s face

‒ Turn the fan off before the following:

‒ Any sterile or aseptic procedure e.g. intravenous cannulation, catheterisation, wound dressing change, podiatric procedures etc.

‒ Any procedure that may result in sprays or splashes of body fluids

Portable fans in non-clinical areas

‒ Do not direct fans towards open doors

‒ Do not direct fans towards individuals – position them to direct into the room

‒ Fans must be clean and with a green “I am clean” sticker attached. Sticker must be current (within 7 days)

Decontamination (cleaning) of ALL fans

‒ Ensure a local cleaning schedule (and instructions) is available for use

‒ Ensure responsibilities for cleaning are documented in the schedule

‒ Wear appropriate PPE to perform the task – disposable apron and gloves

‒ If available, follow manufacturer’s instructions to clean the fan after each individual use (and prior to storage), and / when visibly contaminated (with dust and/or body fluids)

‒ Clean with detergent or universal (combined) wipes and discard into black (household/domestic) waste bags

‒ Ensure hands are washed following PPE removal and disposalUse of portable air conditioning unit (following risk assessment)

• Portable air conditioning units have increased in popularity in recent years and require careful maintenance to ensure efficiency and safety. All ACUs should be recorded on an inventory by Estates and approved for use with up to date PPM checks/sticker.

Management of same to include a cleaning / maintenance schedule for example:

‒ Clean exterior with a damp cloth weekly whilst in use

‒ Replace air filters in accordance with manufacturer’s guidance

‒ Clean pre-filters bi-weekly

‒ Routinely inspect condenser coils

‒ Ensure any exhaust hoses are kept short and straight to maximise efficiency and to avoid moisture build-up

‒ Regularly drain hoses (do NOT empty into clinical handwash basins)

‒ Ideally, purchase ventless ACUs

‒ Efficiency is reduced in dusty, dirty and humid areas so avoid use in these places

‒ When not in use, store clean and covered in a location away from direct sunlight and with a constant ambient temperature

For staff wearing PPE for prolonged periods;

• Take a drink before donning PPE

• Remove your mask when you can and take regular short breaks, even ten minutes will help –find a quiet spot or social distance in an office

• Frequently apply lip balm and face moisturiser – include your ears

• Beware of sore or red patches on the bridge of your nose or strap contact points behind the ears – loosen the mask or protect your skin with a plaster

• ‘Buddy up’ – ask your colleague or teammate how they are managing the mask and remind them of these tips

For staff working in offices there is no maximum temperature. For areas that are experiencing hot conditions a thermometer should be provided in suitable locations. Each service will need to procure a thermometer ideally with a digital display. Staff should monitor the temperature on a temperature log (see appendix E) and if required seek further advice from Estates and/or the Health and Safety Manager. Incidents involving ill-health effects i.e. nausea, sickness, dizziness, lack of concentration to staff patients or visitors for which heat is thought to be a contributory factor should be recorded on Datix with the temperature log attached.

7.5 Regional and national planning

Planning for a heatwave is conducted at a national, regional and local level alongside severe weather now combined in an ‘Adverse Weather Plan for England’ that sets out the responsibilities at a national, regional and local level for alerting people once a heatwave has been forecast, and for advising them on what to do during a heatwave.

The core elements of the plan are:

• The ‘Heat-Health Watch’ system that operates from 1 June to 30 September;

• The ‘trigger levels’ and response requirements from all agencies;

• Detailed role of UKHSA, NHS England, Met Office, Hospitals, NHS Trusts, NHS Providers, Commissioners, Health & Social Care Services and care, residential and nursing homes;

• How the media will provide advice.

The UKHSA Adverse Weather Health Plan and the supporting guides can be found online from the following sources:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/heatwave-plan-for-england: http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/uk/heathealth/

8. Heatwave notification procedures

8.1 Heat-health Watch System

A Heat-Health Watch alert system will operate in England from 1 June to 30 September each year which is in line with other weather warning systems in operation within England and during this period, the Met Office may forecast heatwaves, as defined by forecasts of day and night-time temperatures and their duration.

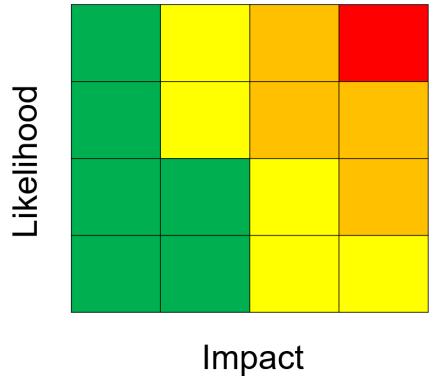

The Heat-Health Watch system comprises three main alerts (yellow, amber or red) outlined in Table 1 and described in further detail below. The alerts will be given a colour (based on the combination of the impact the weather conditions could have, and the likelihood of those impacts being realised).

• A Green Alert is general summer preparedness. No alert will be issued as the conditions are likely to have minimal impact and health but allows the organisation to be ready and plan to escalate the response as required.

• Yellow and Amber Alerts cover a range of potential impacts (including impacts on specific vulnerable groups (for example people sleeping rough) through to wider impacts on the general population) as well as the likelihood (low to high) of those impacts occurring. This information should aid the organisation in making decisions about the appropriate level of response during the alert period.

• A Red Alert would indicate significant risk to life for even the healthy population. A red warning would be issued in conjunction with and aligned to a red National Severe Weather Warning Service Extreme Heat warning and is a judgement at national level made as a result of a crossGovernment assessment of the weather conditions and occurs when the impacts of heat extend beyond the health sector.

Within any alert that is issued, the combination of impact and likelihood undertaken by UKHSA and the Met Office will be displayed within a risk matrix as illustrated in Appendix A.

Green Alert Summer Preparedness

Little impact likely to be observed on health, healthcare services and social care. Provision but to plan for Summer and be ready to escalate response.

Yellow Alert Response

Increased mortality amongst vulnerable population groups (such as the elderly) Potential for increased usage of healthcare services by vulnerable population. Internal temperatures in care settings may become very warm increasing risk of indoor overheating.

Amber Alert Enhanced Response

In addition to the above impacts may also be seen in younger age groups. Increased demand for GP services, ambulance call out, remote healthcare services (NHS111) likely. Impact on ability of services delivered due to heat effects on workforce possible (i.e. warm buildings and travel issues)

Red Alert Major Incident – Emergency response

In addition to the above, significant increased demand on all health and social care services.

Indoor environments likely to be hot making provision of care challenging

As levels are based on a risk and likelihood, there may be jumps between levels. Following Alert level Amber, it is considered best practice to wait until temperatures cool to Alert level Yellow before stopping Alert Amber actions.

8.2 Receiving Heat-health watch Alerts and Activating the Plan

From 1 June to 30 September, the Met Office sends out a Heat-Health Watch alert, which advises as to the current level to the Chief Executive or nominated deputy of every NHS England Region, Health Trusts, local authority and social care organisation in England, and to Health Board CEs and local authority Directors of Social Services in Wales.

Provide is also directly set up to receive Met office alerts; they are sent by email to the Emergency Preparedness Resilience and Response (EPRR) Manager and the generic email address PROVIDE.ep@nhs.net

In the event of receiving an alert from any of the agencies, the EPRR Manager/ Director On-call will make an assessment of the alert / warning to determine whether further action is required. Initial further actions may consist of:

• A follow-up call with the issuing agency;

• A follow-up email either from the issuing agency or local authority;

• Telephone discussion with senior management to agree further actions/monitoring;

• Dissemination of alert to staff advising them to carry out the Heat-Health Watch Response Actions as detailed in Section 9