“WE SEE THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY”: Thinking the Fragment in Theology

Thank you to President Walton and to Dean Frederick for the beautiful introductions. This is not just a celebratory moment for me; it is a celebratory moment for my entire community. To my mother Connie Woods and my Father Wilbur Day and their respective spouses. They empowered me to believe that I could do anything, which included making a living from the three things I love to do the most: read all day, write, and then talk about the ideas I read and wrote about all day (mom – I have finally written my paper!). To my grandma, Gypsy Harris – your presence is an enduring example of God’s love and care to our family. And finally, to my husband Austin Moore and our daughter Ariella Rose. You two are the best of who I am and of who I will ever be. With you two, my cup is always full and overflowing. Now to my address.

In my address, I briefly revisit my work on the Azusa Street revival of 1906, turning specifically to the charge of Azusa’s heterodox character, and how the heterodox shape of Azusa’s religious life opens to a fragmentary way of thinking and doing theology, particularly a theology of Spirit. After clarifying what I mean by the idea of the fragment, I offer a meditation on an image within the The Church of God in Christ (COGIC), a black Pentecostal denomination that emerges from Azusa, as this image or fragment (located on your program) perhaps opens to theologies of incompletion, paradox, wonder, and even delight, allowing us to sense the dynamic and apophatic ways Spirit is already present in the possibilities and uncertainties of our personal and political lives.

REVISITING AZUSA & ITS HETERODOX CHARACTER

My scholarship and teaching over the last fifteen years of my career have centered on African American religion at the intersections of political theology, critical social theories, economics, and black feminisms/womanisms. In 2015, I began researching on the topic of Azusa, not realizing that this study would take almost a decade to research and write, culminating in my most recent book, Azusa Reimagined: A Radical Vision of Religious and Democratic Belonging. In Azusa Reimagined, I challenge religious and theological scholarship that early Pentecostalism, namely the Azusa Revival, was nothing more than a pietistic, otherworldly, and apolitical form of black religiosity. Instead, I argue that the Azusa revival of 1906 in Los Angeles, CA, can be interpreted as a direct critique of US racial capitalism at the start of the 20th century. Through its sermons and religious rituals, Azusa critiqued racist conceptions of citizenship that guided early

American capitalist endeavors such as 20th century world fairs and expositions. Azusa also envisioned practices of care and togetherness than the white nationalist loyalties early US capitalism encouraged. In this way, Azusa not only was a revival seeking the spiritual health of its members but also was a radically potent political critique of racial capitalism at the start of the 20th century.

Theologically speaking, in my book Azusa Reimagined, I was particularly drawn to how white evangelical Christian leaders and ministers interpreted Azusa: outside of orthodoxy, a heterodox movement, even heretical. What has been hidden and even erased in relation to Azusa is that Azusa held at the center of its Spirit experience religious practices of the previously enslaved, which caused a firestorm of controversy on whether this movement was truly “Christian.” Much of white Pentecostal scholarship

in the US has argued that those who gravitated toward holiness movements and the early Pentecostal movement left Baptist and Methodist churches due to these churches’ failure to live into ideas of sanctification as well as speaking in tongues as the first evidence of the Spirit’s baptism.1 While this is not entirely incorrect, for black leaders who founded and led Azusa, it was much more complicated and nuanced. For these black Christian leaders, they also left black Baptist and Methodist denominations in defense of the traditions of slave religion with its oral music traditions, ecstatic praise practices, and African diasporic-centered cosmologies and rituals. However, whites and many educated blacks viewed slave religious practices as antiquated and primitive, tainted by the sins of slavery and marked by pagan retentions from Africa.2 Longing to appear respectable to white Christians, many black educated Christians felt that slave religion had run its course.

However, some of the children and grandchildren of the enslaved felt deeply enough about slave religious practices to defend it on theological grounds. Historian of Pentecostal studies Cecil Robeck and political theologian Estrelda Alexander note that persons such as William Seymour (the founding pastor of the Azusa mission) certainly can be seen as deeply shaped by practices of slave religion and believed that these practices needed to be preserved.3 Likewise, Bishop C.H. Mason, founder of the largest US Pentecostal denomination, the Church of God in Christ, was deeply influenced by former slave-turnedholiness preacher Amanda Berry Smith, a woman whose brand of Christianity was imbued with slave religious practices and rituals.4 Slave religious practices such as tarrying (a descendent of the West African ring shout,

according to historian David Daniels) were rituals that people participated in as they experienced the outpouring of God’s spirit.5

When turning to the archival materials associated with Azusa (first-hand accounts in the Apostolic Newsletter and the numerous newspaper reports in the covering the revival) many American white Christian leaders are entirely incapable of reflecting upon and explaining what happens at Azusa, because they defined the “blackness” 6 of Azusa as “not Christian.” For example, often called the Father of US Pentecostalism, Charles Parham recounted that finding the disturbing sight of white people freely associating with blacks and Latinos in “crude negroisms” sickened him and he left the revival insisting that most of those claiming the Holy Spirit Baptism were subject to no more than “animal Spiritism.” 7

The way that Parham relegated such ecstatic behavior to the realm of the animal or as animal spiritism underscores how the animal and blackness were seen as constitutive categories in white Christian theological thought. For white leaders like Parham, Azusa is excessive. It is wild, uncouth, and demonic – with the demonic being indexed to blackness. Parham locates Azusa’s religiosity outside of Christian Protestantism altogether. Yet, people at Azusa believed that this excess was the work of the Spirit.

To white ministers like Parham, these slave religious practices at Azusa signaled a demonic religiosity in terms of belief and practice. For instance, Oneness denominations emerge out of Azusa such as the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World (PAW) which break from Trinitarian formulations of God that have marked both white and black Christian

1 James Goff interprets Azusa as part of a broader Pentecostal movement which was doctrinally marked by debates over sanctification and the doctrine of initial evidence (being speaking in tongues). For Goff, Seymour’s Azusa Revival stands in the tradition of Parham’s Pentecostal revivals in Topeka, Kansas and Houston, Texas. For Goff, Pentecostals leave Baptist and Methodist traditions because of this doctrinal difference around xenolalia or speaking in tongues (languages). See Goff, Fields White unto Harvest, especially the Introduction where he offers an interpretation of the historical development of North American Pentecostalism.

2 See Barbara Savage, Your Spirits Walk Beside Us: The Politics of Black Religion (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2008), pages 10–23. I also see Azusa Reimagined, pages 48–54.

3 Cecil Robeck, The Azusa Street Mission and Revival: The Birth of the Global Pentecostal Movement (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishing, 2006), 22-23.

4 Robeck, The Azusa Street Mission and Revival, 37–39.

5 Robeck, The Azusa Street Mission and Revival, 39. Historian of World Christianity David Daniels explores how tarrying is a descendent of the ring shout, a West African religious ritual that made its way to North American shores during the transatlantic slave trade. Daniels argues that the denouncement of the ring shout as heathenish and theologically unsound precipitated its declining use and eventually relocated to the religious underground. The emergence of tarrying as a black Christian practice drew from the ring shout in which the structure of the ring shout was transposed into tarrying. Daniels does note that tarrying as a prayer form is more than a practice reflecting African heritage. However, the way that the previously enslaved performed tarrying was unique to the black religious community in that this prayer form served as a vehicle for the ecstatic. See Daniels article, “Until the Power of the Lord Comes Down,” in Contemporary Spiritualities: Social and Religious Contexts, eds. Clive Erricker and Jane Erricker (New York: Continuum Publishing, 2001), pgs. 176–179.

6 This manuscript asks: What is “blackness”? Black religious scholars and theologians have debated this idea. Debates over the problem of ontological blackness (and if ideas of postmodern blackness aptly get at blackness as both a construction of white (anitblack) supremacy as well as subversive grounds for resistance and human fulfillment among black people) continue. While I do agree with black philosophers of religion like Victor Anderson and William Hart on the problem of ontological blackness(or blackness as essence), I take my cue from scholars in critical black studies who think of (anti)blackness as that which is grounded in and yet exceeds social death. Black feminists such as Sylvia Wynter, Zakiyyah Jackson, Saidiya Hartman, and Katherine McKittrick foreground reading strategies and critical practices that allows one to theorize blackness (and the black maternal) as that which might resist and exceed antiblack representation in, under, and despite black death. For instance, how does black feminist Katherine McKittrick’s usage of mathematics and physics metaphors help us understand blackness as something grounded in but not necessarily reducible to the Western metaphysical and politico-ontological terms of antiblackness, blackness as something marked by opacity, paradox, indeterminacy, and incalculability? The point here is that blackness does bear a direct relationship to antiblackness and social death but is not consumed or exhausted by such systems as witnessed in black communities’ practices of defiance, care, and joy

7 Cited in Estrelda Alexander, Black Fire: One Hundred Years of African-American Pentecostalism (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic Publishing, 2011), 28–29. The performative enactment of blackness through slave religious practices, and the ecstatic encounters among black, white, Mexican, Chinese, African, and other diverse bodies created a crisis of doctrinal meaning for many white Christian leaders.

orthodoxy in the US (over 2 million blacks in PAW today).8 At Azusa, even new doctrinal commitments are emerging and being forged, affirming and yet sometimes imploding dominant Christian doctrinal categories altogether such as the Trinity. This is the complexity of Azusa: it doesn’t neatly follow what has come before in terms of doctrine and orthodoxy. This movement operates within, yet against and beyond dominant Christian orthodoxy and orthopraxy.

I now have turned my attention to thinking about how the heterodox shape of Azusa’s religious life (that I have just discussed) enables a reimagining of theology and how the Spirit is central to this theological enterprise (and Christian faith more broadly). At Azusa, experiences of the Spirit ignited an encounter with God in sometimes predictable but often highly unpredictable and surprisingly unorthodox ways within a world marked by violence and goodness, chaos and care. In my current working manuscript, tentatively entitled, Thinking the Fragment: A Theology of Spirit, I argue for a materialist yet apophatic view of Spirit

that can respond to the precarious existential and political conditions that mark our worlds right now.9 While I cannot lay out the argument of this working project, I want to meditate on one aspect of this project and my hopes for theology here at Princeton, in the larger national and international guilds of theology and black religion, and in churches. I want to focus on a central category I employ in this text in rethinking the theological enterprise. I turn to the idea of the fragment and its implications for doing a theology (of Spirit).

THINKING THE FRAGMENT IN THEOLOGY

When I speak of the fragment, I do not mean it in a negative sense, as a kind of ruin, disintegration, or loss. Instead, my idea of the fragment is about how repressed images and ideas confront us in ways that disrupt a larger picture or system that claims coherence and comprehension. While the fragment disrupts, it is

8 For more on the emergence of Oneness Pentecostalism from Azusa, see Estrelda Alexander, Black Fire: One Hundred Years of African American Pentecostalism (City: IVP Academic Publishing, 2011), especially pages 206–248. In these pages, she charts the rise and development of Black Oneness Pentecostalism, drawing the reader’s attention to the controversial doctrinal and social implications of this theological perspective and movement.

9 On May 1–3, 2023, I delivered the Sprunt Lectures, a 4-part lecture series entitled, “Undomesticated Faith: A Decolonial Theology of Spirit.” In these four lectures, I advance a materialist yet apophatic account of the Spirit. While in no way an exhaustive account of my unfolding argument in my working manuscript, these lectures offer the contours of this view of Spirit and draws ethical implications. I want to note that in these lectures, I did not develop a notion of “the fragment” although this idea of the fragment is subtly present in the argument. This address attempts to clarify my own sense of theological epistemology (through the idea of the fragment) before cultivating my account of Spirit.

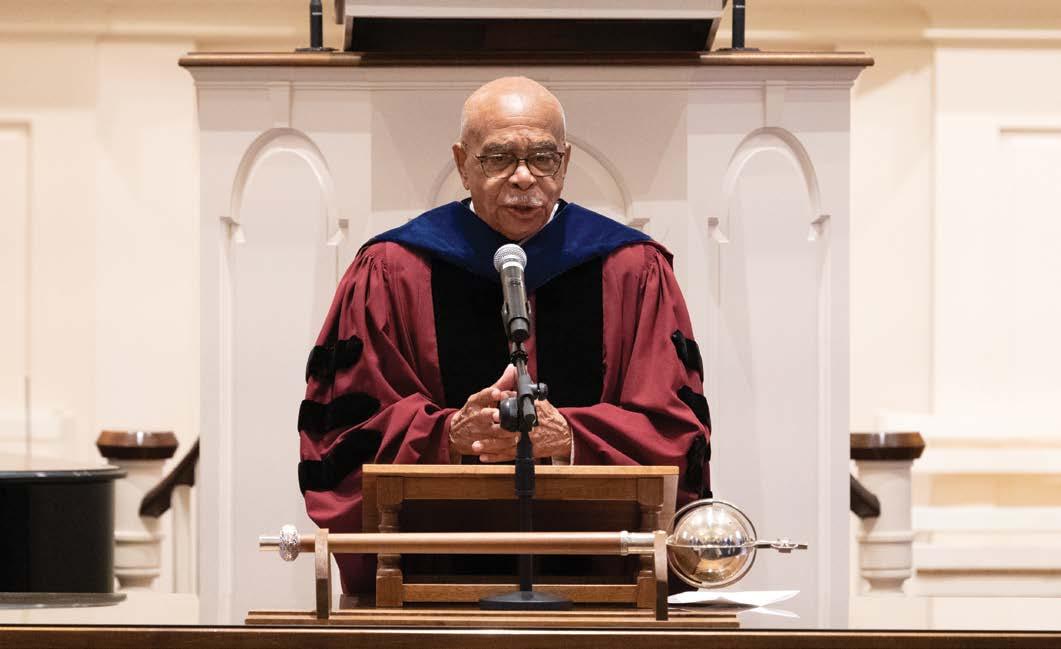

Dr. Keri Day, Professor of Constructive Theology and African American Religion and Elmer G. Homrighausen Chair

not necessarily emancipatory, but it is linked to seeing something new, demonstrating that our view is partial and incomplete.10

Thinking the fragment in theology then is fundamentally about acknowledging that although theology attempts to offer coherent, comprehensive explanations of divine reality, our knowledge of God’s manifestations in the world is itself incomplete, partial, fragmentary, and open-ended. A fragmentary idea of theology then resists any totalizing idea that we can know God and the worlds we inhabit with such absolute certainty that we can make demands of others as if speaking for God. While I work within the context of Christian traditions11, I am nevertheless suspicious of the historic Christian tendency to take the subjective and local and make it objective and universal. Theological discourse is a human activity – it is an interpretation of God’s activity in the world, not divine speech itself. And yes, theology in large part has taken its cue from the history of doctrines, creeds, and practices.

But even this doctrinal and creedal production employs words and language, tools of finitude, through which to describe that which is ultimately infinite. As a result, the apophatic dimensions of divine life must be held in tension with every word we speak about God, acknowledging that Divine life is always known and revealed as mystery.

The partial view I am speaking of is not a complete departure from the historical ideas of Christian faith. Just consider the fragmentary expression at the heart of Christian faith, the Incarnation. Even as Christians employ philosophical and theological arguments to explain the Incarnation, our arguments (our creedal words) break up and dissolve as we confront its paradoxical realities. The Incarnation simply evades intellectual capture. Also consider Martin Luther himself whose notion of the hidden God retains a fragmentary character with respect to theological knowledge. For Luther, God discloses God’s own self through contradictions – life through death, wisdom through folly, strength through weakness.12

10 I am indebted to David Tracy and Ruben Rosario Rodriguez who flesh out their ideas of the fragment with respect to theological knowledge. In David Tracy, Fragments: The Existential Situation of our Time (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020) and Ruben Rosario Rodriguez, Theological Fragments: Confessing What We Know and Cannot Know about an Infinite God (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2023). Hanna Reichel’s After Method: Queer Grace, Conceptual Design, and the Possibility of Doing Theology (City: Westminster John Knox Press, 2023) also helps me think the fragment through their desire to reorient theologians towards theological realism. Reichel advances a theological space in which “God and the real lives of people exceed and resist our idealizing constructions of theology and our methodological control” (116).

11 In relating Christian tradition to Christian revelation, I take my cue from H. Richard Niebuhr in his book, The Meaning of Revelation. For Niebuhr, revelation is not timeless, universal principles unmoored from the histories and cultures they emerge from. Instead, revelation is a confessional, storied enterprise that involves what a particular community has said about a living God they have experienced. I am compelled by Niebuhr’s sincere grappling with historical relativism in relation to ideas of revelation, challenging the universalizing, abstract impulse in theology. I also think discourses on revelation and its historical transmission must be thought critically within ongoing contexts of structural violence, unequal power relations, and problems of difference. Please see David Bentley Hart, Tradition and Apocalypse (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic Publishing, 2022) for a fascinating and important interrogation of any claim to a coherent “Christian tradition” over time, place, and space. He spends time foregrounding grids of institutional power and violence in the shaping of Christian tradition, which often silenced the diversity and polyphony inherent in Christian traditioning over the centuries.

12 Martin Luther focuses on the affective experience of the living God rather than God as an abstract, metaphysical idea. Luther expounds on this experience of God by distinguishing

Dr. Peter J. Paris, the inaugural holder of the Elmer G. Homrighausen Chair carried the mace for Dr. Day’s inauguration and installation ceremony.

Or perhaps we might even turn to scripture and see the fragmentary shape of biblical witness. This fragmentary shape in Christian terms could read as a centering or “privileging of Mark’s fragmentary, discontinuous, nonconclusive, apocalyptic gospel whose closure is unclear.”13 There is a consensus among New Testament scholars that in the last chapter of Mark, verses 9–20 were added much later by scribes to better align Mark with the theological worldview presented in the other gospels – the resolution of the risen Christ followed by a commissioning of the disciples by Christ. The earliest manuscripts of Mark only go up to verse 8, which leaves the story inconclusive and fragmentary, as Mark’s gospel abruptly ends by capturing the women trembling and fleeing from an empty tomb. Even the ancient grammars of Christian faith gesture towards this fragmentary view.

I want to think about the theological enterprise as being marked by incompletion – that we have (churches have) a partial view of what God has done and is doing – and so might anticipate, in surprising, unpredictable, and even unorthodox ways how the Spirit will be present with us in the personal and political dimensions of our lives. In part, this partial view allows us to ask how God is present, how the Spirit is active, in places, people, and landscapes that we deem unworthy and even undesirable. Doing theology with an eye towards our incomplete and partial view is to not just address the epistemic forms, methods and contents when doing theology but to say something fundamentally about the one doing theology – the theologian.

The disposition and commitments of the theologian matter. Drawing on Jewish critical theorist Benjamin’s metaphor

of the problem of the “historian as chronicler”, I trouble the idea of the theologian as merely a “chronicler” of past doctrines and received dogmas. The chronicler’s role is often the easy, coherent narration of received Christian doctrines, dogmas, and practices from a presumed objective point of view. The task then of the chronicler is the preservation and protection of “the tradition” by any means necessary. Yet, the chronicler is unaware (or doesn’t care) about those “buried underneath” certain doctrinal narratives and “on whose backs” certain doctrines, dogmas and practices have been forged.14 Consider the long history of coloniality and antiblackness out of which European Christian truth is rendered legible against the backdrop of the superstitious heathen of Africa, legitimating and justifying colonization on the grounds of saving and civilizing the heathen. One might argue that this is just a matter of practice (doctrine misapplied). However, an even harder truth that Christians must wrestle with is the problem of Christian supremacy through the centuries that has been constructed through doctrine and its ontotheological terms (to use Sylvia Wynter words) that situated the nonChristian, non-European other as an enemy to Christ, justifying the organized killing, exploiting of resources, expropriating of lands, and colonizing of such people, on doctrinal grounds. In my work, I explore the legacies of antiblackness in particular and coloniality more broadly in Christian theology and how such legacies complicate any straightforward interpretation of doctrinal inheritances, as these inheritances are shaped by systems of domination, arbitrary exercises of power, and gratuitous violence.15

continued on page 15

between Deus absconditus in his hidden majesty and God as Deus revelatus suffering on the cross. Luther suggests that sinners experience the hidden God as a terrifying presence causing them to suffer. However, through faith, sinners can recognize that this wrathful God is one with the God of love and mercy revealed in Christ. Based on this paradoxical idea of God, Luther admonishes Christians to seek refuge “in God against God.” Some scholars have noted the way Luther “thinks” theology: through paradox and contradiction. Refer to a great interpreter of Luther’s idea, Sasja Emilie Mathiasen Stopa, “Seeking Refuge in God Against God: The Hidden God in Lutheran Theology and the Postmodern Weakening of God,” in Open Theology 2018, 4: 658-674.

13 David Tracy, Fragments: The Existential Situation of our Time (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020), 9. Tracy doesn’t expound on this claim, but I interpret Tracy’s claim to be about the controversial ending of Mark. As I discussed in this address, there is a consensus among New Testament scholars that in the last chapter of Mark, verses 9-20 were added much later by scribes to offer a happier ending, more in line with the theological worldview presented in the other gospels – the resolution of the risen Christ followed by a commissioning of the disciples by Christ. The earliest manuscripts of Mark only go up to verse 8, which leaves the story inconclusive and fragmentary, as it ends by capturing the women trembling and fleeing from an empty tomb. For more on this, please see Kim Huat Tan, Mark: A New Covenant Commentary (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2015), 221-223; and Mark L. Strauss, Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2014), 727-737. One might ask these questions: Why does Mark end with terror and death? Why does it seem Mark knows nothing about Jesus’s resurrected or resuscitated body? Why did Mark include women, who were less religiously credible than men in ancient society, to just have them flee the empty tomb? Why doesn’t he provide a last sighting of the resurrected Jesus if he knew of Jesus’s resurrection? I wonder whether this abrupt ending to Mark might be interpreted as affirming the fragmentary nature of our knowledge about God, even in the gospel stories. And despite this partial view, might Mark’s abrupt ending be an open-ended invitation for us to discern and interpret, in a multiplicity of ways, the life of Jesus and the work of the Spirit within, under and despite state violence and death?

14 In my earlier work, I was drawn to Frankfurt school critical theorist and Jewish writer Walter Benjamin in critiquing the myth of progress and its secular eschatology associated with neoliberal capitalism. In my book Religious Resistance to Neoliberalism: Black Feminist and Womanist Perspectives, I interrogated why Benjamin’s fragmented, imagistic notion of history and apocalyptic sensibilities were resources for theologically challenging the moral and existential problems associated with global capitalism. In part, Benjamin was preoccupied with the problem of how history and knowledge tended to align with the produced meanings of the victors. This is not a new insight. Scholars across a range of interdisciplinary discourses have theorized this, although in different ways, from historical theological thinkers such as Kierkegaard and Luther to contemporary theorists and theologians such as bell hooks, Tamura Lomax, Emilie Townes, and Saidiya Haartman – they all interrogate the epistemic problems of knowledge and history with respect to relations of interest, power, and domination. For me, the theologian as chronicler is about an uncritical view of doctrines, dogmas, and practices in light of histories of state violence often created and sustained by a hegemonic Christian account of knowledge and history.

15 As stated, in my working manuscript Thinking the Fragment: A Theology of Spirit, I explore the legacies of antiblackness in particular and coloniality more broadly in Christian theology and how such legacies complicate any straightforward interpretation of doctrinal inheritances, as these inheritances are shaped by contexts of domination, arbitrary exercises of power, and gratuitous violence. I seek to bring black theological and religious scholars in conversation with scholars situated in black studies. Some scholars I engage include: Willie Jennings, Kathryn Lum, Sylvia Wynter, Zakiyyah Jackson, Jared Sexton, and J. Kameron Carter.

Brit Whittle possessed a lifelong passion for acting but now feels an equally fervent call to ministry.

For almost 20 years, this New York-based thespian has carved out a successful career in a very fickle industry—on stage, film, and television. However, through it all, he has felt an irresistible pull toward God and faith: one that intersected with his love of acting and began at a very young age for the Georgia native in church theatre productions.

Today, Brit is studying full-time ministry at Princeton Theological Seminary and feels he is finally where he belongs.

“My first experiences in the arts were at churches,” he recalled. “Vacation Bible School and acting out scenes from the Bible lit me up and inspired me, as well as singing in church.” Brit’s family moved around quite a bit during his childhood, and only in church did he feel truly rooted.

Brit’s mother gravitated to the churches with the best music programs, he noted, adding that in middle school

Brit and his family at his daughter’s baptism

and high school, music ministers began mounting productions based on bible stories. From there, he was hooked.

“That’s how I got my first experience being on stage and it was thrilling. At the same time, I started actually listening to the sermons in church. I had favorite preachers that I liked hearing more than others, and around age 16, I wondered if I could be a preacher but was discouraged.”

In college, Brit received an offer to become a youth minister. “I remember thinking, ‘No, I want another life.’ A week later, I was cast in the chorus of Guys and Dolls in the school theater department. The lead, who was a professional actor, dropped out for a better gig, and I was thrown into the lead role. The rest is history.”

“It’s hard to describe the feeling of acting,” Brit explained. “It’s living truthfully under imaginary circumstances in order to tell a story. The back and forth with actors and audience can feel like a spiritual connection when the show is going well. It reminded me of singing in church and the connections we all feel when singing together on Sunday mornings.”

Brit received his Bachelor of Science in Political Science from Georgia College & State University and a Master of Fine Arts in Acting from the Florida State University/Asolo Conservatory for Actor Training.

The phrase “struggling actor” resonates deeply with Brit, as he knows the frustration associated with his craft and the commitment necessary to sustain oneself in the midst of persistent disappointment.

“Making your way in the entertainment industry when you don’t have connections can get discouraging over the long haul,” he stressed. However, in those moments, he said God always placed someone in his path to encourage and motivate him.

Possessing an impressive resume that includes appearances on popular shows such as Law and Order: SVU, The Americans, Person of Interest, and Bull, Brit’s first love is the stage. “You get to tell an entire story in front of a live audience, and the feedback is immediate.

“I also love the craft of studying a script with an ensemble, putting it on its feet, and then realizing it enough to put it before an audience. When it’s done, you feel sad, but it’s also cathartic to bring the show to a close and move on to the next thing.”

Faith remained integral to Brit’s life, and he identifies it as the greatest gift he ever received from his parents and grandparents. His mother’s relationship with God was particularly meaningful. “She related to God like you would a family member. So, when she prayed or talked about God or Jesus, there was an intimacy to it—an intimacy that never left me.”

God was always a real presence in his life—and it was a relationship that, outside the confines of family, he always felt discouraged to express. “It made me deeply lonely. I was in my room one day and started praying. All these emotions welled up in me. All I could say to God was, ‘I miss you. I miss you being in my life.’”

Ironically, as Brit began succeeding as an actor, he felt an even stronger pull toward faith and God. He understood that living in New York City and working in this profession would require grounding and sought out churches he could call home. Over time, the pull toward full-time ministry became intense.

Then, during the COVID-19 pandemic, he experienced a jarring moment that made him question his life’s purpose.

“My wife Nissa and I were living in Astoria, NY. We had an 18-month-old at the time and were six blocks from one of the worst-hit hospitals. In that first month, we didn’t know what this virus was, how it spread, and if we had it. Every afternoon around 4:30 or 5:00 p.m., our whole neighborhood would open their windows and applaud

Brit and his daughters

the health care workers. We joined in every time with our little girl. It was a balm in the middle of a crazy time. It had a profound effect on us and got me thinking again, ‘Is being an actor the best use of my talents?’”

Brit and his family moved to New Jersey and found a home in their local parish that welcomed them with open arms. “Most importantly, we felt spiritually fed. I had not had that kind of formation in many years.” There, Brit’s parish formed a committee to help discern his true vocation. “I spent 10 months doing that, and by the end of that process, I was sure I wanted to move towards ministry full-time.”

Energized by this realization, Brit began investigating seminaries, and while he had a tangential knowledge of Princeton, it wasn’t until he and his family spent a week here that he knew this was where he wanted to study.

“We fell in love with the town of Princeton,” he recalled. I visited the campus twice with my family and felt so embraced by the faculty and the students that it was pretty hard to say no.”

Brit was confirmed in the Episcopal Church and nominated for postulancy within the Newark Diocese, so his first thought was attending Princeton might not be appropriate. “God opens doors that don’t make sense at first but feel right. That was Princeton Theological Seminary for our family.”

“The amazing part is we moved into campus housing almost one year to the date we first visited Princeton the previous summer. My wife and I call those ‘God winks.’”

Brit is a member of the inaugural cohort of the President’s Fellows Program. “Being a President’s Fellow has been a gift for me. To interact with the President’s office, the Board of Trustees, alumni, and donors who have made an investment in this incredible institution has taught me so much.”

He added, “The incredible diversity of leadership at Princeton has such a vested interest in our experience here as students. They want to know our unique story, our journey of faith, and what we feel called to do both while we are studying at Princeton Theological Seminary and afterward.”

“ The faculty, facilities, my fellow students, are all a gift. This new community is bringing out the best in me and challenging me in profound ways. I don’t think you can help but grow within the wonderful, diverse, and spiritual culture that has been fostered. It’s a privilege to call myself a student here.”

While Brit is committed to working in ministry full-time, he does miss acting and wonders aloud if there might be a way to combine the two down the road. “Some of my professors have prodded me on this same question. It makes me wonder if God is behind all this prodding and missing the acting world. Maybe there is a future where both coincide and work together. That would be a dream, but my first commitment is to God in this process and to be available to do whatever work God calls me to do.”

When Brit reflects on his lifelong journey of faith, he thinks of the Hebrew word Hesed, which literally translates to a steadfast love and loyalty that inspires compassionate and merciful behavior. “It is the steadfast love of God and doing for me what I didn’t always know how to do for myself.”

He stressed, “I see my 29-year acting career as spiritual formation now. Being in Seminary at this point in my life feels so natural as if God is saying, ‘I created you to be this, and all that led up to this moment.’”

Brit playing coach Wallace on the Starz show Ghost: PowerBook II

Brit and his family

As one can see, the theologian as chronicler hasn’t contended, to use Benjamin’s words, that “there is no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is never free of barbarism, so barbarism taints the manner in which it was transmitted from one hand to another.”16 The problem of violence even in doctrinal history cannot be left alone, as it also bears the imprint of barbarism that comes with theology’s mediation and transmission through culture, in this case, much of Western imperial culture. I want to trouble theologians who often use the hand and voice of the chronicler without sensitivity to

traditions of the vulnerable and repressed. And the hand of the chronicler is not just present with those working out of white western orthodox materials; the voice of the chronicler is also present among those who perceive themselves as working in liberationist or feminist or queer traditions who do not consider how their epistemic and theological positions may violently repress.

I think that the interlocutors I engage attempt to think in fragmentary ways about theological knowledge by resisting the voice of the chronicler and by foregrounding fragments or forgotten memories of repressed traditions to see more clearly what has been silenced and written out.17 For instance, for Jewish writer Walter Benjamin, the

16 Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” in Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s ‘On the Concept of History’, Trans. Chris Turner, ed. Michael Lowy (New York: Verso, 2005), 47. Benjamin further states, “The tradition of the oppressed teaches us that the ‘state of the emergency’ in which we live is not the exception but the rule. We must attain to a conception of history that is in keeping with this insight”, page 57.

17 Benjamin introduces the historical materialist as a counterpoint to the chronicler, foregrounding another way of approaching history and the past, with an eye toward naming logics of progress as catastrophic as one faces the ongoing impending death of the vulnerable, oppressed and forgotten. Motivated by the oppression of the vulnerable and the malformed ambitions of the chronicler’s idea of universal history, the historical materialist disciplines herself “to foster an experience with the past that is not distracted by the ambitions of history and the eternal narrative of the chronicler. The materialist cannot look on history as anything other than a constellation of dangers which begs to be redeemed. As a result, the materialist responds in kind by searching for those moments which break through narrativity. So the materialist goes to a historical subject and brackets the historical subject from the meanings ascribed to it by the dominant narrative and in this way, generates a revolutionary chance in the struggle for a repressed past. Moreover, for Benjamin, the historical materialist doesn’t seek to offer a representation of history but a re-constellation of historical images to show the way images from a past epoch develop over time with respect to power, domination, and the cries of the hopeless – and how these past images “relate to images that proliferate for us in every present moment.” Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” see Theses XVI-XVIII.

Let me provide an example of how the historical materialist might engage historical moments. In Azusa Reimagined, I foreground the image of the World Fairs at the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth centuries. Within dominant narratives on scientific, market, and technological progress, world fairs have been seen as reflecting the growing innovation and progress that would mark an increasingly wealthy nation. What I sought to do was offer a set of images from the Chicago World Fair and the Philadelphia World Fair that throw into question this dominant narrative. At these world fairs, one would encounter the primitive handicrafts and artifacts of Native American tribes in a way that gestured towards these communities being technologically backward, savage, chaotic, and homely – in need of civilization. One would also encounter Africans from the kingdom of Dahomeyan, arranged in a kind of human zoo, doing war dances, which allowed guests to infer that these African’s participation in war dances reflected their bestial and morally reprobate nature. These exhibitions allowed white ethnologists and US political and economic leaders to justify practices of colonialism and exploitation. Because such communities were barbaric, Christian Anglo-Saxon nations were needed to bring civilization and moral light to these lands and people. These barbaric images from world fairs legitimated the evolutionary idea of progress in which humanity could be seen moving from more primitive ways of being as embodied in the African and the Asian to more civilized modes of being, most illustrative of Europe and its AngloSaxon identity that marked America.

However, when exposing how such World fairs were part of larger religio-economic narratives and structures steeped in antiblackness and other structural racisms, it allows such images and their meanings to break through and explode the racist Christian narrative associated with the world fairs at the start of the 20th century. When one experiences these historical images within a persisting history (past is present) of anti-Black violence and death revealed in contemporary images of racist police violence, black maternal mortality, poor educational systems of brown and black children and more, this re-constellation of images (images of past and present violence) “stands still” or “stands up” to speak of racist exploitation and antiblack degradation, not progress.

Dr. Marla F. Frederick, Dean of Harvard Divinity School

Keri Day, continued from page 11

marginal fragment or forgotten and repressed memories of the suffering (or the victims of history), is privileged. Writing out of the death-dealing urgency of Nazism as well as the colonial implications of Israel’s secular Zionism that he would eventually distance himself from,18 Benjamin demanded that the suffering of those under unrelenting violence should be privileged and heard by foregrounding the fragmentary nature of history. History does not move in the linear direction of progress but catastrophe, as Benjamin gazes upon the “piles of bodies” instigated by modernity and its colonial projects. What is most interesting is how he employs the Kabbalistic and mystical traditions in Judaism to intervene into ambitious narratives that associate modern history (and its scientific, market, and technological innovations) with unadulterated progress.19 I infer that Benjamin believes that apocalyptic theological and religious resources can “unveil” and help us discern the presence of catastrophe rather than progress in the systems of which we are part. But this catastrophe is not totalizing. It is through foregrounding the marginal fragment or repressed memories of those dead and alive within such catastrophe that signs of hope emerge, not a naive optimism within the configurations of the liberal or totalitarian state but a sign of hope seen within repressed communities’ religious orientations that mediate experiences of care, joy, and possibility not consumed by the catastrophic configurations of state violence.20

I also engage womanist theologian Delores Williams’ work, which privileges the fragments or repressed memories of black women. In Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk, she rightly insists that liberation theologians did not wrestle with the fragmentary nature

of the biblical witness, nor did they interrogate how their theological ideas (God as Liberator) ignored or dismissed vulnerable groups that sat within black communities themselves such as disadvantaged black women. Williams centering of the Hagar narrative in Genesis 16 and 21 is not solely to ask why God does not liberate Hagar, troubling a liberationist scholar’s taken for granted assumptions on the nature or essence of God. She also invites the reader to look closely at the memory of Hagar as a fragment, as a repressed complicated memory that unsettles and troubles the dominant coherent view of the Christian God in scripture. Williams notes that this Diety, El (El Roi that Hagar cries out to in Genesis and also names when facing death with her child Ishmael in the wilderness), is also familiar as the highest God of the Canaanites. This God of these Genesis texts is a God associated with and under the influence of both Hebrew and Egyptian religious traditions – an insight several biblical scholars have uncovered.21

This fragment not only scrambles and complicates Christian ideas of God that colonize God to an exclusively Christian worldview but also allows a rediscovery of what is possible in this repressed memory – perhaps a dangerous memory for those who reject any possibility of interreligious and paradoxical understandings of God. I infer from Williams that this fragment allows us to see how our theological views of God are partial and incomplete, often shaped by forces that silence particular memories in the name of orthodoxy (right belief), which also forecloses how repressed forms might open to something more.22 The fragment is not just about the critique of a closed system of meaning that excludes but the fragment is also about a re-emergence and discovery of the intense presence

18 Gershom Scholem writes more about Benjamin’s distancing himself from the state of Israel. See Scholem’s memoir, Walter Benjamin: The Story of Friendship (New York: NYRB Classics, 2003). 19 In this manuscript, I write about Benajmin’s engagement with Paul Klee’s painting. Benjamin writes about this painting: “In an effort to reconstruct the catastrophic chain of events that has been hurled at his feet, the Angel of history has opened his wings so as to move toward and fix that which has been. His desire is to rebuild; yet this unfolding creates a drag against the stormy winds blowing from Paradise. The storm has caught the Angel up in an unavoidable gust, driving him irresistibly into the future.” Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” in Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s ‘On the Concept of History’, Trans. Chris Turner, ed. Michael Lowy (New York: Verso, 2005), 60-62. Reflecting on Klee’s painting and the Kabbalistic Jewish ideas it might represent about divine redemption of the historical catastrophe called progress, Benjamin uses this image to arrest the idea of any easy redemption of historical forces of violence and death. Benjamin wants to throw into question any agency, divine or human, that can repair catastrophes from the past and even points to the “pile of bodies” that witness to such catastrophe. Writing out of the holocaust and his own fugitive status of being on the run as a Jew, he most certainly is reflecting on the absurdities of his own historical moment and the absence of redemption, a theme that finds its fulfillment through Benjamin’s own suicide once he realizes he will be captured by Nazi soldiers. Benjamin presents a struggle for a repressed past that comes alive through how we experience the past with respect to the present – how the past is illuminated, for example, by ongoing systems of violence and death.

20 In Azusa Reimagined, I attempt to think of Azusa’s apocalyptic agency as the rediscovery of these intense religious forms which enable an affirmation of existence not dependent on the catastrophic configurations of the state and its political arrangements. See Azusa Reimagined, chapter 5. I want to move towards an idea that even as forms of state violence haunt religious experiences and their aspirations of hope and care, these religious experiences also haunt and disrupt religious and political configurations of state violence.

21 Delores Williams, Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1993), 23–26. Williams cites the work of Helmer Ringgren, Roland de Vaux, and Joseph Kaster in discussing the Canaanite God Hagar calls upon (a God present in both Egyptian and Hebrew traditions). See Ringgren, Israelite Religion, trans. Davie E. Green (Philadelphia” Fortress Press, 1966), pgs. 21–22; Roland de Vaux, Ancient Israel: Its Life and Institutions, trans. John McHugh (London: Darton, Longman & Todd, 1961), pgs. 8,9, 45–85; and Joseph Kaster, trans. and ed., Wings of the Falcon: Life and Thought of Ancient Egypt (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1968), pages 50–68.

22 For me, this acknowledgement is not about saying the God of Hagar is then not the God of Judaic categories. Rather, I wonder how this observation allows us to see our own ideas of God as a partial view, taming our inclinations to feel our tradition has an absolute monopoly on God.

23 In the address, I could not discuss how Charles Long is central to this project on the idea of the fragment. Charles Long, while not a theological thinker but a historian of religion, helps me think through the fragment with respect to theology. Long asks scholars of religion to deepen their understandings of what shapes different religious worlds or “those forms of meaning which lie between experience and category.” Significations: Signs, Symbols, and Images in the Interpretation of Religion (Aurora, CO: The Davies Group Publishers, 1999), 9. Long reminds scholars that there are some religious forms that are fundamentally irreducible to categories themselves. I infer from Long that some religious and/or spiritual expressions invoke an attentiveness to the unexpected, to excess, to surprise beyond the systematization of ideas and their meanings, a systematicity that often accompanies doctrine. Such religious forms point to other ways of knowing beyond dominant doctrinal categories and dogmas. In this project, speaking in tongues and forms of conjuring were black religious experiences at Azusa that escaped dogmatic positions and challenged dominant “Christian” ways of knowing but also allowed for something unexpected and life-giving within this black Pentecostal religious world.

of divine life in repressed religious experiences deemed and labeled improper, undesirable, and even demonic.23 Most importantly, such centering of repressed fragments and its forms of knowing allows for a tradition’s re-discovery of what is possible within their own religious worlds, enabling this very tradition to stay open to eschatological futures it does not fully know. It allows a tradition to stay open to the unexpected movements of the Spirit.24

Thinking the fragment invites those who engage the theological enterprise to attune themselves to an epistemic humility, truly embracing the words of the author of I Corinthians 13:12 “that we now only see through a glass darkly.” The theologian sees in partial, incomplete ways. But this is the theologian’s strength, not her liability. And most importantly, the theologian gives serious attention to how repressed fragments (or repressed memories of the marginalized) might arrest hegemonic theological narratives and their fixed meanings to appreciate the ways Spirit is already moving in surprising and unanticipated ways.25

A FRAGMENT FROM AZUSA: CONJURING

On the back of your program, you see a picture of the founder of the Church of God in Christ. This picture hangs in many to most COGIC churches. Many scholars have been interested in Mason and what this picture represents, a debate that is quite uncomfortable even in COGIC. I want to treat this picture as a fragment from Azusa’s past, as Mason is deeply influenced by the conjuring culture of his religiosocial context, which includes the context of Azusa.26

In particular, the image you are looking at revolves around Mason’s life and ministry. Black religious scholars such as Yvonne Chireau and even COGIC scholar and Bishop Ithiel Clemmons write at length about Mason owning a collection of unusually formed objects including roots, branches, and vegetables that he consulted as “sources for spiritual revelations,” which revisited the black enslaved tradition of conjuring charms.27 As Chireau notes, “Mason would illustrate his sermons by referring to these [objects as] ‘earthly signs’ and ‘freaks of nature’, as he called them.”28 As C.G. Brown, a secretary of the Church of God in Christ in the early 20th century wrote, “When scriptural texts seem to fail and audiences seem to tire of the monotony of sermons…the Spirit directs Elder Mason’s mind to a sign. As he turns it [the natural object] over and from side to side, God’s mystery comes out of it.”29 Mason delivered “divine interpretations while meditating on mishappen tree limbs, stones, or the entrails of chickens.”30 Brown commented that “it appears that he is reading one of the recesses of the object from which he is preaching.”31

To those among Mason during this period, they would have easily discerned this as infusing Christian practice with conjuring culture seen on slave plantations and in early emancipated black communities. In Bishop Clemmons biography Bishop CH Mason and the Roots of the Church of God in Christ, he argues that Mason was “committed to preserving the African Spirit cosmology” and other “distinctive African cultural expressions” amid the daily experiences of racist assault.32 Yet, Chireau cautiously notes

24 I engage Benjamin and Williams, among other scholars, as they interrogate theology at the intersections of colonialism, antiblackness, and heteropatriarchy. Their fragmentary approach to knowledge about the divine and the world revolves around the “shattering of any totality system and the possibility of a generative discovery of the intense presence of the divine, of infinity, in religious forms, religious forms that are often repressed and silenced.” David Tracy, “African American Thought: The Discovery of Fragments,” in Black Faith and Public Talk: Critical Essays on James H. Cone’s Black Theology and Black Power, ed. Dwight Hopkins (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1999), 32. For these thinkers, shattering systems of totality is about how Christian religious language often was cultivated and preserved within a colonial context of domination, exercises of arbitrary power, and gratuitous violence. Having a fragmentary approach to knowledge, such as theological knowledge, acknowledges that certain traditions, interpreted as barbaric, demonic, and savage, are repressed traditions because they are seen as unsettling and unseating dominant, reigning colonial (and racist) theological forms of knowledge. Yet, thinking the fragment or foregrounding a fragmentary approach to theology is more than critique and exposure of hegemonic logics and regimes that suppress. It is also about the explosion of new, creative possibilities for religious existence.

25 One worry I have written about revolves around how Pentecostal scholars have attempted to fit religious experiences (like Azusa) into systematic methods as a way of disciplining and domesticating the radical strands of Pentecostal experiences that cannot be absorbed into dominant systematic methods. Over the last several decades, Pentecostal scholars like Douglas Jacobsen and Christopher Stephenson have formulated Pentecostal theology as a systematic theology in efforts to render it theologically legitimate to the field. In my estimation, this endeavor, in efforts to be more intelligible and palatable, often ended up silencing, domesticating, and disciplining the radical strands of early Pentecostalism such as the slave religious practices seen at the Azusa revival. To be generous with respect to this endeavor, it may be fair to characterize these systematic endeavors as being aimed at centering and demonstrating the value of Pentecostal contributions within the theological enterprise, even if articulated through systematics and exegesis. Many Pentecostal theologians worry about the charge that Pentecostal religiosity is sensory, emotive, and non-intellectual. But this charge is their strength. My argument seeks to reclaim Azusa precisely as an early Pentecostal form that challenges these kinds of epistemic assumptions in theology that theology is solely rational rather than oriented also toward affect, that theology is solely systematic rather than fragmentary in nature, never able to capture the whole. Never able to master the quest for coherency.

26 What have traditions of the oppressed communicated about Spirit? In my working manuscript, I turn to a few practices of the Spirit that might be considered fragments with respect to Azusa. When I say fragments of Azusa, these are practices at Azusa that not only unsettle dominant Christian doctrinal understandings about God but also disturb the theological sensibilities of Pentecostal people who engage these very practices. There is a certain theological uncomfortability that these practices engender. Yet, these practices are the site through which the Spirit mediates divine presence. These practices affirm the partial, incomplete, and fragmentary nature of knowledge about God. But these practices also affirm that the task of theology and Christian faith is not to own and master God as such; the task is for theology to facilitate worship and wonder. As we cannot fully comprehend or control God, so our concepts cannot.

27 Yvonne Chireau, Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Culture (Berkely: University of California Press, 2006), 111.

28 Chireau, Black Magic, 111.

29 CG Brown, C.H. Mason, A Man Greatly Used of God (Memphis, Tenn.: Church of God in Christ Publishing House, 1926), pgs. 12, 52–53. as cited in Chireau, Black Magic, 111.

30 Chireau, Black Magic, 111.

31 Chireau, Black Magic, 111.

32 Ithiel Clemmons, Bishop CH Mason and the Roots of the Church of God in Christ (Bakersfield, CA: Pneuma Life Publishing, 1996), 33–34, 78.

that Pentecostal healing practices designated as “African and magical – such as anointing the sick with oil, laying on of hands, and the commission of special cloths and handkerchiefs – are also found in the New Testament,” which certainly questions whether Mason’s practice of divining messages from natural objects was simply an extension of African-diasporic conjuring culture.33

Yet, I want to linger on the opacity, inconclusive and fragmentary nature of Mason’s religious practices with respect to bones, natural elements of the Earth, and even the entrails of animals. Divining messages from elements of the natural world was a slave religious practice. Even Seymour was born in Louisiana, where Catholicism and Voodoo dominated the religious life of the enslaved and former slaves. Many of the enslaved wedded these two traditions together, creating a variation known as “Hoodoo.”34 Enslaved culture also engaged in root work and conjuring as ways to invoke divine power, healing, safety, and flourishing.

When people saw Mason divining messages from natural objects such as roots, bones, vegetables, or the entrails of chickens, they would have heard conjure and hoodoo language in these practices.35 Again, for instance, Elder C.G. Brown described how “Elder Mason would calmly pick up a stick, shaped in the exact likeness of a snake in its growth, and demonstrate with such power that thousands of hearers are put in wonder.”36 This conjuring and hoodoo language in Mason’s practices were certainly controversial, even among elders and members in COGIC. Yet, Brown would affirm Mason’s Christian conjuring practices, saying COGIC members that protested “demonstrated shortsightedness and a lack of spiritual vision.”37 While one should turn to the self-understanding of Mason – he understood what he was doing as being led by the Holy Spirit, according to scripture, to divine Christian messages for the times – Mason’s ritual practices are nevertheless preserving the form and, at times, contents, of what was perceived as non-Christian conjuring culture, as this culture understood an encounter of divine mysteries through roots, the inside of animals, and from natural objects of the earth.

I want to linger with what COGIC secretary Brown says about Mason’s divining work: that through this religious

33 Chireau, Black Magic, 193.

practice, people are “put in wonder.” This fragment (of Mason) doesn’t open to conclusive answers but wonder, paradox, and incompletion – as the Spirit that moves through Mason’s ministry is not bound by orthodox rules (in terms of belief or practice). I argue that this fragment of Mason with respect to conjuring culture allows faith to be practiced as an open question on how the Spirit is moving, not beholden to a rigid dogmatic certainty that constraints and violently excludes.38 Moreover, this fragment offers the possibility of the rediscovery of the intense experience of divine presence in repressed and silenced black religious orientations – a rediscovery that may open to new theological questions and avenues of thought that might make room for wonder, care, awe, and even delight.

I don’t think this fragment provides an answer to either/ or questions such as: was Mason a Christian or a conjurer? Does this Christian conjuring practice of Mason radically remedy the ontotheological terms of Western orthodox theology? Is this form of black religious existence a superior way to “doctrinal” theology? I think these questions are fair but mistake what I am after. I am not after asserting another right way of encountering God or the Spirit. Instead, I desire to center this fragment to ask these kinds of questions: what does it teach us about the necessity of being tutored by paradox and uncertainty? How does the fragment cultivate hermeneutical patience in us when confronted by upheavals of confession and practice? How does the fragment help us reimagine the idea of Christian traditioning as something not simply beholden to a fixed past (in terms of meanings) but open to multiple futures marked by an eschatological horizon we do not yet know or see? Most importantly, this fragmentary way of approaching theology and religious experience helps repressed communities (re)discover wonder, awe, beauty, paradox and even delight in their own intense religious orientations within, under, and despite systems of violence and death.

CONCLUSION: PROSPECTS OF THEOLOGICAL ASSEMBLAGES

Thinking the fragment allows for surprising and unanticipated ways of doing theology, of living out Christian faith in a violent yet dynamic world.39 Thinking the fragment in theology is reimagining endless

34 Robeck, Azusa Street Mission and Revival, 22-23. Hoodoo was a “slave culture in which symbols, spells, incantations, sympathetic magic, and root work were a regular part of life”, pg. 23.

35 Chireau, Black Magic, 111.

36 Robeck, Azusa Street Mission and Revival, 38.

37 Robeck, Azusa Street Mission and Revival, 38.

38 This repressed fragment does not offer some nostalgic longing for a preferable past (e.g. longing for an Africanist past such as conjuring culture). This fragment offers an intense experience with a certain past black Pentecostal image that is able to break out and explode the dominant theological and doctrinal narrativity that explains early black Pentecostalism being solely about doctrines of holiness, sanctification, and tongues. This picture presents something else, an excess, that troubles and complicates some “pure idea” of Christian belief and practice. There is a fragmentary nature to our knowledge about black Pentecostal experience and its views and encounters with the Spirit, encounters that might trouble and complicate dominant theological and doctrinal narratives on the Spirit and how we come to experience the Spirit.

39 The fragment is a sign of theological possibility rooted in the past, but not a nostalgic past. Instead, this is a past open to the endless reconstitution of religious meanings as we experience anew the presence of the Spirit in the world. I am theoretically drawn to Walter Benjamin’s move away from essentialist, comprehensive, dogmatic narratives of history to

possibilities for practices of faith as the Spirit moves, especially places, people and landscapes that are violently repressed, deemed unworthy and undesirable. Through foregrounding the fragment in my current work, I am interested in imagistic and sonic ways of conceptualizing theology, particularly a theology of Spirit40, which may not open to a theological system per se but to a theological assemblage. While an assemblage might offer a sense of the whole, it does so by preserving room for tension, contradiction, and paradox – never demanding a coherence of the whole. I imagine that my theology of Spirit might move more toward a theological assemblage or theological collage that allows various theological tensions about God, the meanings of Jesus for today, the political, and so forth to offer a sense of the explosive, dynamic, apophatic

ways Spirit is ever present in our worlds marked by both structures of violence and practices of care.41

Finally, my hope for theology and black religion at Princeton and the broader guilds (as well as churches) is that we would cultivate practices of intellectual courage and moral imagination in, what is most certainly, dark times to many people in our political and social worlds right now. And in the meantime, embrace that we see through a glass darkly, which might animate our faith communities to not assume we possess the fullness of truth right now but to express a fidelity to eschatological futures rooted in a divine promise that violence and death will not have the last say in a new age to come.42

historical particularities that might resist being absorbed into some larger comprehensive narrativity, perhaps offering multiple meanings that create something new – something like a constellation of heterogenous theological ideas that speak together in a polyphonic way. For my project, this polyphony might conceptually be understood as heterodoxy. I want to advocate for generous heterodoxies that are fueled and funded by Spirit.

40 In foregrounding imagistic and sonic understandings of a theology of Spirit (as image and sound offer cosmic visions of life together with God and broader creation), I am more interested in the where and how of Spirit than the what and who. In part, the who and what often attempt to capture the nature and essence of God and the Spirit apart from the material world, often leading to highly speculative, ontological claims that over-privilege divine transcendence. In contrast, I privilege the “where” question with respect to Spirit through engaging materialist studies (black feminist, indigenous and new materialisms). As one may see, the where and how question with respect to Spirit is not simply a question of place or space but more deeply a question of theological epistemology with respect to divine revelation – how God reveals Godself and God’s activities in and through the material worlds we inhabit

41 Again, I turn to Reichel’s After Method and their notion of “cruising” as a kind of epistemic promiscuity, which allows one to employ theories, concepts, and ideas from a wide variety of discourses (even contesting discourses) in creative, provisional, and open-ended ways in the doing of theology (refer to Ch. 6). My idea of theological collage with respect to a theology of Spirit will engage this idea of cruising.

42 In this manuscript, I center apocalyptic gifts that the Spirit brings to disrupt, expose and destroy old orders of imperialism, violence, and death even as new modes of existence (ways of loving, caring, and being together) are inaugurated.

President Jonathan Lee Walton

When Amy Ehlin arrived on the campus of Princeton Theological Seminary 31 years ago, she never envisioned spending her entire career here, but it’s a decision she has never regretted. “I’ve had so many great opportunities to grow, both personally and professionally,” she recently explained.

Amy first came to Princeton Seminary in 1993 as Assistant Food Service Director for ARAMARK and was shortly promoted to Food Service Director. In 2006, realizing how much she loved working with the Seminary, she joined the staff here as the Conference Coordinator. Today, she serves as Senior Director of Auxiliary Services.

Amy oversees Hospitality and Event Services and the 56-guest-bedroom Erdman Center, a gathering space for conferences, retreats, and meetings that host thousands of guests annually for continuing education and hybrid learning opportunities.

She also plays an active role in planning Board of Trustees meetings that occur both on and off campus.

A graduate of Widener University with a bachelor’s degree in Hotel, Motel, and Restaurant Management, Amy envisioned herself working on a college campus.

“It’s always changing. New students are coming in. You’re always adapting to new trends. Challenges are always going to be there, and nothing’s ever going to remain the same.”

“It’s a stimulating environment where I have to constantly adapt, and it allows me to grow and learn.”

Amy has worked under four Princeton Seminary presidents. She has watched the campus undergo extensive renovations and new construction. She has witnessed a diverse array of students follow their dream of serving God in the most profound way. Her job has been to create the most comfortable, conducive, and healthy environment for that sacred work, and she relishes it.

“What I love is the interdepartmental collaboration we have around public events, operational challenges, and developing strategic goals on campus,” Amy stressed. “The Seminary allows people from many different walks to collaborate with one another.”

Amy pointed to a weekly meeting run by her office where all campus service providers gather to discuss the next ten days’ worth of Seminary events. It is there where potential issues are identified and discussed. “Most importantly, this group really loves one another and has fun.”

Another aspect of Amy’s role that has provided her with enormous joy and satisfaction is her interaction with Princeton Seminary students.

“I feel that my role contributes to the educational environment of our campus in meaningful ways. Auxiliary Services creates and fosters an environment where students can grow and learn inside and outside the classroom.”

Amy’s department also hires students for on-campus jobs that serve as practical learning opportunities. There, she explained, they can gain valuable skills in hospitality, customer service management, logistics, and operations.

“One of the most rewarding things I experience on a yearly basis is when students come back to campus, purposely find me, and tell me, ‘I loved working for you. You taught me things I would never learn in the classroom. You taught me how to be hospitable. You taught me how to entertain.

You taught me to do all the things that I have to do as a senior pastor that I would never necessarily have thought about.’ Those types of things are so meaningful.”

Amy added that her students are often the first faces visitors to Princeton Seminary would see after often long and arduous journeys and would be the first line of defense when a crisis would occur. “We provided them with necessary life skills,” she observed.

After more than three decades on the Seminary campus, Amy has found herself in a mentorship role for many of her colleagues. “I think it’s really important to listen. I think it’s important to lead by example. I strive to model collaborative behavior, and that’s what I want to see in my team as well.”

She added that her team knows they will always find a safe space when they come to her with issues that need addressing. I’m approachable. I have an open-door policy that’s 24/7 whether I’m at home or at work. I try to demonstrate a willingness to work alongside others no matter what your role is on campus.”

Ultimately, Amy strives to create a transparent, collaborative environment in which her team members feel emboldened to share their ideas and have an opportunity to shine and grow.

“I think when the team is heard, and they feel appreciated, it increases engagement and motivation to actually work collaboratively towards shared goals.”

For her entire professional career and across multiple generations, Amy has championed the enduring mission of the Seminary and has loved every minute of it. “I am so lucky to have had so many different roles.”

Amy with colleague Rev. Dayle Gillespie Rounds, Associate Vice President for Alumni and Church Relations, at the 2024 American Academy of Religion (AAR) and Society of Biblical Literature (SBL) Princeton Seminary reception.

Amy at Seminary Fest with former colleague Sushama Austin-Connor.

Amy with colleague Yenny Runachagua at the 2024 Annual Golf Challenge to support The President’s Fellows program.

FALL 2024 EVENTS

Enjoy this look back at some of our fall events, which provided vibrant opportunities for our community of educators and learners to engage, reflect, and grow with each other.

Can We Hold Together in a World Coming Apart?

In 2024, the PhD Studies program at Princeton Seminary was awarded a one-year grant from the Wabash Foundation, “So That We Might Build Together: Cultivating Honest Conversation, Enduring Trust & Mutual Care in the Midst of Deep Difference”. The project kicked off with a panel featuring faculty members Kenneth G. Appold, Lisa Cleath, Keri L. Day, and Kenda Creasy Dean, and was moderated by Dr. Heath Carter, Associate Professor of American Christianity and Director of PhD Studies.

The Church, The Pastor, And Resonance In An Accelerated Age: Theological Conversations with Hartmut Rosa

The Center for Barth Studies hosted a two-day event for internationally recognized practical and constructive theologians, and renowned sociologist Hartmut Rosa.

Participants explored the future of congregational life and pastoral identity through critical theological engagement with Rosa’s ideas and their implications for ministry in the present.

The Herencia Lectures

Last year’s lecture series focused on the theme Christian Nationalism: A Dangerous Threat to Democracy and featured Dr. Miranda Cruz Zapor, Professor of Historical Theology at Indiana Wesleyan University, Dr. Matthew D. Taylor, Senior Protestant Scholar at The Institute for Jewish, Christian and Muslim Studies, Dr. Joao B. Chaves, Assistant Professor of the History of Religion in the Americas at Baylor, and Dr. Raimundo Barreto, Jr., Associate Professor of World Christianity at Princeton Theological Seminary.

Geddes W. Hanson Lecture with Claudrena N. Harold

Dr. Harold considered how several of gospel music’s leading voices responded to some of the most pressing social issues of our time. Dr. Harold’s talk was followed by a Q&A with Dr. Wallace Best, Hughes-Rogers Professor of Religion and African American Studies at Princeton University.

A Conversation with Priya Parker

Iron Sharpening Iron, an executive leadership program for women, marked its fifth anniversary with a special event featuring Priya Parker, author of The Art of Gathering Parker invited attendees to reflect on how to thoughtfully design gatherings that reflect who we are—in all of our differences—and the world we desire to build.

SPRING 2025 EVENTS

Whether you join us on campus for a lecture, at the Farminary for a meal, or online for a seminar, we look forward to welcoming you to our learning community for life!

Princeton Seminar Series: Spring Seminars

Now Available

Online, discussion-based seminars running throughout the spring on topics including Theology and Mental Health, Antiracist Hermeneutics, Thinking Politically with Kierkegaard, and Postcolonial Preaching

Thompson Lecture: Speaking of Tongues: 1 Corinthians, an Amulet, and the Poetry of M. NourbeSe Philip February 20 with Dr. Laura Nasrallah

World Christianity Conference: Migration, Diaspora, Transnationalism in World Christianity

March 10–14 featuring lectures by Dr. Kathryn Gin Lum (Stanford University), Dr. Abel Ugba (University of Leeds), and Dr. Deanna Womack (Candler School of Theology).

Stone Lectures

March 24–27 with Dr. Choon-Leong Seow, Cupples Chair in Divinity, Vanderbilt University

Martin Luther King, Jr. Lecture

Thursday, April 3 with Dr. Brandon Terry, author of To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Carols of Many Nations

Featuring the Princeton Seminary Chapel Choir led by C.F. Seabrook Director of Music Martin Tel, this annual tradition included scripture readings, anthems, and carols offered in various languages that represented the diversity of the Princeton Seminary community.

Praithia Hall Lecture

Monday, April 21 with Dr. Danielle McGuire, author of At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance

The Princeton Forum on Youth Ministry

April 29–May 2 celebrating 30 years of the Institute for Youth Ministry

First Thursdays at the Farm

Summer 2025 begins May 1 featuring scholars, activists, and artists being interviewed over dinner prepared by a world-class chef who uses Farminary produce to create part of each meal.

Commencement (Princeton University Chapel)

May 17

Visit ptsem.edu/events for more details and to register for our upcoming events!