SENIOR EDITOR Marlow Hurst EDITORS Nandini Dhir Harry Gay Ariana Haghighi Bonnie Huang Patrick McKenzie

Rhea Thomas DESIGN Bonnie Huang

Rhea Thomas

SENIOR EDITOR Marlow Hurst EDITORS Nandini Dhir Harry Gay Ariana Haghighi Bonnie Huang Patrick McKenzie

Rhea Thomas DESIGN Bonnie Huang

Rhea Thomas

COVER PHOTOGRAPHY Nandini Dhir The views in this publication are not necessarily the views of USU. The information contained within this edition of PULP was correct at the time of printing. This publication is brought to you by the University of Sydney Union. Issue 02, 2022 @pulp.usu www.pulp-usu.com If you would like to contribute to upcoming issues of PULP, we would love to hear your ideas. Get in contact with us through pulp@usu.edu.au.

In August we’ve been welcoming new and returning students to university life. Highlights include the sellout party at Manning, launch of PULP magazine, and a packed Welcome Fest. The USU has also brought back the pool tables in the Wentworth building while scrapping the old fee — they’re now free to use. Just down the hall from that is Foodhub — a free food pantry initiative for students in need — which we’re providing in collaboration with the SRC.

Transparency is fundamental to us — so we’re regularly publishing monthly reporting and Board meeting minutes on the USU website. As of August 25, the USU has 40,000 members. This is the highest membership we’ve had since voluntary student unionism was enacted, and over the past 2.5 years, the USU has grown by almost 11,000 members.

Following years of delay, the University has been progressing the development of a Disability Space through discussions with student representatives and groups. Due to accessibility requirements, the current Ethnocultural Room was earmarked from the start as the location for this. The USU is committed to the new Disability Space and replacement Ethnocultural Room — both located in Manning House — meeting the needs of the students who will use them.

Finally, like many of our members, the Board is concerned that the USU has unethical investments. Knowing that an overnight solution to this would lose our members’ money, we’ve been systematic. We’ve now changed our Investment Policy to formalise our avoidance of investments in unethical sectors including fossil fuels. With a mandate to have USU investments be more ethical and diversified, the Board has appointed an investment manager to realise this.

REPORTS PRESIDENT Cole ScottCurwood

VICE PRESIDENT Telita Goile

In this post-pandemic world, connection remains the ever elusive white whale. With the semester well under way, now is a great time to join a club, attend a revue, head out to a Verge exhibition, or volunteer with our V-Team.

If you saw a club stall that you liked at Welcome Fest, please join. It can be intimidating at times to put yourself out there, but I promise that there is a like-minded community out there waiting for you.

On another note, we are proud to announce that all USU bathrooms now provide free period products for people who menstruate. Please make use of them. We are always looking to improve accessibility for all students on this campus.

HONOURARY TREASURER David Zhu

Driven by lower-than-expected income, boosted by higher-than-expected sales, and despite my prognostications of doom and gloom last month — we have had a fantastic July and are on track to repeat our incredible financial performance last year. Thank you to the incredible work from Andrew, Rebecca, and the rest of the organisation to achieve this result. However, there is much macroeconomic uncertainty and the winds can certainly shift — and so again I stress the need to look beyond the on-paper surplus figure. On investments, we have progressed with success on our Request for Tender (RFP) to our Investment Manager, with the Finance Committee and then the Board having approved the relevant proposal. I’m proud to report to our wider membership that we are now close to attaining an investments portfolio that not only reflects the values of our members, but also gives value back to the membership.

HONOURARY SECRETARY Isla Mowbray

Hello again PULP readers! Just a few updates from me this month! For club executives, the USU is in the process of establishing Club Communities. These club focus groups will allow club executives to come together and speak to the USU C&S team directly. We want to hear your feedback and understand what the USU can be doing better to support you. For more information on this please email: i.mowbray@usu.edu.au. In other news, we have our music festival coming up: Someday Soon! If there are still tickets left by the time you’re reading this then make sure to snatch them up. And lastly if you read this edition of PULP and think “wow, I would love to write something and have my words immortalised in the glossy pages of Pulp magazine,” then make sure to reach out to the wonderful editors.

PULP is published on the sovereign land of the Gadigal People of the Eora Nation.

We pay our respects to Elders past and present, as well as Indigenous members of our creative community. We respect the knowledge and customs that traditional elders and Aboriginal people have passed down from generation to generation. We acknowledge the historical and continued violence and dispossession against First Nations peoples. Australia’s many institutions, including the University itself, are founded on this very same violence and dispossession. As editors, we will always stand in solidarity with First Nations efforts towards decolonisation and that solidarity will be reflected in the substance and practice of this magazine.

Sovereignty was never ceded. Always was and always will be Aboriginal land.

Senior Editor Marlow Hurst

In Terry Pratchett’s book The Truth, protagonist William de Worde claims that…“Nothing has to be true forever, just for long enough.”

ISSUE 02 of PULP magazine will be true for exactly as long as it must be. Nothing more, nothing less. So view it while it’s veracious!

06

There was a certain thrill in seeing the first print issue of PULP stacked around campus and peppered across Sydney, picked up by students and passersby alike. Receiving comments from new faces in person and messages from new names online. With words of support, excitement, and feedback, we were refuelled with ideas for this second issue of PULP.

PULP is a growing magazine, with an emerging community of contributors and readers, alongside a developing style of print and digital aesthetics. Working off the back of our foundations built in ISSUE 01, we hope you can see the beginnings of PULP flourishing into a space to platform the voices, works, and ideas of student creators across Sydney.

ISSUE 02 of PULP features works in categories of ‘Film’, ‘Place’, ‘Comedy’, ‘Literature’, ‘Culture’, and ‘Recess’. We have been ravenous for food content and are eager to share our nostalgically named food section, in the hope of illuminating corners of Sydney’s food culture we thought we were familiar with (read: a tour of Harris Park’s food scene and some hot takes on Merivale). ‘Recess’ embodies a sense of play, a break from the seriousness, and the consumption of something deliciously comforting that was an integral part of all our childhoods.

The ‘Place’ section not only sits on campus and overseas, but liminally between the two — exploring by the personal experiences of the contributors in this issue. ‘Film’ spans from Nickelodeon TV shows to foreign films. The art and photography throughout this issue also interrogates how place and identity intersect; not only are they beautiful images, but they also offer themselves up as a site for reflection.

Across this seemingly miscellaneous assortment of works, we hope ISSUE 02 introduces you to new combinations of colours, shapes, words, and ideas.

Thank you to our contributors for bringing a creative concept in their minds to a page, and thank you to our readers for taking these visuals and letters from the page and into your minds.

Editorial 07

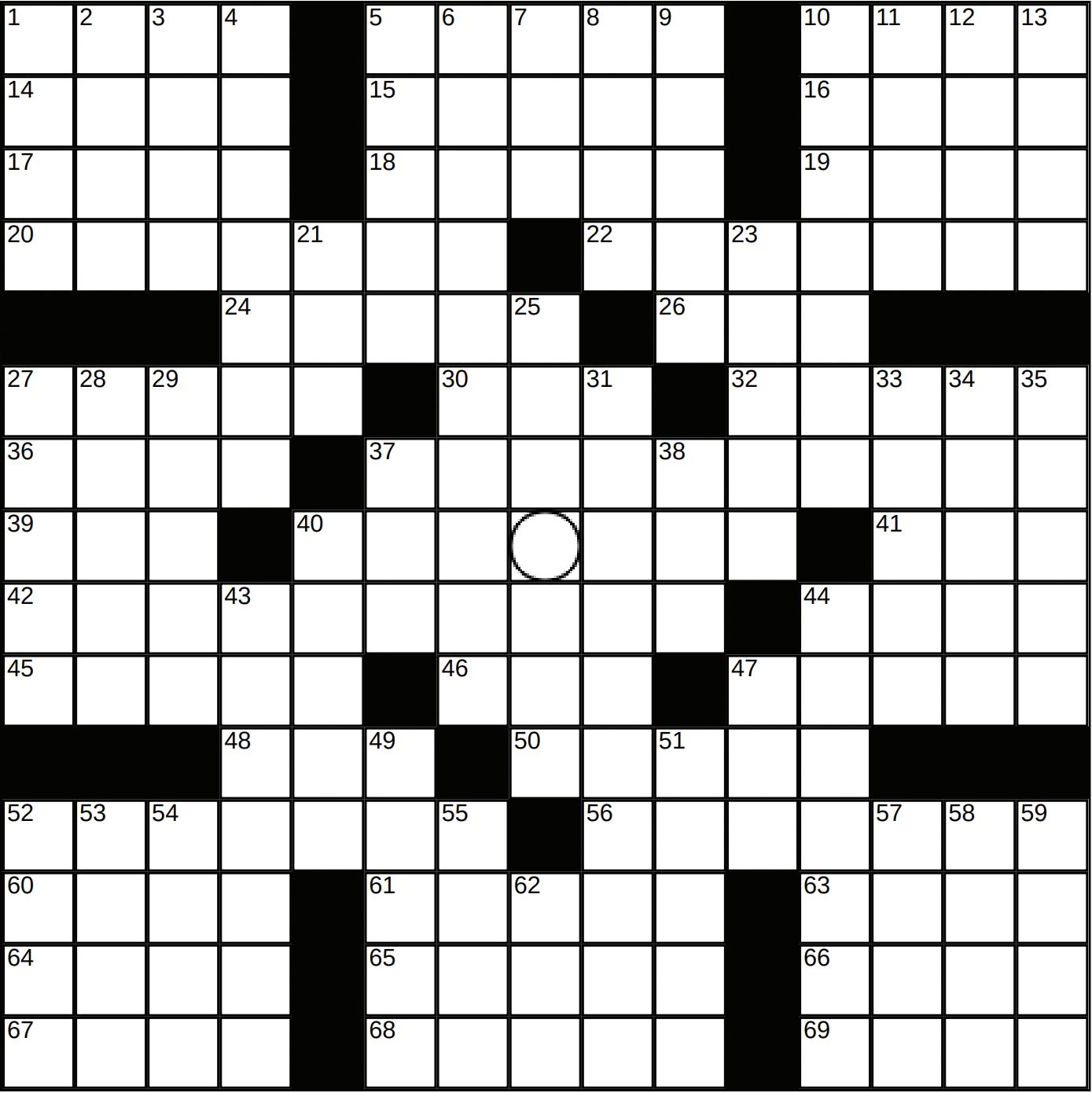

PLACE Poésie du départ: The Airport on Film 11 Azardi15 灣仔20 bakehouse qtr22 CULTURE YouDunnit: Interrogating an Internet phenomenon 25 Dunedin Sound28 Collective Reading: The Politics of Reading Together 30 Stray32 ‘Reading the Room’: Emotions of the Korean New Wave 35 Sex? In my city?38 FILM CONTENTS

LITERATURE evergreen41 “Where’s my legacy gone?”: The chronic misrepresentation of poet Gwen Harwood 42 Gilgamesh and the Invisible Hand44 RECESS Little India47 The Merivale Monopoly50 FASHION + ART Untitled (2022)55 Suburban Alien60 Studies for Icon (The Archangel of Australia) 66 tomorrow year68 COMEDY70 PUZZLES74

Place

Poésie du départ: The Airport on Film

Written by Harry Gay + Andy Park

Written by Harry Gay + Andy Park

Sydney International Airport, 11am. Early morning travellers have boarded their flights and the long queues have subsided. Travelators run without any sign of human life. Beaming lights overhead refract off the floor. Bright signs distend themselves from the ceiling. A series of arrows. Arrivals, departures, food court, carpark.

Airports are the quintessential liminal space. As two intrepid student journalists, we found that going to the airport without a plane ticket makes for an odd experience. There’s a comfort here, a feeling of nostalgic reverie — memories of arriving early at the behest of fathers worrying we’d run late, or the ritualistic consumption of McDonald’s breakfast. It’s a place defined by movement — extended families in slow lines, travelators propelling bulging suitcases and occupied seats quickly displaced. Even people there who aren’t strictly in motion aren’t quite ‘there.’ Those slouched on the leather seats enjoying a moment of respite, or people fuelling up at the

food court are there only to move on with the calling of their flight. Built in 1920, Sydney International Airport is one of the longest-running airports in the world. For us there with no real aim, we were suspended in time and space. We were certainly in motion, moving from terminal to terminal, but by virtue of having no destination we were essentially stationery.

French postmodernist Michel Foucault coined these liminal spaces as “heterotopias”. Literally meaning an “other space,” heterotopias refer to cultural sites and institutional locations which have an off-kilter, unsettling quality to them. Though difficult to precisely articulate, United States Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s iconic one-liner in defining what constitutes pornography is apt: “I know it when I see it.” They are places of constant change and frenetic movement but, equally, are eternal totems of transit — a still, unchanging “non-place” perpetually facilitating moving people and planes.

Film and media reflect this strange heterotopic reality of the airport. Brian Eno dedicated an album to the ambient sounds of the airport. Home Alone 2: Lost in New York sees protagonist, Kevin, get lost in the hustle and bustle of the airport. The world around him changes as he boards a flight in Chicago and ends up in New York, the airport serving as the border between two worlds and a place of departure. In La Jetee and its remake 12 Monkeys, the airport becomes a space of temporal disequilibrium. In Orly, the film jumps between various narratives of individuals and their minute interactions, all from different countries. In the film’s climax, the airport is emptied and the camera remains fixated on the abandoned, hollowed-out halls. Here, the airport becomes a nationless zone, a space devoid of borders.

Heterotopias are also constituted by seemingly incongruous elements which make it distinctly whole. Under neoliberal capitalism, airports are a kaleidoscope of commerce, glittering

PULP 11

with duty-free stores, food outlets, casinos, hotels, and movie theatres. These quotidian opportunities for fun are a stark contrast against stringent border control measures. Hence, the airport can be seen as an amalgamation of multiple modes of power — the coercive enforcement of state power embellished with the shiny exterior of consumerist choice.

The notion of airports as zones of political control is reflected in Catch Me if You Can, which follows Leonardo DiCaprio as Frank Abagnale on the run from Tom Hanks as FBI agent Carl Hanratty. In the film, Abagnale travels in and out of airports freely, flaunting this fact through various comedic montages of him in disguises. However, Abagnale’s ability to go about undetected is a privilege afforded to him by his inherent whiteness. He doesn’t face the same scrutiny that a racial or ethnic minority may face in these spaces. In 2004, we saw Tom Hanks feature again in the hustle and bustle of an airport. The Terminal sees an Eastern European refugee named Viktor forced to live in Kennedy International airport after a coup in his fictional home country of Krakozhia renders his passport invalid. Unlike Frank Abagnale, Viktor, as a non-English speaker, finds it difficult to navigate a space where he cannot speak the language. With his unwavering charm, Viktor makes the airport his home and finds comfort in the furniture of fast food chains, miscellaneous retail stores, and a dozen other product placements. By the end of the film, Viktor is able to go free and enter the US after only nine months. Though entering America is seen as a victorious and happy ending, this is not the reality for many refugees hoping to enter other countries. The film is loosely based on Iranian refugee Mehran Karimi Nasseri, who spent 18 years in the departure lounge of Paris’s Charles de Gaulle Airport, until he was hospitalised in 2006. In 2018, an event reminiscent of this occurred when a Syrian refugee spent seven months in a Canadian airport.

For people of colour and ethnic minorities, the airport can be a hostile and stressful environment. Since the September 11th attacks, airport security tightened all over the world. Border police patrol the area and there are security check ups at every corner. We hear accounts

of people being taken aside, interrogated, scrutinised, searched more thoroughly — even imprisoned — all based on their racial or ethnic identity. During our expedition, we saw firsthand police patrolling around, pestering people in lines with bulky weapons at the ready.

Racial profiling is a huge issue in airports, but this is not a recent phenomenon. Global border checking has its roots in early 20th-century South Africa, with laws designed to appear fair which in reality made it possible to restrict entry to Indians, poor white people, and Jewish folk. The US has infamous ‘language tests’, and we remember the White Australia Policy on our own shores. These practices did not go away after aeroplane travel became more commonplace post-World War 2. Proof of biases, racism and xenophobia exist among the staff and systems in place with airports today. A racist display was discovered by TSA officers in the communal workplace of the Miami International Airport in 2019. The previous year, air marshals went public that TSA supervisors were pressuring them to put African American and Hispanic travellers wearing certain types of clothing through additional screenings. 2019 saw ProPublica release an article pointing out how TSA body scanners discriminated against black women and women of colour based on their hair. This isn’t even pointing out how facial recognition softwares in airports already have difficulty reading the faces of racial and ethnic minorities.

Besides heightened security, the airport can also be generally unaccommodating and unwelcoming. Following signs to a supposed prayer room at Sydney Airport, we decided to see where non-Christian travellers could be made to feel they can practise their religion in peace and we found ourselves walking down a labyrinthine maze of carpeted tunnels. We passed by employees on our way past grey anonymised doors and offices.

We finally came across the prayer room. Pushing past a heavy glass door that scraped along the ground, we found ourselves in a dishevelled room that, by the looks of things, had not been maintained by the airport staff. Shelving units

PLACE

12

PULP 13

stood broken and mouldy. Coffee cups, banana skins, and all sorts of rubbish littered the area. There were a couple of books for different religious groups, along with an inconspicuous Clive Cussler novel sitting alongside them. The room was dark and uninhabitable, a testament to the airport’s lack of consideration for those of differing religious backgrounds.

The experience of going through customs felt like its own process of religious confession and ritualistic cleansing. There are certain unspoken rules when talking to officers. You need to keep it brief, don’t joke, don’t say too much, don’t say too little. It’s less a process of saying where you’re going and who you are, and more a process of proving that you belong, proving that you are a traveller, a tourist, a citizen rather than a foreigner, a refugee, or a terrorist. If you aren’t considered to belong according to certain people, then you are immediately considered suspicious — God may be fair and just, but the State certainly is not. In Other Spaces, Foucault explains how heterotopias are spaces which open and close where, unless one is already compelled to enter, ‘‘the individual has to submit to rites and purifications [. . .] to get in one must have a certain permission and make certain gestures.’’

At their core, airports are a limbo on Earth. In this fraught yet unmoving heterotopic space, sovereign power plays on the maybe-logic of an infinite number of potential future occurrences. The idea that something might happen, that there may be a threat coming into the country, that someone could be hidden among the rest, creates a system where everyone

is guilty until proven innocent. In this space, we are political subjects who become acutely aware of the ways in which we are surveilled and, more importantly, the way we police ourselves. It’s poignant that the liminal appeal of airports is a result of the same structure which excludes certain people from comfortable travel — and often travel altogether.

Our visit reminded us that perhaps the greatest appeal of airports is that they are a concrete space which materialises many parts of our large experience of Life. The anxiety we have about where we are headed, the strict confines of time, and the looming head of authority are all things which abound beyond the four walls of airports. Some of us are the bright-eyed travellers excited to explore after the claustrophobia of the pandemic while others sit at home watching planes fly. Some of us are sitting at Departures and just want to go home. For every passenger on a landing plane, there is one waiting to take flight.

PLACE14

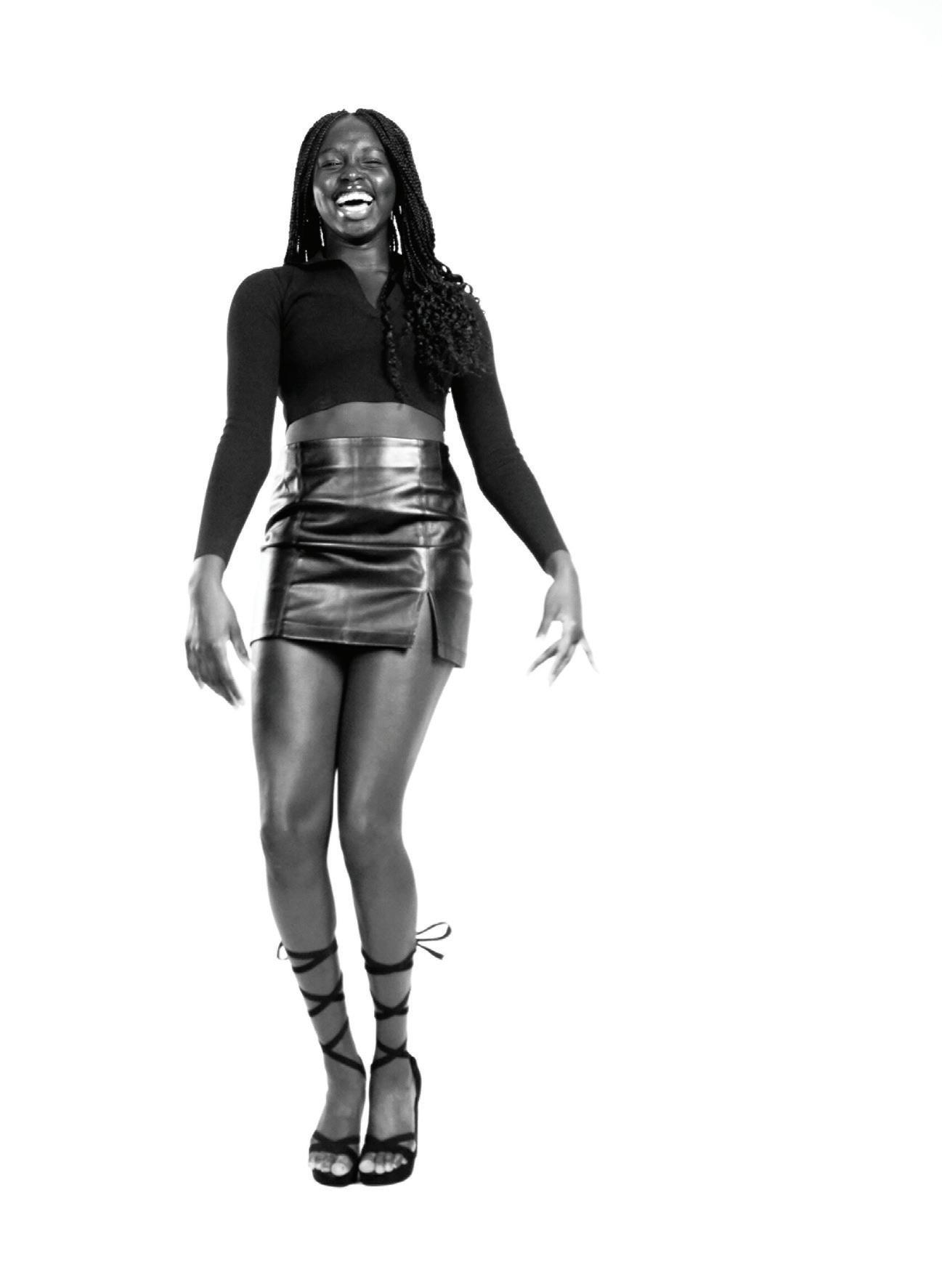

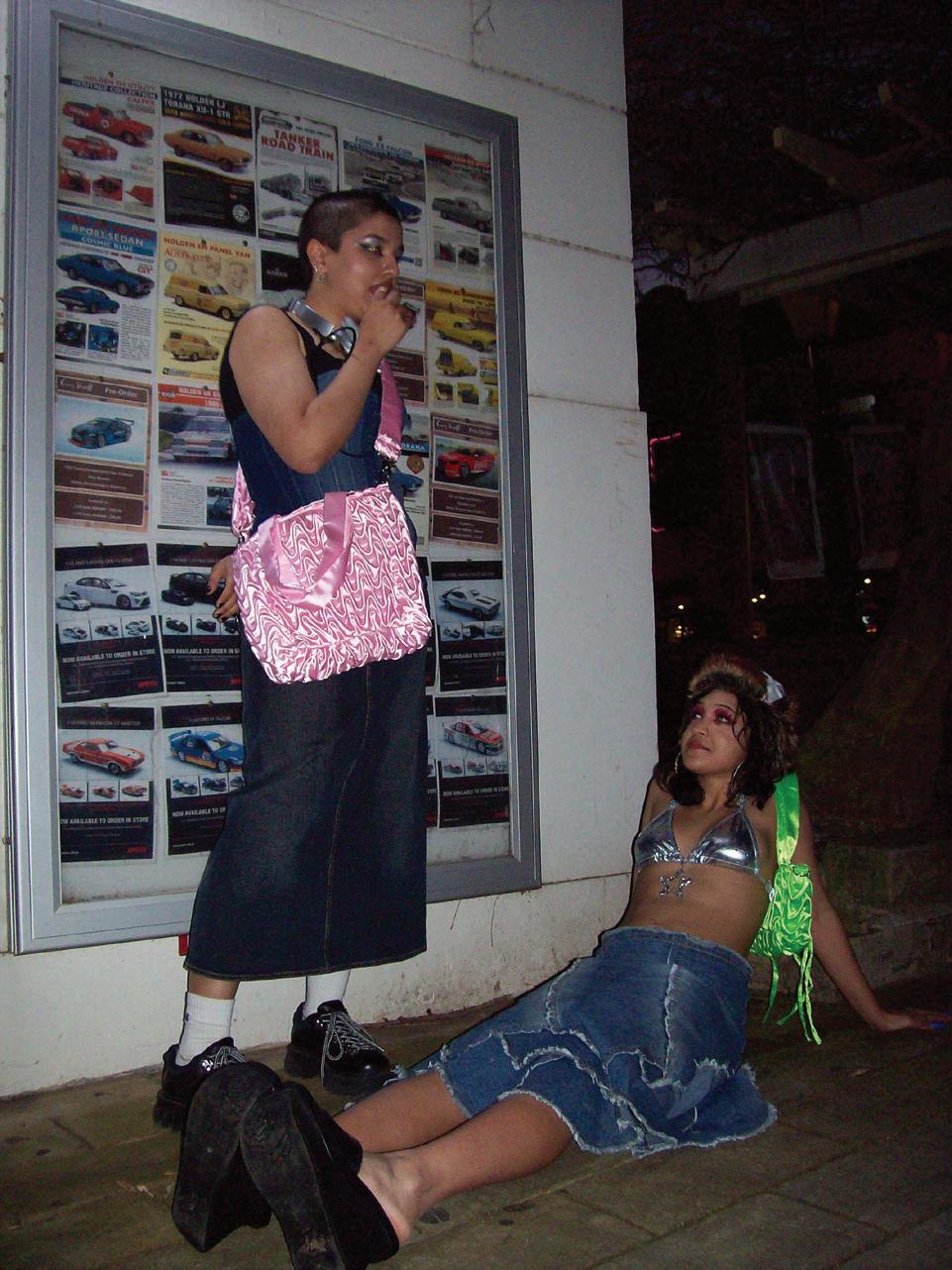

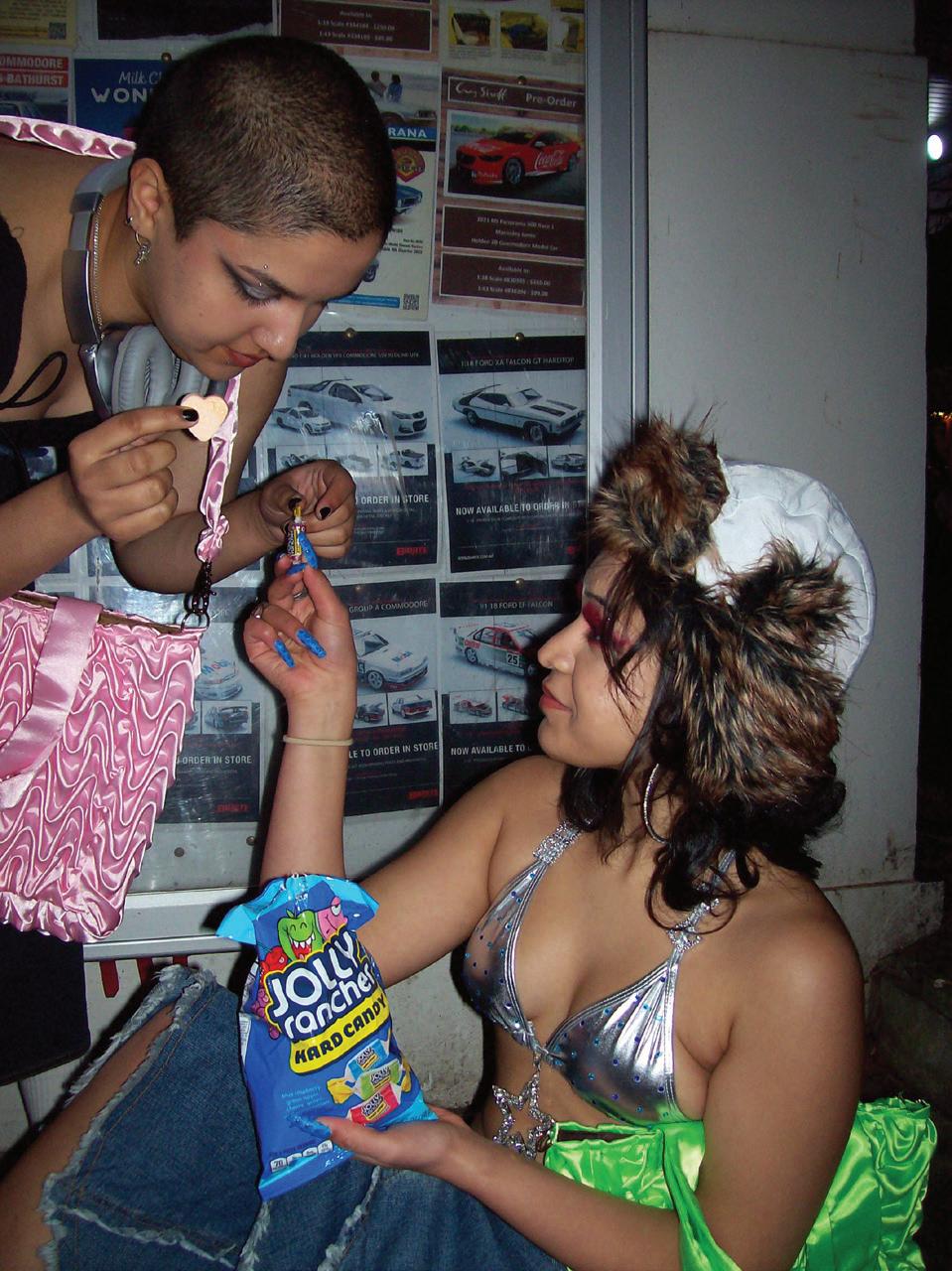

Azadi meaning Freedom in Dari. Azadi is a series of photographs coincidentally taken exactly a year after the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan. Through the stark juxtaposition of ethnic attire — placed in the context of the University of Sydney — it sought to celebrate my Hazara roots while recognising how far (both physically and metaphorically) we have come. From Jaghori — a town in the central highlands of Afghanistan — to the unceded Gadigal lands, these photos are an ode to the resilience of my people, and to the joys of being a diverse uni student.

Azadi

PHOTOGRAPHER

Nishta Gupta

MODEL Naz Sharifi

Azadi

PHOTOGRAPHER

Nishta Gupta

MODEL Naz Sharifi

PULP 15

PLACE18

19PULP

Written by Cherie Tse

You know the harshness of her buzzing glow, Red neon lights in red light districts, The drowning sirens of four am, red Kool aid vodka fishbowl and the shocking flash of a date forgotten Lungs coughing up, no — strangled by, the white gloom inhaled smoke and I see — red, In her cheeks from the sly sliver up Lolita’s leather skirt, illuminated by your Drive, in the red taxi cab waving the red Flag, white bauhinia fingered around in your unconscious neck, Dead or Alive, swirling slurred slimy syllables around the sutures in your mouth, spit them bloody RED Gweilo, yanking a man who once dug his heels Into the dirt of a land foreign to The whites who flush red At the whiff of white, red, wine.

But I know the spine of her subdued hues, The extra strokes of a losing language Splatters thrown across a painted sign, UNDERWEAR, it announces A proud momentum of a backstreet in Wanchai Her olive ferry piers, the scent of China’s presen(t/ce), Hidden behind the waves of splintered bamboo scaffolding and Sweat-drenched concrete cracking in straight edges The way her ginger lights dimly flicker in the echoes of their Cries, between the curves and bends of humming seven eleven The soft crumbs, linger, chew, the pull of a Mango mochi thrown on a fifty cent plastic dish

The company of a dribbled, soaked filled afternoon in The glittering haven of Hopewell, swish, I listen for her footsteps treading lightly behind mine Gripping onto a broken ‘brella All the way home

PLACE

灣仔

20

PULP 21

bakehouse qtr

Written by Kat Porrit Fraser

Written by Kat Porrit Fraser

a child is walking, crying, out of the i-Med radiology lab mum has one hand on her phone the other clutching an X-ray sized envelope sparing a pinky for them to cling to

they disappear beneath a faded red pedestrian bridge with no ends sandwiched between a never-ending wall of ageing red brick and the flashy glass panelled offices of the folks that built it. Arnotts (Pty Ltd)

today I came to see the place my father worked at straight out of uni eating and breathing biscuits, nine to five daily before returning to a share-house round the corner just like me:

“BAKEHOUSE QTR,” the modern glass balconies, massive blue trapezoid pillar directory, window installation littered with logos and faux gold-plated bin tell me.

how much labelling could make a building built for biscuits in 1908 seamlessly slip into the 2020s? here, you can hear a hum, buzzing like trucks lined up with engines on, ready to leave or the echoing of decades of revving machinery here,

PLACE

22

you’ll find orthodontist surgeries beside heritage street lights a dance academy behind a WARNING AMMONIA LEAK sign deliveroo drivers and mini golf courses and my cup of chai

yet still space where the factory met the train line for a patch of grass someone escapes to on their lunch break carrying a plastic container of coles pumpkin soup at their side.

PULP

23

Culture

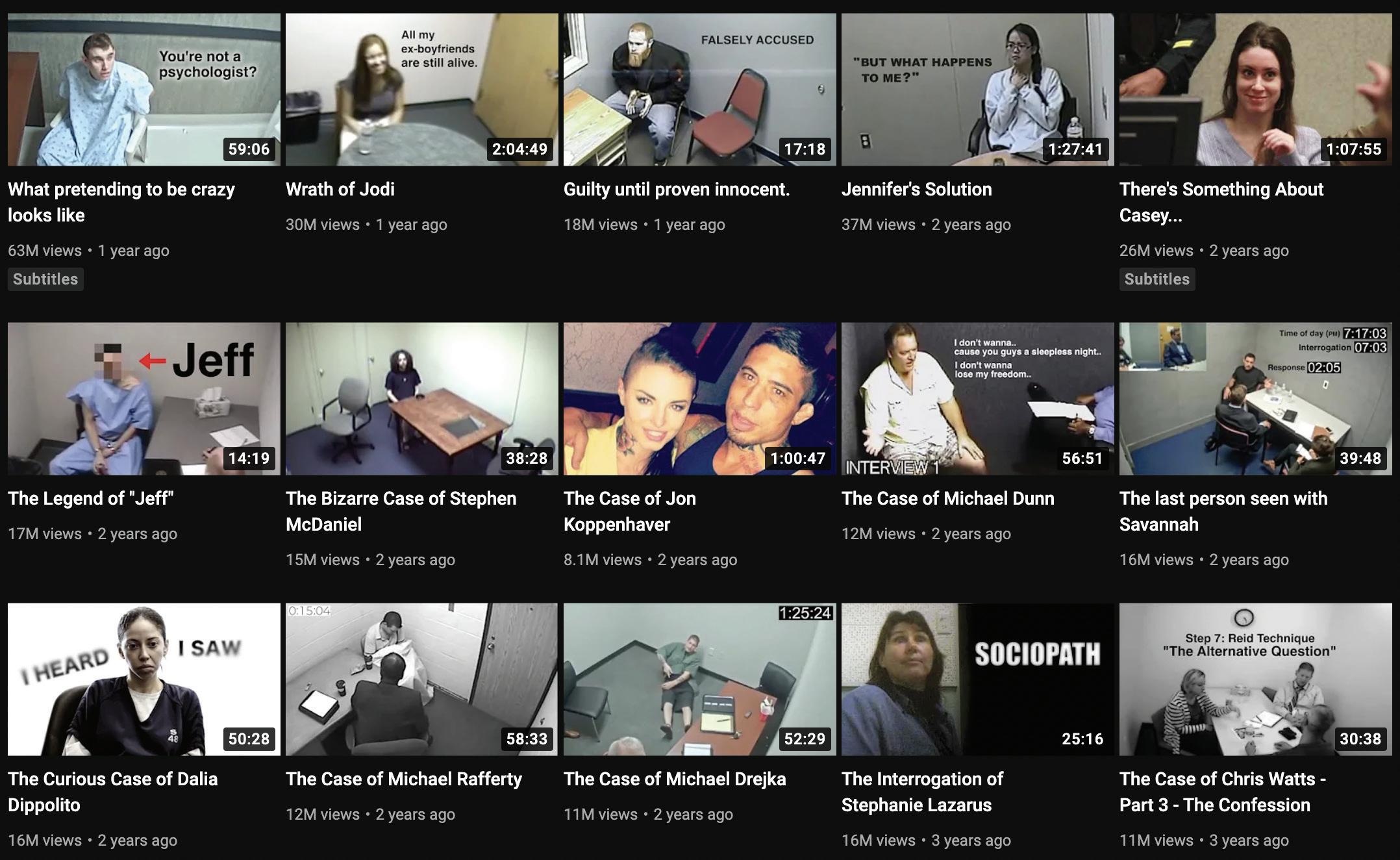

YouDunnit: Interrogating anInternet Phenomenon

Written by Nicola Brayan

On my way to work, I like to listen to podcasts. One that I recently finished is Father Wants Us Dead, which covers the story of how John List murdered his family. It’s well-produced, with great research and editing, but there was something off-putting about its tone that I couldn’t identify until the final episode. Hosts Jessica Remo and Rebecca Everett reflect on the lasting impact the story had on those who knew the List family. Their conclusion caught me off guard: the List case, they reflect, “no longer feels like a true crime story.”

How could that be the case? How could a crime having lasting impacts on victims make it less like a true crime story? Yet, Remo and Everett came to a conclusion reflected in much coverage of this genre: there is a difference between true crime and True Crime.

True Crime has entertained us for decades; urban legends like Jack the Ripper are, arguably, an early example. The genre has, however, experienced an upswing in recent years. Podcasts like Serial and docuseries like

Making a Murderer have received widespread acclaim. The increasing accessibility of media production means that now, True Crime can be produced by anyone with a YouTube or Spotify account.

In most cases, the expansion and democratisation of a genre is a good thing. It allows for innovative productions, driven by market forces and individual creativity, that can lead to the creation of breathtaking media. But True Crime, for me, is different to most entertainment genres. The characters and narrative beats are drawn from real people — real perpetrators and real victims. It covers real experiences of things that are violent and devastating, and, just like the List case, have echoes that continue to sound years after the crime was committed. When a creative is forced to make their content stand out in an ever-growing landscape, either by being more novel or sensational than their predecessors, they can forgo the sensitivity this genre deserves.

I have noticed this most acutely on YouTube. I fell down the True

PULP

25

Crime video rabbit hole when a friend introduced me to JCS Criminal Psychology — longform analysis of police interrogations — and I was hooked. It’s not hard to see why his channel, and others like it, have experienced a popularity boom in the last few years. The production quality is high and the subject matter is gripping, often being well-researched despite the small scale of the team behind it. However, the production scale and lack of industry regulations like those imposed on mainstream media can cause issues with this content.

As well as becoming more accessible, the genre’s exponential growth on YouTube has led to an evolution of the types of True Crime media being produced. Some creators have blended True Crime with other video formats as a way of capturing wider audiences. YouTubers like angel ASMR and The Empress ASMR create videos discussing true crime cases in an ASMR format, channels like Bailey Sarian and Danielle Kirsty recount crimes while doing makeup

CULTURE26

tutorials, and some creators, like Stephanie Soo, do True Crime mukbangs. This is where the gap between true crime and True Crime is most insidious.

I would argue that there is disrespect inherent in reducing the real-life trauma that someone has suffered to a topic of conversation while reviewing makeup or eating fried chicken. There is also an incentive for the creator to be flippant in their delivery: to build rapport with an audience, which is necessary to hold their continued attention and subscription, a YouTuber must be personable. This could look like cracking jokes, noting the killers’ zodiac signs as an ongoing gimmick, as True Crime makeup channel Hailey Elizabeth does, or interjecting with personal opinions at inappropriate times.

This leads to another problem: desensitisation. I have caught myself watching videos about serial killers and being almost unimpressed when they ‘only’ had ten victims. If a creator is talking about something dismissively, you, too, are likely to dismiss it. A

weak claim here would be to say that this makes viewers more likely to commit violent crimes. I don’t think this is true, in the same way that violent games or movies don’t make people more violent; content that simply describes crimes without glorifying them isn’t likely to radicalise someone.

A better concern is that desensitisation to crime makes viewers condemn violent actions less. There is an alarming amount of empathy for perpetrators like Ted Bundy and the Menendez brothers on platforms like TikTok. Creator @bundyswifey makes fan edits begging Bundy to spit in her mouth,describing him as “the love of [her] life,” with only the phrase “don’t condone” in her bio to suggest any sort of condemnation of the many violent murders he perpetrated. This is an extreme example, but fostering any degree of empathy for violent criminals is dangerous. This empathy is especially pernicious when it is used to diminish the culpability of perpetrators, disproportionately favouring those who are young, white and conventionally attractive. It is the dangerous kind of empathy that asks us to forgive people in our own lives for their actions when they fit those same criteria.

This is not to say that no good has come of the democratisation of True Crime. True Crime has always been disproportionately popular with women, who have historically faced higher barriers to entry into traditional media production. Making content more accessible to previously disprivileged creators is important, especially when that content is meaningful to them, both as a form of entertainment, and outlet for telling stories that are more likely to impact them. True Crime media can empower survivors of crimes by celebrating their perseverance. It can educate viewers, to an extent, about behaviours that may keep them safe from falling victims of similar crimes. It can even help solve crimes: the List case was only resolved when somebody recognised List from a segment on

America’s Most Wanted. True Crime can be a legitimate and important form of entertainment

However, this legitimacy is contingent on respectful and informative coverage. When means of production are decentralised, this is harder to police. The most powerful mechanism that consumers have at their disposal is the capacity to hold creators to account. Call creators out when they are irreverent or too sympathetic to vile people. Don’t engage with content you find morally nebulous, and remember that at the heart of True Crime is true crime.

There are survivors who will never recover from the trauma they endured. There are victims whose losses have left irreparable holes in the lives of their loved ones. And there are people who are evil and desperate for attention, who watch people praise killers like Bundy, and see violence as their only path to recognition. True Crime as a genre has rapidly evolved, but don’t let it mutate beyond a point that we can control.

PULP 27

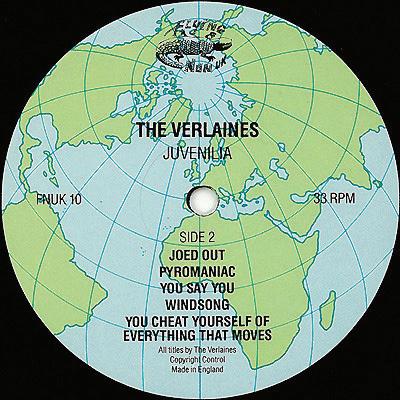

Dunedin Sound

Written by Aidan Elwig-Pollock

Dunedin (Ōtepoti in Te Reo Māori) is a beautiful small city at the arse-end of New Zealand, itself a beautiful country at the arse-end of the world. New Zealand is often overlooked internationally — so much so that it is routinely excluded from world maps by accident. Yet this small, underappreciated city in the southern corner of such a country managed to produce a vibrant and internationally influential music scene during the 1980s and into the 1990s — the Dunedin Sound.

Dunedin today sits in a grey area between town and city with a population of 128,000 people settled around the spectacular Otago peninsula. It is the kind of place where one can look up from the high street and see sheep paddocks sprawled across green, rolling hills in the near distance. It is a gothic city: its suburbs spread across steep streets often shrouded in drizzle, complete with stunning Edwardian, Victorian and neo-Gothic architecture.

Yet Dunedin is no sleepy rural city — this is a university town, infamous for riotous street parties and a vibrant student culture centred around Otago University. Couch burning and the riot squad are phrases associated with invariably debauched parties on Castle Street, a wide, treeless thoroughfare populated by personalised student houses. However, Dunedin nightlife is not restricted to purely outdoor affairs — the city today punches well above its weight with its thriving bar and nightclub scene.

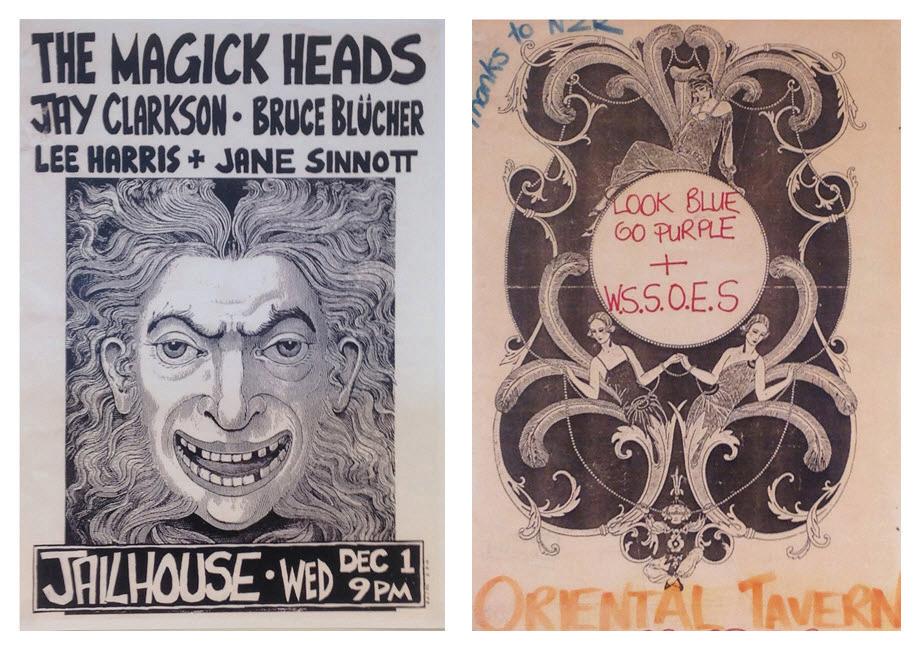

A similar combination of gothic geography and raucous cultural life produced the Dunedin Sound of the 1980s. Dunedin local Shiree Gwynne recalls “lots of venues to see gigs and lots of parties to go to after.”:

“My friends and I frequented the

Dunedin Musicians Club, which, a lot of the time, was local muso’s playing with their bands or just hav[ing] jam sessions. […] There were many other venues as well.”

This included The Empire Tavern, built in 1858 and recognised as the launchpad of the Dunedin Sound.

“The Empire had three floors of bars. All three bars were obviously old and atmospheric. The bottom bar often had solo and acoustic musos playing [...] up the stairs [was] the pool bar; [...] often frequented by Dunedin’s gang the Mongrel mob. Pretty relaxed though, from what I remember.”

Finally, there was the third-floor “band bar” which was “Intimate and fun, almost like being in someone’s lounge.” Altogether, it was “a great venue for bands, including [...] the Clean, the Verlaines and the Chills.”

Gwynne concluded that “The vibe of Dunedin was great. It felt like a hub for nurturing independent music and the arts.” The Dunedin Sound was the jangly core of this independent music scene. Championed by New Zealand’s own Flying Nun Records, bands like the Clean, the Verlaines and the Chills emerged in the late 1970s, coalescing into a thriving scene around 1982.

The Dunedin Sound is instantly recognisable: many of the bands carry a combination of influences from the 1960s — notably the proto-punk of the Stooges and the Velvet Underground — modulated by the splendid isolation of the city and, according to The Chills’ Martin Phillipps, its “cold, drizzly atmosphere”. Altogether, this produced a unique, moody lo-fi sound with significant psychedelic qualities. The Dunedin Sound, filtering into US college radio stations, would be a key influence

for significant American bands like Pavement, Mudhoney and REM.

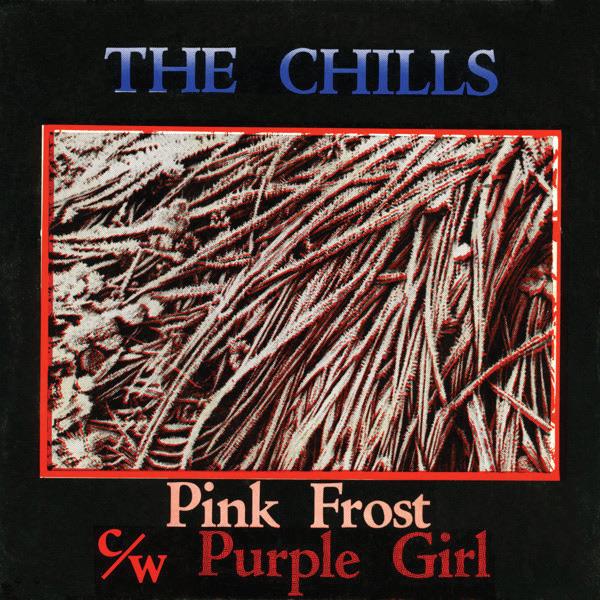

Tracks like the Chills’ ‘Pink Frost’ (1984) exemplify the Dunedin Sound: the piece is driven by a jangly, droning riff that together with an unconventional, deadpan delivery of desperate lyrics produces a haunting, melancholic sound that evokes Dunedin so well. The Clean’s ‘Point That Thing Somewhere Else’ (1981) takes a more psychedelic angle to produce a similar vibe, with soft yet punk-ish vocals set to a roving, dissonant guitar line.

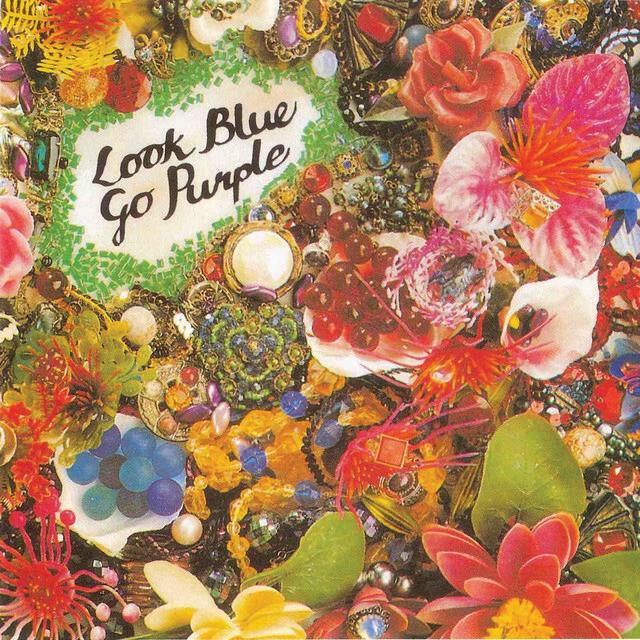

The Verlaines’ ‘Death and the Maiden’ (1983) also carries the gothic theme, combined with classical influences and literary references to poet Paul Verlaine (the founding member of the band, Graeme Downes, would later lead the music department of the University of Otago.) ‘Cactus Cat’ (1986), by Look Blue Go Purple, represents a more whimsical side of the scene and relies on a simple riff to deliver a love letter to a cat that sits somewhere between jubilant and melancholic.

Finally, it would be remiss to omit mention of the Bats (who formed in Christchurch but are so connected to Dunedin that the band is considered a part of the Dunedin Sound) – lead by former bassist of the Clean Robert Scott – and their song ‘Made Up In Blue’ (1986), which epitomises the wistful jangle of the scene, along with a growling bassline that conflicts with Scott’s higher, forlorn vocals.

Altogether, the Dunedin Sound represented the undervalued cultural vibrancy of a remote yet sublime city. Most strikingly to me, the sound of the scene impeccably evokes Dunedin as a place: a melancholic melange of depressed, moody beauty and boisterous cultural life; a certain darkness given a softer edge by a warm heart.

CULTURE28

1 2 3 4 5 PULP 1 Compilation, Look Blue Go Purple: Flying Nun Records 2 Pink Frost, The Chills: Angela Tidmarsh, Carol Tippet, and Terry Moore 3 Juvenilia, The Verlaines: Flying Nun Records 4 Courtesy of the University of Otago Hocken Collection 5 Juvenilia, The Verlaines: Flying Nun Records 29

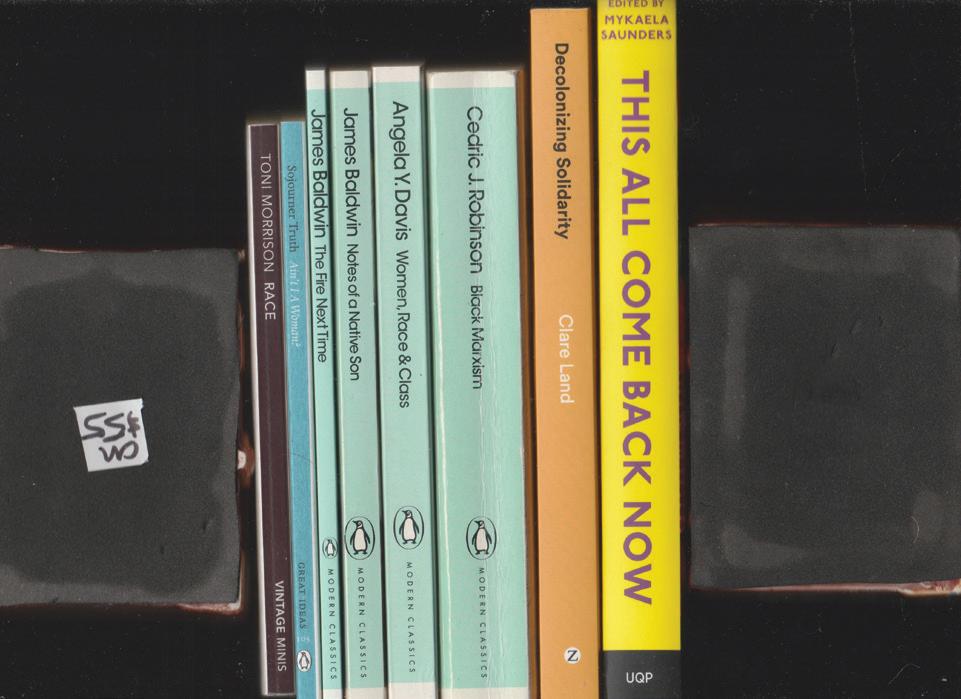

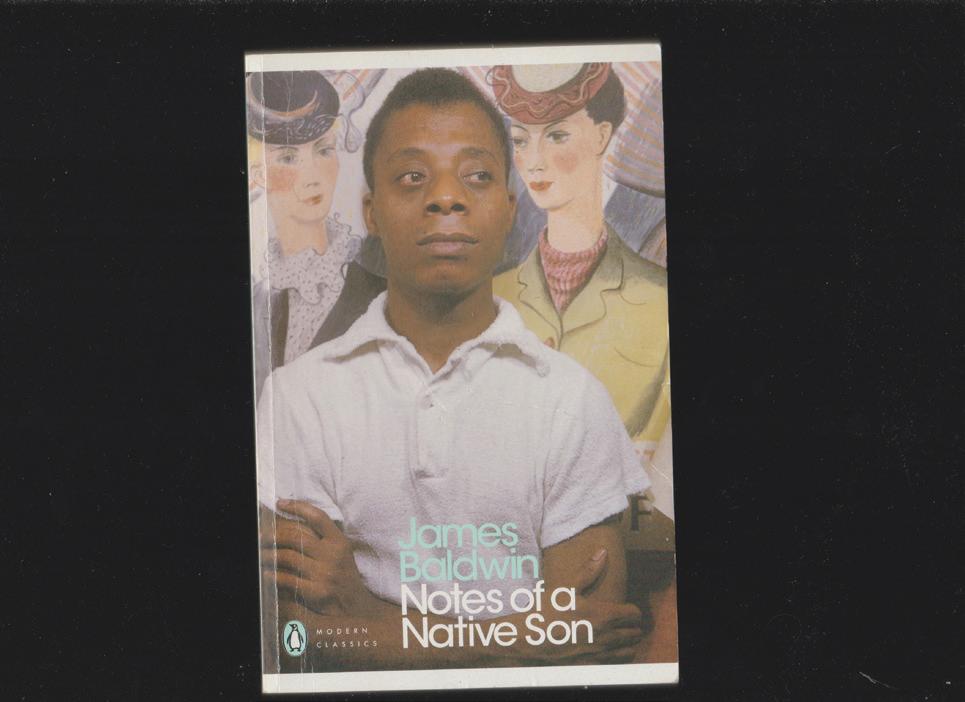

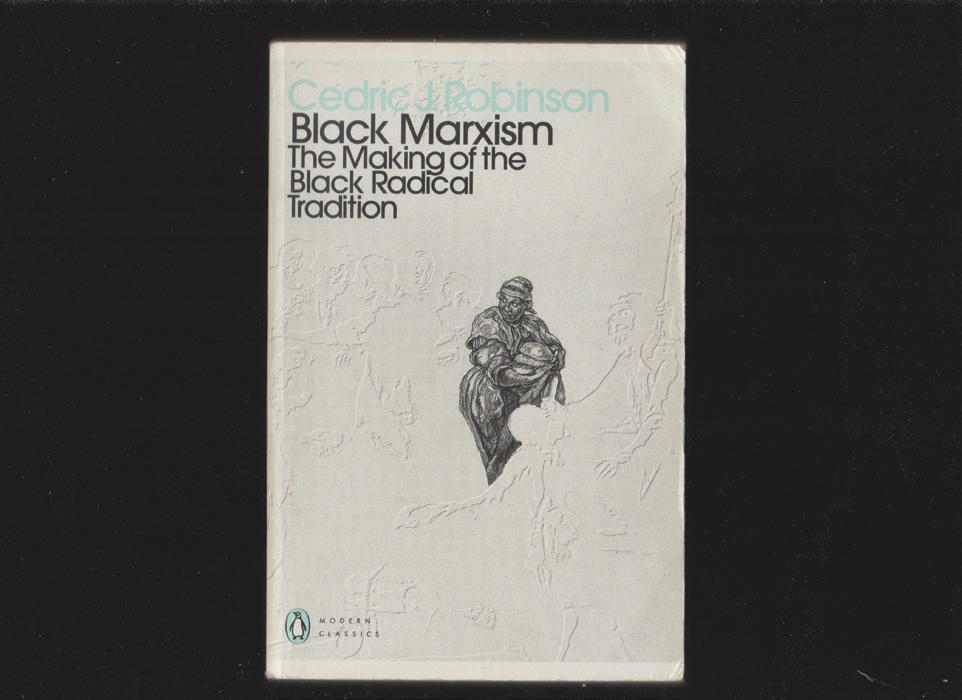

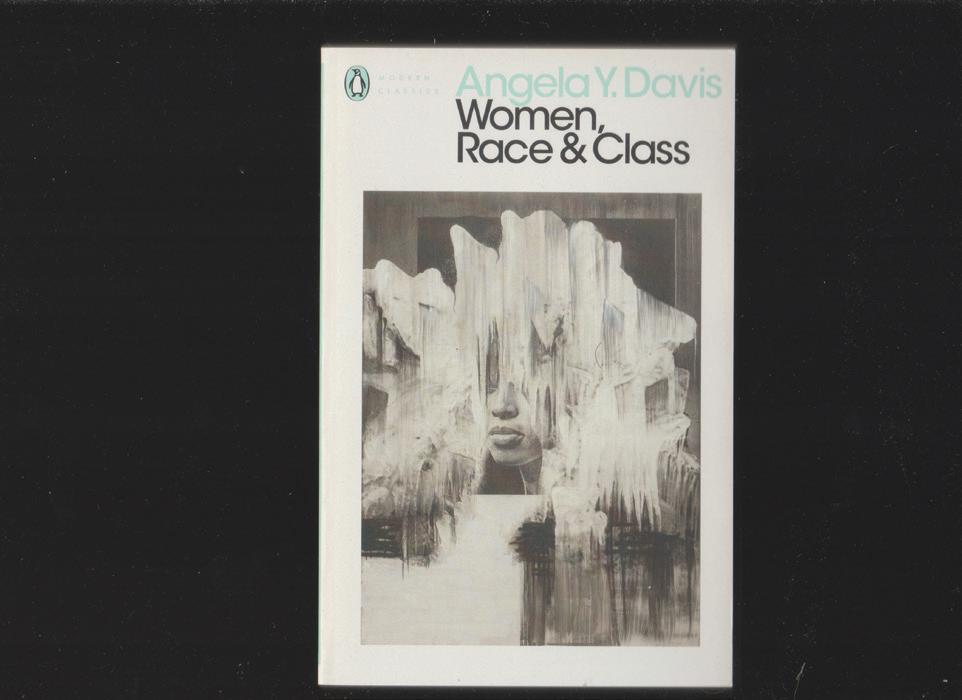

Collective Reading and The Politics of Reading Together

Written by Georgia Mantle

In May 2020, Liat BenMoshe released a book entitled, Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition. The book fused prison abolitionist and disability justice politics, something of great interest to myself and my friend Mali. Mali suggested that we read the text together, both as an attempt to remedy the loneliness of lockdown and to ensure we were critically engaging with the text in a way we often fail to do when reading alone. We imagined that by reading the book together we could connect the text’s ideas to our lived experiences and brainstorm ways to enact the politics Ben-Moshe discusses. Mali posted on Facebook to ask if anyone would be interested in joining us virtually to read this book; the response saw us bring together a group of people who wanted to join us in creating an online space to read and engage with political ideas.

The process of collective reading is a stark contrast to how we often conceive of reading as a solitary act.

While social book clubs and reading groups surged in popularity during the 19th and 20th century as a social space for women who were excluded from education institutions, political reading groups serve a unique function melding political theory and praxis while fostering a unique social space for those who come together to read.

In contrast to the classroom, reading groups allow individuals to come together to discuss ideas divergent from institutional objectives. While the merits of learning within institutional settings are undeniable, there are clear limitations. Faced with the increasing neo-liberalisation of universities and the commodification of education, we must seek out alternatives to educate ourselves and each other. Unlike the classroom, the choice to participate is voluntary and not tied to participation marks or assignment success.

Reading groups have long been a site of political education within radical lefitst spaces. Collective

reading within political parties assists with the development of a shared politic and party lines. The Black Panther party saw education as a pathway to liberation, the idea of “educate to liberate” was core to the party’s political organising. While the importance of education and reading to political movements globally can not be understated, to quote Lenin, “without a revolutionary theory there can be no revolutionary movement.”

We must understand that reading alone is not enough. We must enact the ideas we read about, apply them to our own political contexts while challenging and testing the ongoing relevance of the ideas we read. To read and put into practice what we read can not be done individually, which is why reading collectively facilitates a distinctive relationship to theory and political education. Collective reading provides a unique opportunity to come together, share knowledge and discuss learning.

Through this, communities can emerge providing social and political connections that can grow beyond the space of the reading group.

CULTURE30

Leftist political reading groups provide a space for critical engagement, where people can question and reckon with their politics. Political unity and shared ideology is important for the left, but reading groups allow us to question the politics or party lines in a way that doesn’t serve to delegitimise the left.

In prison abolitionists reading groups, for example, we are able to explore the discomfort that can arise throughout our reading, an acknowledgment that often the ideas we read are new to us and challenge us to think differently. This challenge is taken up collectively with compassion and critical inquiry as we are able to be open and honest without judgement. There is a shared understanding that while we are committed to these ideologies we are still learning, deconstructing and reconstructing our understandings of the world around us.

The collective compassion and commitment to critical reflection I discuss here is not inherent to

reading groups, rather, it is an environment that must be fostered, nourished and reinforced. The honesty and lack of judgement within the spaces is something that people must continually strive for. Instead of judgement, political reading groups should encourage critical reflection, compassionate questioning of comrades, and a willingness to change our minds when we encounter good natured political debate.

When facilitating political reading groups, facilitators must strive for ourselves and participants to not just understand a text but understand how the text relates to our own political context. Through this understanding, collective ideas of how theory can be enacted in praxis can emerge. Providing space to relate the text to our own lived experiences, to explore how we personally connect to a text gives life to the ideas we read about. Reading groups can exist as tools that inspire political action.

After co-facilitating nine sessions for Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison

Abolition with Mali, we were left with a sense of hope, imagining what abolitionist disability organising could look like within so-called Australia.

Inspired by the text, but more so the conversations and passion that arose from collectively discussing the text, I craved a political organising space where we could continue to learn disability justice and abolition while enacting this learning into political action. The result of this imagining was the creation of the Disability Justice Network and from that a Disability Mutual Aid Fund.

The reading group had value in of itself, as a space that brought people together (when isolation was a part of our everyday life) and allowed us to deepen our understanding of radical ideas but the reading group’s true value was its potential and ability to grow into something tangible. From ideas of change to the creation of an ever-growing political space: this is the radical potential of political reading groups.

PULP 31

Stray: “I am a cat. As yet,I have no name.”

Written by Grace Street

The video game Stray opens on four cats, in a cave, avoiding the rain — in typical cat fashion. A fly is swatted at, fur is licked and cleaned, and tails are haphazardly flicking. The frame eventually assumes the perspective of the final cat, marking the beginning of your adventure in a dystopian city. While dystopian game worlds are a familiar sight, a cat protagonist is not so common. Stray’s creators Colas Koola and Vivien Mermet-Guyenet display a mastery over this feline perspective, and its unique place in the gaming canon is what drew me, a video game novice — bar-Mario Kart — to the game. Published by Annapurna

Interactive, Stray’s cat protagonist was no easy feat. Its production relied upon complex, animated cat models, with 23 real felines credited with its creation. What they give to the game is an authentic and endearing portrayal of our fourlegged friends, imbuing each cat with lifelike movement, meows, and personalities.

This commitment to the bona fide cat experience is something of an oddity in video games. What we’ll call ‘scenery cats’ exist in countless game worlds. Twitter account @CanYouPetThatCat highlights a number of these background kitties and outlines rules on whether game

designers have allowed players to pet them. Playable cats are a little less common on the other hand, and where they do appear they are often represented as anthropomorphic creatures. Mae, the protagonist of Night in the Woods, is a cat who is a college dropout returning to her hometown. In Blacksad: Under the Skin, the protagonist John Blacksad is a feline Sherlock Holmes, with a cat’s head on a trenchcoat-clad human body. These games present an inauthentic, yet entertaining cat creation — one that employs feline aesthetics, but weighs it down with human features, stories, and personalities that are comparable to our own.

CULTURE

32

In contrast, Stray’s representation of cats, just as they are, celebrates their agility, elegance, intelligence, curiosity, cheekiness, and playfulness. Sociability would also make its way onto this list if it weren’t for my own cat being the antithesis of it. In an interview with ScreenRant, Swann MartinRaget, Stray’s producer, said that “portraying them [cats] as realistically as possible was something that really drove us along the way.” MartinRaget labels the game a love letter to cats from a team made up of approximately 80% cat owners. And that love and experience really shines through, with optional side quests and exchanges such as rubbing against robots’ legs and creating a cacophony of sounds while walking along piano keys capturing the welltrodden cat imaginary.

Unlike the identifiable personas of cat protagonists in many other games, Stray’s cat is simply that: a stray with no name or backstory. It echoes the opening of the Japanese classic 1906 novel I am a Cat by

Natsume Sōseki: “I am a cat. As yet, I have no name.” While the novel is narrated by an adopted stray cat who develops a hatred of humans, this common pessimistic view of cats was rectified in Hiro Arikawa’s 2012 novel The Travelling Cat Chronicles. Published over a century after Sōseki’s work, Arikaw’s novel begins identically, but this time introduces the touching relationship between a cat and its owner as they journey across Japan. The contrasting depictions of cats and their relationship to humans reveals a complicated history of tales and beliefs, be they both loved and feared as little mysterious creatures who cannot be claimed or owned.

Conveying their more mystical and godlike character, Stray reminds me of the cats who live at Fushimi Inari in Kyoto, recognised for its array of orange arches. Living up on the mountain, the cats frolic around the stores and shrines, and may even jump into your lap. They’re perplexing and beautiful — disappearing into the tracks and trees then appearing again like tiny — but wise — guardians watching over you. Closer to home, readers may be familiar with the late Redfern Cat, Tiger to his friends, who lived on Abercrombie Street and greeted passing students with a meow and a leg rub, and

whose role has been since assumed by the equally ginger Whiskey.

Stray taps into this unique relationship between cats and humans, one defined by fascination and adoration. Media is only starting to recognise that people aren’t satisfied with simply seeing cats; they wish to experience them. Ceyda Torun’s award-winning 2016 documentary Kedi (‘Cat’ in Turkish) follows seven particular stray cats in the streets of Istanbul, each with a name and particular profession, personality, and character traits. TikTok creator @goldshawfarm offers users POV videos of his barn cats living on a duck farm. In seeing the little fluffy paws trotting along fences and across fields, it is freeing to feel as though you are pouncing and bounding around yourself. I’m envious of their daily lives that are both lively and serene, and it is comforting to watch them go about their adventures.

Stray truly is the culmination of humanity’s millenia long obsession with cats. In a world where even Hello Kitty isn’t a cat, Stray shirks persona and artifice, and goes all in on authenticity. While the game’s producer says they never intended to make a “100% cat simulator,” it’s safe to say that to anyone but a cat, they got pretty close.

Images courtesy of Annapurna Interactive

Images courtesy of Annapurna Interactive

PULP 33

Film

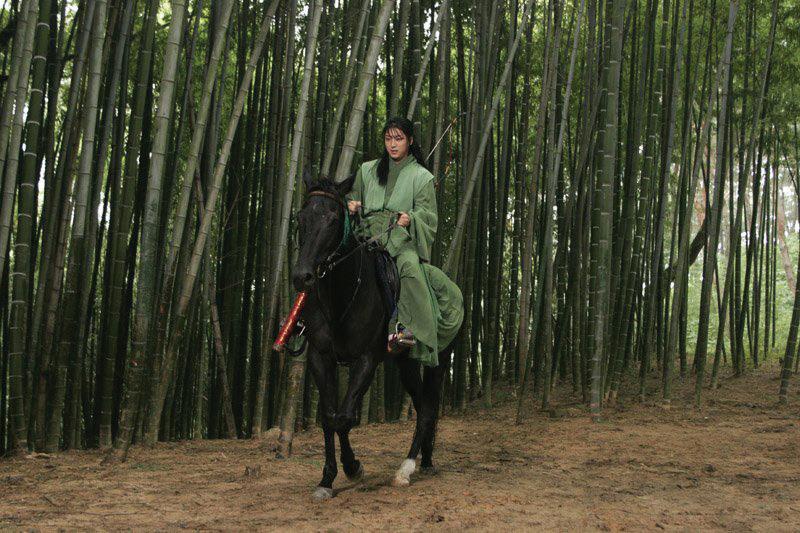

‘Reading the Room’:Emotions of the Korean New Wave

Architecture 101: Lotte Entertainment

Written by Claire Hwang

With the popularity of Netflix’s Squid Game, Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite and Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari, Korean media is gaining dramatic attention in the world spotlight. Despite this, only a select few break into the cultural zeitgeist and become international successes, while the vast majority of Korean classics remain dormant in obscurity.

Understanding this phenomenon requires a deep dive into the rich emotions of modern Korea (한국), romanised as Hankuk. Hankuk is composed of two parts — Han meaning the Han people (Koreans) and kuk meaning nation, thus, together, forming the Korean nation. However, Han can also translate to resentment and sorrow, ironically mirroring the traumatic history of modern Korea. Is most Korean media shielded from the global stage due to

the Koreans having too much Han?

Whether it be the collective trauma of colonialism, or the heartbreaking separation of North and South, the shared cultural and emotional imagination of Koreans has been reshaped around a multi-layered non-verbal form of communication. Eye contact, physical affection and double entendre have collectively formed a shared culture of ‘reading the room’. As such, there are many films that reflect this cultural minutiae and touch the hearts and minds of Korean audiences, but remain lost in translation when exported to other countries. While they may be a hit back home, they fail to find success beyond the domestic box office.

Lee Young-ju’s Architecture 101 has been lauded as a classic of the

The King and the Clown: CJ Entertainment

Korean romance genre as it follows the burgeoning love between two college sweethearts, Lee Seung-min and Yang Seo-yeon, shifting between the past and the present. Initially, they fall in love in their architecture class. However, a mistake severs contact, until 15 years later, when Seo-yeon requests for Seung-min to build her dream home in the present.

Despite the film garnering a domestic box office gross of $26 million and winning a slate of awards, it has failed to reach the same success overseas. Perhaps Western audiences may disregard it due to its perceived adherence to the trite separated lovers trope, resolving with the classic cliché of eventual reunion.

However, the portrayal of their relationship in the present — where they both understand that they

35PULP

The King and the Clown: CJ Entertainment

The King and the Clown: CJ Entertainment

36 FILM

cannot be together due to their own personal lives, despite their lingering feelings — is represented in a hyper-realistic manner through indirect dialogue. This resonated with domestic Korean audiences, evoking the dual nature of ‘han’ and the sorrow between individuals. This is reinforced in Suzy Bae’s pure portrayal of a bumbling first year college student, accompanied by Lee Je Hoon’s portrayal of a shy college boy who made the wrong choice. The multi-layered nature of their dialogue, coupled with their contrasting and misaligned eye contact, was not only endearing as a nostalgic reflection of first loves, but effectively evoked an implicit emotion amongst the domestic population, creating an internationally underrated hit.

Similarly, the historical drama The King and the Clown, directed by Lee Joon Ik and written by Choi Seok Hwan, showcases the close mateship between two street clowns — Jangsaeung portrayed by Kam Woo-sung, and Gong-gil portrayed by Lee Joon-Gi — who are skilled in tightrope walking. Performing a skit that mocks the court, they attract a lot of negative attention. However, the King is entertained by their performance, appointing the

two as official court jesters. With the King’s mental health faltering, he soon falls in love with Gong-gil who is renowned for his feminine looks, leading Jangsaeung to feel both jealous and concerned. Ultimately, the trio’s relationship between love, friendship and respect is tested as they are led towards their downfall.

Unlike Architecture101, which failed to receive any international presence despite its commercial and critical success, The King and the Clown managed to gain moderate momentum and international acclaim, winning the Jury Prize at the 2007 Deauville Asian Film Festival, as well as being South Korea’s submission for the 2006 Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language film. However, it continues to remain both underappreciated and unknown by the majority of the Western audiences, frequently missing from discussions of great Korean cinema. How can this be?

Park Chan Wook’s neo-noir Oldboy received international praise and popularity due to the exotic flow of its unravelling mystery, accompanied by its polished, wellchoreographed action sequences. Active verbal communication carries the plot, utilised in the frequent in-

person and telephonic interactions between the protagonist Daesu and the mysterious antagonist, who kept him in captivity for 10 years. In comparison, The King and the Clown utilised a multi-layered scheme of both verbal and non-verbal communication. Close mateship is portrayed through verbal means, whilst an essence of romantic feelings and emotions are captured through non-verbal eye contact and physical actions. Though the domestic audience were able to catch on to the non-verbal emotions, due to shared cultural experience in ‘reading the room’, this may have not resonated with wider Western audiences, thus leading to its underappreciation.

Multi-layered verbal dialogue, non-verbal communication; these domestic hits tapped into a shared experience and collective trauma that resonated with viewers in Korea. By unearthing and unpacking these films that have remained underappreciated in the West, hopefully you can be better equipped to explore the unique culture of ‘reading the room’ through implicit communication and its cinematic representations. As well as, perhaps form a new theoretical lens through which you can analyse film.

37PULP

Sex? In my city?

Written by Simone Maddison

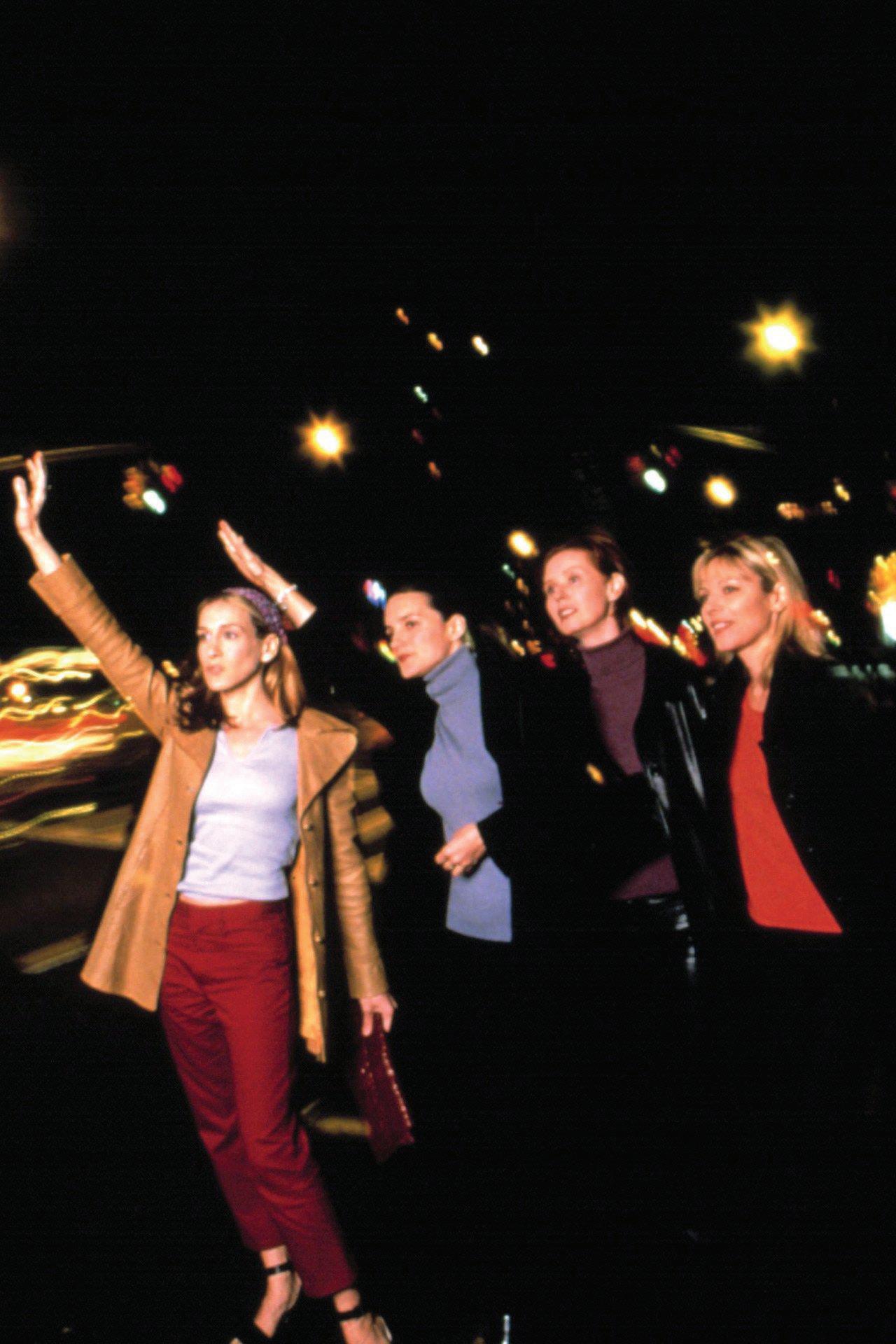

After many months of experimentation, I have discovered that Sex and the City (SatC) is best consumed late at night after either an unbearably long shift at one’s hospitality job or two generous pours of red wine over dinner with friends. I submit to this ritual at least three times a week, carefully propping my 13-inch laptop on the edge of my bed in pitch-black darkness. As the gentle HBO whoosh sounds, I am instantly transported to the New York City of 1998. And yet the countless half-hours I have spent with Carrie, Miranda, Charlotte, and Samantha are as much about their escapades as they are about mine — my bedroom, my body, and my boyfriends.

I found SatC at a time of heartache and transition, at the end of my first relationship. The love I had lost, that I could no longer keep safe but still wanted so desperately to hold, was channelled into onscreen romances with Mr Big, Aidan, Steve, and Trey. I assessed how I would react to a partner falling asleep during sex, if I could forgive infidelity, and what I would do if I saw my ex’s wedding photos in a Vogue editorial. I saw my frustrations towards men represented without overshadowing the benedictions of female friendship

and I tested relationships I’d never had. Despite the writers’ attempts to convince me otherwise, I learned that the life of career success and designer clothes I want is not synonymous with the loneliness into which I am terrified of falling.

But perhaps this is where SatC most ardently reveals that it is a product of its time and place. I may be constantly reminded of my CarrieCharlotte hybridity, now enhanced by the skill of chatting up bartenders and handling guys with funky spunk. Yet the simple fact remains that these characters will never know what it means to live and love in 21st century Sydney. Within these contested spaces, we may freeze-frame and pin-drop new meanings.

It is unsurprising that SatC’s timelessness is undermined by its outdatedness. The pilot episode opened with Carrie’s friend making ‘art’ from non-consensual sex tapes. Samantha’s respective AfricanAmerican and lesbian love interests were consistently fetishised and criticised by the other women.

On the whole, slurs like “tranny” and “Gaytown” were dropped so frequently that Sarah Jessica Parker apologised for “failing the LGBTQ+ community.” These examples hint at the white, heteronormative, and male

gaze that allowed Carrie to attack Big’s fiancée and Miranda to degrade ‘sexed-up’ women in LA.

But time has been distorted on a far more personal level. Watching six seasons in quick succession at my desk, dinner table, and damask armchair disrupted SatC’s pacing and impact. As well as being displaced by 30 years and 30,000 kilometres, I feel disconnected from the four protagonists because I lack their age and assurance. For everything Candace Bushnell has taught me, the gaps she left behind provide new opportunities for reimagined vignettes of a modern Australian SatC

The four women are as much New York as New York is them. Carrie’s Manhattan, coloured by mild neurosis and irreverent style, brings the urban landscape to life. Of course, the American and Australian east coasts share spectacular harbour views and an affinity for liberal feminism. But if New York is only defined by its concrete canopies and cosmopolitan cribs, then Sydney’s coolness is no different from the Hamptons’ relaxed elegance or the sunny shores of California.

38

FILM

The real difference lies in the romances Sydney and New York produce — and the types of lovers they are. With a change in host city comes a host of plot changes: Carrie’s inner-city brownstone becomes a two-room inner west studio, her rent increases so rapidly she must sell out to Newscorp to keep up, and she never meets Big because the arts do not mix with STEM. Miranda might be taken out to a pub, but she quickly learns that two dates do not a boyfriend make. Charlotte’s dreams of a Frenchminimalist holiday home in Byron Bay are rattled by the trials of a lacking ‘pick-up culture’, and even Samantha may be shocked to hear otherwise tabooed language like “cunt” thrown around the bedroom as casually as a sex toy.

Like Chanel handbags and Manolo strappy sandals, work and play also mix differently on Sydneysiders. I have not believed in saviour by male lovers, Anglo family traditions, and nuclear households since I lost my religion at age 12. The average Australian woman — who will only have one child, who is more likely than ever to never marry, and who enjoys a long history of contraceptive freedom — has certainly pushed the boundaries laid by SatC’s protagonists. Despite all my Sunday morning brunches and midnight taxis, my cultural core remains different. Out of New York in 1998 and Sydney in 2022, I know which city I’d rather have sex in.

39PULP

Literature

evergreen

Written by Amy Tan

we’ve walked here before, leaves torn astray, our mouths open, cascade catching morning’s dew, forgotten, asleep in the misty green,

our heads crowned, evergreen and proud, making night envious of our glamour and design,

bodies radiant, unpicked, unfettered, smooth, scarred, marked, wholly, beautifully our own, those worn-out slurs, crumble, burnt out, delirious, afraid and estranged to watch us weave our tale: the female gaze

PULP 41

“Where’s my legacygone?”: The chronic misrepresentation of poetGwen Harwood

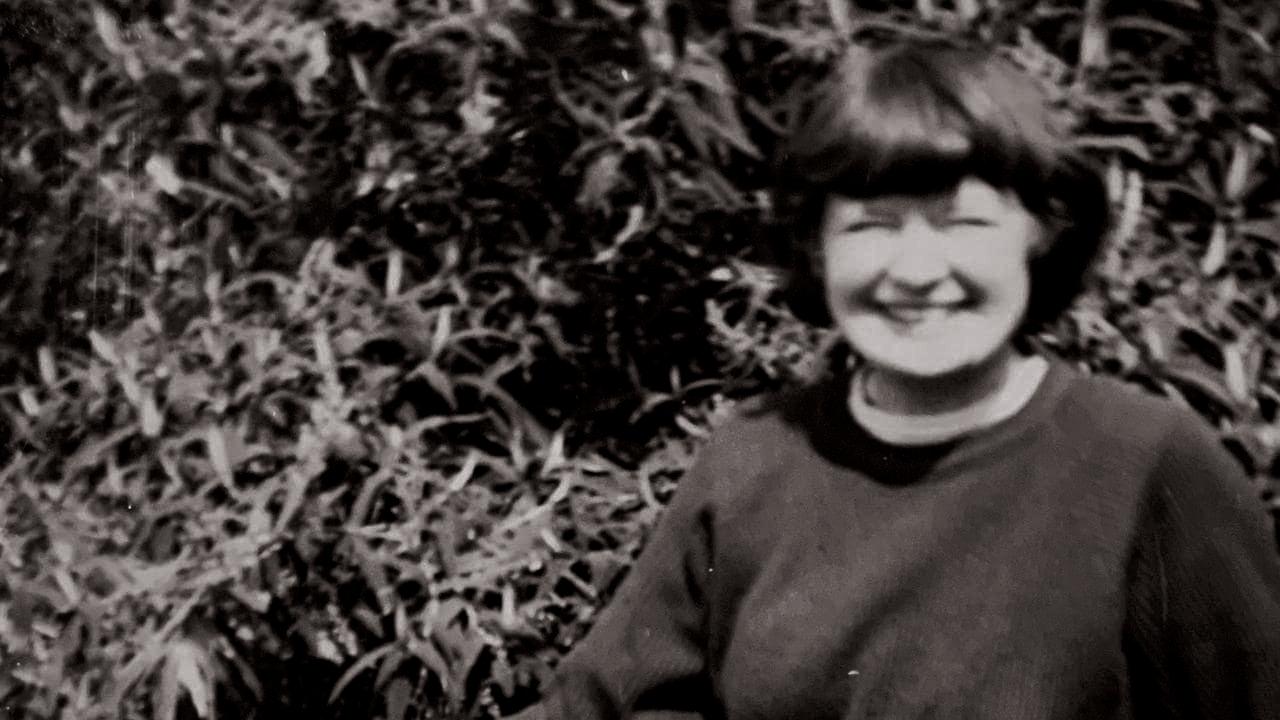

Written by Ariana Haghighi

Out of Tasmania’s Oyster Cove — where thickets meet rolling sea — poured lyrics and letters that have become canonical cornerstones.

Gwen Harwood, with a musician’s ear and a matrilineal fondness for poetry, penned poems from the 1940s to 1960s that left an indelible mark on the Australian literary landscape. Despite this, the media coverage of her character and work was often dismissive, inconsistent, and disproportionately low, symptomatic of her position as a female poet: in the eyes of the media she was housewife first, poet never.

Harwood fused concerns of time’s thievery and the vagaries of motherhood against a natural Australian backdrop. Her poems are windows into her untamed feminist views: armed with her words, she dismantled patriarchal structures. If you peer at her works’ surface, the themes of a fleeting childhood and her penchant for music shine through prominently.

In ‘The Violets’, Harwood sculpts

a churlish child who has just woken up from a nap, grumbling that during her short sleep, the horizon stole the sun from the sky. As her subject sobs, “Where’s morning gone?”, Harwood delivers a package of nostalgia and sentimentality to the reader, who is encouraged to reach into the past to revisit a mundane but powerful childhood moment.

When it comes to high-school and university curriculums, poems like ‘The Violets’, ‘Barn Owl’, and ‘Nightfall’ are repeat offenders — all lament lost time and the wistful revisitation of childhood memories. This was a key dimension to Harwood’s collection of works, but certainly not the only one. For too long, the strictures of educational curriculums and media depictions have neglected the shadowed faces of her prismed oeuvre: one being her dismemberment of narratives surrounding motherhood.

These narratives, peddled by patriarchal limbs, centre the experience of motherhood as

faultlessly glorious to restrict women to childbearing roles. ‘In the Park’ and ‘Suburban Sonnet’ offer a glimpse into her fiercely feminist values as she reveals the often bleak and gruelling reality of raising a child as a woman.

Harwood’s depiction of motherhood is honest, not horrifying. Dismantling key icons of sacrosanct motherhood including Madonna and Child, Harwood reveals the damaging effects of glorifying childrearing. The mother in Harwood’s poems is unprepossessing, stretched thin while child figures are fractious. To paint an authentic image of motherhood is to undermine the societal fiction that attests to motherhood as female self-actualisation and ostracises any woman who does not have a pictureperfect experience raising their child.

As well as her poems’ powerful content, Harwood navigated the publishing industry in a memorable manner; in the 1960s, publishing houses and journal editors were dominated by men and lined with

LITERATURE

42

privilege. Harwood’s character was feisty, her words silently raging against the machine. She wielded power in the publishing landscape with her use of various pen names. Delighting in deception, she created fictional alter egos to transcend the constrictiveness of the publishing industry.

She rocked the world of the Australian literary periodical the Bulletin in 1961, hoaxing the publication to fleeting delight. Concealed behind her male pen name, Walter Lehrmann, Harwood humiliated editor Donald Horne in response to prior rejection of her work. Harwood submitted two sonnets that acrostically smuggled in the indicting remarks: “SO LONG BULLETIN” and “FUCK ALL EDITORS”.

The next day, the words “Tas housewife in hoax of the year” were seared onto the front page. In the days that followed, Harwood’s hoax was constantly compared to the Ern Malley affair, a ruse where

conservative writers James McAuley and Harold Stewart created a fictitious poet to vex the editors of the Angry Penguins journal. However, contemporary poets and commentators, including A.D. Hope, constantly downplayed the wit of Harwood’s trickery, criticising it as “insignificant” compared to the impact of McAuley and Stewart. A large part of this criticism ran on gendered lines, influenced by their perception of a female poet.

We reckon with Harwood’s life and legacy again, as it has been thrust into the light with the publication of her son’s commentary in the Australian Book Review, ‘Gwen Harwood and the perils of reticence.’ Since her passing, there has been limited discourse on her legacy. The media’s memory of her remains dismissive, due to restricted access to her correspondence. The seeming reticence of her literary executor again belies her philosophy whilst she was

alive: one of forthcomingness and excitement to pen an autobiography. Her son’s commentary exposes aspects of Harwood’s marriage and her experience of coercive control. Although it does not paint a full picture of Harwood’s home-life and character, it chips away at the statue of truth.

Considering the contemporary media and societal reluctance to champion women and the arts, Harwood’s legacy may never be fully enlivened to the degree it deserves. As time passes, we may be granted glimpses of secrets untold; we can also bear witness to other apertures in her poems. There lies some beauty and responsibility in the mystery, as we are tasked with uncovering what has been buried.

PULP

43

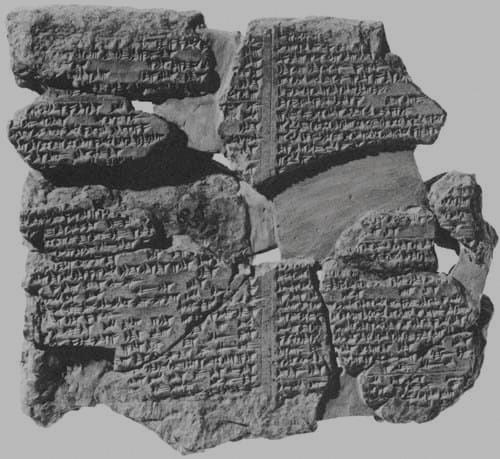

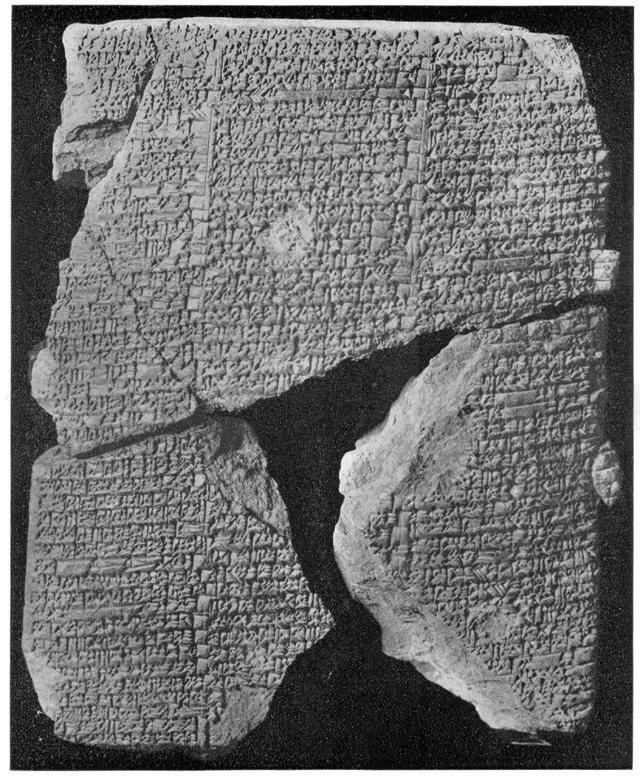

Gilgamesh and theInvisible Hand

Written by Amelie Roediger

“Before it was emancipated as a field, economics lived happily within subsets of philosophy — ethics, for example — miles away from today’s concept of economics as a mathematical-allocative science that views ‘soft sciences’ with a scorn from positive arrogance.” – Thomas Sedlacek

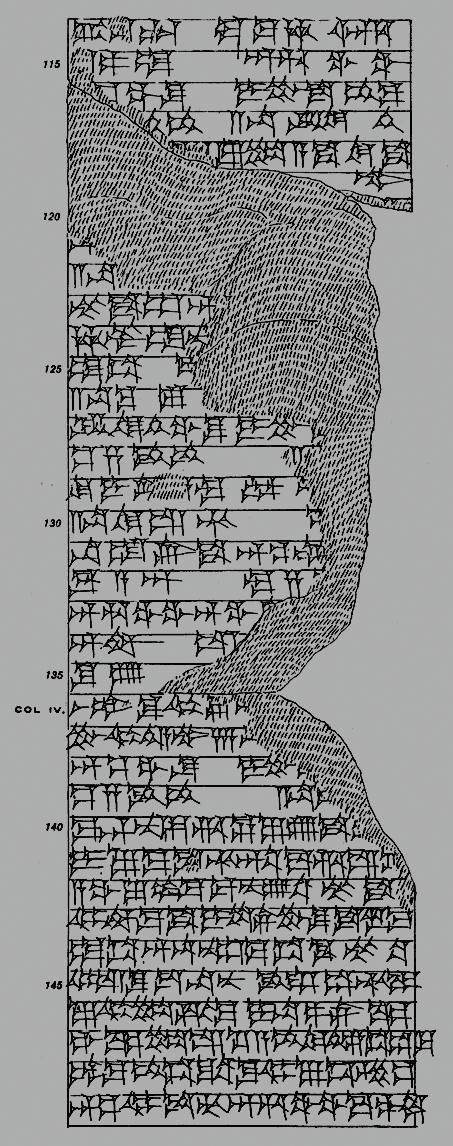

The Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh is one of the oldest written legends ever recorded, dating back to 2100 BCE. The cuneiform work tells the tale of the powerful king of Uruk, ‘Gilgamesh’, and his tyrannous exploits which ultimately give way to an era of laudable rulership.

Gilgamesh was a semi-mythic creature, two-thirds God and onethird man. As king, his leadership was marred by ceaseless war and an abuse of power, to which the people of Uruk pleaded to the Gods for help. In an effort to tame his tyranny, the Gods created Enkidu, a man-beast of

equal strength to Gilgamesh.

Enkidu represented an innate evil of society; he was uncivilised and embodied a wildness that Gilgamesh, as king, was obliged to tame. Gilgamesh succeeded on this front, taming Enkidu who was transformed into a noble and valiant friend of the powerful king. Where Gilgamesh’s rule previously incited outcry from the people, the taming of Enkidu softened his heart, and his kingship became exemplary. In this way, Enkidu also tamed Gilgamesh’s cruelty — as was the intention of the Gods. Enkidu dies in the prelude of

the epic but is arguably one of most important figures in the history of moral sentiments, and by extension, early economics.

Myths, legends, and religious tales are often dismissed as moral guides, for the most part relevant to the study of history and ethics.

In his book, Economics and Good and Evil, Sedlacek challenges this characterisation, proposing instead that such myths and legends are the roots of modern economic thought.

Economists predict market behaviour on the rationality of Homo

LITERATURE

44

economicus, a behavioural paradigm of humans as rational agents driven by self-interest — alike to Plato’s parallel Theory of Forms. Such agents embody greed, egotism, and a more broadly individualistic sentiment. But while these values align with the modern mechanics of capitalist markets, they appear at odds with the virtuous teachings of early moral codes. Or do they? At what point were these values accepted as cornerstones of economic doctrine? The answer may lie well before Adam Smith’s 18th-century Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Theory of Moral Sentiments is heralded as one of the first texts defining the social psychology of society on which Smith’s economic magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations, was founded. The Wealth of Nations is seminal to the theory of free-market economics and, regardless of the success, or abject flaws of the theory itself, has played a pivotal role in the formation of contemporary economic networks.

For Smith, allowing individuals to pursue their self-interests ultimately generates unintended greater social benefits. This is broadly known as Smith’s theory of the ‘invisible hand’ but essentially affirms the precept in the 4000-year-old epic of Gilgamesh; that the key to societal cohesion is to allow a modicum of ‘evil’ for ‘good’, ‘good’ being the development of society.

In the epic, Gilgamesh’s era of favourable leadership only begins after Enkidu — the wild spirit of evil — is tamed. Without the Gods allowing such evil to exist, the tyranny

of Gilgamesh would have endured. Similarly, the ‘evil’ selfish greed of Homo economicus is considered a necessary counterpart to the invisible hand of the market, which purportedly gives rise to greater social benefit. Notably, this link hinges on just one interpretation of the legend but nevertheless raises an interesting discussion on moral approbation and disapproval across time and cultures.

Economist George Akerlof strongly advocates for narratives to be seen as a tool humankind harnesses to decode the complexity of societies. However, sometimes we cling to theories of global orders and forget these theories don’t always lead where they should. Perhaps this is the case with the modicum of evil, or maybe the answer lies later in the epic itself.

PULP 45

Recess

Riding down a shiftingstreet in Harris Park

Written by Nandini Dhir

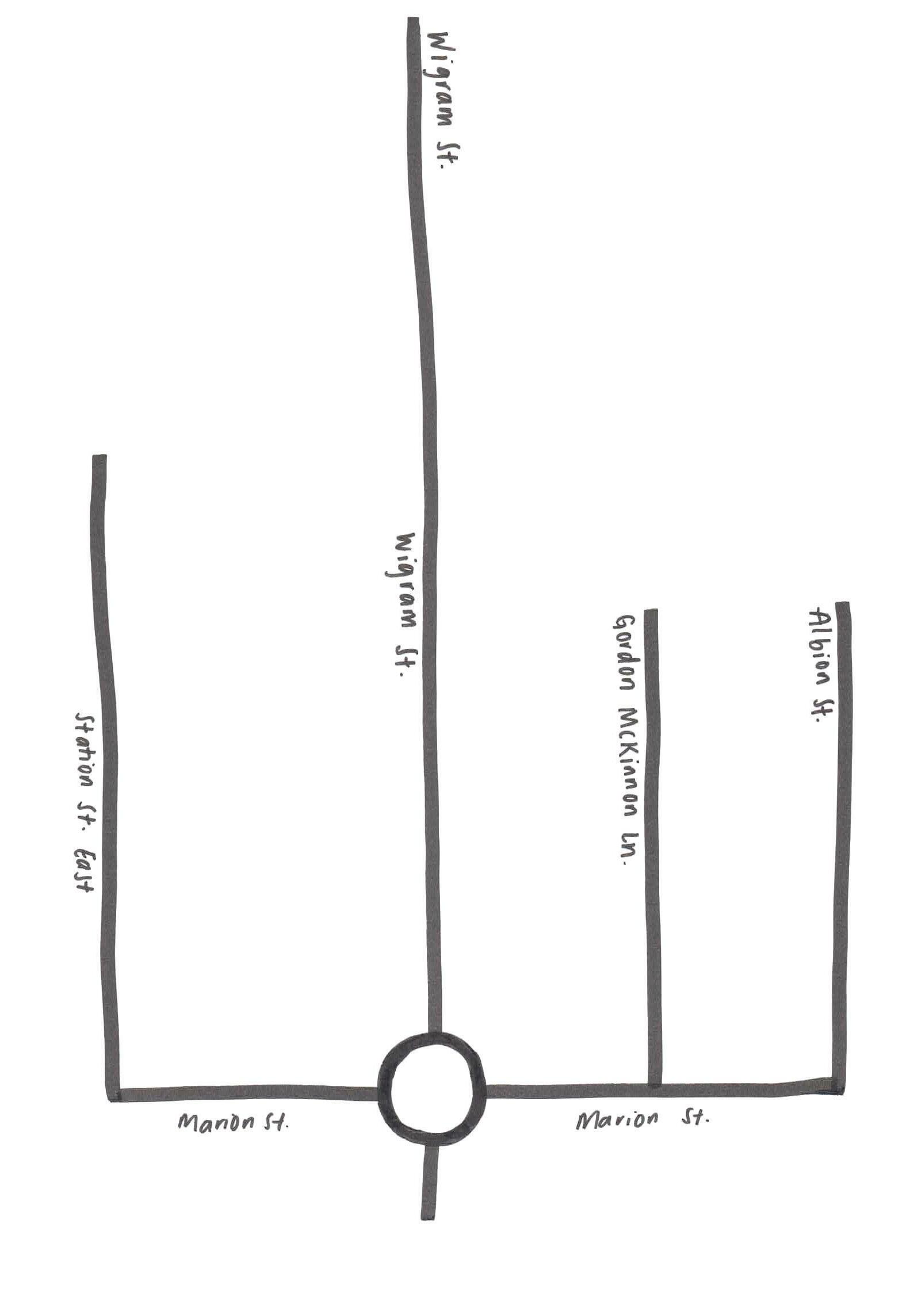

On a Kmart bike and wearing a styrofoam helmet — its sole purpose being to avoid fines rather than head injuries — I follow my dad south down Wigram Street. Suddenly, we’re in India. A 10-minute bike ride from home, we fill ourselves up with golgappa, aka pani puri, before choosing what restaurant we’ll order choleh bhatura from.

Brimming with South to North Indian cuisine, Wigram Street in Harris Park has earnt the name Little India. But with a couple Nepalese businesses, Pakistani owners, a Vietnamese bakery1, and the iconic Lebanese cafe, Little India is not just for Indians. This pocket of restaurants, street food vendors, ethnic grocers2, a laundromat, health practitioners — and an absolute

disregard for any road rules — creates a home away from home for the dense migrant population of South Asian diaspora in Harris Park.

For the average visitor to Little India, the options are overwhelming. You enter at the corner of Hassle and Wigram Street, instantly facing traffic, pedestrians on the road, Bollywood soundtracks competing with the neighbouring restaurants, and realise that about 90 per cent of these restaurants have the same menu.

I’ve pedalled down Wigram Street over many years. First in the baby seat, then training wheels, on my big girl bike, and in the car on rainy days. Restaurants come and go, seamlessly replacing the previous business’ facade with new signage

and unique branding. However, the remnants of the former small business linger; laminate flooring, a bright feature wall, a TV playing the latest T-Series clips, and an identical shop layout.

I’ve also seen the corner shops, small takeaway restaurants, and grocers that have lasted their lease term long enough to see it renewed – and long enough for me to become a returning customer. But if the key to Indian cooking is ghee, what’s the key to a lasting business on Wigram Street?

To start with a family favourite, one where almost every second Father’s Day – and the majority of my grandparents’ birthdays – are held, is Taj3. Loved by my father and

PULP 47

RECESS 1 2 3 4 56 7 8 9 10 48

his father, perhaps for their entirely vegetarian menu, samosa, and bread pakora that consistently satisfies a craving, Taj can easily go unnoticed at the far end of Wigram Street — except for the week before Diwali.

In the lead up to the biggest religious festival of the year, Taj becomes solely a sweets shop. Tables and chairs are pushed to the back wall, creating a makeshift buffet-style floor plan where sweets of all kinds are weighed and sold by the kilo. Unfortunately, no bread pakora or samosa are available at this time of year.

A few years back, Taj opened an extension restaurant, Taj Bhavan, a couple stores down. As loyal customers to Taj, naturally we found ourselves seated in Taj Bhavan soon enough. It felt more like a restaurant than a takeaway store, with a similar menu, just a few dollars more. Fairly empty for the Friday night my family had dinner there, we weren’t overly surprised to find out that Taj Bhavan closed down several months later. Though it was a nicer space and the food was the same as its smaller takeaway store, Taj Bhavan is no more, while Taj still stands strong today.

Perhaps Billu’s4, the restaurant that brought Wigram Street into the limelight, has the answer. Boasting rickety tables and chairs, laminated menus, and stock standard customer service, Billu’s is known for their well cooked meat and generally enjoyable curries. With the occasional rocket kulfi stand (Indian ice cream shaped in a long cylinder with a cone end resembling a rocket) out the front, Billu’s has helped Wigram Street earn the Little India label, attracting customers well beyond the South Asian demographic of Harris Park.

Last year, Billu’s expanded, opening a second restaurant location in Bella Vista, Indian Street Food by Billu’s in Circular Quay, and Spiced by Billu’s in Barangaroo.

These three major expansions give Billu’s a more fine dining edge, serving a different plate of customers and tapping into the experience of restaurant dining as opposed to good meat and a standard menu. Billu’s also opened a fifth venue, Glassy Junction, directly opposite their first location in Harris Park. Featuring Indian dishes that are general crowd pleasers and a bar fit out, Glassy Junction closed as quickly as they opened. Even Billu’s, in the hot seat of Harris Park, couldn’t replicate their success in Little India again.

Indian Chopsticks5 is one of few fusion places in Little India that has been around for years. Serving Indo-Chinese dishes, their menu differs from the majority of those on the rest of the street, and has remained the same as long as they’ve been open. Indian Chopsticks is a personal favourite of mine, for no particular reason aside from the fact that I’ve eaten there countless times and their vegetarian chow mein is consistently fulfilling. Chatkazz6, on the outskirts of Little India opposite the train line on Station Street East, is another fusion restaurant that has become incredibly popular over the years, regularly filling their car park space — even on weeknights — with makeshift tables to meet the demand of a younger customer base.

A newbie on the map is Shri Desi Dhabha7, owned by the Shri Refreshment Bar8 at the corner of Gordon McKinnon Lane and Marion Street. Famous for their paan (betel nut) stall and morning paranthas for the international students of Harris

Park, this success was a sign of something bigger. When Al-Wadi Charcoal Chicken opened up just off Wigram Street, on the corner of Marion and Albion Street — with a new store fit out and glossy branding — only to close down months later, Shri Desi Dhabha became a mainstay. With some of the cheapest thalis (a meal of naan, rice, selection of curries, yoghurt, pickle and a sweet) in Little India, they’ve become a popular spot for a quick and cheap lunch.

As for India Bazaar9, directly opposite Taj, it’s one of the few grocery stores that have stood the test of time, with the neighbouring grocer having changed owners and names over the years. It’s a tiny store with single file-sized aisles, and loose dal and chana at the back of the store. SweetLand Patisserie10 with their Lebanese sweets and cakes is another small business that has endured on Wigram Street, sufficiently serving the demand for baklava and fruit cake.

If there’s one thing I’ve noticed from the restaurants that fall victim to the cycle of closing businesses, it’s that a clean shop with great customer service means nothing to the visitors of Little India. At times it can be the places that don’t seem to stand a chance upon first opening, but then you find yourself there as a regular before it becomes a habitual visit. As restaurants and take away shops continue to open and close, I’ll continue to ride around Harris Park and try to eat at the new places before they shut down. Otherwise, I’ll remain loyal to Taj for the mango lassi and Indian Chopsticks for the vegetarian chow mein

PULP 49

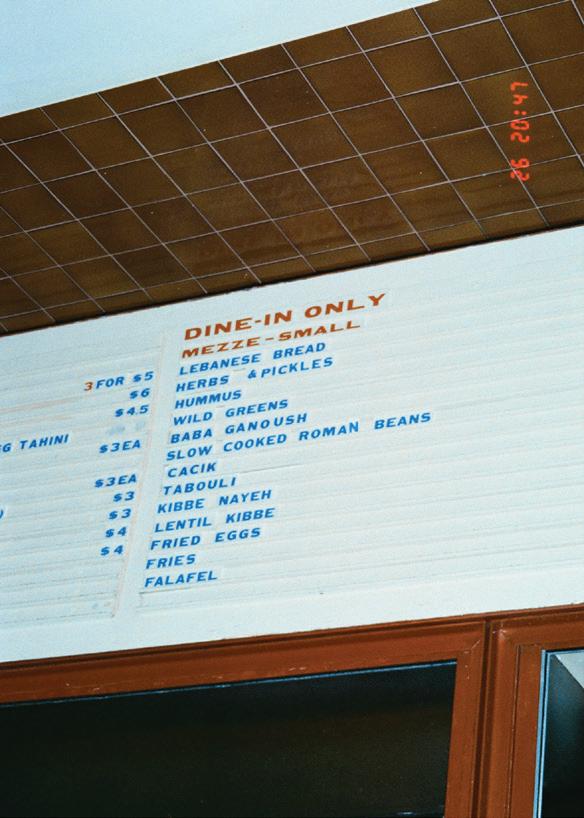

t o it t ’ s )( y v c i o n t h e p a r k ) ( l i t t l e f e l i x ) ( . . . . . . . . . b a r t o p a )( v i ( ) RECESS50

The Merivale Monopoly

Written by Patrick McKenzie + Bonnie Huang + Ariana Haghighi

The El Loco cantina, tucked away on Sussex Street, offers you a visual feast even before you reach for the menu. You scan the fluorescent stools and tablecloths, assuring yourself that this was better than waiting for a seat at Bar Totti’s. You rejoice in your visit to Mexico, validated when your taste buds are sated with braised beef tacos. Your pocket gets lighter and merry laughter carries you along your odyssey as you snake through drinks at The Royal George, more drinks at Felix, and finally, the ivy Pool Club. The tap of your credit card becomes a metronomic, discordant hum that pinballs amongst the other patrons. Water sluices your body the next morning, rinsing off sweat, regret, and an overdrawn account.

When it comes to restaurants and nightlife venues, Sydneysiders are spoilt for choice. No two nights are the same — the sheer permutations of options ensures a fresh experience every time. Yet, when you indulge in a night out, all too often you are an unwitting marionette puppeted by the hand of large hospitality groups — with a high chance of it being one conglomerate in particular, Merivale.

Merivale possesses a discreet chokehold on Sydney’s hospitality industry. While familiar to some, few are aware of the full extent to which

the company controls more than 80 well-loved venues from South Sydney to the furthest reaches of the Northern Beaches. Although diverse in nature, they relish in a shared veneer of high-class, visual curation, and pseudo-multiculturalism.

Most Merivale venues are geographically concentrated in Sydney’s CBD and Eastern Suburbs, bringing greater swathes of the ‘Merivale magic’ to upper-end communities. Beyond the CBD is a completely different ballpark; despite the occasional franchise, restaurants in Western Sydney are predominantly independent or family-run.

Part of Merivale’s allure to Sydneysiders is its capitalisation on something of a ‘glamorous city life,’ providing carefully curated dining experiences — an accessible luxury for those who can afford it. Photos of Totti’s rustic woodfired bread with Kusama-like char are seared into the collective consciousness of many Sydneysiders, especially young people. Instagram feeds are flooded by panning shots of the ivy pool club, and spreads of burrata, prosciutto, and olives are inescapable on stories and profile grids alike. Merivale is successful because it delivers — patrons can trust in adequately delicious food, treat-yourself vibes, and guaranteed Instagram-worthy aesthetics.

Sitting at the figurative and literal top is CEO Justin Hemmes, notorious for his business flair, flamboyant ‘playboy’ antics. Tabloids broadcast his every move, showcasing extravagant parties and new relationships aboard yachts, on the harbour, on his private island in far North Queensland, and during lavish dinners at his own venues.

Since its founding in 1957 by Justin’s parents, John and Merivale Hemmes, the company has kept its finger on the pulse, trailblazing in fashion as the first store in Australia to sell the miniskirt. Coming under Justin’s helm in 1997, the Merivale name quickly became ubiquitous in the hospitality and entertainment sectors, and the business began to scale.

Hemmes has garnered reverence and admiration from “corporates and slimy entrepreneurial types,” says Jake*, a former Merivale employee who has worked across several flagship venues within the ivy Precinct.