Innovation in architecture isn’t always as obvious as doing something with a new material just because it’s technically possible. 75 years ago, our practice was founded in response to the speed at which the past was being demolished and replaced, and grew out of an instinctive understanding that if we didn’t start protecting, adapting and enhancing our heritage, it would be gone before anyone realised the consequences.

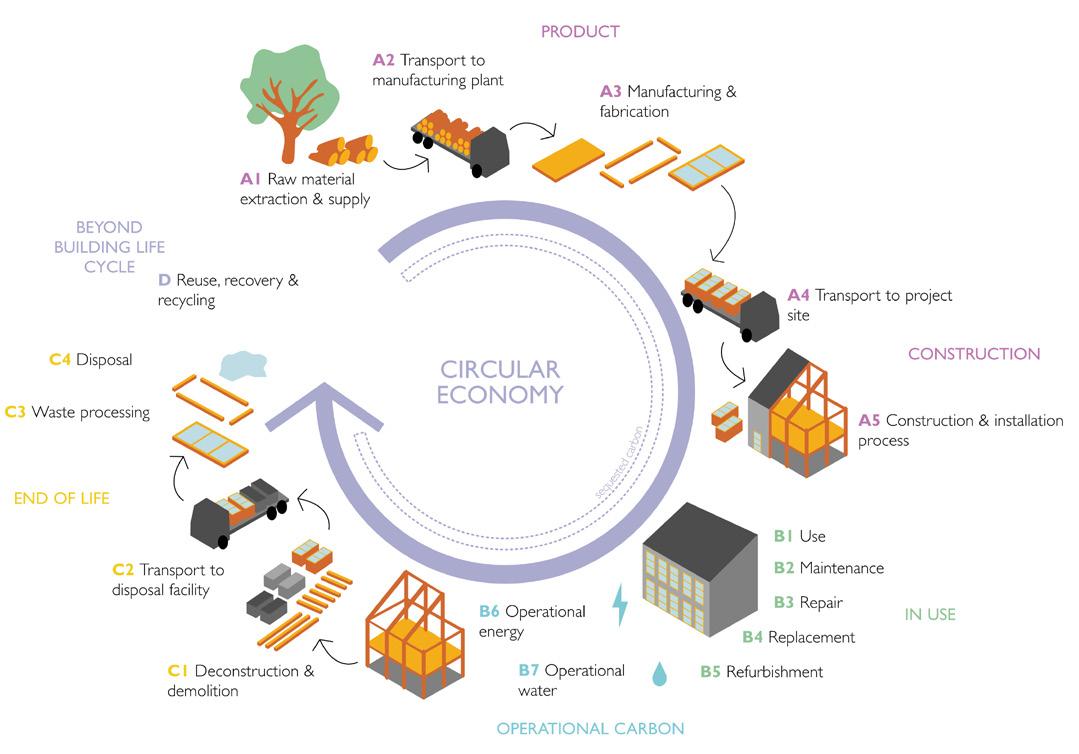

Today, embarking on the worst existential crisis the world has ever faced, we are focusing our attention on a circular economy for materials. There is a fallacy that materials can disappear without a trace when a building is demolished. The most creative response is not to keep building new, but to be inventive and innovative with what already exists. As the world’s largest practice working in conservation and heritage, Purcell has long held a belief that reuse is the key to unlocking some of the most profound questions around our future and the climate emergency.

Refurbished mill machinery at Sacrewell Watermill, Peterborough

© Purcell

/ Louis Sinclair

Refurbished mill machinery at Sacrewell Watermill, Peterborough

© Purcell

/ Louis Sinclair

What began as a niche strand of architecture is rapidly becoming mainstream. Adapting old buildings for new uses, extending, and modernising them to make them relevant in use, accessible and environmentally sustainable is becoming the first choice, ahead of a build-new approach that has dominated British architecture since the Second World War.

Whilst there is often a perception that listed buildings are at odds with a sustainable, low-energy future, the core principle at the heart of conservation is the responsible stewardship of our inherited world. It is intrinsically linked to a regenerative future, one which can support planetary health and conserve our natural resources, whilst simultaneously protecting our greatest architectural treasures.

In the context of the climate crisis, what may once have seemed the opposite of innovation, and the antithesis of progress, can now be considered a future-orientated approach. The actions of this generation could not matter more, and the role of conservation in architecture - which is more about the future than it is the past – forms an essential part of the solution.

In their book, Ecological Design, Van der Ryn and Cowan asserted that the environmental crisis is a design crisis. It is a consequence of how things are made, buildings are constructed, and landscapes are used. In 2020, human activity, including the production of concrete, metal, plastic, bricks and asphalt, brought the world to a crossover point where anthropogenic, human-made mass – driven mostly by enhanced consumption and urban development –exceeded the overall living biomass on Earth – including plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi. 2

As a society, we have been conditioned to see the construction of buildings and infrastructure as an inherently positive thing. Illustrations of bright yellow diggers and bulldozers in children’s books tell us from the youngest age that building things is positive, knocking things down is developmental, and digging things up is human nature. Political campaign slogans regularly promise to “build, build, build”, “build back better” or “build a brighter future”, because building is progress and growth. Building is prosperity.

We consider the full life cycle of our buildings, from raw material extraction to reuse and recovering at the end of a buildings life

But as a sector, the built environment is responsible for almost 40% of global greenhouse gas emissions3 , 50% of extracted materials4, and one third of global waste streams5, and in the UK we demolish around 50,000 buildings a year 6 .

As built environment professionals, we must be honest with ourselves about the negative effects our sector has had, and continues to have, on the planet. We need to rapidly shift away from the take, make and throw away cycles that are ingrained within our economy, and acknowledge that we have enough ‘stuff’.

We need to nurture our natural resources and see our built environment as a carbon store and a resource bank, taking joy in mending, caring for, and prolonging the life of the things we already have. By creatively unlocking the potential in our existing buildings we can provide long lasting, resilient, and beautiful places, whilst preserving our natural resources and limiting greenhouse gases. The beauty of this is that we can put the past to good use, and we have been doing this with our built heritage for centuries.

The core values of sustainable and circular design are rooted in our history, and they can help shape and inspire modern methodologies and innovations, providing vital lessons for how we can tackle the climate emergency.

The principles of repairing, recycling, refurbishing, or repurposing materials and structures, all aim to keep materials in use for as long as possible at their highest value, and this is not a new concept. When things are in abundance, people easily accept a wasteful and exploitative attitude. Yet before the advent of fossil fuels, this abundance was not accessible for individual societies, and so a core practice of a circular economy was adopted as the only economically viable way to operate. In the heritage sector, painstakingly salvaging materials for reuse is commonplace, but seeing existing buildings as a valuable bank of materials is still not mainstream.

Before fossil fuels, we built out of materials that were locally sourced, and readily available. Materials were of the earth and lasted far beyond today’s default design life of 60 years. We built using a simple pallet of materials, with components that were easily isolated, removed, repaired, or replaced. In contrast, the complex materials and systems we use today combine many different materials, often glued together, and each with a different life span, not easily isolated and replaced.

Buildings of the past relied on low tech, passive solutions to ensuring occupant comfort levels, like local sources of heating that heated people not the space, thermal mass that could regulate temperature and humidity, and passive forms of ventilation and cooling.

Most historic buildings still around today have survived by virtue of their ability to adapt, as society has adapted, and human needs have changed. We are surrounded by buildings that have been transformed to suit a different use, be it Georgian town houses now used as offices, warehouses converted to apartments, or a power station transformed into a mixed-use neighbourhood. We have been adapting buildings to suit our changing lives and needs for as long as we have constructed buildings.

Part of the reason we continue to extend the life of our built heritage through adaptation, is because it brings people joy. Our built heritage is a fundamental part of our cultural identity, inherent in our understanding of a place, its history, and its social story.

In building conservation, we measure the evidential, historic, aesthetic, and communal significance of a place, analysing value in a way that goes beyond monetary considerations and cost per square meter. We value our historic buildings and places, and as a result impose greater restrictions and protections on them because we see the societal benefits they have. This approach to non-economic value provides essential lessons in how we can move away from our current growth-led economy which prioritises the prosperity and wealth of a few, and instead look to prioritise human and planetary health, and the value inherent in what we already have.

The core principle at the heart of heritage conservation is the responsible stewardship of our inherited world. This philosophy is intrinsically linked to a regenerative design approach – one which can support planetary health and conserve our natural resources.

The perception that historic buildings are at odds with a sustainable, low-energy future is facilitated by the idea that energy efficiency measures might cause ‘harm’ to historic fabric. For example, double-glazing replacing original windows, visually intrusive solar panels, or external wall insulation covering original features. However, any ‘harm’ must now be weighed against the risks of inaction. A sustainable, decarbonised, and low-energy future does not necessarily mean harm to the historic fabric of a building. On the contrary, it can mean the difference between giving a historic building a secure, functioning, and viable future, or risking it degrading and becoming obsolete.

‘Constructive conservation’ describes an approach to building conservation that sensitively manages the changes and alterations necessary to ensure the future of a historic building, and its continued use and enjoyment, for the long-term. For many years this approach has been used successfully to justify changes relating to accessibility or health and safety. We need to start treating the climate emergency with the same urgency we treat other matters of life safety and acknowledge the wider public benefits that come from adapting our historic buildings for a changing climate. Constructive conservation offers a perfect template for how we can do this, sensitively managing the changes our built heritage desperately needs to prepare it for a decarbonised and climate-resilient future.

The Centre of Refurbishment Excellence (CoRE) was a pioneering project to transform a disused Grade II listed pottery works in Stoke-on-Trent into a national centre of excellence for low energy building retrofit, with exhibition and conference venues.

Completed a decade ago, this locally iconic and culturally significant site provided a test bed for how energy efficiency measures and sustainable technologies (including ground source heat pumps, solar panels and rainwater harvesting) can work in harmony with historically significant and protected buildings.

Ledston Hall is the first Grade l listed building in the country to install double glazed windows, which involved a careful consultation process with Historic England.

The recently completed ‘Common Ground in Sacred Space’ project at Newcastle Cathedral, ten years in the planning, is part of a series of phases to pave the way for this Grade I listed landmark to become operationally net zero carbon. It is the first Grade I listed cathedral to install heat pump technology combined with an efficient underfloor heating system. The work involved lifting over 100 ancient stone ledgers which were carefully restored, catalogued, and re-laid.

These projects are the result of forward-thinking clients willing to challenge the business-as-usual approach. The continued use of existing buildings, coupled with measures to improve energy efficiency, reduce carbon, and build climate resilience, is a global priority.

To meet net zero targets, we must be radical with our built heritage; it has a crucial role to play in our collective futures. The sooner we acknowledge and celebrate the synergies between building conservation and a regenerative future, the sooner we can all enjoy the benefits.

1 S. Van de Ryn & S. Cowan, Ecological Design, 2nd Edition, Island Press, 1995¹

2 E. Elhacham, L. Ben-Uri, J. Grozovski, Y. Bar-On & R. Milo, Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass, Nature, 2020

3 World Green Building Council, Bringing embodied carbon upfront: Coordinated action for the building and construction sector to tackle embodied carbon, World GBC, 2019

4 European Commission, Buildings and Construction, European Commission Website, unknown

5 N. Miller, The industry creating a third of the world’s waste, BBC Future Planet, 2021

6 W. Hurst, Demolishing 50,000 buildings a year is a national disgrace, The Sunday Times, 2021

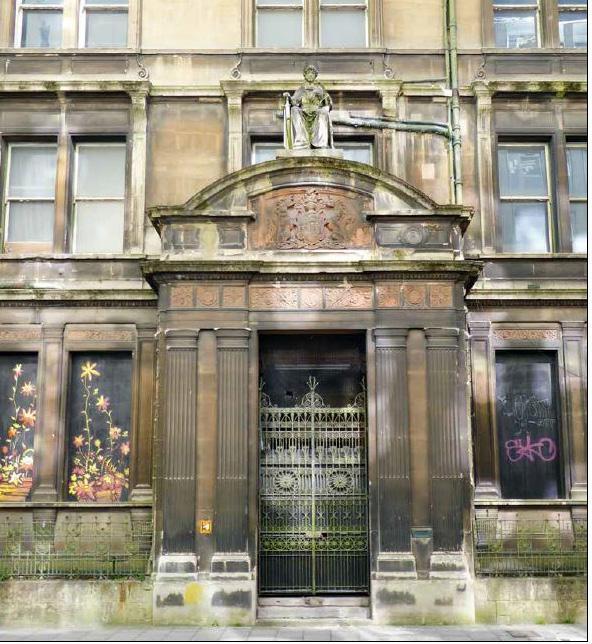

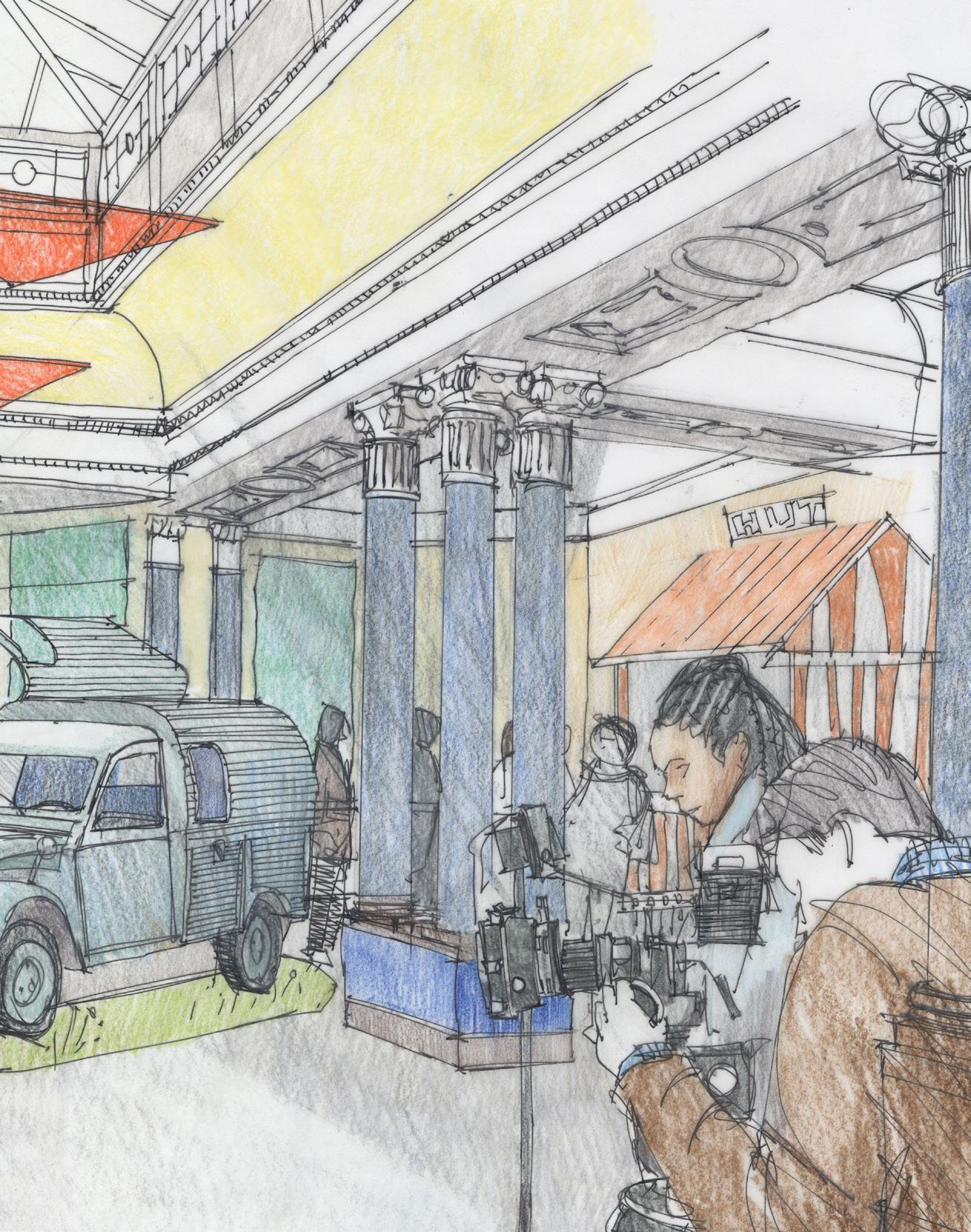

Conservation architecture is about more than restoring the fabric of a building and can be instrumental in helping to shape the identity and spirit of a community. As architects we strongly believe that successful projects evolve out of a collaborative process with our clients and local communities, to understand how buildings can have a new relevance for wider and more diverse engagement than their original purpose.

Our restoration of Holyhead Market Hall in Wales returned a previously derelict building to the community as a modern, sustainable centre, housing a library and flexible event space. The project won the Community Social Impact of the Year award.

Holyhead Market Hall, Wales has been transformed by Purcell into a community hub

Holyhead Market Hall, Wales has been transformed by Purcell into a community hub

At its most engaging, heritage is a touchstone connecting us with the past in a way that doesn’t limit or undermine the future uses of a building. A recent example of this has been our restoration of Boston Manor in Hounslow, a Grade-I listed manor house. With support from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the property has been carefully restored and adapted to transform a dilapidated building into a community asset and a creative hub for emerging artists and designers.

While the house has been returned to its historic splendour, the old service wing, which once housed facilities such as the laundry and dairy for the manor house, has been reimagined as light and airy flexible maker-spaces, part of which is now occupied by the Jimmy Choo Academy, enabling young talent from less advantaged backgrounds to learn creative skills and crafts.

The exterior of Boston Manor House, restored by Purcell

The exterior of Boston Manor House, restored by Purcell

Nowhere is this spirit of physical, social, cultural, and environmental restoration encapsulated more clearly than in the reimagining of Alice Billings House. It is an inspiring example of Local Authority and the Creative Land Trust coming together to provide much needed investment in local communities, realising their vision for workspaces and affordable studios for artists and creatives to collaborate and grow with the building, continuing the story for the next generations. When one purpose for a building ends, it’s not the end of the road, it’s a turn of the page.

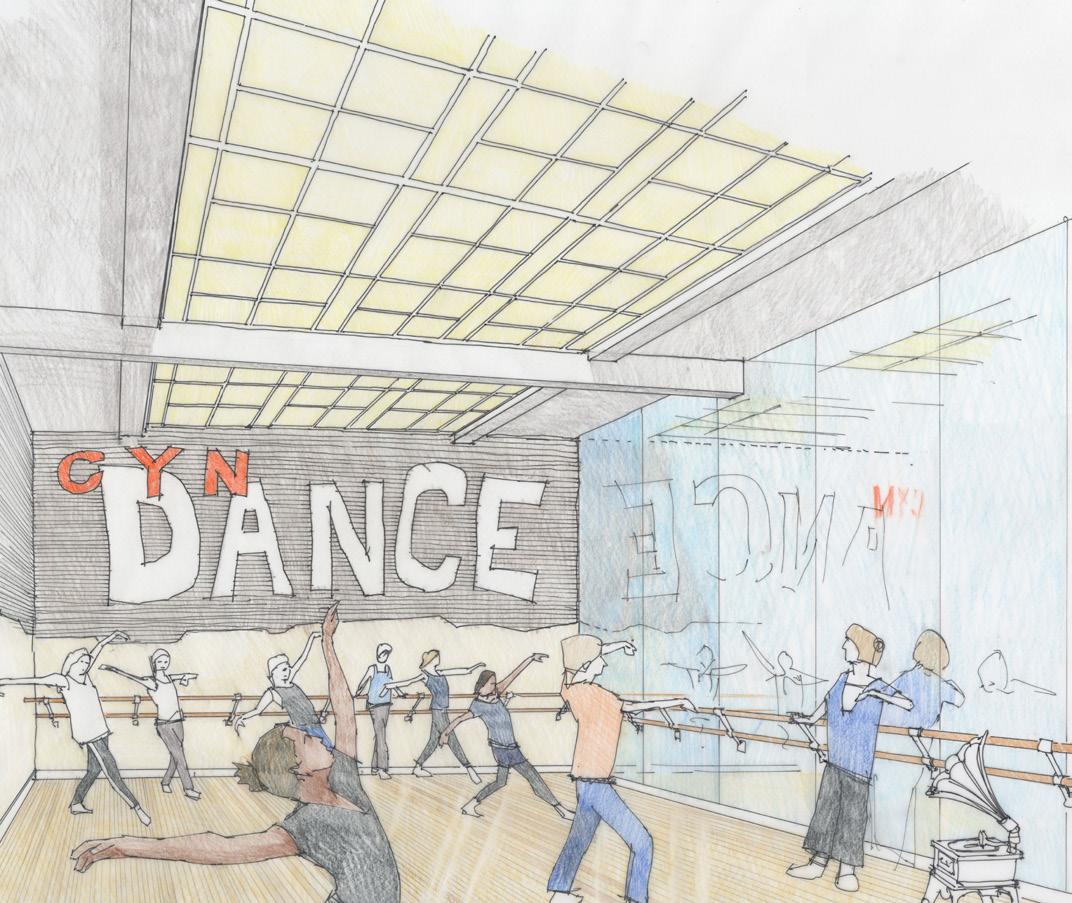

Concept sketches of our proposals to transform the building into studios for artists and creatives

Heritage plays an important role in bringing heart and soul back into our towns and cities. Older buildings connect us to our past to the craftsmanship and care that went into crafting them. People naturally feel a greater emotional relationship with this characterful architecture than with identikit developer-led buildings.

Britain has lost a lot of traditional building skills, resulting in a disconnect between craftsmanship and architecture. There are exceptions, and some very successful new buildings and districts that will last for generations, but these are not the norm. Much post-war architecture is dominated by developers for whom profit is masqueraded as progress, in place of an agenda to prioritise the wider social value and impact on the community and planet, and it demands the question – why do we build?

Concept sketches of 12 Claremont, showing our plans to transform an old telephone exchange building into an exclusive, creative and affordable community hub

As a practice we are immensely proud that many of our projects come from grassroots communities who have identified the need for a home for specific needs. In Hastings, East Sussex, Purcell are working with the Heart of Hastings Community Land Trust to transform a building that once housed the south-east’s first telephone exchange. The plan is to turn it into an inclusive, creative and affordable neighbourhood hub for working, living and community action. Inclusivity and accessibility are critical components of the design we are developing, catering to the needs of the project operator chosen by the client –Project Artworks, a local collective who collaborate with people who have complex support needs.

The debate around contested heritage often impacts conservation architecture more than contemporary buildings. There are uncomfortable questions being asked around collective assumptions about some of our greatest public buildings, but what comes out on the other side of those conversations is a more open and transparent assessment of the past that will hopefully equip us to navigate forwards with greater clarity, enabling us to restore social balance to heritage. Ultimately, these are buildings we should all be free to enjoy on our own terms.

The approach taken by the Manchester Museum, for which Purcell has just completed a new extension to house their Southeast Asian collections, is not just a physical upgrade, but a cultural and ethical one. As an institution, deaccession was seen as an opportunity to broaden the diversity of the collections and the spaces needed to embrace a new era.

Manchester Museum, Manchester

© Purcell / Richard Kalina

Manchester Museum, Manchester

© Purcell / Richard Kalina

The museum’s understanding of their obligation to serve the whole community was embedded in Purcell’s brief to create a gallery that accommodates a broader programme than simply displaying objects – a proper space for people with severe disabilities and picnic areas that don’t feel like an afterthought for those who aren’t able to buy lunch in the café. These small acts of change can make a big difference to who feels welcome in our cultural institutions. We have upgraded the entrance, so everyone gets the same visitor experience no matter what their level of mobility. It’s a way of understanding the loss of colonised artefacts and the diversity in our communities as an opportunity to expand the offer in ways that resonate and connect more authentically with where and who we are now, socially, environmentally and ethically. If I had to sum up what heritage is – it is the continuing history of everything.

“The transformation of the former central police station into a world-class centre for heritage and arts has created a vibrant new civic space in the heart of the city’s central business district…[tackling] a complex site with multiple layers of history… enhancing its legibility and opening it up to the public.”

— UNESCO award Jury

As Heritage Consultants and Conservation Architects, Purcell worked collaboratively within the international design team, educating, guiding and informing the conservation and evolution of this nationally significant landmark.

16 historic buildings were adapted across the six-acre site - three of which are Declared Monuments – and two new buildings by Herzog & de Meuron introduced, with new wayfinding routes, entrances and enhanced open spaces.

Formally opened on 25 May 2018, Tai Kwun had its 1,000,000th visitor within the first four months.

Purcell led the restoration, conversion and extension of the derelict Redruth Brewery, now considered a beacon for heritage-led urban regeneration and know as Kresen Kernow.

The project has been recognised across the industry and by the public with awards including the RIBA South West Award 2021, Civic Trust Award and a Planning Award for Design Excellence.

Set within the UNESCO ‘Cornish Mining’ World Heritage Site, Kresen Kernow (Cornwall Centre) Archive and Local Studies Centre brings together the largest collection of historical documents and objects chronicling the people, places, history and culture of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly over the past millennium.

To house 14 miles of shelving containing over 1.5 million records and 850 years of history, the design team challenged traditional concepts of a staid archive by uniting distinct historic character and fabric with imaginative contemporary and accessibility-led design features. Kresen Kernow’s value reverberates around its local and county-wide community, safeguarding the identity, culture and history of Cornwall.

Purcell led the landmark restoration and renewal of Newcastle Cathedral, delivering both a civic and sacred space fit for the 21st Century and beyond, underpinned by sustainable interventions and an expert understanding of the historical and social significance of the Grade I-listed place of worship.

Underfloor heating was also installed beneath the reconfigured nave floor, removing the costly and inefficient need to heat the entire, echoing space within the Cathedral for visitors. This gentle ‘heat sink’ is powered in part by air sourced heat pumps hidden atop the new lobby. New facilities, including a lift,

have been introduced with as little impact to the Cathedral fabric and exterior as possible. A converted basement frames modern new amenities, forestalling the need to extend the Cathedral’s footprint, while the new Lobby expands access and sustainable design.

“Purcell has been involved in the largest refurbishment since the works that took place here in 1882, when St Nicholas’ became a cathedral.

At its heart, the project has been about creating a sustainable future for our magnificent Cathedral, celebrating its elegance, but also energising its mission to welcome visitors of all faiths and none into our story.”

— The Very Revd Geoff Miller, Dean of Newcastle

Purcell were engaged to expand the existing facilities and renovate the courts to provide arts and creative facilities for disadvantaged young people in Bristol, retaining the unique interiors as inspirational and stimulating spaces for creative engagement