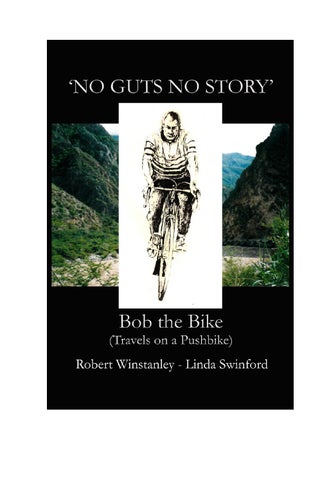

‘A man in his sixties decides to cycle thousands of miles alone with just a map. His journey goes through many countries.

His story is true, brave, touching and funny.

Birmingham-born and growing up in the 1930s Robert Winstanley has loved cycling since aged eleven when he owned a bike with no wheels.

He cycled his first long distance in his teens, to Wales with a pal. Now eighty, he still enjoys a fifty-mile day trip on a pushbike.

‘No Guts, No Story’ is about the years and the distances ‘Bob the Bike’ spent in his sixties on his bicycle.

Bob had many amazing encounters, narrow escapes and romantic interludes on the way.

Why he set out and what happened will fascinate you.’ Linda Swindford