10 minute read

Changing our approach to station design

JOHN HARDING

London Bridge station.

Introducing a service design process into the early RIBA stages provides a strong bedrock on which the project can meet its potential.

For around fifty years, the rail industry has implemented design processes that are not always aligned with how to address the needs of the user in the early design stages. And these needs are changing, arguably faster than our infrastructure design can keep up. But by learning from other industries and injecting service design thinking early on into our station and depot designs we can make modern, accessible and inclusive spaces that satisfy the requirements of customers, operators and maintainers.

Service design thinking puts user and customer needs first to create or improve a service which speaks to their needs, and is both technologically and economically viable. According to Tim Brown of IDEO, an organisation that has been practicing human-centred design for 40 years, design thinking engenders innovation by drawing “from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success”.

IDEO’s five-stage process (observe, synthesise, generate ideas, refine, implement) has become a best practice standard worldwide. We are already seeing this being developed in front line services in the UK, such as NHS Digital, and local authorities are drawing on the expertise of researchers, technical architects

0. Strategic Definition 1. Preparation and Brief 2. Concept Design 3. Developed Design 4. Technical Design 5. Construction

and business analysts to meet customer and community needs at each step.

How can we apply service design thinking to rail stations?

Fellow station designers or architects will be familiar with the RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) and GRIP (Governance for Railway Investment Projects) processes that govern the way we approach design. They are the backbone upon which we deliver vast and complicated buildings and infrastructure and are supported by a range of legislation and design standards, such as the processes stemming from the Equalities Act 2010, that underpin how we make design choices.

6. Handover Close Out

7. In Use

i. Observe ii. Synthesise iii. Generate Ideas

However, these guides and requirements are not a means to an end.

Observational analysis is rarely employed at the formative stages of design for rail stations. We tend to rely on broad surveys to understand the needs of passengers, station staff and operators. While useful, these surveys are not nearly granular or nuanced enough to determine what a human-centred design should look like.

It was this lack of behavioural data that led me to conduct my own observational studies to understand people’s relationship with stations in 2010 - before I had come across service design thinking as a concept. Through customer questionnaires, workshops and visual assessments of Canary Wharf station, a relatively modern station serving the Jubilee and DLR lines, I learnt how people can experience the same environment in very different ways.

The overriding lesson for me was that the stations we create need to be much more intuitive, and give much more consideration to how people encumbered with unwieldy items like prams, heavy luggage and shopping, and how people of different abilities, such as wheelchair users, navigate through the station. We do not need to wait until the building is completed to understand how the people that will use it will be

affected. Instead, we can

observe

similar stations and identify, at the earliest stages, how the experience of customers, staff and maintenance workers, and how the problem of crowding, will be affected by the way in which the circulation spaces, lifts and escalators are arranged.

Synthesise to inspire new ideas

Our stadia, retail hubs and airports, even our urban highways, provide great examples of effective humancentred design - from moving around the building to accessing amenities. Airport designers, for example, have adopted a people-centred approach, as anyone who has used the large lifts at Heathrow’s Terminal 5 will know. For those with mobility issues, sensory impairment and for many others, not having to jostle one’s way onto a busy escalator with luggage is a big deal.

Traditionally, station designers have underestimated the potential for lifts to move people vertically through a station, relying more heavily on escalators, which tend to represent accident blackspots and pedestrian pinch points, especially when stations are busy. But large, airport style, walkthrough lifts really can provide serious capacity and congestion solutions, and contribute to more efficient management during emergency situations.

It was with this in mind that we successfully redesigned ten underground stations in the early concept stage, to increase inclusivity five-fold without increasing the cost or size of the stations.

Another example

of where station

designers can

apply more pragmatic solutions are station toilets - they often receive the score lowest in railway customer satisfaction surveys. There are plenty of reasons for this, including condition and cleanliness, their suitability for people of all abilities, the availability of cubicles, and baby-changing or family facilities.

In a recent major new station design, the ‘synthesise’ stage enabled us to incorporate ideas from modern office buildings to present an alternative design that answers all the main dissatisfaction points above, in this case replacing traditional gendered toilets with selfcontained cubicles, complete with hand washing facilities, leading off from the main corridor. These will provide a more comfortable customer experience, reduce problem queuing, and mean that only single cubicles are taken out of operation for cleaning and maintenance.

Our redesign also ended up reducing the space of toilet facilities by 25 per cent, an unexpected benefit for the client!

Refining the design

The ‘designer’s toolkit’ that IDEO’s Brown refers to as an aid to innovation, opens the door to much more integrated and inclusive station and depot design. With Building Information Modelling (BIM), designers can present a ‘single source of truth’ to clients and other disciplines involved in the project, promoting a more thorough understanding of every nook and cranny of a

The typical toilet arrangement has changed little over the past decades to reflect changes in society, as case 1 shows. Team London Bridge.

Direct access toilets replace traditional gendered toilets with self-contained cubicles, improving levels of comfort and convenience.

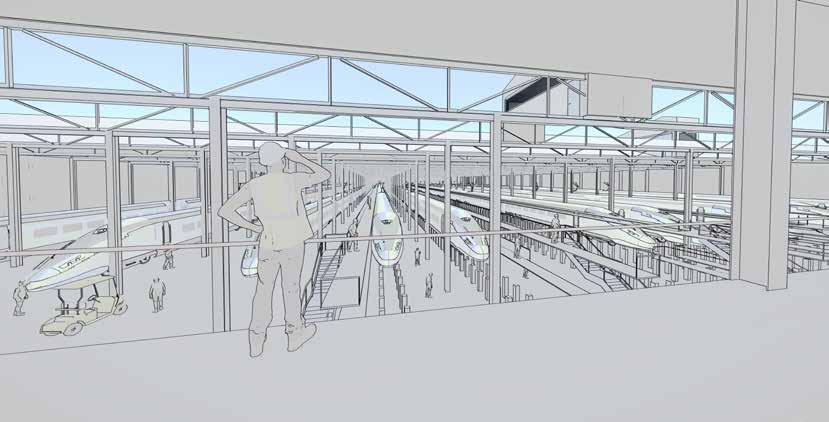

VR headsets enable all disciplines to integrate with the final design, for example clarifying the layout to communications or MEP teams. project, however complicated. And with augmented and virtual reality (VR), we are enabling non-technical people to experience our designs before they are even built. My architect colleagues Julia Gomez de Terreros Rider and Nicole Bego have been combining BIM with VR to present an accessible and clear understanding of the impact of our designs. “We have been using VR to bring BIM to life”, says Nicole. “Stations, depots and railways present a complicated environment, full of technical requirements and involving many factors, from the functionality of the train and comfort of the passenger to wayfinding, and how users, staff and maintainers will navigate. It’s hard to convey all of this on a 2D schematic the size of a small town; experiencing it via a VR headset is night and day!” This technique has been applied to various major station and depot projects by our team. Referring to the toilet redesign above, Nicole continues: “We wanted to demonstrate to the client the real user experience, comparing the old design with the new - would they feel comfortable and relaxed or hemmed in and stressed? The VR headset goes on and you can see they really get it!”

On a depot design, this combination of BIM and VR is helping to bring operational efficiencies. Julia says: “Video ‘walkthroughs’ give station staff a realistic depiction of what their experience will be like. As well as helping us iron out any creases prior to construction, by recreating the station for the people who will populate it - the fire officers, maintenance and office staff, cleaners and drivers - we can make sure it is operationally ready from the get go, and that things like evacuation routes are clearly understood.”

And it’s not just interior layouts that are being finessed. The team is planning to use augmented and virtual-reality tools to enable the local community to experience the impact of the construction of large infrastructure on their environment. Again, Nicole believes that the offer of a virtual tour in three dimensions provides greater assurances and understanding than a drawing ever could.

“We can use VR to assess the visual impact of a large depot on users and stakeholders and address concerns with such factors as the height, massing and materials used in the final design,” she explained. “It will also enable us to come up with some mitigations to lessen the impact even further.”

Inclusivity baked in Navigating a busy underground station can be stressful, especially when it’s unfamiliar. For example, the elderly, those with learning difficulties or physical disabilities, or families with young children can find the peak time rush scary - even traumatic. This is as true now as it was when I did my

research on Canary Wharf nearly ten years ago. The challenge remains for station designers to make these busy and often crowded spaces inclusive for everybody. That means creating a space that is welcoming, not intimidating, and one that works for everyone.

Fortunately, how we embed inclusivity into our designs is getting more sophisticated. Agent-Based Modelling (ABM), for example, is a 3D-tool traditionally we use to gauge a station’s crowdedness by simulating the movement of people in a virtual, rendered landscape. As part of the ‘refine’ process, our novel application of ABM has helped us identify existing design limitations that could inhibit movement - detailed heat mapping clearly demonstrates potential conflicts between lift and escalator users and those alighting or boarding the trains. We can then demonstrate significant reductions in the number of people per square metre in and around these traditional blackspots.

Ultimately, we delivered a station design that was empirically more inclusive - in this instance, we more than doubled lift space capacity, increasing the number of passengers using the lifts from 10 to 25 per cent, and grouped escalators together to improve pedestrian flow and reduce the likelihood of accidents.

To create spaces that are truly inclusive, designers need to put themselves in the position of all users. It’s not just about practical convenience, it’s about equality of experience. My challenge as an inclusive designer is taking what I know about a station - its capacity, predicted traffic flow, train dwell time, gate throughput - and intuiting how someone other than an able-bodied, sixfoot-plus man like me might interact with that environment. This is a serious issue that goes far beyond the discomfort of not being able to find a loo! For example, what constitutes a dangerous

space to me might differ dramatically from that of a woman travelling alone late at night. Building on safe-by-design, diversityimpact assessments, and other baseline guidance, this thinking needs to be at the forefront of every design development.

To be inclusive means much more than simply factoring checklist items into our designs; we need to consider more nebulous aspects, like vulnerability, and our perceptions of it. Service design thinking is one way we can incorporate the needs of actual end users into our designs early on.

We need to get serious about designing spaces that are fit for everybody. Service design thinking can help us focus on usability, which asks us to consider how to improve inclusivity, develop new ideas and implement those ideas using trusted techniques.

If we can develop buildings that are intuitive to the human experience and will meet the needs of society now and in the future, then we will be doing our job.

Lift

Exit

Exit

John Harding is technical director architecture, major and international projects at WSP.

Agent-Based Modelling helped identify pedestrian pinch points and improve wayfinding on a new underground metro in the Middle East. 3D walkthroughs enable future station operatives to hit the ground running as soon as the construction is ready.