8 minute read

Becoming not to Be: Identity and Place in Manuel Mathieu’s Bennett

Duvalieristes or Noiristes (Haiti’s Black political elite), this lighter-skinned class that Bennett belonged to had previously been the rivalry to Duvalier’s father, François Duvalier (Papa Doc)4 during his presidential reign (1957-1971). Bennett, moreover, was a divorcee and interpreted by the wide majority of Haitians to be “too ambitious, too promiscuous, too smart, and too liberal,” making her an undesirable state bride.5 Duvalier’s mother, grandmother, and associates echoed these sentiments as they all opposed the marriage, viewing it as a threat to the Duvalier regimes.6 Bennett and Duvalier’s union thus shocked and angered the Haitian public, contributing to what some scholars have deemed the ultimate demise of the Duvalier dictatorship.7 The couple’s later corruption and money embezzlement, which resulted in their eventual exile from Haiti, only added to this disdain for Bennett as a national figure.

In Mathieu’s painting, Bennett embodies many representations: she encapsulates the nation’s colourism and class;8 she symbolizes the state’s late twentieth-century wealth, power, and extortion; and, building off this last representation, she is associated with the horrific atrocities committed by both François and Jean-Claude Duvalier. Between the two men, tens of thousands of Haitians lost their lives in political conflicts, governmental massacres, and calculated killings.9 Mathieu has direct ties to these presidential terrors, having had a grandfather on one side of his family serve as a colonel in François Duvalier’s military and members of his family’s other side killed while fighting against the government.10 Despite having only been an infant when Jean-Claude Duvalier was overthrown (1986), the Duvalier eras are vividly present in Mathieu’s life as depicted in Bennett and some of his other Haitian-focused work.11 By using the popular culture image of Bennett, Mathieu resituates his family into these complex histories of Haiti’s past—a past already filled with political crisis, state tragedy and human loss. Exposed as a result are the collateral damages and colonial legacies of Haiti, where Mathieu inserts himself, repurposing the narrative.

For Mathieu, locating an identity is not found in distinct and defined places.12 As repeatedly described in his public interviews, he does not seek out an identity or a definite understanding of his place within a certain time and space. Alternatively, he aims to locate a sense of himself, somewhere.13 It is an uncertainty that he seeks to garner from his work, in a mystical and spiritual approach: “where you are experiencing something and it gets to you... it feels like something is happening. I want to dive into that.”14 Stuart Hall’s theories of cultural identity serve as a productive framework to study Mathieu’s ideological style. Interpreting identity as a “production,” something that is undergoing continuous remodeling and reprogramming, Hall refutes the notion of identity-making as a constant or as being capable of being completed, and instead argues for its ever-evolving properties.15 Hall understands cultural identity as a “matter of becoming as well as being.”16 Identities do not reach a certain point where they become static and absolute. They are in constant motion and flux, subject to the unceasing forces of “history, culture, and power.”17 In the work of Mathieu, we can see how his trajectory for self-discovery is mobile and unfixed as he plays with history and memory. Particularly, in Bennett, Mathieu repurposes history to comment not only on a popularly-remembered moment in Haiti but also to bridge connections between him and his ancestral home. As a result, he explores his unstable or uncertain relations to his identity and place living in the diaspora. Bennett, alongside Mathieu’s other historycentric work, demonstrates an effort to bring memories and past experiences into the present, paralleling an attempt to “become” rather than solely “be.”

Mathieu’s work has recently considered the bodily trauma he experienced after being involved in two nearly fatal car crashes. Struck by vehicles in London and Montreal in a span of two years, Mathieu suffered a concussion, a broken jaw, black eyes, and lost his vision and memory for a short period.18 Enduring these injuries, Mathieu detailed in a 2019 interview how these physical wounds created new avenues in which to “deal with his mental scars.”19 As Connor Garel notes, Mathieu’s work does not try and sensationalize trauma. Instead “he paints the aftermath, interprets the feeling…[working] in a world of sensations.”20 Mathieu’s physical wounds have become extensions of inherited lingering strains from his country, family, and home. Already inscribed into the body, histories of trauma become accentuated by these physical injuries. Mathieu’s technical practice emphasizes these wounds; his material mark-making, creating thick and thin surfaces of heavy wet paint with agitated and temperate gestures, evokes physicality, embodiment, and sensuality.21 In Bennett, his storytelling becomes enmeshed within the active movement of painting where historical and bodily scars collide, prompting new spaces of intimate confrontation between him, his past, and the anticipating future.

The diaspora has long been conceived as a constantly-changing space—in influx and subject to the forces building up the new world that greets diasporic communities.23 Self-identifying within these convoluted spaces, therefore, becomes complex and sometimes challenging. Josephine Denis writes how “the [diaspora] is constantly rearranging itself; waving off a sea of definitions, descriptions, identifications; becoming[…]a place that built itself up with ideas of purity and separation in the name of “order”.24 Denis concurs that the diaspora can be the simultaneous inhabiting of multiple spaces. Evident in Mathieu’s works is his movement between several territories, where shared histories and embodied traumas linger throughout. Growing up in Haiti where identities are pluralistic and complex due to its saturated colonial and transnational history, Mathieu has had to navigate many different geo-spatial plains. His fixation with Haitian temporal moments, therefore, provides some grounding in these shifting places.

Antonio Benítez-Rojo has described the Caribbean as a consistently shifting and self-renewing body, contending that the region is “constantly [regenerating] itself through fragmentation, dislocation, interruption, and instability.”25 BenítezRojo’s structuring of the Caribbean as continuously mutating is constructive in understanding Mathieu’s work. Mathieu’s artistic practice sees him explore chronic familial wounds in memories that are complex, messy, and sometimes indistinguishable. For as he states “I don’t even know what I am looking at. It then becomes a process of adding which then adds to myself.”26 Continued processes of reworking, rebuilding, and renarrating help construct Mathieu’s place and belonging in the spaces he resides, becoming the architecture of an ever-fluctuating identity.

The requirement to adapt as an immigrant in Canada forms new layers inside Mathieu’s manifestation of identity. In referencing his work, Mathieu has described how he is in a “constant [navigation] between two legacies [Western and Haitian],”27 how he draws from both cultures from vastly different geographical domains to create hybrid, fluid interconnecting networks. Being a Haitian immigrant living in Quebec, Mathieu has grown up in a spatial setting that possesses its own compound and racialized systems. Throughout the twentieth-century, immigration from Haiti to Quebec was extraordinarily high, with thousands of Haitians moving to the

French-speaking province, particularly due to the French empirical connections shared between the two states. Unlike citizens from Anglo-speaking provinces or other countries, French-Canadians viewed Haitians as distant family members, linked together “by a special bond” formulated by their inherent association to French civilization efforts.28 Although French-Canadians repeatedly used the familial analogy in reference to Haitian immigrants, Haitians were never seen as “equal” to them. Rather, French-Canadians saw them as “child-like,” “deviant,” and “uncivilized”, in need of the help of the Quebec state.29 For as Sean Mills describes in A Place in the Sun: “Haiti as a parallel society upholding French civilization and Haiti as an infantilized Other… were bound together by the metaphor of the family, linking Quebec’s international presence to its internal social history.”30 Haitian immigration to Quebec has played a large role in the province’s cultural, social, and political history, with

Haitian-Quebec citizens having become drivers of political and social change within the traditionalist province.31 Despite Mathieu’s rising levels of success, it is crucial to consider the climate surrounding his artistic development that pushes him to live as an outsider, leaving him to navigate through a world he is excluded from yet praised under limited conditions.

Considering the place Mathieu’s work takes up in a contemporary Canadian art historical context is noteworthy. Unfortunately, the state of relevance for African Canadian art history has only recently been deemed to be a more serious academic and scholar-worthy field, with art historian Charmaine Nelson taking the lead in this necessary endeavour. The erasure of Black artists has left multiple gaps within the general timeline of Canadian art history, let alone in a Black Canadian art history. In the case of Mathieu, there is a designation of Haitian identity. Using Bennett as a subject reveals to viewers individual narratives and memories within the Black community. Different from the rest, Haiti is the only country in the Caribbean to gain independence against colonial rule by enslaved peoples (1804). As the world’s first Black Republic, Haiti developed a divergent narrative compared to the rest of the Caribbean. Since the country’s sovereignty, Haiti has held a target on its back from colonial powers in addition to falling victim to ignored crises. Like many countries in the Caribbean, Haiti is left to fend for its own livelihood and survival of their narrative.

For the future of art and identity, Mathieu fulfills the concerns of urgency for change. His passion and devotion in exploring identity vouch for the revelations of erased histories. In this case, Black narratives within western landscapes are either underdeveloped or unheard of. Only recently has the awareness of African-Canadian art and identity become one of academic notice. Despite the recent surge in appreciation of African-Canadian art and identities, there still remains a lack of recognition for the distinction between groups within the Black community more generally. With his repertoire, Mathieu subscribes to the recovery of untold expressions and works towards formulating these distinctions.

As exemplified in Bennett, Mathieu ventures on a journey of self-discovery, not just for himself but also for his ancestral roots. By taking back agency from a historical narrative of colonial threats, he allows himself the space and creativity to process new ways of self-identification. Through his painterly recollection of Michèle Bennett, a place to heal and move through inherited scars of the past emerges in an endless, lifelong process of becoming. Although recent efforts have started to decolonize the national attempt to maintain ideologies that equate Canadian identity with Whiteness, there is still a long road of rediscovering and re-learning the role and identity of Black Canadian Artists in this country, one that Mathieu is currently paving.

Nathalie Sereda-Bazinet

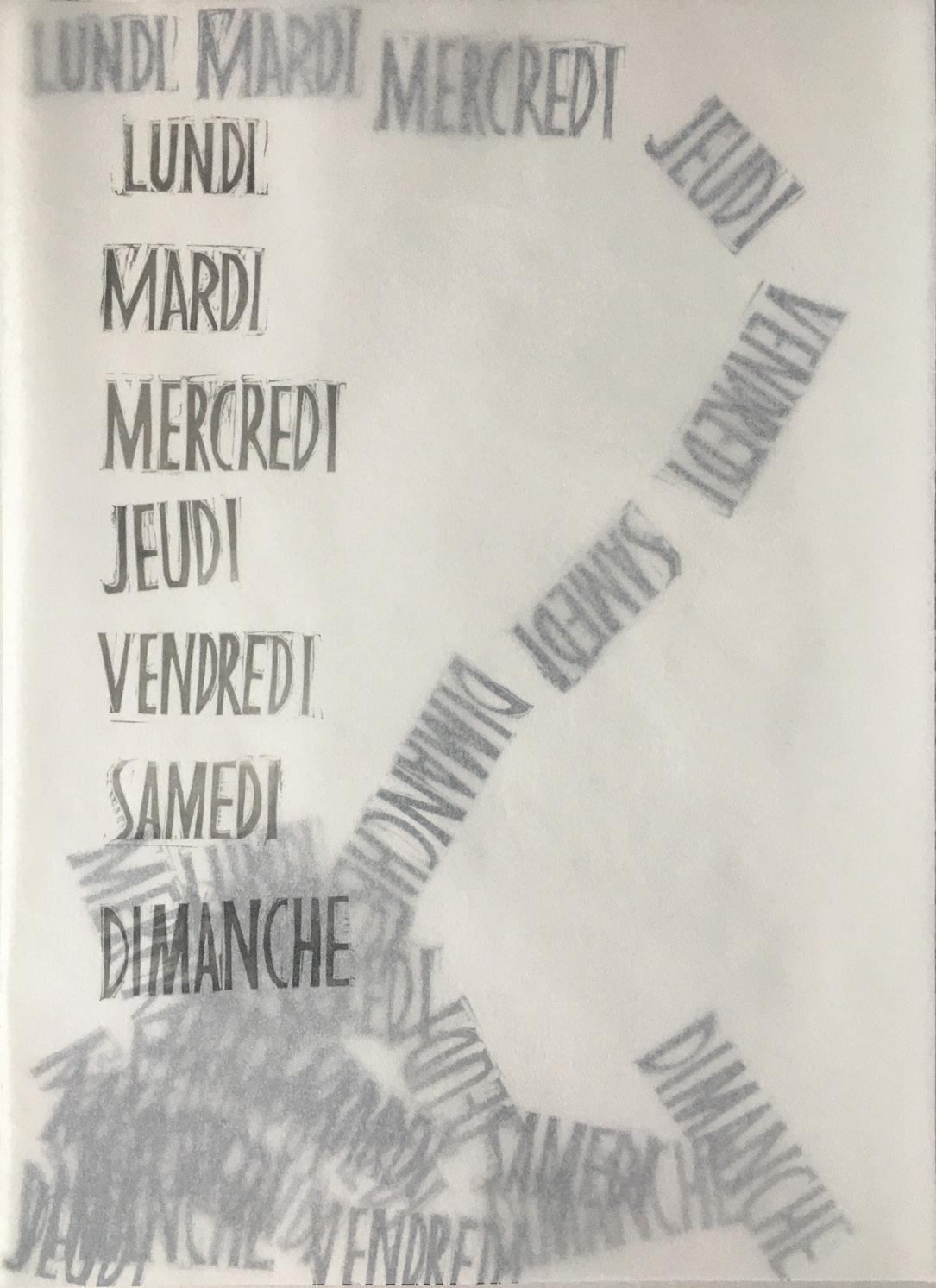

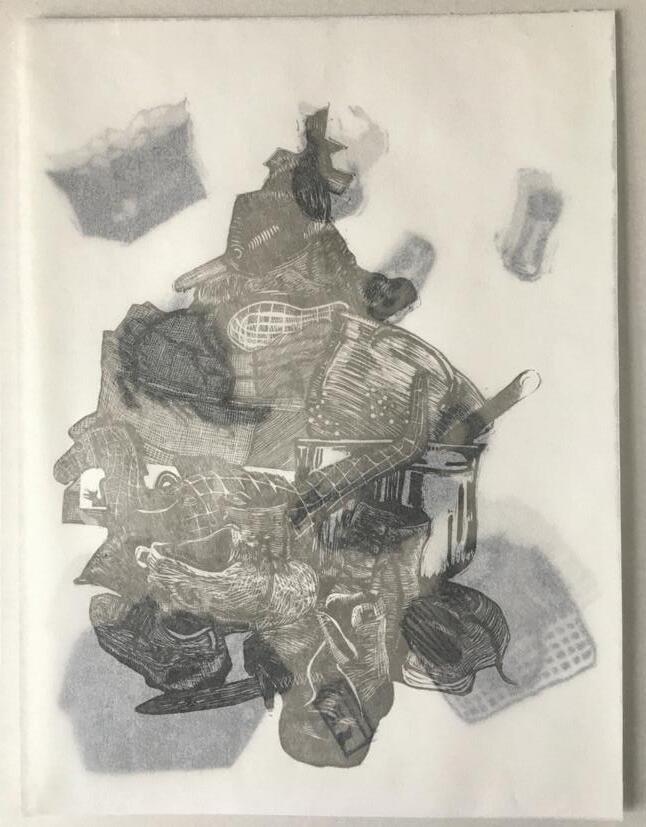

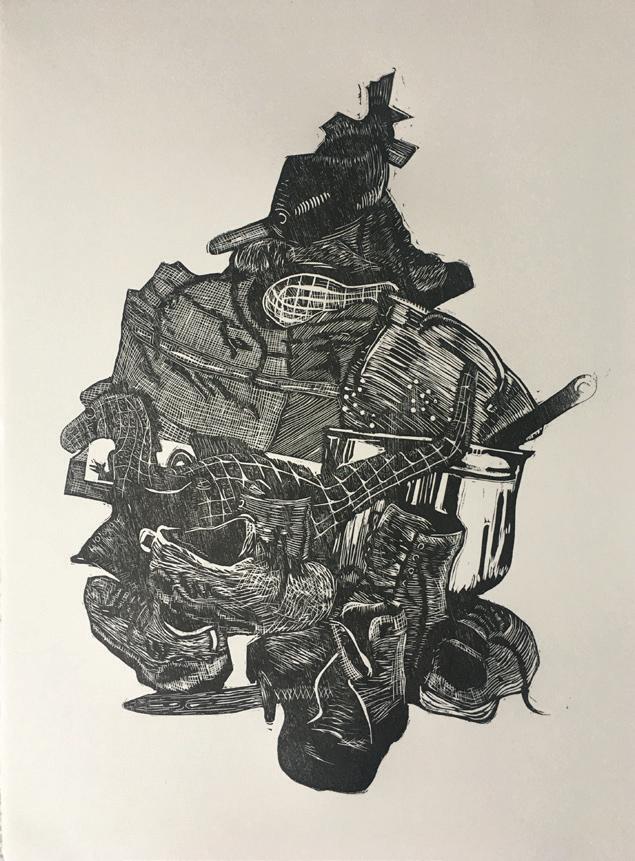

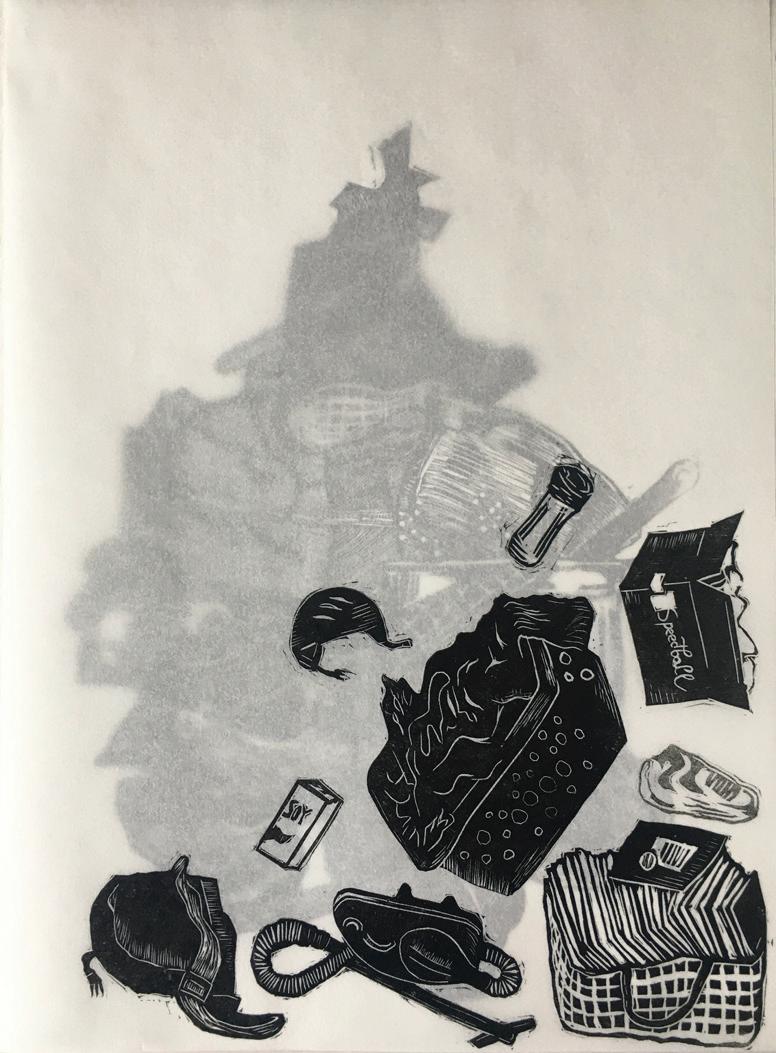

Submergée by Nathalie SeredaBazinet is a project that was conceptualized in the midst of lockdowns during the earlier days of the pandemic. Suddenly confined to her domestic space, SeredaBazinet found herself unable to find refuge from the labour of daily life.

“When we were all stuck at home, I felt like I was fusing with my furniture. I have a family, so I’d end up cleaning up after everyone. Even though everyone was doing their share of housework, there was always something more to do.”

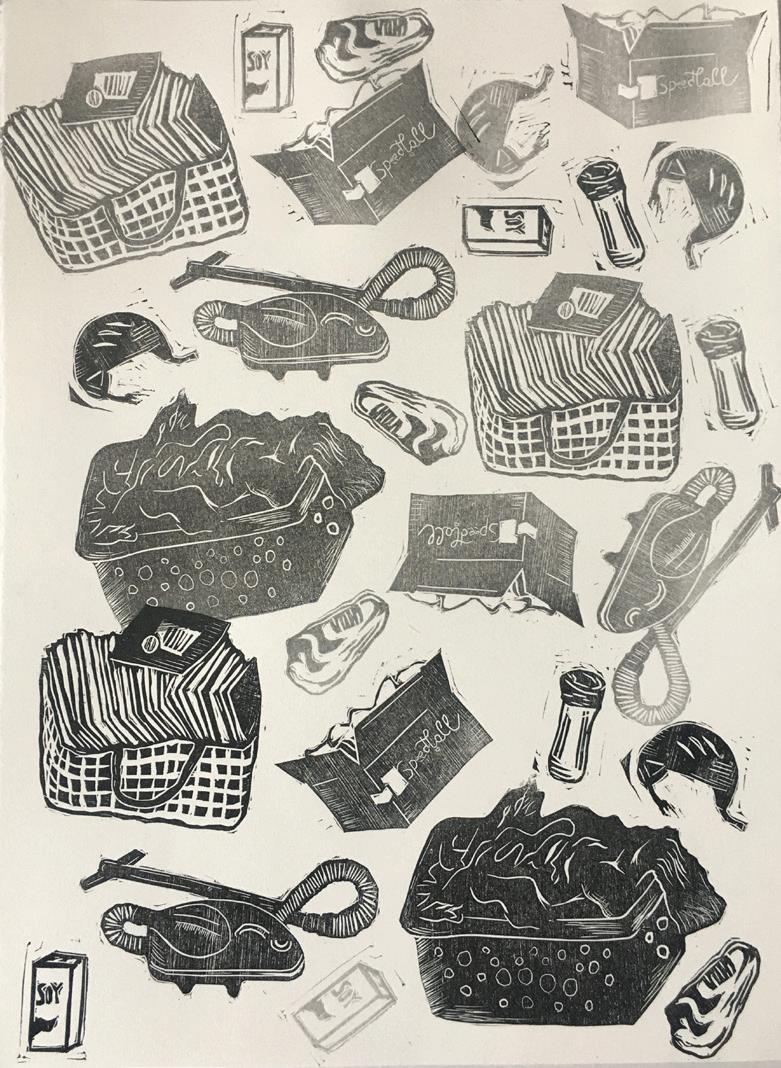

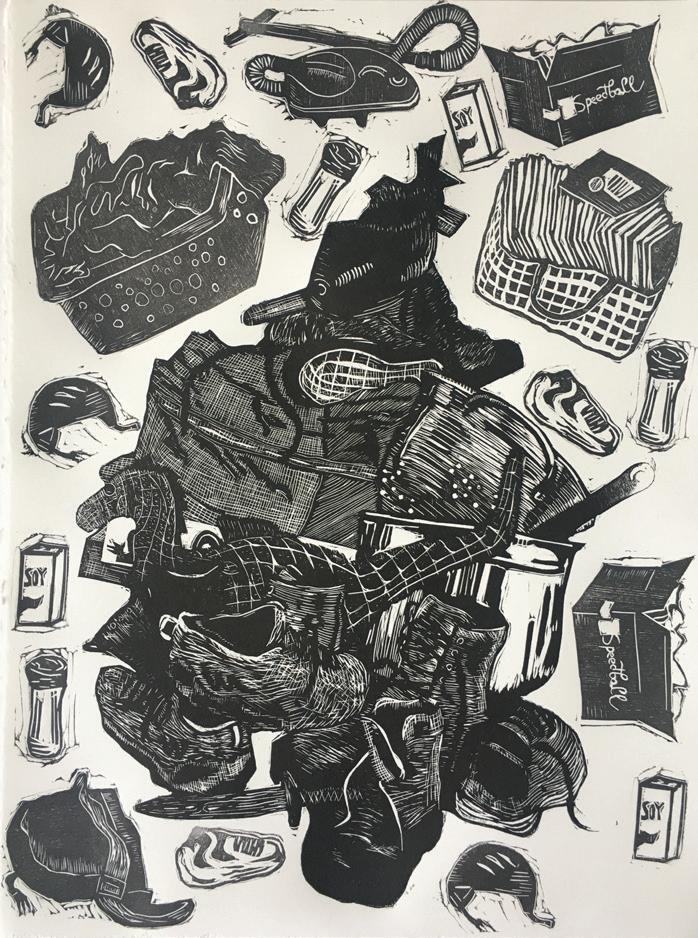

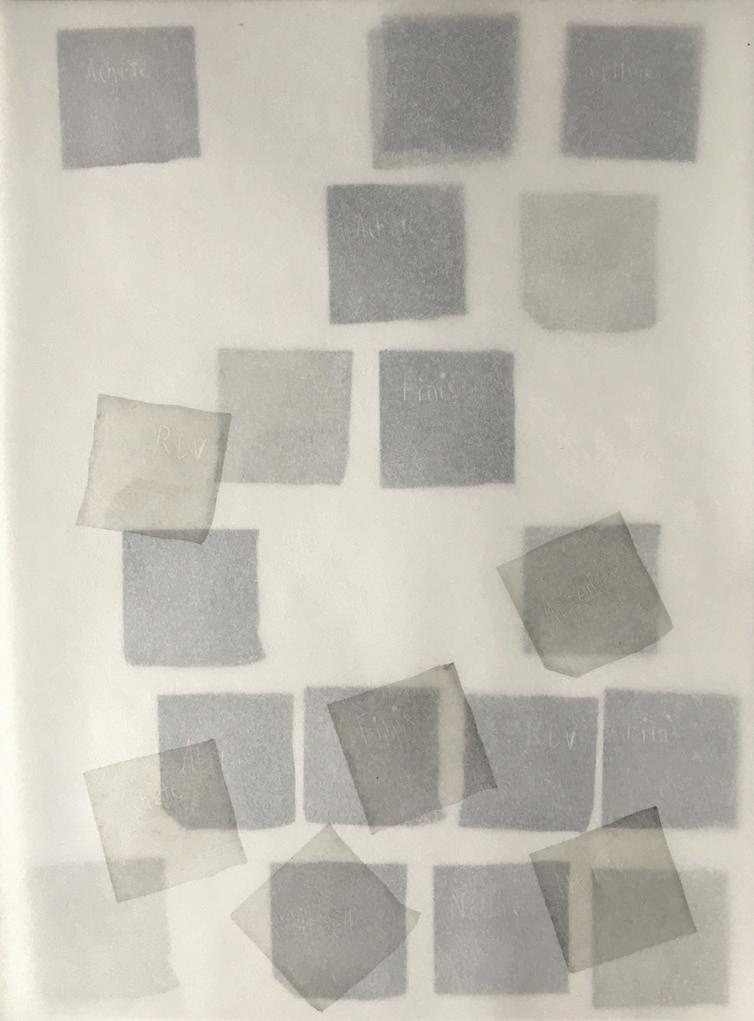

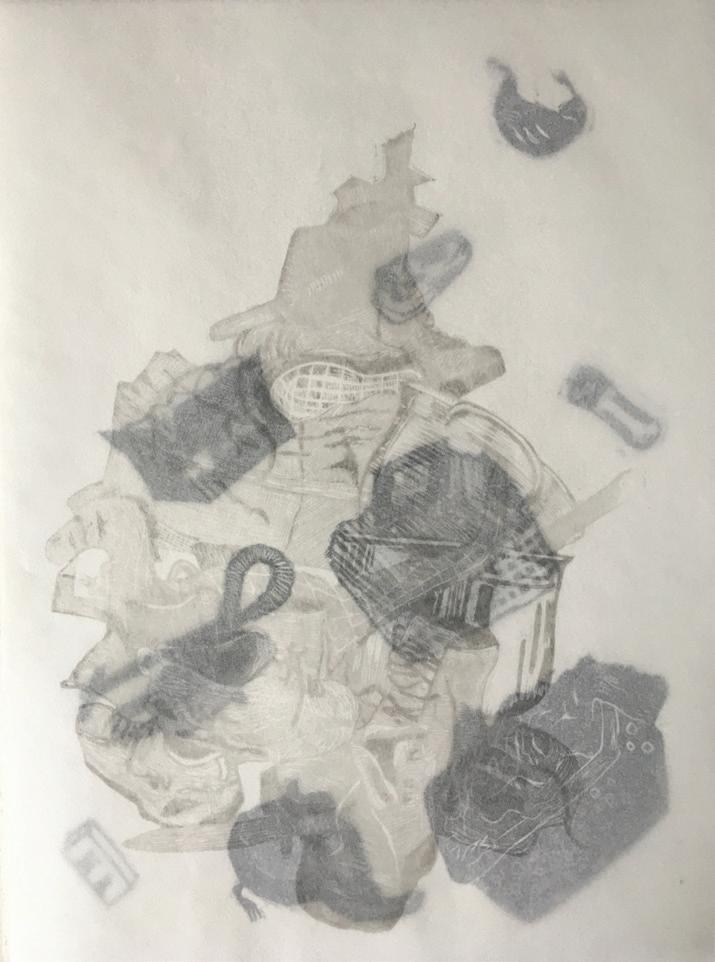

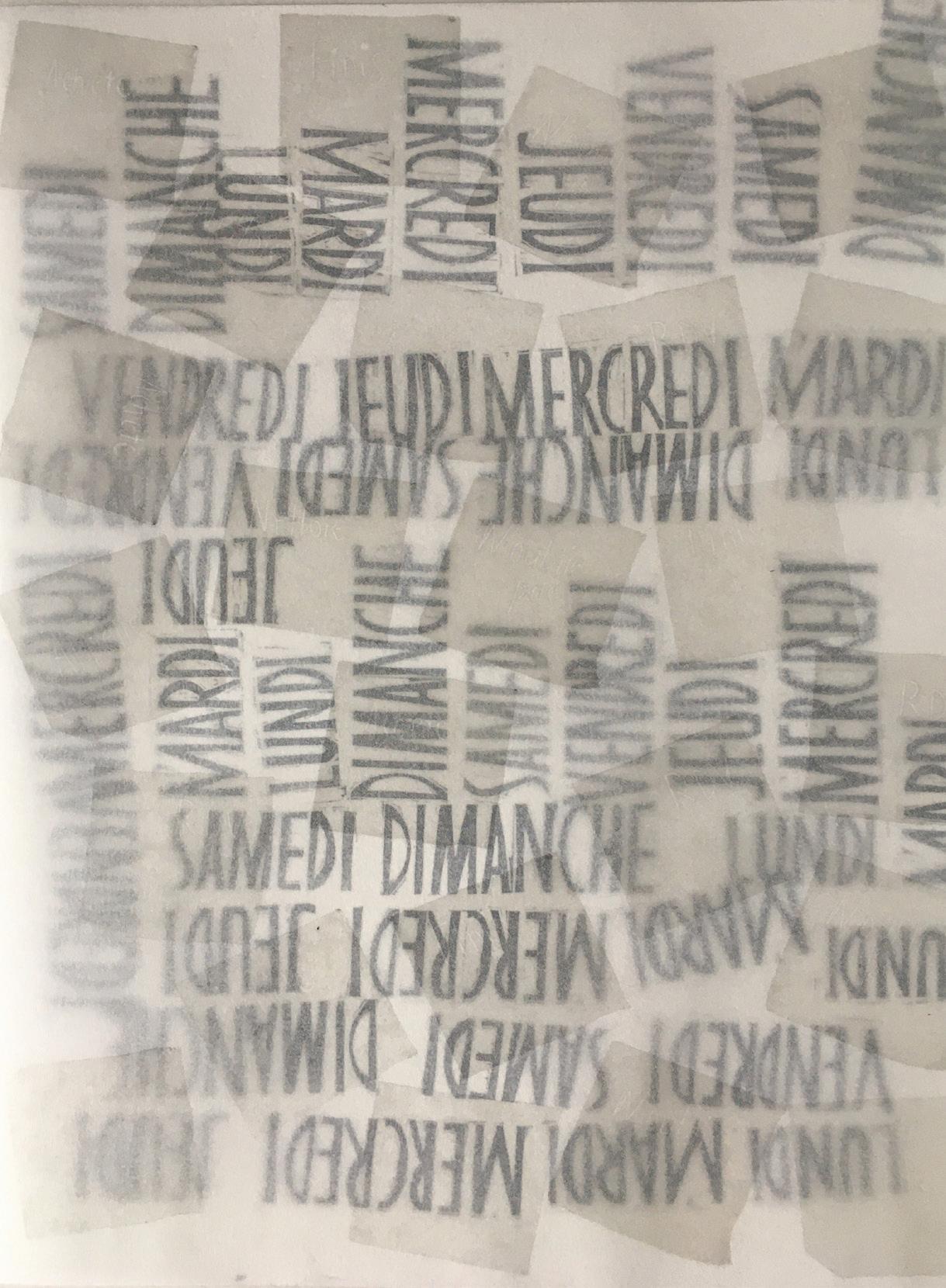

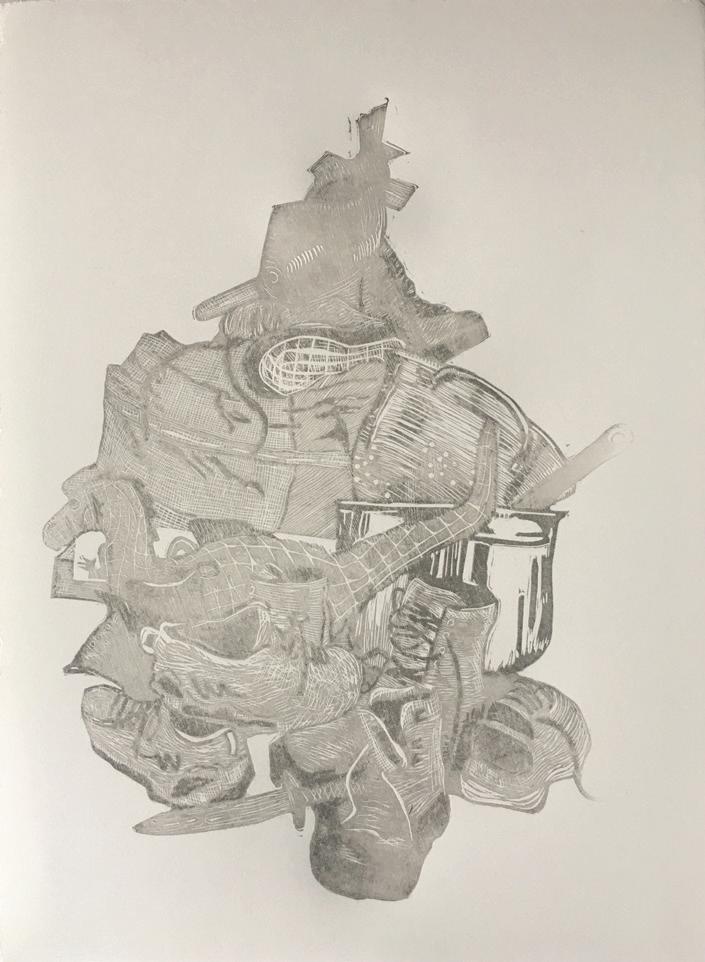

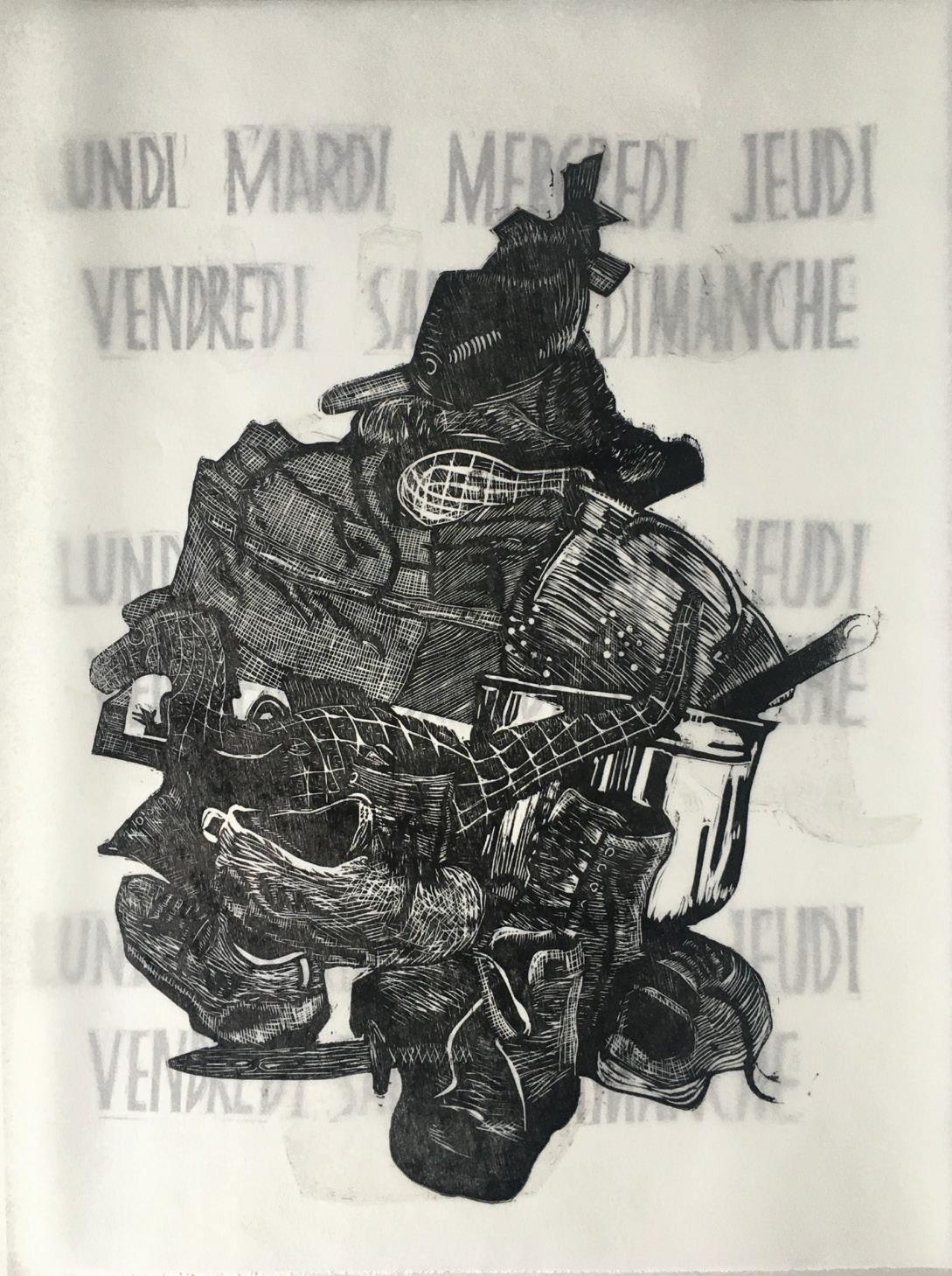

Amidst the difficulty of having to maintain domiciliary stability, Sereda-Bazinet began to find inspiration in the piles of stuff around her home. Inspired by the works of other contemporary feminist artists such as Mierle Landerman Ukeles (Maintenance Work, ca. 1969), Sereda-Bazinet began to reframe her domestic tasks as an extension of her artistic practice. In addition to this, she found herself drawn to the artistic and intimate gestures of archival work, which functioned as a nice compliment to her ongoing drawing and printmaking practice. Printmaking allowed the artist to create multiple iterations of works by layering and rearranging different stamps, reminiscent of the piles of things she was encountering in her home.

Submergée presents the distinct point of view of a parent-artist, a framework that is often detached from the archetypal methodology of art-making. In this way, Sereda-Bazinet’s positionality, in addition to her goals as an artist, underscores the inherently political nature of her work. What results is a collection of work that mirrors the artist’s experience of drowning in the necessary grind of day-to-day life, one that doesn’t scoff at the possibility of finding rhythm and beauty in the maintenance of disorder.