21 minute read

Diasporic Haunted Memory and the Resurgence of Korean Shamanism Online

I clung to this figure as a symbol of pre-colonial and pre-modernity Korea, a path to retrace loss online. This figure within the Korean diaspora operates both as a remembering of the past and an imagining of an Indigenous future. Online, these diasporic communities are working to trace this figure both in the archive and as a lived reality now, in which past and future are being traced within an Indigenous online sphere as an opposing temporality.

I will explore remembering and hauntings as a diasporic subject, the mudang as a haunting figure, and finally, conclude with mapping out how this phenomenon plays out online.

Colonization is a rupture that attempts to create an impossibility of remembering. The concept of the “phantom limb” articulated by Saidiya Hartman in Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America highlights the nature of this in connection to the violent rupture of slavery. This distinction is important, as I will be focusing primarily on the diaspora of Asian peoples, specifically Korean peoples. This im/migration of Korean people to North America is not placed within the context of slavery. Although there exists a long history of underpaid Asian labour in North America, a notable example being the transcontinental railroad1, this is not comparable to the forced removal and relocation of Africans to North America. However, slavery and anti-Black racism are the fundamental basis for all other forms of racism.

Diasporic remembering, at best, often feels never-good-enough. Locating and retracing what has been lost and severed by the forces of imperialism and colonization is hard to reconcile. How does one attempt to locate and trace irreconcilable loss? How does one fill the haunting gaps and spaces that are left in the history of one’s lineage and ancestry? As a third-generation Korean immigrant, this loss has always held a presence—silences and gaps make remembering patchy. As I got older and attempted to locate my Korean ancestral lineage, I turned to the internet. Online, with the little information I had, I tried to trace and retrace the gaps. The internet has been an integral part of my attempt to flesh out the ghosts of my own lineage. A chance encounter on Tumblr brought me to the figure of the “mudang.” The mudang is a Korean shaman—a spiritual leader within Korea’s Indigenous folk tradition.

Still, it is important to remember that colonization looks different in every place and manifests in a variety of ways. Although I see Hartman’s concept of the phantom limb as a valuable resource to understand the ways colonization effects memory and remembering, the context that she is speaking from, Black slavery and the middle passage, is important to note. In picking apart the experience of “loss and affiliation,” Hartman articulates that memory of Africa and/or an imagined pre-slavery, pre-colonial past operates “in a manner akin to a phantom limb, in that what is felt is no longer there. It is the sentient recollection of connectedness experienced at the site of rupture where the very consciousness of disconnectedness acts as a mode of testimony and memory.”2

The question of disability within the phantom limb concept is present, and deserves some thought and discussion.

In other words, slavery operates as this ultimate rupture, almost like the severing of a limb. Although that limb is forever detached, there is a phantasmic experience of its presence even if it is no longer there. All access into diasporic memory is thus remembering “not by a way of stimulated wholeness but precisely through the recognition of the amputated body in its amputatedness.”3 This phantom pain is all that is left from the loss—a ghostly haunting of “home.” In this case, Africa becomes this symbolic home space; even when it is impossible to return to pre-colonial Africa, its haunting is felt. It is this very absence that marks this memory.

Although I do feel as if this metaphor of phantom pain and severing is a critical part of understanding the way that colonial memory works, the ableism in using an amputation as a metaphor is significant. In the article Metaphorically Speaking: Ableist Metaphors in Feminist Writing, Schalk discusses the way that disability is often used as a metaphor in daily life, and this bleeds in to feminist writings. Schalk specifically cites The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, in which bell hooks refer to men as “emotional cripples.” Disability as a metaphor codes an inherent “ideology of impairment as a negative form of embodiment and typically position[s] disability as invariably bad, undesirable, pitiful, painful, and so on.”4 Metaphors often use concrete things to describe something that is abstract, and, in the case of the phantom limb, Hartman is trying to bring to life that which is not tangible—memory and loss. This can be important, especially within Black studies, because the intangible aspects of racism are rarely given the same weight as material racial grievances. Making this concept concrete and in the body, as it often physically manifests, is a political move for some Black scholars.

Hartman is using the concept of the phantom pain that some amputee people experience to understand loss and memory of Black folks under slavery—not necessarily within the context of it as a “negative form of embodiment.”5 Moreover, metaphors of amputation in relation to slavery often move beyond just simply a metaphor. As Alice Hall articulates in Literature and Disability, “amputation figures here as a symbol of the loss of identity and agency, but also as a striking reminder of the material history of the physical and psychological violation of colonised black populations.”6 Hartman’s discussion of amputation, slavery and memory, I believe is making a similar move as something more than a metaphor that centres disability as a part of the lived reality of those under slavery. Yet, despite these important differences, I still think that although phantom pain may help illuminate this concept of diasporic memory, I choose to articulate it differently. I propose the concept of “haunting.” This preserves the concept of the phantom and ghostliness, while shifting away from disability as a metaphor. However, “re-membering,” as Hartman articulates it, does necessitate the concept of dismemberment.7 This concept is important to this work, but I will find other ways throughout my essay to articulate this concept—notably through Grace M. Cho’s articulation of “fleshing out the ghost” in Haunting the Korean Diaspora: Shame, Secrecy, and the Forgotten War that will be discussed later on.8

Melancholia, and more specifically racial melancholia, is a large part of understanding the concept of haunting. Haunting is necessitated by loss, specifically the inability to reconcile that loss. Racial and/or diasporic melancholia’s articulation of loss is notable, and may allow further penetration into the concept of haunting. In the Melancholy of Race, Cheng articulates that in Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia, melancholia is understood in opposition to mourning, which is a healthy response to a lost object; “it is finite and accepts substitution.”9However, melancholia

“on the other hand, is patho-logical; it is interminable in nature and refuses substitution; it is this melancholic cannot ‘get over’ loss.”10 There is an element of both desire for and denial of the lost object. It is “in a sense, exclusion, rather than loss, is the real stake of melancholic retention and it is this very exclusion that turns the lost object in to something ‘ghostly.’”11It is a “spectral drama” in which this lost object is felt and desired, but consequentially denied, creating a ghost. White identity works in this way—a contradictory mix of desire and consumption of racialized peoples along with revulsion, exclusion, and denial. It is the racial other that are made into ghosts. However, I want to focus specifically on how this melancholia manifests within racialized peoples and diasporic haunted memory. Diasporic peoples have a melancholic relationship with “home.” There is both a desire for this lost place, and a denial and exclusion of it, that comes with negotiating their identity and the physical space they embody. This too is a “can’t get over it” loss. Like Hartman expresses with the phantom pain, this loss holds a ghostly presence; although the “limb” is gone, the haunting remains. This “exclusion” could be the diasporic subject’s literal denial of their “home” country (my grandparents refusing to teach my mom and her siblings Korean), or this could be the way in which they feel excluded from this identity (my inability to speak Korean and thus feeling excluded from Korea and other people within my community).

In Ghostly Matters:Haunting and the Sociological Imagination by Avery Gordon, Gordon articulates that “haunting is a constituent element of modern social life. It is neither pre-modern superstition nor individual psychosis; it is a generalizable social phenomenon of great import.”12 In a world structured by colonialism and capitalism, haunting characterizes the daily existence of modern social life. The figure of the ghost is both there and not there. It is “a seething presence, acting on and often meddling with takenfor-granted realities, the ghost is just the sign, or the empirical evidence if you like, that tells you a haunting is taking place.”13 It is seeing and not seeing. As Cheng has articulated, it is both the desire for this lost object and the denial of it that characterizes this haunting. Gordon, Cheng, and Hartman flush out the affective and intangible experience of memory and racialization. The haunting is a “structure of feeling of a reality we come to experience, not as cold knowledge, but as a transformative recognition.”14 In The Literature of the Indian Diaspora: Theorizing the Diasporic Imaginary, Vijay Mishra articulates that “when not available in any ‘real’ sense, homeland exists as an absence that acquires surplus meaning by the fact of diaspora.”15 Again, it is the absence that characterizes this haunting.

For the Asian diasporic communities of North America, what is felt, but also denied, is not just the absence of homeland, but the imperialism, colonialism, and capitalist-modernity that reign over the absence of home. In Haunting the Korean Diaspora, Grace M. Cho articulates that “narratives of Western progress play a large part in producing ghosts through this very process of epistemic violence.”16 Cho finds this ghost within the figure of yanggongju, the Korean women who served as sex workers for the United States of America’s military within Korea. “Behind the image of friendly and cooperative U.S.–Korea relations, 27,000 women sell their sexual labor to U.S. military personnel in the bars and brothels surrounding the ninety-five installments and bases in the southern half of the Korean peninsula.”17 They are both present and utterly invisible. Again, ghosts may be found in absences, and to reveal the phantom “is to focus on gaps.”18 Cho discovered these gaps partially through the internet. She cites an interview published on www. halfkorean.com, a website for half-Korean people to connect and form a sense of community over their Korean identity:

“What is your ethnic mix?

I am Korean/Caucasian. My mother is Korean. How did your parents meet?

I’m not exactly sure how they met. All I really know is my father was stationed in Korea when he served in the Air Force.”

The “I’m not exactly sure” speaks loudly to the unspoken trauma and the absence of the figure of the yanggongju. Too, it is this very absence within the history of Korea that haunts this interview. It is the haunting of American imperialism that created this figure of the ghost within the yanggongju. American imperialism in Korea has been largely denied throughout history. The U.S-Korea treaty was even described by former U.S President Ronald Reagan as the “auspicious beginning of an enduring partnership,”19 which overlooks America’s imposition of their military government into Korea, and their support for Japan’s colonization of Korea.20 U.S imperialism has been an enduring presence throughout Korean history, and has been denied and excluded from Korean official memory. The yanggongju thus becomes the embodiment of this denial, and can be found in the absences. Like Hartman articulates with the phantom limb—this loss is traced through absence, and for Hartman it is the recognition of “the amputated body in its amputatedness.”21 Cho sees “fleshing out the ghost” in a similar way that Hartman sees re-membering; it is not just through seeking out places of absence, but “in the insistent recognition of the violated body as human flesh.”22 The fleshiness of remembering what is intentionally forgotten is important. This ghostliness is a body that has survived trauma, and this must be recognized and fleshed out.

I found it notable that the spaces in which Cho was trying to seek out this ghost were online. Although the internet is considered this symbolic space of the future, past and memory erupt on these online platforms. How does remembering, forgotten past, haunting, and ghosts work in the online sphere? What does it mean to recognize ghosts as flesh online, where physical bodies feel largely absent? Cho finds her ghost in the figure of the yanggongju, however, for my investigation into the hauntings of the online Korean diaspora, I would like to trace the mudang, or the Korean shaman. The mudang has been a somewhat shadowy figure in my own life, and I find her increasingly becoming both visible and invisible online. A mudang shadowed over my grandparents’ marriage—my grandmother, a devout catholic, told me once that a mudang warned my grandfather’s mother that it would be bad luck for her son to marry a catholic woman.

What punctuated the sentence, but wasn’t spoken out loud, was the significant inheritance my grandfather lost when his father died suddenly while he and my grandmother had immigrated to the U.S. The next time I came across the mudang was on Tumblr, in a post about Asian witches. I became wrapped up with this figure, trying to access as much as I could from her online. The mudang as a figure operates in a similar way to the yanggongju; she is both visible and invisible, and “vacillates wildly between overexposure and a reclusive existence in the shadows.”23

Although the yanggongju remains much more shadowy with little discourse surrounding her, they both share some similarities. The mudang is a sort of embodiment of pre-capitalism and pre-western notions of modernity in Korea, with Korean shamanism being an Indigenous Korean tradition. A tradition that, with the onset of modernity and in the name of progress, was heavily policed and restricted.24 What was seen as “superstition” was the antithesis of modernity. Both Japanese colonial police and Christian missionaries tried to eradicate the shamanistic tradition in Korea.25

This figure of the yanggongju is also embodied in the haunting of colonialism and imperialism. The mudang is far from a figure simply relegated to history. She still remains a liminal but present figure in “modern” Korea and her services are still utilized by many Koreans. However, most don’t discuss their use of mudangs publicly out of fear of appearing overly suspicious.26 She remains an unruly woman and is to be feared as a possessor of spirits. Within the Korean diaspora, this concept of the haunting of this figure is made quite literal by the “spirit sickness” that characterizes the calling to be a Korean shaman or mudang. One woman expresses her experience as a Korean diaspora person living in the U.S and receiving the calling.27 She and others are quite literally being haunted by their ancestral lineage, and denying the calling to be mudang often allows the symptoms to persist.28 This is a haunting that demands to be faced. As Gordon expressed, this is not superstition, but a past that lives and breathes in the present with spirits and ghosts that demand to be seen.29

The mudang became a shadowy trace through which I tried to understand my own haunting. Somehow, she felt like a path to re-membering, and if I could only flesh out the ghost of the mudang, I could somehow work through my own loss. The internet became my most valuable resource. Gordon articulates that these new technologies operate with a sort of “hypervisibility” in which it is hard to distinguish presence from absence.30 She goes on to explain that “in a culture seemingly ruled by technologies of hypervisibility, we are led to believe not only that everything can be seen, but also that everything is available and accessible for our consumption.”31

In the time that Gordon is writing, the internet was still somewhat in its early days, and she is focused on discussing television. However, her understanding of hypervisibility speaks to the internet well, and allows us to understand the difficulties of tracing absence online. I discovered the mudang as a chance encounter on Tumblr—I was surprised that this was the first time I had come across her. With the internet being one of my only tools to access some understanding of my ancestry growing up, I thought I had known everything there was to know about Korea. South Korea on the internet remains a hyper visible presence—with K-pop, Korean fashion, and K-dramas dominating not just the Korean internet sphere, but also Western internet fan culture. Korea dominates “Asian” entertainment in the West, and has become a culture industry powerhouse.32 It only takes a quick search for “Korea” or “South Korea” on Twitter, Tik Tok, YouTube, or Instagram to be flooded by images and videos of K-pop stars, starlets, actors, and celebrities that dominate the discourse. In this milieu of hypervisible Korean celebrities, it is hard to feel the presence of absence—everything is not only seen, but is readily available for consumption. In the hyper-visibility of South Korea as a cultural industry, this underbelly of Korean identity on the internet was not accessible to me when I didn’t know where to look. A chance encounter was the only way in which I could find a trace, but once I found it, a community slowly opened up to me. On social media, the ghost of the mudang is being fleshed out by communities, activists, and modern day mudangs. These folks have a space to discuss and construct a forgotten memory, which breathes life into an ancient tradition that was threatened to ghostly obsolesce as modernity and globalization consumed the world. Re-membering is the process of bringing life to Korean shamanism as a forgotten memory. With the help of social media, communities don’t need a government sanctioned official memory place—they could create their own. In Fixing the

Floating Gap: The Online Encyclopedia Wikipedia as a Global Memory Place, Pentzold determines that memory is a collective experience, and it requires a group that is placed within space and time to remember it.33 Moreover, Pentzold cites a memory place “as any significant entity, whether material or non-material in nature, which by dint of human will or the work of time has become a symbolic element of the memorial heritage of any community.”34 Pentzold identifies the internet’s role as a new memory place that doesn’t need to rely on an official memory; “the web presents not only an archive of lexicalized material but also a plethora of potential dialogue partners. In their discursive interactions, texts can become an active element in forms of networked, global remembrance.”35 Pentzold determines that the internet allows for “divergent interpretations of the past” to be a part of the collective memory dialogue. There is a form of collaboration that Pentzold sees the internet engaging in, specifically on Wikipedia. He determines that it “is not a symbolic place of remembrance but a place where memorable elements are negotiated, a place of the discursive fabrication of memory.”36 With multiple people being allowed to contribute to the Wikipedia pages, he sees this space as a negotiation of memory in which it can be collectively discussed and constructed. However, Wikipedia is heavily monitored, usually to protect from vandalism, but perhaps this restricts users to engage with this discourse.37 Social media is possibly a more viable medium to see collective memory at work and to serve as memory places.

I decided to use Instagram as my primary platform of research—Twitter, Tik Tok, and YouTube all had interesting content about how the Korean diaspora was grappling with this figure. However, using just one platform allowed me to concentrate my search. I would like to establish that since I am primarily looking at English language content on these online spaces, my work will be specifically focused on how the diaspora negotiates the figure of

#koreanshamanism to identify the different creators, posts, and community networks. It is important to note that in #koreanarchives, the posts and/or pages may not explicitly be about Korean shamanism or the figure of the mudang. However, these archival spaces online also assist me in understanding how the past is remembered online, and if the figure of the mudang has a space within this remembering. In my search I found three creators of note: @shaman.mudang, @koreanarchives, and @themudang.

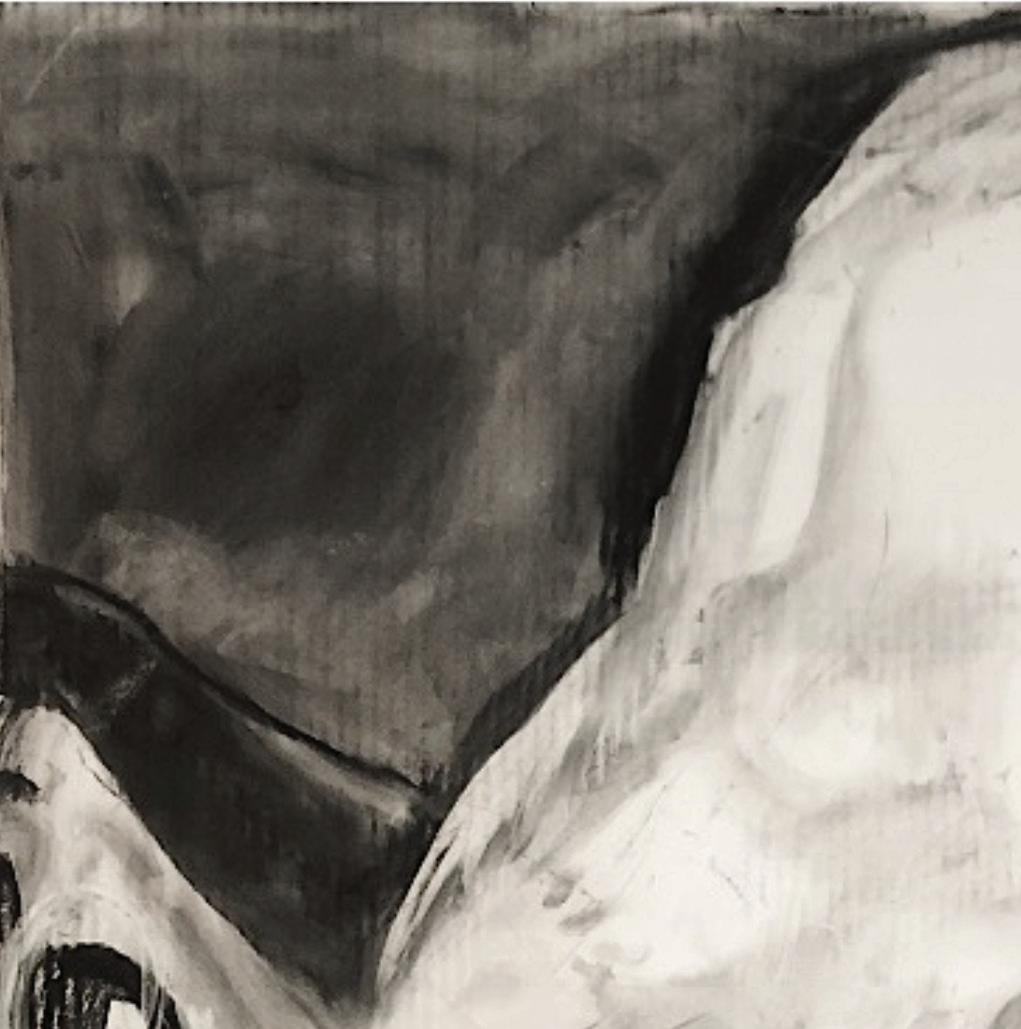

In discussing explicitly archival historical content, @koreanarchives is engaging in an interesting project. It asks people within the Korean diaspora to send in family archival material in the form of photographs. It is a project that works to curate a collective archive in which people contribute their own stories. I found the figure of the mudang in these archives, but she was hard to make out. The photo struck me when I first saw it—a figure in the shadows. The mountains of Korea just behind her (see fig. 1). Her figure is present, but her face remains invisible. It is a beautiful photo that encapsulates the mudangs continued haunting within the online sphere. This online memory place is a space of loss and longing. It is the diasporic hereafter, in which people attempt to construct some sort of collective understanding of a Korean identity. In this photo, the mudang still remains a shadow, however, it offers a space for remembering. I felt the loss most acutely in this photo; it was a trace, but something I couldn’t necessarily hold onto. However, this photo held possibility, and through the mudang online. I can not speak to her presence or absence within Korean language spaces. Moreover, I would like to create a distinction in the way I saw folks fleshing out the ghost of the mudang on social media online spaces. First, there is the figure of the mudang as a historical figure within the archival space. Second, there is Korean shamanism and the mudang as a lived reality and tool for revolution and social change. These two approaches to the mudang are definitely not distinct categories or a binary. Moreover, oftentimes creators will engage in both impulses through using their platform as an archival memory space for the history of mudangs in Korea, and using this shamanism as a lived reality—oftentimes as a political tool. I used the hashtag #mudang, #koreanarchives and the other creators I researched I saw the ways that this figure, and these stories, were being maintained and were resurging.

(Fig. 1, @koreanarchives, 2021). The creators @shaman.mudang and @themudang are self-identified Korean shamans and mudangs. They primarily engage in the second impulse, and they utilize Korean shamanism as a lived reality. They call back to this as an ancient tradition, but also assert their continued existence in this time. Not as a “superstitious” tradition of the past, but a community of diaspora folks whose relationship with the figure of the mudang is being worked out now. This includes sharing a few of their practices, such as ancestral worship, their clothing and traditional dress, and a look into rituals they engage in (see fig. 2, fig. 3, fig. 4).

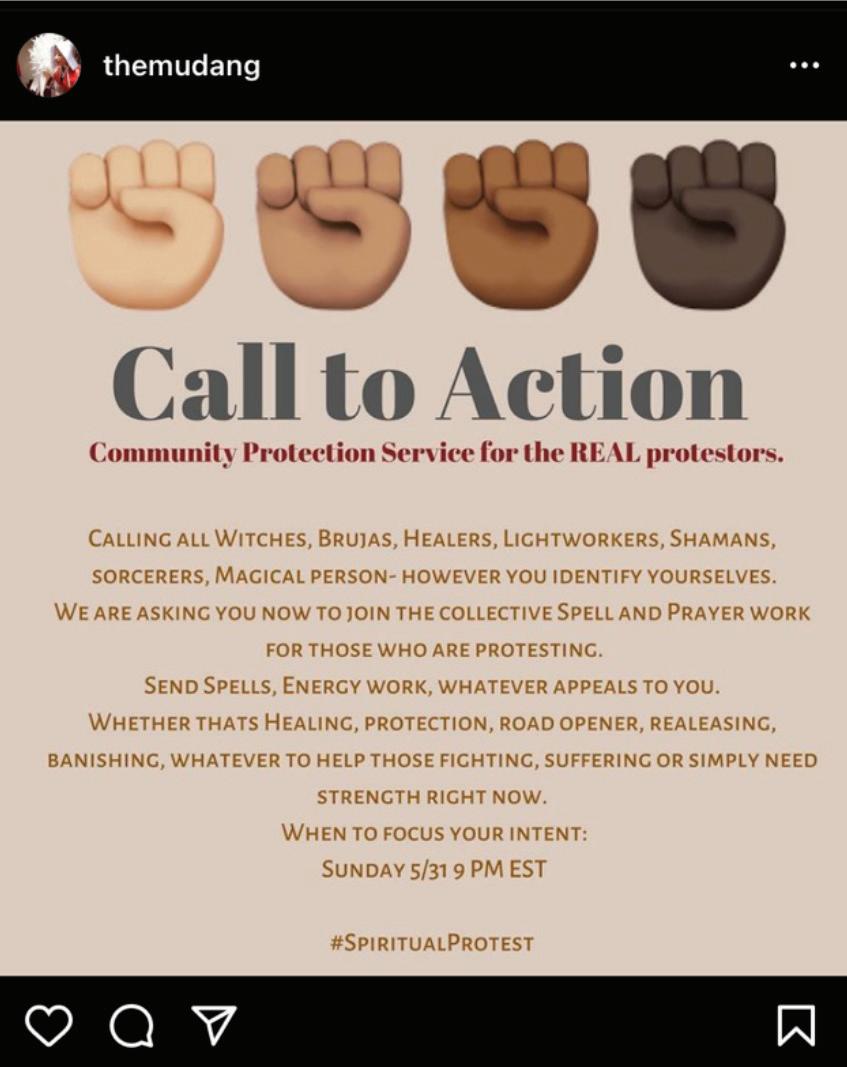

Creators such as @shaman.mudang and @themudang also post explicitly political and revolutionary content. There is both a move to reclaim the past and to create a new future with a few posts calling on other Korean shamans and cross community spiritual healers such as witches, brujas, healers and lightworkers to merge their collective efforts and powers into protecting protestors during George Floyd protests against police brutality (see fig. 5).

Under this post, we see the hashtags #koreanshaman, #blackpower, and #asians4blacklives. There is a move towards using these spiritual powers for revolutionary means. These creators align themselves with issues such as Black Lives Matter (BLM), fighting against anti-Asian racism, and Indigenous solidarity. They imagine a new future, while also returning to traditions from the past. Moreover, these traditions are specifically used for and working towards a more just future. In other words, it is creating a sort of cyclical time: a temporality that is both invested in the future and in return—in which both are accessible in the present. Perhaps this works as a model of fleshing out the ghost. As a diasporic subject, the possibility of return can never be fully realized. Many traditions have been lost and perhaps cannot be revived. However, future resurgence of these traditions that were able to be maintained are a part of the way we shape the future. These creators have not been able to escape the haunting and calling of the past—literally in the embodiment of their ancestors—and they take the living breathing past and move it towards new horizons. It is this very shifting temporality that refuses to march to the beat of colonization’s time. In Beyond Settler Time: Temporal Sovereignty and Indigenous Self-Determination, Rifkin discusses the notion of temporal sovereignty, specifically with Indigenous North American peoples. Rifkin asserts that “rather than approaching time as an abstract, homogeneous measure of universal movement along a singular axis, we can think of it as plural, less as a temporality than temporalities.”38 Moreover, it is this “very excision of Indigenous persons and peoples from the flux of contemporary life, such that they cannot be understood as participants in current events, as stakeholders in decision making, and as political and more broadly social agents.”39 This is the process of making Indigenous peoples “ghostly remainders.”40 Although Rifkin is using this process of haunting in a different way, I think it is applicable. Here, Indigenous peoples are seen as ghosts of the past and as mere hauntings that settlers are determined to forget. They are ghosts without bodies, or perhaps flesh without a stake in the “modern” world. In asserting mudangs and Korean shamanism not only as a lived reality, but as actors that have agency not only in the now but in the shaping of future worlds. These creators are opposing modernity’s temporality.

The question of Indigeneity is increasingly more complicated as those practicing Korean shamanism occupy various North American Indigenous lands. Korean shamanism, like most Indigenous traditions, is dependent on geographic specificity. The connection with land and nature is strong like various other North American Indigenous traditions. It understands that “human beings come into the world as integral parts of the rhythm of nature,” and relationship with the land is an integral part of this tradition.41 It is important to note that although Korean shamanism is a Korean Indigenous tradition, diasporic Korean shamanism that is primarily centered in the U.S is not being practiced on their Indigenous land.

Moreover, the spaces that they are occupying both on and offline cannot be separated from the question of them being a settler. What is the responsibility of these diasporic Korean shamans who are practicing their Indigenous tradition on other communities’ land? The question of Indigenous solidarity specifically within online spaces proves to be complex—with online spaces assumed to be existing in the ether, disconnected from tangible land.

In Making Kin with Machines, Jason Edward Lewis, Noelani Arista, Archer Pechawis, and Suzanne Kite, discuss how these online spaces and technologies “that compose cyberspace [are] situated within, throughout and/or alongside the terrestrial spaces Indigenous peoples claim as their territory.”42 Moreover, they ask “how do we as Indigenous people reconcile the fully embodied experience of being on the land with the generally disembodied experience of virtual spaces?”43 I would also say in the question of fleshing out the ghost, what does flesh have to do with the non-flesh virtual space?

In the article, Suzanne Kite discusses Lakota ethics and ontology in the interiority that is given to the non-human, such as stones. These materials from the earth are what make up the machines that we use�— the very machines that allow access to these social media spaces. In the world of Korean shamanism, where the natural world is endowed with spirits, what are the spirits that these machines hold? Moreover, if these machines are a mode in which we access past posts through archival content and a community of people sharing these pre-colonial traditions, then these machines essentially work as an extension to memory, and perhaps an extension to the body. To return to Cho’s iteration of fleshing out the ghost, if it is these machines that are allowing this ghost to be transformed in some way into flesh, then what type of flesh is it? Re-membering that is necessitated by these machines as intermediaries makes these machines an essential part of diaspora memory. If we take Hartman’s iteration of memory, perhaps this may look like a sort of holographic limb. The possibility of returning to these Korean shamanistic practices occurs through these online communities that make this resurgence possible. These technologies of the future access the past—recovering what was seemingly forgotten and creating a possibility for them now.

In a way, this loss as a diasporic subject still remains irreconcilable. There are still gaps in my own ancestry that I will perhaps never recover. There are absences that these online spaces can’t fully fill. These are forgotten histories that I will always be haunted by. However, I found the possibility for resurgence and a new way to access the past in these online spaces. The mudang as a haunting figure is being given the space to be a living reality. These spaces allow for opposing temporalities that resist modernity and face haunting where the living past creates the possibility to shape change now.

Portrait of Karina by Issy Tessier is a charcoal and chalk drawing that captures a still of a dancing figure from an 1898 mutoscope film reel. In this work, a subversion of dominant art historical tropes is challenged, wherein a male artist gazes upon his subject – the female muse. Tessier confronts this power relation by approaching her subject, Karina, as an artistic collaborator, as well as a source of inspiration. In addition to this, through the gestural act of archiving, Tessier’s encounter is embedded in an ongoing story of remembering.

Tessier’s approach is “inspired by [a] 1970’s feminist model of collaboration.” Karina, the so-called subject, assists Tessier in creating works that extend beyond the confines of space and time –