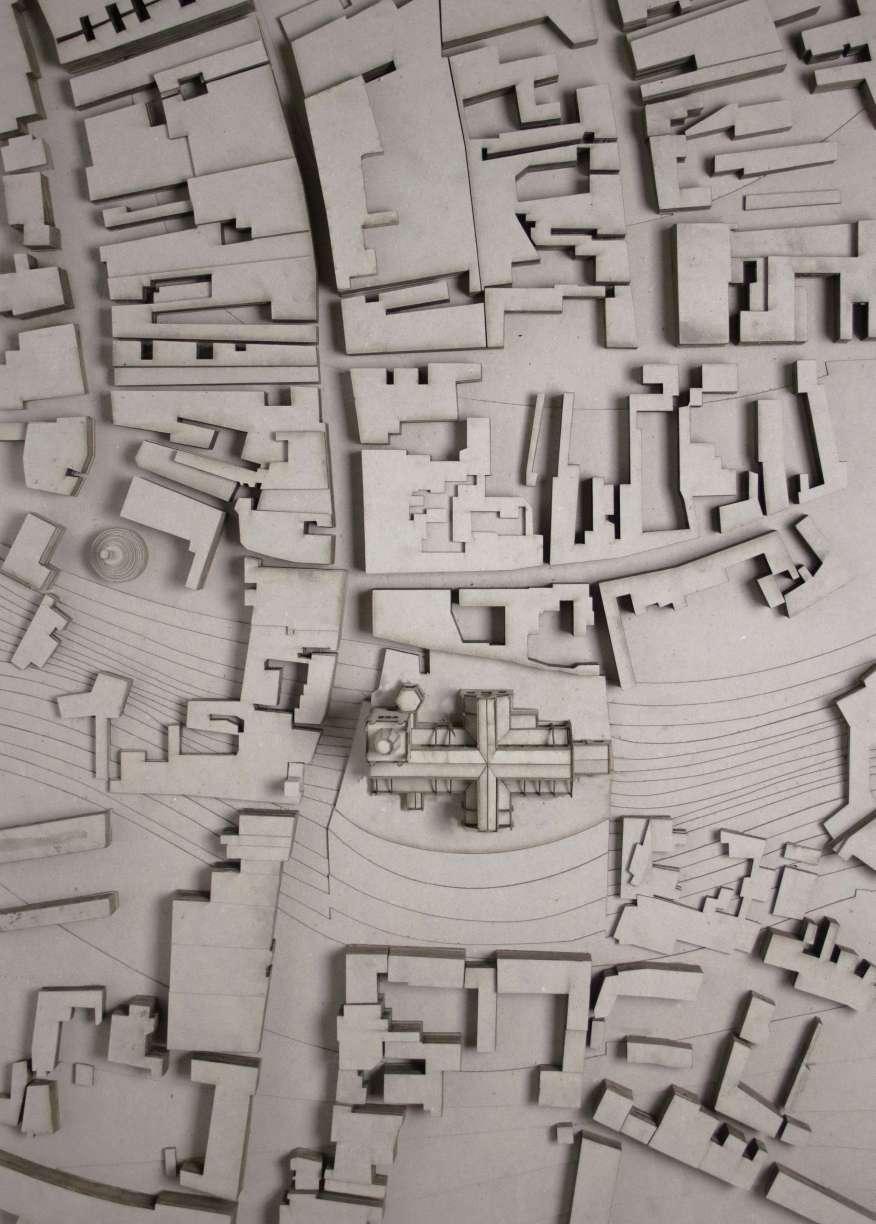

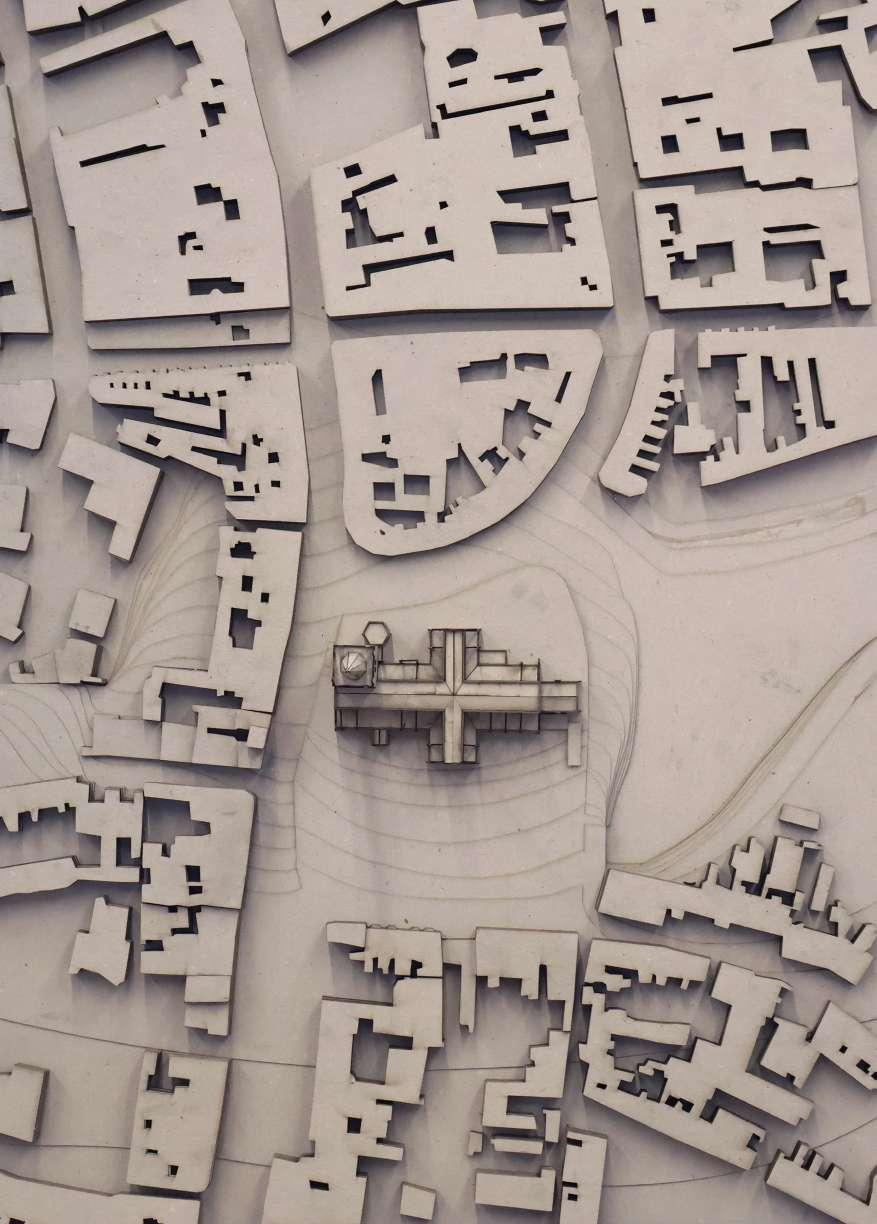

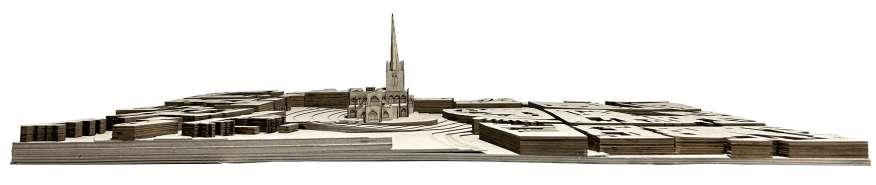

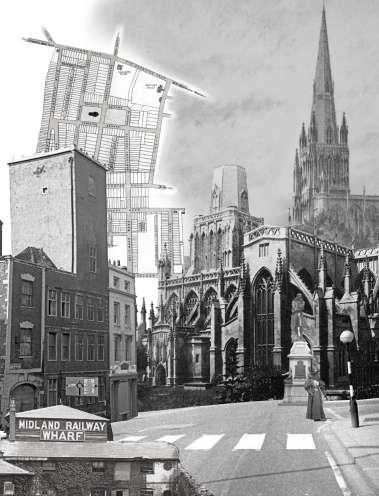

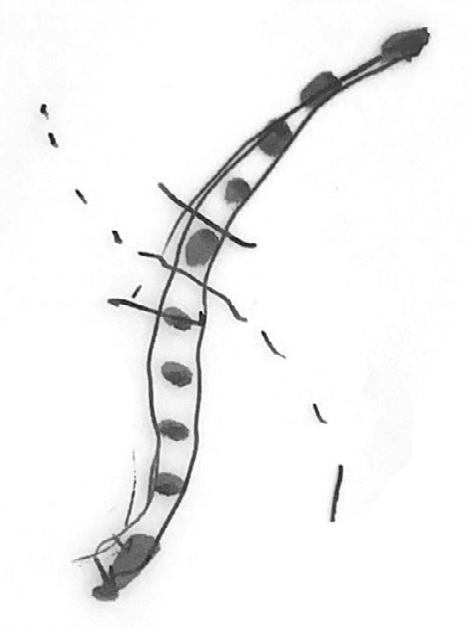

A symbol for the morphological changes of Redcliffe, Bristol throughout the centuries. Our group temporal model aims to map the historical, political and cultural changes experienced by the city. By understanding these changes, we aim to have a more meaningful understanding of the site to help guide our primer designs and comprehensive design project.

The medieval period is generally defined as being from the 5th to 15th century, however our exploration of Medieval Redcliffe focuses on the later half of this time, with some references as late as the 18th century due to a lack of available information.

Medieval Redcliffe was not part of the city of Bristol, despite being located right on its urban-rural edge. Internally, Redcliffe itself was separated into North and South by the Port Wall and moat, which as Redcliffe began to develop became a separation between a more built up north and the rural south. Throughout the medieval period, the area began to undergo rapid densification in the direction of the existing farmlands and fields, especially along what’s now known as Redcliffe Hill. Rossi states that “cities tend to remain on their axes of development, maintaining the position of their original layout”, which seems relevant to the context of Redcliffe, and can be traced through all time periods.

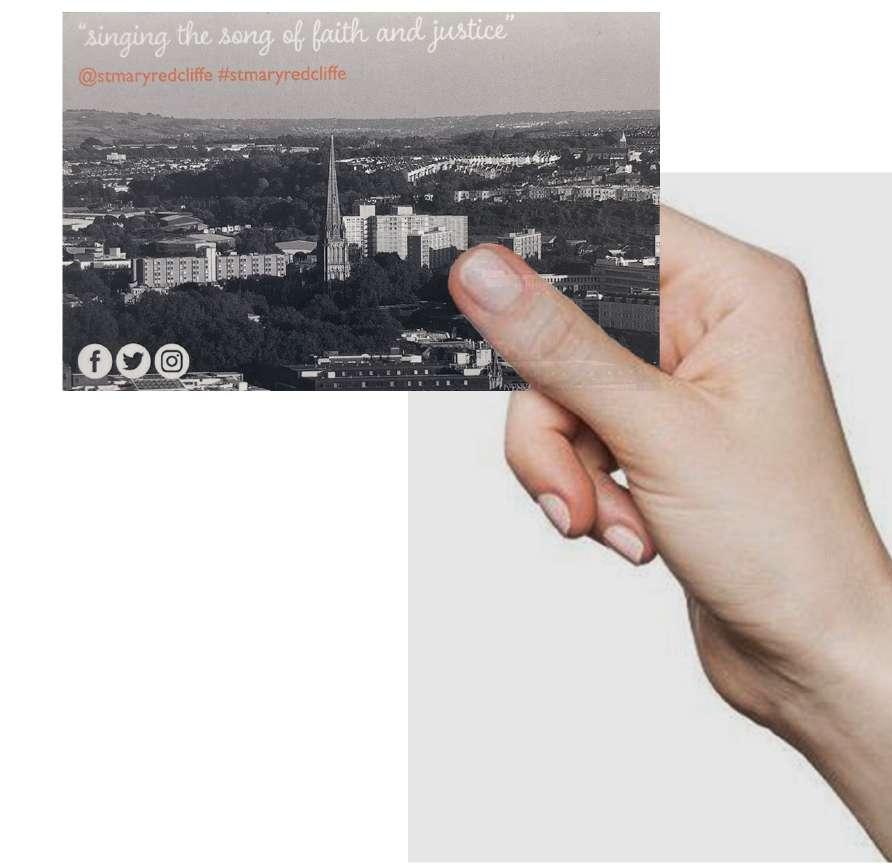

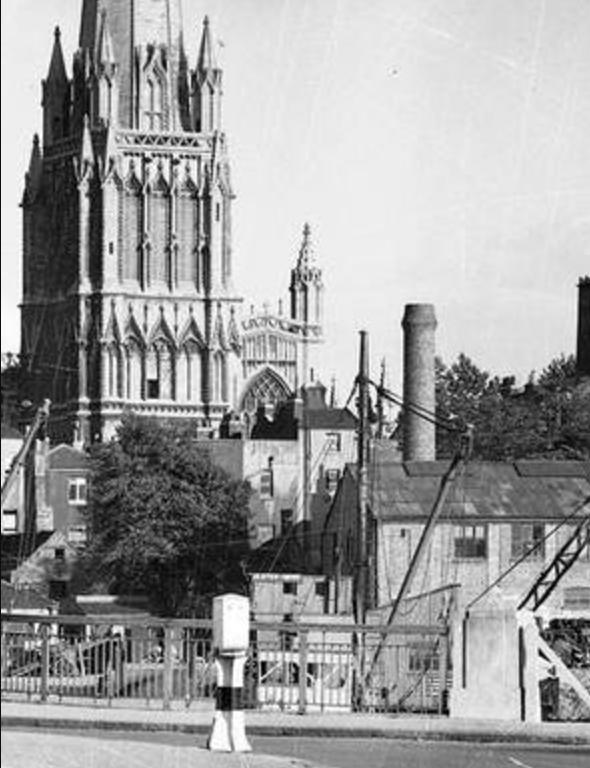

One of the permanence’s that can still be experienced today is the St Mary Redcliffe Church. The Church has remained largely unchanged since the medieval period, with minor adjustments and the spire being the exception. The settlement that surrounded the church was mostly secular, supplying the area with schools, hospitals and smaller chapels. In addition, directly to the south of the church, are the early traces of what we now know as Colston parade. Millerd’s 1673 map (right) points towards three different buildings, which originally were also part of the secular settlement.

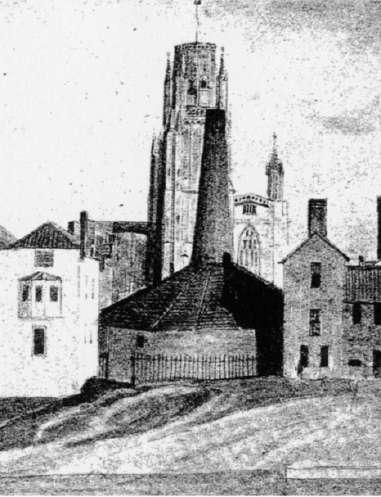

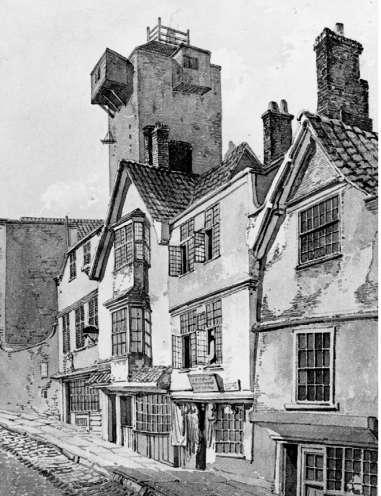

To model medieval Redcliffe, we treated the buildings as masses, tracing back from 18th century maps and applying the medieval context we observed from various artistic representations, illustrative maps and drawings, in the absence of scaled plans, such as, Smith’s engraving of 1568 (centre). Therefore, we acknowledge that what we have modelled is a version of Redcliffe’s history, with it being difficult to pinpoint exactly what was present at any one time.

18th century, Redcliffe underwent significant expansion, transforming from a small riverside parish into a bustling industrial hub. Its proximity to the Avon River, made Redcliffe an attractive site for merchants and shipbuilders. This period saw a boom in trade and commerce, fuelled by the city’s active participation in Trans-Atlantic trade, including sugar, tobacco, and significantly, enslaved people. Sprawling below the streets of Redcliffe, the caves became integral to Bristol’s booming glass and pottery industries. The caves housed kilns, workshops and storage for good ready to be traded in Africa and the Americas.

William Watts’ Lead Shot Tower marked a significant shift from the Redcliffe of the 17th century to a 18th-century landscape shaped by industrial innovation, and global trade reflecting a broader change as more of Redcliffe’s green spaces and residential areas gave way to warehouses, workshops, and facilities. A constant though is St Mary Redcliffe Church, which sits on a plinth amongst the hustle and bustle untouched by the expansion of Redcliffe. It was perhaps, this symbol of permanence that inspired Thomas Chatterton, the young poet and muse of Romanticism, to create fictional historical works that retained Redcliffe’s medieval history. His writings, as well as his drawings provided valuable insight into the city’s architectural and cultural history.

To model this transformation, we relied on historical documents, photographs, and drawings. While challenges arose in determining precise building heights, the overall topographical features remained relatively constant. The church, Colston’s Parade, and Redcliffe Hill formed the backbone of Redcliffe’s landscape. By exploring the temporal model of Redcliffe’s expansion, we gain a deeper understanding of the city’s complex past. From its medieval origins to its industrial heyday, this period is one of growth, innovation, and the enduring power of the city as a museum.

Redcliffe featured significant transformation through the 19th century via the industrial expansion, urbanisation, and maritime trade. The development of Redcliffe and its accumulation of wealth is beholden to Bristol Harbour and its involvement with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The hidden tunnels under Redcliffe were used to transport sugar, cotton and tobacco goods subjugated by Bristol merchants, which in turn poured money into the expansion of Redcliffe. The industrial revolution links here too, as factories and extensive dock facilities located on the harbour began to impact the area at an excruciating level. Through the expansion of urbanism, there was a range of social challenges such as poverty and disease, on account of the clustered infrastructure in the area.

One merchant of note, Edward Colston (whose memory was honoured for centuries), funded many renovations of St Mary Redcliffe Church, through the trade of African Slaves. A moral challenge appears here through the attempt to draw away from the history of slavery in Bristol and decades of misuse of the church. The Canynges Society was formed in 1842, with the goal of restoring the church to its original neogothic appearance. The baroque interior was stripped, along with the high box pews and Georgian era galleries. By 1872, the spire of the church was restored to its former height of 260 feet above ground level. The intention to return to the medieval context enables the misinterpretation and neglect of the history of the church, neglect of accountability through the architectural developments.

The change in typology and topography of the area is a result of industrial development. The railway system was introduced to Redcliffe, opened in 1870, and situated close to Bristol Harbour. It enabled efficient transportation of goods, resources, and passengers across Britain, supporting the economic growth of the city. The railway was carved through the red cliff used to transport goods. A bypass was also introduced to the urban context, cutting through Redcliffe, as a road that allowed efficient transportation through the area. The Redcliffe Railway embodied 19th century progress and innovation, reflecting the transformative power of infrastructure and how connectivity shaped city landscapes, fostered economic prosperity, and brought communities closer together.

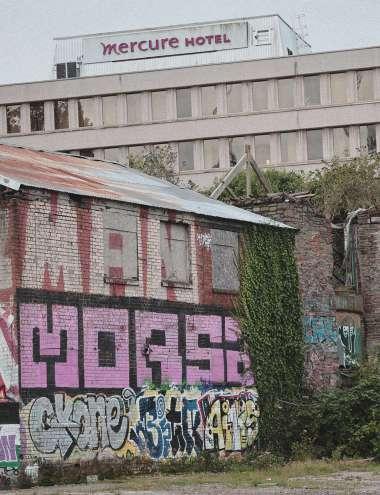

As Bristol travveled into the Industrial Revolution, Redcliffe became a bustling industrial hub, packed with factories and dense, woekring class housing. However by the 20th Century, as industries began to decline, redcliffe and similar areas were riddled with economic challenges and a need for revitalisation. To accomodate for bristols ground young population, new housing blocks werw built in Redcliffe, however the lack of care and consideration to these designs resulted in poor quality, housing solutions which over time has encouraged anti-social behaviour in the area.

Bristols status as a ‘sanctuary city’1 means it has a continuously growing population of refugees and migrants. Welcoming people from across the world; Bristol, and redcliffe specifically have become multicultural hubs . Colin rowe in his book, ‘Collage City’ writes that cities are not bound by a single historical narritive but rather are formed by the collision and interplay of diverse cultural and temporal elements. This collage approach revitalises a city by acknowledging the transcultural nature of cities, resulting in a rich tapestry of experiences and meanings.

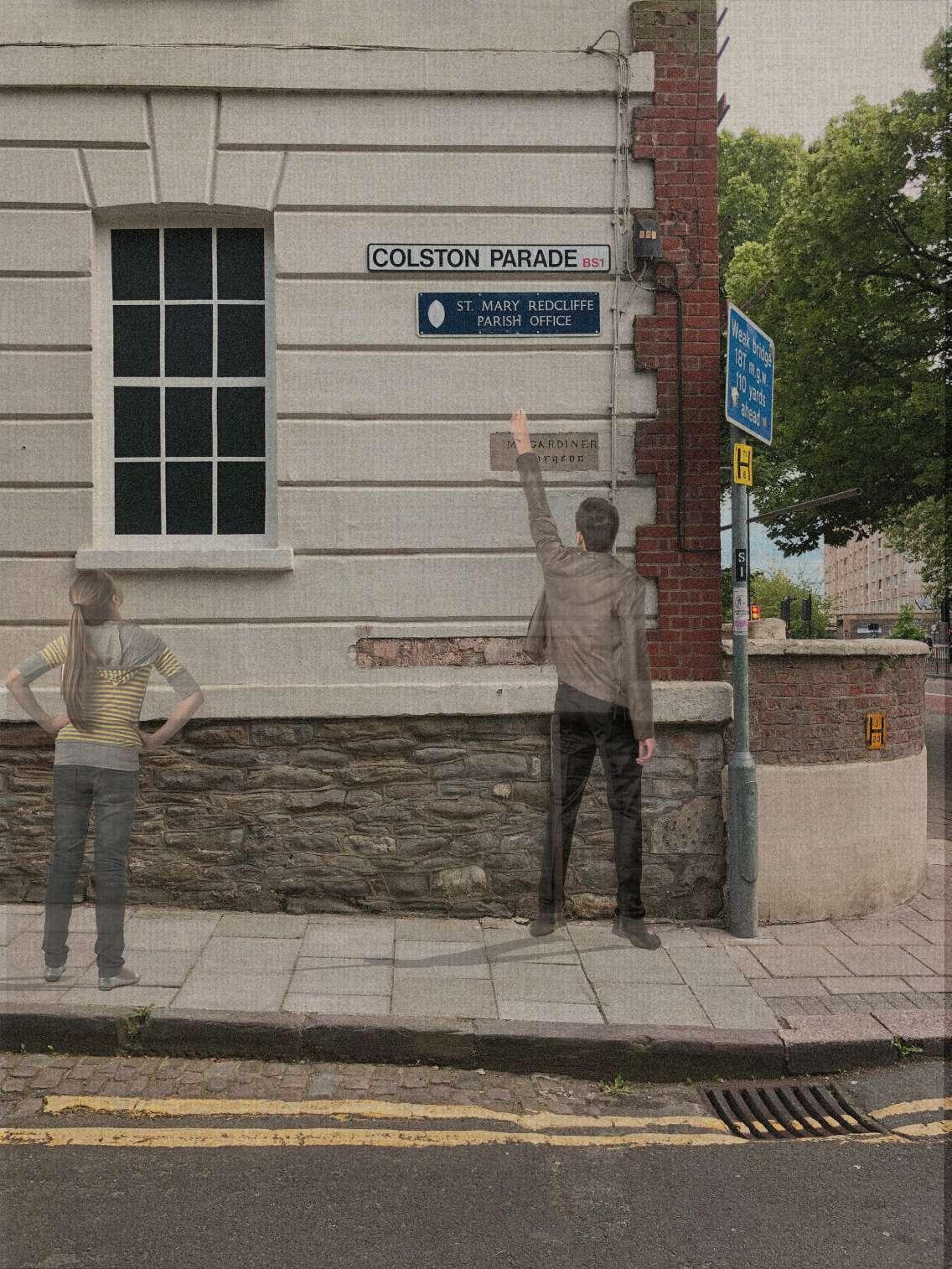

The diversity of Bristol is arguably one of its strongest characteristics. Due to the multitude of voices, and experiences, tackling Bristols troubled history has paved the way for fostering inclusion. Profiting from enslaved african labour in the 18th century, bristol was a major hub in the transatlantic slave trade. It’s colonial legacy remained embedded in the citys landscape. This is shown through the toppling og Edward Colston’s statue as well as the Colson Parade sign being torn off the street.

Modeling contemporary Redcliffe was fairly straightforward, due to the abdundance of modern day mapping technologies. This therefore allowed us to dive into the multifaceted city and understand its deep rooted histories and how it chooses to communicate them in modern day. ‘The Architecture of City’ by Aldo Rossi discuses this idea of collective memory, and its importance in shaping the identity and meanign of cities. Rossi rejects the idea that urban artifacts can be stood solely but instead argues that cities are repositories of shared experiences and cultural values.

The layers of history present in Redcliffe is a clear takeaway from this Temporal project. The way in which the city is able to reshape itself and document these changes shapes the way the people inhabit the city. Moving into tectonic; I aim to focus on these stratified stories and how they can be communicated through model making.

Dictated by the government for too long, the city finally decided to take control and rewrite the narritive.

<https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3722437>

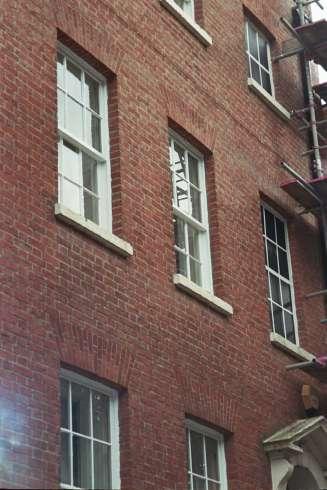

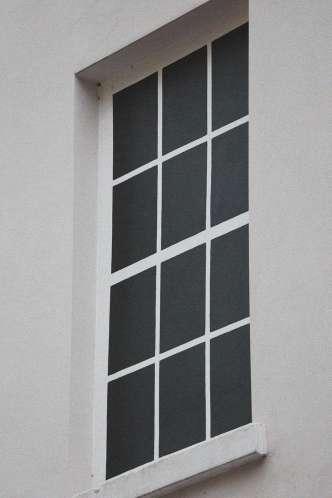

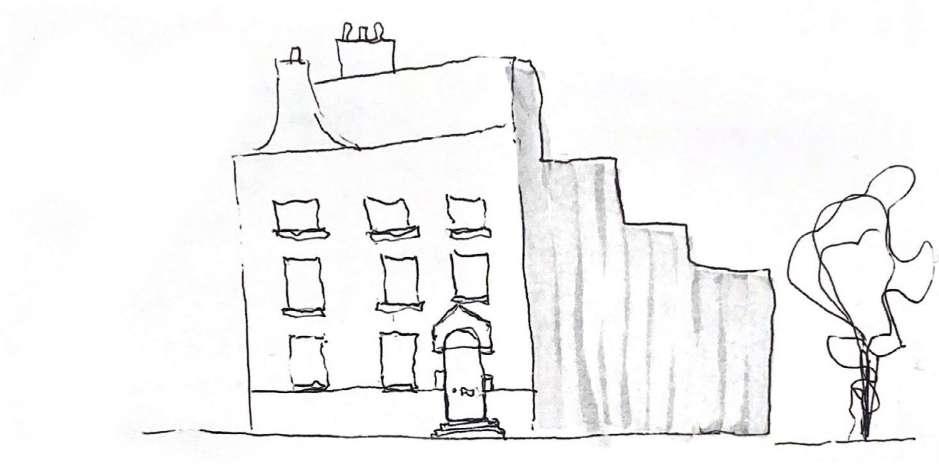

Initial observations and photographs of the site. The front presents a well kept and pristine facade whereas the back communicates a neglected, derilict building. Done purposefully to preserve the church facing facade. This begs the question; who has agency over these buildings, the government or the people in the community?

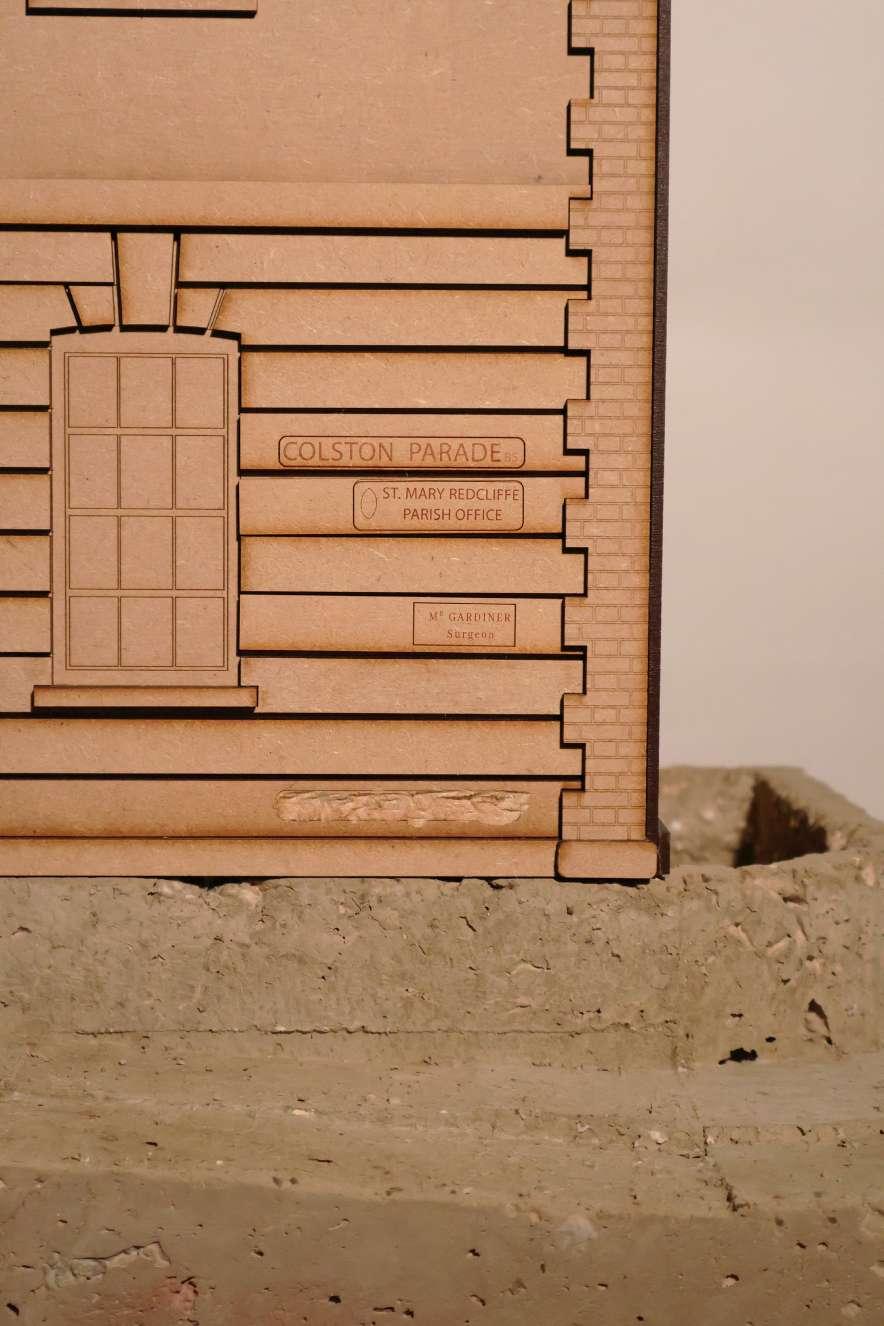

‘St Mary Redcliffe’s parish office is within the former premises of Mr Gardiner, who had the equivalent of a GP practice in the area from the 1840s to the 1890s, and was also surgeon to the Great Western Railway and Bristol Gaol.’

A term applied to manuscripts in which the original text has been scraped or washed away, in order that another text may be inscribed in its place.

Our palimpsest of 12 Colston Parade, showing the layers of history that is present beneath our building. The medieval well, the caves, the tunnel and the roads all tell the history of the street.

The Facade also depicts a visual palimpsest. Different ownerships of the building throughout time tells the narritive of the building to passers by. Furthermore the tearing down and subsequent moving of the Colston Parade sign after the Black Lives Matter movement visually documents the streets troubled history; communicating the the viewers what this street once stood for and the actions of the people in response .

Freud’s analogy of the mystic writing pad resonates with our approach to 12 Colston Parade, where layers of memory are constantly inscribed and erased The project emphasises how the site holds historical imprints; from the Colston Parade sign to the underground tunnels, each layer revealing traces of what once was, shaping the present

The creation of facades meant to deceive or present an idealised image.

This false facade was designed to maintain aesthetic harmony with St. Mary Redcliffe Church opposite, preserving the street view while hiding the chimney and real features behind it. Although it’s a fake facade, it still carries weight and history, with the signs, documenting different stages of the buildings ownership

Following the narritive of preserving the facade facing the church. Even to the point where the building starts telling a lie.

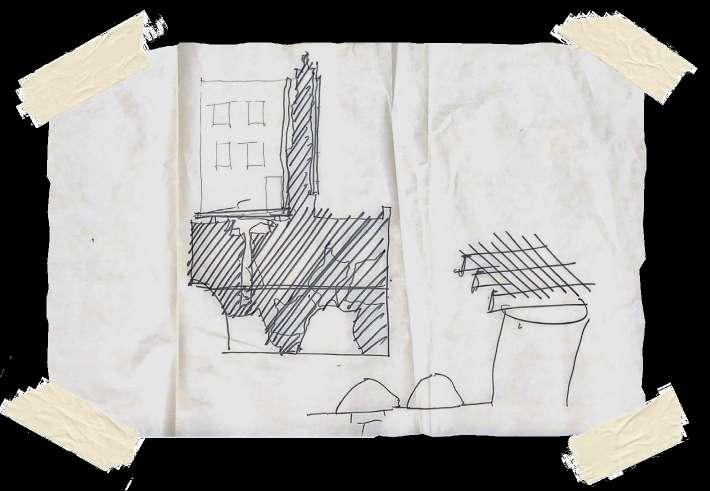

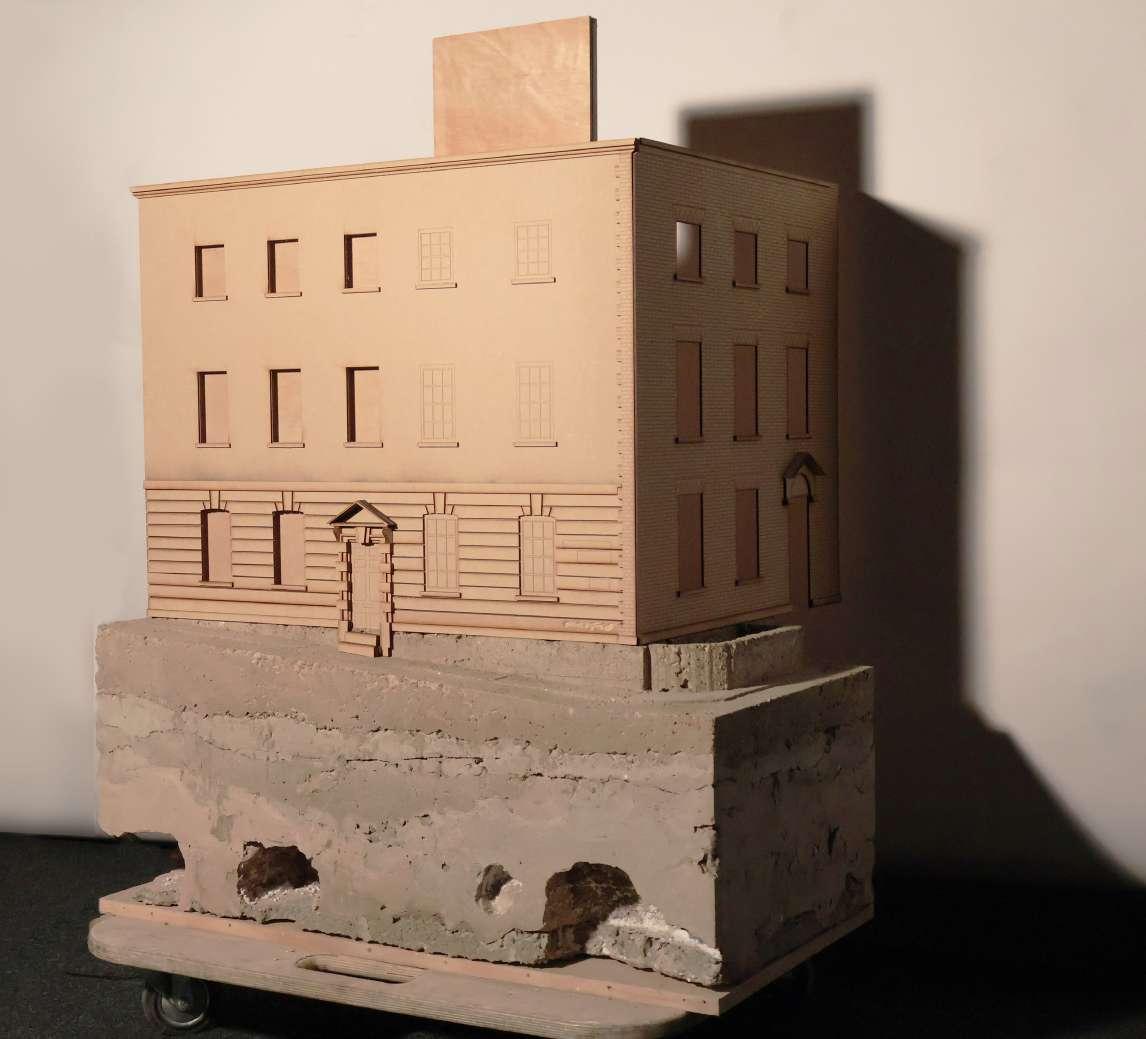

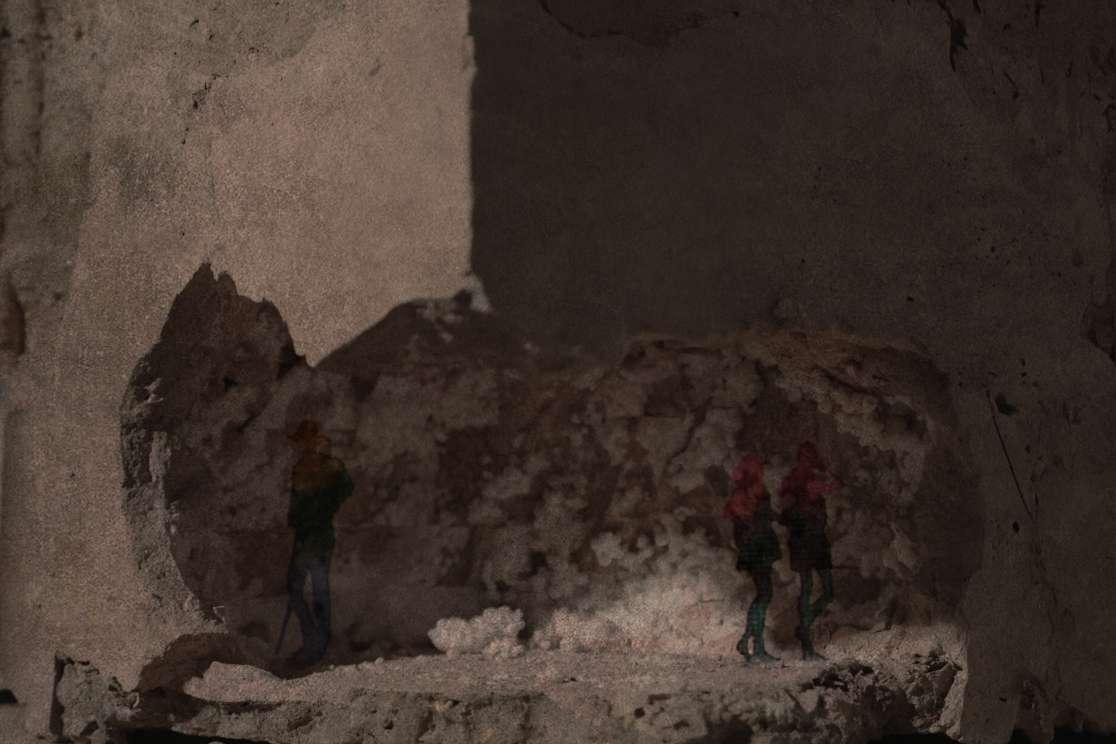

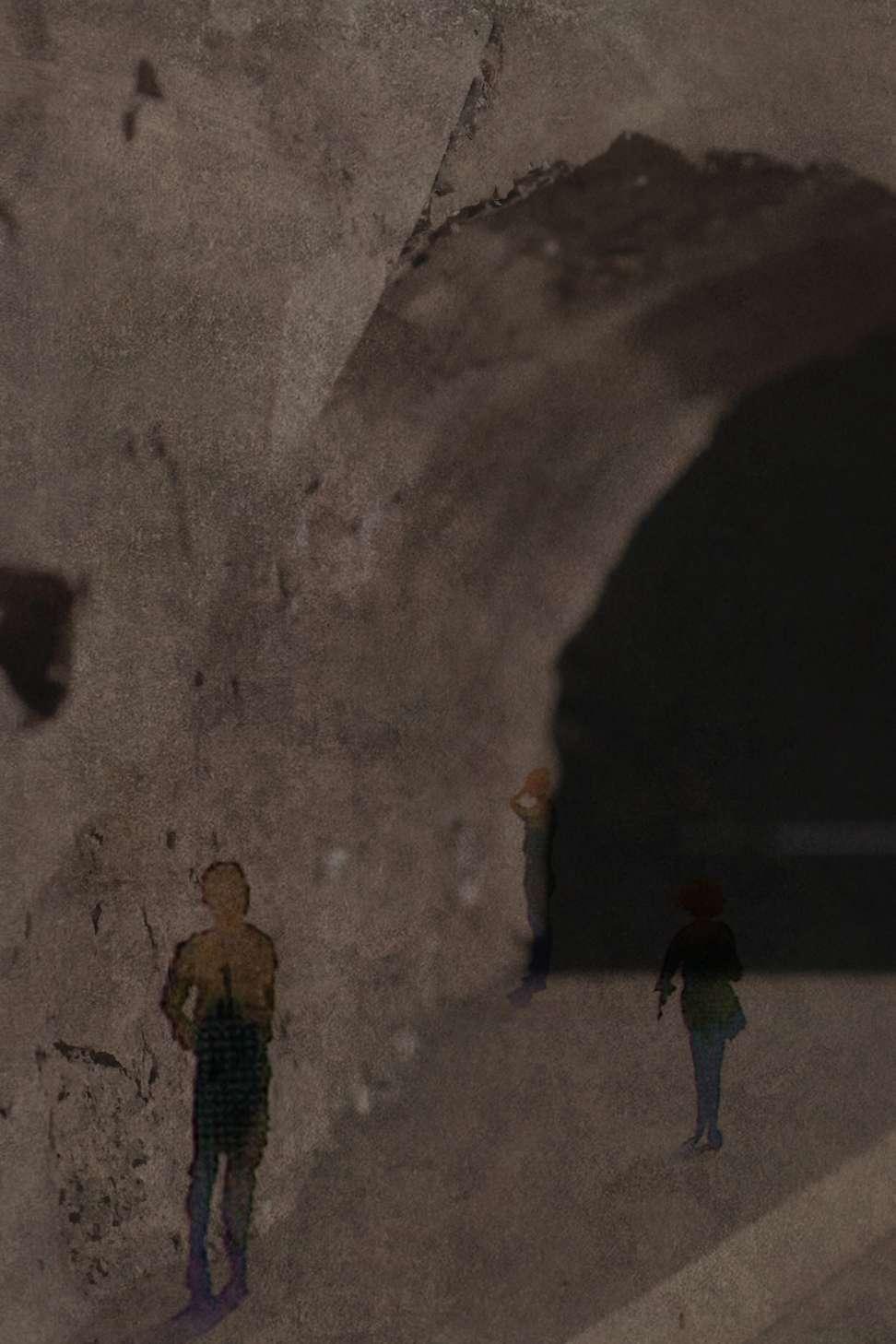

The history of 12 Colston Parade lies in its foundations. A different world exists beneath the urban surface. layers of history include the tunnel, the caves, a well and the original chimney.

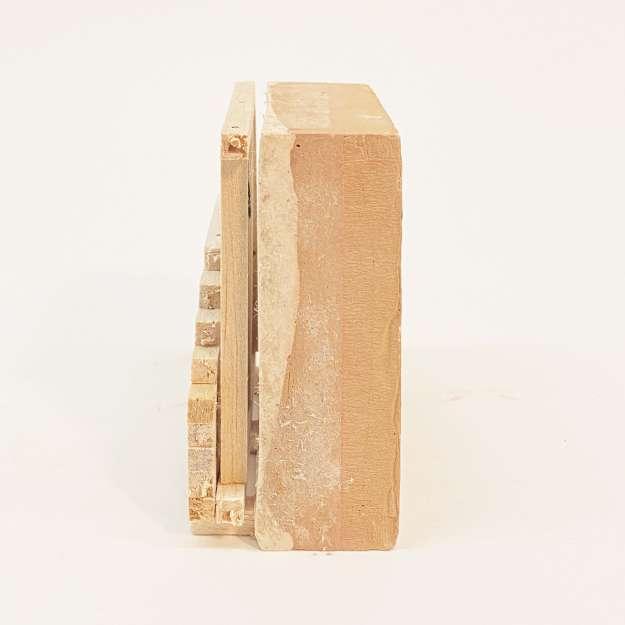

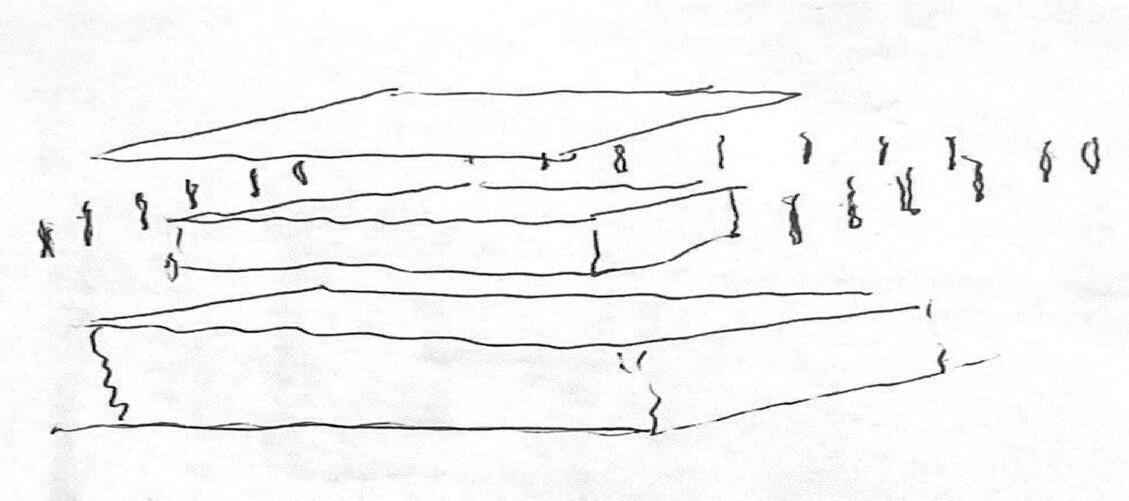

The heavy, weighted base juxtaposes the thin synthetic floating facade.

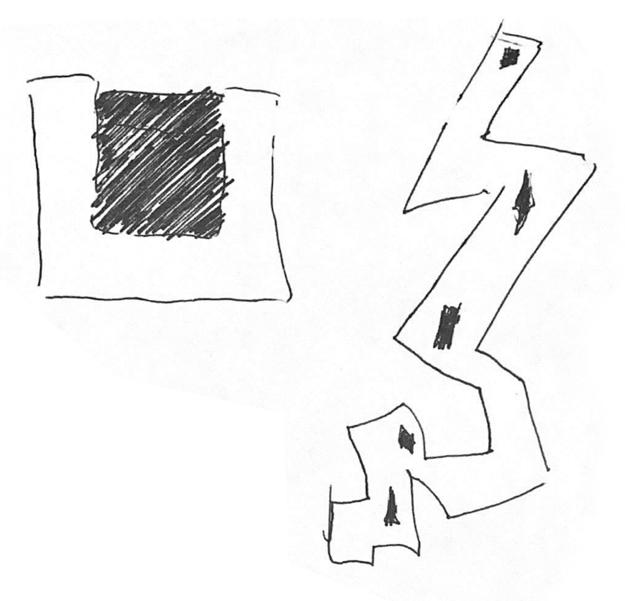

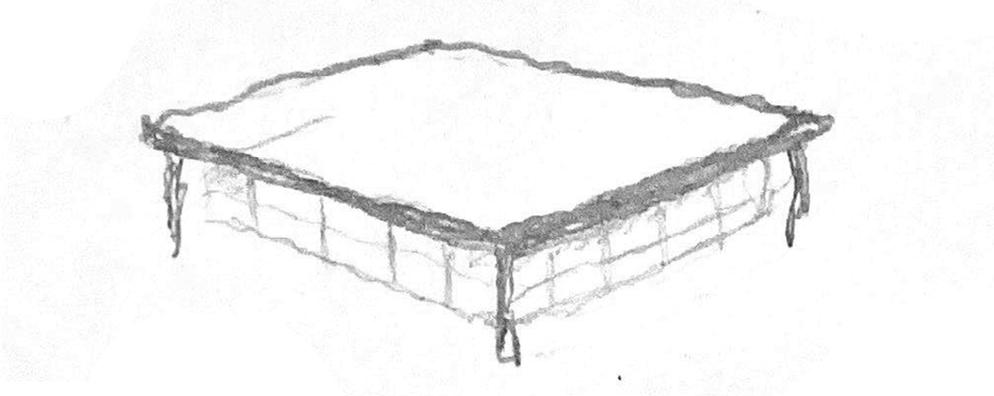

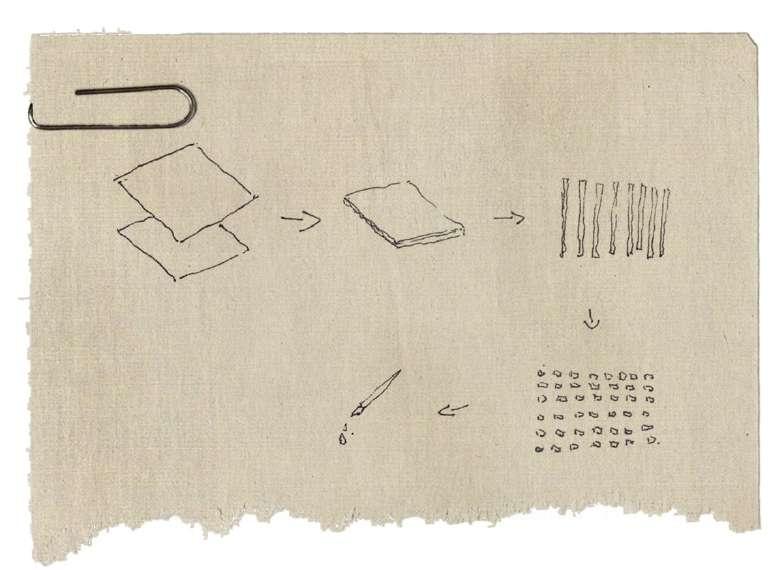

We experimented with various methods for creating our base, focusing on clearly defining the historical layers through the model. To achieve this, we used multiple materials, casting them in distinct layers. The urban layers will be represented using heavy aggregate concrete, while the ‘red’ cliff of Redcliffe will be crafted from a soft, red-toned plaster.

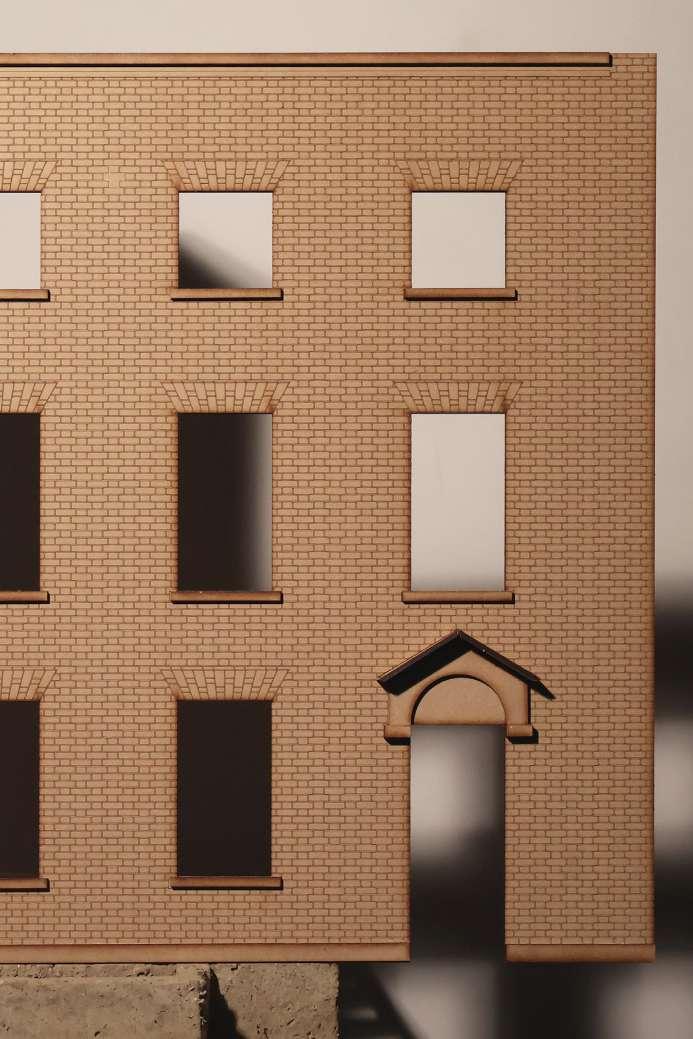

Following the same successful strategy from the test models. we cast our base in layers. Each a different mix. Our facade was carefully handcrafted - communicating the delicate lightweight existing facade. Made out of thin MDF and loosely laser cut. We aimed to highlight the falseness in the facade, the ‘disneyland’ of it all. The illusory surface invites questions about authenticity and perception.

Through this process, we engaged with Freud’s notion of memory as a layered construct, where what lies beneath often shapes the present more profoundly than what is visible. The final assembly is not just a model—it is a narrative of memory and transformation.

This model captures the hidden depths of 12 Colston Parade, revealing the building as both artifact and archive. Beneath its surface, tunnels, caves, a basement, and a well tell stories of Colston Parade’s layered past, each element an imprint of time. As well as centering on the building’s facade, our model pays homage to the subterranian—where history lies compressed, like layers of a palimpsest. Each stratum holds the traces of Redcliffe’s transformations, a physical testament to Aldo Rossi’s theory of permanence, where architecture becomes a vessel for memory, extending beyond mere function.

Yet, above ground, the building presents a facade that deceives. Similarly to “Collage City,” this facade is a fabrication, a ‘Potemkin’ illusion crafted to preserve a curated history, concealing the building’s true character. The ‘disneyland’, painted windows and plaster-rendered walls project an idealised facade, crafted to align with the grandeur of St. Mary Redcliffe Church, while erasing traces of the building’s own narrative.

Through this model, we confront the dialogue between permanence, ephemerality and authenticity. It challenges the viewer to read between the layers and consider what stories are buried, preserved, or fabricated in the architectural landscape—urging a deeper exploration beneath the surface of memory and place.

In Praise of Details

Reflections after the Review

A painted ‘Disneyland’ false facade

“A Potemkin Village is a constructed space built solely to perpetuate a version of reality that does not exist”

- Gregor Sailer

The idea of adapting existing buildings to the emerging world around us.

Recording and representing ‘intervened’ buildings through drawing. Our unit wide archive will display new and old precedents that show the different ways one can intervene in a building. Creating six key drawings, parti, experience and detail, will help us understand and analyse a building at different scales and depths.

Bollack’s book explores the interplay between historical preservation and contemporary architectural interventions He advocates for a nuanced approach to adapting old structures, blending respect for their historical value with the creativity of modern design. He categorises architectural transformations into five main typologies:

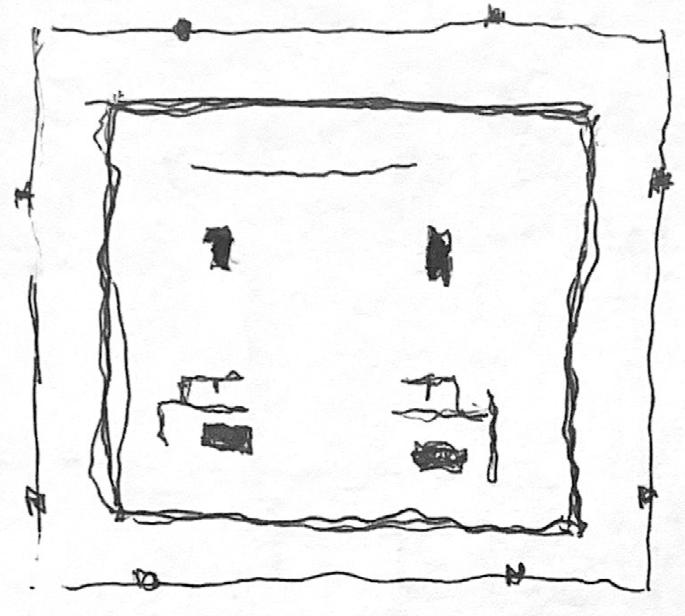

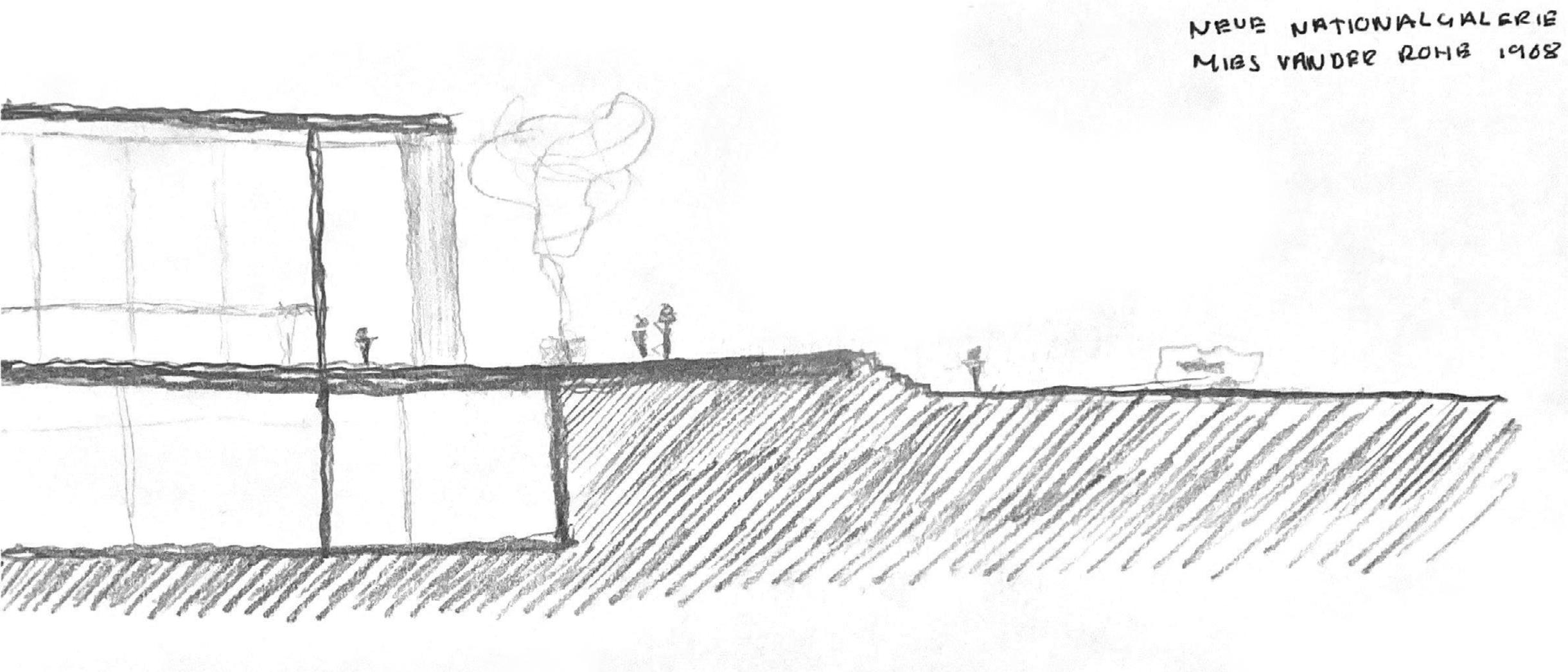

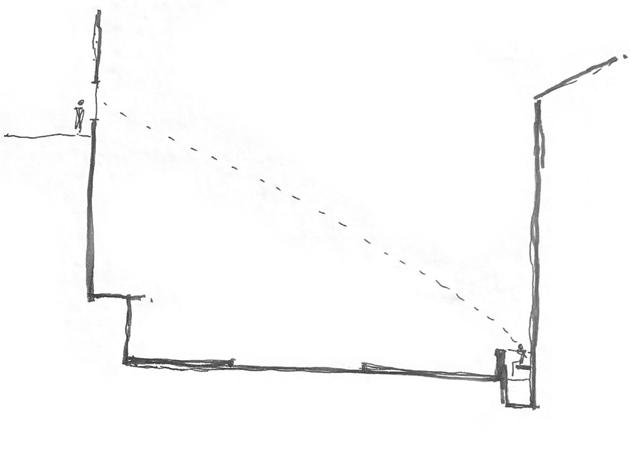

Parti - Devoid of detail; a conceptual diagram communicating simple form

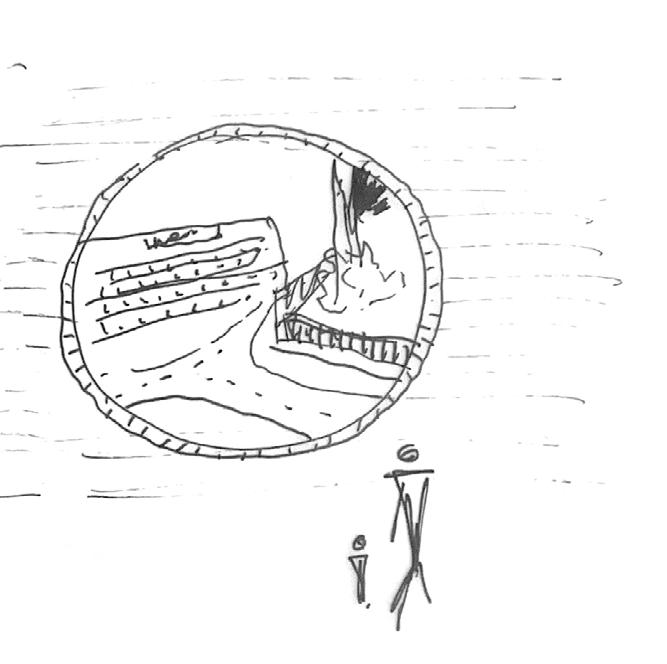

Experience - Observing an emotional experience; capturing a moment within the building

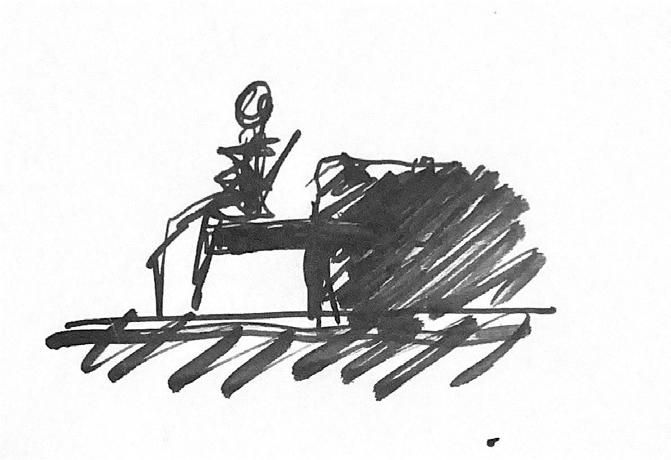

Detail - Defining a detail; the detail informs the whole and the whole informs the detail

Berlin has a layered and tumultuous history, heavily influenced by events like World War II, the division of the Berlin Wall, and subsequent reunification. This history created a cityscape where historic ruins coexist with bold contemporary architecture, making it an ideal case study for exploring how new architectural forms can respond to and transform old structures.

‘With juxtaposed interventions, the addition stands next to the original building and does not engage in an obvious dialogue with the older structure. The original remains fully legible; there is no blurring of boundaries, no transfer of architectural elements, no architectural “call and response.”

- Francois Bollack

Daniel Libeskind

Juxtaposition of new and old Parti

Libeskind’s Jewish Museum is a clear example of juxtaposition The angular design of the new structure contrasts dramatically with the traditional Kollegienhaus, emphasising the rupture in history it represents.

Confusing and winding circulation Parti

A fragmented, zinc-clad structure with sharp angles and voids that symbolise the brokenness of Jewish history in Germany.

This building stood out during the trip, offering a unique experience compared to other museums. It intentionally creates discomfort, raising the question: Should museums remain neutral, letting visitors form their own narratives, or guide and manipulate the experience to evoke a deeper connection?

Although this building doesnt fit neccesarily with Bollocks typologies of intervention, its clean and simple form peaked my interest. The majority of the building being subterranean allows for a distinct separation from outside, creating a more intimate experience.

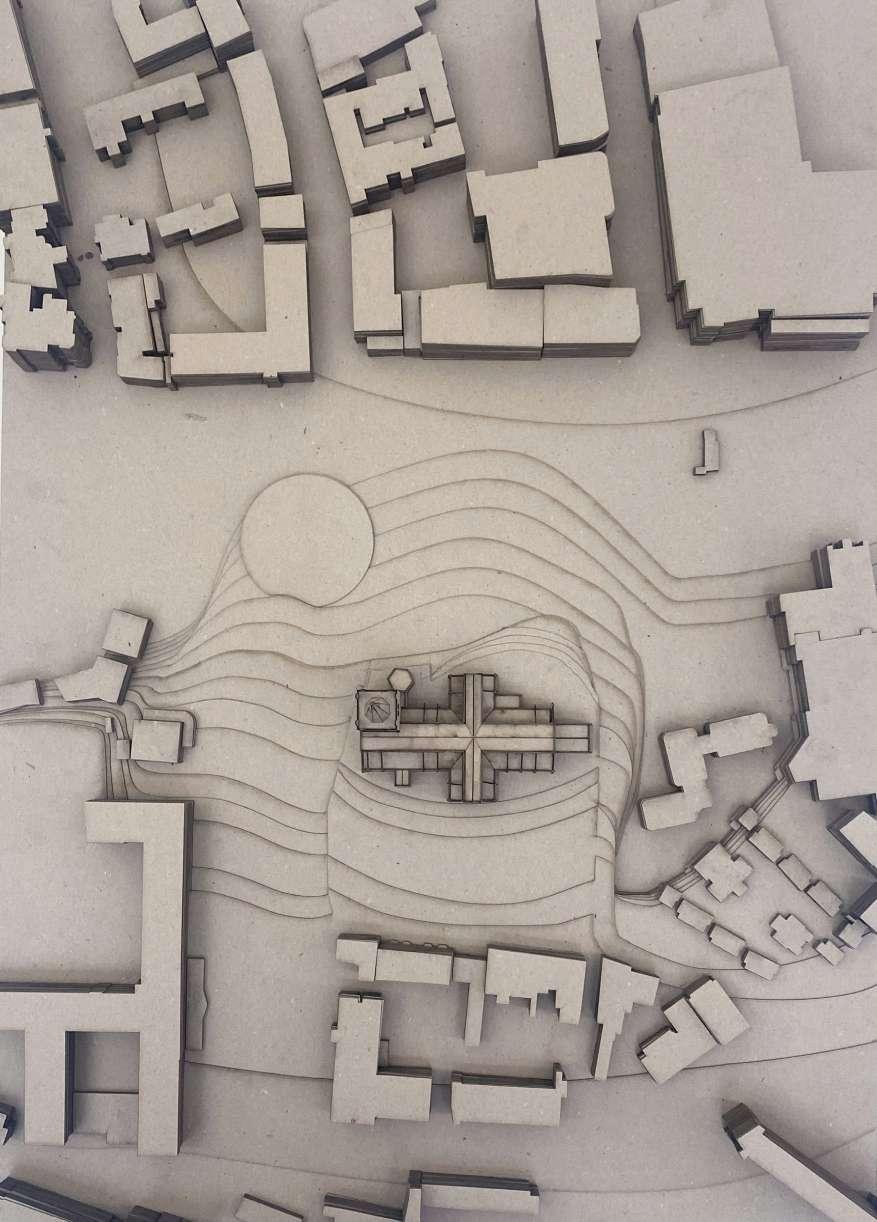

Over the centuries, Redcliffe has been a gateway for countless immigrant communities, each leaving behind traces that have shaped the area’s rich and layered history. This intervention is inspired by these stories, aiming to amplify the voices of past and present immigrants while weaving their experiences into the fabric of the site.

Redcliffe stands as a kaleidoscope of social and economic realities tied to immigration, and my project seeks to honor and preserve these diverse histories through storytelling. By tracing and celebrating these cultural imprints, I aim to reimagine Colston Parade’s future, aligning its historical significance with the evolving needs of the community today. It is a call to activate and reconnect the neighborhood through shared memory and collective identity.

The corner of Colston parade is powerful because its the intersection point between the communities of Redcliffe. To be able to dismantle the stigma towards Colston Parade and make it and the church more inviting, it is necesarry to intervene at the point of highest traffic.

Intervening through a parasitic approach allows me to honor Colston Parade’s past while introducing new narratives to the building’s palimpsest. Here, 12 Colston Parade serves as the host, with my intervention as the organism that depends on it to thrive. While the intervention creates an inhabited space for new stories to unfold, these narratives are deeply rooted in the recognition of the building’s historical tale. Without acknowledging the layers of history it holds, the new stories would lack the foundation they need to exist.

The existing Facade presents a palimpsesnt of the past, Documenting layers of a complicated history. What about todays Redcliffe? Todays people, and the stories of today.

What stood out to me was the lightwell on the West facade if 12 Colston Parade. This raised wall presents a sense of privacy that is encouraging the fragmentation of Colston Parade from Redcliffe Hill.

Considering to reassemble this wall poses the question; what is its gain?

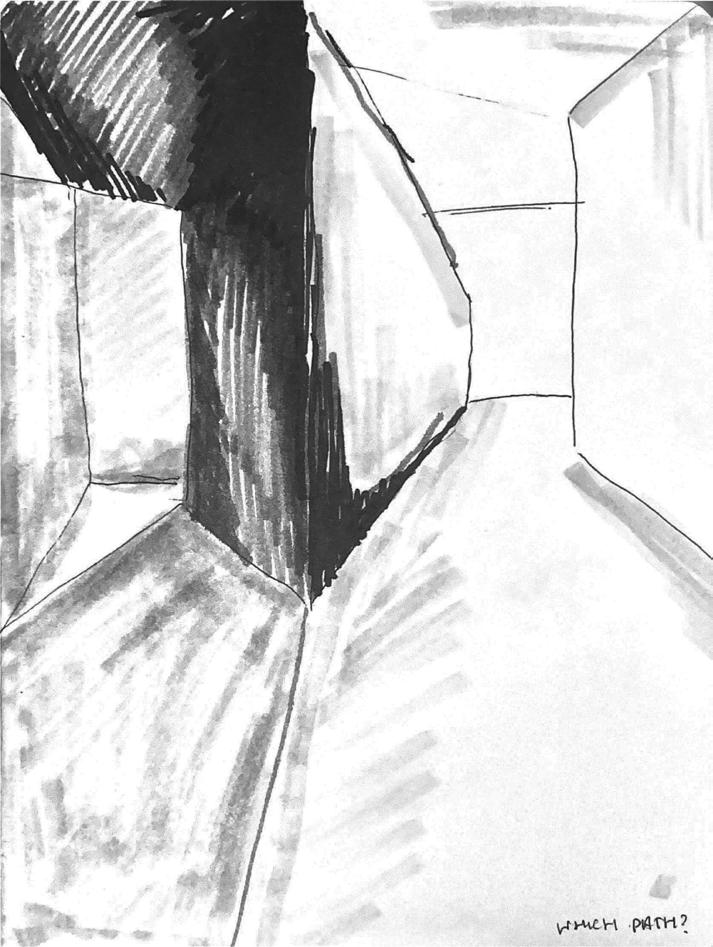

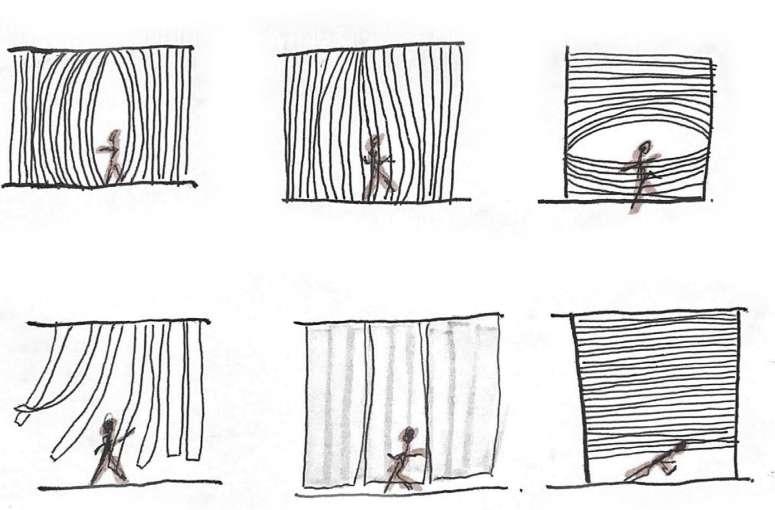

Movement through a Transient Space

The impermenance of Redcliffe Hill. A space where people pass by but dont stop. How can I celebrate this street?

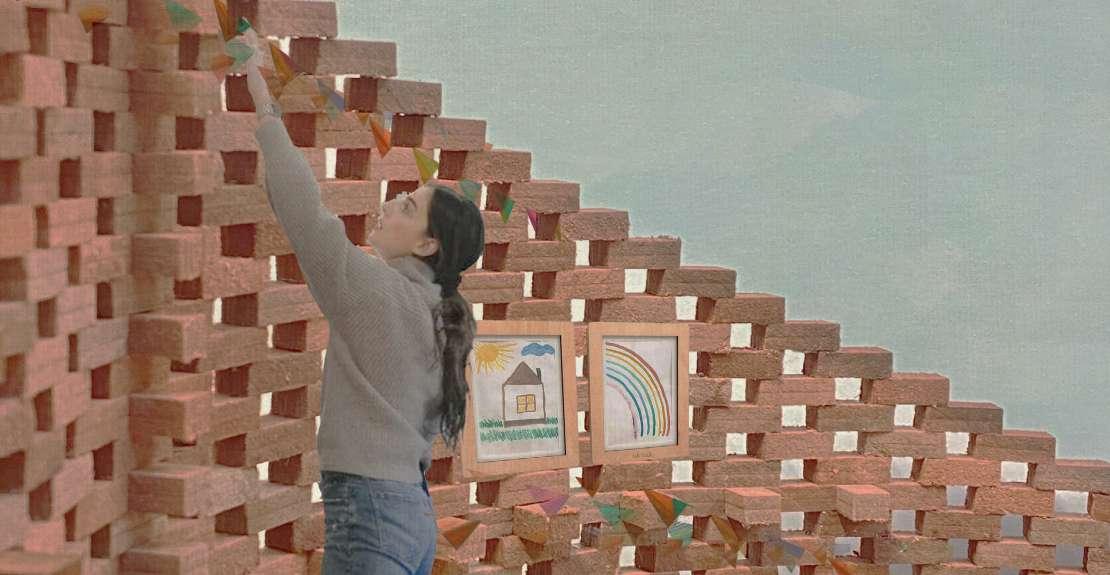

Children are a thread that ties together all the communities of Redcliffe—everyone has either been a child or cared for one at some point. By bringing themes of youth and playfulness into my intervention, I hope to break down barriers between different communities and create a stronger bond between the people and Colston Parade.

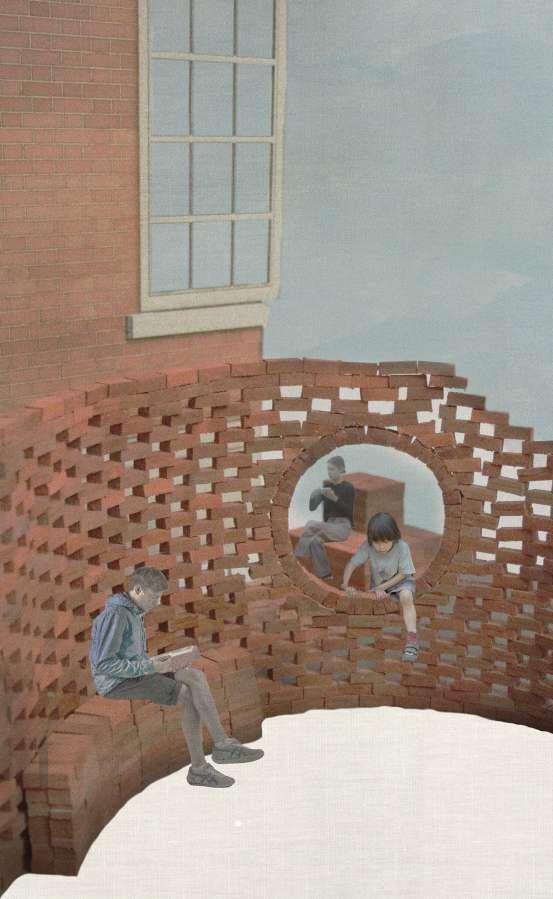

Playful interactiveness woven into my scheme. Perforated walls creating a thin softness to the scheme, making it more welcoming. Also using perforated walls to create a buffer zone between the busy Redcliffe Hill dual carriagway and Colston Parade.

Tactile and interactive patchwork to represent the the multifaceted and diverse community of Redcliffe.

Considering methods of interaction with a piece of architecture. Each communicate different experiences and each can be designed for a different age group thereby involving everyone in my scheme. Combination of all elements I aim to incorporate into my scheme

“Even a brick wants to be something. A brick wants to be something. It aspires.

Even a common, ordinary brick... wants to be something more than it is. It wants to be something better than it is.”

- Louis Kahn

the community: How my intervention will bring the people of Redcliffe together

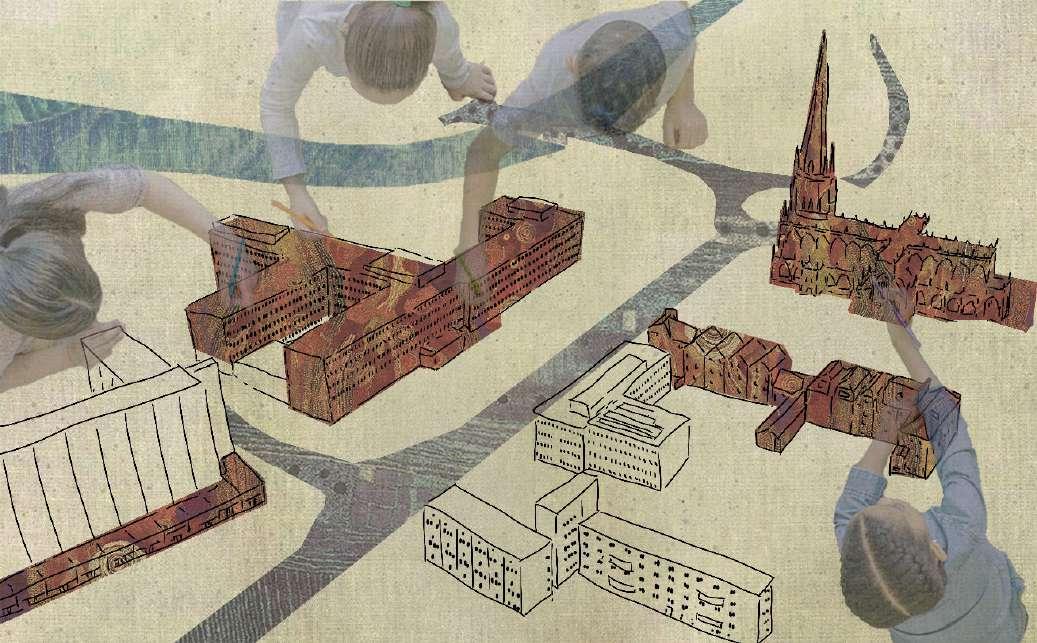

Exploring the fragmented elements of Redcliffe, illustrating the connections required to shape the community’s narrative. It serves as a tool to reimagine relationships between spaces, people, and histories within the area. This collage depicts children rewriting their Redcliffe. Taking control of the narritive.

Connections to the existing building. Using steps as a tool to foster interactions and connections. Including seating next to the entrance to St Mary Redcliffe Parish Office will break the barrier between the community of Redcliffe and the church.

Connecting the different elements of Redclifffe together through pathways. Allowing people to interact with the building how they please.

Connections to the Mercure Hotel

Another method of connecting my intervention to its surroundings. Coreographing an intimate exchange between the user and the refugee residents of the Mercure Hotel.

Framing Redcliffe hill, as well as St Mary Redcliffe, paying homage to Redcliffes history whilst simultaneously adding new narritives.

A reflection space; a breathing space; a resting space. A plinth to step up on to - this can be used however the user pleases to express themselves.

Richards, Stephen . 2013. 12 Colston Parade, Bristol <https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3722437>

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/76/25/4e/76254e954d9b7d744f567d3abd0b0cec.jpg

Françoise Astorg Bollack. 2013. Old Buildings, New Forms : New Directions in Architectural Transformations (New York: Monacelli Press)

‘Gallery of Jardín Agua Zarca / TANAT - 2’. 2020. ArchDaily <https://www.archdaily.com/974184/jardin-agua-zarcatanat/61c5c60010cf2e0164b3a5f6-jardin-agua-zarca-tanat-photo> [accessed 2 December 2024]

‘NUMBER 51 and ATTACHED BASEMENT AREA WALL, Non Civil Parish - 1282160 Historic England’. 2024. Historicengland.org.uk <https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1282160> [accessed 29 November 2024]

Richards, Stephen . 2013. 12 Colston Parade, Bristol <https://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/3722437>

Rossi, Aldo. 1982. The Architecture of the City (Cambridge, Mass, Mit Press)

Rowe, Colin, and Fred Koetter. 2009. Collage City (Basel: Birkhäuser)

AI Declaration: I acknowledge the use of AI in the form of ChatGPT to summarise readings from notes and as a paraphrasing tool