PARADOX OF VALUE

The threatened habitat of mangroves in Mumbai

“We need to learn from indigenous people, how we can create economies that do not destroy the earth and push biodiversity extinction instead value them and preserve them”

-Vandana Shiva, Environmental activist

Paradox of Value

The threatened habitat of mangroves in Mumbai.

Rasika Patil

MLA, Studio 4

BARC0119: Landscape Thesis

Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Anthony Powis

Module Coordinator: Dr.Tim Waterman

Co-Coordinator: Tom Keeley

The Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL

July 2021

(word count: 7430)

I would like to thank Dr. Anthony Powis, Dr. Tim Waterman and Tom Keeley for all the guidance with this thesis. My mother Darshana Patil whose photographs I have used in some parts of the thesis.

The unforgettable, destructive floods of Mumbai 26 July 2005

“The challenge of today is to save the planet from further devastation which violates both the enlightened self-interest of humans and nonhumans and decreases the potential of joyful existence for all” – Erne Naess.

I was born and raised in the coastal metropolitan city of Mumbai. Living in Mumbai, one gets used to the heavy monsoon rains because they come and go by every year and last for about 3 months. Every year the city faces the threat of flooding in the monsoons, people crib and complain, the newspapers have images of floods in different parts every day and yet we continue to live the same way even after 2005. The deadly floods of 2005 are unforgotten by every Mumbaikar. All I have is a memory of being stranded for hours on the bus coming home from school, whilst people struggled to walk back in deep waters up to their waist which seemed highly dangerous. The floods of 2005 claimed livelihood, houses, and lives of people as well. The damage caused to the city and its people was devastating. The city was brought to a standstill. Who was responsible for these deadly floods? Why wasn’t the city prepared to combat this situation? Now Mumbai then back in1800s called Bombay was an archipelago comprised of seven islands flanked by mangroves and was stitched together by cutting these mangroves and reclaiming land. Mumbai now is a peninsula city. Despite being aware of the history of the city, developers kept building and adding pressure on these flood-prone lands. The floods were a repercussion of us being ignorant of these critical facts.

When the city flooded in 2005, it wasn’t just the heavy rains that happened to occur at high tide but the water that fell had nowhere to go. The floodwaters swirled through the city for days (Anand, 2017). The primary cause was the inefficient antiquated drainage system. The stormwater drainage currently present in Mumbai dates back to the beginning of the 20th century, incapable of carrying the extremely heavy rain that hit the city (Gandy, 2008). The drainage system was incapacitated to stop the seawater gushing in during high tide. The secondary cause was unplanned construction in the city, low-lying areas without any environmental clearance were sanctioned for large-scale urban construction of commercial complexes in Northern Mumbai. No environmental clearance is mandatory in Northern Mumbai for the construction of large urban projects (Linn, 2012).

The third factor that could have controlled or at least reduced the impact of what the city faced is the destruction of mangroves. From 1990 to 2005 around 40% of these mangroves were destroyed

along the Mithi river for the construction of the large commercial complex. Hundreds of acres of these ecosystems have been reclaimed by builders for construction. Mangroves were looked upon as mere wastelands whereas they protect the coast by creating a natural barrier and drainage system.

The 2005 floods were a wake-up call to the people and the authorities of the city that climate change is real and rising sea levels are going to be a threat to the city. Mumbai frequently figures among the top five most vulnerable cities to Climate change. The city faced these adverse effects due to mere negligence, illegal constructions, and undervaluing of the mangrove ecosystem. Mangroves are more than just forests, they are the coastal defence of the city which sequester four times more carbon than our regular tropical forests. They provide habitat for thousands of species at the marine and forest levels. In Mumbai, the entire local coastal community of the Kolis and Aagris depends on these mangroves for their daily bread. Even despite all these benefits, Landscape of Mangroves has been undervalued by the authorities, builders, and developers as well.

Governmental action is absent in the environmental plans that would address the insecurities of the human-led destruction as seen during the 2005 floods (Parthasarthy, 2011). Also, the two mega infrastructural projects that are talked about are a threat to the city’s future. The coastal road project being built in the sea is endangering the flora and fauna of the aquatic species and impacting the lives of people that depend on the same. Whilst the second one is the most celebrated Navi Mumbai international airport being built on the estuary by destroying these mangroves is again a threat to the local communities and the city.

These landscapes have been undervalued in the past and if they continue to be undervalued it will result in an uncertain future for the city as it is predicted that with the current rate of urbanization Mumbai is going to be underwater by 2050. Not just that but in case of any natural calamity like a tsunami the city will be washed out within seconds and these mangroves are the only fighting chance for the city’s survival. These conversations and issues have been raised in the past but apart from putting a protection tag not much has been done for them, they continue to be disregarded and undervalued. The thesis Paradox of value will talk about the social, economic, and ecological value of landscape systems as a whole in combating climate change and creating a viable city concerning mangroves as the valued landscape for flood mitigation and rising sea levels and highlight the grave danger we keep engulfing open ourselves every

day. The thesis intends to investigate in terms of advocacy what can we as a community of landscape architects and practitioners contribute to these landscapes and the community for the viability of the city.

Chapter 1 will discuss the theory of the Paradox of Value and the vitality of landscape systems. I will also look at the factors considered for the tangible and intangible evaluation of these ecosystem services. What does it mean to economically evaluate ecosystems? Chapter 2 focuses on the Mangroves of Mumbai and the value of these landscapes to the local community vs their value to the government authorities and the impact on the city due to these values towards the mangroves. Chapter 3 is about the role of landscape practices while discussing the work of environmentalists and experts concerning the New Mumbai airport site which is being built on land that was home to the mangroves.

The intention of this thesis is about being the voice and highlighting the Value of landscape for the local community, the Value of landscape for the city, and the Value of landscape to the government authorities to the people of the city.

A piece of writing which I resonated with and was inspired while writing this essay is beautifully summed up by Johanna Gibbons in this book ‘250 Things a Landscape Architect should know’ by Canon Ivers

“The city is a dynamic landscape, with an ambiguous wildness that brings us close to nature and natural process. It is this landscape that connects us all, within which, for a moment in geological time the landscape architect plays a part, conserving while curating a delicate balance of ecosystem, natural and unnatural beauty, complexities embraced with quiet conviction, the task to sustain life and create places that can be loved”

- Johanna GibbonsThe map here depicts the original seven islands overlayed with the landfilled extent of the city.

Mumbai predicted to flood by 2050 Top 5 most vulnerable cities to climate change

Source: Nikhil Anand (“Explained: How climate change could impact Mumbai by 2050”, 2019) https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/the-rising-threat-to-mumbai-6160595/)

Pneumatophores specialised aerial roots which enable these landscapes to breathe in water-logged soil

Figure 4: A black tailed gowit amongst the aerial roots of Mangroves Source: Darshana Patil (Author’s mother)

Figure 4: A black tailed gowit amongst the aerial roots of Mangroves Source: Darshana Patil (Author’s mother)

The Paradox of value

/ Chapter 1: The Paradox of value: Value of Landscapes /

As stated by economist Adam Smith, there is a well-known paradox known as the “diamonds and water paradox”: water, despite its importance for survival, is generally very cheap, whereas diamonds, despite their relative insignificance except as an adornment, are generally very expensive. The relative abundance of water and diamonds explains this paradox. Because water is generally abundant, an additional unit is usually inexpensive. Diamonds, on the other hand, are extremely rare and thus command a high price. This theory in regards to ecosystem services fits perfectly well. These systems are disregarded and the price value put on them is insignificantly low almost negligible. The benefits from nature are almost invisible from the economic perspective.

But first, let’s start with defining the meaning of the word value. Value is a word that has a range of different meanings and changes with the context it is used in. Value when considered as a noun has monetary and material associations. One of the social definitions talks about the importance or worthiness to them. Values can be both monetary and non-monetary and can be categorised into multiple factors like economical, social, aesthetic, cultural, environmental, historical, ecological and the list goes on. In this thesis, I would be focussing on a few of these aspects of value associated with landscape systems overall belonging to the larger concept of ecosystem services.

Value of Ecosystem Services

Ecosystem services in simple terms are the benefits that we extract from nature and healthy ecosystems which contribute to essential and qualitative living. These benefits can be categorised as direct, indirect or aesthetic/ethical. Food, shelter, medicines and energy from diverse ecosystems are some of the direct services we obtain from biodiversity. Indirect services are those that are delivered to us as a result of healthy ecosystems and Mangrove swamps fall into this category of benefits

Mangroves grow in salt water thus creating a semi-marine forest in between the land and the sea. They are found along the coastal margins of tropical countries in the world. The mangrove swamps house multiple species of mangrove trees which are very resilient as they hold on to the coastal soil and prevent the land from wave actions and erosion. They are grounds for fish breeding that support local economies. Now these benefits which we receive from such landscapes are termed ecosystem value. Globally these species are threatened as people are cutting them down and building shrimp

farms to add value to the land by producing a commercially viable product. But if we look at a value graph, shrimp farms contribute only a quarter of the value of the mangrove swamps.

Both economists and ecologists had failed to derive a unified approach to value these ecosystems. People from different disciplines have had contrasting units of valuing nature. To economists, it has always been monetary whereas to ecologists it was ethical. I will now look at the approaches by both these entities and compare them.

Value of ecosystems to economists

The approach of economists towards ecosystems has always been anthropocentric with humans holding intrinsic value. Environmental economists quantify environmental value by identifying “commodities” — units of natural goods and services that can be purchased in markets. But for the services that cannot be directly bought from the market are calculated by measuring the consumer and producer surplus. To explain this in theory, every person something has a maximum “willingness to pay” (WTP) for a commodity and that’s how the value for the same is determined which is very often debated by ecologists as the intangible value is very subjective and varies from one individual to the other. Anthropocentric theories are further categorised as ego-centric and homo-centric (Thompson, 2000). Often egocentric ethics go along with most theories of economists as these ethics state that everything turns out beneficial for society if it is the same for the individuals. Whereas Marxism is considered homo centric which means that they would value nature if and only it contributes to the eventual happiness of the maximum number of human beings. (Thompson, 2000)

Ecological economists emerged as a result of criticism received by various economists for their homo-centric approaches. They went beyond the standard method for measuring the value of ecosystems calculated using WTP but calculated the indirect services offered to term them as ecosystem services which have become a concept now worldwide to calculate ecosystem values yet the are still monetary associations. Dr Paul Sutton a professor of geography and environment whose research interests have been in the field of ecological economics when came up with a monetary value to ecosystem services and stated them to be double the world GDP, the backlash received from both ecologists and economists was tremendous with ecologists exclaiming that how can something infinitely valuable be tagged monetarily, whereas the economist’s critique by questioning the value of nature to be more than the market.

He agrees that nature is invaluable but is treated as something as less than zero value and thus a monetary value is associated as that’s what every individual understands.

Value of ecosystems to ecologists

Over time economists have come together and driven out strategies to put a value on nature which is invaluable. They have tried to put a financial value on the intangibles of nature like the aesthetics and beauty, it is just not about the appearance of these landscapes. Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess’s Deep ecology criticizes the economists for sticking a price tag on nature. His theory firstly talks about shifting from human-centred anthropocentrism to ecocentrism where every living thing is considered to have value irrespective of its utility and the second that nature and humans are both one rather than humans being apart from it or being superior to anyone and thus humans need to value and protect all life. Critics had widely questioned and faulted his theory for being very broad and utopian in nature (Thompson, 2000). But irrespective of the criticisms the deep ecology movement had begun a conversation about the value of nature and a transformation of approach amongst humans to nature and it remains relevant in today’s world as we face environmental challenges. But that doesn’t sit well with economists who time and again try to put a monetary value on the environment. ‘Naess has been very pragmatic about what environmental economics offer’ says (Thompson, 2000) as he talks about how our value system is not and shouldn’t be monetary. Because the valuation of a landscape is always calculated in the present time, the value of landscapes is over centuries.

Environmental ethics vs economists

Both these entities of economists and ecologists were unsuccessful to present a unified and coherent approach for evaluating ecosystem services in an attempt to aggregate and focus on a single value one of them focusing on the welfare of individuals whilst the other focused on the intrinsic value of the non-human elements along with the individuals (Norton, 2012).

Can we as a community of Landscape Architects and planners intend to create that balance of a sustainable environment which corresponds to social, aesthetical, ethical, economic and ecological values? Ecosystem service prevailed in Landscape architecture planning can be observed in Fredrick Law Olmsted’s work which in the 19th century designed parks as these entities that would clean

the air of the city and absorb carbon and that reflected in the urban planning of the city too. As early as the 19th century, his designs addressed ecosystem services and simultaneously well being of humans along with the restoration of the environment (Eisenman, 2013). Ecological knowledge was also prevalent and voiced in McHarg’s Design with nature whose projects have been in the suburbs thus he associates the success of the project when the natural process is fully understood. The basis of his design ideology and planning is focused on the value system of nature and natural sciences as his theory along with ecological science (Bo Yang, 2016). Thus ecological importance and value have now emerged dominant in landscape architecture and awareness has been increasing ever since now moreover due to climate change.

The three Value systems

Ecology, Community and Delight are the three value fields Ian Thompson categorises in his book with the same name. He bases his framework on Environmental values, social values and aesthetic values as the three values essential for landscape practitioners while approaching or designing a landscape (Thompson, 2000). Similarly, when we consider mangroves we will be analysing the landscape on three values: Social, ecological, and economic in the following chapters.

Now as we have established the theoretical aspects of value, ecosystem services and their approach in various disciplines, we will look at Mangrove swamps and their value as a landscape system globally.

Mangrove swamps

Mangroves are coastal vegetated ecosystems and are extremely productive and valuable ecosystems to the earth. A total of 118 tropical countries are bordered by these ecosystems which total a stretch of 1,37,000 square kilometres. Mangroves have been categorised as blue forest ecosystems and have made their appearance internationally as part of the discussions that focus on the conservation of these habitats. They offer us a variety of ecosystem benefits and services like sequestering massive quantities of carbon from the air and cleaning the air, efficient coastal protection and preventing soil erosion, adapting to the rise of sea level, acting as fish breeding grounds and house vital marine life, protect coral reef, a habitat for endangered wild birds and animals. Despite these invaluable benefits, mangroves have been destroyed and degraded globally at a

rate of 1-2% per year and this is alarming in the past 20 years we have lost a total of 35% of these mangroves. The biodiversity loss is immense directly impacting climate change. In response to this ecological economists and researchers began to economically evaluate and quantify these services as discussed above and whilst this is done there has always been a gap which can be fulfilled by analysing cultural ecosystem services associated with ecologies like mangroves that will help us determine its full value to humans, which comprise of the non-material and intangible benefits.

The services that the mangrove ecosystem offers are rather emotional and cultural than applying a market value, especially to the local communities and the stakeholders who depend on their livelihood and their daily bread on these landscapes. This recognition is widely missing and that is one of the aims I am looking at. The inclusion of the local communities in their co-existence with these landscapes is going to help us create a sustainable ecosystem. Pavan Sukhdev, an environmental economist, states the statistical ratio of economic to cultural value in countries like Brazil, India and Indonesia and the percentage of these ecosystem services in GDP is merely 10-15 % but their value to the poor or the local dependent communities in the above-mentioned countries is about 45-95 %.

In the context of India which contributed to 45% of South Asia’s mangroves flanked the country on its east and west coast. A total of 4.5 million people from both India and Bangladesh depend on the mangroves in midst of the two countries which is the largest carbon sink mangrove forest in South Asia. The cultural and social value is impacted largely in India because of these artisanal fishermen communities. The mangroves of the Sundarbans are yet widely protected now as the Sundarbans forests have received the recognition of a world heritage site but that isn’t the scenario in Mumbai. The mangroves in Mumbai have been highly neglected and undervalued. The government authorities and policies have failed to do justice to these ecosystems with their new Climate Action Plan, the ongoing infrastructural development and the alarming threat of rising sea levels whilst facing the fear of flooding.

The paradox of value fits exactly with the mangroves as an ecosystem, where due to their abundance and lesser economic profits they have been often ignored as we saw in the theory of diamonds and water. Why are these mangroves being undervalued? and who is affected by this? are the questions I will be looking at in the following chapter.

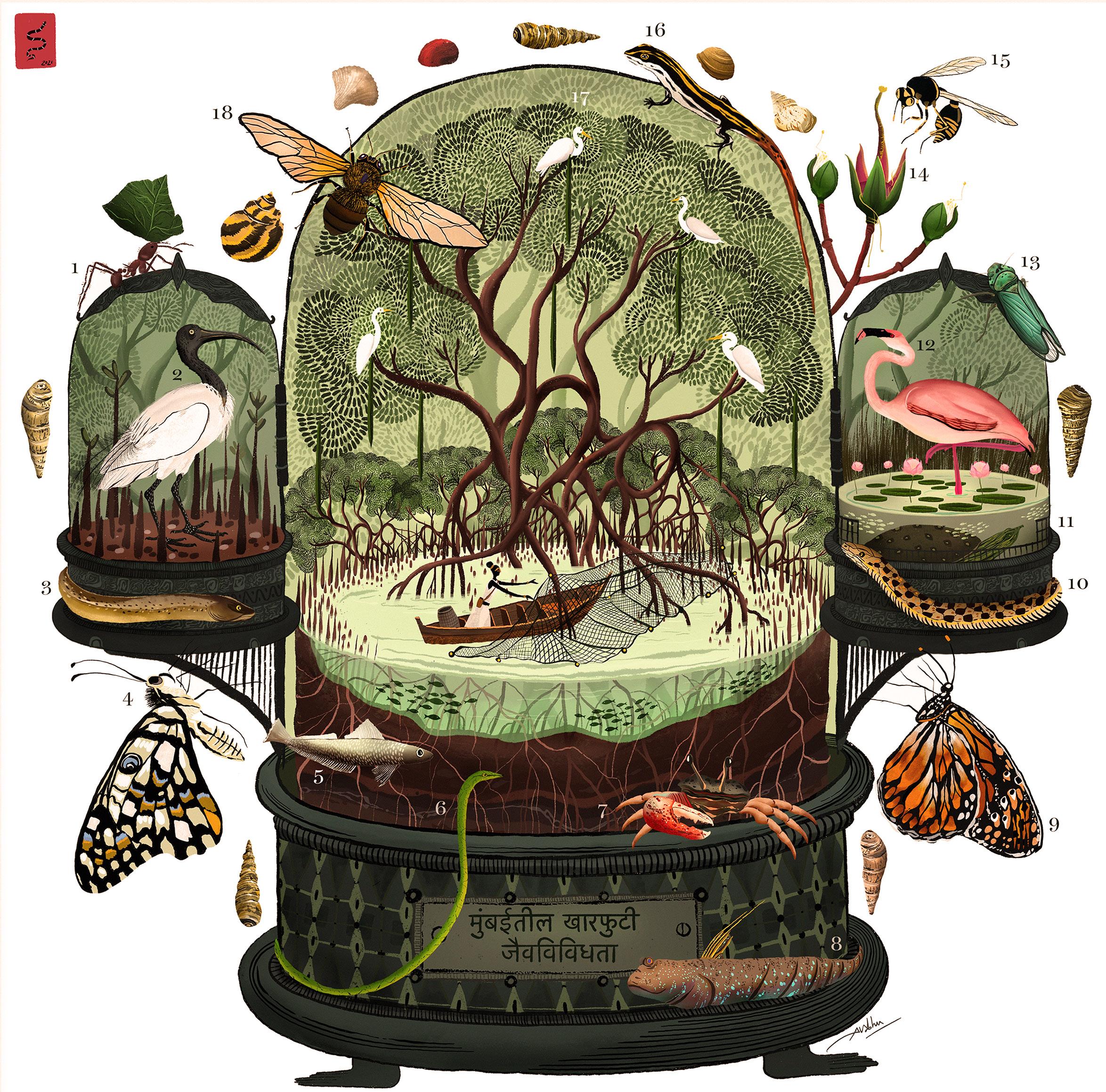

Mangrove awarness art initiative for Conservation of these ecosystems

The rich biodiversity that encompasses within

Figure 7: Migratory flamingo birds that Source: Darshana Patil

Figure 7: Migratory flamingo birds that Source: Darshana Patil

within these landscape is incredible

live on the mud flats of the mangroves Patil (Author’s mother)

Figure 8: Koli Fishermen navigating through these mangroves for fishing Source: Vanashakti(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kzVHf7f4b8)

Figure 8: Koli Fishermen navigating through these mangroves for fishing Source: Vanashakti(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7kzVHf7f4b8)

/ Chapter 2: The Protagonists and the Antagonists /

Mangroves of Mumbai

The city of Mumbai is a combination of land which is static in nature and is flanked by the sea which is a dynamic entity. It is given that over time the coastline of the city gradually will erode and thus to safeguard the coastline Mumbai has mangroves which are solid and much more dynamic than water. Mangroves are intertidal vegetation and they hold the shoreline intact, thus their value to the city is ecological. They have been a part of the landscape of Mumbai since the time they were separate islands but unfortunately destroyed to reclaim the land. Now a large population of Mumbai sits on unviable land. The depletion of these ecosystems is due to increasing urbanization and projects that have been environmentally destructive causing damage to not just the mangroves but to the delicate marine and coastal ecology. The undervaluing of these ecosystems has been constant by urban authorities even despite promising to take measures for flood mitigation post the 2005 floods. (Hans Nicolai Adam, 2022). The impact of this undervaluing is directly on the Kolis, the artisanal fisherfolk community. This chapter will focus on the two main actors that are involved in telling the story of the mangroves of Mumbai where both have contrasting value ethics towards these ecosystems. The Kolis are the protagonists and the government authorities are the antagonists in this story of mangroves.

The Protagonist: Koli fisherfolks

The Kolis have been living in Mumbai along the coast ever since the Portuguese invaded Mumbai. The established fishing hamlets in the various parts of the city along the coastal edge are called the Koliwadas which means a home that opens to the sea, comprising their settlement and workplace boundaries including commonly owned land as well as fishing grounds in the sea. . These Koliwadas were widely spread across the coast and on the banks of the rivers and creeks catering to the city of Mumbai, Navi Mumbai and Thane and over the course of time they were subjected to the rapid urbanization post the invasion overtaken by the East India Company, therefore condensed and relocated to smaller clusters. Urbanization had a direct impact on these communities who depend on the coastal ecologies which have been deteriorating and adversely affected as the mangroves have been eaten due to the reclamation of the sea and construction of the sea link. Apart from this, the untreated sewage from the growing city and surrounding industries has been poured directly into the sea as well as the mangroves, reducing the quantity as well as the quality of the catch they yield. Climate change,

developmental pressure, and ecological deterioration have led to uncertainties in fishing as a livelihood for the Kolis.

The Mangrove ecosystem provides a rich breeding grounds for marine life and they have an unbreakable bond with the Kolis as these coastal forests have been providing them with a living and protecting their communities from inland water intrusion. Thus the Kolis have been said to be a unique community worshipping the natural forces of the environment and performing rituals as they depend completely on them. The value of these natural landscapes is cultural and spiritual in one sense. Kolis are artisanal fishers and are known for their unique and sustainable techniques of fishing. They have developed a sense of ecology and knowledge of their own by living in this habitat over centuries and passed it on from generations for fishing. Now urbanization, pollution, and development in the sea are unmaking these relations, failing the Kolis in determining the appropriate conditions for fishing. The livelihood of these fishermen is in jeopardy and the identity of this indigenous community is being threatened as the upcoming generations are slowly fading away from the fishing industry as their main occupation.

The Mangrove ecosystem provides a rich breeding grounds for marine life and they have an unbreakable bond with the Kolis as these coastal forests have been providing them with a living and protecting their communities from inland water intrusion. Thus the Kolis have been said to be a unique community worshipping the natural forces of the environment and performing rituals as they depend completely on them. The value of these natural landscapes is cultural and spiritual in one sense. Kolis are artisanal fishers and are known for their unique and sustainable techniques of fishing. They have developed a sense of ecology and knowledge of their own by living in this habitat over centuries and passed it on from generations for fishing. Now urbanization, pollution, and development in the sea are unmaking these relations, failing the Kolis in determining the appropriate conditions for fishing. The livelihood of these fishermen is in jeopardy and the identity of this indigenous community is being threatened as the upcoming generations are slowly fading away from the fishing industry as their main occupation.

The Antagonists: Government authorities, builders, policymakers Mangroves as an ecosystem have been a part of the history and culture of the city and hold immense ecological values to it, but the acknowledgement that they are worthy of has always been lacking from the authoritative bodies. They have been destroying the of 2005

followed by the 2017 floods. The land reclamation and construction of coastal roads on these ecosystems while blocking the drains added pressure on the existing inefficient drainage system, as (Gandy, 2008) describes the city as a hydrological dystopia. The effects of the existing mangrove swamps on the city’s infrastructure were taken into consideration when building the current stormwater drainage system in the middle of the nineteenth century. As a result, the established drainage system was never intended to handle the strain added by the land reclamation that led to their large diminution (Narwade, 2016). Mumbai’s mangrove swamps function as a piece of infrastructure, much as the stormwater drains that humans have constructed, so they must be preserved and treated with respect.

The Costal Regulations in the country were devised post1972 conference in Stockholm on Human Environment. Under the Environment Protection Act the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) 1991 was made to protect the coastal landscapes and the security of the local indigenous fishing communities. (Parthasarathy, 2016) This law existed even before the floods hit Mumbai and yet it was violated. The cause of the floods apart from the sewage system was the land reclamation and the construction of the commercial district of Bandra Kurla Complex (BKC) by destroying mangroves along the Mithi creek.

The CRZ law states the protection of the land, from the high tide line to up to 500 m inwards and the protection of the social and economic aspects of communities that depend on it. Out of the four CRZ zones mangroves fall under CRZ- I termed ecologically sensitive areas. The drawback of the regulations was that to check for violations, there was no clear-cut monitoring system or enforcement system. It was not done well to map violations, encroachment, pollution, and distinct zones. The main goals of the CRZ Notification were compromised by the more than 25 regulation revisions made over twenty years. 2011 saw amendments in the CRZ regulations and the objectives focused on the sustenance of the livelihood of the fisherfolks and protecting the ecology along the coast and termed the CRZ-I a ‘no-development zone’ (Parthasarathy, 2016). Regardless of these amendments the encroachments, violations and development have not stopped. The Essel World Amusement Park in Gorai, Mumbai destroyed 700 acres of mangroves and is estimated to have affected the livelihood of 500 Koli villages. The Thermal Power plant at Dahanu, Mumbai for its construction reclaimed about 1000 acres of wetlands directly affecting the marine ecology leaving more than 1000 Kolis threatened with loss of livelihood. (Patil, 2001).

In light of these massive encroachments and violations, fishermen

are deeply concerned about how protective environmental laws, such as those pertaining to CRZ, are being undermined, with disastrous consequences for their lives, livelihoods, and dependent ecosystems. “This model of development does not benefit the fishermen in any way but creates uncertainties for their survival and livelihood. Community rights over water bodies should be entrusted to local fisher folk for the protection of the coastal ecosystem and management of fish resources.” said one of their leaders (Patil, 2001).

The Climate Action Plan Mumbai

Valuing a landscape doesn’t mean protecting and conserving it in isolation. It is about letting the landscape be in its natural form. The value of landscape to the local community is the force that has been driving them to fight for and protect these ecological landscapes while on the contrary, the concerned authorities in the recently Mumbai Climate Action Plan 2022 (MCAP) swiftly leave out this landscape infrastructure which is vital in flood mitigation and complementary to the drainage system of the city. The Climate Action Plan is a positive response that finally, the authorities recognise the intensity of the climate crisis but how efficient is this response. (Hussain Indorewala, 2022)

The vision of the MCAP is a Climate Resilient Mumbai and a Netzero city and identifies six essential sectors one of which is Urban greening and the action track states:

1)Increase vegetation cover and permeable surface.

2)Restore and enhance the biodiversity in the city. (BMC, March 2022)

Both these agendas focus on increasing the green cover for resilience to floods and improving air quality by application of scientific knowledge to grow more trees. It lacks recognition and focuses on the most valuable ecological assets of the city instead it proposes displacing the ‘encroachments ‘(slum settlements), to build parks and restore permeable lands and natural drains. This affects the low-income communities and threatens their livelihood. The MCAP doesn’t take into account the impact of the current infrastructural project in construction or sanctioned. The Intergovernmental Panel on climate change report, particularly calls out Mumbai terming the new coastal road project as maladaptive in the long run to the city and also talks about the damage to be caused to the ecology and the livelihoods of the fishermen. The report goes on to state that the MCAP has no vision in the action plan and won’t be sustainable for the city’s survival against the rising sea levels and climate change.

(IPCC, 2022)

The second sector in the MCAP that disregards the mangroves is Urban flooding and Water Resource Management and the action track states:

1) Building flood resilient systems and infrastructure.

2) Reducing Pollution and restoring aquatic ecosystems (BMC, March 2022)

The report aims at investing in a new stormwater system to prevent flooding, widening rivers and creeks like Mithi and others as well. The municipal bodies are ready to shell out their pockets on new technology with plans to utilise artificial intelligence and invest in the research and development of something completely new. This is what explains the paradox of the value- of diamonds and water, where the mangrove infrastructure and the natural barriers with immediate effect haven’t been considered at all but new technologies that require an investment of Rs 7500 crore (75 million pounds) all in just one financial year (Iyer, 2022) are the focus of this report and that explains their value towards these landscapes. Mangrove ecosystem apart from the resilience towards climate will bring socio-economic stability as well. The authorities haven’t acknowledged and taken into consideration the informal settlements of the city and their vulnerability to the rising water.

The MCAP focuses on flooding in the report, but it fails to take into account that the situation throughout the city isn’t the same and the reclaimed lands are at higher risk to be impacted by 2050. (Iyer, 2022).

Mangrove ecosystems are an example of the importance of the value of landscape socially, ecologically and economically. The lost and disregarded landscapes of the city are brought into the limelight due to the original inhabitants of the city and their interdependency on these landscapes, their value toward these mangroves somewhere brought this argument of protecting these landscapes in the first place. The MCAP needs to be challenged by landscape practitioners and ecologists to devise strategies with the involvement of the communities as this is the major drawback of the report. Thus the next chapter will focus on the community of landscape architects, environmentalists and ecologists as catalysts between the two actors in the story of mangroves and be a voice to showcase the value of the landscape ecosystem in making the city viable.

Infrastructural development continues at the cost of nature and livelihood of the poor

The interdependency is what makes the sense of value stronger

Source:

(https://mangroveactionproject.org/mangrovephotographyawards/)

Figure 11: The mangroves of Navi Mumbai that protected the community from direct impact of the flood.

Source: Pratik Chorge

Figure 11: The mangroves of Navi Mumbai that protected the community from direct impact of the flood.

Source: Pratik Chorge

Role of Mumbaikars (residents)

As Landscape Architects, we can visualize change. Thus we can be the catalysts to bridge the gap between the local community and the government bodies to bring a significant change and impact. Mangroves are delicate yet important ecosystems, but only 50% of the people living in Mumbai, Thane and Navi-Mumbai are aware of these fragile ecosystems and only 30% of them understand their value towards climate resilience. (Godrej, 2021). Thus the first and the right kind of value response is awareness. The residents of the city need to be aware of the silent warriors of the coast and their value and not just that but for any large-scale impact, it is essential to have extensive public outreach. Awareness and government policies are directly proportional, and the inclusion of people in decision-making is the right way forward to avoid the mistakes made in the past while devising the CRZ rules and the MCAP. Awareness through education, nature trails, and art initiatives are examples to name a few. The key is to create allies and Landscape architects can partner with various stakeholders from NGOs, academia, corporates and ecologists. These allies together are the catalysts needed to be involved for a systemic approach in sustainably managing mangrove ecosystems.

Role of Corporates

Awareness is the first foot forward in, along with this research studies can be promoted to encourage people to study and write about these valuable ecosystems as in literature not much has yet been explored about the mangroves of Mumbai. Involving corporates and their employees by designing initiatives can help in the protection and conservation of the mangroves. Godrej and Apple have begun their contributions in Mumbai and similar collaborations with many other corporates can help us in multiplying the impact. Godrej plays a significant role in mangrove conservation as the land acquired by them in 1948 for setting up an industrial township consisted of mangrove ecosystems which they retained and began conservation initiatives to contain its rich biodiversity. (Godrej group, n.d.) The only part of mangroves in Mumbai that is protected under the law and certified. At the same time, Apple awarded a grant to the Applied Environmental Research Foundation (AERF) in 2021 to research alternatives to protect the mangroves in Mumbai and develop strategies for local communities to establish sustainable industries that benefit from the biodiversity. Conservation agreements will give village members longterm support in exchange for land conservation and transforming the local economy to one that is dependent on maintaining the

mangroves intact and healthy (Apple, 2022).

Other strategies along with the above-mentioned are acquiring legal protection, which is a part of the CRZ regulations but preventing violation of this is essential, conservation initiatives can be incentivised for more people to be involved and the most important one would be valuing ecosystem benefits, we will look further into this aspect in the following chapter. All these initiatives are vital for the emergence of the situation the city will be facing.

Economic Valuation

Vandana Shiva, an Indian scholar and environmental activist repeatedly point out that change in the social system, which gives importance to social profitability, and ecological sustainability is the only solution in the long run. The community of landscape practitioners can help in adding value or sustenance to these ecosystems by laying out probable options to work with the local communities and the policymakers to construct a holistic approach. A coherent approach is essential that gives importance to economic and ecological values.

In the first chapter we looked at how ecologists and economists are at loggerheads about their approach to putting a value to ecosystems. Still, I argue that we use the valuation of ecosystems not for quantification and adding a monetary compensation but as a tool to expose the value of these ecosystems that have been overlooked while making policies and this can aid in sustainable decision-making which would benefit both the local communities and the government body. Attempts have been made to evaluate the mangrove ecosystems of Mumbai but only the direct benefits have been calculated. As landscape practitioners, it is vital to unmask all the benefits Mangrove ecosystems provide by evaluating the non-monetized benefits of ecosystem services because overlooking them will make it difficult to put forward new conservation or protection laws essential while advocating a coherent approach. A direct approach and factors need to be laid down to carry out the valuation study.

The landscape of mangroves does not thrive in isolation but exists along with multiple habitats, terrestrial, aquatic and multiple migratory birds are linked to the mudflats. Thus it is essential to consider the value provided by the interdependent habitats. When non-monetized benefits and habitat value are considered, the total value of Mumbai’s mangroves is likely to be an order of magnitude, more than the total of the six partially monetized services. (Everard, 2014)

An economic valuation can be convincing. In Fiji, it was reported that the single most compelling piece of evidence in convincing the

minister responsible for land development to cease large-scale mangrove reclamation in 1983 was the economic valuation of mangrove ecosystems. (Lal, 2003)

Additional to the economic valuation to realise the societal value of mangroves in urban situations, particularly in Mumbai can be carried out through the development of non-destructive ecotourism and educational potential, including a broader public understanding of the benefits that they bring. This will help in adding development pressures to the values associated with diverse ecosystem services that should be recognised and emphasised by city planning authorities. The translation of these values into policies can help justify current protective policy measures, as well as encourage and lead more successful conservation projects that preserve and promote mangrove systems as vital natural infrastructure. (Everard, 2014). Mangrove protection and value realisation over the broad geographic range in which such systems exist would benefit from investment in research to examine how these systems function, interact with adjacent ecosystems and serve a variety of functions. The value of the commodities and services that mangrove systems provide should also be expressed since this will inform the best long-term management strategies for the welfare of all societal members.

For the Kolis and local communities

The MCAP and the CRZ rules both should be taken into consideration, as one of them failed to acknowledge the value of mangroves whilst the other states a few restrictions for conservation but non of these policies and plans address or initiate community involvement. The rule was reinforced with the purpose of safeguarding the mangroves, but the lack of public awareness and participation weakened the conservation laws. It is necessary to address this, particularly in metropolitan areas. We must implement less restrictive and more participative rules if we want urban mangrove ecosystems to flourish. A holistic approach toward these landscapes is essential and a more interactive outlook rather than prohibitive. As (Shiva, 22) states that the world was full of indigenous communities and they co-existed for all these years without causing any destruction to the landscapes, similarly involving the local inhabitants of the fisherfolk community. The integration of the indigenous fishermen and the landscape will add to the economic social and ecological value.

Landscapes are both naturally occurring and culturally constructed. Indigenous societies have co-evolved with their natural habitats all across the world. The Aborigines of Australia shaped the current

Australian terrain by tending to the continent’s landscape while they conducted seasonal trips across the land mass. Similarly, many communities inhabit and produce diverse landscapes in India. We acknowledge this human contribution to the landscape and should encourage the integration of mangroves into our economic systems in ways that use and manage them sustainably, rather than protecting them by keeping humans out. An integrative approach to mangroves, as opposed to the traditional conservation method, could secure Mumbai’s sustainable future.

Mangroves ought to be considered a part of Mumbai’s infrastructure. In addition to providing the Kolis with a fertile fish breeding ground, mangroves provide a variety of other benefits that can help numerous other industries in these informal settlements. Mangroves frequently have rapid growth and offer ready access to wood, leaves, fruit, and roots. Because wood is rot and termite-resistant and can withstand salt water, it is also a good building material and might be the best choice for making these settlements weather and water-proof. Kolis may use it as a sustainable supply for activities related to fishing, such as building docks and traps, water tightening fishing lines, and curing nets. Mangrove wood is an excellent fuel for wood or charcoal because it is highly dense and produces a lot of heat when burned. It might serve as the ceramic kiln’s backup energy supply. Currently, synthetic textile waste is considerably more harmful pollution than fuelwood is used to fuel the kilns. The leather business by the locals uses natural dyes made from the bark of several mangrove species to colour textiles and leather goods.

Mangroves defend coasts from flooding, storm surges, and erosion, all of which are becoming increasingly common as the world’s climate changes. As a result, they are an asset that safeguards the city’s infrastructure and even property prices. Another application for mangroves could be wastewater treatment for the communities that surround them. Mangroves may filter heavy metals and other contaminants without suffering significant development damage. Mangroves perform a wide range of functions that can aid in their integration with local urban economies. We can establish social, cultural, economic, and ecological ties between people and mangroves by supporting the responsible use of mangroves at both the neighbourhood and city scales, thereby encouraging the care of urban mangrove forests. Innovation in how humans perceive and engage with natural ecosystems will be critical in designing cities where a variety of primary, secondary, and tertiary human activities may coexist with nature rather than compete with it.

The value of landscapes is never questioned but there is turmoil on how to portray these values, thus the gap between the approach of environmentalists and economists. The conflict between the two puts the landscape and interdependent local communities into dismay against the authoritative bodies. This paper intends to try and understand the value of landscapes from both economical and ecological perspectives and answer the question of What is value? This was an attempt to understand the value of mangroves to a city like Mumbai at risk of sinking. But my research and study helped me understand that there is still a long way ahead for the mangrove valuation literature to come to a point where the estimates will comprise all categories of benefits provided by mangroves, including cultural, spiritual and aesthetic. But till then the steps that can be taken and what can we give back as a community of landscape architects.

This paper is a step towards bringing forward the value of mangroves to the city and especially to the indigenous fishing community. The mangroves and the livelihoods of these people both are struggling to exist due to their interdependency and as landscape practitioners the pathway is to adapt to a systemic holistic change, mapping the livelihood and its impact along with the value system will help in their sustenance. The mangroves and the Kolis both are the original inhabitants of the city and they need to be protected at all costs.

Mangroves are a unique ecosystem, the intangible benefits of these landscapes do not get calculated thus leaving them ignored. Just like in the Paradox of value, water is priced cheaper and diamonds are at higher prices. We fail to understand what holds more value and is essential for our living. The paradox of Value is a way to look at landscapes and their impact on different stakeholders.

Figure 4: Mangroves as seen Source: Darshana Patil

Figure 4: Mangroves as seen Source: Darshana Patil

from the Navi mumbai creek Patil (Author’s mother)

Books and Journals

Anand, N. (2017). Hydraulic City: Water and the Infrastructures of Citizenship in Mumbai. Duke University Press.

Apple. (2022, April 21). Retrieved from Apple newsroom: https:// www.apple.com/uk/newsroom/2022/04/conserving-mangroves-to-protect-local-livelihoods-and-the-planet/

BMC. (March 2022). Mumbai Climate Action Plan. Mumbai.

Bo Yang, S. L. (2016). Design with Nature: Ian McHarg’s ecological wisdom as actionable and practical knowledge. Landscape and Urban Planning, Pages 21-32.

Eisenman, T. S. (2013). Frederick Law Olmsted, Green Infrastructure, and the Evolving City. Journal of Planning History, 287–311. Everard, M. J. (2014). The benefits of bringing mangrove systems to Mumbai.

Gandy, M. (2008). Landscapes of Disaster. In M. Gandy, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. (pp. 108-130).

Gibbons, J. (2021). Sustaining Life is a Prerequisite of Design Excellence. In C. Ivers, 250 Things a Landscape Architect should know (p. 78). Birkhäuser.

Godrej group. (n.d.). Retrieved from Godrej Mangroves: https:// mangroves.godrej.com/index.html

Godrej, D. P. (2021, August 6). International Mangrove Conservation Day. (G. a. Boyce, Interviewer)

Hans Nicolai Adam, S. M. (2022). Climate change and uncertainty in India’s maximum city, Mumbai. In H. N. Lyla Mehta, The Politics of Climate change and uncertainty in India (pp. 135-157). Routledge.

Hussain Indorewala, S. W. (2022, April 1). The dangerous optimism of Mumbai’s climate action plan. Retrieved from Scroll: https://scroll. in/article/1020471/the-dangerous-optimism-of-mumbais-climate-action-plan

IPCC. (2022). Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge University Press.

Iyer, K. (2022). Sinking Mumbai: Have we woken up to the climate crisis and rising sea level? Question of Cities.

Lal, P. (2003). Economic valuation of mangroves and decision-making in the Pacific. Ocean & Coastal Management.

Linn, E. (2012). Re-Spect. Balboa Press AU.

Narwade, S. (2016). Mumbai Floods, Reasons and Solutions. . International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 6, Issue 3.

Norton, B. G. (2012). Valuing Ecosystems. Nature Education Knowledge.

Parthasarathy, D. (2016). Urban development, environmental vulnerability and CRZ violations in India: impacts on fishing communities and sustainability implications. Environ Dev Sustain.

Parthasarthy, D. (2011). Hunters, Gatherers and Foragers in a Metropolis: Commonising the Private and Public in Mumbai. Economic and Political Weekly.

Patil, R. (2001). Coastal Zone Conflicts in Maharashtra. In K. Kumar, Forging Unity: Coastal Communities and the Indian Ocean’s Future (p. 156). Chennai: International Collective in Support of Fishworkers.

Shiva, V. (22, Jan 10). How to decolonize the global economy. (G. L. Forum, Interviewer)

Thompson, I. H. (2000). Ecology, Community and Delight. University Press Cambridge.