A TALE OF TWO POOLS

A story of governmental and societal attitudes towards social and economic value told through the Nine Elms Baths (1901-1970) and the Skypool (2021-2029).

The Nine Elms Baths (1901-1970) were built in a time and place of extreme crisis. Among a heavily industrialised environment, the working population had no access to washing facilities and battled daily to escape the soot which plastered itself over every surface. The baths provided an essential function to the surrounding community, allowing them to wash their clothes and bodies, and enjoy the activity of swimming. In addition to this, the space was used for social events such as boxing matches and political rallies, leading to a space which fostered community and facilitated social reform. A few hundred metres from this site is the newly built Skypool which is suspended 10 storeys up between two towers of the Embassy Gardens luxury development. It is exclusively accessible to high paying owners of the multi-million pound apartments which are completely empty, bought as safety deposit boxes for outside investors. These two bodies of water on the same site provide two polarising examples of governmental attitudes towards social and economic value. In a new era of crisis, when over 1 million households are waiting for social homes, high end luxury developments are the priority, placing economic gain for the wealthy above the needs of people. This illustrates a clear change in the perception of value and the function of residential and social spaces, from a social need to a capital investment.

The image of the British public swimming pool is synonymous with nostalgia for a previous golden age of leisure. The perception of lidos and leisure centres across the country are still viewed through a tainted John Hinde1 lens which portrays the swimming pool as a fabled equitable social hub which did not escape the 1970s. The swimming pool today is seen through two very different lenses which use its symbol as a demonstration of loss or as a symbol of wealth. Elmgreen and Dragset2 use the swimming pool motif in much of their work as a metaphor for depression, loss and death, while swimming pools are squeezed into London townhouse basements as a way of adding to their investment value. This essay tracks the provision, use and value of swimming pools in correlation to governmental policy and social equity through three time periods, focussing on Nine Elms as the site of investigation. It tells the story of two swimming pools: the Nine Elms Baths (1901-1970) and the Skypool (2021-2029) across past, present and future, as a way of symbolising governmental policy towards social and economic value, leading to the mass privatisation of social and housing infrastructure, and its eventual downfall.

This essay is intentionally biassed, playing into the nostalgic imagery of the swimming pool and glazing over its negative historical connections to class, gender and racial exclusion in order to exaggerate the social and economic disparity and act as a protest against the complete privatisation of social spaces.

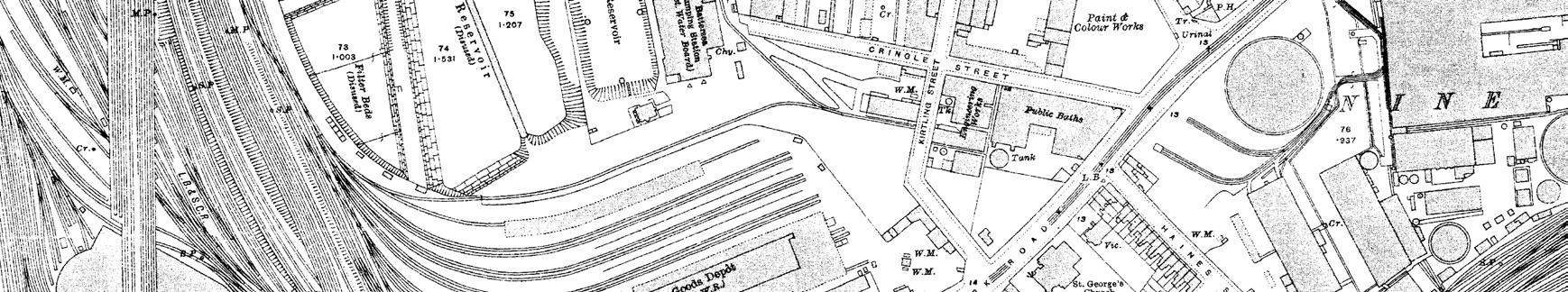

Battersea and Nine Elms, located on the southern bank of the Thames have long been sites of oppression, used by the upper class of London as a dumping ground for agricultural and industrial industries. The area began as marshland, it was described by Ramsey as “a despised oasis, flanked with a few ramshackle huts, inhabited by a class of people who made day hideous and night dangerous, for it was not safe for decent people to pass the dismal swamp after dark, as highwaymen and footpads infested the roads”3. From the 17th century, Battersea became the site of a growing number of industries thanks to its placement close to central London and its connection to the river which was used as the predominant transport method for heavy goods. The arrival of the railways in 1830 sparked growth of heavy industry and the area quickly became synonymous with factories and workshops producing cement, chemicals, candles, flour, oil, paint, turpentine, sugar, starch, soap and vinegar. Larger service industries such as building, engineering, water, gas and electricity also became increasingly prominent along the riverbank. These industries engulfed the small village that was once there, transforming the landscape into a compact cluster of chimneys, spires, cranes and factory roofs towering over tightly packed Victorian housing which housed the low income workers. William Connor, Battersea’s Medical Officer wrote in 1866, “Battersea is very peculiarly circumstanced; first, in having become a very large manufacturing district, and, secondly, in having a labouring population daily and hourly enlarging… to an extent that would hardly be credited”.4 This labouring population lived in close proximity to the heavily polluting and noxious industries which left black soot plastered over every surface, without laundry facilities in their homes. The local sanitary inspector in 1896 claimed to have visited every house in the district, stating that there was only one house with a bath in the whole ward.5 He also stressed that swimming baths were urgently needed after several drownings in the river reservoirs.

3 Sherwood Ramsey, Historic Battersea Topographical Biographical, 1913. 4 Wandsworth District Board of Works, Sanitary Department Report for 1866, 1866, p. 29.

5 Colin, Thom, and Andrew Saint, Survey of London: Battersea, L (Yale Books, 2013), XLIX.

In 1844, the Committee for Promoting the Establishment of Baths and Wash-Houses for the Labouring Classes was formed which petitioned for a bill for the regulation of public baths. In 1846 the bill was introduced which became the 1846 Public Baths and Washhouses Act. This was the first legislation to empower British local authorities to fund the building of public baths and wash houses.

‘WHEREAS it is desirable for the Health, Comfort, and Welfare of the Inhabitants of Towns and populous Districts to encourage the Establishment therein of public Baths and Wash-houses and open Bathing Places:’6

The proposal for a new baths at Nine Elms was approved by the Vestry in 1895 and a site was purchased from the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company on the corner of Battersea Park Road and Cringle Street using funds provided by the government through the Public baths and Washhouses Act. A competition was run in 1897 for the design of the baths with, at the Library Committee’s request, a reading room and the 15 entries, none of which were greatly received by the press; “none have much pretension to be called Architecture”7 , were judged by the Vestry’s surveyor. The winning design was by Francis J. Smith who was from Battersea. It was described as being “in the Renaissance style of architecture, plainly treated, of stock brick with red-brick facings and Portland-stone dressings to the numerous mullioned windows.”8 At the centre of the plan was the 150ft by 50ft swimming bath, arranged parallel to Cringle Street. This was the largest covered swimming bath at the time it was built and was also used to host public entertainment in the Winter; with the bath covered over and the galleries which surrounded it at first floor level full, the building could host up to 1,500 people. At the awkward angled corner of the plot was placed the reading room, originally designed to follow the angle of the roads, it was later changed following the press criticism to a semi-circular bay, apparently taken from one of the unsuccessful competition entries. To the West were the women’s slipper baths and separate entrances for men and women. At first floor level was the superintendent’s

6 Baths and Washhouses Act, 1846.

7 ‘Builders’ Journal and Architectural Record’, 1898, p. 485.

8 ‘Contract Journal’, 1906, p. 1139.

Nine

flat, rooms for the baths and washhouses commissioners and the establishment laundry. The men’s slipper baths were placed behind the swimming bath along with 53 public washhouse compartments. Additional entrances opened onto Cringle Street which led to two ‘artistes’ rooms’, a waiting room and, unusually, a creche which were connected by a corridor which was praised as being wide enough for the “perambulators in which the linen is generally brought”9. Construction began on the 9th of September 1899, with the foundation stone laid by Battersea MP John Burns who expressed the proud statement ‘Built by Direct Employment’. The design of the building was altered many times during its construction in order to accommodate a changing brief, adding a clubroom and ladies’ room which, along with the difficult structural problems of achieving such large spans, led to the final building costing £45,000 - almost double the figure originally proposed. These spans were achieved through iron and steel circular trusses and stanchions which were visible internally. The floors were wooden block, with teak being used for the diving boards and steps into the pool. Two artesian wells supplied water to the facility which was steam heated and lit with electrical lighting.

The baths opened in 1901 and quickly became an important part of the community as a sanitation and leisure facility, as well as a place for community gatherings, boxing matches and radical political meetings, leading to its nickname ‘The People’s Hall’. London’s first black mayor, John Archer was from the area and a member of the swimming club; a powerful example of the impact that the baths had on its surrounding community in an age of crisis.

By the 1930s, structural defects began to threaten the building. The first floor galleries were closed and eventually demolished in 1956. By 1970 the entire building was closed and subsequently demolished in the following year.

9 ‘Builders’ Journal and Architectural Record’, p. 485.

Most public baths and washhouses from this era have fallen derelict - ruined by cut funds as a result of policy changes, cheaper flights abroad, a trend towards privatisation and a change in the social function of the swimming pool. The internet is inundated with images of historical pools either abandoned, demolished or converted into offices and apartments. Paul Talling runs a website titled Derelict London10 which explores through walking tours, photographs, personal stories and blog posts how many of these buildings have been changed or lost. This mass exodus of pools has coincided with the mass privatisation of Britain’s housing and infrastructure following the measures introduced by the Thatcher government such as the Right-to-Buy scheme which aimed to shift the majority of the UK’s housing stock from publicly to privately owned in order to encourage a free market economy and swing voters from left to right. With more of the population owning their own homes, they would be more inclined to favour the Conservative policies away from public spending and towards private ownership.

These policies coincided with a boom in mass image-based media production through photography and television, an industry dominated by the United States of America under the leadership of former actor Ronald Reagan. Billboards, magazines and TVs were dominated by images of the ‘American Dream’ depicting smiling, young, white families who had earned their own house and all the modern conveniences that came with it through Capitalism and the free market economy. These images were created during an intense period of the Cold War as Capitalist propaganda in the fight against Communism and were vehemently supported by the UK government. Much of this imagery was aspirational, inspiring a desire among the public to attain the lives depicted and the swimming pool was a key element in this strategy, shifting the function of the pool from a leisure facility to a symbolic display of wealth, the value of the pool from social and health to economic investment, and the ownership of the pool from public communal infrastructure to private residential object. The photography of Slim

10 Paul Talling, ‘Derelict London Pools and Baths’, Derelict London <https:// www.derelictlondon.com/derelict-london-pools-and-baths.html> [accessed 2 January 2023].

Aarons provides an excellent example of this change in perception, framing scenes of luxury, opulence and extravagance arranged around a pristine rectangle of unperturbed blue. Poolside Gossip11 depicts a scene by the pool of the iconic Richard Neutra-designed Kaufmann House in Palm Springs. The photograph encapsulates this propaganda of the modern America, where impeccably dressed women can recline by the poolside, sipping champagne and gossipping about their husbands who have bought their elegantly designed modernist house through the honest spirit of Capitalism, showing off their swimming pool without actually swimming in it.

This shift in value and perception eagerly spread from Palm Springs to the United Kingdom, despite the stark differences in weather conditions, and combined with the governmental policies and cheaper package holidays abroad, forced the mass closure of many public pools, a movement which has not ceased. A property article in 200912 estimated that there were 210,000 private pools in the UK, with an annual increase of 2,500 and Swim England’s 2021 report A Decade of Decline13 estimated a 40% decrease in the number of public swimming pools by 2030.

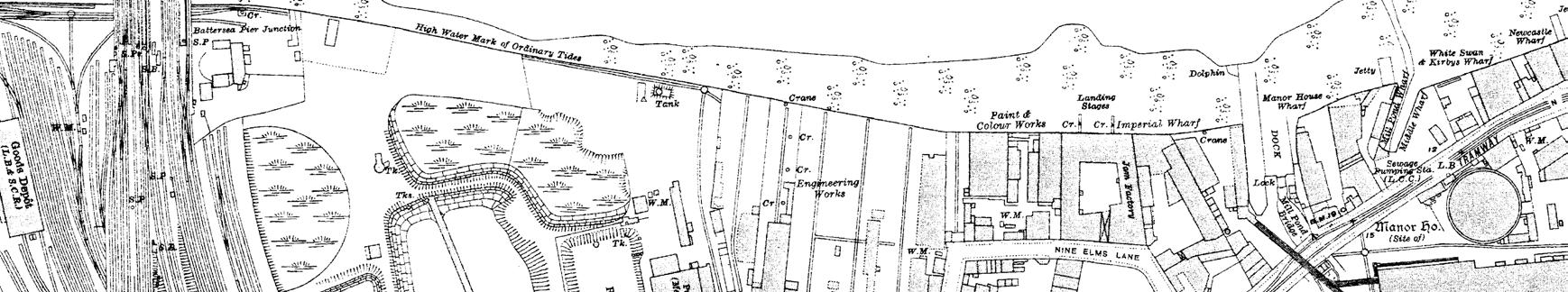

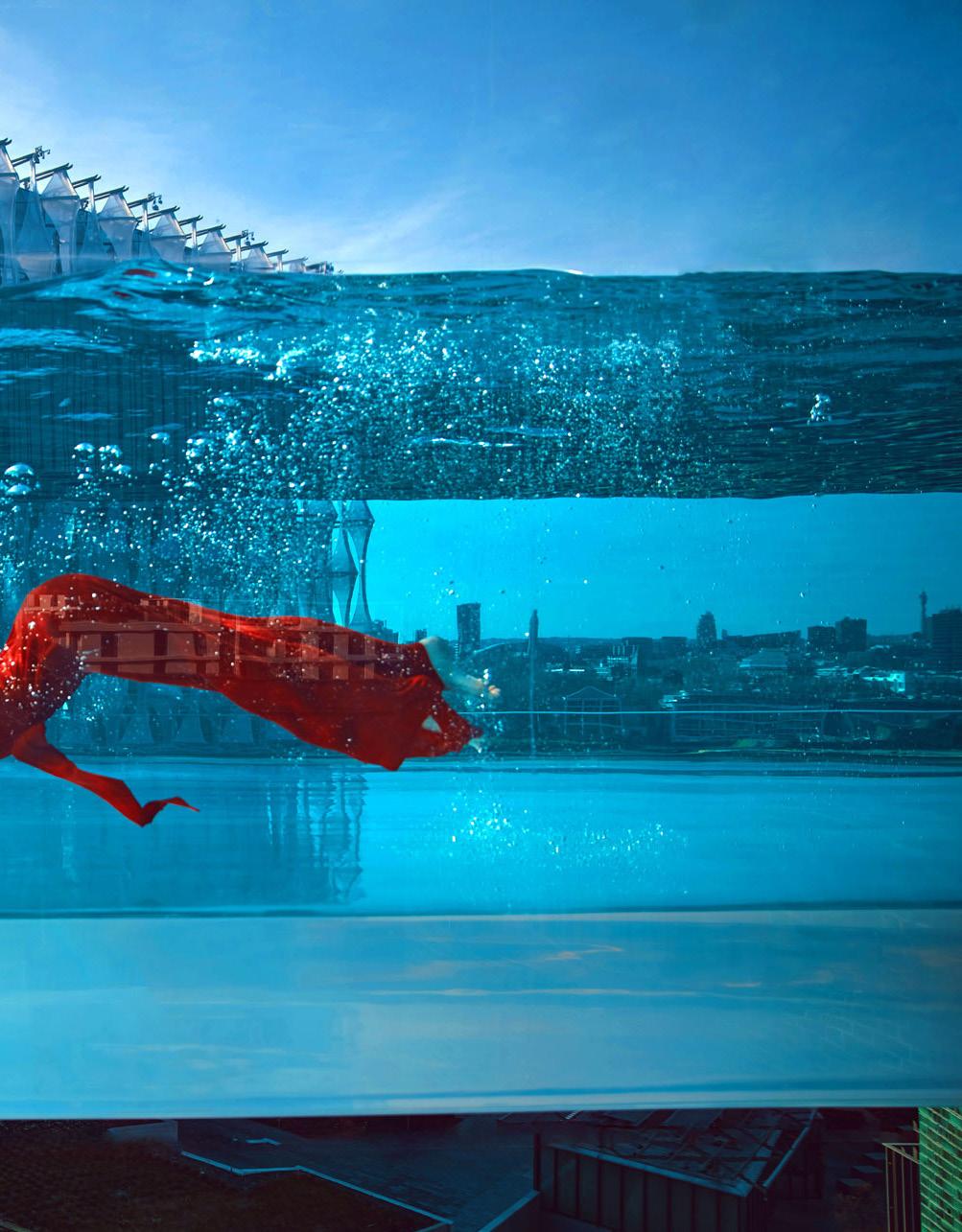

A few hundred metres from the former site of the Nine Elms Baths sits the epitome of this shift towards privatisation - the Skypool, nestled in the largest regeneration project in Europe as part of the Vauxhall, Nine Elms and Battersea “Opportunity Area” - a jungle of high-rise, multi-million pound flats privately owned and largely uninhabited. The clear pool sits 35m above ground spanning the 15m gap between two towers of Ballymore’s Embassy Gardens development, looking directly out at the US Embassy’s shiny ETFE panels. It is constructed in clear acrylic, the side walls having a thickness of 180mm and 3.2m depth. Its base is 360mm of solid acrylic supporting the pool’s own weight of 50 tonnes and 150

11 Slim Aarons, Poolside Gossip, 1970.

12 Colin Coates, ‘Why You Don’t Need to Be Swimming in Cash to Install a Pool at Home’, Mail Online, 2009 <https://www.dailymail.co.uk/property/ article-1197150/Why-dont-need-swimming-cash-install-pool-home.html> [accessed 14 March 2023].

13 Swim England, A Decade of Decline: The Future of Swimming Pools in England, 2021.

tonnes of water. The height of the pool and its consequent swaying from wind means that the two ends are placed on movable bearings in order to adjust and adapt to these shifts. The engineers, Eckersley O’Callaghan describe the project as “The first of its kind and a truly remarkable feat of engineering”14. The pool was opened in May 2021 with a barrage of social media advertisement, infiltrating our devices and stirring up a frenzy of excitement as we eagerly watched in amazement as well-dressed young men and women with perfectly toned abs elegantly glided through the floating box of crystal blue water. This excitement was swiftly cut short, however, when it became apparent that the pool was exclusively available to residents of the multi-million pound apartments. Although privately accessible, it is highly publicly visible from the ground below it - a very different viewpoint to the drone shots published on its opening. Staring up at this almost invisible box feels extremely underwhelming. Rather than the advertised oasis filled with athletic swimmers, it is mostly empty, with the occasional figure spotted performing an awkward doggy paddle. The story is the same for the whole development, where apartments are completely vacant, designed to the minimum space requirements in order to act as safety deposit boxes for foreign investors. The new housing stock does not function as homes for the community to live in, but economic investments for outside buyers to be left uninhabited, and this is the case for the whole of the Vauxhall, Nine Elms and Battersea ‘Opportunity Area’ where tens of thousands of these apartments have been built but unused. This question of function and value of housing is echoed from that of the swimming pool, where it is now seen as a status symbol, a display of economic wealth which tantalises the local community who have been violently displaced in order to construct it.

The UK is in a housing crisis, with one in three adults affected by it. A desperate need for housing and particularly ‘affordable housing’ is widely documented and accepted. The 2017 UK Housing Review Briefing Paper15 argued that while supply is of critical importance, “so

14 Eckersley O’Callaghan Engineers, ‘Sky Pool’, Eckersley O’Callaghan <https://www.eocengineers.com/projects/sky-pool-246/> [accessed 15 March 2023].

15 Steve Wilcox and others, 2017 UK Housing Review (Heriot Watt University, 2017).

is the rather more neglected issue of affordability, in both the private and social housing sectors.” In the foreword to the June 2017 IPPR report, What more can be done to build the homes we need?16 Sir Michael Lyons said: “We would stress that it is not just the number built but also the balance of tenures and affordability which need to be thought through for an effective housing strategy.” This is echoed in research commissioned by the National Housing Federation and Crisis from Heriot-Watt University17, which identified a need for 340,000 homes each year to 2031 of which 145,000 “must be affordable homes”.

This desperate need for housing is not portrayed in the development of Nine Elms, with only 18% of new housing in the area classed as affordable, against the lawfully required 40%. This is greater exacerbated by the definition of ‘affordable’ as 80% of market value which is still unattainable for the majority of the population. Many of the affordable housing blocks of the Nine Elms developments are shared ownership flats which means that the residents can own a quarter of the property and pay rent to the developer on the rest. A large number of these are situated on the site of Embassy Gardens, stuffed behind the penthouse apartments, against the railway line, hidden from sight behind a veneer of luxury. The roads are littered with construction debris, flanked by harsh orange barriers and barbed wire fences. Lamborghinis line the curbs, pasted with parking tickets, unapologetically stealing the space of the families who occupy the substandard accommodation. The sound of rushing trains overhead interrupts the groaning of surrounding construction sites, penetrating the plastic-clad walls. The flats are accessed through colloquially named ‘poor doors’; hidden entrances, obscured from public view out of embarrassment which lead to dark, long corridors, unfurnished and identical. These apartment blocks have been constructed to the bare minimum standards lawfully required, packing as many units as possible into the cramped space, with reports of leaks, disconnected pipes, exposed wires and broken

16 Michael Lyons and others, What More Can Be Done to Build the Homes We Need? (Institute for Public Policy Research, June 2017).

17 People in Housing Need (London: National Housing Federation, 15 September 2020).

Nine Elms, 2023

windows posted all over Instagram and Trustpilot pages such as @ ballymorehell18 and @real_embassygardens19. The scathing testimonies tell a story of a group of people - the only real inhabitants of the developments, who have been exploited and oppressed by a “predatory company”, using them as a “cash cow so that they could continually squeeze you for life”20

It seems unbelievable that these companies can get away with this, but it is thanks to specific government policies and decisions which have allowed these conditions to exist. The idea for these ‘Opportunity Areas’ was first proposed by Ken Livingstone, the socialist mayor of London in the 2004 London Plan, who envisioned Nine Elms, along with King’s Cross, Elephant and Castle and Paddington as areas for investment which would encourage tall buildings in the hope that large amounts of funding could be used for the public good. It was proposed that half of the housing would be affordable and developers would have to provide a financial viability statement if this figure was not possible. Fast-forward to 2012 when the plans for the area were being drawn up and the Conservative led coalition government was in power, with Boris Johnson as London Mayor. A series of policy changes in planning laws changed the definition of ‘affordable’ to 80% of market value and put financial viability at the centre of planning policy, prioritising profit over all else. This allowed financial viability statements to become a ‘get-out’ clause for every developer, incentivising them to reduce the amount of affordable housing in favour of increased capital gain. Nine Elms was used as the primary testing ground for this new housing economy of financial deregulation - a developer free-for-all.

18 ‘Ballymore Hell (@ballymorehell)’ <https://www.instagram.com/ ballymorehell/> [accessed 15 March 2023].

19 ‘The Real Embassy Gardens (@real_embassygardens) • Instagram Photos and Videos’ <https://www.instagram.com/real_embassygardens/> [accessed 15 March 2023].

20 ‘Ballymore on Trustpilot’, Trustpilot, 2023 <https://www.trustpilot.com/ review/www.ballymoregroup.com> [accessed 15 March 2023].

These two swimming pools present two examples of government policy in response to crises. The Nine Elms Baths responded to a crisis of hygiene, creating a space for the oppressed community surrounding it to access sanitary facilities for their bodies and their clothes, simultaneously embedding itself in the life of the people that used it and placing value on their needs. The Skypool is the jewel in the crown of a mass luxury development built in the midst of a national housing crisis which is intended to act as an economic investment for the wealthy to own but not use, removing potentially affordable housing stock and inflating the market, placing the economic gain of the wealthy above the needs of people. This disease of privatisation is infecting every corner of public space, seeping out into the streets and taking control of every inch of land.

Anna Minton describes the result of this as “architecture of extreme capitalism, which produces a divided landscape of privately owned, disconnected, high security, gated enclaves side by side with enclaves of poverty which remain untouched by the wealth around them... creating a climate of fear and growing distrust between people... which erodes civil society”21. It is a direct result of capitalism and the consumerist society it produces which places profit above all else and it is impossible to imagine how this could change without a dramatic shift in the values of society as a whole.

Despite their clear benefits, swimming pools and bathhouses are extremely sensitive sites of conflict. Victorian baths such as the Nine Elms Baths provided an essential service to those in need, but also acted as instruments of segregation based on class, gender and race. The Baths and Washhouses Act, implemented by the UK Parliament responded to a crisis of hygiene, but acted out of self-interest, preserving the industrial working class for their own economic benefit

and reducing the spread of disease from the working population to the upper classes. It also came with strict regulation on how the users of the baths should act, stipulating strict distances which men and women had to maintain in order to ensure “adequate privacy”22, heavily favouring the men and restricting women’s access to facilities. This is apparent in the Nine Elms Baths which had 32 second class and 6 first class baths for men, but only 9 second class and 3 first class baths for women, implementing a strong hierarchy between classes and genders. In addition to this, the racism which still pervades these spaces added another level of segregation to the hierarchy. Despite these factors, the impact of the baths on the surrounding community was overwhelmingly positive and this was thanks to the people who created it, used it and moulded it. John Archer, London’s first black mayor provides a powerful case study of the baths’ success. He was a member of the Nine Elms Swimming Club and a progressive liberal politician sitting on the Battersea Borough Council where he campaigned for improved wages for council workers. In 1913 he successfully ran for the position of mayor, delivering a powerful victory speech:

“My election tonight means a new era. You have made history tonight. For the first time in the history of the English nation a man of colour has been elected as mayor of an English borough. That will go forth to the coloured nations of the world and they will look to Battersea and say Battersea has done many things in the past, but the greatest thing it has done has been to show that it has no racial prejudice and that it recognises a man for the work he has done.”

In a growing climate of privatisation and increasing loss of public space, perhaps this provides some inspiration for action. It is the people who use these spaces who form them and create their value, through investments of time and passion into moulding a space which can facilitate community and social change.

One of the few successful examples of how the social value of a public space has been prioritised is the Southbank Skate Park. The undercroft beneath the Royal Festival Hall was appropriated

22 Baths and Washhouses Act

in the 1970s by skaters who were attracted to the covered, smooth space and quickly made it their own. It became filled with graffiti, ramps and people during all hours of the day, establishing it as the UK’s home of skating, developing freely and organically through the efforts of its users. In 2013 the Southbank Centre published plans to turn the space into a commercially funded retail zone filled with restaurants and shops, erasing the 50 years of skating history. As a reaction against this Long Live Southbank was formed as an organisation dedicated to campaigning against the redevelopment of the undercroft and allowing the community to evolve creatively. The campaign was successful and in September 2014, Long Live Southbank signed a Section 106 agreement with the Southbank Centre guaranteeing the space’s long-term future.

In the current economic and political climate, perhaps the only possible way for these spaces to be recognised is through the agency of individuals. It is only through physical appropriation of space and fierce protest to remain that they can be truly understood for their social value.

Kevin Watson returned home one November evening to his shared ownership flat in Embassy Gardens, Nine Elms. It was his 87th birthday and he had spent it across the railway tracks at the local community bridge club in the Patmore Estate with a few friends, reminiscing about old times, before the area had been pillaged by faceless developers erecting faceless towers, a time when community thrived. They weren’t rich but they didn’t need much, supported by each other and the few community halls, pubs, and churches that brought the neighbourhood together. Kevin had worked at the Vauxhall Cold Store, a building which essentially was a 37,000 cubic metre refrigerator until its closure in 1999, forcing his retirement with very little pension, resulting in him still paying rent to Ballymore developers for his 1 bed flat. The conversation stumbled on for hours, interrupted by cake and a mumbled version of ‘Happy Birthday’ until they got onto the topic of how they had become friends in the 50s through the swimming club at the Nine Elms Baths. Kevin had been an excellent swimmer in his youth, specialising in backstroke and had competed nationally. They laughed and joked, telling stories of pranks they had pulled on each other, like when they had hidden Andrew’s clothes while he was in the slipper baths, placing them just in front of the ladies’ changing rooms. Kevin had met his late wife Lydia at the baths during one of the swim club’s summer parties, a big occasion for the neighbourhood. They talked about the fantastic boxing matches they had witnessed there and the rousing socialist rallies. Kevin had never been very interested in politics, more concerned with getting his head down and working hard to make a living. The evening eventually came to a close when Janice inevitably began to nod off, signalling the time and ending this treasured period of escapism.

As Kevin wandered home, passing beneath the railway tracks and emerging onto his street, littered with crisp packets and orange Lamborghinis, he began to think about the baths, how they had brought him such joy, and that perhaps he hadn’t appreciated the value that it brought to his life. He remembered how, when the baths were up for demolition there had been a campaign to save them, led by the socialists who used to meet there, and he had not paid much attention to it, focusing instead on his work. As he pondered this period of his life he began to feel a deep sense of regret. He had never stood for anything in his life, always giving over to the financial

powers that be without protest. What if he had stood up for those baths? What if he had paid attention to the plans to turn his home into an ‘opportunity area’? Could he have stood up and fought for the places he and his friends had inhabited and cherished? Perhaps they could’ve stopped it turning into this desolate forest of deadly high-rise daggers. Perhaps they could’ve preserved some form of community. Kevin went to sleep that night deeply distressed.

The following morning he set out on his daily walking route, down Battersea Park Road, hugging the side of the buildings trying to avoid the roaring vans that rammed past, sucking the pavement air with them. It was a cold and windy morning and he didn’t pay much attention to the ruthless advertising blaring noise and light at him as he numbly walked through the tight corridors around Battersea Power Station. He was deep in thought, unable to shake the troubling what-ifs which had stirred him the previous night. He continued down Cringle Street, passing the site of the former Nine Elms baths, now completely unrecognisable with brick slips and plastic panels cladding another luxury development which will be advertised in Cannes and Monaco as ‘modern London living’. In that moment he felt like a true alien, a complete outsider, excluded from the place he used to call home. As he continued his walk back towards his flat, an anger was growing within him. How could this happen? How could the government allow such a violent massacre of precious social space? By the time he reached the Skypool he was physically shaking with rage. Staring up at this empty rippling piece of blue, he became acutely aware what crimes had been committed. That water belonged to him. It had been viciously ripped from his community along with countless other amenities and housing in order for rich developers to become richer. Something had to be done, this was his moment to stand. As he descended back into his cave, through the dark corridors he began to form a plan.

Pete, Andrew, Janice and Tracy were all on board with Kevin’s idea. They too, had been harbouring similar feelings and were ready to take action.

In the early hours of Tuesday morning they gathered, armed with protest signs, pickaxes and an inflatable pool and rehearsed the plan. This was it - the point of no return. The five pensioners began their

march on Embassy Gardens, filled with an anxious anger and ready for a fight. They burst through the front doors of reception, shouting and screaming, almost pulling the glass panels off their hinges and startling the security guard awake. He could not believe his eyes as he pulled himself back onto his chair, in complete shock and powerless to stop the scene that was unfolding in front of him. The army of five marched straight past the front desk and into the central elevator. The gold-plated doors slowly closed in front of them, muting their chants as they ascended up the building towards the Skypool. The security guard frantically picked up his phone and called for backup, unable to describe what he had seen and utterly terrified. The rowdy rabble travelled through the tower, waking every resident as they went. Baffled couples in their dressing gowns and slippers emerged from their apartment doorways into the corridors, angry and confused as to what was happening. The five protestors screamed through the 10th floor corridors purposefully, heading straight for the famous suspended water bridge. They sounded like an army, driven wild with anger prepared for anything. They charged straight through the doors to the pool like a battering ram and fastened it shut behind them with chains and padlocks. Step 1 complete.

They burst out into the open air, landing on the pristine pool decking, 35 metres up. As their heavy breathing subsided they noticed the tranquil morning air being permeated by a droning above them. Two helicopters were hovering, eyes trained on their position. Their loudspeakers were shouting something inaudible above the whirring blades. The furious five suddenly felt a pang of fear race through them. As they exchanged worried glances, frozen to the spot another noise began to pierce the machinery above them. It was the sound of people. As they peered over the side of the balcony, they saw the ground below them filled with faces staring back up at them. Film crews and journalists were interspersed in hordes of people all chanting and protesting in support of the activists. News had got out and a frenzy had spread across London, inspiring and stirring people who had been feeling the deep injustice and disparity in their own neighbourhoods. They came with signs, towels, swimming trunks and were willing on the pensioners above. Reinvigorated by this display of solidarity, the gang snapped back into action, continuing the plan they had set out. By now there were security guards at the door, trying to push their way through. They had to act fast. Armed

with their pickaxes, they dived into the pool, reliving their youth at the Nine Elms Baths and headed straight for the centre. Taking it in turns, they held their breath and swam to the bottom, staring straight at the ground. They began to chip away at the clear acrylic of the pool bottom, creating a small indent in the thick slab. It didn’t have much of an impact at first but as they continued to alternate, submerging themselves and hammering the structure a small crack began to appear. The security guards stood powerless, baffled at what was unfolding before them. The crowd below became louder and louder, encouraged by every new crack that formed. They began to erect an inflatable pool beneath the floating protestors, collecting the few drops of water that were beginning to fall. They were close now. Kevin took one final breath and dived down, preparing for one final swing of his axe. As the tip connected, the smaller cracks began to connect, water rushed in to fill the growing gaps. The pensioners frantically swam to the pool edge, fleeing the impending chaos that was about to occur and grappled for the stainless steel ladder. They could feel the pool giving way beneath them, the weight of the water shifting downwards as it was sucked into the newly formed plug hole. There was an almighty crash as the clear structure finally gave way, splintering into shards and exploding like a giant waterfall down towards the inflated pool below. A shimmering shower of water and acrylic soaked the waiting public, drenching them in its expensive contents. There was a scream, followed by a celebratory roar as the crowd converged on the now full inflatable pool. Kevin looked across the void he had created and down at the party happening below. He knew he would be in trouble, but he was at peace. This act had given rest to his tormented conscience and would change the fate of this place he called home, of that he was sure.

1,000,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 £ £ - £ - £ - £ £

Aarons, S., Getty Images, and W. Norwich, Poolside With Slim Aarons (Harry N. Abrams, 2007)

Aarons, Slim, Poolside Gossip, 1970, Photograph

Adiv, Naomi, ‘Paidia Meets Ludus: New York City Municipal Pools and the Infrastructure of Play’, Cambridge University Press, 2015

‘Ballymore Hell (@ballymorehell)’ <https://www.instagram.com/ ballymorehell/> [accessed 15 March 2023]

‘Ballymore on Trustpilot’, Trustpilot, 2023 <https://www.trustpilot. com/review/www.ballymoregroup.com> [accessed 15 March 2023]

Baths and Washhouses Act, 1846

‘Builders’ Journal and Architectural Record’, 1898

Coates, Colin, ‘Why You Don’t Need to Be Swimming in Cash to Install a Pool at Home’, Mail Online, 2009 <https://www.dailymail. co.uk/property/article-1197150/Why-dont-need-swimming-cashinstall-pool-home.html> [accessed 14 March 2023]

Colin, Thom, and Andrew Saint, Survey of London: Battersea, L (Yale Books, 2013), XLIX

‘Contract Journal’, 1906

Debord, Guy, La Société Du Spectacle (France: Buchet-Chastel, 1967)

Donaldson, Grant, ‘A Walk through Nine Elms’ (Royal College of Art, 2022)

Eckersley O’Callaghan Engineers, ‘Sky Pool’, Eckersley O’Callaghan

<https://www.eocengineers.com/projects/sky-pool-246/> [accessed 15 March 2023]

Editorial, ‘The Guardian View on Swimming Pools: A Public Good for Everyone’, The Guardian, 14 March 2023, section Opinion

<https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/mar/14/ the-guardian-view-on-swimming-pools-a-public-good-for-everyone> [accessed 15 March 2023]

Elmgreen and Dragset, The Whitechapel Pool, 2018

‘Fully Transparent Sky Pool Connects Two Housing Blocks in London’, Dezeen, 2021 <https://www.dezeen.com/2021/06/04/ transparent-swimming-pool-battersea-london-hal-sky-pool/> [accessed 15 March 2023]

‘HAL Architects - Embassy Gardens Legacy Buildings for Ballymore’, Hal-Architects <https://www.halarchitects.co.uk/copyof-embassy-gardens-legacy-buildings> [accessed 15 March 2023]

Harvey, David, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry Into the Origins of Cultural Change (Wiley, 1992)

Harvey, David, The Urban Experience (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989)

Hinde, John, Butlins Monsey - The Indoor Heated Pool, 1960, Photograph

Hockney, David, A Bigger Splash, 1967, Acrylic on canvas

karen2082, ‘A Brief History of Swimming Pools’, Worlledge Associates, 2023 <https://www.worlledgeassociates.com/post/abrief-history-of-swimming-pools> [accessed 14 March 2023]

Lefebvre, Henri, Everyday Life in the Modern World (Taylor & Francis, 2017)

Lefebvre, Henri, The Production of Space (Wiley, 1992)

Lyons, Michael, Luke Murphy, Charlotte Snelling, and Caroline Green, What More Can Be Done to Build the Homes We Need? (Institute for Public Policy Research, June 2017)

Minton, Anna, Ground Control: Fear and Happiness in the TwentyFirst-Century City (Penguin Books Limited, 2012)

Mitrasinovic, M., Total Landscape, Theme Parks, Public Space, Design and the Built Environment Series (Ashgate, 2006)

Nast, Condé, ‘Iconic Neutra-Designed Home Featured in Slim Aarons Photo Hits the Market’, Architectural Digest, 2020 <https:// www.architecturaldigest.com/story/iconic-neutra-designed-homefeatured-in-slim-aarons-photo-hits-the-market> [accessed 14 March 2023]

Nine Elms, ‘Looking Back: Nine Elms Baths’, 2020 <https:// nineelmslondon.com/features/looking-back-nine-elms-baths/> [accessed 30 March 2022]

People in Housing Need (London: National Housing Federation, 15 September 2020)

Powell, Ben, ‘Long Live Southbank Interview’, Slam City Skates London, 2019 <https://blog.slamcity.com/long-live-southbankinterview/> [accessed 11 December 2022]

Ramsey, Sherwood, Historic Battersea Topographical Biographical, 1913

Rose, Steve, ‘Just Add Water’, The Guardian, 17 July 2006, section Art and design <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2006/ jul/17/architecture.watersportsholidays> [accessed 14 March 2023]

Swim England, A Decade of Decline: The Future of Swimming Pools in England, 2021

‘Swimming and Gender in the Victorian World’, The International Journal of the History of Sport, 24.5 (2007), 586–602 <https://doi. org/10.1080/09523360601183137>

Talling, Paul, ‘Derelict London Pools and Baths’, Derelict London

<https://www.derelictlondon.com/derelict-london-pools-and-baths. html> [accessed 2 January 2023]

‘The Real Embassy Gardens (@real_embassygardens) • Instagram Photos and Videos’ <https://www.instagram.com/real_ embassygardens/> [accessed 15 March 2023]

Wainwright, Oliver, ‘“Every Square Inch Monetised” – Is Battersea Power Station Now a Playground for the Super Rich?’, The Guardian, 5 October 2022, section Art and design <https://www. theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/oct/05/every-square-inchmonetised-battersea-power-station-playground-super-rich> [accessed 15 March 2023]

Wainwright, Oliver, ‘Penthouses and Poor Doors: How Europe’s “biggest Regeneration Project” Fell Flat’, The Guardian, 2 February 2021, section Art and design <https://www.theguardian.com/ artanddesign/2021/feb/02/penthouses-poor-doors-nine-elmsbattersea-london-luxury-housing-development> [accessed 15 March 2023]

Wandsworth District Board of Works, Sanitary Department Report for 1866, 1866

Weaver, Matt, ‘Opportunity Knocks for Key Areas in Livingstone’s London’, The Guardian, 10 February 2004, section UK news

<https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/feb/10/london.london> [accessed 15 March 2023]

‘What Decade Are These Vintage Pool Ads From?’, Me-TV Network

<https://www.metv.com/quiz/what-decade-are-these-vintage-poolads-from> [accessed 14 March 2023]

Wilcox, Steve, John Perry, Mark Stephens, and Peter Williams, 2017 UK Housing Review (Heriot Watt University, 2017)

Figure 1 - Hinde, John, Butlins Monsey - The Indoor Heated Pool, 1960, Photograph

Figure 2 - Elmgreen and Dragset, The Whitechapel Pool, 2018, Installation

Figure 3 - Map of Battersea and Nine Elms, 1910, <https:// digimap.edina.ac.uk/> [accessed 14 March 2023]

Figure 4 - Boucher, Adolphe Augustus: Bedford Lemere And Company, Public Baths, Battersea Park Road, 1901, Photograph. Historic England Archive

Figure 5 - Boucher, Adolphe Augustus: Bedford Lemere And Company, Public Baths, Battersea Park Road, 1901, Photograph. Historic England Archive

Figure 6 - Boucher, Adolphe Augustus: Bedford Lemere And Company, Public Baths, Battersea Park Road, 1901, Photograph. Historic England Archive

Figure 7 - Boucher, Adolphe Augustus: Bedford Lemere And Company, Public Baths, Battersea Park Road, 1901, Photograph. Historic England Archive

Figure 8 - 7UP Advertisement, 1960

Figure 9 - Aarons, Slim, Poolside Gossip, 1970, Photograph

Figure 10 - Ecoworld Ballymore, Embassy Gardens image advertising the Skypool, 2021, < https://www.embassygardens.com/sky-pool/> [accessed 4 April 2023]

Figure 11 - Ecoworld Ballymore, Embassy Gardens image advertising the Skypool, 2021, < https://www.embassygardens.com/sky-pool/> [accessed 4 April 2023]

Figure 12 - Donaldson, Grant, Battersea Park Road, 2022, Photograph, In possession of: the author

Figure 13 - Donaldson, Grant, A Tale of Two Pools, 2023, Drawing, In possession of: the author