changing rooms

Grant Donaldson Royal College of Art ADS7

Grant Donaldson Royal College of Art ADS7

3 introduction a tale of two pools bodies of water changing space control rooms changing behaviour changing perception reflections conclusion 5 7 25 91 99 117 159 231 242 Contents

4

Changing Rooms explores the social perception of acceptable behaviour in relation to context, questioning what makes certain acts acceptable or unacceptable within a space?

The project serves as a critique of the behavioural control within privately owned public spaces for the purpose of capital gain, focussing on the recent redevelopment of Battersea Power Station as a site of investigation.

I use the swimming pool as a lens to explore and illustrate the issue for two reasons:

Bodies of water are a hub of eccentric human life, where people feel comfortable removing all clothing, strutting along the poolside or basking in the sun, regardless of whether they intend to swim or not; actions which would be completely outrageous in any other public context. Providing an extreme example of how acceptable behaviour is linked to context.

Battersea and Nine Elms have a deep relationship to bodies of water historically and presently. Beginning as marshland, the area then became the main water supplier for London, holding reservoirs for the Vauxhall and Southwark Water Company. In 1895 a public baths was built on the site to provide essential washing facilities for the local community who lived among the heavily industrialised environment which became known as ‘The People’s Hall’. And of course, the Skypool! Nestled in the largest regeneration project in Europe, this clear pool suspended between two towers of the Embassy Gardens development is exclusively accessible to certain residents of the largely uninhabited multi-million pound apartments, tantalising the public below.

Through the use of performative interventions at 1:1 scale, the project further probes the relationship between behaviour and context, investigating whether behaviour can change the perception of space.

5 Introduction

what makes behaviour acceptable or unacceptable within privately owned public space?

how can behaviour change the perception of space to reveal underlying behavioural control?

6

a tale of two pools

Battersea and Nine Elms have gone through dramatic change within the last ten years, transforming from a poor neighbourhood into the apple of the investor’s eye; a jungle of glass skyscrapers rising from London’s South Bank, creating billions in assets of high-end residential apartments and offices.

The Nine Elms Baths (1901-1970) were built in a time and place of extreme crisis. Among a heavily industrialised environment, the working population had no access to washing facilities and battled daily to escape the soot which plastered itself over every surface. The baths provided an essential function to the surrounding community, allowing them to wash their clothes and bodies, and enjoy the activity of swimming. In addition to this, the space was used for social events such as boxing matches and political rallies, leading to a space which fostered community and facilitated social reform. A few hundred metres from this site is the newly built Skypool which is suspended 10 storeys up between two towers of the Embassy Gardens luxury development. It is exclusively accessible to high paying owners of the multi-million pound apartments which are completely empty, bought as safety deposit boxes for outside investors. These two bodies of water on the same site provide two polarising examples of governmental attitudes towards social and economic value. In a new era of crisis, when over 1 million households are waiting for social homes, high end luxury developments are the priority, placing economic gain for the wealthy above the needs of people. This illustrates a clear change in the perception of value and the function of residential and social spaces, from a social need to a capital investment.

The recently opened redevelopment of Battersea Power Station is part of this ‘Opportunity Area’ and exhibits a prime example of extreme privatisation; creating a space which is publicly accessible for the purpose of extracting money from the visitors to the site through the commodification of the human experience.

The rational economic strategies of these spaces which exist to generate capital are threatened through the unpredictability of human behaviour and so the physical space is carefully designed and monitored in order to control the behaviour within it.

7

Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms

I have chosen Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms as my specific site of intervention because it is a very recent and extreme example of privatised public space and because of its historic and current links to bodies of water.

The site is an area in which I previously explored through my research dissertation ‘A walk through Nine Elms’ which traced the complete erasure of local community in order to create a tabula rasa for the largest redevelopment project in Europe.

Abstract:

Nine Elms has gone through dramatic change within the last ten years, transforming from a poor neighbourhood into the apple of the investor’s eye; a jungle of glass skyscrapers rising from London’s South Bank, creating billions in assets of high-end residential apartments and offices. This gentrification on a gigantic scale has been forced upon an area which has long been the victim of classist attack. From being London’s farmland to its dumping ground, it is a patch of land which has been pushed and pulled into serving the city without regard for its inhabitants. This new development magnifies the historical attitude, sacrificing the livelihoods of the families who live in the area for the city’s unquenchable thirst for development.

The images of the Vauxhall Nine Elms Battersea “opportunity area”, often taken from miles away, with a bright blue sky, portray it as a kind of Emerald City. Often coupled with shots of identical apartments, inexplicably expensive and completely un-lived in, the image advertised is one of financial investment for the future. Although these increasingly common images invoke all the connotations of cosmopolitan luxury that entice money, they fail to address the impact that they have had on the existing area and its community. The people, businesses, and relationships that built the identity of Nine Elms have been swept away to make space for these placeless money pots. A tabula-rasa has been created, annihilating any trace of the past and this has been done in the space of a few short years.

This project investigates the impact that the Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms developments have had on the area and its community through a lens which has not been shown in the promotional renders, one of human experience. This has been explored through the deeply human activity of walking as a method of sensing - an activity which is deeply embodied in the experience of a place and the most ancient means of exploration and research.

As an accompaniment to this walk, an archive has been created of photographs which have been taken along the route, providing an alternative view of the place as it is today and exposing the reality of the effects that the developments are having on the community. As part of this research, an analysis of the methods of walking, photography and archive has been made as a critical reflection on the processes and their relationship to the academic context and specific subject matter.

8

9

a walk through nine elms grant donaldson

10

11

12

13

A Tale of Two Pools

Battersea and Nine Elms, located on the southern bank of the Thames have long been sites of oppression, used by the upper class of London as a dumping ground for agricultural and industrial industries. The area began as marshland, it was described by Ramsey as “a despised oasis, flanked with a few ramshackle huts, inhabited by a class of people who made day hideous and night dangerous, for it was not safe for decent people to pass the dismal swamp after dark, as highwaymen and footpads infested the roads”. From the 17th century, Battersea became the site of a growing number of industries thanks to its placement close to central London and its connection to the river which was used as the predominant transport method for heavy goods. The arrival of the railways in 1830 sparked growth of heavy industry and the area quickly became synonymous with factories and workshops producing cement, chemicals, candles, flour, oil, paint, turpentine, sugar, starch, soap and vinegar. Larger service industries such as building, engineering, water, gas and electricity also became increasingly prominent along the riverbank. These industries engulfed the small village that was once there, transforming the landscape into a compact cluster of chimneys, spires, cranes and factory roofs towering over tightly packed Victorian housing which housed the low income workers. William Connor, Battersea’s Medical Officer wrote in 1866, “Battersea is very peculiarly circumstanced; first, in having become a very large manufacturing district, and, secondly, in having a labouring population daily and hourly enlarging... to an extent that would hardly be credited”. This labouring population lived in close proximity to the heavily polluting and noxious industries which left black soot plastered over every surface, without laundry facilities in their homes. The local sanitary inspector in 1896 claimed to have visited every house in the district, stating that there was only one house with a bath in the whole ward. He also stressed that swimming baths were urgently needed after several drownings in the river reservoirs.

In 1844, the Committee for Promoting the Establishment of Baths and Wash-Houses for the Labouring Classes was formed which petitioned for a bill for the regulation of public baths. In 1846 the bill was introduced which became the 1846 Public Baths and Wash- houses Act. This was the first legislation to empower British local authorities to fund the building of public baths and wash houses.

‘WHEREAS it is desirable for the Health, Comfort, and Welfare of the Inhabitants of Towns and populous Districts to encourage the Establishment therein of public Baths and Wash-houses and open Bathing Places:’

The proposal for a new baths at Nine Elms was approved by the Vestry in 1895 and a site was purchased from the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company on the corner of Battersea Park Road and Cringle Street using funds provided by the government through the Public baths and Washhouses Act. A competition was run in 1897 for the design of the baths with, at the Library Committee’s request, a reading room and the 15 entries, none of which were greatly received by the press; “none have much pretension to be called Architecture”, were judged by the Vestry’s surveyor. The winning design was by Francis J. Smith who was from Battersea. It was described as being “in the Renaissance style of architecture, plainly treated, of stock brick with redbrick facings and Portland-stone dressings to the numerous mullioned windows.” At the centre of the plan was the 150ft by 50ft swimming bath, arranged parallel to Cringle Street. This was the largest covered swimming bath at the time it was built and was also used to host public entertainment in the Winter; with the bath covered over and the galleries which surrounded it at first floor level full, the building could host up to 1,500 people. At the awkward angled corner of the plot was placed the reading room, originally designed to follow the angle of the roads, it was later changed following the press criticism to a semi-circular bay, apparently taken from one of the unsuccessful competition entries. To the West were the women’s slipper baths and separate entrances for men and women. At first floor level was the superintendent’s

14

15

Nine Elms Baths West elevation, 1901

Most public baths and washhouses from this era have fallen derelict - ruined by cut funds as a result of policy changes, cheaper flights abroad, a trend towards privatisation and a change in the social function of the swimming pool. The internet is inundated with images of historical pools either abandoned, demolished or converted into offices and apartments. Paul Talling runs a website titled Derelict London which explores through walking tours, photographs, personal stories and blog posts how many of these buildings have been changed or lost. This mass exodus of pools has coincided with the mass privatisation of Britain’s housing and infrastructure following the measures introduced by the Thatcher government such as the Right-to-Buy scheme which aimed to shift the majority of the UK’s housing stock from publicly to privately owned in order to encourage a free market economy and swing voters from left to right. With more of the population owning their own homes, they would be more inclined to favour the Conservative policies away from public spending and towards private ownership.

These policies coincided with a boom in mass image-based media production through photography and television, an industry dominated by the United States of America under the leadership of former actor Ronald Reagan. Billboards, magazines and TVs were dominated by images of the ‘American Dream’ depicting smiling, young, white families who had earned their own house and all the modern conveniences that came with it through Capitalism and the free market economy. These images were created during an intense period of the Cold War as Capitalist propaganda in the fight against Communism and were vehemently supported by the UK government. Much of this imagery was aspirational, inspiring a desire among the public to attain the lives depicted and the swimming pool was a key element in this strategy, shifting the function of the pool from a leisure facility to a symbolic display of wealth, the value of the pool from social and health to economic investment, and the ownership of the pool from public communal infrastructure to private residential object. The photography of Slim Aarons provides an excellent example of this change in perception, framing scenes of luxury, opulence and extravagance arranged around a pristine rectangle of unperturbed blue. Poolside Gossip depicts a scene by the pool of the iconic Richard Neutra-designed Kaufmann House in Palm Springs. The photograph encapsulates this propaganda of the modern America, where impeccably dressed women can recline by the poolside, sipping champagne and gossipping about their husbands who have bought their elegantly designed modernist house through the

honest spirit of Capitalism, showing off their swimming pool without actually swimming in it.

This shift in value and perception eagerly spread from Palm Springs to the United Kingdom, despite the stark differences in weather conditions, and combined with the governmental policies and cheaper package holidays abroad, forced the mass closure of many public pools, a movement which has not ceased. A property article in 2009 estimated that there were 210,000 private pools in the UK, with an annual increase of 2,500 and Swim England’s 2021 report A Decade of Decline estimated a 40% decrease in the number of public swimming pools by 2030.

A few hundred metres from the former site of the Nine Elms Baths sits the epitome of this shift towards privatisationthe Skypool, nestled in the largest regeneration project in Europe as part of the Vauxhall, Nine Elms and Battersea “Opportunity Area” - a jungle of high-rise, multi-million pound flats privately owned and largely uninhabited. The clear pool sits 35m above ground spanning the 15m gap between two towers of Ballymore’s Embassy Gardens development, looking directly out at the US Embassy’s shiny ETFE panels. It is constructed in clear acrylic, the side walls having a thickness of 180mm and 3.2m depth. Its base is 360mm of solid acrylic supporting the pool’s own weight of 50 tonnes and 150 tonnes of water. The height of the pool and its consequent swaying from wind means that the two ends are placed on movable bearings in order to adjust and adapt to these shifts. The engineers, Eckersley O’Callaghan describe the project as “The first of its kind and a truly remarkable feat of engineering”. The pool was opened in May 2021 with a barrage of social media advertisement, infiltrating our devices and stirring up a frenzy of excitement as we eagerly watched in amazement as well-dressed young men and women with perfectly toned abs elegantly glided through the floating box of crystal blue water. This excitement was swiftly cut short, however, when it became apparent that the pool was exclusively available to residents of the multi-million pound apartments. Although privately accessible, it is highly publicly visible from the ground below it - a very different viewpoint to the drone shots published on its opening. Staring up at this almost invisible box feels extremely underwhelming. Rather than the advertised oasis filled with athletic swimmers, it is mostly empty, with the occasional figure spotted performing an awkward doggy paddle. The story is the same for the whole development, where apartments are completely vacant, designed to the minimum space requirements in order to act as safety deposit

16

17

Aarons, Poolside Gossip, 1970

Slim

Embassy Gardens image advertising the Skypool

18

Embassy Gardens image advertising the Skypool

boxes for foreign investors. The new housing stock does not function as homes for the community to live in, but economic investments for outside buyers to be left uninhabited, and this is the case for the whole of the Vauxhall, Nine Elms and Battersea ‘Opportunity Area’ where tens of thousands of these apartments have been built but unused. This question of function and value of housing is echoed from that of the swimming pool, where it is now seen as a status symbol, a display of economic wealth which tantalises the local community who have been violently displaced in order to construct it.

The UK is in a housing crisis, with one in three adults affected by it. A desperate need for housing and particularly ‘affordable housing’ is widely documented and accepted. The 2017 UK Housing Review Briefing Paper argued that while supply is of critical importance, “so is the rather more neglected issue of affordability, in both the private and social housing sectors.” In the foreword to the June 2017 IPPR report, What more can be done to build the homes we need? Sir Michael Lyons said: “We would stress that it is not just the number built but also the balance of tenures and affordability which need to be thought through for an effective housing strategy.” This is echoed in research commissioned by the National Housing Federation and Crisis from Heriot-Watt University, which identified a need for 340,000 homes each year to 2031 of which 145,000 “must be affordable homes”.

This desperate need for housing is not portrayed in the development of Nine Elms, with only 18% of new housing in the area classed as affordable, against the lawfully required 40%. This is greater exacerbated by the definition of ‘affordable’ as 80% of market value which is still unattainable for the majority of the population. Many of the affordable housing blocks of the Nine Elms developments are shared ownership flats which means that the residents can own a quarter of the property and pay rent to the developer on the rest. A large number of these are situated on the site of Embassy Gardens, stuffed behind the penthouse apartments, against the railway line, hidden from sight behind a veneer of luxury. The roads are littered with construction debris, flanked by harsh orange barriers and barbed wire fences. Lamborghinis line the curbs, pasted with parking tickets, unapologetically stealing the space of the families who occupy the substandard accommodation. The sound of rushing trains overhead interrupts the groaning of surrounding construction sites, penetrating the plasticclad walls. The flats are accessed through colloquially

named ‘poor doors’; hidden entrances, obscured from public view out of embarrassment which lead to dark, long corridors, unfurnished and identical. These apartment blocks have been constructed to the bare minimum standards lawfully required, packing as many units as possible into the cramped space, with reports of leaks, disconnected pipes, exposed wires and broken windows posted all over Instagram and Trustpilot pages such as @ballymorehell and @real_embassygardens. The scathing testimonies tell a story of a group of people - the only real inhabitants of the developments, who have been exploited and oppressed by a “predatory company”, using them as a “cash cow so that they could continually squeeze you for life”.

It seems unbelievable that these companies can get away with this, but it is thanks to specific government policies and decisions which have allowed these conditions to exist. The idea for these ‘Opportunity Areas’ was first proposed by Ken Livingstone, the socialist mayor of London in the 2004 London Plan, who envisioned Nine Elms, along with King’s Cross, Elephant and Castle and Paddington as areas for investment which would encourage tall buildings in the hope that large amounts of funding could be used for the public good. It was proposed that half of the housing would be affordable and developers would have to provide a financial viability statement if this figure was not possible. Fast-forward to 2012 when the plans for the area were being drawn up and the Conservative led coalition government was in power, with Boris Johnson as London Mayor. A series of policy changes in planning laws changed the definition of ‘affordable’ to 80% of market value and put financial viability at the centre of planning policy, prioritising profit over all else. This allowed financial viability statements to become a ‘get-out’ clause for every developer, incentivising them to reduce the amount of affordable housing in favour of increased capital gain. Nine Elms was used as the primary testing ground for this new housing economy of financial deregulation - a developer free-for-all.

19

20 ‘A Tale of Two Pools’ research drawing Embassy ElmsNine £ 1,000,000 One Million M.P. JOHNBURNS , CAPTAIN O F T H E ENIN GNIMMIWSSMLE ’NODNOLDNABULC S F I R S T BLACK MAYOR £ NINE ELMS PRIORITISING ECONOMIC INVESTMENT OVER THE NEEDS OF PEOPLE BORIS JOHNSON, MAYOR OF LONDON Nine Elms Baths 1901-1970

1,000,000

1,000,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 1,000,000 1,000,000

21

Embassy

Gardens Elms

£ £ - £ - £ - £ £

Privatised Public Space

Battersea Power Station is a very recent and extreme example of Privately Owned, Publicly Accessible Space; a phenomenon which has been spreading throughout the country and enveloping the spaces we inhabit. These spaces are privately owned and controlled, but allow the public to access them with the sole purpose of extracting money and generating capital. They are produced with the aim of transforming space into money through the commodification of the human experience, making it almost impossible to enter the space without spending money. They employ carefully designed economic strategies which set their target as the ideal human - distilling the public into a single figure to be marketed at and extracted from and design the spaces, advertisements, benches, shops accordingly. However, these rational economic strategies are threatened through the unpredictability of human behaviour and so the physical space is carefully designed and monitored in order to control the behaviour within it, transforming every visitor into the perfectly predictable spender.

This is a serious threat to common space, with the available free space to be used and enjoyed without control and oppression continuously diminishing. As shown in the case of Battersea and Nine Elms, this is aided and facilitated by governmental decisions and so the project pursues this resistance to privatisation through the agency of the individual - questioning how we can preserve and reclaim common space through acts of resistance, operating within the existing economic climate.

Control stands for the arrangement of increasingly effective technologies that prescribe normative expectations from both customers and employees and demand their fulfilment. As Ritzer suggested, the greatest source of uncertainty and unpredictability in such a rational system are the people and ‘hence the efforts to increase control are usually aimed at people’. He effectively shows how the paradigm of McDonaldization not only namelessly rationalises any given social context, but also ironically provokes a desire for social engineering. Both are immanently linked to economic studies and help realize that economy is not just a technique of production, distribution and consumption but more importantly, as Jacques Ellul has written, economic technique encounters homo economicus ‘in the flesh [as] the human being is changing slowly under the pressure of the economic milieu; he is in the process of becoming the uncomplicated being the liberal economist constructed.’ In sum, a socioeconomic system described by Ritzer attempts to govern many or all aspects of social life first by constructing a totalising theory that will see the entire world through its own goggles, and will then methodologically proceed to design the world according to such an image.

As indicated above, the main rationale of the total landscape is economic in nature. Both David Harvey and Henri Lefebvre have argued that one of the dominant aspects of post-industrial capitalist production is the transformation of space into time through the mediation of money. Space is turned into a function of distance, distance a function of time, and time a function of money. Since space is a function of money, and can be defined in monetary or economic terms, it is obvious that space can indeed be produced; moreover, since ‘space’ has been historically used to describe, categorize and organize the experience of human senses, and human experience in the world as a whole, one can assume that both space and human experience are indeed socio-economic artefacts. The question, however, is: can both space and human experience be commodified, and just how could that be done?

- Miodrag Mistrasinovic, Total Landscape, Theme Parks, Public Space

22

23

24

bodies of water

In response to the chosen context of privately owned public space, specifically Battersea and Nine Elms and the behavioural control that occurs there, I chose to explore the context of public swimming pools for two reasons:

1. The site has a deep and complex historical relationship to bodies of water and swimming pools - particularly the Nine Elms Baths and Skypool.

2. Public Swimming pools provide an extreme example of how behaviour is affected by the built context.

Beaches, rivers and pools are a hub of eccentric human life, where people feel comfortable removing all clothing, strutting along the poolside or basking in the sun, regardless of whether they intend to swim or not; actions which would be completely outrageous in any other public context.

Specifically dealing with public swimming pools, the project investigates what causes these changes in social perception and allows people to feel comfortable acting in this way, often resulting in friendships being made and stimulating an identity and sense of belonging connected to the space.

It is in the interstitial moments before and after the individual ritual of swimming where this activity occurs - in the changing room, poolside and the water’s edge. These are the spaces where transformation happens, where layers of imposed identity are shed and a common state of nakedness is assumed.

I chose to investigate these spaces through embodied research at 5 different public pools across London, engaging in the ritual of swimming and the journey towards it, recording the experience through photography, sound recordings, written text, interviews and drawings in order to try and identify the tangible and intangible changes

which occur. These are three examples of a series of sound maps I made which seek to represent the more intangible atmospheric qualities which make up the space.

This resulted in the identification of several physical elements along the journey to the pool which represent changes in atmosphere, perception and behaviour. This collage of elements from each of the pools maps that journey through the boundary, transition, bench, runway, lifeguard and edge and signifies the peeling back of layers of behavioural normality and clothing.

This map was transformed into a diorama which brings this journey into the physical experience, encouraging interaction with the viewer.

Overall, it is the presence of water, the communal gathering for the purpose of swimming, and the personal identity and sense of belonging which is felt in connection to the space which facilitates these behaviours.

25

The Springboard in the Pond

An intimate history of the swimming pool

Thomas A.P. van Leeuwen

Payne Martyn voiced the expression of the universal desire when he said of the swimming pool: “It is a walling in of a portion of an elemental thing, and owning the tenth of an acre of the deep sea and all rights and privileges thereto.” -

Phoebe Westcott Humphreys

The pool’s form is straightforward and simple, determined by its main modus usandi - swimming and playing. The pool is the architectural outcome of man’s desire to become one with the element of water, privately and free of danger. A swim in the pool is a complex and curious activity, one that oscillates between joy and fear, between domination and submission, for the swimmer delivers himself with controlled abandonment to the forces of gravity, resulting in sensations of weight- and timelessness.

To secure such a high degree of individuality and control, a privately owned piece of water is a prime requisite, yet where such is not available, segments of natural bodies of water may be isolated and identified by the eloquent paraphernalia of the craft of swimming - springboards and ladders, often attached to rafts. A pond, a lake, a river may be changed into a swimming hole by the simple introduction of a springboard, which transforms any kind of water - natural, sacred, or ceremonial - into athletic water.

Springboards have been introduced into the domain of swimming to enhance feelings of abandonment and weightlessness and as launching pads for the swimmer’s eternal game with death. The embrace of water is an erotic one, yet at the same time its cool fingers presage the immediacy of mortality.

The pool urges us to make excursions into the mysterious realms of mythology, the soothing depths of psychology, the adventurous heights of social biology, and the powerful history of religions and ideas.

Water could be in different states of sanctity. Whether contained in formally identical containers or insignificant ones - swimming pools, ponds, puddles, deep spots in a river - water commands different states if respect, even awe.

Piscine originally meant fishpond... designed to keep fish for commercial consumption, later a decorative feature in the garden of wealthy Romans, and the cistern, a reservoir for drinking water.

During the Christian period, the piscine became better known as the baptismal font, a holy water vessel found at the entrance to the Catholic church.

As the meaning of the contents of the pool changed from secular to religious and back to secular - an inversion of the original interpretation - the physical composition altered as well.

Until the advent of modern times, man’s attitude toward water had been inspired by reverence and respect. Water was seen as the element of life and of death, and as such it was sacred in all respects. And although water continued to be treated with respect, the general attitude changed from a religious to a philosophical and from a philosophical to a practical and aesthetic one, thus from sacred to profane to vulgar.

At first man, like baby that leaves the womb, swam instinctively, without fear; then, at a certain point in his evolutionary life, he developed hydrophobic anxieties. Swimming stopped being automatic and the art of swimming had to be taught.

The history of swimming became the history of the instruction of swimming. Pools began to resemble parade grounds or classrooms as insouciant paddling was replaced by drill and exercise - breaststroke, sidestroke, backstroke, crawl - and the pool became a centre for survival strategies. The springboard acted as a therapeutic means to cure the swimmer’s original fear of unfathomable depths. High boards and diving towers first cultivated, then helped him to overcome his angst. The excitement of the free fall, of ultimate weightlessness, became an addiction. At that moment the nervous balance between controlled hydrophobia and restrained hydrophilia tilted in favour of reckless hydro-ecstatica.

The swimming pool and its hydro-opportunistic attractions became the centre of family life. Activities - cookouts on Sundays, fully dressed sunbathing and uninspired swimming in Bermuda shorts, floating on rubber mattresses, playing volleyball in pools that become shallower everydaydeveloped not so much in as on or around the pool.

26

Then spreading litigation further diluted the experience; aquachutes arrived and the diving board was expelled. The relentless march of litigation, combined with an increasingly all-consuming, apocalyptic fear of, and for, the environment, led to the gradual drying up of most private as well as public swimming waters. We are left with a growing number of indoor aqua-amusement parks, where the open air has been exchanged for the stifling temperatures of the digitally controlled hothouse and swimming is replaced by hydroopportunistic voyages in serpentine tubes.

An entire history of sanctity and sacrilege, of sacredness and profanity, may be found within these developments.

27

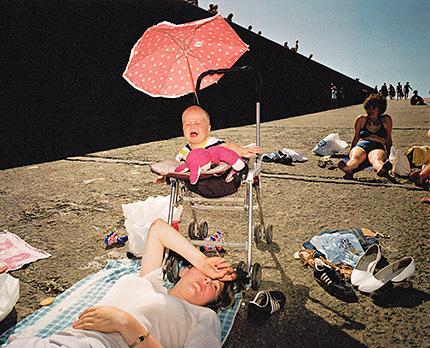

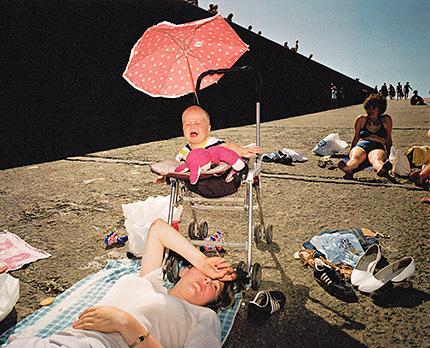

Martin Parr - Ocean Dome, Miyazaki, Japan, 1996

The Last Resort

28

Photographs by Martin Parr

Much of my inspiration for the start of this project comes from the work of Martin Parr, an english photographer who has focussed much of his work on documenting British and international seaside resorts. His work illuminates the eccentric and bizarre behaviour of beach and pool goers, freezing fleeting moments for the viewer to study. Often incorporating humour, the bold and saturated photographs are almost profane in nature, exposing the vulnerable side of people that is displayed around bodies of water.

29

30

Parliament Hill Lido

Parliament Hill Fields, Gordon House Rd, London

NW5 1LT

Public Lido

Owned and operated by the Corporation of London

31

11am Thursday 13th October 2022

Walking into the space, I felt a change in atmosphere. An immediate warmth and comfort brought by the relaxed and unguarded nature of people. This is their safe space, their place where they can be who they are, naked, without fear of judgement. This comes from the collective nature of everyone gathering for the same purpose. It is a distinctly individual ritual which is done alongside one another. There is complete trust - valuables are left unattended and friendships have been born out of this activity. Taking photographs felt like a breach of trust, like I was invading their safe space, a violation.

relaxed individual ritual happy community friendships shared connection catch-up club personality confidence

I felt comfortable changing by the poolside, in view of everyone - all ages and genders, with conversations going on all around me. “Are you still working there? I’ll give you a lift”. Contrasting characters interacting with ease and familiarity.

Removing clothes is removing any indication of class and background. Everyone enters the water as equals, brought together by this body of water. Personal items occupy small spaces on benches, creating a condensed portrait of each person as they shed their manufactured identities.

comfortable trust meditation alone together open walled safe space valued

32

33

34

35

36

Hampstead Heath Mixed Pond

Hampstead Heath, London

NW5 1QR

Public Natural Bathing Pond

Owned and operated by the Corporation of London

37

1pm Thursday 13th October 2022

A walk through wooded paths leads me to a small gate in a hedge. This is the concealed entrance to the pond. Framed beautifully by trees, the floating buoys and a small jetty are the only indication of human inhabitation.

Leisurely charged entry by a woman reclining on a bench, I tip-toed past the lifeguards and to the changing area - a bare, open yard which hasn’t changed since its victorian beginnings. Surrounded by trees and birdsong, it feels like the natural act to remove my clothes before making my way gingerly to the entry point.

peaceful zen contemplative individual ritual quiet

There is no chatter. I resist any noise, trying to slide silently into the water so as not to disturb the serene sounds of the surrounding wildlife.

I talked to a man in the changing rooms who has been swimming in the ponds for years. He told me about a party they had there last week which had 100 people there enjoying cake, tea and a syncronised swimming performance. The place was very quiet and empty and there wasn’t much interaction between swimmers, so this was surprising.

38

relaxed

religious hidden nature minimal humble old

39

40

41

42

Putney Leisure Centre

Dryburgh Rd, London SW15 1BL

Public Indoor Swimming Pool

Managed by Places for People Leisure Ltd. on behalf of Wandsworth Council

43

I was asked not to take photos by the lifeguards who were no older than 18. I took some photos secretly.

The place was like a machine, people coming for a purpose - mostly exercise. They did this in isolation, individually swimming up and down without interaction with anyone else. And then they leave. There is no hostility, everyone is happy to be in their individual ritual.

44 business serious

quiet

individual intimidating padlocks heated diving competition exhibition high ceiling lanes lessons community

barriers

healthy no photos light grand peaceful chlorinated machine exhausting friendly 12pm Monday 17th October 2022

45

46

47

48

Oasis Sports Centre

32 Endell St, London

WC2H 9AG

Public Outdoor Swimming Pool

Operated by Greenwich Leisure Limited on behalf of Camden Council

49

“Excuse me, this is the slow lane”. I was asked to move by someone who was fed up with the business of the pool. This was swiftly followed by a lovely conversation with a local of the pool who made me feel part of the community atmosphere which is very clear. The changing room was a hub of social activity, an enormous part of the lives of those who use it.

50

terrace

community hidden legacy sun

walled enclosed golden years private relaxed overlooking old residents busy

social

open city

11am Wednesday 19th October 2022 competitive comfortable crowded fitness belongings

trust bustling surrounded

dated

51

52

53

54

Brockwell Lido

Brockwell Park, Lambeth SE24 0PA

Public Lido

Operated by Fusion Lifestyle Limited on behalf of Lambeth Council

55

12pm Saturday 5th November 2022

It was a very cold and rainy day but the pool was still full of swimmers. There was one sheltered tent by the poolside, about 2m x 2m with a few benches. People were huddled here, trying to get changed, leaving their valuables in the shelter while they swam. Conversations were struck up, bonding over the shared experience of the cold.

56 expensive tedious admin young slow lanes cold friendships huddled shelter happy trust turnstiles

enclosed open walled no photos fitness frustrating

57

58

59

Mapping Sound Changing Rooms

Swimming pools are a very sensitive environment filled with people who are exposed and vulnerable. This helps catalyse relationships but can make it an inappropriate place to take photographs. In order to record the atmospheres of each space through the journey of moving between the different layers, I used sound recordings.

I used these recordings to create a visual map of the sounds through the space. I created a notational language which is inspired by the work of Wassily Kandinsky who was inspired by sound and music and created his own abstract language of painting which he wrote in his book Point and Line to Plane

This language creates a map of the space in plan and allows the viewer to trace the journey between thresholds and environments.

The key to the right illustrates this language, showing how the maps can be read in plan.

60

organic natural short harsh violent reverberating background drone noise strong bold power low murmur sombre active loud energetic natural calm placid water calm organic dynamic musical points short manufactured harsh bursts energy organic speech human monotone beep tone

Choreographing ritual

To bring more information to the site and the behaviour found as one moves through it, I created choreography maps exploring the behaviour and route of movement through each space.

I was inspired by the scores of John Cage and the dance scores of Anna Halprin who use mapping as a way of informing the performer of the steps that they must take. These are often abstract and allow for interpretation from the performer.

61

Above: John Cage, score for ‘Water Walk’ 1959

Left: Anna Halprin, score for ‘In the Mountain/ On the Mountain’ 1981

62 Parliament

Hill Lido

63 Parliament Hill Lido

64

Hampstead Heath Mixed Pond

65

Hampstead Heath Mixed Pond

66

Oasis Sports Centre

67 Oasis Sports Centre

68

Putney Leisure Centre

69

Putney Leisure Centre

70

Brockwell Lido

71

Brockwell Lido

Catalogue of Elements

Through this research of different pools, I have identified 7 common elements which occur at each location and influence the atmosphere and behaviour within each environment. These are objects, thresholds and boundaries which facilitate and influence behaviour and connection.

72

boundary

A very obvious boundary between the outside and inside. This is usually a complete visual barrier between the pool and street, eliminating any external viewers and unpaying visitors. The boundary is usually a tall and thick wall which may or may not act as an audible barrier. Within the boundary is usually a single public entrance and exit point which funnels visitors through the reception area and ensures numbers and payments can be controlled. It will have a door of some kind which must be opened and passed through. This entrance point acts as the publicity of the building, often with large lettering denoting the space within.

73

transition

Once passing through the entrance, you will find yourself in a very constricted, dark, enclosed space which acts as a purgatory space between the external and internal. The sound quality is very reverberant and the corridors feel labyrinth like. The changing rooms are often found within this layer.

74

This is found either within the changing rooms or by the poolside. This acts as the primary catalyst for interpersonal interaction and the change in behaviour. It signifies a moment of rest, a moment to soak in the surroundings and meditate on the new atmosphere one is found in. It acts as the object which facilitates change, both physically and mentally. Clothes are removed and placed on the bench, arranged into a condensed neat pile, framing a portrait of the person to whom they once covered. This point is where most of the conversations are had.

75

bench

locker

As shown in the previous images, the bench can often function as a locker space - an area to leave valuables and clothes as you enter the water. This often tells of the character of the place and its community; more guarded, closed off spaces will use secure lockers, while more communal and trusting spaces will freely leave their valuables on the poolside.

76

This is the space between the bench and the pool. It is a circulation space which acts as a cat walk. People strut with a clear posture of relaxed freedom, rid of all covering, their natural state exposed to the people around them. This is a key moment of vulnerability and catharsis.

77

runway

lifeguard

The lifeguards are an interesting element with a very sensitive dynamic. These often change dramatically from pool to pool and their individual character and authoritative style has a large impact on the swimmers’ behaviour. They act as a protective figure although this is rarely exercised, most of the time they are a presence which simply acts as a symbol of power without ever using it. They are a reminder of the artificially constructed nature of the swimming pool, a barrier which stops the activity becoming completely free and natural. They can also be a catalyst of conversation, often starting friendly chats with swimmers.

78

edge

This is the moment right before and after entering the water. It is often lingered upon by people psyching themselves up for the cold water below. It is also a place of meditation and fear, a place where mental barriers are overcome. The paving is often different and interacted with differently through the hands and body in close proximity. There is often a dedicated entry point denoted by a ladder or occasionally a diving board.

79

Using collage as a technique of creating an image which represents multiple scenes, these images were made to convey the changes in behaviour and atmosphere at these three key elements along the journey towards the pool.

80

81 Boundary

82 Bench

83 Edge

These elements tell a story of a journey through various layers in the process of entering the water. The above collage maps this journey, highlighting the elements and behavioural changes at each stage.

This collage is a 3d anaglyph, which responds to 3d glasses being used. This adds depth to the image, emphasizing the idea of layering and moving through space.

84

85

map of elements, digital collage, 3d anaglyph

This collage journey was then transformed into a 3d diorama model which physically creates these layers alongside using the optical anaglyph effect.

This more clearly represents each moment along the journey to the pool and encourages engagement in the ritual from the viewer.

86

cropped view of diorama

87

cropped view of diorama

88

89

90

changing space

In order to illustrate the eccentricity of these behaviours and emphasise their relationship with the built environment, I brought them out of context through a series of public performances which enacted these poolside behaviours in public spaces around London. I chose to perform these acts in Coal Drops Yard, Granary Square and Battersea Power Station - three extreme examples of privately owned, publicly accessible space as a juxtaposition of behavioural control.

As David Harvey and Henri Lefebvre have both argued, these spaces are produced with the aim of transforming space into money through the commodification of the human experience. The rational economic strategies of these spaces which exist to generate capital are threatened through the unpredictability of human behaviour and so the physical space is carefully designed and monitored in order to control the behaviour within it.

These spaces threaten the complete erasure of the public realm, leading to what Anna Minton describes as “architecture of extreme capitalism, which produces a divided landscape of privately owned, disconnected, high security, gated enclaves side by side with enclaves of poverty which remain untouched by the wealth around them... creating a climate of fear and growing distrust between people”

The poignancy of these performances was felt through my own embodied experience of humiliation and anxiety, and through the comedic reactions of viewers. I believe that the Granary Square performance was particularly successful in highlighting this point as I was asked to stop by the security guards and subsequently escorted off the premises.

91

92

Mapping Performance

Each of these moments along the journey which correspond to the physical elements relate to a set of behaviours such as, moving, changing, sunbathing etc.

I used cyanotypes as a method of 1:1 mapping of the movement and behaviour found at the elements along the ritual journey. I performed the behaviour identified at the pool edge and bench while exposing the fabric to sunlight.

93

bench study, cyanotype on cotton

edge study, cyanotype on cotton

Public Performance

In order to illustrate the eccentricity of these behaviours and emphasise their relationship with the built environment, I brought them out of context through a series of public performances which enacted these poolside behaviours in public spaces around London. I chose to perform these acts in Coal Drops Yard, Granary Square and Battersea Power Station - three extreme examples of privately owned, publicly accessible space as a juxtaposition of behavioural control.

The poignancy of these performances was felt through my own embodied experience of humiliation and anxiety, and through the comedic reactions of viewers. I believe that the Granary Square performance was particularly successful in highlighting this point as I was asked to stop by the security guards and subsequently escorted off the premises.

94

95 Granary Square

96

Battersea Power Station

97

Coal Drops Yard

98

control rooms

Focussing on Battersea Power Station - The site is carefully controlled, funnelling the public into tight corridors flanked by shops and restaurants, creating a constant flow of customers. The spaces employ many of the same physical elements identified by the pool such as the bench and the boundary, but subvert their use to divert traffic and corale the visitors into the spending arenas, in order to extract money from the visitors. This video plays on the idea of the Power Station’s famous art deco control room, instead portraying it as a device of behavioural control, directing the visitor who enters the site.

I also illustrated this through a walking tour of the site which maps the publicly accessible spaces, creating a route and directing the walker through the site, highlighting the control mechanisms and revealing underlying tensions.

99

Mapping Battersea

The area of Battersea and Nine Elms has been historically deeply connected to water, from a marshland, to a port, to a water treatment facility and public bathhouse, water has been key to the identity and economic generation of the area.

Excluding Nine Elms Baths in the early 20th Century, this presence of water has been one of industrialisation and imposed power; placed in private hands for monetary gain.

The following maps illustrate the presence of water and its connection to land ownership from 1850 to present day.

100

101

I aimed to identify the relationships between the different factors that have shaped and control the site through different modes of mapping.

These maps trace the publicly accessible space and identify the physical elements and current and historic sites in the area.

These maps were made on trace and used to create a layered portrait of the site using the same techniques applied to the poolside. This endeavours to explore the similarities and contrasts between these two sites of investigation.

102

historical water

elements

103

present water

key sites

choreography

104

105 sound publicly accessible space

These maps were all combined to create a site map which explored the corridors of control which are clearly visible.

These are the publicly accessible zones which are flanked by tall towers, filled with restaurants, shopping and entertainment, and dissected with landscaped elements which manufacture these tight streams of circulation.

Through this exercise, a route was identified which traced this space and visited the key sites which are historically and presently connected to water.

The above extracts show detail snapshots of certain areas of particular behavioural control.

106

107

map of battersea and nine elms

The Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms Walking Tour

Through this mapping exercise, a clearly defined route through the area emerged which is made up of the publicly accessible space and crafted by the physical elements of control as identified earlier.

This route is surrounded by shops, restaurants and entertainment constantly projecting advertisement and is created for the purpose of extracting money.

As a way of illustrating this I developed a walking tour of the site which guides the walker through the spaces and describes and exposes the control and how it is enforced. This is interspersed with facts and observations of the site which trace its history and the political and social tensions which exist.

108

above: unfolded map, printed on trace, 700mm x 1800mm

right: folded map, 100mm x 100mm

109

110

111

Battersea Power Station and Nine Elms Walking Tour

Control Room

Alongside the site map and walking tour guide, I created a video which explores this journey through the route as seen from the walker’s perspective.

I chose to use the idea of the Power Station’s famous artdeco control rooms, subverting them to be shown as a device for behavioural control.

112

stills from control room video

113

Existing Site Plan

114 details from site plan

115

Battersea Power Station site plan printed at 1:500 on 1m x 1m paper

changing behaviour

In order to intervene in the site, I intend to use behaviour directly. We have identified that space directly affects and influences the perception of behaviour, but can behaviour change the perception of space?

Performance art provides an example of how acts can manipulate and alter perception of political and social issues as well as space. For example, Ricardo Bofill and his practice Taller de Architectura organised a series of performances in 1968 in real estate offices which acted out a different way of living in order to introduce potential buyers to their new models of housing.

I have designed a series of performances which take actions observed at the poolside and place them in heavily controlled areas of the Power Station. These range from the most inconspicuous of interventions such as a pair of flip flops left on a step, to large group interventions such as group changing or sunbathing.

As part of these performances, I have also designed a series of surreal objects which act as mediation between the two contexts - merging elements from the poolside and the Power Station to create a subtle shift in the set and probe further questions about the controlled behaviour.

Through these 1:1 interventions I aim to explore how the perception of the space is changed and reveal the underlying behavioural control that exists, prompting the performers and viewers to question what the space is and manipulating the connection between the space and behaviour.

117

Architectural Precedents

Lina Bo Bardi

Architecture ‘either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate the integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the “practice of freedom”, the means by which women and men deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world’. In the work of great architects, it is often the ability to assert control over those who experience the design that is most admired; their designs are complete, fixed masterpieces, and users of the building are expected to conform to fit. The SESC Pompéia Factory Leisure Centre (1986) and Teatro Oficina (1991), both in São Paulo, Brazil, provide an exception, where the strength of the architecture comes, in contrast, from a loosening of control, and an antipatriarchal recognition that the users’ experiences construct the architecture as much as the architect herself.

SESC Pompeia

The SESC Pompéia inhabits a former factory building that was offered as a site for demolition to the architect by the client, the Serviço Social do Comércio (SESC), a non-profit institution which acts throughout Brazil to promote health and culture among workers and their families. Rather than starting with a blank canvas, or politely revering the original building, Bo Bardi instead maintained the structure of the building in order to subvert its meaning. The factory buildings (the heavily prescriptive world of work) are reappropriated as a more loosely programmed place of leisure. The facilities house art and craft workshops, a theatre, a bar/restaurant, library, exhibition space and public, multiuse space. Two new vertical blocks house sports activities, including a swimming pool, gymnasium, rooms for dancing and wrestling, and sports courts. The varied programme for the project emerged from the informal activities that were already happening in the then disused factory since the SESC had taken ownership. This hybridity of programme allows the centre to be a citadel, or protected space, of political and cultural production and reproduction (indeed the SESC has a policy of keeping records of its activities in order to create a ‘memory’ of Brazilian culture).

118

119

Teatro Oficina

This notion is also explored in the much smaller building of the Teatro Oficina. Here, Bo Bardi developed some of the architectural ideas drawing on her previous involvement with the theatre as a set designer during the dictatorship era: found elements, such as scaffolding, trees and water, are brought into the building from the city outside, reinforcing the connection to everyday city life. Conceived of as a street that runs from the road, through the heart of the building and onto a (as yet unrealised) public square beyond, the project resists the notion of theatre as a fixed entity, separate from everyday life, just as it resists ideas of front- and back of house. There are no wings or curtains. There is no real ‘stage’. The audience, lighting technicians and actors all inhabit the same space: all become a part of the performance. Underlying both projects is the creation of a living architecture, seen as a continuously evolving conversation between the past, the present and the future.

The transgression lies in both the disruption (rather than abandonment) of the controlling hand of the architect, and in the subversion of existing separations and hierarchies between spaces, activities and roles. In doing so the projects explore a conception of architecture as the infrastructure for the transformative performance of everyday life.

120

121

The Moskva Pool, 1958-1994

In 1931, the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow was demolished to make way for the grand Palace of the Soviets - an expression of Soviet wealth and power. The palace’s construction was halted in 1941 to supply materials for World War II and an open air public swimming pool was constructed in the foundations of the abandoned palace. It was the largest open air swimming pool in the world and was heated to extend its opening through the winter.

122

123

Palace of the Soviets

124

Alvaro Siza - Leca Swimming Pools

Embedded in the seaside landscape, these pools use simple materials matched to their surrounding context in a subtle and sympathetic way, creating the smallest of possible interventions in order to form the pool enclosure.

This is an architecture which does not fight against or try to change the natural environment it sits in, but responds and moves with it. It is not the aim to conquer nature, but to exist within it.

125

Performance

Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio - Traffic, 1981

Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, produced some of their earliest architectural projects in the form of theatrical pieces and outdoor performances. Traffic (1981), a 24-hourlong reorganization of Columbus Circle using 2,500 orange traffic cones shows how performance was key for these architects to test the ideas they would later solidify in glass and concrete.

Through the use of small props at the scale of the architecture, they were able to reveal existing routes of control and redirect them.

126

127

Ricardo Bofill, Taller de Arquitectura - Performance at Marqués de Riscal, 1968

In December 1968, the Taller members moved to a duplex on Calle del Marqués de Riscal, located in an upscale neighbourhood in the centre of Madrid. The Taller transformed this apartment, owned by member and economist Carlos Ruiz de la Prada, into their home and stage for a year. The latter designed the cooperative system through which City in the Space was to be funded, an alternative to state subsidies or state-sponsored bank credits. Although the performance was advertised both through classified ads in major newspapers and parades across the city, it mostly attracted a upper-middle class audience of intellectuals, university students, and civil servants. When entering the Marqués de Riscal duplex, visitors were welcomed into a conventional real estate office and filled

out a form. They then climbed a set of stairs to a small white room furnished solely with foldable ladders and vast mattresses. The space worked as a real-scale mock-up of the interior of the future dwellings.

The ultimate purpose of the performance was to estrange future City in the Space dwellers from all “conventional forms” of inhabitation of a house, preparing them to “obtain a definite and real proposal (...) of what would be his or her future home.”

128

Pilvi Takala - The Stroker, 2018

A two week-long intervention at Second Home, a trendy East London coworking space for young entrepreneurs and startups. During the intervention Takala posed as a wellness consultant named Nina Nieminen, the founder of cutting-edge company Personnel Touch who were allegedly employed by Second Home to provide touching services in the workplace. Nina strolled around Second Home being friendly to everyone, greeting and lightly touching people as she passed them by. It gets the office talking, workers gossip amongst themselves, visibly bonding over a common confusion – she was nicknamed ‘The Stroker’.

The responses of the ‘touchees’ varied widely, most were polite, but there were those whose body language registered a visible discomfort. Perhaps simply due to the cultural context of this invasion of personal space, or perhaps as a result of the inner conflict that arises when one does not feel able to truthfully or openly react. When unable to assert oneself, this kind of embodied negotiation may take the place of words.

The nuances of movement demonstrate how people negotiate the dilemma of being mediated bodies under social pressure, and how such responses are controlled by the tacit conventions governing what is deemed to be ‘acceptable behaviour’. In the clear-walled, open-thinking space of The Stroker, we witness a physical negotiation of boundaries where there seemingly are none.

129

Bill Viola - Deluge, 2002

Bill Viola uses 1:1 scale sets and props to enact a performance which uses film to record and relay it. The video shows people fleeing from something, with panic growing more and more frantic, until water begins to burst from behind the building facade, engulfing everyone and causing chaos.

Through behaviour, he stirs imaginations to what could be happening and alludes to the issue before actually showing it.

130

Roman Ondak - Good Feelings in Good Times, 2003

Good Feelings in Good Times is an artificially created queue. It is intended to be performed inside the museum, but can also be adapted to other spaces. The queue is always part of an exhibition and is created in or around an exhibition space. It is formed in front of a spot where it would make sense for a queue to form, or, for an enhancement of its effects, in front of slightly unexpected but not totally irrelevant spots. It can be re-enacted either indoors with a minimum of seven and a maximum of twelve people, or outdoors with a maximum of fifteen people.

Participants of Good Feelings in Good Times are either volunteers or actors hired by the museum and there is no restriction as to their age or gender. They are not required to wear special clothes, but are asked to dress to suit the situation, to hold personal props and look like ordinary people queuing as if waiting for something to happen. If questioned by onlookers, they are not allowed to divulge anything about the performance; they are instead encouraged to improvise as if they were in a real-life situation. The queue is re-enacted repeatedly during the day according to a schedule agreed between the artist and the museum, at set times and spots around the building. Typically, within a forty-minute period of performing, the queue will form, dissolve and form again a few times, with the participants behaving inconspicuously and as naturally as possible. The forty-minute performances may be repeated several times during the day, with twenty-minute breaks in between sessions for the participants to rest, unseen by the general public.

131

Catalogue of Elements

In moving the research into the privatised public space of Battersea Power Station, I used the same photographic documentation method as used at the pools, searching for similar elements in order to compare how they are used.

It is interesting to observe how the same elements can be subverted to create a heavily controlled environment, influencing people to be guarded and private.

132

boundary

The boundary is everywhere. It is used as a control method, directing people where they should go and keeping them out of places where they shouldn’t be. This can be in the form of harsh walls, signage, security cameras and bollards. Movement around the site is prescribed by these.

133

transition

The transition spaces are often very quiet and feel uninhabited - as if you are not meant to be there. They are often where residents access their apartments or where the staff of the surrounding offices and restaurants have a break, away from the public crowds.

134

bench

The bench is a solitary place. An in-between place. It is somewhere where you eat your lunch alone, scrolling through instagram or wait for a friend awkwardly. It is used as a brief waiting point placed alongside the circulation routes. People often use the benches not as they are intended - sitting backwards, leaning on the edge or resting a cup on them.

135

locker

There is no form of locker. Nothing personal is left here, it is void of individuality, designed to be neutral.

136

runway

The runways are carefully designed zones which move people round the site. These are constantly busy - the site is full of transit and movement. People pass through the site rather than rest or spend time there.

137

lifeguard

The “lifeguards” are the ever present security guards, monitoring every square inch of the site. They patrol or are stationed at strategic points, ready pounce on any unacceptable behaviour (of which one is taking pictures). I was asked not to take pictures. They are also a presence in the form of security cameras and barriers. There are also glimpses of traditional lifeguard materials such as lifesaver buoys which mark the connection to water.

138

edge

Edges are the step from legality to illegality - where you are and aren’t allowed. These are denoted by signs, changes in material and barriers. The water on site is not meant to be experienced, just looked at.

139

Programme of Elements

The proposed interventions use the elements as the base for organising the objects and actions for the performance. They use the corresponding swimming behaviours and place them in the subverted element at the Power Station.

The proposal imagines two swimming pools at the entrances to the Power Station - the areas of the heaviest control as a way of creating the most resistance.

140

Behavioural Interventions

This plan illustrates the proposed interventions on the site, situating them in relation to the subverted elements and imagined swimming pools at each of the entrances.

141

142

143

144

145

Objects

146

147

Signage

148

149

Actions

Actions will be the final and most elaborate of interventions. They will involve the behaviours identified from the poolside and will increase in magnitude and frequency - starting with one person, and ending in a large group performance which involves many performers all intervening simultaneously in order to explore the effect this has on the perception of the space and its prescribed behaviour.

150

151

Props

These physical props were developed as 1:1 metaphors of how these physical elements are subverted. The crowd control barrier sun lounger, security lifeguard chair and woggle no entry sign were created to subtly shift the set, merging the physical and behavioural language of the power station and the swimming pool to blur the context and its prescribed behaviours.

152

153

crowd-control sun lounger next page: security lifeguard chair and woggle no entry sign

154

155

156

157

158

changing perception

This series of behavioural interventions culminates in a large group performance which involves all the previously tested behaviour, signs, objects and props in order to test the critical mass of behaviour.

The intention for this intervention was to explore how a larger group with props, signs and objects would affect the acceptability of the actions; would more people and a more physically changed context allow for more acceptance? Could the behaviour change the perception of the space for the performers and viewers - prompting questions about what the space is used for and how it could be used?

A performance with a larger group enables the project to shift away from a focus on my own body within the spaceprobing further questions about types of bodies, gender, race, how those are received by others and how they feel within the space. The larger group also makes it possible for many who would not feel comfortable performing these actions as an individual.

The performance occurred on a cloudy bank holiday Monday the 8th of May at 12:00 - a peak time for the Power Station.

The following pages illustrate the plan for the performance and its outcomes.

Many thanks to:

cameras: Ellie Cullen, Matthew Hearn

lead: David Bourne

performers: Reuben Gower, Rosie Park, Sam Llewelyn-Smith, Rose Miller, Freya Hodgkinson, Edward Turner, Sean Mansfield, Joe Ellwood, Sam Fraquelli, Molly Hughes, Frank Brandon, Tom Grantham, Grace Frazer, James Bannister, Archie Duncan, Max Ge, Qirong Xu, Cassandra Adjei, Marnie Slotover, Ming Harper, Josh Parker, Megan Ellis, George Watson, Ben Ellis, Matt Donaldson, Charlotte Minter, Matt Congreve, Harry Tindale, Katie van Dawson, John Langran

159

These actions culminate in a large group performance which brings together 35 people along with signs, props and objects in order to create a critical mass for subverting the control elements on site.

This was planned for the 8th of May and occurred between 12:00 and 14:00.

160

Performance instagram open call

161

Performance Design

The design of the final performance traces the prescribed route through the site as previously explored through the walking tour, making it’s way through the layers of control.

Along the route, the performance engages with each of the identified control elements - the boundary, transition, edge, runway, lifeguard and bench and subverts their use to facilitate the poolside behaviours of changing, sunbathing and sitting.

The performance works within the existing environment while subtly subverting its behaviours, encompassing the props, objects and signage as a way of blurring the context and its prescribed behaviours.

The instructions were kept simple so as to effectively communicate them to the performers and involved a description of movement, location, numbers and timing, displayed in this simple leaflet.

The following pages illustrate the storyboard for the performance’s design.

162

ACT I boundary

164

still

location

time

movement

behaviour

ACT II transition

170

movement

behaviour

ACT III edge

176

ACT IV runway

182

ACT V lifeguard

188

ACT VI runway

194

ACT VII bench

200

Cyanotype Print

I chose to print the proposed intervention design storyboard using the same cyanotype process as used before to map the behaviour at the poolside. This is representative of bringing those actions to the Power Station and creates a more delicate, watery image.

The images below show the process of creating the dark box to house the print and to hold it during exposure, using diving board holders to keep the lid in place.

206

box open

box closed

207

cyanotype painted fabric beneath printed negative on acetate - pre-exposure

cyanotype during exposure

208

209

Performance preparation

The day of the performance required planning and coordination between people and times. The text below outlines the preparation for the day.

Director: Grant

Cameras: Matt, Ellie, Grant

Performers:

20+ swimming performers - to meet at 12:00 with towels, swimwear, flipflops

6 prop handlers - meet at 11:00

Sunbed: Jess + Sam

Lifeguard chair: Joe + Rosie

Signpost: Cassie + Max

Set out props in 2s - 1 person leaves and joins the swimmers, 1 person stays and holds one of the signs.

Protagonist: David

Timeline

09:30 - Grant collect props in van and bring to site

10:15 - arrive at BPS and park

10:30 - helpers arrive - prop handlers, cameras

10:45 - introduction and brief helpers

11:00 - unload van

11:30 - place props in safe space

12:00 - swimming performers arrive

12:15 - briefing + walkthrough

13:00 - 14:00 - performance

14:00 - interviews + film speaking shots of David

Props

Sunbed

Lifeguard chair

Signpost

Signs x 5

Towels

Trunks, goggles, cap, flip flops

Leaflets

210

211

performers gathered outside the Power Station

Performance stills

The following pages show some stills from the performance. Although it was not expected to go to plan, it was surprising how quickly the security guards tried to stop it happening.

The following pages and chapters reflect more on the performance and its success.

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

All of the audible conversations that were recorded during the performance between swimmers, security and the public.

TRANSCRIPT OF CONVERSATIONS BETWEEN BATTERSEA POWER STATION STAFF AND SWIMMERS

08.05.2023

*Inside security headquarters*

-hello there

-hello

This is part of my university project, I’m studying Architecture, but my project is based on behaviour and how that’s affected by the environment and as part of that I am doing a bit of an experiment/ performance where I’ve got a few friends and we’re taking the behaviour from the swimming pool, sunbathing things like that

-the swimming pool in the gym? Or an external site that you’ve already done and using that as an example?

-yeah just a generic imaginary pool

-so are you engaging with the people and you are interacting, what kind of reaction are you looking for?

-I’m not looking for a reaction

-what have you got, camera, microphone

-I’ve got a camera yeah

-and you’re asking them what questions?

-i’m not asking questions, it’s just my friends who have agreed to do this

-so it’s just you and your friends doing it, all personal?

-yeah

-all personal use it’s not for any company, BBC any publication?

-no it’s all academic

-so you’ve just got a camera you’re filming it’s just you guys, you’re not interacting with any of the public?

-no

-we don’t have an issue with that so they’re allowed yes?

As long as it’s for personal use its fine It’s all fine

222 Transcript

*during performance*

-you’re not allowed to do this

-why?

-that’s what we are told

-this is just my friends

-no not allowed, we just told you to do a get together but without removing the clothes

-without removing their clothes, is that the problem? If they put their clothes back on is it okay?

-yes not allowed to do this

Sorry sir not allowed to do this

-which bit specifically? Is it the clothes?

-i think if it was just arranged you could do it, it’s just probably just because its impromptu and because you’ve got your own stuff as well because this is private space, if you would have told them you were coming it would have been okay but just turning up like that, the security’s gonna stop you

-i did speak earlier and they said it was fine

-no i didn’t allow you to do this I think it’s better if you move

-would it be alright if they put their shirts on?

-no, not allowed to do all this. That’s the reason we have informed you all whether you’ve got permission but not all these things.

-okay we’ll move on, sorry